The modal verbs shall and will usually combine the meanings with that of futurity.

I will give you this money.

Я охотно дам тебе эти деньги.

You shan’t be without notes.

Не останешься ты без конспектов.

The modal verbs shall and will can be regarded as modal verbs when they are used not according to the general rules. That is, when they are used with a wrong person or in adverbial clauses of time and condition where no future tenses can be used.

The modal verb will

The modal verb will can express:

-

Wish or resolution to perform an action.

If you will come to my place, I will show you my books.

Если вы пожелаете зайти ко мне, я обязательно покажу вам свои книги. -

Obstinacy in performing an action in the present (will loses its meaning of future here).

I ask her not to call me this name but she will do it.

Я просил ее не звонить мне, но она продолжает это делать.

The modal verb would

There are several models where would is used as a modal verb:

-

In negative sentences in the Indicative mood would can be used as a modal verb expressing wish not to perform an action in the past.

He would not answer my questions.

Он упорно не желал отвечать на мои вопросы. -

In conditional sentences in the Subjunctive mood would can be used as a modal verb expressing wish or resolution to perform an action when it is used not according to the general rules. That is in the subordinate clause or in the principal close with the first person.

If you would come to my place I would show my books.

Если ты придешь ко мне, я обязательно покажу тебе мои книги.If the Soviets would give the necessary diplomatic privilege to Mr. L, we would do the same for Litvinov.

Если бы советы дали бы необходимые дипломатические привелегии господину L, мы бы обязательно сделали то же самое для Литвинова. -

The modal verb would can be used in the Indicative mood to express obstinacy in performing an action in the past.

I asked her not to bang the door but she would do it.

Я просил ее не хлопать дверью, но она все равно делает это.Note: With lifeless things this would expresses impossibility to perform an action with object.

The door would not open.

Дверь никак не открывалась.

The modal verb shall

The modal verb shall can be regarded as a modal verb when it is used not according to the general rules. That is with the wrong person (with the second or third) or in adverbial clauses of time and condition.

-

The modal verb shall expresses moral obligation and is often used in emotional disputes.

— Get up, little one. It’s time to go to school.

— I won’t go to school.

— You shall go.— Вставай малыш. Пора идти в школу.

— Но я совсем не хочу идти в школу.

— Ты должен идти.— We won’t take part in this war, sir.

— You shall, or you will be hanged.— Мы совсем не хотим участвовать в этой войне, сир.

— Вы должны или будете повешены. -

The modal verb shall is also regarded as a modal verb expressing obligations in questions addressed to the first person because such questions are unlikely to be regarded as normal questions in the Future Indefinite.

Shall I give you his telephone number?

Дать тебе его телефонный номер? -

The modal verb shall with the II and III person can also express promise.

You shall have a fine dress, Cinderella, you shall go to the ball.

У тебя будет красивое платье, ты поедешь на бал.

This article in Russian

Asked by: Dr. Candace Schamberger

Score: 4.9/5

(42 votes)

Definition. As a modal auxiliary verb, will is particularly versatile, having several different functions and meanings. It is used to form future tenses, to express willingness or ability, to make requests or offers, to complete conditional sentences, to express likelihood in the immediate present, or to issue commands …

Is Will an auxiliary verb?

Auxiliary Verbs «Will/Would» and «Shall/Should» The verbs will, would, shall, should, can, could, may, might, and must cannot be the main (full) verbs alone. They are used as auxiliary verbs only and always need a main verb to follow.

Is Will a modal or auxiliary verb?

In Oxford dictionary there’s no «will» as an auxiliary verb, there’s only «will» as a modal verb. Oxford’s definition of MODAL VERB: An auxiliary verb that expresses necessity or possibility. English modal verbs include must, shall, will, should, would, can, could, may, and might.

Is Will a primary auxiliary verb?

The three primary auxiliary verbs are ‘be’, ‘have’ and ‘do’. There are ten common modal auxiliary verbs and they are ‘can’, ‘could’, ‘will’, ‘would’, ‘shall’, ‘should’, ‘may’, ‘might’, ‘must’ and ‘ought’.

What are the 24 auxiliary verbs?

be, can, could, dare, do, have, may, might, must, need, ought, shall, should, will, would. The status of dare (not), need (not), and ought (to) is debatable and the use of these verbs as auxiliaries can vary across dialects of English.

29 related questions found

What are the main auxiliary verbs?

The main auxiliary verbs are to be, to have, and to do. They appear in the following forms: To Be: am, is, are, was, were, being, been, will be. To Have: has, have, had, having, will have.

What is the difference between helping verb and auxiliary verb?

Auxiliary verbs are sometimes called HELPING VERBS. This is because they may be said to «help» the main verb which comes after them. For example, in The old lady is writing a play, the auxiliary is helps the main verb writing by specifying that the action it denotes is still in progress.

What is the difference between auxiliary verb and full verb?

The main verb and auxiliary verb are important parts of a sentence. The main verb is a verb that expresses an action. … It can be said that the main verb gives the basic meaning of an action whereas the auxiliary verb expresses the time of the action such when the action occurred, occurs or will occur.

Is auxiliary verb sentence?

An auxiliary verb “helps” the main verb of the sentence by adding tense, mood, voice, or modality to the main verb. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone in sentences; they have to be connected to a main verb to make sense.

How do you use auxiliary verbs?

Auxiliary (or Helping) verbs are used together with a main verb to show the verb’s tense or to form a negative or question. The most common auxiliary verbs are have, be, and do. Does Sam write all his own reports? The secretaries haven’t written all the letters yet.

How do you use auxiliary verbs in a sentence?

The following examples show these verbs used as auxiliary verbs.

- » Be» as an auxiliary verb. a. Used in progressive sentences: I am taking a bath. She is preparing dinner for us. …

- » Do» as an auxiliary verb. a. Used in negative sentences: I do not know the truth. …

- » Have» as an auxiliary verb.

How many types of modal auxiliary verbs are there?

There are nine modal auxiliary verbs: shall, should, can, could, will, would, may, must, might. There are also quasi-modal auxiliary verbs: ought to, need to, has to.

Should auxiliary verb examples?

For instance: “I think she should pay for half the meal.” (obligation) “I think she is supposed to pay for half the meal.” (expectation) “I think she is meant to pay for half the meal.” (expectation)

What is the auxiliary verb will used for?

Definition. As a modal auxiliary verb, will is particularly versatile, having several different functions and meanings. It is used to form future tenses, to express willingness or ability, to make requests or offers, to complete conditional sentences, to express likelihood in the immediate present, or to issue commands …

What are the 23 of auxiliary verbs?

Helping verbs, helping verbs, there are 23! Am, is, are, was and were, being, been, and be, Have, has, had, do, does, did, will, would, shall and should. There are five more helping verbs: may, might, must, can, could!

What words are auxiliary verbs?

List of auxiliary verbs

- be (am, are, is, was, were, being),

- can,

- could,

- do (did, does, doing),

- have (had, has, having),

- may,

- might,

- must,

What is the difference between auxiliary verb and verb to be?

Well..a( verb to be) is to give information about the intended person or thing concerning its character or place. EX:We are here, but Ali is sick,they were teachers .. here(are,is,were) functioned as verbs to be ..an auxiliary verb is the one used to recognise the tenses of the sentences.

What is auxiliary verb easy?

grammar. : a verb (such as have, be, may, do, shall, will, can, or must) that is used with another verb to show the verb’s tense, to form a question, etc.

What is the difference between auxiliary verb and models?

Main Difference – Modal vs Auxiliary Verbs

Modal verbs are a type of auxiliary verbs that indicate the modality. The main difference between modal verbs and auxiliary verbs is that modal verbs are not subject to inflection whereas auxiliary verbs change according to tense, case, voice, aspect, person, and number.

