Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs.[1]

They play an important role in all aspects of cognition.[2][3] As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.[4]

In contemporary philosophy, there are at least three prevailing ways to understand what a concept is:[5]

- Concepts as mental representations, where concepts are entities that exist in the mind (mental objects)

- Concepts as abilities, where concepts are abilities peculiar to cognitive agents (mental states)

- Concepts as Fregean senses, where concepts are abstract objects, as opposed to mental objects and mental states

Concepts can be organized into a hierarchy, higher levels of which are termed «superordinate» and lower levels termed «subordinate». Additionally, there is the «basic» or «middle» level at which people will most readily categorize a concept.[6] For example, a basic-level concept would be «chair», with its superordinate, «furniture», and its subordinate, «easy chair».

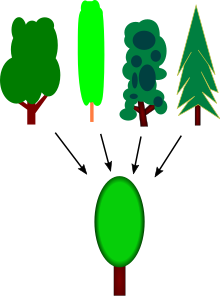

A representation of the concept of a tree. The four upper images of trees can be roughly quantified into an overall generalization of the idea of a tree, pictured in the lower image.

Concepts may be exact, or inexact.[7]

When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

A concept is instantiated (reified) by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are things in the real world or other ideas.

Concepts are studied as components of human cognition in the cognitive science disciplines of linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, where an ongoing debate asks whether all cognition must occur through concepts. Concepts are regularly formalized in mathematics, computer science, databases and artificial intelligence. Examples of specific high-level conceptual classes in these fields include classes, schema or categories. In informal use the word concept often just means any idea.

Ontology of concepts[edit]

A central question in the study of concepts is the question of what they are. Philosophers construe this question as one about the ontology of concepts—what kind of things they are. The ontology of concepts determines the answer to other questions, such as how to integrate concepts into a wider theory of the mind, what functions are allowed or disallowed by a concept’s ontology, etc. There are two main views of the ontology of concepts: (1) Concepts are abstract objects, and (2) concepts are mental representations.[8]

Concepts as mental representations[edit]

The psychological view of concepts[edit]

Within the framework of the representational theory of mind, the structural position of concepts can be understood as follows: Concepts serve as the building blocks of what are called mental representations (colloquially understood as ideas in the mind). Mental representations, in turn, are the building blocks of what are called propositional attitudes (colloquially understood as the stances or perspectives we take towards ideas, be it «believing», «doubting», «wondering», «accepting», etc.). And these propositional attitudes, in turn, are the building blocks of our understanding of thoughts that populate everyday life, as well as folk psychology. In this way, we have an analysis that ties our common everyday understanding of thoughts down to the scientific and philosophical understanding of concepts.[9]

The physicalist view of concepts[edit]

In a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is a mental representation, which the brain uses to denote a class of things in the world. This is to say that it is literally, a symbol or group of symbols together made from the physical material of the brain.[10][11] Concepts are mental representations that allow us to draw appropriate inferences about the type of entities we encounter in our everyday lives.[11] Concepts do not encompass all mental representations, but are merely a subset of them.[10] The use of concepts is necessary to cognitive processes such as categorization, memory, decision making, learning, and inference.[12]

Concepts are thought to be stored in long term cortical memory,[13] in contrast to episodic memory of the particular objects and events which they abstract, which are stored in hippocampus. Evidence for this separation comes from hippocampal damaged patients such as patient HM. The abstraction from the day’s hippocampal events and objects into cortical concepts is often considered to be the computation underlying (some stages of) sleep and dreaming. Many people (beginning with Aristotle) report memories of dreams which appear to mix the day’s events with analogous or related historical concepts and memories, and suggest that they were being sorted or organized into more abstract concepts. («Sort» is itself another word for concept, and «sorting» thus means to organize into concepts.)

Concepts as abstract objects[edit]

The semantic view of concepts suggests that concepts are abstract objects. In this view, concepts are abstract objects of a category out of a human’s mind rather than some mental representations.[8]

There is debate as to the relationship between concepts and natural language.[5] However, it is necessary at least to begin by understanding that the concept «dog» is philosophically distinct from the things in the world grouped by this concept—or the reference class or extension.[10] Concepts that can be equated to a single word are called «lexical concepts».[5]

The study of concepts and conceptual structure falls into the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science.[11]

In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing. It may represent a natural object that exists in the real world like a tree, an animal, a stone, etc. It may also name an artificial (man-made) object like a chair, computer, house, etc. Abstract ideas and knowledge domains such as freedom, equality, science, happiness, etc., are also symbolized by concepts. It is important to realize that a concept is merely a symbol, a representation of the abstraction. The word is not to be mistaken for the thing. For example, the word «moon» (a concept) is not the large, bright, shape-changing object up in the sky, but only represents that celestial object. Concepts are created (named) to describe, explain and capture reality as it is known and understood.

A priori concepts[edit]

Kant maintained the view that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are twelve categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema. He held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result from abstraction «a posteriori concepts» (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1)

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are:

- comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness;

- reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally

- abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ …

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

— Logic, §6

Embodied content[edit]

In cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995; see conceptual blending). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato’s term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism, the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.[citation needed]

Realist universal concepts[edit]

Platonist views of the mind construe concepts as abstract objects.[14] Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say, this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato’s ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.[15]

Sense and reference[edit]

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status.[8]

Concepts in calculus[edit]

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Notable theories on the structure of concepts[edit]

Classical theory[edit]

The classical theory of concepts, also referred to as the empiricist theory of concepts,[10] is the oldest theory about the structure of concepts (it can be traced back to Aristotle[11]), and was prominently held until the 1970s.[11] The classical theory of concepts says that concepts have a definitional structure.[5] Adequate definitions of the kind required by this theory usually take the form of a list of features. These features must have two important qualities to provide a comprehensive definition.[11] Features entailed by the definition of a concept must be both necessary and sufficient for membership in the class of things covered by a particular concept.[11] A feature is considered necessary if every member of the denoted class has that feature. A feature is considered sufficient if something has all the parts required by the definition.[11] For example, the classic example bachelor is said to be defined by unmarried and man.[5] An entity is a bachelor (by this definition) if and only if it is both unmarried and a man. To check whether something is a member of the class, you compare its qualities to the features in the definition.[10] Another key part of this theory is that it obeys the law of the excluded middle, which means that there are no partial members of a class, you are either in or out.[11]

The classical theory persisted for so long unquestioned because it seemed intuitively correct and has great explanatory power. It can explain how concepts would be acquired, how we use them to categorize and how we use the structure of a concept to determine its referent class.[5] In fact, for many years it was one of the major activities in philosophy—concept analysis.[5] Concept analysis is the act of trying to articulate the necessary and sufficient conditions for the membership in the referent class of a concept.[citation needed] For example, Shoemaker’s classic «Time Without Change» explored whether the concept of the flow of time can include flows where no changes take place, though change is usually taken as a definition of time.[citation needed]

Arguments against the classical theory[edit]

