Начиная с Microsoft Office 2007, в Microsoft Office используются форматы файлов на основе XML, например DOCX, XLSX и PPTX. Эти форматы и расширения имен файлов применяются к Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel и Microsoft PowerPoint. В этой статье описаны основные преимущества формата, описаны расширения имен файлов и описано, как можно делиться файлами Office с людьми, которые используют более ранние версии Office.

В этой статье

Каковы преимущества форматов Open XML?

Что такое расширения имен XML-файлов?

Можно ли использовать одни и те же файлы в разных версиях Office?

Каковы преимущества форматов Open XML?

Форматы Open XML имеют множество преимуществ не только для разработчиков и их решений, но и для отдельных людей и организаций любого размера.

-

Сжатие файлов Файлы сжимаются автоматически и в некоторых случаях могут быть на 75 процентов меньше. Формат Open XML использует технологию zip-сжатия для хранения документов, что позволяет сэкономить место на диске, необходимое для хранения файлов, и уменьшает пропускную способность, необходимую для отправки файлов по электронной почте, по сетям и через Интернет. Когда вы открываете файл, он автоматически обновляется. При сохранение файла он автоматически застекается снова. Для открытия и закрытия файлов в Office не нужно устанавливать специальные почтовые Office.

-

Улучшенные возможности восстановления поврежденных файлов. Файлы имеют модульную структуру, поэтому различные компоненты данных файла хранятся отдельно друг от друга. Это позволяет открывать файлы даже в том случае, если компонент в файле (например, диаграмма или таблица) поврежден.

-

Поддержка расширенных функций Многие из расширенных Microsoft 365 требуют, чтобы документ хранился в формате Open XML. Например, автоскрытиеи проверка доступности (вдвух примерах) можно работать только с файлами, которые хранятся в современном формате Open XML.

-

Улучшенная конфиденциальность и дополнительный контроль над персональными данными. К документам можно делиться конфиденциально, так как личные сведения и конфиденциальные бизнес-данные, такие как имена авторов, комментарии, отслеживаемые изменения и пути к файлам, можно легко найти и удалить с помощью инспектора документов.

-

Улучшенная интеграция и совместимость бизнес-данных. Использование форматов Open XML в качестве основы для обеспечения взаимосвязи данных в наборе продуктов Office означает, что документы, книги, презентации и формы могут быть сохранены в формате XML, который доступен для использования и лицензирования бесплатно. Office также поддерживает определяемую клиентом схему XML, улучшающую существующие Office типов документов. Это означает, что клиенты могут легко разблокировать информацию в существующих системах и действовать с ней в Office программах. Сведения, которые создаются в Office могут быть легко использованы другими бизнес-приложениями. Все, что нужно для открытия и редактирования файла Office, — это с помощью ZIP-редактора и редактора XML.

-

Упрощенное обнаружение документов, содержащих макросы. Файлы, сохраненные с использованием стандартного суффикса x (например, .docx, .xlsx и .pptx), не могут содержать макрос Visual Basic для приложений (VBA) и макрос XLM. Макросами могут быть только файлы, расширение имени которых заканчивается на «m» (например, DOCM, XLSM и PPTM).

Прежде чем сохранять файл в двоичном формате, ознакомьтесь со статьей Могут ли разные версии Office одинаковыми файлами?

Как преобразовать файл из старого двоичного формата в современный формат Open XML?

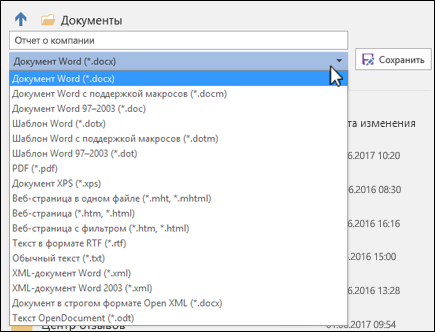

Откройте файл в Приложение Office выберите файл > Сохранить как (или Сохранить копию,если файл хранится в OneDrive или SharePoint) и убедитесь, что для типа Сохранить как за установлен современный формат.

При этом будет создаваться новая копия файла в формате Open XML.

Что такое расширения имен XML-файлов?

По умолчанию документы, книги и презентации, которые вы создаете в Office, сохраняются в формате XML с расширениями имен файлов, которые добавляют «x» или «м» к уже знакомым расширениям имен файлов. Знак «x» означает XML-файл, в котором нет макроса, а «м» — XML-файл, содержащий макрос. Например, при сохранение документа в Word по умолчанию используется расширение .docx имени файла, а не .doc файла.

При сохранение файла в виде шаблона вы видите такое же изменение. Расширение шаблона, используемее в более ранних версиях, уже существует, но теперь в его конце есть «x» или «м». Если файл содержит код или макрос, его необходимо сохранить с помощью нового формата XML-файла с поддержкой макроса, который добавляет в расширение файла «м» для макроса.

В следующих таблицах перечислить все расширения имен файлов по умолчанию в Word, Excel и PowerPoint.

Word

|

Тип XML-файла |

Расширение |

|

Документ |

DOCX |

|

Документ с поддержкой макросов |

DOCM |

|

Шаблон |

DOTX |

|

Шаблон с поддержкой макросов |

DOTM |

Excel

|

Тип XML-файла |

Расширение |

|

Книга |

XLSX |

|

Книга с поддержкой макросов |

XLSM |

|

Шаблон |

XLTX |

|

Шаблон с поддержкой макросов |

XLTM |

|

Двоичная книга (не XML) |

XLSB |

|

Надстройка с поддержкой макросов |

XLAM |

PowerPoint

|

Тип XML-файла |

Расширение |

|

Презентация |

PPTX |

|

Презентация с поддержкой макросов |

PPTM |

|

Шаблон |

POTX |

|

Шаблон с поддержкой макросов |

POTM |

|

Надстройка с поддержкой макросов |

PPAM |

|

Демонстрация |

PPSX |

|

Демонстрация с поддержкой макросов |

PPSM |

|

Слайд |

SLDX |

|

Слайд с поддержкой макросов |

SLDM |

|

Тема Office |

THMX |

Можно ли использовать одни и те же файлы в разных версиях Office?

Office позволяет сохранять файлы в форматах Open XML и в двоичном формате файлов более ранних версий Office и включает в себя проверку совместимости и конвертеры файлов, позволяющие совместно использовать файлы в разных Office.

