For those interested in a little info about this site: it’s a side project that I developed while working on Describing Words and Related Words. Both of those projects are based around words, but have much grander goals. I had an idea for a website that simply explains the word types of the words that you search for — just like a dictionary, but focussed on the part of speech of the words. And since I already had a lot of the infrastructure in place from the other two sites, I figured it wouldn’t be too much more work to get this up and running.

The dictionary is based on the amazing Wiktionary project by wikimedia. I initially started with WordNet, but then realised that it was missing many types of words/lemma (determiners, pronouns, abbreviations, and many more). This caused me to investigate the 1913 edition of Websters Dictionary — which is now in the public domain. However, after a day’s work wrangling it into a database I realised that there were far too many errors (especially with the part-of-speech tagging) for it to be viable for Word Type.

Finally, I went back to Wiktionary — which I already knew about, but had been avoiding because it’s not properly structured for parsing. That’s when I stumbled across the UBY project — an amazing project which needs more recognition. The researchers have parsed the whole of Wiktionary and other sources, and compiled everything into a single unified resource. I simply extracted the Wiktionary entries and threw them into this interface! So it took a little more work than expected, but I’m happy I kept at it after the first couple of blunders.

Special thanks to the contributors of the open-source code that was used in this project: the UBY project (mentioned above), @mongodb and express.js.

Currently, this is based on a version of wiktionary which is a few years old. I plan to update it to a newer version soon and that update should bring in a bunch of new word senses for many words (or more accurately, lemma).

We intuitively know what a WORD is. In written language words are separated by spaces. In spoken language you can sometimes hear a pause between them, although in most cases there’s nothing noticeable that separates words in spoken language.

We can distinguish the orthographic word, the grammatical word and the lexeme.

An ORTHOGRAPHIC WORD is a word form separated by spaces from other orthographic words in written texts and the corresponding form in spoken language.

In the example:

She wanted to win the game.

there are six orthographic words: she, wanted, to, win, the and game.

A GRAMMATICAL WORD is a word form used for a specific grammatical purpose.

For example in the sentence:

That man over there said that he would like to talk to you.

we have the word THAT used twice. This is one orthographic word, but we’re dealing with two grammatical words here: the first THAT is a demonstrative adjective and the other THAT is a conjunction.

A LEXEME is a group of word forms with the same basic meaning that belong to the same word class.

For example the words AM, WAS, IS belong to one lexeme, as they have the same basic meaning and are all verbs. Also the words COME and CAME belong to the same lexeme.

How do they relate to one another?

In many cases orthographic and grammatical words overlap. For example in the sentence:

They bought the house.

there are four orthographic words and four grammatical words, so there is one-to-one correspondence in this case.

But if we slightly modify the sentence like so:

They didn’t buy the house.

there are now five orthographic words and six grammatical words. This is because the orthographic word DIDN’T represents a sequence of two grammatical words: DID + NOT.

It may also be the other way around. In the sentence:

I kind of like it.

there are five orthographic words, but only four grammatical words, because the two orthographic words KIND OF actually represent a single grammatical word.

You can also watch the video version here:

-

Types

of grammatical description of the English language (= varieties of

Grammar).

-

The

notion of grammar. Descriptive vs prescriptive grammar.

TRADITIONALLY

in linguistics, grammar

is the set of structural rules that governs the composition of

clauses, phrases, and words in any given natural language.

-

abstract

character:

it abstracts itself from particular & concrete and builds its

rules & laws, taking into consideration only common features of

groups and words. -

stability

(laws & categories of Grammar exist through ages without

considerable changes).

Descriptive

is an approach that describes the grammatical constructions

that are used in a language, without making any evaluative judgments

about their standing in society.

These

grammars are commonplace in linguistics, where it is standard

practice to investigate a ‘corpus’ of spoken or written material, and

to describe in detail the patterns it contains.

-

Cognitive

-

Comparative

-

Generative

-

Mental

-

Performance

-

Reference

-

Theoretical

-

Transformational

-

Universal

Prescriptive

try

to enforce rules about what they believe to be the correct uses of

language.

is

a manual that focuses on constructions where usage is divided, and

lays down rules governing the socially correct use of language.

-

Pedagogical

(traditional), -

Practical

-

Grammatical

analysis and instruction designed for second-language students. -

Pedagogical

grammar

is

commonly used to denote.

(1)

pedagogical

process—

the explicit treatment of elements of the target language systems as

(part of) language teaching methodology;

(2)

pedagogical

content-reference

sources of one kind or another that present information about the

target language system

1)Comparative

grammar

was

important in Europe (19th c.). Also called comparative philology, was

originally stimulated by the discovery by Sir William Jones (1786)

that Sanskrit was related to Latin, Greek, and German. Is the study

of the relationships or correspondences between two or more languages

and the techniques used to discover whether the languages have a

common ancestor. provides an explanatory basis for how a human being

can acquire a first language.

The

theory of grammar is a theory of human language and hence establishes

the relationship among all languages.

-

It

assumed a view of linguistic change as large, systematic and lawful

and on the basis of this assumption attempted to explain the

relationship between languages in terms of a common ancestor often a

historical one for which there was no actual evidence in the

historical record.

2)Generative

grammar

arguably

originates in the work of Noam Chomsky, beginning in the late 1950s.

refers

to a particular approach to the study of syntax. attempts to give a

set of rules that will correctly predict which combinations of words

will form grammatical sentences. GG rules function as an algorithm to

predict grammaticality as a discrete (yes-or-no) result.

