«Researched» redirects here. For the organisation, see ResearchED.

Basrelief sculpture «Research holding the torch of knowledge» (1896) by Olin Levi Warner. Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building, in Washington, D.C.

Research is «creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge».[1] It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness to controlling sources of bias and error. These activities are characterized by accounting and controlling for biases. A research project may be an expansion on past work in the field. To test the validity of instruments, procedures, or experiments, research may replicate elements of prior projects or the project as a whole.

The primary purposes of basic research (as opposed to applied research) are documentation, discovery, interpretation, and the research and development (R&D) of methods and systems for the advancement of human knowledge. Approaches to research depend on epistemologies, which vary considerably both within and between humanities and sciences. There are several forms of research: scientific, humanities, artistic, economic, social, business, marketing, practitioner research, life, technological, etc. The scientific study of research practices is known as meta-research.

A researcher is a person engaged in conducting research, possibly recognized as an occupation by a formal job title. Researchers are either Social Scientist or Natural Science Scientist. In order to be social researcher or social scientist, one should have enormous knowledge of subject related to social science that they are specialized in. Similarly, in order to be natural science researcher, the person should have knowledge on field related to natural science (Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Astronomy, Zoology and so on).

Etymology[edit]

The word research is derived from the Middle French «recherche«, which means «to go about seeking», the term itself being derived from the Old French term «recerchier» a compound word from «re-» + «cerchier», or «sercher», meaning ‘search’.[3] The earliest recorded use of the term was in 1577.[3]

Definitions[edit]

Research has been defined in a number of different ways, and while there are similarities, there does not appear to be a single, all-encompassing definition that is embraced by all who engage in it.

Research in simplest terms is searching for knowledge and searching for truth. In a formal sense, it is a systematic study of a problem attacked by a deliberately chosen strategy which starts with choosing an approach to preparing a blueprint (design) and acting upon it in terms of designing research hypotheses, choosing methods and techniques, selecting or developing data collection tools, processing the data, interpretation and ends with presenting solution/s of the problem.[4]

Another definition of research is given by John W. Creswell, who states that «research is a process of steps used to collect and analyze information to increase our understanding of a topic or issue». It consists of three steps: pose a question, collect data to answer the question, and present an answer to the question.[5]

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines research in more detail as «studious inquiry or examination; especially: investigation or experimentation aimed at the discovery and interpretation of facts, revision of accepted theories or laws in the light of new facts, or practical application of such new or revised theories or laws»[3]

Forms of research[edit]

Original research[edit]

«Original research» redirects here. For the Wikipedia prohibition against user-generated, unpublished research, see Wikipedia:No original research.

Original research, also called primary research, is research that is not exclusively based on a summary, review, or synthesis of earlier publications on the subject of research. This material is of a primary-source character. The purpose of the original research is to produce new knowledge, rather than to present the existing knowledge in a new form (e.g., summarized or classified).[6][7] Original research can be in various forms, depending on the discipline it pertains to. In experimental work, it typically involves direct or indirect observation of the researched subject(s), e.g., in the laboratory or in the field, documents the methodology, results, and conclusions of an experiment or set of experiments, or offers a novel interpretation of previous results. In analytical work, there are typically some new (for example) mathematical results produced, or a new way of approaching an existing problem. In some subjects which do not typically carry out experimentation or analysis of this kind, the originality is in the particular way existing understanding is changed or re-interpreted based on the outcome of the work of the researcher.[8]

The degree of originality of the research is among major criteria for articles to be published in academic journals and usually established by means of peer review.[9] Graduate students are commonly required to perform original research as part of a dissertation.[10]

Scientific research[edit]

Scientific research equipment at MIT

Scientific research is a systematic way of gathering data and harnessing curiosity. This research provides scientific information and theories for the explanation of the nature and the properties of the world. It makes practical applications possible. Scientific research is funded by public authorities, by charitable organizations and by private groups, including many companies. Scientific research can be subdivided into different classifications according to their academic and application disciplines. Scientific research is a widely used criterion for judging the standing of an academic institution, but some argue that such is an inaccurate assessment of the institution, because the quality of research does not tell about the quality of teaching (these do not necessarily correlate).[11]

Generally, research is understood to follow a certain structural process. Though step order may vary depending on the subject matter and researcher, the following steps are usually part of most formal research, both basic and applied:

- Observations and formation of the topic: Consists of the subject area of one’s interest and following that subject area to conduct subject-related research. The subject area should not be randomly chosen since it requires reading a vast amount of literature on the topic to determine the gap in the literature the researcher intends to narrow. A keen interest in the chosen subject area is advisable. The research will have to be justified by linking its importance to already existing knowledge about the topic.

- Hypothesis: A testable prediction which designates the relationship between two or more variables.

- Conceptual definition: Description of a concept by relating it to other concepts.

- Operational definition: Details in regards to defining the variables and how they will be measured/assessed in the study.

- Gathering of data: Consists of identifying a population and selecting samples, gathering information from or about these samples by using specific research instruments. The instruments used for data collection must be valid and reliable.

- Analysis of data: Involves breaking down the individual pieces of data to draw conclusions about it.

- Data Interpretation: This can be represented through tables, figures, and pictures, and then described in words.

- Test, revising of hypothesis

- Conclusion, reiteration if necessary

A common misconception is that a hypothesis will be proven (see, rather, null hypothesis). Generally, a hypothesis is used to make predictions that can be tested by observing the outcome of an experiment. If the outcome is inconsistent with the hypothesis, then the hypothesis is rejected (see falsifiability). However, if the outcome is consistent with the hypothesis, the experiment is said to support the hypothesis. This careful language is used because researchers recognize that alternative hypotheses may also be consistent with the observations. In this sense, a hypothesis can never be proven, but rather only supported by surviving rounds of scientific testing and, eventually, becoming widely thought of as true.

A useful hypothesis allows prediction and within the accuracy of observation of the time, the prediction will be verified. As the accuracy of observation improves with time, the hypothesis may no longer provide an accurate prediction. In this case, a new hypothesis will arise to challenge the old, and to the extent that the new hypothesis makes more accurate predictions than the old, the new will supplant it. Researchers can also use a null hypothesis, which states no relationship or difference between the independent or dependent variables.

Research in the humanities[edit]

Research in the humanities involves different methods such as for example hermeneutics and semiotics. Humanities scholars usually do not search for the ultimate correct answer to a question, but instead, explore the issues and details that surround it. Context is always important, and context can be social, historical, political, cultural, or ethnic. An example of research in the humanities is historical research, which is embodied in historical method. Historians use primary sources and other evidence to systematically investigate a topic, and then to write histories in the form of accounts of the past. Other studies aim to merely examine the occurrence of behaviours in societies and communities, without particularly looking for reasons or motivations to explain these. These studies may be qualitative or quantitative, and can use a variety of approaches, such as queer theory or feminist theory.[12]

Artistic research[edit]

Artistic research, also seen as ‘practice-based research’, can take form when creative works are considered both the research and the object of research itself. It is the debatable body of thought which offers an alternative to purely scientific methods in research in its search for knowledge and truth.

