The terms «part of speech», «word class» and «word category» are typically used interchangeably. For a recent, brief and accessible discussion by an eminent linguist, see this paper by David Denison. Each individual word has its own part of speech.

Subject and object are grammatical relations. Grammatical relations are different from parts of speech, because parts of speech do not depend on the role of the word in the sentence, whereas grammatical relations do. For instance, in the sentence Cats like mice, the words cats and mice are both nouns, but Cats is the subject whereas mice is the direct object. In the sentence Mice like cats, it is the other way round: mice is the subject whereas cats is the direct object.

An important difference between parts of speech and grammatical relations is that phrases can bear grammatical relations, but only words can bear parts of speech. In the sentence The cats like the mice, the subject is the whole phrase The cats. The word cats is a noun, and The is an article or a determiner.

If you want to find out more about these notions, I’d recommend the book Introducing English Grammar by Börjars and Burridge (2010). It’s what we use at Manchester to teach first-year Linguistics and English Language undergraduates.

Select your language

Suggested languages for you:

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmelden

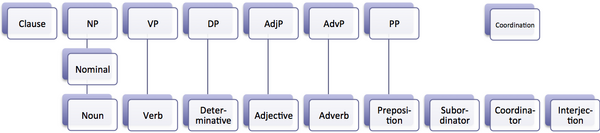

Words don’t only mean something; they also do something. In the English language, words are grouped into word classes based on their function, i.e. what they do in a phrase or sentence. In total, there are nine word classes in English.

Word class meaning and example

All words can be categorised into classes within a language based on their function and purpose.

An example of various word classes is ‘The cat ate a cupcake quickly.’

-

The = a determiner

-

cat = a noun

-

ate = a verb

-

a = determiner

-

cupcake = noun

-

quickly = an adverb

Word class function

The function of a word class, also known as a part of speech, is to classify words according to their grammatical properties and the roles they play in sentences. By assigning words to different word classes, we can understand how they should be used in context and how they relate to other words in a sentence.

Each word class has its own unique set of characteristics and rules for usage, and understanding the function of word classes is essential for effective communication in English. Knowing our word classes allows us to create clear and grammatically correct sentences that convey our intended meaning.

Word classes in English

In English, there are four main word classes; nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. These are considered lexical words, and they provide the main meaning of a phrase or sentence.

The other five word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are considered functional words, and they provide structural and relational information in a sentence or phrase.

Don’t worry if it sounds a bit confusing right now. Read ahead and you’ll be a master of the different types of word classes in no time!

| All word classes | Definition | Examples of word classification |

| Noun | A word that represents a person, place, thing, or idea. | cat, house, plant |

| Pronoun | A word that is used in place of a noun to avoid repetition. | he, she, they, it |

| Verb | A word that expresses action, occurrence, or state of being. | run, sing, grow |

| Adjective | A word that describes or modifies a noun or pronoun. | blue, tall, happy |

| Adverb | A word that describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or other adverb. | quickly, very |

| Preposition | A word that shows the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. | in, on, at |

| Conjunction | A word that connects words, phrases, or clauses. | and, or, but |

| Interjection | A word that expresses strong emotions or feelings. | wow, oh, ouch |

| Determiners | A word that clarifies information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun | Articles like ‘the’ and ‘an’, and quantifiers like ‘some’ and ‘all’. |

The four main word classes

In the English language, there are four main word classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Let’s look at all the word classes in detail.

Nouns

Nouns are the words we use to describe people, places, objects, feelings, concepts, etc. Usually, nouns are tangible (touchable) things, such as a table, a person, or a building.

However, we also have abstract nouns, which are things we can feel and describe but can’t necessarily see or touch, such as love, honour, or excitement. Proper nouns are the names we give to specific and official people, places, or things, such as England, Claire, or Hoover.

Cat

House

School

Britain

Harry

Book

Hatred

‘My sister went to school.‘

Verbs

Verbs are words that show action, event, feeling, or state of being. This can be a physical action or event, or it can be a feeling that is experienced.

Lexical verbs are considered one of the four main word classes, and auxiliary verbs are not. Lexical verbs are the main verb in a sentence that shows action, event, feeling, or state of being, such as walk, ran, felt, and want, whereas an auxiliary verb helps the main verb and expresses grammatical meaning, such as has, is, and do.

Run

Walk

Swim

Curse

Wish

Help

Leave

‘She wished for a sunny day.’

Adjectives

Adjectives are words used to modify nouns, usually by describing them. Adjectives describe an attribute, quality, or state of being of the noun.

Long

Short

Friendly

Broken

Loud

Embarrassed

Dull

Boring

‘The friendly woman wore a beautiful dress.’

Adverbs

Adverbs are words that work alongside verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. They provide further descriptions of how, where, when, and how often something is done.

Quickly

Softly

Very

More

Too

Loudly

‘The music was too loud.’

All of the above examples are lexical word classes and carry most of the meaning in a sentence. They make up the majority of the words in the English language.

The other five word classes

The other five remaining word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These words are considered functional words and are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

For example, prepositions can be used to explain where one object is in relation to another.

