This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

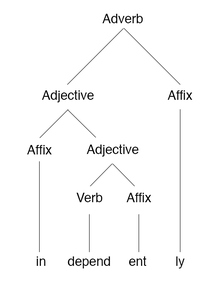

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

LECTURE 1

1.1.Lexicology as a branch of linguistics. Its interrelations with other sciences

1.2.The word as the fundamental object of lexicology. The morphological structure of the English word

1.3.Inner structure of the word composition. Word building. The morpheme and its types. Affixation

1.1.Lexicology as a branch of linguistics. Its interrelations with other sciences. Lexicology (from Gr lexis “word” and logos “learning”) is a part of linguistics dealing with the vocabulary of a language and the properties of words as the main units of the language. It also studies all kinds of semantic grouping and semantic relations: synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, semantic fields, etc.

In this connection, the term vocabulary is used to denote a system formed by the sum total of all the words and word equivalents that the language possesses. The term word denotes the basic unit of a given language resulting from the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment. A word therefore is at the same time a semantic, grammatical and phonological unit. So, the subject-matter of lexicology is the word, its morphemic structure, history and meaning.

There are several branches of lexicology. The general study of words and vocabulary, irrespective of the specific features of any particular language, is known as general lexicology. Linguistic phenomena and properties common to all languages are referred to as language universals. Special lexicology focuses on the description of the peculiarities in the vocabulary of a given language. A branch of study called contrastive lexicology provides a theoretical foundation on which the vocabularies of different languages can be compared and described, the correlation between the vocabularies of two or more languages being the scientific priority.

Vocabulary studies include such aspects of research as etymology, semasiology and onomasiology.

The evolution of a vocabulary forms the object of historical lexicology or etymology (from Gr. etymon “true, real”), discussing the origin of various words, their change and development, examining the linguistic and extra-linguistic forces that modify their structure, meaning and usage.

Semasiology (from Gr. semasia “signification”) is a branch of linguistics whose subject-matter is the study of word meaning and the classification of changes in the signification of words or forms, viewed as normal and vital factors of any linguistic development. It is the most relevant to polysemy and homonymy.

Onomasiology is the study of the principles and regularities of the signification of things / notions by lexical and lexico-phraseological means of a given language. It has its special value in studying dialects, bearing an obvious relevance to synonymity.

Descriptive lexicology deals with the vocabulary of a language at a given stage of its evolution. It studies the functions of words and their specific structure as a characteristic inherent in the system. In the English language the above science is oriented towards the English word and its morphological and semantic structures, researching the interdependence between these two aspects. These structures are identified and distinguished by contrasting the nature and arrangement of their elements.

Within the framework of lexicology, both synchronic (Gr syn “together”, “with” and chronos “time”) and diachronic or historical (Gr dia “through”) approaches to the language suggested by the Swiss philologist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) are effectively realized. Language is the reality of thought, and thought develops together with the development of a society, thus the language and its vocabulary should be studied in the light of social history. Every new phenomenon in a human society in general, which is of any importance for communication, finds a reflection in the corresponding vocabulary. A word is considered to be a generalized reflection of reality; therefore, it is impossible to understand its development if one is ignorant of the changes in socio-political or everyday life, manners and culture, science of a linguoculture it serves to reflect. These extra-linguistic forces influencing the evolution of words are taken into the priority consideration in modern lexicology.

With regard to special lexicology the synchronic approach is concerned with the vocabulary of a language as it exists at a certain time (e.g., a course in Modern English Lexicology). The diachronic approach in terms of special lexicology deals with the changes and the development of the vocabulary in the course of time. It is special historical lexicology that deals with the evolution of vocabulary units as time goes by.

The two approaches should not be contrasted, as they are interdependent since every linguistic structure and system actually exists in a state of constant development so that the synchronic state of a language system is a result of a long process of linguistic evolution.

As every word is a unity of semantic, phonetic and grammatical elements, the word is studied not only in lexicology, but in other branches of linguistics, too, lexicology being closely connected with general linguistics, the history of the language, phonetics, stylistics, and grammar.

According to S. Ullmann, lexicology forms next to phonology, the second basic division of linguistic science (the third is syntax). Consequently, the interaction between vocabulary and grammar is evident in morphology and syntax. Grammar reflects the specific lexical meaning and the capacity of words to be combined in human actual speech. The lexical meaning of the word, in its turn, is frequently signaled by the grammatical context in which it occurs. Thus, morphological indicators help to differentiate the variant meanings of the word (e.g., plural forms that serve to create special lexical meaning: colors, customs, etc.; two kinds of pluralization: brother → brethren — brothers; cloth → cloths — clothes). There are numerous instances when the syntactic position of the word changes both its

function and lexical meaning (e.g., an adjective and a noun element of the same group can change places: library school — school library).