Открытие существующих файлов в Office Вы можете открыть файл, созданный в более ранней версии Office, а затем сохранить его в существующем формате. Так как, возможно, вы работаете над документом совместно с человеком, использующим более ранную версию Office, Office использует проверку совместимости, которая проверяет, что функция, которая не поддерживается в предыдущих версиях Office, не поддерживается. Когда вы сохраняете файл, проверка совместимости сообщает вам об этих функций, а затем позволяет удалить их, прежде чем продолжить сохранение.

Office Open XML (also informally known as OOXML) is a zipped, XML-based file format developed by Microsoft for representing spreadsheets, charts, presentations and word processing documents. The format was initially standardized by the Ecma (as ECMA-376), and by the ISO and IEC (as ISO/IEC 29500) in later versions.

Contents

- 1 Is XML same as docx?

- 2 How do I open an XML document in word?

- 3 Can you create a XML document in word?

- 4 What are XML documents?

- 5 How do I convert XML to word?

- 6 What is XML used for?

- 7 What is an XML file and how do I open it?

- 8 What is an Office Open XML document?

- 9 Does Microsoft Office use XML?

- 10 How do I add an XML file to Word?

- 11 How do XML documents work?

- 12 What is XML with example?

- 13 How do you represent an XML document?

- 14 How do I convert XML to text?

- 15 How do I open an XML file in Windows 10?

- 16 How do I edit an XML document?

- 17 What are the benefits of using XML?

- 18 What are the main features of XML?

- 19 Is XML still relevant 2021?

- 20 How do I open a XML file in Chrome?

Is XML same as docx?

DOCX was originally developed by Microsoft as an XML-based format to replace the proprietary binary format that uses the . doc file extension. Since Word 2007, DOCX has been the default format for the Save operation.

How do I open an XML document in word?

#1) Open Windows Explorer and browse to the location where the XML file is located. We have browsed to the location of our XML file MySampleXML as seen below. #2) Now right-click over the file and select Open With to choose Notepad or Microsoft Office Word from the list of options available to open the XML file.

Can you create a XML document in word?

Creating an XML Document.You can open and edit an XML file in Word, in the same way you can an HTML file. You can also open it in an XML editor such as XMetal, or as a plain text file in a text editor such as Notepad.

What are XML documents?

XML documents are strictly text files. In the context of data transport, the phrase “XML document” refers to a file or data stream containing any form of structured data.XML documents contain only markup and content. All of the rules and semantics of the document are defined by the applications that process them.

How do I convert XML to word?

About This Article

- Open Word.

- Click File.

- Click Save As.

- Click Browse.

- Select Word Document from the “Save as type” drop-down.

- Click Save.

What is XML used for?

The Extensible Markup Language (XML) is a simple text-based format for representing structured information: documents, data, configuration, books, transactions, invoices, and much more. It was derived from an older standard format called SGML (ISO 8879), in order to be more suitable for Web use.

What is an XML file and how do I open it?

XML files are encoded in plaintext, so you can open them in any text editor and be able to clearly read it. Right-click the XML file and select “Open With.” This will display a list of programs to open the file in. Select “Notepad” (Windows) or “TextEdit” (Mac).

What is an Office Open XML document?

Office Open XML, also known as OpenXML or OOXML, is an XML-based format for office documents, including word processing documents, spreadsheets, presentations, as well as charts, diagrams, shapes, and other graphical material.

Does Microsoft Office use XML?

Starting with the 2007 Microsoft Office system, Microsoft Office uses the XML-based file formats, such as . docx, . xlsx, and .These formats and file name extensions apply to Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft PowerPoint.

How do I add an XML file to Word?

To add an XMLNode control to a document

- In the document in the Visual Studio designer, on the ribbon, click the Developer tab.

- In the XML group, click Schema.

- Click the XML Schema tab.

- Click Add Schema.

- Select an XML schema that contains non-repeating schema elements from the Add Schema dialog box and click Open.

How do XML documents work?

Right-click the XML file you want to open, point to “Open With” on the context menu, and then click the “Notepad” option. Note: We’re using Windows examples here, but the same holds true for other operating systems. Look for a good third-party text editor that is designed to support XML files.

What is XML with example?

Extensible Markup Language (XML) is a markup language that defines a set of rules for encoding documents in a format that is both human-readable and machine-readable.

XML.

| Filename extension | .xml |

|---|---|

| Developed by | World Wide Web Consortium |

| Type of format | Markup language |

| Extended from | SGML |

How do you represent an XML document?

An XML document consists of three parts, in the order given:

- An XML declaration (which is technically optional, but recommended in most normal cases)

- A document type declaration that refers to a DTD (which is optional, but required if you want validation)

- A body or document instance (which is required)

How do I convert XML to text?

How to Convert XML to TXT with Doxillion Document Converter Software

- Download Doxillion Document Converter Software. Download Doxillion Document Converter Software.

- Import XML Files into the Program.

- Choose an Output Folder.

- Set the Output Format.

- Convert XML to TXT.

How do I open an XML file in Windows 10?

Replies (48)

- Type Default programs in the search bar on Windows 10.

- Associate a file type or protocol with a program under Choose the program that Windows use by default in the Default Program Window.

- Select the . xml file type in the Associate a file type or protocol with a program Window and click on Ok.

How do I edit an XML document?

Open the file you wish to edit by double clicking the file name. The file will open and display the existing code. Edit your XML file. Review your editing.

What are the benefits of using XML?

Advantages of XML

- XML uses human, not computer, language. XML is readable and understandable, even by novices, and no more difficult to code than HTML.

- XML is completely compatible with Java™ and 100% portable. Any application that can process XML can use your information, regardless of platform.

- XML is extendable.

What are the main features of XML?

A basic summary of the main features of XML follows:

- Excellent for handling data with a complex structure or atypical data.

- Data described using markup language.

- Text data description.

- Human- and computer-friendly format.

- Handles data in a tree structure having one-and only one-root element.

Is XML still relevant 2021?

XML is used extensively in today’s ‘e’ world – banking services, online retail stores, integrating industrial systems, etc. One can put as many different types of information in the XML and it still remains simple.

How do I open a XML file in Chrome?

