In

the vocabulary of the English language there is a considerable layer

of words called barbarisms. These are words of foreign origin which

have not entirely been assimilated into the English language.

They bear the appearance of a’borrowing and are felt as something

alien to the native tongue. The role foreign borrowings played in the

development of the English literary language is well known, and the

great majority of these borrowed words now form part of the rank and

file of the English vocabulary. It is the science of linguistics, in

particular its branch etymology, that reveals the foreign nature of

this or that word. But most of what were formerly foreign borrowings

are now, from a purely stylistic position, not regarded as foreign.

But still there are some words which retain their foreign appearance

to a greater or lesser degree. These words, which are called

barbarisms, are, like archaisms*, also considered to be on the

outskirts of the literary language. *

Most

of them have corresponding English synonyms; e. g. chic (=stylish);

bon mot (=a clever witty saying); en passant (— in passing); Ы

infinitum (= to infinity) and many other words and phrases.

It

is very important for purely stylistic purposes to distinguish

between barbarisms and foreign words proper. Barbarisms are words

which have already become facts of the English language. They are, as

it were, part and parcel of the English word-stock, though they

remain on the outskirts of the literary vocabulary. Foreign words,

though used for certain stylistic purposes, do not belong to the

English vocabulary. They are not registered by English dictionaries,

except in a kind of addenda which gives the meanings of the

foreign words most frequently used in literary English. Barbarisms

are generally given in the body of the dictionary.

In

printed works foreign words and phrases are generally italicized to

indicate their alien nature or their stylistic value. Barbarisms, on

the contrary, are not made conspicuous in the text unless they bear a

special bad of stylistic information.

There

are foreign words in the English vocabulary which fulfil a

terminological function. Therefore, though they still retain their

foreign

appearance, they should not be regarded as barbarisms. Such words as

ukase, udarnik, soviet, kolkhoz and the like denote certain concepts

which reflect an objective reality not familiar to English-speaking

communities. There are no names for them in English and so they have

to be explained. New concepts of this type are generally given the

names they have in the language of the people whose reality they

reflect.

Further,

such words as solo, tenor, concerto, blitzkrieg (the blitz),

luftwaffe and the like should also be distinguished from barbarisms.

They are different not only in their functions but in their nature as

well; They are terms. Terminological borrowings have no synonyms;

barbarisms, on the contrary, may have almost exact synonyms.

It

is evident that barbarisms are a historical category. Many foreign

words and phrases which were once just foreign words used in literary

English to express a concept non-existent in English reality, have

little by little entered the class of words named barbarisms and many

of these barbarisms have gradually lost their foreign peculiarities,

become more or less naturalized and have merged with the native

English stock of words. Conscious, retrograde, spurious and strenuous

are words in Ben Jonson’s play «The Poetaster» which were

made fun of in the author’s time as unnecessary borrowings from the

French. With the passing of time they have become common English

literary words. They no longer raise objections on the part of

English purists. The same can be said of the words .scientific,

methodical, penetrate, function, figurative, obscure, and many

others, which were once barbarisms, but which are now lawful members

of the common literary word-stock of the language.

Both

foreign words and barbarisms are widely used in various styles of

language with various aims, aims which predetermine their typical

functions.

One

of these functions is to supply local colour. In order to depict

local conditions of life,- concrete facts and events, customs and

habits, special carets taken to introduce into the passage such

language elements as will reflect the environment. In this respect a

most conspicuous role is played by the language chosen. In «Vanity

Fair» Thackeray takes the reader to a small German town where a

boy with a remarkable appetite is made the focus of attention. By

introducing several German words into his narrative, the author gives

an indirect description of the peculiarities of the German щепи

and the environment in general.

«The

little .boy, too, we observed, had a famous appetite, and consumed

schinken, an&braten, and kartoffeln, and cranberry jam… with a

gallantry that did honour to his nation.»

The

German words are italicized to show their alien nature and at the

same time their stylistic function in the passage. These words have

not become facts of the English language and need special decoding to

be understood by the rank and file English-speaking reader.

In

this connection mention might be made of a stylistic device often

used by writers whose knowledge of the language and customs of the

country they depict bursts out from the texture of the narrative,

they

use

foreign words and phrases and sometimes whole sentences quite regard*

less of the fact that these may not be understood by the reader.