The interrelation between lexicology and phonetics becomes obvious if we think of the fact that the word as the basis unit in lexicological study cannot exist without its sound form, which is the object of study in phonology. Words consist of phonemes that are devoid of meaning of their own, but forming morphemes they serve to distinguish between meanings. The meaning of the word is determined by several phonological features: a) qualitative and quantitative character of phonemes (e.g. dog-dock, pot-port); b) fixed sequence of phonemes (e.g. pot-top, nest-sent-tens); 3) the position of stress (e.g. insult (verb) and insult (noun)).

Summarizing, lexicology is the branch of linguistics concerned with the study of words as individual items and dealing with both formal and semantic aspects of words; and although it is concerned predominantly with an in-depth description of lexemes, it gives a close attention to a vocabulary in its totality, the social communicative essence of a language as a synergetic system being a study focus.

1.2. The word as the fundamental object of lexicology. The morphological structure of the English word. A word is a fundamental unit of a language. The real nature of a word and the term itself has always been one of the most ambiguous issues in almost every branch of linguistics. To use it as a term in the description of language, we must be sure what we mean by it. To illustrate the point here, let us count the words in the following sentence: You can’t tie a bow with the rope in the bow of a boat. Probably the most straightforward answer to this is to say that there are 14. However, the orthographic perspective taken by itself, of course, ignores the meaning of the words, and as soon as we invoke meanings we at least are talking about different words bow, to start with.

Being a central element of any language system, the word is a focus for the problems of phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology, stylistics and also for a number of other language and speech sciences.

Within the framework of linguistics the word has acquired definitions from the syntactic, semantic, phonological points of view as well as a definition combining various approaches. Thus, it has been syntactically defined as “the minimum sentence” by H.Sweet and much later as “the minimum independent unit of utterance” by L.Bloomfield.

E. Sapir concentrates on the syntactic and semantic aspects calling the word

“one of the smallest completely satisfying bits of isolated meaning, into which the sentence resolves itself”.

A purely semantic treatment is observed in S. Ullmann’s explanation of words as meaningful segments that are ultimately composed of meaningful units.

The prominent French linguist A. Meillet combines the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria: “A word is defined by the association of a given meaning with a given group of sounds susceptible of a given grammatical employment”.

Our native school of linguistics understands the word as a dialectical doublefacet unit of form and content, reflecting human notions, and in this sense being considered as a form of their existence. Notions fixed in word meanings are formed as generalized and approximately correct reflections of reality, thus, signifying them words objectivize reality and conceptual worlds in their content.

So, the word is a basic unit of a language resulting from the association of a given meaning with a given cluster of sounds susceptible of a certain grammatical employment.

Taking into consideration the above, let us consider the nature of the word. First, the word is a unit of speech which serves the purposes of human communication. Thus, the word can be defined as a unit of communication.

Secondly, the word can be perceived as the total of the sounds which comprise it.

Third, the word, viewed structurally, possesses several characteristics.

a)The modern approach to the word as a double-facet unit is based on distinguishing between the external and the internal structures of the word. By the external structure of the word we mean its morphological structure. For example, in the word post-impressionists the following morphemes can be distinguished: the prefixes post-, im-, the root –press-, the noun-forming suffixes -ion, -ist, and the grammatical suffix of plurality -s. All these morphemes constitute the external structure of the word post-impressionists.

The internal structure of the word, or its meaning, is nowadays commonly referred to as the word’s semantic structure. This is the word’s main aspect. Words can serve the purposes of human communication solely due to their meanings.

b)Another structural aspect of the word is its unity. The word possesses both its external (or formal) unity and semantic unity. The formal unity of the word is sometimes inaccurately interpreted as indivisibility. The example of postimpressionists has already shown that the word is not, strictly speaking, indivisible, though permanently linked. The formal unity of the word can best be illustrated by comparing a word and a word-group comprising identical constituents. The difference between a blackbird and a black bird is best explained by their relationship with the grammatical system of the language. The word blackbird, which is characterized by unity, possesses a single grammatical framing: blackbirds. The first constituent black is not subject to any grammatical changes. In the word-group a black bird each constituent can acquire grammatical forms of its own: the blackest birds I’ve ever seen. Other words can be inserted between the components which is impossible so far as the word is concerned as it would violate its unity: a black night bird.

The same example may be used to illustrate what we mean by semantic unity. In the word-group a black bird each of the meaningful words conveys a separate concept: bird – a kind of living creature; black – a color. The word blackbird conveys only one concept: the type of bird. This is one of the main features of any

word: it always conveys one concept, no matter how many component morphemes it may have in its external structure.

c) A further structural feature of the word is its susceptibility to grammatical employment. In speech most words can be used in different grammatical forms in which their interrelations are realized.