Just about every browser can open an XML file. In Chrome, just open a new tab and drag the XML file over. Alternatively, right click on the XML file and hover over “Open with” then click “Chrome”. When you do, the file will open in a new tab.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Filename extension | .XML (XML document) |

|---|---|

| Developed by | Microsoft |

| Type of format | Document file format |

| Extended from | XML, DOC |

| Filename extension | .VDX (XML Drawing),.VSX (XML Stencil),.VTX (XML Template) |

|---|---|

| Developed by | Microsoft |

| Type of format | Diagramming vector graphics |

| Extended from | XML, VSD, VSS, VST |

| Filename extension | .XML (XML Spreadsheet) |

|---|---|

| Developed by | Microsoft |

| Type of format | Spreadsheet |

| Extended from | XML, XLS |

The Microsoft Office XML formats are XML-based document formats (or XML schemas) introduced in versions of Microsoft Office prior to Office 2007. Microsoft Office XP introduced a new XML format for storing Excel spreadsheets and Office 2003 added an XML-based format for Word documents.

These formats were succeeded by Office Open XML (ECMA-376) in Microsoft Office 2007.

File formats[edit]

- Microsoft Office Word 2003 XML Format — WordProcessingML or WordML (.XML)

- Microsoft Office Excel 2002 and Excel 2003 XML Format — SpreadsheetML (.XML)

- Microsoft Office Visio 2003 XML Format — DataDiagramingML (.VDX, .VSX, .VTX)

- Microsoft Office InfoPath 2003 XML Format — XML FormTemplate (.XSN) (Compressed XML templates in a Cabinet file)

- Microsoft Office InfoPath 2003 XML Format — XMLS FormTemplate (.XSN) (Compressed XML templates in a Cabinet file)

Limitations and differences with Office Open XML[edit]

Besides differences in the schema, there are several other differences between the earlier Office XML schema formats and Office Open XML.

- Whereas the data in Office Open XML documents is stored in multiple parts and compressed in a ZIP file conforming to the Open Packaging Conventions, Microsoft Office XML formats are stored as plain single monolithic XML files (making them quite large, compared to OOXML and the Microsoft Office legacy binary formats). Also, embedded items like pictures are stored as binary encoded blocks within the XML. In case of Office Open XML, the header, footer, comments of a document etc. are all stored separately.

- XML Spreadsheet documents cannot store Visual Basic for Applications macros, auditing tracer arrows, chart and other graphic objects, custom views, drawing object layers, outlining, scenarios, shared workbook information and user-defined function categories.[1] In contrast, the newer Office Open XML formats support full document fidelity.

- Poor backward compatibility with the version of Word/Excel prior to the one in which they were introduced. For example, Word 2002 cannot open Word 2003 XML files unless a third-party converter add-in is installed.[2] Microsoft has released a Word 2003 XML Viewer which allows WordProcessingML files saved by Word 2003 to be viewed as HTML from within Internet Explorer.[3] For Office Open XML, Microsoft provides converters for Office 2003, Office XP and Office 2000.

- Office Open XML formats are also defined for PowerPoint 2007, equation editing (Office MathML), vector drawing, charts and text art (DrawingML).

Word XML format example[edit]

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" standalone="yes"?> <?mso-application progid="Word.Document"?> <w:wordDocument xmlns:w="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2003/wordml" xmlns:wx="http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/word/2003/auxHint" xmlns:o="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" w:macrosPresent="no" w:embeddedObjPresent="no" w:ocxPresent="no" xml:space="preserve"> <o:DocumentProperties> <o:Title>This is the title</o:Title> <o:Author>Darl McBride</o:Author> <o:LastAuthor>Bill Gates</o:LastAuthor> <o:Revision>1</o:Revision> <o:TotalTime>0</o:TotalTime> <o:Created>2007-03-15T23:05:00Z</o:Created> <o:LastSaved>2007-03-15T23:05:00Z</o:LastSaved> <o:Pages>1</o:Pages> <o:Words>6</o:Words> <o:Characters>40</o:Characters> <o:Company>SCO Group, Inc.</o:Company> <o:Lines>1</o:Lines> <o:Paragraphs>1</o:Paragraphs> <o:CharactersWithSpaces>45</o:CharactersWithSpaces> <o:Version>11.6359</o:Version> </o:DocumentProperties> <w:fonts> <w:defaultFonts w:ascii="Times New Roman" w:fareast="Times New Roman" w:h-ansi="Times New Roman" w:cs="Times New Roman" /> </w:fonts> <w:styles> <w:versionOfBuiltInStylenames w:val="4" /> <w:latentStyles w:defLockedState="off" w:latentStyleCount="156" /> <w:style w:type="paragraph" w:default="on" w:styleId="Normal"> <w:name w:val="Normal" /> <w:rPr> <wx:font wx:val="Times New Roman" /> <w:sz w:val="24" /> <w:sz-cs w:val="24" /> <w:lang w:val="EN-US" w:fareast="EN-US" w:bidi="AR-SA" /> </w:rPr> </w:style> <w:style w:type="paragraph" w:styleId="Heading1"> <w:name w:val="heading 1" /> <wx:uiName wx:val="Heading 1" /> <w:basedOn w:val="Normal" /> <w:next w:val="Normal" /> <w:rsid w:val="00D93B94" /> <w:pPr> <w:pStyle w:val="Heading1" /> <w:keepNext /> <w:spacing w:before="240" w:after="60" /> <w:outlineLvl w:val="0" /> </w:pPr> <w:rPr> <w:rFonts w:ascii="Arial" w:h-ansi="Arial" w:cs="Arial" /> <wx:font wx:val="Arial" /> <w:b /> <w:b-cs /> <w:kern w:val="32" /> <w:sz w:val="32" /> <w:sz-cs w:val="32" /> </w:rPr> </w:style> <w:style w:type="character" w:default="on" w:styleId="DefaultParagraphFont"> <w:name w:val="Default Paragraph Font" /> <w:semiHidden /> </w:style> <w:style w:type="table" w:default="on" w:styleId="TableNormal"> <w:name w:val="Normal Table" /> <wx:uiName wx:val="Table Normal" /> <w:semiHidden /> <w:rPr> <wx:font wx:val="Times New Roman" /> </w:rPr> <w:tblPr> <w:tblInd w:w="0" w:type="dxa" /> <w:tblCellMar> <w:top w:w="0" w:type="dxa" /> <w:left w:w="108" w:type="dxa" /> <w:bottom w:w="0" w:type="dxa" /> <w:right w:w="108" w:type="dxa" /> </w:tblCellMar> </w:tblPr> </w:style> <w:style w:type="list" w:default="on" w:styleId="NoList"> <w:name w:val="No List" /> <w:semiHidden /> </w:style> </w:styles> <w:docPr> <w:view w:val="print" /> <w:zoom w:percent="100" /> <w:doNotEmbedSystemFonts /> <w:proofState w:spelling="clean" w:grammar="clean" /> <w:attachedTemplate w:val="" /> <w:defaultTabStop w:val="720" /> <w:punctuationKerning /> <w:characterSpacingControl w:val="DontCompress" /> <w:optimizeForBrowser /> <w:validateAgainstSchema /> <w:saveInvalidXML w:val="off" /> <w:ignoreMixedContent w:val="off" /> <w:alwaysShowPlaceholderText w:val="off" /> <w:compat> <w:breakWrappedTables /> <w:snapToGridInCell /> <w:wrapTextWithPunct /> <w:useAsianBreakRules /> <w:dontGrowAutofit /> </w:compat> </w:docPr> <w:body> <wx:sect> <w:p> <w:r> <w:t>This is the first paragraph</w:t> </w:r> </w:p> <wx:sub-section> <w:p> <w:pPr> <w:pStyle w:val="Heading1" /> </w:pPr> <w:r> <w:t>This is a heading</w:t> </w:r> </w:p> <w:sectPr> <w:pgSz w:w="12240" w:h="15840" /> <w:pgMar w:top="1440" w:right="1800" w:bottom="1440" w:left="1800" w:header="720" w:footer="720" w:gutter="0" /> <w:cols w:space="720" /> <w:docGrid w:line-pitch="360" /> </w:sectPr> </wx:sub-section> </wx:sect> </w:body> </w:wordDocument>