3)Mental

grammar

The

generative grammar stored in the brain that allows a speaker to

produce language that other speakers can understand, the innate basis

for learning, speaking and understanding any (verbal) language.»All

humans are born with the capacity for constructing a Mental Grammar,

given linguistic experience; this capacity for language is called

the Language Faculty (Chomsky)

4)Pedagogical (traditional) grammar

5)Performance

grammar

aims

not only at describing and explaining intuitive judgments and other

data concerning the well-formedness of sentences of a language as

they are actually used by speakers in dialogues.

PG

centers attention on language production; the problem of production

is dealt with before problems of reception and comprehension

6)Reference grammar

7)Theoretical

grammar

An

approach that goes beyond the study of individual languages, to

determine what constructs are needed in order to do any kind of

grammatical analysis, and how these can be applied consistently in

the investigation of linguistic universals Unlike school grammar,

theoretical grammar does not always produce a ready-made decision. In

language there are a number of phenomena interpreted differently by

different linguists

grammar

Models

of Tras. G

Standard

Theory (1957–1965)

Extended

Standard Theory (1965–1973)

Revised

Extended Standard Theory (1973–1976)

Relational

grammar (ca. 1975–1990)

Government

and binding/Principles and parameters theory (1981–1990)

Minimalist

Program (1990–present)

9)Universal

grammar

(Noam

Chomsky): ability

to learn grammar is hard-wired

into

the brain.

linguistic ability manifests itself without being taught, and that

there are properties that all natural human languages share. It is a

matter of observation and experimentation to determine precisely what

abilities are innate and what properties are shared by all languages.

-

Morphology

and syntax as parts of grammar.

The

grammatical structure of language comprises two major parts –

morphology and syntax. The two areas are obviously interdependent and

together they constitute the study of grammar.

Morphologydeals

with paradigmatic and syntagmatic properties of morphological units –

morphemes and words. It is concerned with the internal structure of

words and their relationship to other words and word forms within the

paradigm. It studies morphological categories and their realization.

Syntax,

on the other hand, deals with the way words are combined. It is

concerned with the external functions of words and their relationship

to other words within the linearly ordered units – word-groups,

sentences and texts. Syntax studies the way in which the units and

their meanings are combined. It also deals with peculiarities of

syntactic units, their behavior in different contexts.

Syntacticunits

may be analyzed from different points of view, and accordingly,

different syntactic theories exist.

-

Theoretical

grammar of English as a branch linguistics

An

approach that goes beyond the study of individual languages, to

determine what constructs are needed in order to do any kind of

grammatical analysis, and how these can be applied consistently in

the investigation of linguistic universals.

Unlike

school grammar, theoretical grammar does not always produce a

ready-made decision. In language there are a number of phenomena

interpreted differently by different linguists.

TG

studies the forms of the words & their relations in sentences in

more abstract way, giving the profound description of existing

grammatical laws & tendencies; looks inside into the structure of

parts of language & expose the mechanisms of their

functioning.

The

aim of TG is to present a scientific description of a certain

language in terms of its grammatical system.

-

Typological

classification of languages. Synthetic and analytic grammatical

means.

Attempts

to classify languages by their types rather than by their

relationships were made from the beginning of historical linguistics.

In 1818 August Von Schlegel proposed a typological classification

which was widely followed and elaborated through the 19th century and

still has a great popularity. Schlegel’s system was based on the

number of meaningful elements (morphemes) which could be present in a

word and the modification these might undergo. According to this

classification, languages can be divided into three types- isolating

or analytic, inflectional or synthetic, and agglutinative

1.ISOLATING

(analysis): Isolating languages exhibit no formal paradigms. It has

only one element of basic meaning per word and in such cases they are

monomorphemic. For example, when, as, since, from, etc. and their

grammatical status and class-membership is determined by their

syntactic relations with the rest of the sentence in which they

occur. In English invariable words such as prepositions, conjunctions

and many adverbs are isolating in types. Chinese, several other

Southeast Asian languages-Vietnamese are examples of such types.Words

in such languages are assigned to word-classes on the basis of

different syntactic functions.

2.

INFLECTIONAL: If there are several meaningful elements, but are in

some way fused together or are modified in different contexts, the

language will be inflectional. In it words having several grammatical

forms in which it is difficult to assign each category to a specific

and serially identifiable morphemic section. Classical languages such

as Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit are the most obvious examples of

such type.

English

nouns such as men, geese, mice, women are inflectional. Inflectional

languages were held to represent the highest stage of evolution and

the most perfect form of human communication.

3.

AGGLUTINATIVE: If there is more than one element of basic meaning,

but these were kept apart from one another and undergo no

modification, the language is agglutinative. Morphologically complex

words in which individual grammatical categories may be easily

assigned to morphemes stung together serially in the structure of the

word-form exemplify the process of agglutination. Turkish, Sudanese

and Japanese are examples of such type with the Turkish as the

perfect one. Languages of these types are alike of necessity in

respect of word structure. Grammars of these languages are very

different in other respects.

-

Analytic

languages.

analytic

/ isolating / root languages (English, Chinese, Vietnamese) — all

words are invariable

—

syntactic relationships are shown by word order

—

in order to express person, case, and other categories, the language

needs single words

—

prepositional phrases and modal verbs are used → to

the boy, did he arrive?