However, one suspects that the words are not intended to be

understood exactly. All that is required of the reader is that he

should be aware that the words used are foreign and mean something,

in the above case connected with food. In the above passage the

association of food is maintained throughout by the use of the

words ‘appetite’, ‘consumed’ and the English ‘cranberry jam’. The

context therefore leads the reader to understand that schinken,

braien and kartoffeln are words denoting some kind of food, but

exactly what kind he will learn when he travels in Germany.

The

function of the foreign words used in the context may be considered

to provide local colour as a background to the narrative. In

passages of other kinds units of speech may be used which will

arouse only a vague conception in the mind of the reader. The

significance of such units, however, is not communicative — the

author does not wish them to convey any clear-cut idea — but to

serve in making the main idea stand out more conspicuously.

This

device may be likened to one used in painting by representatives

of the Dutch school who made their background almost

indistinguishable in order that the foreground elements might

stand out distinctly and colourfully.

An

example which is even more characteristic of the use of the local

colour function of foreign words is the following stanza from Byron’s

«Don Juan»:

…

more than poet’s pen

Can

point,— «Cos/ viaggino: ЩссЫГ

(Excuse

a foreign slip-slop now and then,

If

but to show I’ve travell’d: and what’s travel

Unless

it teaches one to quote and cavil?)

The

poet himself calls the foreign words he has used ‘slip-slop’, i. e.

twaddle, something nonsensical.

Another

function of barbarisms and foreign words is to build up the stylistic

device of non-personal direct speech or represented speech (see p.

236). The use of a word, or a phrase, or a sentence in the reported

speech of a local inhabitant helps to reproduce his actual words,

manner of speech and the environment as well. Thus in James

Aldridge’s «The Sea -Eagle» — «And the Cretans were

very willing to feed and hide the Inglisi»—, the last word is

intended to reproduce the actual speech of the local people by

introducing a word actually spt)ken by them, a word which is very

easily understood because of the root.

Generally

such words are first introduced in the direct speech of a character

and then appear in the author’s narrative as an element of reported

speech. Thus in the novel «The Sea Eagle» the word

‘benzina’ (=motor boat) is first mentioned in the direct speech of a

Cretan:

«It

was a warship that sent out its benzina to- catch us arid look for

guns.»

Later

the author uses the same word but already in reported speech:

«He

heard too the noise of a benzina engine starting.»

Barbarisms

and foreign words are used in various styles of language, but are

most often to be found in the style of belles-lettres and the

publi-cistic style. In the belles-lettres style, however, foreignisms

are sometimes used not only as separate units incorporated in the

English narrative. The author makes his character actually speak a

foreign language, by putting a string of foreign words into his

mouth, words which to many readers may be quite unfamiliar. These

phrases or whole sentences are sometimes translated by the writer in

a foot-note or by explaining the foreign utterance in English in the

text. But this is seldom done.

Here

is an example of the use of French by John Galsworthy:

«Revelation

was alighting like a bird in his heart, singing: «Elle est ton

revel Elle est ton revel» («In Chancery»)

No

translation is given, no interpretation. But something else must be

pointed out here. Foreign words and phrases may sometimes be used to

exalt the expression of the idea, to elevate the language. This is in

some respect akin to the function of elevation mentioned in the

chapter on archaisms. Words which we do not quite understand

sometimes have a peculiar charm. This magic quality in words, a

quality not easily grasped, has long been observed and made use of in

various kinds of utterances, particularly in poetry and

folklore.

But

the introduction of foreign speech into the texture of the English

language hinders understanding and if constantly used becomes

irritating. It may be likened, in some respect, to jargon. Soames

Forsyte, for example, calls it exactly that.

«Epatantt»

he heard one say. «Jargon!» growled Soames to himself.

The

introduction’of actual foreign words in an utterance is not, to our

mind, a special stylistic device, inasmuch as it is not a conscious

and intentional literary use of «the’facts of the English

language. However, foreign words, being alien to the texture of

the language in which the work is written, always arrest the

attention of the reader and therefore have a definite

stylistic^function. Sometimes the skilful use of one or two foreign

wordsvwill be sufficient to create the impression of an utterance

made in a foreign language. Thus in the following example:

«Deutsche

Soldaten ~^a little while agd, you received a sample of American

strength’.» (Stefan Heym, «The Crusaders»)

The

two words ‘Deutsche Soldaten’ are sufficient to create the

impression that the actual speech was made in German, as in real

life it would have been.