Excel XML spreadsheet example[edit]

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <?mso-application progid="Excel.Sheet"?> <Workbook xmlns="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:spreadsheet" xmlns:x="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:excel" xmlns:ss="urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:spreadsheet" xmlns:html="https://www.w3.org/TR/html401/"> <Worksheet ss:Name="CognaLearn+Intedashboard"> <Table> <Column ss:Index="1" ss:AutoFitWidth="0" ss:Width="110"/> <Row> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">ID</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Project</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Reporter</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Assigned To</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Priority</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Severity</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Reproducibility</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Product Version</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Category</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Date Submitted</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">OS</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">OS Version</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Platform</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">View Status</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Updated</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Summary</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Status</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Resolution</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">Fixed in Version</Data></Cell> </Row> <Row> <Cell><Data ss:Type="Number">0000033</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">CognaLearn Intedashboard</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">janardhana.l</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">normal</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">text</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">always</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">GUI</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">2016-10-14</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">public</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">2016-10-14</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">IE8 browser_Modules screen tool tip text is shown twice</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">new</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String">open</Data></Cell> <Cell><Data ss:Type="String"></Data></Cell> </Row> </Table> </Worksheet> </Workbook>

See also[edit]

- List of document markup languages

- Comparison of document markup languages

References[edit]

- ^ «Features and limitations of XML Spreadsheet format (broken)». Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ «Polar WordML add-in (broken)». Archived from the original on 2009-04-11. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ Word 2003 XML Viewer

- Overview of Office 2003 Developer Technologies

- Office 2003 XML. ISBN 0-596-00538-5

External links[edit]

- MSDN: XML Spreadsheet Reference

- MSDN: Word 2003 XML Reference

- Lawsuit about XML patent

Show All

About XML documents in Word

Note XML features, except for saving documents as XML with the Word XML schema, are available only in Microsoft Office Professional Edition 2003 and stand-alone Microsoft Office Word 2003.

Why XML?

Extensible Markup Language (XML) enables you to organize and work with documents and data in ways that were previously impossible or very difficult. By using custom XML schemas, you can now identify and extract specific pieces of business data from ordinary business documents.

For example, an invoice that contains the name and address of a customer or a report that contains last quarter’s financial results are no longer static documents. The information they contain can be passed to a database or reused elsewhere, outside of the documents.

The ability to save a Microsoft Word document in standard XML format helps separate its content from the confines of the document. The content becomes available for automated data-mining and repurposing processes. The content can easily be searched and even modified by processes other than Word, such as server-based data processing.

Because Word is capable of representing its documents as XML, automated server-based processes can now generate Word documents on the fly by pulling together data from various sources. Such a document could then easily be updated on a regular basis, eliminating the manual search for relevant data and unnecessary retyping.

Word and XML

Microsoft Word enables you to work with XML documents in two ways:

- Use the Word XML schema You can create a document in Word as you normally would and then save it as an XML document. Word uses its own XML schema, WordML, to apply XML tags that store information, such as file properties, and define the structure of the document, such as its paragraphs, headings, and tables. Word also uses XML tags to store formatting and layout information, according to the Word XML schema.

- Use any XML schema You can create or open a document in Word, attach any custom XML schema to it, and apply XML tags to the content of the document. When you save this document as an XML document, the XML tags define the structure of the document in terms of the XML schema that is attached to it.

When you save the document, by default both the Word schema and the custom schema are attached to the document, preserving the data as defined by the custom schema and the rich formatting as defined by the Word XML schema. You also have the option of saving the document as data only, according to the custom schema.

Whether you use the built-in Word XML schema for a Word document structure or attach your own schema for a structure that is more suitable for your business, any software that can parse XML can read and process the data in a document that you save as an XML document (.xml file).

For example, if the custom schema is for résumé data, the XML tags in the document will define the structure of the document in terms of name, address, work experience, education, and so on. When you save the document, you have both a richly formatted document that looks professional when printed and a data file that can be processed by any program that can read XML.

You can also store XML data in a document that you save as a Word document (.doc) or template (.dot). However, only Word will be able to read or process the XML.

XML tagging

When a custom XML schema is attached to a document, the XML Structure task pane provides a list of elements that are defined in the schema. You apply XML tags to the document by selecting document content and then choosing an element from the list. If the schema defines attributes for an element, you can specify these as well in the XML Structure task pane.

Note You can attach more than one schema to a document. Elements from all attached schemas are available in the list of elements in the XML Structure task pane.

