- Students

- Staff

- Schools & services

- Sussex Direct

- Canvas

- Schools

- ITS

- Library

- Professional services

- Guide to Punctuation

- Introduction

- Why Learn to Punctuate?

- The Full Stop, the Question Mark and the Exclamation Mark

- The Comma

- The Colon and the Semicolon

- The Apostrophe

- The Hyphen and the Dash

- Capital Letters and Abbreviations

- Quotations

-

- Quotation Marks and Direct Quotations

- Scare Quotes

- Quotation Marks in Titles

- Talking About Words

- Miscellaneous

- Punctuating Essays and Letters

- Bibliography

There is one very special use of quotation marks which it is useful to know

about: we use quotation marks when we are talking about words. In this

special use, all varieties of English normally use only single quotes, and not

double quotes (though some Americans use double quotes even here). (This is

another advantage of using double quotes for ordinary purposes, since this

special use can then be readily distinguished.) Consider the following

examples:

- Men are physically stronger than women.

- `Men’ is an irregular plural.

In the first example, we are using the word `men’ in the ordinary way, to refer

to male human beings. In the second, however, we are doing something very

different: we are not talking about any human beings at all, but instead we are

talking about the word `men’. Placing quotes around the word we are talking

about makes this clear. Of course, you are only likely to need this device when

you are writing about language, but then you should certainly use it. If you

think I’m being unnecessarily finicky, take a look at a sample of the sort of

thing I frequently find myself trying to read when marking my students’ essays:

- *A typical young speaker in Reading has done, not did, and usually

also does for do and dos for does.

I’m sure you’ll agree this is a whole lot easier to read with some suitable

quotation marks:

- A typical young speaker in Reading has `done’, not `did’, and usually

also `does’ for `do’ and `dos’ for `does’.

Failure to make this useful orthographic distinction can, in rare cases, lead to

absurdity:

- The word processor came into use around 1910.

- The word `processor’ came into use around 1910.

If what you mean is the second, writing the first will create momentary havoc in

your reader’s mind. (The second statement is true; the first is wrong by about

70 years.) Here we have a particularly clear example of the way in which good

punctuation works: in speech, the phrases the word processor and the word

`processor’ sound quite different, because they are stressed differently; in

writing, the stress difference is lost, and punctuation must step in to do the job.

Printed books usually use italics for citing words, rather than quotation

marks. If you are using a keyboard which can produce italics, you can use

italics in this way, and indeed this practice is preferable to the use of quotes.

In one circumstance, though, italics are not

possible: when we are providing brief translations (or glosses, as they are

called) for foreign words. Here’s an example:

- The English word `thermometer’ is derived from the Greek words

thermos `heat’ and metron `measure’.

This example shows the standard way of mentioning foreign words: the foreign

word is put into italics, and an English translation, if provided, follows in

single quotes, with no other punctuation. Observe that neither a comma nor

anything else separates the foreign word from the gloss.

You can even do this with English words:

- The words stationary `not moving’ and stationery `writing materials’

should be carefully distinguished.

In this case, it is clearly necessary to use italics for citing English words,

reserving the single quotes for the glosses.

Summary of quotation marks:

- Put quotation marks (single or double) around the exact

words of a direct quotation. - Inside a quotation, use a suspension to mark omitted

material and square brackets to mark inserted

material. - Use quotation marks to distance yourself from a word or

phrase or to show that you are using it ironically. - Place single quotation marks around a word or phrase

which you are talking about.

Copyright © Larry Trask, 1997

Maintained by the Department of Informatics, University of Sussex

Every teacher wonders how to teach a word to students, so that it stays with them and they can actually use it in the context in an appropriate form. Have your students ever struggled with knowing what part of the speech the word is (knowing nothing about terminologies and word relations) and thus using it in the wrong way? What if we start to teach learners of foriegn languages the basic relations between words instead of torturing them to memorize just the usage of the word in specific contexts?

Let’s firstly try to recall what semantic relations between words are. Semantic relations are the associations that exist between the meanings of words (semantic relationships at word level), between the meanings of phrases, or between the meanings of sentences (semantic relationships at phrase or sentence level). Let’s look at each of them separately.