Given that most later theories of concepts were born out of the rejection of some or all of the classical theory,[14] it seems appropriate to give an account of what might be wrong with this theory. In the 20th century, philosophers such as Wittgenstein and Rosch argued against the classical theory. There are six primary arguments[14] summarized as follows:

- It seems that there simply are no definitions—especially those based in sensory primitive concepts.[14]

- It seems as though there can be cases where our ignorance or error about a class means that we either don’t know the definition of a concept, or have incorrect notions about what a definition of a particular concept might entail.[14]

- Quine’s argument against analyticity in Two Dogmas of Empiricism also holds as an argument against definitions.[14]

- Some concepts have fuzzy membership. There are items for which it is vague whether or not they fall into (or out of) a particular referent class. This is not possible in the classical theory as everything has equal and full membership.[14]

- Experiments and research showed that assumptions of well defined concepts and categories might not be correct. Researcher Hampton[16]asked participants to differentiate whether items were in different categories. Hampton did not conclude that items were either clear and absolute members or non-members. Instead, Hampton found that some items were barely considered category members and others that were barely non-members. For example, participants considered sinks as barely members of kitchen utensil category, while sponges were considered barely non-members, with much disagreement among participants of the study. If concepts and categories were very well defined, such cases should be rare. Since then, many researches have discovered borderline members that are not clearly in or out of a category of concept.

- Rosch found typicality effects which cannot be explained by the classical theory of concepts, these sparked the prototype theory.[14] See below.

- Psychological experiments show no evidence for our using concepts as strict definitions.[14]

Prototype theory[edit]

Prototype theory came out of problems with the classical view of conceptual structure.[5] Prototype theory says that concepts specify properties that members of a class tend to possess, rather than must possess.[14] Wittgenstein, Rosch, Mervis, Berlin, Anglin, and Posner are a few of the key proponents and creators of this theory.[14][17] Wittgenstein describes the relationship between members of a class as family resemblances. There are not necessarily any necessary conditions for membership; a dog can still be a dog with only three legs.[11] This view is particularly supported by psychological experimental evidence for prototypicality effects.[11] Participants willingly and consistently rate objects in categories like ‘vegetable’ or ‘furniture’ as more or less typical of that class.[11][17] It seems that our categories are fuzzy psychologically, and so this structure has explanatory power.[11] We can judge an item’s membership of the referent class of a concept by comparing it to the typical member—the most central member of the concept. If it is similar enough in the relevant ways, it will be cognitively admitted as a member of the relevant class of entities.[11] Rosch suggests that every category is represented by a central exemplar which embodies all or the maximum possible number of features of a given category.[11] Lech, Gunturkun, and Suchan explain that categorization involves many areas of the brain. Some of these are: visual association areas, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and temporal lobe.

The Prototype perspective is proposed as an alternative view to the Classical approach. While the Classical theory requires an all-or-nothing membership in a group, prototypes allow for more fuzzy boundaries and are characterized by attributes.[18] Lakoff stresses that experience and cognition are critical to the function of language, and Labov’s experiment found that the function that an artifact contributed to what people categorized it as.[18] For example, a container holding mashed potatoes versus tea swayed people toward classifying them as a bowl and a cup, respectively. This experiment also illuminated the optimal dimensions of what the prototype for «cup» is.[18]

Prototypes also deal with the essence of things and to what extent they belong to a category. There have been a number of experiments dealing with questionnaires asking participants to rate something according to the extent to which it belongs to a category.[18] This question is contradictory to the Classical Theory because something is either a member of a category or is not.[18] This type of problem is paralleled in other areas of linguistics such as phonology, with an illogical question such as «is /i/ or /o/ a better vowel?» The Classical approach and Aristotelian categories may be a better descriptor in some cases.[18]

Theory-theory[edit]

Theory-theory is a reaction to the previous two theories and develops them further.[11] This theory postulates that categorization by concepts is something like scientific theorizing.[5] Concepts are not learned in isolation, but rather are learned as a part of our experiences with the world around us.[11] In this sense, concepts’ structure relies on their relationships to other concepts as mandated by a particular mental theory about the state of the world.[14] How this is supposed to work is a little less clear than in the previous two theories, but is still a prominent and notable theory.[14] This is supposed to explain some of the issues of ignorance and error that come up in prototype and classical theories as concepts that are structured around each other seem to account for errors such as whale as a fish (this misconception came from an incorrect theory about what a whale is like, combining with our theory of what a fish is).[14] When we learn that a whale is not a fish, we are recognizing that whales don’t in fact fit the theory we had about what makes something a fish. Theory-theory also postulates that people’s theories about the world are what inform their conceptual knowledge of the world. Therefore, analysing people’s theories can offer insights into their concepts. In this sense, «theory» means an individual’s mental explanation rather than scientific fact. This theory criticizes classical and prototype theory as relying too much on similarities and using them as a sufficient constraint. It suggests that theories or mental understandings contribute more to what has membership to a group rather than weighted similarities, and a cohesive category is formed more by what makes sense to the perceiver. Weights assigned to features have shown to fluctuate and vary depending on context and experimental task demonstrated by Tversky. For this reason, similarities between members may be collateral rather than causal.[19]

Ideasthesia[edit]

According to the theory of ideasthesia (or «sensing concepts»), activation of a concept may be the main mechanism responsible for the creation of phenomenal experiences. Therefore, understanding how the brain processes concepts may be central to solving the mystery of how conscious experiences (or qualia) emerge within a physical system e.g., the sourness of the sour taste of lemon.[20] This question is also known as the hard problem of consciousness.[21][22] Research on ideasthesia emerged from research on synesthesia where it was noted that a synesthetic experience requires first an activation of a concept of the inducer.[23] Later research expanded these results into everyday perception.[24]

There is a lot of discussion on the most effective theory in concepts. Another theory is semantic pointers, which use perceptual and motor representations and these representations are like symbols.[25]

Etymology[edit]

The term «concept» is traced back to 1554–60 (Latin conceptum – «something conceived»).[26]

See also[edit]

- Abstraction

- Categorization

- Class (philosophy)

- Conceptualism

- Concept and object

- Concept map

- Conceptual blending

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual history

- Conceptual model

- Conversation theory

- Definitionism

- Formal concept analysis

- Fuzzy concept

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Idea

- Ideasthesia

- Noesis

- Notion (philosophy)

- Object (philosophy)

- Process of concept formation

- Schema (Kant)

- Intuitive statistics

References[edit]

- ^ Goguen, Joseph (2005). «What is a Concept?». Conceptual Structures: Common Semantics for Sharing Knowledge. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3596. pp. 52–77. doi:10.1007/11524564_4. ISBN 978-3-540-27783-5.

- ^ Chapter 1 of Laurence and Margolis’ book called Concepts: Core Readings. ISBN 9780262631938

- ^ Carey, S. (1991). Knowledge Acquisition: Enrichment or Conceptual Change? In S. Carey and R. Gelman (Eds.), The Epigenesis of Mind: Essays on Biology and Cognition (pp. 257–291). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ «Cognitive Science | Brain and Cognitive Sciences».