Prepositions

Prepositions are used to show the relationship between words in terms of place, time, direction, and agency.

In

At

On

Towards

To

Through

Into

By

With

‘They went through the tunnel.’

Pronouns

Pronouns take the place of a noun or a noun phrase in a sentence. They often refer to a noun that has already been mentioned and are commonly used to avoid repetition.

Chloe (noun) → she (pronoun)

Chloe’s dog → her dog (possessive pronoun)

There are several different types of pronouns; let’s look at some examples of each.

- He, she, it, they — personal pronouns

- His, hers, its, theirs, mine, ours — possessive pronouns

- Himself, herself, myself, ourselves, themselves — reflexive pronouns

- This, that, those, these — demonstrative pronouns

- Anyone, somebody, everyone, anything, something — Indefinite pronouns

- Which, what, that, who, who — Relative pronouns

‘She sat on the chair which was broken.’

Determiners

Determiners work alongside nouns to clarify information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun. It ‘determines’ exactly what is being referred to. Much like pronouns, there are also several different types of determiners.

- The, a, an — articles

- This, that, those — you might recognise these for demonstrative pronouns are also determiners

- One, two, three etc. — cardinal numbers

- First, second, third etc. — ordinal numbers

- Some, most, all — quantifiers

- Other, another — difference words

‘The first restaurant is better than the other.’

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses together within a sentence. There are three main types of conjunctions;

-

Coordinating conjunctions — these link independent clauses together.

-

Subordinating conjunctions — these link dependent clauses to independent clauses.

- Correlative conjunctions — words that work in pairs to join two parts of a sentence of equal importance.

For, and, nor, but, or, yet, so — coordinating conjunctions

After, as, because, when, while, before, if, even though — subordinating conjunctions

Either/or, neither/nor, both/and — correlative conjunctions

‘If it rains, I’m not going out.’

Interjections

Interjections are exclamatory words used to express an emotion or a reaction. They often stand alone from the rest of the sentence and are accompanied by an exclamation mark.

Oh

Oops!

Phew!

Ahh!

‘Oh, what a surprise!’

Word class: lexical classes and function classes

A helpful way to understand lexical word classes is to see them as the building blocks of sentences. If the lexical word classes are the blocks themselves, then the function word classes are the cement holding the words together and giving structure to the sentence.

In this diagram, the lexical classes are in blue and the function classes are in yellow. We can see that the words in blue provide the key information, and the words in yellow bring this information together in a structured way.

Word class examples

Sometimes it can be tricky to know exactly which word class a word belongs to. Some words can function as more than one word class depending on how they are used in a sentence. For this reason, we must look at words in context, i.e. how a word works within the sentence. Take a look at the following examples of word classes to see the importance of word class categorisation.

The dog will bark if you open the door.

The tree bark was dark and rugged.

Here we can see that the same word (bark) has a different meaning and different word class in each sentence. In the first example, ‘bark’ is used as a verb, and in the second as a noun (an object in this case).

I left my sunglasses on the beach.

The horse stood on Sarah’s left foot.

In the first sentence, the word ‘left’ is used as a verb (an action), and in the second, it is used to modify the noun (foot). In this case, it is an adjective.

I run every day

I went for a run

In this example, ‘run’ can be a verb or a noun.

Word Class — Key takeaways

-

We group words into word classes based on the function they perform in a sentence.

-

The four main word classes are nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. These are lexical classes that give meaning to a sentence.

-

The other five word classes are prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are function classes that are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

-

It is important to look at the context of a sentence in order to work out which word class a word belongs to.

Frequently Asked Questions about Word Class

A word class is a group of words that have similar properties and play a similar role in a sentence.

Some examples of how some words can function as more than one word class include the way ‘run’ can be a verb (‘I run every day’) or a noun (‘I went for a run’). Similarly, ‘well’ can be an adverb (‘He plays the guitar well’) or an adjective (‘She’s feeling well today’).

The nine word classes are; Nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, interjections.

Categorising words into word classes helps us to understand the function the word is playing within a sentence.

Parts of speech is another term for word classes.

The different groups of word classes include lexical classes that act as the building blocks of a sentence e.g. nouns. The other word classes are function classes that act as the ‘glue’ and give grammatical information in a sentence e.g. prepositions.

The word classes for all, that, and the is:

‘All’ = determiner (quantifier)

‘That’ = pronoun and/or determiner (demonstrative pronoun)

‘The’ = determiner (article)

Final Word Class Quiz

Word Class Quiz — Teste dein Wissen

Question

A word can only belong to one type of noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is false. A word can belong to multiple categories of nouns and this may change according to the context of the word.

Show question

Question

Name the two principal categories of nouns.

Show answer

Answer

The two principal types of nouns are ‘common nouns’ and ‘proper nouns’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following is an example of a proper noun?

Show answer

Question

Name the 6 types of common nouns discussed in the text.

Show answer

Answer

Concrete nouns, abstract nouns, countable nouns, uncountable nouns, collective nouns, and compound nouns.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a concrete noun and an abstract noun?

Show answer

Answer

A concrete noun is a thing that physically exists. We can usually touch this thing and measure its proportions. An abstract noun, however, does not physically exist. It is a concept, idea, or feeling that only exists within the mind.

