Where does the word reason come from?

The origin of the word reason is found in the Latin verb reri, which means to think.

What do you mean good reasons?

If people think you show good reason, or are reasonable, it means you think things through. If people think you have a good reason for doing something, it means you have a motive that makes sense.

What is reason example?

Reason is the cause for something to happen or the power of your brain to think, understand and engage in logical thought. An example of reason is when you are late because your car ran out of gas. An example of reason is the ability to think logically. noun.

Is for good reason?

It’s a shortening (of sorts) of “for a good reason”, so it means there’s a good reason that something happened. For example, imagine if you were complaining that a friend wasn’t talking to you anymore. The person you’re speaking to might say “And for good reason!

What is a synonym for have a good reason?

The quality of being justifiable by reason. logic. reason. sense. rationale.

How do you use and for good reason?

How to use ‘and for good reason ‘ in a sentence

- …

- We treat noncompliance with disdain, and for good reason.

- … debilitating illnesses.

- …

- The belief in skinwalkers, common among so many Navajos, is the one that bothers him most and for good reason.

- Thorvald Solberg was the first and longest serving Register of Copyrights.

What is another name for good?

What is another word for good?

| excellent | exceptional |

|---|---|

| nice | pleasant |

| positive | satisfactory |

| satisfying | superb |

| wonderful | acceptable |

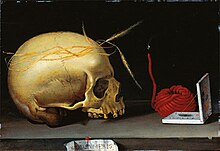

What makes something good or bad?

Good, in this context, is anything that is morally admirable and thus the opposite, which is evil, would be morally condemnatory. Determining if something is good or bad is a decision, a verdict. Looking at this, we can say that part of deciding whether something is good or bad is comparison.

Is changes good or bad?

Change is not always a good thing. It may force us out of tired habits and impose better ones upon us, but it can also be stressful, costly and even destructive. What’s important about change is how we anticipate it and react to it.

What makes an evil man?

To be truly evil, someone must have sought to do harm by planning to commit some morally wrong action with no prompting from others (whether this person successfully executes his or her plan is beside the point).

What are the 3 types of evil?

According to Leibniz, there are three forms of evil in the world: moral, physical, and metaphysical.

What does God say about wickedness?

Proverbs 11:5 KJV. The righteousness of the perfect shall direct his way: but the wicked shall fall by his own wickedness.

What is the biblical definition of wickedness?

The International Bible Encyclopedia (ISBE) gives this definition of wicked according to the Bible: “The state of being wicked; a mental disregard for justice, righteousness, truth, honor, virtue; evil in thought and life; depravity; sinfulness; criminality.”

What is the meaning of wickedness?

1 : the quality or state of being wicked. 2 : something wicked.

Is wickedness a sin?

Wickedness is generally considered a synonym for evil or sinfulness. As characterized by Martin Buber in his 1952 work Bilder von Gut und Böse (translated as Good and Evil: Two Interpretations), “The first stage of evil is ‘sin,’ occasional directionlessness.

What defines an evil person?

1. Morally bad or wrong; wicked: an evil tyrant. 2. Causing ruin, injury, or pain; harmful: the evil effects of a poor diet.

What is the difference between wickedness and evil?

The difference between Evil and Wicked. When used as nouns, evil means moral badness, whereas wicked means people who are wicked. When used as adjectives, evil means intending to harm, whereas wicked means evil or mischievous by nature. Wicked is also adverb with the meaning: very, extremely.

Is Sin same as evil?

Christian hamartiology describes sin as an act of offense against God by despising his persons and Christian biblical law, and by injuring others. In Christian views it is an evil human act, which violates the rational nature of man as well as God’s nature and his eternal law.

Can we overcome sin?

We cannot become holy on our own. God gives us his spirit to help us obey his word. He gives us the power to overcome sin. In Hebrews 12:14, we are told, “Make every effort to live in peace with all men and to be holy; without holiness, no one will see the Lord.”

How does God view sin?

Scripture clearly indicates that God does view sin differently and that He proscribed a different punishment for sin depending upon its severity. “But when Christ had offered for all time a single sacrifice for sins, he sat down at the right hand of God” (Hebrews 10:12 ESV).

Why is adultery a sin?

Adultery is viewed not only as a sin between an individual and God but as an injustice that reverberates through society by harming its fundamental unit, the family: Adultery is an injustice. He who commits adultery fails in his commitment.

This article is about the human faculty of reason and rationality. For other uses, see Reason (disambiguation).

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth.[1][2] It is closely[how?] associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, language, mathematics, and art, and is normally considered to be a distinguishing ability possessed by humans.[3] Reason is sometimes referred to as rationality.[4]

Reasoning is associated with the acts of thinking and cognition, and involves the use of one’s intellect. The field of logic studies the ways in which humans can use formal reasoning to produce logically valid arguments.[5] Reasoning may be subdivided into forms of logical reasoning, such as deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning, and abductive reasoning. Aristotle drew a distinction between logical discursive reasoning (reason proper), and intuitive reasoning,[6] in which the reasoning process through intuition—however valid—may tend toward the personal and the subjectively opaque. In some social and political settings logical and intuitive modes of reasoning may clash, while in other contexts intuition and formal reason are seen as complementary rather than adversarial. For example, in mathematics, intuition is often necessary for the creative processes involved with arriving at a formal proof, arguably the most difficult of formal reasoning tasks.

Reasoning, like habit or intuition, is one of the ways by which thinking moves from one idea to a related idea. For example, reasoning is the means by which rational individuals understand sensory information from their environments, or conceptualize abstract dichotomies such as cause and effect, truth and falsehood, or ideas regarding notions of good or evil. Reasoning, as a part of executive decision making, is also closely identified with the ability to self-consciously change, in terms of goals, beliefs, attitudes, traditions, and institutions, and therefore with the capacity for freedom and self-determination.[7]

In contrast to the use of «reason» as an abstract noun, a reason is a consideration given which either explains or justifies events, phenomena, or behavior.[8] Reasons justify decisions, reasons support explanations of natural phenomena; reasons can be given to explain the actions (conduct) of individuals.

Using reason, or reasoning, can also be described more plainly as providing good, or the best, reasons. For example, when evaluating a moral decision, «morality is, at the very least, the effort to guide one’s conduct by reason—that is, doing what there are the best reasons for doing—while giving equal [and impartial] weight to the interests of all those affected by what one does.»[9]

Psychologists and cognitive scientists have attempted to study and explain how people reason, e.g. which cognitive and neural processes are engaged, and how cultural factors affect the inferences that people draw. The field of automated reasoning studies how reasoning may or may not be modeled computationally. Animal psychology considers the question of whether animals other than humans can reason.

Etymology and related words[edit]

In the English language and other modern European languages, «reason», and related words, represent words which have always been used to translate Latin and classical Greek terms in the sense of their philosophical usage.

- The original Greek term was «λόγος» logos, the root of the modern English word «logic» but also a word which could mean for example «speech» or «explanation» or an «account» (of money handled).[10]

- As a philosophical term logos was translated in its non-linguistic senses in Latin as ratio. This was originally not just a translation used for philosophy, but was also commonly a translation for logos in the sense of an account of money.[11]

- French raison is derived directly from Latin, and this is the direct source of the English word «reason».[8]

The earliest major philosophers to publish in English, such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke also routinely wrote in Latin and French, and compared their terms to Greek, treating the words «logos«, «ratio«, «raison» and «reason» as interchangeable. The meaning of the word «reason» in senses such as «human reason» also overlaps to a large extent with «rationality» and the adjective of «reason» in philosophical contexts is normally «rational», rather than «reasoned» or «reasonable».[12] Some philosophers, Thomas Hobbes for example, also used the word ratiocination as a synonym for «reasoning».

Philosophical history[edit]

The proposal that reason gives humanity a special position in nature has been argued to be a defining characteristic of western philosophy and later western modern science, starting with classical Greece. Philosophy can be described as a way of life based upon reason, and in the other direction, reason has been one of the major subjects of philosophical discussion since ancient times. Reason is often said to be reflexive, or «self-correcting», and the critique of reason has been a persistent theme in philosophy.[13] It has been defined in different ways, at different times, by different thinkers about human nature.

Classical philosophy[edit]

For many classical philosophers, nature was understood teleologically, meaning that every type of thing had a definitive purpose that fit within a natural order that was itself understood to have aims. Perhaps starting with Pythagoras or Heraclitus, the cosmos is even said to have reason.[14] Reason, by this account, is not just one characteristic that humans happen to have, and that influences happiness amongst other characteristics. Reason was considered of higher stature than other characteristics of human nature, such as sociability, because it is something humans share with nature itself, linking an apparently immortal part of the human mind with the divine order of the cosmos itself. Within the human mind or soul (psyche), reason was described by Plato as being the natural monarch which should rule over the other parts, such as spiritedness (thumos) and the passions. Aristotle, Plato’s student, defined human beings as rational animals, emphasizing reason as a characteristic of human nature. He defined the highest human happiness or well being (eudaimonia) as a life which is lived consistently, excellently, and completely in accordance with reason.[15]

The conclusions to be drawn from the discussions of Aristotle and Plato on this matter are amongst the most debated in the history of philosophy.[16] But teleological accounts such as Aristotle’s were highly influential for those who attempt to explain reason in a way that is consistent with monotheism and the immortality and divinity of the human soul. For example, in the neoplatonist account of Plotinus, the cosmos has one soul, which is the seat of all reason, and the souls of all individual humans are part of this soul. Reason is for Plotinus both the provider of form to material things, and the light which brings individuals souls back into line with their source.[17]

Christian and Islamic philosophy[edit]

The classical view of reason, like many important Neoplatonic and Stoic ideas, was readily adopted by the early Church [18] as the Church Fathers saw Greek Philosophy as an indispensable instrument given to mankind so that we may understand revelation.[19] For example, the greatest among the early saint Church Fathers and Doctors of the Church such as Augustine of Hippo, Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa were as much Neoplatonic philosophers as they were Christian theologians and adopted the Neoplatonic view of human reason together with the associated implications for our relationship to creation, to ourselves and to God. Such Neoplatonist accounts of the rational part of the human soul were also standard amongst medieval Islamic philosophers and remain important in Iranian philosophy.[16] As European intellectualism recovered from the post-Roman Dark Ages, the Christian Patristic heritage and the influence of the great Islamic scholars such as Averroes and Avicenna produced the Scholastic (see Scholasticism) view of reason from which our modern idea of this concept has developed.[20] Among the Scholastics who relied on the classical concept of reason for the development of their doctrines, none were more influential than Saint Thomas Aquinas, who put this concept at the heart of his Natural Law. In this doctrine, Thomas concludes that because humans have reason and because reason is a spark of the divine, every single human life is invaluable, all humans are equal and every human is born with an intrinsic and permanent set of basic rights.[21] On this foundation, the idea of human rights would later be constructed by Spanish theologians at the School of Salamanca. Other Scholastics, such as Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus, following the example of Islamic scholars such as Alhazen, emphasised reason an intrinsic human ability to decode the created order and the structures that underlie our experienced physical reality. This interpretation of reason was instrumental to the development of the scientific method in the early Universities of the high Middle Ages.[22]

Subject-centred reason in early modern philosophy[edit]

The early modern era was marked by a number of significant changes in the understanding of reason, starting in Europe. One of the most important of these changes involved a change in the metaphysical understanding of human beings. Scientists and philosophers began to question the teleological understanding of the world.[23] Nature was no longer assumed to be human-like, with its own aims or reason, and human nature was no longer assumed to work according to anything other than the same «laws of nature» which affect inanimate things. This new understanding eventually displaced the previous world view that derived from a spiritual understanding of the universe.

Accordingly, in the 17th century, René Descartes explicitly rejected the traditional notion of humans as «rational animals», suggesting instead that they are nothing more than «thinking things» along the lines of other «things» in nature. Any grounds of knowledge outside that understanding was, therefore, subject to doubt.

In his search for a foundation of all possible knowledge, Descartes deliberately decided to throw into doubt all knowledge – except that of the mind itself in the process of thinking:

At this time I admit nothing that is not necessarily true. I am therefore precisely nothing but a thinking thing; that is a mind, or intellect, or understanding, or reason – words of whose meanings I was previously ignorant.[24]

This eventually became known as epistemological or «subject-centred» reason, because it is based on the knowing subject, who perceives the rest of the world and itself as a set of objects to be studied, and successfully mastered by applying the knowledge accumulated through such study. Breaking with tradition and many thinkers after him, Descartes explicitly did not divide the incorporeal soul into parts, such as reason and intellect, describing them as one indivisible incorporeal entity.

A contemporary of Descartes, Thomas Hobbes described reason as a broader version of «addition and subtraction» which is not limited to numbers.[25] This understanding of reason is sometimes termed «calculative» reason. Similar to Descartes, Hobbes asserted that «No discourse whatsoever, can end in absolute knowledge of fact, past, or to come» but that «sense and memory» is absolute knowledge.[26]

In the late 17th century, through the 18th century, John Locke and David Hume developed Descartes’s line of thought still further. Hume took it in an especially skeptical direction, proposing that there could be no possibility of deducing relationships of cause and effect, and therefore no knowledge is based on reasoning alone, even if it seems otherwise.[27][28]

Hume famously remarked that, «We speak not strictly and philosophically when we talk of the combat of passion and of reason. Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.»[29] Hume also took his definition of reason to unorthodox extremes by arguing, unlike his predecessors, that human reason is not qualitatively different from either simply conceiving individual ideas, or from judgments associating two ideas,[30] and that «reason is nothing but a wonderful and unintelligible instinct in our souls, which carries us along a certain train of ideas, and endows them with particular qualities, according to their particular situations and relations.»[31] It followed from this that animals have reason, only much less complex than human reason.

In the 18th century, Immanuel Kant attempted to show that Hume was wrong by demonstrating that a «transcendental» self, or «I», was a necessary condition of all experience. Therefore, suggested Kant, on the basis of such a self, it is in fact possible to reason both about the conditions and limits of human knowledge. And so long as these limits are respected, reason can be the vehicle of morality, justice, aesthetics, theories of knowledge (epistemology), and understanding.

Substantive and formal reason[edit]

In the formulation of Kant, who wrote some of the most influential modern treatises on the subject, the great achievement of reason (German: Vernunft) is that it is able to exercise a kind of universal law-making. Kant was able therefore to reformulate the basis of moral-practical, theoretical and aesthetic reasoning, on «universal» laws.

Here practical reasoning is the self-legislating or self-governing formulation of universal norms, and theoretical reasoning the way humans posit universal laws of nature.[32]

Under practical reason, the moral autonomy or freedom of human beings depends on their ability to behave according to laws that are given to them by the proper exercise of that reason. This contrasted with earlier forms of morality, which depended on religious understanding and interpretation, or nature for their substance.[33]

According to Kant, in a free society each individual must be able to pursue their goals however they see fit, so long as their actions conform to principles given by reason. He formulated such a principle, called the «categorical imperative», which would justify an action only if it could be universalized:

Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.[34]

In contrast to Hume then, Kant insists that reason itself (German Vernunft) has natural ends, the solution to the metaphysical problems, especially the discovery of the foundations of morality. Kant claimed that this problem could be solved with his «transcendental logic» which unlike normal logic is not just an instrument, which can be used indifferently, as it was for Aristotle, but a theoretical science in its own right and the basis of all the others.[35]

According to Jürgen Habermas, the «substantive unity» of reason has dissolved in modern times, such that it can no longer answer the question «How should I live?» Instead, the unity of reason has to be strictly formal, or «procedural». He thus described reason as a group of three autonomous spheres (on the model of Kant’s three critiques):

- Cognitive–instrumental reason is the kind of reason employed by the sciences. It is used to observe events, to predict and control outcomes, and to intervene in the world on the basis of its hypotheses;

- Moral–practical reason is what we use to deliberate and discuss issues in the moral and political realm, according to universalizable procedures (similar to Kant’s categorical imperative); and

- Aesthetic reason is typically found in works of art and literature, and encompasses the novel ways of seeing the world and interpreting things that those practices embody.

For Habermas, these three spheres are the domain of experts, and therefore need to be mediated with the «lifeworld» by philosophers. In drawing such a picture of reason, Habermas hoped to demonstrate that the substantive unity of reason, which in pre-modern societies had been able to answer questions about the good life, could be made up for by the unity of reason’s formalizable procedures.[36]

The critique of reason[edit]

Hamann, Herder, Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Rorty, and many other philosophers have contributed to a debate about what reason means, or ought to mean. Some, like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Rorty, are skeptical about subject-centred, universal, or instrumental reason, and even skeptical toward reason as a whole. Others, including Hegel, believe that it has obscured the importance of intersubjectivity, or «spirit» in human life, and attempt to reconstruct a model of what reason should be.

Some thinkers, e.g. Foucault, believe there are other forms of reason, neglected but essential to modern life, and to our understanding of what it means to live a life according to reason.[13]

In the last several decades, a number of proposals have been made to «re-orient» this critique of reason, or to recognize the «other voices» or «new departments» of reason:

For example, in opposition to subject-centred reason, Habermas has proposed a model of communicative reason that sees it as an essentially cooperative activity, based on the fact of linguistic intersubjectivity.[37]

Nikolas Kompridis has proposed a widely encompassing view of reason as «that ensemble of practices that contributes to the opening and preserving of openness» in human affairs, and a focus on reason’s possibilities for social change.[38]

The philosopher Charles Taylor, influenced by the 20th century German philosopher Martin Heidegger, has proposed that reason ought to include the faculty of disclosure, which is tied to the way we make sense of things in everyday life, as a new «department» of reason.[39]

In the essay «What is Enlightenment?», Michel Foucault proposed a concept of critique based on Kant’s distinction between «private» and «public» uses of reason. This distinction, as suggested, has two dimensions:

- Private reason is the reason that is used when an individual is «a cog in a machine» or when one «has a role to play in society and jobs to do: to be a soldier, to have taxes to pay, to be in charge of a parish, to be a civil servant».

- Public reason is the reason used «when one is reasoning as a reasonable being (and not as a cog in a machine), when one is reasoning as a member of reasonable humanity». In these circumstances, «the use of reason must be free and public.»[40]

[edit]

Compared to logic[edit]

The terms logic or logical are sometimes used as if they were identical with the term reason or with the concept of being rational, or sometimes logic is seen as the most pure or the defining form of reason: «Logic is about reasoning—about going from premises to a conclusion. … When you do logic, you try to clarify reasoning and separate good from bad reasoning.»[41] In modern economics, rational choice is assumed to equate to logically consistent choice.[42]

Reason and logic can however be thought of as distinct, although logic is one important aspect of reason. Author Douglas Hofstadter, in Gödel, Escher, Bach, characterizes the distinction in this way: Logic is done inside a system while reason is done outside the system by such methods as skipping steps, working backward, drawing diagrams, looking at examples, or seeing what happens if you change the rules of the system.[43] Psychologists Mark H. Bickard and Robert L. Campbell argued that «rationality cannot be simply assimilated to logicality»; they noted that «human knowledge of logic and logical systems has developed» over time through reasoning, and logical systems «can’t construct new logical systems more powerful than themselves», so reasoning and rationality must involve more than a system of logic.[44][45] Psychologist David Moshman, citing Bickhard and Campbell, argued for a «metacognitive conception of rationality» in which a person’s development of reason «involves increasing consciousness and control of logical and other inferences».[45][46]

Reason is a type of thought, and logic involves the attempt to describe a system of formal rules or norms of appropriate reasoning.[45] The oldest surviving writing to explicitly consider the rules by which reason operates are the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, especially Prior Analysis and Posterior Analysis.[47][non-primary source needed] Although the Ancient Greeks had no separate word for logic as distinct from language and reason, Aristotle’s newly coined word «syllogism» (syllogismos) identified logic clearly for the first time as a distinct field of study.[48] When Aristotle referred to «the logical» (hē logikē), he was referring more broadly to rational thought.[49]

Reason compared to cause-and-effect thinking, and symbolic thinking[edit]

As pointed out by philosophers such as Hobbes, Locke and Hume, some animals are also clearly capable of a type of «associative thinking», even to the extent of associating causes and effects. A dog once kicked, can learn how to recognize the warning signs and avoid being kicked in the future, but this does not mean the dog has reason in any strict sense of the word. It also does not mean that humans acting on the basis of experience or habit are using their reason.[50]

Human reason requires more than being able to associate two ideas, even if those two ideas might be described by a reasoning human as a cause and an effect, perceptions of smoke, for example, and memories of fire. For reason to be involved, the association of smoke and the fire would have to be thought through in a way which can be explained, for example as cause and effect. In the explanation of Locke, for example, reason requires the mental use of a third idea in order to make this comparison by use of syllogism.[51]

More generally, reason in the strict sense requires the ability to create and manipulate a system of symbols, as well as indices and icons, according to Charles Sanders Peirce, the symbols having only a nominal, though habitual, connection to either smoke or fire.[52] One example of such a system of artificial symbols and signs is language.

The connection of reason to symbolic thinking has been expressed in different ways by philosophers. Thomas Hobbes described the creation of «Markes, or Notes of remembrance» (Leviathan Ch. 4) as speech. He used the word speech as an English version of the Greek word logos so that speech did not need to be communicated.[53] When communicated, such speech becomes language, and the marks or notes or remembrance are called «Signes» by Hobbes. Going further back, although Aristotle is a source of the idea that only humans have reason (logos), he does mention that animals with imagination, for whom sense perceptions can persist, come closest to having something like reasoning and nous, and even uses the word «logos» in one place to describe the distinctions which animals can perceive in such cases.[54]

Reason, imagination, mimesis, and memory[edit]

Reason and imagination rely on similar mental processes.[55] Imagination is not only found in humans. Aristotle, for example, stated that phantasia (imagination: that which can hold images or phantasmata) and phronein (a type of thinking that can judge and understand in some sense) also exist in some animals.[56] According to him, both are related to the primary perceptive ability of animals, which gathers the perceptions of different senses and defines the order of the things that are perceived without distinguishing universals, and without deliberation or logos. But this is not yet reason, because human imagination is different.

The recent modern writings of Terrence Deacon and Merlin Donald, writing about the origin of language, also connect reason connected to not only language, but also mimesis.[57] More specifically they describe the ability to create language as part of an internal modeling of reality specific to humankind. Other results are consciousness, and imagination or fantasy. In contrast, modern proponents of a genetic predisposition to language itself include Noam Chomsky and Steven Pinker, to whom Donald and Deacon can be contrasted.

As reason is symbolic thinking, and peculiarly human, then this implies that humans have a special ability to maintain a clear consciousness of the distinctness of «icons» or images and the real things they represent. Starting with a modern author, Merlin Donald writes[58]

A dog might perceive the «meaning» of a fight that was realistically play-acted by humans, but it could not reconstruct the message or distinguish the representation from its referent (a real fight). […] Trained apes are able to make this distinction; young children make this distinction early – hence, their effortless distinction between play-acting an event and the event itself

In classical descriptions, an equivalent description of this mental faculty is eikasia, in the philosophy of Plato.[59] This is the ability to perceive whether a perception is an image of something else, related somehow but not the same, and therefore allows humans to perceive that a dream or memory or a reflection in a mirror is not reality as such. What Klein refers to as dianoetic eikasia is the eikasia concerned specifically with thinking and mental images, such as those mental symbols, icons, signes, and marks discussed above as definitive of reason. Explaining reason from this direction: human thinking is special in the way that we often understand visible things as if they were themselves images of our intelligible «objects of thought» as «foundations» (hypothēses in Ancient Greek). This thinking (dianoia) is «…an activity which consists in making the vast and diffuse jungle of the visible world depend on a plurality of more ‘precise’ noēta«.[60]

Both Merlin Donald and the Socratic authors such as Plato and Aristotle emphasize the importance of mimesis, often translated as imitation or representation. Donald writes[61]

Imitation is found especially in monkeys and apes [… but …] Mimesis is fundamentally different from imitation and mimicry in that it involves the invention of intentional representations. […] Mimesis is not absolutely tied to external communication.

Mimēsis is a concept, now popular again in academic discussion, that was particularly prevalent in Plato’s works, and within Aristotle, it is discussed mainly in the Poetics. In Michael Davis’s account of the theory of man in this work.[62]

It is the distinctive feature of human action, that whenever we choose what we do, we imagine an action for ourselves as though we were inspecting it from the outside. Intentions are nothing more than imagined actions, internalizings of the external. All action is therefore imitation of action; it is poetic…[63]

Donald like Plato (and Aristotle, especially in On Memory and Recollection), emphasizes the peculiarity in humans of voluntary initiation of a search through one’s mental world. The ancient Greek anamnēsis, normally translated as «recollection» was opposed to mneme or memory. Memory, shared with some animals,[64] requires a consciousness not only of what happened in the past, but also that something happened in the past, which is in other words a kind of eikasia[65] «…but nothing except man is able to recollect.»[66] Recollection is a deliberate effort to search for and recapture something once known. Klein writes that, «To become aware of our having forgotten something means to begin recollecting.»[67] Donald calls the same thing autocueing, which he explains as follows:[68] «Mimetic acts are reproducible on the basis of internal, self-generated cues. This permits voluntary recall of mimetic representations, without the aid of external cues – probably the earliest form of representational thinking.»

In a celebrated paper in modern times, the fantasy author and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in his essay «On Fairy Stories» that the terms «fantasy» and «enchantment» are connected to not only «….the satisfaction of certain primordial human desires….» but also «…the origin of language and of the mind».

Logical reasoning methods and argumentation[edit]

A subdivision of philosophy is logic. Logic is the study of reasoning. Looking at logical categorizations of different types of reasoning, the traditional main division made in philosophy is between deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. Formal logic has been described as the science of deduction.[69] The study of inductive reasoning is generally carried out within the field known as informal logic or critical thinking.

Deductive reasoning[edit]

Deduction is a form of reasoning in which a conclusion follows necessarily from the stated premises. A deduction is also the conclusion reached by a deductive reasoning process. One classic example of deductive reasoning is that found in syllogisms like the following:

- Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

- Premise 2: Socrates is a human.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

The reasoning in this argument is deductively valid because there is no way in which the premises, 1 and 2, could be true and the conclusion, 3, be false.

Inductive reasoning[edit]

Induction is a form of inference producing propositions about unobserved objects or types, either specifically or generally, based on previous observation. It is used to ascribe properties or relations to objects or types based on previous observations or experiences, or to formulate general statements or laws based on limited observations of recurring phenomenal patterns.

Inductive reasoning contrasts strongly with deductive reasoning in that, even in the best, or strongest, cases of inductive reasoning, the truth of the premises does not guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Instead, the conclusion of an inductive argument follows with some degree of probability. Relatedly, the conclusion of an inductive argument contains more information than is already contained in the premises. Thus, this method of reasoning is ampliative.

A classic example of inductive reasoning comes from the empiricist David Hume:

- Premise: The sun has risen in the east every morning up until now.

- Conclusion: The sun will also rise in the east tomorrow.

Analogical reasoning[edit]

Analogical reasoning is a form of inductive reasoning from a particular to a particular. It is often used in case-based reasoning, especially legal reasoning.[70] An example follows:

- Premise 1: Socrates is human and mortal.

- Premise 2: Plato is human.

- Conclusion: Plato is mortal.

Analogical reasoning is a weaker form of inductive reasoning from a single example, because inductive reasoning typically uses a large number of examples to reason from the particular to the general.[71] Analogical reasoning often leads to wrong conclusions. For example:

- Premise 1: Socrates is human and male.

- Premise 2: Ada Lovelace is human.

- Conclusion: Ada Lovelace is male.

Abductive reasoning[edit]

Abductive reasoning, or argument to the best explanation, is a form of reasoning that doesn’t fit in deductive or inductive, since it starts with incomplete set of observations and proceeds with likely possible explanations so the conclusion in an abductive argument does not follow with certainty from its premises and concerns something unobserved. What distinguishes abduction from the other forms of reasoning is an attempt to favour one conclusion above others, by subjective judgement or attempting to falsify alternative explanations or by demonstrating the likelihood of the favoured conclusion, given a set of more or less disputable assumptions. For example, when a patient displays certain symptoms, there might be various possible causes, but one of these is preferred above others as being more probable.

Fallacious reasoning[edit]

Flawed reasoning in arguments is known as fallacious reasoning. Bad reasoning within arguments can be because it commits either a formal fallacy or an informal fallacy.

Formal fallacies occur when there is a problem with the form, or structure, of the argument. The word «formal» refers to this link to the form of the argument. An argument that contains a formal fallacy will always be invalid.

An informal fallacy is an error in reasoning that occurs due to a problem with the content, rather than mere structure, of the argument.

Traditional problems raised concerning reason[edit]

Philosophy is sometimes described as a life of reason, with normal human reason pursued in a more consistent and dedicated way than usual. Two categories of problem concerning reason have long been discussed by philosophers concerning reason, essentially being reasonings about reasoning itself as a human aim, or philosophizing about philosophizing. The first question is concerning whether we can be confident that reason can achieve knowledge of truth better than other ways of trying to achieve such knowledge. The other question is whether a life of reason, a life that aims to be guided by reason, can be expected to achieve a happy life more so than other ways of life (whether such a life of reason results in knowledge or not).

Reason versus truth, and «first principles»[edit]

Since classical times a question has remained constant in philosophical debate (which is sometimes seen as a conflict between movements called Platonism and Aristotelianism) concerning the role of reason in confirming truth. People use logic, deduction, and induction, to reach conclusions they think are true. Conclusions reached in this way are considered, according to Aristotle, more certain than sense perceptions on their own.[72] On the other hand, if such reasoned conclusions are only built originally upon a foundation of sense perceptions, then, our most logical conclusions can never be said to be certain because they are built upon the very same fallible perceptions they seek to better.[73]

This leads to the question of what types of first principles, or starting points of reasoning, are available for someone seeking to come to true conclusions. In Greek, «first principles» are archai, «starting points»,[74] and the faculty used to perceive them is sometimes referred to in Aristotle[75] and Plato[76] as nous which was close in meaning to awareness or consciousness.[77]

Empiricism (sometimes associated with Aristotle[78] but more correctly associated with British philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume, as well as their ancient equivalents such as Democritus) asserts that sensory impressions are the only available starting points for reasoning and attempting to attain truth. This approach always leads to the controversial conclusion that absolute knowledge is not attainable. Idealism, (associated with Plato and his school), claims that there is a «higher» reality, from which certain people can directly arrive at truth without needing to rely only upon the senses, and that this higher reality is therefore the primary source of truth.

Philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Maimonides, Aquinas and Hegel are sometimes said to have argued that reason must be fixed and discoverable—perhaps by dialectic, analysis, or study. In the vision of these thinkers, reason is divine or at least has divine attributes. Such an approach allowed religious philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas and Étienne Gilson to try to show that reason and revelation are compatible. According to Hegel, «…the only thought which Philosophy brings with it to the contemplation of History, is the simple conception of reason; that reason is the Sovereign of the World; that the history of the world, therefore, presents us with a rational process.»[79]

Since the 17th century rationalists, reason has often been taken to be a subjective faculty, or rather the unaided ability (pure reason) to form concepts. For Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz, this was associated with mathematics. Kant attempted to show that pure reason could form concepts (time and space) that are the conditions of experience. Kant made his argument in opposition to Hume, who denied that reason had any role to play in experience.

Reason versus emotion or passion[edit]

After Plato and Aristotle, western literature often treated reason as being the faculty that trained the passions and appetites.[citation needed] Stoic philosophy, by contrast, claimed most emotions were merely false judgements.[80][81] According to the stoics the only good is virtue, and the only evil is vice, therefore emotions that judged things other than vice to be bad (such as fear or distress), or things other than virtue to be good (such as greed) were simply false judgements and should be discarded (though positive emotions based on true judgements, such as kindness, were acceptable).[80][81][82] After the critiques of reason in the early Enlightenment the appetites were rarely discussed or conflated with the passions.[citation needed] Some Enlightenment camps took after the Stoics to say Reason should oppose Passion rather than order it, while others like the Romantics believed that Passion displaces Reason, as in the maxim «follow your heart».[citation needed]

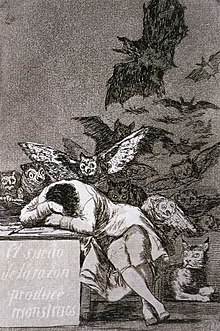

Reason has been seen as cold, an «enemy of mystery and ambiguity»,[83] a slave, or judge, of the passions, notably in the work of David Hume, and more recently of Freud.[citation needed] Reasoning which claims that the object of a desire is demanded by logic alone is called rationalization.[citation needed]

Rousseau first proposed, in his second Discourse, that reason and political life is not natural and possibly harmful to mankind.[84] He asked what really can be said about what is natural to mankind. What, other than reason and civil society, «best suits his constitution»? Rousseau saw «two principles prior to reason» in human nature. First we hold an intense interest in our own well-being. Secondly we object to the suffering or death of any sentient being, especially one like ourselves.[85] These two passions lead us to desire more than we could achieve. We become dependent upon each other, and on relationships of authority and obedience. This effectively puts the human race into slavery. Rousseau says that he almost dares to assert that nature does not destine men to be healthy. According to Richard Velkley, «Rousseau outlines certain programs of rational self-correction, most notably the political legislation of the Contrat Social and the moral education in Émile. All the same, Rousseau understands such corrections to be only ameliorations of an essentially unsatisfactory condition, that of socially and intellectually corrupted humanity.»

This quandary presented by Rousseau led to Kant’s new way of justifying reason as freedom to create good and evil. These therefore are not to be blamed on nature or God. In various ways, German Idealism after Kant, and major later figures such Nietzsche, Bergson, Husserl, Scheler, and Heidegger, remain preoccupied with problems coming from the metaphysical demands or urges of reason.[86] The influence of Rousseau and these later writers is also large upon art and politics. Many writers (such as Nikos Kazantzakis) extol passion and disparage reason. In politics modern nationalism comes from Rousseau’s argument that rationalist cosmopolitanism brings man ever further from his natural state.[87]

Another view on reason and emotion was proposed in the 1994 book titled Descartes’ Error by Antonio Damasio. In it, Damasio presents the «Somatic Marker Hypothesis» which states that emotions guide behavior and decision-making. Damasio argues that these somatic markers (known collectively as «gut feelings») are «intuitive signals» that direct our decision making processes in a certain way that cannot be solved with rationality alone. Damasio further argues that rationality requires emotional input in order to function.

Reason versus faith or tradition[edit]

There are many religious traditions, some of which are explicitly fideist and others of which claim varying degrees of rationalism. Secular critics sometimes accuse all religious adherents of irrationality, since they claim such adherents are guilty of ignoring, suppressing, or forbidding some kinds of reasoning concerning some subjects (such as religious dogmas, moral taboos, etc.).[88] Though the theologies and religions such as classical monotheism typically do not admit to be irrational, there is often a perceived conflict or tension between faith and tradition on the one hand, and reason on the other, as potentially competing sources of wisdom, law and truth.[89][90]

Religious adherents sometimes respond by arguing that faith and reason can be reconciled, or have different non-overlapping domains, or that critics engage in a similar kind of irrationalism:

- Reconciliation: Philosopher Alvin Plantinga argues that there is no real conflict between reason and classical theism because classical theism explains (among other things) why the universe is intelligible and why reason can successfully grasp it.[91][92]

- Non-overlapping magisteria: Evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould argues that there need not be conflict between reason and religious belief because they are each authoritative in their own domain (or «magisterium»).[93][94] If so, reason can work on those problems over which it has authority while other sources of knowledge or opinion can have authority on the big questions.[95]

- Tu quoque: Philosophers Alasdair MacIntyre and Charles Taylor argue that those critics of traditional religion who are adherents of secular liberalism are also sometimes guilty of ignoring, suppressing, and forbidding some kinds of reasoning about subjects.[96][97] Similarly, philosophers of science such as Paul Feyarabend argue that scientists sometimes ignore or suppress evidence contrary to the dominant paradigm.

- Unification: Theologian Joseph Ratzinger, later Benedict XVI, asserted that «Christianity has understood itself as the religion of the Logos, as the religion according to reason,» referring to John 1:Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, usually translated as «In the beginning was the Word (Logos).» Thus, he said that the Christian faith is «open to all that is truly rational», and that the rationality of Western Enlightenment «is of Christian origin».[98]

Some commentators have claimed that Western civilization can be almost defined by its serious testing of the limits of tension between «unaided» reason and faith in «revealed» truths—figuratively summarized as Athens and Jerusalem, respectively.[99][100] Leo Strauss spoke of a «Greater West» that included all areas under the influence of the tension between Greek rationalism and Abrahamic revelation, including the Muslim lands. He was particularly influenced by the great Muslim philosopher Al-Farabi. To consider to what extent Eastern philosophy might have partaken of these important tensions, Strauss thought it best to consider whether dharma or tao may be equivalent to Nature (by which we mean physis in Greek). According to Strauss the beginning of philosophy involved the «discovery or invention of nature» and the «pre-philosophical equivalent of nature» was supplied by «such notions as ‘custom’ or ‘ways‘«, which appear to be really universal in all times and places. The philosophical concept of nature or natures as a way of understanding archai (first principles of knowledge) brought about a peculiar tension between reasoning on the one hand, and tradition or faith on the other.[101]

Although there is this special history of debate concerning reason and faith in the Islamic, Christian and Jewish traditions, the pursuit of reason is sometimes argued to be compatible with the other practice of other religions of a different nature, such as Hinduism, because they do not define their tenets in such an absolute way.[102]

Reason in particular fields of study[edit]

Psychology and cognitive science[edit]

Scientific research into reasoning is carried out within the fields of psychology and cognitive science. Psychologists attempt to determine whether or not people are capable of rational thought in a number of different circumstances.

Assessing how well someone engages in reasoning is the project of determining the extent to which the person is rational or acts rationally. It is a key research question in the psychology of reasoning and cognitive science of reasoning. Rationality is often divided into its respective theoretical and practical counterparts.

Behavioral experiments on human reasoning[edit]

Experimental cognitive psychologists carry out research on reasoning behaviour. Such research may focus, for example, on how people perform on tests of reasoning such as intelligence or IQ tests, or on how well people’s reasoning matches ideals set by logic (see, for example, the Wason test).[103] Experiments examine how people make inferences from conditionals e.g., If A then B and how they make inferences about alternatives, e.g., A or else B.[104] They test whether people can make valid deductions about spatial and temporal relations, e.g., A is to the left of B, or A happens after B, and about quantified assertions, e.g., All the A are B.[105] Experiments investigate how people make inferences about factual situations, hypothetical possibilities, probabilities, and counterfactual situations.[106]

Developmental studies of children’s reasoning[edit]

Developmental psychologists investigate the development of reasoning from birth to adulthood. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development was the first complete theory of reasoning development. Subsequently, several alternative theories were proposed, including the neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development.[107]

Neuroscience of reasoning[edit]

The biological functioning of the brain is studied by neurophysiologists, cognitive neuroscientists and neuropsychologists. Research in this area includes research into the structure and function of normally functioning brains, and of damaged or otherwise unusual brains. In addition to carrying out research into reasoning, some psychologists, for example, clinical psychologists and psychotherapists work to alter people’s reasoning habits when they are unhelpful.

Computer science[edit]

Automated reasoning[edit]

In artificial intelligence and computer science, scientists study and use automated reasoning for diverse applications including automated theorem proving the formal semantics of programming languages, and formal specification in software engineering.

Meta-reasoning[edit]

Meta-reasoning is reasoning about reasoning. In computer science, a system performs meta-reasoning when it is reasoning about its own operation.[108] This requires a programming language capable of reflection, the ability to observe and modify its own structure and behaviour.

Evolution of reason[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

Dan Sperber believes that reasoning in groups is more effective and promotes their evolutionary fitness.

A species could benefit greatly from better abilities to reason about, predict and understand the world. French social and cognitive scientists Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier argue that there could have been other forces driving the evolution of reason. They point out that reasoning is very difficult for humans to do effectively, and that it is hard for individuals to doubt their own beliefs (confirmation bias). Reasoning is most effective when it is done as a collective – as demonstrated by the success of projects like science. They suggest that there are not just individual, but group selection pressures at play. Any group that managed to find ways of reasoning effectively would reap benefits for all its members, increasing their fitness. This could also help explain why humans, according to Sperber, are not optimized to reason effectively alone. Their argumentative theory of reasoning claims that reason may have more to do with winning arguments than with the search for the truth.[109][110]

Reason in political philosophy and ethics[edit]

Aristotle famously described reason (with language) as a part of human nature, which means that it is best for humans to live «politically» meaning in communities of about the size and type of a small city state (polis in Greek). For example…

It is clear, then, that a human being is more of a political [politikon = of the polis] animal [zōion] than is any bee or than any of those animals that live in herds. For nature, as we say, makes nothing in vain, and humans are the only animals who possess reasoned speech [logos]. Voice, of course, serves to indicate what is painful and pleasant; that is why it is also found in other animals, because their nature has reached the point where they can perceive what is painful and pleasant and express these to each other. But speech [logos] serves to make plain what is advantageous and harmful and so also what is just and unjust. For it is a peculiarity of humans, in contrast to the other animals, to have perception of good and bad, just and unjust, and the like; and the community in these things makes a household or city [polis]. […] By nature, then, the drive for such a community exists in everyone, but the first to set one up is responsible for things of very great goodness. For as humans are the best of all animals when perfected, so they are the worst when divorced from law and right. The reason is that injustice is most difficult to deal with when furnished with weapons, and the weapons a human being has are meant by nature to go along with prudence and virtue, but it is only too possible to turn them to contrary uses. Consequently, if a human being lacks virtue, he is the most unholy and savage thing, and when it comes to sex and food, the worst. But justice is something political [to do with the polis], for right is the arrangement of the political community, and right is discrimination of what is just. (Aristotle’s Politics 1253a 1.2. Peter Simpson’s translation, with Greek terms inserted in square brackets.)

The concept of human nature being fixed in this way, implied, in other words, that we can define what type of community is always best for people. This argument has remained a central argument in all political, ethical and moral thinking since then, and has become especially controversial since firstly Rousseau’s Second Discourse, and secondly, the Theory of Evolution. Already in Aristotle there was an awareness that the polis had not always existed and had needed to be invented or developed by humans themselves. The household came first, and the first villages and cities were just extensions of that, with the first cities being run as if they were still families with Kings acting like fathers.[111]

Friendship [philia] seems to prevail [in] man and woman according to nature [kata phusin]; for people are by nature [tēi phusei] pairing [sunduastikon] more than political [politikon = of the polis], in as much as the household [oikos] is prior [proteron = earlier] and more necessary than the polis and making children is more common [koinoteron] with the animals. In the other animals, community [koinōnia] goes no further than this, but people live together [sumoikousin] not only for the sake of making children, but also for the things for life; for from the start the functions [erga] are divided, and are different [for] man and woman. Thus they supply each other, putting their own into the common [eis to koinon]. It is for these [reasons] that both utility [chrēsimon] and pleasure [hēdu] seem to be found in this kind of friendship. (Nicomachean Ethics, VIII.12.1162a. Rough literal translation with Greek terms shown in square brackets.)

Rousseau in his Second Discourse finally took the shocking step of claiming that this traditional account has things in reverse: with reason, language and rationally organized communities all having developed over a long period of time merely as a result of the fact that some habits of cooperation were found to solve certain types of problems, and that once such cooperation became more important, it forced people to develop increasingly complex cooperation—often only to defend themselves from each other.

In other words, according to Rousseau, reason, language and rational community did not arise because of any conscious decision or plan by humans or gods, nor because of any pre-existing human nature. As a result, he claimed, living together in rationally organized communities like modern humans is a development with many negative aspects compared to the original state of man as an ape. If anything is specifically human in this theory, it is the flexibility and adaptability of humans. This view of the animal origins of distinctive human characteristics later received support from Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

The two competing theories concerning the origins of reason are relevant to political and ethical thought because, according to the Aristotelian theory, a best way of living together exists independently of historical circumstances. According to Rousseau, we should even doubt that reason, language and politics are a good thing, as opposed to being simply the best option given the particular course of events that lead to today. Rousseau’s theory, that human nature is malleable rather than fixed, is often taken to imply, for example by Karl Marx, a wider range of possible ways of living together than traditionally known.

However, while Rousseau’s initial impact encouraged bloody revolutions against traditional politics, including both the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution, his own conclusions about the best forms of community seem to have been remarkably classical, in favor of city-states such as Geneva, and rural living.

See also[edit]

- Argument

- Argumentation theory

- Confirmation bias

- Conformity

- Critical thinking

- Logic and rationality

- Outline of thought – topic tree that identifies many types of thoughts/thinking, types of reasoning, aspects of thought, related fields, and more.

- Outline of human intelligence – topic tree presenting the traits, capacities, models, and research fields of human intelligence, and more.

- Common sense

References[edit]

- ^ Proudfoot, Michael (2010). The Routledge dictionary of philosophy. A. R. Lacey, A. R.. Lacey (4th ed.). London: Routledge. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-203-42846-7. OCLC 503050369.

Reason: A general faculty common to all or nearly all humans…this faculty has seemed to be of two sorts, a faculty of intuition by which one ‘sees’ truths or abstract things (‘essences’ or universals, etc.), and a faculty of reasoning, i.e. passing from premises to a conclusion (discursive reason). The verb ‘reason is confined to this latter sense, which is now anyway the commonest for the noun too

- ^ Rescher, Nicholas (2005). The Oxford companion to philosophy. Ted Honderich (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 791. ISBN 978-0-19-153265-8. OCLC 62563098.

reason. The general human ‘faculty’ or capacity for truth-seeking and problem solving

- ^ Mercier, Hugo; Sperber, Dan (2017). The Enigma of Reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780674368309. OCLC 959650235.

Enhanced with reason, cognition can secure better knowledge in all domains and adjust action to novel and ambitious goals, or so the story goes. […] Understanding why only a few species have echolocation is easy. Understanding why only humans have reason is much more challenging.

Compare: MacIntyre, Alasdair (1999). Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues. The Paul Carus Lectures. Vol. 20. Open Court Publishing. ISBN 9780812693973. OCLC 40632451. Retrieved 2014-12-01.[…] the exercise of independent practical reasoning is one essential constituent to full human flourishing. It is not—as I have already insisted—that one cannot flourish at all, if unable to reason. Nonetheless not to be able to reason soundly at the level of practice is a grave disability.

- ^ See, for example:

- Amoretti, Maria Cristina; Vassallo, Nicla, eds. (2013). Reason and Rationality. Philosophische Analyse / Philosophical Analysis. Vol. 48. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110325867. ISBN 9783868381634. OCLC 807032616.

- Audi, Robert (2001). The Architecture of Reason: The Structure and Substance of Rationality. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195158427.001.0001. ISBN 0195141121. OCLC 44046914.

- Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi (2008). On Reason: Rationality in a World of Cultural Conflict and Racism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822388777. ISBN 9780822341789. OCLC 180989486.

- Rescher, Nicholas (1988). Rationality: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Nature and the Rationale of Reason. Clarendon Library of Logic and Philosophy. Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198244355. OCLC 17954516.

- ^ Hintikka, J. «Philosophy of logic». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ «The Internet Classics Archive – Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle, Book VI, Translated by W. D. Ross». classics.mit.edu. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ Michel Foucault, «What is Enlightenment?» in The Essential Foucault, eds. Paul Rabinow and Nikolas Rose, New York: The New Press, 2003, 43–57. See also Nikolas Kompridis, «The Idea of a New Beginning: A Romantic Source of Normativity and Freedom,» in Philosophical Romanticism, New York: Routledge, 2006, 32–59; «So We Need Something Else for Reason to Mean», International Journal of Philosophical Studies 8: 3, 271–295.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster.com Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of reason

- ^ Rachels, James. The Elements of Moral Philosophy, 4th ed. McGraw Hill, 2002

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert, «logos», A Greek–English Lexicon. For etymology of English «logic» see any dictionary such as the Merriam Webster entry for logic.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton; Short, Charles, «ratio», A Latin Dictionary

- ^ See Merriam Webster «rational» and Merriam Webster «reasonable».

- ^ a b Habermas, Jürgen (1990). The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ Kirk; Raven; Schofield (1983), The Presocratic Philosophers (second ed.), Cambridge University Press. See pp. 204 & 235.

- ^ Nicomachean Ethics Book 1.

- ^ a b Davidson, Herbert (1992), Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, on Intellect, Oxford University Press, p. 3.

- ^ Moore, Edward, «Plotinus», Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ «Plato», Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ «Catholic Culture», Hellenism

- ^ «Reason», Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ «Natural Law», Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ «Religion and Science», Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2021

- ^ Dreyfus, Hubert. «Telepistemology: Descartes’ Last Stand». socrates.berkeley.edu. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ Descartes, «Second Meditation».

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas (1839), Molesworth (ed.), De Corpore, London, J. Bohn: «We must not therefore think that computation, that is, ratiocination, has place only in numbers, as if man were distinguished from other living creatures (which is said to have been the opinion of Pythagoras) by nothing but the faculty of numbering; for magnitude, body, motion, time, degrees of quality, action, conception, proportion, speech and names (in which all the kinds of philosophy consist) are capable of addition and substraction [sic]. Now such things as we add or substract, that is, which we put into an account, we are said to consider, in Greek λογίζεσθαι [logizesthai], in which language also συλλογίζεσθι [syllogizesthai] signifies to compute, reason, or reckon.»

- ^ Hobbes, Thomas, «VII. Of the ends, or resolutions of discourse», The English Works of Thomas Hobbes, vol. 3 (Leviathan) and Hobbes, Thomas, «IX. Of the several subjects of knowledge», The English Works of Thomas Hobbes, vol. 3 (Leviathan)

- ^ Locke, John (1824) [1689], «XXVII On Identity and Diversity», An Essay concerning Human Understanding Part 1, The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes (12th ed.), Rivington

- ^ Hume, David, «I.IV.VI. Of Personal Identity», A Treatise of Human Nature

- ^ Hume, David, «II.III.III. Of the influencing motives of the will.», A Treatise of Human Nature

- ^ Hume, David, «I.III.VII (footnote) Of the Nature of the Idea Or Belief», A Treatise of Human Nature

- ^ Hume, David, «I.III.XVI. Of the reason of animals», A Treatise of Human Nature

- ^ Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason; Critique of Practical Reason.

- ^ Michael Sandel, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel; translated by James W. Ellington [1785] (1993). Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals 3rd ed. Hackett. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-87220-166-8.

- ^ See Velkley, Richard (2002), «On Kant’s Socratism», Being After Rousseau, University of Chicago Press and Kant’s own first preface to The Critique of Pure Reason.

- ^ Jürgen Habermas, Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995.

- ^ Jürgen Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, translated by Thomas McCarthy. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

- ^ Nikolas Kompridis, Critique and Disclosure: Critical Theory between Past and Future, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006. See also Nikolas Kompridis, «So We Need Something Else for Reason to Mean», International Journal of Philosophical Studies 8:3, 271–295.

- ^ Charles Taylor, Philosophical Arguments (Harvard University Press, 1997), 12; 15.

- ^ Michel Foucault, «What is Enlightenment?», The Essential Foucault, New York: The New Press, 2003, 43–57.

- ^ Gensler, Harry J. (2010). Introduction to Logic (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 1. doi:10.4324/9780203855003. ISBN 9780415996501. OCLC 432990013.

- ^ Gächter, Simon (2013). «Rationality, social preferences, and strategic decision-making from a behavioral economics perspective». In Wittek, Rafael; Snijders, T. A. B.; Nee, Victor (eds.). The Handbook of Rational Choice Social Research. Stanford, CA: Stanford Social Sciences, an imprint of Stanford University Press. pp. 33–71 (33). doi:10.1515/9780804785501-004. ISBN 9780804784184. OCLC 807769289. S2CID 242795845.

The central assumption of the rational choice approach is that decision-makers have logically consistent goals (whatever they are), and, given these goals, choose the best available option.

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1999) [1979]. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (20th anniversary ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0394756827. OCLC 40724766.

- ^ Bickhard, Mark H.; Campbell, Robert L. (July 1996). «Developmental aspects of expertise: rationality and generalization». Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence. 8 (3–4): 399–417. doi:10.1080/095281396147393.

- ^ a b c Moshman, David (May 2004). «From inference to reasoning: the construction of rationality». Thinking & Reasoning. 10 (2): 221–239. doi:10.1080/13546780442000024. S2CID 43330718.

- ^ Ricco, Robert B. (2015). «The development of reasoning». In Lerner, Richard M. (ed.). Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. Vol. 2. Cognitive Processes (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 519–570 (534). doi:10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy213. ISBN 9781118136850. OCLC 888024689.

Moshman’s (1990, 1998, 2004, 2013a) theory of the development of deductive reasoning considers changes in metacognition to be the essential story behind the development of deductive (and inductive) reasoning. In his view, reasoning involves explicit conceptual knowledge regarding inference (metalogical knowledge) and metacognitive awareness of, and control over, inference.

- ^ Aristotle, Complete Works (2 volumes), Princeton, 1995, ISBN 0-691-09950-2

- ^ Smith, Robin (2020), «Aristotle’s Logic», in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2022-06-08

- ^ See this Perseus search, and compare English translations. and see LSJ dictionary entry for λογικός, section II.2.b.

- ^ See the Treatise of Human Nature of David Hume, Book I, Part III, Sect. XVI.

- ^ Locke, John (1824) [1689], «XVII Of Reason», An Essay concerning Human Understanding Part 2 and Other Writings, The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes, vol. 2 (12th ed.), Rivington

- ^ Terrence Deacon, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain, W.W. Norton & Company, 1998, ISBN 0-393-31754-4

- ^ Leviathan Chapter IV Archived 2006-06-15 at the Wayback Machine: «The Greeks have but one word, logos, for both speech and reason; not that they thought there was no speech without reason, but no reasoning without speech»

- ^ Posterior Analytics II.19.

- ^ See for example Ruth M.J. Byrne (2005). The Rational Imagination: How People Create Counterfactual Alternatives to Reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ De Anima III.i–iii; On Memory and Recollection, On Dreams

- ^ Mimesis in modern academic writing, starting with Erich Auerbach, is a technical word, which is not necessarily exactly the same in meaning as the original Greek. See Mimesis.

- ^ Origins of the Modern Mind p. 172

- ^ Jacob Klein A Commentary on the Meno Ch.5

- ^ Jacob Klein A Commentary on the Meno p. 122

- ^ Origins of the Modern Mind p. 169

- ^ «Introduction» to the translation of Poetics by Davis and Seth Benardete p. xvii, xxviii

- ^ Davis is here using «poetic» in an unusual sense, questioning the contrast in Aristotle between action (praxis, the praktikē) and making (poēsis, the poētikē): «Human [peculiarly human] action is imitation of action because thinking is always rethinking. Aristotle can define human beings as at once rational animals, political animals, and imitative animals because in the end the three are the same.»

- ^ Aristotle On Memory 450a 15–16.

- ^ Jacob Klein A Commentary on the Meno p. 109

- ^ Aristotle Hist. Anim. I.1.488b.25–26.

- ^ Jacob Klein A Commentary on the Meno p. 112

- ^ The Origins of the Modern Mind p. 173 see also A Mind So Rare pp. 140–141

- ^ Jeffrey, Richard. 1991. Formal logic: its scope and limits, (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill:1.

- ^ Walton, Douglas N. (2014). «Argumentation schemes for argument from analogy». In Ribeiro, Henrique Jales (ed.). Systematic approaches to argument by analogy. Argumentation library. Vol. 25. Cham; New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 23–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-06334-8_2. ISBN 978-3-319-06333-1. OCLC 884441074.

- ^ Vickers, John (2009). «The Problem of Induction». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Example: Aristotle Metaphysics 981b: τὴν ὀνομαζομένην σοφίαν περὶ τὰ πρῶτα αἴτια καὶ τὰς ἀρχὰς ὑπολαμβάνουσι πάντες: ὥστε, καθάπερ εἴρηται πρότερον, ὁ μὲν ἔμπειρος τῶν ὁποιανοῦν ἐχόντων αἴσθησιν εἶναι δοκεῖ σοφώτερος, ὁ δὲ τεχνίτης τῶν ἐμπείρων, χειροτέχνου δὲ ἀρχιτέκτων, αἱ δὲ θεωρητικαὶ τῶν ποιητικῶν μᾶλλον. English: «…what is called Wisdom is concerned with the primary causes and principles, so that, as has been already stated, the man of experience is held to be wiser than the mere possessors of any power of sensation, the artist than the man of experience, the master craftsman than the artisan; and the speculative sciences to be more learned than the productive.»

- ^ Metaphysics 1009b ποῖα οὖν τούτων ἀληθῆ ἢ ψευδῆ, ἄδηλον: οὐθὲν γὰρ μᾶλλον τάδε ἢ τάδε ἀληθῆ, ἀλλ᾽ ὁμοίως. διὸ Δημόκριτός γέ φησιν ἤτοι οὐθὲν εἶναι ἀληθὲς ἢ ἡμῖν γ᾽ ἄδηλον. English «Thus it is uncertain which of these impressions are true or false; for one kind is no more true than another, but equally so. And hence Democritus says that either there is no truth or we cannot discover it.»

- ^ For example Aristotle Metaphysics 983a: ἐπεὶ δὲ φανερὸν ὅτι τῶν ἐξ ἀρχῆς αἰτίων δεῖ λαβεῖν ἐπιστήμην (τότε γὰρ εἰδέναι φαμὲν ἕκαστον, ὅταν τὴν πρώτην αἰτίαν οἰώμεθα γνωρίζειν) English «It is clear that we must obtain knowledge of the primary causes, because it is when we think that we understand its primary cause that we claim to know each particular thing.»

- ^ Example: Nicomachean Ethics 1139b: ἀμφοτέρων δὴ τῶν νοητικῶν μορίων ἀλήθεια τὸ ἔργον. καθ᾽ ἃς οὖν μάλιστα ἕξεις ἀληθεύσει ἑκάτερον, αὗται ἀρεταὶ ἀμφοῖν. English The attainment of truth is then the function of both the intellectual parts of the soul. Therefore their respective virtues are those dispositions that will best qualify them to attain truth.

- ^ Example: Plato Republic 490b: μιγεὶς τῷ ὄντι ὄντως, γεννήσας νοῦν καὶ ἀλήθειαν, γνοίη English: «Consorting with reality really, he would beget intelligence and truth, attain to knowledge»

- ^ «This quest for the beginnings proceeds through sense perception, reasoning, and what they call noesis, which is literally translated by «understanding» or intellect,» and which we can perhaps translate a little bit more cautiously by «awareness,» an awareness of the mind’s eye as distinguished from sensible awareness.» «Progress or Return» in An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss. (Expanded version of Political Philosophy: Six Essays by Leo Strauss, 1975.) Ed. Hilail Gilden. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1989.

- ^ However, the empiricism of Aristotle must certainly be doubted. For example in Metaphysics 1009b, cited above, he criticizes people who think knowledge might not be possible because, «They say that the impression given through sense-perception is necessarily true; for it is on these grounds that both Empedocles and Democritus and practically all the rest have become obsessed by such opinions as these.»

- ^ G.W.F. Hegel The Philosophy of History, p. 9, Dover Publications Inc., ISBN 0-486-20112-0; 1st ed. 1899

- ^ a b Sharples, R. W. (2005). The Oxford companion to philosophy. Ted Honderich (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 896. ISBN 978-0-19-153265-8. OCLC 62563098.

Moral virtue is the only good an wickedness the only evil…Emotions are interpreted in intellectual terms; those such as distress, pity (which is a species of distress), and fear which reflect false judgements about what is evil, are to be avoided (as also are those which reflect false judgement about what is good, such as love of honours or riches)…They did however allow the wise man such ‘good feelings’ as ‘watchfulness’ or kindness the difference being that these are based on sound (Stoic) reasoning concerning what matters and what does not.

- ^ a b Rufus, Musonius (2000). Concise Routledge encyclopedia of philosophy. Routledge. London: Routledge. p. 863. ISBN 0-203-16994-8. OCLC 49569365.

Vice is founded on ‘passions’: these are at root false value judgements, in which we lose rational control by overvaluing things which are in fact indifferent. Virtue, a set of sciences governing moral choice, is the one thing of intrinsic worth and therefore genuinely ‘good’.

- ^ Baltzly, Dirk (2019), «Stoicism», in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2021-03-27

- ^ Radford, Benjamin; Frazier, Kendrick (January 2017). «The Edge of Reason: A Rational Skeptic in an Irrational World». Skeptical Inquirer. 41 (1): 60.

- ^ Velkley, Richard (2002), «Speech. Imagination, Origins: Rousseau and the Political Animal», Being after Rousseau: Philosophy and Culture in Question, University of Chicago Press

- ^ Rousseau (1997), «Preface», in Gourevitch (ed.), Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality Among Men or Second Discourse, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Velkley, Richard (2002), «Freedom, Teleology, and Justification of Reason», Being after Rousseau: Philosophy and Culture in Question, University of Chicago Press

- ^ Plattner, Marc (1997), «Rousseau and the Origins of Nationalism», The Legacy of Rousseau, University of Chicago Press

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2008). The God Delusion (Reprint ed.). Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-618-91824-9.

Scientists… see the fight for evolution as only one battle in a larger war: a looming war between supernaturalism on the one side and rationality on the other.

- ^ Strauss, Leo, «Progress or Return», An Introduction to Political Philosophy

- ^ Locke, John (1824) [1689], «XVIII Of Faith and Reason, and their distinct Provinces.», An Essay concerning Human Understanding Part 2 and Other Writings, The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes, vol. 2 (12th ed.), Rivington

- ^ Plantinga, Alvin (2011). Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-981209-7.

- ^ Natural Signs and Knowledge of God: A New Look at Theistic Arguments (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-966107-7.

- ^ Stephen Jay Gould (1997). «Nonoverlapping Magisteria». www.stephenjaygould.org. Retrieved 2016-04-06.