A check box on the pane enables you to see the XML tags inline, in the context of the document.

If the structure of the document violates the rules of the schema, a purple wavy line marks the spot in the document, and the XML Structure task pane reports the violation.

XSL Transformations

Upon opening and saving XML documents, you can apply Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformation (XSLT) files that render the XML data in a particular format. For example, you could have one XSLT that presents data as a specification and another XSLT that presents the same data as a parts list, where quantities and prices are calculated.

XSLTs applied when opening a document

An XML document may have more than one XSLT associated with it. When this is the case, you must select the XSLT that you want to use to display the document. You do this in the XML Document pane, where the available XSLTs (data views) are listed.

If no XSLT is associated with an XML document, then Word opens it using its default XSLT, or «Data only view.»

If the Word XML schema is attached to the document, Word opens the document without applying an XSLT, even if one is associated with the document.

Note Rather than applying an XSLT manually, you can define solutions that associate XSLTs with certain types of XML documents. You make this association in the Schema Library, which you can access on the XML Schema tab of the Templates and Add-ins dialog box (Tools menu).

XSLTs applied when saving a document

You can apply an XSLT when you save an XML document by selecting the Apply transform check box and browsing to the XSLT file.

Caution If you apply an XSLT when you save the file, Word discards any data that the XSLT does not use.

With approximately one billion people using Microsoft Office, the DOCX format is the most popular de facto standard for exchanging document files between offices. Its closest competitor — the ODT format — is only supported by Open/LibreOffice and some open source products, making it far from standard. The PDF format is not a competitor because PDFs can’t be edited and they don’t contain a full document structure, so they can only take limited local changes like watermarks, signatures, and the like. This is why most business documents are created in the DOCX format; there’s no good alternative to replace it.

While DOCX is a complex format, you may want to parse it manually for simpler tasks such as indexing, converting to TXT and making other small modifications. I’d like to give you enough information on DOCX internals so you don’t have to reference the ECMA specifications, a massive 5,000 page manual.

The best way to understand the format is to create a simple one-word document with MSWord and observe how editing the document changes the underlying XML. You’ll face some cases where the DOCX doesn’t format properly in MS Word and you don’t know why, or come across instances when it’s not evident how to generate the desired formatting. Seeing and understanding exactly what’s going on in the XML will help that.

I worked for about a year on a collaborative DOCX editor, CollabOffice, and I want to share some of that knowledge with the developer community. In this article I will explain the DOCX file structure, summarising information that is scattered over the internet. This article is an intermediary between the huge, complex ECMA specification and the simple internet tutorials currently available. You can find the files that accompany this article in the toptal-docx project on my github account.

A Simple DOCX file

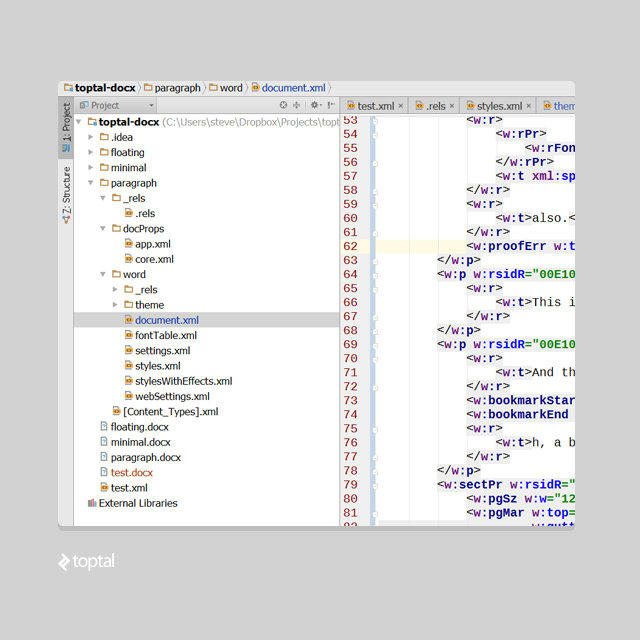

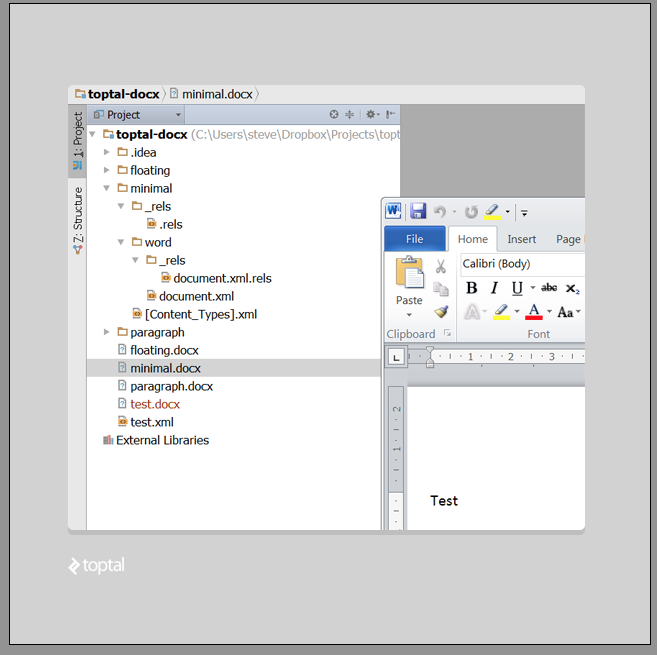

A DOCX file is a ZIP archive of XML files. If you create a new, empty Microsoft Word document, write a single word ‘Test’ inside and unzip it contents, you will see the following file structure:

Even though we’ve created a simple document, the save process in Microsoft Word has generated default themes, document properties, font tables, and so on, in XML format.

All the files inside a DOCX are XML files, even those with the «.rels» extension.

To start, let us remove the unused stuff and focus on document.xml, which contains the main text elements. When you delete a file, make sure you have deleted all the relationship references to it from other the xml files. Here is a code-diff example on how I’ve cleared dependencies to app.xml and core.xml. If you have any unresolved/missing references, MSWord will consider the file broken.

