-

#1

Hello,

I’d like to know what

part of speech

the «such» and «as» is in the following example.

The museum has paintings by such Impressionist artists as Manet and Degas.[Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners CD-ROM 2nd Edition. CD-ROM © Macmillan Publishers Limited 2007. Text © A&C Black Publishers Ltd 2007.]

: There is nothing special about the ‘such’ and ‘as’ in the example sentence as we can see them plainly everyday. I’m just curious about their part-of-speech. The dictionary already shows three choices of part-of-speech for each of them respectively we can choose from. As for ‘such‘, there are ‘predeterminer‘, ‘determiner‘, and ‘pronoun‘. And as for ‘as‘ there are ‘conjunction‘, ‘preposition‘, and ‘adverb‘.

In my opinion, such is a determiner and as is a preposition. Then, my question is, what is the head noun phrase?

Is it ‘Impressionist artists’, or ‘Manet and Degas’?

Given such is a determiner and as a preposition, its structure would be the same as, for example, «The apple in the bowl»

and the head noun/noun phrase is, of course, «apple» not «the bowl». Therefore, I think ‘Impressionist artists’ is head noun/(phrase).

Am I correct?

Thanks.

Last edited: Oct 24, 2011

|

predeterminer |

Determiner |

|

|

What part of speech is such?

Such is very simple, but also complex, part of speech. By grammar definition, what you would find in grammar books, such can be a predeterminer or a determiner.

Here’s how such can be used in both cases.

Such as a Predeterminer

Such as a predeterminer comes before a / an (indefinite article) and a noun in the singular form. As the name says, it predetermines the noun.

For example:

- He’s such a swindler. I can’t believe I fell for his tricks.

- She’s such a queen. You can’t tell her anything.

- He’s such a bore. I can’t believe Max is dating him.

- I’ve had such luck lately with selling my parent’s old house. I sold it for a great price.

Such as a Determiner

If such is used as a determiner it is put in front of a noun in the plural form, or an uncountable noun (like money). These nouns don’t have articles, and such is used to determine their value.

For example:

- I always have a bottle of wine hidden away for such occasions. ( such – exactly this type of thing occasion)

- I didn’t know she came into such money. (Come into means to receive. She got that money but didn’t earn it through work. Got so much or such money are both good. However, got can mean to earn or have saved. Come into means specifically get something for free, like the lottery or an inheritance.)

Now, this is the grammatical definition for such. Predeterminer and determined explain what part of speech such is. However, there are other ways in which such can be used. This is why such is both simple, and complex.

|

SUCH |

||

|

ADJECTIVE |

ADVERB |

PRONOUN |

Such as an Adjective

Synonyms for SUCH as an adjective:

- like

- similar

One of the most common, and popular ways, of using such is as an adjective. It is used as an adjective to describe the kind of thing, degree, extent, quality, class, or character. Now that may seem like a lot, but the good thing is that each way of using such as an adjective is connected to a phrase.

Let’s go over them.

SUCH AS

First, let’s describe kind or character. This is connected to the phrase “such as.” We use “such as” to describe something by connecting it to something else. That way you describe the character or kind of a certain thing.

For example:

- I always wanted one of those bags. Such as the doctors used to carry.

- Do you have any couches such as this one?

SUCH THAT

Moving on to quality and degree. When describing this we use a combination of the verb be (in any tense necessary), such and that. You can remember it easily like this “be such that,” but remember to put BE in the correct tense.

Here’s a couple of examples:

- The meal was such that he had to give compliments to the chef.

- The painting is such that she couldn’t take her eyes off it.

SUCH

Last is class and extent. This one is the easiest because you only have to use such. However, you have to put nouns and adjectives around them to get the point across. While there isn’t a phrase you have to use, be careful with the adjectives and nouns around such.

Examples:

- There are other such problems across the entire country.

- Many such harsh trials were held in the past.

- You will never see such great disregard for safety ever again.

Such as an Adverb

Synonyms for SUCH as an adverb:

- extremely

- really

- so

- very

The next way to use such is as an adverb. Adverbs describe the verbs and the ways in which the verbs happen. So, such is perfect for that position.

SUCH A / AN

It can be used as an adverb in three ways. To describe a degree, something done very well or bad, and done in a specific way.

In order to describe the degree of a verb we use such like this:

- I’ve never seen someone sing with such an amazing voice.

- Have you heard there was such a big car crash downtown?

Here’s how to describe something done very well, or very badly:

- They did such a good job renovating the kitchen.

- He mishandled the project to such lengths that I don’t know we can save it.

