Where did the word restaurant originated from?

The word derives from the French verb “restaurer” (“to restore”, “to revive”) and, being the present participle of the verb, it literally means “that which restores”.

Which country is the word restaurant borrowed?

Etymology. Borrowed from French restaurant, present participle of the verb restaurer, corresponding to Latin restaurans, restaurantis, present participle of restauro (“I restore”), from the name of the ‘restorative’ soup served in the first establishments.

What language does restaurant come from?

Restaurant used in many languages today actually comes from the French verb restaurer, meaning “to restore or refresh.”

What were the first restaurants?

The first restaurant proprietor is believed to have been one A. Boulanger, a soup vendor, who opened his business in Paris in 1765. The sign above his door advertised restoratives, or restaurants, referring to the soups and broths available within.

What was the first restaurant in the USA?

The White Horse Tavern

What is the oldest continuously operating restaurant in the United States?

White Horse Tavern

Who is the world’s oldest man?

The oldest verified man ever is Jiroemon Kimura (1897–2013) of Japan, who lived to the age of 116 years, 54 days. The oldest known living person is Kane Tanaka of Japan, aged 118 years, 172 days. The oldest known living man is Saturnino de la Fuente García, of Spain, aged 112 years, 135 days.

What is the oldest known hymn?

Hurrian Hymn No. 6

What is the most beautiful hymn?

11 Of The Most Beautiful Hymns Covered On YouTube

- It Is Well With My Soul – 3b4hJoy.

- Come Thou Fount Of Every Blessing – Phil Wickham.

- Nothing But The Blood Of Jesus – Andy Cherry.

- There is a Fountain – MercyMe.

- Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior – Hasan Green.

- His Eye Is On The Sparrow – Lee and Sig Evangelista.

What is the number 1 song in the world?

As of the issue for the week ending on June 26, 2021, the Billboard Hot 100 has had 1,125 different number one entries. The chart’s current number-one song is “Butter” by BTS.

What is the shortest song in the world 2019?

I Suffer More

What is the longest song in history?

Answer: As of 2019, Guinness World Records states that the longest officially released song was “The Rise and Fall of Bossanova,” by PC III, which lasts 13 hours, 23 minutes, and 32 seconds. The longest recorded pop song is “Apparente Libertà,” by Giancarlo Ferrari, which is 76 minutes, 44 seconds long.

What’s the shortest song ever written?

You Suffer

What song has been in the top 100 longest?

Someone You Loved

What is the fastest song?

“Thousand” was listed in Guinness World Records for having the fastest tempo in beats-per-minute (BPM) of any released single, peaking at approximately 1,015 BPM.

Are songs getting shorter?

Over the last five years, it seems that new songs have gotten shorter and shorter. But you’re not imagining this; a recent report from Quartz finds a change in the average length of pop songs. From 2013 to 2018, the average song on the Billboard Hot 100 went from 3 minutes and 50 seconds to 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

A restaurant is a business that prepares and serves food and drinks to customers.[1] Meals are generally served and eaten on the premises, but many restaurants also offer take-out and food delivery services. Restaurants vary greatly in appearance and offerings, including a wide variety of cuisines and service models ranging from inexpensive fast-food restaurants and cafeterias to mid-priced family restaurants, to high-priced luxury establishments.

Etymology[edit]

The word derives from the early 19th century, taken from the French word restaurer ‘provide food for’, literally ‘restore to a former state’[2] and, being the present participle of the verb,[3] The term restaurant may have been used in 1507 as a «restorative beverage», and in correspondence in 1521 to mean ‘that which restores the strength, a fortifying food or remedy’.[4]

History[edit]

Service counter of a thermopolium in Pompeii

A public eating establishment similar to a restaurant is mentioned in a 512 BC record from Ancient Egypt. It served only one dish, a plate of cereal, wild fowl, and onions.[5]

A forerunner of the modern restaurant is the thermopolium, an establishment in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome that sold and served ready-to-eat food and beverages. These establishments were somewhat similar in function to modern fast food restaurants. They were most often frequented by people who lacked private kitchens. In the Roman Empire they were popular among residents of insulae.[6]

In Pompeii, 158 thermopolia with service counters have been identified throughout the town. They were concentrated along the main axis of the town and the public spaces where they were frequented by the locals.[7]

The Romans also had the popina, a wine bar which in addition to a variety of wines offered a limited selection of simple foods such as olives, bread, cheese, stews, sausage, and porridge. The popinae were known as places for the plebeians of the lower classes of Roman society to socialize. While some were confined to one standing room only, others had tables and stools and a few even had couches.[8][9]

Another early forerunner of the restaurant was the inn. Throughout the ancient world, inns were set up alongside roads to cater to people travelling between cities, offering lodging and food. Meals were typically served at a common table to guests. However, there were no menus or options to choose from.[10]

The Arthashastra references establishments where prepared food was sold in ancient India. One regulation states that «those who trade in cooked rice, liquor, and flesh» are to live in the south of the city. Another states that superintendents of storehouses may give surpluses of bran and flour to «those who prepare cooked rice, and rice-cakes», while a regulation involving city superintendents references «sellers of cooked flesh and cooked rice».[11]

Early eating establishments recognizable as restaurants in the modern sense emerged in Song dynasty China during the 11th and 12th centuries. In large cities, such as Kaifeng and Hangzhou, food catering establishments catered to merchants who travelled between cities. Probably growing out of tea houses and taverns which catered to travellers, Kaifeng’s restaurants blossomed into an industry that catered to locals as well as people from other regions of China. As travelling merchants were not used to the local cuisine of other cities, these establishments were set up to serve dishes familiar to merchants from other parts of China. Such establishments were located in the entertainment districts of major cities, alongside hotels, bars, and brothels. The larger and more opulent of these establishments offered a dining experience similar to modern restaurant culture. According to a Chinese manuscript from 1126, patrons of one such establishment were greeted with a selection of pre-plated demonstration dishes which represented food options. Customers had their orders taken by a team of waiters who would then sing their orders to the kitchen and distribute the dishes in the exact order in which they had been ordered.[12][13]

There is a direct correlation between the growth of the restaurant businesses and institutions of theatrical stage drama, gambling and prostitution which served the burgeoning merchant middle class during the Song dynasty.[14] Restaurants catered to different styles of cuisine, price brackets, and religious requirements. Even within a single restaurant choices were available, and people ordered the entrée from written menus.[13] An account from 1275 writes of Hangzhou, the capital city for the last half of the dynasty:

The people of Hangzhou are very difficult to please. Hundreds of orders are given on all sides: this person wants something hot, another something cold, a third something tepid, a fourth something chilled. one wants cooked food, another raw, another chooses roast, another grill.[15]

The restaurants in Hangzhou also catered to many northern Chinese who had fled south from Kaifeng during the Jurchen invasion of the 1120s, while it is also known that many restaurants were run by families formerly from Kaifeng.[16]

In Japan, a restaurant culture emerged in the 16th century out of local tea houses. Tea house owner Sen no Rikyū created the kaiseki multi-course meal tradition, and his grandsons expanded the tradition to include speciality dishes and cutlery which matched the aesthetic of the food.[12]