The

same effect is sometimes achieved by the slight distortion of an

English word, or a distortion of English grammar in such a way that

the morphological aspect of the distortion will bear a resemblance to

the morphology of the foreign tongue, for example:

«He

look at Miss Forsyte so funny sometimes. I tell him all my story; he

so-sympatisch.» (Galsworthy)

Barbarisms

have still another function when used in the belles-lettres style. We

may call it an «exactifying» function. Words of for-seign

origin generally have a more or less monosemantic value. In other

words, they do not tend to develop new meanings. The English So long,

for example, due to its conventional usage has lost its primary

meaning. It has become a formal phrase of parting. Not so with the

French «Au-revoir.» When used in English as a formal sign

of parting it will either carry the exact meaning of the words it is

composed of, viz. ‘See you again soon’, or have another stylistic

function. Here is an example:

«She

had said *Au revoirV Not good-bye!» (Galsworthy)

The

formal and conventional salutation at parting has become a meaningful

sentence set against another formal salutation at parting which, in

its turn, is revived by the process to its former significance of

«God be with you,» i. e. a salutation used when parting for

some time.

In

publicistic style the use of barbarisms and foreign words is mainly

confined to colouring the passage on the problem in question with &

touch of authority. A person who uses so many foreign words and

phrases is obviously a very educated person, the reader thinks, and

therefore a «man who knows.» Here are some examples of the

use of barbarisms in the publicistic style:

«Yet

en passant I would like to ask here (and answer) what did Rockefeller

think of Labour…» (Dreiser, «Essays and Articles»)

«Civilization»

— as they knew it — still depended upon making profits ad

infinitum» (Ibid.)

We

may remark in passing that Dreiser was particularly fond of using

barbarisms not only in his essays and articles but in his novels and

stories as well. And this brings us to another question. Is the use

of barbarisms and foreign words a matter of individual preference of

expression, a certain idiosyncrasy of this or that writer? Or is

there a definite norm regulating the usage of this means of

expression in different styles of speech? The reader is invited

to make his own observations and inferences on the matter.

Barbarisms

assume the significance of a stylistic device if they display a kind

of interaction between different meanings, or functions, or aspects.

When a word which we consider a barbarism is used so as to evoke a

twofold application we are confronted with an SD.

In

the example given above — «She had said ‘au revoirV Not

goodbye!» the ‘au revoir’ will be understood by the reader

because of its frequent use in some circles of English society.

However, it is to be understood literally here, i. e. ‘So long’ or

‘until we see each other again.’ The twofold perception secures the

desired effect. Set against the English ‘Good-bye’ which is generally

used when, people part for an

indefinite

time, the barbarism loses its formal character and re-establishes

its etymological meaning. Consequently, here again we see the clearly

cut twofold application of the language unit, the indispensable

requirement for a stylistic device.

Author:

Louise Ward

Date Of Creation:

4 February 2021

Update Date:

12 April 2023

Content

- What is a barbarism?

- Types of barbarism

- References:

We explain what a barbarism is in language and various examples. Also, what types exist and the characteristics of each one.

What is a barbarism?

We call those barbarisms mistakes or inaccuracies when pronouncing or writing a word or phrase, or when using certain foreign words (foreign words) not yet incorporated into the language itself. It is a type of linguistic error that is very common in colloquial and popular speech, but which from the point of view of the language norm is considered a sign of a lack of culture or education.

The term barbarism comes from the word barbarian, coined in Ancient Greece to refer to the Persians, their eternal rivals, whose language was incomprehensible to the Greeks.

The Greeks scoffed through onomatopoeia «Pub, Pub”Because that was how the entire Persian language sounded to them. Over time they created «barbarian» (barbaroi) as a derogatory way of referring not only to them, but to all foreigners who they considered politically and socially inferior, that is, to “people who speak ill”.

The term was inherited into the language of the Romans (barbarus) and used in a similar way during its imperial times, to refer to neighboring peoples who did not speak Latin.

That is why the term barbarism It can also be used as a synonym for barbarism or barbarity: a violent act or saying, brutal, uncivilized. Perhaps remembering that the Roman Empire, precisely, ended up falling to the invasions of those peoples who were branded as barbarians.