Show question

Question

Pick out the concrete noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

Pick out the abstract noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the difference between a countable and an uncountable noun? Can you think of an example for each?

Show answer

Answer

A countable noun is a thing that can be ‘counted’, i.e. it can exist in the plural. Some examples include ‘bottle’, ‘dog’ and ‘boy’. These are often concrete nouns.

An uncountable noun is something that can not be counted, so you often cannot place a number in front of it. Examples include ‘love’, ‘joy’, and ‘milk’.

Show question

Question

Pick out the collective noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the collective noun for a group of sheep?

Show answer

Answer

The collective noun is a ‘flock’, as in ‘flock of sheep’.

Show question

Question

The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is true. The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun as it is made up of two separate words ‘green’ and ‘house’. These come together to form a new word.

Show question

Question

What are the adjectives in this sentence?: ‘The little boy climbed up the big, green tree’

Show answer

Answer

The adjectives are ‘little’ and ‘big’, and ‘green’ as they describe features about the nouns.

Show question

Question

Place the adjectives in this sentence into the correct order: the wooden blue big ship sailed across the Indian vast scary ocean.

Show answer

Answer

The big, blue, wooden ship sailed across the vast, scary, Indian ocean.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 different positions in which an adjective can be placed?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective can be placed before a noun (pre-modification), after a noun (post-modification), or following a verb as a complement.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘The unicorn is angry’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘angry’ post-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘It is a scary unicorn’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘scary’ pre-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘purple’ and ‘shiny’?

Show answer

Answer

‘Purple’ and ‘Shiny’ are qualitative adjectives as they describe a quality or feature of a noun

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’?

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’ are evaluative adjectives as they give a subjective opinion on the noun.

Show question

Question

Which of the following adjectives is an absolute adjective?

Show answer

Question

Which of these adjectives is a classifying adjective?

Show answer

Question

Convert the noun ‘quick’ to its comparative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘quick’ is ‘quicker’.

Show question

Question

Convert the noun ‘slow’ to its superlative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘slow’ is ‘slowest’.

Show question

Question

What is an adjective phrase?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective phrase is a group of words that is ‘built’ around the adjective (it takes centre stage in the sentence). For example, in the phrase ‘the dog is big’ the word ‘big’ is the most important information.

Show question

Question

Give 2 examples of suffixes that are typical of adjectives.

Show answer

Answer

Suffixes typical of adjectives include -able, -ible, -ful, -y, -less, -ous, -some, -ive, -ish, -al.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a main verb and an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

A main verb is a verb that can stand on its own and carries most of the meaning in a verb phrase. For example, ‘run’, ‘find’. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone, instead, they work alongside a main verb and ‘help’ the verb to express more grammatical information e.g. tense, mood, possibility.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a primary auxiliary verb and a modal auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

Primary auxiliary verbs consist of the various forms of ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’ e.g. ‘had’, ‘was’, ‘done’. They help to express a verb’s tense, voice, or mood. Modal auxiliary verbs show possibility, ability, permission, or obligation. There are 9 auxiliary verbs including ‘could’, ‘will’, might’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are primary auxiliary verbs?

-

Is

-

Play

-

Have

-

Run

-

Does

-

Could

Show answer

Answer

The primary auxiliary verbs in this list are ‘is’, ‘have’, and ‘does’. They are all forms of the main primary auxiliary verbs ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’. ‘Play’ and ‘run’ are main verbs and ‘could’ is a modal auxiliary verb.

Show question

Question

Name 6 out of the 9 modal auxiliary verbs.

Show answer

Answer

Answers include: Could, would, should, may, might, can, will, must, shall

Show question

Question

‘The fairies were asleep’. In this sentence, is the verb ‘were’ a linking verb or an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

The word ‘were’ is used as a linking verb as it stands alone in the sentence. It is used to link the subject (fairies) and the adjective (asleep).

Show question

Question

What is the difference between dynamic verbs and stative verbs?

Show answer

Answer

A dynamic verb describes an action or process done by a noun or subject. They are thought of as ‘action verbs’ e.g. ‘kick’, ‘run’, ‘eat’. Stative verbs describe the state of being of a person or thing. These are states that are not necessarily physical action e.g. ‘know’, ‘love’, ‘suppose’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are dynamic verbs and which are stative verbs?

-

Drink

-

Prefer

-

Talk

-

Seem

-

Understand

-

Write

Show answer

Answer

The dynamic verbs are ‘drink’, ‘talk’, and ‘write’ as they all describe an action. The stative verbs are ‘prefer’, ‘seem’, and ‘understand’ as they all describe a state of being.

Show question

Question

What is an imperative verb?

Show answer

Answer

Imperative verbs are verbs used to give orders, give instructions, make a request or give warning. They tell someone to do something. For example, ‘clean your room!’.

Show question

Question

Inflections give information about tense, person, number, mood, or voice. True or false?

Show answer

Question

What information does the inflection ‘-ing’ give for a verb?

Show answer

Answer

The inflection ‘-ing’ is often used to show that an action or state is continuous and ongoing.