-

are

defined as being of ‘external’

grammar

of the word. -

Analytic

features are traced in morphological lack of changeability of the

word and existence of periphrastic constructions. The words

remaining morphologically unchanged convey the grammatical meaning

by combining with auxiliary or notional words, word order is strict. -

Many

words – analytic

-

Synthetical

languages.

—

synthetic

/ inflectional / inflecting languages (Czech, Finnish, Latin, Arabic)

—

the words typically contain more than one morpheme

—

there is no one-to-one correspondence between the morphemes and the

linear structure of the word

—

words are formed by suffixes, declination, conjugation etc.

—

forms of person, case, and other categories are compounded in one

word

—

are defined as the languages of the ‘internal’

grammar

of the word.

—

are inflectional: most grammatical meanings and most grammatical

relations of the words are primarily expressed by inflectional

devices.

-

Morphological

forms can be regarded as synthetic where the base of the word is

inseparably connected with its formants, presenting a grammatical

category. -

More

than one morpheme in a word — synthetic

-

Language

system and language structure.

Language

is regarded as a system of elements (or: signs, units) such as

sounds, words, etc. These elements have no value without each other,

they depend on each other, they exist only in a system, and they are

nothing without a system. System implies

the characterization of a complex object as made up of separate parts

(e.g. the system of sounds). Language is a structural

system. Structuremeans

hierarchical layering of parts in `constituting the whole. In the

structure of language there are four main structural levels:

phonological, morphological, syntactical and supersyntatical. The

levels are represented by the corresponding level units:

The phonological level

is the lowest level. The phonological level unit is the`phoneme.

It is a distinctive unit (bag

– back).

The morphological level

has two level units:

-

the `morpheme –

the lowest meaningful unit (teach

– teacher); -

the word

— the

main naming (`nominative) unit of language.

The syntactical level

has two level units as well:

-

the word-group –

the dependent syntactic unit; -

the sentence –

the main communicative unit.

The supersyntactical level

has the text as

its level unit.

To

sum it up, each level has its own system. Therefore, language is

regarded as a system of systems. The level units are built up in the

same way and that is why the units of a lower level serve the

building material for the units of a higher level. This similarity

and likeness of organization of linguistic units is

called isomorphism.

This is how language works – a small number of elements at one

level can enter into thousands of different combinations to form

units at the other level.

-

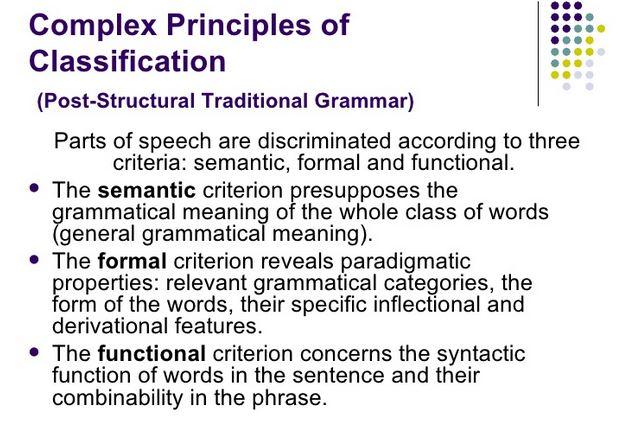

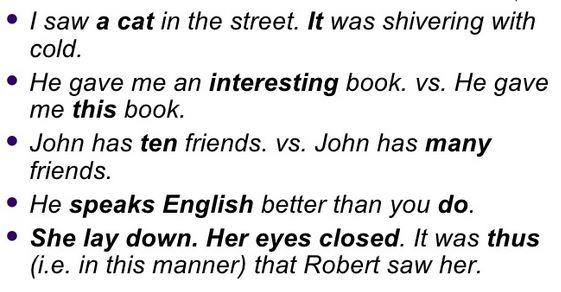

Parts

of speech in English: criteria.

The

parts of speech are classes of words, all the members of these

classes having certain characteristics in common which distinguish

them fr om the members of other classes. The problem of word

classification into parts of speech still remains one of the most

controversial problems in modern linguistics. There are four

approaches to the problem:

-

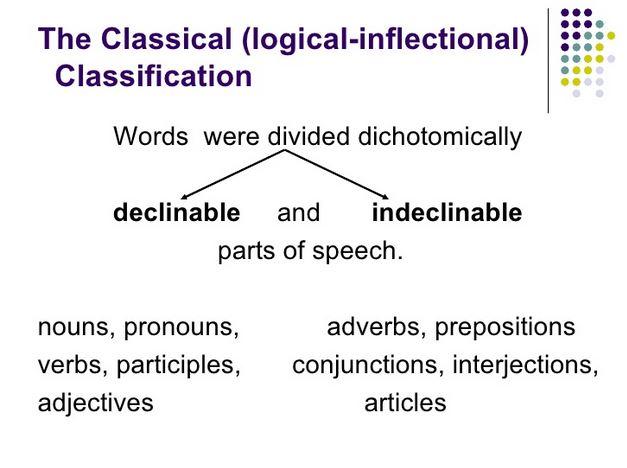

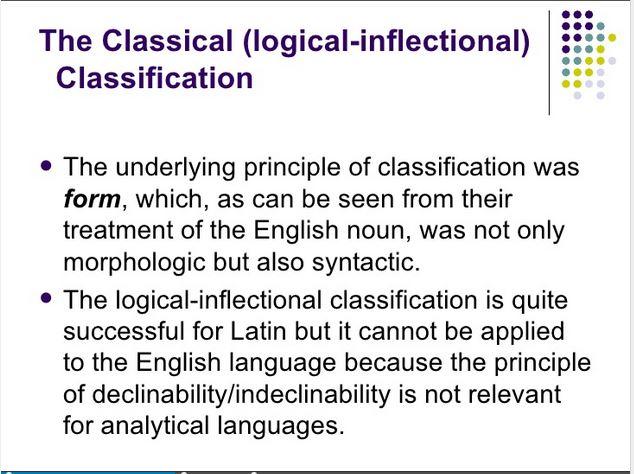

Classical

(logical-inflectional) -

Functional

-

Distributional

-

Complex

-

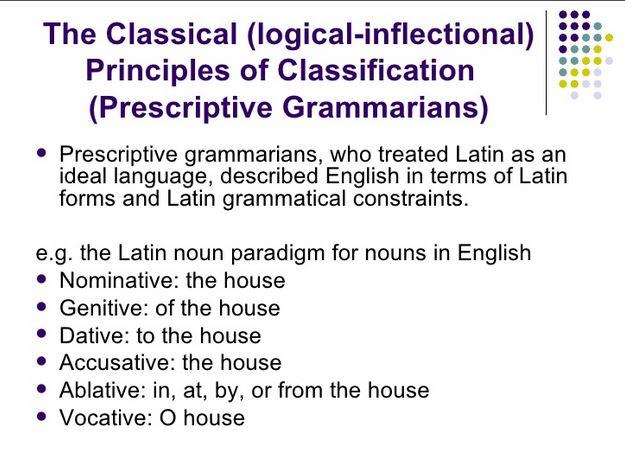

Classical

approach

-

Functional

approach

-

Distributional

approach

-

Complex

approach

-

The

field nature of parts of speech

-

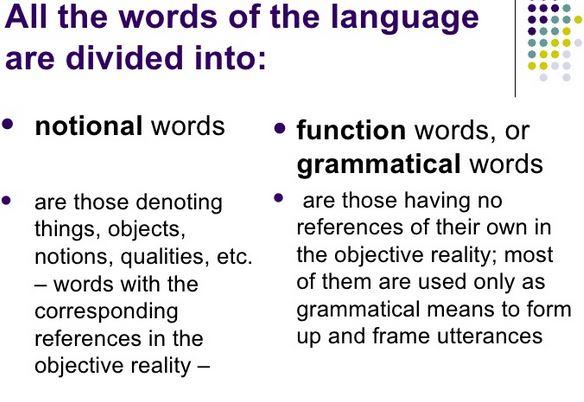

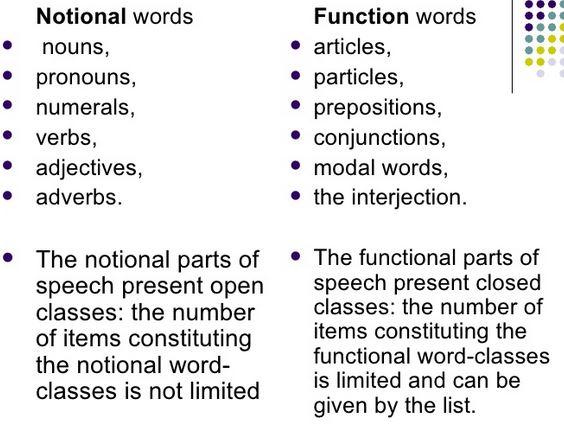

The

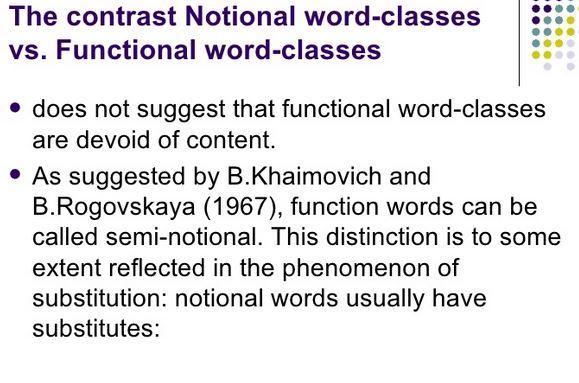

notional :: functional parts of speech

Notional

parts of speech perform certain functions in the sentence whereas

functional express relations between the words. Functional parts of

speech never change their form.

-

Limitations

to the traditional classification of the parts of speech in English

Traditionally,

all parts of speech are subdivided on the upper level of

classification into notional

words andfunctional

words.

Notional words, which traditionally include nouns, verbs, adjectives,

adverbs, pronouns and numerals, have complete nominative meanings,

are in most cases changeable and fulfill self-dependent syntactic

functions in the sentence. Functional words, which include

conjunctions, prepositions, articles, interjections, particles, and

modal words, have incomplete nominative value, are unchangeable and

fulfill mediatory, constructional syntactic functions.

There

are certain limitations and controversial points in the traditional

classification of parts of speech, which make some linguists doubt

its scientific credibility. First of all, the three

criteria(semantic,formal,functional)

turn out to be relevant only for the subdivision of notional words.

