WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27737

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Most

of the English lexicon is constituted by word which have several

morphemes. (75 % engl. Words – polymorphemic words).

In

ME most English vocabulary arises grows by making new lexemes out of

old one, by adding an affixation to previously existing forms

altering their words class and meaning by combining the existing

words (basis) to produce compounds: derivatives, derived words

(friendly

– unfriendly, teapot, bag bone).

The

contribution of word formation to the grows and development of

English lexicons is second to none, although a great deal belong to

borrowing and semantic derivation.

-

A

complex word structure – the result of different word-formation

process (illegal, discouraging, uninteresting) -

A

complex word structure may be connected with borrowing and further

identification of certain morpheme in the system of language

recipient.

Moreover

similar international structure may be the result of different word

formation process. E.g. discouraging

– discourage + ing; uninteresting – un + interesting

– morphologically(structurally) they are the same.

The

morphemic analyses and derived analyses they are differ in the aims

and basic elements.

To

eye – monomorphic (root word) It’s a derived word.A

morpheme

– the smallest meaningful language unit. Morphemes

may be classified:

-

from

the semantic point of view.

Semantically morphemes fall into two classes:-

root-morphemes

— is the lexical nucleus of a wщrd, it has an individual lexical

meaning shared by no other morpheme of the language. The

root-morpheme is isolated as the morpheme common to a set of words

making up a word-cluster, for example the morpheme teach-in

to teach,

teacher, teaching, theor- in

theory,

theorist, theoretical, etc.

-

non-root

or affixational

morphemes

include inflectional morphemes or inflections and affixational

morphemes or affixes. Roots and affixes make two distinct classes of

morphemes due to the different roles they play in word-structure.

Roots

and affixational morphemes are generally easily distinguished and the

difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words

helpless,

handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.:

the root-morphemes help-,

hand-, black-, London-, -fill are

understood as the lexical centres of the words, as the basic

constituent part of a word without which the word is inconceivable.

Affixes

are classified into prefixes

and suffixes:

a prefix precedes the root-morpheme, a suffix follows it.

Affixes besides the meaning proper to root-morphemes possess the

part-of-speech meaning and a generalised lexical meaning.

-

Structurally morphemes fall into three types:

-

A

free

morpheme

is defined as one that coincides with the stem or a word-form. A

great many root-morphemes are free morphemes, for example, the

root-morpheme friend

—

of the noun friendship

is

naturally qualified as a free morpheme because it coincides with

one of the forms of the noun friend. -

A

bound

morpheme

occurs only as a constituent part of a word. Affixes are,

naturally, bound morphemes, for they always make part of a word,

e.g. the suffixes -ness,

-ship, -ise (-ize), etc.,

the prefixes un-,dis-,

de-, etc.

(e.g. readiness, comradeship, to activise; unnatural, to displease,

to decipher).

-

Many

root-morphemes also belong to the class of bound morphemes which

always occur in morphemic sequences, i.e. in combinations with ‘

roots or affixes. All unique roots and pseudo-roots are-bound

morphemes. Such are the root-morphemes theor-

in

theory,

theoretical, etc.,

barbar-in

barbarism,

barbarian, etc.,

-ceive

in

conceive, perceive,

etc.

-

Semi-bound

(semi-free)

morpheme

are morphemes that can function in a morphemic sequence both as an

affix and as a free morpheme. For example, the morpheme well

and

half

on

the one hand occur as free morphemes that coincide with the stem and

the word-form in utterances like sleep

well, half an hour,” on

the other hand they occur as bound morphemes in words like

well-known,

half-eaten, half-done.Speaking

of word-structure on the morphemic level two groups of morphemes

should be specially mentioned.

To

the

first

group

belong morphemes of Greek and Latin origin often called combining

forms,

e.g. telephone,

telegraph, phonoscope, microscope, etc.

The morphemes tele-,

graph-, scope-, micro-, phone- are

characterised by a definite lexical meaning and peculiar stylistic

reference: tele-

means

‘far’, graph-

means

‘writing’, scope

— ’seeing’, micro-

implies

smallness, phone-

means

’sound.’ Comparing words with tele-

as

their first constituent, such as telegraph,

telephone, telegram one

may conclude that tele-

is

a prefix and graph-,

phone-, gram-are

root-morphemes. On the other hand, words like phonograph,

seismograph, autograph may

create the impression that the second morpheme graph

is

a suffix and the first — a root-morpheme. These morphemes are all

bound root-morphemes of a special kind and such words belong to words

made up of bound roots. The fact that these morphemes do not possess

the part-of-speech meaning typical of affixational morphemes

evidences their status as roots.

The

second

group

embraces

morphemes occupying a kind of intermediate

position, morphemes that are changing their class membership.

According

to the number of morphemes words are classified into monomorphic

and

polymorphic.

Monomorphiс

or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small,

dog, make, give, etc.

Pоlуmоrphiс

words according to the number of root-morphemes are classified into

two subgroups:

-

polyradical

words, i.e. words which consist of two or more roots. Polyradical

words fall into two types:

1)

polyradical

words

which consist of two or more roots with no affixational morphemes,

e.g. book-stand,

eye-ball, lamp-shade, etc.

and

2)

words which contain

at least two

roots

and one

or more

affixational

morphemes,

e.g. safety-pin,

wedding-pie, class-consciousness, light-mindedness, pen-holder, etc.

-

Monoradical

words fall into two subtypes:

radical-suffixal

words, i.e. words that consist of one root-morpheme and one or more

suffixal morphemes, e.g. acceptable,

acceptability, blackish, etc.;

2)radical-prefixal

words, i.e. words that consist of one root-morpheme and a prefixal

morpheme, e.g. outdo,

rearrange, unbutton, etc.

and 3) prefixo-radical-suffixal,

i.e. words which consist of one root, a prefixal and suffixal

morphemes, e.g. disagreeable,

misinterpretation, etc.

Three

types of morphemic segmentability of words are distinguished:

complete,

conditional

and

defective.

Complete

segmentability is characteristic of a great many words the morphemic

structure of which is transparent enough, as their individual

morphemes clearly stand out within the word lending themselves easily

to isolation.

Conditional

morphemic segmentability characterises words whose segmentation into

the constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons. The

morphemes making up words of conditional segmentability thus differ

from morphemes making up words of complete segmentability in that the

former do not rise to the full status of morphemes for semantic

reasons and that is why a special term is applied to them in

linguistic literature: such morphemes are called pseudo-morphemes

or quasi-morphemes.

