Перевод задания

Прочитай записи из словаря и ответь на вопросы.

Оксфордский словарь английского языка

библиотека сущ. (множ. библиотеки) комната или здание для книг

библиотекарь сущ. тот, кто работает в библиотеке

Оксфордский русско−английский словарь

handy [ˈhændi] adj (handier, handiest)

1) (clever with hands) умелый, рукастый (coll); he is ~ у него золотые руки

2) (easy to handle) удобный для пользования

3) (convenient) удобный, сподручный (coll); it may come in ~ это может быть

Вопросы

1) Слово «библиотека» взято из одноязычного словаря? А как насчет слов «библиотекарь» и «удобный»?

2) Где можно найти информацию о том, как произносить слова?

3) Откуда вы знаете, что одно из слов является существительным, а другое − прилагательным?

4) Какое из слов имеет одно, а какое более одного значения?

5) Какой из словарей дает словосочетания?

6) Какой из словарей дает производные слова?

7) Что означает знак ~?

ОТВЕТ

1) The word “library” comes from a monolingual dictionary. The word “librarian” comes from a monolingual dictionary, too. The “handy” comes from a bilingual dictionary.

2) We find information about how to pronounce the words in bilingual dictionaries. There are transcriptions there.

3) We know that one of the words is a noun and the other is an adjective because there are letters for it: n – for nouns and adj – for adjectives.

4) Some words have one and some words have more than one meaning. Dictionaries give different meanings under numbers. Here the word “library” has one meaning and the word “handy” has 3 meanings.

5) Some of the dictionaries give word combinations. For example, Oxford Russian−English Dictionary gives word combinations.

6) Oxford Russian−English Dictionary gives derivatives: handy – handier – handiest.

7) The sign “~” shows us the place of the word. For example, “it may come in ~” means “it may come in handy”.

Перевод ответа

1) Слово «библиотека» взято из одноязычного словаря. Слово «библиотекарь» также взято из одноязычного словаря. «Умелый» взято из двуязычного словаря.

2) Мы находим информацию о том, как произносить слова в двуязычных словарях. Там есть транскрипции.

3) Мы знаем, что одно из слов является существительным, а другое − прилагательным, потому что для него есть буквы: n − для существительных и adj − для прилагательных.

4) Некоторые слова имеют одно и несколько слов имеют более одного значения. Словари дают разные значения под числами. Здесь слово «библиотека» имеет одно значение, а слово «умелый» имеет 3 значения.

5) Некоторые из словарей дают словосочетания. Например, Оксфордский русско−английский словарь дает словосочетания.

6) Оксфордский русско−английский словарь дает производные слова: удобный − удобнее − самый удобный.

7) Знак «~» показывает нам место слова. Например, «это может прийти ~» означает «это может быть удобным».

Арзуманян Рузанна Валерьевна

«Слова, слова, слова…»

Предмет: английский язык

УМК:

«Английский язык», О.В. Афанасьева, И.В. Михеева

Класс:

8 класс

Тип урока: закрепление изученного материала

Цели урока:

×

Научиться дифференцировать

и пользоваться различными видами словарей на уроках английского языка;

×

Активизировать лексические

единицы в речи;

×

Развить навыки

аудирования;

×

Развить навыки

монологической речи;

Дидактический материал: учебник, рабочая тетрадь, ТСО, аудиоприложение к

учебнику, словари.

1.Организационный момент.

—

Good morning dear boys and girls.

—

Sit down please.

—

How are you?

—

Who is on duty today?

—

What date is it today, Vanya?

—

Who is absent today?

—

Thank you very much, Vanya, sit

down please.

Today we shall read and work with a text. We’ll practice

our reading skills and we’ll try to understand and analyze the information in

it.

2. Фонетическая зарядка.

But

in the beginning of our lesson let’s do some phonetic exercise.

Please

read these words in transcription.

(W/b p.42 ex.5)

3.Речевая зарядка.

I

want you to look at the blackboard. Read the names of the countries and match

them with the people (nations) who live there and their official language.

|

Countries |

People |

Official |

|

Australia |

American |

British |

|

China |

Australian |

Russian |

|

England |

the |

Japanese |

|

Great |

the |

Italian |

|

Italy |

Norwegians |

Dutch |

|

Japan |

the |

Norwegian |

|

Norway |

Italians |

Vietnamese |

|

France |

the |

French |

|

The |

the |

American English |

|

The |

the |

|

|

Vietnam |

Russians |

|

|

Russia |

the |

(w/b p.42 ex.4)

4.Проверка домашнего задания.

Now

let’s check your homework. Vanya please make us remember what was your home

task? (w/b p.44 ex.8)

It’s

a good work.

5. Работа с текстом.

5.1 Дотекстовый этап.

Now please let’s go on. Open your t/b-s at p. 53 ex.8.

The text “WORDS… WORDS…WORDS…”.

1) Look at the title of the text. What are we going to

read about? …. OK! We’ll see.

2) Dear children! Look

at the blackboard. There are some difficult words from the text.

Who wants to try reading them? OK! Igor, please begin.

·

Person [pə:’sən ]

·

Look up

pronounce[prə’naυns]

·

categories [‘kǽtigəriz]

·

lingual=language[‘liηgwəl]

·

monolingual

[monəυliηgwəl]

·

bilingual [bai’liηgwəl]

·

multilingual [mΛlti’liηgwəl]

·

Webster’s Third New

International Dictionary

·

Oxford Basic English Dictionary

·

Oxford Russian Dictionary

3) Children! Who can try to tell the main idea of the

text?

That’s good!

4) Tell me please, where do you usually find the

meaning of a new word?

5) What dictionaries do you know? Ok!

5.2 Текстовый этап.

1) And now before we start reading the text, I want

you to listen to it. Please, look and follow while listening.

2) Well that’s it. Now let’s begin reading.

“WORDS… WORDS…WORDS…”

We

say them, we hear them, and we read them and write them. And telephones,

mobiles, radios, televisions, computers are all there to carry words to all

part of the world – and even to the moon and back. How many must a language

have? For example, there are more than 450,000 words in Webster’s Third

New International Dictionary. No person [ˈpɜːsn̩] knows all of them, but

most people are able to understand about 35,000 and use about 10,000 –

12,000. Usually you use only one-tenth (1/10) as many words as you

understand.