So, the formal/structural properties of the word are 1) isolatability (words can function in isolation, can make a sentence of their own under certain circumstances); 2) inseparability/unity (words are characterized by some integrity, e.g. a light – alight (with admiration); 3) a certain freedom of distribution (exposition in the sentence can be different); 4) susceptibility to grammatical employment; 5) a word as one of the fundamental units of the language is a double facet unit of form (its external structure) and meaning (its internal/semantic structure).

To sum it up, a word is the smallest naming unit of a language with a more or less free distribution used for the purposes of human communication, materially representing a group of sounds, possessing a meaning, susceptible to grammatical employment and characterized by formal and semantic unity.

There are 4 basic kinds of words: 1)orthographic words – words distinguished from each other by their spelling; 2) phonological words – distinguished from each other by their pronunciation; 3) word-forms which are grammatical variants; 4) words as items of meaning, the headwords of dictionary entries, called lexemes. A lexeme is a group of words united by the common lexical meaning, but having different grammatical forms. The base forms of such words, represented either by one orthographic word or a sequence of words called multi-word lexemes which have to be considered as single lexemes (e.g. phrasal verbs, some compounds) may be termed citation forms of lexemes (sing, talk, head etc), from which other word forms are considered to be derived.

Any language is a system of systems consisting of two subsystems: 1) the system of words’ possible lexical meanings; 2) the system of words’ grammatical forms. The former is called the semantic structure of the word; the latter is its paradigm latent to every part of speech (e.g. a noun has a 4 member paradigm, an adjective – a 3 member one, etc)

As for the main lexicological problems, two of these have already been highlighted. The problem of word-building is associated with prevailing morphological word-structures and with the processes of coining new words. Semantics is the study of meaning. Modern approaches to this problem are characterized by two different levels of study: syntagmatic and paradigmatic.

On the syntagmatic level, the semantic structure of the word is analyzed in its linear relationships with neighboring words in connected speech. In other words, the semantic characteristics of the word are observed, described and studied on the basis of its typical contexts.

On the paradigmatic level, the word is studied in its relationships with other words in the vocabulary system. So, a word may be studied in comparison with other words of a similar meaning (e. g. work, n. – labor, n.; to refuse, v. – to reject v. – to decline, v.), of opposite meaning (e. g. busy, adj. – idle, adj.; to accept, v. –

to reject, v.), of different stylistic characteristics (e. g. man, n. – chap, n. – bloke, n.

— guy, n.). Consequently, the key problems of paradigmatic studies are synonymy, antonymy, and functional styles.

One further important objective of lexicological studies is the study of the vocabulary of a language as a system. Revising the issue, the vocabulary can be studied synchronically (at a given stage of its development), or diachronically (in the context of the processes through which it grew, developed and acquired its modern form). The opposition of the two approaches is nevertheless disputable as the vocabulary, as well as the word which is its fundamental unit, is not only what it is at this particular stage of the language development, but what it was centuries ago and has been throughout its history.

1.3. Inner structure of the word composition. Word building. The morpheme and its types. Morphemic analysis of words. Affixation. The word consists of morphemes. The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe (form) + -eme. The Greek suffix -eme has been adopted by linguists to denote the smallest significant or distinctive unit. The morpheme may be defined as the smallest meaningful unit which has a sound form and meaning, occurring in speech only as a part of a word. In other words, a morpheme is an association of a given meaning with a given sound pattern. But unlike a word it is not autonomous. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of a single morpheme. Nor are they divisible into smaller meaningful units. That is why the morpheme may also be defined as the minimum double-facet (shape/meaning) meaningful language unit that can be subdivided into phonemes (the smallest single-facet distinctive units of language with no meaning of their own). So there are 3 lower levels of a language – a phoneme, a morpheme, a word.

Word building (word-formation) is the creation of new words from elements already existing in a particular language. Every language has its own patterns of word formation. Together with borrowing, word-building provides for enlarging and enriching the vocabulary of the language.

A form is considered to be free if it may stand alone without changing its meaning; if not, it is a bound form, so called because it is always bound to something else. For example, comparing the words sportive and elegant and their parts, we see that sport, sortive, elegant may occur alone as utterances, whereas eleg-, -ive, -ant are bound forms because they never occur alone. A word is, by L. Bloomfield’s definition, a minimum free form. A morpheme is said to be either bound or free. This statement should be taken with caution because some morphemes are capable of forming words without adding other morphemes, being homonymous to free forms.

Words are segmented into morphemes with the help of the method of morphemic analysis whose aim is to split the word into its constituent morphemes and to determine their number and types. This is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into immediate constituents (IC’s), first suggested by L. Bloomfield. The procedure consists of

several stages: 1) segmentation of words; 2) identification of morphs; 3) classification of morphemes.

The procedure generally used to segment words into the constituting morphemes is the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. It is based on a binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents (ICs) Each IC at the next stage of the analysis is in turn broken into two smaller meaningful elements. This analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of any further division, i.e. morphemes. In terms of the method employed these are referred to as the Ultimate Constituents (UCs).