Show question

Question

How do you know if a verb is irregular?

Show answer

Answer

An irregular verb does not take the regular inflections, instead the whole word is spelt a different way. For example, begin becomes ‘began’ or ‘begun’. We can’t add the regular past tense inflection -ed as this would become ‘beginned’ which doesn’t make sense.

Show question

Question

Suffixes can never signal what word class a word belongs to. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. Suffixes can signal what word class a word belongs to. For example, ‘-ify’ is a common suffix for verbs (‘identity’, ‘simplify’)

Show question

Question

A verb phrase is built around a noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. A verb phrase is a group of words that has a main verb along with any other auxiliary verbs that ‘help’ the main verb. For example, ‘could eat’ is a verb phrase as it contains a main verb (‘could’) and an auxiliary verb (‘could’).

Show question

Question

Which of the following are multi-word verbs?

-

Shake

-

Rely on

-

Dancing

-

Look up to

Show answer

Answer

The verbs ‘rely on’ and ‘look up to’ are multi-word verbs as they consist of a verb that has one or more prepositions or particles linked to it.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a transition verb and an intransitive verb?

Show answer

Answer

Transitive verbs are verbs that require an object in order to make sense. For example, the word ‘bring’ requires an object that is brought (‘I bring news’). Intransitive verbs do not require an object to complete the meaning of the sentence e.g. ‘exist’ (‘I exist’).

Show question

Answer

An adverb is a word that gives more information about a verb, adjective, another adverb, or a full clause.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 ways we can use adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

We can use adverbs to modify a word (modifying adverbs), to intensify a word (intensifying adverbs), or to connect two clauses (connecting adverbs).

Show question

Question

What are modifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Modifying adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They add further information about the word.

Show question

Question

‘Additionally’, ‘likewise’, and ‘consequently’ are examples of connecting adverbs. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

True! Connecting adverbs are words used to connect two independent clauses.

Show question

Question

What are intensifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Intensifying adverbs are words used to strengthen the meaning of an adjective, another adverb, or a verb. In other words, they ‘intensify’ another word.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are intensifying adverbs?

-

Calmly

-

Incredibly

-

Enough

-

Greatly

Show answer

Answer

The intensifying adverbs are ‘incredibly’ and ‘greatly’. These strengthen the meaning of a word.

Show question

Question

Name the main types of adverbs

Show answer

Answer

The main adverbs are; adverbs of place, adverbs of time, adverbs of manner, adverbs of frequency, adverbs of degree, adverbs of probability, and adverbs of purpose.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of time?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of time are the ‘when?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘when is the action done?’ e.g. ‘I’ll do it tomorrow’

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of frequency?

-

Usually

-

Patiently

-

Occasionally

-

Nowhere

Show answer

Answer

The adverbs of frequency are ‘usually’ and ‘occasionally’. They are the ‘how often?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘how often is the action done?’.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of place?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of place are the ‘where?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘where is the action done?’. For example, ‘outside’ or ‘elsewhere’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of manner?

-

Never

-

Carelessly

-

Kindly

-

Inside

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘carelessly’ and ‘kindly’ are adverbs of manner. They are the ‘how?’ adverbs that answer the question ‘how is the action done?’.

Show question

Discover the right content for your subjects

No need to cheat if you have everything you need to succeed! Packed into one app!

Study Plan

Be perfectly prepared on time with an individual plan.

Quizzes

Test your knowledge with gamified quizzes.

Flashcards

Create and find flashcards in record time.

Notes

Create beautiful notes faster than ever before.

Study Sets

Have all your study materials in one place.

Documents

Upload unlimited documents and save them online.

Study Analytics

Identify your study strength and weaknesses.

Weekly Goals

Set individual study goals and earn points reaching them.

Smart Reminders

Stop procrastinating with our study reminders.

Rewards

Earn points, unlock badges and level up while studying.

Magic Marker

Create flashcards in notes completely automatically.

Smart Formatting

Create the most beautiful study materials using our templates.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We’ll assume you’re ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Privacy & Cookies Policy

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution. The term «word class» is similar to the more traditional term, part of speech. It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).

The two major families of word classes are lexical (or open or form) classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) and function (or closed or structure) classes (determiners, particles, prepositions, and others).

Examples and Observations

- «When linguists began to look closely at English grammatical structure in the 1940s and 1950s, they encountered so many problems of identification and definition that the term part of speech soon fell out of favor, word class being introduced instead. Word classes are equivalent to parts of speech, but defined according to strict linguistic criteria.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- «There is no single correct way of analyzing words into word classes…Grammarians disagree about the boundaries between the word classes (see gradience), and it is not always clear whether to lump subcategories together or to split them. For example, in some grammars…pronouns are classed as nouns, whereas in other frameworks…they are treated as a separate word class.» (Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker, Edmund Weiner, The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014)

Form Classes and Structure Classes

«[The] distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning determines the first division in our classification: form-class words and structure-class words. In general, the form classes provide the primary lexical content; the structure classes explain the grammatical or structural relationship. Think of the form-class words as the bricks of the language and the structure words as the mortar that holds them together.»