In Europe, inns which offered food and lodgings and taverns where food was served alongside alcoholic beverages were common into the Middle Ages and Renaissance. They typically served common fare of the type normally available to peasants. In Spain, such establishments were called bodegas and served tapas. In England, they typically served foods such as sausage and shepherd’s pie.[10] Cookshops were also common in European cities during the Middle Ages. These were establishments which served dishes such as pies, puddings, sauces, fish, and baked meats. Customers could either buy a ready-made meal or bring their own meat to be cooked. As only large private homes had the means for cooking, the inhabitants of European cities were significantly reliant on them.[17]

France in particular has a rich history with the development of various forms of inns and eateries, eventually to form many of the now-ubiquitous elements of the modern restaurant. As far back as the thirteenth century, French inns served a variety of food — bread, cheese, bacon, roasts, soups, and stews — usually eaten at a common table. Parisians could buy what was essentially take-out food from rôtisseurs, who prepared roasted meat dishes, and pastry-cooks, who could prepare meat pies and often more elaborate dishes. Municipal statutes stated that the official prices per item were to be posted at the entrance; this was the first official mention of menus.[18]

Taverns also served food, as did cabarets. A cabaret, however, unlike a tavern, served food at tables with tablecloths, provided drinks with the meal, and charged by the customers’ choice of dish, rather than by the pot.[19] Cabarets were reputed to serve better food than taverns and a few, such as the Petit Maure, became well known. A few cabarets had musicians or singing, but most, until the late 19th century, were simply convivial eating places.[18][19] The first café opened in Paris in 1672 at the Saint-Germain fair. By 1723 there were nearly four hundred cafés in Paris, but their menu was limited to simpler dishes or confectionaries, such as coffee, tea, chocolate (the drink; chocolate in solid state was invented only in the 19th century), ice creams, pastries, and liqueurs.[19]

At the end of the 16th century, the guild of cook-caterers (later known as «traiteurs») was given its own legal status. The traiteurs dominated sophisticated food service, delivering or preparing meals for the wealthy at their residences. Taverns and cabarets were limited to serving little more than roast or grilled meats. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, both inns and then traiteurs began to offer «host’s tables» (tables d’hôte), where one paid a set price to sit at a large table with other guests and eat a fixed menu meal.[18]

Modern format[edit]

The earliest modern-format «restaurants» to use that word in Paris were the establishments which served bouillon, a broth made of meat and egg which was said to restore health and vigour. The first restaurant of this kind was opened in 1765 or 1766 by Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau on rue des Poulies, now part of the Rue de Louvre.[20] The name of the owner is sometimes given as Boulanger.[21] Unlike earlier eating places, it was elegantly decorated, and besides meat broth offered a menu of several other «restorative» dishes, including macaroni. Chantoiseau and other chefs took the title «traiteurs-restaurateurs».[21] While not the first establishment where one could order food, or even soups, it is thought to be the first to offer a menu of available choices.[22]

In the Western world, the concept of a restaurant as a public venue where waiting staff serve patrons food from a fixed menu is a relatively recent one, dating from the late 18th century.[23] Modern restaurant culture originated in France during the 1780s.

In June 1786, the Provost of Paris issued a decree giving the new kind of eating establishment official status, authorising restaurateurs to receive clients and to offer them meals until eleven in the evening in winter and midnight in summer.[21] Ambitious cooks from noble households began to open more elaborate eating places. The first luxury restaurant in Paris, the La Grande Taverne de Londres, was opened at the Palais-Royal at the beginning of 1786 by Antoine Beauvilliers, the former chef of the Count of Provence. It had mahogany tables, linen tablecloths, chandeliers, well-dressed and trained waiters, a long wine list and an extensive menu of elaborately prepared and presented dishes.[21] Dishes on its menu included partridge with cabbage, veal chops grilled in buttered paper, and duck with turnips.[24] This is considered to have been the «first real restaurant».[25][22] According to Brillat-Savarin, the restaurant was «the first to combine the four essentials of an elegant room, smart waiters, a choice cellar, and superior cooking».[26][27][28]

The aftermath of the French Revolution saw the number of restaurants skyrocket. Due to the mass emigration of nobles from the country, many cooks from aristocratic households who were left unemployed went on to found new restaurants.[29][10] One restaurant was started in 1791 by Méot, the former chef of the Duke of Orleans, which offered a wine list with twenty-two choices of red wine and twenty-seven of white wine. By the end of the century there were a collection of luxury restaurants at the Grand-Palais: Huré, the Couvert espagnol; Février; the Grotte flamande; Véry, Masse and the Café de Chartres (still open, now Le Grand Véfour)[21]

In 1802 the term was applied to an establishment where restorative foods, such as bouillon, a meat broth, were served («établissement de restaurateur»).[30] The closure of culinary guilds and societal changes resulting from the industrial revolution contributed significantly to the increased prevalence of restaurants in Europe.[31]

Types[edit]

Restaurants are classified or distinguished in many different ways. The primary factors are usually the food itself (e.g. vegetarian, seafood, steak); the cuisine (e.g. Italian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, French, Mexican, Thai) or the style of offering (e.g. tapas bar, a sushi train, a tastet restaurant, a buffet restaurant or a yum cha restaurant). Beyond this, restaurants may differentiate themselves on factors including speed (see fast food), formality, location, cost, service, or novelty themes (such as automated restaurants). Some of these also include fine dining, casual dining, contemporary casual, family style, fast casual, fast food, cafes, buffet, concession stands, food trucks, pop-up restaurants, diners, and ghost restaurants.

Restaurant Basilica at the shoreline of Kellosaarenranta by night in Ruoholahti, Helsinki, Finland

Restaurants range from inexpensive and informal lunching or dining places catering to people working nearby, with modest food served in simple settings at low prices, to expensive establishments serving refined food and fine wines in a formal setting. In the former case, customers usually wear casual clothing. In the latter case, depending on culture and local traditions, customers might wear semi-casual, semi-formal or formal wear. Typically, at mid- to high-priced restaurants, customers sit at tables, their orders are taken by a waiter, who brings the food when it is ready. After eating, the customers then pay the bill. In some restaurants, such as those in workplaces, there are usually no waiters; the customers use trays, on which they place cold items that they select from a refrigerated container and hot items which they request from cooks, and then they pay a cashier before they sit down. Another restaurant approach which uses few waiters is the buffet restaurant. Customers serve food onto their own plates and then pay at the end of the meal. Buffet restaurants typically still have waiters to serve drinks and alcoholic beverages. Fast food establishments are also considered to be restaurants. In addition, food trucks are another popular option for people who want quick food service.

