Every teacher wonders how to teach a word to students, so that it stays with them and they can actually use it in the context in an appropriate form. Have your students ever struggled with knowing what part of the speech the word is (knowing nothing about terminologies and word relations) and thus using it in the wrong way? What if we start to teach learners of foriegn languages the basic relations between words instead of torturing them to memorize just the usage of the word in specific contexts?

Let’s firstly try to recall what semantic relations between words are. Semantic relations are the associations that exist between the meanings of words (semantic relationships at word level), between the meanings of phrases, or between the meanings of sentences (semantic relationships at phrase or sentence level). Let’s look at each of them separately.

Word Level

At word level we differentiate between semantic relations:

- Synonyms — words that have the same (or nearly the same) meaning and belong to the same part of speech, but are spelled differently. E.g. big-large, small-tiny, to begin — to start, etc. Of course, here we need to mention that no 2 words can have the exact same meaning. There are differences in shades of meaning, exaggerated, diminutive nature, etc.

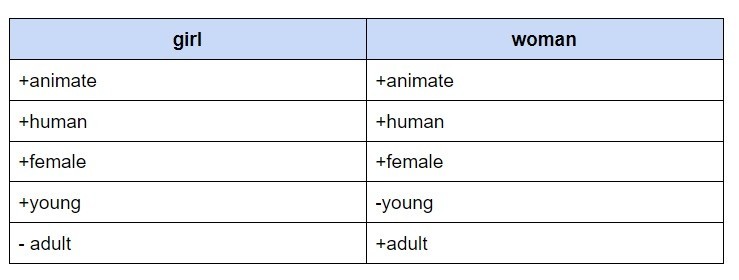

- Antonyms — semantic relationship that exists between two (or more) words that have opposite meanings. These words belong to the same grammatical category (both are nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). They share almost all their semantic features except one. (Fromkin & Rodman, 1998) E.g.

- Homonyms — the relationship that exists between two (or more) words which belong to the same grammatical category, have the same spelling, may or may not have the same pronunciation, but have different meanings and origins. E.g. to lie (= to rest) and to lie (= not to tell the truth); When used in a context, they can be misunderstood especially if the person knows only one meaning of the word.

Other semantic relations include hyponymy, polysemy and metonymy which you might want to look into when teaching/learning English as a foreign language.

At Phrase and Sentence Level

Here we are talking about paraphrases, collocations, ambiguity, etc.

- Paraphrase — the expression of the meaning of a word, phrase or sentence using other words, phrases or sentences which have (almost) the same meaning. Here we need to differentiate between lexical and structural paraphrase. E.g.

Lexical — I am tired = I am exhausted.

Structural — He gave the book to me = He gave me the book.

- Ambiguity — functionality of having two or more distinct meanings or interpretations. You can read more about its types here.

- Collocations — combinations of two or more words that often occur together in speech and writing. Among the possible combinations are verbs + nouns, adjectives + nouns, adverbs + adjectives, etc. Idiomatic phrases can also sometimes be considered as collocations. E.g. ‘bear with me’, ‘round and about’, ‘salt and pepper’, etc.

So, what does it mean to know a word?

Knowing a word means knowing all of its semantic relations and usages.

Why is it useful?

It helps to understand the flow of the language, its possibilities, occurrences, etc.better.

Should it be taught to EFL learners?

Maybe not in that many details and terminology, but definitely yes if you want your learners to study the language in depth, not just superficially.

How should it be taught?

Not as a separate phenomenon, but together with introducing a new word/phrase, so that students have a chance to create associations and base their understanding on real examples. You can give semantic relations and usages, ask students to look up in the dictionary, brainstorm ideas in pairs and so on.

Let us know what you do to help your students learn the semantic relations between the words and whether it helps.

In many types of translation any attempt by the translator to modify his text for some extratranslational purpose will be considered unprofessional conduct and severely condemned. But there are also some other types of translation where particular aspects of equivalence are of little interest and often disregarded.

When a book is translated with a view to subsequent publication in another country, it may be adapted or abridged to meet the country’s stan-

46

dards for printed matter. The translator may omit parts of the book or some descriptions considered too obscene or naturalistic for publication in his country, though permissible in the original.

In technical or other informative translations the translator or his employers may be interested in getting the gist of the contents or the most important or novel part of it, which may involve leaving out certain details or a combination of translation with brief accounts of less important parts of the original. A most common feature of such translations is neglect of the stylistic and structural peculiarities of the original. In this case translation often borders on retelling or precis writing.

A specific instance is consecutive interpretation where the interpreter is often set a time limit within which he is expected to report his translation no matter how long the original speech may have been. This implies selection, generalizations, and cutting through repetitions, incidental digressions, occasional slips or excessive embellishments.

It is obvious that in all similar cases the differences which can be revealed between the original text and its translation should not be ascribed to the translator’s inefficiency or detract from the quality of his work. The pragmatic value of such translations clearly compensates for their lack of equivalence. Evidently there are different types of translation serving different purposes.

Suggested Topics for Discussion

1.What is pragmatics? What is the difference between semantics, syntactics and pragmatics? What relationships can exist between the word and its users?

2.What role do the pragmatic aspects play in translation? Can correlated words in SL and TL have dissimilar effect upon the users? How should the pragmatic meaning of the word be rendered in translation?

3.What does the communicative effect of a speech unit depend upon? What factors influence the understanding of TT? What is background information?

4.What are the relationships between pragmatics and equivalence? Can semantically equivalent speech units in ST and TT produce different effects upon their readers?

5.How is the translation event oriented pragmatically? Is its only purpose to produce the closest approximation to ST? What additional pragmatic factors may have their impact on the specific translation event?

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

6.How is the translating process oriented toward a concrete TR? What does «dynamic equivalence» mean? What is the pragmatic value of translation?

7.What additional goals may the translator pursue in the translating

47

process? In what way can such a «super-purpose» influence the process? Can the translator play some «extra-translational» roles in his work?

8. What is the pragmatic adaptation of TT? What are the main factors necessitating such adaptation? What changes may be introduced in the translating process due to the pragmatic requirements?

Text

THE PATH OF PROGRESS

(1) The process of change was set in motion everywhere from Land’s End to John O’Groats. (2) But it was in northern cities that our modern world was born. (3) These stocky, taciturn people were the first to live by steam, cogs, iron, and engine grease, and the first in modem times to demonstrate the dynamism of the human condition. (4) This is where, by all the rules of heredity, the artificial satellite and the computer were conceived. (5) Baedeker may not recognize it, but it is one of history’s crucibles. (6) Until the start of the technical revolution, in the second half of the eighteenth century, England was an agricultural country, only slightly invigorated by the primitive industries of the day. (7) She was impelled, for the most part, by muscular energies — the strong arms of her islanders, the immense legs of her noble horses. (8) But she was already mining coal and smelting iron, digging canals and negotiating bills of exchange. (9) Agriculture itself had changed under the impact of new ideas: the boundless open fields of England had almost all been enclosed, and lively farmers were experimenting with crop rotation, breeding methods and winter feed. (10) There was a substantial merchant class already, fostered by trade and adventure, and a solid stratum of literate yeomen.