The analysis of the morphemic structure of words reveals the ultimate meaningful constituents (UCs), their typical sequence and arrangement, but it does not show the way a word is constructed. The nature, type and arrangement of the ICs of the word are known as its derivative structure. Though the derivative structure of the word is closely connected with its morphemic structure and often coincides with it, it cardinally differs from it. The derivational level of the analysis aims at establishing correlations between different types of words, the structural and semantic patterns being focused on, enabling one to understand how new words appear in a language.

Coming back to the issue of word segmentability as the first stage of the analysis into immediate constituents, all English words fall into two large classes: 1) segmentable words, i.e. those allowing of segmentation into morphemes, e.g. information, unputdownable, silently and 2) non-segmentable words, i.e. those not allowing of such segmentation, e.g. boy, wife, call, etc.

There are three types of segmentation of words: complete, conditional and defective. Complete segmentability is characteristic of words whose the morphemic structure is transparent enough as their individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word lending themselves easily to isolation. Its constituent morphemes recur with the same meaning in many other words, e.g. establishment, agreement.

Conditional morphemic segmentability characterizes words whose segmentation into constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons. For instance, in words like retain, detain, or receive, deceive the sound-clusters [ri], [di], on the one hand, can be singled out quite easily due to their recurrence in a number of words, on the other hand, they sure have nothing in common with the phonetically identical morphemes re-. de- as found in words like rewrite, reorganize, decode, deurbanize; neither the sound-clusters [ri], [di] nor the soundclusters [-tein], [si:v] have any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Therefore, the morphemes making up words of conditional segmentability differ from morphemes making up words of complete segmentability in that the former do not reach the full status of morphemes for the semantic reason and that is why a special term is applied to them – pseudo-morphemes or quasi-morphemes.

Defective morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose unique morphemic components seldom or never recur in other words (e.g. in the words

cranberry, gooseberry, strawberry defective morphemic segmentability is obvious due to the fact that the morphemes cran-, goose-, straw- are unique morphemes).

Thus, on the level of morphemic analysis there are basically two types of elementary units: full morphemes and pseudo- (quasi-)morphemes, the former being genuine structural elements of the language system in the prime focus of linguistic attention. At the same time, a significant number of words of conditional and defective segmentability reveal a complex nature of the morphological system of the English language, representing various heterogeneous layers in its vocabulary.

The second stage of morphemic analysis is identification of morphs. The main criteria here are semantic and phonetic similarity. Morphs should have the same denotational meaning, but their phonemic shape can vary (e.g. please, pleasing, pleasure, pleasant or duke, ducal, duchess, duchy). Such phonetically conditioned positional morpheme variants are called allomorphs. They occur in a specific environment, being identical in meaning or function and characterized by complementary distribution.(e.g. the prefix in- (intransitive) can be represented by allomorphs il- (illiterate), im- (impossible), ir- (irregular)). Complementary distribution is said to take place when two linguistics variants cannot appear in the same environment (Not the same as contrastive distribution by which different morphemes are characterized, i.e. if they occur in the same environment, they signal different meanings (e.g. the suffixes -able (capable of being): measurable and -ed (a suffix of a resultant force): measured).

The final stage of the procedure of the morphemic analysis is classification of morphemes. Morphemes can be classified from 6 points of view (POV).

1. Semantic POV: roots and affixes/non-roots. A root is the lexical nucleus of a word bearing the major individual meaning common to a set of semantically related words, constituting one word cluster/word-family (e.g. learn-learner- learned-learnable; heart-hearten, dishearten, hear-broken, hearty, kind-hearted etc.) with which no grammatical properties of the word are connected. In this respect, the peculiarity of English as a unique language is explained by its analytical language structure – morphemes are often homonymous with independent units (words). A morpheme that is homonymous with a word is called a root morpheme.

Here we have to mention the difference between a root and a stem. A root is the ultimate constituent which remains after the removal of all functional and derivational affixes and does not admit any further analysis. Unlike a root, a stem is that part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm (formal aspect). For instance, heart-hearts-to one’s heart’s content vs. hearty-heartier-the heartiest. It is the basic unit at the derivational level, taking the inflections which shape the word grammatically as a part of speech.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled (e.g. pocket, motion, receive, etc.).

Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morphemes (sell, grow, kink, etc.).

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures, they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their immediate constituents and the correlated stems. Derived stems are mostly polymorphic (e.g. governments, unbelievable, etc.).

Compound stems are made up of two immediate constituents, both of which are themselves stems, e.g. match-box, pen-holder, ex-film-star, etc. It is built by joining two stems, one of which is simple, the other is derived.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes.

