A

morph is a phonological string (of phonemes) that cannot be broken

down into smaller constituents that have a lexico-grammatical

function. In some sense it corresponds to a word-form. An allomorph

is a morph that has a unique set of grammatical or lexical features.

All allomorphs with the same set of features forms a morpheme. A

morpheme, then, is a set of allomorphs that have the same set of

features. The morph ‘s’ is linked to three distinct allomorphs,

each containing a different set of features as indicated in the

morpheme class: if it is adjoined to a noun, then it marks the

plural; if it is adjoined to a verb, then it marks the third person

singular of the verb; if it is adjoined to a noun phrase, then it it

marks possession.

One

way to represent a morpheme is by listing its features ([+Past]).

Many linguists try to represent it by listing its chief allomorph if

there are more than one allomorph (‘s’). This is somewhat ambiguous

in that «s» could stand for three morphemes, and is not a

desirable way list a morpheme.

Each

morpheme may have a different set of allomorphs. For example, «-en»

is a second allomorph that marks plural in nouns (irregular, in only

three known nouns: ox/ox+en, child/childr+en, brother/brether+en).

The morph «-en» is linked to the allomorph «-en»,

which occurs in complementary distribution with «-s». When

the possessive is adjoined to a noun phrase, there is only one

phonological form, /s/, but it is written either as » ‘s »

or » s'». The inflectional pattern of English pronouns is

too complex to go into here. «-en» is a distinct morph

from «s».

Morph

is the phonetic realization of a morpheme which study the unit of

form, sounds and phonetic symbol. The morphs can be devided into two

important classes, lexical and grammatical.

Lexical

morph is the morph that denote directly objects actions, qualities

and other pieces of real word (ex : table, dog, walk, etc.)

Grammatical

morph is the morph that has been modifiying the meaning of the

lexical morphs by adding a certain element to them. (ex : un-,

-able, re-, -d, in-, -ent, -ly, -al, -ize, -a-, -tion, anti-, dis-,

-ment, -ari-, -an, -ism)

Allomorph

is variant form of morpheme about the sounds and phonetic symbols

but it doesn’t change the meaning. There are three types of

allomorph, phonologically, morphologically and lexically conditioned

allomorph.

So,

allomorph is variant form of a morpheme about the sounds and

phonetic symbol but it doesn’t change the meaning. Allomorph has

different in pronounciation and spelling according to their

condition. It means that allomorph will have different sound,

pronounciation or spelling in different condition.

6 The morpheme. Types of morpheme

In

linguistics, a morpheme

is the smallest component of word, or other linguistic unit, that

has semantic meaning. The term is used as part of the branch of

linguistics known as morpheme-based morphology. A morpheme is

composed by phoneme(s) (the smallest linguistically distinctive

units of sound) in spoken language, and by grapheme(s) (the smallest

units of written language) in written language.

The

concept of word and morpheme are different, a morpheme may or may

not stand alone. One or several morphemes compose a word. A morpheme

is free if it can stand alone (ex: «one», «possible»),

or bound if it is used exclusively alongside a free morpheme (ex:

«im» in impossible). Its actual phonetic representation is

the morph, with the different morphs («in-«, «im-«)

representing the same morpheme being grouped as its allomorphs.

The

word «unbreakable» has three morphemes: «un-«, a

bound morpheme; «break», a free morpheme; and «-able»,

a bound morpheme. «un-» is also a prefix, «-able»

is a suffix. Both «un-» and «-able» are affixes.

The

morpheme plural-s has the morph «-s», /s/, in cats

(/kæts/), but «-es», /ɨz/, in dishes (/dɪʃɨz/), and

even the voiced «-s», /z/, in dogs (/dɒɡz/). «-s».

These are allomorphs.

Types

of morphemes

Free

morphemes, like town and dog, can appear with other lexemes (as in

town hall or dog house) or they can stand alone, i.e., «free».

Bound

morphemes like «un-» appear only together with other

morphemes to form a lexeme. Bound morphemes in general tend to be

prefixes and suffixes. Unproductive, non-affix morphemes that exist

only in bound form are known as «cranberry» morphemes,

from the «cran» in that very word.

Derivational

morphemes can be added to a word to create (derive) another word:

the addition of «-ness» to «happy,» for example,

to give «happiness.» They carry semantic information.

Inflectional

morphemes modify a word’s tense, number, aspect, and so on, without

deriving a new word or a word in a new grammatical category (as in

the «dog» morpheme if written with the plural marker

morpheme «-s» becomes «dogs»). They carry

grammatical information.

Allomorphs

are variants of a morpheme, e.g., the plural marker in English is

sometimes realized as /-z/, /-s/ or /-ɨz/.

7. The

morphological systems of the English and Ukrainian

languages are characterized by a considerable number of isomorphic

and bysome allomorphic features. The isomorphic features are due to

the common Indo-European origin of the two languages while

theallomorphic features have been acquired by them in the course of

their historic development and functioning as independent

nationallanguages,Contrastive morphology deals with: a) the specific

traits of morphemes in languages under investigation; b) the parts

of speecharid their grammatical meanings (morphological

categories).The morpheme is a minimal meaningful unit, which may be

free!root, that is they can stand alone and do not depend on

othermorphemes in a word, and hound, that is they cannot stand

alone, they are bound to the root or to the stem consisting of the

root and oneor moreaffixal morphemes. Due to its historical

development, English has a much larger number of root morphemes than

Ukrainian.Consequently, the number of inflexions expressing the

morphological categories is much smaller in English than in

Ukrainian. E.g.: arm,pen, hoy. work, do, red, he, she, it, five,

ten, here:лоб,чуб,я,є,три

,тут,де,etc.Affixal

morphemes are represented in English and Ukrainian by suffixes or

prefixes.Suffixes in the contrasted languages, when added to the

root, change the form of thewords, adding some new shade to

their lexical meaning: duck…duckling:, four ..fourteen

—forty;

дитина-дитинча

.The number

of suffixes in the contrasted languages considerably exceeds the

number of prefixes. Among thenoun indicating suffixes in English are

-асу,-anee, -ion, -dom, -er, -ess, -hood, -ism, -Ity, -merit,

-ness, -ship and others. The adjectiveindicating suffixes are:

-able, -al, -k, -isfa, -ful, -less, -otis, -some» -y, etc.

