Democracy (from Ancient Greek: δημοκρατία, romanized: dēmokratía, dēmos ‘people’ and kratos ‘rule’[1]) is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation («direct democracy»), or to choose governing officials to do so («representative democracy»). Who is considered part of «the people» and how authority is shared among or delegated by the people has changed over time and at different rates in different countries. Features of democracy often include freedom of assembly, association, property rights, freedom of religion and speech, inclusiveness and equality, citizenship, consent of the governed, voting rights, freedom from unwarranted governmental deprivation of the right to life and liberty, and minority rights.

The notion of democracy has evolved over time considerably. Throughout history, one can find evidence of direct democracy, in which communities make decisions through popular assembly. Today, the dominant form of democracy is representative democracy, where citizens elect government officials to govern on their behalf such as in a parliamentary or presidential democracy.[2]

Prevalent day-to-day decision making of democracies is the majority rule,[3][4] though other decision making approaches like supermajority and consensus have also been integral to democracies. They serve the crucial purpose of inclusiveness and broader legitimacy on sensitive issues—counterbalancing majoritarianism—and therefore mostly take precedence on a constitutional level. In the common variant of liberal democracy, the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution and a supreme court limit the majority and protect the minority—usually through securing the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech or freedom of association.[5][6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC in Greek city-states, notably Classical Athens, to mean «rule of the people», in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning «rule of an elite».[7] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in antiquity, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as those in Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship was initially restricted to an elite class, which was later extended to all adult citizens. In most modern democracies, this was achieved through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

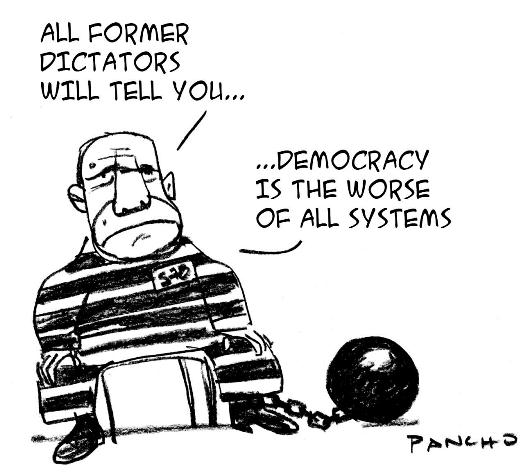

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in autocratic systems like absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy—oppositions inherited from ancient Greek philosophy.[8] Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.[9] World public opinion strongly favors democratic systems of government.[10] According to the V-Dem Institute and Economist Intelligence Unit democracy indices, less than half the world’s population lives in a democracy as of 2021.[11][12] Democratic backsliding with a rise in hybrid regimes has exceeded democratization since the early to mid 2010s.[11]

Characteristics[edit]

Although democracy is generally understood to be defined by voting,[1][6] no consensus exists on a precise definition of democracy.[13] Karl Popper says that the «classical» view of democracy is simply,[14] «in brief, the theory that democracy is the rule of the people, and that the people have a right to rule.» Kofi Annan states that «there are as many different forms of democracy as there are democratic nations in the world.»[15] One study identified 2,234 adjectives used to describe democracy in the English language.[16]

Democratic principles are reflected in all eligible citizens being equal before the law and having equal access to legislative processes.[17] For example, in a representative democracy, every vote has equal weight, no unreasonable restrictions can apply to anyone seeking to become a representative,[according to whom?] and the freedom of its eligible citizens is secured by legitimised rights and liberties which are typically protected by a constitution.[18][19] Other uses of «democracy» include that of direct democracy, in which issues are directly voted on by the constituents.

One theory holds that democracy requires three fundamental principles: upward control (sovereignty residing at the lowest levels of authority), political equality, and social norms by which individuals and institutions only consider acceptable acts that reflect the first two principles of upward control and political equality.[20] Legal equality, political freedom and rule of law[21] are often identified as foundational characteristics for a well-functioning democracy.[13]

The term «democracy» is sometimes used as shorthand for liberal democracy, which is a variant of representative democracy that may include elements such as political pluralism; equality before the law; the right to petition elected officials for redress of grievances; due process; civil liberties; human rights; and elements of civil society outside the government.[citation needed] Roger Scruton argued that democracy alone cannot provide personal and political freedom unless the institutions of civil society are also present.[22]

In some countries, notably in the United Kingdom which originated the Westminster system, the dominant principle is that of parliamentary sovereignty, while maintaining judicial independence.[23][24] In India, parliamentary sovereignty is subject to the Constitution of India which includes judicial review.[25] Though the term «democracy» is typically used in the context of a political state, the principles also are applicable to private organisations.

There are many decision-making methods used in democracies, but majority rule is the dominant form. Without compensation, like legal protections of individual or group rights, political minorities can be oppressed by the «tyranny of the majority». Majority rule is a competitive approach, opposed to consensus democracy, creating the need that elections, and generally deliberation, are substantively and procedurally «fair,» i.e. just and equitable. In some countries, freedom of political expression, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and internet democracy are considered important to ensure that voters are well informed, enabling them to vote according to their own interests.[26][27]

It has also been suggested that a basic feature of democracy is the capacity of all voters to participate freely and fully in the life of their society.[28] With its emphasis on notions of social contract and the collective will of all the voters, democracy can also be characterised as a form of political collectivism because it is defined as a form of government in which all eligible citizens have an equal say in lawmaking.[29]

Republics, though often associated with democracy because of the shared principle of rule by consent of the governed, are not necessarily democracies, as republicanism does not specify how the people are to rule.[30]

Classically the term «republic» encompassed both democracies and aristocracies.[31][32] In a modern sense the republican form of government is a form of government without monarch. Because of this democracies can be republics or constitutional monarchies, such as the United Kingdom.

History[edit]

Democratic assemblies are as old as the human species and are found throughout human history,[34] but up until the nineteenth century, major political figures have largely opposed democracy.[35] Republican theorists linked democracy to small size: as political units grew in size, the likelihood increased that the government would turn despotic.[36][37] At the same time, small political units were vulnerable to conquest.[36] Montesquieu wrote, «If a republic be small, it is destroyed by a foreign force; if it be large, it is ruined by an internal imperfection.»[38] According to Johns Hopkins University political scientist Daniel Deudney, the creation of the United States, with its large size and its system of checks and balances, was a solution to the dual problems of size.[36][pages needed]

Retrospectively different polities, outside of declared democracies, have been described as proto-democratic.