Defective

morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose component

morphemes seldom or never recur in other words. One

of

the component morphemes is a unique morpheme in the sense that it

does not, as a rule, recur in a different linguistic environment. A

unique morpheme is isolated and understood as meaningful because the

constituent morphemes display a more or less clear denotational

meaning. The morphemic analysis of words like cranberry,

gooseberry, strawberry shows

that they also possess defective morphemic segmentability: the

morphemes cran-,

goose-, straw- are

unique morphemes.

Morphemic

analyses – the

aim is to state the number and type of morphemes the word possess.

The

procedure generally employed for the purposes of segmenting words

into the constituent morphemes is the method of Immediate

and Ultimate

Constituents.

This method is based on a binary principle, i.e. each stage of the

procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into.

At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate

Constituents (ICs). Each IC at the next stage of analysis is in turn

broken into two smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is

completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further

division, i.e. morphemes. In terms of the method employed these are

referred to as the Ultimate Constituents (UCs). For example the noun

friendliness

is

first segmented into the IC friendly

recurring

in the adjectives friendly-looking

and

friendly

and

the -ness

found

in a countless number of nouns, such as happiness,

darkness, unselfishness, etc.

The IC -ness

is

at the same time a UC of the noun, as it cannot be broken into any

smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. The IC

friendly

is

next broken into the ICs friend-and

-ly

recurring

in friendship,

unfriendly, etc.

on the one hand, and wifely,

brotherly, etc.,

on the other. Needless to say that the ICs friend-and

-ly

are

both UCs of the word under analysis.

The

morphemic analysis according to the IC and UC may be carried out on

the basis of two principles: the so-called root

principle

and

the

affix principle.

According to the affix

principle

the segmentation of the word into its constituent morphemes is based

on the identification of an affixational morpheme within a set of

words; for example, the identification of the suffixational morpheme

-less

leads

to the segmentation of words like useless,

hopeless, merciless, etc.,

into the suffixational morpheme -less and the root-morphemes within a

word-cluster; the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the

words agreeable,

agreement, disagree makes

it possible to split these words into the root -agree-

and

the affixational morphemes -able,

-ment, dis-. As

a rule, the application of one of these

11.

Derivational analyses.

The

nature, type and arrangement of the ICs of the word is known as its

derivative

structure.

According to the derivative structure all words fall into two big

classes: simple,

non-derived words and complexes

or derivatives.

Simplexes

are words which derivationally cannot’ be segmented into ICs.

Derivatives

are words which depend on some other simpler lexical items that

motivate them structurally and semantically, i.e. the meaning and the

structure of the derivative is understood through the comparison with

the meaning and the structure of the source word.

The

basic elementary units of the derivative structure of words are:

derivational

bases,

derivational

affixes

and

derivational

patterns.

The relations between words with a common root but of different

derivative structure are known as derivative

relations.

The derivative and derivative relations make the subject of study at

the

derivational

level

of analysis;

it aims at establishing correlations between different types of

words, the structural and semantic patterns words are built on, the

study also enables one to understand how new words appear in the

language.

Derivational

base: is

defined as the constituent to which a rule of word-formation is

applied. Structurally derivational bases fall into three classes: 1)

bases

that coincide

with

morphological

stems

of different degrees of complexity, e.g. dutiful,

dutifully;

day-dream,

to day-dream, daydreamer.

Derivationally

the stems may be:

-

simple,

which consist of only one, semantically non motivated constituent

(pocket,

motion, retain, horrible).

b) derived

stems are semantically and structurally motivated, and are the

results of the application of word-formation rules (girl

– girlish, to weekend, to daydream)

c) compound

stems are always binary and semantically motivated (match-box,

letter-writer)

2)

bases

that coincide with

word-forms;

e.g. paper-bound,

unsmiling,

unknown.

This class of bases is confined to verbal word-forms

— the

present and the past participles.

3)

bases

that coincide with

word-grоups

of different degrees of stability, e ,g. second-rateness,

flat-waisted,

etc. This class is made of word-groups. Bases of this kind are most

active with derivational affixes in the class of adjectives and

nouns, e.g. blue-eyed,

long-fingered, old-fashioned, do-gooder, etc.

Derivational

affixes: Derivational

affixes are ICs of numerous derivatives in all parts of speech.

Derivational affixes possess two basic functions: 1)

that

of stem-building

and 2)

that

of word-building.

In most cases derivational affixes perform both

functions

simultaneously. It is true that the part-of-speech meaning is proper

in different degrees to the derivational suffixes and prefixes. It

stands out clearly in derivational suffixes but it is less evident in

prefixes; some prefixes lack it altogether. Prefixes like en-,

un-, de-,

out-,

be-,

unmistakably possess the part-of-speech meaning and function as verb

classifiers. The prefix over-evidently

lacks the part-of-speech meaning and is freely used both for verbs

and adjectives, the same may be said about non-,

pre-, post-.

Derivational

patterns: A

derivational

pattern

is a regular

meaningful arrangement, a structure that imposes rigid rules on the

order and the nature of the derivational bases and affixes that may

be brought together.

There

are two types of DPs — structural that specify base classes and

individual affixes, and structural-semantic that specify semantic

peculiarities of bases and the individual meaning of the affix. DPs

of different levels of generalisation signal: 1)

the

class of source unit that motivates the derivative and the direction

of motivation between different classes of words; 2)

the

part of speech of the derivative; 3)

the

lexical sets and semantic features of derivatives.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The study of word structure is called morphology. Understanding word structure helps us:

- improve spelling

- expand vocabulary

In studying word structure, we start by looking at a few key concepts first:

- root words

- prefixes

- suffixes

Root words are words, or parts of words, that can usually stand alone. The following are all root words:

- elbow

- fast

- nudge

Most root words can be changed in various ways by adding additional elements to them:

- elbows

- faster

- nudged

Each of the examples above has been altered by adding an element at the end. The elements at the end, namely -s, -er, and -ed, cannot stand alone. These elements are called suffixes.

Sometimes, elements are added to the beginning of a word:

- expose → underexpose

- appear → disappear

- take → overtake

- event → non-event

The elements added to the beginnings of the words above cannot stand alone, and are called prefixes.

Sometimes, when we add a prefix or suffix to a word, we create a new word. This process is called derivation.

- appear → appearance

The two words above are definitely two different words — the first is a verb, the second a noun. Their meanings and uses in sentences are different. In a dictionary, we would have to look them up separately, even though they have a common root word.

Sometimes, when we add a suffix, we don’t create a new word at all. This process is called inflection.

- cat → cats

In the above example, we really have just one word — the first is singular, the second plural. In a dictionary, we might look for cat, but we wouldn’t look for a separate entry for cats.

When words are built from a common root word, or a common ancestor in history (often a Latin word), we call the group of words a word family.

- grammar, grammatical, grammatically, ungrammatical, ungrammatically

The terms above are all built from a common root word, grammar. This word family includes a noun, adjectives, and adverbs.