The verb indicating suffixes are -ate, -en, -esee, -ify, -ize,

and.the adverb indicating suffixes -!y, -wards, -ways, Ukrainian

word-forming suffixes are more numerous and also more diverse by

theirnature because there exist special suffixes to identify

different genders of nouns. The masculine gender suffixes of nouns

in Ukrainianare —

ник,-ецьАєць,-ар/~яр,-up,

-ист,-тель,-аль.

Suffixes of

feminine gender in Ukrainian are: -к/а,-иц/я,-ec/a, -их/а,-ш/а.

Suffixesof

the neuter gender are mostly used in Ukrainian to identify

collective nouns, as in the nouns:

жіно-цтв-о,

6ади-лл- я.збі-жж-я

.Besides,inUkrainianthereexistiargegroupsofevaluativesuffixes(сон-ечк-о,кабан-юр-а)andpatronymicsuffixes:

-енк-о,-ук,-еоуь

(Бондаренко,Поліщук,Птшець).Prefixes

in the contrasted languages modify the lexical meaning of the word:

coexistence, unable

, підвид,

праліс, вбігати,вибігати.

Word-forming

prefixes pertain mostly io the English language where they can form

different parts of speech, Verbs; enable,disable, enclose.

Abjectives: pre-war, post-war. Adverbs! today, tomorrow, together.

Prepositions: below, behind. Conjunctions:because, unless, until. In

Ukrainian only some conjunctions and adverbs can be formed by means

of prefixes, for example:вдень,вночі.

Isomorphic

is also the use of two (in English) and more (in Ukrainian) prefixes

before the root: misrepresentation,oversubscription,

недовиторг.,

перерозподіл,etc.Inflexional morphemes in the contrasted

.languages express different morphological categories. The number

of genuinely Englishinflexions is restricted to noun inflexions:

-s/-es, -en, -ren (boys, watches, oxen, children); inflexions of the

comparative and thesuperlative degrees of qualitative adjectives:

~er, -est (bigger, biggest): inflexions of the comparative and the

superlative degrees of qualitative adverbs: -er, -est

(slowlier, slowliest); the verbal inflexions: ~s/-es, -d/-ed, -t,

-n/-en {he puts/watches; she learned therule/burnt the candle; a

broken -pencil); the inflexions of absolute possessive pronouns:

-s, -e (hers, ours, yours, mine, thine). Besides thegenuine

English inflexional morphemes, there exist some foreign inflexions

used with nouns of Latin, Greek and French origin only.Among them

Latin inflexions -um/-a(datum ……….. data);

-us/-i (terminus …… termini); -a/-ae

(formula …. formulae); -is/-es (thesis ……..theses);

Greek inflexions -on/-a (phenomenon— phenomena); -ion/-ia

(criterion— criteria). The number of inflexions in

Ukrainianexceeds their number in English since every national part

of speech has a variety of endings. They express number, case and

gender of nominal parts of speech and tense, aspect, person,

number, voice and mood of verbs:

червоний

— червоного — червоному — червоним;

двоє -двох — двом — двома;читаю

—читав — читала — читали

— читатиму-читатимеш-читатимете,etc

9. The

syntactico-distributional

classification of words is based on

the study of their combinability by means of substitution testing.

The testing results in developing the standard model of four main

«positions» of notional words in the English sentence:

those of the noun (N), verb (V), adjective (A), adverb (D).

Fries

chooses tape-recorded spontaneous conversations comprising

about 250,000 word entries (50 hours of talk). The words isolated

from this corpus are tested on the three typical sentences (that are

isolated from the records, too), and used as substitution

test-frames:

Frame A.

The concert was good (always).

Frame B.

The clerk remembered the tax

(suddenly).

Frame C.

The team went there.

As a result

of successive substitution tests on the cited «frames» the

following lists of positional words («form-words», or

«parts of speech») are established:

Class 1.

(A) concert, coffee, taste, container,

difference, etc. (B) clerk, husband, supervisor, etc.; tax, food,

coffee, etc. (C) team, husband, woman, etc.

Class 2.

(A) was, seemed, became, etc. (B)

remembered, wanted, saw, suggested, etc. (C) went, came, ran,…

lived, worked, etc.

Class 3.

(A) good, large, necessary, foreign,

new, empty, etc.

Class 4.

(A) there, here, always, then,

sometimes, etc. (B) clearly, sufficiently, especially,

repeatedly, soon, etc. (C) there, back, out, etc.; rapidly,

eagerly, confidently, etc.

All these

words can fill in the positions of the frames without affecting

their general structural meaning:

— the first

frame; «actor — action —

thing acted upon — characteristic of the action»

— the

second frame;

«actor — action — direction of the action»

— the third

frame.

Comparing

the syntactico-distributional classification of words with the

traditional part of speech division of words, one cannot but see the

similarity of the general schemes of the two: the opposition of

notional and functional words, the four absolutely cardinal classes

of notional words (since numerals and pronouns have no positional

functions of their own and serve as pro-nounal and pro-adjectival

elements), the interpretation of functional words as syntactic

mediators and their formal representation by the fist.

However,

under these unquestionable traits of similarity are distinctly

revealed essential features of difference, the proper evaluation of

which allows us to make some important generalizations about the

structure of the lexemic system of language.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

1

Первый слайд презентации

MORPHEMIC STRUCTURE OF THE WORD

Изображение слайда

T he morpheme is the elementary meaningful lingual unit built up from phonemes and used to make words.

It has meaning, but its meaning is abstract, significative, not concrete, or nominative, as is that of the word.

Morphemes constitute the words; they do not exist outside the words. Studying the morpheme we actually study the word: its inner structure, its functions, and the ways it enters speech.

Изображение слайда

Stating the differences between the word and the morpheme, we have to admit that the correlation between the word and the morpheme is problematic.

The borderlines between the morpheme and the word are by no means rigid and there is a set of intermediary units (half-words — half-morphemes), which form an area of transitions (a continuum) between the word and the morpheme as the polar phenomena.

Изображение слайда

This includes the so-called “morpheme-like” functional, or auxiliary words, for example, auxiliary verbs and adverbs, articles, particles, prepositions and conjunctions : they are realized as isolated, separate units (their separateness being fixed in written practice) but perform various grammatical functions; in other words, they function like morphemes and are dependent semantically to a greater or lesser extent. Cf..: Jack ’s, a boy, have done.