IN SUCH A WAY

And finally to describe things done in a specific way you only need to use the phrase “in such a way.” Like this:

- We have to organize this party in such a way that she won’t find out.

- They will have to negotiate in such a way that we don’t lose the contract.

You can see that using such as an adverb isn’t connected to a lot of set phrases, but rather to everything that is around such. There aren’t many grammatical rules on how to use such as an adverb, so it’s more about the context of the sentences.

Your point is the most important thing, so make sure that part is clear and you’ll have no problems.

Such as a Pronoun

The final way to use such is as a pronoun. Pronouns are used instead of nouns, and they are: he, she, it, they, us, etc. Now, you can’t really substitute pronouns for such.

But what you can do is use such to describe a person or thing in a category, and to describe similarities between things or people.

Another way to use such as a pronoun is to exemplify someone or something. Let’s go over them one by one.

…AND SUCH

First, describing a person or thing in a category. This also means that you are describing things or people that are similar to one another.

In this case such is put at the end of a sentence, the phrase used is “and such.” Like this:

- We’re going to need cement, steel bars, equipment, and such other things.

- I used to tell my son stories about kings, queens, knights, and such.

- Please buy party supplies. Hats, paper plates, glasses, such things.

In these examples there is a category, in the first it’s construction things, second is royalty, and finally things similar to one another (party supplies).

“And such,” or “such things” simply means that anything else that could come after is in the same category.

The second way of using such is to exemplify, state or indicate something or someone. This means that you want to draw attention to the person or thing. When it’s exemplified it’s almost like a conclusion to your sentence.

Examples:

- We thought we had a great business model, but when the company failed we saw that such was not the case.

- Such is the nature of people who don’t know better.

These are the grammatical uses for such. However, there are phrases with such that are used in many other ways and have no clear grammatical definition. They are extremely useful so let’s go over a couple, and show you some examples.

Such… that

- The trip was such a pain that we had to turn back and go home.

- I can’t believe her kid is such a bully that the other kids didn’t want to come to the party.

Such as to

- We wanted to settle things peacefully, such as to stop any further conflict.

- My grandmother believes in all these superstitions, so she has a lot a trinket such as to ward off evil.

Such is / was

- You can’t just tell your friends which stocks to invest in. That’s insider trading, and such is the law.

- My mother was a good person. She helped everyone in the community. They say such was her nature.

These phrases are connected to context, more than grammar. So you can use them when you need to drive a point across.

So vs Such (Simple Infographic to Improve Your English)

What’s the difference between SO/SUCH followed by THAT?

DavidLearn wrote:

Hello teachers,

What part of speech is ‘such’? Is it an adjective because it is before a noun?

‘Badmouth’ is an idiom in this case, so I can only consider it as a noun. Right?

Can I consider ‘so much’ as a synonym for ‘such’ in this case?

Peter is such a bad-mouth!

Thanks.

_____________________________________________

«Such» is a determiner. Earlier, determiners used to be generally considered as adjectives. These days «determiners» are not considered as adjectives. They are treated as a separate classification.

Adjectives are words that modify (that is, enhance or change the meaning of) nouns. On the other hand, determiners are words that stand before nouns and tell you how determinate (how definite) the nouns are. The basic reason for not classifying «determiners» as «adjectives» is that they lack an important characteristic of adjectives: the three degrees of comparison. «Such» is an intensifier in the sub-classes of determiners. It is always used before the articles and demonstrative determiners, e.g.

— He explained the meaning of determiners in such a nice way that I can never forget their functions.

For me, «bad-mouth» is a verb that means «to say unpleasant things about another person». It is generally used in the informal sense. Some dictionaries show it with a hyphen and some show the two words as one word. However, since the simple past and past participle of the verb generally show the verb as one word, I would prefer to use «badmouthed» as one word.

The sentence in your text is:

— Peter is such a bad-mouth! (a + verb??)

Here, bad-mouth is being used as a noun. I have not come across the use of «bad-mouth» as a noun. So, I would prefer to use the word as a past participle functioning as an adjective. The suggested sentence is:

— Peter is such a badmouthed individual/person! (Determiner + Article + Adjective + Noun)

Let us see some more posts!

In the English language, the word “as” can be used for a variety of purposes. It can be used as a conjunction,preposition, or adverb depending on the context.

- Conjunction

This word is considered as a conjunction because it connects clauses in a sentence. Normally, it also means “while” or “when.” In the sample sentence below:

The dolphins popped up as we passed by.