Text Analysis

(1)What geographical points are called Land’s End and John O’Groats? What area is meant in the phrase ‘from Land’s End to John O’Groats»? Does «to set a process in motion» mean «to begin it»?

(2)How would you understand the phrase «our modern world was born in northern cities of Britain»? What is meant by the «modern world»? Does the phrase imply the political, economic or technical aspects of our civilization?

(3)Do the word «stocky» and «taciturn» give a positive or a negative characteristics of the people? How can people «live by steam»? Does the «dynamism of the human condition» mean that the living conditions of people can change quickly or that they do not change at all?

(4)What does the phrase «by the rules of heredity mean? Were the artificial satellite and the computer really invented, built or first thought of in the North of Britain?

48

(5)Who or what is Baedeker? What is a history’s crucible? Is it a place where «history is made»? In what way does Baedeker not recognize the fact that history was made in the North of Britain? What places are referred to as historical in guidebooks?

(6)Why are the primitive industries said to «invigorate the country»?

(7)How can the country be impelled? Why are the people of England referred to as «islanders»? What kind of horses may be called «noble»? Why should their legs be «immense»?

(8)What is a bill of exchange? How can it be «negotiated»?

(9)Why should the open fields be enclosed? What were the enclosed fields used for? Does the word «lively» refer to the physical or to the mental qualities of the farmers? What is winter feed?

(10)How can a class be fostered? What kind of adventure is mentioned here? Has it anything to do with overseas voyages and geographical discoveries? What is the difference between a serf and a yeoman?

Problem-Solving Exercises

A. Pragmatic Aspects of Translation

I. Will the geographical names if preserved in the translation of sentence

(1) convey the implied sense to the Russian reader or should it be made more explicit in TT?

II. Describe the emotional effect of the Russian adjectives ,

, . Which of them will be a good pragmatic equivalent to the word «stocky» in sentence (3)?

III. Will the word-for-word translation of sentence (4) be correctly understood by the Russian reader: , ,

? Give a better wording which will make clear that the English sentence does not imply that satellites and computers were actually designed in the 18th century.

IV. Translate the word «Baedeker» in sentence (5) in such a way as to make its meaning clear to the Russian reader.

V. What Russian figure of speech will be a pragmatic substitute for the

English «history’s crucible» in sentence (5)?

VI. What associations has the Russian word ? Can you use it as a substitute for the English «islanders» in sentence (7)?

VII. Which of the following Russian substitutes is pragmatically closer to the meaning of the English adjective «immense» in sentence (7): , , ?

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

VIII. Give different translations of the phrase «negotiating bills of exchange» in sentence (8) meant for the expert and for the layman.

49

IX. The term «enclosed» in sentence (9) implies some well-known economic processes in Britain’s history. What Russian term has the same implication?

X. The word «adventure» in sentence (10) has historical associations absent

in its usual Russian equivalents: , , . Suggest a translation which will have similar associations.

B. Other Translation Problems

XI. Is it good Russian to say ? If not, what will your suggest to render the meaning of sentence (1)?

XII. Compare the following Russian phrases as possible substitutes for the English «was born» in sentence (2): , , , .

XIII. Enumerate the most common ways of rendering into Russian the meaning of the English emphatic structure «it is … that». (Cf. sentence

(2)0

XIV. Which of the following Russian substitutes, if any, would you prefer for the English «to live by» in sentence (3): , ,

?

XV. Compare the following Russian substitutes for the word «cogs» in sentence (3): ,

, . Make your choice and give your reasons.

XVI. Compare the following Russian phrases as possible substitutes for «by all the rules of heredity» in sentence (4): , ,

.

XVII. Would you use the regular Russian equivalent to the English word «recognize» in sentence (5), that is, or will you prefer , or something else?

XVIII. Your dictionary suggests two possible translations of the word «crucible»:

and . Can either of them be used in translating sentence (5). If not, why?

XIX. Would you use a blue-print translation of «the technical revolution» in sentence (6) or opt for a more common term ?

XX. Choose a good substitute for the phrase «of the day» in sentence (6) among the following:

, , .

XXL Does «industries» in sentence (6) mean or ?

XXII. It is obvious that the phrase ( ) -50

is no good. (Cf. «She was impelled» in sentence (7).) Suggest another Russian wording as a good substitute.

XXIII. Can the Russian word ever be used in the plural? Would you use it in the plural in the translation of sentence (7)?

XXIV. What would you suggest as a good substitute for the pronoun «she» in sentence (8): ,

, , ?

XXV. Would you use the regular equivalents to the English «digging» in sentence (8), that is, the Russian verbs , or would you opt for , and the like?

XXVI. Try to list some Russian words which denote various operations with bills of exchange such as , ( ).

XXVII. Have you heard the phrase ? What historical facts does it refer to?

XXVIII. Is the English word «feed» in sentence (9) closer in its meaning to the Russian or

?

XXIX. What would you prefer as a substitute for the term «merchant class» in sentence (10):

, or something else?

XXX. Make your choice between the Russian words and as substitutes for the English ‘literate» in sentence (10).

CHAPTER 6. MAIN TYPES OF TRANSLATION* Basic Assumptions

Though the basic characteristics of translation can be observed in all translation events, different types of translation can be singled out depending on the predominant communicative function of the source text or the form of speech involved in the translation process. Thus we can distinguish between literary and informative translation, on the one hand, and between written and oral translation (or interpretation), on the other hand.

Literary translation deals with literary texts, i.e. works of fiction or poetry whose main function is to make an emotional or aesthetic impression upon the reader. Their communicative value depends, first and foremost, on their artistic quality and the translator’s primary task is to reproduce this quality in translation.

Informative translation is rendering into the target language non-literary texts, the main purpose of which is to convey a certain amount of ideas, to inform the reader. However, if the source text is of some length, its translation can be listed as literary or informative only as an approximation. A literary text may, in fact, include some parts of purely informative

* See «Theory of Translation», Chs. IV, V.

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

51

character. Contrariwise, informative translation may comprise some elements aimed at achieving an aesthetic effect. Within each group further gradations can be made to bring out more specific problems in literary or informative translation.

Literary works are known to fall into a number of genres. Literary translations may be subdivided in the same way, as each genre calls for a specific arrangement and makes use of specific artistic means to impress the reader. Translators of prose, poetry or plays have their own problems. Each of these forms of literary activities comprises a number of subgenres and the translator may specialize in one or some of them in accordance with his talents and experience. The particular tasks inherent in the translation of literary works of each genre are more literary than linguistic. The great challenge to the translator is to combine the maximum equivalence and the high literary merit.