Изображение слайда

This approach to treating various lingual units is known in linguistics as “ a field approach ” : polar phenomena possessing the unambiguous characteristic features of the opposed units constitute “ the core ”, or “the center” of the field, while the intermediary phenomena combining some of the characteristics of the poles make up “ the periphery ” of the field; e.g.: functional words make up the periphery of the class of words since their functioning is close to the functioning of morphemes.

Изображение слайда

In traditional grammar, the study of the morphemic structure of the word is based on two criteria: the positional criterion — the location of the morphemes with regard to each other,

and the semantic (or functional ) criterion — the contribution of the morphemes to the general meaning of the word.

Изображение слайда

According to these criteria morphemes are divided into root-morphemes ( roots ) and affixal morphemes ( affixes ).

Roots express the concrete, “material” part of the meaning of the word and constitute its central part.

Изображение слайда

Affixes express the specificational part of the meaning of the word: they specify, or transform the meaning of the root.

Affixal specification may be of two kinds: of lexical or grammatical character.

Изображение слайда

So, according to the semantic criterion affixes are further subdivided into lexical, or word-building (derivational) affixes, which together with the root constitute the stem of the word, and grammatical, or word-changing affixes, expressing different morphological categories, such as number, case, tense and others.

With the help of lexical affixes new words are derived, or built;

with the help of grammatical affixes the form of the word is changed.

Изображение слайда

According to the positional criterion affixes are divided into prefixes, situated before the root in the word, e.g.: under -estimate, and suffixes, situated after the root, e.g.: underestim — ate.

Prefixes in English are only lexical : the word underestimate is derived from the word estimate with the help of the prefix under-.

Suffixes in English may be either lexical or grammatical ; e.g. in the word underestimates — ate is a lexical suffix, because it is used to derive the verb estimate (v) from the noun esteem (n), and –s is a grammatical suffix making the 3rd person, singular form of the verb to underestimate.

Grammatical suffixes are also called inflexions ( inflections, inflectional endings ).

Изображение слайда

Grammatical suffixes in English have certain peculiarities, which make them different from inflections in other languages: since they are the remnants of the old inflectional system, there are few (only six) remaining word-changing suffixes in English: -(e)s, — ed, — ing, — er, — est, — en ;

most of them are homonymous, e.g. -(e)s is used to form the plural of the noun (dogs ), the genitive of the noun (my friend’s), and the 3rd person singular of the verb ( works); some of them have lost their inflectional properties and can be attached to units larger than the word, e.g.: his daughter Mary’s arrival.

That is why the term “inflection” is seldom used to denote the grammatical components of words in English.

Изображение слайда

Grammatical suffixes form word-changing, or morphological paradigms of words, which can be observed to their full extent in inflectional languages, such as Russian, e.g.: стол – стола – столу – столом — о столе ; morphological paradigms exist, though not on the same scale, in English too, e.g., the number paradigm of the noun: boy — boys.

Изображение слайда

Lexical affixes are primarily studied by lexicology with regard to the meaning which they contribute to the general meaning of the whole word. In grammar word-building suffixes are studied as the formal marks of the words belonging to different parts of speech; they form lexical (word-building, derivational) paradigms of words united by a common root, cf.: to decide — decision — decisive — decisively to incise — incision — incisive — incisively

Изображение слайда

Being the formal marks of words of different parts of speech, word-building suffixes are also grammatically relevant. But grammar study is primarily concerned with grammatical, word-changing, or functional affixes, because they change the word according to its grammatical categories and serve to insert the word into an utterance.

Изображение слайда

The morphemic structure of the word can be analyzed in a linear way; for example, in the following way: underestimates — W= {[ Pr +(R+L)]+Gr}, where W denotes the word, R the root, L the lexical suffix, Pr the prefix, and Gr the grammatical suffix. In addition, the derivational history of the word can be hierarchically demonstrated as the so-called “tree of immediate constituents”; such analysis is called “IC-analysis”, IC standing for the “immediate constituents”. E.g.:

Изображение слайда

W __________

St 1 G____________

P St 2____________________

R L under/ estim / ate/ s

Изображение слайда

IC-analysis, like many other ideas employed in the study of the morphemes, was developed by an American linguist, Leonard Bloomfield, and his followers within the framework of an approach known as Descriptive Linguistics (or, Structural Linguistics).

Immediate constituents analysis in structural linguistics starts with lingual units of upper levels : for example, the immediate constituents of a composite sentence might be clauses, each clause in turn might have noun phrase and verb phrase as constituents, etc.; the analysis continues until the ultimate constituents – the morphemes – are reached.

Изображение слайда

Besides prefixes and suffixes, some other positional types of affix are distinguished in linguistics :

for example, regular vowel interchange which takes place inside the root and transforms its meaning “from within” can be treated as an infix, e.g.: a lexical infix – blood – to bleed ; a grammatical infix – tooth – teeth.

Grammatical infixes are also defined as inner inflections as opposed to grammatical suffixes which are called outer inflections.

Since infixation is not a productive (regular) means of word-building or word-changing in modern English, it is more often seen as partial suppletivity. Full suppletivity takes place when completely different roots are paradigmatically united, e.g.: go – went.

Изображение слайда

When studying morphemes, we should distinguish morphemes as generalized lingual units from their concrete manifestations, or variants in specific textual environments; variants of morphemes are called “ allo -morphs ”.

Изображение слайда

Initially, the so-called allo -emic theory was developed in phonetics: in phonetics, phonemes, as the generalized, invariant phonological units, are distinguished from their concrete realizations, the allophones.

For example, one phoneme is pronounced in a different way in different environments, cf.: you [ ju :] — you know [ ju ] ; in Russian, vowels are also pronounced in a different way in stressed and unstressed syllables, cf.: д о м — д о мой.

The same applies to the morpheme, which is a generalized unit, an invariant, and may be represented by different variants, allo -morphs, in different textual environments.

For example, the morpheme of the plural, -(e)s, sounds differently after voiceless consonants ( bats ), voiced consonants and vowels ( rooms ), and after fricative and sibilant consonants ( clashes ). So, [s], [z], [ iz ], which are united by the same meaning (the grammatical meaning of the plural), are allo -morphs of the same morpheme, which is represented as -(e)s in written speech.

Изображение слайда

The “ allo -emic theory” in the study of morphemes was also developed within the framework of Descriptive Linguistics by means of the so-called distributional analysis :

in the first stage of distributional analysis a syntagmatic chain of lingual units is divided into meaningful segments, morphs, e.g.: he/ start/ ed / laugh/ ing /;

then the recurrent segments are analyzed in various textual environments, and the following three types of distribution are established: contrastive distribution, non-contrastive distribution and complementary distribution.