The word “as” serves as a conjunction that connects the clause “the dolphins popped up” with the clause “we passed by.”

Definition:

a. used to indicate that something happens during the time when something is taking place

- Example:

- Peter watched her as she walked through the crowd.

b. used to indicate by comparison the way that something happens or is done

- Example:

- They all felt as Dave did.

c. because; since

- Example:

- I must prepare now as I have to go to school.

- Preposition

The word “as” is also commonly used as a preposition to indicate the time of being, or the role of a person or object. For instance, in this sentence:

Lisa had been stubborn as a teenager.

The word is categorized as a preposition because it is used to show the “time” (as a teenager) when the subject (Lisa) “had been stubborn.”

Definition:

a. used to refer to the function or character that someone or something has.

- Example:

- She got a job as a saleslady.

b. during the time of being

- Example:

- Marco had often been sick as a child.

- Adverb

In some cases, the word “as” is also used to show comparison or equivalence. For example, in the sentence:

Her hair is as soft as silk.

The word is used to compare the noun “hair” with the noun “silk” in terms of the softness.

Definition:

a. used in comparisons to refer to the extent or degree of something

- Example:

- The sinkhole is as big as a basketball court.

The words

of language, depending on various formal and semantic features, are

divided into classes. The traditional grammatical classes of words

are called “parts of speech”, since the word is distinguished not

only by grammatical, but also by semantico-lexemic properties, some

scholars also refer to parts of speech as lexico-grammatical

categories (Смирницкий).

It should

be noted that the term “parts of speech” is purely traditional

and conventional. This name was introduced in the grammatical

teaching of Ancient Greece, where no strict differenciation was drawn

between the word as a vocabulary unit and the word as a functional

element of the sentence.

In modern

linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of the

three criteria: “semantic, formal and functional” (Щерба).

The

semantic criterion presupposes (предполагать,

заключать

в

себя)

the generalized meaning, which is characteristic of all the words

constituting (составлять)

a given part of speech. This meaning is understood as the categorical

meaning of the part of speech.

The formal

criterion exposes (выставлять

на

показ)

the specific inflexional and derivational (word-building) features of

part a part of speech.

The

functional criterion concerns the syntactic role of words in the

sentence, typical of a part of speech.

These

three factors of categorical characterization of words are referred

to as ‘meaning’, form and function.

The

three-criteria characterization of parts of speech was developed and

applied to practice in Soviet linguistics. Three names are especially

notable for the elaboration of these criteria: V.V. Vinogradov

in connection with the study of Russian Grammar, A.I. Smirnitskyand

B.A. Ilyish in connection with their study of English Grammar.

Alongside

of the three-criteria principle of dividing the words into

grammatical classes modern linguistics has developed another,

narrower principle based on syntactic featuring of words only.

On

the material of Russian, the principle of syntactic approach to the

classification of word-stock were outlined in the works of A.M.

Peshkovsky. The principles of syntactic classification of English

words were worked out by L. Bloomfield and his followers L. Harris

and especially Ch. Fries.

Here

is how Ch. Fries presents his scheme of English word-classes.

For

his materials he chooses tape-recorded spontaneous conversations

which last 50 hours.

The

three typical sentences are:

Frames:

A.

The concert was good (always).

B.

The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly).

C.

The team went there.

As

a result he divides the words into 4 classes: class I, II, III, IV,

which correspond to the traditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and

adverbs.

Thus,

class I includes all words which can be used in the position of the

words ‘concert’ (frame A), clerk and tax (frame B), team (frame C),

i.e. in the position of subject and object.

Class

II includes the words which have the position of the words ‘was’,

‘remembered’, ‘went’ in the given frames, i.e. in the position of the

predicate or part of the predicate.

Class

III includes the words having the position of ‘good’, and ‘new’, i.e.

in the position of the predicative or attribute.

And

the words of class IV are used in the position of ‘there’ in Frame C,

i.e. of an adverbial modifier.

These

classes are subdivided into subtypes.

Ch.

Fries sticks to the positional approach. Thus such words as man, he,

the others, another belong to class I as they can take the position

before the words of class II, i.e. before the finite verb.

Besides

the 4 classes, Fries finds 15 groups of function words. Following the

positional approach, he includes into one and the same group the

words of quite different types.

Thus,

group A includes all words, which can take the position of the

definite article ‘the’, such as: no, your, their, both, few, much,

John’s, our, four, twenty.

But

Fries admits, that some of these words may take the position of class

I in other sentences.