The form classes also known as content words or open classes include:

- Nouns

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

The structure classes, also known as function words or closed classes, include:

- Determiners

- Pronouns

- Auxiliaries

- Conjunctions

- Qualifiers

- Interrogatives

- Prepositions

- Expletives

- Particles

«Probably the most striking difference between the form classes and the structure classes is characterized by their numbers. Of the half million or more words in our language, the structure words—with some notable exceptions—can be counted in the hundreds. The form classes, however, are large, open classes; new nouns and verbs and adjectives and adverbs regularly enter the language as new technology and new ideas require them.» (Martha Kolln and Robert Funk, Understanding English Grammar. Allyn and Bacon, 1998)

One Word, Multiple Classes

«Items may belong to more than one class. In most instances, we can only assign a word to a word class when we encounter it in context. Looks is a verb in ‘It looks good,’ but a noun in ‘She has good looks‘; that is a conjunction in ‘I know that they are abroad,’ but a pronoun in ‘I know that‘ and a determiner in ‘I know that man’; one is a generic pronoun in ‘One must be careful not to offend them,’ but a numeral in ‘Give me one good reason.'» (Sidney Greenbaum, Oxford English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 1996)

Suffixes as Signals

«We recognize the class of a word by its use in context. Some words have suffixes (endings added to words to form new words) that help to signal the class they belong to. These suffixes are not necessarily sufficient in themselves to identify the class of a word. For example, -ly is a typical suffix for adverbs (slowly, proudly), but we also find this suffix in adjectives: cowardly, homely, manly. And we can sometimes convert words from one class to another even though they have suffixes that are typical of their original class: an engineer, to engineer; a negative response, a negative.» (Sidney Greenbaum and Gerald Nelson, An Introduction to English Grammar, 3rd ed. Pearson, 2009)

A Matter of Degree

«[N]ot all the members of a class will necessarily have all the identifying properties. Membership in a particular class is really a matter of degree. In this regard, grammar is not so different from the real world. There are prototypical sports like ‘football’ and not so sporty sports like ‘darts.’ There are exemplary mammals like ‘dogs’ and freakish ones like the ‘platypus.’ Similarly, there are good examples of verbs like watch and lousy examples like beware; exemplary nouns like chair that display all the features of a typical noun and some not so good ones like Kenny.» (Kersti Börjars and Kate Burridge, Introducing English Grammar, 2nd ed. Hodder, 2010)

A part of speech (also called a word class) is a category that describes the role a word plays in a sentence. Understanding the different parts of speech can help you analyze how words function in a sentence and improve your writing.

The parts of speech are classified differently in different grammars, but most traditional grammars list eight parts of speech in English: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections. Some modern grammars add others, such as determiners and articles.

Many words can function as different parts of speech depending on how they are used. For example, “laugh” can be a noun (e.g., “I like your laugh”) or a verb (e.g., “don’t laugh”).

Nouns

A noun is a word that refers to a person, concept, place, or thing. Nouns can act as the subject of a sentence (i.e., the person or thing performing the action) or as the object of a verb (i.e., the person or thing affected by the action).

There are numerous types of nouns, including common nouns (used to refer to nonspecific people, concepts, places, or things), proper nouns (used to refer to specific people, concepts, places, or things), and collective nouns (used to refer to a group of people or things).

Ella lives in France.

The band played only new songs.

Other types of nouns include countable and uncountable nouns, concrete nouns, abstract nouns, and gerunds.

Pronouns

A pronoun is a word used in place of a noun. Pronouns typically refer back to an antecedent (a previously mentioned noun) and must demonstrate correct pronoun-antecedent agreement. Like nouns, pronouns can refer to people, places, concepts, and things.

There are numerous types of pronouns, including personal pronouns (used in place of the proper name of a person), demonstrative pronouns (used to refer to specific things and indicate their relative position), and interrogative pronouns (used to introduce questions about things, people, and ownership).

That is a horrible painting!

Who owns the nice car?

Verbs

A verb is a word that describes an action (e.g., “jump”), occurrence (e.g., “become”), or state of being (e.g., “exist”). Verbs indicate what the subject of a sentence is doing. Every complete sentence must contain at least one verb.

Verbs can change form depending on subject (e.g., first person singular), tense (e.g., past simple), mood (e.g., interrogative), and voice (e.g., passive voice).

Regular verbs are verbs whose simple past and past participle are formed by adding“-ed” to the end of the word (or “-d” if the word already ends in “e”). Irregular verbs are verbs whose simple past and past participles are formed in some other way.

“I’ve already checked twice.”

“I heard that you used to sing.”

“Yes! I sang in a choir for 10 years.”

Other types of verbs include auxiliary verbs, linking verbs, modal verbs, and phrasal verbs.

Adjectives

An adjective is a word that describes a noun or pronoun. Adjectives can be attributive, appearing before a noun (e.g., “a red hat”), or predicative, appearing after a noun with the use of a linking verb like “to be” (e.g., “the hat is red”).

Adjectives can also have a comparative function. Comparative adjectives compare two or more things. Superlative adjectives describe something as having the most or least of a specific characteristic.