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eric Margolis; Stephen Lawrence. «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab at Stanford University. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Joseph Goguen «»The logic of inexact concepts», Synthese 19 (3/4): 325–373 (1969).

- ^ a b c Margolis, Eric; Laurence, Stephen (2007). «The Ontology of Concepts—Abstract Objects or Mental Representations?». Noûs. 41 (4): 561–593. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.9995. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0068.2007.00663.x.

- ^ Jerry Fodor, Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong

- ^ a b c d e Carey, Susan (2009). The Origin of Concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536763-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Murphy, Gregory (2002). The Big Book of Concepts. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-13409-5.

- ^ McCarthy, Gabby (2018) «Introduction to Metaphysics». pg. 35

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Stephen Lawrence; Eric Margolis (1999). Concepts and Cognitive Science. in Concepts: Core Readings: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 3–83. ISBN 978-0-262-13353-1.

- ^ ‘Godel’s Rationalism’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Hampton, J.A. (1979). «Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 18 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(79)90246-9.

- ^ a b Brown, Roger (1978). A New Paradigm of Reference. Academic Press Inc. pp. 159–166. ISBN 978-0-12-497750-1.

- ^ a b c d e f TAYLOR, John R. (1989). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes In Linguistic Theory.

- ^ Murphy, Gregory L.; Medin, Douglas L. (1985). «The role of theories in conceptual coherence». Psychological Review. 92 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.92.3.289. ISSN 0033-295X. PMID 4023146.

- ^ Mroczko-Wä…Sowicz, Aleksandra; Nikoliä‡, Danko (2014). «Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 509. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00509. PMC 4137691. PMID 25191239.

- ^ Stevan Harnad (1995). Why and How We Are Not Zombies. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1: 164–167.

- ^ David Chalmers (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (3): 200–219.

- ^ Nikolić, D. (2009) Is synaesthesia actually ideaesthesia? An inquiry into the nature of the phenomenon. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Synaesthesia, Science & Art, Granada, Spain, April 26–29, 2009.

- ^ Gómez Milán, E., Iborra, O., de Córdoba, M.J., Juárez-Ramos V., Rodríguez Artacho, M.A., Rubio, J.L. (2013) The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia. The Journal of Consciousness Studies. 20(1–2): pp. 84–102.

- ^ Blouw, Peter; Solodkin, Eugene; Thagard, Paul; Eliasmith, Chris (2016). «Concepts as Semantic Pointers: A Framework and Computational Model». Cognitive Science. 40 (5): 1128–1162. doi:10.1111/cogs.12265. PMID 26235459.

- ^ «Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby». Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2011-11-25.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, S. L., Gleitman, L. R., & Gleitman, H. (1999). what some concepts might not be. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, Concepts (pp. 225–261). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Carey, S. (1999). knowledge acquisition: enrichment or conceptual change? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 459–489). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, J. A., Garrett, M. F., Walker, E. C., & Parkes, C. H. (1999). against definitions. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 491–513). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, Jerry; Lepore, Ernest (1996). «The red herring and the pet fish: Why concepts still can’t be prototypes». Cognition. 58 (2): 253–270. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00694-X. PMID 8820389. S2CID 15356470.

- Hume, D. (1739). book one part one: of the understanding of ideas, their origin, composition, connexion, abstraction etc. In D. Hume, a treatise of human nature. England.

- Murphy, G. (2004). Chapter 2. In G. Murphy, a big book of concepts (pp. 11 – 41). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Murphy, G., & Medin, D. (1999). the role of theories in conceptual coherence. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 425–459). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Prinz, Jesse J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3169.001.0001. ISBN 9780262281935.

- Putnam, H. (1999). is semantics possible? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 177–189). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Quine, W. (1999). two dogmas of empiricism. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 153–171). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Rey, G. (1999). Concepts and Stereotypes. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 279–301). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Rosch, E. (1977). Classification of real-world objects: Origins and representations in cognition. In P. Johnson-Laird, & P. Wason, Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp. 212–223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosch, E. (1999). Principles of Categorization. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 189–206). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Schneider, Susan (2011). «Concepts: A Pragmatist Theory». The Language of Thought. pp. 159–182. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262015578.003.0071. ISBN 9780262015578.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1999). philosophical investigations: sections 65–78. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 171–175). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development, Carl Benjamin Boyer, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- The Writings of William James, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39188-4

- Logic, Immanuel Kant, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- A System of Logic, John Stuart Mill, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume I, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience, H. J. Paton, London: Allen & Unwin, 1936

- Conceptual Integration Networks. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, 1998. Cognitive Science. Volume 22, number 2 (April–June 1998), pp. 133–187.

- The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1982, ISBN 0-14-015062-5

- Stephen Laurence and Eric Margolis «Concepts and Cognitive Science». In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press pp. 3–81, 1999.

- Hjørland, Birger (2009). «Concept theory». Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 60 (8): 1519–1536. doi:10.1002/asi.21082.

- Georgij Yu. Somov (2010). Concepts and Senses in Visual Art: Through the example of analysis of some works by Bruegel the Elder. Semiotica 182 (1/4), 475–506.

- Daltrozzo J, Vion-Dury J, Schön D. (2010). Music and Concepts. Horizons in Neuroscience Research 4: 157–167.

External links[edit]

Look up concept in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Concept at PhilPapers

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Concept at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- «Concept». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Theory–Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Classical Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blending and Conceptual Integration

- Concepts. A Critical Approach, by Andy Blunden

- Conceptual Science and Mathematical Permutations

- Concept Mobiles Latest concepts

- v:Conceptualize: A Wikiversity Learning Project

- Concept simultaneously translated in several languages and meanings

- TED-Ed Lesson on ideasthesia (sensing concepts)

Table of Contents

- What is the adjective form of concept?

- Is Concept an adjective?

- What is the adverb of concept?

- What are the 3 ways in explaining a concept?

- How do you explain a concept?

- What is Concept elucidation?

- What is a concept paragraph?

- What are good concepts to write about?

- How do you write a one word essay?

- What is a good topic?

- What to write when you are bored?

- What should I write about today?

- What to write when you dont know what to write?

- What do you write to someone you don’t know?

- What should I write about myself?

- What is the verb form of concept?

- Is concept a noun or adjective?

- Is concept a noun or verb?

- What is a concept example?

- What are the two types of concept?

- What are the types of concept?

- How do you explain an idea clearly?

- What’s another word for concept?

- What is the antonym of concept?

- What are the two simplest and commonest words in English?

- What is another word for ideas?

- What are the examples of ideas?

- What is a creative idea?

- How do you write an idea?

- What are some ideas to write about?

- What are interesting topics to write about?

- What are good topics to write about?

- What is the best topic for students?

- Which topic is best for project?

- What should I write daily?