Thus,

this division is very complicated, one and the same word may be found

in different classes due to its position in the sentence. So Fries’

idea, though interesting, doesn’t reach its aim to create a new

classification of classes of words, but his material gives

interesting data concerning the distribution of words and their

syntactic valency.

Today

many scholars believe that it is difficult to classify English parts

of speech using one criterion.

Some

Soviet linguists class the English parts of speech according to a

number of features.

1.

Lexico-grammatical meaning: (noun — substance, adjective — property,

verb — action, numeral — number, etc).

2.

Lexico — grammatical morphemes: (-er, -ist, -hood — noun; -fy, -ize —

verb; -ful, -less — adjective, etc).

3.

Grammatical categories and paradigms.

4.

Syntactic functions

5.

Combinability (power to combine with other words).

In

accord with the described criteria, words are divided into notional

and functional, which reflects their division in the earlier

grammatical tradition into changeable and unchangeable.

To

the notional parts of speech of the English language belong the noun,

the adjective, the numeral, the pronoun, the verb, the adverb.

To

the basic functional series of words in English belong the article,

the preposition, the conjunction, the particle, the modal word, the

interjection.

The

difference between them may be summed up as follows:

1) Notional

parts

of speech express notions and function as sentence parts (subject,

object, attribute, adverbial modifier).

2) Notional

parts

of speech have a naming function and make a sentence by themselves:

Go!

***

1)

Functional

words

(or form-words) cannot be used as parts of the sentence and cannot

make a sentence by themselves.

2)

Functional

words

have no naming function but express relations.

3)

Functional

words

have a negative combinability but a linking or specifying function.

E.g. prepositions and conjunctions are used to connect words, while

particles and articles — to specify them.

Each

part of speech is further subseries in accord with various particular

semantico-functional and formal features of the words.

Thus,

nouns are subdivided into proper and common, animate and unanimate,

countable and uncountable, conctrete and abstract.

E.g.

Mary-girl, man-earth, can-water, stone-honesty.

This

proves that the majority of English parts of speech has a field-like

structure.

The

theory of grammatical fields was worked out by V.G. Admoni on the

material of the German language.

The

essence of this theory is as follows. Every part of speech has words,

which obtain all the features of this part of speech. They are its

nucleus. But there are such words which don’t have all the features

of this part of speech, though they belong to it.

Consequently,

the field includes central and peripheral elements.

Because

of the rigid word-order in the English sentence and scantiness of

inflected forms, English parts of speech have developed a number of

grammatical meanings and an ability to be converted.

E.g.

It’s better to be a has-been than a never-was.

He

grows old. He grows roses.

The

conversation may be written one part of speech.

She

took off her glasses.

Give

me a glass of water.

The

person in the glass was making faces.

Don’t

break the glass when cleaning the window.

They

are called variants of one part of speech. Because of homonymy and

polysemy many notional words may have the same form as functional

words.

E.g.

He grows roses — He grows old.

Professor

Ilyish objects to the division of words into notional and functional

(formal) parts of speech. He says that prepositions and conjunctions

are no less notional than nouns and verbs, as they also express some

relations and connections existing independently.

Соседние файлы в папке Gosy

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

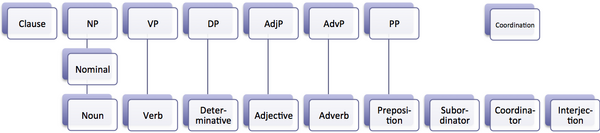

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

A part of speech is a term used in traditional grammar for one of the nine main categories into which words are classified according to their functions in sentences, such as nouns or verbs. Also known as word classes, these are the building blocks of grammar.

Parts of Speech

- Word types can be divided into nine parts of speech:

- nouns

- pronouns

- verbs

- adjectives

- adverbs

- prepositions

- conjunctions

- articles/determiners

- interjections

- Some words can be considered more than one part of speech, depending on context and usage.

- Interjections can form complete sentences on their own.

Every sentence you write or speak in English includes words that fall into some of the nine parts of speech. These include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections. (Some sources include only eight parts of speech and leave interjections in their own category.)

Learning the names of the parts of speech probably won’t make you witty, healthy, wealthy, or wise. In fact, learning just the names of the parts of speech won’t even make you a better writer. However, you will gain a basic understanding of sentence structure and the English language by familiarizing yourself with these labels.

Open and Closed Word Classes

The parts of speech are commonly divided into open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and closed classes (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections). The idea is that open classes can be altered and added to as language develops and closed classes are pretty much set in stone. For example, new nouns are created every day, but conjunctions never change.