The terms below are built from a common ancestor, the Latin word spectare, meaning ‘to look’:

- inspect, spectacle, spectacular, inspection

This word family includes verbs, nouns, and adjectives.

Full Preview

This is a full preview of this page. You can view a page a day like this without registering.

But if you wish to use it in your classroom, please register your details on Englicious (for free) and then log in!

SKIP

WORD-STRUCTURE AND WORD-FORMATION IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

How do we guess the meanings of the words we have never encountered before? Attachment: attach (root morpheme) + -ment (suffix) attachment – smth. you add to a document ? Attachmeant ? to mean – meant // -ment N-forming suffix v the file you meant to attach to your email but did not

This is one of the central questions of lexicology: the structure of words and the ways of building new words Lexicology studies the internal structure of words and the rules of word-formation, the formation of new words from the resources of this particular language. Together with the borrowing, wordforming provides for enlarging and enriching the vocabulary of the language.

Morphemes What is the smallest meaningful unit of the language? Sound / phoneme? ? ? Word? ? ? ring > ringlet MORPHEME! Morpheme is the minimum meaningful language unit. Morphemes are not independent, they occur only as parts of words, although a word may consist of a single morpheme (love, house, red, cry).

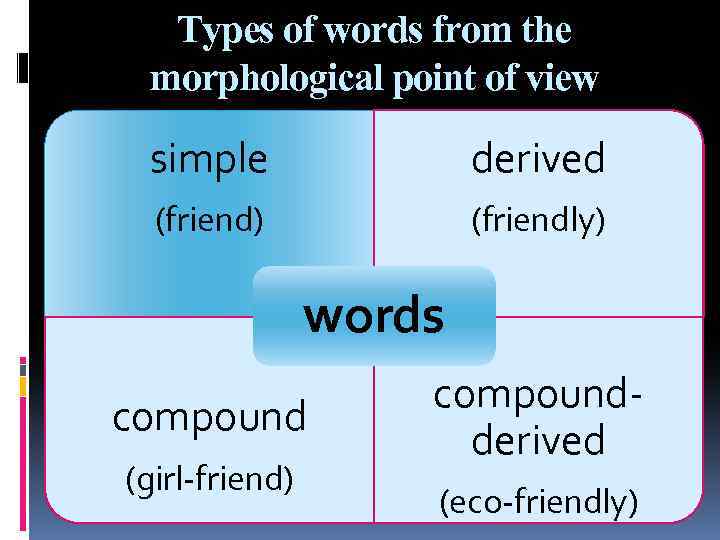

Types of words from the morphological point of view simple derived (friend) (friendly) words compound (girl-friend) compoundderived (eco-friendly)

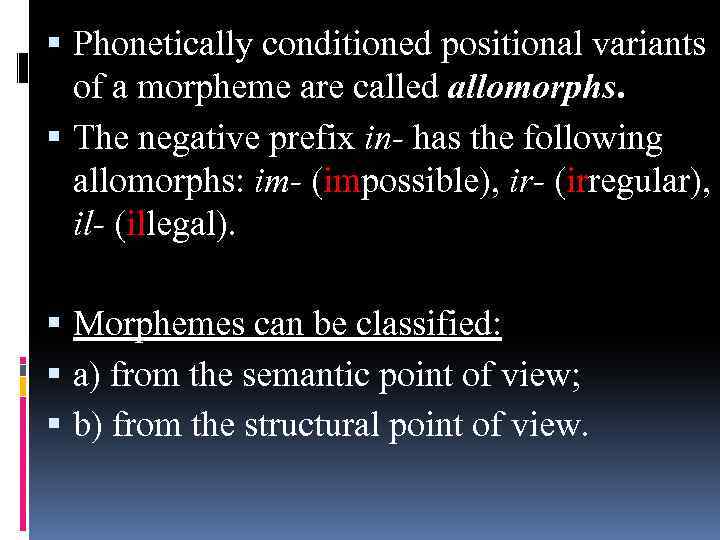

Phonetically conditioned positional variants of a morpheme are called allomorphs. The negative prefix in- has the following allomorphs: im- (impossible), ir- (irregular), il- (illegal). Morphemes can be classified: a) from the semantic point of view; b) from the structural point of view.

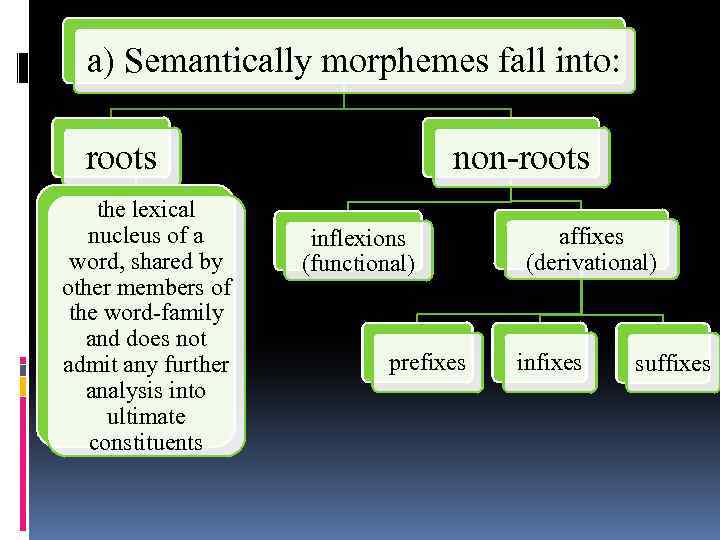

a) Semantically morphemes fall into: roots the lexical nucleus of a word, shared by other members of the word-family and does not admit any further analysis into ultimate constituents non-roots inflexions (functional) prefixes affixes (derivational) infixes suffixes

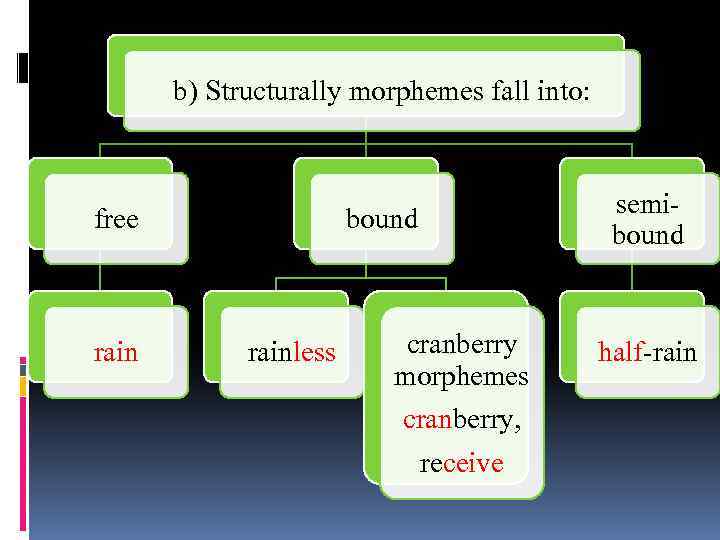

b) Structurally morphemes fall into: free rain bound rainless cranberry morphemes cranberry, receive semibound half-rain

Morphemic and word-formation analysis The procedure employed for segmenting words is morphemic analysis based on the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on a binary principle. At each stage two components are singled out (referred to as the Immediate Constituents (ICs)). Each IC at the next stage of the analysis is broken into two smaller meaningful units. The analysis is complete when we arrive at further unsegmentable units, i. e. morphemes. They are called Ultimate Constituents (UCs).

