What is an adjective?

An adjective is a word that describes something (a noun).

An adjective gives us more information about a person or thing.

Correct order of adjectives

Adjectives sometimes appear after the verb To Be (CARD – LINK TO VIDEO)

The order is To Be + Adjective.

- He is tall.

- She is happy.

Adjectives sometimes appear before a noun.

The order is Adjective + Noun.

- Slow car

- Brown hat

BUT… Sometimes you want to use more than one adjective to describe something (or someone).

What happens if a hat is both brown AND old?

Do we say… an old brown hat OR a brown old hat?

An old brown hat is correct because a certain order for adjectives is expected.

A brown old hat sounds incorrect or not natural.

So what is the correct order of adjectives before a noun?

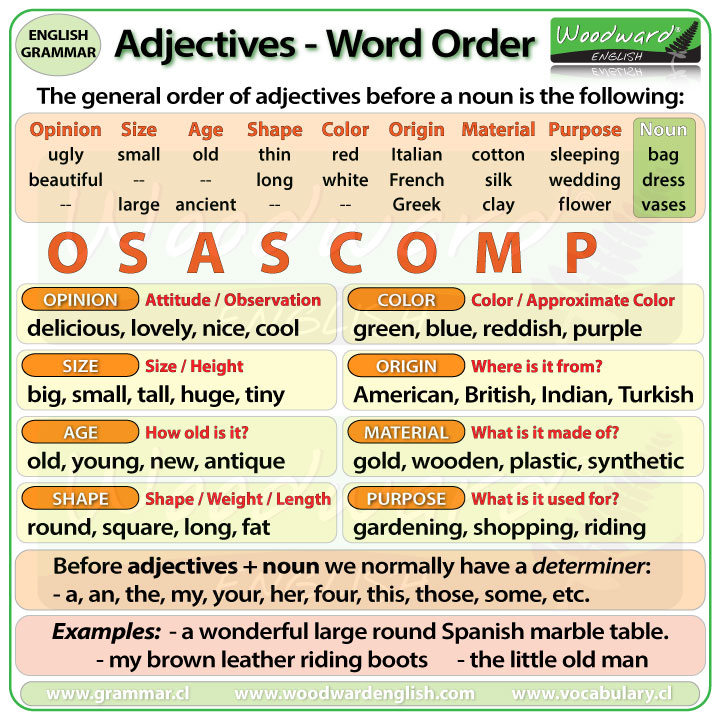

The order of adjectives before a noun is usually the following:

Opinion – Size – Age – Shape – Color – Origin – Material – Purpose

If we take the first letter of each one, it creates OSASCOMP which is an easy way to remember the order.

Let’s look at an example about describing a bag.

- It is an ugly small old thin red Italian cotton sleeping bag

It is not common to have so many adjectives before a noun, but I do this so you can see the correct order of adjectives.

Ugly is an opinion, small is a size, old refers to age, thin refers to shape, red is a color, Italian refers to its origin, cotton refers to the material the bag is made of, sleeping is the purpose of the bag.

I will go into more details about each of these categories in a moment. First, let’s see two more examples:

- A beautiful long white French silk wedding dress.

- Large ancient Greek clay flower vases.

Let’s study the first one.

Here we have a dress. Dress is a noun, the name of a thing. Let’s describe this dress.

What type of dress is it? What is the purpose of this dress?

It is used for weddings so it is…

- a wedding dress.

Let’s image the dress is made of silk. It isn’t made of plastic or gold, it is made of silk.

Silk is a material so it goes before the purpose. We say it is:

- a silk wedding dress.

Now, this dress was made in France. France is a noun, its adjective is French.

Its origin is French. Its origin, French, goes before the material, Silk. So we say it is:

- a French silk wedding dress.

Let’s add the color of the dress. What color is it? White. Color goes before Origin so we say it is:

- a white French silk wedding dress.

What is the shape of this dress? Is it long or short? It is long. The adjective Long goes under the category of shape because shape also covers weight or length. (We will see more about this in a moment) We now say it is:

- a long white French silk wedding dress.

