Constitution of the Kingdom of Naples in 1848

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.[1]

When these principles are written down into a single document or set of legal documents, those documents may be said to embody a written constitution; if they are encompassed in a single comprehensive document, it is said to embody a codified constitution. The Constitution of the United Kingdom is a notable example of an uncodified constitution; it is instead written in numerous fundamental Acts of a legislature, court cases, or treaties.[2]

Constitutions concern different levels of organizations, from sovereign countries to companies and unincorporated associations. A treaty that establishes an international organization is also its constitution, in that it would define how that organization is constituted. Within states, a constitution defines the principles upon which the state is based, the procedure in which laws are made and by whom. Some constitutions, especially codified constitutions, also act as limiters of state power, by establishing lines which a state’s rulers cannot cross, such as fundamental rights.

The Constitution of India is the longest written constitution of any country in the world,[3] with 146,385 words[4] in its English-language version,[5] while the Constitution of Monaco is the shortest written constitution with 3,814 words.[6][4] The Constitution of San Marino might be the world’s oldest active written constitution, since some of its core documents have been in operation since 1600, while the Constitution of the United States is the oldest active codified constitution. The historical life expectancy of a constitution since 1789 is approximately 19 years.[7]

Etymology

The term constitution comes through French from the Latin word constitutio, used for regulations and orders, such as the imperial enactments (constitutiones principis: edicta, mandata, decreta, rescripta).[8] Later, the term was widely used in canon law for an important determination, especially a decree issued by the Pope, now referred to as an apostolic constitution.

William Blackstone used the term for significant and egregious violations of public trust, of a nature and extent that the transgression would justify a revolutionary response. The term as used by Blackstone was not for a legal text, nor did he intend to include the later American concept of judicial review: «for that were to set the judicial power above that of the legislature, which would be subversive of all government».[9]

General features

Generally, every modern written constitution confers specific powers on an organization or institutional entity, established upon the primary condition that it abides by the constitution’s limitations. According to Scott Gordon, a political organization is constitutional to the extent that it «contain[s] institutionalized mechanisms of power control for the protection of the interests and liberties of the citizenry, including those that may be in the minority».[10]

Activities of officials within an organization or polity that fall within the constitutional or statutory authority of those officials are termed «within power» (or, in Latin, intra vires); if they do not, they are termed «beyond power» (or, in Latin, ultra vires). For example, a students’ union may be prohibited as an organization from engaging in activities not concerning students; if the union becomes involved in non-student activities, these activities are considered to be ultra vires of the union’s charter, and nobody would be compelled by the charter to follow them. An example from the constitutional law of sovereign states would be a provincial parliament in a federal state trying to legislate in an area that the constitution allocates exclusively to the federal parliament, such as ratifying a treaty. Action that appears to be beyond power may be judicially reviewed and, if found to be beyond power, must cease. Legislation that is found to be beyond power will be «invalid» and of no force; this applies to primary legislation, requiring constitutional authorization, and secondary legislation, ordinarily requiring statutory authorization. In this context, «within power», intra vires, «authorized» and «valid» have the same meaning; as do «beyond power», ultra vires, «not authorized» and «invalid».

In most but not all modern states the constitution has supremacy over ordinary statutory law (see Uncodified constitution below); in such states when an official act is unconstitutional, i.e. it is not a power granted to the government by the constitution, that act is null and void, and the nullification is ab initio, that is, from inception, not from the date of the finding. It was never «law», even though, if it had been a statute or statutory provision, it might have been adopted according to the procedures for adopting legislation. Sometimes the problem is not that a statute is unconstitutional, but that the application of it is, on a particular occasion, and a court may decide that while there are ways it could be applied that are constitutional, that instance was not allowed or legitimate. In such a case, only that application may be ruled unconstitutional. Historically, the remedies for such violations have been petitions for common law writs, such as quo warranto.

Scholars debate whether a constitution must necessarily be autochthonous, resulting from the nations «spirit». Hegel said «A constitution…is the work of centuries; it is the idea, the consciousness of rationality so far as that consciousness is developed in a particular nation.»[11]

History and development

Since 1789, along with the Constitution of the United States of America (U.S. Constitution), which is the oldest and shortest written constitution still in force,[12] close to 800 constitutions have been adopted and subsequently amended around the world by independent states.[13]

In the late 18th century, Thomas Jefferson predicted that a period of 20 years would be the optimal time for any constitution to be still in force, since «the earth belongs to the living, and not to the dead».[14] Indeed, according to recent studies,[13] the average life of any new written constitution is around 19 years. However, a great number of constitutions do not last more than 10 years, and around 10% do not last more than one year, as was the case of the French Constitution of 1791.[13] By contrast, some constitutions, notably that of the United States, have remained in force for several centuries, often without major revision for long periods of time.

The most common reasons for these frequent changes are the political desire for an immediate outcome[clarification needed] and the short time devoted to the constitutional drafting process.[15] A study in 2009 showed that the average time taken to draft a constitution is around 16 months,[16] however there were also some extreme cases registered. For example, the Myanmar 2008 Constitution was being secretly drafted for more than 17 years,[16] whereas at the other extreme, during the drafting of Japan’s 1946 Constitution, the bureaucrats drafted everything in no more than a week. Japan has the oldest unamended constitution in the world.[17] The record for the shortest overall process of drafting, adoption, and ratification of a national constitution belongs to the Romania’s 1938 constitution, which installed a royal dictatorship in less than a month.[18] Studies showed that typically extreme cases where the constitution-making process either takes too long or is extremely short were non-democracies.[19] Constitutional rights are not a specific characteristic of democratic countries. Non-democratic countries have constitutions, such as that of North Korea, which officially grants every citizen, among other rights, the freedom of expression.[20]

Pre-modern constitutions

Ancient

Excavations in modern-day Iraq by Ernest de Sarzec in 1877 found evidence of the earliest known code of justice, issued by the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash c. 2300 BC. Perhaps the earliest prototype for a law of government, this document itself has not yet been discovered; however it is known that it allowed some rights to his citizens. For example, it is known that it relieved tax for widows and orphans, and protected the poor from the usury of the rich.

After that, many governments ruled by special codes of written laws. The oldest such document still known to exist seems to be the Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur (c. 2050 BC). Some of the better-known ancient law codes are the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin, the code of Hammurabi of Babylonia, the Hittite code, the Assyrian code, and Mosaic law.

In 621 BC, a scribe named Draco codified the oral laws of the city-state of Athens; this code prescribed the death penalty for many offenses (thus creating the modern term «draconian» for very strict rules). In 594 BC, Solon, the ruler of Athens, created the new Solonian Constitution. It eased the burden of the workers, and determined that membership of the ruling class was to be based on wealth (plutocracy), rather than on birth (aristocracy). Cleisthenes again reformed the Athenian constitution and set it on a democratic footing in 508 BC.

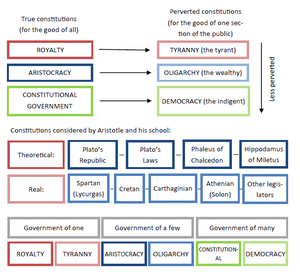

Diagram illustrating the classification of constitutions by Aristotle

Aristotle (c. 350 BC) was the first to make a formal distinction between ordinary law and constitutional law, establishing ideas of constitution and constitutionalism, and attempting to classify different forms of constitutional government. The most basic definition he used to describe a constitution in general terms was «the arrangement of the offices in a state». In his works Constitution of Athens, Politics, and Nicomachean Ethics, he explores different constitutions of his day, including those of Athens, Sparta, and Carthage. He classified both what he regarded as good and what he regarded as bad constitutions, and came to the conclusion that the best constitution was a mixed system including monarchic, aristocratic, and democratic elements. He also distinguished between citizens, who had the right to participate in the state, and non-citizens and slaves, who did not.

The Romans initially codified their constitution in 450 BC as the Twelve Tables. They operated under a series of laws that were added from time to time, but Roman law was not reorganised into a single code until the Codex Theodosianus (438 AD); later, in the Eastern Empire, the Codex repetitæ prælectionis (534) was highly influential throughout Europe. This was followed in the east by the Ecloga of Leo III the Isaurian (740) and the Basilica of Basil I (878).

The Edicts of Ashoka established constitutional principles for the 3rd century BC Maurya king’s rule in India. For constitutional principles almost lost to antiquity, see the code of Manu.

Early Middle Ages

Many of the Germanic peoples that filled the power vacuum left by the Western Roman Empire in the Early Middle Ages codified their laws. One of the first of these Germanic law codes to be written was the Visigothic Code of Euric (471 AD). This was followed by the Lex Burgundionum, applying separate codes for Germans and for Romans; the Pactus Alamannorum; and the Salic Law of the Franks, all written soon after 500. In 506, the Breviarum or «Lex Romana» of Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, adopted and consolidated the Codex Theodosianus together with assorted earlier Roman laws. Systems that appeared somewhat later include the Edictum Rothari of the Lombards (643), the Lex Visigothorum (654), the Lex Alamannorum (730), and the Lex Frisionum (c. 785). These continental codes were all composed in Latin, while Anglo-Saxon was used for those of England, beginning with the Code of Æthelberht of Kent (602). Around 893, Alfred the Great combined this and two other earlier Saxon codes, with various Mosaic and Christian precepts, to produce the Doom book code of laws for England.

Japan’s Seventeen-article constitution written in 604, reportedly by Prince Shōtoku, is an early example of a constitution in Asian political history. Influenced by Buddhist teachings, the document focuses more on social morality than on institutions of government, and remains a notable early attempt at a government constitution.

The Constitution of Medina (Arabic: صحیفة المدینه, Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīna), also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad after his flight (hijra) to Yathrib where he became political leader. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib (later known as Medina), including Muslims, Jews, and pagans.[21][22] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter intertribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina. To this effect it instituted a number of rights and responsibilities for the Muslim, Jewish, and pagan communities of Medina bringing them within the fold of one community – the Ummah.[23] The precise dating of the Constitution of Medina remains debated, but generally scholars agree it was written shortly after the Hijra (622).[24]

In Wales, the Cyfraith Hywel (Law of Hywel) was codified by Hywel Dda c. 942–950.

Middle Ages after 1000

The Pravda Yaroslava, originally combined by Yaroslav the Wise the Grand Prince of Kiev, was granted to Great Novgorod around 1017, and in 1054 was incorporated into the Russkaya Pravda; it became the law for all of Kievan Rus’. It survived only in later editions of the 15th century.

In England, Henry I’s proclamation of the Charter of Liberties in 1100 bound the king for the first time in his treatment of the clergy and the nobility. This idea was extended and refined by the English barony when they forced King John to sign Magna Carta in 1215. The most important single article of the Magna Carta, related to «habeas corpus«, provided that the king was not permitted to imprison, outlaw, exile or kill anyone at a whim – there must be due process of law first. This article, Article 39, of the Magna Carta read:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

This provision became the cornerstone of English liberty after that point. The social contract in the original case was between the king and the nobility, but was gradually extended to all of the people. It led to the system of Constitutional Monarchy, with further reforms shifting the balance of power from the monarchy and nobility to the House of Commons.

The Nomocanon of Saint Sava (Serbian: Законоправило/Zakonopravilo)[25][26][27] was the first Serbian constitution from 1219. St. Sava’s Nomocanon was the compilation of civil law, based on Roman Law, and canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils. Its basic purpose was to organize the functioning of the young Serbian kingdom and the Serbian church. Saint Sava began the work on the Serbian Nomocanon in 1208 while he was at Mount Athos, using The Nomocanon in Fourteen Titles, Synopsis of Stefan the Efesian, Nomocanon of John Scholasticus, and Ecumenical Council documents, which he modified with the canonical commentaries of Aristinos and Joannes Zonaras, local church meetings, rules of the Holy Fathers, the law of Moses, the translation of Prohiron, and the Byzantine emperors’ Novellae (most were taken from Justinian’s Novellae). The Nomocanon was a completely new compilation of civil and canonical regulations, taken from Byzantine sources but completed and reformed by St. Sava to function properly in Serbia. Besides decrees that organized the life of church, there are various norms regarding civil life; most of these were taken from Prohiron. Legal transplants of Roman-Byzantine law became the basis of the Serbian medieval law. The essence of Zakonopravilo was based on Corpus Iuris Civilis.

Stefan Dušan, emperor of Serbs and Greeks, enacted Dušan’s Code (Serbian: Душанов Законик/Dušanov Zakonik)[28] in Serbia, in two state congresses: in 1349 in Skopje and in 1354 in Serres. It regulated all social spheres, so it was the second Serbian constitution, after St. Sava’s Nomocanon (Zakonopravilo). The Code was based on Roman-Byzantine law. The legal transplanting within articles 171 and 172 of Dušan’s Code, which regulated the juridical independence, is notable. They were taken from the Byzantine code Basilika (book VII, 1, 16–17).

In 1222, Hungarian King Andrew II issued the Golden Bull of 1222.

Between 1220 and 1230, a Saxon administrator, Eike von Repgow, composed the Sachsenspiegel, which became the supreme law used in parts of Germany as late as 1900.

Around 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer, ‘Abul Fada’il Ibn al-‘Assal, wrote the Fetha Negest in Arabic. ‘Ibn al-Assal took his laws partly from apostolic writings and Mosaic law and partly from the former Byzantine codes. There are a few historical records claiming that this law code was translated into Ge’ez and entered Ethiopia around 1450 in the reign of Zara Yaqob. Even so, its first recorded use in the function of a constitution (supreme law of the land) is with Sarsa Dengel beginning in 1563. The Fetha Negest remained the supreme law in Ethiopia until 1931, when a modern-style Constitution was first granted by Emperor Haile Selassie I.

Third volume of the compilation of Catalan Constitutions of 1585

In the Principality of Catalonia, the Catalan constitutions were promulgated by the Court from 1283 (or even two centuries before, if Usatges of Barcelona is considered part of the compilation of Constitutions) until 1716, when Philip V of Spain gave the Nueva Planta decrees, finishing with the historical laws of Catalonia. These Constitutions were usually made formally as a royal initiative, but required for its approval or repeal the favorable vote of the Catalan Courts, the medieval antecedent of the modern Parliaments. These laws, like other modern constitutions, had preeminence over other laws, and they could not be contradicted by mere decrees or edicts of the king.

The Kouroukan Founga was a 13th-century charter of the Mali Empire, reconstructed from oral tradition in 1988 by Siriman Kouyaté.[29]

The Golden Bull of 1356 was a decree issued by a Reichstag in Nuremberg headed by Emperor Charles IV that fixed, for a period of more than four hundred years, an important aspect of the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire.

In China, the Hongwu Emperor created and refined a document he called Ancestral Injunctions (first published in 1375, revised twice more before his death in 1398). These rules served as a constitution for the Ming Dynasty for the next 250 years.

The oldest written document still governing a sovereign nation today is that of San Marino.[30] The Leges Statutae Republicae Sancti Marini was written in Latin and consists of six books. The first book, with 62 articles, establishes councils, courts, various executive officers, and the powers assigned to them. The remaining books cover criminal and civil law and judicial procedures and remedies. Written in 1600, the document was based upon the Statuti Comunali (Town Statute) of 1300, itself influenced by the Codex Justinianus, and it remains in force today.

In 1392 the Carta de Logu was legal code of the Giudicato of Arborea promulgated by the giudicessa Eleanor. It was in force in Sardinia until it was superseded by the code of Charles Felix in April 1827. The Carta was a work of great importance in Sardinian history. It was an organic, coherent, and systematic work of legislation encompassing the civil and penal law.

The Gayanashagowa, the oral constitution of the Haudenosaunee nation also known as the Great Law of Peace, established a system of governance as far back as 1190 AD (though perhaps more recently at 1451) in which the Sachems, or tribal chiefs, of the Iroquois League’s member nations made decisions on the basis of universal consensus of all chiefs following discussions that were initiated by a single nation. The position of Sachem descends through families and are allocated by the senior female clan heads, though, prior to the filling of the position, candidacy is ultimately democratically decided by the community itself.[31]

Modern constitutions

In 1634 the Kingdom of Sweden adopted the 1634 Instrument of Government, drawn up under the Lord High Chancellor of Sweden Axel Oxenstierna after the death of king Gustavus Adolphus, it can be seen as the first written constitution adopted by a modern state.

In 1639, the Colony of Connecticut adopted the Fundamental Orders, which was the first North American constitution, and is the basis for every new Connecticut constitution since, and is also the reason for Connecticut’s nickname, «the Constitution State».

The English Protectorate that was set up by Oliver Cromwell after the English Civil War promulgated the first detailed written constitution adopted by a modern state;[32] it was called the Instrument of Government. This formed the basis of government for the short-lived republic from 1653 to 1657 by providing a legal rationale for the increasing power of Cromwell after Parliament consistently failed to govern effectively. Most of the concepts and ideas embedded into modern constitutional theory, especially bicameralism, separation of powers, the written constitution, and judicial review, can be traced back to the experiments of that period.[33]

Drafted by Major-General John Lambert in 1653, the Instrument of Government included elements incorporated from an earlier document «Heads of Proposals»,[34][35] which had been agreed to by the Army Council in 1647, as a set of propositions intended to be a basis for a constitutional settlement after King Charles I was defeated in the First English Civil War. Charles had rejected the propositions, but before the start of the Second Civil War, the Grandees of the New Model Army had presented the Heads of Proposals as their alternative to the more radical Agreement of the People presented by the Agitators and their civilian supporters at the Putney Debates.

On January 4, 1649, the Rump Parliament declared «that the people are, under God, the original of all just power; that the Commons of England, being chosen by and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation».[36]

The Instrument of Government was adopted by Parliament on December 15, 1653, and Oliver Cromwell was installed as Lord Protector on the following day. The constitution set up a state council consisting of 21 members while executive authority was vested in the office of «Lord Protector of the Commonwealth.» This position was designated as a non-hereditary life appointment. The Instrument also required the calling of triennial Parliaments, with each sitting for at least five months.

The Instrument of Government was replaced in May 1657 by England’s second, and last, codified constitution, the Humble Petition and Advice, proposed by Sir Christopher Packe.[37] The Petition offered hereditary monarchy to Oliver Cromwell, asserted Parliament’s control over issuing new taxation, provided an independent council to advise the king and safeguarded «Triennial» meetings of Parliament. A modified version of the Humble Petition with the clause on kingship removed was ratified on 25 May. This finally met its demise in conjunction with the death of Cromwell and the Restoration of the monarchy.

Other examples of European constitutions of this era were the Corsican Constitution of 1755 and the Swedish Constitution of 1772.

All of the British colonies in North America that were to become the 13 original United States, adopted their own constitutions in 1776 and 1777, during the American Revolution (and before the later Articles of Confederation and United States Constitution), with the exceptions of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts adopted its Constitution in 1780, the oldest still-functioning constitution of any U.S. state; while Connecticut and Rhode Island officially continued to operate under their old colonial charters, until they adopted their first state constitutions in 1818 and 1843, respectively.

Democratic constitutions

What is sometimes called the «enlightened constitution» model was developed by philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and John Locke. The model proposed that constitutional governments should be stable, adaptable, accountable, open and should represent the people (i.e., support democracy).[38]

Agreements and Constitutions of Laws and Freedoms of the Zaporizian Host was written in 1710 by Pylyp Orlyk, hetman of the Zaporozhian Host. It was written to establish a free Zaporozhian-Ukrainian Republic, with the support of Charles XII of Sweden. It is notable in that it established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws. This Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council. However, Orlyk’s project for an independent Ukrainian State never materialized, and his constitution, written in exile, never went into effect.

Corsican Constitutions of 1755 and 1794 were inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The latter introduced universal suffrage for property owners.

The Swedish constitution of 1772 was enacted under King Gustavus III and was inspired by the separation of powers by Montesquieu. The king also cherished other enlightenment ideas (as an enlighted despot) and repealed torture, liberated agricultural trade, diminished the use of the death penalty and instituted a form of religious freedom. The constitution was commended by Voltaire.[39][40][41]

The United States Constitution, ratified June 21, 1788, was influenced by the writings of Polybius, Locke, Montesquieu, and others. The document became a benchmark for republicanism and codified constitutions written thereafter.[42]

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Constitution was passed on May 3, 1791.[43][44][45] Its draft was developed by the leading minds of the Enlightenment in Poland such as King Stanislaw August Poniatowski, Stanisław Staszic, Scipione Piattoli, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj.[46] It was adopted by the Great Sejm and is considered the first constitution of its kind in Europe and the world’s second oldest one after the American Constitution.[47]

Another landmark document was the French Constitution of 1791.

The 1811 Constitution of Venezuela was the first Constitution of Venezuela and Latin America, promulgated and drafted by Cristóbal Mendoza[48] and Juan Germán Roscio and in Caracas. It established a federal government but was repealed one year later.[49]

On March 19, the Spanish Constitution of 1812 was ratified by a parliament gathered in Cadiz, the only Spanish continental city which was safe from French occupation. The Spanish Constitution served as a model for other liberal constitutions of several South European and Latin American nations, for example, the Portuguese Constitution of 1822, constitutions of various Italian states during Carbonari revolts (i.e., in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), the Norwegian constitution of 1814, or the Mexican Constitution of 1824.[50]

In Brazil, the Constitution of 1824 expressed the option for the monarchy as political system after Brazilian Independence. The leader of the national emancipation process was the Portuguese prince Pedro I, elder son of the king of Portugal. Pedro was crowned in 1822 as first emperor of Brazil. The country was ruled by Constitutional monarchy until 1889, when it adopted the Republican model.

In Denmark, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the absolute monarchy lost its personal possession of Norway to Sweden. Sweden had already enacted its 1809 Instrument of Government, which saw the division of power between the Riksdag, the king and the judiciary.[51] However the Norwegians managed to infuse a radically democratic and liberal constitution in 1814, adopting many facets from the American constitution and the revolutionary French ones, but maintaining a hereditary monarch limited by the constitution, like the Spanish one.

The first Swiss Federal Constitution was put in force in September 1848 (with official revisions in 1878, 1891, 1949, 1971, 1982 and 1999).

The Serbian revolution initially led to a proclamation of a proto-constitution in 1811; the full-fledged Constitution of Serbia followed few decades later, in 1835. The first Serbian constitution (Sretenjski ustav) was adopted at the national assembly in Kragujevac on February 15, 1835.

The Constitution of Canada came into force on July 1, 1867, as the British North America Act, an act of the British Parliament. Over a century later, the BNA Act was patriated to the Canadian Parliament and augmented with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[52] Apart from the Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982, Canada’s constitution also has unwritten elements based in common law and convention.[53][54]

Principles of constitutional design

After tribal people first began to live in cities and establish nations, many of these functioned according to unwritten customs, while some developed autocratic, even tyrannical monarchs, who ruled by decree, or mere personal whim. Such rule led some thinkers to take the position that what mattered was not the design of governmental institutions and operations, as much as the character of the rulers. This view can be seen in Plato, who called for rule by «philosopher-kings».[55] Later writers, such as Aristotle, Cicero and Plutarch, would examine designs for government from a legal and historical standpoint.

The Renaissance brought a series of political philosophers who wrote implied criticisms of the practices of monarchs and sought to identify principles of constitutional design that would be likely to yield more effective and just governance from their viewpoints. This began with revival of the Roman law of nations concept[56] and its application to the relations among nations, and they sought to establish customary «laws of war and peace»[57] to ameliorate wars and make them less likely. This led to considerations of what authority monarchs or other officials have and don’t have, from where that authority derives, and the remedies for the abuse of such authority.[58]

A seminal juncture in this line of discourse arose in England from the Civil War, the Cromwellian Protectorate, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, the Levellers, John Milton, and James Harrington, leading to the debate between Robert Filmer, arguing for the divine right of monarchs, on the one side, and on the other, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke. What arose from the latter was a concept of government being erected on the foundations of first, a state of nature governed by natural laws, then a state of society, established by a social contract or compact, which bring underlying natural or social laws, before governments are formally established on them as foundations.

Along the way several writers examined how the design of government was important, even if the government were headed by a monarch. They also classified various historical examples of governmental designs, typically into democracies, aristocracies, or monarchies, and considered how just and effective each tended to be and why, and how the advantages of each might be obtained by combining elements of each into a more complex design that balanced competing tendencies. Some, such as Montesquieu, also examined how the functions of government, such as legislative, executive, and judicial, might appropriately be separated into branches. The prevailing theme among these writers was that the design of constitutions is not completely arbitrary or a matter of taste. They generally held that there are underlying principles of design that constrain all constitutions for every polity or organization. Each built on the ideas of those before concerning what those principles might be.

The later writings of Orestes Brownson[59] would try to explain what constitutional designers were trying to do. According to Brownson there are, in a sense, three «constitutions» involved: The first the constitution of nature that includes all of what was called «natural law». The second is the constitution of society, an unwritten and commonly understood set of rules for the society formed by a social contract before it establishes a government, by which it establishes the third, a constitution of government. The second would include such elements as the making of decisions by public conventions called by public notice and conducted by established rules of procedure. Each constitution must be consistent with, and derive its authority from, the ones before it, as well as from a historical act of society formation or constitutional ratification. Brownson argued that a state is a society with effective dominion over a well-defined territory, that consent to a well-designed constitution of government arises from presence on that territory, and that it is possible for provisions of a written constitution of government to be «unconstitutional» if they are inconsistent with the constitutions of nature or society. Brownson argued that it is not ratification alone that makes a written constitution of government legitimate, but that it must also be competently designed and applied.

Other writers[60] have argued that such considerations apply not only to all national constitutions of government, but also to the constitutions of private organizations, that it is not an accident that the constitutions that tend to satisfy their members contain certain elements, as a minimum, or that their provisions tend to become very similar as they are amended after experience with their use. Provisions that give rise to certain kinds of questions are seen to need additional provisions for how to resolve those questions, and provisions that offer no course of action may best be omitted and left to policy decisions. Provisions that conflict with what Brownson and others can discern are the underlying «constitutions» of nature and society tend to be difficult or impossible to execute, or to lead to unresolvable disputes.

Constitutional design has been treated as a kind of metagame in which play consists of finding the best design and provisions for a written constitution that will be the rules for the game of government, and that will be most likely to optimize a balance of the utilities of justice, liberty, and security. An example is the metagame Nomic.[61]

Political economy theory regards constitutions as coordination devices that help citizens to prevent rulers from abusing power. If the citizenry can coordinate a response to police government officials in the face of a constitutional fault, then the government have the incentives to honor the rights that the constitution guarantees.[62] An alternative view considers that constitutions are not enforced by the citizens at-large, but rather by the administrative powers of the state. Because rulers cannot themselves implement their policies, they need to rely on a set of organizations (armies, courts, police agencies, tax collectors) to implement it. In this position, they can directly sanction the government by refusing to cooperate, disabling the authority of the rulers. Therefore, constitutions could be characterized by a self-enforcing equilibria between the rulers and powerful administrators.[63]

Key features

Most commonly, the term constitution refers to a set of rules and principles that define the nature and extent of government. Most constitutions seek to regulate the relationship between institutions of the state, in a basic sense the relationship between the executive, legislature and the judiciary, but also the relationship of institutions within those branches. For example, executive branches can be divided into a head of government, government departments/ministries, executive agencies and a civil service/administration. Most constitutions also attempt to define the relationship between individuals and the state, and to establish the broad rights of individual citizens. It is thus the most basic law of a territory from which all the other laws and rules are hierarchically derived; in some territories it is in fact called «Basic Law».

Classification

Classification

| Type | Form | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Codified | In single act (document) | Most of the world (first: United States) |

| Uncodified | Fully written (in few documents) | San Marino, Israel, Saudi Arabia |

| Partially unwritten (see constitutional convention) | Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom |

Codification

A fundamental classification is codification or lack of codification. A codified constitution is one that is contained in a single document, which is the single source of constitutional law in a state. An uncodified constitution is one that is not contained in a single document, consisting of several different sources, which may be written or unwritten; see constitutional convention.

Codified constitution

Most states in the world have codified constitutions.

Codified constitutions are often the product of some dramatic political change, such as a revolution. The process by which a country adopts a constitution is closely tied to the historical and political context driving this fundamental change. The legitimacy (and often the longevity) of codified constitutions has often been tied to the process by which they are initially adopted and some scholars have pointed out that high constitutional turnover within a given country may itself be detrimental to separation of powers and the rule of law.

States that have codified constitutions normally give the constitution supremacy over ordinary statute law. That is, if there is any conflict between a legal statute and the codified constitution, all or part of the statute can be declared ultra vires by a court, and struck down as unconstitutional. In addition, exceptional procedures are often required to amend a constitution. These procedures may include: convocation of a special constituent assembly or constitutional convention, requiring a supermajority of legislators’ votes, approval in two terms of parliament, the consent of regional legislatures, a referendum process, and/or other procedures that make amending a constitution more difficult than passing a simple law.

Constitutions may also provide that their most basic principles can never be abolished, even by amendment. In case a formally valid amendment of a constitution infringes these principles protected against any amendment, it may constitute a so-called unconstitutional constitutional law.

Codified constitutions normally consist of a ceremonial preamble, which sets forth the goals of the state and the motivation for the constitution, and several articles containing the substantive provisions. The preamble, which is omitted in some constitutions, may contain a reference to God and/or to fundamental values of the state such as liberty, democracy or human rights. In ethnic nation-states such as Estonia, the mission of the state can be defined as preserving a specific nation, language and culture.

Uncodified constitution

As of 2017 only two sovereign states, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, have wholly uncodified constitutions. The Basic Laws of Israel have since 1950 been intended to be the basis for a constitution, but as of 2017 it had not been drafted. The various Laws are considered to have precedence over other laws, and give the procedure by which they can be amended, typically by a simple majority of members of the Knesset (parliament).[64]

Uncodified constitutions are the product of an «evolution» of laws and conventions over centuries (such as in the Westminster System that developed in Britain). By contrast to codified constitutions, uncodified constitutions include both written sources – e.g. constitutional statutes enacted by the Parliament – and unwritten sources – constitutional conventions, observation of precedents, royal prerogatives, customs and traditions, such as holding general elections on Thursdays; together these constitute British constitutional law.

Mixed constitutions

Some constitutions are largely, but not wholly, codified. For example, in the Constitution of Australia, most of its fundamental political principles and regulations concerning the relationship between branches of government, and concerning the government and the individual are codified in a single document, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia. However, the presence of statutes with constitutional significance, namely the Statute of Westminster, as adopted by the Commonwealth in the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942, and the Australia Act 1986 means that Australia’s constitution is not contained in a single constitutional document.[citation needed] It means the Constitution of Australia is uncodified,[dubious – discuss] it also contains constitutional conventions, thus is partially unwritten.

The Constitution of Canada resulted from the passage of several British North America Acts from 1867 to the Canada Act 1982, the act that formally severed British Parliament’s ability to amend the Canadian constitution. The Canadian constitution includes specific legislative acts as mentioned in section 52(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982. However, some documents not explicitly listed in section 52(2) are also considered constitutional documents in Canada, entrenched via reference; such as the Proclamation of 1763. Although Canada’s constitution includes a number of different statutes, amendments, and references, some constitutional rules that exist in Canada is derived from unwritten sources and constitutional conventions.

The terms written constitution and codified constitution are often used interchangeably, as are unwritten constitution and uncodified constitution, although this usage is technically inaccurate. A codified constitution is a single document; states that do not have such a document have uncodified, but not entirely unwritten, constitutions, since much of an uncodified constitution is usually written in laws such as the Basic Laws of Israel and the Parliament Acts of the United Kingdom. Uncodified constitutions largely lack protection against amendment by the government of the time. For example, the U.K. Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 legislated by simple majority for strictly fixed-term parliaments; until then the ruling party could call a general election at any convenient time up to the maximum term of five years. This change would require a constitutional amendment in most nations.

Amendments

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, they can be appended to the constitution as supplemental additions (codicils), thus changing the frame of government without altering the existing text of the document.

Most constitutions require that amendments cannot be enacted unless they have passed a special procedure that is more stringent than that required of ordinary legislation.

Methods of amending

| Approval by | Majority needed [clarification needed] |

Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Legislature (unicameral, joint session or lower house only) | >50% + >50% after an election | Iceland, Sweden |

| >50% + 3/5 after an election | Estonia, Greece | |

| 3/5 + >50% after an election | Greece | |

| 3/5 | France, Senegal, Slovakia | |

| 2/3 | Afghanistan, Angola, Armenia, Austria, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Djibouti, Ecuador, Honduras, Laos, Libya, Malawi, North Korea, North Macedonia, Norway, Palestine, Portugal, Qatar, Samoa, São Tomé and Príncipe, Serbia, Singapore, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Yemen | |

| >50% + 2/3 after an election | Ukraine | |

| 2/3 + 2/3 after an election | Belgium | |

| 3/4 | Bulgaria, Solomon Islands (in some cases) | |

| 4/5 | Estonia, Portugal (in the five years following the last amendment) | |

| Legislature + referendum | >50% + >50% | Djibouti, Ecuador, Venezuela |

| >50% before and after an election + >50% | Denmark | |

| 3/5 + >50% | Russia, Turkey | |

| 2/3 + >50% | Albania, Andorra, Armenia (some amendments), Egypt, Slovenia, Tunisia, Uganda, Yemen (some amendments), Zambia | |

| 2/3 + >60% | Seychelles | |

| 3/4 + >50% | Romania | |

| 3/4 + >50% of eligible voters | Taiwan | |

| 2/3 + 2/3 | Namibia, Sierra Leone | |

| 3/4 + 3/4 | Fiji | |

| Legislature + sub-national legislatures | 2/3 + >50% | Mexico |

| 2/3 + 2/3 | Ethiopia | |

| Lower house + upper house | 2/3 + >50% | Poland, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| 2/3 + 2/3 | Bahrain, Germany, India, Italy, Jordan, Namibia, Netherlands, Pakistan, Somalia, Zimbabwe | |

| 3/5 + 3/5 | Brazil, Czech Republic | |

| 3/4 + 3/4 | Kazakhstan | |

| Lower house + upper house + joint session | >50% + >50% + 2/3 | Gabon |

| Either house of legislature + joint session | 2/3 + 2/3 | Haiti |

| Lower house + upper house + referendum | >50% + >50% + >50% | Algeria, France, Ireland, Italy |

| >50% + >50% + >50% (electors in majority of states/cantons)+ >50% (electors) | Australia, Switzerland | |

| 2/3 + 2/3 + >50% | Japan, Romania, Zimbabwe (some cases) | |

| 2/3 + >50% + 2/3 | Antigua and Barbuda | |

| 2/3 + >50% + >50% | Poland (some cases)[65][66] | |

| 3/4 + 3/4 >50% | Madagascar | |

| Lower house + upper house + sub-national legislatures | >50% + >50% + 2/3 | Canada |

| 2/3 + 2/3 + >50% | India (in some cases) | |

| 2/3 + 2/3 + 3/4 | United States | |

| 2/3 + 100% | Ethiopia | |

| Referendum | >50% | Estonia, Gabon, Kazakhstan, Malawi, Palau, Philippines, Senegal, Serbia (in some cases), Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

| Sub-national legislatures | 2/3 | Russia |

| 3/4 | United States | |

| Constitutional convention | Argentina | |

| 2/3 | Bulgaria (some amendments) |

Some countries are listed under more than one method because alternative procedures may be used.

Entrenched clauses

An entrenched clause or entrenchment clause of a basic law or constitution is a provision that makes certain amendments either more difficult or impossible to pass, making such amendments inadmissible. Overriding an entrenched clause may require a supermajority, a referendum, or the consent of the minority party. For example, the U.S. Constitution has an entrenched clause that prohibits abolishing equal suffrage of the States within the Senate without their consent. The term eternity clause is used in a similar manner in the constitutions of the Czech Republic,[67] Germany, Turkey, Greece,[68] Italy,[69] Morocco,[70] the Islamic Republic of Iran, Brazil and Norway.[69] India doesn’t contain specific provisions on entrenched clauses but the basic structure doctrine makes it impossible for certain basic features of the Constitution to be altered or destroyed by the Parliament of India through an amendment.[71] Colombia also doesn’t have explicit entrenched clauses but has similarly put a substantive limit on amending fundamental principles of their constitution through judicial interpretations.[69]

Constitutional rights and duties

Constitutions include various rights and duties. These include the following:

- Duty to pay taxes[72]

- Duty to serve in the military[73]

- Duty to work[74]

- Right to vote[75]

- Freedom of assembly[76]

- Freedom of association[77]

- Freedom of expression[78]

- Freedom of movement[79]

- Freedom of thought[80]

- Freedom of the press[80]

- Freedom of religion[81]

- Right to dignity[82]

- Right to civil marriage[83]

- Right to petition[84]

- Right to academic freedom[85]

- Right to bear arms[86]

- Right to conscientious objection[87]

- Right to a fair trial[88]

- Right to personal development[89]

- Right to start a family[90]

- Right to information[91]

- Right to marriage[92]

- Right of revolution[93]

- Right to privacy[94]

- Right to protect one’s reputation[95]

- Right to renounce citizenship[96]

- Rights of children[97]

- Rights of debtors[98]

Separation of powers

Constitutions usually explicitly divide power between various branches of government. The standard model, described by the Baron de Montesquieu, involves three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. Some constitutions include additional branches, such as an auditory branch. Constitutions vary extensively as to the degree of separation of powers between these branches.

Accountability

In presidential and semi-presidential systems of government, department secretaries/ministers are accountable to the president, who has patronage powers to appoint and dismiss ministers. The president is accountable to the people in an election.

In parliamentary systems, Cabinet Ministers are accountable to Parliament, but it is the prime minister who appoints and dismisses them. In the case of the United Kingdom and other countries with a monarchy, it is the monarch who appoints and dismisses ministers, on the advice of the prime minister. In turn the prime minister will resign if the government loses the confidence of the parliament (or a part of it). Confidence can be lost if the government loses a vote of no confidence or, depending on the country,[99] loses a particularly important vote in parliament, such as vote on the budget. When a government loses confidence, it stays in office until a new government is formed; something which normally but not necessarily required the holding of a general election.

Other independent institutions

Other independent institutions which some constitutions have set out include a central bank,[100] an anti-corruption commission,[101] an electoral commission,[102] a judicial oversight body,[103] a human rights commission,[104] a media commission,[105] an ombudsman,[106] and a truth and reconciliation commission.[107]

Power structure

Constitutions also establish where sovereignty is located in the state. There are three basic types of distribution of sovereignty according to the degree of centralisation of power: unitary, federal, and confederal. The distinction is not absolute.

In a unitary state, sovereignty resides in the state itself, and the constitution determines this. The territory of the state may be divided into regions, but they are not sovereign and are subordinate to the state. In the UK, the constitutional doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty dictates that sovereignty is ultimately contained at the centre. Some powers have been devolved to Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales (but not England). Some unitary states (Spain is an example) devolve more and more power to sub-national governments until the state functions in practice much like a federal state.

A federal state has a central structure with at most a small amount of territory mainly containing the institutions of the federal government, and several regions (called states, provinces, etc.) which compose the territory of the whole state. Sovereignty is divided between the centre and the constituent regions. The constitutions of Canada and the United States establish federal states, with power divided between the federal government and the provinces or states. Each of the regions may in turn have its own constitution (of unitary nature).

A confederal state comprises again several regions, but the central structure has only limited coordinating power, and sovereignty is located in the regions. Confederal constitutions are rare, and there is often dispute to whether so-called «confederal» states are actually federal.

To some extent a group of states which do not constitute a federation as such may by treaties and accords give up parts of their sovereignty to a supranational entity. For example, the countries constituting the European Union have agreed to abide by some Union-wide measures which restrict their absolute sovereignty in some ways, e.g., the use of the metric system of measurement instead of national units previously used.

State of emergency

Many constitutions allow the declaration under exceptional circumstances of some form of state of emergency during which some rights and guarantees are suspended. This provision can be and has been abused to allow a government to suppress dissent without regard for human rights – see the article on state of emergency.

Facade constitutions

Italian political theorist Giovanni Sartori noted the existence of national constitutions which are a facade for authoritarian sources of power. While such documents may express respect for human rights or establish an independent judiciary, they may be ignored when the government feels threatened, or never put into practice. An extreme example was the Constitution of the Soviet Union that on paper supported freedom of assembly and freedom of speech; however, citizens who transgressed unwritten limits were summarily imprisoned. The example demonstrates that the protections and benefits of a constitution are ultimately provided not through its written terms but through deference by government and society to its principles. A constitution may change from being real to a facade and back again as democratic and autocratic governments succeed each other.

Constitutional courts

Constitutions are often, but by no means always, protected by a legal body whose job it is to interpret those constitutions and, where applicable, declare void executive and legislative acts which infringe the constitution. In some countries, such as Germany, this function is carried out by a dedicated constitutional court which performs this (and only this) function. In other countries, such as Ireland, the ordinary courts may perform this function in addition to their other responsibilities. While elsewhere, like in the United Kingdom, the concept of declaring an act to be unconstitutional does not exist.

A constitutional violation is an action or legislative act that is judged by a constitutional court to be contrary to the constitution, that is, unconstitutional. An example of constitutional violation by the executive could be a public office holder who acts outside the powers granted to that office by a constitution. An example of constitutional violation by the legislature is an attempt to pass a law that would contradict the constitution, without first going through the proper constitutional amendment process.

Some countries, mainly those with uncodified constitutions, have no such courts at all. For example, the United Kingdom has traditionally operated under the principle of parliamentary sovereignty under which the laws passed by United Kingdom Parliament could not be questioned by the courts.

See also

- Basic law, equivalent in some countries, often for a temporary constitution

- Apostolic constitution (a class of Catholic Church documents)

- Consent of the governed

- Constitution of the Roman Republic

- Constitutional amendment

- Constitutional court

- Constitutional crisis

- Constitutional economics

- Constitutionalism

- Corporate constitutional documents

- International constitutional law

- Judicial activism

- Judicial restraint

- Judicial review

- Philosophy of law

- Rule of law

- Rule according to higher law

Judicial philosophies of constitutional interpretation (note: generally specific to United States constitutional law)

- List of national constitutions

- Originalism

- Strict constructionism

- Textualism

- Proposed European Union constitution

- Treaty of Lisbon (adopts same changes, but without constitutional name)

- United Nations Charter

Further reading

- Zachary Elkins and Tom Ginsburg. 2021. «What Can We Learn from Written Constitutions?» Annual Review of Political Science.

References

- ^ The New Oxford American Dictionary, Second Edn., Erin McKean (editor), 2051 pp., 2005, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517077-6.

- ^ R (HS2 Action Alliance Ltd) v Secretary of State for Transport [2014] UKSC 3 Archived March 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, [207]

- ^ Pylee, M.V. (1997). India’s Constitution. S. Chand & Co. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-219-0403-2.

- ^ a b «Constitution Rankings». Comparative Constitutions Project. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ «Constitution of India». Ministry of Law and Justice of India. July 2008. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ «Monaco 1962 (rev. 2002)». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ Elkins, Zachary; Ginsburg, Tom; Melton, James (2009), «Conceptualizing Constitutions», The Endurance of National Constitutions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–64, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511817595.004, ISBN 978-0-511-81759-5

- ^ Mousourakis, George (December 12, 2003). The Historical and Institutional Context of Roman Law. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754621140 – via Google Books.

- ^ Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford University Press. May 17, 2012. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-19-957861-0.

- ^ Gordon, Scott (1999). Controlling the State: Constitutionalism from Ancient Athens to Today. Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-674-16987-6.

- ^ Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law. Oxford University Press. May 17, 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-957861-0.

- ^ (Jordan, Terry L. (2013). The U.S. Constitution and Fascinating Facts About It (8th ed.). Naperville, IL: Oak Hill Publishing Company. p. 25.)

- ^ a b c (Zachary, Elkins; Ginsburg, Tom; Melton, James (2009). The Endurance of National Constitutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.)

- ^ («Thomas Jefferson to James Madison». Popular Basis of Political Authority. September 6, 1789. pp. 392–97. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2015.)

- ^ (Ginsburg, Tom; Melton, James. «Innovation in Constitutional Rights» (PDF). NYU. Draft for presentation at NYU Workshop on Law, Economics and Politics. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2015.)

- ^ a b (Ginsburg, Tom; Zachary, Elkins; Blount, Justin (2009). «Does the Process of Constitution-Making Matter?» (PDF). University of Chicago Law School. Chicago, IL: Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci.5. pp. 201–23 [209]. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2015.)

- ^ «The Anomalous Life of the Japanese Constitution». Nippon.com. August 15, 2017. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ (Ginsburg, Tom; Zachary, Elkins; Blount, Justin (2009). «Does the Process of Constitution-Making Matter?» (PDF). University of Chicago Law School. Chicago, IL: Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci.5. pp. 201–23 [204]. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2015.)

- ^ (Ginsburg, Tom; Zachary, Elkins; Blount, Justin (2009). «Does the Process of Constitution-Making Matter?» (PDF). University of Chicago Law School. Chicago, IL: Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci.5:201–23. p. 203. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2015.)

- ^ (Chilton, Adam S.; Versteeg, Mila (2014). «Do Constitutional Rights Make a Difference?». Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics. Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Working Paper No. 694. SSRN 2477530.)

- ^ See:

- Reuven Firestone, Jihād: the origin of holy war in Islam (1999) p. 118;

- «Muhammad», Encyclopedia of Islam Online

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina and R.B. Serjeant «The Constitution of Medina.» Islamic Quarterly 8 (1964) p. 4.

- ^ R.B. Serjeant, The Sunnah Jami’ah, pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrim of Yathrib: Analysis and translation of the documents comprised in the so-called «Constitution of Medina.» Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 41, No. 1. (1978), p. 4.

- ^ Watt. Muhammad at Medina. pp. 227–228 Watt argues that the initial agreement was shortly after the hijra and the document was amended at a later date specifically after the battle of Badr (AH [anno hijra] 2, = AD 624). Serjeant argues that the constitution is in fact 8 different treaties which can be dated according to events as they transpired in Medina with the first treaty being written shortly after Muhammad’s arrival. R. B. Serjeant. «The Sunnah Jâmi’ah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Tahrîm of Yathrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the so called ‘Constitution of Medina’.» in The Life of Muhammad: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World: Volume iv. Ed. Uri Rubin. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1998, p. 151 and see same article in BSOAS 41 (1978): 18 ff. See also Caetani. Annali dell’Islam, Volume I. Milano: Hoepli, 1905, p. 393. Julius Wellhausen. Skizzen und Vorabeiten, IV, Berlin: Reimer, 1889, pp. 82ff who argue that the document is a single treaty agreed upon shortly after the hijra. Wellhausen argues that it belongs to the first year of Muhammad’s residence in Medina, before the battle of Badr in 2/624. Wellhausen bases this judgement on three considerations; first Muhammad is very diffident about his own position, he accepts the Pagan tribes within the Umma, and maintains the Jewish clans as clients of the Ansars see Wellhausen, Excursus, p. 158. Even Moshe Gil a skeptic of Islamic history argues that it was written within 5 months of Muhammad’s arrival in Medina. Moshe Gil. «The Constitution of Medina: A Reconsideration.» Israel Oriental Studies 4 (1974): p. 45.

- ^ The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century John Van Antwerp Fine Archived December 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Google Books. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Metasearch Search Engine Archived October 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Search.com. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ «Short Term Loans» (PDF). Archived from the original on November 25, 2011.

- ^ Dusanov Zakonik Archived August 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Dusanov Zakonik. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Mangoné Naing, SAH/D(2006)563 The Kurukan Fuga Charter: An example of an Endogenous Governance Mechanism for Conflict Prevention Archived October 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Inter-generational Forum on Endogenous Governance in West Africa organised by Sahel and West Africa Club / OECD, Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), June 26 to 28, 2006. pp. 71–82.

- ^ «The United States has «the longest surviving constitution»«. PolitiFact.com. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Tooker E (1990). «The United States Constitution and the Iroquois League». In Clifton JA (ed.). The Invented Indian: cultural fictions and government policies. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. pp. 107–128. ISBN 978-1-56000-745-6.

- ^ [1]Archived May 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Instrument of Government (England [1653]). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Francis D. Wormuth (1949). The Origins of Modern Constitutionalism. Harper & Brothers.

- ^ Tyacke p. 69

- ^ Farr pp. 80,81 Archived December 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. See Declaration of Representation of June 14, 1647

- ^ Fritze, Ronald H. & Robison, William B. (1996). Historical dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-28391-5 p. 228 Archived December 27, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lee, Sidney (1903), Dictionary of National Biography Index and Epitome p. 991.

- ^ constitution (politics and law) Archived April 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- ^ Borg, Ivan; Nordell, Erik; Rodhe, Sten; Nordell, Erik (1967). Historia för gymnasiet. Årskurs 1 (in Swedish) (4th ed.). Stockholm: AV Carlsons. p. 410. SELIBR 10259755.

- ^ Bäcklin, Martin, ed. (1965). Historia för gymnasiet: allmän och nordisk historia efter år 1000 (in Swedish) (3rd ed.). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. pp. 283–284. SELIBR 1610850.

- ^ Borg, Ivan; Nordell, Erik; Rodhe, Sten; Nordell, Erik (1967). Historia för gymnasiet. Årskurs 1 (in Swedish) (4th ed.). Stockholm: AV Carlsons. pp. 412–413. SELIBR 10259755.

- ^ «Goodlatte says U.S. has the oldest working national constitution». PolitiFact.

- ^ Blaustein, Albert (January 1993). Constitutions of the World. Fred B. Rothman & Company. ISBN 978-0-8377-0362-6.

- ^ Isaac Kramnick, Introduction, Madison, James (1987). The Federalist Papers. Penguin Classics. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-14-044495-7.

May second oldest constitution.

- ^ «The first European country to follow the U.S. example was Poland in 1791.» John Markoff, Waves of Democracy, 1996, ISBN 0-8039-9019-7, p. 121.

- ^ «The Polish Constitution of May 3rd – a milestone in the history of law and the rise of democracy». Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ «The Constitution of May 3 (1791)» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ Briceño Perozo, Mario. «Mendoza, Cristóbal de» in Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela, Vol. 3. Caracas: Fundación Polar, 1999. ISBN 980-6397-37-1

- ^ «1811 Miranda Declares Independence in Venezuela and Civil War Begins». War and Nation: identity and the process of state-building in South America (1800-1840). Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). A History of Spain and Portugal: Eighteenth Century to Franco. Vol. 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-299-06270-5.

The Spanish pattern of conspiracy and revolt by liberal army officers … was emulated in both Portugal and Italy. In the wake of Riego’s successful rebellion, the first and only pronunciamiento in Italian history was carried out by liberal officers in the kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Spanish-style military conspiracy also helped to inspire the beginning of the Russian revolutionary movement with the revolt of the Decembrist army officers in 1825. Italian liberalism in 1820–1821 relied on junior officers and the provincial middle classes, essentially the same social base as in Spain. It even used a Hispanized political vocabulary, for it was led by giunte (juntas), appointed local capi politici (jefes políticos), used the terms of liberali and servili (emulating the Spanish word serviles applied to supporters of absolutism), and in the end talked of resisting by means of a guerrilla. For both Portuguese and Italian liberals of these years, the Spanish constitution of 1812 remained the standard document of reference.

- ^ Lewin, Leif (May 1, 2007). «Majoritarian and Consensus Democracy: the Swedish Experience». Scandinavian Political Studies. 21 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1998.tb00012.x.

- ^ «Constitution Act, 1982, s. 60».

- ^ The Constitutional Law Group, Canadian Constitutional Law. 3rd ed. Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Ltd., 2003, p. 5

- ^ Saul, John Ralston. The Doubter’s Companion: A Dictionary of Aggressive Common Sense. Toronto: Penguin, 1995.

- ^ Aristotle, by Francesco Hayez

- ^ Relectiones Archived December 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Franciscus de Victoria (lect. 1532, first pub. 1557).

- ^ The Law of War and Peace, Hugo Grotius (1625)

- ^ Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos (Defense of Liberty Against Tyrants) Archived February 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, «Junius Brutus» (Orig. Fr. 1581, Eng. tr. 1622, 1688)

- ^ The American Republic: its Constitution, Tendencies, and Destiny Archived October 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, O.A. Brownson (1866)

- ^ Principles of Constitutional Design, Donald S. Lutz (2006) ISBN 0-521-86168-3

- ^ The Paradox of Self-Amendment Archived September 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, by Peter Suber (1990) ISBN 0-8204-1212-0

- ^ Weingast, Barry R. (Summer 2005). «The Constitutional Dilemma of Economic Liberty». Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (3): 89–108. doi:10.1257/089533005774357815.

- ^ González de Lara, Yadira; Greif, Avner; Jha, Saumitra (May 2008). «The Administrative Foundations of Self-Enforcing Constitutions». The American Economic Review. 98 (2): 105–109. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.386.3870. doi:10.1257/aer.98.2.105.

- ^ «Basic Laws – Introduction». The Knesset. 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2017. Article gives information on the procedures for amending each of the Basic Laws of Israel.

- ^ «The Constitution of the Republic of Poland». www.sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ «Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej». www.sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kyriaki Topidi and Alexander H.E. Morawa (2010). Constitutional Evolution in Central and Eastern Europe (Studies in Modern Law and Policy). p. 105. ISBN 978-1409403272.

- ^ The official English language translation of the Greek Constitution as of May 27, 2008 Archived November 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Article 110 §1, p. 124, source: Hellenic Parliament, «The provisions of the Constitution shall be subject to revision with the exception of those which determine the form of government as a Parliamentary Republic and those of articles 2 paragraph 1, 4 paragraphs 1, 4 and 7 , 5 paragraphs 1 and 3, 13 paragraph 1, and 26.»

- ^ a b c Joel Colón-Ríos (2012). Weak Constitutionalism: Democratic Legitimacy and the Question of Constituent Power (Routledge Research in Constitutional Law. p. 67. ISBN 978-0415671903.

- ^ Gerhard Robbers (2006). Encyclopedia of World Constitutions. p. 626. ISBN 978-0816060788.

- ^ «The basic features». The Hindu. September 26, 2004. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ «Read about «Duty to pay taxes» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Duty to serve in the military» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Duty to work» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Claim of universal suffrage» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Freedom of assembly» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Freedom of association» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Freedom of expression» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Freedom of movement» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b «Read about «Freedom of opinion/thought/conscience» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Freedom of religion» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Human dignity» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Provision for civil marriage» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right of petition» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to academic freedom» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to bear arms» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to conscientious objection» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to fair trial» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to development of personality» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to found a family» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to information» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to marry» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to overthrow government» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to privacy» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to protect one’s reputation» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Right to renounce citizenship» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Rights of children» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Rights of debtors» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ A synchronic comparative perspective were before the founding fathers of Italian Constitution, when they were faced with the question of bicameralism and related issues of confidence and the legislative procedure, Buonomo, Giampiero (2013). «Il bicameralismo tra due modelli mancati». L’Ago e Il Filo Edizione Online. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- ^ «Read about «Central bank» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Counter corruption commission» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Electoral commission» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Establishment of judicial council» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Human rights commission» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Media commission» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Ombudsman» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ «Read about «Truth and reconciliation commission» on Constitute». www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

External links

- Constitute, an indexed and searchable database of all constitutions in force

- Amendments Project

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas Constitutionalism

- Constitutional Law, «Constitutions, bibliography, links»

- International Constitutional Law: English translations of various national constitutions

- United Nations Rule of Law: Constitution-making, on the relationship between constitution-making, the rule of law and the United Nations.

Works related to Portal:Constitution at Wikisource

- constitution | Theories, Features, Practices, & Facts | Britannica

- Constitutionalism | Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Constitutions and Constitutionalism | Encyclopedia.com

1

a

: the basic principles and laws of a nation, state, or social group that determine the powers and duties of the government and guarantee certain rights to the people in it

b

: a written instrument embodying the rules of a political or social organization

2

a

: the physical makeup of the individual especially with respect to the health, strength, and appearance of the body

b

: the structure, composition, physical makeup, or nature of something

the constitution of society

3

: the mode in which a state or society is organized

especially

: the manner in which sovereign power is distributed

5

: the act of establishing, making, or setting up

before the constitution of civil laws

constitutionless

adjective

Did you know?

Constitution was constituted in 14th-century English as a word indicating an established law or custom. It is from Latin constitutus, the past participle of constituere, meaning «to set up,» which is based on an agreement of the prefix com- («with, together, jointly») with the verb statuere («to set or place»). Statuere is the root of statute, which, like constitution, has a legal background; it refers to a set law, rule, or regulation. Constitution is also the name for a system of laws and principles by which a country, state, or organization is governed or the document written as a record of them. Outside of law, the word is used in reference to the physical health or condition of the body («a person of hearty constitution») or to the form or structure of something («the molecular constitution of the chemical»).

Synonyms

Example Sentences

The state’s constitution has strict rules about what tax money can be used for.

Members of the club have drafted a new constitution.

The state’s original constitution is on display at the museum.

He has a robust constitution.

Only animals with strong constitutions are able to survive the island’s harsh winters.

What is the molecular constitution of the chemical?

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

But, increasingly, there have been other calls: to unseat Netanyahu, draft a constitution (which Israel lacks), and respect nonreligious Israelis by, among other things, legalizing civic marriages and permitting public transportation on the Sabbath.

—

This new constitution gave non-Hawaiians more control over the island and left Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor as an American naval base.

—

The most far-reaching of these has been the National Security Law injected into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, known as the Basic Law, in mid 2020.

—

As its 75th anniversary approaches next month, Israel has finally achieved sufficient security and stature to consider addressing, in a formal constitution, its enduring national identity crisis: the reconciliation of its defining attributes as both a Jewish state and a multicultural democracy.

—

As a public service broadcaster, the BBC has a constitution—called a Royal Charter—designed to keep it non-partisan when reporting on the government and its opposition.

—