What are the three primary auxiliary verbs?

English has three primary auxiliary verbs: do, be, and have. All three take part in the formation of various grammatical constructions, but carry very little meaning themselves. For example, the primary auxiliary be is used to form the progressive, as in: Bill is dancing.

What are the 27 auxiliary verbs?

Following are modal auxiliary verbs: Can, could, may, might, must, ought to, shall, should, will, would, dare, need, ought, etc.

…

List of Auxiliary Verbs

- Have (includes has, have, had, and having)

- Do (includes does, do, and did)

- Be (includes am, is, are, was, were, being and been)

What is the synonym of auxiliary?

auxiliary. Synonyms: helpful, abetting, aiding, accessory, promotive, conducive, assistant, ancillary, assisting, subsidiary, helping.

«Would» redirects here. For a song by Alice in Chains, see Would?

The English modal verbs are a subset of the English auxiliary verbs used mostly to express modality (properties such as possibility, obligation, etc.).[1] They can be distinguished from other verbs by their defectiveness (they do not have participle or infinitive forms) and by their neutralization[2] (that they do not take the ending -(e)s in the third-person singular).

The principal English modal verbs are can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would, and must. Certain other verbs are sometimes classed as modals; these include ought, had better, and (in certain uses) dare and need. Verbs which share only some of the characteristics of the principal modals are sometimes called «quasi-modals», «semi-modals», or «pseudo-modals».[2]

Modal verbs and their features[edit]

The verbs customarily classed as modals in English have the following properties:

- They do not inflect (in the modern language) except insofar as some of them come in present–past (present–preterite) pairs. They do not add the ending -(e)s in the third-person singular (the present-tense modals therefore follow the preterite-present paradigm).[a]

- They are defective: they are not used as infinitives or participles (except occasionally in non-standard English; see § Double modals below), nor as imperatives, nor (in the standard way) as subjunctives.

- They function as auxiliary verbs: they modify the modality of another verb, which they govern. This verb generally appears as a bare infinitive, although in some definitions, a modal verb can also govern the to-infinitive (as in the case of ought).

- They have the syntactic properties associated with auxiliary verbs in English, principally that they can undergo subject–auxiliary inversion (in questions, for example) and can be negated by the appending of not after the verb.

- ^ However, they used to be conjugated by person and number, but with the preterite endings. Thus, they often have deviating second-person singular forms, which still may be heard in quotes from the Bible (as in thou shalt not steal) or in poetry.

The following verbs have all of the above properties, and can be classed as the principal modal verbs of English. They are listed here in present–preterite pairs where applicable:

- can and could

- may and might

- shall and should

- will and would

- must (no preterite; see etymology below)

Note that the preterite forms are not necessarily used to refer to past time, and in some cases, they are near-synonyms to the present forms. Note that most of these so-called preterite forms are most often used in the subjunctive mood in the present tense. The auxiliary verbs may and let are also used often in the subjunctive mood. Famous examples of these are «May The Force be with you.» and «Let God bless you with good.» These are both sentences that express some uncertainty; hence they are subjunctive sentences.

The verbs listed below mostly share the above features but with certain differences. They are sometimes, but not always, categorized as modal verbs.[3] They may also be called «semi-modals».

- The verb ought differs from the principal modals only in that it governs a to-infinitive rather than a bare infinitive (compare he should go with he ought to go).

- The verbs dare and need can be used as modals, often in the negative (Dare he fight?; You dare not do that.; You need not go.), although they are more commonly found in constructions where they appear as ordinary inflected verbs (He dares to fight; You don’t need to go). There is also a dialect verb, nearly obsolete but sometimes heard in Appalachia and the Deep South of the United States: darest, which means «dare not», as in «You darest do that.»

- The verb had in the expression had better behaves like a modal verb, hence had better (considered as a compound verb) is sometimes classed as a modal or semi-modal.

- The verb used in the expression used to (do something) can behave as a modal, but is more often used with do-support than with auxiliary-verb syntax: Did she used to do it? (or Did she use to do it?) and She didn’t used to do it (or She didn’t use to do it)[a] are more common than Used she to do it? and She used not (usedn’t) to do it.

Other English auxiliaries appear in a variety of different forms and are not regarded as modal verbs. These are:

- be, used as an auxiliary in passive voice and continuous aspect constructions; it follows auxiliary-verb syntax even when used as a copula, and in auxiliary-like formations such as be going to, is to and be about to;

- have, used as an auxiliary in perfect aspect constructions, including the idiom have got (to); it is also used in have to, which has modal meaning, but here (as when denoting possession) have only rarely follows auxiliary-verb syntax (see also § Must and have to below);

- do; see do-support.

For more general information about English verb inflection and auxiliary usage, see English verbs and English clause syntax. For details of the uses of the particular modals, see § Usage of specific verbs below.

Etymology[edit]

The modals can and could are from Old English can(n) and cuþ, which were respectively present and preterite forms of the verb cunnan («to be able»). The silent l in the spelling of could results from analogy with would and should.

Similarly, may and might are from Old English mæg and meahte, respectively present and preterite forms of magan («may, to be able»); shall and should are from sceal and sceolde, respectively present and preterite forms of sculan («to owe, be obliged»); and will and would are from wille and wolde, respectively present and preterite forms of willan («to wish, want»).

The aforementioned Old English verbs cunnan, magan, sculan, and willan followed the preterite-present paradigm (or, in the case of willan, a similar but irregular paradigm), which explains the absence of the ending -s in the third person on the present forms can, may, shall, and will. (The original Old English forms given above were first and third person singular forms; their descendant forms became generalized to all persons and numbers.)

The verb must comes from Old English moste, part of the verb motan («to be able to, be obliged to»). This was another preterite-present verb, of which moste was in fact the preterite (the present form mot gave rise to mote, which was used as a modal verb in Early Modern English; but must has now lost its past connotations and has replaced mote). Similarly, ought was originally a past form—it derives from ahte, preterite of agan («to own»), another Old English preterite-present verb, whose present tense form ah has also given the modern (regular) verb owe (and ought was formerly used as a past tense of owe).

The verb dare also originates from a preterite-present verb, durran («to dare»), specifically its present tense dear(r), although in its non-modal uses in Modern English it is conjugated regularly. However, need comes from the regular Old English verb neodian (meaning «to be necessary»)—the alternative third person form need (in place of needs), which has become the norm in modal uses, became common in the 16th century.[8]

Syntax[edit]

A modal verb serves as an auxiliary to another verb, which appears in the infinitive form (the bare infinitive, or the to-infinitive in the cases of ought and used as discussed above). Examples: You must escape; This may be difficult.

The verb governed by the modal may be another auxiliary (necessarily one that can appear in infinitive form—this includes be and have, but not another modal, except in the non-standard cases described below under § Double modals). Hence a modal may introduce a chain (technically catena) of verb forms, in which the other auxiliaries express properties such as aspect and voice, as in He must have been given a new job.

Modals can appear in tag questions and other elliptical sentences without the governed verb being expressed: …can he?; I mustn’t.; Would they?

Like other auxiliaries, modal verbs are negated by the addition of the word not after them. (The modification of meaning may not always correspond to simple negation, as in the case of must not.) The modal word can combine with not forms the single word cannot. Most of the modals have contracted negated forms in n’t which are commonly used in informal English: can’t, mustn’t, won’t (from will), etc.

Again like other auxiliaries, modal verbs undergo inversion with their subject, in forming questions and in the other cases described in the article on subject–auxiliary inversion: Could you do this?; On no account may you enter. When there is negation, the contraction with n’t may undergo inversion as an auxiliary in its own right: Why can’t I come in? (or: Why can I not come in?).