If

you hear or read a new word and want to know what it means, you look the word

up in the dictionary. Modern dictionaries are very different. Most of them

give words alphabetically. With the words they give information how to

pronounce [ prəˈnaʊns] it, what meaning or meanings it has, if there are any

difficulties in its grammar and use. There are three big categories

[ˈkætɪɡərɪz] of dictionaries: monolingual [ˌmɒnəˈlɪŋɡwəl], bilingual [baɪˈlɪŋɡwəl]

and

multilingual [ˌmʌltiˈlɪŋɡwəl]. They give information about words in one

(mono-), two (bi-) or more than two (multi-) languages.

3) OK! Look at the following figures 450,000; 35,000; 10,000 – 12,000. What do

they mean?

Good!

Shall we move on?

5.3 Послетекстовый этап.

1) And now, I want you to describe the kinds of dictionaries using the text. So…

— the monolingual dictionary

— the

bilingual dictionary

— the

multilingual dictionary

2) Let’s make up a new title

for the text. Please your variants.

3) And now, we’ll make up a

plan for our text. It will help you to prepare your retelling.

a)…….

b)…….

c)…….

4) Now please let’s go

on and do the ex.9 p.54. Please, read the task.

Look at the two dictionary

entries and answer the questions.

a) library [ˈlaɪbrəri]

n (pl libraries) a room or building for books.

librarian [laɪˈbreərɪən] n someone who works in

library.(Oxford Basic English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1995.)

b) handy [ˈhændi]adj

(handier, handiest) 1 (clever with hands) умелый, мастеровой, рукастый (coll); he is~ у него золотые руки. 2 (easy to handle) удобный

для использования. 3 (convenient) удобный, сподручный (coll); it may come in~ это может пригодиться. (Oxford Russian Dictionary. Oxford University

Press,2000.)

Questions

1)

Which of the two words comes from

a monolingual (bilingual) dictionary?

2)

Where can you find information

about how to pronounce the words?

3)

How do you know that one of the

words is a noun and the other is an adjective?

4)

Which of the words has one and

which more than one meaning?

5)

Which of the dictionaries gives

word combinations?

6)

Which of the dictionaries gives

derivatives?

7)

What does ~ stand for?

6. Подведение итогов.

I think that’ll do. Thanks for

your good work. Now my dear friends our lesson is over. Open your daybooks and

write down the homework. Your home task is to retell the text using your plan.

And now your marks.

See you soon! Good bye!

There are about 250

different kinds of dictionaries and their typology is not easy. The

leading competing companies compiling and publishing English

dictionaries produce various,

though very often similar series known as Oxford,

Cambridge, Longman, Collins, Chambers’s,

Penguin dictionaries (in

Great Britain) and Webster’s

(G. and C.

Merriam Co.),

Funk and Wagnalls Co., Random house dictionaries (in

the USA). Here arc the most important

principles along which they may be classified.

All reference books that provide a large amount of information of a

particular kind. But

according to

the type of items included and

the kind of

information about them all

dictionaries

may be divided into two categories: encyclopedic

and

linguistic

dictionaries,

or

into encyclopedias

and

dictionaries. ,

147

An

encyclopedic

dictionary is

a thing-book.

It

deals with every kind of knowledge about the

world (general encyclopedia) or with one particular branch of it

(special encyclopedia).

In

contrast to a linguistic

dictionary, which

is a word-book,

some

common words, like mother,

father, house, I, the, white, oh, do

not enter an encyclopedia, while many geographical

names and names of prominent people make up an important part of it.

Some words, like taxonomic

names of plants, animals, and diseases enter both kinds of

dictionaries,

but information about them has a different character. In linguistic

dictionaries

the most extensive information is linguistic

information

about a word. In encyclopedic

dictionaries the most extensive is extralinguistic

information

about a concept.

The

most well known encyclopedias in English are The

Encyclopedia Britannica (in

24 volumes)

and The

Encyclopedia Americana (in

30 volumes). Very popular in Great Britain

are also Chamber’s

Encyclopedia (in

15 volumes) and Everyman’s

Encyclopedia (in

12 volumes). Among single-volume encyclopedias is the Hutchinson

20th Century Encyclopedia.

There arc also smaller

reference books that are dedicated to special branches of knowledge:

literature, business, medicine, chemistry, and linguistics. For

example, Who’s

Who

dictionaries,

The

Oxford Companion to English Literature (Theatre, etc.),

Cambridge

Paperback Guide to Literature in English, The Cambridge Guide to

Women’s

Writing in English, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English

Language by

David Crystal, or The

Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language by

David Crystal.

In

modern reference books, however, there is no strict borderline

between these two types of

dictionaries. Many linguistic dictionaries, especially in America and

the Longman

dictionaries,

include extralinguistic information, and many encyclopedic

dictionaries include

some linguistic information.

Classification of linguistic dictionaries

1.

One of the basic criteria for classifying linguistic dictionaries is

the

number of lexical items

they

include. A linguistic dictionary may be unabridged,

the

most complete

of

its type, and abridged.

One

may think that the bigger the dictionary is the better vocabulary is

presented there. This

may be true but it is simplification of the problem of lexicon.

The

most complete, unabridged

general

dictionaries, like Webster’s

Third New

International

Dictionary of the English Language and

the Oxford

English Dictionary

include about half of a million (500,000) entry words. But even they

do not include all the

148

lexical

units in the language. Scientific, technical terms and many other

specialized lexical units are left out and delegated to special

dictionaries.

The

number of lexical items in other dictionaries is usually less

numerous. A dictionary for

kindergartens like The

Oxford Picture Dictionary for Kids may

include about 700 words,

which are actually labels for pictures. A second-grader may need a

dictionary with about

3,500 entries. Pocket English dictionaries may include over 12,000

words, like the Longman

New Pocket English Dictionary.

2. Depending on the nature

of the included lexical items linguistic

dictionaries may be divided

into general

and

restricted.