Compound words have at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

So, there are 4 structural types of words in English: 1) simple words (singleroot morphemes, e.g. agree, child, red, etc.); 2) derivatives (affixational derived words) consisting one or more affixes: enjoyable, childhood, unbelievable). Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.). In Modern English, it has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, n.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.); 3) compound words consisting of two or more stems (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing, etc.). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition; 4) derivational compounds in which phrase components are joined together by means of compounding and affixation (e.g. oval-shaped, strong-willed, care-free); 5) phrasal verbs as a result of a strong tendency of English to simplification (to put up with, to give up, to take for, etc.)

The morpheme, and therefore the affix, which is a type of morpheme, is generally defined as the smallest indivisible component of the word possessing a meaning of its own. Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalized meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is all-embracing. So, the noun-forming suffix -er could be roughly defined as designating persons from the object of their occupation or labor (painter – the one who paints) or from their place of origin (southerner – the one living in the South). The adjectiveforming suffix -ful has the meaning of «full of», «characterized by» (beautiful, careful) whereas -ish may often imply insufficiency of quality (greenish – green, but not quite).

There are numerous derived words whose meanings can really be easily deduced from the meanings of their constituent parts. Yet, such cases represent only the first stage of semantic readjustment within derivatives. The constituent morphemes within derivatives do not always preserve their current meanings and are open to subtle and complicated semantic shifts (e.g. bookish: (1) given or devoted to reading or study; (2) more acquainted with books than with real life, i. e. possessing the quality of bookish learning).

The semantic distinctions of words produced from the same root by means of different affixes are also of considerable interest, both for language studies and research work. Compare: womanly (used in a complimentary manner about girls and women) – womanish (used to indicate an effeminate man and certainly implies criticism); starry (resembling stars) – starred (covered or decorated with stars).

There are a few roots in English which have developed a great combining ability in the position of the second element of a word and a very general meaning similar to that of an affix. These are semi-affixes because semantically, functionally, structurally and stylistically they behave more like affixes than like roots, determining the lexical and grammatical class the word belongs to (e.g. -man: cameraman, seaman; -land: Scotland, motherland; -like: ladylike, flowerlike; — worthy: trustworthy, praiseworthy; -proof: waterproof, bullet-proof, etc.)

2.Position POV: according to their position affixational morphemes fall into suffixes – derivational morphemes following the root and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class (writer, rainy, magnify, etc.), infexes – affixes placed within the word (e.g. adapt-a-tion, assimil-a-tion, sta-n-d etc.), and prefixes – derivational morphemes that precede the root and modify the meaning (e.g. decipher, illegal, unhappy, etc.) The process of affixation itself consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to a root morpheme. Suffixation is more productive than prefixation in Modern English.

3.Functional POV: from this perspective affixational morphemes include derivational morphemes as affixal morphemes that serve to make a new part of speech or create another word in the same one, modifying the lexical meaning of the root (e.g. to teach-teacher; possible-impossible), and functional morphemes, i.e. grammatical ones/inflections that serve to build grammatical forms, the paradigm of the word (e.g. has broken; oxen; clues), carrying only grammatical meaning and thus relevant only for the formation of words. Some functional morphemes have a dual character. They are called functional word-morphemes (FWM) – auxiliaries (e.g. is, are, have, will, etc). The main function of FWM is to build analytical structures.

As for word combinations, being two components expressing one idea (e.g. to give up – to refuse; to take in – to deceive) they are full fleshed words. Their function is to derive new words with new meanings. They behave like derivational morphemes with a functional form. They are called derivational word

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Тема 1. Types of

language Units

1. Lexicology

2. Language Units.

3. Structural Types of words.

4. Word combination

1.

Lexicology

The term lexicology is of Greek origin (from lexis –

word and logos —

science). Lexicology is the part of linguistics which deals

with the vocabulary and

characteristic features of words and word-groups.

The term

word denotes the main lexical unit of a language resulting from the

association of a group of sounds with a meaning. This

unit is used in grammatical

functions characteristic of it. It is the smallest

unit of a language which can stand

alone as a complete utterance.

The term

word-group denotes a group of words which exists in the language

as a ready-made unit, has the unity of meaning, the

unity of syntactical function,

e.g. the word-group as loose as a goose means clumsy (неуклюжий) and is used in a sentence as a predicative (именная часть составного сказуемого) (He is as loose as a goose).

Lexicology

can be general and special. General lexicology is the lexicology

of any language, part of General Linguistics. It is

aimed at establishing language

universals – linguistic phenomena and properties

common to all languages.

Special

lexicology is the lexicology of a particular language (English,

German, Russian, etc.).

Lexicology can study the development of the vocabulary, the origin of

words and word-groups, their semantic relations and

the development of their

sound form and meaning. In this case it is called

historical lexicology.

Another

branch of lexicology is called descriptive and studies the

vocabulary at a definite stage of its development.

Lexicology and its Connection

with Other Linguistc Disciplines

Lexicology is closely connected with other branches of

linguistcs:

1. It is connected with Phonetics because the word‘s

sound form is a fixed

sequence of phonemes united by a lexical stress.