The controversial trend of artistic teaching becoming more academics-oriented is leading to artistic research being accepted as the primary mode of enquiry in art as in the case of other disciplines.[13] One of the characteristics of artistic research is that it must accept subjectivity as opposed to the classical scientific methods. As such, it is similar to the social sciences in using qualitative research and intersubjectivity as tools to apply measurement and critical analysis.[14]

Artistic research has been defined by the School of Dance and Circus (Dans och Cirkushögskolan, DOCH), Stockholm in the following manner – «Artistic research is to investigate and test with the purpose of gaining knowledge within and for our artistic disciplines. It is based on artistic practices, methods, and criticality. Through presented documentation, the insights gained shall be placed in a context.»[15] Artistic research aims to enhance knowledge and understanding with presentation of the arts.[16] A simpler understanding by Julian Klein defines artistic research as any kind of research employing the artistic mode of perception.[17] For a survey of the central problematics of today’s artistic research, see Giaco Schiesser.[18]

According to artist Hakan Topal, in artistic research, «perhaps more so than other disciplines, intuition is utilized as a method to identify a wide range of new and unexpected productive modalities».[19] Most writers, whether of fiction or non-fiction books, also have to do research to support their creative work. This may be factual, historical, or background research. Background research could include, for example, geographical or procedural research.[20]

The Society for Artistic Research (SAR) publishes the triannual Journal for Artistic Research (JAR),[21][22] an international, online, open access, and peer-reviewed journal for the identification, publication, and dissemination of artistic research and its methodologies, from all arts disciplines and it runs the Research Catalogue (RC),[23][24][25] a searchable, documentary database of artistic research, to which anyone can contribute.

Patricia Leavy addresses eight arts-based research (ABR) genres: narrative inquiry, fiction-based research, poetry, music, dance, theatre, film, and visual art.[26]

In 2016, the European League of Institutes of the Arts launched The Florence Principles’ on the Doctorate in the Arts.[27] The Florence Principles relating to the Salzburg Principles and the Salzburg Recommendations of the European University Association name seven points of attention to specify the Doctorate / PhD in the Arts compared to a scientific doctorate / PhD. The Florence Principles have been endorsed and are supported also by AEC, CILECT, CUMULUS and SAR.

Historical research[edit]

German historian Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886), considered to be one of the founders of modern source-based history

The historical method comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historians use historical sources and other evidence to research and then to write history. There are various history guidelines that are commonly used by historians in their work, under the headings of external criticism, internal criticism, and synthesis. This includes lower criticism and sensual criticism. Though items may vary depending on the subject matter and researcher, the following concepts are part of most formal historical research:[28]

- Identification of origin date

- Evidence of localization

- Recognition of authorship

- Analysis of data

- Identification of integrity

- Attribution of credibility

Documentary research[edit]

Steps in conducting research[edit]

Research design and evidence

Research is often conducted using the hourglass model structure of research.[29] The hourglass model starts with a broad spectrum for research, focusing in on the required information through the method of the project (like the neck of the hourglass), then expands the research in the form of discussion and results. The major steps in conducting research are:[30]

- Identification of research problem

- Literature review

- Specifying the purpose of research

- Determining specific research questions

- Specification of a conceptual framework, sometimes including a set of hypotheses[31]

- Choice of a methodology (for data collection)

- Data collection

- Verifying data

- Analyzing and interpreting the data

- Reporting and evaluating research

- Communicating the research findings and, possibly, recommendations

The steps generally represent the overall process; however, they should be viewed as an ever-changing iterative process rather than a fixed set of steps.[32] Most research begins with a general statement of the problem, or rather, the purpose for engaging in the study.[33] The literature review identifies flaws or holes in previous research which provides justification for the study. Often, a literature review is conducted in a given subject area before a research question is identified. A gap in the current literature, as identified by a researcher, then engenders a research question. The research question may be parallel to the hypothesis. The hypothesis is the supposition to be tested. The researcher(s) collects data to test the hypothesis. The researcher(s) then analyzes and interprets the data via a variety of statistical methods, engaging in what is known as empirical research. The results of the data analysis in rejecting or failing to reject the null hypothesis are then reported and evaluated. At the end, the researcher may discuss avenues for further research. However, some researchers advocate for the reverse approach: starting with articulating findings and discussion of them, moving «up» to identification of a research problem that emerges in the findings and literature review. The reverse approach is justified by the transactional nature of the research endeavor where research inquiry, research questions, research method, relevant research literature, and so on are not fully known until the findings have fully emerged and been interpreted.

Rudolph Rummel says, «… no researcher should accept any one or two tests as definitive. It is only when a range of tests are consistent over many kinds of data, researchers, and methods can one have confidence in the results.»[34]

Plato in Meno talks about an inherent difficulty, if not a paradox, of doing research that can be paraphrased in the following way, «If you know what you’re searching for, why do you search for it?! [i.e., you have already found it] If you don’t know what you’re searching for, what are you searching for?!»[35]

Research methods[edit]

The research room at the New York Public Library, an example of secondary research in progress

The goal of the research process is to produce new knowledge or deepen understanding of a topic or issue. This process takes three main forms (although, as previously discussed, the boundaries between them may be obscure):

- Exploratory research, which helps to identify and define a problem or question.

- Constructive research, which tests theories and proposes solutions to a problem or question.

- Empirical research, which tests the feasibility of a solution using empirical evidence.

There are two major types of empirical research design: qualitative research and quantitative research. Researchers choose qualitative or quantitative methods according to the nature of the research topic they want to investigate and the research questions they aim to answer:

- Qualitative research

Qualitative research refers to much more subjective non- quantitative, use different methods of collecting data, analyzing data, interpreting data for meanings, definitions, characteristics, symbols metaphors of things.Qualitative research further classified into following types: Ethnography: This research mainly focus on culture of group of people which includes share attributes, language, practices, structure, value, norms and material things, evaluate human lifestyle. Ethno: people, Grapho: to write, this disciple may include ethnic groups, ethno genesis, composition, resettlement and social welfare characteristics. Phenomenology: It is very powerful strategy for demonstrating methodology to health professions education as well as best suited for exploring challenging problems in health professions educations.[37]

- Quantitative research

- This involves systematic empirical investigation of quantitative properties and phenomena and their relationships, by asking a narrow question and collecting numerical data to analyze it utilizing statistical methods. The quantitative research designs are experimental, correlational, and survey (or descriptive).[38] Statistics derived from quantitative research can be used to establish the existence of associative or causal relationships between variables. Quantitative research is linked with the philosophical and theoretical stance of positivism.

The quantitative data collection methods rely on random sampling and structured data collection instruments that fit diverse experiences into predetermined response categories.[citation needed] These methods produce results that can be summarized, compared, and generalized to larger populations if the data are collected using proper sampling and data collection strategies.[39] Quantitative research is concerned with testing hypotheses derived from theory or being able to estimate the size of a phenomenon of interest.[39]

If the research question is about people, participants may be randomly assigned to different treatments (this is the only way that a quantitative study can be considered a true experiment).[citation needed] If this is not feasible, the researcher may collect data on participant and situational characteristics to statistically control for their influence on the dependent, or outcome, variable. If the intent is to generalize from the research participants to a larger population, the researcher will employ probability sampling to select participants.[40]

In either qualitative or quantitative research, the researcher(s) may collect primary or secondary data.[39] Primary data is data collected specifically for the research, such as through interviews or questionnaires. Secondary data is data that already exists, such as census data, which can be re-used for the research. It is good ethical research practice to use secondary data wherever possible.[41]

Mixed-method research, i.e. research that includes qualitative and quantitative elements, using both primary and secondary data, is becoming more common.[42] This method has benefits that using one method alone cannot offer. For example, a researcher may choose to conduct a qualitative study and follow it up with a quantitative study to gain additional insights.[43]

Big data has brought big impacts on research methods so that now many researchers do not put much effort into data collection; furthermore, methods to analyze easily available huge amounts of data have also been developed.