- How do you start writing a habit?

- What is a good journal topic?

- What is an adverb and examples of an adverb?

- Where do adverbs go in a sentence?

- What type of adverb is down?

- Is faster a adverb?

- What type of speech is while?

- What is the verb form of while?

- How long is a while?

- What is a short while?

- What is a while in minutes?

- What does give me a bit mean?

- How do you use a while in a sentence?

- What do you mean by for a while?

A concept is a thought or idea. Concept was borrowed from Late Latin conceptus, from Latin concipere “to take in, conceive, receive.” A concept is an idea conceived in the mind. The original meaning of the verb conceive was to take sperm into the womb, and by a later extension of meaning, to take an idea into the mind.

What is the adjective form of concept?

conceptual. Of, or relating to concepts or mental conception; existing in the imagination. Of or relating to conceptualism.

Is Concept an adjective?

adjective. functioning as a prototype or model of new product or innovation: a concept car,a concept phone.

What is the adverb of concept?

conceivably. In a conceivable manner, possibly.

What are the 3 ways in explaining a concept?

1. Definition – It is a method of identifying a given term and making its meaning clearer: its main purpose is to clarify and explain concepts, ideas, and issues. Definition can be presented in 3 ways: informal, formal, or extended.

How do you explain a concept?

8 simple ideas for concept development and explanation

- Understand your audience.

- Define your terms.

- Classify and divide your concept into ‘chunks’

- Compare and contrast.

- Tell a story or give an example to illustrate the process or concept.

- Illustrate with examples.

- Show Causes or Effects.

- Compare new concepts to familiar ones.

What is Concept elucidation?

: to make lucid especially by explanation or analysis elucidate a text. intransitive verb. : to give a clarifying explanation.

What is a concept paragraph?

The conceptual paragraph is defined as a group of rhetorically related concepts developing a generalization to form a coherent and complete unit of discourse and consisting of one or more traditional physical paragraphs.

What are good concepts to write about?

Fictional Things To Write About

- 1 Get inspired by a song.

- 2 Reinvent a childhood memory.

- 3 Write about a person you see every day but don’t really know.

- 4 If your pet were a person . . .

- 5 Write about what you wanted to be when you grew up.

- 6 Grab a writing prompt to go.

How do you write a one word essay?

Your Task: Write an essay around a single word that defines your book.

- STEP ONE: Choose your word.

- STEP TWO: Look up the definition of the word.

- STEP THREE: Search for your word in the text.

- STEP FOUR: Look at your evidence and definitions and match them up.

- STEP FIVE: Write your essay.

What is a good topic?

A good topic sentence is specific enough to give a clear sense of what to expect from the paragraph, but general enough that it doesn’t give everything away. You can think of it like a signpost: it should tell the reader which direction your argument is going in.

What to write when you are bored?

Things to Write About When Bored – 365+ Writing Prompts

- A Movie Review. Did you recently watch a movie?

- Look Outside the Window. Look outside your window.

- List of Things You’ll Never Do Again.

- Traveling Story.

- Your Comfort Food.

- Love Letter.

- A Long Lost Friend.

- Eye Contact.

What should I write about today?

Things to Write About Today

- Write about what you love about your life right now.

- Write a list of words for each of your senses.

- Write about a lifestyle you can barely imagine.

- Write about spending a day in the house of your dreams.

- Write a world with no characters.

- Write an ode to the floor.

What to write when you dont know what to write?

So, here are eleven things to write about when you don’t know what to write about.

- Ask, ‘What’s hot right now?

- Teach readers how to do something.

- Steal from competitors.

- Read forums in your industry.

- Write a sequel to a previous popular post.

- Use a keyword planner.

- Write about your biggest mistake.

What do you write to someone you don’t know?

Ok, usually when writing an important letter to a person you don’t know (and you don’t know whether the person is a man or a woman) you should start your letter with: Dear Sir/Madam, or Dear Sir or Madam, If you know the name of the person you are writing to, always use their surname.

What should I write about myself?

26 Writing Prompts About Yourself

- What is something you are good at doing?

- What is your favorite color and why?

- What is the story behind your name?

- Which country do you want to visit and why?

- What is your favorite cartoon?

- What do you want to be when you grow up and why?

- What is your favorite thing about school?

What is the verb form of concept?

conceive. (transitive) To develop an idea; to form in the mind; to plan; to devise; to originate.

Is concept a noun or adjective?

noun. a general notion or idea; conception.

Is concept a noun or verb?

noun. noun. /ˈkɑnsɛpt/ an idea or a principle that is connected with something abstract concept (of something) the concept of social class concepts such as “civilization” and “government” He can’t grasp the basic concepts of mathematics.

What is a concept example?

In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing. For example, the word “moon” (a concept) is not the large, bright, shape-changing object up in the sky, but only represents that celestial object.

What are the two types of concept?

Two Kinds of Concept: Implicit and Explicit.

What are the types of concept?

In this lesson, we’ll explore what a concept is and the three general levels of concepts: superordinate, basic, and subordinate.

How do you explain an idea clearly?

10 ways to explain things more effectively

- #1: Keep in mind others’ point of view.

- #2: Listen and respond to questions.

- #3: Avoid talking over people’s head.

- #4: Avoid talking down to people.

- #5: Ask questions to determine people’s understanding.

- #6: Focus on benefits, not features.

- #7: Use analogies to make concepts clearer.

What’s another word for concept?

Some common synonyms of concept are conception, idea, impression, notion, and thought.

What is the antonym of concept?

Antonyms: actuality, fact, reality, substance. Synonyms: apprehension, archetype, belief, conceit, conception, design, fancy, fantasy, idea, ideal, image, imagination, impression, judgment, model, notion, opinion, pattern, plan, purpose, sentiment, supposition, theory, thought.

What are the two simplest and commonest words in English?

Top 100 words

| Rank | Word |

|---|---|

| 1 | the |

| 2 | be |

| 3 | to |

| 4 | of |

What is another word for ideas?

Some common synonyms of idea are conception, concept, impression, notion, and thought.

What are the examples of ideas?

The definition of an idea is a thought, belief, opinion or plan. An example of idea is a chef coming up with a new menu item. An opinion or belief. Something, such as a thought or conception, that is the product of mental activity.

What is a creative idea?

A creative idea is the result of two or more notions coming together in the mind in order to create an all new notion; a creative idea, which in turn becomes a useful notion for future creative ideas.

How do you write an idea?

Write down your ideas as fast as possible. Find the essence of your content. Revise your content to build on your key idea. Edit sentence by sentence.

What are some ideas to write about?

What are interesting topics to write about?

Narrative Writing

- A cozy spot at home.

- A day at the beach.

- A day in the desert.

- A funny time in my family.

- A great day with a friend.

- A great place to go.

- A great treehouse.

- A helpful person I have met.

What are good topics to write about?

Interesting Topics to Write About

- Identify a moment in your life that made you feel like you had superpowers.