Изображение слайда

The morphs are said to be in contrastive distribution if they express different meanings in identical environments the compared morphs, e.g.: He start ed laughing – He start s laughing ; such morphs constitute different morphemes.

The morphs are said to be in non-contrastive distribution if they express identical meaning in identical environments ; such morphs constitute ‘free variants’ of the same morpheme, e.g.: learn ed — learn t, ate [et] – ate [ eit ] (in Russian: трактор а – трактор ы ).

The morphs are said to be in complementary distribution if they express identical meanings in different environments, e.g.: He start ed laughing – He stopp ed laughing ; such morphs constitute variants, or allo -morphs of the same morpheme.

Изображение слайда

The allo -morphs of the plural morpheme -(e)s [s], [z], [ iz ] stand in phonemic complementary distribution; the allo -morph – en, as in oxen, stands in morphemic complementary distribution with the other allo -morphs of the plural morpheme.

Изображение слайда

Besides these traditional types of morphemes, in Descriptive Linguistics distributional morpheme types are distinguished; they immediately correlate with each other in the following pairs.

Free morphemes, which can build up words by themselves, are opposed to bound morphemes, used only as parts of words; e.g.: in the word ‘ hands’ hand- is a free morpheme and -s is a bound morpheme.

Изображение слайда

Overt and covert morphemes are opposed to each other: the latter shows the meaningful absence of a morpheme distinguished in the opposition of grammatical forms in paradigms; it is also known as the “zero morpheme”, e.g.: in the number paradigm of the noun, hand – hands, the plural is built with the help of an overt morpheme, hand-s, while the singular — with the help of a zero or covert morpheme, handØ.

Изображение слайда

Full or meaningful morphemes are opposed to empty morphemes, which have no meaning and are left after singling out the meaningful morphemes; some of them used to have a certain meaning, but lost it in the course of historical development, e.g.: in the word ‘children’ child- is the root of the word, bearing the core of the meaning, — en is the suffix of the plural, while -r- is an empty morpheme, having no meaning at all, the remnant of an old morphological form.

Изображение слайда

Segmental morphemes, consisting of phonemes, are opposed to supra-segmental morphemes, which leave the phonemic content of the word unchanged, but the meaning of the word is specified with the help of various supra-segmental lingual units, e.g.: `convert (a noun) — con`vert (a verb).

Изображение слайда

Additive morphemes, which are freely combined in a word, e.g.: look+ed, small+er, are opposed to replacive morphemes, or root morphemes, which replace each other in paradigms, e.g.: sing -sang – sung.

Изображение слайда

Continuous morphemes, combined with each other in the same word, e.g.: work ed, are opposed to discontinuous morphemes, which consist of two components used jointly to build the analytical forms of the words, e.g.: have work ed, is work ing.

Изображение слайда

Many of the distributional morpheme types contradict the traditional definition of the morpheme : traditionally the morpheme is the smallest meaningful lingual unit (this is contradicted by the “empty” morphemes type), built up by phonemes (this is contradicted by the “supra-segmental” morphemes type), used to build up words (this is contradicted by the “discontinuous” morphemes type).

This is due to the fact that in Descriptive Linguistics only three lingual units are distinguished: the phoneme, the morpheme, and syntactic constructions; the notion of the word is rejected because of the difficulties of defining it.

Изображение слайда

Still, the classification of distributional morpheme types can be used to summarize and differentiate various types of word-building and word-changing, though not all of them are morphemic in the current mainstream understanding of the term “morpheme”.

Изображение слайда

Morphology is the study of words and their parts. Morphemes, like prefixes, suffixes and base words, are defined as the smallest meaningful units of meaning. Morphemes are important for phonics in both reading and spelling, as well as in vocabulary and comprehension.

Why use morphology

Teaching morphemes unlocks the structures and meanings within words. It is very useful to have a strong awareness of prefixes, suffixes and base words. These are often spelt the same across different words, even when the sound changes, and often have a consistent purpose and/or meaning.

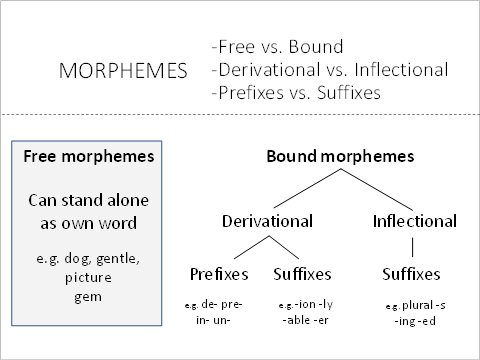

Types of morphemes

Free vs. bound

Morphemes can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes).

A free morpheme can stand alone as its own word

- gentle

- father

- licence

- picture

- gem

A bound morpheme only occurs as part of a word

- -s as in cat+s

- -ed as in crumb+ed

- un- as in un+happy

- mis- as in mis-fortune

- -er as in teach+er

In the example above: un+system+atic+al+ly, there is a root word (system) and bound morphemes that attach to the root (un-, -atic, -al, -ly)

system = root un-, -atic, -al, -ly = bound morphemes

If two free morphemes are joined together they create a compound word. These words are a great way to introduce morphology (the study of word parts) into the classroom.

For more details, see:

Compound words

Inflectional vs. derivational

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

Inflectional morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but does not create a new word.

For example, the word <skip> has many forms: skip (base form), skipping (present progressive), skipped (past tense).

The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word skip, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few suffixes added. So if you looked up <skip> in the dictionary, then only the base word <skip> would get its own entry into the dictionary. Skipping and skipped are listed under skip, as they are inflections of the base word. Skipping and skipped do not get their own dictionary entry.

Skip

verb, skipped, skipping.

- to move in a light, springy manner by bounding forward with alternate hops on each foot. to pass from one point, thing, subject, etc.,

- to another, disregarding or omitting what intervenes: He skipped through the book quickly.

- to go away hastily and secretly; flee without notice.

From

Dictionary.com — skip

Another example is <run>: run (base form), running (present progressive), ran (past tense). In this example the past tense marker changes the vowel of the word: run (rhymes with fun), to ran (rhymes with can). However, the inflectional morphemes -ing and past tense morpheme are added to the base word <run>, and are listed in the same dictionary entry.

Run

verb, ran, run, running.