Types of Research Method

1. Observatory Research Method

2. Correlation Research Method [44]

- Non-empirical research

Non-empirical (theoretical) research is an approach that involves the development of theory as opposed to using observation and experimentation. As such, non-empirical research seeks solutions to problems using existing knowledge as its source. This, however, does not mean that new ideas and innovations cannot be found within the pool of existing and established knowledge. Non-empirical research is not an absolute alternative to empirical research because they may be used together to strengthen a research approach. Neither one is less effective than the other since they have their particular purpose in science. Typically empirical research produces observations that need to be explained; then theoretical research tries to explain them, and in so doing generates empirically testable hypotheses; these hypotheses are then tested empirically, giving more observations that may need further explanation; and so on. See Scientific method.

A simple example of a non-empirical task is the prototyping of a new drug using a differentiated application of existing knowledge; another is the development of a business process in the form of a flow chart and texts where all the ingredients are from established knowledge. Much of cosmological research is theoretical in nature. Mathematics research does not rely on externally available data; rather, it seeks to prove theorems about mathematical objects.

Research ethics[edit]

Research ethics is concerned with the moral issues that arise during or as a result of research activities, as well as the conduct of individual researchers, and the implications for research communities.[45] Historically, scandals such as Nazi human experimentation and the Tuskegee syphilis experiment led to the realisation that clear measures are needed for the ethical governance of research to ensure that people, animals and environments are not unduly harmed by scientific inquiry. The management of research ethics is inconsistent across countries and there is no universally accepted approach to how it should be addressed.[46][47][48] Research ethics committees (Institutional review board in the US) have emerged as one governance mechanism to ensure research is conducted responsibly.

When making moral judgments, we may be guided by different values. Philosophers commonly distinguish between approaches like deontology, consequentialism, Confucianism, virtue ethics, and Ubuntu ethics, to list a few. Regardless of approach, the application of ethical theory to specific contexts is known as applied ethics, and research ethics can be viewed as a subfield of applied ethics because ethical theory is applied in real-world research scenarios.

Ethical issues may arise in the design and implementation of research involving human experimentation or animal experimentation. There may also be consequences for the environment, for society or for future generations that need to be considered. Research ethics is most developed as a concept in medical research, with typically cited codes being the 1947 Nuremberg Code, the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and the 1978 Belmont Report. Informed consent is a key concept in research ethics thanks to these codes. Research in other fields such as social sciences, information technology, biotechnology, or engineering may generate different types of ethical concerns to those in medical research.[46][47][49][50][51][52]

In countries such as Canada, mandatory research ethics training is required for students, professors and others who work in research,[53][54] whilst the US has legislated on how institutional review boards operate since the 1974 National Research Act.

Research ethics is commonly distinguished from the promotion of academic or research integrity, which includes issues such as scientific misconduct (e.g. fraud, fabrication of data or plagiarism). Because of the close interaction with integrity, increasingly research ethics is included as part of the broader field of responsible conduct of research (RCR in North America) or Responsible Research and Innovation in Europe, and with government agencies such as the United States Office of Research Integrity or the Canadian Interagency Advisory Panel on Responsible Conduct of Research promoting or requiring interdisciplinary training for researchers.

Problems in research[edit]

Meta-research[edit]

Meta-research is the study of research through the use of research methods. Also known as «research on research», it aims to reduce waste and increase the quality of research in all fields. Meta-research concerns itself with the detection of bias, methodological flaws, and other errors and inefficiencies. Among the finding of meta-research is a low rates of reproducibility across a large number of fields. This widespread difficulty in reproducing research has been termed the «replication crisis.»[55]

Methods of research[edit]

In many disciplines, Western methods of conducting research are predominant.[56] Researchers are overwhelmingly taught Western methods of data collection and study. The increasing participation of indigenous peoples as researchers has brought increased attention to the scientific lacuna in culturally sensitive methods of data collection.[57] Western methods of data collection may not be the most accurate or relevant for research on non-Western societies. For example, «Hua Oranga» was created as a criterion for psychological evaluation in Māori populations, and is based on dimensions of mental health important to the Māori people – «taha wairua (the spiritual dimension), taha hinengaro (the mental dimension), taha tinana (the physical dimension), and taha whanau (the family dimension)».[58]

Bias[edit]

Research is often biased in the languages that are preferred (linguicism) and the geographic locations where research occurs.

Periphery scholars face the challenges of exclusion and linguicism in research and academic publication. As the great majority of mainstream academic journals are written in English, multilingual periphery scholars often must translate their work to be accepted to elite Western-dominated journals.[59] Multilingual scholars’ influences from their native communicative styles can be assumed to be incompetence instead of difference.[60]

For comparative politics, Western countries are over-represented in single-country studies, with heavy emphasis on Western Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Since 2000, Latin American countries have become more popular in single-country studies. In contrast, countries in Oceania and the Caribbean are the focus of very few studies. Patterns of geographic bias also show a relationship with linguicism: countries whose official languages are French or Arabic are far less likely to be the focus of single-country studies than countries with different official languages. Within Africa, English-speaking countries are more represented than other countries.[61]

Generalizability[edit]

Generalization is the process of more broadly applying the valid results of one study.[62] Studies with a narrow scope can result in a lack of generalizability, meaning that the results may not be applicable to other populations or regions. In comparative politics, this can result from using a single-country study, rather than a study design that uses data from multiple countries. Despite the issue of generalizability, single-country studies have risen in prevalence since the late 2000s.[61]

Publication peer review[edit]

|

|

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: This subsection’s claims are potentially outdated in the «digital age» given that near-total penetration of Web access among scholars worldwide enables any scholar[s] to submit papers to any journal anywhere. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (May 2017) |

Peer review is a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field. Peer review methods are employed to maintain standards of quality, improve performance, and provide credibility. In academia, scholarly peer review is often used to determine an academic paper’s suitability for publication. Usually, the peer review process involves experts in the same field who are consulted by editors to give a review of the scholarly works produced by a colleague of theirs from an unbiased and impartial point of view, and this is usually done free of charge. The tradition of peer reviews being done for free has however brought many pitfalls which are also indicative of why most peer reviewers decline many invitations to review.[63] It was observed that publications from periphery countries rarely rise to the same elite status as those of North America and Europe, because limitations on the availability of resources including high-quality paper and sophisticated image-rendering software and printing tools render these publications less able to satisfy standards currently carrying formal or informal authority in the publishing industry.[60] These limitations in turn result in the under-representation of scholars from periphery nations among the set of publications holding prestige status relative to the quantity and quality of those scholars’ research efforts, and this under-representation in turn results in disproportionately reduced acceptance of the results of their efforts as contributions to the body of knowledge available worldwide.

Influence of the open-access movement[edit]

The open access movement assumes that all information generally deemed useful should be free and belongs to a «public domain», that of «humanity».[64] This idea gained prevalence as a result of Western colonial history and ignores alternative conceptions of knowledge circulation. For instance, most indigenous communities consider that access to certain information proper to the group should be determined by relationships.[64]

There is alleged to be a double standard in the Western knowledge system. On the one hand, «digital right management» used to restrict access to personal information on social networking platforms is celebrated as a protection of privacy, while simultaneously when similar functions are used by cultural groups (i.e. indigenous communities) this is denounced as «access control» and reprehended as censorship.[64]

Future perspectives[edit]

Even though Western dominance seems to be prominent in research, some scholars, such as Simon Marginson, argue for «the need [for] a plural university world».[65] Marginson argues that the East Asian Confucian model could take over the Western model.