General

dictionaries include words from different

spheres of life. Restricted linguistic dictionaries are limited to

some special branch of knowledge

like

medicine, business, chemistry, or to some special kinds of lexical

units, such

as dialectal words, foreign words, neologisms, obsolete and archaic

words,

or phraseological verbs and idioms, for example, Dictionary

of American Slang by

Richard A. Spears, The

Basic Words by

C.K.Ogden, American

Dialect Dictionary by

II.

Wentworth,

the Oxford

Dictionary of Computing for Learners of English, or

the Oxford

Dictionary of Business English for Learners of English.

As mentioned above, there

arc numerous dictionaries of the same type compiled and published

by different people and different companies. For example, some

well-known dictionaries

by different companies arc restricted to English idioms as Oxford

Dictionary of

English Idioms (by

A.P. Cowie, R. Mackin, I.R. McCraig) with 7,000 references, Cambridge

International Dictionary of Idioms with

7,000 references, Longman

Idioms Dictionary

(by

Addison Wesley/Longman) with 5,000 references, Collins

Cobuild Dictionary

of Idioms with

4000 references, Chambers

Dictionary of Idioms, and

Penguin

Dictionary of English Idioms. They

differ not only in the number and character of

idioms included in the dictionary but also in the manner of their

presentation, interpretation,

and some of them include exercises aiding assimilation and correct

usage.

3.

Depending on the linguistic

information they

provide all dictionaries may be s p с с i a 1

i z e d or non-specialized.

Specialized

dictionaries may specialize in phonetic information,

like English

Pronouncing Dictionary by

Daniel Jones, Longman

Pronunciation

Dictionary by

J.C. Wells, or in etymological data, for example, The

Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology by

C.T. Onions, in usage as docs Longman

Guide

to English Usage by

J. Whitcut and S. Greenbaurn, in frequency as the General

Service

List of English Words by

M.A. West, in word collocations like The

BBI Combinatory

Dictionary of English by

Morton Benson, Evelyn Benson and Robert Ilson, or

The

LTP Dictionary of Selected Collocations, where,

for example, the section ‘Noun’ gives

about 50,000 collocations for 2,000 most essential nouns.

Dictionaries also may specialize in semantic relations of words as A

WordNet

Electronic Database which

includes

word nodes and indicates their synonymic, antonymic, hyponymic,

meronymic, taxonymic

and other relations.

149

4.

Depending on the number

of languages used

in the entries, a linguistic dictionary may be

monolingual,

bilingual

and

polylingual.

Monolingual

dictionaries

are usually explanatory,

while

bilingual and polylingual are normally translation

dictionaries.

Yet, this correlation is not strict. Some of the monolingual

specialixed

dictionaries, like Roget’s

Thesaurus are

not explanatory at all, and some bilingual

dictionaries, like Англо-русский

фразеологический словарь by A.V. Kunin, can

hardly be called just translation dictionaries because they provide

many different explications

for lexical units.

5.

Depending on the time

period embraced as

well as the character

of treatment of lexical items, dictionaries

are divided into synchro

nic-

including

the words of a certain language

period, mainly modern English, like The

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Longman Dictionary of Contemporary

English, Student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon by

II.Sweet, and diachronic,

or

historical dictionaries that register chronological development

of a word over time (the Oxford

English Dictionary and

its shorter two-volume

version the Shorter

Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles).

6.

Dictionaries arc also classified according to the prospective

user (a

teacher, a lawyer, an

adult, a child, or a person with poor vision). For example, the

Longman

Business English

Dictionary is

for students and people working in business. It includes 13,000

entries

covering terms in accounting, marketing, finance and other fields.

The Longman

Dictionary

of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics is

written for students and teachers

of linguistics and language teaching.

There

is a special type of dictionaries for learners of English as a

foreign language that is usually

referred to as learners’

type of English dictionaries.

These

dictionaries are typically linguistic dictionaries that cater to the

needs of foreign language

learners’ of different age, interest and level of language

proficiency.

Linguistic

dictionaries of learners’ type vary

in number of words, information about them, the

manner in which this information is presented. But all of them arc

noteworthy for the thorougness of their entries, explicit

pronunciation, carefully chosen examples of usage, and

abundance of pictorial illustrations.

Here

arc some monolingual

dictionaries

of this type, listed according to the learner’s

proficiency level:

Elementary to intermediate:

The

Oxford

Basic English Dictionary (11,000

words and phrases) and the Oxford

Elementary

Learner’s Dictionary (15,000

references) have easy explanations of meaning and

use, include guides to grammar forms and provide vocabulary-building

notes.

150

The

topical Oxford

English Picture Dictionary for

beginners to intermediate by E.C.Parnwcll

explains over 2,000 words (mainly nouns).

The

Longman

Elementary Dictionary gives

the meaning of 2,000 basic English words. It is

aimed at young learners and is richly illustrated.

Intermediate:

The

Oxford

Wordpower Dictionary has

30,000 references. It is designed to help students make the

breakthrough from a basic survival vocabulary to greater fluency. It

pays special attention

to vocabulary-learning skills and includes a study section that

presents techniques

for learning and recording new words.

The

Longman

Active Study Dictionary has

over 45,000 references with clear definitions based

on the 2,000-word Longman Defining Vocabulary. It also has

corpus-based examples

of usage, vocabulary practice exercises, and usage notes to help

students to avoid

common errors.

Intermediate to advanced:

The

Oxford

Learner’s Wordfmder Dictionary is

designed to enrich and expand learners’ vocabularies.

It includes over 600 entries that group vocabulary around keyword

concepts.

It also has extensive coverage of synonyms, opposites, derived words

and common

phrases.

The

Longman

Essential Activator, like

many other Longman dictionaries, has extra information to help

students avoid making common mistakes registered in Longman Learner’s

Corpus.

Upper-intermediate to advanced (proficient):

The

Oxford

Advanced Learner’s Dictionary by

A.S. Hornby

is

the world’s leading dictionary

for learners of English. It includes 63,000 references, 90,000

examples, 11,600 idioms

and phrasal verbs. The vocabulary used for definitions includes 3,500

carefully chosen

words. The sixth edition is available both in a book and CD-ROM

format.