Origins[edit]

The term democracy first appeared in ancient Greek political and philosophical thought in the city-state of Athens during classical antiquity.[39][40] The word comes from dêmos ‘(common) people’ and krátos ‘force/might’.[41] Under Cleisthenes, what is generally held as the first example of a type of democracy in 508–507 BC was established in Athens. Cleisthenes is referred to as «the father of Athenian democracy».[42] The first attested use of the word democracy is found in prose works of the 430s BC, such as Herodotus’ Histories, but its usage was older by several decades, as two Athenians born in the 470s were named Democrates, a new political name—likely in support of democracy—given at a time of debates over constitutional issues in Athens. Aeschylus also strongly alludes to the word in his play The Suppliants, staged in c.463 BC, where he mentions «the demos’s ruling hand» [demou kratousa cheir]. Before that time, the word used to define the new political system of Cleisthenes was probably isonomia, meaning political equality.[43]

Athenian democracy took the form of a direct democracy, and it had two distinguishing features: the random selection of ordinary citizens to fill the few existing government administrative and judicial offices,[44] and a legislative assembly consisting of all Athenian citizens.[45] All eligible citizens were allowed to speak and vote in the assembly, which set the laws of the city state. However, Athenian citizenship excluded women, slaves, foreigners (μέτοικοι / métoikoi), and youths below the age of military service.[46][47][contradictory] Effectively, only 1 in 4 residents in Athens qualified as citizens. Owning land was not a requirement for citizenship.[48] The exclusion of large parts of the population from the citizen body is closely related to the ancient understanding of citizenship. In most of antiquity the benefit of citizenship was tied to the obligation to fight war campaigns.[49]

Athenian democracy was not only direct in the sense that decisions were made by the assembled people, but also the most direct in the sense that the people through the assembly, boule and courts of law controlled the entire political process and a large proportion of citizens were involved constantly in the public business.[50] Even though the rights of the individual were not secured by the Athenian constitution in the modern sense (the ancient Greeks had no word for «rights»[51]), those who were citizens of Athens enjoyed their liberties not in opposition to the government but by living in a city that was not subject to another power and by not being subjects themselves to the rule of another person.[52]

Range voting appeared in Sparta as early as 700 BC. The Spartan ecclesia was an assembly of the people, held once a month, in which every male citizen of at least 20 years of age could participate. In the assembly, Spartans elected leaders and cast votes by range voting and shouting (the vote is then decided on how loudly the crowd shouts). Aristotle called this «childish», as compared with the stone voting ballots used by the Athenian citizenry. Sparta adopted it because of its simplicity, and to prevent any biased voting, buying, or cheating that was predominant in the early democratic elections.[53][54]

Even though the Roman Republic contributed significantly to many aspects of democracy, only a minority of Romans were citizens with votes in elections for representatives. The votes of the powerful were given more weight through a system of weighted voting, so most high officials, including members of the Senate, came from a few wealthy and noble families.[55] In addition, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom was the first case in the Western world of a polity being formed with the explicit purpose of being a republic, although it didn’t have much of a democracy. The Roman model of governance inspired many political thinkers over the centuries,[56] and today’s modern representative democracies imitate more the Roman than the Greek models because it was a state in which supreme power was held by the people and their elected representatives, and which had an elected or nominated leader.[citation needed]

Vaishali, capital city of the Vajjika League (Vrijji mahajanapada) of India, was also considered one of the first examples of a republic around the 6th century BC.[57][58][59]

Other cultures, such as the Iroquois Nation in the Americas also developed a form of democratic society between 1450 and 1660 (and possibly in 1142[60]), well before contact with the Europeans. This democracy continues to the present day and is the world’s oldest standing representative democracy.[61][62] This indicates that forms of democracy may have been invented in other societies around the world.[63]

Middle Ages[edit]

While most regions in Europe during the Middle Ages were ruled by clergy or feudal lords, there existed various systems involving elections or assemblies, although often only involving a small part of the population. In Scandinavia, bodies known as things consisted of freemen presided by a lawspeaker. These deliberative bodies were responsible for settling political questions, and variants included the Althing in Iceland and the Løgting in the Faeroe Islands.[64][65] The veche, found in Eastern Europe, was a similar body to the Scandinavian thing. In the Roman Catholic Church, the pope has been elected by a papal conclave composed of cardinals since 1059. The first documented parliamentary body in Europe was the Cortes of León. Established by Alfonso IX in 1188, the Cortes had authority over setting taxation, foreign affairs and legislating, though the exact nature of its role remains disputed.[66] The Republic of Ragusa, established in 1358 and centered around the city of Dubrovnik, provided representation and voting rights to its male aristocracy only. Various Italian city-states and polities had republic forms of government. For instance, the Republic of Florence, established in 1115, was led by the Signoria whose members were chosen by sortition. In 10th–15th century Frisia, a distinctly non-feudal society, the right to vote on local matters and on county officials was based on land size. The Kouroukan Fouga divided the Mali Empire into ruling clans (lineages) that were represented at a great assembly called the Gbara. However, the charter made Mali more similar to a constitutional monarchy than a democratic republic.

The Parliament of England had its roots in the restrictions on the power of kings written into Magna Carta (1215), which explicitly protected certain rights of the King’s subjects and implicitly supported what became the English writ of habeas corpus, safeguarding individual freedom against unlawful imprisonment with right to appeal.[67][68] The first representative national assembly in England was Simon de Montfort’s Parliament in 1265.[69][70] The emergence of petitioning is some of the earliest evidence of parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people. However, the power to call parliament remained at the pleasure of the monarch.[71]

Studies have linked the emergence of parliamentary institutions in Europe during the medieval period to urban agglomeration and the creation of new classes, such as artisans,[72] as well as the presence of nobility and religious elites.[73] Scholars have also linked the emergence of representative government to Europe’s relative political fragmentation.[74] Political scientist David Stasavage links the fragmentation of Europe, and its subsequent democratization, to the manner in which the Roman Empire collapsed: Roman territory was conquered by small fragmented groups of Germanic tribes, thus leading to the creation of small political units where rulers were relatively weak and needed the consent of the governed to ward off foreign threats.[75]

In Poland, noble democracy was characterized by an increase in the activity of the middle nobility, which wanted to increase their share in exercising power at the expense of the magnates. Magnates dominated the most important offices in the state (secular and ecclesiastical) and sat on the royal council, later the senate. The growing importance of the middle nobility had an impact on the establishment of the institution of the land sejmik (local assembly), which subsequently obtained more rights. During the fifteenth and first half of the sixteenth century, sejmiks received more and more powers and became the most important institutions of local power. In 1454, Casimir IV Jagiellon granted the sejmiks the right to decide on taxes and to convene a mass mobilization in the Nieszawa Statutes. He also pledged not to create new laws without their consent.[76]

Modern era[edit]

Early modern period[edit]

In 17th century England, there was renewed interest in Magna Carta.[77] The Parliament of England passed the Petition of Right in 1628 which established certain liberties for subjects. The English Civil War (1642–1651) was fought between the King and an oligarchic but elected Parliament,[78][79] during which the idea of a political party took form with groups debating rights to political representation during the Putney Debates of 1647.[80] Subsequently, the Protectorate (1653–59) and the English Restoration (1660) restored more autocratic rule, although Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679 which strengthened the convention that forbade detention lacking sufficient cause or evidence. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the Bill of Rights was enacted in 1689 which codified certain rights and liberties and is still in effect. The Bill set out the requirement for regular elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike much of Europe at the time, royal absolutism would not prevail.[81][82] Economic historians Douglass North and Barry Weingast have characterized the institutions implemented in the Glorious Revolution as a resounding success in terms of restraining the government and ensuring protection for property rights.[83]