The translator of a belles-lettres text is expected to make a careful study of the literary trend the text belongs to, the other works of the same author, the peculiarities of his individual style and manner and sn on. This involves both linguistic considerations and skill in literary criticism. A good literary translator must be a versatile scholar and a talented writer or poet.

A number of subdivisions can be also suggested for informative translations, though the principles of classification here are somewhat different. Here we may single out translations of scientific and technical texts, of newspaper materials, of official papers and some other types of texts such as public speeches, political and propaganda materials, advertisements, etc., which are, so to speak, intermediate, in that there is a certain balance between the expressive and referential functions, between reasoning and emotional appeal.

Translation of scientific and technical materials has a most important role to play in our age of the revolutionary technical progress. There is hardly a translator or an interpreter today who has not to deal with technical matters. Even the «purely» literary translator often comes across highly technical stuff in works of fiction or even in poetry. An in-depth theoretical study of the specific features of technical translation is an urgent task of translation linguistics while training of technical translators is a major practical problem.

In technical translation the main goal is to identify the situation described in the original. The predominance of the referential function is a great challenge to the translator who must have a good command of the technical terms and a sufficient understanding of the subject matter to be able to give an adequate description of the situation even if this is not fully achieved in the original. The technical translator is also expected to observe

52

the stylistic requirements of scientific and technical materials to make text acceptable to the specialist.

Some types of texts can be identified not so much by their positive distinctive features as by the difference in their functional characteristics in the two languages. English newspaper reports

differ greatly from their Russian counterparts due to the frequent use of colloquial, slang and vulgar elements, various paraphrases, eye-catching headlines, etc.

When the translator finds in a newspaper text the headline «Minister bares his teeth on fluoridation» which just means that this minister has taken a resolute stand on the matter, he will think twice before referring to the minister’s teeth in the Russian translation. He would rather use a less expressive way of putting it to avoid infringement upon the accepted norms of the Russian newspaper style.

Apart from technical and newspaper materials it may be expedient to single out translation of official diplomatic papers as a separate type of informative translation. These texts make a category of their own because of the specific requirements to the quality of their translations. Such translations are often accepted as authentic official texts on a par with the originals. They are important documents every word of which must be carefully chosen as a matter of principle. That makes the translator very particular about every little meaningful element of the original which he scrupulously reproduces in his translation. This scrupulous imitation of the original results sometimes in the translator more readily erring in literality than risking to leave out even an insignificant element of the original contents.

Journalistic (or publicistic) texts dealing with social or political matters are sometimes singled out among other informative materials because they may feature elements more commonly used in literary text (metaphors, similes and other stylistic devices) which cannot but influence the translator’s strategy. More often, however, they are regarded as a kind of newspaper materials (periodicals).

There are also some minor groups of texts that can be considered separately because of the specific problems their translation poses to the translator. They are film scripts, comic strips, commercial advertisements and the like. In dubbing a film the translator is limited in his choice of variants by the necessity to fit the pronunciation of the translated words to the movement of the actor’s lips. Translating the captions in a comic strip, the translator will have to consider the numerous allusions to the facts well-known to the regular readers of comics but less familiar to the Russian readers. And in dealing with commercial advertisements he must bear in mind that their sole purpose is to win over the prospective customers. Since the text of translation will deal with quite a different kind of people than the

53

original advertisement was meant for, there is the problem of achieving the same pragmatic effect by introducing the necessary changes in the message. This confronts the translator with the task of the pragmatic adaptation in translation, which was subjected to a detailed analysis in Ch. 5.

Though the present manual is concerned with the problems of written translation from English into Russian, some remarks should be made about the obvious classification of translations as written or oral. As the names suggest, in written translation the source text is in written form, as is the target text. In oral translation or interpretation the interpreter listens to the oral presentation of the original and translates it as an oral message in TL. As a result, in the first case the Receptor of the translation can read it while in the second case he hears it.

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

There are also some intermediate types. The interpreter rendering his translation by word of mouth may have the text of the original in front of him and translate it «at sight». A written translation can be made of the original recorded on the magnetic tape that can be replayed as many times as is necessary for the translator to grasp the original meaning. The translator can dictate his «at sight» translation of a written text to the typist or a short-hand writer with TR getting the translation in written form.

These are all, however, modifications of the two main types of translation. The line of demarcation between written and oral translation is drawn not only because of their forms but also because of the sets of conditions in which the process takes place. The first is continuous, the other momentary. In written translation the original can be read and re-read as many times as the translator may need or like. The same goes for the final product. The translator can re-read his translation, compare it to the original, make the necessary corrections or start his work all over again. He can come back to the preceding part of the original or get the information he needs from the subsequent messages. These are most favourable conditions and here we can expect the best performance and the highest level of equivalence. That is why in theoretical discussions we have usually examples from written translations where the translating process can be observed in all its aspects.

The conditions of oral translation impose a number of important restrictions on the translator’s performance. Here the interpreter receives a fragment of the original only once and for a short period of time. His translation is also a one-time act with no possibility of any return to the original or any subsequent corrections. This creates additional problems and the users have sometimes; to be content with a lower level of equivalence.

There are two main kinds of oral translation — consecutive and simultaneous. In consecutive translation the translating starts after the original

54

speech or some part of it has been completed. Here the interpreter’s strategy and the final results depend, to a great extent, on the length of the segment to be translated. If the segment is just a sentence or two the interpreter closely follows the original speech. As often as not, however, the interpreter is expected to translate a long speech which has lasted for scores of minutes or even longer. In this case he has to remember a great number of messages and keep them in mind until he begins his translation. To make this possible the interpreter has to take notes of the original messages, various systems of notation having been suggested for the purpose. The study of, and practice in, such notation is the integral part of the interpreter’s training as are special exercises to develop his memory.

Sometimes the interpreter is set a time limit to give his rendering, which means that he will have to reduce his translation considerably, selecting and reproducing the most important parts of the original and dispensing with the rest. This implies the ability to make a judgement on the relative value of various messages and to generalize or compress the received information. The interpreter must obviously be a good and quickwitted thinker.

In simultaneous interpretation the interpreter is supposed to be able to give his translation while the speaker is uttering the original message. This can be achieved with a special radio or telephone-type equipment. The interpreter receives the original speech through his earphones and simultaneously talks into the microphone which transmits his translation to the listeners.

This type of translation involves a number of psycholinguistic problems, both of theoretical and practical nature.

Suggested Topics for Discussion

1.What are the two principles of translation classification? What are the main types of translation? What is the difference between literary and informative translations?

2.How can literary translations be sudivided? What is the main difficulty of translating a work of high literary merit? What qualities and skills are expected of a literary translator?