The

Longman

Dictionary of Contemporary English is

of the same type. In addition to the types of information presented

the dictionary by A.S. Ilornby it also lists 3,000 most frequently

written and spoken words. Definitions in this dictionaty arc easily

understood because

only 2,000 words make up its defining vocabulary. More than 25,000

fixed phrases

and collocations arc included. The dictionary is based on language

databases of six

corpora, including the British National Corpus (Written and Spoken)

and the Longman American

Corpus (Written and Spoken), so it has the most up-to-date coverage

of English.

Longman

Lexicon of Contemporary English by

Tom McArthur includes

a detailed and

well-grounded taxonomy of semantic fields, clearly worked out

definitions and an

alphabetical index. It is both an explanatory dictionary and a

thesaurus.

151The

Longman Language Activator is

especially good for self-study and preparing for an examination like

the Cambridge Certificate in Advanced English. It takes students from

a key word through words and phrases they may need to express

themselves accurately and appropriately

in every situation.

Bilingual

and

Polylingual

Learners’Dictionaries

Bilingual

dictionaries are in special demand among beginning foreign language

learners.

The

most important and widely used English-Russian dictionaries in the

CIS countries are Англо-русский

словарь by

V.K. Muller, which includes about 70,000 references, Большой

англо-русский словарь in

two volumes (edited under the direction of I.R. Galperin

and K.M. Mednikova) with 160,000 references.

The

recent English-Russian bilingual dictionary under the editorship of

Y.D. Apresyan Новый

большой англо-русский словарь (1997,

second edition) includes more than 250, 000 references. It pays

special attention to finding ways of rendering semantic equivalence

between two correlative naming units in English and Russian.

Making

the list of complete and reliable Russian-English dictionaries one

should mention, first

of all, the

Русско-английский

словарь with

50,000 words compiled under the general

direction of A.I. Smimitsky, edited by O.S. Akhmanova.

A new generation of

bilingual dictionaries tries to combine accurate and up-to-date

translations

with the features of a monolingual learners’ dictionary. The

necessity of such a

combination was pointed out by the Soviet linguist L.V. Shcherba as

long ago as the 40’s

/Щерба 1958:88/. The major emphasis in these dictionaries is

placed now not just on correct

understanding of English words but also on learning how to use them.

Carefully chosen words are backed up by corpus-based examples,

pronunciation and illustrations. Notes

in the user’s own language help explain the grammar, usage, and

vocabulary. There are

also cultural notes, study pages and appendices on areas of

particular interest to different

groups of students.

A

polylingual learners’ dictionary Pocket

English-Belarusian-Russian Dictionary (Юшэнны

англа-беларуска-pycKi слоушк) is

compiled and edited by T.N. Susha and Л.К.

Shchuka at Minsk State Linguistic University and published by

Vysheyshaya Shkola in

1995. It includes 10,000 English naming units (words, collocations,

phrasal verbs and idioms)

and their equivalents in Belarusian and Russian as well as a list of

geographical names,

most common abbreviations and some extralinguistic information.

There

are a number of electronic bilingual dictionaries. The Abbyy

Lingvo 6.0 is

useful for

any foreign language learner and especially professionals as it is

rather a system of 14 dictionaries.

One of its LingvoUniversal (English-Russian Dictionary) includes

100,000 entries, the other LingvoUniversal (Russian-English

Dictionary) includes 70,000 entries.

152

The rest are specialized

dictionaries in business English, management, polytechnical terms,

and oil and gas refinement terminology. It also provides a sound

track for 5,000 most

frequently used English words.

Besides

purely linguistic dictionaries there arc many encyclopedias for

English learners that

combine encyclopedic and linguistic information, like the Oxford

Advanced Learner’s

Encyclopedic Dictionary with

93,000 references, among them 4,650 entries on people,

institutions, literature, and art, 94 feature articles on British and

American life, special

notes on literary and cultural connotations, or the Longman

Dictionary of English Language

and Culture with

80,000 words and phrases and over 15,000 cultural references.

Further reading:

Ступин. Л.П.

Словари

современного английского языка. —

Ленинград: Изд-во

Ленин!

радского университета, 1973. Суша

Т.Н. Лингвистические

основы лексикографии/На англ, языке —

Минск: МГЛУ,

1999.

Щерба

Л.В. Опыт

общей теории лексикографии//Избранные

работы акад. Л.В.

Щербы,

т.1. -Ленинград: Изд-во Ленинградского

ун-та, 1958. Burchfield,

Robert. The

English Language. — Oxford, New York: OUP, 1985. Hartmann,

R.R.K. (ed.).

Lexicography: principles and practice. — London: Academic

press, 1983.

Kraske,

Robert. The

Story of the Dictionary. — N.Y.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

WordNet:

An Electronic Lexical Database (Ed.

by Christian Fellbaum). — Cambridge,

MA: The MIT Press, 1998.

153

Chapter

10. THE MENTAL LEXICON AND THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY ACQUISITION

«When

we survey the variety ojconceptual structures that the

English language expresses we see that they are far too heterogeneous

to submit to any simple formula. No single

blueprint can adequately characterize the internal structure

of every semantic field; the architecture of the lexicon

is at least as diverse as the architecture of houses, skyscrapers,

bridges, gardens. If we wish to discover generalizations

about semantic structures, the best place to look would be in the

ways lexical concepts can be put together

rather than in the shapes of the finished products

«.

George

Miller and Philip N. Johnson-Laird, Language

and Perception, 1976:271.

The mental lexicon. The individual vocabulary of an adult. The

acquisition of the lexicon. The mental lexicon of a bilingual.

The mental lexicon]

The

word ‘lexicon’ long time has been associated with lexicography. It

was viewed as a large

dictionary that contains orthographical representation of an enormous

number of words related, first of all, alphabetically. The list of

words included much information about

their meaning, grammatical characteristics and probably pronunciation

that helps, however,

to establish other kinds of word-relations.

Lexicologists

paid special attention to semantic relations of words in a vocabulary

system arid

traditionally described them as paradigmatic and syntagmatic,

antonymic, and synonymic

(sec Chapter 7).