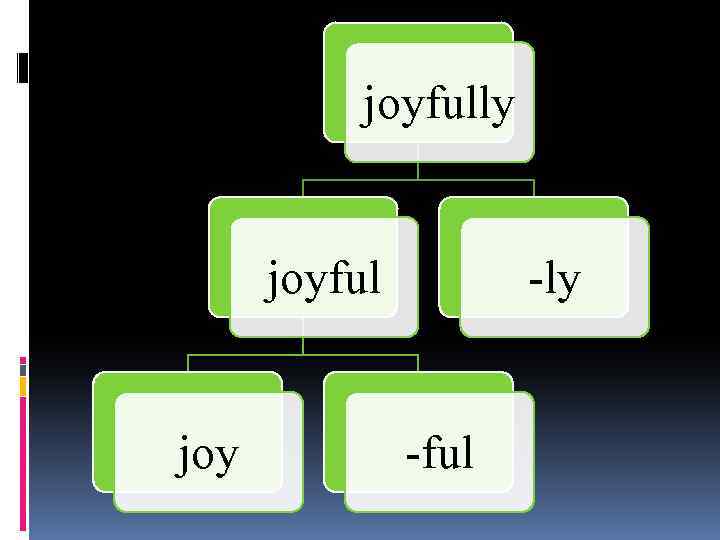

joyfully joyful joy -ly -ful

Structural word-formation analysis proceeds further, studying the structural correlation with other words. It is done with the help of the principle of oppositions, i. e. by studying the partly similar elements, the difference between which is functionally relevant. In our case joyfully and joyful are members of a morphemic opposition. Their distinctive feature is the suffix -ly, like in other oppositions of the same kind: joyful dreadful beautiful joyfully dreadfully beautifully Observing this proportional opposition we may conclude that there is a type of derived adverbs consisting of an adjective stem and the suffix -ly.

Structural morphemic analysis is helpful in distinguishing compound words formed by composition from the ones formed by other wordformation processes. to daydream to whitewash composition or composition + conversion? day (N) + dream (N) = daydream (N) composition daydream (N) > to daydream (V) conversion white (ADJ) + to wash (V) = to whitewash (V) composition

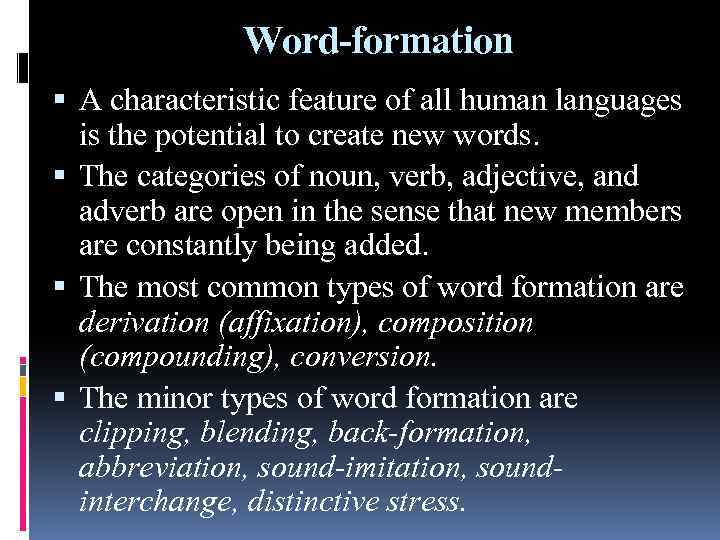

Word-formation A characteristic feature of all human languages is the potential to create new words. The categories of noun, verb, adjective, and adverb are open in the sense that new members are constantly being added. The most common types of word formation are derivation (affixation), composition (compounding), conversion. The minor types of word formation are clipping, blending, back-formation, abbreviation, sound-imitation, soundinterchange, distinctive stress.

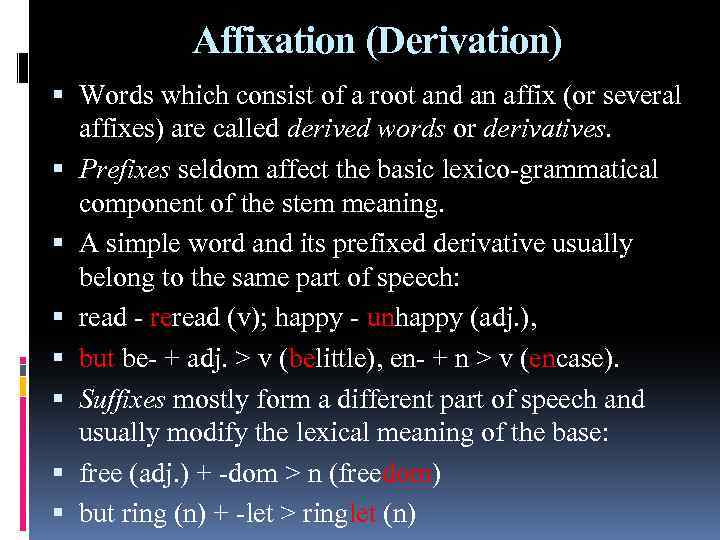

Affixation (Derivation) Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives. Prefixes seldom affect the basic lexico-grammatical component of the stem meaning. A simple word and its prefixed derivative usually belong to the same part of speech: read — reread (v); happy — unhappy (adj. ), but be- + adj. > v (belittle), en- + n > v (encase). Suffixes mostly form a different part of speech and usually modify the lexical meaning of the base: free (adj. ) + -dom > n (freedom) but ring (n) + -let > ringlet (n)