Word Level

At word level we differentiate between semantic relations:

- Synonyms — words that have the same (or nearly the same) meaning and belong to the same part of speech, but are spelled differently. E.g. big-large, small-tiny, to begin — to start, etc. Of course, here we need to mention that no 2 words can have the exact same meaning. There are differences in shades of meaning, exaggerated, diminutive nature, etc.

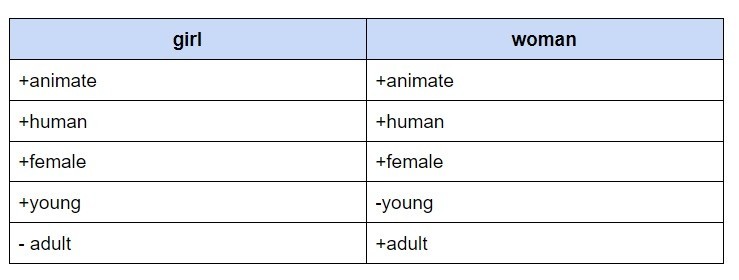

- Antonyms — semantic relationship that exists between two (or more) words that have opposite meanings. These words belong to the same grammatical category (both are nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). They share almost all their semantic features except one. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1998) E.g.

- Homonyms — the relationship that exists between two (or more) words which belong to the same grammatical category, have the same spelling, may or may not have the same pronunciation, but have different meanings and origins. E.g. to lie (= to rest) and to lie (= not to tell the truth); When used in a context, they can be misunderstood especially if the person knows only one meaning of the word.

Other semantic relations include hyponymy, polysemy and metonymy which you might want to look into when teaching/learning English as a foreign language.

At Phrase and Sentence Level

Here we are talking about paraphrases, collocations, ambiguity, etc.

- Paraphrase — the expression of the meaning of a word, phrase or sentence using other words, phrases or sentences which have (almost) the same meaning. Here we need to differentiate between lexical and structural paraphrase. E.g.

Lexical — I am tired = I am exhausted.

Structural — He gave the book to me = He gave me the book.

- Ambiguity — functionality of having two or more distinct meanings or interpretations. You can read more about its types here.

- Collocations — combinations of two or more words that often occur together in speech and writing. Among the possible combinations are verbs + nouns, adjectives + nouns, adverbs + adjectives, etc. Idiomatic phrases can also sometimes be considered as collocations. E.g. ‘bear with me’, ‘round and about’, ‘salt and pepper’, etc.

So, what does it mean to know a word?

Knowing a word means knowing all of its semantic relations and usages.

Why is it useful?

It helps to understand the flow of the language, its possibilities, occurrences, etc.better.

Should it be taught to EFL learners?

Maybe not in that many details and terminology, but definitely yes if you want your learners to study the language in depth, not just superficially.

How should it be taught?

Not as a separate phenomenon, but together with introducing a new word/phrase, so that students have a chance to create associations and base their understanding on real examples. You can give semantic relations and usages, ask students to look up in the dictionary, brainstorm ideas in pairs and so on.

Let us know what you do to help your students learn the semantic relations between the words and whether it helps.

Присоединяйтесь к Reverso, это удобно и бесплатно!

английский

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

корейский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

Показать больше

(греческий, хинди, тайский, чешский…)

чешский

датский

греческий

фарси

хинди

венгерский

словацкий

тайский

Показать меньше

русский

Синонимы

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

корейский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

Показать больше

чешский

датский

греческий

фарси

хинди

венгерский

словацкий

тайский

Показать меньше

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

We are talking about a word.

We are talking about learning words directly from a dictionary.

Речь идет о выучивании слов прямо из словаря.

We are talking about a visible letter R indicating the word Refurbished.

Presenting a paper swan figurine as a gift, we are now talking about the main thing without saying a word.

Преподнося в подарок фигурку бумажного лебедя, мы и теперь говорим о главном, не произнося ни слова.

Результатов: 3579531. Точных совпадений: 1. Затраченное время: 504 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

© 2013-2022 Reverso Technologies Inc. Все права защищены.