Today, however, we understand barbarisms as a phenomenon of speech and writing of the same language, when they contradict its syntactic or grammatical order, that is, its ideal norms.

However, it is not always possible to easily distinguish barbarisms from neologisms (new contributions to the language) or from foreign words (borrowings from other languages). So, many barbarisms end up being accepted and incorporated into the language.

Types of barbarism

There are three different types of barbarism, depending on the aspect of the language in which the error occurs: prosodic (sound), morphological (form) or syntactic (order). Let’s see each one separately:

Prosodic barbarisms

They take place when they occur alterations or inaccuracies in the way of pronouncing or articulating the sounds of the tongue. Mispronunciation often responds to criteria of the economy of the language, that is, to the least possible effort in pronunciation; other times, to simple vice.

That is why they must be differentiated from the dialect variants of the same language, since a language is not always pronounced the same in all its speaking communities.

Examples of prosodic barbarisms in Spanish are:

- Pronounce the «g” as if it were «and”, imitating the loudness of other languages: yir instead of spinning.

- Do not pronounce certain intermediate consonants: go for you went, criminal per offender.

- Pronounce an «s” at the end of second person verbs: you ate for you ate, you arrived instead of you came.

- To pronounce syndrome instead of syndrome.

- To pronounce tasi instead of taxi.

- To pronounce aigre instead of air.

- To pronounce captus instead of cactus.

- To pronounce bisted instead of steak.

- To pronounce insepto instead of insect.

- To pronounce you came instead of you came.

- To pronounce gummy instead of vomiting.

Morphological barbarisms

Take place when the alteration occurs in the very construction of a word, both at the level of its spelling and its pronunciation. This is why they are also often considered misspellings, and often lead to the erroneous creation of non-existent words.

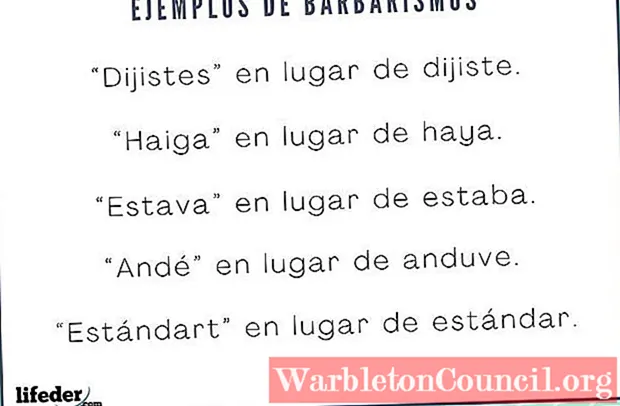

Examples of morphological barbarisms in Spanish are:

- The use of open instead of opening.

- The use of downloada instead of downloading.

- The use of American instead of American.

- The use of cape instead of fit, from the verb fit.

- The use of i walked instead of walked, of the verb to walk.

- The use of i drove instead of of I drove, of the verb to drive.

- The use of estuata instead of statue.

- The use of strict instead of strict.

- The use of haiga instead of beech.

- The use of died instead of dead.

- The use of sofales instead of sofas.

- The use of I know or sepo instead of I know.

Syntactic barbarisms

Take place when the alteration occurs in the order of the terms of a sentence, or in the concordance of them (in terms of gender, number, etc.).

Examples of syntactic barbarisms in Spanish are:

- The use of the phrase «roughly«, When it would have to be»roughly”.

- The use of «the first» instead of «the first».

- The use of «more better» or «more worse» instead of «better» and «worse».

- The use of “de que” where “that” corresponds (dequeísmo), as in: she told me about what… or I think about what…

- The use of “that” where it corresponds “of that” (queísmo), as in: we realize that … orWhat were you two talking about?

- The use of «in relation to» instead of «in relation to» or «in relation to».

- The personalization of the verb haber, as in: there are people who … or there were thousands of homicides.

Continue with: Arcaísmos

References:

- «Barbarism» in Wikipedia.

- «Barbarism» in the Dictionary of the language of the Royal Spanish Academy.

- «Do you know what a barbarism is?» (video) in Grammar to the day of Utec El Salvador.

- «The barbarisms of every day: how do you say it?» in TN (Argentina).