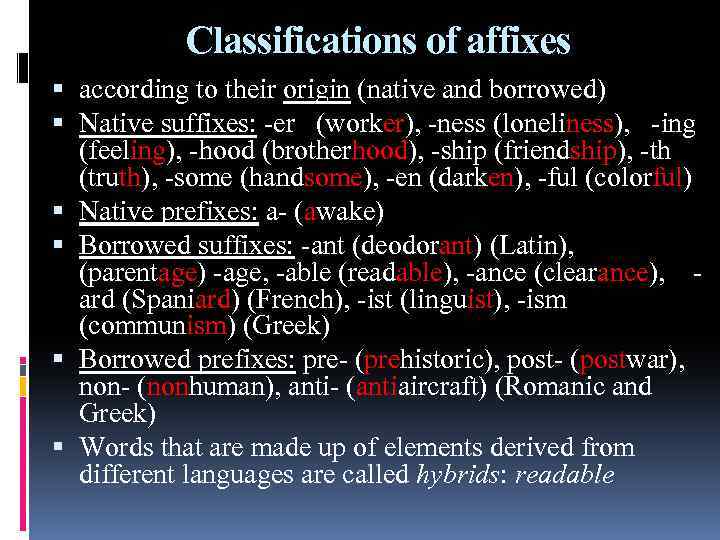

Classifications of affixes according to their origin (native and borrowed) Native suffixes: -er (worker), -ness (loneliness), -ing (feeling), -hood (brotherhood), -ship (friendship), -th (truth), -some (handsome), -en (darken), -ful (colorful) Native prefixes: a- (awake) Borrowed suffixes: -ant (deodorant) (Latin), (parentage) -age, -able (readable), -ance (clearance), ard (Spaniard) (French), -ist (linguist), -ism (communism) (Greek) Borrowed prefixes: pre- (prehistoric), post- (postwar), non- (nonhuman), anti- (antiaircraft) (Romanic and Greek) Words that are made up of elements derived from different languages are called hybrids: readable

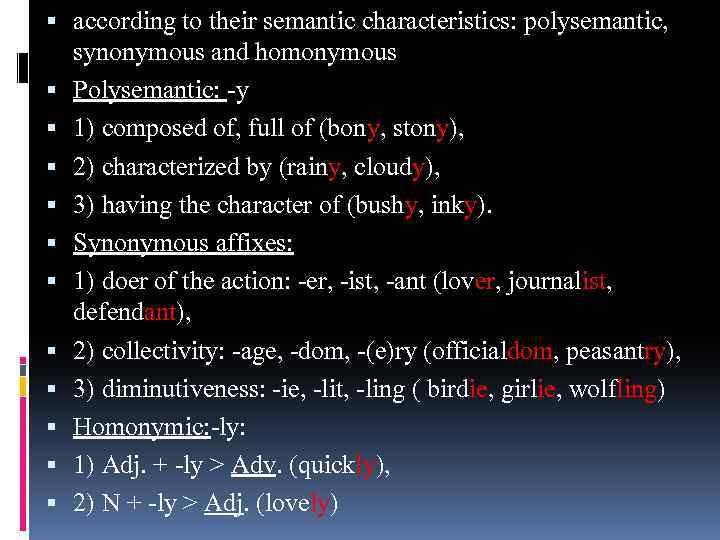

according to their semantic characteristics: polysemantic, synonymous and homonymous Polysemantic: -у 1) composed of, full of (bony, stony), 2) characterized by (rainy, cloudy), 3) having the character of (bushy, inky). Synonymous affixes: 1) doer of the action: -er, -ist, -ant (lover, journalist, defendant), 2) collectivity: -age, -dom, -(e)ry (officialdom, peasantry), 3) diminutiveness: -ie, -lit, -ling ( birdie, girlie, wolfling) Homonymic: -ly: 1) Adj. + -ly > Adv. (quickly), 2) N + -ly > Adj. (lovely)

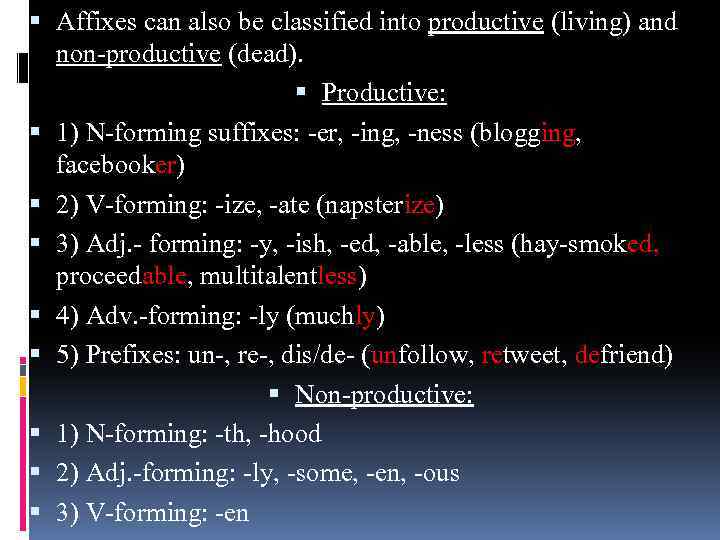

Affixes can also be classified into productive (living) and non-productive (dead). Productive: 1) N-forming suffixes: -er, -ing, -ness (blogging, facebooker) 2) V-forming: -ize, -ate (napsterize) 3) Adj. — forming: -y, -ish, -ed, -able, -less (hay-smoked, proceedable, multitalentless) 4) Adv. -forming: -ly (muchly) 5) Prefixes: un-, re-, dis/de- (unfollow, retweet, defriend) Non-productive: 1) N-forming: -th, -hood 2) Adj. -forming: -ly, -some, -en, -ous 3) V-forming: -en

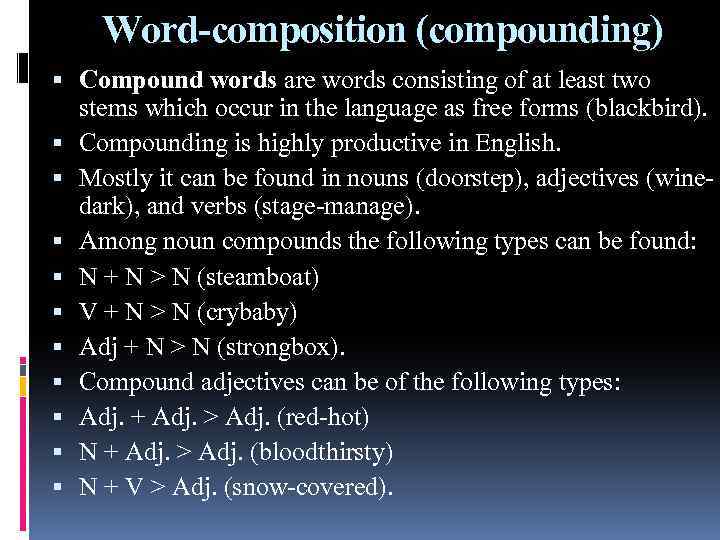

Word-composition (compounding) Compound words are words consisting of at least two stems which occur in the language as free forms (blackbird). Compounding is highly productive in English. Mostly it can be found in nouns (doorstep), adjectives (winedark), and verbs (stage-manage). Among noun compounds the following types can be found: N + N > N (steamboat) V + N > N (crybaby) Adj + N > N (strongbox). Compound adjectives can be of the following types: Adj. + Adj. > Adj. (red-hot) N + Adj. > Adj. (bloodthirsty) N + V > Adj. (snow-covered).