3.How can informative translations be subdivided? Are there any intermediate types of translation? What type of informative translations plays an especially important role in the modern world?

4.What is the main goal of a technical translation? What specific requirements is the technical translator expected to meet? What problems is the theory of technical translation concerned with?

5.What are the main characteristics of translations dealing with newspaper, diplomatic and other official materials? What specific problems emerge in translating film scripts and commercial advertisements?

55

6.What is the main difference between translation and interpretation? Which of them is usually made at a higher level of accuracy? Are there any intermediate forms of translation?

7.How can interpretation be classified? What are the characteristic features of consecutive interpretation? What is the role of notation in consecutive interpretation?

Text

I

(SCIENTIFIC)

(1) Water has the extraordinary ability to dissolve a greater variety of substances than any other liquid. (2) Falling through the air it collects atmospheric gases, salts, nitrogen, oxygen and other compounds, nutrients and pollutants alike. (3) The carbon dioxide it gathers reacts with the water to form carbonic acid. (4) This, in turn, gives it greater power to break down rocks and soil particles that are subsequently put into solution as nutrients and utilized by growing plants and trees. (5) Without this dissolving ability, our lakes and streams would be biological deserts, for pure water cannot sustain aquatic life. (6) Water dissolves, cleanses, serves plants and animals as a carrier of food and minerals; it is the only substance that occurs in all three states — solid, liquid and gas — and yet always retains its own identity and emerges again as water.

II

(NEWSPAPER)

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

(7)1 am often asked what I think of the latest opinion poll, especially when it has published what appears to be some dramatic swing in «public opinion». (8) It is as if the public seeing itself reflected in a mirror, seeks reassurance that the warts on the face of its opinion are not quite ugly as all that! (9) I react to these inquiries from the ludicrous posture of a man who, being both a politician and a statistician cannot avoid wearing two hats. (10) I am increasingly aware of the intangibility of the phenomenon described as «public opinion». (11) It is the malevolent ghost in the haunted house of politics. (12) But the definition of public opinion given by the majority of opinion polls is about the last source from which those responsible for deciding the great issues of the day should seek guidance.

Text Analysis

I

1. What type of text is it? What makes you think that it is informative? 56

What type of words are predominant in the text? What branch of science do most of the terms belong to?

2.What is the difference between substance and matter? Why should water fall through the air? How can water «collect» various substances?

3.What elements make up carbonic dioxide? What is carbonic acid? What are carbonates? What other acids or salts do you know? What is solution? How does water provide food for plants and trees?

4.What is the difference between a stream and a river? What do plants need for their growth? When can a lake be called a biological desert? What is pure water? What is aquatic life? Why can pure water not sustain aquatic life?

5.Why can water be called a carrier of food? What do we call water in solid state? What is the general term for liquids and gases? How can water retain its identity? Does it mean that it always has the same properties or the same composition?

II

6.What type of text is this? Are there any literary devices in it? Is its subject literary or informative? Is it narrated in the first or in the third person? Is its author a man of letters or a scientist?

7.What is an opinion poll? What are people usually polled about? Are the results of an opinion poll published in newspapers? What is a swing hi public opinion? Why are the words «public opinion» written in inverted commas? What swing in public opinion may be described as dramatic?

8.In what mirror does the public see itself? What is a wart? What warts are referred to in the text? Why should the public seek any reassurance?

1. What is pragmatics? What is the difference between semantics, syntactics and pragmatics? What relationships can exist between the word and its users?

2. What role do the pragmatic aspects play in translation? Can correlated words in SL and TL have dissimilar effect upon the users? How should the pragmatic meaning of the word be rendered in translation?

3. What does the communicative effect of a speech unit depend upon? What factors influence the understanding of TT? What is background information?

4. What are the relationships between pragmatics and equivalence? Can semantically equivalent speech units in ST and TT produce different effects upon their readers?

5. How is the translation event oriented pragmatically? Is its only purpose to produce the closest approximation to ST? What additional pragmatic factors may have their impact on the specific translation event?

6. How is the translating process oriented toward a concrete TR? What does «dynamic equivalence» mean? What is the pragmatic value of translation?

7. What additional goals may the translator pursue in the translating

47

process? In what way can such a «super-purpose» influence the process? Can the translator play some «extra-translational» roles in his work?

8. What is the pragmatic adaptation of TT? What are the main factors necessitating such adaptation? What changes may be introduced in the translating process due to the pragmatic requirements?

Text

THE PATH OF PROGRESS

(1) The process of change was set in motion everywhere from Land’s End to John O’Groats. (2) But it was in northern cities that our modern world was born. (3) These stocky, taciturn people were the first to live by steam, cogs, iron, and engine grease, and the first in modem times to demonstrate the dynamism of the human condition. (4) This is where, by all the rules of heredity, the artificial satellite and the computer were conceived. (5) Baedeker may not recognize it, but it is one of history’s crucibles. (6) Until the start of the technical revolution, in the second half of the eighteenth century, England was an agricultural country, only slightly invigorated by the primitive industries of the day. (7) She was impelled, for the most part, by muscular energies — the strong arms of her islanders, the immense legs of her noble horses. (8) But she was already mining coal and smelting iron, digging canals and negotiating bills of exchange. (9) Agriculture itself had changed under the impact of new ideas: the boundless open fields of England had almost all been enclosed, and lively farmers were experimenting with crop rotation, breeding methods and winter feed. (10) There was a substantial merchant class already, fostered by trade and adventure, and a solid stratum of literate yeomen.

Text Analysis

(1) What geographical points are called Land’s End and John O’Groats? What area is meant in the phrase ‘from Land’s End to John O’Groats»? Does «to set a process in motion» mean «to begin it»?

(2) How would you understand the phrase «our modern world was born in northern cities of Britain»? What is meant by the «modern world»? Does the phrase imply the political, economic or technical aspects of our civilization?

(3) Do the word «stocky» and «taciturn» give a positive or a negative characteristics of the people? How can people «live by steam»? Does the «dynamism of the human condition» mean that the living conditions of people can change quickly or that they do not change at all?

(4) What does the phrase «by the rules of heredity mean? Were the artificial satellite and the computer really invented, built or first thought of in the North of Britain?

48

(5) Who or what is Baedeker? What is a history’s crucible? Is it a place where «history is made»? In what way does Baedeker not recognize the fact that history was made in the North of Britain? What places are referred to as historical in guidebooks?

(6) Why are the primitive industries said to «invigorate the country»?

(7) How can the country be impelled? Why are the people of England referred to as «islanders»? What kind of horses may be called «noble»? Why should their legs be «immense»?

(8) What is a bill of exchange? How can it be «negotiated»?

(9) Why should the open fields be enclosed? What were the enclosed fields used for? Does the word «lively» refer to the physical or to the mental qualities of the farmers? What is winter feed?