More information on these topics can be found at English clause syntax.

Past forms[edit]

The preterite (past) forms given above (could, might, should, and would, corresponding to can, may, shall, and will, respectively) do not always simply modify the meaning of the modal to give it past time reference. The only one regularly used as an ordinary past tense is could, when referring to ability: I could swim may serve as a past form of I can swim.

All the preterites are used as past equivalents for the corresponding present modals in indirect speech and similar clauses requiring the rules of sequence of tenses to be applied. For example, in 1960, it might have been said that People think that we will all be driving hovercars by the year 2000, whereas at a later date it might be reported that In 1960, people thought we would all be driving hovercars by the year 2000.

This «future-in-the-past» (also known as the past prospective, see: prospective) usage of would can also occur in independent sentences: I moved to Green Gables in 1930; I would live there for the next ten years.

In many cases, in order to give modals past reference, they are used together with a «perfect infinitive», namely the auxiliary have and a past participle, as in I should have asked her; You may have seen me. Sometimes these expressions are limited in meaning; for example, must have can refer only to certainty, whereas past obligation is expressed by an alternative phrase such as had to (see § Replacements for defective forms below).

Conditional sentences[edit]

The preterite forms of modals are used in counterfactual conditional sentences, in the apodosis (then-clause). The modal would (sometimes should as a first-person alternative) is used to produce the conditional construction which is typically used in clauses of this type: If you loved me, you would support me. It can be replaced by could (meaning «would be able to») and might (meaning «would possibly») as appropriate.

When the clause has past time reference, the construction with the modal plus perfect infinitive (see above) is used: If they (had) wanted to do it, they would (could/might) have done it by now. (The would have done construction is called the conditional perfect.)

The protasis (if-clause) of such a sentence typically contains the past tense of a verb (or the past perfect construction, in the case of past time reference), without any modal. The modal could may be used here in its role as the past tense of can (if I could speak French). However all the modal preterites can be used in such clauses with certain types of hypothetical future reference: if I should lose or should I lose (equivalent to if I lose); if you would/might/could stop doing that (usually used as a form of request).

Sentences with the verb wish (and expressions of wish using if only…) follow similar patterns to the if-clauses referred to above, when they have counterfactual present or past reference. When they express a desired event in the near future, the modal would is used: I wish you would visit me; If only he would give me a sign.

For more information see English conditional sentences and English subjunctive.

Replacements for defective forms[edit]

As noted above, English modal verbs are defective in that they do not have infinitive, participle, imperative, or (standard) subjunctive forms, and, in some cases, past forms. However in many cases there exist equivalent expressions that carry the same meaning as the modal, and can be used to supply the missing forms. In particular:

- The modals can and could, in their meanings expressing ability, can be replaced by am/is/are able to and was/were able to. Additional forms can thus be supplied: the infinitive (to) be able to, the subjunctive and (rarely) imperative be able to, and the participles being able to and been able to.

- The modals may and might, in their meanings expressing permission, can be replaced by am/is/are allowed to and was/were allowed to.

- The modal must in most meanings can be replaced by have/has to. This supplies the past and past participle form had to, and other forms (to) have to, having to.

- Will can be replaced by am/is/are going to. This can supply the past and other forms: was/were going to, (to) be going to, being/been going to.

- The modals should and ought to might be replaced by am/is/are supposed to, thus supplying the forms was/were supposed to, (to) be supposed to, being/been supposed to.

Contractions and reduced pronunciation[edit]

As already mentioned, most of the modals in combination with not form commonly used contractions: can’t, won’t, etc. Some of the modals also have contracted forms themselves:

- The verb will is often contracted to ‘ll; the same contraction may also represent shall.

- The verb would (or should, when used as a first-person equivalent of would) is often contracted to ‘d.

- The had of had better is also often contracted to ‘d. (The same contraction is also used for other cases of had as an auxiliary.)

Certain of the modals generally have a weak pronunciation when they are not stressed or otherwise prominent; for example, can is usually pronounced /kən/. The same applies to certain words following modals, particularly auxiliary have: a combination like should have is normally reduced to /ʃʊd(h)əv/ or just /ʃʊdə/ «shoulda». Also ought to can become /ɔːtə/ «oughta». See weak and strong forms in English.

Usage of specific verbs[edit]

Can and could [edit]

«Cannot» redirects here. For the Australian comedian, see Jack Cannot.

The modal verb can expresses possibility in a dynamic, deontic, or epistemic sense, that is, in terms of innate ability, permissibility, or possible circumstance. For example:

- I can speak English means «I am able to speak English» or «I know how to speak English.»

- You can smoke here means «you may (are permitted to) smoke here» (in formal English may or might is sometimes considered more correct than can or could in these senses).

- There can be strong rivalry between siblings means that such rivalry is possible.

The preterite form could is used as the past tense or conditional form of can in the above meanings (see § Past forms above). It is also used to express possible circumstance: We could be in trouble here. It is preferable to use could, may or might rather than can when expressing possible circumstance in a particular situation (as opposed to the general case, as in the «rivalry» example above, where can or may is used).

Both can and could can be used to make requests: Can/could you pass me the cheese? means «Please pass me the cheese» (where could indicates greater politeness).

It is common to use can with verbs of perception such as see, hear, etc., as in I can see a tree. Aspectual distinctions can be made, such as I could see it (ongoing state) vs. I saw it (event). See can see.

The use of could with the perfect infinitive expresses past ability or possibility, either in some counterfactual circumstance (I could have told him if I had seen him), or in some real circumstance where the act in question was not in fact realized: I could have told him yesterday (but in fact I didn’t). The use of can with the perfect infinitive, can have…, is a rarer alternative to may have… (for the negative see below).

The negation of can is the single word cannot, only occasionally written separately as can not.[9] Though cannot is preferred (as can not is potentially ambiguous), its irregularity (all other uncontracted verbal negations use at least two words) sometimes causes those unfamiliar with the nuances of English spelling to use the separated form. Its contracted form is can’t (pronounced /kɑːnt/ in RP and some other dialects). The negation of could is the regular could not, contracted to couldn’t.

The negative forms reverse the meaning of the modal (to express inability, impermissibility or impossibility). This differs from the case with may or might used to express possibility: it can’t be true has a different meaning than it may not be true. Thus can’t (or cannot) is often used to express disbelief in the possibility of something, as must expresses belief in the certainty of something. When the circumstance in question refers to the past, the form with the perfect infinitive is used: he can’t (cannot) have done it means «I believe it impossible that he did it» (compare he must have done it).

Occasionally not is applied to the infinitive rather than to the modal (stress would then be applied to make the meaning clear): I could not do that, but I’m going to do it anyway.

May and might[edit]

The verb may expresses possibility in either an epistemic or deontic sense, that is, in terms of possible circumstance or permissibility. For example:

- The mouse may be dead means that it is possible that the mouse is dead.

- You may leave the room means that the listener is permitted to leave the room.

In expressing possible circumstance, may can have future as well as present reference (he may arrive means that it is possible that he will arrive; I may go to the mall means that I am considering going to the mall).

The preterite form might is used as a synonym for may when expressing possible circumstance (as can could – see above). It is sometimes said that might and could express a greater degree of doubt than may. For uses of might in conditional sentences, and as a past equivalent to may in such contexts as indirect speech, see § Past forms above.

May (or might) can also express irrelevance in spite of certain or likely truth: He may be taller than I am, but he is certainly not stronger could mean «While it is (or may be) true that he is taller than I am, that does not make a difference, as he is certainly not stronger.»

May can indicate presently given permission for present or future actions: You may go now. Might used in this way is milder: You might go now if you feel like it. Similarly May I use your phone? is a request for permission (might would be more hesitant or polite).