This could be due to changes in funding for research both in the East and the West. Focused on emphasizing educational achievement, East Asian cultures, mainly in China and South Korea, have encouraged the increase of funding for research expansion.[65] In contrast, in the Western academic world, notably in the United Kingdom as well as in some state governments in the United States, funding cuts for university research have occurred, which some[who?] say may lead to the future decline of Western dominance in research.

Neo-colonial approaches[edit]

Neo-colonial research or neo-colonial science,[66][67] frequently described as helicopter research,[66] parachute science[68][69] or research,[70] parasitic research,[71][72] or safari study,[73] is when researchers from wealthier countries go to a developing country, collect information, travel back to their country, analyze the data and samples, and publish the results with no or little involvement of local researchers. A 2003 study by the Hungarian academy of sciences found that 70% of articles in a random sample of publications about least-developed countries did not include a local research co-author.[67]

Frequently, during this kind of research, the local colleagues might be used to provide logistics support as fixers but are not engaged for their expertise or given credit for their participation in the research. Scientific publications resulting from parachute science frequently only contribute to the career of the scientists from rich countries, thus limiting the development of local science capacity (such as funded research centers) and the careers of local scientists.[66] This form of «colonial» science has reverberations of 19th century scientific practices of treating non-Western participants as «others» in order to advance colonialism—and critics call for the end of these extractivist practices in order to decolonize knowledge.[74][75]

This kind of research approach reduces the quality of research because international researchers may not ask the right questions or draw connections to local issues.[76] The result of this approach is that local communities are unable to leverage the research to their own advantage.[69] Ultimately, especially for fields dealing with global issues like conservation biology which rely on local communities to implement solutions, neo-colonial science prevents institutionalization of the findings in local communities in order to address issues being studied by scientists.[69][74]

Professionalisation [edit]

In several national and private academic systems, the professionalisation of research has resulted in formal job titles.

In Russia[edit]

In present-day Russia, and some other countries of the former Soviet Union, the term researcher (Russian: Научный сотрудник, nauchny sotrudnik) has been used both as a generic term for a person who has been carrying out scientific research, and as a job position within the frameworks of the Academy of Sciences, universities, and in other research-oriented establishments.

The following ranks are known:

- Junior Researcher (Junior Research Associate)

- Researcher (Research Associate)

- Senior Researcher (Senior Research Associate)

- Leading Researcher (Leading Research Associate)[77]

- Chief Researcher (Chief Research Associate)

Publishing[edit]

Cover of the first issue of Nature, 4 November 1869

Academic publishing is a system that is necessary for academic scholars to peer review the work and make it available for a wider audience. The system varies widely by field and is also always changing, if often slowly. Most academic work is published in journal article or book form. There is also a large body of research that exists in either a thesis or dissertation form. These forms of research can be found in databases explicitly for theses and dissertations. In publishing, STM publishing is an abbreviation for academic publications in science, technology, and medicine.

Most established academic fields have their own scientific journals and other outlets for publication, though many academic journals are somewhat interdisciplinary, and publish work from several distinct fields or subfields. The kinds of publications that are accepted as contributions of knowledge or research vary greatly between fields, from the print to the electronic format. A study suggests that researchers should not give great consideration to findings that are not replicated frequently.[78] It has also been suggested that all published studies should be subjected to some measure for assessing the validity or reliability of its procedures to prevent the publication of unproven findings.[79] Business models are different in the electronic environment. Since about the early 1990s, licensing of electronic resources, particularly journals, has been very common. Presently, a major trend, particularly with respect to scholarly journals, is open access.[80] There are two main forms of open access: open access publishing, in which the articles or the whole journal is freely available from the time of publication, and self-archiving, where the author makes a copy of their own work freely available on the web.

Research funding[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: funding for research in the humanities and other areas. |

Most funding for scientific research comes from three major sources: corporate research and development departments; private foundations; and government research councils such as the National Institutes of Health in the USA[81] and the Medical Research Council in the UK. These are managed primarily through universities and in some cases through military contractors. Many senior researchers (such as group leaders) spend a significant amount of their time applying for grants for research funds. These grants are necessary not only for researchers to carry out their research but also as a source of merit. The Social Psychology Network provides a comprehensive list of U.S. Government and private foundation funding sources.

See also[edit]

- Advertising research

- European Charter for Researchers

- Funding bias

- Internet research

- Laboratory

- List of countries by research and development spending

- List of words ending in ology

- Market research

- Marketing research

- Open research

- Operations research

- Participatory action research

- Psychological research methods

- Research integrity

- Research-intensive cluster

- Research organization

- Research proposal

- Research university

- Scholarly research

- Secondary research

- Social research

- Society for Artistic Research

- Timeline of the history of the scientific method

- Undergraduate research

References[edit]

- ^ OECD (2015). Frascati Manual. The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities. doi:10.1787/9789264239012-en. hdl:20.500.12749/13290. ISBN 978-9264238800.

- ^ «The Origins of Science Archived 3 March 2003 at the Wayback Machine». Scientific American Frontiers.

- ^ a b c «Research». Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Grover, Vijey (2015). «RESEARCH APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW». Golden Research Thoughts. 4.

- ^ Creswell, J.W. (2008). Educational Research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ «What is Original Research? Original research is considered a primary source». Thomas G. Carpenter Library, University of North Florida. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Rozakis, Laurie (2007). Schaum’s Quick Guide to Writing Great Research Papers. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0071511223 – via Google Books.

- ^ Singh, Michael; Li, Bingyi (6 October 2009). «Early career researcher originality: Engaging Richard Florida’s international competition for creative workers» (PDF). Centre for Educational Research, University of Western Sydney. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Callaham, Michael; Wears, Robert; Weber, Ellen L. (2002). «Journal Prestige, Publication Bias, and Other Characteristics Associated With Citation of Published Studies in Peer-Reviewed Journals». JAMA. 287 (21): 2847–50. doi:10.1001/jama.287.21.2847. PMID 12038930.

- ^ US Department of Labor (2006). Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2006–2007 edition. Mcgraw-hill. ISBN 978-0071472883 – via Google Books.

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong & Tad Sperry (1994). «Business School Prestige: Research versus Teaching» (PDF). Energy & Environment. 18 (2): 13–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Roffee, James A; Waling, Andrea (18 August 2016). «Resolving ethical challenges when researching with minority and vulnerable populations: LGBTIQ victims of violence, harassment and bullying». Research Ethics. 13 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1177/1747016116658693.

- ^ Lesage, Dieter (Spring 2009). «Who’s Afraid of Artistic Research? On measuring artistic research output» (PDF). Art & Research. 2 (2). ISSN 1752-6388. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Eisner, E. W. (1981). «On the Differences between Scientific and Artistic Approaches to Qualitative Research». Educational Researcher. 10 (4): 5–9. doi:10.2307/1175121. JSTOR 1175121.

- ^ Unattributed. «Artistic research at DOCH». Dans och Cirkushögskolan (website). Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Schwab, M. (2009). «Draft Proposal». Journal for Artistic Research. Bern University of the Arts.

- ^ Julian Klein (2010). «What is artistic research?».

- ^ Schiesser, G. (2015). What is at stake – Qu’est ce que l’enjeu? Paradoxes – Problematics – Perspectives in Artistic Research Today, in: Arts, Research, Innovation and Society. Eds. Gerald Bast, Elias G. Carayannis [= ARIS, Vol. 1]. Wien/New York: Springer. pp. 197–210.