As

for functional words, they are rather characterized by the absence of

all three criteria in any generalized form.

Second,

the status of pronouns and the numerals, which in the traditional

classification are listed as notional, is also questionable, since

they do not have any syntactic functions of their own, but rather

different groups inside these two classes resemble in their formal

and functional properties different notional parts of speech: e.g.,

cardinal numerals function as substantives, while ordinal numerals

function as adjectives; the same can be said about personal pronouns

and possessive pronouns.

Third,

it is very difficult to draw rigorous borderlines between different

classes of words, because there are always phenomena that are

indistinguishable in their status. E.g., non-finite forms of verbs,

such as the infinitive, the gerund, participles I and II are actually

verbal forms, but lack some of the characteristics of the verb: they

have no person or number forms, no tense or mood forms, and what is

even more important, they never perform the characteristic verbal

function, that of a predicate. There are even words that defy any

classification at all; for example, many linguists doubt whether the

words of agreement and disagreement, yes and no, can

occupy any position in the classification of parts of speech.

These,

and a number of other problems, made linguists search for alternative

ways to classify lexical units. Some of them suggested that the

contradictions should be settled if parts of speech were classified a

unified basis of subdivision; in other words, if a homogeneous, or

monodifferential classification of parts of speech were undertaken.

It must be noted that the idea was not entirely new. The first

classification of parts of speech was homogeneous: in ancient Greek

grammar the words were subdivided mainly on the basis of their formal

properties into changeable and unchangeable; nouns, adjectives and

numerals were treated jointly as a big class of “names” because

they shared the same morphological forms. This classical linguistic

tradition was followed by the first English grammars: Henry Sweet

divided all the words in English into “declinables” and

“indeclinables”.

-

Alternative

approaches to the traditional classification of the parts of speech

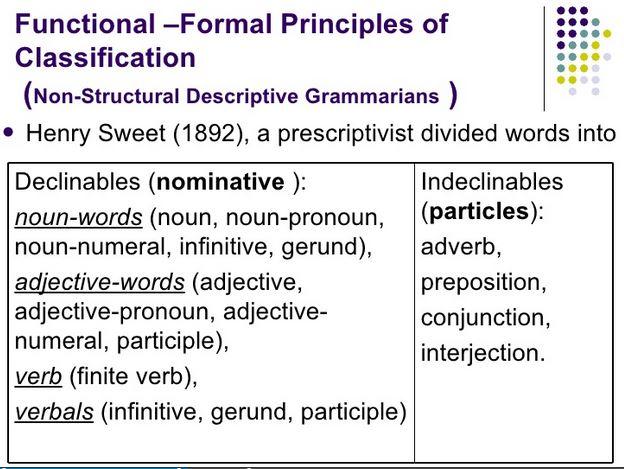

H.

Sweet is a prominent English grammarian. His “New English Grammar,

Logical and Historical” (1891) is an attempt of a descriptive

grammar intended to break away from the canons of classical Latin

grammar and to give scientific explanation to grammatical phenomena.

His classification of parts of speech makes distinction between: 1)

declinables: — noun-words: nouns, noun-pronouns, noun-numerals,

infinitives, gerunds; — adjective-words: adjectives,

adjective-pronouns, adjective-numerals, participles; — verbs: finite

verbs, verbals (infinitive, participle, gerund); 2) indeclinables

(particles): adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, interjections. H.

Sweet could not fully disentangle himself from the rules of classical

grammar (Greek, Latin).

In

“The Philosophy of Grammar” (1924) he presents his Theory of

Three Ranks describing the hierarchy of syntactic relations

underlying linear representation of elements in language structures.

The theory is based on the concept of determination. The “rank”

of a word (primary, secondary, or tertiary) depends upon its relation

(that of defined or defining) to other words in a sentence.

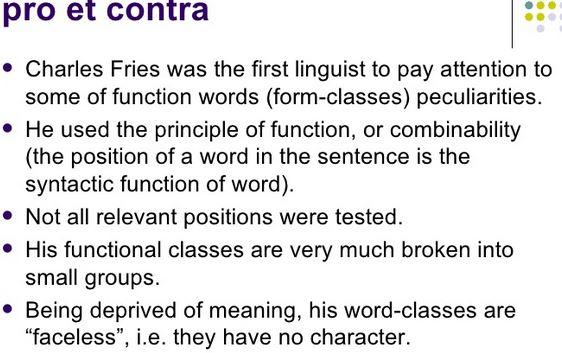

Nothing

cardinally different from the traditional approach in the

part-of-speech classification was produced by various English

grammars within the period between the works of O. Jespersen and the

appearance of Ch. Fries’s book “The Structure of English”

(1952). Ch. Fries belongs to the American school of descriptive

linguistics for which the starting point and basis of any linguistic

analysis is the distribution of elements. In contrast to other

representatives of that school, who excluded meaning from linguistic

description, Fries recognized its importance. He introduced the

notion of structural meaning as different from the lexical meaning of

words. In his opinion, the grammar of the language consists of the

devices that signal structural meanings.