Tourists around the world can enjoy dining services on railway dining cars and cruise ship dining rooms, which are essentially travelling restaurants. Many railway dining services also cater to the needs of travellers by providing railway refreshment rooms at railway stations. Many cruise ships provide a variety of dining experiences including a main restaurant, satellite restaurants, room service, speciality restaurants, cafes, bars and buffets to name a few. Some restaurants on these cruise ships require table reservations and operate specific dress codes.[33]

Restaurant staff[edit]

A restaurant’s proprietor is called a restaurateur, this derives from the French verb restaurer, meaning «to restore». Professional cooks are called chefs, with there being various finer distinctions (e.g. sous-chef, chef de partie). Most restaurants (other than fast food restaurants and cafeterias) will have various waiting staff to serve food, beverages and alcoholic drinks, including busboys who remove used dishes and cutlery. In finer restaurants, this may include a host or hostess, a maître d’hôtel to welcome customers and to seat them, and a sommelier or wine waiter to help patrons select wines. A new route to becoming a restaurateur, rather than working one’s way up through the stages, is to operate a food truck. Once a sufficient following has been obtained, a permanent restaurant site can be opened. This trend has become common in the UK and the US.

Chef’s table[edit]

«Chef’s table» redirects here. For the Netflix documentary series, see Chef’s Table.

A chef’s table is a table located in the kitchen of a restaurant,[34][35] reserved for VIPs and special guests.[36] Patrons may be served a themed[36] tasting menu prepared and served by the head chef. Restaurants can require a minimum party[37] and charge a higher flat fee.[38] Because of the demand on the kitchen’s facilities, chef’s tables are generally only available during off-peak times.[39]

By country[edit]

Europe[edit]

France[edit]

France has a long tradition with public eateries and modern restaurant culture emerged there. In the early 19th century, traiteurs and restaurateurs became known simply as «restaurateurs». The use of the term «restaurant» for the establishment itself only became common in the 19th century.

According to the legend, the first mention to a restaurant dates back to 1765 in Paris. It was located on Rue des Poulies, now Rue du Louvre, and use to serve dishes known as «restaurants».[40] The place was run by a man named Mr. Boulanger.[41] However, according to the Larousse Gastronomique, La Grande Taverne de Londres which opened in 1782 is considered as the first Parisian restaurant.[42]

The first restaurant guide, called Almanach des Gourmands, written by Grimod de La Reyniére, was published in 1804. During the French Restoration period, the most celebrated restaurant was the Rocher de Cancale, frequented by the characters of Balzac. In the middle of the century, Balzac’s characters moved to the Café Anglais, which in 1867 also hosted the famous Three Emperors Dinner hosted by Napoleon III in honor of Tsar Alexander II, Kaiser Wilhelm I and Otto von Bismarck during the Exposition Universelle in 1867[43]

Other restaurants that occupy a place in French history and literature include Maxim’s and Fouquet’s. The restaurant of Hotel Ritz Paris, opened in 1898, was made famous by its chef, Auguste Escoffier. The 19th century also saw the appearance of new kinds of more modest restaurants, including the bistrot. The brasserie featured beer and was made popular during the 1867 Paris Exposition.[21]

North America[edit]

United States[edit]

In the United States, it was not until the late 18th century that establishments that provided meals without also providing lodging began to appear in major metropolitan areas in the form of coffee and oyster houses. The actual term «restaurant» did not enter into the common parlance until the following century. Prior to being referred to as «restaurants» these eating establishments assumed regional names such as «eating house» in New York City, «restorator» in Boston, or «victualling house» in other areas. Restaurants were typically located in populous urban areas during the 19th century and grew both in number and sophistication in the mid-century due to a more affluent middle class and to urbanization. The highest concentration of these restaurants were in the West, followed by industrial cities on the Eastern Seaboard.

When Prohibition went into effect in 1920, restaurants offering fine dining had a hard time making ends meet because they had depended on profits from selling wine and alcoholic beverages. Replacing them were establishments offering simpler, more casual experiences such as cafeterias, roadside restaurants, and diners. When Prohibition ended in the 1930s, luxury restaurants slowly started to appear again as the economy recovered from the Great Depression.[45]

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation based on race, color, religion, or national origin in all public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce, including restaurants. Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964), was a decision of the US Supreme Court which held that Congress acted within its power under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution in forbidding racial discrimination in restaurants as this was a burden to interstate commerce.[46][47]

In the 1970s, there was one restaurant for every 7,500 persons. In 2016, there were 1,000,000 restaurants; one for every 310 people. The average person eats out five to six times weekly. 3.3% of the nation’s workforce is composed of restaurant workers.[48] According to a Gallup Poll in 2016, nearly 61% of Americans across the country eat out at a restaurant once a week or more, and this percent is only predicted to increase in future years.[49] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, The National Restaurant Association estimated restaurant sales of $899 billion in 2020. The association now projects that the pandemic will decrease that to $675 billion, a decline of $274 billion over their previous estimate.[50]

South America[edit]

Brazil[edit]

In Brazil, restaurant varieties mirror the multitude of nationalities that arrived in the country: Japanese, Arab, German, Italian, Portuguese and many more.

Colombia[edit]

The word piquete can be used to refer to a common Colombian type of meal that includes meat, yuca and potatoes, which is a type of meal served at a piqueteaderos. The verb form of the word piquete, piquetear, means to participate in binging, liquor drinking, and leisure activities in popular areas or open spaces.[51]

Peru[edit]

In Peru, many indigenous, Spanish, and Chinese dishes are frequently found. Because of recent immigration from places such as China, and Japan, there are many Chinese and Japanese restaurants around the country, especially in the capital city of Lima.

Guides[edit]

Restaurant guides review restaurants, often ranking them or providing information to guide consumers (type of food, handicap accessibility, facilities, etc.). One of the most famous contemporary guides is the Michelin series of guides which accord from 1 to 3 stars to restaurants they perceive to be of high culinary merit. Restaurants with stars in the Michelin guide are formal, expensive establishments; in general the more stars awarded, the higher the prices.

The main competitor to the Michelin guide in Europe is the guidebook series published by Gault Millau. Its ratings are on a scale of 1 to 20, with 20 being the highest.

In the United States, the Forbes Travel Guide (previously the Mobil travel guides) and the AAA rate restaurants on a similar 1 to 5 star (Forbes) or diamond (AAA) scale. Three, four, and five star/diamond ratings are roughly equivalent to the Michelin one, two, and three star ratings while one and two star ratings typically indicate more casual places to eat. In 2005, Michelin released a New York City guide, its first for the United States. The popular Zagat Survey compiles individuals’ comments about restaurants but does not pass an «official» critical assessment.

Nearly all major American newspapers employ food critics and publish online dining guides for the cities they serve. Some news sources provide customary reviews of restaurants, while others may provide more of a general listings service.

More recently Internet sites have started up that publish both food critic reviews and popular reviews by the general public.

Economics[edit]

Canada[edit]

There are 86,915 commercial food service units in Canada, or 26.4 units per 10,000 Canadians. By segment, there are:[52]

- 38,797 full-service restaurants

- 34,629 limited-service restaurants

- 741 contract and social caterers

- 6,749 drinking places

Fully 63% of restaurants in Canada are independent brands. Chain restaurants account for the remaining 37%, and many of these are locally owned and operated franchises.[53]

European Union[edit]

The EU-27 has an estimated 1.6m businesses involved in ‘accommodation & food services’, more than 75% of which are small and medium enterprises.[54]

India[edit]

The Indian restaurant industry is highly fragmented with more than 1.5 million outlets of which only around 3000 of them are from the organised segment.[55] The organised segment includes quick service restaurants; casual dining; cafes; fine dining; and pubs, bars, clubs, and lounges.