He is the laziest person I know

Other types of adjectives include coordinate adjectives, participial adjectives, and denominal adjectives.

Adverbs

An adverb is a word that can modify a verb, adjective, adverb, or sentence. Adverbs are often formed by adding “-ly” to the end of an adjective (e.g., “slow” becomes “slowly”), although not all adverbs have this ending, and not all words with this ending are adverbs.

There are numerous types of adverbs, including adverbs of manner (used to describe how something occurs), adverbs of degree (used to indicate extent or degree), and adverbs of place (used to describe the location of an action or event).

Talia writes quite quickly.

Let’s go outside!

Other types of adverbs include adverbs of frequency, adverbs of purpose, focusing adverbs, and adverbial phrases.

Prepositions

A preposition is a word (e.g., “at”) or phrase (e.g., “on top of”) used to show the relationship between the different parts of a sentence. Prepositions can be used to indicate aspects such as time, place, and direction.

I left the cup on the kitchen counter.

Carey walked to the shop.

Conjunctions

A conjunction is a word used to connect different parts of a sentence (e.g., words, phrases, or clauses).

The main types of conjunctions are coordinating conjunctions (used to connect items that are grammatically equal), subordinating conjunctions (used to introduce a dependent clause), and correlative conjunctions (used in pairs to join grammatically equal parts of a sentence).

You can choose what movie we watch because I chose the last time.

We can either go out for dinner or go to the theater.

Interjections

An interjection is a word or phrase used to express a feeling, give a command, or greet someone. Interjections are a grammatically independent part of speech, so they can often be excluded from a sentence without affecting the meaning.

Types of interjections include volitive interjections (used to make a demand or request), emotive interjections (used to express a feeling or reaction), cognitive interjections (used to indicate thoughts), and greetings and parting words (used at the beginning and end of a conversation).

Ouch! I hurt my arm.

I’m, um, not sure.

Hey! How are you doing?

Other parts of speech

The traditional classification of English words into eight parts of speech is by no means the only one or the objective truth. Grammarians have often divided them into more or fewer classes. Other commonly mentioned parts of speech include determiners and articles.

Determiners

A determiner is a word that describes a noun by indicating quantity, possession, or relative position.

Common types of determiners include demonstrative determiners (used to indicate the relative position of a noun), possessive determiners (used to describe ownership), and quantifiers (used to indicate the quantity of a noun).

My brother is selling his old car.

Many friends of mine have part-time jobs.

Other types of determiners include distributive determiners, determiners of difference, and numbers.

NoteIn the traditional eight parts of speech, these words are usually classed as adjectives, or in some cases as pronouns.

Articles

An article is a word that modifies a noun by indicating whether it is specific or general.

- The definite article the is used to refer to a specific version of a noun. The can be used with all countable and uncountable nouns (e.g., “the door,” “the energy,” “the mountains”).

- The indefinite articles a and an refer to general or unspecific nouns. The indefinite articles can only be used with singular countable nouns (e.g., “a poster,” “an engine”).

There’s a concert this weekend.

Karl made an offensive gesture.

Interesting language articles

If you want to know more about nouns, pronouns, verbs, and other parts of speech, make sure to check out some of our language articles with explanations and examples.

Verbs

- Verb tenses

- Phrasal verbs

- Types of verbs

- Active vs passive voice

- Subject-verb agreement

Other

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Adjectives

- Determiners

- Prepositions

Frequently asked questions

-

What part of speech is “in”?

-

In is primarily classed as a preposition, but it can be classed as various other parts of speech, depending on how it is used:

- Preposition (e.g., “in the field”)

- Noun (e.g., “I have an in with that company”)

- Adjective (e.g., “Tim is part of the in crowd”)

- Adverb (e.g., “Will you be in this evening?”)

-

What part of speech is “and”?

-

As a part of speech, and is classed as a conjunction. Specifically, it’s a coordinating conjunction.

And can be used to connect grammatically equal parts of a sentence, such as two nouns (e.g., “a cup and plate”), or two adjectives (e.g., “strong and smart”). And can also be used to connect phrases and clauses.

Is this article helpful?

You have already voted. Thanks

Your vote is saved

Processing your vote…

The basic building blocks of any language are the words and sounds of that language. English is no exception. We will start with the categories into which we classify the words of English. It is quite likely that you will already know the names of some or all of the parts of speech. Nevertheless, this is where we must begin.

The parts of speech are as follows:

- Nouns

- Pronouns

- Adjectives

- Verbs

- Adverbs

- Articles

- Determiners

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Prepositions

These are also known as word classes. The terms are familiar to most people, and are in everyday use. However, many people would probably admit that their understanding of some of them is a little sketchy. We will now take each in turn and have a closer look.