- How have you handled being the “new kid” in your lifetime?

- When you’re feeling powerful, what song best motivates you?

- What is your spirit animal?

- Dear Me in 5 Years…

- How has water impacted your life?

What is the best topic for students?

Essay Topics for Students from 6th, 7th, 8th Grade

- Noise Pollution.

- Patriotism.

- Health.

- Corruption.

- Environment Pollution.

- Women Empowerment.

- Music.

- Time and Tide Wait for none.

Which topic is best for project?

The Best Capstone Project Topic Ideas

- Information Technology.

- Computer Science.

- MBA.

- Accounting.

- Management.

- Education.

- Engineering.

- Marketing.

What should I write daily?

Recap: 6 Journaling Ideas

- Write down your goals every day.

- Keep a daily log.

- Journal three things you’re grateful for every day.

- Journal your problems.

- Journal your stresses.

- Journal your answer to “What’s the best thing that happened today?” every night before bed.

How do you start writing a habit?

How to Develop a Daily Writing Habit in 10 Steps

- First, set up a writing space.

- Start each day by journaling.

- Set a word count goal.

- Set aside writing time every single day, without exception.

- Don’t start with a blank page if you can help it.

- Include brainstorming sessions in your writing process.

What is a good journal topic?

Ok, without further ado, here are those topics for journaling writers of all ages!…Topics for Journal Writing

- What is the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?

- Have you ever been in love?

- What is the hardest truth you’ve ever learned?

- What is your greatest dream in life?

- Does history repeat itself?

What is an adverb and examples of an adverb?

An adverb is a word that modifies (describes) a verb (he sings loudly), an adjective (very tall), another adverb (ended too quickly), or even a whole sentence (Fortunately, I had brought an umbrella). Adverbs often end in -ly, but some (such as fast) look exactly the same as their adjective counterparts.

Where do adverbs go in a sentence?

middle

What type of adverb is down?

Down can be used in the following ways: as a preposition (followed by a noun): She was walking down the street. as an adverb (without a following noun): She lay down and fell asleep. after the verb ‘to be’: Oil prices are down.

Is faster a adverb?

Faster can be a noun, an adverb or an adjective.

What type of speech is while?

While is a word in the English language that functions both as a noun and as a subordinating conjunction.

What is the verb form of while?

whiled; whiling. Definition of while (Entry 4 of 4) transitive verb.

How long is a while?

The study has discovered “a while” estimates a length of 4 months whereas “a little while” would be a little less at 3 months’ time. Going a little further, “a while back” would indicate the potential of occurring up to 8 months in the past.

What is a short while?

adjective. If something is short or lasts for a short time, it does not last very long.

What is a while in minutes?

For a 13-year-old male, we found a while would vary from 25 seconds to about 40 seconds. For a 30-year-old mother of four, we found that a while was just about 45 minutes.

What does give me a bit mean?

Give me a bit is informal or casual way of saying “give me some time” or “give me extra time”

How do you use a while in a sentence?

Example Sentences

- I will be able to sit with you for a while, but I need to get home soon.

- You can stay with us for a while until you are back on your feet.

- He stayed with them awhile.

- Please sit awhile, we will be leaving for the movie very soon.

- We also stayed in Japan for a while during our trip to China.

What do you mean by for a while?

Adv. 1. for a while – for a short time; “sit down and stay awhile”; “they settled awhile in Virginia before moving West”; “the baby was quiet for a while” awhile.

For those interested in a little info about this site: it’s a side project that I developed while working on Describing Words and Related Words. Both of those projects are based around words, but have much grander goals. I had an idea for a website that simply explains the word types of the words that you search for — just like a dictionary, but focussed on the part of speech of the words. And since I already had a lot of the infrastructure in place from the other two sites, I figured it wouldn’t be too much more work to get this up and running.

The dictionary is based on the amazing Wiktionary project by wikimedia. I initially started with WordNet, but then realised that it was missing many types of words/lemma (determiners, pronouns, abbreviations, and many more). This caused me to investigate the 1913 edition of Websters Dictionary — which is now in the public domain. However, after a day’s work wrangling it into a database I realised that there were far too many errors (especially with the part-of-speech tagging) for it to be viable for Word Type.

Finally, I went back to Wiktionary — which I already knew about, but had been avoiding because it’s not properly structured for parsing. That’s when I stumbled across the UBY project — an amazing project which needs more recognition. The researchers have parsed the whole of Wiktionary and other sources, and compiled everything into a single unified resource. I simply extracted the Wiktionary entries and threw them into this interface! So it took a little more work than expected, but I’m happy I kept at it after the first couple of blunders.

Special thanks to the contributors of the open-source code that was used in this project: the UBY project (mentioned above), @mongodb and express.js.

Currently, this is based on a version of wiktionary which is a few years old. I plan to update it to a newer version soon and that update should bring in a bunch of new word senses for many words (or more accurately, lemma).

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

The term «concept» has entered the conceptual apparatus of cognitive science, semantics, linguoculturology. The period of approval of the term in science is necessarily associated with a certain blurring of boundaries, the arbitrariness of its use, mixing with terms that are close in meaning and/or language form [1].

Currently, there is no clear and precise definition of the term «concept», since it covers several areas at once: cognitive science, semantics and linguoculturology. This term is similar to other similar terms in language form. The main task is to give a precise and clear definition that would include all aspects of the term «concept».

There are many points of view on what a concept is.

The well-known linguist S. A. Askoldov defines it as a mental formation that replaces an indefinite set of objects of the same kind in the process of thought [2]. According to S. A. Askold, the concept can be a substitute for some aspects of the subject or real actions, such as the concept of «justice», and can also be a substitute for various kinds of at least very precise, but purely mental functions. These are, for example, mathematical concepts [3]. S. A. Askoldov focuses his attention on the fact that the substitutive role of concepts in the field of thought, in General, coincides in its purpose and meaning with various kinds of substitutive functions in the field of real life relations, and there are a lot of such substitutions in the life sphere [4]. The scientist talks a lot about the nature of cognitive concepts. Figuratively speaking, he says about the concept that these are the buds of the most complex inflorescences of mental concreteness [5]. It should also be mentioned about the concept of cognition. S. A. Askoldov argues that the concept of cognition is always related to some multiple objectivity-ideal or real [6]. He defines the word as an organic part of the concept [7].

Other scientists give different definitions.

Such well-known scientists as Z. D. Popova and I. A. Sternin define the concept as » a discrete mental formation that is the basic unit of the human thought code, has a relatively ordered internal structure, is the result of cognitive (cognitive) activity of the individual and society and carries complex, encyclopedic information about the reflected object or phenomenon, the interpretation of this information by public consciousness and the attitude of public consciousness to this

phenomenon or object» [8].R. M. Frumkina notes that the concept is the object of conceptual analysis, the meaning of which is «to trace the path of cognition of the meaning of the concept and write the result in a formalized semantic language» [9]. Conceptual analysis is research for which the concept is the object of analysis. The meaning of conceptual analysis is essentially knowledge of the concept, i.e. the concept is knowledge about an object from the world of reality. A. p. Babushkin in the monograph » Types of concepts in lexical and phraseological semantics

language » considers concepts as structures of knowledge representation. He understands the concept «as any discrete content unit of collective consciousness, reflecting the object of the real or ideal world, stored in the national memory of native speakers in the form of a recognized substrate. The concept is verbalized, denoted by a word, otherwise its existence is impossible» [10].

«Concept» and «concept» are not equal, as V. N. Telia notes in his works. She believes that » the change of the term «concept» to the term «concept»is not just a terminological replacement: a concept is always knowledge structured in a frame, which means that it reflects not just the

essential features of the object, but all those that are filled with knowledge about the essence in a given language team.» «Concepts, stereotypes, standards, symbols, mythologems, etc. – signs of national and – more broadly-universal culture» [11].

His explanation of the terms «concept» and «concept» and gave Yu. s. Stepanov, who believes that the concept and notion of the terms of different Sciences; the concept is used mainly in logic and philosophy, and the term «concept» as a term in mathematical logic, in the last

time entrenched in the science of culture, in cultural studies .

Yu. s. Stepanov, while considering the concept as a fact of culture, identifies three components, or three «layers» concept:

1) the main, actual feature;

2) additional, or several additional, «passive» signs that are

already irrelevant, » historical»;

3) an internal form, usually not at all conscious, imprinted in an external, verbal form [13].

In modern research, the analysis of the concept of» concept » is conducted in two directions:

1. on the epistemology of the concept (from the point of view of the origin of the concept and its «location», as well as its relationship with reality and forms of its manifestation).

2. on the typology of concepts (from the point of view of a certain science (discipline), taking into account its conceptual apparatus and its needs in this term).

The concept is a mental unit, an element of consciousness. Human consciousness is the intermediary between the real world and language. The consciousness receives cultural information, it is filtered, processed, systematized: «Concepts form ‘a kind of cultural layer mediating between man and the world’ «[4].

According to V. V. Kolesov, «concept grain permasmile, semantic «fetus» word»; «Concept and therefore becoming a reality racemase, figuratively this word that really exists, just as there is language, the phoneme, the morpheme and the other, already identified by science «noumena» plan of content, for every culture is vital. A concept is something that is not subject to change in the semantics of a word sign, which, on the contrary, directs the thought of speakers of a given language, determining their choice and creating the potential possibilities of language-speech.»

And unlike image, symbol, concept «concept is not expanded in any question, for it was he – and the starting point, and the completion of the process at a new level of semantic development in the language; it is the source of universal meaning that is available in multiple forms and values».

To describe the concept word in sociopolitical discourse, first of all, it is necessary to use complex lexicography based on the data of more than one dictionary, with the obligatory involvement of the latest dictionaries. As noted by A. G. Berdnikova, «dictionary of the description of lexical units

they refer to the language picture of the world, they describe the building blocks from which the language picture of the world, in fact, is formed. They reflect the linguistic mentality of native speakers of a particular natural language.» But «explanatory dictionaries partly show the degree of representation of the concept in the minds of native speakers: what is the set, the hierarchy of semantic components that they consist of» [5].

The following structure is proposed By S. G. Vorkachev. It identifies the composition of the linguocultural concept three components: conceptual, reflecting his traits and definitionsfactory, shaped, fixing cognitive metaphors that support the concept in the linguistic consciousness, and znachimostnoy-defined location, which takes the name of a concept in lexical and grammatical system of a particular language, which will also include its etymological and associative characteristics .

According To V. I. Karasik, the concept consists of three components – conceptual, figurative and value . He believes that the cultural concept in the language consciousness is a multidimensional network of meanings that are expressed by lexical, phraseological, paremiological units, precedent texts, etiquette formulas, as well as speech-behavioral tactics that reflect repeated fragments of social life.

Meaning is, according To G. p. Shchedrovitsky, «the General correlation and connection of all phenomena related to the situation» [8]. It is always situational, conditioned by context, belongs to speech and is primary in relation to meaning, which, in turn, is non-contextual, non-situational, belongs to language, is derived from meaning, is socially institutionalized and formulated, in contrast to the meanings created by everyone and everyone, exclusively by compilers of dictionaries [10].

In «Linguistic encyclopedic dictionary» the term «concept» vocabulary independent article are not presented, but the value is disclosed in the article «Concept» and «concept» as a synonym marked with a number in parentheses: «the Concept (concept) is a phenomenon of the same order, what is the meaning of the word, but seen in a slightly different system of relations; the value in the language system, the concept – in the system of logical relations and forms, as studied in linguistics and in logic» [11].

Activity of the individual and society and carrying complex, encyclopedic information about the reflected object or phenomenon, about the interpretation of this information by the public consciousness and the attitude of public consciousness to this phenomenon or object.

This definition is very voluminous. Therefore, we will adhere to the point of view of S. A. Askold, who understands the concept as a mental formation that replaces an indefinite set of objects of the same kind in the process of thought.

So, summing up all of the above, we came to the following conclusions:

The terms «concept» and» concept » are not identical.

The term «concept» is used mainly in logic and philosophy.

The concept is a unit of collective consciousness that sends to the highest spiritual values, has a linguistic expression and is marked by ethno-cultural specifics.

REFERENCES

Karasik V. I. YAzykovoj krug: lichnost’, koncepty. Diskurs [Language circle: personality, concepts. Discourse]. M. Gnosis. 2004. P. 75.

Askoldov S. A. Koncept i slovo [Concept and the word]// Russkaya slovesnost’. Ot teorii slovesnosti k strukture teksta. Antologiya – Russian literature. From theory of literature to the structure of the text. The anthology / under the editorship of V. P. Neroznak. M. Academia 1997. P. 269.

Popova Z. D., Sternin I. A. Semantiko-kognitivnyj analiz yazyka [Semantic-cognitive analysis of language]. Voronezh. 2006. P. 24.

Frumkina R. M. Konceptual’nyj analiz s tochki zreniya lingvista i psihologa [Conceptual analysis from the point of view of the linguist and psychologist] // Nauchno-tekhnicheskaya informaciya – Scientific and technical information. 1992. Ser. 2. No. 3

Babushkin A. P. Tipy konceptov v leksiko-frazeologicheskoj semantike yazyka, ih lichnostnaya i nacional’naya specifika [Types of concepts in lexico-phraseological semantics of the language, their personal and national features]. Voronezh. 2006. P. 29.

Stepanov Y. S. Konstanty: slovar’ russkoj kul’tury [Constants: dictionary of Russian culture]. M. «Academic project». 2001. P. 43.

Arutyunova N. D. Vvedenie [Introduction] // Logicheskij analiz yazyka. Mental’nye dejstviya – Logic analysis of language. Mental steps. M. Nauka. 1993. Pp. 3-6.