Here’s the structure of our simplified, minimal DOCX document (and here’s the project on github):

Let’s break it down by file from here, from the top:

_rels/.rels

This defines the reference that tells MS Word where to look for the document contents. In this case, it references word/document.xml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?>

<Relationships xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships">

<Relationship Id="rId1" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/officeDocument"

Target="word/document.xml"/>

</Relationships>

_rels/document.xml.rels

This file defines references to resources, such as images, embedded in the document content. Our simple document has no embedded resources, so the relationship tag is empty:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?>

<Relationships xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships">

</Relationships>

[Content_Types].xml

[Content_Types].xml contains information about the types of media inside the document. Since we only have text content, it’s pretty simple:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?>

<Types xmlns="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/content-types">

<Default Extension="rels" ContentType="application/vnd.openxmlformats-package.relationships+xml"/>

<Default Extension="xml" ContentType="application/xml"/>

<Override PartName="/word/document.xml"

ContentType="application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document.main+xml"/>

</Types>

document.xml

Finally, here is the main XML with the document’s text content. I have removed some of namespace declarations for clarity, but you can find the full version of the file in the github project. In that file you’ll find that some of the namespace references in the document are unused, but you shouldn’t delete them because MS Word needs them.

Here’s our simplified example:

<w:document>

<w:body>

<w:p w:rsidR="005F670F" w:rsidRDefault="005F79F5">

<w:r><w:t>Test</w:t></w:r>

</w:p>

<w:sectPr w:rsidR="005F670F">

<w:pgSz w:w="12240" w:h="15840"/>

<w:pgMar w:top="1440" w:right="1440" w:bottom="1440" w:left="1440" w:header="720" w:footer="720"

w:gutter="0"/>

<w:cols w:space="720"/>

<w:docGrid w:linePitch="360"/>

</w:sectPr>

</w:body>

</w:document>

The main node <w:document> represents the document itself, <w:body> contains paragraphs, and nested within <w:body> are page dimensions defined by <w:sectPr>.

<w:rsidR> is an attribute that you can ignore; it’s used by MS Word internals.

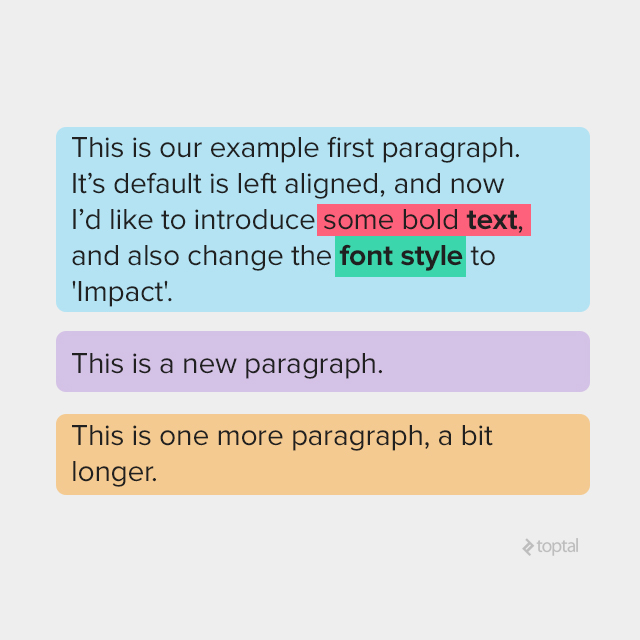

Let’s take a look at a more complex document with three paragraphs. I have highlighted the XML with the same colors on the screenshot from Microsoft Word, so you can see the correlation:

<w:p w:rsidR="0081206C" w:rsidRDefault="00E10CAE"> <w:r> <w:t xml:space="preserve">This is our example first paragraph. It's default is left aligned, and now I'd like to introduce</w:t> </w:r> <w:r> <w:rPr> <w:rFonts w:ascii="Arial" w:hAnsi="Arial" w:cs="Arial"/> <w:color w:val="000000"/> </w:rPr> <w:t>some bold</w:t> </w:r> <w:r> <w:rPr> <w:rFonts w:ascii="Arial" w:hAnsi="Arial" w:cs="Arial"/> <w:b/> <w:color w:val="000000"/> </w:rPr> <w:t xml:space="preserve"> text</w:t> </w:r> <w:r> <w:rPr> <w:rFonts w:ascii="Arial" w:hAnsi="Arial" w:cs="Arial"/> <w:color w:val="000000"/> </w:rPr> <w:t xml:space="preserve">, </w:t> </w:r> <w:proofErr w:type="gramStart"/> <w:r> <w:t xml:space="preserve">and also change the</w:t> </w:r> <w:r w:rsidRPr="00E10CAE"> <w:rPr><w:rFonts w:ascii="Impact" w:hAnsi="Impact"/> </w:rPr> <w:t>font style</w:t> </w:r> <w:r> <w:rPr> <w:rFonts w:ascii="Impact" w:hAnsi="Impact"/> </w:rPr> <w:t xml:space="preserve"> </w:t> </w:r> <w:r> <w:t>to 'Impact'.</w:t></w:r> </w:p> <w:p w:rsidR="00E10CAE" w:rsidRDefault="00E10CAE"> <w:r> <w:t>This is new paragraph.</w:t> </w:r></w:p> <w:p w:rsidR="00E10CAE" w:rsidRPr="00E10CAE" w:rsidRDefault="00E10CAE"> <w:r> <w:t>This is one more paragraph, a bit longer.</w:t> </w:r> </w:p>

Paragraph Structure

A simple document consists of paragraphs, a paragraph consists of runs (a series of text with the same font, color, etc), and runs consist of characters (such as <w:t>).<w:t> tags may have several characters inside, and there might be a few in the same run.

Again, we can ignore <w:rsidR>.

Text properties

Basic text properties are font, size, color, style, and so on. There are about 40 tags that specify text appearance. As you can see in our three paragraph example, each run has its own properties inside <w:rPr>, specifying <w:color>, <w:rFonts> and boldness <w:b>.

An important thing to note is that properties make a distinction between the two groups of characters, normal and complex script (Arabic, for instance), and that the properties have a different tag depending on which type of character it’s affecting.

Most normal script property tags have a matching complex script tag with an added “C” specifying the property is for complex scripts. For example: <w:i> (italic) becomes <w:iCs>, and the bold tag for normal script, <w:b>, becomes <w:bCs> for complex script.

Styles

There’s an entire toolbar in Microsoft Word dedicated to styles: normal, no spacing, heading 1, heading 2, title, and so on. These styles are stored in /word/styles.xml (note: in the first step in our simple example, we removed this XML from DOCX. Make a new DOCX to see this).