I’m not talking about onomatopoeia—I don’t mean a word that describes a sound—I mean something along the lines of an aptronym, i.e. a perfect name such as Anthony Camera for a photographer (true story). What is the word for when a word just sounds like exactly what it means? I heard the word for this once, long ago, and have since forgotten it.

«Push» and «Pull» might be examples, in that the sounds they form evoke the physical actions denoted.

asked Jun 7, 2011 at 17:56

Taj MooreTaj Moore

1,5193 gold badges13 silver badges20 bronze badges

Perhaps you’re thinking of an ideophone, a broader idea than just onomatopoeia (not restricted to sound).

Mark Dingemanse explains ideophones:

English, for example, has ideophonic words like glimmer, twiddle, tinkle which are depictive of sensory imagery: their form betrays something of their meaning in ways that words «chair» and «dog» do not.

answered Jun 7, 2011 at 18:30

aedia λaedia λ

10.6k9 gold badges44 silver badges69 bronze badges

4

This Wikipedia article may be helpful.

Of the various terms mentioned in the article, phenomime might be close to what you are looking for.

answered Feb 26, 2020 at 12:40

This post took me over 2 weeks to write and I was researching for days and days and days before I even started typing. That’s because measuring vocabulary is hard! I can calculate a student’s guided reading level like nobody’s business. I can tell you, in great detail, about a student’s spelling strengths and math skills. But when it comes to vocabulary, it’s a bit of a head scratcher. How do I quantify that huge, amorphous mass into a grade? Using the quizzes with our weekly Jargon Journals gave me some data about student understanding of individual words, but what if I want to know about a general vocabulary levels? Is there some sort of benchmark? Is there an easy way to measure if a student understands more than a word’s definition?

Nope.

That’s because vocabulary is like air. Take a second to think about air. You probably haven’t given it much consideration lately. Even though we’re surrounded by it, we take for granted that it even exists. Air is extremely difficult to hold, so if I want to understand the nature of air I may begin by collecting a sample in a bottle. Because air provides little sensory input, based on my sample, I may become convinced that all air is round without realizing that the sample has taken the shape of its container. In this case I’m studying the bottle not the material inside.

It’s the same with vocabulary. It undergirds every communication to the point that it becomes invisible. If we’re looking to measure the richness of a student’s vocabulary, it’s easy to look at one multiple-choice test and assume that we’ve uncovered the sum total of information. But thinking like that takes us right back to analyzing the bottle. Acquiring vocabulary is a fluid process. As one article points out, learning vocabulary is multidimensional, incremental, context dependent, and develops across a lifetime. That’s a lot to consider when designing assessments and, for those reasons, there is no single, perfect measure of vocabulary knowledge. If we want to measure the contents of our vocabulary bottles, we have to rely on more informal assessments. In this post I’ll go over some different vocabulary assessments and ways they may work in your classroom.

Why Are You Assessing?

The first step to measuring vocabulary is to identify your purpose in assessing. What are you hoping to get from this assessment? Why does the information matter? You have to decide if you’re looking to measure vocabulary breadth (the amount of words a student understands) or vocabulary depth (the amount of understanding a student has about a word).

How Are You Assessing?

If you decide that your purpose is to measure vocabulary breadth, then a multiple choice test is an efficient way to quickly measure a student’s understanding of word meaning. If you’re using the Jargon Journals, the end-of-unit quizzes can give you valuable information about which words students are starting to feel comfortable with and which words may need further exposures.

But what if you’re looking for something indicative of vocabulary depth? In that case, a multiple choice format probably isn’t precise enough. You’ll need assessments that tap into layers of understanding.

If we want to assess how much students know about a word, we first have to decide what it actually means to know a word. Often we look at one aspect–definition–and use that as a definitive measure, but recalling meaning is just one part of this vocabulary puzzle. If you’ve ever had students who could tell what a word means, but completely misuse it, you understand. In the book Creating Robust Vocabulary: Frequently Asked Questions & Extended Examples the authors use an example of the word devious. Based on the definition in the dictionary (straying from the right course; not straightforward), you can understand why a student whose experience with this word is limited to the definition may write, “He was devious on his bike.”