Let’s add one more adjective. Is the dress beautiful or ugly? Well, you should always say it is beautiful or it will ruin her wedding day.

Beautiful is an opinion and adjectives about opinions go before all the other adjectives. So our final description of the dress is:

- a beautiful long white French silk wedding dress.

Now of course we don’t normally add so many adjectives before a noun. This example is just to show you the order of adjectives.

The order is NOT fixed

IMPORTANT: The order of adjectives before a noun is NOT 100% FIXED.

This chart is only a guide and is the order that is preferred.

You may see or hear slight variations of the order of adjectives in real life though what appears in the chart is the order that is expected the most.

Now, let’s look at each type of adjective in more detail (with examples)…

Types of Adjectives

OPINION

Opinion: These adjectives explain what we think about something. This is our opinion, attitude or observations that we make. Some people may not agree with you because their opinion may be different. These adjectives almost always come before all other adjectives.

Some examples of adjectives referring to opinion are:

- delicious, lovely, nice, cool, pretty, comfortable, difficult

For example: She is sitting in a comfortable green armchair.

Comfortable is my opinion or observation, the armchair looks comfortable. The armchair is also green.

Here we have two adjectives. The order is comfortable green armchair because Opinion (comfortable) is before Color (green).

SIZE

Size: Adjectives about size tell us how big or small something is.

Some examples of adjectives referring to size are:

- big, small, tall, huge, tiny, large, enormous

For example: a big fat red monster.

Notice how big is first because it refers to size and fat is next because it refers to shape or weight. Then finally we have the color red before the noun.

AGE

Age: Adjectives of age tell us how old someone or something is. How old is it?

Some examples of adjectives referring to age are:

- old, young, new, antique, ancient

For example: a scary old house

Scary is my opinion, old refers to the age of the house. Scary is before old because opinion is before age.

SHAPE

Shape: Also weight and length. These adjectives tell us about the shape of something or how long or short it is. It can also refer to the weight of someone or something.

Some examples of adjectives referring to shape are:

- round, square, long, fat, heavy, oval, skinny, straight

For example: a small round table.

What is the shape of the table? It is round.

What is the size of the table? It is small.

The order is small round table because size is before shape.

COLOR

Color: The color or approximate color of something.

Some examples of adjectives referring to color are:

- green, blue, reddish, purple, pink, orange, red, black, white

(adding ISH at the end makes the color an approximate color, in this case reddish is “approximately red”)

Our example: a long yellow dress.

What is the color of the dress? It is yellow.

The dress is also long. Long which is an adjective of shape or more precisely length, is before an adjective of color.

ORIGIN

Origin: Tells us where something is from or was created.

Some examples of adjectives referring to origin are:

- American, British, Indian, Turkish, Chilean, Australian, Brazilian

Remember, nationalities and places of origin start with a capital letter.

For example: an ancient Egyptian boy.

His origin is Egyptian. Egyptian needs to be with a capital E which is the big E.

Ancient refers to age so it goes before the adjective of origin.

MATERIAL

Material: What is the thing made of or what is it constructed of?

Some examples of adjectives referring to material are:

- gold, wooden, plastic, synthetic, silk, paper, cotton, silver

For example: a beautiful pearl necklace

Pearl is a material. They generally come from oysters.

The necklace is made of what material? It is made of pearls.

The necklace is also beautiful so I put this adjective of opinion before the adjective referring to material.

PURPOSE

Purpose: What is it used for? What is the purpose or use of this thing? Many of these adjectives end in

–ING but not always.

Some examples of adjectives referring to purpose are:

- gardening (as in gardening gloves), shopping (as in shopping bag), riding (as in riding boots)

Our example: a messy computer desk

What is the purpose of the desk? It is a place for my computer, it is designed specifically to use with a computer. It is a computer desk. In this case, the desk is also very messy. Messy is an opinion. Some people think my desk is messy. So, the order is opinion before purpose.