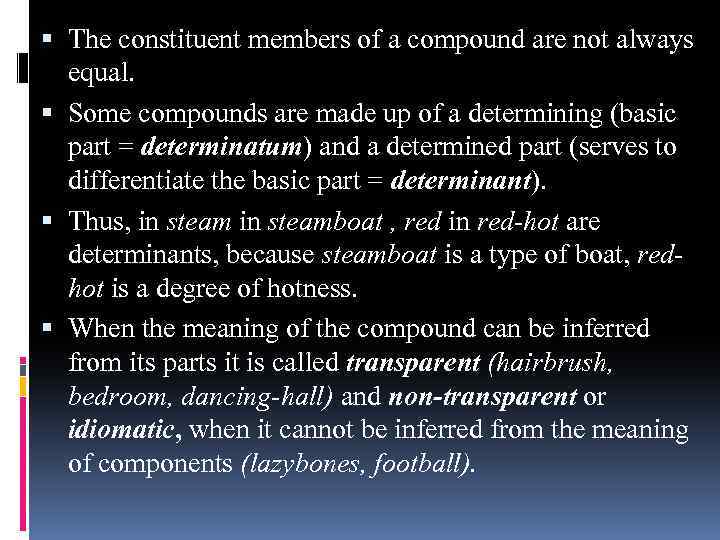

The constituent members of a compound are not always equal. Some compounds are made up of a determining (basic part = determinatum) and a determined part (serves to differentiate the basic part = determinant). Thus, in steamboat , red in red-hot are determinants, because steamboat is a type of boat, redhot is a degree of hotness. When the meaning of the compound can be inferred from its parts it is called transparent (hairbrush, bedroom, dancing-hall) and non-transparent or idiomatic, when it cannot be inferred from the meaning of components (lazybones, football).

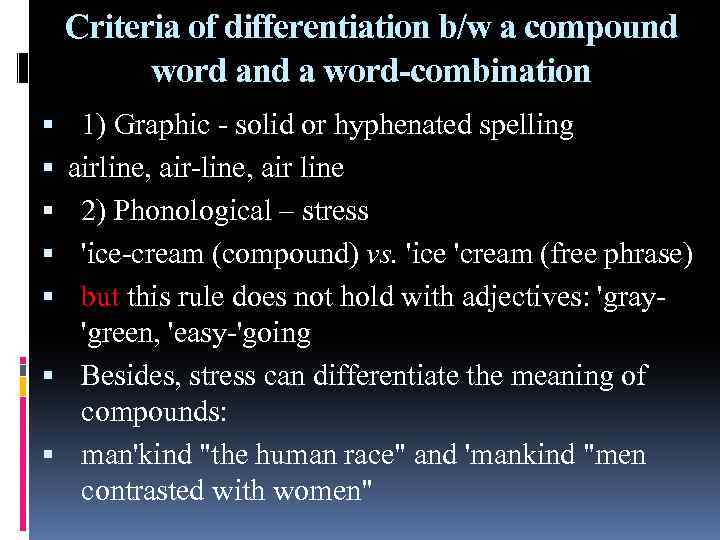

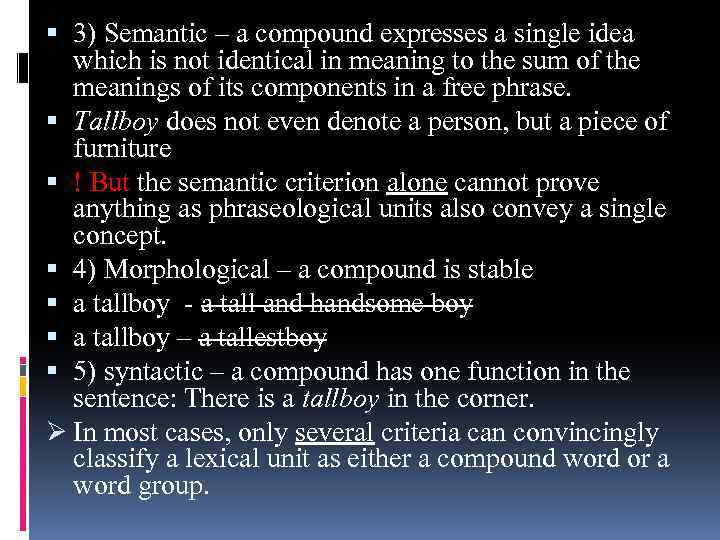

Criteria of differentiation b/w a compound word and a word-combination 1) Graphic — solid or hyphenated spelling airline, air-line, air line 2) Phonological – stress ‘ice-cream (compound) vs. ‘ice ‘cream (free phrase) but this rule does not hold with adjectives: ‘gray’green, ‘easy-‘going Besides, stress can differentiate the meaning of compounds: man’kind «the human race» and ‘mankind «men contrasted with women»

3) Semantic – a compound expresses a single idea which is not identical in meaning to the sum of the meanings of its components in a free phrase. Tallboy does not even denote a person, but a piece of furniture ! But the semantic criterion alone cannot prove anything as phraseological units also convey a single concept. 4) Morphological – a compound is stable a tallboy — a tall and handsome boy a tallboy – a tallestboy 5) syntactic – a compound has one function in the sentence: There is a tallboy in the corner. Ø In most cases, only several criteria can convincingly classify a lexical unit as either a compound word or a word group.