- ^ Topal, H. (2014). «Whose Terms? A Glossary for Social Practice: Research». newmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014.

- ^ Hoffman, A. (2003). Research for Writers, pp. 4–5. London: A&C Black Publishers Limited.

- ^ «Swiss Science and Technology Research Council (2011), Research Funding in the Arts» (PDF).

- ^ Henk Borgdorff (2012), The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia (Chapter 11: The Case of the Journal for Artistic Research), Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- ^ Schwab, Michael, and Borgdorff, Henk, eds. (2014), The Exposition of Artistic Research: Publishing Art in Academia, Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- ^ Wilson, Nick and van Ruiten, Schelte / ELIA, eds. (2013), SHARE Handbook for Artistic Research Education, Amsterdam: Valand Academy, p. 249.

- ^ Hughes, Rolf: «Leap into Another Kind: International Developments in Artistic Research,» in Swedish Research Council, ed. (2013), Artistic Research Then and Now: 2004–2013, Yearbook of AR&D 2013, Stockholm: Swedish Research Council.

- ^ Leavy, Patricia (2015). Methods Meets Art (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford. ISBN 978-1462519446.

- ^ Rahmat, Omarkhil. «Florence principles, 2016» (PDF).

- ^ Garraghan, Gilbert J. (1946). A Guide to Historical Method. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8371-7132-6.

- ^ Trochim, W.M.K, (2006). Research Methods Knowledge Base.

- ^ Creswell, J.W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 2008 ISBN 0-13-613550-1 (pages 8–9)

- ^ Shields, Patricia M.; Rangarjan, N. (2013). A Playbook for Research Methods: Integrating Conceptual Frameworks and Project Management. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press. ISBN 9781581072471.

- ^ Gauch, Jr., H.G. (2003). Scientific method in practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2003 ISBN 0-521-81689-0 (page 3)

- ^ Rocco, T.S., Hatcher, T., & Creswell, J.W. (2011). The handbook of scholarly writing and publishing. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons. 2011 ISBN 978-0-470-39335-2

- ^ «QUESTIONS ABOUT FREEDOM, DEMOCIDE, AND WAR». www.hawaii.edu.

- ^ Plato, & Bluck, R. S. (1962). Meno. Cambridge, UK: University Press.

- ^ Sullivan P (13 April 2005). «Maurice R. Hilleman dies; created vaccines». The Washington Post.

- ^ Pawar, Neelam (December 2020). «6. Type of Research and Type Research Design». Research Methodology: An Overview. Vol. 15. KD Publications. pp. 46–57. ISBN 978-81-948755-8-1.

- ^ Creswell, J.W. (2008). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- ^ a b c Eyler, Amy A., PhD, CHES. (2020). Research Methods for Public Health. New York: Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8261-8206-7. OCLC 1202451096.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Data Collection Methods». uwec.edu.

- ^ Kara H. (2012). Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners: A Time-Saving Guide, p. 102. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- ^ Kara H (2012). Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners: A Time-Saving Guide, p. 114. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- ^ Creswell, John W. (2014). Research design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage. ISBN 978-1-4522-2609-5.

- ^ Liu, Alex (2015). «Structural Equation Modeling and Latent Variable Approaches». Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0325. ISBN 978-1118900772.

- ^ Douglas, Heather (2014). «The Moral Terrain of Science». Erkenntnis. 79 (S5): 961–979. doi:10.1007/s10670-013-9538-0. ISSN 0165-0106. S2CID 144445475.

- ^ a b Israel, M. G., & Thomson, A. C. (27–29 November 2013). The rise and much-sought demise of the adversarial culture in Australian research ethics. Paper presented at the 2013 Australasian Ethics Network Conference, Perth, Australia.

- ^ a b Israel, M. (2016). Research ethics and integrity for social scientists: Beyond regulatory compliance (Second ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- ^ Eaton, Sarah Elaine (2020). «Ethical considerations for research conducted with human participants in languages other than English». British Educational Research Journal. 46 (4): 848–858. doi:10.1002/berj.3623. ISSN 0141-1926. S2CID 216445727.

- ^ Stahl, B. C., Timmermans, J., & Flick, C. (2017). «Ethics of Emerging Information and Communication Technologies On the implementation of responsible research and innovation». Science and Public Policy, 44(3), 369–381.

- ^ Iphofen, R. (2016). Ethical decision making in social research: A practical guide. Springer.

- ^ Wickson, F., Preston, C., Binimelis, R., Herrero, A., Hartley, S., Wynberg, R., & Wynne, B. (2017). «Addressing socio-economic and ethical considerations in biotechnology governance: The potential of a new politics of care». Food ethics, 1(2), 193–199.

- ^ Whitbeck, C. (2011). Ethics in engineering practice and research. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Government of Canada. (n.d.). Panel on Research Ethics: The TCPS2 Tutorial Course on Research Ethics (CORE). Retrieved from http://pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/education/tutorial-didacticiel/

- ^ Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. (2018). Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans: TCPS2 2018. Retrieved from http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/documents/tcps2-2018-en-interactive-final.pdf

- ^ Ioannidis, John P. A.; Fanelli, Daniele; Dunne, Debbie Drake; Goodman, Steven N. (2 October 2015). «Meta-research: Evaluation and Improvement of Research Methods and Practices». PLOS Biology. 13 (10): –1002264. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002264. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4592065. PMID 26431313.

- ^ Reverby, Susan M. (1 April 2012). «Zachary M. Schrag. Ethical Imperialism: Institutional Review Boards and the Social Sciences, 1965–2009. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2010. Pp. xii, 245. $45.00». The American Historical Review. 117 (2): 484–485. doi:10.1086/ahr.117.2.484-a. ISSN 0002-8762.

- ^ Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (2nd ed.). London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1848139503.

- ^ Stewart, Lisa (2012). «Commentary on Cultural Diversity Across the Pacific: The Dominance of Western Theories, Models, Research and Practice in Psychology». Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 6 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1017/prp.2012.1.

- ^ Canagarajah, A. Suresh (1 January 1996). «From Critical Research Practice to Critical Research Reporting». TESOL Quarterly. 30 (2): 321–331. doi:10.2307/3588146. JSTOR 3588146.

- ^ a b Canagarajah, Suresh (October 1996). «‘Nondiscursive’ Requirements in Academic Publishing, Material Resources of Periphery Scholars, and the Politics of Knowledge Production». Written Communication. 13 (4): 435–472. doi:10.1177/0741088396013004001. S2CID 145250687.

- ^ a b Pepinsky, Thomas B. (2019). «The Return of the Single-Country Study». Annual Review of Political Science. 22: 187–203. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051017-113314.

- ^ Kukull, W. A.; Ganguli, M. (2012). «Generalizability: The trees, the forest, and the low-hanging fruit». Neurology. 78 (23): 1886–1891. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f812. PMC 3369519. PMID 22665145.

- ^ «Peer Review of Scholarly Journal». www.PeerViewer.com. June 2017.

- ^ a b c Christen, Kimberly (2012). «Does Information Really Want to be Free? Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness». International Journal of Communication. 6.

- ^ a b «Sun sets on Western dominance as East Asian Confucian model takes lead». 24 February 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Minasny, Budiman; Fiantis, Dian; Mulyanto, Budi; Sulaeman, Yiyi; Widyatmanti, Wirastuti (15 August 2020). «Global soil science research collaboration in the 21st century: Time to end helicopter research». Geoderma. 373: 114299. Bibcode:2020Geode.373k4299M. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114299. ISSN 0016-7061.

- ^ a b Dahdouh-Guebas, Farid; Ahimbisibwe, J.; Van Moll, Rita; Koedam, Nico (1 March 2003). «Neo-colonial science by the most industrialised upon the least developed countries in peer-reviewed publishing». Scientometrics. 56 (3): 329–343. doi:10.1023/A:1022374703178. ISSN 1588-2861. S2CID 18463459.

- ^ «Q&A: Parachute Science in Coral Reef Research». The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ a b c «The Problem With ‘Parachute Science’«. Science Friday. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ «Scientists Say It’s Time To End ‘Parachute Research’«. NPR.org. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Health, The Lancet Global (1 June 2018). «Closing the door on parachutes and parasites». The Lancet Global Health. 6 (6): e593. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30239-0. ISSN 2214-109X. PMID 29773111. S2CID 21725769.

- ^ Smith, James (1 August 2018). «Parasitic and parachute research in global health». The Lancet Global Health. 6 (8): e838. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30315-2. ISSN 2214-109X. PMID 30012263. S2CID 51630341.

- ^ «Helicopter Research». TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ a b Vos, Asha de. «The Problem of ‘Colonial Science’«. Scientific American. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ «The Traces of Colonialism in Science». Observatory of Educational Innovation. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Stefanoudis, Paris V.; Licuanan, Wilfredo Y.; Morrison, Tiffany H.; Talma, Sheena; Veitayaki, Joeli; Woodall, Lucy C. (22 February 2021). «Turning the tide of parachute science». Current Biology. 31 (4): R184–R185. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.029. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 33621503.

- ^ «Ведущий научный сотрудник: должностные обязанности». www.aup.ru.

- ^ Heiner Evanschitzky, Carsten Baumgarth, Raymond Hubbard and J. Scott Armstrong (2006). «Replication Research in Marketing Revisited: A Note on a Disturbing Trend» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Scott Armstrong & Peer Soelberg (1968). «On the Interpretation of Factor Analysis» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 70 (5): 361–364. doi:10.1037/h0026434. S2CID 25687243. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong & Robert Fildes (2006). «Monetary Incentives in Mail Surveys» (PDF). International Journal of Forecasting. 22 (3): 433–441. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.04.007. S2CID 154398140. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ «Home | RePORT». report.nih.gov.

Further reading[edit]

- Groh, Arnold (2018). Research Methods in Indigenous Contexts. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-72774-5.

- Cohen, N.; Arieli, T. (2011). «Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling». Journal of Peace Research. 48 (4): 423–436. doi:10.1177/0022343311405698. S2CID 145328311.

- Soeters, Joseph; Shields, Patricia and Rietjens, Sebastiaan. 2014. Handbook of Research Methods in Military Studies New York: Routledge.

- Talja, Sanna and Pamela J. Mckenzie (2007). Editor’s Introduction: Special Issue on Discursive Approaches to Information Seeking in Context, The University of Chicago Press.

External links[edit]

Wikiversity has learning resources about Research

The search for knowledge is closely linked to the object of study; that is, to the reconstruction of the facts that will provide an explanation to an observed event and that at first sight can be considered as a problem. It is very human to seek answers and satisfy our curiosity. Let’s talk about research.

Research is the careful consideration of study regarding a particular concern or research problem using scientific methods. According to the American sociologist Earl Robert Babbie, “research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict, and control the observed phenomenon. It involves inductive and deductive methods.”

Inductive methods analyze an observed event, while deductive methods verify the observed event. Inductive approaches are associated with qualitative research, and deductive methods are more commonly associated with quantitative analysis.

Research is conducted with a purpose to:

- Identify potential and new customers

- Understand existing customers

- Set pragmatic goals

- Develop productive market strategies

- Address business challenges

- Put together a business expansion plan

- Identify new business opportunities

What are the characteristics of research?

- Good research follows a systematic approach to capture accurate data. Researchers need to practice ethics and a code of conduct while making observations or drawing conclusions.

- The analysis is based on logical reasoning and involves both inductive and deductive methods.

- Real-time data and knowledge is derived from actual observations in natural settings.

- There is an in-depth analysis of all data collected so that there are no anomalies associated with it.

- It creates a path for generating new questions. Existing data helps create more research opportunities.

- It is analytical and uses all the available data so that there is no ambiguity in inference.

- Accuracy is one of the most critical aspects of research. The information must be accurate and correct. For example, laboratories provide a controlled environment to collect data. Accuracy is measured in the instruments used, the calibrations of instruments or tools, and the experiment’s final result.

What is the purpose of research?

There are three main purposes:

- Exploratory: As the name suggests, researchers conduct exploratory studies to explore a group of questions. The answers and analytics may not offer a conclusion to the perceived problem. It is undertaken to handle new problem areas that haven’t been explored before. This exploratory process lays the foundation for more conclusive data collection and analysis.

- Descriptive: It focuses on expanding knowledge on current issues through a process of data collection. Descriptive research describe the behavior of a sample population. Only one variable is required to conduct the study. The three primary purposes of descriptive studies are describing, explaining, and validating the findings. For example, a study conducted to know if top-level management leaders in the 21st century possess the moral right to receive a considerable sum of money from the company profit.

- Explanatory: Causal or explanatory research is conducted to understand the impact of specific changes in existing standard procedures. Running experiments is the most popular form. For example, a study that is conducted to understand the effect of rebranding on customer loyalty.

Here is a comparative analysis chart for a better understanding:

| Exploratory Research | Descriptive Research | Explanatory Research | |

| Approach used | Unstructured | Structured | Highly structured |

| Conducted through | Asking questions | Asking questions | By using hypotheses. |

| Time | Early stages of decision making | Later stages of decision making | Later stages of decision making |

It begins by asking the right questions and choosing an appropriate method to investigate the problem. After collecting answers to your questions, you can analyze the findings or observations to draw reasonable conclusions.

When it comes to customers and market studies, the more thorough your questions, the better the analysis. You get essential insights into brand perception and product needs by thoroughly collecting customer data through surveys and questionnaires. You can use this data to make smart decisions about your marketing strategies to position your business effectively.

To make sense of your study and get insights faster, it helps to use a research repository as a single source of truth in your organization and manage your research data in one centralized repository.

Types of research methods and Examples

Research methods are broadly classified as Qualitative and Quantitative.

Both methods have distinctive properties and data collection methods.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative research is a method that collects data using conversational methods, usually open-ended questions. The responses collected are essentially non-numerical. This method helps a researcher understand what participants think and why they think in a particular way.

Types of qualitative methods include:

- One-to-one Interview

- Focus Groups

- Ethnographic studies

- Text Analysis

- Case Study

Quantitative methods

Quantitative methods deal with numbers and measurable forms. It uses a systematic way of investigating events or data. It answers questions to justify relationships with measurable variables to either explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

Types of quantitative methods include:

- Survey research

- Descriptive research

- Correlational research

Remember, it is only valuable and useful when it is valid, accurate, and reliable. Incorrect results can lead to customer churn and a decrease in sales.

It is essential to ensure that your data is:

- Valid – founded, logical, rigorous, and impartial.

- Accurate – free of errors and including required details.

- Reliable – other people who investigate in the same way can produce similar results.

- Timely – current and collected within an appropriate time frame.

- Complete – includes all the data you need to support your business decisions.

Gather insights

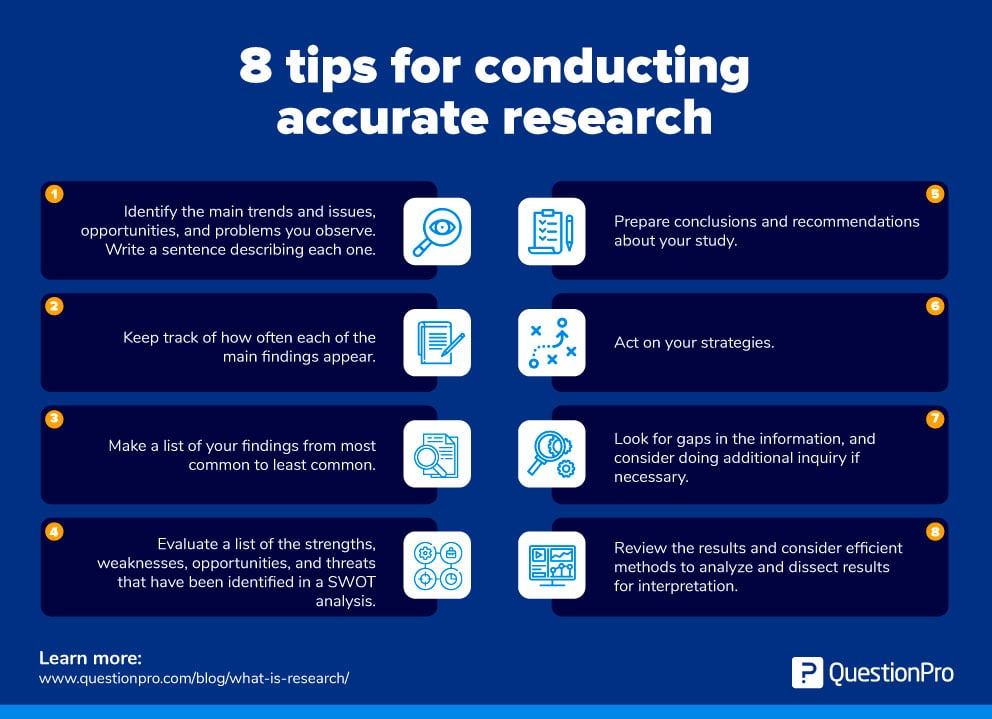

8 tips for conducting accurate research

- Identify the main trends and issues, opportunities, and problems you observe. Write a sentence describing each one.

- Keep track of the frequency with which each of the main findings appears.

- Make a list of your findings from the most common to the least common.

- Evaluate a list of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified in a SWOT analysis.

- Prepare conclusions and recommendations about your study.

- Act on your strategies

- Look for gaps in the information, and consider doing additional inquiry if necessary

- Plan to review the results and consider efficient methods to analyze and interpret results.

Review your goals before making any conclusions about your study. Remember how the process you have completed and the data you have gathered help answer your questions. Ask yourself if what your analysis revealed facilitates the identification of your conclusions and recommendations.

Research is an original and systematic investigation undertaken to increase existing knowledge and understanding of the unknown to establish facts and principles.

Some people consider research as a voyage of discovery of new knowledge.

It comprises the creation of ideas and the generation of new knowledge that leads to new and improved insights and the development of new materials, devices, products, and processes.

It should have the potential to produce sufficiently relevant results to increase and synthesize existing knowledge or correct and integrate previous knowledge.

Good reflective research produces theories and hypotheses and benefits any intellectual attempt to analyze facts and phenomena.

Where did the word Research Came from?

The word ‘research’ perhaps originates from the old French word “recerchier” which meant to ‘search again.’ It implicitly assumes that the earlier search was not exhaustive and complete; hence, a repeated search is called for.

In practice, ‘research’ refers to a scientific process of generating an unexplored horizon of knowledge, aiming at discovering or establishing facts, solving a problem, and reaching a decision. Keeping the above points in view, we arrive at the following definition of research:

Research Definition

Research is a scientific approach to answering a research question, solving a research problem, or generating new knowledge through a systematic and orderly collection, organization, and analysis of data to make research findings useful in decision-making.

When do we call research scientific? Any research endeavor is said to be scientific if

- It is based on empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of reasoning;

- It consists of systematic observations, measurement, and experimentation;

- It relies on the application of scientific methods and harnessing of curiosity;

- It provides scientific information and theories for the explanation of nature;

- It makes practical applications possible; and

- It ensures adequate analysis of data employing rigorous statistical techniques.

The chief characteristic which distinguishes the scientific method from other methods of acquiring knowledge is that scientists seek to let reality speak for itself, supporting a theory when a theory’s predictions are confirmed and challenging a theory when its predictions prove false.

Scientific research has multidimensional functions, characteristics, and objectives.

Keeping these issues in view, we assert that research in any field or discipline:

- Attempts to solve a research problem;

- Involves gathering new data from primary or first-hand sources or using existing data for a new purpose;

- is based upon observable experiences or empirical evidence;

- Demands accurate observation and description;

- Employs carefully designed procedures and rigorous analysis;

- attempts to find an objective, unbiased solution to the problem and takes great pains to validate the methods employed;

- is a deliberate and unhurried activity that is directional but often refines the problem or questions as the research progresses.

Characteristics of Research

Keeping this in mind that research in any field of inquiry is undertaken to provide information to support decision-making in its respective area, we summarize some desirable characteristics of research:

- The research should focus on priority problems.

- The research should be systematic. It emphasizes that a researcher should employ a structured procedure.

- The research should be logical. Without manipulating ideas logically, the scientific researcher cannot make much progress in any investigation.

- The research should be reductive. This means that one researcher’s findings should be made available to other researchers to prevent them from repeating the same research.

- The research should be replicable. This asserts that there should be scope to confirm previous research findings in a new environment and different settings with a new group of subjects or at a different point in time.

- The research should be generative. This is one of the valuable characteristics of research because answering one question leads to generating many other new questions.

- The research should be action-oriented. In other words, it should be aimed at solving to implement its findings.

- The research should follow an integrated multidisciplinary approach, i.e., research approaches from more than one discipline are needed.

- The research should be participatory, involving all parties concerned (from policymakers down to community members) at all stages of the study.

- The research must be relatively simple, timely, and time-bound, employing a comparatively simple design.

- The research must be as much cost-effective as possible.

- The research results should be presented in formats most useful for administrators, decision-makers, business managers, or community members.

3 Basic Operations of Research

Scientific research in any field of inquiry involves three basic operations:

- Data collection;

- Data analysis;

- Report writing.

- Data collection refers to observing, measuring, and recording data or information.

- Data analysis, on the other hand, refers to arranging and organizing the collected data so that we may be able to find out what their significance is and generalize about them.

- Report writing is the ultimate step of the study. Its purpose is to convey the information contained in it to the readers or audience.

If you note down, for example, the reading habit of newspapers of a group of residents in a community, that would be your data collection.

If you then divide these residents into three categories, ‘regular,’ ‘occasional,’ and ‘never,’ you have performed a simple data analysis. Your findings may now be presented in a report form.

A reader of your report knows what percentage of the community people never read any newspaper and so on.

Here are some examples that demonstrate what research is:

- A farmer is planting two varieties of jute side by side to compare yields;

- A sociologist examines the causes and consequences of divorce;

- An economist is looking at the interdependence of inflation and foreign direct investment;

- A physician is experimenting with the effects of multiple uses of disposable insulin syringes in a hospital;

- A business enterprise is examining the effects of advertisement of their products on the volume of sales;

- An economist is doing a cost-benefit analysis of reducing the sales tax on essential commodities;

- The Bangladesh Bank is closely observing and monitoring the performance of nationalized and private banks;

- Based on some prior information, Bank Management plans to open new counters for female customers.