2. Lexicology is connected with Morphology and

Word-Formation as the

word‘s structure is a fixed sequence of morphemes.

3. It is connected with Morphology because the word‘s

content plane is a

unity of lexical and grammatical meanings.

4. The word functions as part of the sentence and

performs a certain

syntactical function that is why it is also connected

with Syntax.

5. The word functions in different situations and

spheres of life therefore it

is connected with Stylistics, Socio- and

Psycholinguistics.

But

there is also a great difference between lexicology and other linguistc

disciplines. Grammatical and phonological systems are

relatively stable. Therefore

they are mostly studied within the framework of

intralinguistics.

Lexical system is never stable. It is directly

connected with extralinguistic

systems. It is constantly growing and decaying (распадаться). It is immediately reacts to changes in social

life, e.g. the intense development of science and technology in the 20th

century gave birth to such words as computer, sputnik, spaceship. Therefore

lexicology is a sociolinguistic discipline. It studies each particular word,

both its intra- and extralingiustic relations.

Lexicology is subdivided into a number of autonomous

but interdependent

disciplines:

1. Lexicological Phonetics. It studies the expression

plane of lexical units in

isolation and in the flow of speech.

2. Semasiology. It deals with the meaning of words and

other linguistic

units: morphemes, word-formation types, morphological

word classes and

morphological categories.

3. Onomasiology or Nomination Theory. It deals with

the process of

nomination: what name this or that object has and why.

4. Etymology. It studies the origin, the original

meaning and form of words.

5. Praseology. It deals with phraseological units.

6. Lexicography. It is a practical science. It

describes the vocabulary and

each lexical unit in the form of dictionaries.

7. Lexical Morphology. It deals with the morphological

structure of the word.

8. Word-formation. It deals with the patterns which

are used in coining new

words.

Modern

English lexicology investigates the problems of word structure and word

formation; it also investigates the word structure of English, the classification

of vocabulary units; the relations between different lexical layers4 of the

English vocabulary and some other. Lexicology came into being to meet the

demands of different branches of applied linguistic!

2.

Language units

The main unit of the lexical system of a language

resulting from the association of a group of sounds with a meaning is a word. This unit is used in

grammatical functions characteristic of it. It is the smallest language unit

which can stand alone as a complete utterance.

The modern approach to word studies is based on

distinguishing between the

external and the internal structures of the word.

By

external structure of the word we mean its morphological structure. For

example, in the word post-impressionists the following

morphemes can be

distinguished: the prefixes post-, im-, the root

press, the noun-forming suffixes –

ion, -ist, and the grammatical suffix of plurality –s.

The

external structure of the word, and also typical word-formation patterns,

are studied in the framework of word-building.

The

internal structure of the word, or its meaning, is nowadays commonly

referred to as the word‘s semantic structure. This is

the word‘s main aspect.

The

area of lexicology specialising in the semantic studies of the word is

called semantics.

One of

the main structural features of the word that it possesses both

external (formal) unity and semantic unity.

A

further structural feature of the word is its susceptibility- восприимчивость) to grammatical employment. In speech most

words can be used in different grammatical forms in which their interrelations

are realized.

A word can be

divided into smaller sense units — morphemes. The morpheme is the smallest

meaningful language unit. The morpheme consists of a class of variants,

allomorphs, which are either phonologically or morphologically conditioned,

e.g. please, pleasant, pleasure.

Morphemes are divided into two large groups: lexical morphemes and grammatical

(functional) morphemes. Both lexical and grammatical morphemes can be free and

bound. Free lexical morphemes are roots of words which express the lexical

meaning of the word, they coincide with the stem of simple words. Free

grammatical morphemes are function words: articles, conjunctions and

prepositions ( the, with, and).

Bound lexical morphemes are affixes: prefixes (dis-), suffixes (-ish) and also

blocked (unique) root morphemes (e.g. Fri-day, cran-berry). Bound grammatical

morphemes are inflexions (endings), e.g. -s for the Plural of nouns, -ed for

the Past Indefinite of regular verbs, -ing for the Present Participle, -er for

the Comparative degree of adjectives.

In the second half of the twentieth century the English word building system

was enriched by creating so called splinters which scientists include in the

affixation stock of the Modern English wordbuilding system. Splinters are the

result of clipping the end or the beginning of a word and producing a number of

new words on the analogy with the primary word-group. For example, there are

many words formed with the help of the splinter mini- (apocopе (апокопа, отпадение последнего слога или звука в слове) produced by clipping the word «miniature»), such as

«miniplane», «minijet», «minicycle», «minicar», «miniradio» and many others.

All of these words denote objects of smaller than normal dimensions.

On the analogy with «mini-» there

appeared the splinter «maxi»- (apocopе produced

by clipping the word «maximum»), such words as «maxi-series», «maxi-sculpture»,

«maxi-taxi» and many others appeared in the language.