Once you have text defined as a style, you will find reference to this style inside the paragraph properties tag, <w:pPr>. Here’s an example where I’ve defined my text with the style Heading 1:

<w:p>

<w:pPr>

<w:pStyle w:val="Heading1"/>

</w:pPr>

<w:r>

<w:t>My heading 1</w:t>

</w:r>

</w:p>

and here is the style itself from styles.xml:

<w:style w:type="paragraph" w:styleId="Heading1">

<w:name w:val="heading 1"/>

<w:basedOn w:val="Normal"/>

<w:next w:val="Normal"/>

<w:link w:val="Heading1Char"/>

<w:uiPriority w:val="9"/>

<w:qFormat/>

<w:rsid w:val="002F7F18"/>

<w:pPr>

<w:keepNext/>

<w:keepLines/>

<w:spacing w:before="480" w:after="0"/>

<w:outlineLvl w:val="0"/>

</w:pPr>

<w:rPr>

<w:rFonts w:asciiTheme="majorHAnsi" w:eastAsiaTheme="majorEastAsia" w:hAnsiTheme="majorHAnsi"

w:cstheme="majorBidi"/>

<w:b/>

<w:bCs/>

<w:color w:val="365F91" w:themeColor="accent1" w:themeShade="BF"/>

<w:sz w:val="28"/>

<w:szCs w:val="28"/>

</w:rPr>

</w:style>

The <w:style/w:rPr/w:b> xpath specifies that the font is bold, and <w:style/w:rPr/w:color> indicates the font color. <w:basedOn> instructs MSWord to use “Normal” style for any missing properties.

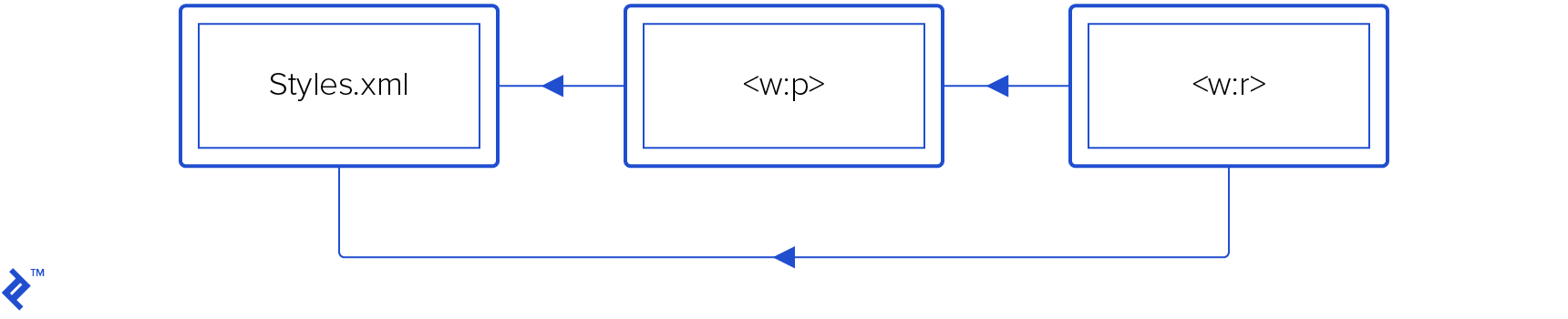

Property Inheritance

Text properties are inherited. A run has its own properties (w:p/w:r/w:rPr/*), but it also inherits properties from paragraph (w:r/w:pPr/*), and both can reference style properties from the /word/styles.xml.

<w:r>

<w:rPr>

<w:rStyle w:val="DefaultParagraphFont"/>

<w:sz w:val="16"/>

</w:rPr>

<w:tab/>

</w:r>

Paragraphs and runs start with default properties: w:styles/w:docDefaults/w:rPrDefault/*

and w:styles/w:docDefaults/w:pPrDefault/*. To get the end result of a character’s properties you should:

- Use default run/paragraph properties

- Append run/paragraph style properties

- Append local run/paragraph properties

- Append result run properties over paragraph properties

When I say “append” B to A, I mean to iterate through all B properties and override all A’s properties, leaving all non-intersecting properties as-is.

One more place where default properties may be located is in the <w:style> tag with w:type="paragraph" and w:default="1". Note, that characters themselves inside a run never have a default style, so <w:style w:type="character" w:default="1"> doesn’t actually affect any text.

1554402290400-dbb29eef3ba6035df7ad726dfc99b2af.png)

Characters in a run can inherit from its paragraph and both can inherit from styles.xml.

Toggle properties

Some of the properties are “toggle” properties, such as <w:b> (bold) or <w:i> (italic); these attributes behave like an XOR operator.

This means if the parent style is bold and a child run is bold, the result will be regular, non-bold text.

You have to do lots of testing and reverse-engineering to handle toggle attributes correctly. Take a look at paragraph 17.7.3 of ECMA-376 Open XML specification to get the formal, detailed rules for toggle properties/

Toggle properties are the most complex for a layouter to handle correctly.

Fonts

Fonts follow the same common rules as other text attributes, but font property default values are specified in a separate theme file, referenced under word/_rels/document.xml.rels like this:

<Relationship Id="rId7" Type="http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/theme" Target="theme/theme1.xml"/>

Based on the above reference, the default font name will be found in word/theme/themes1.xml, inside a <a:theme> tag, a:themeElements/a:fontScheme/a:majorFont or a:minorFont tag.

The default font size is 10 unless the w:docDefaults/w:rPrDefault tag is missing, then it is size 11.

Text alignment

Text alignment is specified by a <w:jc> tag with four w:val modes available: "left", "center", "right" and "both".

"left" is the default mode; text is started at the left of paragraph rectangle (usually the page width). (This paragraph is aligned to the left, which is standard.)

"center" mode, predictably, centers all characters inside the page width. (Again, this paragraph exemplifies centered alignment.)

In "right" mode, paragraph text is aligned to the right margin. (Notice how this text is aligned to the right side.)

"both" mode puts extra spacing between words so that lines get wider and occupy the full paragraph width, with the exception of the last line which is left aligned. (This paragraph is a demonstration of that.)

Images

DOCX supports two sorts of images: inline and floating.