(10) How can a class be fostered? What kind of adventure is mentioned here? Has it anything to do with overseas voyages and geographical discoveries? What is the difference between a serf and a yeoman?

Problem-Solving Exercises

A. Pragmatic Aspects of Translation

I. Will the geographical names if preserved in the translation of sentence

(1) convey the implied sense to the Russian reader or should it be made more explicit in TT?

II. Describe the emotional effect of the Russian adjectives низкорослый,

приземистый, коренастый. Which of them will be a good pragmatic equivalent to the word «stocky» in sentence (3)?

III. Will the word-for-word translation of sentence (4) be correctly understood by the Russian reader: Именно здесь, по всем законам наследственности, были задуманы искусственные спутники и компьютеры? Give a better wording which will make clear that the English sentence does not imply that satellites and computers were actually designed in the 18th century.

IV. Translate the word «Baedeker» in sentence (5) in such a way as to make its meaning clear to the Russian reader.

V. What Russian figure of speech will be a pragmatic substitute for the

English «history’s crucible» in sentence (5)?

VI. What associations has the Russian word островитянин? Can you use it as a substitute for the English «islanders» in sentence (7)?

VII. Which of the following Russian substitutes is pragmatically closer to the meaning of the English adjective «immense» in sentence (7): огромный, толстый, могучий?

VIII. Give different translations of the phrase «negotiating bills of exchange» in sentence (8) meant for the expert and for the layman.

49

IX. The term «enclosed» in sentence (9) implies some well-known economic processes in Britain’s history. What Russian term has the same implication?

X. The word «adventure» in sentence (10) has historical associations absent

in its usual Russian equivalents: приключение, авантюра, рискованное предприятие. Suggest a translation which will have similar associations.

B. Other Translation Problems

XI. Is it good Russian to say процесс изменений был приведен в движение? If not, what will your suggest to render the meaning of sentence (1)?

XII. Compare the following Russian phrases as possible substitutes for the English «was born» in sentence (2): был рожден, возник, было положено начало, зародился.

XIII. Enumerate the most common ways of rendering into Russian the meaning of the English emphatic structure «it is … that». (Cf. sentence

(2)0

XIV. Which of the following Russian substitutes, if any, would you prefer for the English «to live by» in sentence (3): стали широко использовать, стали жить при помощи, в чьей жизни главную роль стали играть?

XV. Compare the following Russian substitutes for the word «cogs» in sentence (3): шестерни, зубчатые колеса, зубчатые передачи. Make your choice and give your reasons.

XVI. Compare the following Russian phrases as possible substitutes for «by all the rules of heredity» in sentence (4): сюда уходят корнями, отсюда берут свое начало, отсюда ведут свою родословную.

XVII. Would you use the regular Russian equivalent to the English word «recognize» in sentence (5), that is, признавать or will you prefer упоминать, умалчивать or something else?

XVIII. Your dictionary suggests two possible translations of the word «crucible»: плавильный тигель and суровое испытание. Can either of them be used in translating sentence (5). If not, why?

XIX. Would you use a blue-print translation of «the technical revolution» in sentence (6) or opt for a more common term промышленная революция?

XX. Choose a good substitute for the phrase «of the day» in sentence (6) among the following: того дня, того времени, современный.

XXL Does «industries» in sentence (6) mean промышленность or отрасли промышленности?

XXII. It is obvious that the phrase Она (страна) приводилась в движе-50

ние is no good. (Cf. «She was impelled» in sentence (7).) Suggest another Russian wording as a good substitute.

XXIII. Can the Russian word энергия ever be used in the plural? Would you use it in the plural in the translation of sentence (7)?

XXIV. What would you suggest as a good substitute for the pronoun «she» in sentence (8): она, Англия, англичане, в Англии?

XXV. Would you use the regular equivalents to the English «digging» in sentence (8), that is, the Russian verbs копать, рыть or would you opt for прокладывать, строить and the like?

XXVI. Try to list some Russian words which denote various operations with bills of exchange such as выдать, учесть (вексель).

XXVII. Have you heard the phrase овцы съели людей? What historical facts does it refer to?

XXVIII. Is the English word «feed» in sentence (9) closer in its meaning to the Russian корм or откорм ?

XXIX. What would you prefer as a substitute for the term «merchant class» in sentence (10): класс купцов, класс торговцев or something else?

XXX. Make your choice between the Russian words грамотный and образованный as substitutes for the English ‘literate» in sentence (10).

CHAPTER 6. MAIN TYPES OF TRANSLATION* Basic Assumptions

Though the basic characteristics of translation can be observed in all translation events, different types of translation can be singled out depending on the predominant communicative function of the source text or the form of speech involved in the translation process. Thus we can distinguish between literary and informative translation, on the one hand, and between written and oral translation (or interpretation), on the other hand.

Literary translation deals with literary texts, i.e. works of fiction or poetry whose main function is to make an emotional or aesthetic impression upon the reader. Their communicative value depends, first and foremost, on their artistic quality and the translator’s primary task is to reproduce this quality in translation.

Informative translation is rendering into the target language non-literary texts, the main purpose of which is to convey a certain amount of ideas, to inform the reader. However, if the source text is of some length, its translation can be listed as literary or informative only as an approximation. A literary text may, in fact, include some parts of purely informative

* See «Theory of Translation», Chs. IV, V.

51

character. Contrariwise, informative translation may comprise some elements aimed at achieving an aesthetic effect. Within each group further gradations can be made to bring out more specific problems in literary or informative translation.

Literary works are known to fall into a number of genres. Literary translations may be subdivided in the same way, as each genre calls for a specific arrangement and makes use of specific artistic means to impress the reader. Translators of prose, poetry or plays have their own problems. Each of these forms of literary activities comprises a number of subgenres and the translator may specialize in one or some of them in accordance with his talents and experience. The particular tasks inherent in the translation of literary works of each genre are more literary than linguistic. The great challenge to the translator is to combine the maximum equivalence and the high literary merit.

The translator of a belles-lettres text is expected to make a careful study of the literary trend the text belongs to, the other works of the same author, the peculiarities of his individual style and manner and sn on. This involves both linguistic considerations and skill in literary criticism. A good literary translator must be a versatile scholar and a talented writer or poet.

A number of subdivisions can be also suggested for informative translations, though the principles of classification here are somewhat different. Here we may single out translations of scientific and technical texts, of newspaper materials, of official papers and some other types of texts such as public speeches, political and propaganda materials, advertisements, etc., which are, so to speak, intermediate, in that there is a certain balance between the expressive and referential functions, between reasoning and emotional appeal.

Translation of scientific and technical materials has a most important role to play in our age of the revolutionary technical progress. There is hardly a translator or an interpreter today who has not to deal with technical matters. Even the «purely» literary translator often comes across highly technical stuff in works of fiction or even in poetry. An in-depth theoretical study of the specific features of technical translation is an urgent task of translation linguistics while training of technical translators is a major practical problem.