Renewed interest in the Magna Carta, the English Civil War, and the Glorious Revolution in the 17th century prompted the growth of political philosophy on the British Isles. Thomas Hobbes was the first philosopher to articulate a detailed social contract theory. Writing in Leviathan (1651), Hobbes theorized that individuals living in the state of nature led lives that were «solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short» and constantly waged a war of all against all. In order to prevent the occurrence of an anarchic state of nature, Hobbes reasoned that individuals ceded their rights to a strong, authoritarian government. Later, philosopher and physician John Locke would posit a different interpretation of social contract theory. Writing in his Two Treatises of Government (1689), Locke posited that all individuals possessed the inalienable rights to life, liberty and estate (property).[84] According to Locke, individuals would voluntarily come together to form a state for the purposes of defending their rights. Particularly important for Locke were property rights, whose protection Locke deemed to be a government’s primary purpose.[85] Furthermore, Locke asserted that governments were legitimate only if they held the consent of the governed. For Locke, citizens had the right to revolt against a government that acted against their interest or became tyrannical. Although they were not widely read during his lifetime, Locke’s works are considered the founding documents of liberal thought and profoundly influenced the leaders of the American Revolution and later the French Revolution.[86] His liberal democratic framework of governance remains the preeminent form of democracy in the world.

In the Cossack republics of Ukraine in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Cossack Hetmanate and Zaporizhian Sich, the holder of the highest post of Hetman was elected by the representatives from the country’s districts.

In North America, representative government began in Jamestown, Virginia, with the election of the House of Burgesses (forerunner of the Virginia General Assembly) in 1619. English Puritans who migrated from 1620 established colonies in New England whose local governance was democratic;[87] although these local assemblies had some small amounts of devolved power, the ultimate authority was held by the Crown and the English Parliament. The Puritans (Pilgrim Fathers), Baptists, and Quakers who founded these colonies applied the democratic organisation of their congregations also to the administration of their communities in worldly matters.[88][89][90]

18th and 19th centuries[edit]

Statue of Athena, the patron goddess of Athens, in front of the Austrian Parliament Building. Athena has been used as an international symbol of freedom and democracy since at least the late eighteenth century.[91]

The first Parliament of Great Britain was established in 1707, after the merger of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland under the Acts of Union. Although the monarch increasingly became a figurehead,[92] Parliament was only elected by male property owners, which amounted to 3% of the population in 1780.[93] The first known British person of African heritage to vote in a general election, Ignatius Sancho, voted in 1774 and 1780.[94] During the Age of Liberty in Sweden (1718–1772), civil rights were expanded and power shifted from the monarch to parliament. The taxed peasantry was represented in parliament, although with little influence, but commoners without taxed property had no suffrage.

The creation of the short-lived Corsican Republic in 1755 was an early attempt to adopt a democratic constitution (all men and women above age of 25 could vote).[95] This Corsican Constitution was the first based on Enlightenment principles and included female suffrage, something that was not included in most other democracies until the 20th century.

In the American colonial period before 1776, and for some time after, often only adult white male property owners could vote; enslaved Africans, most free black people and most women were not extended the franchise. This changed state by state, beginning with the republican State of New Connecticut, soon after called Vermont, which, on declaring independence of Great Britain in 1777, adopted a constitution modelled on Pennsylvania’s with citizenship and democratic suffrage for males with or without property, and went on to abolish slavery.[96][97] The American Revolution led to the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787, the oldest surviving, still active, governmental codified constitution. The Constitution provided for an elected government and protected civil rights and liberties for some, but did not end slavery nor extend voting rights in the United States, instead leaving the issue of suffrage to the individual states.[98] Generally, states limited suffrage to white male property owners and taxpayers.[99] At the time of the first Presidential election in 1789, about 6% of the population was eligible to vote.[100] The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only.[101] The Bill of Rights in 1791 set limits on government power to protect personal freedoms but had little impact on judgements by the courts for the first 130 years after ratification.[102]

In 1789, Revolutionary France adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and, although short-lived, the National Convention was elected by all men in 1792.[103] The Polish-Lithuanian Constitution of 3 May 1791 sought to implement a more effective constitutional monarchy, introduced political equality between townspeople and nobility, and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. In force for less than 19 months, it was declared null and void by the Grodno Sejm that met in 1793.[104][105] Nonetheless, the 1791 Constitution helped keep alive Polish aspirations for the eventual restoration of the country’s sovereignty over a century later.

However, in the early 19th century, little of democracy—as theory, practice, or even as word—remained in the North Atlantic world.[106] During this period, slavery remained a social and economic institution in places around the world. This was particularly the case in the United States, where eight serving presidents had owned slaves, and the last fifteen slave states kept slavery legal in the American South until the Civil War.[107] Advocating the movement of black people from the US to locations where they would enjoy greater freedom and equality, in the 1820s the abolitionist members of the ACS established the settlement of Liberia.[108] The United Kingdom’s Slave Trade Act 1807 banned the trade across the British Empire, which was enforced internationally by the Royal Navy under treaties Britain negotiated with other states.[109] In 1833, the UK passed the Slavery Abolition Act which took effect across the British Empire, although slavery was legally allowed to continue in areas controlled by the East India Company, in Ceylon, and in Saint Helena for an additional ten years.[110]

In the United States, the 1828 presidential election was the first in which non-property-holding white males could vote in the vast majority of states. Voter turnout soared during the 1830s, reaching about 80% of the adult white male population in the 1840 presidential election.[111] North Carolina was the last state to abolish property qualification in 1856 resulting in a close approximation to universal white male suffrage (however tax-paying requirements remained in five states in 1860 and survived in two states until the 20th century).[112][113][114][nb 1] In the 1860 United States Census, the slave population had grown to four million,[115] and in Reconstruction after the Civil War, three constitutional amendments were passed: the 13th Amendment (1865) that ended slavery; the 14th Amendment (1869) that gave black people citizenship, and the 15th Amendment (1870) that gave black males a nominal right to vote.[116][117] Full enfranchisement of citizens was not secured until after the civil rights movement gained passage by the US Congress of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[118][119]

The voting franchise in the United Kingdom was expanded and made more uniform in a series of reforms that began with the Reform Act 1832 and continued into the 20th century, notably with the Representation of the People Act 1918 and the Equal Franchise Act 1928. Universal male suffrage was established in France in March 1848 in the wake of the French Revolution of 1848.[120] During that year, several revolutions broke out in Europe as rulers were confronted with popular demands for liberal constitutions and more democratic government.[121]

In 1876 the Ottoman Empire transitioned from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one, and held two elections the next year to elect members to her newly formed parliament.[122] Provisional Electoral Regulations were issued, stating that the elected members of the Provincial Administrative Councils would elect members to the first Parliament. Later that year, a new constitution was promulgated, which provided for a bicameral Parliament with a Senate appointed by the Sultan and a popularly elected Chamber of Deputies. Only men above the age of 30 who were competent in Turkish and had full civil rights were allowed to stand for election. Reasons for disqualification included holding dual citizenship, being employed by a foreign government, being bankrupt, employed as a servant, or having «notoriety for ill deeds». Full universal suffrage was achieved in 1934.[123]