Inline images appear inside a paragraph along with the other characters, <w:drawing> is used instead of using <w:t> (text). You can find image ID with the following xpath syntax:

w:drawing/wp:inline/a:graphic/a:graphicData/pic:pic/pic:blipFill/a:blip/@r:embed

The image ID is used to look up the filename in the word/_rels/document.xml.rels file, and it should point to gif/jpeg file inside word/media subfolder. (See the github project’s word/_rels/document.xml.rels file, where you can see the image ID.)

Floating images are placed relative to paragraphs with text flowing around them. (Here’s th github project sample document with a floating image.)

Floating images use <wp:anchor> instead of <w:drawing>, so if you delete any text inside <w:p>, be careful with the anchors if you don’t want the images removed.

MS Word’s image options refer to image alignment as «text wrapping mode».

Tables

XML tags for tables are similar to HTML table markup– is the same as <table>, matches with <tr>, etc.

<w:tbl>, the table itself, has table properties <w:tblPr>, and each column property is presented by <w:gridCol> inside <w:tblGrid>. Rows follow one by one as <w:tr> tags and each row should have same number of columns as specified in <w:tblGrid>:

<w:tbl>

<w:tblPr>

<w:tblW w:w="5000" w:type="pct" />

</w:tblPr>

<w:tblGrid><w:gridCol/><w:gridCol/></w:tblGrid>

<w:tr>

<w:tc><w:p><w:r><w:t>left</w:t></w:r></w:p></w:tc>

<w:tc><w:p><w:r><w:t>right</w:t></w:r></w:p></w:tc>

</w:tr>

</w:tbl>

Width for table columns can be specified in the <w:tblW> tag, but if you don’t define it MS Word will use its internal algorithms to find the optimal width of columns for the smallest effective table size.

Units

Many XML attributes inside DOCX specify sizes or distances. While they’re integers inside the XML, they all have different units so some conversion is necessary. The topic is a complicated one, so I’d recommend this article by Lars Corneliussen on units in DOCX files. The table he presents is useful, though with a small misprint: inches should be pt/72, not pt*72.

Here’s a cheat sheet:

| COMMON DOCX XML UNIT CONVERSIONS | ||||||

| 20th of a point | Points dxa/20 |

Inches pt/72 |

Centimeters in*2,54 |

Font half size pt/144 |

EMU in*914400 |

|

| Example | 11906 | 595.3 | 8,27… | 21.00086… | 4,135 | 7562088 |

| Tags using this | pgSz/pgMar/w:spacing | w:sz | wp:extent, a:ext |

Tips for Implementing a Layouter

If you want to convert a DOCX file (to PDF, for instance), draw it on canvas, or count number of pages, you’ll have to implement a layouter. A layouter is an algorithm for calculating character positions from a DOCX file.

This is a complex task if you need 100 percent fidelity rendering. The amount of time needed to implement a good layouter is measured in man-years, but if you only need a simple, limited one, it can be done relatively quickly.

A layouter fills a parent rectangle, which is usually a rectangle of the page. It add words from a run one by one. When the current line overflows, it starts a new one. If the paragraph is too high for the parent rectangle, it’s wrapped to the next page.

Here are some important things to keep in mind if you decide to implement a layouter:

- The layouter should take care about text alignment and text floating over images

- It should be capable of handling nested objects, such as nested tables

- If you want to provide full support for such images, you’ll have to implement a layouter with at least two passes, the first step collects floating images’ positions and the second fills empty space with text characters.

- Be aware of indentations and spacings. Each paragraph has spacing before and after, and these numbers are specified by the

w:spacingtag. Vertical spacing is specified byw:afterandw:beforetags. Note that line spacing is specified byw:line, but this is not the size of the line as one may expect. To get the size of the line, take the current font height, multiply byw:lineand divide by 12. - DOCX files contain no information about pagination. You won’t find the number of pages in the document unless you calculate how much space you need for each line to ascertain the number of pages. If you need to find exact coordinates of each character on the page, be sure to take into account all spacings, indentations and sizes.

- If you implement a full-featured DOCX layouter that handles tables, note the special cases when tables span multiple pages. A cell which causes a page overflow also affects other cells.

- Creating an optimal algorithm for calculating a table columns’ width is a challenging math problem and word processors and layouters usually use some suboptimal implementations. I propose using the algorithm from W3C HTML table documentation as a first approximation. I haven’t found a description of the algorithm used by MS Word, and Microsoft has fine-tuned the algorithm over time so different versions of Word may lay out tables slightly differently.

If something is unclear: reverse-engineer the XML!

When it’s not obvious how this or that XML tag works inside MS Word, there are two main approaches to figuring it out:

-

Create the desired content step-by-step. Start with a simple docx file. Save each step to its own file, as in

1.docx,2.docx, for example. Unzip each of them and use a visual diff tool for folder comparison to see which tags appear after your changes. (For a commercial option, try Araxis Merge, or for a free option, WinMerge.) -

If you generate a DOCX file that MS Word doesn’t like, work backwards. Simplify your XML step by step. At some point you will learn which change MS Word found incorrect.

DOCX is quite complex, isn’t it?

It is complex, and Microsoft’s license forbids using MS Word on the server side for processing DOCX– this is pretty standard for commercial products. Microsoft has, however, provided the XSLT file to handle most DOCX tags, but it won’t give you 100 percent or even 99 percent fidelity. Processes such as text wrapping over images are not supported, but you will be able to support the majority of documents. (If you don’t need complexity, consider using Markdown as an alternative.)

If you have a sufficient budget (there is no free DOCX rendering engine), you may want to use commercial products such as Aspose or docx4j. The most popular free solution is LibreOffice for converting between DOCX and other formats, including PDF. Unfortunately, LibreOffice contains many small bugs during conversion, and since it’s a sophisticated, open-source C++ product, it’s slow and difficult to fix fidelity issues.

Alternatively, if you find DOCX layouting too complicated to implement yourself, you can also convert it to HTML and use a browser to render it. You can also consider one of Toptal’s freelance XML developers.

DOCX Resources for further reading

- ECMA DOCX specification

- OpenXML library for DOCX manipulation from C#. It doesn’t contain information on layouting or rendering code, but offers a class hierarchy matching each possible XML node in DOCX.

- You can always search or ask on stackoverflow with keywords like docx4j, OpenXML and docx; there are people in the community who are knowledgeable.