Confusion like this happens because knowing a word is not an all-or-nothing situation. Wouldn’t it be nice if it were! Instead, word understanding happens on more of a continuum. On one side we have “I didn’t even know this word existed” on the other side is “I can use this word naturally, automatically, and accurately when speaking and writing.” We’re at different places with different words and it takes time and experience before any word can be utilized at that deeper level. In other words:

…Learning a word is not like turning on a light, where one moment we do not know a word (the light is off), and the next moment we suddenly learn the word completely (the light is on). Learning word meanings is more like a dimmer switch on a light; we learn words gradually as the light slowly becomes brighter and brighter over time. Put another way, we learn and acquire words by degrees. —Vocabulary Their Way, p.237

So, yes we need to know definitions, but that’s just the starting point for knowing a word. In an article from 2000, Vocabulary Processes, authors William Nagy and Judith Scott synthesized vocabulary research to identify five aspects of word knowledge. They are:

- Incrementality— Knowing a word is a matter of degrees. Every time we encounter a word, our knowledge of that word becomes a bit more precise. Take, for example, a relatively common word like free. How has your understanding of that word deepened over time?

- Multidimensionality— Knowing a word extends beyond recalling the definition. In the book, Greek & Latin Roots: Keys to Building Vocabulary (p. 13) the authors give these examples of multidimensionality: Allege and believe share a core meaning of “certainty” or “conviction.” Yet, they are conceptually distinct…Collocation, or the frequent placing together of words, is also a part of word knowledge. We can talk about a storm front, but not a storm back. Similarly, we can have a storm door and a storm window, but not a storm ceiling or a storm floor.

- Polysemy–Knowing a word means understanding its various meanings. The more common the word, the more meanings it has. For example, the word draw is a word every preschooler knows, but they would be confused by “draw water from the well” or “draw your chair over to the window” or “draw a conclusion about what happened.” The meaning of a word relies, ultimately, on the context in which it is used. Sometimes the context is explicit, but it often must be inferred.

- Interrelatedness–Knowing a word means knowing how it’s linked to other words. This often involves knowing its attributes and how it is related to other words or concepts. Think of all the things you know about even a simple concept like dog. You maybe thought of words like pet or furry. Or maybe the name of your own pet dog. And what about mammal, companion, loyal, breed? A word can only be defined by using other words, so by their very nature words are connected.

- Heterogeneity–Knowing a word at a deep level varies substantially depending on the word. The depth of understanding required to know the word the is vastly different than the understanding required by afterhyperpolarization.

Knowing a word is a complex business indeed! Since we’re not allowed to go poking around in children’s brains, to really measure a student’s vocabulary depth we have to think about the behaviors that can show us a student knows a word. As Greg Conderman says, “Truly knowing a word encompasses the entire spectrum of language: listening, speaking, reading, and writing.” So looking at a student’s speaking and writing are good places to start. We can surmise a lot about vocabulary depth when we focus on a student’s expressive vocabulary–that is, the words a student knows well enough to use when communicating. By counting the number of Tier 2 and 3 words (or as some researchers call them, “rare” words) a student uses, we have a clear picture of the richness a student’s vocabulary. The most efficient way to do this is to look at a child’s writing.

Collect a writing sample from each student. Count the number of rare words the writer uses. Then count the total number of words in the piece. Obviously, the higher the frequency of rare words, the deeper a student’s expressive vocabulary. In our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack, we have a form to help you organize this data. Because vocabulary growth happens over time, the form provides space for on-going assessment.

This process is tedious, however, especially if your writers compose long stories. Doing this 2-3 times a year would be enough to give you a picture of that child’s vocabulary development. For the short term, there are many other assessments to indicate a student’s word knowledge.

One option is to do the Rare Words assessment, but have the students participate in the scoring. For this to be effective, students have to be familiar with rare words. If you’ve been doing vocabulary study in your classroom, they will have some understanding of what you mean when you talk about rare words. With the students, I use the term “WOW!” words. These are words that are perhaps longer, more challenging. They may take a common idea–for example, happiness–and express it in a more complex way like merriment. These are words that if you heard someone use them you would say, “Wow!” For this activity we won’t make a distinction between Tier 2 and Tier 3 words because words from both groups are indicative of higher levels of comprehension and expression.