Shchedrovitsky G. P. Smysl i znachenie [Meaning and significance]// Shchedrovitsky G. P. Selected works. M. 1995. Pp. 546-576.

Vorkachev S. G. Bezrazlichie kak ehtnosemanticheskaya harakteristika lichnosti: opyt sopostavitel’noj paremiologii [Indifference as ethnosemantic characteristic of the individual: the experience of comparative paremiology] // VYA. 1997, No. 4, pp. 115-124.

Demyankov V. Z. Ponyatie i koncept v hudozhestvennoj literature i v nauchnom yazyke [Notion and concept in literature and in scientific language] // Voprosy filologii – Questions of Philology. 2001, No. 1, pp. 35– 47.

Kolesov V. V. Filosofiya russkogo slova [Philosophy of Russian words]. St. Petersburg. 2002. Pp. 50-51

-

The grammatical meaning

-

The lexical meaning.

They

are found in all words.

The

interrelation of these 2 types of meaning may be different in

different groups of words.

GRAMMATICAL

M-NG:

We

notice, that word-forms, such as: girls,

winters, joys, tables,

etc. though denoting widely different objects of reality have

something in common. This common element is the

grammatical meaning of plurality, which

can be found in all of them.

Gram.

m-ng may be defined as the component of meaning recurrent in

identical sets of individual form of different words, as, e.g., the

tense meaning in the word-forms of verb (asked,

thought, walked,

etc) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s,

boy’s,

night’s,

etc).

In

a broad sense it may be argued that linguists, who make a distinction

between lexical and grammatical meaning are, in fact, making a

distinction between the functional [linguistic] meaning, which

operates at various levels as the interrelation of various linguistic

units and referential [conceptual] meaning as the interrelation of

linguistic units and referents [or concepts].

In

modern linguistic science it is commonly held that some elements of

grammatical meaning can be identified by the position of the

linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units, i.e. by its

distribution. Word-forms speaks,

reads, writes

have one and the same grammatical meaning as they can all be found in

identical distribution, e.g. only after the pronouns he,

she, it

and before adverbs like well,

badly, to-day,

etc.

It

follows that a certain component of the meaning of a word is

described when you identify it as a part of speech, since different

parts of speech are distributionally different.

{

the grammatical m-hg will be different for different forms of 1 word

and vice verse, various verbs may have 1 gr. m-ng}

LEXICAL

M-NG:

Comparing

word-forms of one and the same word we observe that besides gram.

meaning, there is another component of meaning to be found in them.

Unlike the gram. m-ng this component is identical in all the forms of

the word. Thus, e.g. the word-forms go,

goes,

went,

going, gone

possess different gram. m-ng of tense, person and so on, but in each

of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting

the process of movement. This is the lexical m-ng of the word, which

may be described as the component of m-ng proper to the word as a

linguistic unit, i.e. recurrent in all the forms of this word.

The

difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of

meaning is not to be sought in the difference of the concepts

underlying the 2 types of meaning, but rather in the way they are

conveyed. The concept of plurality, e.g., may be expressed by the

lexical m-ng of the word plurality;

it

may also be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of

their lexical m-ng, e.g.

boys, girls, joys,

etc. The concept of relation may be expressed by the lexical m-ng of

the word relation

and also by any of prepositions, e.g.

in, on, behind,

etc. ( the

book is in/on,

behind

the table ).

It

follows that by lexical m-ng we designate the m-ng proper to the

given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions, while by

grammatical m-ng we designate the m-ng proper to sets of word-forms

common to all words of a certain class. Both the lexical and the

grammatical m-ng make up the word-meaning as neither can exist

without the other.

Lex.

m-ng is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including the

number of aspects. We define 3 aspects:

-

denotational

-

сonnotational

-

pragmatic

aspects.

a)

It is that part of lex. m-ng, the function of which is to name the

thing, concepts or phenomenon which it denotes. It’s the component

of L. m-ng, which establishes correspondence between the name and the

object. (den. m-ng – that component which makes communication

possible).

e.g.

Physict knows more about the atom than a singer does, or that an

arctic explorer possesses a much deeper knowledge of what artic ice

is like than a man who has never been in the North. Nevertheless they

use the words atom,

Artic,

etc. and understand each other.

It

insures reference to things common to all the speakers of given

language.

b)

The second component of the l. m-ng comprises the stylistic reference

and emotive charge proper to the word as a linguistic unit in the

given language system. The connot. component – emotive charge and

the stylistic value of the word. It reflects the attitude of the

speaker towards what he is speaking about. This aspect belongs to the

language system.

c)

Prag. aspect – that part of the L. m-ng, which conveys information

on the situation of communication.

It

can be divided into:

—

inf-ion on the time and space relationship of communication.

Some

inf-ion may be conveyed through the m-ng of the word itself.

To

come – to go [space relationship]

To

be hold – 17th

cent [time relationship]

—

inf-ion on the participant of communication or on this particular

language community.

e.g.

They chuked a stone at the cops’ and then did a bunk with the

loot. [ criminal speaking]

After

casting a stone at the police they escaped with the money. [ chief

inspector speaking]

—

inf-ion on the character of discourse [social or family codes]

e.g.

stuff – rubbish

(

Stuff — it’ll hardly be used by strangers, by smb. talking to

boss)

—

inf-ion on the register of communication.

e.g.

com-ion : — formal (to anticipate, to aid, cordoal)

—

informal (stuff, shut up, cut it off)

—

neutral ( you must be kidding) – ?

Meaning

is a certain reflection in our mind of objects, phenomena or

relations that makes part of the linguistic sign —

its

so-called inner facet, whereas the sound-form functions as its outer

facet.

Grammatical

meaning

is defined as the expression in Speech of relationships between

words. The grammatical meaning is more abstract and more generalised

than the lexical meaning. It is recurrent in identical sets of

individual forms of different words as the meaning of plurality in

the following words students,

boob, windows, compositions.

Lexical

meaning.

The definitions of lexical meaning given by various authors, though

different in detail, agree in the basic principle: they all point out

that lexical meaning is the realisation of concept or emotion by

means of a definite language system.

-

The

component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i.e.

recurrent in all the forms of this word and in all possible

distributions of these forms. /

Ginzburg

R.S., Rayevskaya N.N. and others. -

The

semantic invariant of the grammatical variation of a word / Nikitin

M.V./. -

The

material meaning of a word, i.e. the meaning of the main material

part of the word which reflects the concept the given word expresses

and the basic properties of the thing (phenomenon, quality, state,

etc.) the word denotes. /Mednikova E.M./.

Denotation.

The conceptual content of a word is expressed in its denotative

meaning. To denote is to serve as a linguistic expression for a

concept or as a name for an individual object. It is the denotational

meaning that makes communication possible.

Connotation

is the pragmatic communicative value the word receives depending on

where, when, how, by whom, for what purpose and in what

contexts

it may be used. There are four main types of connotations stylistic,

emotional, evaluative and expressive or intensifying.

Stylistic

connotations is what the word conveys about the speaker’s attitude to

the social circumstances and the appropriate functional style (slay

vs

kill),

evaluative

connotation may show his approval or disapproval of the object spoken

of

(clique vs

group),

emotional

connotation conveys the speaker’s emotions (mummy

vs

mother),

the

degree of intensity (adore

vs

love)

is

conveyed by expressive or intensifying connotation.

The

interdependence of connotations with denotative meaning is also

different for different types of connotations. Thus, for instance,

emotional connotation comes into being on the basis of denotative

meaning but in the course of time may substitute it by other types of

connotation with general emphasis, evaluation and colloquial

stylistic overtone. E.g. terrific

which

originally meant ‘frightening’ is now a colloquialism meaning ‘very,

very good’ or ‘very great’: terrific

beauty, terrific pleasure.

The

orientation toward the subject-matter, characteristic of the

denotative meaning, is substituted here by pragmatic orientation

toward speaker and listener; it is not so much what is spoken about

as the attitude to it that matters.

Fulfilling

the significative

and the communicative functions

of the word the denotative meaning is present in every word and may

be regarded as the central factor in the functioning of language.

The

expressive function

of the language (the speaker’s feelings) and the pragmatic

function

(the effect of words upon listeners) are rendered in connotations.

Unlike the denotative meaning, connotations are optional.

Connotation

differs from the

implicational meaning

of the word. Implicational meaning is the implied information

associated with the word, with what the speakers know about the

referent. A wolf is known to be greedy and cruel (implicational

meaning) but the denotative meaning of this word does not include

these features. The denotative

or the intentional meaning of the

word wolf

is

«a

wild animal resembling a dog that kills sheep and sometimes even

attacks men». Its figurative meaning is derived from implied

information, from what we know about wolves —

«a

cruel greedy person», also the adjective wolfish means «greedy».

Билет

№ 15. (Полисемия.

Понятие семантической структуры слова)

Polysemy

is characteristic of most words in many languages, however different

they may be. But it is mere characteristic of the English voc-ry as

compared with Russian, due to the monosyllabic character of English

and the predominance of root words. Only few words in English have

one meaning except terms (oxygen). All the other words in are

polysemantic, i.e. have more than one meaning. The tendency here

works both ways. The more widely a word is used, the more meanings it

has to have (to go – 70 meanings). Different meanings of a

polysemantic word make up the lexical semantic

structure of a word.

The meanings themselves are called the lexical semantic variants of a

word. It’s not just a list of lexical semantic meanings. There is a

special correspondence between the meanings of one and the same word.

The correlation between the meanings corresponds to one of the same

sound-form and forms a unity of meanings which is known as a semantic

structure of a word.

Polysemy

is very characteristic of the English vocabulary due to the

monosyllabic character of English words and the predominance of root

words The greater the frequency of the word, the greater the number

of meanings that constitute its semantic structure. Frequency —

combinability

—

polysemy

are closely connected. A special formula known as «Zipf’s

law» has been worked out to express the correlation between

frequency, word length and polysemy: the shorter the word, the higher

its frequency of use; the higher the frequency, the wider its

combinability ,

i.e.

the more word combinations it enters; the wider its combinability,

the more meanings are realised in these contexts.

The

word in one of its meanings is termed a

lexico-semantic

variant

of this word. For example the word table

has

at least 9

lexico-semantic

variants:

1

A

piece of furniture

2.

The

persons seated at table

3.

The food put on a table

-

A

thin flat piece of stone, metal, wood -

A

slab of stone -

Plateau,

extensive area

of

high land -

An

orderly arrangement of facts, etc.

The

problem in polysemy is that of interrelation of different

lexico-semantic variants. There may be no single semantic component

common to all lexico-semantic variants but every variant has

something in common with at least one of the others.

All

the lexico-semantic variants of a word taken together form its

semantic

structure or semantic paradigm.

The

word

face, for

example, according to the dictionary data has the following semantic

structure:

-

The

front part of the head: He

fell on his face, -

Look,

expression: a

sad face, smiling faces, she is a good judge of faces. -

Surface,

facade:.face

of a clock, face of a building, He laid his cards face down. -

fig.

Impudence, boldness, courage; put

a good/brave/ boldface on smth, put a new face on smth, the face of

it, have the face to do,

save

one’s face. -

Style

of typecast for printing: bold-face

type.

In

polysemy we are faced with the problem of interrelation and

interdependence of various meanings in the semantic structure of one

and the same word.

No

general or complete scheme of types of lexical meanings as elements

of a word’s semantic structure has so far been accepted by linguists.

There are various points of view. The following terms may be found

with different authors: direct /

figurative,

other oppositions are: main /

derived;

primary /

secondary;

concrete/ abstract; central/ peripheral; general/ special; narrow /

extended

and so on.

Meaning

is direct

when it nominates the referent without the help of a context, in

isolation; meaning is figurative

when the referent is named and at the same time characterised through

its similarity with other objects, e.g. tough

meat —

direct

meaning, tough

politician —

figurative

meaning. Similar examples are: head

—

head

of a cabbage, foot -foot of a mountain, face —

put

a new face on smth

Differentiation

between the terms primary

/

secondary

main /

derived

meanings

is connected with two approaches to polysemy: diachronic

and synchronic. ‘

If

viewed diachronically

polysemy, is understood as the growth and development (or change) in

the semantic structure of the word.

The

meaning the word table

had

in Old English is the meaning «a flat slab of stone or wood».

It was its primary meaning, others were secondary and appeared

later. They had been derived from the primary meaning.

Synchronically

polysemy is understood as the coexistence of various meanings of the

same word at a certain historical period of the development of the

English language. In that case the problem of interrelation and

interdependence of individual meanings making up the semantic

structure of the word must be investigated from different points of

view, that of main/ derived, central /peripheric meanings.

An

objective criterion of determining the main or central meaning is

the frequency of its occurrence in speech. Thus, the main meaning of

the word table

in

Modern English is «a piece of furniture».

Polysemy

is a phenomenon of language, not of speech. But the question arises:

wouldn’t it interfere with the communicative process ?

As

a rule the contextual meaning represents only one of the possible

lexico-semantic variants of the word. So polysemy does not interfere

with the communicative function of the language because the

situation and the context cancel all the unwanted meanings, as in

the following sentences: The

steak is tough This is a tough problem Prof. Holborn is a tough

examiner.

Билет

№ 16. (Семантическая

структура слова в синхронном и диахронном

рассмотрении)

If

polysemy

is viewed diachronically,

it is understood as the growth and development of or, in general, as

a change in the semantic structure of the word. Polysemy in

diachronic terms implies that a word may retain its previous meaning

or meanings and at the same time acquire one or several new

ones. In the course of a diachronic semantic analysis of the

polysemantic word table we find that of all the meanings it has in

Modern English, the primary meaning is ‘a flat slab of stone or