United States[edit]

As of 2006, there are approximately 215,000 full-service restaurants in the United States, accounting for $298 billion in sales, and approximately 250,000 limited-service (fast food) restaurants, accounting for $260 billion.[56] Starting in 2016, Americans spent more on restaurants than groceries.[57]

In October 2017, The New York Times reported there are 620,000 eating and drinking places in the United States, according to the Bureau of Labour Statistics. They also reported that the number of restaurants are growing almost twice as fast as the population.[58]

One study of new restaurants in Cleveland, Ohio found that 1 in 4 changed ownership or went out of business after one year, and 6 out of 10 did so after three years. (Not all changes in ownership are indicative of financial failure.)[59] The three-year failure rate for franchises was nearly the same.[60]

Restaurants employed 912,100 cooks in 2013, earning an average $9.83 per hour.[61] The waiting staff numbered 4,438,100 in 2012, earning an average $8.84 per hour.[62]

Jiaxi Lu of the Washington Post reports in 2014 that, «Americans are spending $683.4 billion a year dining out, and they are also demanding better food quality and greater variety from restaurants to make sure their money is well spent.»[63]

Dining in restaurants has become increasingly popular, with the proportion of meals consumed outside the home in restaurants or institutions rising from 25% in 1950 to 46% in 1990. This is caused by factors such as the growing numbers of older people, who are often unable or unwilling to cook their meals at home and the growing number of single-parent households. It is also caused by the convenience that restaurants can afford people; the growth of restaurant popularity is also correlated with the growing length of the work day in the US, as well as the growing number of single parent households.[64] Eating in restaurants has also become more popular with the growth of higher income households. At the same time, less expensive establishments such as fast food establishments can be quite inexpensive, making restaurant eating accessible to many.

Employment[edit]

The restaurant industry in the United States is large and quickly growing, with 10 million workers. 1 in every 12 U.S. residents work in the business, and during the 2008 recession, the industry was an anomaly in that it continued to grow. Restaurants are known for having low wages, which they claim are due to thin profit margins of 4-5%. For comparison, however, Walmart has a 1% profit margin.[65]

As a result of these low wages, restaurant employees suffer from three times the poverty rate as other U.S. workers, and use food stamps twice as much.[65]

Restaurants are the largest employer of people of color, and rank as the second largest employer of immigrants. These workers statistically are concentrated in the lowest paying positions in the restaurant industry. In the restaurant industry, 39% of workers earn minimum wage or lower.[65]

Regulations[edit]

In many countries, restaurants are subject to inspections by health inspectors to maintain standards for public health, such as maintaining proper hygiene and cleanliness. The most common kind of violations of inspection reports are those concerning the storage of cold food at appropriate temperatures, proper sanitation of equipment, regular hand washing and proper disposal of harmful chemicals. Simple steps can be taken to improve sanitation in restaurants. As sickness is easily spread through touch, restaurants are encouraged to regularly wipe down tables, door knobs and menus.[66]

Depending on local customs, legislation and the establishment, restaurants may or may not serve alcoholic beverages. Restaurants are often prohibited from selling alcoholic beverages without a meal by alcohol sale laws; such sale is considered to be activity for bars, which are meant to have more severe restrictions. Some restaurants are licensed to serve alcohol («fully licensed»), or permit customers to «bring your own» alcohol (BYO / BYOB). In some places restaurant licenses may restrict service to beer, or wine and beer.[67]

Occupational hazards[edit]

Food service regulations have historically been built around hygiene and protection of the consumer’s health.[68] However, restaurant workers face many health hazards such as long hours, low wages, minimal benefits, discrimination, high stress, and poor working conditions.[68] Along with the COVID-19 pandemic, much attention has been drawn to the prevention of community transmission in restaurants and other public settings.[69] To reduce airborne disease transmission, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention recommends reduced dining capacity, face masks, adequate ventilation, physical barrier instalments, disinfection, signage, and flexible leave policies for workers.[70]

See also[edit]

- Lists of restaurants

References[edit]

- ^ «Definition of RESTAURANT». Merriam-Webster.

- ^ «Restaurant». Lexico.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020.

- ^ «Conjugaison de restaurer — WordReference.com». wordreference.com.

- ^ «ce qui répare les forces, aliment ou remède fortifiant» (Marguerite d’Angoulême ds Briçonnet, volume 1, p. 70)

- ^ United States Congress. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs (June 22, 1977). Diet Related to Killer Diseases. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ «Take-out restaurants existed in ancient Rome and were called «thermopolia»«. The Vintage News. November 26, 2017.

- ^ Ellis, Steven J. R. (2004): «The Distribution of Bars at Pompeii: Archaeological, Spatial and Viewshed Analyses», Journal of Roman Archaeology, Vol. 17, pp. 371–84 (374f.)

- ^ «Visiting a Bar in Ancient Rome». Lucius’ Romans. University of Kent. July 15, 2016.

- ^ Potter, David S. (2008). A Companion to the Roman Empire. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-7826-6. p. 374

- ^ a b c Mealey, Lorri (December 13, 2018). «History of the Restaurant». The Balance Small Business.

- ^ «Kautilya’s Arthashastra: Book II,»The Duties of Government Superintendents»«.

- ^ a b Roos, Dave (May 18, 2020). «When Did People Start Eating in Restaurants?». History.com.

- ^ a b Gernet (1962:133)

- ^ West (1997:69–76)

- ^ Kiefer (2002:5–7)

- ^ Gernet (1962:133–134)

- ^ Symons, Michael: A History of Cooks and Cooking, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Chevallier 2018, pp. 67–80.

- ^ a b c Fierro 1996, p. 737.

- ^ Rebecca L. Spang, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Harvard University Press, 2001), ISBN 978-0-674-00685-0

- ^ a b c d e f Fierro 1996, p. 1137.

- ^ a b «Restaurant». Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Constantine, Wyatt (May 2012). «Un Histoire Culinaire: Careme, the Restaurant, and the Birth of Modern Gastronomy». Texas State University-San Marcos.

- ^ James Salter (2010). Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days. Random House. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9780307496447.

- ^ Prosper Montagné. «The New Larousse Gastronomique». Éditions Larousse. p. 97. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ^ Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (April 5, 2012). The Physiology of Taste. Courier Corporation. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-0-486-14302-6.

- ^ Paul H. Freedman; Professor Paul Freedman (2007). Food: The History of Taste. University of California Press. pp. 305–. ISBN 978-0-520-25476-3.

- ^ Edward Glaeser (February 10, 2011). Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-101-47567-6.

- ^ Metzner, Paul. Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. Crescendo of the Virtuoso

- ^ «Etymology of Cabaret». Ortolong: site of the Centre National des Resources Textuelles et Lexicales (in French). Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Steven (October 1, 2006). «Abolish restaurants: A worker’s critique of the food service industry». Libcom Library. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ The world’s smallest restaurants, Fox News 23 January 2013. Accessed on 30 June 2022.