To complete this assessment, make sure each student has a recently finished written piece. Distribute a WOW! Words self-assessment to the students and ask them to look through their writing for examples of WOW! words. They should list any words they find. At the bottom is a space for students to compare the number of WOW! words to the story’s total words. You may consider skipping this step if your students are young and this task is too tedious or frustrating for them. There is also room for students to reflect on the richness of their vocabulary and determine what they can do better as a writer.

By involving students in this assessment, you lose some accuracy. They may not recognize a word you would consider rare or, more likely, they will include words you don’t think qualify. It’s not uncommon to see a word like tent included on a child’s list because camping with his family is important to him. In this activity, complete accuracy isn’t as important as awakening your learners to the realization that they should be using expansive vocabulary in their writing. By fostering a classroom culture where words are cherished, you create eagerness among your students to learn and use richer words.

Another way to encourage word awareness is to give students a Vocabulary Self-Rating Chart. On this task, you provide the words. The words you choose will depend on your why for assessment. Are you using this as a pre-test for your next science unit? Is it a follow-up to see which words have been retained from last November’s Jargon Journals? Are you giving the students words you’ve never taught them to get a general feel of their vocabulary levels? When you’ve identified your purpose, write the words on the left column of the page. There’s a form that includes space for 5 words or one that has space for 10 words. Each student needs a form. Students read the words and mark the column that matches their familiarity with each word. Only one column should be marked per word. The columns are labeled:

- I’ve never seen this word.

- I’ve seen it, but don’t know it.

- I know something about this word. I think it means______.

- I know this word well. I can use it in a sentence:

To score the assessment, the number of each column determines the points to be awarded. If you distribute the 5-word assessment and the student correctly fills in a sentence and definition for two words (column 4), correctly writes a definition for one word (column 3), and checks column 2 twice (I’ve seen it, but don’t know it), the total score is 4+4+3+2+2=15.

Even if students don’t know anything about the word, they’re still awarded 1 point. It’s important to honor where they are right now in their learning. If students recognize that there is value in admitting that you do not yet know something, they’re more receptive to filling that gap in knowledge.

If a student attempts a definition or sentence, but is incorrect, they receive 2 points for that word. The student has seen the word at some point, but doesn’t know what it means (even if she thinks she does!).

You’ll notice on this ranking that the highest level of understanding is demonstrated by using the word in a sentence. That’s because it takes 10-15 exposures to a word in meaningful context before it becomes an available part of our expressive vocabularies. And if a student struggles in school, it may take up to 40 experiences with a word before it is mastered. Therefore, be wary of vocabulary tasks that expect students to accurately use a new word in the context of a sentence at the introductory stage of learning. Think about how comfortable you are with new words. If you learn that the word procrustean means marked by arbitrary often ruthless disregard of individual differences or special circumstances, are you now comfortable using that word in context in front of someone else? What about immediately having to use procrustean correctly for a grade? If you’re assessing to see if students have mastered a word, writing sentences is a good exercise. If you’re measuring anything less than mastery, asking students to use new vocabulary words in context will yield a lot of poorly written sentences and potentially stifle any excitement among students about expanding their vocabularies.

Another form in our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack for student self-assessment is the Vocabulary Knowledge Scale. It’s similar to the Vocabulary Self-Rating Chart, but provides additional space for students to decide if they think they know a word or absolutely know a word. The form is assessed by adding the number of each question marked. If on one word a student marks the third choice and adds a correct definition, he gets 3 points. If he marks the 5th choice and adds a definition and sentence, he gets 5 points. If he marks any choice, but has an incorrect word meaning, he gets 2 points.

The words you add to the page will be determined by your purpose in giving the assessment. If it’s a social studies post-test, you’ll include the words from the unit. If you’re curious about general vocabulary depth, you may include any Tier 2 words that the class hasn’t studied.