In technical translation the main goal is to identify the situation described in the original. The predominance of the referential function is a great challenge to the translator who must have a good command of the technical terms and a sufficient understanding of the subject matter to be able to give an adequate description of the situation even if this is not fully achieved in the original. The technical translator is also expected to observe

52

the stylistic requirements of scientific and technical materials to make text acceptable to the specialist.

Some types of texts can be identified not so much by their positive distinctive features as by the difference in their functional characteristics in the two languages. English newspaper reports differ greatly from their Russian counterparts due to the frequent use of colloquial, slang and vulgar elements, various paraphrases, eye-catching headlines, etc.

When the translator finds in a newspaper text the headline «Minister bares his teeth on fluoridation» which just means that this minister has taken a resolute stand on the matter, he will think twice before referring to the minister’s teeth in the Russian translation. He would rather use a less expressive way of putting it to avoid infringement upon the accepted norms of the Russian newspaper style.

Apart from technical and newspaper materials it may be expedient to single out translation of official diplomatic papers as a separate type of informative translation. These texts make a category of their own because of the specific requirements to the quality of their translations. Such translations are often accepted as authentic official texts on a par with the originals. They are important documents every word of which must be carefully chosen as a matter of principle. That makes the translator very particular about every little meaningful element of the original which he scrupulously reproduces in his translation. This scrupulous imitation of the original results sometimes in the translator more readily erring in literality than risking to leave out even an insignificant element of the original contents.

Journalistic (or publicistic) texts dealing with social or political matters are sometimes singled out among other informative materials because they may feature elements more commonly used in literary text (metaphors, similes and other stylistic devices) which cannot but influence the translator’s strategy. More often, however, they are regarded as a kind of newspaper materials (periodicals).

There are also some minor groups of texts that can be considered separately because of the specific problems their translation poses to the translator. They are film scripts, comic strips, commercial advertisements and the like. In dubbing a film the translator is limited in his choice of variants by the necessity to fit the pronunciation of the translated words to the movement of the actor’s lips. Translating the captions in a comic strip, the translator will have to consider the numerous allusions to the facts well-known to the regular readers of comics but less familiar to the Russian readers. And in dealing with commercial advertisements he must bear in mind that their sole purpose is to win over the prospective customers. Since the text of translation will deal with quite a different kind of people than the

53

original advertisement was meant for, there is the problem of achieving the same pragmatic effect by introducing the necessary changes in the message. This confronts the translator with the task of the pragmatic adaptation in translation, which was subjected to a detailed analysis in Ch. 5.

Though the present manual is concerned with the problems of written translation from English into Russian, some remarks should be made about the obvious classification of translations as written or oral. As the names suggest, in written translation the source text is in written form, as is the target text. In oral translation or interpretation the interpreter listens to the oral presentation of the original and translates it as an oral message in TL. As a result, in the first case the Receptor of the translation can read it while in the second case he hears it.

There are also some intermediate types. The interpreter rendering his translation by word of mouth may have the text of the original in front of him and translate it «at sight». A written translation can be made of the original recorded on the magnetic tape that can be replayed as many times as is necessary for the translator to grasp the original meaning. The translator can dictate his «at sight» translation of a written text to the typist or a short-hand writer with TR getting the translation in written form.

These are all, however, modifications of the two main types of translation. The line of demarcation between written and oral translation is drawn not only because of their forms but also because of the sets of conditions in which the process takes place. The first is continuous, the other momentary. In written translation the original can be read and re-read as many times as the translator may need or like. The same goes for the final product. The translator can re-read his translation, compare it to the original, make the necessary corrections or start his work all over again. He can come back to the preceding part of the original or get the information he needs from the subsequent messages. These are most favourable conditions and here we can expect the best performance and the highest level of equivalence. That is why in theoretical discussions we have usually examples from written translations where the translating process can be observed in all its aspects.

The conditions of oral translation impose a number of important restrictions on the translator’s performance. Here the interpreter receives a fragment of the original only once and for a short period of time. His translation is also a one-time act with no possibility of any return to the original or any subsequent corrections. This creates additional problems and the users have sometimes; to be content with a lower level of equivalence.

There are two main kinds of oral translation — consecutive and simultaneous. In consecutive translation the translating starts after the original

54

speech or some part of it has been completed. Here the interpreter’s strategy and the final results depend, to a great extent, on the length of the segment to be translated. If the segment is just a sentence or two the interpreter closely follows the original speech. As often as not, however, the interpreter is expected to translate a long speech which has lasted for scores of minutes or even longer. In this case he has to remember a great number of messages and keep them in mind until he begins his translation. To make this possible the interpreter has to take notes of the original messages, various systems of notation having been suggested for the purpose. The study of, and practice in, such notation is the integral part of the interpreter’s training as are special exercises to develop his memory.

Sometimes the interpreter is set a time limit to give his rendering, which means that he will have to reduce his translation considerably, selecting and reproducing the most important parts of the original and dispensing with the rest. This implies the ability to make a judgement on the relative value of various messages and to generalize or compress the received information. The interpreter must obviously be a good and quickwitted thinker.

In simultaneous interpretation the interpreter is supposed to be able to give his translation while the speaker is uttering the original message. This can be achieved with a special radio or telephone-type equipment. The interpreter receives the original speech through his earphones and simultaneously talks into the microphone which transmits his translation to the listeners. This type of translation involves a number of psycholinguistic problems, both of theoretical and practical nature.

Suggested Topics for Discussion

1. What are the two principles of translation classification? What are the main types of translation? What is the difference between literary and informative translations?

2. How can literary translations be sudivided? What is the main difficulty of translating a work of high literary merit? What qualities and skills are expected of a literary translator?

3. How can informative translations be subdivided? Are there any intermediate types of translation? What type of informative translations plays an especially important role in the modern world?

4. What is the main goal of a technical translation? What specific requirements is the technical translator expected to meet? What problems is the theory of technical translation concerned with?

5. What are the main characteristics of translations dealing with newspaper, diplomatic and other official materials? What specific problems emerge in translating film scripts and commercial advertisements?

55

6. What is the main difference between translation and interpretation? Which of them is usually made at a higher level of accuracy? Are there any intermediate forms of translation?

7. How can interpretation be classified? What are the characteristic features of consecutive interpretation? What is the role of notation in consecutive interpretation?

Text

I

(SCIENTIFIC)

(1) Water has the extraordinary ability to dissolve a greater variety of substances than any other liquid. (2) Falling through the air it collects atmospheric gases, salts, nitrogen, oxygen and other compounds, nutrients and pollutants alike. (3) The carbon dioxide it gathers reacts with the water to form carbonic acid. (4) This, in turn, gives it greater power to break down rocks and soil particles that are subsequently put into solution as nutrients and utilized by growing plants and trees. (5) Without this dissolving ability, our lakes and streams would be biological deserts, for pure water cannot sustain aquatic life. (6) Water dissolves, cleanses, serves plants and animals as a carrier of food and minerals; it is the only substance that occurs in all three states — solid, liquid and gas — and yet always retains its own identity and emerges again as water.

II

(NEWSPAPER)

(7)1 am often asked what I think of the latest opinion poll, especially when it has published what appears to be some dramatic swing in «public opinion». (8) It is as if the public seeing itself reflected in a mirror, seeks reassurance that the warts on the face of its opinion are not quite ugly as all that! (9) I react to these inquiries from the ludicrous posture of a man who, being both a politician and a statistician cannot avoid wearing two hats. (10) I am increasingly aware of the intangibility of the phenomenon described as «public opinion». (11) It is the malevolent ghost in the haunted house of politics. (12) But the definition of public opinion given by the majority of opinion polls is about the last source from which those responsible for deciding the great issues of the day should seek guidance.

Text Analysis

I

1. What type of text is it? What makes you think that it is informative? 56

What type of words are predominant in the text? What branch of science do most of the terms belong to?

2. What is the difference between substance and matter? Why should water fall through the air? How can water «collect» various substances?

3. What elements make up carbonic dioxide? What is carbonic acid? What are carbonates? What other acids or salts do you know? What is solution? How does water provide food for plants and trees?

4. What is the difference between a stream and a river? What do plants need for their growth? When can a lake be called a biological desert? What is pure water? What is aquatic life? Why can pure water not sustain aquatic life?

5. Why can water be called a carrier of food? What do we call water in solid state? What is the general term for liquids and gases? How can water retain its identity? Does it mean that it always has the same properties or the same composition?

II

6. What type of text is this? Are there any literary devices in it? Is its subject literary or informative? Is it narrated in the first or in the third person? Is its author a man of letters or a scientist?

7. What is an opinion poll? What are people usually polled about? Are the results of an opinion poll published in newspapers? What is a swing hi public opinion? Why are the words «public opinion» written in inverted commas? What swing in public opinion may be described as dramatic?

8. In what mirror does the public see itself? What is a wart? What warts are referred to in the text? Why should the public seek any reassurance?

9. What does the author mean by saying that he has to wear two hats? In what way can a phenomenon be intangible? What is a haunted house? Is a «ghost» something real, easily defined or understood?

10. Does a «definition» mean in this context an explanation or the result? What is the meaning of the phrase «He is the last man to help you»? Does the author think the results of an opinion poll to be a reliable source of information?

Problem-Solving Exercises

A. Text Type Features

I. Identify the names of chemical elements in the text and give their Russian equivalents.

П. Find 10 words (other than the names of elements) which have permanent equivalents in Russian.

Ш. Would you use the transcription method to transfer into Russian the

57

terms «pollutants and nutrients» in sentence (2) or would you opt for a description?

IV. Which of the following phrases, if any, would you choose to translate sentence (2): падая в воздухе, перемещаясь в воздушной среде, выпадая в виде атмосферных осадков? Give your reasons.

V. Name two Russian terms for «carbon dioxide» in sentence (3).

VI. Use a Russian prepositional phrase to translate sentence (3).

VII. How should the structure «this gives it greater power» in sentence (4) be changed in translation to fit the Russian technical usage?

VIII. Suggest a scientific turn of phrase in Russian to translate the phrase «water… serves plants and animals» in sentence (6).

IX. Should the Russian for «three states» in sentence (6) be just три состояния or should the full form агрегатные состояния be preferred?

X. Translate the phrase «it has published what appears to be some dramatic

swing» in sentence (7) transforming «it has published» into опубликованные результаты and «what appears to be» into по-видимому, свидетельствуют.

XL Discuss the pros and cons of the possible Russian structures to begin sentence (8) such as: можно подумать, как будто бы, дело обстоит так, как будто, etc.

XII. Would you retain the figure of speech in sentence (8) in your Russian translation (бородавки на лице общественного мнения) or would you prefer a less extravagant variant, e.g. изъяны?

XIII. Which Russian equivalent is more preferable as the substitute for the «public» in sentence (8): публика, общественность? Why?

XIV. Suggest two Russian idiomatic expressions equivalent to the English idiom «to wear two hats» (sentence 9).

XV. Which of the following Russian equivalents to the English phrase «to seek guidance» (sentence 12) would you prefer: искать совета, спрашивать совета, обращаться за руководством, руководствоваться? Or would you suggest something else?

B. Other Translation Problems

XVI. Make your choice among the Russian words чрезвычайный, экстраординарный, удивительный, особый as the substitute for «extraordinary» in sentence (1). Give your reasons.

XVII. What technical terms can you suggest as appropriate equivalents in such a text to the word «collects» in sentence (2)?

XVIII. What form should be used in Russian to replace the adverbial modifier of purpose expressed by the verb «to form» in sentence (3)?

XIX. What name will you give in Russian to the process which is described in sentence (4) as ‘breaking down»?

58

XX. Suggest Russian equivalents to the phrase «are … put into solution» in sentence (4).

XXI. Choose between the Russian растворяющая способность, способ-, ность растворять другие вещества as the substitute for «dissolving

ability» in sentence (5).

XXII. Does «emerges» in sentence (6) mean оказывается, выходит or остается?

XXIII. Suggest Russian equivalents to the English adjective «dramatic» in sentence (7) other than драматический or драматичный.

XXIV. What does «as all that*’ in sentence (8) mean? Would you render it into Russian or just leave it out?

XXV. Is ‘ludicrous» in sentence (9) смехотворный, смешной or rather нелепый? And would you choose for «posture» the Russian положение, поза or позиция?

XXVI. Choose the standard Russian equivalent to the English «described as» in sentence (10). Is it описываемого, именуемого or называемого?

XXVII. What would you prefer as the substitute for the adjective «malevolent» in sentence (11): злобный, злой or зловредный? And is «ghost» — привидение, призрак or rather дух?

XXVIII. Translate sentence (11) using the Russian cliche заколдованный замок. Discuss the advantages of this equivalent.

XXIX. Would you render the phrase «the definition of public opinion» in sentence (12) as определение общественного мнения or would you opt for данные об общественном мнении or something else?

XXX. Does the phrase ‘the last source» in sentence (12) mean самый последний источник or самый ненадежный источник? What is its implied sense?

There are a few ways to characterize the meaning of a word; we can do it through morphology, phonology, or even through its categorization: whether it is animate, human, female, or adult. However, there is another way to characterize the meaning of a word: namely, to characterize the word through its lexical relations.

Lexical relationships are the connections established between one word and another; for example, we all know that the opposite of “closed” is “open” and that “literature” is similar to “book”. These words have a significant relationship to one another, whereas words like “chair” and “coffee” might have no meaningful relationship; thus, certain lexical relationships can inform us about the meaning of a word.

There are a few common types of lexical relationships: synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, and polysemy. This is not all the known types of lexical relationships, but as an introduction to lexical relations, these will suffice.

Synonymy

This is perhaps the most commonly understood of all the lexical relations. Synonymy is the idea that some words have the same meaning as others, though this is not always the case; that is, there are some synonyms which cannot replace one another in a sentence, we will give some examples of this further down.

When words have the same meaning, they can replace one another without altering the meaning of a sentence; for example:

Jane is quick

Jane is fast

Jane is speedy

All three sentences have the same meaning even though they are each unique instances of that sentence; only because the meanings of all three words at the end of the sentences are the same. This, by extension, then allows each sentence to maintain the same meaning as before.

Now, this lexical relationship, as said earlier, does not necessarily hold for all synonyms. Consider some of these pairs: quick/high-speed, quick/brisk. When we do the same sentence exercise as above, we will get radically different meanings:

Jane is quick

Jane is high-speed

Jane is brisk

So, synonyms sometimes lack the same meanings when applied to a specific context or sentence; indeed, there are cases where the result will give us something incoherent or incredibly odd. Therefore, the key to remember with synonyms is that, although they have a relationship in meaning, they do not always have the same meaning in sentences.

Antonymy

Antonymy is precisely the opposite of synonymy. With antonymy, we are concerned with constructions which are opposite to one another with respect to lexical relationships. For example, ice/hot, beautiful/ugly, and big/small. These words have meanings which are opposite to one another, and these opposite meanings come in two forms: categorical and continuous.

The categorical distinction is one that has two categories that contrast one another; for example, fire/water. These are categorical because there is no continuum between them; that is, less fire never means more water and less water never means more fire. Comparatively, antonyms that are on a continuum are constructions like big/small. This is due to the relative nature of these words; meaning, when we call a horse small, it may be relative to something else like another horse. And when that same horse is compared yet again, it might be the case that the horse is now big. So, the meanings between big and small are on a continuum relative to the object of discussion.

Some example phrases of antonymy are as follows:

Jane is small

Jane is big

Jane is slow

Jane is fast

These phrases all have opposite meanings to one another, and we can see this more readily through their applications to sentences.

It is also important to note that antonymy can have issues as well, though only when we shift the nature of our communication: I.e., “The economy is going nuts,” can also be said, though sarcastically, in the following manner: “the economy is perfectly healthy”. Traditionally, “going nuts” and “mentally healthy” are viewed as opposite meanings, but when we shift the manner in which we speak, like with sarcasm, this relationship fails to hold up. Thus, antonyms work differently when we hold as an assumption a literal or straightforward view of discourse.

Hyponymy

Hyponymy is similar to the notion of embeddedness; meaning, the semantics of one object is implied by another. That is to say, because words represent objects, the semantic properties of a particular object, like whether it is a female or animate, can be embedded in a word that implies those same objects; and so, the meaning of word “x” can be embedded in word “z”. For example, “Donald Trump” implies “human,” or “animate”. This is due to the fact that Donald Trump, despite the beliefs of others, is both a human and animate. With each word, there is implied the notion of another semantic feature.

These semantic features, might I add, are organized in an ordinal fashion, which means there is a rank for embeddedness: from specific to general. The most general word would sit atop the hierarchy; so, with respect to our friend Donald Trump, the hierarchy might look something like the following:

1. Animate

2. Human

3. Male

4. Adult

There are also technical terms that are used to describe the relationships amongst these hierarchies: superordinates and co-hyponyms. In the previous example, animate would be considered superordinate to human and human would be considered superordinate to female. On the other hand, when a term is on the same level as another word, then it is named a co-hyponym; for instance, “dog” and “cat” are a co-hyponyms that have “pet” as their superordinate. So, hyponyms move from either specific to general or general to specific, where general is at the top of the hierarchy and specific is at the bottom.

So hyponymy is the idea of embedded semantic features in a hierarchical order. When we speak of Donald Trump, we necessarily bring up specific semantic features.

Polysemy

Polysemy deals with constructions that have multiple meanings; for example, “head,”, “over,” or, “letter,” can all adopt multiple meanings. These words could be considered polysemous since they each have many potential meanings.

The word “head” can be used to refer to the top of someone’s body: “Jane received a head injury”; it can be used to refer to the front of a line: “Jane is at the head of the line”. It can also be used to refer to how prepared someone is: “Jane is way ahead of the curve, she already read the chapter for next week”. So, the word “head” is polysemous since it has many meanings.

Another word with many meanings is “over”. The word “over” can be used more ways than countable; for instance, “she lives over there,” is different from, “she lives over the hill”. Even furthermore, “the lid is over the pot,” and, “is it over yet,” are both different from one another and the two previously mentioned examples. The word “over,” as said already, has more meanings than countable.

Words are not alone when it comes to being polysemous, sentences are polysemous to; for instance, “Jane hit the man with the umbrella”. Here, it is unclear as to whether Jane had hit someone with an umbrella, as though the umbrella were a weapon, or if she had bumped into someone that was holding an umbrella. And not every meaning associated with a given polysemous sentence will be the same.

So, polysemy pertains to words and phrases that can have more than one meaning; sometimes the context of a specific phrase will allow us to negate other phrases, like if someone was holding an umbrella, but when removed from context, phrases remain ambiguous. And thus, polysemy highlights the importance of analyzing semantic features of words rather than analyzing syntax alone.

Conclusion

Lexical relations are important for understanding language and cognition; they teach us how words relate to one another and how human thought and perception get organized.

On the one hand, the lexical relations allow us to create reference points for words and therefore add meaning to our language. For example, if I say, “she is as cold as ice,” we know that cold is the opposite of warmth; that is, we experience cold and warmth as two opposite ends of a spectrum. In addition, warmth has as a superordinate “love” because we associate love with warmth: i.e., she warms my heart, his touch melts me,” and so love is a superordinate of warmth. So, the antonym of warmth is cold, which then aids in our understanding of “she is as cold as ice,”: namely, she is unloving or unempathetic. These types of lexical relations are important for semantics and the understanding of language.

On the other hand, the relationships between words also teach us how it is we think about the world. The very fact that we view “happy” as the opposite of “sad” tells us something about human cognition and experience. In addition, the fact that fast and quick can mean the same thing tells us something about the organization of perception; that is, when we call something fast or quick we are paying little attention to placing it on a continuum and are instead merely observing its speed; this is evident by the fact that synonyms for speed do not necessarily entail differences within speed. So, words can reveal features about how we perceive the world.

And so, the importance of lexical relationships is that it can speak volumes about human cognition; lexical relations can allow us to infer the cognitive resources necessary to organize the world in a particular manner, or they can allow us to infer how it is that we relate phenomenon.