A less common use of may is to express wishes, as in May you live long and happy or May the Force be with you (see also English subjunctive).

When used with the perfect infinitive, may have indicates uncertainty about a past circumstance, whereas might have can have that meaning, but it can also refer to possibilities that did not occur but could have in other circumstances (see also conditional sentences above).

- She may have eaten the cake (the speaker does not know whether she ate cake).

- She might have eaten cake (this means either the same as the above, or else means that she did not eat cake but that it was or would have been possible for her to eat cake).

Note that the above perfect forms refer to possibility, not permission (although the second sense of might have might sometimes imply permission).

The negated form of may is may not; this does not have a common contraction (mayn’t is obsolete). The negation of might is might not; this is sometimes contracted to mightn’t, mostly in tag questions and in other questions expressing doubt (Mightn’t I come in if I took my boots off?).

The meaning of the negated form depends on the usage of the modal. When possibility is indicated, the negation effectively applies to the main verb rather than the modal: That may/might not be means «That may/might not-be,» i.e. «That may fail to be true.» But when permission is being expressed, the negation applies to the modal or entire verb phrase: You may not go now means «You are not permitted to go now» (except in rare, spoken cases where not and the main verb are both stressed to indicate that they go together: You may go or not go, whichever you wish).

Shall and should[edit]

The verb shall is used in some varieties of English in place of will, indicating futurity when the subject is first person (I shall, we shall).

With second- and third-person subjects, shall indicates an order, command or prophecy: Cinderella, you shall go to the ball! It is often used in writing laws and specifications: Those convicted of violating this law shall be imprisoned for a term of not less than three years; The electronics assembly shall be able to operate within a normal temperature range.

Shall is sometimes used in questions (in the first person) to ask for advice or confirmation of a suggestion: Shall I read now?; What shall we wear?[10]

Should is sometimes used as a first-person equivalent for would (in its conditional and «future-in-the-past» uses), in the same way that shall can replace will. Should is also used to form a replacement for the present subjunctive in some varieties of English, and also in some conditional sentences with hypothetical future reference – see English subjunctive and English conditional sentences.

Should is often used to describe an expected or recommended behavior or circumstance. It can be used to give advice or to describe normative behavior, though without such strong obligatory force as must or have to. Thus You should never lie describes a social or ethical norm. It can also express what will happen according to theory or expectations: This should work. In these uses it is equivalent to ought to.

Both shall and should can be used with the perfect infinitive (shall/should have (done)) in their role as first-person equivalents of will and would (thus to form future perfect or conditional perfect structures). Also shall have may express an order with perfect aspect (you shall have finished your duties by nine o’clock). When should is used in this way it usually expresses something which would have been expected, or normatively required, at some time in the past, but which did not in fact happen (or is not known to have happened): I should have done that yesterday («it would have been expedient, or expected of me, to do that yesterday»).

The formal negations are shall not and should not, contracted to shan’t and shouldn’t. The negation effectively applies to the main verb rather than the auxiliary: you should not do this implies not merely that there is no need to do this, but that there is a need not to do this. The logical negation of I should is I ought not to or I am not supposed to.

Will and would [edit]

- Will as a tense marker is often used to express futurity (The next meeting will be held on Thursday). Since this is an expression of time rather than modality, constructions with will (or sometimes shall; see above and at shall and will) are often referred to as the future tense of English, and forms like will do, will be doing, will have done and will have been doing are often called the simple future, future progressive (or future continuous), future perfect, and future perfect progressive (continuous). With first-person subjects (I, we), in varieties where shall is used for simple expression of futurity, the use of will indicates particular willingness or determination. (Future events are also sometimes referred to using the present tense (see Uses of English verb forms), or using the going to construction.)

- Will can express habitual aspect; for example, he will make mistakes may mean that he frequently makes mistakes (here the word will is usually stressed somewhat, and often expresses annoyance).

Will also has these uses as a modal:[11][12]

- It can express strong probability with present time reference, as in That will be John at the door.

- It can be used to give an indirect order, as in You will do it right now.

Modal uses of the preterite form would include:

- Would is used in some conditional sentences.

- Expression of politeness, as in I would like… (for «I want») and Would you (be so kind as to) do this? (for «Please do this»).

As a tense marker would is used as

- Future of the past, as in I knew I would graduate two years later. This is a past form of future will as described above under § Past forms. (It is sometimes replaced by should in the first person in the same way that will is replaced by shall.)

As an aspect marker, would is used for

- Expression of habitual aspect in past time, as in Back then, I would eat early and would walk to school.[13][14]

Both will and would can be used with the perfect infinitive (will have, would have), either to form the future perfect and conditional perfect forms already referred to, or to express perfect aspect in their other meanings (e.g. there will have been an arrest order, expressing strong probability).

The negated forms are will not (often contracted to won’t) and would not (often contracted to wouldn’t). In the modal meanings of will the negation is effectively applied to the main verb phrase and not to the modality (e.g. when expressing an order, you will not do it expresses an order not to do it, rather than just the absence of an order to do it). For contracted forms of will and would themselves, see § Contractions and reduced pronunciation above.

Must and have to[edit]

The modal must expresses obligation or necessity: You must use this form; We must try to escape. It can also express a conclusion reached by indirect evidence (e.g. Sue must be at home).

An alternative to must is the expression have to or has to depending on the pronoun (in the present tense sometimes have got to), which is often more idiomatic in informal English when referring to obligation. This also provides other forms in which must is defective (see § Replacements for defective forms above) and enables simple negation (see below).

When used with the perfect infinitive (i.e. with have and the past participle), must has only an epistemic flavor: Sue must have left means that the speaker concludes that Sue has left. To express obligation or necessity in the past, had to or some other synonym must be used.

The formal negation of must is must not (contracted to mustn’t). However the negation effectively applies to the main verb, not the modality: You must not do this means that you are required not to do this, not just that you are not required to do this. To express the lack of requirement or obligation, the negative of have to or need (see below) can be used: You don’t have to do this; You needn’t do this.

The above negative forms are not usually used in the sense of a factual conclusion; here it is common to use can’t to express confidence that something is not the case (as in It can’t be here or, with the perfect, Sue can’t have left).

Mustn’t can nonetheless be used as a simple negative of must in tag questions and other questions expressing doubt: We must do it, mustn’t we? Mustn’t he be in the operating room by this stage?

Ought to and had better [edit]

Ought is used with meanings similar to those of should expressing expectation or requirement. The principal grammatical difference is that ought is used with the to-infinitive rather than the bare infinitive, hence we should go is equivalent to we ought to go. Because of this difference of syntax, ought is sometimes excluded from the class of modal verbs, or is classed as a semi-modal.

The reduced pronunciation of ought to (see § Contractions and reduced pronunciation above) is sometimes given the eye dialect spelling oughtta.

Ought can be used with perfect infinitives in the same way as should (but again with the insertion of to): you ought to have done that earlier.

The grammatically negated form is ought not or oughtn’t, equivalent in meaning to shouldn’t (but again used with to).

The expression had better has similar meaning to should and ought when expressing recommended or expedient behavior: I had better get down to work (it can also be used to give instructions with the implication of a threat: you had better give me the money or else). The had of this expression is similar to a modal: it governs the bare infinitive, it is defective in that it is not replaceable by any other form of the verb have, and it behaves syntactically as an auxiliary verb. For this reason the expression had better, considered as a kind of compound verb, is sometimes classed along with the modals or as a semi-modal.

The had of had better can be contracted to ‘d, or in some informal usage (especially American) can be omitted. The expression can be used with a perfect infinitive: you’d better have finished that report by tomorrow. There is a negative form hadn’t better, used mainly in questions: Hadn’t we better start now? It is more common for the infinitive to be negated by means of not after better: You’d better not do that (meaning that you are strongly advised not to do that).