So this is the general order of adjectives in English and you can remember them by the mnemonic OSASCOMP.

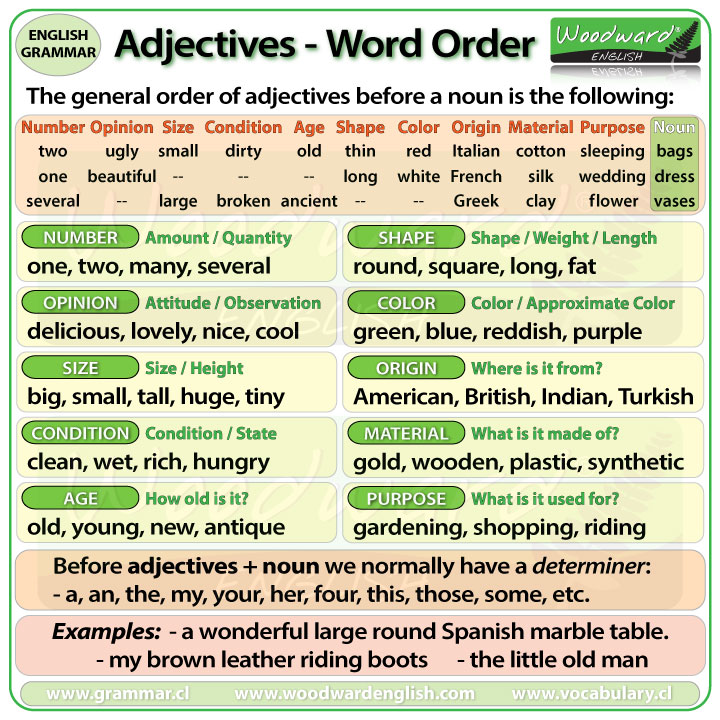

BUT did you know that we could add some extra categories?

BONUS ADJECTIVE GROUPS

We can add the adjective categories of Number and Condition.

NUMBER

Number: Tells us the amount or quantity of something.

It is not only for normal cardinal numbers like, one, two, three… but also other words that refer to quantity such as many or several.

Our examples of adjectives referring to numbers are:

- One, two, three, many, several

For example: three hungry dogs

Number adjectives go before all the other adjectives, including adjectives about opinion.

Hungry is a condition or state so the order is Three hungry dogs.

CONDITION

Condition: Tells us the general condition or state of something

Our examples of adjectives referring to condition or state are:

- Clean, wet, rich, hungry, broken, cold, hot, dirty

For example: Two smelly old shoes.

Smelly is a condition or state. Smelly is before old which refers to age. The number two is at the beginning as numbers always are.

Adjectives – Word Order – Summary Chart

Adjectives Word Order – Practice Quiz

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

In addition, a certain word order allows the interlocutor to understand what type of sentence is being discussed: affirmative, negative, interrogative, imperative or exclamatory. To figure it out, let’s remember what the members of the proposal are.

A characteristic feature of sentences in English is a firm word order. Solid word order is of great importance in modern English, because, due to the poorly represented morphological system in the language, the members of the sentence are often distinguished only by their place in the sentence.

The direct word order in an English sentence is as follows: the subject is in the first place, the predicate is in the second, and the complement is in the third. In some cases, the circumstance may come first. In an English sentence, an auxiliary verb may appear in the main verb.

What is the word order in the English interrogative sentence?

In the first place the necessary QUESTIONAL WORD is put, in the second — the FAVORABLE, in the third place — the SUBJECT, in the fourth place are the SECONDARY members of the sentence.

What is the word order in an English declarative sentence?

A characteristic and distinctive feature of declarative affirmative sentences in English is the observance of a firm (direct) word order. This means that in the first place in a sentence the subject is usually put, in the second place — the predicate, in the third place — the addition and then the circumstances.

Why is direct word order in English?

In grammar, it is customary to distinguish two types of word order: Direct Order, which is used in declarative (affirmative and negative) sentences, and Indirect Order, which helps to ask a question, express an exclamation, or even give an order.