In 1893 the self-governing colony New Zealand became the first country in the world (except for the short-lived 18th-century Corsican Republic) to establish active universal suffrage by recognizing women as having the right to vote.[124]

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

The number of nations 1800–2003 scoring 8 or higher on Polity IV scale, another widely used measure of democracy

20th-century transitions to liberal democracy have come in successive «waves of democracy», variously resulting from wars, revolutions, decolonisation, and religious and economic circumstances.[125] Global waves of «democratic regression» reversing democratization, have also occurred in the 1920s and 30s, in the 1960s and 1970s, and in the 2010s.[126][127]

World War I and the dissolution of the autocratic Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires resulted in the creation of new nation-states in Europe, most of them at least nominally democratic. In the 1920s democratic movements flourished and women’s suffrage advanced, but the Great Depression brought disenchantment and most of the countries of Europe, Latin America, and Asia turned to strong-man rule or dictatorships. Fascism and dictatorships flourished in Nazi Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal, as well as non-democratic governments in the Baltics, the Balkans, Brazil, Cuba, China, and Japan, among others.[128]

World War II brought a definitive reversal of this trend in western Europe. The democratisation of the American, British, and French sectors of occupied Germany (disputed[129]), Austria, Italy, and the occupied Japan served as a model for the later theory of government change. However, most of Eastern Europe, including the Soviet sector of Germany fell into the non-democratic Soviet-dominated bloc.

The war was followed by decolonisation, and again most of the new independent states had nominally democratic constitutions. India emerged as the world’s largest democracy and continues to be so.[130] Countries that were once part of the British Empire often adopted the British Westminster system.[131][132] By 1960, the vast majority of country-states were nominally democracies, although most of the world’s populations lived in nominal democracies that experienced sham elections, and other forms of subterfuge (particularly in «Communist» states and the former colonies.)

A subsequent wave of democratisation brought substantial gains toward true liberal democracy for many states, dubbed «third wave of democracy.» Portugal, Spain, and several of the military dictatorships in South America returned to civilian rule in the 1970s and 1980s.[nb 2] This was followed by countries in East and South Asia by the mid-to-late 1980s. Economic malaise in the 1980s, along with resentment of Soviet oppression, contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the associated end of the Cold War, and the democratisation and liberalisation of the former Eastern bloc countries. The most successful of the new democracies were those geographically and culturally closest to western Europe, and they are now either part of the European Union or candidate states. In 1986, after the toppling of the most prominent Asian dictatorship, the only democratic state of its kind at the time emerged in the Philippines with the rise of Corazon Aquino, who would later be known as the Mother of Asian Democracy.

Corazon Aquino taking the Oath of Office, becoming the first female president in Asia

The liberal trend spread to some states in Africa in the 1990s, most prominently in South Africa. Some recent examples of attempts of liberalisation include the Indonesian Revolution of 1998, the Bulldozer Revolution in Yugoslavia, the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, and the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia.

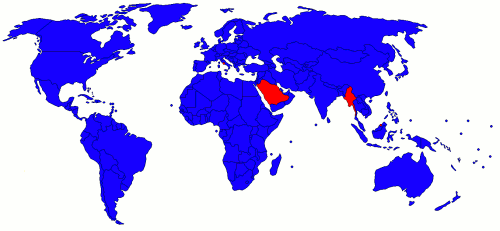

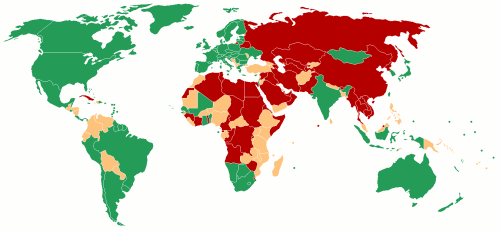

Age of democracies at the end of 2015[133]

According to Freedom House, in 2007 there were 123 electoral democracies (up from 40 in 1972).[134] According to World Forum on Democracy, electoral democracies now represent 120 of the 192 existing countries and constitute 58.2 percent of the world’s population. At the same time liberal democracies i.e. countries Freedom House regards as free and respectful of basic human rights and the rule of law are 85 in number and represent 38 percent of the global population.[135] Also in 2007 the United Nations declared 15 September the International Day of Democracy.[136]

Many countries reduced their voting age to 18 years; the major democracies began to do so in the 1970s starting in Western Europe and North America.[137][failed verification][138][139] Most electoral democracies continue to exclude those younger than 18 from voting.[140] The voting age has been lowered to 16 for national elections in a number of countries, including Brazil, Austria, Cuba, and Nicaragua. In California, a 2004 proposal to permit a quarter vote at 14 and a half vote at 16 was ultimately defeated. In 2008, the German parliament proposed but shelved a bill that would grant the vote to each citizen at birth, to be used by a parent until the child claims it for themselves.

According to Freedom House, starting in 2005, there have been eleven consecutive years in which declines in political rights and civil liberties throughout the world have outnumbered improvements,[141] as populist and nationalist political forces have gained ground everywhere from Poland (under the Law and Justice Party) to the Philippines (under Rodrigo Duterte).[141][126] In a Freedom House report released in 2018, Democracy Scores for most countries declined for the 12th consecutive year.[142] The Christian Science Monitor reported that nationalist and populist political ideologies were gaining ground, at the expense of rule of law, in countries like Poland, Turkey and Hungary. For example, in Poland, the President appointed 27 new Supreme Court judges over legal objections from the European Commission. In Turkey, thousands of judges were removed from their positions following a failed coup attempt during a government crackdown .[143]

Countries autocratizing (red) or democratizing (blue) substantially and significantly (2010–2020). Countries in grey are substantially unchanged.[144]

«Democratic backsliding» in the 2010s were attributed to economic inequality and social discontent,[145] personalism,[146] poor management of the COVID-19 pandemic,[147][148] as well as other factors such as government manipulation of civil society, «toxic polarization,» foreign disinformation campaigns,[149] racism and nativism, excessive executive power,[150][151][152] and decreased power of the opposition.[153] Within English-speaking Western democracies, «protection-based» attitudes combining cultural conservatism and leftist economic attitudes were the strongest predictor of support for authoritarian modes of governance.[154]

Theory[edit]

Early theory[edit]

Aristotle contrasted rule by the many (democracy/timocracy), with rule by the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), and with rule by a single person (tyranny or today autocracy/absolute monarchy). He also thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system (he considered democracy to be the degenerate counterpart to timocracy).[155][156]

A common view among early and renaissance Republican theorists was that democracy could only survive in small political communities.[157] Heeding the lessons of the Roman Republic’s shift to monarchism as it grew larger or smaller, these Republican theorists held that the expansion of territory and population inevitably led to tyranny.[157] Democracy was therefore highly fragile and rare historically, as it could only survive in small political units, which due to their size were vulnerable to conquest by larger political units.[157] Montesquieu famously said, «if a republic is small, it is destroyed by an outside force; if it is large, it is destroyed by an internal vice.»[157] Rousseau asserted, «It is, therefore the natural property of small states to be governed as a republic, of middling ones to be subject to a monarch, and of large empires to be swayed by a despotic prince.»[157]

Contemporary theory[edit]

Among modern political theorists, there are three contending conceptions of democracy: aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy, and radical democracy.[158]

Aggregative[edit]

The theory of aggregative democracy claims that the aim of the democratic processes is to solicit citizens’ preferences and aggregate them together to determine what social policies society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented.

Different variants of aggregative democracy exist. Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens have given teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not «rule» because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[159] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

According to the theory of direct democracy, on the other hand, citizens should vote directly, not through their representatives, on legislative proposals. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socialises and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter—with half to their left and the other half to their right. This is not a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Anthony Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[160]

Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[161] Similarly, Ronald Dworkin argues that «democracy is a substantive, not a merely procedural, ideal.»[162]

Deliberative[edit]

Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by deliberation. Unlike aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtained through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.[163][164][165] If the decision-makers cannot reach consensus after authentically deliberating on a proposal, then they vote on the proposal using a form of majority rule. Citizens assemblies are considered by many scholars as practical examples of deliberative democracy,[166][167][168] with a recent OECD report identifying citizens assemblies as an increasingly popular mechanism to involve citizens in governmental decision-making.[169]

Radical[edit]

Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy’s role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision-making processes.

Measurement of democracy[edit]

Indices ranking degree of democracy[edit]

Ranking of the degree of democracy are published by several organisations according to their own various definitions of the term and relying on different types of data:[170][171]

- Democracy Index, by the UK-based Economist Intelligence Unit, is an assessment of countries’ democracy. Countries are rated as full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, or authoritarian regimes. The index is based on five different categories measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture.[172]

- Freedom in the World, is a yearly survey and report by the U.S.-based[173] non-governmental organization Freedom House that measures the degree of civil liberties and political rights in every nation and significant related and disputed territories around the world.[174]

- International IDEAs «Global State of Democracy Report» assesses democratic performance using different types of sources: expert surveys, standards-based coding by research groups and analysts, observational data and composite measures.[175]

- V-Dem Democracy indices by V-Dem Institute distinguishes between five high-level principles of democracy: electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian, and quantifies these principles.[176] The V-Dem Democracy indices include the Citizen-initiated component of direct popular vote index, which indicates the strength of direct democracy and the presidentialism index, which indicates higher concentration of political power in the hands of one individual.

Difficulties in measuring democracy[edit]

Because democracy is an overarching concept that includes the functioning of diverse institutions which are not easy to measure, strong limitations exist in quantifying and econometrically measuring the potential effects of democracy or its relationship with other phenomena—whether inequality, poverty, education etc.[177] Given the constraints in acquiring reliable data with within-country variation on aspects of democracy, academics have largely studied cross-country variations. Yet variations between democratic institutions are very large across countries which constrains meaningful comparisons using statistical approaches. Since democracy is typically measured aggregately as a macro variable using a single observation for each country and each year, studying democracy faces a range of econometric constraints and is limited to basic correlations. Cross-country comparison of a composite, comprehensive and qualitative concept like democracy may thus not always be, for many purposes, methodologically rigorous or useful.[177]

Dieter Fuchs and Edeltraud Roller suggest that, in order to truly measure the quality of democracy, objective measurements need to be complemented by «subjective measurements based on the perspective of citizens».[178] Similarly, Quinton Mayne and Brigitte Geißel also defend that the quality of democracy does not depend exclusively on the performance of institutions, but also on the citizens’ own dispositions and commitment.[179]

Another way of conceiving of the difficulties in measuring democracy is through the debate between minimalist versus maximalist definitions of democracy. As defended by Adam Przeworski, a minimalist conception of democracy defines democracy by primarily considering the structure of electoral procedures; such procedures, minimalists argue, are the essence of democracy.[180] A minimalist’s focus on structure may help to avoid the erroneous incorporation of noninherent outcomes, such as economic or administrative efficiency, into measures of democracy.[181]

Mainstream measures of democracy, notably Freedom House and Polity IV, deploy a maximalist understanding of democracy by analyzing indictors that go beyond electoral procedure.[182] These measures attempt to gauge contestation and inclusion; two features Robert Dahl argued are essential in democracies that successfully promote accountable governments.[183][184] The democratic rating given by these mainstream measures can vary greatly depending on the indicators and evidence they deploy.[185] The richness of the definition of democracy utilized by these measures is important because of the discouraging and alienating power such ratings can have, particularly when determined by indicators which are biased towards Western democracies.[186]

Types of governmental democracies[edit]

Democracy has taken a number of forms, both in theory and practice. Some varieties of democracy provide better representation and more freedom for their citizens than others.[187][188] However, if any democracy is not structured to prohibit the government from excluding the people from the legislative process, or any branch of government from altering the separation of powers in its favour, then a branch of the system can accumulate too much power and destroy the democracy.[189][190][191]

1This map was compiled according to the Wikipedia list of countries by system of government. See there for sources. 2Several states constitutionally deemed to be multiparty republics are broadly described by outsiders as authoritarian states. This map presents only the de jure form of government, and not the de facto degree of democracy.

The following kinds of democracy are not exclusive of one another: many specify details of aspects that are independent of one another and can co-exist in a single system.

Basic forms[edit]

Several variants of democracy exist, but there are two basic forms, both of which concern how the whole body of all eligible citizens executes its will. One form of democracy is direct democracy, in which all eligible citizens have active participation in the political decision making, for example voting on policy initiatives directly.[192] In most modern democracies, the whole body of eligible citizens remain the sovereign power but political power is exercised indirectly through elected representatives; this is called a representative democracy.

Direct[edit]

In Switzerland, without needing to register, every citizen receives ballot papers and information brochures for each vote (and can send it back by post). Switzerland has a direct democracy system and votes (and elections) are organised about four times a year; here, to Berne’s citizen in November 2008 about 5 national, 2 cantonal, 4 municipal referendums, and 2 elections (government and parliament of the City of Berne) to take care of at the same time.

Direct democracy is a political system where the citizens participate in the decision-making personally, contrary to relying on intermediaries or representatives. A direct democracy gives the voting population the power to:

- Change constitutional laws,

- Put forth initiatives, referendums and suggestions for laws,

- Give binding orders to elective officials, such as revoking them before the end of their elected term or initiating a lawsuit for breaking a campaign promise.[citation needed]

Within modern-day representative governments, certain electoral tools like referendums, citizens’ initiatives and recall elections are referred to as forms of direct democracy.[193] However, some advocates of direct democracy argue for local assemblies of face-to-face discussion. Direct democracy as a government system currently exists in the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus,[194] the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities,[195] communities affiliated with the CIPO-RFM,[196] the Bolivian city councils of FEJUVE,[197] and Kurdish cantons of Rojava.[198]

Lot system[edit]

The use of a lot system, a characteristic of Athenian democracy, is a feature of some versions of direct democracies. In this system, important governmental and administrative tasks are performed by citizens picked from a lottery.[199]

Representative[edit]

Representative democracy involves the election of government officials by the people being represented. If the head of state is also democratically elected then it is called a democratic republic.[200] The most common mechanisms involve election of the candidate with a majority or a plurality of the votes. Most western countries have representative systems.[194]

Representatives may be elected or become diplomatic representatives by a particular district (or constituency), or represent the entire electorate through proportional systems, with some using a combination of the two. Some representative democracies also incorporate elements of direct democracy, such as referendums. A characteristic of representative democracy is that while the representatives are elected by the people to act in the people’s interest, they retain the freedom to exercise their own judgement as how best to do so. Such reasons have driven criticism upon representative democracy,[201][202] pointing out the contradictions of representation mechanisms with democracy[203][204]

Parliamentary[edit]

Parliamentary democracy is a representative democracy where government is appointed by or can be dismissed by, representatives as opposed to a «presidential rule» wherein the president is both head of state and the head of government and is elected by the voters. Under a parliamentary democracy, government is exercised by delegation to an executive ministry and subject to ongoing review, checks and balances by the legislative parliament elected by the people.[205][206][207][208]

In a parliamentary system, the Prime Minister may be dismissed by the legislature at any point in time for not meeting the expectations of the legislature. This is done through a Vote of No Confidence where the legislature decides whether or not to remove the Prime Minister from office with majority support for dismissal.[209] In some countries, the Prime Minister can also call an election at any point in time, typically when the Prime Minister believes that they are in good favour with the public as to get re-elected. In other parliamentary democracies, extra elections are virtually never held, a minority government being preferred until the next ordinary elections. An important feature of the parliamentary democracy is the concept of the «loyal opposition». The essence of the concept is that the second largest political party (or opposition) opposes the governing party (or coalition), while still remaining loyal to the state and its democratic principles.

Presidential[edit]

Presidential Democracy is a system where the public elects the president through an election. The president serves as both the head of state and head of government controlling most of the executive powers. The president serves for a specific term and cannot exceed that amount of time. The legislature often has limited ability to remove a president from office. Elections typically have a fixed date and aren’t easily changed. The president has direct control over the cabinet, specifically appointing the cabinet members.[209]

The executive usually has the responsibility to execute or implement legislation and may have the limited legislative powers, such as a veto. However, a legislative branch passes legislation and budgets. This provides some measure of separation of powers. In consequence, however, the president and the legislature may end up in the control of separate parties, allowing one to block the other and thereby interfere with the orderly operation of the state. This may be the reason why presidential democracy is not very common outside the Americas, Africa, and Central and Southeast Asia.[209]

A semi-presidential system is a system of democracy in which the government includes both a prime minister and a president. The particular powers held by the prime minister and president vary by country.[209]

Hybrid or semi-direct[edit]

Some modern democracies that are predominantly representative in nature also heavily rely upon forms of political action that are directly democratic. These democracies, which combine elements of representative democracy and direct democracy, are termed hybrid democracies,[210] semi-direct democracies or participatory democracies. Examples include Switzerland and some U.S. states, where frequent use is made of referendums and initiatives.

The Swiss confederation is a semi-direct democracy.[194] At the federal level, citizens can propose changes to the constitution (federal popular initiative) or ask for a referendum to be held on any law voted by the parliament.[194] Between January 1995 and June 2005, Swiss citizens voted 31 times, to answer 103 questions (during the same period, French citizens participated in only two referendums).[194] Although in the past 120 years less than 250 initiatives have been put to referendum.[211]

Examples include the extensive use of referendums in the US state of California, which is a state that has more than 20 million voters.[212]

In New England, town meetings are often used, especially in rural areas, to manage local government. This creates a hybrid form of government, with a local direct democracy and a representative state government. For example, most Vermont towns hold annual town meetings in March in which town officers are elected, budgets for the town and schools are voted on, and citizens have the opportunity to speak and be heard on political matters.[213]

Democratic backsliding[edit]

Democratization[edit]

Variants[edit]

Constitutional monarchy[edit]

Many countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries, Thailand, Japan and Bhutan turned powerful monarchs into constitutional monarchs (often gradually) with limited or symbolic roles. For example, in the predecessor states to the United Kingdom, constitutional monarchy began to emerge and has continued uninterrupted since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and passage of the Bill of Rights 1689.[23][81] Strongly limited constitutional monarchies, such as the United Kingdom, have been referred to as crowned republics by writers such as H. G. Wells.[228]

In other countries, the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system (as in France, China, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Egypt). An elected person, with or without significant powers, became the head of state in these countries.

Elite upper houses of legislatures, which often had lifetime or hereditary tenure, were common in many states. Over time, these either had their powers limited (as with the British House of Lords) or else became elective and remained powerful (as with the Australian Senate).

Republic[edit]

The term republic has many different meanings, but today often refers to a representative democracy with an elected head of state, such as a president, serving for a limited term, in contrast to states with a hereditary monarch as a head of state, even if these states also are representative democracies with an elected or appointed head of government such as a prime minister.[229]

The Founding Fathers of the United States often criticised direct democracy, which in their view often came without the protection of a constitution enshrining inalienable rights; James Madison argued, especially in The Federalist No. 10, that what distinguished a direct democracy from a republic was that the former became weaker as it got larger and suffered more violently from the effects of faction, whereas a republic could get stronger as it got larger and combats faction by its very structure.[230]

Professors Richard Ellis of Willamette University and Michael Nelson of Rhodes College argue that much constitutional thought, from Madison to Lincoln and beyond, has focused on «the problem of majority tyranny.» They conclude, «The principles of republican government embedded in the Constitution represent an effort by the framers to ensure that the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness would not be trampled by majorities.»[231] What was critical to American values, John Adams insisted,[232] was that the government be «bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend.» As Benjamin Franklin was exiting after writing the U.S. constitution, Elizabeth Willing Powel[233] asked him «Well, Doctor, what have we got—a republic or a monarchy?». He replied «A republic—if you can keep it.»[234]

Liberal democracy[edit]

A liberal democracy is a representative democracy in which the ability of the elected representatives to exercise decision-making power is subject to the rule of law, and moderated by a constitution or laws that emphasise the protection of the rights and freedoms of individuals, and which places constraints on the leaders and on the extent to which the will of the majority can be exercised against the rights of minorities (see civil liberties).

In a liberal democracy, it is possible for some large-scale decisions to emerge from the many individual decisions that citizens are free to make. In other words, citizens can «vote with their feet» or «vote with their dollars», resulting in significant informal government-by-the-masses that exercises many «powers» associated with formal government elsewhere.

[edit]

Socialist thought has several different views on democracy. Social democracy, democratic socialism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat (usually exercised through Soviet democracy) are some examples. Many democratic socialists and social democrats believe in a form of participatory, industrial, economic and/or workplace democracy combined with a representative democracy.

Within Marxist orthodoxy there is a hostility to what is commonly called «liberal democracy», which is referred to as parliamentary democracy because of its centralised nature. Because of orthodox Marxists’ desire to eliminate the political elitism they see in capitalism, Marxists, Leninists and Trotskyists believe in direct democracy implemented through a system of communes (which are sometimes called soviets). This system ultimately manifests itself as council democracy and begins with workplace democracy.

Democracy cannot consist solely of elections that are nearly always fictitious and managed by rich landowners and professional politicians.

Anarchist[edit]

Anarchists are split in this domain, depending on whether they believe that a majority-rule is tyrannic or not. To many anarchists, the only form of democracy considered acceptable is direct democracy. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognised that majority decisions are not binding on the minority, even when unanimous.[236] However, anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin criticised individualist anarchists for opposing democracy,[237] and says «majority rule» is consistent with anarchism.[238]

Some anarcho-communists oppose the majoritarian nature of direct democracy, feeling that it can impede individual liberty and opt-in favour of a non-majoritarian form of consensus democracy, similar to Proudhon’s position on direct democracy.[239] Henry David Thoreau, who did not self-identify as an anarchist but argued for «a better government»[240] and is cited as an inspiration by some anarchists, argued that people should not be in the position of ruling others or being ruled when there is no consent.

Sortition[edit]

Sometimes called «democracy without elections», sortition chooses decision makers via a random process. The intention is that those chosen will be representative of the opinions and interests of the people at large, and be more fair and impartial than an elected official. The technique was in widespread use in Athenian Democracy and Renaissance Florence[241] and is still used in modern jury selection.

Consociational[edit]

Consociational democracy was first conceptualized in the 1960s by Dutch-American political scientist Arend Lijphart. Consociational democracy, also called consociationalism, can be defined as a form of democracy based on power-sharing formula between elites representing the social groups in the society. According to the founder of the theory of consociational democracy, Arendt Lijphart, «Consociational democracy means government by elite cartel designed to turn a democracy with a fragmented political culture into a stable democracy».[242]

A consociational democracy allows for simultaneous majority votes in two or more ethno-religious constituencies, and policies are enacted only if they gain majority support from both or all of them.

Consensus democracy[edit]

A consensus democracy, in contrast, would not be dichotomous. Instead, decisions would be based on a multi-option approach, and policies would be enacted if they gained sufficient support, either in a purely verbal agreement or via a consensus vote—a multi-option preference vote. If the threshold of support were at a sufficiently high level, minorities would be as it were protected automatically. Furthermore, any voting would be ethno-colour blind.

Supranational[edit]

Qualified majority voting is designed by the Treaty of Rome to be the principal method of reaching decisions in the European Council of Ministers. This system allocates votes to member states in part according to their population, but heavily weighted in favour of the smaller states. This might be seen as a form of representative democracy, but representatives to the Council might be appointed rather than directly elected.

Inclusive[edit]

Inclusive democracy is a political theory and political project that aims for direct democracy in all fields of social life: political democracy in the form of face-to-face assemblies which are confederated, economic democracy in a stateless, moneyless and marketless economy, democracy in the social realm, i.e. self-management in places of work and education, and ecological democracy which aims to reintegrate society and nature. The theoretical project of inclusive democracy emerged from the work of political philosopher Takis Fotopoulos in «Towards An Inclusive Democracy» and was further developed in the journal Democracy & Nature and its successor The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy.

The basic unit of decision making in an inclusive democracy is the demotic assembly, i.e. the assembly of demos, the citizen body in a given geographical area which may encompass a town and the surrounding villages, or even neighbourhoods of large cities. An inclusive democracy today can only take the form of a confederal democracy that is based on a network of administrative councils whose members or delegates are elected from popular face-to-face democratic assemblies in the various demoi. Thus, their role is purely administrative and practical, not one of policy-making like that of representatives in representative democracy.

The citizen body is advised by experts but it is the citizen body which functions as the ultimate decision-taker. Authority can be delegated to a segment of the citizen body to carry out specific duties, for example, to serve as members of popular courts, or of regional and confederal councils. Such delegation is made, in principle, by lot, on a rotation basis, and is always recallable by the citizen body. Delegates to regional and confederal bodies should have specific mandates.

Participatory politics[edit]

A Parpolity or Participatory Polity is a theoretical form of democracy that is ruled by a Nested Council structure. The guiding philosophy is that people should have decision-making power in proportion to how much they are affected by the decision. Local councils of 25–50 people are completely autonomous on issues that affect only them, and these councils send delegates to higher level councils who are again autonomous regarding issues that affect only the population affected by that council.

A council court of randomly chosen citizens serves as a check on the tyranny of the majority, and rules on which body gets to vote on which issue. Delegates may vote differently from how their sending council might wish but are mandated to communicate the wishes of their sending council. Delegates are recallable at any time. Referendums are possible at any time via votes of most lower-level councils, however, not everything is a referendum as this is most likely a waste of time. A parpolity is meant to work in tandem with a participatory economy.

Cosmopolitan[edit]

Cosmopolitan democracy, also known as Global democracy or World Federalism, is a political system in which democracy is implemented on a global scale, either directly or through representatives. An important justification for this kind of system is that the decisions made in national or regional democracies often affect people outside the constituency who, by definition, cannot vote. By contrast, in a cosmopolitan democracy, the people who are affected by decisions also have a say in them.[243]

According to its supporters, any attempt to solve global problems is undemocratic without some form of cosmopolitan democracy. The general principle of cosmopolitan democracy is to expand some or all of the values and norms of democracy, including the rule of law; the non-violent resolution of conflicts; and equality among citizens, beyond the limits of the state. To be fully implemented, this would require reforming existing international organisations, e.g. the United Nations, as well as the creation of new institutions such as a World Parliament, which ideally would enhance public control over, and accountability in, international politics.

Cosmopolitan Democracy has been promoted, among others, by physicist Albert Einstein,[244] writer Kurt Vonnegut, columnist George Monbiot, and professors David Held and Daniele Archibugi.[245] The creation of the International Criminal Court in 2003 was seen as a major step forward by many supporters of this type of cosmopolitan democracy.

Creative democracy[edit]

Creative Democracy is advocated by American philosopher John Dewey. The main idea about Creative Democracy is that democracy encourages individual capacity building and the interaction among the society. Dewey argues that democracy is a way of life in his work of «Creative Democracy: The Task Before Us»[246] and an experience built on faith in human nature, faith in human beings, and faith in working with others. Democracy, in Dewey’s view, is a moral ideal requiring actual effort and work by people; it is not an institutional concept that exists outside of ourselves. «The task of democracy», Dewey concludes, «is forever that of creation of a freer and more humane experience in which all share and to which all contribute».

Guided democracy[edit]

Guided democracy is a form of democracy that incorporates regular popular elections, but which often carefully «guides» the choices offered to the electorate in a manner that may reduce the ability of the electorate to truly determine the type of government exercised over them. Such democracies typically have only one central authority which is often not subject to meaningful public review by any other governmental authority. Russian-style democracy has often been referred to as a «Guided democracy.»[247] Russian politicians have referred to their government as having only one center of power/ authority, as opposed to most other forms of democracy which usually attempt to incorporate two or more naturally competing sources of authority within the same government.[248]

Non-governmental democracy[edit]

Aside from the public sphere, similar democratic principles and mechanisms of voting and representation have been used to govern other kinds of groups. Many non-governmental organisations decide policy and leadership by voting. Most trade unions and cooperatives are governed by democratic elections. Corporations are ultimately governed by their shareholders through shareholder democracy. Corporations may also employ systems such as workplace democracy to handle internal governance. Amitai Etzioni has postulated a system that fuses elements of democracy with sharia law, termed Islamocracy.[249] There is also a growing number of Democratic educational institutions such as Sudbury schools that are co-governed by students and staff.

Shareholder democracy[edit]

Shareholder democracy is a concept relating to the governance of corporations by their shareholders. In the United States, shareholders are typically granted voting rights according to the one share, one vote principle. Shareholders may vote annually to elect the company’s board of directors, who themselves may choose the company’s executives. The shareholder democracy framework may be inaccurate for companies which have different classes of stock that further alter the distribution of voting rights.

Justification[edit]

Several justifications for democracy have been postulated.

Legitimacy[edit]

Social contract theory argues that the legitimacy of government is based on consent of the governed, i.e. an election, and that political decisions must reflect the general will. Some proponents of the theory like Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocate for a direct democracy on this basis.[250]

Better decision-making[edit]

Condorcet’s jury theorem is logical proof that if each decision-maker has a better than chance probability of making the right decision, then having the largest number of decision-makers, i.e. a democracy, will result in the best decisions. This has also been argued by theories of the wisdom of the crowd.

Economic success[edit]

In Why Nations Fail, economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that democracies are more economically successful because undemocratic political systems tend to limit markets and favor monopolies at the expense of the creative destruction which is necessary for sustained economic growth.

A 2019 study by Acemoglu and others estimated that countries switching to democratic from authoritarian rule had on average a 20% higher GDP after 25 years than if they had remained authoritarian. The study examined 122 transitions to democracy and 71 transitions to authoritarian rule, occurring from 1960 to 2010.[251] Acemoglu said this was because democracies tended to invest more in health care and human capital, and reduce special treatment of regime allies.[252]

Criticism[edit]

Arrow’s theorem[edit]

Arrow’s impossibility theorem suggests that democracy is logically incoherent. This is based on a certain set of criteria for democratic decision-making being inherently conflicting, i.e. these three «fairness» criteria:

- If every voter prefers alternative X over alternative Y, then the group prefers X over Y.

- If every voter’s preference between X and Y remains unchanged, then the group’s preference between X and Y will also remain unchanged (even if voters’ preferences between other pairs like X and Z, Y and Z, or Z and W change).

- There is no «dictator»: no single voter possesses the power to always determine the group’s preference.

Kenneth Arrow summarised the implications of the theorem in a non-mathematical form, stating that «no voting method is fair», «every ranked voting method is flawed», and «the only voting method that isn’t flawed is a dictatorship».[253]

However, Arrow’s formal premises can be considered overly strict, and with their reasonable weakening, the logical incoherence of democracy looks much less critical.[2]

Inefficiencies[edit]

Some economists have criticized the efficiency of democracy, citing the premise of the irrational voter, or a voter who makes decisions without all of the facts or necessary information in order to make a truly informed decision. Another argument is that democracy slows down processes because of the amount of input and participation needed in order to go forward with a decision. A common example often quoted to substantiate this point is the high economic development achieved by China (a non-democratic one-party ruling communist state) as compared to India (a democratic multi-party state). According to economists, the lack of democratic participation in countries like China allows for unfettered economic growth.[254]

On the other hand, Socrates believed that democracy without educated masses (educated in the broader sense of being knowledgeable and responsible) would only lead to populism being the criteria to become an elected leader and not competence. This would ultimately lead to a societal demise. This was quoted by Plato in book 10 of The Republic, in Socrates’ conversation with Adimantus.[255] Socrates was of the opinion that the right to vote must not be an indiscriminate right (for example by birth or citizenship), but must be given only to people who thought sufficiently of their choice.

Plato’s The Republic presents a critical view of democracy through the narration of Socrates: «Democracy, which is a charming form of government, full of variety and disorder, and dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequaled alike.»[256] In his work, Plato lists 5 forms of government from best to worst, and lists democracy as the second worst, behind only tyranny, which he implies to be the natural outcome of democracy, arguing that in a democracy everyone puts their own selfish interests ahead of the common good until a tyrant emerges who is strong enough to impose his interest on everyone else. Assuming that the Republic was intended to be a serious critique of the political thought in Athens, Plato argues that only Kallipolis, an aristocracy led by the unwilling philosopher-kings (the wisest men), is a just form of government.[257]

Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, warned Joe Biden, U.S. president, via a phone call that democracy was dying. «Democracies require consensus, and it takes time, and you don’t have the time,» Xi Jinping added.[258]

Popular rule as a façade[edit]

The 20th-century Italian thinkers Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca (independently) argued that democracy was illusory, and served only to mask the reality of elite rule. Indeed, they argued that elite oligarchy is the unbendable law of human nature, due largely to the apathy and division of the masses (as opposed to the drive, initiative and unity of the elites), and that democratic institutions would do no more than shift the exercise of power from oppression to manipulation.[259] As Louis Brandeis once professed, «We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.»[clarification needed].[260]

A study led by Princeton professor Martin Gilens of 1,779 U.S. government decisions concluded that

«elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.»[261]

Mob rule[edit]

James Madison critiqued democracy in Federalist No. 10, arguing that a republic is a preferable form of government, saying: «… democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.» Madison offered that republics were superior to democracies because republics safeguarded against tyranny of the majority, stating in Federalist No. 10: «the same advantage which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic».[230] Thomas Jefferson warned that «an elective despotism is not the government we fought for.»[262]

Political instability[edit]

More recently, democracy is criticised for not offering enough political stability. As governments are frequently elected on and off there tends to be frequent changes in the policies of democratic countries both domestically and internationally. Even if a political party maintains power, vociferous, headline-grabbing protests and harsh criticism from the popular media are often enough to force sudden, unexpected political change. Frequent policy changes with regard to business and immigration are likely to deter investment and so hinder economic growth. For this reason, many people have put forward the idea that democracy is undesirable for a developing country in which economic growth and the reduction of poverty are top priorities.[263]

This opportunist alliance not only has the handicap of having to cater to too many ideologically opposing factions, but it is usually short-lived since any perceived or actual imbalance in the treatment of coalition partners, or changes to leadership in the coalition partners themselves, can very easily result in the coalition partner withdrawing its support from the government.

Biased media has been accused of causing political instability, resulting in the obstruction of democracy, rather than its promotion.[264]

Opposition[edit]

Democracy in modern times has almost always faced opposition from the previously existing government, and many times it has faced opposition from social elites. The implementation of a democratic government within a non-democratic state is typically brought about by democratic revolution.

Democratization[edit]

Banner in Hong Kong asking for democracy, August 2019

Several philosophers and researchers have outlined historical and social factors seen as supporting the evolution of democracy.

Other commentators have mentioned the influence of economic development.[265] In a related theory, Ronald Inglehart suggests that improved living-standards in modern developed countries can convince people that they can take their basic survival for granted, leading to increased emphasis on self-expression values, which correlates closely with democracy.[266][267]