If you’re wanting students to make connections among words, don’t underestimate the power of semantic mapping (or word webbing, as I call it in my classroom). This is an oldie, but a goodie. In semantic mapping, the teacher chooses an important vocabulary word with which she wants her students to make connections. Maybe the word is orbit based on a science study of the moon. Maybe the word is eagerly because it will be used in a class read-aloud. Maybe it’s not even an entire word, but a root like tract that the students need to practice. Whichever key word is chosen, it is added to the center of the map. A few additional important words may be added by the teacher. Lines are added to connect important words to the key word. This is all that can be done ahead of time, the rest of the information comes from the students.

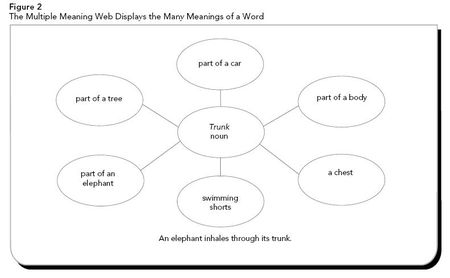

In these 2 examples from Reading Rockets you can see different uses of a word map. In the first one, the purpose is to get students to examine the multiple meanings of the word trunk.

The key word for this map is, of course trunk. The teacher has added some supporting ideas and connected them with lines to the center of the chart. The rest of the information will be added by the students. As part of a class discussion, she’ll have them contribute their background knowledge about the different trunks and she will add it as offshoots from the appropriate circle.

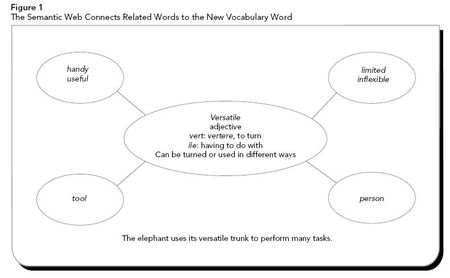

In this second word web, the idea is to introduce students to the word versatile.

She has completed the framework of the web and will look for student ideas to contribute to further information for each word.

By using a chart to visually show students how their background knowledge connects to new learning, you offer a powerful too for helping students retain this fresh information. As Kellie Buis says in her book Making Words Stick (p. 20):

Semantic mapping can make vocabulary meaningful and memorable in ways that reading text in a linear left-to-right fashion alone cannot. It can make vocabulary knowledge public. It can make vocabulary concrete in ways spoken language alone cannot. The techniques of webbing, clustering, or mapping helps students generate nonlinear associations and ideas about words. It assists them in being interested in the words. It allows them to feel connected to the important words, and makes them part of the vocabulary learning process.

Word webbing is something that, given enough teacher supported practice, even 2nd graders can learn to do independently. I’ve done it as a whole group with my preschoolers, so I’m sure it’s accessible to kindergarten and 1st grade classes as a shared writing activity. Regardless of the grade, as with any strategy you will want to start this by modeling. Depending on the skill level of your students, it may be appropriate to have students use their vocabulary journals to make individual copies of what you record on the chart. You can ask them to draw the map on a page of their notebook or distribute a word web from our Tools for Vocabulary Instruction pack.

As a follow-up, you may want the students to do some extensions with the web. Having them reexamine the words they’ve generated will help them retain the information and provide you with sense of how well they internalized the vocabulary. You may ask the students to:

- Pick one of the words and write two synonyms.

- Pick one of the words and write two antonyms.

- Pick one of the words and write your own definition.

- Pick one of the words and tell a personal connection to that word.

- Pick one of the words and draw a picture to illustrate the word. Explain how your picture matches the word’s meaning.

If you’re interested in knowing how well the words have been mastered, you may ask students to pick one of the words and use it in a sentence.

How you score the activity will depend on what you ask the students to do. If they have created their own word webs, you can collect those and assess them for depth of understanding.