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

Barbarisms are words of foreign origin which have not entirely been assimilated into the English language. They bear the appearance of a borrowing and are felt as something alien to the native tongue. The great majority of the borrowed words now form part of the rank and file of the English vocabulary. There are some words which retain their foreign appearance to greater or lesser degree. These words, which are called barbarisms, are also considered to be on the outskirts of the literary language. Most of them have corresponding English synonyms. Barbarisms are not made conspicuous in the text unless they bear a special load of stylistic information.

It is very important for purely stylistic purposes to distinguish between barbarisms and foreign words proper. Foreign words do not belong to the English vocabulary. In printed works foreign words and phrases are generally italicized to indicate their alien nature or their stylistic value. There are foreign words which fulfill a terminological function. Many foreign words and phrases have little by little entered the class of words named barbarisms and many of these barbarisms have gradually lost their foreign peculiarities, become more or less naturalized and have merged with the native English stock of words.

Both foreign words and barbarisms are widely used in various style of language with various aims, aims which predetermine their typical functions. One of these functions is to supply local color. In order to depict local conditions of life, concrete facts and events, customs and habits, special care is taken to introduce into the passage such language elements as will reflect the environment. In this respect a most conspicuous role is played by the language chosen.

The function of the foreign words used in the context may be considered to provide local color as a background to the narrative. In passages of other kinds units of speech may be used which will arouse only a vague conception in the mind of the reader. The significance of such units, however, is not communicative — the author does not wish them to convey any clear-cut idea — but to serve in making the main idea stand out more conspicuously. This device may be likened to one used in painting by representatives of the Dutch school who made their background almost indistinguishable in order that the foreground elements might stand out distinctly and colorfully.

Another function of barbarisms and foreign words is to build up the stylistic device of non-personal direct speech or represented speech (see p. 236). The use of a word, or a phrase, or a sentence in the reported speech of a local inhabitant helps to reproduce his actual words, manner of speech and the environment as well. Thus in James Aldridge’s “The Sea Eagle” — “And the Cretans were very willing to feed and hide the Ingllsi’’—, the last word is intended to reproduce the actual speech of the local people by introducing a word actually spoken by them, a word which is very easily understood because of the root. Generally such words are first introduced in the direct speech of a character and then appear in the author’s narrative as an element of reported speech.

Barbarisms and foreign words are used in various styles of language, but are most often to be found in the style of belles-lettres and the publicistic style. In the belles-lettres style, however, foreignisms are sometimes used not only as separate units incorporated in the English narrative. The author makes his character actually speak a foreign language, by putting a string of foreign words into his mouth, words which to many readers may be quite unfamiliar. These phrases or whole sentences are sometimes translated by the writer in a foot-note or by explaining the foreign utterance in English in the text. But this is seldom done.

Foreign words and phrases may sometimes be used to exalt the expression of the idea, to elevate the language. Words that we do not quite understand sometimes have a peculiar charm. This magic quality in words, a quality not easily grasped, has long been observed and made use of in various kinds of utterances, particularly in poetry and folklore. But the introduction of foreign speech into the texture of the English language hinders understanding and if constantly used becomes irritating. It may be likened, in some respect, to jargon.

The introduction of actual foreign words in an utterance is not, to our mind, a special stylistic device, inasmuch as it is not a conscious and intentional, literary use of the facts of the English language. However, foreign words, being alien to the texture of the language in which the work is written, always arrest the attention of the reader and therefore have a definite stylistic function. Sometimes the skilful use of one or two foreign words will be sufficient to create the impression of an utterance made in a foreign language.

Barbarisms assume the significance of a stylistic device if they display a kind of interaction between different meanings, or functions, or aspects. When a word which we consider a barbarism is used so as to evoke a twofold application we are confronted with an SD.

The main function of barbarisms and foreignisms is to create a realistic background to the stories about foreign habits, customs, traditions and conditions of life.

List of references:

Galperin I. R. English Stylistics. Москва, 2014

Арнольд И.В. Стилистика современного английского языка. «Флинта», 2002

Гуревич В.В. English stylistics. Стилистика английского языка, 2017

Разинкина Н.М. Функциональная стилистика английского языка. — М.: Высшая школа, 1989.

Content

- Types of barbarism

- Phonetic barbarisms

- Confusion for consonants with similar phonemes

- Misuse of prefixes

- Prosodic barbarisms

- Confusion with the use of the interspersed letter «h»

- Syntactic barbarisms

- Spelling barbarisms

- Foreigners

- References

The barbarism they are words or terms used without taking into account the rules that a language has. Consequently, they are words used inappropriately in oral and written communication. They are very common in speakers with little academic training and are frequent in colloquial speech.