What order are adjectives in English?

The order of adjectives in English

- Article or other qualifier (a, the, his)

- Rating, opinion (good, bad, terrible, nice)

- Size (large, little, tiny)

- Age (new, young, old)

- Shape (square, round)

- Color (red, yellow, green)

- Origin (French, lunar, American, eastern, Greek)

How to build sentences correctly?

The subject is usually placed before the predicate. The agreed definition is before the word being defined, the circumstance of the mode of action is before the predicate, and the rest of the circumstances and addition are after the predicate. This word order is called direct. In speech, the specified order of the members of the sentence is often violated.

How many words are there in English?

Let’s try to find out the number of words in English by looking in the dictionary: The second edition of the 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary contains 171 words currently in use, and 476 obsolete words. To this can be added about 47 derivative words.

How to determine what time a sentence is in English?

The tense in an English sentence is determined by the verb. Note, not by additional words, but by the predicate verb.

How to construct an interrogative sentence in English correctly?

The special question uses interrogative words. They are what, where, when, whose, (when), how, why, and so on. The interrogative word is placed at the beginning of the sentence, followed by the verb (or auxiliary verb), the subjects — and then the rest of the sentence.

How to make negative sentences in English?

To make sentences negative, you must put the word «not» after the modal verb. For example, we have an affirmative sentence: He can swim. He can swim.

What is the word order in an affirmative sentence?

In an affirmative sentence, the subject is in the first place, the predicate is in the second place, and the secondary members of the sentence are in the third place.

What is a big word order sentence?

In direct word order, the subject precedes the predicate, i.e. comes first. In the reverse order of words, the subject is placed immediately after the predicate (its conjugated part).

What is a narrative sentence example?

A narrative sentence is used by the speaker to inform about some facts, phenomena of reality, about their thoughts, experiences and feelings, etc. May beetles whirled over the birches. A frog croaked at the shore.

What are the tenses in English?

There are also three English tenses — present, past and future, but depending on whether the action is complete or prolonged, each of these tenses can be of four types — simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous.

The

words in an English sentence are arranged in a certain order which is

fixed for every type of sentence and is, therefore, meaningful. There

exist two ways of arranging words—direct order and inverted order.

Word

order fulfils various functions. The two main functions of word order

are grammatical and communicative. The essence of the grammatical

principle lies in the fact that the sentence position of an element

is determined by its syntactic function. The

communicative

principle manifests itself in that the sentence position of an

element varies depending on its communicative value.

Direct

word Order

The

most common pattern for the arrangement of the main parts in a

declarative sentence is Subject-Predicate-(Object), which is called

direct word order.

I

promise to respect your wishes.

Direct

word order is also employed in pronominal questions to the subject or

its attribute.

Who

told you where I was?

Direct

word order allows of a few variations in the fixed pattern, but only

for the secondary parts.

End—Focus

and End-Weight

Inappropriate

word order may lead to incoherence, clumsy style and lack of clarity.

So when you are deciding in which order to place the ideas in a

sentence, there are two useful guiding principles to remember:

-

End-focus:

the new or most important idea in a piece of information should be

placed towards the end, where in speech nuclear stress normally

falls. A sentence is generally more effective (especially in

writing) if the main point is saved up to the end.

Babies

prefer sleeping on their back.

-

End-weight:

the more “weighty” part(s) of a sentence should be placed

towards the end. Otherwise the sentence may sound awkward and

unbalanced. The “weight” of an element can be defined in terms

of length(e.g. number of syllables) or in terms of grammatical

complexity (number of modifiers). Structures with introductory it

and there, for instance, allow to avoid having a long subject, and

to put what you are taking about in a more prominent position at the

end of the sentence.

It

becomes hard for a child to develop a sense of identity. There is

grief in his face and reproach at the injustice of it all.

Connected

with the principle of end-weight in English is the feeling that the

predicate of a sentence should be longer or grammatically more

complex than the subject. This helps to explain why English native

speakers tend to avoid predicates consisting of just a single

intransitive verb. Instead of saying Mary sang , they would probably

prefer to say Mary sang a song , filling the object position with a

noun phrase which adds little information but helps to give more

weight to the predicate.