Another assessment tool is vocabulary sorts. I’ll let Vocabulary Their Way (p.242) sum it up more eloquently than I can:

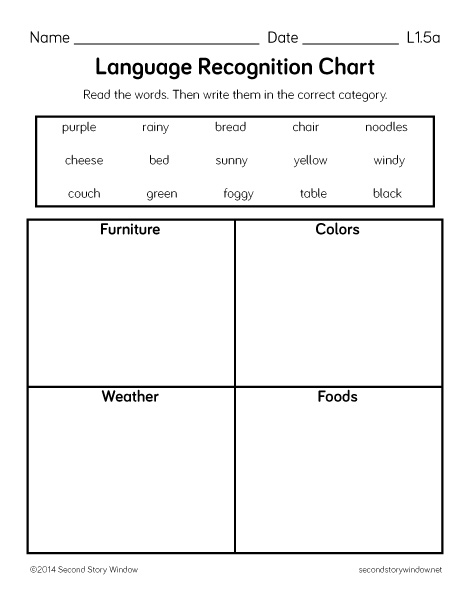

Concept sorting is a dynamic way to assess students’ conceptual knowledge as they organize, categorize, and arrange related concepts before, during, or after a lesson or unit of study. Asking students to explain their thinking, either in discussion or writing, provides valuable assessment information regarding the depth of their vocabulary knowledge and their ability to make connections across words in the sort.

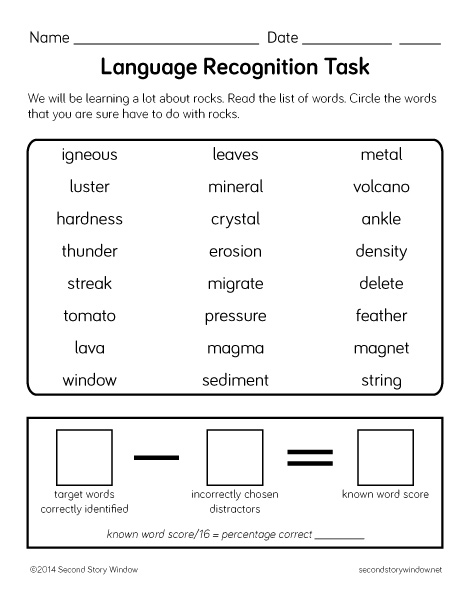

There are different formats and different purposes for a vocabulary sort. As a conclusion to a social studies unit on community, you may give students a set of word cards and ask them to sort the words into either the Goods category or Services. Prior to a science unit, you may give students a page and ask students to circle all of the words that relate to your upcoming topic. This Language Recognition Task can serve as a pretest to see what information students already have or a post test to see what has been retained.

A caution with this sort of assessment is that students may make connections you didn’t anticipate. For example, if a student knows that glass is made from sand and sand is made of tiny rocks, he may circle window as a rock related word because windows are made of glass.

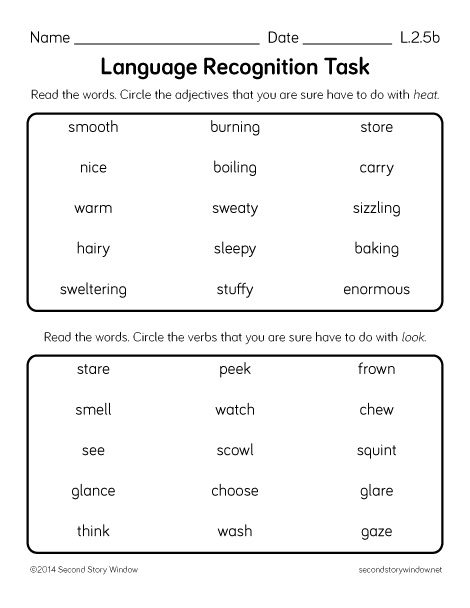

A Language Recognition Task can be used for vocabulary outside of content areas. In the CCSS, 2nd graders are supposed to distinguish shades of meaning among closely related verbs and adjectives. With this assessment, the teacher can see how many words for look or hot or throw a student knows.

Don’t let all this talk of assessment and expressive and context and depth overwhelm you. The airy nature of vocabulary makes it difficult to manage, but, just like the air, once you realize it exists you pay more attention to it. When you raise student awareness of the power of words they become excited about learning more. Let the assessments help you do that. You’re not expected to assign them all, in fact none of them may even be useful for your class, but anytime you have students thinking about words they already know and attach them to words they should know, you’re going a long way to increase their powers of expression and comprehension.

Check out our other posts about vocabulary:

Why Vocabulary Matters

Acquiring Vocabulary with an Interactive Vocabulary Notebook

Tools for Vocabulary Instruction