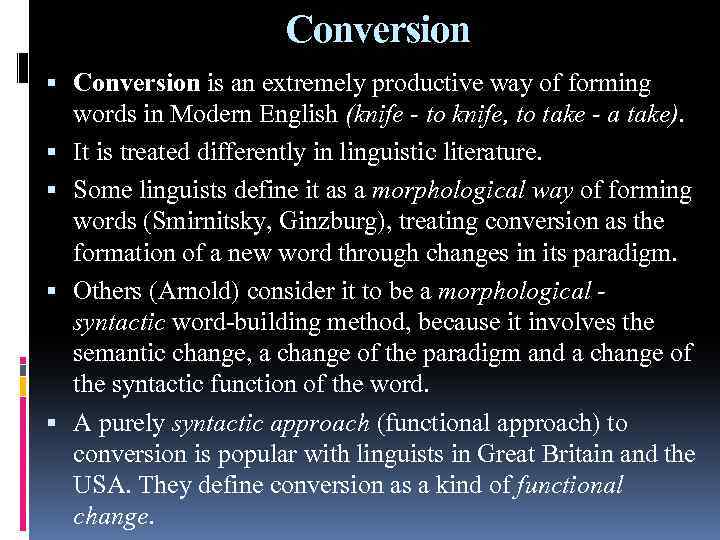

Conversion is an extremely productive way of forming words in Modern English (knife — to knife, to take — a take). It is treated differently in linguistic literature. Some linguists define it as a morphological way of forming words (Smirnitsky, Ginzburg), treating conversion as the formation of a new word through changes in its paradigm. Others (Arnold) consider it to be a morphological syntactic word-building method, because it involves the semantic change, a change of the paradigm and a change of the syntactic function of the word. A purely syntactic approach (functional approach) to conversion is popular with linguists in Great Britain and the USA. They define conversion as a kind of functional change.

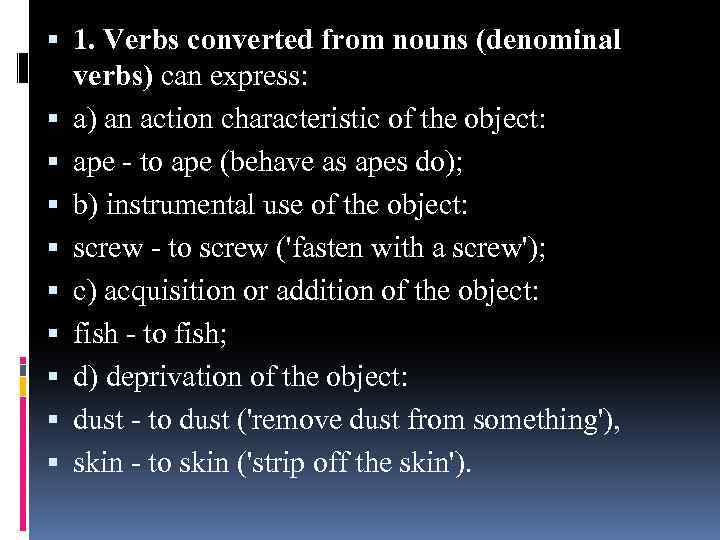

1. Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs) can express: a) an action characteristic of the object: ape — to ape (behave as apes do); b) instrumental use of the object: screw — to screw (‘fasten with a screw’); c) acquisition or addition of the object: fish — to fish; d) deprivation of the object: dust — to dust (‘remove dust from something’), skin — to skin (‘strip off the skin’).

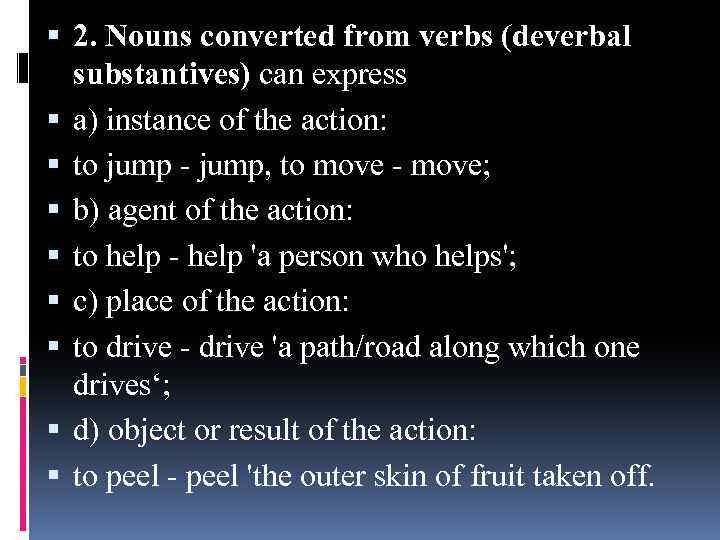

2. Nouns converted from verbs (deverbal substantives) can express a) instance of the action: to jump — jump, to move — move; b) agent of the action: to help — help ‘a person who helps’; c) place of the action: to drive — drive ‘a path/road along which one drives‘; d) object or result of the action: to peel — peel ‘the outer skin of fruit taken off.

Some other patterns of conversion can be mentioned. 3. Adjectives > Nouns: supernatural, impossible, inevitable; 4. Participle > Adjectives: a standing man / rule, running water. But not all the pairs of such words can be formed by conversion. Some of them arose: (1) as a result of the loss of endings in the course of the historical developments of the English language: love, hate, rest, smell, work, end, answer, care, drink, (2) assimilation of borrowings: check, cry, doubt, change. Some linguists (Smirnitsky, Arbekova) call them patterned homonymy.

Minor types of word formation. Shortening While derivation and compounding represent addition, shortening, on the other hand, may be represented as subtraction, in which part of word or word group is taken away. Shortening can be called a process of wordcoining.

Clipping is a process of creating of a new word by shortening of the original polysyllabic word (prototype). According to what part is cut off we distinguish: final – doc (doctor), initial – net (Internet) medial clipping – poli-sci (political science).

Blending is combining parts of two words to form one. motel = motor + hotel brunch = breakfast + lunch, selectric = select + electric dancercise = dance + exercise. Sometimes only the first word is clipped, as in perma-press for ‘permanent-press’.

Back-Formation Back-formation is a process whereby a word whose form is similar to that of a derived form undergoes a process of deaffixation (the singling-out of a stem from a word which is wrongly regarded as a derivative). resurrect < resurrection enthuse < enthusiasm donate < donation orient < orientation A major source of back-formation in English is represented by the words that end with -er or -or and have meanings involving the notion of an agent, such as editor, peddler, swindler, and stroker. Because hundreds of words ending in these affixes are the result of affixation, it was assumed that these words too had been formed by adding -er or -or to a verb. So, edit, peddle, swindle, and stroke exist as simple verbs.

Abbreviation is the process and the result of forming a word out of the initial elements (letters, morphemes) of a word combination. (a) If the abbreviated written form is read like a word it is called an acronym — AIDS, NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization), radar (radio detecting and ranging), (b) The other subgroup of abbreviations is pronounces like a series of letters (initialisms) — S. O. S. , NFL (National Football League), B. B. C. (the British Broadcasting Corporation), (c) The term abbreviation may be used for a shortened form of a written word or phrase used in a text for economy of space and effort (graphic abbreviation) — L. A. , N. Y. , B. A. for Bachelor of Arts, ltd for limited, Xmas for Christmas.