There are also splinters which are

formed by means of apheresis, that is clipping the beginning of a word.

In the seventieths of the twentieth century there was

a political scandal in the hotel «Watergate» where the Democratic Party of the

USA had its pre-election headquarters. Republicans managed to install bugs

there and when they were discovered there was a scandal and the ruling American

government had to resign. The name «Watergate» acquired the meaning «a

political scandal», «corruption». On the analogy with this word quite a number

of other words were formed by using the splinter «gate» (apheresis of the word

«Watergate»), such as: «Irangate», »Westlandgate», »shuttlegate», »milliongate»

etc. The splinter «gate» is added mainly to Proper names: names of people with

whom the scandal is connected or a geographical name denoting the place where

the scandal occurred.

The splinter «mobile» was formed by clipping the beginning of the word

«automobile» and is used to denote special types of automobiles, such as:

«artmobile», «bookmobile», «snowmobile», «tourmobile» etc.

3. According to

the nature and the number of morphemes constituting a word there are different

structural types of words in English: simple, derived, compound,

compound-derived.

Simple words consist of one root morpheme and an inflexion (in many cases the

inflexion is zero), e.g. «seldom», «chairs», «longer», «asked».

Derived words consist of one root morpheme, one or several affixes and an

infection, e.g. «deristricted (снимать ограничения)», «unemployed».

Compound words consist of two or more root morphemes and an inflexion, e.g.

«baby-moons»(искусств.спутник земли), «wait-and-see (policy) выжидательная политика».

Compound-derived words consist of two or more root morphemes, one or more

affixes and an inflexion, e.g. «middle-of-the-roaders» человек занимающий половинчатую позицию, «job-hopper»летун, человек часто меняющий работу.

When speaking about the structure of words stems also

should be mentioned. The stem is the part of the word which remains unchanged

throughout the paradigm of the word, e.g. the stem «hop» can be found in the

words: «hop», «hops», «hopped», «hopping». The stem «hippie» can be found in

the words: «hippie», «hippies», «hippie’s», «hippies’». The stem «job-hop» can

be found in the words : «job-hop», «job-hops», «job-hopped», «job-hopping».

So stems, the same as words, can be simple, derived, compound and

compound-derived. Stems have not only the lexical meaning but also grammatical

(part-of-speech) meaning, they can be noun stems («girl» in the adjective

«girlish»), adjective stems («girlish» in the noun «girlishness»), verb stems

(«expell» in the noun «expellee») etc. They differ from words by the absence of

inflexions in their structure, they can be used only in the structure of words.

Sometimes it is rather difficult to distinguish between simple and derived

words, especially in the cases of phonetic borrowings from other languages and

of native words with blocked (unique) root morphemes, e.g. «perestroika»,

«cranberry», «absence» etc.

In the English language of the second half of the twentieth century there

developed so called block compounds, that is compound words which have a

uniting stress but a split spelling, such as «chat show», «pinguin suit» etc.

Such compound words can be easily mixed up with word-groups of the type «stone

wall», so called nominative binomials

два названия. Such linguistic units serve to denote a notion which

is more specific than the notion expressed by the second component and consists

of two nouns, the first of which is an attribute to the second one. If we

compare a nominative binomial with a compound noun with the structure N+N we

shall see that a nominative binomial has no unity of stress. The change of the

order of its components will change its lexical meaning, e.g. «vid kid» is «a

kid who is a video fan» while «kid vid» means «a video-film for kids» or else

«lamp oil» means «oil for lamps» and «oil lamp» means «a lamp which uses oil

for burning».

Thus, we can draw the conclusion that in Modern English the following language

units can be mentioned: morphemes, splinters, words, nominative binomials,

non-idiomatic and idiomatic word-combinations, sentences.

4. Word-Combination

What is a Word-Combination?

The word-combination (WC) is the largest two-facet

lexical unit observed

on the syntagmatic level of analysis. By the degree of

their structural and semantic

cohesion(kouhizhn связь)

Lexical combinability (collocation) is the aptness of a word to appear

in

certain lexical contexts, e.g. the word question

combines with certain adjectives:

delicate, vital, important.

Each

word has a certain norm of collocation. Any departure from this norm

is felt as a stylistic device: to shove a question.

The collocations

of correlated words in different languages are not identical,

e.g. both the English flower and its Russian

counterpart цветок

can be combined

with a number of words denoting the place where the

flowers are grown: garden-

flowers, hot-house flowers; садовые цветы, оранжерейные цветы. But the

English word cannot enter into combination with the

word room to denote flowers

growing in the rooms, cf.: комнатные цветы – pot flowers.

Grammatical combinability (colligation) is the aptness of a word to

appear

in certain grammatical contexts, e.g. the adjective

heavy can be followed by a noun

(heavy storm), by an infinitive (heavy to lift). Each

grammatical unit has a certain

norm of colligation: nouns combine with pre-positional

adjectives (a new dress),

relative adjectives combine with pre-positional

adverbs of degree (dreadfully

tired).

The

departure from the norm of colligation is usually impossible:

mathematics at clever is a meaningless string of words

because English nouns do

not allow of the structure N + at + A.

Categories of

Word-Combinations

The study of

WCs is based on the following set of oppositions each

constituting a separate category:

1. Neutral

and stylistically marked WCs: old coat – old boy;

2.

Variable and stable WCs: take a pen – take place;

3.

Non-idiomatic and idiomatic WCs: to speak plainly – to call a spade a

spade;

4.

Usual and occasional WCs: blue sky – angry sky;

5.

Conceptually determined and conceptually non-determined WCs: clean

dress – clean dirt;

6.

Sociolinguistically determined and sociolinguistically non-determined

WCs:

cold war – cold soup.

II. Meaning of Word-Combinations

Meaning of

WCs is anlysed into lexical and grammatical (structural

components).

Lexical meaning of the WC is the combined lexical

meanings of its component

words: red flower – red + flower. But in most cases

the meaning of the whole

combination predominates over the lexical meaning of

its constituents, e.g. the

meaning of the monosemantic adjective atomic is

different in atomic weight and

atomic bomb.

Polysemantic words are used in WCs in one of their meanings: blind man

(horse, cat) – blind type (print, handwriting). Only

one meaning of the adjective

blind (unable to see) is combined with the lexical

meaning of the noun man

(human being) and only one meaning of man is realized

in combination with blind.

The meaning of the same adjective in blind type is

different.

Structural

meaning of the WC is conveyed by the pattern of arrangement of

the component words, e.g. the WCs school grammar and

grammar school consist

of identical words but are semantically different

because their patterns are

different. The structural pattern is the carrier of a

certain meaning quality-

substance that does not depend on the lexical meanings

of the words school and

grammar.

III. Interdependence of Structure and Meaning in

Word-Combinations

The

pattern of the WC is the syntactic structure in which a given word is

used as its head: to build + N (to build a house); to

rely + on + N (to rely on sb).

The pattern and meaning of head-words are

interdependent. The same head-word

is semantically different in different patterns, cf.:

get+N (get a letter); get+to+N

(get to Moscow); get+N+inf (get sb to come).

In these

patterns notional words are represented in conventional symbols

whereas form-words are given in their usual graphic

form. The reason is that

individual form-words may change the meaning of the

word with which it is

combined: anxious+for+N (anxious for news),

anxious+about+N (anxious about

his health).

Structurally simple patterns are usually polysemantic: the pattern

take+N

represents several meanings of the polysemantic

head-word: take tea (coffee), take

neasures (precautions). Structurally complex patterns

are usually monosemantic:

the pattern take+to+N represents only one meaning of

take – take to sports (to sb).

IV. Motivation in

Word-Combinations

Motivation

in WCs may be lexical or grammatical (structural). The WC is

motivated if its meaning is deducible from the

meaning, order and arrangement of

its components: red flower – red+flower –

quality+substance – A+N. Non-

motivated WCs are indivisible lexically and

structurally. They are called

phraseological units.

The WC is

lexially non-motivated if its combined lexical meaning is not

deducible from the meaning of its components: red tape

–bureaucratic methods.

The WC represents a single indivisible semantic

entity.

The WC is

structurally non-motivated if the meaning of its pattern is not

deducible from the order and arrangement of its

components: red tape – substance

– N. The WC represents a single indivisible structural

entity.

V. Categories of

Word-Combinations

The study

of WCs is based on the following set of oppositions each

constituting a separate category:

1. Neutral

and stylistically marked WCs: old coat – old boy;

2.

Variable and stable WCs: take a pen – take place;

3.

Non-idiomatic and idiomatic WCs: to speak plainly – to call a spade a

spade;

4.

Usual and occasional WCs: blue sky – angry sky;

5.

Conceptually determined and conceptually non-determined WCs: clean

dress – clean dirt;

6.

Sociolinguistically determined and sociolinguistically non-determined

WCs:

cold war – cold soup.

Chapter 5 how english words are made. word-building1

Before turning to the various processes of making words, it would be useful to analyse the related problem of the composition of words, i. e. of their constituent parts.

If viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units which are called morphemes. Morphemes do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of words. Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals} and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in re-read, mis-pronounce, un-well) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach-er, cur-able, diet-ate).

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation).

Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and, in Modern English, has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, п.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.).

Another wide-spread word-structure is a compound word consisting of two or more stems2 (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition.

The somewhat odd-looking words like flu, pram, lab, M. P., V-day, H-bomb are called shortenings, contractions or curtailed words and are produced by the way of word-building called shortening (contraction).