Dare and need [edit]

The verbs dare and need can be used both as modals and as ordinary conjugated (non-modal) verbs. As non-modal verbs they can take a to-infinitive as their complement (I dared to answer her; He needs to clean that), although dare may also take a bare infinitive (He didn’t dare go). In their uses as modals they govern a bare infinitive, and are usually restricted to questions and negative sentences.

Examples of the modal use of dare, followed by equivalents using non-modal dare, where appropriate:

- Dare he do it? («Does he dare to do it?»)

- I daren’t (or dare not or dosn’t) try. («I don’t dare to try»)

- How dare you! (idiomatic expression of outrage)

- I dare say. (another idiomatic expression, here exceptionally without negation or question syntax)

The modal use of need is close in meaning to must expressing necessity or obligation. The negated form need not (needn’t) differs in meaning from must not, however; it expresses lack of necessity, whereas must not expresses prohibition. Examples:

- Need I continue? («Do I need to continue? Must I continue?»)

- You needn’t water the grass («You don’t have to water the grass»; compare the different meaning of You mustn’t water…)

Modal need can also be used with the perfect infinitive: Need I have done that? It is most commonly used here in the negative, to denote that something that was done was (from the present perspective) not in fact necessary: You needn’t have left that tip.

Used to[edit]

The verbal expression used to expresses past states or past habitual actions, usually with the implication that they are no longer so. It is followed by the infinitive (that is, the full expression consists of the verb used plus the to-infinitive). Thus the statement I used to go to college means that the speaker formerly habitually went to college, and normally implies that this is no longer the case.

While used to does not express modality, it has some similarities with modal auxiliaries in that it is invariant and defective in form and can follow auxiliary-verb syntax: it is possible to form questions like Used he to come here? and negatives like He used not (rarely usedn’t) to come here.[citation needed] More common, however, (though not the most formal style) is the syntax that treats used as a past tense of an ordinary verb, and forms questions and negatives using did: Did he use(d) to come here? He didn’t use(d) to come here.[a]

Note the difference in pronunciation between the ordinary verb use /juːz/ and its past form used /juːzd/ (as in scissors are used to cut paper), and the verb forms described here: /juːst/.

The verbal use of used to should not be confused with the adjectival use of the same expression, meaning «familiar with», as in I am used to this, we must get used to the cold. When the adjectival form is followed by a verb, the gerund is used: I am used to going to college in the mornings.

Deduction[edit]

In English, modal verbs as must, have to, have got to, can’t and couldn’t are used to express deduction and contention. These modal verbs state how sure the speaker is about something.[15][16][17]

- You’re shivering—you must be cold.

- Someone must have taken the key: it is not here.

- I didn’t order ten books. This has to be a mistake.

- These aren’t mine—they’ve got to be yours.

- It can’t be a burglar. All the doors and windows are locked.

Double modals[edit]

In formal standard English usage, since modals are followed by a base verb, which modals are not, modal verbs cannot be used consecutively. That requirement then dictates they can be followed by only non-modal verbs. Might have to is acceptable («have to» is not a modal verb), but *might must is not, even though must and have to can normally be used interchangeably.[citation needed] Two rules from different grammatical models supposedly disallow the construction. Proponents of Phrase structure grammar see the surface clause as allowing only one modal verb, while main verb analysis would dictate that modal verbs occur in finite forms.[18]

A greater variety of double modals appears in some regional dialects. In English, for example, phrases such as would dare to and should have to are sometimes used in conversation and are grammatically correct. The double modal may sometimes be in the future tense, as in We must be able to work with must being the main auxiliary and be able to as the infinitive. Other examples include You may not dare to run or I would need to have help.

To put double modals in past tense, only the first modal is changed as in I could ought to. Double modals are also referred to as multiple modals.[19]

To form questions, the subject and the first verb are swapped if the verb requires no do-support, such as Will you be able to write? If the main auxiliary requires do-support, the appropriate form of to do is added to the beginning, as in Did he use to need to fight? If modals are put in the perfect tense, the past participle of the infinitive is used, as in He had been going to swim or You have not been able to skate. In questions, the main verb and subject are swapped, as in Has she had to come?

«I might could do something,» for instance, is an example of a double modal construction that can be found in varieties of Southern American and Midland American English.[18]

Comparison with other Germanic languages[edit]

Many English modals have cognates in other Germanic languages, albeit with different meanings in some cases. Unlike the English modals, however, these verbs are not generally defective; they can inflect, and have forms such as infinitives, participles and future tenses (for example using the auxiliary werden in German). Examples of such cognates include:

- In German: mögen, müssen, können, sollen, wollen; cognates of may, must, can, shall, and will. Although German shares five modal verbs with English, their meanings are often quite different. Mögen does not mean «to be allowed» but «may» as epistemic modal and «to like» as a normal verb followed by a noun. It can be followed by an infinitive with the meaning of «to have a desire to». Wollen means «will» only in the sense of «to want to» and is not used to form the future tense, for which werden is used instead. Müssen, können, and sollen are used similarly as English «must», «can», and «shall». Note, however, that the negation of müssen is a literal one in German, not an inverse one as in English. This is to say that German ich muss («I must») means «I need to», and ich muss nicht (literally the same as «I must not») accordingly means «I don’t need to.» In English, «to have to» behaves the same way, whereas English «must» expresses an interdiction when negated. brauchen (need) is sometimes used like a modal verb, especially negated (Er braucht nicht kommen. «He need not come.»).

- In Dutch: mogen, moeten, kunnen, zullen, willen; cognates of may, must, can, shall, and will.

- In Danish: måtte, kunne, ville, skulle, cognates of may/must, can, will, shall. They generally have the same corresponding meanings in English, with the exception of ville, which usually means «to want to» (but which can also mean «will»).

- In Swedish: må (past tense: måtte), måsta, kunna, vilja, ska(ll), cognates of may/might, must, can, will, shall. They generally have the same corresponding meanings in English, with the exception of vilja, which means «to want to».

Since modal verbs in other Germanic languages are not defective, the problem of double modals (see above) does not arise: the second modal verb in such a construction simply takes the infinitive form, as would any non-modal verb in the same position. Compare the following translations of English «I want to be able to dance», all of which translate literally as «I want can dance» (except German, which translates as «I want dance can»):

- German: Ich will tanzen können.

- Dutch: Ik wil kunnen dansen.

- Danish: Jeg vil kunne danse.

- Swedish: Jag vill kunna dansa.

See also[edit]

- Tense–aspect–mood § Invariant auxiliaries

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Use of did … used to is controversial. According to Garner’s Modern American Usage didn’t used to is the correct idiomatic form, encountered far more commonly in print than did … use to.[4] On the other hand Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage marks didn’t used to as ungrammatical and states «The grammatically correct construction is didn’t use to but this is less frequent in OEC [Oxford English Corpus] data than the ‘anomalous’ *didn’t used to. Despite its higher frequency, purists may well consider the latter incorrect.»[5] A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language states that this spelling «is often regarded as nonstandard» and that the spelling with did … use to is «preferred» in both American and British English.[6] Merriam Webster’s Concise Dictionary of English Usage finds that didn’t use to is the usual form in American English.[7]

References[edit]

- ^ Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. Mood and modality. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world, 176-242. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Jan Svartvik, & Geoffrey Leech. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.

- ^ See Palmer, F. R., Mood and Modality, Cambridge Univ. Press, second edition, 2001, p. 33, and A Linguistic Study of the English Verb, Longmans, 1965. For an author who rejects ought as a modal because of the following particle to (and does not mention had better), see Warner, Anthony R., English Auxiliaries, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. For more examples of discrepancies between different authors’ listings of modal or auxiliary verbs in English, see English auxiliaries.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (2003). Garner’s Modern American Usage. Oxford University Press. p. 810. ISBN 978-0-19-516191-5.