Since

knowledge of a language and its vocabulary is stored in our heads,

research on the ways

this storage is done and exercised was relegated to psychologists.

But modern linguistics is

marked by a fusion of theoretical general linguistics and psychology,

and the term ‘lexicon’ becomes more and more associated with the

mental lexicon.

One of the steps necessary for translating conceptual knowledge into

linguistic knowledge

is retrieving appropriate lexical units from our mental lexicon.

The

mental lexicon is

a lexical system representation in our mind.

Linguistics

has yet to provide a single undisputed working model of the mental

lexicon due

to its complexity. Now linguistics can only offer different

suggestions concerning its

154

most

abstract aspects, for example, the place of the mental lexicon in the

general model of language

capacity, structure oflexicon, character and number of items included

and types of

information about them.

ЛИ

scholars agree that our minds should contain the same types of

information about the word:

phonological, orthographical, morphological, semantic and syntactic,

and all of them are somehow linked. Otherwise the word would not be

understood, retrieved or properly

used.

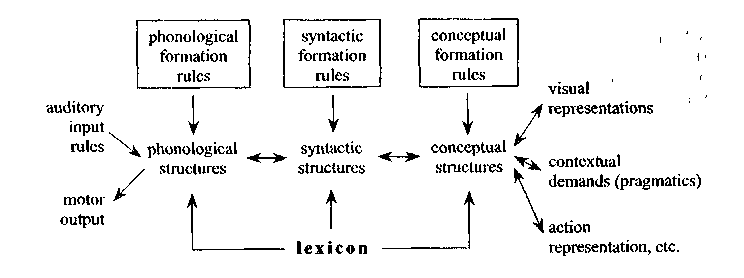

Within the general model of

language capacity the mental lexicon should be directly related first

of all to lexicalizcd conceptual structures, because words without

meaning make

no sense. It should also be connected with syntactic and phonological

structures.

In order to perform its

generative character without which there is no acquisition and growth

of the vocabulary, the mental lexicon should also be connected with

rules governing

correct formation of conceptual, syntactic and phonological

structures.

Schematically it may be

represented in the following pattern worked out by

Jackendoff/Jackendoff

1997:39/:

As

it is presented in the scheme, language has three basic components,

with the lexicon being

attached to all of them.

Due to the lexicon all these

components of the mental grammar match. Interruptions in mapping

between the components and/or lexicon create problems in language

comprehension

or use. 1’he lexicon also has information about specific restrictions

the word

may have. The mental lexicon thus happens to be a deposit of all

knowledge

about the

meaning, grammar and phonology of the word. Thus, boundaries among

lexicon, grammar and phonetics are quite artificial, created just for

the sake of analytical convenience.

155

The

crucial questions are what is presented in the mental lexicon and how

it is structured to

provide reliable storage and retrieving from the memory.

It

should also be mentioned that traditional linguists have created a

successful science by ignoring

the numerous interactions between linguistic knowledge and world

knowledge as well

as the psychological and neurological structures providing it. They

have also developed

a methodology that works well for phonology, syntax, morphology and

certain areas

of semantics. But understanding and describing new, psychological

areas of lexical semantics

requires special methods of investigation that are still

in the process of developing.

Modern psycholinguistics makes a

wide

use of psychological methods, like free

association tests, and time measuring tests on word recognition as

well as traditional linguistic

analyses.

It has been established that

words in the mental lexicon are usually kept without inflections.

Inflectional suffixes are added to stems later, in speech. But

derivational affixes

are in the mental lexicon, at least as parts of derived words that

are stored there.

Nevertheless,

scholars still debate the

number and character of units stored in the mental lexicon.

One

theory argues that only simple

words and

their multiple properties are stored in our mental

lexicon. Among these properties arc: how a word is pronounced, what

part of speech it belongs to, what other words it is related to, and

how it is spelled. These properties

make up separate entries in our mental lexicon, and each of them

makes up a separate

interface and has a different access. That is with access to a word’s

acoustic property

we are able to find a rhyming word for it or to list some other words

with similar sound

structures just by using the lexicon’s phonetic interface. With

access to the part-of-speech

meaning of a word we may retrieve thousands of words with the same

lexical-grammatical

meaning from our memory. Tapping into semantic interface of a word,

we may

activate and retrieve lots of words semantically related to it. So,

in our mind there are multiple

vocabularies each of them with different units as their nearest

neighbours.

According

to this theory, derived lexical units and rules of word-formation are

outside the mental

lexicon. The mental lexicon is the place for just simple, non-derived

words. Derivatives may be somewhere else, for example, they may be

part of grammar or of some

other component of the language faculty.

But

it is also known, and it was mentioned in the previous chapters, that

all derived

and !

compound

words as

well as phraseological

units have

a special idiomatic component that <

can not be deduced from the formal structure of a lexical unit. This

fact provides the !

grounds

for believing that they should also be memorized and listed in the

mental lexicon.

Moreover, the rules of

word-formation listed in morphology are too general to be adequately

applied to a concrete word to form an accepted derivative. It makes

more sense

to

enlist the rules of word-formations with

all their exceptions and idiosyncrasies in

156

the

mental lexicon. That will add to the model of the mental lexicon its

active generative character

that we observe when we produce and interpret new words.

Not all derived and compound

words and word combinations should be listed in the mental

lexicon but only those that cannot be decomposed without changing the

meaning of

a lexical unit.

Thus, in the mental lexicon

alongside simple words there may be some derived and compound

ones and even sentences and some texts. There should also be some

rules

on

how

these complex units may be decomposed into simple ones or how a great

number of well-formed

derived words and even phrases with all their idiosyncratic

properties can be easily

produced or reproduced in speech.

Thousands of words,

morphemes and phraseological units as well as rules of their

formation

should be stored in our mind in some order, otherwise a momentary

successful retrieval and recognition would be impossible. The

question, however, is how?

There

arc many reasons to believe that there are radical differences in

quantity, character and

organization between words stored in alphabetically organized

dictionaries and the words

stored in our minds.