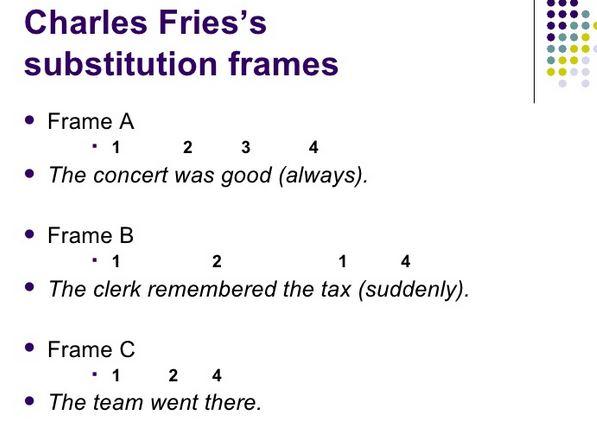

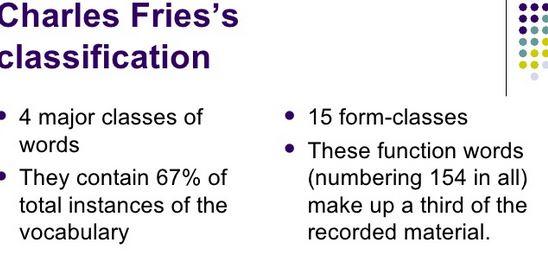

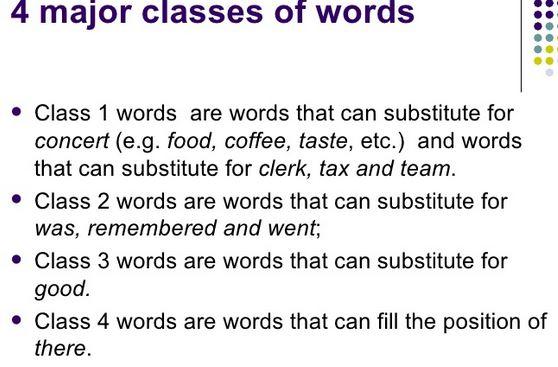

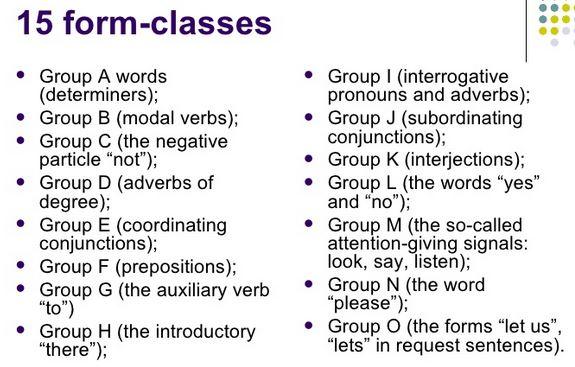

So a part of speech,

according to Ch. Fries, is a functional pattern. All the words which

can occupy the same ‘set of positions’ in the pattern of English

utterances must belong to same part of speech. Fries recorded 50

hours of conversation by 300 different speakers and analyzed 250.000

word entries. As a result of this analysis he singles out four

wordclasses (1, 2, 3, and 4) and 15 subclasses of function words

(designated by the letters of Latin alphabet), in which the

properties of different word-classes, which are singled out by

traditional grammar, are dissolved in the distributional patterns.

Ch. Fries’s book presents a major linguistic interest as an

experiment rather than for its achievements.

-

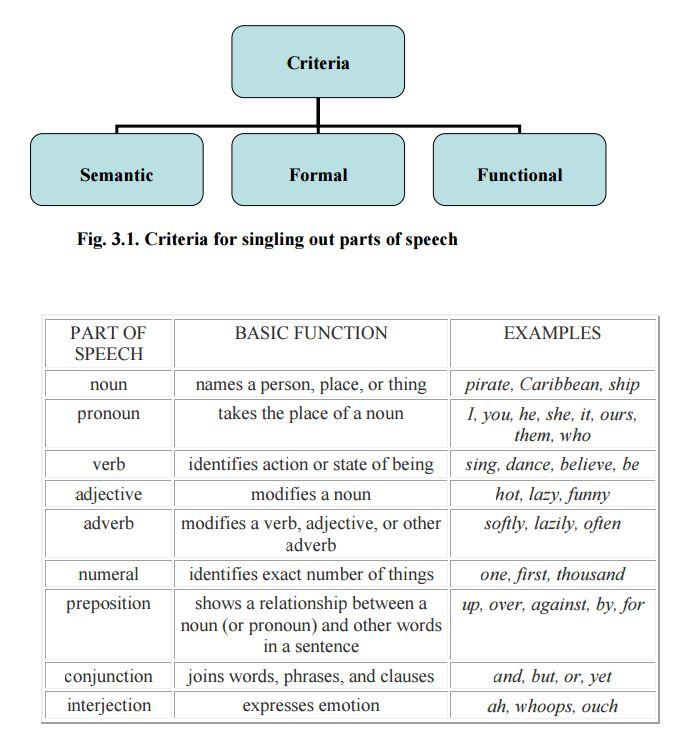

Categorial

meaning of English nouns. Their lexical / grammatical subclasses and

morphemic structure.

In

English, the noun is characterized by the categorial meaning

of substantivity or thingnesswhich is perceived in any noun

irrespective of the form and lexical meaning: e.g.worker,

teacher, doctor as doer of action; book,

chair, house as a separate thing; rain,

water, snow as natural phenomenon; love,

beauty, generosity as an abstract notion, and so on.

The main paradigmatic classes are found possible to

distinguish:commonnouns andpropernouns.