- to go quickly by moving the legs more rapidly than at a walk and in such a manner that for an instant in each step all or both feet are off the ground.

- to move with haste; act quickly: Run upstairs and get the iodine.

- to depart quickly; take to flight; flee or escape: to run from danger.

From

Dictionary.com — run

Derivational morphemes are different to inflectional morphemes, as they do derive/create a new word, which gets its own entry in the dictionary. Derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

For example, we can create new words from <act> by adding derivational prefixes (e.g. re- en-) and suffixes (e.g. -or).

Thus out of <act> we can get re+act = react en+act = enact act+or = actor.

Whenever a derivational morpheme is added, a new word (and dictionary entry) is derived/created.

For the <act> example, the following dictionary entries can be found:

Act

noun

- anything done, being done, or to be done; deed; performance: a heroic act.

- the process of doing: caught in the act.

- a formal decision, law, or the like, by a legislature, ruler, court, or other authority; decree or edict; statute; judgement, resolve, or award: an act of Parliament.

From

Dictionary.com — act

React

verb

- to act in response to an agent or influence: How did the audience react to the speech?

- to act reciprocally upon each other, as two things.

- to act in a reverse direction or manner, especially so as to return to a prior condition.

From

Dictionary.com — react

Enact

verb

- to make into an act or statute: Parliament has enacted a new tax law.

- to represent on or as on the stage; act the part of: to enact Hamlet.

From

Dictionary.com — enact

Actor

noun

- a person who acts in stage plays, motion pictures, television broadcasts, etc.

- a person who does something; participant.

From

Dictionary.com — actor

Teachers should highlight and encourage students to analyse both Inflectional and Derivational morphemes when focussing on phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For more information, see:

Prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases

Many morphemes are very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. Morphemes can be divided into prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes (see example below)

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon Morphemes (like re-, un-, and -ness);

- Latin Morphemes (like non-, ex-, -ion, and -ify); and

- Greek Morphemes (like micro, photo, graph).

It is useful to highlight how words can be broken down into morphemes (and which each of these mean) and how they can be built up again).

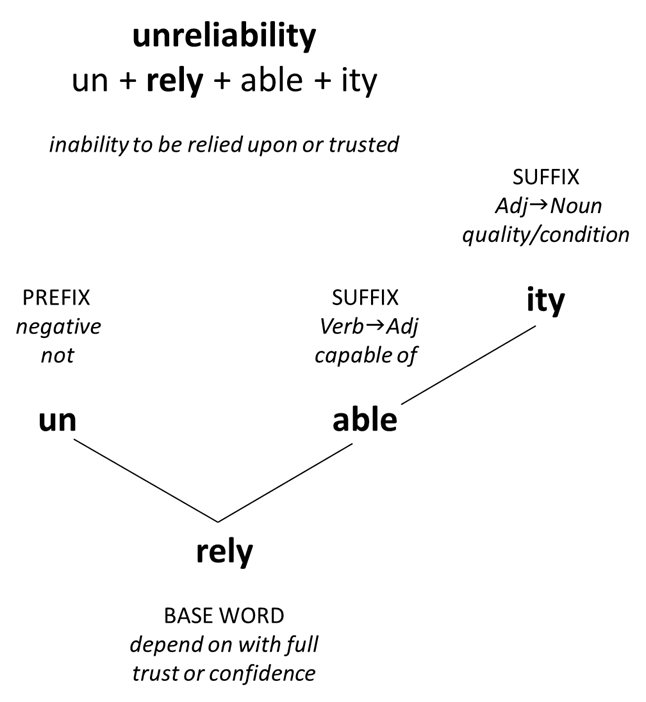

For example, the word <unreliability> may be unfamiliar to students when they first encounter it.

If <unreliability> is broken into its morphemes, students can deduce or infer the meaning.

So it is helpful for both reading and spelling to provide opportunities to analyse words, and become familiar with common morphemes, including their meaning and function.

Compound words

Compound words (or compounds) are created by joining free morphemes together. Remember that a free morpheme is a morpheme that can stand along as its own word (unlike bound morphemes — e.g. -ly, -ed, re-, pre-). Compounds are a fun and accessible way to introduce the idea that words can have multiple parts (morphemes). Teachers can highlight that these compound words are made up of two separate words joined together to make a new word. For example dog + house = doghouse

Examples

- lifetime

- basketball

- cannot

- fireworks

- inside

- upside

- footpath

- sunflower

- moonlight

- schoolhouse

- railroad

- skateboard

- meantime

- bypass

- sometimes

- airport

- butterflies

- grasshopper

- fireflies

- footprint

- something

- homemade

- backbone

- passport

- upstream

- spearmint

- earthquake

- backward

- football

- scapegoat

- eyeball

- afternoon

- sandstone

- meanwhile

- limestone

- keyboard

- seashore

- touchdown

- alongside

- subway

- toothpaste

- silversmith

- nearby

- raincheck

- blacksmith

- headquarters

- lukewarm

- underground

- horseback

- toothpick

- honeymoon

- bootstrap

- township

- dishwasher

- household

- weekend

- popcorn

- riverbank

- pickup

- bookcase

- babysitter

- saucepan

- bluefish

- hamburger

- honeydew

- thunderstorm

- spokesperson

- widespread

- hometown

- commonplace

- supermarket

Example activities of highlighting morphemes for phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension

There are numerous ways to highlight morphemes for the purpose of phonics, vocabulary and comprehension activities and lessons.

Highlighting the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules, as well as discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, and demonstrating how words are linked together. Highlighting and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies.

Examples of how to embed morphological awareness into literacy activities can include:

- Sorting words by base/root words (word families), or by prefixes or suffixes

- Word Detective — Students break longer words down into their prefixes, suffixes, and base words

- e.g. Find the morphemes in multi-morphemic words like: dissatisfied unstoppable ridiculously hydrophobic metamorphosis oxygenate fortifications

- Word Builder — students are given base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words they can build, and what meaning they might have:

- Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness -ment - Etymology investigation — students are given multi-morphemic words from texts they have been reading and are asked to research the origins (etymology) of the word. Teachers could use words like progressive, circumspect, revocation, and students could find out the morphemes within each word, their etymology, meanings, and use.

Morphology

The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed.

In linguistics, morphology is the study of word structure. While words are generally accepted as being the smallest units of syntax, it is clear that in most (if not all) languages, words can be related to other words by rules. For example, English speakers recognize that the words dog, dogs and dog-catcher are closely related. English speakers recognize these relations by virtue of the unconscious linguistic knowledge they have of the rules of word-formation processes in English. Therefore, these speakers intuit that dog is to dogs as cat is to cats; similarly, dog is to dogcatcher as dish is to dishwasher. The rules comprehended by the speaker in each case reflect specific patterns (or regularities) in the way words are formed from smaller units and how those smaller units interact in speech. In this way, morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies such patterns of word-formation across and within languages, and attempts to explicate formal rules reflective of the knowledge of the speakers of those languages.

In many languages, what appear to be single forms actually turn out to contain large number of ‘word-like’ elements. For examples, in Swahili (spoken through-out East Africa), form nitakupenda conveys what, in English, would have to be represented as something like I will love you. Now, is the Swahili form a single word? If it is a ‘word’, then it seems to consist of a number of elements which, in English, turn up as separate ‘words’. A rough correspondence can be presented in the following way:

ni -ta -ku -penda

I will you love

It would seem that this Swahili ‘word’ is rather different from what we think of as an English ‘word’. Yet, there clearly is some similarity between the languages, in that similar element of the whole message can be found in both. Perhaps a better way of looking at linguistic forms in different languages would be to use this notion of ‘elements’ in the message, rather than depend on identifying only ‘words’.

The type of exercise we have just performed is an example of investigating basic forms in language, generally known as morphology. This term, which literally means ‘the study of forms’, was originally used in biology, but, since, the middle of the nineteenth century, has also been used to describe the type of investigation that analyzes all those basic ‘elements’ used in a language. What we have been describing as ‘elements’ in the form of a linguistic message are technically known as ‘morphemes’.

Morphemes

A morpheme is the minimal linguistic unit which has a meaning or grammatical function. Although many people think of word as the basic meaningful elements of a language, many words can be broken down in to still smaller units, called morphemes. In English, for example, the word ripens consists of three morphemes: ripe plus en plus s. -En is a morpheme which changes adjectives into verb: ripe is an adjective, but ripen is a verb. Ripens is still a verb: the morpheme –s indicate that the subject of the verb is third person singular and that the action is neither past nor future.

A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a grammatical function. This definition is not meant to include all morphemes, but it is the usual one and a good starting point. A morpheme may consist of a word, such as hand, or a meaningful piece of a word, such as the –ed of looked, that cannot be divided into smaller meaningful parts. Another way in which morphemes have been defined is as a pairing between sound and meaning. We have purposely chosen not to use this definition. Some morphemes have no concrete form or no continuous form, as we will see, and some do not have meanings in the conventional sense of the term.

You may also run across the term morph. The term ‘morph’ is sometimes used to refer specifically to the phonological realization of a morpheme. For example, the English past tense morpheme that we spell -ed has various morphs. It is realized as [t] after the voiceless [p] of jump (cf. jumped), as [d] after the voiced [l] of repel (cf. repelled), and as [d] after the voiceless [t] of root or the voiced [d] of wed (cf. rooted and wedded). We can also call these morphs allomorphs or variants. The appearance of one morph over another in this case is determined by voicing and the place of articulation of the final consonant of the verb stem.

A single word may be composed of one or more morphemes:

one morphemes — boy

— desire

two morphemes — boy + ish

— desire + able

three morphemes — boy + ish + ness

— desire + able + ity

four morpheme — gentle + man + li + ness

— un + desire + able + ity

more than four — un + gentle + man + li + ness

— anti + dis + establish + ment + ari + an + ism

Those morphemes which can stand alone as words are said to be free morphemes, e.g. ripe and artichoke. Those which are always attached to some other morpheme are said to be bound, e.g. —en, -s, un-, pre-.

Notice that the term morpheme has been defined as “a minimal unit of meaning or grammatical function” to show that different morphemes serve different purposes. Some morphemes derive (create) new words by either changing the meaning (happy vs. unhappy, both adjectives) or the part of speech (syntactic category, e.g. ripe, an adjective, vs. ripen, a verb) or both. These are called derivational morphemes. Other morphemes changes neither part of speech nor meaning, but only refine and give extra grammatical information about the already existing meaning of a word. Thus, cat and cats are both nouns and have the same meaning (refer to the same thing), but cats, with the plural morpheme -s, contains the additional information that there are more than one of these things (Notice that the same information could be conveyed by including a number before the word – the plural -s marker then would not be needed at all). These morphemes which serve a purely grammatical function, never creating a different word, but only a different form of the same word, are called inflectional morphemes.

Both derivational and inflectional morphemes are bound forms and are called affixes. When they are attached to other morphemes they change the meaning or the grammatical function of the word in some way, as just seen; when added to the beginning of a word or morphemes they are called prefixes, and when added to the end of a word or morpheme they are called suffixes. For examples, unpremeditatedly has two prefixes (one added to the front of the other) and two suffixes (one added to the end of the other), all attached to the word meditate.

Below are listed four characteristic which separate inflectional and derivational affixes:

1. Inflectional Morphemes:

a. Do not change meaning or part of speech, e.g., big and bigger are both adjective.

b. Typically indicate syntactic or semantic relations between different words in a sentence, e.g.

c. The present tense morpheme –s in waits shows agreement with the subject of the verb (both are third person singular).

d. Typically occur with all members of some large class of morphemes, e.g. the plural morphemes occur with most nouns.

e. Typically occur at the margin of words, e.g., the plural morphemes –s always come last in a word, as in baby-sitters or rationalizations.

2. Derivational Morphemes:

a. Change meaning or part of speech, e.g. –ment forms nouns, such as judgment, from verbs, such as judge.

b. Typically indicate semantic relations within the word, e.g. the morpheme –ful in painful has no particular connection with any other morpheme beyond the word painful.

c. Typically occur with only some members of a class of morphemes, e.g., the suffix –hood occurs with just a few nouns such as brother, neighbor, and knight, but not with most others, e.g., friend, daughter, candle, etc.

d. Typically occur before inflectional suffixes, e.g., in chillier, the derivational suffix –y comes before the inflectional –er.

Now consider the word reconsideration. We can break it into three morphemes: re-, consider, and -ation. Consider is called the stem. A stem is a base morpheme to which another morphological piece is attached. The stem can be simple, made up of only one part, or complex, itself made up of more than one piece. Here it is best to consider consider a simple stem. Although it consists historically of more than one part, most present-day speakers would treat it as an unanalyzable form. We could also call consider the root. A root is like a stem in constituting the core of the word to which other pieces attach, but the term refers only to morphologically simple units. For example, disagree is the stem of disagreement, because it is the base to which -ment attaches, but agree is the root. Taking disagree now, agree is both the stem to which dis- attaches and the root of the entire word. Returning now to reconsideration, re- and -ation are both affixes, which means that they are attached to the stem. Affixes like re- that go before the stem are prefixes, and those like -ation that go after are suffixes.

Some readers may wonder why we have not broken -ation down further into two pieces, -ate and -ion, which function independently elsewhere. In this particular word they do not do so (cf. *reconsiderate), and hence we treat -ation as a single morpheme.

It is important to take very seriously the idea that the grammatical function of a morpheme, which may include its meaning, must be constant. Consider the English words lovely and quickly. They both end with the suffix -ly. But is it the same in both words? o – when we add —ly to the adjective quick, we create an adverb that describes how fast someone does something. But when we add -ly to the noun love, we create an adjective. What on the surface appears to be a single morpheme turns out to be two. One attaches to adjectives and creates adverbs; the other attaches to nouns and creates adjectives.

There are two other sorts of affixes that you will encounter, infixes and circumfixes. Both are classic challenges to the notion of morpheme. Infixes are segmental strings that do not attach to the front or back of a word, but rather somewhere in the middle. The Tagalog infix -um- is illustrated below (McCarthy and Prince 1993: 101–5; French 1988). It creates an agent from a verb stem and appears before the first vowel of the word:

(1) root —um—

/sulat/ /s-um-ulat/ ‘one who wrote’

/gradwet/ /gr-um-adwet/ ‘one who graduated’

(2) root believe verb

stem believe + able verb + suffix

word un + believe + able prefix + verb + suffix

(3) root Chomsky (proper) noun

stem Chomsky + ite noun + suffix

word Chomsky + ite + s noun + suffix + suffix

The existence of infixes challenges the traditional notion of a morpheme as an indivisible unit. We want to call the stem sulat ‘write’ a morpheme, and yet the infix -um- breaks it up. Yet this seems to be a property of –umrather than one of sulat. Our definition of morphemes as the smallest linguistic pieces with a grammatical function survives this challenge.

Circumfixes are affixes that come in two parts. One attaches to the front of the word, and the other to the back. Circumfixes are controversial because it is possible to analyze them as consisting of a prefix and a suffix that apply to a stem simultaneously. One example is Indonesian ke . . . -an. It applies to the stem besar ‘big’ to form a noun ke-besar-an meaning ‘bigness, greatness’ (MacDonald 1976: 63; Beard 1998: 62). Like infixes, the existence of circumfixes challenges the traditional notion of morpheme (but not the definition used here) because they involve discontinuity.

The inflectional Suffixes of English

|

Base |

Suffix |

Function |

|

Wait Wait Wait Eat Chair Chair Fast Fast |

-s -ed -ing -en -s -‘s -er -est |

3rd p sg present Past tense Progressive Past participle Plural marker Possessive Comparative adjective or adverb Superlative adjective or adverb |

The Classification of Morphemes

Free Morphemes.

Free morphemes are morphemes that can stand by themselves as single word. Examples: child, teach, kind, open, tour, etc. Free morphemes fall into two categories:

— Lexical Morphemes

Morphemes that set of ordinary nouns, adjectives and verbs that we think of as the words that carries the `content` of the message as we convey. Some example: tiger, yellow, sad, open, look, follow, etc.

— Functional Morphemes

Functional morphemes are morphemes that consist largely of the functional words in the language such as conjunctions, preposition, articles and pronouns. Example: and, but, above, when, because, in, the, that, it, etc.

Bound Morphemes

Morphemes which are can not normally stand alone and are typically attached to another form, example: re-, -ist, -ed, -s. They were identified as affixes. So we can say that affixes (prefixes and suffixes) in English are bound morphemes.

For example:

|

Undressed |

Carelessness |

||||

|

u- |

Dress |

-ed |

care |

-less |

-ness |

|

prefix |

Stem |

Suffix |

stem |

Suffix |

suffix |

|

(bound) |

(free) |

(bound) |

(free) |

(bound) |

(bound) |

Bound morphemes fall into two categories:

— Derivational Morphemes

Morphemes that are used to make new words or to make words of a different grammatical category from the stem, for example the additional of the derivational morpheme -ness change the adjective good to the noun goodness. The noun care can become the adjective careful or careless by the addition of the derivational morpheme –ful or –less. A list of derivational morphemes will include suffixes such as the –ish in foolish, and the -ment in payment. The list will also include prefixes such as re-, pre-, ex-, mis-, co-, un-, and many more.

— Inflectional Morphemes

These are not used to produce new words in the language, but rather to indicate aspects of grammatical function of a word. In flectional, morphemes are used to show if a word is plural or singular, if it is past tense or not and if it is comparative or possessive form. English has only eight inflectional morphemes (or ‘inflections’), illustrated in the following sentences.

Jim’s two sisters are really different.

One likes to have fun and is always laughing.

The other liked to read as child and has always taken things seriously.

One is the loudest person in the house in the other is quitter than a mouse.

From these examples, we can see that two of the inflection. –‘s (possessive) and –s plural, are attached to nouns. They are four inflections attached to verbs, -s (3rd person singular), —ing (present participle), -ed (past tense), and –en (past participle). There are two inflections attached to adjective –est (superlative) and –er (comparative).

Noun + -s. –s

Verb + -s, -ing, -ed, -en

Adj + -est, er.

Allomorph

In the preceding chapters, it was assumed that every morpheme has only one form. In reality, languages are more complex; morphemes frequently have more than one form. For example, the English perfect tense. Suffix for some verbs is the same as the past tense form (divided, mended while for other verbs, the perfect tense form is the suffix –en (written, given), and the stem /rait/ write is changed to /rit/ and combined with the perfect tense suffix, to form written.

In order to account for the various forms or given morpheme, linguistics have posited a type of pseudomorpheme called morph. Morph are isolated by the procedures. In fact, had we been speaking precisely, each of the units discovered by those initial procedures would have been called a morph, rather than a morpheme. Morphs may be said to represent morpheme, a morpheme may be represented by one or more morphs. The various morphs which represent one morpheme are called allomorphs.

Two or more morphs are allomorphs of a single morpheme if they have the same meaning and are in complementary distribution i.e., never in contrast in the same context. This is only a working definition, too simplistic to cover all the questions that arise in morpheme identification. But it is a beginning, and some of the problems involved will be discussed below.

By comparing the above forms, ree go out, bani wake up, etc. can be identified, leaving the first CV. (consonant-vowels sequence) of each form as some kind of prefix. The completive aspect morpheme, indicated by bl-, has only one form in data. The habitual aspect, however is indicated by two different forms: ru- and ri-. To conclude that these two morphs are allomorphs of a single morpheme, it must be determined that they carry the same meaning and that they are in complementary distribution. A quick inspection reveals that ru- and ri- do not occur with the same stems.

Morphological Analysis

Words are analyzed morphologically with the same terminology used to describe different sentence types:

— a simple word has one free root, e.g., hand.

— a complex word has a free root and one or more bound morphs, or two or more bound morphs, e.g., unhand, handy, handful.

— a compound word has two free roots, e.g., handbook, handrail, handgun

— a compound-complex word has two free roots and associated bound morphs, e.g., handwriting, handicraft.

Morphological Analysis versus Morphemic Analysis

The importance of the distinction between morph and morpheme is that there is not always a one-to-one correspondence between morph and morpheme, and morphemes can combine or be realized in a number of different ways. We can thus analyze words in two different ways: in morphological analysis, words are analyzed into morphs following formal divisions, while in morphemic analysis, words are analyzed into morphemes, recognizing the abstract units of meaning present.

If we start first with nouns, we would arrive at the two analyses of each of the following two words:

Morphological Analysis Morphemic Analysis

Writers 3 morphs writ/er/s 3 morphemes {WRITE} + {-ER} + {pl}

Authors 2 morphs author/s 2 morphemes {AUTHOR} + {pl}

Mice 1 morph mice 2 morphemes {MOUSE} + {pl}

Fish 1 morph fish 2 morphemes {FISH} + {pl}

Children 2 morphs child/ren 2 morphemes {CHILD} + {pl}

Man’s 2 morphs man/s 2 morphemes {MAN} + {poss}

Men’s 2 morphs men/s 3 morphemes {MAN} + {pl} + {poss}.

You should note that the morphemes, since they are abstractions, can be represented any way one wants, but it is customary to use lexemes for roots and descriptive designations for inflectional morphemes, such as {pi} rather than {-S} for the plural marker and {poss} rather than {-S} for the possessive marker, since these can often be realized by a number of different forms. The descriptive designations that we will use should be self-evident in the following discussion (also see the list of abbreviations in Appendix I).

A noun such as sheep raises a difficulty for morphemic analysis, since it is either singular or plural. Should we postulate two morphemic analyses?

{SHEEP} + {p1}

{SHEEP} + {sg}

This seems a good idea. If we postulate a morpheme for singular, even though it’s never realized, we can account for number systematically. Thus, we will analyze singular nouns as containing an abstract {sg} morpheme, so that man’s above would have the analysis {MAN} + {sg} + {poss}, writer the analysis {WRITE} + {-ER} + {sg}, and author the analysis {AUTHOR} + {sg}.

Let us look at how morphological and morphemic analysis works in adjective:

Morphological Analysis Morphemic Analysis

Smaller 2morphs small/er 2morphemes {SMALL} + {compr}

Smallest 2morphs small/est 2morphemes {SMALL} + {supl}

Better 1morph better 2morphemes {GOOD} + {compr}

Best 1morph best 2morphemes {GOOD} + {supl}

(Here, compr = comparative degree and supl = (superlative degreee). Again we need to postulate a morpheme positive degree {pos}, even though it is never realized, to account systematically for the inflected forms of adjectives:

good 1morp good 2morphemes {GOOD} + {pos}

For verbs, the two analyses work as follows:

Morphological Analysis Morphemic Analysis

Worked 2morphs work/ed 2morphemes {WORK} + {past}

2morphemes {WORK} + {pstprt}

Wrote 1morph wrote 2morphemes {WRITE} + {past}

Written 1morph written 2morphemes {WRITE} + {pstprt}

Working 2morphs work/ing 2morphemes {WORK} + {pstprt}

3morphemes {WORK} + {gerund} + {sg}

Put 1morph put 2morphemes {PUT} + {past}

2morphemes {PUT} + {pstprt}

We have to analyze -ing verbal forms not only as present participles, but also as “gerunds”, or verbal nouns, as in Swimming is good exercise. Since gerunds are functioning as nouns, they may sometimes be pluralized, e.g.:

Sitting 3 morphs sitt/ing/s 3 morphemes {SIT} + {gerund} + {pl}

We need to postulate a morpheme {pres}, which is never realized, to account coherently for the distinction past versus present.

Work 1 morph work 2 morphemes {WORK} + {pres}

The morphemic analysis of pronouns is somewhat more complicated:

Morphological Analysis Morphemic Analysis

We 1 morph we 3 morphemes {1st p} + {pl} + {nomn}

Him 1 morph him 3 morphemes {3rd p} + {sg} + {m} + {obj}

Its 2 morphs it/s 3 morphemes {3rd p} + {sg} + {n} + {poss}

Morphemes combine and are realized by one of four morphological realization rules:

1. Agglutinative rule – two morphemes are realized by morphs which remain distinct and are simply “glued” together, e.g. {WRITER} + {pl} > weiters.

2. Fusional rule – two morphemes are realized by morphs which do not remain distinct but are fused together, e.g., {TOOTH} + {pl} > teeth.

3. Null realization rule – a morpheme is never realized as a morph in any word of the relevant class, e.g., {sg} on nouns, which never has concrete realization in English.

4. Zero-rule – a morpheme is realized as a zero morph in particular members of a word class, e.g., {SHEEP} + {pl} > sheep. Note that in most other members of the class noun, {pl} has concrete realization as –s.

References

Brinton, Laurel J (2000). The Structure Of Modern English: A Linguistic Introduction. Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing Company.

Fromklin, V. et.al (2001). An introduction to the teory of word structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Goldberg, Adele (1995). Constructions. A construction-based approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Team work (2008). Selected Readings For Morphology. Malang: The Stated Islamic University of Malang.

Tata. A.M. Green Module Phonology, Morphology, Syntax & Semantics. Self-Circle.

Verhaar. Dr. John W.M. general Linguistic. Jogjakarta. Gajah Mada University Pers.