The word «barbarism» derives from Latin barbarismus (which means «foreigner»). This term was used to indicate the difficulties experienced by newcomers to a region when speaking the local language. In fact, any outsider (both anciently and today) can easily confuse similar words.

There are various causes that originate new barbarisms. Among them: bad habit during childhood, failures in the conjugation of irregular verbs and errors in the construction of plural words.

Types of barbarism

Phonetic barbarisms

-

Confusion for consonants with similar phonemes

It occurs when consonants with very similar phonemes are incorrectly pronounced or written. The most recurrent cases are related to the confusion between the letters “B” and “V”, between “J” and “G” or “X” and “S”. Similarly, it happens with the letters: «G» — «Y», «N» — «M», «X» — «C» (or «P»), and «B» — «D».

Similarly, phonetic barbarisms appear in some linguistic studies or articles as part of spelling barbarisms. Examples:

— The confusion between “bouncing” (bouncing, throwing, discarding…) and “voting” (voting, nominating or electing).

— «Estava» instead of I was.

— «Indíjena» instead of indigenous.

— «Foreigner» instead of Foreign.

— «Stranger» instead of strange.

— “Pixcina” instead of pool.

— «Inpulso» instead of impulse. In this case, the spelling rule about the mandatory placement of the letter «m» before «p» is ignored.

— «Enpecinado» instead of stubborn.

— “Enpanada” instead of Patty.

— «Inprovisation» instead of improvisation.

— «Entrepreneur» instead of entrepreneur.

— «Colunpio» instead of swing.

— “Valla” (written like this it refers to an advertisement) instead of go (from the verb to go).

— «Exited» instead of excited.

— «Skeptic» instead of skeptical.

-

Misuse of prefixes

This type of barbarism is very common in prefixes such as «sub» or «trans». Well, it is easy to add or remove the letter «s» in an inappropriate way. In some cases, even that simple modification can completely change the meaning of a sentence. For example:

— «Transported» to replace transported.

— «Unrealistic» to replace surreal.

«-Dispatch» to replace disorder.

Prosodic barbarisms

They are those barbarisms that occur due to diction problems or in the pronunciation of sounds. The latter can occur by omission, substitution or addition of letters. Some of the most common prosodic barbarisms are described below:

— «Pull» instead of pull.

— «Llendo» or «going» instead of going (from the verb to go).

— «Insepto» instead of insect.

— «Madrasta» instead of stepmother.

— «Haiga» instead of be there.

— «Topical» instead of toxic.

— «Trompezar» instead of trip on.

— «Nadien» instead of no one.

— «Ocjeto» instead of object.

— “Preveer” instead of foresee (synonymous with anticipating, predicting or forecasting). In this case there could be a confusion with the verb provide.

— «Benefit» instead of charity. In this case the error could derive from the resemblance to the word science, however, the word derives from the verb benefit.

-

Confusion with the use of the interspersed letter «h»

Some academics place this type of barbarism as orthographic and not prosodic in nature. Even in other sources, prosodic barbarisms appear as one of the types of spelling barbarisms. In any case, confusion with the interleaved letter “h” is almost always due to the lack of vocabulary on the part of the writer or speaker.

To avoid this error, it is advisable to look at the etymological root of the word (especially if it is a verb). For example:

— “Exume” instead of exhume. The root of the word derives from Latin humus, means «land.»

— «Exalar» instead of exhale.

— «Lush» instead of exuberant.

— «Show» instead of to exhibit.

— «Inibir» instead of inhibit.

— «Exort» instead of exhort (synonym of persuading or inciting).

Syntactic barbarisms

This type of barbarism occurs when there are errors of concordance, use of idioms or a faulty construction of sentences. They are also produced by the so-called “queísmo” or “dequeísmo”, especially when they substitute personal pronouns or the recommended connectives. As well as the misuse of impersonal.

For example:

— The expression “please come before it rains” is incorrect, the correct form is “please come before of what rain ”.

— «There were few seats» is an incorrect sentence. Should be «there were few seats (inappropriate use of impersonal).

— In the sentence «the one who came after you» occurs an incorrect substitution of the pronoun, it should be «who came after you».

— The expression «in relation to» is a syntactic barbarism, the proper form is «regarding«Or»in relation to”.

— Use the word «American» to refer to a American.

— «You said» instead of said.

— «You went» instead of you were.

Spelling barbarisms

They refer to errors in the form and structure (pronounced or written) of words. For example: say «airport» instead of airport or «monster» instead of monster, are two of the most common. In these two specific cases, they are also called «morphological barbarisms.»

— «Question» (without accent; as an acute word does not exist in Spanish, it would be correct in English) instead of question.

— «Excuse» instead of excuse.

— “Idiosyncrasy” to replace idiosyncrasy.

— «Decomposed» instead of decomposed.

— «Andé» instead of i walked.

Foreigners

In today’s digital age, it is common to use terms derived from English. Mainly, it is an error favored by the appearance of digital devices and a specific lexicon for technologies. Given this situation, the RAE recommends the use of words with accepted words in Spanish.

This peculiarity is noticeable in the newly included word «selfie.» Well, if it is going to be written in English (the writing rule indicates that) it must be italicized, that is, selfie. Other examples:

— «Sponsor» (Anglicism) instead of sponsor.

— “Standard” or “standard” instead of standard.

— “Football” is a word in English, in Spanish the correct thing is football.

References

- (2020). Spain: Wikipedia. Recovered from: es.wikipedia.org.

- Igea, J. (2001). Allergist style manual (II). The barbarisms. Spain: Spanish Journal of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Recovered from: researchgate.net.

- Language Vices, module II. (S / f.). (N / A): INAGEP. Recovered from: normativayortografia.jimdo.com

- Tabuenca, E. (S / f.). (N / A): Barbarisms: definition and examples. Recovered from: unprofesor.com

- The 25 most frequent barbarisms in Spanish and among students. (2019). (N / A): Magisterium. Recovered from: magisnet.com.

Author:

John Pratt

Date Of Creation:

13 April 2021

Update Date:

10 April 2023

Content

- What is a Barbarism:

- Types of barbarisms

- Prosodic barbarisms

- Syntactic barbarisms

- Spelling barbarisms

As barbarisms we call all those linguistic mistakes we make when we make mistakes when writing or pronouncing a word.

The voice, as such, comes from Latin barbarismus, which in turn comes from the Greek βαρβαρισμός (barbarisms). This term comes from βάρβαρος (barbarians), the way foreigners were designated in ancient Greece, who had difficulties speaking the local language.

Thus, then, all those words, expressions or syntactic constructions that do not conform to the grammatical rules of the language, since they add, omit or transpose letters, sounds or accents.

The word barbarism can also be used as synonym of barbarity, that is, words or actions that, due to their impropriety or recklessness, are impertinent. For example: «Enough of barbarism: let’s speak sensibly.»

Barbarism, likewise, is used with the sense of barbarism, lack of culture or rudeness: «Barbarism entered the Congress of the Republic with that deputy.»

Types of barbarisms

There are different types of barbarism depending on the type of impropriety they imply. They can be prosodic, syntactic or orthographic.

Prosodic barbarisms

Prosodic barbarisms are those in which vices are committed in diction or improprieties in the way of articulating certain sounds.

For example:

- Going or going by going, from the verb go.

- Pull for pull.

- Inspt by insect.

- Foresee to foresee.

- Haiga por beech.

Syntactic barbarisms

Syntactic barbarisms are those in which the agreement, the regime or the construction of words, sentences or idioms is corrupted.

For example:

- In relation to instead of in relation to or in relation to.

- Queísmos: «Call before you come», instead of «call before you come.»

- Dequeísmos: «I think it is not good», for «I think it is not good».

- Impersonal sentences: «Yesterday it reached 30 degrees», instead of «yesterday it reached 30 degrees.»

Spelling barbarisms

Spelling barbarisms are those that imply failures to the norm of the correct writing and formation of the words. It occurs not only with words from one’s own language, but also with foreign words not adapted to grammatical norms.

For example:

- I walked by walked, from the verb walk.

- You said for you said, from the verb to say.

- Decomposed by decomposed, from the verb decompose.

- Monster by monster.

- I was for I was, from the verb to be.

- Restaurant by restaurant.

- Boucher by voucher.

- Bulling, bulyng, buling, bulin or bulyn by bullying.