- ^ «Beginner’s guide to dining on a cruise». Cruiseable. May 7, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Ford, Elise Hartman (2006). Frommer’s Washington, D.C. 2007, Part 3. Vol. 298. John Wiley and Sons. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-470-03849-9.

- ^ Blackwell, Elizabeth Canning (2008). Frommer’s Chicago 2009. Vol. 627. Frommer’s. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-470-37371-2.

- ^ a b Brown, Monique R. (January 2000). «Host your own chef’s table». Black Enterprise. p. 122.

- ^ Ford, Elise Hartman; Clark, Colleen (2006). D.C. night + day, Part 3. ASDavis Media Group. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-9766013-4-0.

- ^ Miller, Laura Lea (2007). Walt Disney World & Orlando For Dummies 2008. For Dummies. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-470-13470-2.

- ^ Brown, Monique R. (January 2000). «New spin on dining: Hosting a chef’s table can wow guests». Black Enterprise. p. 122.

- ^ Louisgrand, Nathalie. «Revolutionary broth: the birth of the restaurant and the invention of French gastronomy». The Conversation. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ «Who Invented the First Modern Restaurant?». Culture. March 13, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ «Who Invented the First Modern Restaurant?». Culture. March 13, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ «Dîner des Trois Empereurs le 4 juin 1867». menus.free.fr.

- ^ Food in Time and Place : the American Historical Association Companion to Food History. Paul Freedman, Joyce E. Chaplin, Ken Albala. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2014. ISBN 978-0-520-95934-7. OCLC 890089872.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ «Civil Rights Act of 1964: P.L. 88-352» (PDF). senate.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ «Nicholas deB. KATZENBACH, Acting Attorney General, et al., Appellants, v. Ollie McCLUNG, Sr., and Ollie McClung, Jr». LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ^ «Total U.S. Jobs». National Restaurant Association. 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ «Americans’ Dining-Out Frequency Little Changed From 2008». Gallup. January 11, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Gangitano, Alex (March 18, 2020). «Restaurant industry estimates $225B in losses from coronavirus». The Hill. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Diccionario Comentado Del Español; Actual en Colombia. 3rd edition. by Ramiro Montoya

- ^ CRFA’s Provincial InfoStats and Statistics Canada

- ^ ReCount/NPD Group and CRFA’s Foodservice Facts

- ^ «Business economy – size class analysis – Statistics Explained». Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ «Restaurant Industry». SMERGERS Industry Watch. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ 2006 U.S. Industry & Market Outlook by Barnes Reports.

- ^ Phillips, Matt (June 16, 2016). «No one cooks anymore». Quartz (publication). Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Abrams, Rachel; Gebeloff (October 31, 2017). «Thanks to Wall St., There May Be Too Many Restaurants». The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ^ Kerry Miller, «The Restaurant Failure Myth», Business Week, April 16, 2007. Cites an article by H.G. Parsa in Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly, published August 2005.

- ^ Miller, «Failure Myth», page 2

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics, «Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2013 35-2014 Cooks, Restaurant» online

- ^ BLS, «Occupational Outlook Handbook: Food and Beverage Serving and Related Workers» (January 8, 2014) online

- ^ Jiaxi Lu, «Consumer Reports: McDonald’s burger ranked worst in the U.S.,» [1]

- ^ Nestle, Marion (1994). «Traditional Models of Healthy Eating: Alternatives to ‘techno-food’«. Journal of Nutrition Education. 26 (5): 241–45. doi:10.1016/s0022-3182(12)80898-3.

- ^ a b c Jayaraman, Saru (Summer 2014). «Feeding America: Immigrants in the Restaurant Industry and Throughout the Food System Take Action for Change». Social Research. 81 (2): 347–358. doi:10.1353/sor.2014.0019.

- ^ Sibel Roller (2012). «10». Essential Microbiology and Hygiene for Food Professionals. CRC Press. ISBN 9781444121490.

- ^ Danny May; Andy Sharpe (2004). The Only Wine Book You’ll Ever Need. Adams Media. p. 221. ISBN 9781440518935.

- ^ a b Lippert, Julia; Rosing, Howard; Tendick‐Matesanz, Felipe (July 2020). «The health of restaurant work: A historical and social context to the occupational health of food service». American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 63 (7): 563–576. doi:10.1002/ajim.23112. ISSN 0271-3586. PMID 32329097. S2CID 216110536.

- ^ Morawska, Lidia; Tang, Julian W.; Bahnfleth, William; Bluyssen, Philomena M.; Boerstra, Atze; Buonanno, Giorgio; Cao, Junji; Dancer, Stephanie; Floto, Andres; Franchimon, Francesco; Haworth, Charles (September 1, 2020). «How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised?». Environment International. 142: 105832. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. ISSN 0160-4120. PMC 7250761. PMID 32521345.

- ^ «Communities, Schools, Workplaces, & Events». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 30, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

Bibliography[edit]

- Chevallier, Jim (2018). A History of the Food of Paris: From Roast Mammoth to Steak Frites. Big City Food Biographies. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442272828.

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 978-2221078624.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0720-6.

- Spang, Rebecca L. (2000), The Invention of the Restaurant. Harvard University Press

- West, Stephen H. (1997). «Playing With Food: Performance, Food, and The Aesthetics of Artificiality in The Sung and Yuan». Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 57 (1): 67–106. doi:10.2307/2719361. JSTOR 2719361.

- «Early Restaurants in America». UNLV Libraries Digital Collections. University of Nevada Las Vegas. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Appelbaum, Robert, Dishing It Out: In Search of the Restaurant Experience. (London: Reaktion, 2011).

- Fleury, Hélène (2007), «L’Inde en miniature à Paris. Le décor des restaurants», Diasporas indiennes dans la ville. Hommes et migrations (Number 1268–1269, 2007): 168–73.

- Haley, Andrew P. Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880–1920. (University of North Carolina Press; 2011) 384 pp

- Kiefer, Nicholas M. (August 2002). «Economics and the Origin of the Restaurant» (PDF). Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 43 (4): 5–7. doi:10.1177/0010880402434006. S2CID 220628566.

- Lundberg, Donald E., The Hotel and Restaurant Business, Boston : Cahners Books, 1974. ISBN 0-8436-2044-7

- Sitwell, William (2020). The Restaurant: A 2,000-Year History of Dining Out. New York, NY: Diversion Books. ISBN 978-1635766998.

- Whitaker, Jan (2002), Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of the Tea Room Craze in America. St. Martin’s Press.

External links[edit]

The word ‘Restaurant’ derives from the French verb restaurer, meaning to restore. It was first used in France in the 16th century, to describe the thick and cheap soups sold by street vendors that were advertised to restore your health.

It was in 1765 that a Monsieur Boulanger of Paris actually opened a shop selling soups. The sign outside of M. Boulanger’s shop is said to have read, “VENITE AD ME VOS QUI STOMACHO LABORATIS ET EGO RESTAURABO VOS” (Come to me, all who labour in the stomach, and I will restore you.) and this led to the use of the word restaurant to describe such shops. Boulanger did try to add stew to his list of soups but was successfully sued by a number of Parisian traiteurs (people who ran cookhouses). But it was not too long before ‘restaurants’ combined both soup and other food courses, including stews.