For

such a purpose English often uses a general verb( such as have, take,

give and do ) followed by an abstract noun phrase:

He

is having a swim.—-He is swimming.

He

took a rest.——He rested.

He

does little work.—-He works little.

The

sentences on the left are more idiomatic than on the right and they

contribute to the impression of fluency in English given by a foreign

user.

Order

and Emphasis

English

grammar has quite a number of sentence processes which help to

arrange the message for the right order and the right emphasis.

Because of the principle of end-focus and end- weight, the final

position in a sentence or clause is, in neutral circumstances, the

most important.

But

the first position is also important for communication, because it is

the starting point for what the speaker wants to say: it is (so to

speak) the part of the sentence which is familiar territory in which

the hearer gets his bearings. Therefore the first element in a

sentence or clause is called the TOPIC (or THEME). In most

statements, the topic is the subject of the sentence.

Instead

of the subject, you may make another element the topic by moving it

to the front of the sentence( fronted topic). This shift, which is

called fronting, gives the element a kind of psychological

prominence, and has three different effects:

-

In

informal conversation it is quite common for a speaker to front an

element(particularly a complement) and give it nuclear stress:

An

utter fool I felt, too. (topic-complement).

Excellent

food the serve here. (topic-object).

-

Fronting

also helps to point dramatically to a contrast between two things

mentioned in the neighbouring sentences or clauses, which often have

parallel structure:

Rich

I may be, but that doesn’t mean I am happy. (topic-complement).

His

face I am not fond of, but his character I despise.(topic-object)

Willingly

he’ll never do it, he’ll have to be forced. (topic-adverbial of

manner)

-

The

word this or these is often present in the fronted topic, showing

that it contains given information. This type of fronting is found

in more formal, especially written English and serves the function

of linking the sentence to the previous text.

This

subject we have examined in an earlier chapter, and need not

reconsider (topic-object)

Besides

fronting there are other ways of giving prominence to this or that

part of the sentence.

*cleft

sentences (it-type)

The

cleft sentence construction with emphatic it is useful for putting

focus (usually for contrast)on a particular part of a sentence

expressed by a noun (group) ,a prepositional phrase, and an adverb of

time or place, or even by a clause.

It

was from France that she first heard the news.

Perhaps

it’s because he’s a misfit that I get along with him.

*cleft

sentences(wh-type)

What

he’s done is –spoil the whole thing.

—to

spoil the whole thing.

—spoilt

the whole thing.

Wh-clefts

can also be used to highlight a subject complement. Instead of Jean

and Bob are stingy, we can say: What Jean and Bob are is stingy! This

pattern is used when we want to express our opinion of something or

somebody.

What

we want is to see the child in pursuit of knowledge, and not

knowledge in pursuit of the child. (G.B.Shaw)

*Wh-clauses

with demonstratives

It

is a common type of sentence in English which is similar to wh-cleft

sentences.

This

is how you start the engine.

*Auxiliary

DO

You

can emphasize a statement by putting do, does , or did in front of

the base form of the verb.

I

do feel sorry for Roger.

But

it goes move.(G.Galilei).

*The

passive

Passive

constructions vary the way information is given in a sentence. The

passive can be used:

—for

end-focus

Who

makes these chairs?—They’re made by Ercol.

—for

end-weight where the subject is a clause

I

was astonished that he was prepared to give me a job. (Better than:

That he was prepared to give me a job astonished me.)

—for

emphasis on what comes first

All

roads to the north have been blocked by snow.

The

other common pattern of word order is the inversion. There are 2

types of inversion:

-

Subject-verb

inversion

Brightly

shone the moon that night…

-

Subject-operator/

auxiliary inversion

Seldom

can there have been such a happy meeting.

Sometimes

the inversion may be taken as a normal order of words in

constructions with special communicative value, and is devoid of any

special colouring.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #