A swear word is a word or phrase that’s generally considered blasphemous, obscene, vulgar, or otherwise offensive. These are also called bad words, obscenities, expletives, dirty words, profanities, and four-letter words. The act of using a swear word is known as swearing or cursing.

«Swear words serve many different functions in different social contexts,» notes Janet Holmes. «They may express annoyance, aggression and insult, for instance, or they may express solidarity and friendliness,» (Holmes 2013).

Etymology

From Old English, «take an oath.»

Swearing in Media

Profanities in today’s society are about as ubiquitous as air, but here is an example from media nonetheless.

Spock: Your use of language has altered since our arrival. It is currently laced with, shall we say, more colorful metaphors, «double dumbass on you,» and so forth.

Captain Kirk: Oh, you mean the profanity?

Spock: Yes.

Captain Kirk: Well, that’s simply the way they talk here. Nobody pays any attention to you unless you swear every other word. You’ll find it in all the literature of the period, (Nimoy and Shatner, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home).

Why Swear?

If using swear words is considered offensive or wrong, why do people do it? As it turns out, there are many reasons that people might choose to pepper their language with colorful curse words, and profanity actually serves a few meaningful roles in society. Here’s what the experts have to say about why, when, and how people swear.

Uses of Swear Words

«A final puzzle about swearing is the crazy range of circumstances in which we do it,» begins Steven Pinker. «There is cathartic swearing, as when we hit our thumb with a hammer or knock over a glass of beer. There are imprecations, as when we suggest a label or offer advice to someone who has cut us off in traffic. There are vulgar terms for everyday things and activities, as when Bess Truman was asked to get the president to say fertilizer instead of manure and she replied, ‘You have no idea how long it took me to get him to say manure.’

There are figures of speech that put obscene words to other uses, such as the barnyard epithet for insincerity, the army acronym snafu, and the gynecological-flagellative term for uxorial dominance. And then there are the adjective-like expletives that salt the speech and split the words of soldiers, teenagers, Australians, and others affecting a breezy speech style,» (Pinker 2007).

Social Swearing

«Why do we swear? The answer to this question depends on the approach you take. As a linguist—not a psychologist, neurologist, speech pathologist or any other -ist—I see swearing as meaningfully patterned verbal behaviour that readily lends itself to a functional analysis. Pragmatically, swearing can be understood in terms of the meanings it is taken to have and what it achieves in any particular circumstance. …

Typically, a social swear word originates as one of the ‘bad’ words but becomes conventionalised in a recognisably social form. Using swear words as loose intensifiers contributes to the easy-going, imprecise nature of informal talk among in-group members. … In sum, this is jokey, cruisy, relaxing talk in which participants oil the wheels of their connection as much by how they talk as what they talk about,»

(Wajnryb 2004).

Secular Swearing

Swearing, like any other feature of language, is subject to change over time. «[I]t would appear that in Western society the major shifts in the focus of swearing have been from religious matters (more especially the breaching of the commandment against taking the Lord’s name in vain) to sexual and bodily functions, and from opprobrious insults, such as coolie and kike. Both of these trends reflect the increasing secularization of Western society,» (Hughes 1991).

What Makes a Word Bad?

So how does a word become bad? Author George Carlin raises the point that most bad words are chosen rather arbitrarily: «There are four hundred thousand words in the English language and there are seven of them you can’t say on television. What a ratio that is! Three hundred ninety-three thousand nine hundred and ninety-three … to seven! They must really be bad. They’d have to be outrageous to be separated from a group that large. ‘All of you over here … You seven, you bad words.’ … That’s what they told us, you remember? ‘That’s a bad word.’ What? There are no bad words. Bad thoughts, bad intentions, but no bad words,» (Carlin 2009).

David Cameron’s ‘Jokey, Blokey Interview’

Just because many people swear doesn’t mean that swear words aren’t still controversial. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron once proved in a casual interview how quickly conversations can turn sour when swear words are used and lines between what’s acceptable and what’s not are blurred.

«David Cameron’s jokey, blokey interview … on Absolute Radio this morning is a good example of what can happen when politicians attempt to be down with the kids—or in this case, with the thirtysomethings. … Asked why he didn’t use the social networking website Twitter, the Tory leader said: ‘The trouble with Twitter, the instantness of it—too many twits might make a twat.’ … [T]he Tory leader’s aides were in defensive mode afterwards, pointing out that ‘twat’ was not a swear word under radio guidelines,» (Siddique 2009).

Censoring Swear Words

In an effort to use swear words without offending, many writers and publications will replace some or most of the letters in a bad word with asterisks or dashes. Charlotte Brontë argued years ago that this serves little purpose. «[N]ever use asterisks, or such silliness as b——, which are just a cop-out, as Charlotte Brontë recognised: ‘The practice of hinting by single letters those expletives with which profane and violent people are wont to garnish their discourse, strikes me as a proceeding which, however well-meant, is weak and futile. I cannot tell what good it does—what feeling it spares—what horror it conceals,'» (Marsh and Hodsdon 2010).

Supreme Court Rulings on Swear Words

When public figures are heard using especially vulgar expletives, the law will sometimes get involved. The Supreme Court has ruled on indecency countless times, spanning many decades and multiple occasions, though often brought to the court by the Federal Communications Commission. It seems that there aren’t clear rules as to whether the public use of swear words, though generally deemed wrong, should be punished. See what New York Times author Adam Liptak has to say about it.

«The Supreme Court’s last major case concerning broadcast indecency, F.C.C. v. Pacifica Foundation in 1978, upheld the commission’s determination that George Carlin’s classic ‘seven dirty words’ monologue, with its deliberate, repetitive and creative use of vulgarities, was indecent. But the court left open the question of whether the use of ‘an occasional expletive’ could be punished.

Metaphorical Suggestion

The case…Federal Communications Commission v. Fox Television Stations, No. 07-582, arose from two appearances by celebrities on the Billboard Music Awards. … Justice Scalia read the passages at issue from the bench, though he substituted suggestive shorthand for the dirty words. The first involved Cher, who reflected on her career in accepting an award in 2002: ‘I’ve also had critics for the last 40 years saying I was on my way out every year. Right. So F-em.’ (In his opinion, Justice Scalia explained that Cher ‘metaphorically suggested a sexual act as a means of expressing hostility to her critics.’)

The second passage came in an exchange between Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie in 2003 in which Ms. Richie discussed in vulgar terms the difficulties in cleaning cow manure off a Prada purse. Reversing its policy on such fleeting expletives, the commission said in 2006 that both broadcasts were indecent. It did not matter, the commission said, that some of the offensive words did not refer directly to sexual or excretory functions. Nor did it matter that the cursing was isolated and apparently impromptu.

Change in Policy

In reversing that decision, Justice Scalia said the change in policy was rational and therefore permissible. ‘It was certainly reasonable,’ he wrote, ‘to determine that it made no sense to distinguish between literal and nonliteral uses of offensive words, requiring repetitive use to render only the latter indecent.’

Justice John Paul Stevens, dissenting, wrote that not every use of a swear word connoted the same thing. ‘As any golfer who has watched his partner shank a short approach knows,’ Justice Stevens wrote, ‘it would be absurd to accept the suggestion that the resultant four-letter word uttered on the golf course describes sex or excrement and is therefore indecent.’

‘It is ironic, to say the least,’ Justice Stevens went on, ‘that while the F.C.C. patrols the airwaves for words that have a tenuous relationship with sex or excrement, commercials broadcast during prime-time hours frequently ask viewers whether they are battling erectile dysfunction or are having trouble going to the bathroom,'» (Liptak 2009).

The Lighter Side of Swear Words

Swearing doesn’t always have to be so serious. In fact, swear words are often used in comedy like this:

«‘Tell me, son,’ the anxious mother said, ‘what did your father say when you told him you’d wrecked his new Corvette?’

«‘Shall I leave out the swear words?’ the son asked.

«‘Of course.’

«‘He didn’t say anything,'» (Allen 2000).

Sources

- Allen, Steve. Steve Allen’s Private Joke File. Three Rivers Press, 2000.

- Carlin, George, and Tony Hendra. Last Words. Simon & Schuster, 2009.

- Holmes, Janet. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 4th ed., Routledge, 2013.

- Hughes, Geoffrey. Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. Blackwell, 1991.

- Liptak, Adam. «Supreme Court Upholds F.C.C.’s Shift to a Harder Line on Indecency on the Air.» The New York Times, 28 Apr. 2009.

- Marsh, David, and Amelia Hodsdon. Guardian Style. 3rd ed. Guardian Books, 2010.

- Pinker, Steven. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window Into Human Nature. Viking, 2007.

- Siddique, Haroon. «Sweary Cameron Illustrates Dangers of Informal Interview.» The Guardian, 29 July 2009.

- Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Dir. Leonard Nimoy. Paramount Pictures, 1986.

- Wajnryb, Ruth. Language Most Foul. Allen & Unwin, 2004.

According to the «Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,» the most offensive word in the universe is «Belgium.» The»Firefly» universe, on the other hand, uses invented swears and Chinese curses.

We all know what «bad words» are. Unlike most other language rules, we learn about swearwords and how to use them without any real study or classroom instruction. Even very young children know which words are naughty, although they don’t always know exactly what those words mean.

But swearwords aren’t quite as simple as they seem. They’re paradoxical — saying them is taboo in nearly every culture, but instead of avoiding them as with other taboos, people use them. Most associate swearing with being angry or frustrated, but people swear for a number of reasons and in a variety of situations. Swearing also serves multiple purposes in social interactions. Not only that, your brain treats swear words differently than it treats other words.

Most research on swearing printed in English discusses swearing in English. Although every culture has its own swearwords, the statistics in this article primarily come from research involving English-speaking people in the United States and Great Britain. Research related to swearing and the brain, however, should apply to speakers of any language.

People learning a new language often learn its swearwords first or learn and use swearwords from a variety of languages. Anyone who learns through immersion rather than in a classroom tends to use more swearwords and colloquialisms. People who speak more than one language often use swearwords from different languages, but feel that the words from their primary language have the most emotional impact. For this reason, some multilingual speakers will switch to a second language to express taboo subjects.

In this article, we’ll explore what makes words into swearwords, why most Americans use them and how society responds to swearing. We’ll also look at one of its most fascinating aspects — the way it affects your brain.

Virtually every language in every culture in the world has its own unique swearwords. Even different dialects of the same language can have different expletives. The very first languages probably included swearwords, but since writing evolved after speaking did, there’s no record of who said the first swearword or what that word was. Because of the taboos surrounding it, written language histories also include few records of the origins of swearing. Even today, many dictionaries don’t include profanity, and comparatively few studies have examined swearing.

Most researchers agree that swearing came from early forms of word magic. Studies of modern, non-literate cultures suggest that swearwords came from the belief that spoken words have power. Some cultures, especially ones that have not developed a written language, believe that spoken words can curse or bless people or can otherwise affect the world. This leads to the idea that some words are either very good or very bad.

While spoken swearwords from different languages don’t sound alike, they generally fall into one of two categories. Most of the time, they are either deistic (related to religion) or visceral (related to the human body and its functions). Some expletives also relate to a person’s ancestry or parentage. While some linguists classify racial slurs and epithets as swearwords, others place them in a separate category. So the words themselves are similar, but in different cultures people swear at different times and in different contexts.

By the second book in the series, the world of Harry Potter had its own racial epithet — «mudblood,» a repugnant word for wizards of non-magical parentage.

In the Western, English-speaking world, people from every race, class and level of education swear. In America, 72 percent of men and 58 percent of women swear in public. The same is true for 74 percent of 18 to 34 year olds and 48 percent of people who are over age 55 [ ref]. Numerous language researchers report that men swear more than women, but studies that focus on women’s use of language theorize that women’s swearing is simply more context specific.

So why do so many people swear? We’ll look at how swearing works in relationships and social interactions next.

Contents

- Why People Swear

- Social Responses to Swearing

- Swearing and the Law

- Swearing and the Brain

- Swearing and Brain Damage

Why People Swear

Rather than establishing his place in a group, Spock’s swearing in «Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home» humorously demonstrates that he does not belong.

In early childhood, crying is an acceptable way to show emotion and relieve stress and anxiety. As children, (especially boys) grow up, Western society discourages them from crying, particularly in public. People still need an outlet for strong emotions, and that’s where swearing often comes in.

A lot of people think of swearing as an instinctive response to something painful and unexpected (like hitting your head on an open cabinet door) or something frustrating and upsetting (like being stuck in traffic on the way to a job interview). This is one of the most common uses for swearing, and many researchers believe that it helps relieve stress and blow off steam, like crying does for small children.

Beyond angry or upset words said in the heat of the moment, swearing does a lot of work in social interactions. In the past, researchers have theorized that men swear to create a masculine identity and women swear to be more like men. More recent studies, however, theorize that women swear in part because they are emulating women they admire [ ref].

In addition, the use of particular expletives can:

Swearing vs. Cursing

A lot of people use the words «swearing» and «cursing» interchangeably. Some language experts, however, differentiate between the two. Swearing involves using profane oaths or invoking the name of a deity to give a statement more power or believability. Cursing takes aim at something specific, wishing for or trying to cause a target’s misfortune.

- Establish a group identity

- Establish membership in a group and maintain the group’s boundaries

- Express solidarity with other people

- Express trust and intimacy (mostly when women swear in the presence of other women)

- Add humor, emphasis or «shock value»

- Attempt to camouflage a person’s fear or insecurity

People also swear because they feel they are expected to or because swearing has become a habit. But just because swearing plays all these roles doesn’t mean it’s socially acceptable, or even legal. In the next sections, we’ll look at social and legal responses to swearing.

Social Responses to Swearing

How much is too much? One «South Park» episode uses the same expletive 162 times.

All languages have swearwords, but the words that are considered expletives and the social attitudes toward them change over time. In many languages, words that used to be taboo are now commonplace and other words have taken their place as obscenities. In American English, the words currently considered to be the most vulgar and offensive have existed for hundreds of years. Their designation as obscenities, however, took place largely during and after the 1800s. In fact, the use of the word «dirty» to describe words arose in the 19 th century, as did the word «profanity» [ ref].

Most languages also have a hierarchy of swearwords — some words are mildly offensive, while others are nearly unspeakable. This hierarchy usually has more to do with a society’s attitude toward the word than what the word actually means. Some words that describe extremely vulgar acts aren’t thought of as swearwords at all. In English-speaking countries, however, many people avoid using racial slurs to swear for fear of appearing racist. Women also tend to avoid the use of expletives that relate to the female sexual anatomy out of the belief that the words contain an element of sexism.

A little can go a long way for movies that use

exactly one expletive.

Western society generally views swearing as more appropriate for men than for women. Women who swear appear to violate more societal taboos than men who swear. People also tend to judge women more harshly than men for their use of obscenities. Society in general can also make moral judgments about women who swear and use non-standard English [ref]. In general, women also believe swearwords are more powerful and express more guilt about using them than men do.

Swearing on the Job

Swearing makes up 3 percent of all adult conversation at work and 13 percent of all adult leisure conversation. Source

In many English-speaking communities, expletives also carry connotations of lower classes and lower economic standing. Although people from every economic level use swearwords, many people associate their use with people of lower income and education.

Swearing isn’t just a social taboo, though. In some cases, it’s illegal. Next, we’ll look at expletives and the law.

Swearing and the Law

Just as cultures have different attitudes toward swearing and people who swear, they also have different laws governing people’s use of expletives. The Constitution of the United States guarantees that people have the right to freedom of speech in the First Amendment. The First Amendment applies specifically to Congress and the federal government, including the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Courts generally interpret that it also applies to state governments.

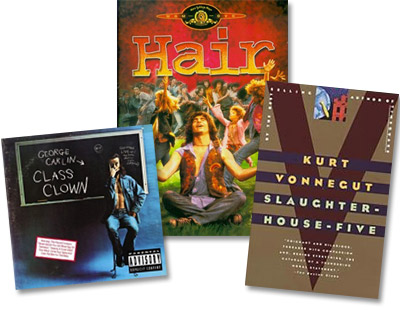

United States Supreme Court obscenity cases have involved George Carlin’s «Class Clown» and its infamous «seven words,» as well as a stage production of «Hair» and Kurt Vonnegut’s «Slaughterhouse-Five.»

So at first glance, it seems like people should be able to swear whenever they want and wherever they want because of their First Amendment rights. However, constitutional law can be tricky, and a wealth of court cases has led to a wide variety of judgments surrounding swearing. Obscenity generally falls into the category of unprotected speech — speech that is exempt from to the First Amendment rule. Other types of unprotected speech include:

- Language that incites people to violence or illegal activity

- Libel and defamation

- Threats

- False advertising

The unprotected speech exclusion is one of the reasons why the FCC can create and enforce decency rules for broadcast television and radio.

What to Do When Children Swear

Children mimic words they hear without always knowing what the words mean. When children mimic swear words, parents’ normal reactions of shock or amusement often reinforce children’s use of the words.

Instead of laughing or becoming upset if you hear your child swearing, you should:

- Explain that the word is not acceptable for children to use. The concept of a «bad word» can be foreign to children who are just learning how to speak.

- Offer an alternative word to use when angry or upset.

- Use humorous substitutes instead of swearwords in front of your children.

- Remain calm and matter-of-fact. If you get upset, your child may use the word again to try to get attention.

In addition to obscenity, court cases have examined the use of swearing in the contexts of inciting people to violence, defamation and threats. They have generally ruled that the government does not have the right to prevent blasphemy against a specific religion or to prosecute someone solely for the use of an expletive. On the other hand, they have upheld convictions of people who used profanity to incite riots, harass people or disturb the peace.

The First Amendment doesn’t generally apply to private organizations, and it has significantly less influence over businesses and schools. Courts frequently rule that organizations have the right to set and enforce their own standards of behavior and judgment. In addition, numerous sexual harassment cases have involved reports of swearing, and some courts have ruled that it creates a hostile environment and constitutes harassment.

Clearly courts, businesses and governments think swearing is different from other speech. Your brain agrees with them. We’ll look at swearing and the brain next.

Swearing and the Brain

The cerebral cortex has premotor and motor areas that control speech and writing. Wernicke’s area processes and recognizes spoken words. The prefrontal cortex controls personality and appropriate social behavior.

Your brain is a very complex organ, but there are only a few things you need to know about it to understand how it approaches swear words differently from other language:

- In most people, the left hemisphere is in charge of language. The right hemisphere creates the emotional content of language.

- Language processing is a «higher» brain function and takes place in the cerebral cortex.

- Emotion and instinct are «lower» brain functions and take place deep inside the brain.

Many studies suggest that the brain processes swearing in the lower regions, along with emotion and instinct. Scientists theorize that instead of processing a swearword as a series of phonemes, or units of sound that must be combined to form a word, the brain stores swear words as whole units [ref]. So, the brain doesn’t need the left hemisphere’s help to process them. Swearing specifically involves:

Swearing is connected to the limbic system and basal ganglia, located in the interior of the brain.

- The limbic system, which also houses memory, emotion and basic behavior. The limbic system also seems to govern vocalizations in primates and other animals, and some researchers have interpreted some primate vocalizations as swearing.

- The basal ganglia, which play a large role in impulse control and motor functions.

So, you can think of swearing as a motor activity with an emotional component.

Swearing Around the Office

An informal poll of HSW staff revealed the following «alternatives» to swearing — the words we say when swearing would be inappropriate:

- Dagnabit

- Oy

- Darn it

- Poop

- Funky tut

- Shang-a-lang

- Jebus

- Shoot

- Jeep ‘n eagle

- Son of a monkey

- Jeezy creezy

- Sweet cheeses

- Mother-scratcher

- Tartar sauce

- Oh, biscuits

- Zip -zap

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that the higher and lower parts of the brain can struggle with each other when a person swears [ ref]. A New York Times article cites several other studies that involve how a healthy brain processes swearing. For example, the brains of people who pride themselves on being educated respond to slang and «illiterate» phrases the same way they do to swearwords. In addition, in studies in which people must identify the color a word is written in (instead of the word itself), swearwords distract the participants from color recognition. You can also remember swearwords about four times better than other words [ ref].

Swearing can also be a symptom of disease or a result of damage to parts of the brain. We’ll look at swearing and brain disorders next.

Swearing and Brain Damage

A wide variety of neurological and emotional conditions can affect a person’s ability to speak and lead to excessive swearing. For example, people with various forms of aphasia lose the ability to speak or to pronounce words because of damage or disease in parts of the brain that govern language. Many aphasics retain the ability to produce automatic speech, which often consists of conversational placeholders like «um» and «er.» Aphasics’ automatic speech can include swear words — in some cases, patients can’t create words or sentences, but they can swear. Also, the ability to pronounce other words can change and evolve during recovery, while pronunciation and use of swearwords remains unchanged.

Damage to any area of the brain can affect the way the brain functions. Damage to areas that process language can lead to aphasia.

Patients who undergo a left hemispherectomy experience a dramatic drop in their language abilities. However, many people can still swear without their left hemisphere present to process the words. This may be because the right hemisphere of the brain can process whole swearwords as a motor function rather than a language function.

Coprolalia is the medical term for uncontrollable swearing and is a rare symptom of Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome (GTS). Published numbers vary widely, but relatively few people with GTS exhibit coprolalia, and more males than females experience it. It generally begins between four and seven years after the onset of tics, peaks during adolescence and tapers off drastically during adulthood. There have been medically documented cases of deaf people with GTS-related coprolalia using sign language to swear excessively.

Studies have made a connection between GTS, coprolalia, and the basal ganglia of the brain. Medical researchers have begun to theorize that basal ganglia dysfunction contributes to or is responsible for GTS and coprolalia. Coprolalia also has interesting parallels to more typical daily swearing — both tend to be more frequent among younger males.

Lots More Information

Related Articles

- How Anger Works

- How Body Language Works

- How Braille Works

- How Gossip Works

- How Sign Language Works

- How Your Brain Works

- How Cells Work

- How Lawsuits Work

- How does the FCC police obscenity?

- Does anger lead to better decision making?

More Great Links

- National Library of Medicine: Tourette Syndrome

- Center for Applied Linguistics

- FindLaw Supreme Court Center

- ACLU: Free Speech

Sources

- Angier, Natalie. «Almost Before We Spoke, We Swore.» New York Times. September 20, 2005.

- Austin, Elizabeth. «A Small Plea to Delete a Ubiquitous Expletive.» U.S. News and World Report. Vol. 24, no. 13. April 6, 1998.

- Bartlett, Thomas. «Expletives Deleted.» The Chronicle of Higher Education. Vol. 51, iss. 22. February 4, 2005.

- Berger, Stephen. «Scientists Explore the Basis of Swearing.» Johns Hopkins Newsletter. October 28, 2005. http://www.jhunewsletter.com/vnews/display.v/ART/2005/10/28/43617d07c24a7

-

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. «The Emotional Force of Swearwords and Taboo Words in the Speech of Multilinguals.» Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Vol. 25, no. 2 & 3, 2004.

http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/archive/00000062/01/dewaeleJMMD25.pdf - «Dirty Words: Oh #@*$.» Psychology Today. Vol. 27, no. 3 May 1994.

- Dooling, Richard. Blue Streak: Swearing, Free Speech and Sexual Harassment. Random House: 1996.

- Fleischman, John. «When they put it in writing, they were cursing, not cussing.» Smithsonian. Vol. 27, issue 1. April 1996.

- Grimm, Matthew. «When the Sh*t Hits the Fan.» American Demographics. Vol. 25, no. 10. December 2003.

- Kissling, Elizabeth Arveda. «‘That’s Just a Basic Teen-age Rule:’ Girls’ Linguistic Strategies for Managing the Menstruation Communication Taboo.» Journal of Applied Communication Research. Vol. 24, 1996.

-

Marshall, Paul. «Tourette’s Syndrome and Coprolalia.»

http://www.tourettes-disorder.com/symptoms/coprolalia.html - Mbaya, Maweja. «Linguistic Taboo in African Marriage Context.» Nordic Journal of African Studies . Vol, 12, no. 2. 2002.

- Montagu, Ashley. «The Anatomy of Swearing.» MacMillan: 1967

- Rayson, Paul, Geoffrey Leech and Mary Hodges. «Social Differentiation in the Use of English Vocabulary.» International Journal of Corpus Linguistics. Vol. 2, no. 1. 1997.

- Schapiro, Naomi A. «‘Dude, You Don’t Have Tourette’s’ Tourette’s Syndrome, Beyond the Tics.» Pediatric Nursing. Vol. 28, No. 3. May/June 2002.

- Sigel, Lisa Z. «Name Your Pleasure.» Journal of the History of Sexuality. Vol. 9, Iss. 4, 2000.

- Smith, S.A. «The Social Meanings of Swearing: Workers and Bad Language in Late Emperial and Early Soviet Russia.» Past and Present. August 1998.

- Spivey, Nigel. «Meditations on an F-theme.» The Spectator. June 20, 1992

- Stapleton, Karyn. «Gender and Swearing: A Community Practice.» Women and Language. Vol. 26, no. 2. Fall 2003.

- Tortora, Gerard J. and Sandra R. Grabowski. Principals of Anatomy and Physiology. 9th ed. John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

- van Lancker, D. and J. L. cummings. «Explectives: Neurolinguistic and Neurobehavioral Perspectives on Swearing.» Brain Research Reviews. Vol. 31, 1999.

Until relatively recently, it has been believed that swearing worsens, rather than improves, a situation. More recently, this view has been challenged. We’ll outline some of the science behind swearing. Read until the end to find out how cursing could actually be good for you.

A tiny disclaimer

Naturally, this blog post will be profane.

Why do we swear?

“Under certain circumstances, profanity provides a relief denied even to prayer.” — Mark Twain

Because swearing varies in context, the reasons we swear are complex. Here are just a few reasons why we swear:

Because we can

There is something exhilarating about breaking the rules. Because swear words are often related to taboos, when we swear we’re breaking those taboos for the sake of breaking them. The objective here, in swearing for swearing’s sake, can be to be offensive, or not.

To emphasise

Sometimes we just want to give our sentences that extra “oomph”. As John-Erik Jordan points out: “Swear words add emotion and urgency to otherwise neutral sentences.”

This can be an incredible writing device. It can actually make dialogue a little more realistic. Your character might be perfectly verbose — but why would they use some boring adverb where a curse word would do the trick? People are driven by emotion. If you step on a piece of Lego and you feel pain and anger, realistically you’re probably going to swear.

Someone who infamously loves to use profanity in his dialogue is Quentin Tarantino. Someone even counted every single swear word used in his movies. Both fans and people not so keen on his style would probably equally concede that his dialogue is fucking memorable.

For positive reasons

Contrary to centuries of puritanical views on cursing, swear words are becoming increasingly recognised as positive tools. (No pun intended.) As Timothy Jay and Kristin Janschewitz put it in their study:

“Swear words can achieve a number of outcomes, as when used positively for joking or storytelling, stress management, fitting in with the crowd, or as a substitute for physical aggression.”

To bond

Kay and Janschewitz mentioned ‘fitting in with the crowd’. Well, amongst groups of friends, swearing can be used in bonding ways. It’s a sign that friends are really comfortable with each other and in that case, they can call each other all sorts of things as terms of endearment.

What profanities are the most offensive?

As outlined, profanity can be a positive device. It helps us to let off steam, place emphasis on something or create a relaxed atmosphere. This isn’t to be confused with slurs.

Benjamin K Bergen, in his book What the F, details a UK survey on what words should be banned from daytime TV. The words considered the most profane are slurs — not swear words. For example, the ‘n’ word was at the top of the list.

Sexual words — where most of us Brits’ swear words come from — were considered comparatively less taboo.

This is because slurs are rooted in centuries of harmful prejudice. In the UK, we consider these instances of verbal abuse to be hate crimes. They centre on a person’s disability, race, religion, sexual orientation or transgender identity — these are called ‘protected characteristics’.

Most of us couldn’t really care less if our Prime Minister said the “f” word, but we do care about statements we don’t want to repeat on this blog.

This is where Readable’s profanity detector comes in. We acknowledge that if you’re doing professional writing, you probably don’t want to swear. But we don’t stop there. We have broadened our detector to pick out words and phrases which may be offensive. In fact, we’ve been focusing on our profanity detector in recent months. Our community manager Lindsay has been having a whale of a time handling our profane data to feed into development.

What makes a swear word stick?

Ever wondered why certain swear words are more common than others? Why they permeate multiple cultures and stand the test of time?

The swear words which have the most impact seem to date back the furthest. For example, the word ‘fuck’ dates back to 1568, whilst the ever-potent ‘cunt’ dates back to 1325.

This is partly due to how abrasive they are to say. As Benjamin K Bergen points out, “syllables of profane words tend to be closed.” Further, 95% of our profane monosyllabic words are closed syllables. Here’s a great passage where he explores how swear words are adapted for fiction:

“When English-speaking fantasy and science fiction writers invent new profanity in imaginary languages, what do those words sound like? Battlestar Galactica has frak (“fuck”). Farscape has frell (also “fuck”). Mork & Mindy had shazbot (a generic expletive). Dothraki, the invented language in HBO’s Game of Thrones, has govak (“fucker”) and graddakh (“shit”). Not all are monosyllabic, but they all end with closed syllables.”

95% of our profane monosyllabic words are closed syllables.

It’s really interesting that in order to have the same impact as real swear words, they have to sound similar. That closed syllable is what makes them sound harsher when spoken out loud, and this is what makes them stick.

Are we the only species which swears?

The short answer is “no”, but there is a fascinating study behind this. The study was called Project Washoe, which was initially to toilet train chimps via sign language. Here’s an excerpt from the study:

“In Project Washoe, the sign for “dirty” was bringing the knuckles up to the underside of the chin. And what happened spontaneously, without the scientists teaching them, was that the chimps started to use the sign for “dirty” in exactly the same way as we use our own excremental swear words.”

Mindblowingly, the chimps were reappropriating the sign in a profane way without instruction. The study just gets more fascinating from there. The chimps actually passed down the sign language to their offspring. Furthermore, they started to combine the sign for “dirty” with nouns to create insults for each other — for example, “dirty monkey”.

Is swearing the sign of a small vocabulary?

It is easy to assume that people who swear a lot don’t have a large vocabulary. Indeed, you can always find a more interesting word for something rather than falling back on a curse — but, it turns out this assumption about vocabulary is false.

In a study on the benefits of swearing:

“Participants were asked to list as many words that start with F, A or S in one minute. Another minute was devoted to coming up with curse words that start with those three letters. The study found those who came up with the most F, A and S words also produced the most swear words.”

People who have an extensive toolkit of curses tend to be verbose and intelligent. Other studies have found that people who swear a lot can be more honest, as well as being more creative.

Curse words are stored in the limbic system in the right side of the brain. This is a complex system of emotions and drives and is associated with creativity. So next time you think someone who swears like a sailor should “be a little more creative”, think again.

People who have an extensive toolkit of curses tend to be verbose and intelligent.

Does swearing reduce pain?

Previously, it has been thought that swearing exacerbates situations due to a thing called “catastrophising”. However, recent research has challenged this view.

Amazingly, swearing can reduce our perception of pain. In Emma Byrne’s book Swearing is Good For You, she details a study on this. The study involved testing plunging one’s hands in ice water and using swear words vs using non-cursing alternatives:

“It turned out that, when they were swearing, the intrepid volunteers could keep their hands in the water nearly 50 percent longer as when they used their non-cursing, table-based adjectives. Not only that, while they were swearing the volunteers’ heart rates went up and their perception of pain went down. In other words, the volunteers experienced less pain while swearing.”

So maybe the Lego example used earlier is not only cathartic but pain-relieving, too. Like anything else, there’s a time and a place for swearing. Being mindful of the context will help you use it in a positive way. Want to add some outdated curses to your vocabulary? Check out our blog post on how to swear like the old days.

In 2012, The Sun newspaper reported that the British MP Andrew Mitchell, then a prominent member of the UK government, had called a group of police officers ‘fucking plebs’. According to that story, the police thought about arresting him, but decided against it. In the wake of ‘plebgate’ (as this incident has become known), several journalists pointed to a double standard: Mitchell managed to escape arrest, but among the rest of us, arrests for swearing at the police are far from unheard of. These arrests have happened under Section 5 of the Public Order Act. People arrested under Section 5 can be issued with a Fixed Penalty Notice, and convictions can result in a fine. Swearing, it seems, can be a big deal. But why?

The Cambridge University Press’s online dictionary defines swearing as ‘rude or offensive language that someone uses, especially when they are angry’. Thinking of swearing as ‘rude or offensive language’ is a good start, but it is too rough for our purposes. For one thing, ‘rude or offensive language’ need not involve swearing at all. I am rude or offensive when I tell you that your new baby is hideous, when I accept your thoughtful gift without thanks, or when I crack a tasteless joke about death after you reveal that you have a terminal illness. Some definitions of swearing get around this issue by specifying that swearing should involve taboo (ie forbidden) language – but even this is not specific enough. Taboo language includes not only the familiar, bog-standard swear words like that mentioned above, but also other sorts of words that are not my focus here.

A category of non-swearing taboo language is blasphemous expressions and words that are otherwise unspeakable for certain religious groups. Another category is slurs: words that deride entire groups of people, and that are often associated with hate speech. In slurring someone – for example, by calling them a faggot – you express contempt not only for the person you are addressing, but also for a wider group to which they may belong; in this case, homosexual men. By contrast, in yelling ‘Fuck you!’ at someone, you do not express contempt for anyone other than the person you are addressing. The dividing line between swears and slurs is not clear-cut (we view ‘cunt’ as a swear, but it is deemed by some to be so universally offensive to women that it might be appropriate to view it as a slur too). The line between swears and religious taboo language is similarly fuzzy; consider that we can swear using the word ‘damn’. However, there is enough of a contrast between swearing and these other categories to make it worth separating them when we consider the ethical issues.

I’ll focus here on the non-slurring, non-religious swear words that, in English and many other languages, often have a sexual or a lavatorial theme. So, what’s special about these words? What sets them apart from other areas of language?

A clue is provided by the second part of the dictionary definition quoted above: the qualification that people swear ‘especially when they are angry’. It’s not quite right to link swearing uniquely with anger, but it does have a special role in expressing and communicating emotion. The expressions ‘My car has been stolen’ and ‘For fuck’s sake, my fucking car’s been stolen!’ both assert the same thing, but the second also conveys a sense of anger, desperation, and annoyance, thanks to the inclusion of swearing. As the linguist Geoffrey Nunberg has remarked, ‘[s]wear words don’t describe your feelings; they manifest them’. It is this unique role in expressing emotion that separates swearing from other uses of language, including other types of taboo language.

This unique psychological role gives swearing a unique linguistic role, too. Suppose we overhear somebody exclaim ‘Fuck it!’ when he accidentally spills tea in his lap. We can’t grasp the meaning of this exclamation by reflecting on the literal meanings of the words, as we’d do if the speaker had said ‘Eat it!’ or ‘Wash it!’ Someone who says ‘Fuck it!’ after slopping tea in his lap is not expressing a desire to fuck something, nor is he instructing anyone else to fuck something. To understand this exclamation, we need to consider not what the speaker is referring to or talking about, but what he aims to indicate about his emotions. This makes swearing, in such circumstances, more like a scream than an utterance: just like a scream, it expresses emotion without being about anything.

Perhaps this explains why swear words often fail to function like other words. Steven Pinker argues that ‘fucking’ is not an adjective because, if it were, ‘Drown the fucking cat’ would be interchangeable with ‘Drown the cat which is fucking’, just as ‘Drown the lazy cat’ is interchangeable with ‘Drown the cat which is lazy’. Quang Phuc Dong – a sweary pseudonym of the late linguist James D. McCawley – thinks, for various reasons, that ‘Fuck you!’ is not an imperative (that is, a command) like ‘Wash the dishes!’ One reason is that, unlike other imperatives, ‘Fuck you!’ cannot be conjoined with other imperatives in a single sentence. We can say ‘Wash the dishes and sweep the floor!’, but not ‘Wash the dishes and fuck you!’ And Nunberg suggests that ‘fucking’ is not an adverb like ‘very’ or ‘extraordinarily’, because while you can say, ‘How brilliant was it? Very,’ and, ‘How brilliant was it? Extraordinarily,’ you can’t say, ‘How brilliant was it? Fucking.’

The philosopher Joel Feinberg remarked that swear words ‘acquire their strong expressive power in virtue of an almost paradoxical tension between powerful taboo and universal readiness to disobey’. And, indeed, both in the UK and in many other cultures, we do much to prevent, censor, and punish swearing. This is often done informally: perhaps the most effective way of regulating swearing is through our awareness of attitudes towards it. Knowing that we face disapproval from others if we swear in the wrong context is effective at ensuring that we watch our language. But there are formal efforts to police swearing, too: swearing can get you fired from your job, fined, censored, and even arrested. The taboo against swearing is, it seems, a pretty serious matter.

A clue as to why lies in swearing’s focus on taboo topics, and the fact that different cultures give different weight to different taboo themes; for example, in English, blasphemous forms of swearing are relatively rare, and those that do exist – like ‘damn’ and ‘God’ – are considered pretty mild these days. But elsewhere, blasphemy plays a much larger role. Perhaps the most striking example is Quebec French, in which the strongest swears are terms relating to Catholicism. These include tabernak (tabernacle), criss (Christ), baptême (baptism), calisse (chalice), and osti (host). Je m’en calisse is equivalent to the English ‘I don’t give a fuck’. These expressions are considered stronger than standard French swears like merde (shit). They can be amplified by combining them with each other and with standard swears, as in Mon tabernak j’vais te décalliser la yeule, calisse (roughly, ‘Motherfucker, I’m gonna fuck you up as fuck’), and Criss de calisse de tabernak d’osti de sacrament (untranslatable expression of anger).

Blasphemy plays a large role in swearing in many religious cultures including Italian, Romanian, Hungarian, and Spanish – but some highly secular cultures also find religious swearing offensive. Godverdomme (Goddamn) remains one of the strongest expressions in Dutch. Perkele (the name of a pagan deity, now equivalent in meaning to ‘the devil’), Saatana (Satan), Jumalauta (literally ‘God help’, but used in a similar way to the English ‘Goddamn’), and Helvetti (hell) are all common and powerful ways of swearing in Finnish. For fanden, For helvede, and For Satan (‘For the devil’s/hell’s/Satan’s sake’) are widely-used Danish expressions; similarly, fan (Satan), helvete (hell), and jävla (derived from djävul, meaning ‘devil’) are common Swedish expressions.

While swearing’s power derives from taboo-breaking, the fact that swears refer to taboo topics does not explain why swearing itself is taboo

Some swearing is characterised by taboos relating to hierarchy; specifically, expressions of disrespect for certain individuals, commonly the mother of the person insulted. Examples include the Croatian expressions Pička ti materina (‘Your mother’s cunt’) and Jebo ti pas mater (‘A dog fucked your mother’); the Filipino Putang-ina (‘Whore-mother’); the Romanian Futu-ți dumnezeii mă-tii (‘Fuck your mother’s gods’) and Futu morții mă-tii (‘Fuck your mother’s dead relatives’); the Spanish Me cago en la leche de tu madre (‘I shit in your mother’s milk’), Me cago en tu tia (‘I shit on your aunt’), and Putamadre (‘Whore-mother’); the Turkish Ananı sikeyim (‘I fuck your mother’); and the Mandarin 肏你祖宗十八代 (‘Fuck your ancestors to the 18th generation’). The expression ‘Son of a bitch’ has equivalents in many other languages including French (Fils de pute), German (Hurensohn), Italian (Figlio di troia), and Turkish (Orospu çocuğu); as does ‘Motherfucker’ (for example, Mutterficker in German and Figlio di puttana in Italian).

Hierarchy and ancestry-themed swearing is less common in English – the expressions ‘Motherfucker’ and ‘Son of a bitch’ excepted – but the practice has a lofty historical pedigree. The following mother-disparaging exchange appears in William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus:

Demetrius Villain, what hast thou done?

Aaron That which thou canst not undo.

Chiron Thou hast undone our mother.

Aaron Villain, I have done thy mother.

Japanese offers perhaps the most striking example of a hierarchy-themed insult. One of the most effective ways to offend somebody in Japan is to address them as てめ, which is not a swear but a very derogatory form of ‘you’.

While swearing’s power derives from taboo-breaking, the fact that swears refer to taboo topics does not explain why swearing itself is taboo. There are, after all, inoffensive ways to refer to sensitive topics: we can say ‘poo’ or ‘faeces’ instead of ‘shit’, ‘vagina’ instead of ‘cunt’, and so on. While lavatorial and sexual functions are taboo, not all ways of referring to them are indecent. We are still in need of an explanation of what makes ‘shit’ more offensive than ‘poo’.

Some have suggested that the sound that swear words make contributes to their offensiveness. Pinker notes that ‘imprecations tend to use sounds that are perceived as quick and harsh’, and Kate Warwick hypothesises that the peculiar offensiveness of ‘cunt’ results from a combination of its meaning and ‘the sound of the word and the physical satisfaction of lobbing this verbal hand grenade’. There is something plausible about this. Trying to express anger using a swear word full of gentle, soft sounds – like the words ‘whiffy’ and ‘slush’ – would be the verbal equivalent of angrily trying to slam a door fitted with a compressed air hinge. Even so, the sound of swear words cannot fully account for their offensiveness. Many inoffensive words also sound ‘quick and harsh’, and some have benign alternative meanings (consider ‘prick’ and ‘cock’), or sound identical to parts of inoffensive words (‘cunt’ sounds identical to the first syllable of ‘country’ – a fact not lost on either John Donne, who ‘sucked on country pleasures’, or the anonymous author of the rugby song A Soldier I Will Be).

In any case, focusing on swear words themselves will not enable us to explain fully why they are offensive, because the offensiveness of a given utterance of a swear word is relative to the social and historical context. Swearing at a graveside during a funeral is more likely to cause offence than swearing while in the crowd at a football match, and using ‘damn’ is less likely to cause offence today than it was several decades ago. We can’t account for such contextual variations in swearing’s offensiveness by looking solely to features of swearing that do not vary with context, such as what swear words refer to and how they sound. We must look beyond the words themselves, and consider the broader behavioural contexts in which they appear.

Once we do this, the explanation is easier to find. We do, after all, have all sorts of preferences about how people behave. Many of these preferences are enshrined in our morality; others are associated with etiquette. Etiquette dictates that we hold our fork in our left hand and our knife in our right, that we remove hats when entering churches, that we say ‘thank you’ when people are kind to us, and so on. Etiquette varies with culture and upbringing, and its conventions are applied more strictly in some settings than in others. The fact that we have developed preferences for certain types of behaviour over others, often for apparently no good reason, makes it unsurprising that we should have preferences for certain forms of linguistic behaviour. Swearing is a form of dispreferred linguistic behaviour.

How do we get from this to an explanation of why swearing is offensive? Well, once we have established preferences about behaviour, the capacity for certain behaviour to become offensive arises quite naturally. To illustrate this, consider the following scenario (based on an actual and recurring series of events). Suppose that you make a new friend named Rebecca, and you fall into the habit of addressing her as Rachel. After you have done this a couple of times, Rebecca politely points out that her name is Rebecca, not Rachel. If, after she has drawn your attention to this, you persist in calling her Rachel, she is likely to begin to feel annoyed, and she might repeat the request to call her Rebecca. If you ignore her request a second or third time, then – provided that she has no reason to believe you have failed to understand her requests, nor that you are incapable of easily complying with them – she is likely to eventually view your behaviour as offensive. What started out as merely a dispreferred (by Rebecca) way of speaking, then, becomes offensive.

How does this happen? Well, the first time you call Rebecca Rachel, Rebecca takes you to have made an innocent and regrettably common mistake, and she assumes you meant no harm. When you continue to call her Rachel even after she has reminded you of her name, she concludes that you are being unreasonably inconsiderate of her wishes. And when you persist in calling her Rachel even after she has pointed out several times that this is not her name, it is difficult for her to avoid the conclusion that you are deliberately using an inappropriate form of address in order to upset her. Having started out assuming that you meant no harm, she comes to view your attitude towards her as hostile. And, indeed, it is hard to see how she could be mistaken.

In this example, we do not find an explanation for the offensiveness of the dispreferred expression in the expression itself. There is nothing whatsoever that is offensive about the name Rachel. Rather, the expression grows to be offensive after it has filtered through a chain of inferences that speaker and audience make about each other and about each other’s inferences. In essence: you know that Rebecca’s name is not Rachel, and you know that she dislikes being called Rachel, yet you nevertheless continue to call her Rachel; Rebecca knows that you know all this, and concludes from your behaviour in light of this knowledge that you are hostile towards her; you, in turn, recognise all this yet persist in calling her Rachel; Rebecca sees that you do this and so takes offence. Let’s call this way in which the offensiveness of dispreferred behaviour arises from these sorts of inferences between speaker and audience offence escalation.

Offence escalation promises to explain how swearing came to be viewed as offensive. The story begins with certain forms of speech being dispreferred. Once these preferences are established within a community of speakers, people’s knowledge that some expressions are to be avoided inevitably leads them to infer that if they do use a dispreferred expression, they will likely cause discomfort in their listener. And this makes using the dispreferred expression an even greater transgression: it is one thing unwittingly to use a disliked expression; quite another to use a disliked expression knowing that it is disliked, especially if our audience knows that we know that the expression is disliked. In the latter case, but not necessarily in the former, our audience has good reason to doubt our goodwill towards them; consequently, they are offended.

We need to add something to this offence escalation story to explain how words become swear words. As I have outlined it, offence escalation enables any word to become offensive, at least to someone, provided that it involves a word that the listener dislikes. As we see from the Rebecca/Rachel example, even a perfectly respectable name can become offensive to someone when used in a certain way. However, swear words are not merely words that are disliked, and which have subsequently grown to be offensive through a process of offence escalation. After all, ‘Rachel’ is not a swear word, even when used as described above. In addition to being dispreferred, swear words also share certain features in common, such as their focus on taboo topics like sex and defecation. They also, as we have noted, sound a certain way. Offence escalation does not explain why it is the taboo words with a particular sound, rather than other sorts of words, that get to be swear words.

The ‘quick and harsh’ sound of swear words plausibly adds drama to the gleeful thrill of taboo-breaking

In fact, that swear words are taboo-focused fits neatly into the offence escalation story. For a speaker to get the offence escalation process started, she needs to use an expression that she knows her listener will dislike. How can she do this? Well, if she knows her listener well enough to have a good sense of what sort of utterances he will dislike, then her job is easy, and she is well on her way to being able to offend him. For example, if her listener is sensitive about losing his hair, she can call him ‘baldy’. But what if the speaker knows nothing about the listener’s preferences? Or, what if the speaker is addressing multiple people with various preferences? Can she cause offence in these circumstances? The existence of taboos means that the answer is yes.

Provided that speaker and audience recognise the same taboos – which is likely if they belong to the same culture and speak the same language – the speaker knows something about which expressions her audience will probably dislike. She knows that her audience will likely find commonly dispreferred ways of referring to taboos unpleasant. And her audience will know that she knows that they will find such references unpleasant. This enables the offence escalation process to get off the ground. Moreover, it enables it to occur on a much larger scale, and much faster, than in the Rebecca/Rachel example described above: since taboo-related preferences are (and are known to be) widespread within a culture, one can annoy a great many people at once with a single taboo reference. And, unlike in the Rebecca/Rachel case, one’s audience does not need to point out that a given (taboo) expression is inappropriate, since everyone will take the speaker to understand this already.

The existence of widely recognised taboos, then, offers a fast-track route for certain expressions to become widely offensive. It also provides a certain motivation for this to happen: breaking widely recognised taboos can (unlike calling people by the wrong name) be thrilling. Shocking people can sometimes be fun. Perhaps this helps explain why swear words tend to sound a certain way: the ‘quick and harsh’ sound of swear words may not alone be enough to account for their offensiveness, but it plausibly adds drama to the gleeful thrill of taboo-breaking, so it should not be surprising that it is the fierce-sounding references to taboos that are singled out to become swear words.

However, swear words are more than words that are universally offensive within a given culture. Slurs, too, fit this description. It seems plausible that slurs, like swears, grow to be offensive through a process of offence escalation, yet they differ from swears in that they express contempt of a given group. Why is it that some widely dispreferred words develop into swear words whilst others develop into slurs?

I think that the answer lies in what the use of the dispreferred words is taken by speaker and audience to convey. That ‘fuck’ grows to be an offensive swear word can be attributed to the fact that the fuck-exclaiming speaker’s audience takes the speaker to be inconsiderate of their dislike of the word. That ‘nigger’ grows to be an offensive slur can be attributed to something a little different: to the audience’s recognition that the speaker aims, through the use of this dispreferred word, to convey her contempt of black people. We might also add – as philosophers who write about slurs sometimes do – that by using a slur, a speaker attempts to make her audience complicit in her contempt, by signalling that she believes herself to be among people who share her contempt. This, too, is offensive to an audience who does not share this contempt, and is insulted to be taken to do so. We can view the process of offence escalation as similar in the case of both swears and slurs – both involve the speaker’s and audience’s shared knowledge that the word is dispreferred – but whereas in the case of swears, the offence arises merely from the knowledge that the word is dispreferred (and therefore the speaker is inconsiderate in choosing to use it), in the case of slurs the offence arises also from the knowledge that the speaker aims to communicate to her audience a contemptuous attitude towards a certain group, and perhaps also an assumption that her audience shares this attitude.

Swearing, then, is as offensive as it is not because of some magic ingredient possessed by swear words but lacked by other words, but because when we swear, our audience knows that we do so in the knowledge that they will find it offensive. This is why context is important: there are some contexts in which we know we will not cause offence by swearing, and when we swear in such contexts our audience’s knowledge that we did so without expecting or intending to offend helps ensure that we do not offend. This explains why we are more tolerant of swearing by non-fluent speakers of our language, such as young children and non-native speakers, than we are of swearing by competent speakers. When non-fluent speakers swear, often we do not suspect them of doing so knowing that their words are offensive. Consequently, we are less likely to be offended.

You would find my refusal to thank you for your good turn rude, but you would probably not deem it morally suspect

Offence escalation helps explain why some swear words are more offensive than others; for example, why ‘cunt’ is more offensive than ‘shit’. Initially, ‘cunt’ is more strongly disliked than ‘shit’. Anyone who realises this, and who is taken by their audience to realise this, commits a greater transgression by saying ‘cunt’ than by saying ‘shit’. And that we know that we commit a greater transgression by saying ‘cunt’ than by saying ‘shit’ itself magnifies the offensiveness of ‘cunt’ relative to ‘shit’. The stronger the norms against using a particular expression, the greater the offensiveness of using that expression. In turn, the greater the offensiveness of a particular expression, the stronger the norms are against using that expression. Swearing’s offensiveness feeds itself.

What does this tell us about whether or not swearing is morally wrong? It is helpful, once again, to compare swearing to etiquette breaches. Since it’s preferable not to upset people where we can easily avoid doing so, we have some reason not to swear in contexts where it is likely to offend. The same holds for etiquette breaches. Even so, in most cases, we tend not to view breaches of etiquette as immoral, even where it causes offence. You would find my refusal to thank you for your good turn rude, but you would probably not deem it morally suspect. You would make a similar judgment were I to swear in the course of a polite conversation.

This is not to say that swearing, or breaching etiquette in some other way, is never immoral. We can imagine situations where breaching etiquette – by swearing inappropriately, addressing someone in an over-familiar way, refusing to adhere to a dress code, failing to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’, and so on – would cause upset, and we can imagine situations where we might deem it morally wrong. Such situations might involve breaching etiquette with the intention to belittle, distress, harass, intimidate, provoke, and so on. But most cases of etiquette breach – including most cases of swearing – are not like this. With this in mind, some of our efforts to punish and prevent swearing – such as arrest under the Public Order Act – seem overly draconian. Swearing is often objectionable, but rarely immoral.

Table of Contents

- Why did people make swear words?

- Is swearing a sign of anger?

- How can you make a girl miss you?

- How do you know if a girl loves you?

- How do you know if a girl doesn’t love you?

- How do you know a girl loves you through chatting?

- What does it mean when a girl texts you everyday?

- How do you tell if a girl is playing you?

- How do I win the heart of a married woman?

- How do you tell if a married woman is using you?

- Can a man fall in love with a married woman?

- What if a married man falls in love with you?

- What to do if you’re in love with a married woman?

For a word to qualify as a swear word it must have the potential to offend – crossing a cultural line into taboo territory. As a general rule, swear words originate from taboo subjects. As a result, “ficken” sounds way dirtier and meaner to most German speakers than the word “fuck” sounds to most English speakers.

Why did people make swear words?

The reason swearwords attract so much attention is that they involve taboos, those aspects of our society that make us uncomfortable. These include the usual suspects – private parts, bodily functions, sex, anger, dishonesty, drunkenness, madness, disease, death, dangerous animals, fear, religion and so on.

Is swearing a sign of anger?

Swearing Releases Anger and Frustration According to Psych Central, one reason we swear is to release anger and frustration that may cause us duress if pent up. They say not to bottle up thoughts, feelings, and emotions, so let them out in the form of swear words!

How can you make a girl miss you?

How To Make Her Miss You

- BE A LITTLE MYSTERIOUS.

- DON’T TALK TOO MUCH ABOUT YOURSELF.

- SLOW DOWN WITH THE TECHNOLOGY.

- SPEND SOME TIME APART.

- SHOW HER A FUN TIME.

- DON’T TALK TOO LONG ON THE PHONE.

- DON’T ACT DESPERATE.

- DON’T TRY TO KEEP TRACK OF HER ALL THE TIME.

How do you know if a girl loves you?

26 Ways to Tell If a Girl Likes You

- 26 Ways to Know If a Girl Likes You. The Sign.

- She Likes to Talk to You. Start a conversation with her.

- She Laughs at What You Say.

- Something Interesting Happens When Your Eyes Meet.

- She Notices You.

- She Licks Her Lips.

- She Smiles at You.

- She Doesn’t Like You Flirting With Other Girls.

How do you know if a girl doesn’t love you?

When she’s not in love she’ll cast you adrift like an afterthought. She hates it when you give her any advice. She starts interpreting every comment you make negatively. She wants to make it clear you’re no longer part of her life plans.

How do you know a girl loves you through chatting?

How to tell if a girl likes you over text: 24 surprising signs

- She starts texting you first.

- She is texting you A LOT.

- She is giving you frequent updates of what she is doing.

- She replies immediately.

- She makes an effort with her replies.

- She notices when you haven’t texted her lately.

- She’s sending you flirty and sexy messages.

- She can’t help but use cute and sexy emojis.

What does it mean when a girl texts you everyday?

So, what does it mean when a girl texts you every day? It could mean that she likes you especially if she only does it with you, she wants to hang out with you and she shows signs of attraction in person. It could also be that she considers you a friend or possibly that she does it for validation.

How do you tell if a girl is playing you?

- She Always Bails on Plans.

- She’s Constantly Flirting With Other Men.

- You’ve Never Been to Her Place.

- She Won’t Take Any Pictures With You.

- She Won’t Let You Meet Her Friends or Family.

- You’re an Alias in Her Phone.

- She Never Spends the Night.

- She Never Refers to You as Her Boyfriend.

How do I win the heart of a married woman?

Here are some tips that will help you attract that hot married woman with ease:

- Tell the married woman she is beautiful.

- Attract her by giving off positive vibes.

- Genuinely praise the married woman’s efforts.

- Attract the woman through listening.

- Dress to kill.

- Unpredictability is key.

- Make your intentions known.

How do you tell if a married woman is using you?

Is she using me: 6 Tips to know she’s using you!

- You have to pay for everything. It feels like she always gets her way.

- She avoids serious talks.

- She only wants to do things that she likes.

- She might not even know your last name.

- Pay attention to her body language.

- Maybe she just wants sex.

Can a man fall in love with a married woman?

Is it OK to fall in love with a married woman? Men can still be attracted to a married woman, and a single woman or a married woman can be attracted to someone other than their spouse. It is because of this that we cannot say it is wrong to love a married woman.

What if a married man falls in love with you?

5. He goes out of his way to help you. The fact that a married man has fallen in love with you becomes apparent when he does everything in his power to help you when you are facing a problem. He might be helping you because he is friendly, but if he is always there by your side, then it means he deeply cares about you.

What to do if you’re in love with a married woman?

How to End a Relationship With a Married Woman

- Tell her that you aren’t prepared to deal with the situation any longer.

- Delete all contact details.

- Unfriend her on social media.

- Unfriend her friends.

- Don’t call her to see if she’s okay.

- Don’t answer her calls and messages to you.

- Delete old messages and photos.