Common

nouns:

Concrete –

denoting single physical objects (animate or inanimate) having a

certain shape and measurements (e.g. table, pupil,

lamp, dog);

Collective –

denoting a group of objects (animate or inanimate) or paired objects

(e.g. family, crew, delegation, government staff,

jury, jeans, earrings, trousers);

Mass – denoting

a physical substance having no particular shape or measurements

(e.g. bread, sugar, copper, wine, snow, air,

milk);

Abstract –

denoting abstracted states, qualities, feelings (e.g. kindness,

adoration, length, knowledge, delight, confidence, experience).

As

far as proper nounsare concerned,

they split into some common subclasses as well indicating names

of people, nationalities(the

British, Ukrainians, Russian), family names

(Byron, Adams, Newton), geographical

names(the Black Sea, Chicago, Moscow, the Pacific

ocean), names of companies, hotels, newspapers,

journals (Ford, the Daily News, the Hilton).

There

is some peculiarity in the realization of the meaning of number and

quantity in some groups of nouns in English. Firstly, a noun with the

same form can have different kinds of meanings and, therefore, can

function differently: concrete/abstract: a

beauty – beauty, красавица – красота; an

authority – authority, влиятельный человек –

влияние; a witness – witness, свидетель –

свидетельство; concrete

thing/material: a lemon – lemon,

лимон – сок; a chicken – chicken, цыпленок –

мясо; an iron – iron, утюг – железо; a wood –

wood, лес – древесина. Secondly, collective nouns may

be used both in singular and in plural (when the constituent members

of these collective nouns are meant): e.g. The

crew are operating perfectly / The crew is excellent. The family go

on holiday every summer / His family is not big.

Taking

into account the substantive featuring of a noun, it is possible to

identify its functional role in

forming a sentence pattern: subject(The

company is based in the capital

city), object(We

visited museums), predicative (He

is anoffice worker), attribute(I

like sea coast villages), adverbial

modifier (There were a lot of people at

the airport).

As

a part of speech the noun is described in its peculiarity as a word

with a specific morphemic structurecreated with

noun-forming derivational means, among

themaffixationandcompounding:

prefixes:

co-, ex-, over-, post-, under-, dis-, im-, un-:

e.g. co-operation,

ex-president, overeating, underestimation, postgraduate,

disagreement, impossibility, unimportance;

suffixes:

-ee, -er, -age, -ance, -tion, -ence, -ment, -cy, -ity, -hood, -ness,

-ship:

e.g. employee,

worker, breakage, annoyance, organization, preference, amazement,

fluency, popularity, childhood, kindness, friendship;

compounding:

adjective

+ noun: e.g. greenhouse, heavyweight, blackboard,

self-confidence, rush hours, safety belt;

noun

+ noun: e.g. cupboard, rainforest, countryside, chairman,

teapot, earthquake, saucepan;

gerund

+ noun: e.g. frying pan, drinking water, shaving cream,

working hours, chewing gum, writing paper, walking stick.

-

Morphological

categories of English nouns; the problematic status of gender

Morphological

features of the noun. In accordance with the morphological

structure

of the stems all nouns can be classified into: simple, derived (stem

+affix, affix + stem – thingness); compound (stem+ stem –

armchair ) and

composite

(the Hague). The noun has morphological categories of number and

case.

Some scholars admit the existence of the category of gender.

Gender.

In

Indo-European languages the category of gender is presented with

flexions.

It is not based on sex distinction, but it is purely grammatical.

According

to some language analysts (B.Ilyish, F.Palmer,

and

E.Morokhovskaya),

nouns have no category of gender in Modern English. Prof.

Ilyish

states that not a single word in Modern English shows any

peculiarities in its

morphology

due to its denoting male or female being. Thus, the words husband

and

wife do not show any difference in their forms due to peculiarities

of their

lexical

meaning. The difference between such nouns as actor and actress is a

purely

lexical one.

Gender

distinctions in English are marked for a limited number of nouns. In

present-day

English there are some morphemes which present differences between

masculine

and feminine (waiter – waitress, widow – widower). This

distinction is

not

grammatically universal. Only a limited number of words are

marked

as belonging to masculine, feminine or neuter. The morpheme on which

the

distinction between masculine and feminine is based in English is a

word-

building

morpheme, not form-building.

Still,

other scholars (M.Blokh, John Lyons) admit the existence of the

category

of gender. Prof. Blokh states that the existence of the category of

gender

in

Modern English can be proved by the correlation of nouns with

personal

pronouns

of the third person (he, she, it). Accordingly, there are three

genders in

English:

the neuter (non-person) gender, the masculine gender, the feminine

gender.

-

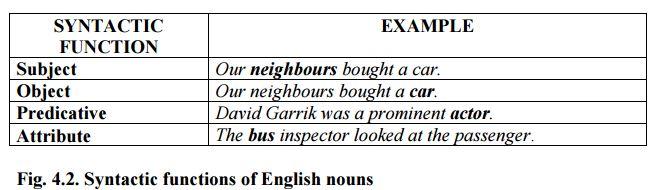

Syntactic

functions of the English noun.

Syntactic

features of the noun. The noun can be used in the sentence in all

syntactic

functions but predicate. Speaking about noun combinability, we can

say

that

it can go into right-hand and left-hand connections with practically

all parts of

speech.