In contemporary linguistics, the label part of speech has generally been discarded in favor of the term word class or syntactic category. These terms make words easier to qualify objectively based on word construction rather than context. Within word classes, there is the lexical or open class and the function or closed class.

Read about each part of speech below and get started practicing identifying each.

Noun

Nouns are a person, place, thing, or idea. They can take on a myriad of roles in a sentence, from the subject of it all to the object of an action. They are capitalized when they’re the official name of something or someone, called proper nouns in these cases. Examples: pirate, Caribbean, ship, freedom, Captain Jack Sparrow.

Pronoun

Pronouns stand in for nouns in a sentence. They are more generic versions of nouns that refer only to people. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, ours, them, who, which, anybody, ourselves.

Verb

Verbs are action words that tell what happens in a sentence. They can also show a sentence subject’s state of being (is, was). Verbs change form based on tense (present, past) and count distinction (singular or plural). Examples: sing, dance, believes, seemed, finish, eat, drink, be, became

Adjective

Adjectives describe nouns and pronouns. They specify which one, how much, what kind, and more. Adjectives allow readers and listeners to use their senses to imagine something more clearly. Examples: hot, lazy, funny, unique, bright, beautiful, poor, smooth.

Adverb

Adverbs describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They specify when, where, how, and why something happened and to what extent or how often. Examples: softly, lazily, often, only, hopefully, softly, sometimes.

Preposition

Prepositions show spacial, temporal, and role relations between a noun or pronoun and the other words in a sentence. They come at the start of a prepositional phrase, which contains a preposition and its object. Examples: up, over, against, by, for, into, close to, out of, apart from.

Conjunction

Conjunctions join words, phrases, and clauses in a sentence. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions. Examples: and, but, or, so, yet, with.

Articles and Determiners

Articles and determiners function like adjectives by modifying nouns, but they are different than adjectives in that they are necessary for a sentence to have proper syntax. Articles and determiners specify and identify nouns, and there are indefinite and definite articles. Examples: articles: a, an, the; determiners: these, that, those, enough, much, few, which, what.

Some traditional grammars have treated articles as a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars, however, more often include articles in the category of determiners, which identify or quantify a noun. Even though they modify nouns like adjectives, articles are different in that they are essential to the proper syntax of a sentence, just as determiners are necessary to convey the meaning of a sentence, while adjectives are optional.

Interjection

Interjections are expressions that can stand on their own or be contained within sentences. These words and phrases often carry strong emotions and convey reactions. Examples: ah, whoops, ouch, yabba dabba do!

How to Determine the Part of Speech

Only interjections (Hooray!) have a habit of standing alone; every other part of speech must be contained within a sentence and some are even required in sentences (nouns and verbs). Other parts of speech come in many varieties and may appear just about anywhere in a sentence.

To know for sure what part of speech a word falls into, look not only at the word itself but also at its meaning, position, and use in a sentence.

For example, in the first sentence below, work functions as a noun; in the second sentence, a verb; and in the third sentence, an adjective:

- Bosco showed up for work two hours late.

- The noun work is the thing Bosco shows up for.

- He will have to work until midnight.

- The verb work is the action he must perform.

- His work permit expires next month.

- The attributive noun [or converted adjective] work modifies the noun permit.

Learning the names and uses of the basic parts of speech is just one way to understand how sentences are constructed.

Dissecting Basic Sentences

To form a basic complete sentence, you only need two elements: a noun (or pronoun standing in for a noun) and a verb. The noun acts as a subject and the verb, by telling what action the subject is taking, acts as the predicate.

- Birds fly.

In the short sentence above, birds is the noun and fly is the verb. The sentence makes sense and gets the point across.

You can have a sentence with just one word without breaking any sentence formation rules. The short sentence below is complete because it’s a command to an understood «you».

- Go!

Here, the pronoun, standing in for a noun, is implied and acts as the subject. The sentence is really saying, «(You) go!»

Constructing More Complex Sentences

Use more parts of speech to add additional information about what’s happening in a sentence to make it more complex. Take the first sentence from above, for example, and incorporate more information about how and why birds fly.

- Birds fly when migrating before winter.

Birds and fly remain the noun and the verb, but now there is more description.

When is an adverb that modifies the verb fly. The word before is a little tricky because it can be either a conjunction, preposition, or adverb depending on the context. In this case, it’s a preposition because it’s followed by a noun. This preposition begins an adverbial phrase of time (before winter) that answers the question of when the birds migrate. Before is not a conjunction because it does not connect two clauses.