But his soup-shop was still a long way off from the types of establishment we think of today when we utter the word restaurant. Nicholas Kiefer in his excellent published article, Economics and the Origin of the Restaurant, has this to say:

“Pressures leading to the creation of the restaurant— with its individual tables, individual orders, flexible dining times convenient to the patrons, and payment by item ordered—came from both those who demanded food away from home and from its suppliers. From the diner’s point of view, the restaurant format offered a kind of privacy. The diner could eat alone or with companions of his or her choosing. The table d’hôte format is more social, but the mix of companions facing a stranger coming to an inn or cookshop [traiteurs] wasn’t always ideal for outsiders. More important, the diner in a restaurant could order, eat, drink, and pay for only and exactly what she wished. In contrast, in the table d’hôte format one ate what one could grab of what was served. Finally, the restaurant patron could eat at the time of his convenience, rather than when the host chose to serve the meal.”

While there were restaurants in some form or other in Paris during the decades preceding the French Revolution, it was this late 18th Century historical event that provided the social conditions for the evolution of the restaurant as we know it today. A restaurant boom occurred at this time through the elimination of restrictive Guild rules coupled with the large number of chefs entering the labour market who had previously been employed by aristocrats who had lost their heads.

As the London Dorchester’s executive chef, Jocelyn Herland, recently remarked:

“If I could go back to any historic period, I would have to say the time after the French revolution of 1789. It was during this time that restaurants, as we know them today, made their appearance. After the French revolution, many chefs who were cooking high-quality cuisine at the houses of noblemen lost their jobs and thus opened their own restaurants.”

So there you have it. The origin of the word Restaurant. Thanks for reading.

About Jim McNeill

I am a blogger on ‘The Social History of the Touraine region of France (37)’ and also ‘The Colonial History of Pennsylvania and the life & Family of William Penn’.

I am a Director of Fresh Ground Group Ltd.

People have been eating outside of the home for millennia, buying a quick snack from a street vendor or taking a travel break at a roadside inn for a bowl of stew and a pint of mead.

In the West, most early versions of the modern restaurant came from France and a culinary revolution launched in 18th-century Paris. But one of the earliest examples of a true restaurant culture began 600 years earlier and halfway around the world.

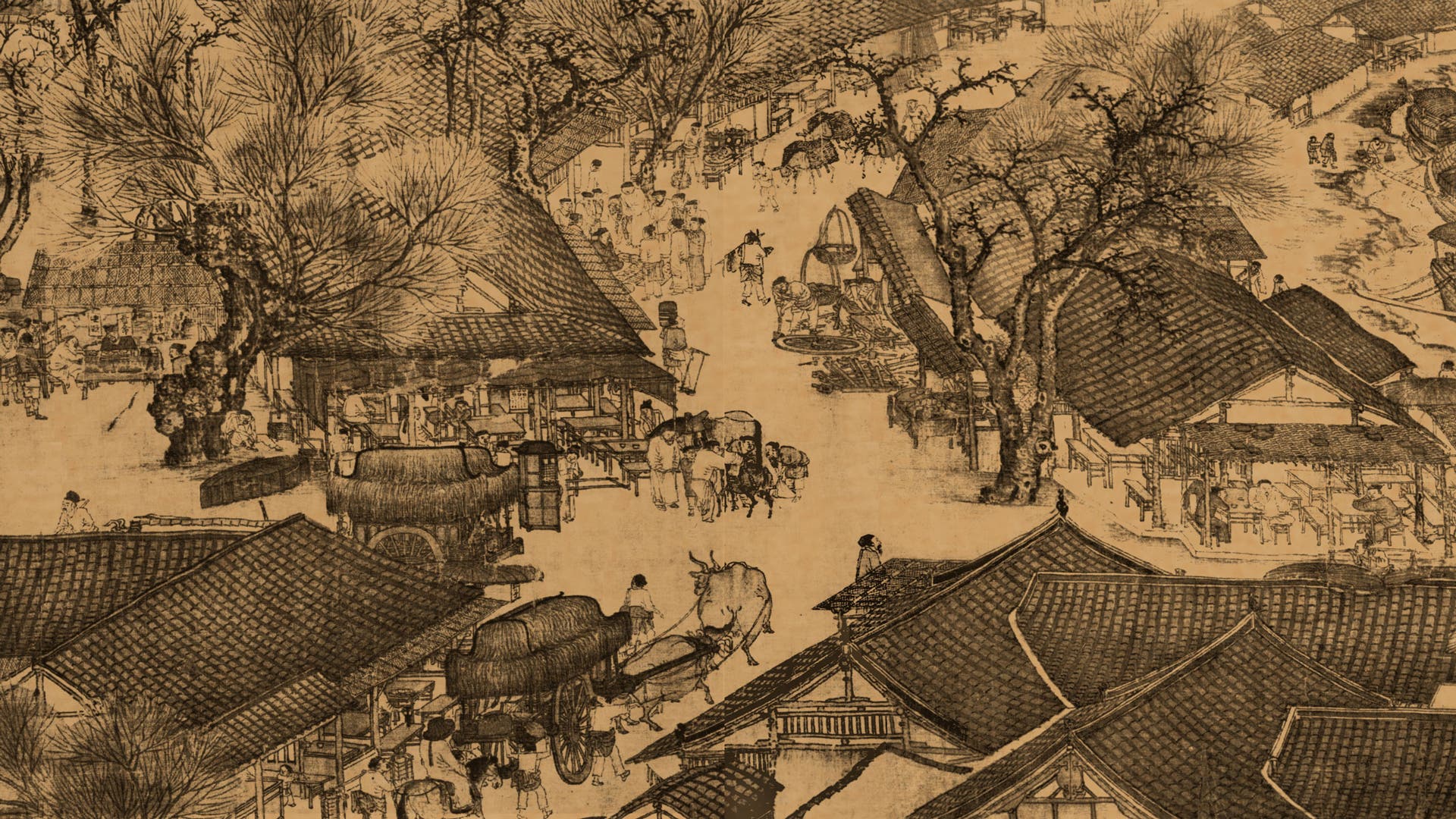

Singing Waiters of the Song Dynasty

<em>A scene in what is thought to be the ancient capital of Kaifeng showing food stalls from</em> a scroll titled ‘Going Up the River at the Qingming Festival’ by Zhang Zeduan, circa 1100.

According to Elliott Shore and Katie Rawson, co-authors of Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants, the very first establishments that were easily recognizable as restaurants popped up around 1100 A.D. in China, when cities like Kaifeng and Hangzhou boasted densely packed urban populations of more than 1 million inhabitants each.

Trade was bustling between these northern and southern capitals of the 12th-century Song Dynasty, explains Shore, a professor emeritus of history at Bryn Mawr College, but Chinese tradesmen traveling outside their home city weren’t accustomed to the strange local foods.

“The original restaurants in those two cities are essentially southern cooking for people coming up from the south or northern cooking for people coming down from the north,” says Shore. “You could say the ‘ethnic restaurant’ was the first restaurant.”