Sound interchange may be defined as an opposition in which words or word forms are differentiated due to an alternation in phonemic composition of the root. The change may affect the root vowel: food N — feed V, root consonant: speak V — speech N, or both: life N — live V. It also may be combined with affixation: strong Adj. strength N, or with affixation and shift of stress: ‘democrat — de’mocracy. Distinctive stress: ‘conduct N — con’duct V, object, etc. Sound imitation is the formation of new words from sounds that resemble those associated with the object or action to be named, or that seem suggestive of its qualities: buzz, hiss, sizzle, cuckoo.

Thanks for attention!

This is my paper summary of English Morphology Class

2.1 WHAT IS A WORD?

The assumption that languanges contain word is taken for granted by most people. Even illiterate speakers know that therer are words in their language. True, sometimes there are differences of opinion as to what units are to be treater as word.

2.1.1 The Lexeme

However, closer examination of the nature of the ‘word’ reveals a somewhat more complex picture than i have painted above. What we mean by ‘word’ is not clear. As we shall see in the next few paragraphs, diffuculties in clarifying the nature of the word are largely due to the fact the term ‘word’ ised in a variety of senses which usually are not clearly distinguished.

What would you do if you were reading a book and you encountered the ‘word’ pockled for the first time in this context?

[2.1] He went to the pub for a pint and then pockled off.

We shall refer to the ‘word’ in this sense of abstact of vocabulary item using the term lexeme.

Which one of the word in [2.2] below belong to the same lexeme?

[2.2] see catches taller boy catching sees

sleeps women catch saw tallest sleeping

boys sleep seen tall slept caught

seeing jump women slept jumps jumping

we shoul all agree that :

The physical word form are realisation of the lexeme

See,sees,sleeing,saw,seen SEE

Sleeps, sleeping,slept SLEEP

Catch, catches, catching, caught CATCH

2.1.2 Word form

As we have just seen above,sometimes, when we use the term ‘word’, it is not the abstract vocabulary item with a common core of meaning,the lexeme, that we want to refer to. Thus we can refer to see, sees, seeing, saw and seen as five different word we counting the number of word.

2.1.3 The Gramatical Word

The ‘word’ can also be seen as a representation of a lexeme that is associated with certain morpho-syntactic properties such as noun, adjective,verb, tense, gender, number, etc.

Should why cut should be regarded as representing two distinct grammatical word in the following :

[2.3] a. Usually i cut the bread on the table

b. Yesterday i cut the bread in the sink

The same word-form cut, belonging to the verbal lexeme CUT, can represent two different grammatical words. In [2.3] cut represents the grammatical word cut [verb,present,noun 3rd person]. But in [2.3b] it represents the grammatical word cut [verb, past] which realises the past tense of CUT.

2.2 MORPHEMES : THE SMALLEST UNITS OF MEANING

Morphology is the study of word structure. The claim that words have structure might come as a suprise becayse normally speakers think of word as indivisble units of meaning. This is probably due to the fact that many word are morphologically simple. For example the,fierce, desk, eat, boot, at, fee, mosquito,etc.

The term morpheme is used to refer to the smallest, indivisible unit of semantic content or grammatical function which word are made up of. By definition, a morpheme cannot be decomposed into smaller units which are cither meaningful by themselves or mark a grammatical function like singular or plural number in the noun.

List two other word which contain cach morpheme represented below :

[2.4]. a. –er as in (play-er, call-er), -ness as in (kind-ness, good-ness), -ette as in (kitchen-ette, cigar-ette)

b. ex as in (ex-wife,ex-minister), pre as in (pre-war, pre-school), mis as in (mis-kick,mis-jugde).

The form –er is attached to verbs to derive nouns with the general meaning, -ness is added to an adjective,it produces a noun meaning, -ette to a noun derrives a new noun which has the meaning, -ex and pre- derive nouns from nouns while mis- derive verbs from verbs.

2.2.1 Analysing Word

We have used the criterion of meaning to identify morphemes, where the meaning of a morpheme has been somewhat obscure, you have been encouraged to consult a good etymological dictionary.

Consider the following words : [2.5]

Helicopter pteropus diptera

Bible bibliography bibliophile

Helicopter is a kind of non-fixed flying aircraft, pteropus are tropical bats, diptera are two winged flies, the words bible,bibliography and bibliophile have to do with books. But it is unlikely that anoyone lacking a profound knowledge of English etymology is aware that word bible is not just the name of a scripture book.

2.2.2 Morphemes, Morps and Allomorph

At one time, establishing mechanical procedures for the identification of morphemes was considered a realistic goal by structural lingusts (cf.Harris, 1951). But it did not take long before most linguist realised that it was impossible to develop a set of discovery procedures that would lead aitomatically to a correct morphological analysis.

Definition : the morpheme is the smallest difference in the shape of a word that correlates with the smallest difference in word or sentence meaning or in grammatical structure. A morph is a physical form representing some morpheme in a language, it is recurrent distinctive sound (phoneme) or sequence of sounds (phonemes). Different morphs represent the same morpheme, they are grouped together and they are called allomorphs.

2.2.3 Grammatical Conditioning, Lexical Conditioning and Suppletion

Distribution of allomorphs is usually subject to phonological conditioning,sometimes phonological factors play no role in the selection of allomorphs. Instead the choice of allomorph may be grammatically conditioned, i.e. it may be dependent on the presence of a particular grammatical element.

In other cases, the choice of the allomoprh may be lexically conditioned, i.e. use of a particular allomorph may be obligatory if a certain word is present. We can see this in the realisation of plural in English. There exist a few morphemes whose allomorphs show no phonetic similarity, example by the forms good/better which both represent the lexeme GOOD despite the fact that they do not have even a single sound in common, where allomoprhs of a morpheme aer phonetically unrelated we speak of suppletion.

2.2.4 Underlying Representations

Above we have distinguished between, on the one hand, regular, rulegoverned phonological alternation, this is standard in generative phonology. Merely listing allomorphs does not allow us to distinguish between eccentric alternations like good/better and regular alternations like that shown by the negative prefix in- or by the regular plural –s plurall suffix. A rule of suppletion or lexical conditioning only applies if a form is expressly marked as being subject to it. Similarly, a grammatically conditioned rule will only be triggered if the appropriate grammatical conditioning factor is present.

To bring out the distinction between regular phonological alternation, which is phonitecally motivated and other kinds of morphological alternation that lack a phonetic basis, linguists posit a single underlying representation or base form from which the various allomorphs of a moprheme are derived by applying one or more phonoligical rules. The stages which a form goes through when it is being converted from an underlying representation to a phonetic representation sonstitute a derivation. The term morphophonemic and morphophonolgy are used to refer conditioned allomorphs of morphemes.