Nouns

What are nouns? Very few people with a good knowledge of English would expect to experience any difficulty in picking the nouns out of the following list:

briefcase, open, disc, plate, London, knife, write, usually, and, however, football, sing

My guess is that you probably decided that the following were nouns:

- briefcase

- disc

- plate

- London

- knife

- football

Who knows? Perhaps you are right. Briefcase is certainly a noun and London as a place name must be, but what about knife? This is a more difficult decision. We have no context. What if we found this word in a sentence such as ‘He knifed me!’ — surely here it is a verb? And what about ‘plate’ — is this a noun? Suppose the context were ‘The window was plate glass.’ Or perhaps, ‘The frame had been plated with silver.’ So is ‘disc’ a noun? Not always, it depends on how it is used in a particular sentence. The lesson here is ‘Be careful!’ When a student asks you the meaning of a word, always check the context in which it appears before answering. Remember in the world of TEFL, as in the world in general, it is not what you don’t know that gives you the biggest problems, but what you think you know!

So how can we define the word class ‘noun’ then? One apparently acceptable definition might be that a noun is a word that represents one of the following:

|

a person |

David |

|

a place |

Paris |

|

a thing |

stapler |

|

an activity |

hockey |

|

a quality |

responsibility |

|

a state |

poverty |

|

an idea |

communism |

Does a noun have to be a single word? What about ‘disc jockey,’ or ‘post office’? Are these nouns? The answer is ‘Yes they are’. These are called compound nouns and are quite common in English. So the word class ‘noun’ is not restricted to single words. Can a noun consist of more than two words then? Once again the answer is ‘yes’. An example might be ‘football team coach’. These are often found in newspaper headlines, where space is at a premium, since they usually express quite complex ideas in very few words.

In a sentence nouns can be used as either the subject or the object of the main verb.

John (subject) kissed (verb) Maria (object).

Types of Nouns

The word class ‘Nouns’ can be sub-divided into the following four types:

|

Abstract |

The name of an action, an idea, a physical condition, quality or state of mind |

an attack, Communism, liveliness, modesty, insanity |

|

Collective |

A name for a collection or group of animals, people or things that are thought of as being one thing |

flock, gang, fleet |

|

Common |

A name that can be applied to all members of a large class of animals, people or things |

puppy, woman, banana |

|

Proper |

The name by which a particular animal, organisation, person, place or thing is known |

Fido, Microsoft, Julia, Liverpool, the Tower of London. Capital letters are used in order to distinguish between common nouns and proper nouns e.g., broom and Broom, where the former is an implement used for sweeping floors while the latter is a surname. |

There are some nouns that can be placed in more than one of these groups depending on how we are thinking at the time of usage. An example would be the noun ‘family’, which could be a collective if we are thinking of the family as a unit e.g. ‘My family is quite large.’ Or a common noun if we are thinking in terms of a collection of individuals e.g. Helen’s family are coming up next week.’ Many Americans may find this particular example unacceptable since in most parts of the US ‘family’ can never agree with the plural verb form ‘is’. In British English, however, this usage is perfectly correct.

Nouns can also be divided into two other groups: countable and uncountable. Water, flour and sand are examples of uncountable nouns. It would be very strange to use them with a number as in six flours or three sands. Countable nouns, on the other hand, can be used with numbers: seven men, two houses, etc. Countable nouns have a plural form. This is usually made by the addition of an ‘s’ or ‘es’ to the end of the singular form: guitars, books, ships, glasses etc. Some countable nouns, however, have an irregular plural form: men, children, wives, geese, etc. Plural countable nouns are always used with plural verb forms. So ‘Coconuts are nice.’ and not *’Coconuts is nice.’* Uncountable nouns have only one form and therefore can only be used with singular verbs. So ‘Water is used as a coolant.’ but never *’Water are used as a coolant.’*

Back to Top

Pronouns

In English, sentences such as ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see John wasn’t being watched and then John knocked on the door twice.’ would cause confusion. How many Johns are involved? Which of them knocked on the door? Probably the solution least likely to occur to a native speaker of English would be that there was only one John and that he carried out all three actions. Why is that? Well, it’s because English just doesn’t work like that! The sentence should be rendered thus ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see he wasn’t being watched and then knocked on the door twice.’ So what makes the difference? Obviously it must be the use of the word ‘he’ in place of John in the second instance. What is ‘he’ then? ‘He’ is a member of the word class Pronouns. These are words that stand in the place of nouns in order to avoid unnecessary repetition.

Kinds of pronoun:

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those, the former, the latter ( ‘Have you seen this?’) |

|

Distributive |

each, either, neither ( ‘Give me either.’) |

|

Emphatic |

myself, yourself, his/herself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘Do it yourself.’) |

|

Indefinite |

one, some, any, some-body/one, any-body/one, every-body/one |

|

Interrogative |

what, which, who ( ‘Who was that?’) |

|

Personal |

I, you, he, she, it, we, you, they |

|

Possessive |

mine, yours hers, his, ours, theirs |

|

Reflexive |

myself, yourself, her/himself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘She cut herself, while slicing bread.’) |

|

Relative |

that, what, which, who (as in, ‘The car that hit him went that way.’) |

It should be noted that some of these words may also at times be deemed adjectives. It is a feature of the English language that many words have multiple uses and hence can be different parts of speech according to the context in which they are found.

Back to Top

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that describe/qualify nouns or pronouns:

- ‘She was a quiet woman.’

- ‘That’s an unusual one.’