- Supermarket Management is assessing the satisfaction level of the customers with their products.

The above examples are all researching whether the instrument is an electronic microscope, hospital records, a microcomputer, a questionnaire, or a checklist.

Research Motivation – What makes one motivated to do research?

A person may be motivated to undertake research activities because

- He might have genuine interest and curiosity in the existing body of knowledge and understanding of the problem;

- He is looking for answers to questions which remained unanswered so far and trying to unfold the truth;

- The existing tools and techniques are accessible to him, and others may need modification and change to suit the current needs.

One might research ensuring.

- Better livelihood;

- Better career development;

- Higher position, prestige, and dignity in society;

- Academic achievement leading to higher degrees;

- Self-gratification.

At the individual level, the results of the research are used by many:

- A villager is drinking water from an arsenic-free tube well;

- A rural woman is giving more green vegetables to her child than before;

- A cigarette smoker is actively considering quitting smoking;

- An old man is jogging for cardiovascular fitness;

- A sociologist is using newly suggested tools and techniques in poverty measurement.

The above activities are all outcomes of the research.

All involved in the above processes will benefit from the research results. There is hardly any action in everyday life that does not depend upon previous research.

Research in any field of inquiry provides us with the knowledge and skills to solve problems and meet the challenges of a fast-paced decision-making environment.

9 Qualities of Research

Good research generates dependable data. It is conducted by professionals and can be used reliably for decision-making.

It is thus of crucial importance that research should be made acceptable to the audience for which research should possess some desirable qualities in terms of its;

9 qualities of research are;

We enumerate below a few qualities that good research should possess.

Purpose clearly defined

Good research must have its purposes clearly and unambiguously defined.

The problem involved or the decision to be made should be sharply delineated as clearly as possible to demonstrate the credibility of the research.

Research process detailed

The research procedures should be described in sufficient detail to permit other researchers to repeat the research later.

Failure to do so makes it difficult or impossible to estimate the validity and reliability of the results. This weakens the confidence of the readers.

Any recommendations from such research justifiably get little attention from the policymakers and implementation.

Research design planner

The procedural design of the research should be carefully planned to yield results that are as objective as possible.

In doing so, care must be taken so that the sample’s representativeness is ensured, relevant literature has been thoroughly searched, experimental controls, whenever necessary, have been followed, and the personal bias in selecting and recording data have been minimized.

Ethical issues considered

A research design should always safeguard against causing mental and physical harm not only to the participants but also those who belong to their organizations.

Careful consideration must also be given to research situations when there is a possibility for exploitation, invasion of privacy, and loss of dignity of all those involved in the study.

Limitations revealed

The researcher should report with complete honesty and frankness any flaws in procedural design; he followed and provided estimates of their effects on the findings.

This enhances the readers’ confidence and makes the report acceptable to the audience. One can legitimately question the value of research where no limitations are reported.

Adequate analysis ensured

Adequate analysis reveals the significance of the data and helps the researcher to check the reliability and validity of his estimates.

Data should, therefore, be analyzed with proper statistical rigor to assist the researcher in reaching firm conclusions.

When statistical methods have been employed, the probability of error should be estimated, and criteria of statistical significance applied.

Findings unambiguously presented

The presentation of the results should be comprehensive, easily understood by the readers, and organized so that the readers can readily locate the critical and central findings.

Conclusions and recommendations justified.

Proper research always specifies the conditions under which the research conclusions seem valid.

Therefore, it is important that any conclusions drawn and recommendations made should be solely based on the findings of the study.

No inferences or generalizations should be made beyond the data. If this were not followed, the objectivity of the research would tend to decrease, resulting in confidence in the findings.

The researcher’s experiences were reflected.

The research report should contain information about the qualification of the researchers.

If the researcher is experienced, has a good reputation in research, and is a person of integrity, his report is likely to be highly valued. The policymakers feel confident in implementing the recommendation made in such reports.

Goals of Research

The primary goal or purpose of research in any field of inquiry; is to add to what is known about the phenomenon under investigation by applying scientific methods.

Though each research has its own specific goals, we may enumerate the following 4 broad goals of scientific research:

The link between the 4 goals of research and the questions raised in reaching these goals.

| Goals/Purposes of Research | Types of Questions in Research |

|---|---|

| Exploration | What is the full nature of the problem or phenomenon? What is going on? What factors are related to the problem? |

| Description | How prevalent is the problem? What are the characteristics of the problem? What is the process by which the problem is experienced? |

| Explanation | What are the underlying causes of the problem? What do the occurrences of the problem mean? Why does the problem exist? |

| Prediction | If problem X occurs, will problem K follow? Can the occurrence of the problem be controlled? Does an intervention result in the intended effect? |

Let’s try to understand the 4 goals of the research.

1. Exploration and Explorative Research

Exploration is finding out about some previously unexamined phenomenon. In other words, an explorative study structures and identifies new problems.

The explorative study aims to gain familiarity with a phenomenon or gain new insights into it.

Exploration is particularly useful when researchers lack a clear idea of the problems they meet during their study.

Through exploration, researchers attempt to

- Develop concepts more clearly;

- Establish priorities among several alternatives;

- Develop operational definitions of variables;

- Formulate research hypotheses and sharpen research objectives;

- Improve the methodology and modify (if needed) the research design.

Exploration is achieved through what we call exploratory research.

The end of an explorative study comes when the researchers are convinced that they have established the major dimensions of the research task.

2. Description and Descriptive Research

Many research activities consist of gathering information on some topic of interest. The description refers to these data-based information-gathering activities. Descriptive studies portray precisely the characteristics of a particular individual, situation, or group.

Here we attempt to describe situations and events through studies, which we refer to as descriptive research.

Such research is undertaken when much is known about the problem under investigation.

Descriptive studies try to discover answers to the questions of who, what, when, where, and sometimes how.

Such research studies may involve the collection of data and the creation of distribution of the number of times the researcher observes a single event or characteristic, known as a research variable.

A descriptive study may also involve the interaction of two or more variables and attempts to observe if there is any relationship between the variables under investigation.

Research that examines such a relationship is sometimes called a correlational study. It is correlational because it attempts to relate (i.e., co-relate) two or more variables.

A descriptive study may be feasible to answer the questions of the following types:

- What are the characteristics of the people who are involved in city crime? Are they young? Middle-aged? Poor? Muslim? Educated?

- Who are the potential buyers of the new product? Men or women? Urban people or rural people?

- Are rural women more likely to marry earlier than their urban counterparts?

- Does previous experience help an employee to get a higher initial salary?

Although the data description in descriptive research is factual, accurate, and systematic, the research cannot describe what caused a situation.

Thus, descriptive research cannot be used to create a causal relationship where one variable affects another.

In other words, descriptive research can be said to have a low requirement for internal validity. In sum, descriptive research deals with everything that can be counted and studied.

But there are always restrictions on that. All research must impact the lives of the people around us.

For example, finding the most frequent disease that affects the people of a community falls under descriptive research.

But the research readers will have the hunch to know why this has happened and what to do to prevent that disease so that more people will live healthy life.

It dictates that we need a causal explanation of the situation under reference and a causal study vis-a-vis causal research.

3. Causal Explanation and Causal Research

Explanation reveals why and how something happens.