No person knows and uses all

the words that a large dictionary may contain (see ‘The individual

vocabulary of an adult’ below). Vice versa, each person has much more

information about each word that any dictionary may contain. The

information about meaning of the word presented in a dictionary is

scarce, dry and meager in comparison with the conceptual information.

For example, we know which word stands for prototypical item and

which for peripheral (cf: sparrow,

penguin, ostrich are

all birds,

but

only sparrow

is

the most typical of them). We may recognize different pronunciations

of

a word produced by different speakers while a dictionary may give

only one variant. Information

about combinability of a word is undcrrepresented in any dictionary:

a native speaker

knows much more information about lexical and grammatical

restrictions on word

usage which is quite scarce in a dictionary.

Linguists and psychologists collected much data about storing lexical

items and rules in

our

mind. Retrieval

of words from

memoiy and checking the activation

zones in

our mind

by modern equipment give a lot of information about the structure of

the mental lexicon.

Thus, it has been proven that different groups of words are stored

differently and are

placed in different cortex /ones. That is why some fields for some

reason may be

damaged without involving the others. After strokes people may

remember the names of

such concepts as ‘sphinx’ and ‘abacus’ but not remember the names of

fruit and

vegetables /Aitchison 1994:84/. Verbs and nouns, functional and

notional words are

stored separately in the mental lexicon, too.

Slips

of the tongue are

also an important source of this information. For example, since we

do

not have slips of the tongue for the words that follow each other in

a dictionary, like

157

decrease

and

decree,

there

are grounds to believe that in speech production the phonetic

interface is not as close to conceptual structures as, for example,

the semantic one, where the

relatedncss of such words as forks

and

knives,

and

shirts

and

skirts

cause

quite frequent

slips of the tongue.

So,

the mental lexicon may be viewed as

a structure with a number of distinct modules for

different types of information. There are separate modules for

syntactic, phonological, morphological

and semantic presentations; content words are supposed to be kept

separately

from functional words, verbs to be kept separately from nouns and

derivational affixes

separately from inflectional ones.

Yet,

the mental lexicon is not only a complex structure of information but

it is also a

complex

system where

all these types of information arc somehow connected.

The

degree

of connection between

different interfaces and between lexical units in the semantic

semantic interface of the mental lexicon is different: some links are

particularly strong,

like conneetionss between co-ordinates and collocational links; some

links are somewhat

weaker, like the connections between some of hyponyms and hyperonyms.

Nevertheless,

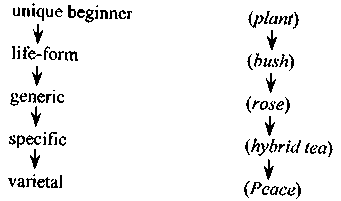

hierarchical relations are the most important types of word relations

for the assembling

the words into a structured whole. One theory assumes that a hyponym

inherits

the properties of its superordinates. To understand and remember a

hyponym we do

not need to mcmori/c all the features characteristic of a hypcronym,

we need to remember

only the

distinguishing features of

hyponyms. So, the inheritance system saves memory

space.

Numerous

studies of hierarchical taxonomies of words proved that on the

folk-level they

typically

have no more than

five levels

(see /Cruise 1991:145/) and frequently have fewer. These

levels are commonly labelled as follows:

The

most significant level of a taxonomy is called generic.

This

is the level of names of common

things and creatures: rose,

cat, oak, apple, car, cup. It

is the most numerous level,

and it is the level whose units are learned first. It is the level,

the units of which are predominantly simple, native and the most

frequently used names make up prototypical members

of the category.

158

There

are also connections between words of different lexical-semantic

fields (interfield

relations).

Some

of them, usually referred to as entailment,

or presupposition are

strong. Here are some examples of this type of semantic relations

between groups of different

lexical-semantic fields.‘Killing’

entails

‘dying’,

if

there is a ‘killing event’, then there

is also a ‘dying event’. Or, if

John is selling

his

piano it

means that John

owns

a

piano.

‘Sight

presupposes

eye,

education presupposes

learning,

journalist presupposes

press.

Some

inter-field relations may be weaker than that but they also may be

easily computed by reasoning. Conventional polysemes as well as

morphologically derived words where the

source and target names belong to different semantic fields make

these connections stronger.

Thus,

the lexical units, and first of all, words, form in our mind a kind

of a word-web,

where words are linked on various semantic, phonetic and syntactic

grounds. And now we

shall consider how people acquire this word-web. ‘

[2. The individual vocabulary of an adulll

It

was mentioned above that the English lexicon consists of a million

or, according to some

estimates, even up to three million words. Nobody, however, knows all

the words in a

language, though it is interesting to know how many words an

individual knows.

An

Englishman named D’Orsay produced a study based on the everyday

speech of a group

of fruit pickers, in which he came to a rather startling conclusion

that the vocabulary

of the illiterate and semiliterate does not exceed 500 words. Some

other studies

of subway conversations estimate the vocabulary of the average person

to be of about

1,000/Pei, 1967:116/.

Still

another estimation places the average adult vocabulary at between

35,000 and 70,000 words.

There is also an opinion that an

adult individual knows more

than one-fifth of the total number of words in a language, i.e. about

200.000

words. Hundreds

of thousands of words,

though they are listed in the large dictionaries, belong to special

scientific, professional,

or trade vocabularies and are not used or even recognized by the

average speaker.

It may also be forgotten that speakers naturally tend to acquire and

use those words which naturally fit into the picture of their

everyday lives. An illiterate peasant knows

the names of plants, shrubs, trees, insects, animals, and farm tools

of which a highly

educated and cultured city dweller may be almost totally ignorant.

Education and culture

have a great deal to do with vocabulary range, but not inevitably so.

Illiterate speakers

sometimes reveal an amazing range of spoken vocabulary.

159

The

discrepancy in the estimates of the mental lexicon may be partially

due to confusion between

use vocabulary and recognition vocabulary. For every word that we

constantly use

in our every day speech, there are perhaps ten words that we arc able

to recognize when

we hear them or see them in print. Some of these we are also able to

use when the occasion

calls for them. This would mean that even the child or adult having a

normal use vocabulary

of 1,000 words would «know» 11,000.