- ^ Jeremy; Butterfield, eds. (2015). Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 853. ISBN 978-0-199-66135-0.

- ^ Quirk, Randolph; Greenbaum, Sidney; Leech, Geoffrey; Svartvik, Jan (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. Harlow: Longman. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-582-51734-9.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Concise Dictionary of English Usage. Merriam-Webster. 2002. pp. 760–761. ISBN 978-0-87779-633-6.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, entry for «need».

- ^ «Definition of cannot | Dictionary.com». www.dictionary.com.

- ^ Koltai, Anastasia (February 21, 2013). «English Grammar: Usage of Shall vs Should with Examples».

- ^ Fleischman, Suzanne, The Future in Thought and Action, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1982, pp. 86–97.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard, Tense, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1985, pp. 21, 47–48.

- ^ «UltraLingua Online Dictionary & Grammar, «Conditional tense»«. Archived from the original on 2009-10-11.

- ^ «The Conditional Tense».

- ^ Modals – deduction (present) Archived 2014-12-15 at the Wayback Machine learnenglish.britishcouncil.org

- ^ Oxford Practice Grammar (Advanced), George Yule, Oxford University Press ISBN 9780194327541 Page:40

- ^ Modals Deduction Past ecenglish.com

- ^ a b Di Paolo, Marianna (1989). «Double Modals as Single Lexical Items». American Speech. 64 (3): 195–224. doi:10.2307/455589. JSTOR 455589.

- ^ Kosur, Heather Marie. 2011. Structure and meaning of periphrastic modal verbs in modern American English: Multiple modals as single-unit constructions. Illinois State University. Department of English — Theses (Master’s).

External links[edit]

- Verbs in English Grammar, wikibook

- modal auxiliaries Website/Project that collects phrases containing modal auxiliaries on the web (in German and English)

- modal auxiliaries Website/Project that collects phrases containing modal auxiliaries on the web (in German and English)

- Modal auxiliary verbs: special points

With time many changes and evolution occur. It is not wrong to say that evolution or change is the only constant. The English language has comprehensive coverage around the globe.

It is one of the oldest international languages whose supremacy is unparalleled. The main motive for mastering English is to make communication smooth between different countries globally.

Although, this language is not difficult to speak or understand. But the proper use of grammar makes it a bit difficult. As the grammar is simple, but people get confused while using it.

Nouns, pronouns, verbs, tenses, and other parts of speech should be assembled correctly to develop a meaningful sentence.

Improper use of words or grammar is generally avoided to avoid any miscommunication. The importance and contribution of modal verbs are high in English.

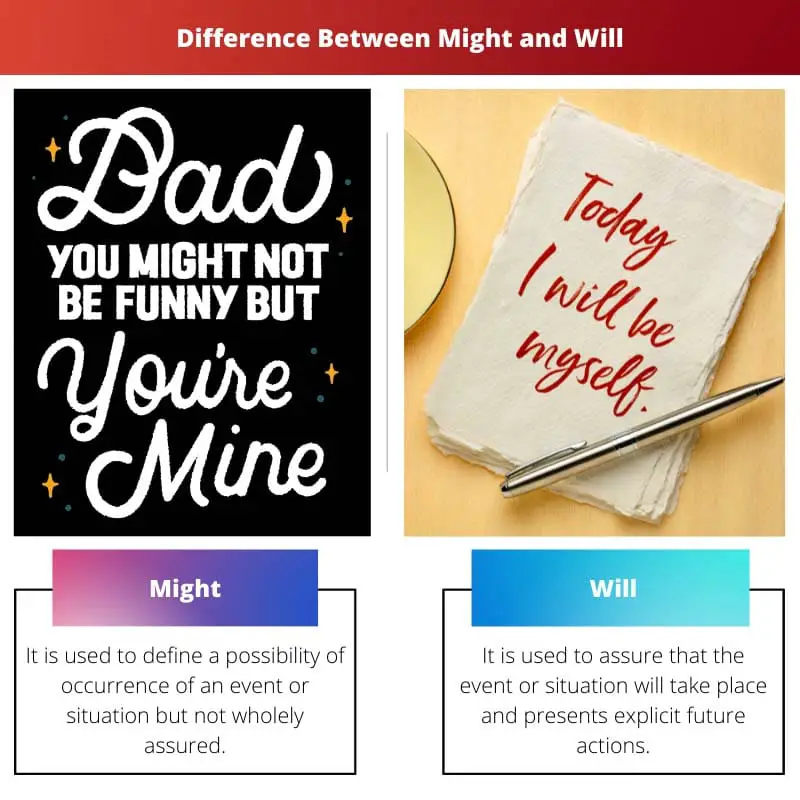

“Might” and “will” are two English verbs people use in their sentences often. Understanding the fundamental difference between their usage is essential to avoid perplexity in the framed sentences.

Key Takeaways

- “Might” is used to express possibility or uncertainty, while “will” is used to express certainty or determination.

- “Might” is a modal verb indicating a lower degree of certainty than “will”.

- “Will” is also used to express future actions, while “might” is not commonly used in the future tense.

‘Might’ is used in situations having a lesser possibility of occurrence. Whereas ‘Will’ is used for decisions, predictions, promises and offers, with higher and more concrete chances of an event. The nature of inculcating ‘might’ in a sentence brings out the possibility. But ‘will’ brings out assurance of a happening.

Want to save this article for later? Click the heart in the bottom right corner to save to your own articles box!

‘Might’ is used to define the possibility of the occurrence of an event or situation but not wholely assured. When the probability of occurrence is low, ‘might’ is used. ‘Might’ is the past principal form of “May”.

In a sentence, ‘might’ is used as a second or sometimes a third conditional sentence. ‘Might’ explains an event that may/may not happen in future.

‘Will’ assures that the event or situation will take place and presents explicit future actions. The nature of inculcating ‘will’ in a sentence brings out assurance. When the probability of occurrence is high, ‘will’ is used.

“Will” is itself the root verb. It is used as the first conditional statement. ‘Will’ explains a possible future situation/event.

Comparison Table

| Parameters of Comparison | Might | Will |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | It is used to define the possibility of the occurrence of an event or situation, but not wholely assured. | It assures that the event or situation will take place and presents explicit future actions. |

| Nature | Dwells as a possibility. | Dwells as assurance. |

| Probability | When the probability of occurrence is low, might is used. | When the probability of occurrence is high, a will is used. |

| Root verb | May | “Will” is itself the root verb. |

| Usage | Used in situations having the lesser possibility of occurrence. | They are used for decisions, predictions, promises, and offers. |

| Conditional statement | In a sentence, it might is used as a second or sometimes a third conditional sentence. | Will is used as the first conditional statement. |

| Explains | An event that may/may not happen in the future. | A possible future situation/event. |

| Example | Jessica might appear Civil Services Examination this time. | My daughter loves shopping. She will go out tonight. |

What is Might?

” Might” refers to an event or situation that is possible, but the probability of occurrence is not entirely hundred per cent. The event may occur, may not happen and get cancelled.

E.g. Jack might not go to Golf Club next. Here, the chances of occurrence and cancellation of the event are there.

However, there are more chances that the event will happen.

Might is the past principal form of the verb “may”. It is a prepositional word. This verb is generally used to determine those events which have lesser chances of occurrence in future.

Most of the time, it describes a hypothetical situation that has fewer chances of happening. Might is an auxiliary verb. Most of the time, ‘might’ is used interchangeably with ‘may’. However, some of the time, it is incorrect.

What is Will?

‘Will’ is a modal auxiliary verb. Most of the time, it is used as a verb. However, it is used as a noun as well. But it is widely accepted as a verb. ‘Will’ describes a situation or event which has the possibility of happening in occurrence in future.

This word portrays somebody’s wishes or determination to fulfil or achieve something in the coming time. Most of the time, this word is used indefinite statements.

This auxiliary verb is also used to deliver sentences with offers and promises. E.g. My son will buy me a present for my promotion.

‘Will’ is also used in the first conditional sentence. For example, ” if students do not study hard, they can not succeed in future”. This word is also used to deliver belief and decision. E.g.

“my mom believes that I will crack RBI Examination this year”. And ” I have become bankrupt; I will not invest in the share market anymore”.

Main Differences Between Might and Will

- ‘Might’ is used to define the possibility of the occurrence of an event or situation but not wholely assured. Whereas ‘will’ ensures that the event or condition will occur and presents explicit future actions.

- The nature of inculcating ‘might’ in a sentence brings out the possibility, but ‘will’ brings out assurance.

- When the probability of occurrence is low, ‘might’ is used. But when the probability of occurrence is high, “will” is used.

- ‘Might’ is the past principal form of “May”. Whereas “Will” is itself the root verb.

- ‘Might’ is used in situations having a lesser possibility of occurrence. But ‘Will’ is used for decisions, predictions, promises and offers.

- In a sentence, ‘might’ is used as a second or sometimes a third conditional sentence. Whereas ‘will’ is used as the first conditional statement.

- ‘Might’ explains an event that may/may not happen in future. Whereas ‘will’ explains a possible future situation/event.

References

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-international-neuropsychological-society/article/cognitive-rehabilitation-how-it-is-and-how-it-might-be/F611EB5761428D58B4C1FB54CA599FF2

Emma Smith holds an MA degree in English from Irvine Valley College. She has been a Journalist since 2002, writing articles on the English language, Sports, and Law. Read more about me on her bio page.

The Future Simple is probably the simplest tense of all tenses in the English language.

If you are learning the Future Simple after the Present Simple and the Past Simple, it will be easy for you to understand the Future Simple.

What is Future Simple tense?

The Future Simple is a very important tense. We use the Future Simple to say what will or may happen in the future.

It doesn’t matter what kind of future we’re talking about. We can use the Future Simple when we are talking about something that will happen in a second or 1000 years from the moment of speaking.

We use the Future Simple to express:

- Something that will or will not happen.

- Something that we will or will not do.

- Promises.

- Events in the future will happen because we cannot influence them.

- Warnings and threats.

Take a look at these examples:

The game will be over soon.

Dad will be at work tomorrow.

John will buy a new car in a year.

I will call you back in five minutes.

They will not go to the theater.

How to form sentences

I said that The Future Simple is one of the simplest tenses for a reason. Because the Future Simple is very simple to form.

To form the Future Simple, you do not need to add or change any endings of the main verb.

All sentences in the Future Simple are built in the most usual way. Except for the fact that we need to add the auxiliary verb to the sentence, which indicates that you are talking about the future. This is the verb will.

We use will the same way regardless of who is the subject. Regardless of what type of sentence we form: affirmative (positive), interrogative (question), or negative. We always use will in all types of sentences.

How to form Affirmative (Positive) Sentences in Future Simple

To form an affirmative (positive) sentence, we put the auxiliary verb will after the subject. Then we add the main verb in the base form without the to.

Subject (I, you, John, Dog, Friends) + will + Main verb (love, watch, jump) + the rest of the sentence.

I will take your car!

John will visit Sarah.

We will go Home.

How to form Negative Sentences in Future Simple

To form a negative sentence, we add the negative not after the auxiliary verb will.

Will not.

We use will not after the subject and before the main verb.

Subject (I, You, John, Dog, Friends) + will not + main verb (love, watch, jump) + the rest of the sentence.

John will not visit Jennifer.

Daddy will not buy a new car.

We will not go to school tomorrow.

The dog will not catch up with this cat.

How to form Interrogative (Question) Sentences in Future Simple

We form an interrogative (question) sentence in the same way as the affirmative (positive). Only we put the auxiliary verb will before the subject at the beginning of the sentence.

will + Subject (I, You, John, Dog, Friends) + main verb (love, watch, jump) + the rest of the sentence.

Will you come to visit me?

Will we win this game?

Will we like our new teacher?

Will Jessica marry John?

Wh-Question in Future Simple

Special or Wh-Questions are questions that we use to find out more information.

We can ask:

Will John visit Max?

By asking this question, we can find out whether John will visit Max or not. This is a question that can be answered with simple YES or NO.

But what if we want to know when exactly John will visit Max? Or why will John visit Max? To find out this additional information, we need question words or even whole phrases.

When will John visit Max?

Who will John visit Max with?

Question words help us get more information. Here are the most popular Question words:

- how

- why

- when

- who

- what

- where

- which

Wh-Questions in the Future Simple are formed in the same way as General or Yes/No Questions. Only at the beginning of the question, we put an additional, question word or phrase. After that we put the auxiliary verb will, then the subject, then the main verb in the base form without the particle to. Then we can add the rest of the sentence.

Question word or phrase (who, what, where) + will + Subject (I, You, John, Dog, Friends) + main verb (love, watch, jump) + the rest of the sentence.

When will you see your friend?

Where will you go first?

Where will it be available?

How to Answer Questions

There are two main ways you can answer questions in English:

- Short positive/negative answer

- Full positive/negative answer

We form a Short Positive Answer using this pattern:

Yes + Subject + Will.

Will you find a new job?

Yes, I will.Will you meet Jessica at the train station?

Yes, I will.

Will in the answer means the same verb that was the main verb in the question.

Will you meet Jessica at the train station?

Yes, I will. (Yes I will meet)

We form a short negative answer in the same way, only at the beginning of the sentence we put No and we add the negative not to the auxiliary verb will. Will + not + Will not:

No + Subject + Will not.

Will you meet Jessica at the train station?

No, I will not (No, I will not meet).

Now let’s talk about full answers.

To form a full affirmative (positive) answer, we turn the question into a Positive sentence. We also put Yes at the beginning of the sentence.

Yes + Subject + Will + Main verb + Rest of the sentence

Will you help me?

Yes, I will help you.

To form a full negative answer, we use the word No instead of Yes. We add the negative not after will.

No + Subject + Will not + Main verb + Rest of the sentence.

Will you help me?

No, I will not help you.

What is the abbreviation (short form) for will and will not?

In the Future Simple we often contract the auxiliary will.

| Full | Short |

|---|---|

| I will | I’ll |

| He will | He’ll |

| She will | She’ll |

| It will | It’ll |

| We will | We’ll |

| They will | They’ll |

| You will | You’ll |

In the affirmative (positive), the will is contracted to two letters -ll which are added to the subject:

- I’ll – I will

- He’ll – He will

- She’ll – She will

- It’ll – It will

- We’ll – We will

- They’ll – They will

- You’ll – You will

I’ll help you tomorrow = I will help you tomorrow

The contraction for the negative form will.

| Full | Short |

|---|---|

| I will not | I won’t |

| He will not | He won’t |

| She will not | She won’t |

| It will not | It won’t |

| We will not | We won’t |

| They will not | They won’t |

| You will not | You won’t |

We contract the negative will in a slightly unusual way. The letter “o” appears in this abbreviation. Will not turns into Won’t. It looks like this:

- I won’t – I will not

- He won’t – He will not

- She won’t – She will not

- It won’t – It will not

- We won’t – We will not

- They won’t – They will not

- You won’t – You will not

I won’t do this = I will not do this.

When We Use the Future Simple

- We use the Future Simple when we talk about a single event that will or will not happen in the future. Or when we indicate the exact time when something will happen.

I will visit him soon.

She will talk to John tomorrow.

We will go to Grandma’s next weekend.

I will call you at lunchtime.

- We use the Future Simple when we talk about some kind of spontaneous decision.

You know what… I will take your car!

I will not sleep, I want to play more!

- When we talk about some action that will occur and will be repeated in the future.

Next month Jessica and I will go to the theater three times.

John will visit his grandmother two times next year.

- The Future Simple is good for making a promise to someone to do something. Or when we threaten someone.

I swear I will study well this year.

Nothing will stop me! I will catch you and send you to jail!

We also use the Future Simple when we offer to do something or help someone. In this case, we change will to shall. Such sentences look like a question.

KEEP IN MIND: We use shall only with the pronouns I or We.

Shall we clean the room?

- We use the Future Simple when we predict some events or actions and this prediction is based on the personal opinion of the speaker.

I think we will win this game.

He thinks a new teacher will be better than Mr. Gordon.

I’m afraid you will fail.

I am afraid this building will collapse soon.

You can also read the full article When we use Future Simple: 15 use cases.

To be in Future Simple

The verb to be is easy to use in the Future Simple.

Why?

For example, in the Present Simple or the Past Simple, the verb to be has different forms. In the Future Simple, the verb to be has only one form: WILL BE. To be in Future Simple forms questions, negations, or affirmations with the help of the auxiliary verb will.

Isn’t it easy to remember?

How to form Affirmative (Positive) Sentences with to be

The verb to be in Present Simple looks like will be. We use will be regardless of who is the subject.

Look at the affirmative (positive) sentence in the Future Simple with the verb love.

I will love you.

Look at the word order we used in the sentence.

We use exactly the same word order with the verb to be. Only instead of the main verb we use be.

Subject + will + be + rest of the sentence.

I will be there at six o’clock in the evening.

See how easy it is?

How to form Interrogative (question) sentences with to be

To ask a question, we use the same formula that we use with any other verbs in the Future Simple. Only instead of the main verb we use be.

will + subject + be + rest of the sentence.

Will you be at work tomorrow morning?

How to form Negative Sentences in with to be

A negative sentence is formed in the same way as a regular negative sentence with any other verb in Future Simple.

Subject + will not + bе + rest of the sentence

I will not be home for dinner.

Do we use Shall in Future Simple?

Shall is another auxiliary (and modal) verb in English. Sometimes we use shall instead of will but only with the pronouns I and We.

Shall cannot be used with You, He, It …

- I shall (Can be used instead of I will)

- He will (We cannot say

He shall) - She Will (We cannot say

She shall) - It will (We cannot say

It shall) - We shall (Can be used instead of We will)

- They will (We cannot say

They shall) - You will (We cannot say

You shall)

Remember, we rarely use shall in modern English. Most often it can be found in interrogative (question) sentences when someone offers to help someone.

Of course, you need to know how to properly use shall in the Future Simple. Because you may find this verb in books, business correspondence, etc.

So remember, shall can be used in positive, question, and negative sentences in the Future Simple just like will. But only with pronouns I and We.

Affirmative (positive) sentences with shall:

I shall open this box.

We shall help you, my friend!

Similarly, in a Positive sentence, we can put the verb will instead of shall:

I will open this box.

We will help you, my friend!

You shall not pass!

Question sentences with shall.

Shall I open this box?

Shall we help you, my friend?

We can put will instead of shall, but it can change the meaning of the sentence from what we were trying to say.

Will I open this box?

Will we help you, my friend?

In those examples, the sentences with will do not sound anymore as an offer to help. With will instead of shall it sounds more like questions.

Negative sentences with shall.

I shall not open this box.

We shall not help you, my friend!

Similarly, in Negative sentences, you can put the verb will instead of shall:

I will not open this box.

We will not help you, my friend!

How to use To be going to

What is to be going to?

To be going to is a very interesting and useful phrase in English. You will come across this phrase very often.

To be going to is another way of saying that something will happen in the future.

To be going to is used to talk about:

- Your or someone else’s plans for the future.

- Events likely to occur in the future.

I am going to tell you the whole truth about the English language.

We are going to paint the house green.

How to form sentences with To be going to in Present Simple

If you look closely at To be going to, you will see that the first part is the verb to be.

To form this phrase, we just need to change the first part in accordance with our subject. Let’s remember how the verb to be changes in the Present Simple:

- I am

- He is

- She is

- It is

- We are

- They are

- You are

Together with going to, the complete construction looks like this:

- I am going to

- He is going to

- She is going to

- It is going to

- We are going to

- They are going to

- You are going to

Questions are also formed according to the rules of the verb to be in the Present Simple:

Am I going to?

Is she going to?

Are they going to?

Are you going to?

Negative sentences are also formed according to the rules of the verb to be in the Present Simple:

I am not going to…

She is not going to…

They are not going to…

You are not going to…

The short form is also formed according to the same rules as we contract the verb to be in the Present Simple:

- They‘re going to or They aren’t going to

- He‘s going to or He isn’t going to

- I‘m not going to

- You‘re not going to or You aren’t going to

What is the difference between Will vs To be going to

Let’s take a look at the difference between will and to be going to.

Take a look at two examples:

John is going to become a doctor.

John will be a doctor.

In one sentence we used will in the other to be going to.

These two methods are very similar and can often replace each other. In these cases, we can use both sentences to say about John’s future.

But will and be going to do not always mean the same thing.

We use to be going to to say about a thought-out decision. Not just a spontaneous decision, but a deliberate one.

Imagine John needs a new car. John made enough money. John has chosen the model of the car he wants to buy. John plans to buy a car next week. This is not a spontaneous decision. This is a deliberate decision. Therefore, John can say this using to be going to:

I‘m going to buy a new car.

Everyone who hears John understands that this decision is deliberate. And John seriously decided to buy a new car.

We often use the Future Simple to talk about plans that are not accurate. That is, in our example with John, John had not thought about buying a car before. John didn’t choose the model of the car. But suddenly he got such an idea. John can say this using the Future Simple:

I will buy a new car.

The Future Simple is well suited for those decisions that were made spontaneously right at the time of the conversation. For example:

John is hanging out with his friends. The friends tell John that John has an old car, maybe he needs a new car? John makes a spontaneous decision:

I will buy a new car.

If he says about this decision using to be going to, it would no longer sound like a spontaneous decision, but like his plans for which he has been ready for some time.

We use To be going to when a decision is planned.

We use Will when the decision is spontaneous.

How to use will not as a refusal

Now let’s talk about one nuance of will, or rather its negative form will not.

Will not (won’t) often does NOT mean that someone will not do something in the future. Will not often means that someone refuses to do something in the future.

John won’t help mom.

This example may mean that John does not want to, he refuses to help his mother.

If you doubt that someone can misunderstand you, then it is better to use to be going to.

John is not going to help mom.

One more difference between will and to be going to is that:

We often use to be going to when we talk about plans for the near future.

We often use Will when we talk about plans for the distant future.

Markers of Future Simple

In the Future Simple, we often use special words that indicate this tense. We call such words markers. The Future Simple markers indicate some time in the future. This time can be specified exactly, such as “tomorrow at 6 hours” or approximately as “soon”.

- tonight

- next hour

- next day

- next week

- next month

- next year

- soon

- later

- in ten days

- in 2035

- in a month

- in two months

- in two years

- as soon as

- tomorrow

Examples of Future Simple

Take a look at the sentences in which we use the Future Simple. Think about the rules used in these sentences.

Dad will go to work tomorrow.

I’ll buy a car.

I’m going to get married next month!

We will study well.

John and Jessica will go to the theater three times next month.

Will John go to Grandma’s next week?

How many times will you call him?

They will write you a letter shortly.

The house will soon fall apart.

Max will visit his friend.