These prototypical restaurants were located in lively entertainment districts that catered to business travelers, complete with hotels, bars and brothels. According to Chinese documents from the era, the variety of restaurant options in the 1120s resembled a downtown tourist district in a 21st-century city.

“You could go to a noodle shop, a dim sum restaurant, a huge place that was fantastically and opulently put together or a little chop suey joint,” says Shore.

The dining experiences at the larger and fancier restaurants were strikingly similar to today. According to a Chinese manuscript from 1126 quoted in Dining Out, patrons of one popular restaurant were first greeted with a selection of pre-plated “demonstration” dishes representing hundreds of delectable options. Then came a well-trained and theatrical team of waiters.

“The waiter took their orders, then stood in line in front of the kitchen and, when his turn came, sang out his orders to those in the kitchen. Those who were in charge of the kitchen were called ‘pot masters’ or were called ‘controllers of the preparation tables.’ This came to an end in a matter of moments and the waiter—his left hand supporting three dishes and his right arm stacked from hand to shoulder with some twenty dishes, one on top of the other—distributed them in the exact order in which they had been ordered. Not the slightest error was allowed.”

In Japan, a distinct restaurant culture arose out of the Japanese teahouse traditions of the 1500s that predated today’s “seasonal” and “local” movements by half a millennium. The 16th-century Japanese chef Sen no Rikyu created the multi-course kaiseki dining tradition, in which entire tasting menus were crafted to tell the story of a particular place and season. Rikyu’s grandsons expanded the tradition to include speciality serving dishes and cutlery that matched the aesthetic of the food being served.

Despite centuries of trade between the East and West, there’s no evidence that the early restaurant cultures of China or Japan influenced later European notions of the restaurant.

The Communal Midday Meal

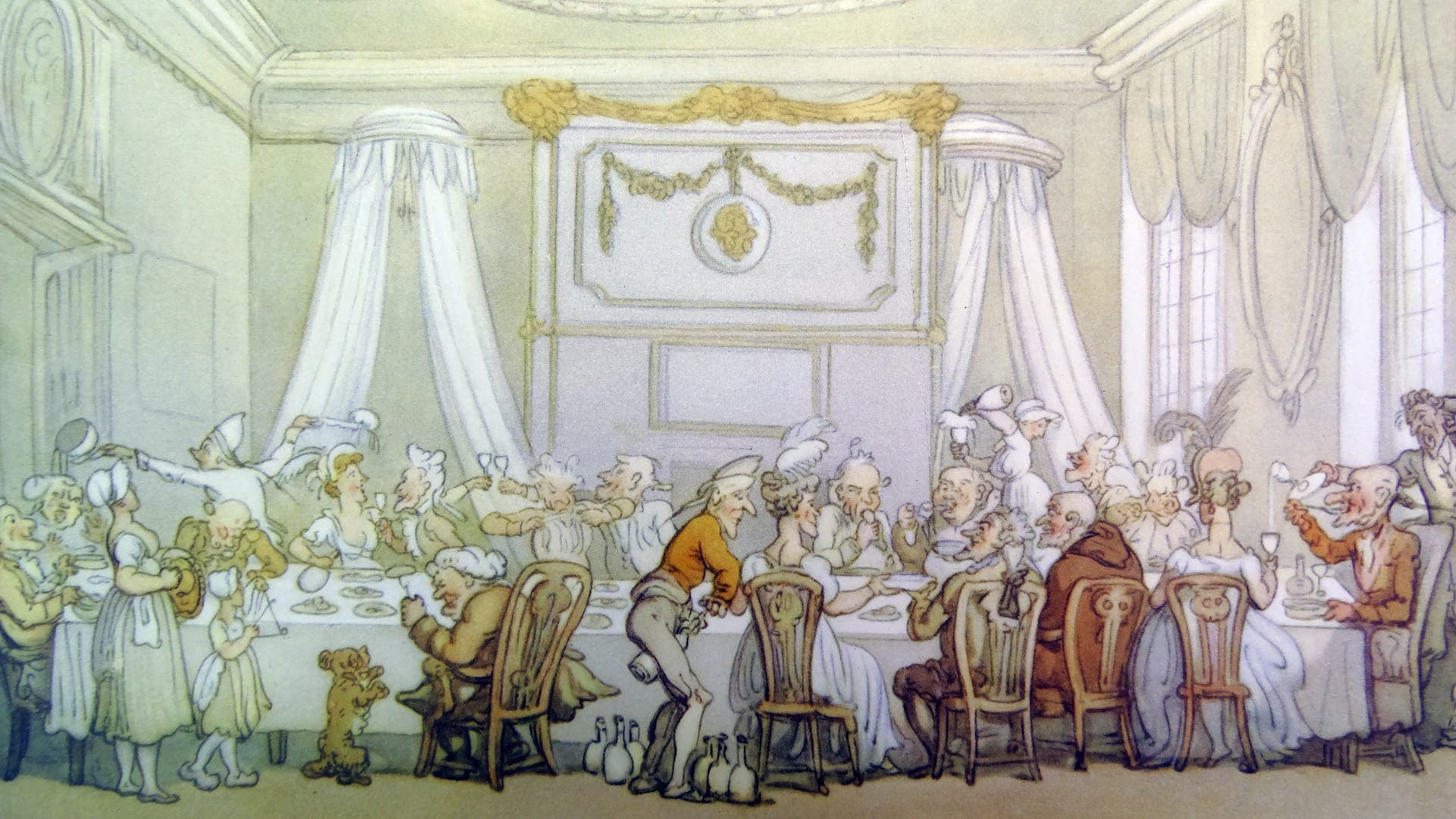

Table d’hôte in Paris.

Around the same time that Japanese chefs were creating full-sensory dining experiences, a separate tradition took hold in the West known in French as the table d’hôte, a fixed price meal eaten at a communal table.

This type of meal, eaten in public with friends and strangers gathered around a family-style spread, might resemble one of today’s hip farm-to-table establishments, but Shore says it wasn’t a real restaurant in several senses.

First, only one meal was served each day precisely at 1 pm. If you weren’t paid up and sitting at the table at one, you wouldn’t get to eat. There was no menu and no choice. The cook at the inn or hotel decided what was prepared and served, not the guests.

Variations on the table d’hôte first appeared in the 15th-century and persisted beyond the arrival of the first restaurants. In England, working-class communal meals were called “ordinaries” and Simpson’s Fish Dinner House, founded in 1714, served up a popular “fish ordinary” for two shillings consisting of “a dozen oysters, soup, roast partridge, three more first courses, mutton and cheese,” according to Dining Out.

First French Restaurants Were Bouillon Shops

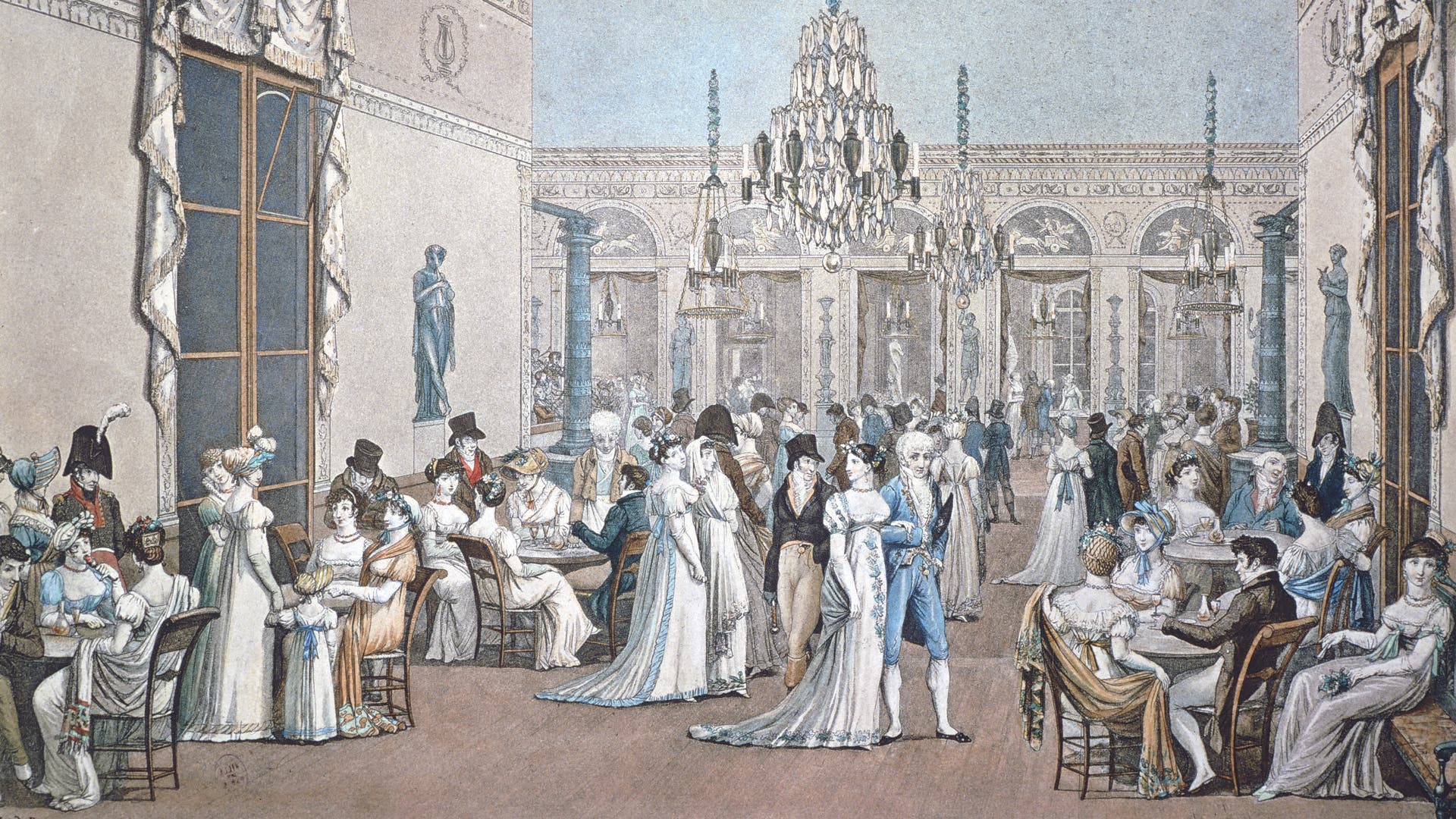

18th-century Cafe Frascati in Paris.

Legend says that the first French restaurants popped up in Paris after the French Revolution when the gourmet chefs of the guillotined aristocracy went looking for work. But when historian Rebecca Spang of Indiana University looked into this popular origin story, she found something completely different.

The word restaurant comes from the French verb restaurer, “to restore oneself,” and the first true French restaurants, opened decades before the 1789 Revolution, purported to be health-food shops selling one principle dish: bouillon. The French description for this type of slow-simmered bone broth or consommé is a bouillon restaurant or “restorative broth.”

In her book, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Gastronomic Culture, Spang explains that the very first French restaurants arrived in the 1760s and 1770s, and they capitalized on a growing Enlightenment-era sensibility among the wealthy merchant class in Paris.

“They believed that knowledge was obtained by being sensitive to the world around you, and one way of showing sensitivity was by not eating the ‘coarse’ foods associated with common people,” says Spang. “You might not have aristocratic forebears, but you can show that you’re something other than a peasant by not eating brown bread, not relishing onions and sausage, but wanting delicate dishes.”

Bouillon fit the bill perfectly. It was all-natural, bland, easy to digest, yet packed full of invigorating nutrients. But Spang credits the success and rapid growth of these early bouillon restaurants not just to what was being served, but how it was served.

“The restaurateurs innovated by copying the service model that already existed in French café culture,” says Spang. “They sat customers at a small, cafe-size table. They had a printed menu from which people ordered dishes as opposed to the tavern keeper saying, ‘this is what’s for lunch today.’ And they were more flexible in their meal hours—everybody didn’t have to get there at 1 p.m. and eat whatever was on the table.”

Once the bouillon restaurants caught on, it didn’t take long for other items to show up on the menu. A little wine, perhaps, some stewed chicken. By the late 1780s, the health-conscious bouillon shops had evolved into the first grand Parisian restaurants like Trois Frères and La Grande Tavene de Londres that would serve as the archetype of fine restaurant dining for the next century.

Restaurants Come to America

As shown by the history of restaurants in both China and France, you can’t have restaurants without a large and hungry urban population. So it makes sense that the first fine-dining restaurant in America was opened in New York City in the 19th century.

Delmonico’s opened its doors in 1837 featuring luxurious private dining suites and a 1,000-bottle wine cellar. The restaurant, which remains at the same Manhattan location (although it closed its doors during the 2020 Covid-19 crisis), claims to be the first in America to use tablecloths, and its star chefs not only invented the famous Delmonico steak, but also gourmet classics like eggs Benedict, baked Alaska, Lobster Newburg and Chicken à la Keene.

Ошибка в вопросе

Вопрос 14:

Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis et onerati estis, et ego reficiam

vos.

Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis, et ego X vos.

Первая строка — стих из Евангелия от Матфея: «Приидите ко мне, все

труждающиеся и обременённые, и я успокою вас». Вторая строка —

по-современному говоря, слоган, который в 1765 году написал на своей

вывеске парижский владелец суповой кухни. Латинское слово X [икс] в

европейских языках превратилось в Y [игрек]. Восстановите корень X-а

[икса] и напишите Y [игрек] по-русски.

Ответ: Ресторан.

Пропущено слово «restaurabo», то есть всё вместе переводится примерно

«Приидите ко мне все, у кого работают желудки, и я восстановлю ваши

силы».

Источник(и):

1. http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Where_does_the_word_restaurant_come_from

2. http://www.vsr-koeln.de/pageID_7882928.html

3. http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ресторан

Борис Шойхет (Франкфурт-на-Майне)

Ваше имя: *

Ваш e-mail: *

Категория: *

Сообщение: *

Защита от роботов: *

11 + 1 =

Решите этот несложный пример. Вы должны видеть три слагаемых. Если слагаемых два, то прибавьте к сумме 2.