Greater

precision can, of course, be achieved in the matter of vocabulary

range for literary purposes.

But even here we run into striking discrepancies. One authority, for

example, estimates

that Shakespeare used 16,000 different words in his works, another

20,000, while

a third places the figure at 25,000. Racine is said to have used only

6,000 different words,

Victor Hugo 20,000. For newspaper usage we arc informed that a single

issue of the

French Le

Temps contained

3,800 different words /Pei 1967:118/.

The

question of vocabulary possession is complicated by the complexity of

the word itself,

by the difficulty of its definition. Moreover, one word may include

several naming units

when

it is polysemous. So, to estimate the mental lexicon’s volume one

should count naming

units, not words, as it is done traditionally. But such calculations

may become even

more problematic due to difficulties of sense differentiation.

f he acquisition of the lexicon)

The average time it takes a

child to learn the first 10 to 50 words is quite long: 4.8 months.

It means that the rate of the first words acquisition is about 10 new

words a month.

By

18 months children can use about 50 words and understand about five

times as many. Within

these 50 words there are nominals and action words, modifiers and

function words,

the words for personal and social relations. There are individual

differences in early

lexical development. Some children learn more object labels to talk

about familiar environment,

some children learn more pronouns and function words to to talk about

themselves

and others /Nelson 1981/.

After

that age a ‘vocabulary

explosion’ takes

place. By the age of two children’s spoken

vocabulary exceeds 200 words. By the age of seven children know about

1300 words and

schoolchildren learn thousands of new words per year. It is estimated

that the average

Oxford undergraduate has a vocabulary of about 75,000 words.

Many

reputable linguists have challenged these estimates. A very careful

study made by a ^roup

of psychologists presents the following figures: an average four-year

old child cnows over 5,000 words; at six, he reaches a vocabulary of

14,000 words; at eight, of 26,000

words; at ten, of 34,000. They claim that a college-educated adult’s

mental lexicon nay be up to 250,000 of words /Katamba 1994:228/.

160

Again,

estimations vary widely due to methodological difficulties and

different understandings

of the term ‘word’.

Learning

vocabulary means not only memorizing labels for certain concepts but

also acquiring

the rules according to which so many of these labels are created.

Children acquire

the derivational system of the language by the age of four, and from

that time their

vocabulary grows intensively thanks to the correct application of

derivational rules and

derivational morphemes. The majority of words they learn after that

age are derived words.

Measuring

the rate of children’s word-acquisition is the easiest thing in the

theory of the lexicon acquisition. A far more difficult thing is to

explain HOW it happens, and that is left

to theoreticians.

In

theoretical linguistics the problem of vocabulary acquisition is

quite new. Little has been

done to reveal the nature of word learning so far, and there are more

questions than answers

in this field. But all the linguists whose concern is the lexicon

point out that there is

a great need for such a theory. The ideas of complexity and

idiosyncratic nature of the lexicon,

of the innate linguistic ability and categorization principles are

definitely not enough

to explain children’s process of vocabulary acquisition.

Scholars

discuss the problem of ability to segment varying sound wave into

words, and there

is a belief that children can do it because of rhythmic alternation.

Concept

and word acquisition requires the ability to catcgori/e, and scholars

question whether

children’s mental representations are the same as adults’ ones.

Techniques

for deciding what a word may mean are under consideration. There are

some theories

on that, and one of them states that for a child a new word stands

for the whole thing,

not its parts.

Scholars argue about the

links between syntax and lexicon in the process of word-acquisition.

Some scholars believe that children make use of syntactic structures

in which the

words occur. These structures narrow the range of possible

interpretations.

The

question of the degree of brain activization is also discussed. The

recent interactive

activation

theory

suggests that the mind is an enormously powerful network in which any

word

which resembles the one heard is automatically activated, and that

each of these triggers its own neighbours, so that activation

gradually spreads like ripples on a pond. The opposite view on word

acquisition stresses the effectiveness of the mind and «the

least

efforts principle» that would never allow for such a procedure.

The

problem of vocabulary acquisition has been approached from a variety

of perspectives:

linguistic, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistic, neurolinguistic. Each

of them brings

something new to the understanding of the phenomenon. But due to this

diversity it

161

is

sometimes difficult for scholars to communicate with one another,

because they come from different traditions, use different

methodology and work on different data. Theories on

vocabulary acquisition are still in the process of developing.