Types of adjective

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those (‘I like this picture.‘) |

|

Distributive |

either, neither, each, every (‘Either wine is fine by me.‘) |

|

Interrogative |

what? which? (‘Which wine would you like?‘) |

|

Numeral |

one, two, three, etc. |

|

Indefinite |

all, many, several |

|

Possessive |

my, your, his, her, our, their |

|

Qualitative |

French, wooden, nice |

Not surprisingly, most adjectives fit into the ‘Qualitative‘ category, as their basic function is to describe.

Some adjectives are made from nouns or verbs by the addition of a suffix:

- comfort — comfortable

- health — healthy

- success — successful

- consume — consumable

- consider — considerate

Many positive adjectives can be made negative by the addition of a prefix:

- comfortable — uncomfortable

- responsible — irresponsible

- respectful — disrespectful

- patient — impatient

- considerate — inconsiderate

Comparative and Superlative Adjectives

Some adjectives are used to compare and contrast things:

- big — bigger — biggest

- happy — happier — happiest

There is more information about this important use later.

Verbs

Verbs are words that indicate actions or physical and/or mental states.

|

Action |

Susan slapped Michael. |

|

Mental state |

Paul was exhausted. |

|

Physical state |

Stephen felt sad. |

It is a popular misconception that verbs are ‘doing-words‘. Unfortunately, this is too simple an explanation as only some verbs fit this description. An example of one that doesn’t might be ‘seem‘ as in, ‘ Sarah seemed puzzled‘. What is ‘done‘ in this case? Absolutely nothing! In fact, only verbs indicating actions can be called ‘doing-words‘.

Most verbs have three forms. The first form (present) also uses an inflection to indicate third person singular:

|

First form (present) |

Second form (past) |

Third form (past participle) |

|

do(es) |

did |

done |

|

give(s) |

gave |

given |

|

like(s) |

liked |

liked |

|

hit(s) |

hit |

hit |

As you can see sometimes the second and third forms coincide, and occasionally all three forms coincide as in ‘hit’. This is because verbs such as hit, give, take, do, have, etc. are irregular. That is to say that, unlike the vast majority of English verbs, they don’t use ‘-ed’ to make their second and third forms. There are only about two hundred irregular verbs in total, but since they tend to be the most common verbs it seems more. These can be quite a problem for EFL students as they simply have to be learnt and remembered.

Auxiliary and Modal Auxiliary Verbs

There is a category of verb known as ‘auxiliary verbs‘ or sometimes ‘helping verbs‘. This category includes to be, to do and to have. These three verbs are very important. ‘Be‘ is used in forming the ‘continuous aspect‘ — I am flying to France tomorrow.’ It is also used to form the ‘passive‘ — ‘I was arrested.’ ‘Do‘ is used in forming questions and for emphasis. ‘Have‘ is used to form the ‘perfect aspect‘ — ‘I have been here before.’ More about these later, when we look at the English tense system.

Also included in the category auxiliary verbs are nine very special verbs, which form a sub-category of their own called ‘modal auxiliary verbs‘ or ‘modal verbs‘ for short. This sub-category comprises the verbs can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would and must. These nine verbs share some important characteristics:

- They can never be followed by ‘to‘: ‘I must to go.’ is a badly formed sentence in English.

- They cannot co-occur in the same verb phrase: ‘You must can go’ is also unacceptable.

- They have no ‘third person‘ inflection: ‘She likes reading.’ is fine, but ‘ She cans swim.’ is not.

In a verb phrase they always occupy the first position — ‘It must have been my aunt.’ Likewise, they do not have three forms.

So what exactly do these ‘modal verbs‘ do? An interesting question! The following table should give you some idea.

Modal verbs are used to express:

|

Degrees of certainty |

Certainty (positive/negative) |

We shall/shan’t come. |

|

Probability/Possibility |

She should arrive at about midday. |

|

|

Weak probability |

She might call — you never know! |

|

|

Theoretical/habitual possibility |

You may have a problem |

|

|

Conditional certainty/possibility |

If you had asked me, I would |

|

|

Obligation |

Strong obligation |

All employees must clock in and out. |

|

Prohibition |

Staff must not make personal calls. |

|

|

Weak obligation/recommendation |

When shall we leave? |

|

|

Willingness/Offering |

Can I help you? |

|

|

Permission |

Might I ask a favour? |

|

|

Ability |

Can you swim? |

|

|

Other uses |

Habitual behaviour |

When I was a boy, I would often go skiing. |

|

Irritation |

Must you do that? |

|

|

Requests |

Would you open the window please? |

Some linguists include verbs such as dare, need and ought in the modal verb sub-category. There is some justification for this, as they display the relevant characteristics some of the time. However, since they do not do so all the time it is better to leave them out of this group.

Back to Top

Adverbs

Adverbs describe or add to the meaning of verbs, prepositions, adjectives, other adverbs and even sentences. They answer questions such as ‘How’, ‘Where’ or ‘When’. Many, but by no means all, adverbs are made from adjectives by simply adding the suffix ‘ly’.

Types of adverb:

|

Adverbs of manner |

carefully, gently, quickly, willingly (She kissed him gently on the forehead.) |

|

Adverbs of place |

here, there, between, externally (He lived between a pub and a noisy factory.) |