That is why practically all parts of speech but the verb can act as

noun

determiners.

However, the most common noun determiners are considered to be

articles,

pronouns, numerals, adjectives and nouns themselves in the common and

genitive

case.

-

The

category of case of English nouns. Meaning of case (R.Quirk et al).

The six cases of nouns (Charles Fillmore).

is

the morphological category of the noun manifested in the forms of

noun declension and showing the relations of the nounal referent to

other objects and phenomena. is a very speculative issue,

so

different scholars stick to a different number of cases. The

following four approaches, advanced at various times by different

scholars

Theory

of positional cases J.

C. Nesfield, M. Deutchbein,

M.

Bryant et

al follow the patterns of classical Latin grammar, distinguishing

-

NOMINATIVE

(case corresponds with the subject), -

GENITIVE,

DATIVE

(indirect object),

-

ACCUSATIVE

(direct object),

-

VOCATIVE

(with the address). -

“The

theory of positional cases” presents an obvious confusion of the

formal, morphological characteristics of the noun and its

functional, syntactic features.

Theory

of prepositional cases

(G.

Curme)

-

Latin-oriented,

dased on old school grammar traditions: treats the combinations of

nouns with prepositions as specific analytical case forms, -

e.g.:

the DATIVE case is expressed by nouns with the prepositions ‘to’

and

‘for’, -

the

GENITIVE case by nouns with the preposition ‘of’,

the instrumental case by nouns with the preposition ‘with’,

e.g.: for

the girl, of the girl, with a key. -

Theory

of limited case H.

Sweet, O. Jespersen,

developed by Russian linguists A.

Smirnitsky, L. Barkhudarov

-

the

most widely accepted theory of case in English -

The

category of case is realized in full in animate nouns and

restrictedly in inanimate nouns in English, hence the name – “the

theory of limited case” -

the

category of case is expressed by the opposition of two forms: the

first form, “the

genitive case”,

is the strong member of the opposition, marked by the postpositional

element ‘–s’

after

an apostrophe in the singular and just an apostrophe in the plural;

the second, unfeatured form is the weak member of the opposition

and is usually referred to as “the

common case”

(“non-genitive”).

-

“the

theory of the possessive postposition” G. N. Vorontsova, A. M.

Mukhin -

The

main arguments to support this point: first, the postpositional

element ‘s

is not only used with words, but also with the units larger than the

word, with word-combinations and even sentences, e.g.: his

daughter Mary’s arrival, the man I saw yesterday’s face

In

present-day linguistics case is used in two senses: 1) semantic, or

logic, and 2) syntactic.

The semantic case concept was

developed by C. J. Fillmore in the late 1960s. Ch. Fillmore

ntroduced syntactic-semantic classification of cases. They show

relations in the so-called deep structure of the sentence. According

to him, verbs may stand to different relations to nouns. There are 6

cases:

1.

Agentive Case (A) John opened the door;

2.

Instrumental case (I) The key opened the door; John used the key to

open the door;

3.

Dative Case (D) John believed that he would win (the case of the

animate being affected by the state of action identified by the

verb);

4.

Factitive Case (F) The key was damaged (the result of the action or

state identified by the verb);

5.

Locative Case (L) Chicago is windy;

6.

Objective case (O) John stole the book.

Case

expresses the relation of a word to another word in the word-group or

sentence (my sister’s coat). The category of case correlates with

the objective category of possession. The case category in English is

realized through the opposition: The Common Case :: The Possessive

Case (sister :: sister’s). However, in modern linguistics the term

“genitive case” is used instead of the “possessive case”

because the meanings rendered by the “`s” sign are not only those

of possession. The scope of meanings rendered by the Genitive Case is

the following:

1.

Possessive Genitive : Mary’s father – Mary has a father,

2.

Subjective Genitive: The doctor’s arrival – The doctor has

arrived,

3.

Objective Genitive : The man’s release – The man was released,

4.

Genitive of origin: the boy’s story – the boy told the story,

5.

Descriptive Genitive: children’s books – books for children

6.

Genitive of measure and partitive genitive: a mile’s distance, a

day’s trip

7.

Appositive genitive: the city of London.

-

Categorial

status of English articles.

The

question is whether the article is a separate part of speech (i.e. a

word) or a word-morpheme. If we treat the article as a word, we shall

have to admit that English has only two articles — the and a/an. But

if we treat the article as a word- morpheme, we shall have three

articles — the, a/an,

B.Ilyish

(1971:57) thinks that the choice between the two alternatives remains

a matter of opinion. M.Blokh (op. cit., 85) regards the article as a

special type of grammatical auxiliary. Linguists are only agreed on

the function of the article: the article is a determiner, or a

restricter.

The

articles, according to some linguists, do not form a grammatical

category. The articles, they argue, do not belong to the same lexeme,

and they do not have meaning common to them: a/an has the meaning of

oneness, not found in the, which has a demonstrative meaning.

If

we treat the article as a morpheme, then we shall have to set up a

grammatical category in the noun, the category of determination. This

category will have to have all the characteristic features of a

grammatical category: common meaning + distinctive meaning. So what

is common to a room and the room? Both nouns are restricted in

meaning, i.e. they refer to an individual member of the class ‘room’.

What makes them distinct is that a room has the feature [-Definite],

while the room has the feature [+Definite]. In this opposition the

definite article is the strong member and the indefinite article is

the weak member.