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

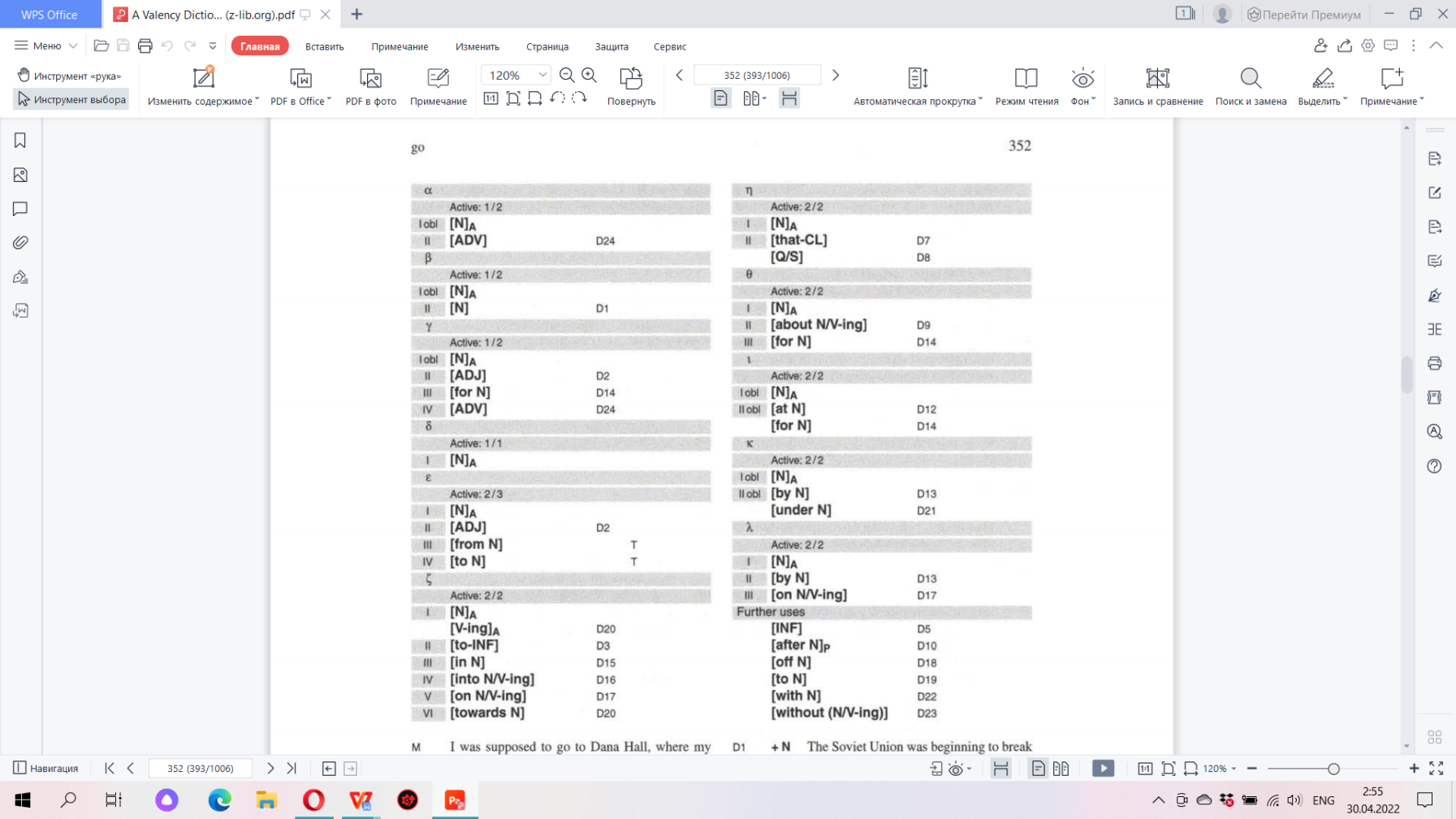

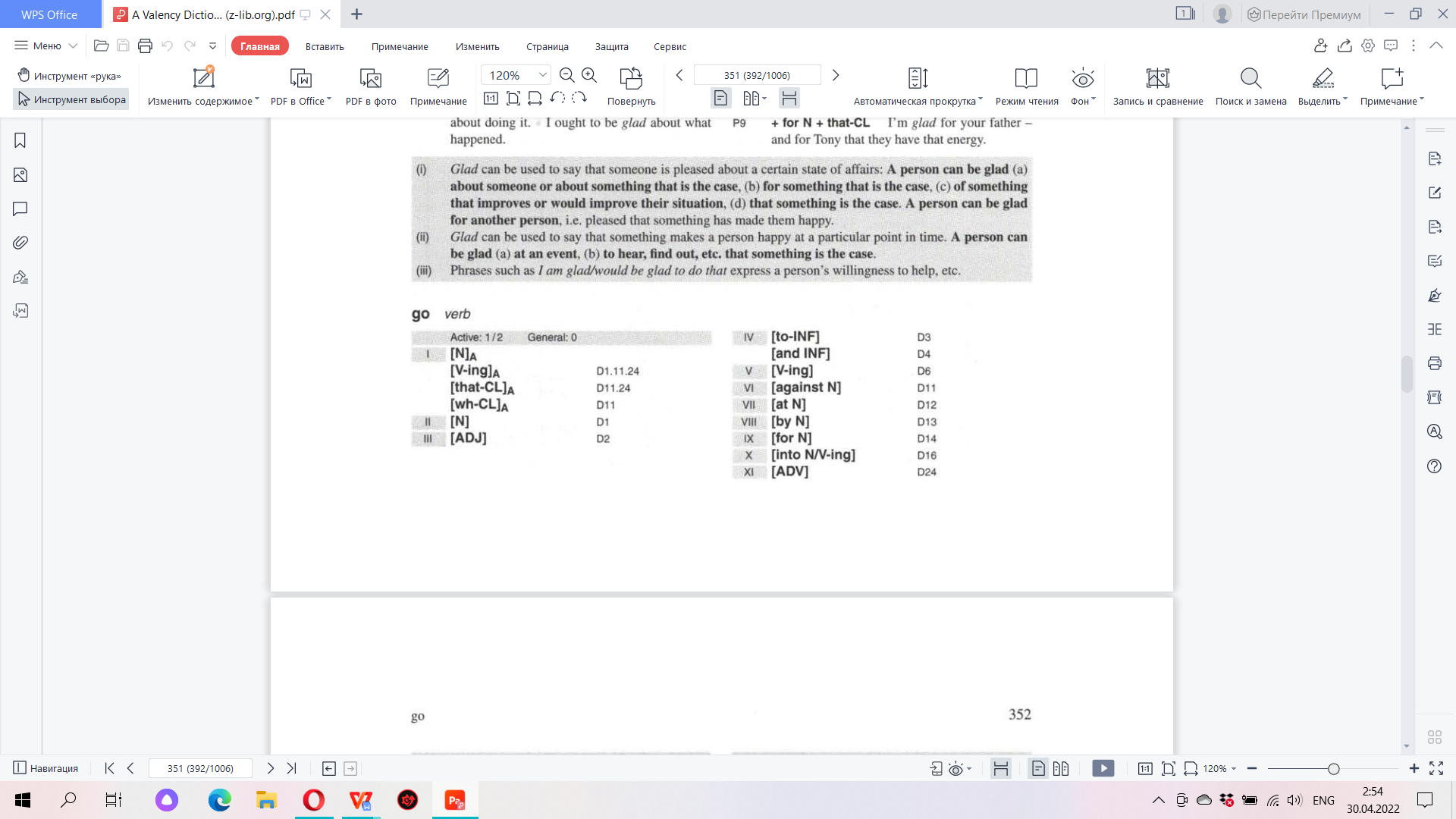

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |