For other uses, see Stress.

In linguistics, and particularly phonology, stress or accent is the relative emphasis or prominence given to a certain syllable in a word or to a certain word in a phrase or sentence. That emphasis is typically caused by such properties as increased loudness and vowel length, full articulation of the vowel, and changes in tone.[1][2] The terms stress and accent are often used synonymously in that context but are sometimes distinguished. For example, when emphasis is produced through pitch alone, it is called pitch accent, and when produced through length alone, it is called quantitative accent.[3] When caused by a combination of various intensified properties, it is called stress accent or dynamic accent; English uses what is called variable stress accent.

| Primary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˈ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 501 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˈ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02C8 |

| Secondary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˌ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 502 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˌ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02CC |

Since stress can be realised through a wide range of phonetic properties, such as loudness, vowel length, and pitch (which are also used for other linguistic functions), it is difficult to define stress solely phonetically.

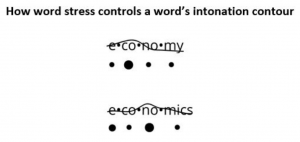

The stress placed on syllables within words is called word stress. Some languages have fixed stress, meaning that the stress on virtually any multisyllable word falls on a particular syllable, such as the penultimate (e.g. Polish) or the first (e.g. Finnish). Other languages, like English and Russian, have lexical stress, where the position of stress in a word is not predictable in that way but lexically encoded. Sometimes more than one level of stress, such as primary stress and secondary stress, may be identified.

Stress is not necessarily a feature of all languages: some, such as French and Mandarin, are sometimes analyzed as lacking lexical stress entirely.

The stress placed on words within sentences is called sentence stress or prosodic stress. That is one of the three components of prosody, along with rhythm and intonation. It includes phrasal stress (the default emphasis of certain words within phrases or clauses), and contrastive stress (used to highlight an item, a word or part of a word, that is given particular focus).

Phonetic realizationEdit

There are various ways in which stress manifests itself in the speech stream, and they depend to some extent on which language is being spoken. Stressed syllables are often louder than non-stressed syllables, and they may have a higher or lower pitch. They may also sometimes be pronounced longer. There are sometimes differences in place or manner of articulation. In particular, vowels in unstressed syllables may have a more central (or «neutral») articulation, and those in stressed syllables have a more peripheral articulation. Stress may be realized to varying degrees on different words in a sentence; sometimes, the difference is minimal between the acoustic signals of stressed and those of unstressed syllables.

Those particular distinguishing features of stress, or types of prominence in which particular features are dominant, are sometimes referred to as particular types of accent: dynamic accent in the case of loudness, pitch accent in the case of pitch (although that term usually has more specialized meanings), quantitative accent in the case of length,[3] and qualitative accent in the case of differences in articulation. They can be compared to the various types of accent in music theory. In some contexts, the term stress or stress accent specifically means dynamic accent (or as an antonym to pitch accent in its various meanings).

A prominent syllable or word is said to be accented or tonic; the latter term does not imply that it carries phonemic tone. Other syllables or words are said to be unaccented or atonic. Syllables are frequently said to be in pretonic or post-tonic position, and certain phonological rules apply specifically to such positions. For instance, in American English, /t/ and /d/ are flapped in post-tonic position.

In Mandarin Chinese, which is a tonal language, stressed syllables have been found to have tones that are realized with a relatively large swing in fundamental frequency, and unstressed syllables typically have smaller swings.[4] (See also Stress in Standard Chinese.)

Stressed syllables are often perceived as being more forceful than non-stressed syllables.

Word stressEdit

Word stress, or sometimes lexical stress, is the stress placed on a given syllable in a word. The position of word stress in a word may depend on certain general rules applicable in the language or dialect in question, but in other languages, it must be learned for each word, as it is largely unpredictable. In some cases, classes of words in a language differ in their stress properties; for example, loanwords into a language with fixed stress may preserve stress placement from the source language, or the special pattern for Turkish placenames.

Non-phonemic stressEdit

In some languages, the placement of stress can be determined by rules. It is thus not a phonemic property of the word, because it can always be predicted by applying the rules.

Languages in which the position of the stress can usually be predicted by a simple rule are said to have fixed stress. For example, in Czech, Finnish, Icelandic, Hungarian and Latvian, the stress almost always comes on the first syllable of a word. In Armenian the stress is on the last syllable of a word.[5] In Quechua, Esperanto, and Polish, the stress is almost always on the penult (second-last syllable). In Macedonian, it is on the antepenult (third-last syllable).

Other languages have stress placed on different syllables but in a predictable way, as in Classical Arabic and Latin, where stress is conditioned by the structure of particular syllables. They are said to have a regular stress rule.

Statements about the position of stress are sometimes affected by the fact that when a word is spoken in isolation, prosodic factors (see below) come into play, which do not apply when the word is spoken normally within a sentence. French words are sometimes said to be stressed on the final syllable, but that can be attributed to the prosodic stress that is placed on the last syllable (unless it is a schwa, when stress is placed on the second-last syllable) of any string of words in that language. Thus, it is on the last syllable of a word analyzed in isolation. The situation is similar in Standard Chinese. French (some authors add Chinese[6]) can be considered to have no real lexical stress.

Phonemic stressEdit

With some exceptions above, languages such as Germanic languages, Romance languages, the East and South Slavic languages, Lithuanian, as well as others, in which the position of stress in a word is not fully predictable, are said to have phonemic stress. Stress in these languages is usually truly lexical and must be memorized as part of the pronunciation of an individual word. In some languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Lakota and, to some extent, Italian, stress is even represented in writing using diacritical marks, for example in the Spanish words célebre and celebré. Sometimes, stress is fixed for all forms of a particular word, or it can fall on different syllables in different inflections of the same word.

In such languages with phonemic stress, the position of stress can serve to distinguish otherwise identical words. For example, the English words insight () and incite () are distinguished in pronunciation only by the fact that the stress falls on the first syllable in the former and on the second syllable in the latter. Examples from other languages include German Tenor ([ˈteːnoːɐ̯] «gist of message» vs. [teˈnoːɐ̯] «tenor voice»); and Italian ancora ([ˈaŋkora] «anchor» vs. [aŋˈkoːra] «more, still, yet, again»).

In many languages with lexical stress, it is connected with alternations in vowels and/or consonants, which means that vowel quality differs by whether vowels are stressed or unstressed. There may also be limitations on certain phonemes in the language in which stress determines whether they are allowed to occur in a particular syllable or not. That is the case with most examples in English and occurs systematically in Russian, such as за́мок ([ˈzamək], «castle») vs. замо́к ([zɐˈmok], «lock»); and in Portuguese, such as the triplet sábia ([ˈsaβjɐ], «wise woman»), sabia ([sɐˈβiɐ], «knew»), sabiá ([sɐˈβja], «thrush»).

Dialects of the same language may have different stress placement. For instance, the English word laboratory is stressed on the second syllable in British English (labóratory often pronounced «labóratry», the second o being silent), but the first syllable in American English, with a secondary stress on the «tor» syllable (láboratory often pronounced «lábratory»). The Spanish word video is stressed on the first syllable in Spain (vídeo) but on the second syllable in the Americas (video). The Portuguese words for Madagascar and the continent Oceania are stressed on the third syllable in European Portuguese (Madagáscar and Oceânia), but on the fourth syllable in Brazilian Portuguese (Madagascar and Oceania).

CompoundsEdit

With very few exceptions, English compound words are stressed on their first component. Even the exceptions, such as mankínd,[7] are instead often stressed on the first component by some people or in some kinds of English.[8] The same components as those of a compound word are sometimes used in a descriptive phrase with a different meaning and with stress on both words, but that descriptive phrase is then not usually considered a compound: bláck bírd (any bird that is black) and bláckbird (a specific bird species) and páper bág (a bag made of paper) and páper bag (very rarely used for a bag for carrying newspapers but is often also used for a bag made of paper).[9]

Levels of stressEdit

Some languages are described as having both primary stress and secondary stress. A syllable with secondary stress is stressed relative to unstressed syllables but not as strongly as a syllable with primary stress : for example, saloon and cartoon both have the main stress on the last syllable, but whereas cartoon also has a secondary stress on the first syllable, saloon does not. As with primary stress, the position of secondary stress may be more or less predictable depending on language. In English, it is not fully predictable, but the different secondary stress of the words organization and accumulation (on the first and second syllable, respectively) is predictable due to the same stress of the verbs órganize and accúmulate. In some analyses, for example the one found in Chomsky and Halle’s The Sound Pattern of English, English has been described as having four levels of stress: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary, but the treatments often disagree with one another.

Peter Ladefoged and other phoneticians have noted that it is possible to describe English with only one degree of stress, as long as prosody is recognized and unstressed syllables are phonemically distinguished for vowel reduction.[10] They find that the multiple levels posited for English, whether primary–secondary or primary–secondary–tertiary, are not phonetic stress (let alone phonemic), and that the supposed secondary/tertiary stress is not characterized by the increase in respiratory activity associated with primary/secondary stress in English and other languages. (For further detail see Stress and vowel reduction in English.)

Prosodic stressEdit

| Extra stress |

|---|

| ˈˈ◌ |

Prosodic stress, or sentence stress, refers to stress patterns that apply at a higher level than the individual word – namely within a prosodic unit. It may involve a certain natural stress pattern characteristic of a given language, but may also involve the placing of emphasis on particular words because of their relative importance (contrastive stress).

An example of a natural prosodic stress pattern is that described for French above; stress is placed on the final syllable of a string of words (or if that is a schwa, the next-to-final syllable). A similar pattern is found in English (see § Levels of stress above): the traditional distinction between (lexical) primary and secondary stress is replaced partly by a prosodic rule stating that the final stressed syllable in a phrase is given additional stress. (A word spoken alone becomes such a phrase, hence such prosodic stress may appear to be lexical if the pronunciation of words is analyzed in a standalone context rather than within phrases.)

Another type of prosodic stress pattern is quantity sensitivity – in some languages additional stress tends to be placed on syllables that are longer (moraically heavy).

Prosodic stress is also often used pragmatically to emphasize (focus attention on) particular words or the ideas associated with them. Doing this can change or clarify the meaning of a sentence; for example:

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (Somebody else did.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did not take it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did something else with it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took one of several. or I didn’t take the specific test that would have been implied.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took something else.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took it some other day.)

As in the examples above, stress is normally transcribed as italics in printed text or underlining in handwriting.

In English, stress is most dramatically realized on focused or accented words. For instance, consider the dialogue

«Is it brunch tomorrow?»

«No, it’s dinner tomorrow.»

In it, the stress-related acoustic differences between the syllables of «tomorrow» would be small compared to the differences between the syllables of «dinner«, the emphasized word. In these emphasized words, stressed syllables such as «din» in «dinner» are louder and longer.[11][12][13] They may also have a different fundamental frequency, or other properties.

The main stress within a sentence, often found on the last stressed word, is called the nuclear stress.[14]

Stress and vowel reductionEdit

In many languages, such as Russian and English, vowel reduction may occur when a vowel changes from a stressed to an unstressed position. In English, unstressed vowels may reduce to schwa-like vowels, though the details vary with dialect (see stress and vowel reduction in English). The effect may be dependent on lexical stress (for example, the unstressed first syllable of the word photographer contains a schwa , whereas the stressed first syllable of photograph does not /ˈfoʊtəˌgræf -grɑːf/), or on prosodic stress (for example, the word of is pronounced with a schwa when it is unstressed within a sentence, but not when it is stressed).

Many other languages, such as Finnish and the mainstream dialects of Spanish, do not have unstressed vowel reduction; in these languages vowels in unstressed syllables have nearly the same quality as those in stressed syllables.

Stress and rhythmEdit

Some languages, such as English, are said to be stress-timed languages; that is, stressed syllables appear at a roughly constant rate and non-stressed syllables are shortened to accommodate that, which contrasts with languages that have syllable timing (e.g. Spanish) or mora timing (e.g. Japanese), whose syllables or moras are spoken at a roughly constant rate regardless of stress. For details, see isochrony.

Historical effectsEdit

It is common for stressed and unstressed syllables to behave differently as a language evolves. For example, in the Romance languages, the original Latin short vowels /e/ and /o/ have often become diphthongs when stressed. Since stress takes part in verb conjugation, that has produced verbs with vowel alternation in the Romance languages. For example, the Spanish verb volver (to return, come back) has the form volví in the past tense but vuelvo in the present tense (see Spanish irregular verbs). Italian shows the same phenomenon but with /o/ alternating with /uo/ instead. That behavior is not confined to verbs; note for example Spanish viento «wind» from Latin ventum, or Italian fuoco «fire» from Latin focum. There are also examples in French, though they are less systematic : viens from Latin venio where the first syllabe was stressed, vs venir from Latin venire where the main stress was on the penultimate syllable.

Stress «deafness»Edit

An operational definition of word stress may be provided by the stress «deafness» paradigm.[15][16] The idea is that if listeners perform poorly on reproducing the presentation order of series of stimuli that minimally differ in the position of phonetic prominence (e.g. [númi]/[numí]), the language does not have word stress. The task involves a reproduction of the order of stimuli as a sequence of key strokes, whereby key «1» is associated with one stress location (e.g. [númi]) and key «2» with the other (e.g. [numí]). A trial may be from 2 to 6 stimuli in length. Thus, the order [númi-númi-numí-númi] is to be reproduced as «1121». It was found that listeners whose native language was French performed significantly worse than Spanish listeners in reproducing the stress patterns by key strokes. The explanation is that Spanish has lexically contrastive stress, as evidenced by the minimal pairs like tópo («mole») and topó («[he/she/it] met»), while in French, stress does not convey lexical information and there is no equivalent of stress minimal pairs as in Spanish.

An important case of stress «deafness» relates to Persian.[16] The language has generally been described as having contrastive word stress or accent as evidenced by numerous stem and stem-clitic minimal pairs such as /mɒhi/ [mɒ.hí] («fish») and /mɒh-i/ [mɒ́.hi] («some month»). The authors argue that the reason that Persian listeners are stress «deaf» is that their accent locations arise postlexically. Persian thus lacks stress in the strict sense.

Stress «deafness» has been studied for a number of languages, such as Polish[17] or French learners of Spanish.[18]

Spelling and notation for stressEdit

The orthographies of some languages include devices for indicating the position of lexical stress. Some examples are listed below:

- In Modern Greek, all polysyllables are written with an acute accent (´) over the vowel of the stressed syllable. (The acute accent is also used on some monosyllables in order to distinguish homographs, as in η (‘the’) and ή (‘or’); here the stress of the two words is the same.)

- In Spanish orthography, stress may be written explicitly with a single acute accent on a vowel. Stressed antepenultimate syllables are always written with that accent mark, as in árabe. If the last syllable is stressed, the accent mark is used if the word ends in the letters n, s, or a vowel, as in está. If the penultimate syllable is stressed, the accent is used if the word ends in any other letter, as in cárcel. That is, if a word is written without an accent mark, the stress is on the penult if the last letter is a vowel, n, or s, but on the final syllable if the word ends in any other letter. However, as in Greek, the acute accent is also used for some words to distinguish various syntactical uses (e.g. té ‘tea’ vs. te a form of the pronoun tú ‘you’; dónde ‘where’ as a pronoun or wh-complement, donde ‘where’ as an adverb). For more information, see Stress in Spanish.

- In Portuguese, stress is sometimes indicated explicitly with an acute accent (for i, u, and open a, e, o), or circumflex (for close a, e, o). The orthography has an extensive set of rules that describe the placement of diacritics, based on the position of the stressed syllable and the surrounding letters.

- In Italian, the grave accent is needed in words ending with an accented vowel, e.g. città, ‘city’, and in some monosyllabic words that might otherwise be confused with other words, like là (‘there’) and la (‘the’). It is optional for it to be written on any vowel if there is a possibility of misunderstanding, such as condomìni (‘condominiums’) and condòmini (‘joint owners’). See Italian alphabet § Diacritics. (In this particular case, a frequent one in which diacritics present themselves, the difference of accents is caused by the fall of the second «i» from Latin in Italian, typical of the genitive, in the first noun (con/domìnìi/, meaning «of the owner»); while the second was derived from the nominative (con/dòmini/, meaning simply «owners»).

Though not part of normal orthography, a number of devices exist that are used by linguists and others to indicate the position of stress (and syllabification in some cases) when it is desirable to do so. Some of these are listed here.

- Most commonly, the stress mark is placed before the beginning of the stressed syllable, where a syllable is definable. However, it is occasionally placed immediately before the vowel.[19] In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), primary stress is indicated by a high vertical line (primary stress mark:

ˈ) before the stressed element, secondary stress by a low vertical line (secondary stress mark:ˌ). For example, [sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən] or /sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən/. Extra stress can be indicated by doubling the symbol: ˈˈ◌. - Linguists frequently mark primary stress with an acute accent over the vowel, and secondary stress by a grave accent. Example: [sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən] or /sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən/. That has the advantage of not requiring a decision about syllable boundaries.

- In English dictionaries that show pronunciation by respelling, stress is typically marked with a prime mark placed after the stressed syllable: /si-lab′-ə-fi-kay′-shən/.

- In ad hoc pronunciation guides, stress is often indicated using a combination of bold text and capital letters. For example, si-lab-if-i-KAY-shun or si-LAB-if-i-KAY-shun

- In Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian dictionaries, stress is indicated with marks called znaki udareniya (знаки ударения, ‘stress marks’). Primary stress is indicated with an acute accent (´) on a syllable’s vowel (example: вимовля́ння).[20][21] Secondary stress may be unmarked or marked with a grave accent: о̀колозе́мный. If the acute accent sign is unavailable for technical reasons, stress can be marked by making the vowel capitalized or italic.[22] In general texts, stress marks are rare, typically used either when required for disambiguation of homographs (compare в больши́х количествах ‘in great quantities’, and в бо́льших количествах ‘in greater quantities’), or in rare words and names that are likely to be mispronounced. Materials for foreign learners may have stress marks throughout the text.[20]

- In Dutch, ad hoc indication of stress is usually marked by an acute accent on the vowel (or, in the case of a diphthong or double vowel, the first two vowels) of the stressed syllable. Compare achterúítgang (‘deterioration’) and áchteruitgang (‘rear exit’).

- In Biblical Hebrew, a complex system of cantillation marks is used to mark stress, as well as verse syntax and the melody according to which the verse is chanted in ceremonial Bible reading. In Modern Hebrew, there is no standardized way to mark the stress. Most often, the cantillation mark oleh (part of oleh ve-yored), which looks like a left-pointing arrow above the consonant of the stressed syllable, for example ב֫וקר bóqer (‘morning’) as opposed to בוק֫ר boqér (‘cowboy’). That mark is usually used in books by the Academy of the Hebrew Language and is available on the standard Hebrew keyboard at AltGr-6. In some books, other marks, such as meteg, are used.[23]

See alsoEdit

- Accent (poetry)

- Accent (music)

- Foot (prosody)

- Initial-stress-derived noun

- Pitch accent (intonation)

- Rhythm

- Syllable weight

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1955). «Duration and intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stress». Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 27 (4): 765–768. Bibcode:1955ASAJ…27..765F. doi:10.1121/1.1908022.

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1958). «Experiments in the perception of stress». Language and Speech. 1 (2): 126–152. doi:10.1177/002383095800100207. S2CID 141158933.

- ^ a b Monrad-Krohn, G. H. (1947). «The prosodic quality of speech and its disorders (a brief survey from a neurologist’s point of view)». Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 22 (3–4): 255–269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1947.tb08246.x. S2CID 146712090.

- ^ Kochanski, Greg; Shih, Chilin; Jing, Hongyan (2003). «Quantitative measurement of prosodic strength in Mandarin». Speech Communication. 41 (4): 625–645. doi:10.1016/S0167-6393(03)00100-6.

- ^ Mirakyan, Norayr (2016). «The Implications of Prosodic Differences Between English and Armenian» (PDF). Collection of Scientific Articles of YSU SSS. YSU Press. 1.3 (13): 91–96.

- ^ San Duanmu (2000). The Phonology of Standard Chinese. Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- ^ mankind in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Publishers, HarperCollins. «The American Heritage Dictionary entry: mankind». www.ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ «paper bag» in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Ladefoged (1975 etc.) A course in phonetics § 5.4; (1980) Preliminaries to linguistic phonetics p 83

- ^ Beckman, Mary E. (1986). Stress and Non-Stress Accent. Dordrecht: Foris. ISBN 90-6765-243-1.

- ^ R. Silipo and S. Greenberg, Automatic Transcription of Prosodic Stress for Spontaneous English Discourse, Proceedings of the XIVth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS99), San Francisco, CA, August 1999, pages 2351–2354

- ^ Kochanski, G.; Grabe, E.; Coleman, J.; Rosner, B. (2005). «Loudness predicts prominence: Fundamental frequency lends little». The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 118 (2): 1038–1054. Bibcode:2005ASAJ..118.1038K. doi:10.1121/1.1923349. PMID 16158659. S2CID 405045.

- ^ Roca, Iggy (1992). Thematic Structure: Its Role in Grammar. Walter de Gruyter. p. 80.

- ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Peperkamp, Sharon; Sebastián-Gallés, Núria (2001). «A robust method to study stress «deafness»«. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 110 (3): 1606–1618. Bibcode:2001ASAJ..110.1606D. doi:10.1121/1.1380437. PMID 11572370.

- ^ a b Rahmani, Hamed; Rietveld, Toni; Gussenhoven, Carlos (2015-12-07). «Stress «Deafness» Reveals Absence of Lexical Marking of Stress or Tone in the Adult Grammar». PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143968. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043968R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143968. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4671725. PMID 26642328.

- ^ 3:439, 2012, 1-15., Ulrike; Knaus, Johannes; Orzechowska, Paula; Wiese, Richard (2012). «Stress ‘deafness’ in a language with fixed word stress: an ERP study on Polish». Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 439. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00439. PMC 3485581. PMID 23125839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Sebastián-Gallés, N; Navarrete, E; Peperkamp, Sharon (2008). «Persistent stress ‘deafness’: The case of French learners of Spanish». Cognition. 106 (2): 682–706. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.001. hdl:11577/2714082. PMID 17592731. S2CID 2632741.

- ^ Payne, Elinor M. (2005). «Phonetic variation in Italian consonant gemination». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002240. S2CID 144935892.

- ^ a b Лопатин, Владимир Владимирович, ed. (2009). § 116. Знак ударения. Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник (in Russian). Эксмо. ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5.

- ^ Some pre-revolutionary dictionaries, e.g. Dahl’s Explanatory Dictionary, marked stress with an apostrophe just after the vowel (example: гла’сная). See: Dahl, Vladimir Ivanovich (1903). Boduen de Kurtene, Ivan Aleksandrovich (ed.). Толко́вый слова́рь живо́го великору́сского языка́ [Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). Saint Petersburg: M.O. Wolf. p. 4.

- ^ Каплунов, Денис (2015). Бизнес-копирайтинг: Как писать серьезные тексты для серьезных людей (in Russian). p. 389. ISBN 978-5-000-57471-3.

- ^ Aharoni, Amir (2020-12-02). «אז איך נציין את מקום הטעם». הזירה הלשונית – רוביק רוזנטל. Retrieved 2021-11-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External linksEdit

- «Feet and Metrical Stress», The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

- «Word stress in English: Six Basic Rules», Linguapress

- Word Stress Rules: A Guide to Word and Sentence Stress Rules for English Learners and Teachers, based on affixation

-

Word stress, its acoustic

nature. -

The

linguistic function of a word stress. -

Degree

and position of a word stress.

-1-

The

sequence of syllables in the word is not pronounced identically. The

syllable or syllables which are pronounced with more prominence than

the other syllables of the word are said to be stressed or accented.

The correlation of varying prominences of syllables in a word is

understood as the accentual structure of the word.

According

to A.C. Gimson, the effect of prominence is achieved by any or all of

four factors: force, tone, length and vowel colour. The dynamic

stress implies greater force with which the syllable is pronounced.

In other words in the articulation of the stressed syllable greater

muscular energy is produced by the speaker. The European languages

such as English, German, French, Russian are believed to possess

predominantly dynamic word stress. In Scandinavian languages the word

stress is considered to be both dynamic and musical (e.g. in Swedish,

the word komma

(comma) is distinguished from the word komma

(come) by a difference in tones). The musical (tonic) word stress is

observed in Chinese, Japanese. It is effected by the variations of

the voice pitch in relation to neighbouring syllables. In Chinese the

sound sequence “chu” pronounced with the level tone means “pig”,

with the rising tone “bamboo”, and with the falling tone “to

live”.

It is fair

to mention that there is a terminological confusion in discussing the

nature of stress. According to D. Crystal, the terms “heaviness,

intensity, amplitude, prominence, emphasis, accent, stress” tend to

be used synonymously by most writers. The discrepancy in terminology

is largely due to the fact that there are 2 major views depending on

whether the productive or receptive aspects of stress are discussed.

The main

drawback with any theory of stress based on production of speech is

that it only gives a partial explanation of the phenomenon but does

not analyze it on the perceptive level.

Instrumental

investigations study the physical nature of word stress. On the

acoustic level the counterpart of force is the intensity of the

vibrations of the vocal cords of the speaker which is perceived by

the listener as loudness. Thus the greater energy with which the

speaker articulates the stressed syllable in the word is associated

by the listener with greater loudness. The acoustic counterparts of

voice pitch and length are frequency and duration respectively. The

nature of word stress in Russian seems to differ from that in

English. The quantitative component plays a greater role in Russian

accentual structure than in English word accent. In the Russian

language of full formation and full length in unstressed positions,

they are always reduced. Therefore the vowels of full length are

unmistakably perceived as stressed. In English the quantitative

component of word stress is not of primary importance because of the

non-reduced vowels in the unstressed syllables which sometimes occur

in English words (e.g. “transport”, “architect”).

-2-

In discussing accentual

structure of English words we should turn now to the functional

aspect of word stress. In language the word stress performs 3

functions:

-

constitutive– word

stress constitutes a word, it organizes the syllables of a word into

a language unit. A word does not exist without the word stress. Thus

the function is constitutive – sound continuum becomes a phrase

when it is divided into units organized by word stress into words. -

Word

stress enables a person to identify a succession of syllables as a

definite accentual pattern of a word. This function is known as

identificatory (or

recognitive). -

Word

stress alone is capable of differentiating the meaning of words or

their forms, thus performing its distinctive

function. The accentual patterns of

words or the degrees of word stress and their positions form

oppositions (“/import – im /port”, “/present – pre

/sent”).

-3-

There are

actually as many degrees of word stress in a word as there are

syllables. The British linguists usually distinguish three degrees of

stress in the word. The primary stress is the strongest (e.g.

exami/nation), the secondary stress is the second strongest one (e.g.

ex,ami/nation). All the other degrees are termed “weak stress”.

Unstressed syllables are supposed to have weak stress. The American

scholars, B. Bloch and J. Trager, find 4 contrastive degrees

of word stress: locid, reduced locid, medial and weak.

In

Germanic languages the word stress originally fell on the initial

syllable or the second syllable, the root syllable in the English

words with prefixes. This tendency was called recessive. Most English

words of Anglo-Saxon origin as well as the French borrowings are

subjected to this recessive tendency.

Languages

are also differentiated according to the placement of word stress.

The traditional classification of languages concerning the place of

stress in a word is into those with a

fixed stress and a free stress. In

languages with a fixed stress the occurrence of the word stress is

limited to a particular syllable in a multisyllabic word. For

example, in French the stress falls on the last syllable of the word

(if pronounced in isolation), in Finnish and Czech it is fixed on the

first syllable.

Some

borrowed words retain their stress.

In languages with a free

stress its place is not confined to a specific position in the word.

The free placement of stress is exemplified in the English and

Russian languages

(e.g. E. appetite – begin –

examination

R.

озеро – погода

– молоко)

The word

stress in English as well as in Russian is not only free but it may

also be shifting performing semantic function of differentiating

lexical units, parts of speech, grammatical forms. It is worth noting

that in English word stress is used as a means of word-building (e.g.

/contrast – con/trast, /music – mu /sician).

Questions:

-

What

features characterize word accent? -

Identify

the functions of word stress. -

What

are the types of word stress? -

Do AmE and

BE have any differences in the system of word stress? Give your

examples.

Lecture 8. Intonation

-

Intonation.

-

The

linguistic function of intonation. -

The

implications of a terminal tone. -

Rhythm.

-1-

Intonation is a language

universal. There are no languages which are spoken as a monotone,

i.e. without any change of prosodic parametres. On perceptional level

intonation is a complex, a whole, formed by significant variations of

pitch, loudness and tempo closely related. Some linguists regard

speech timber as the fourth component of intonation. Though it

certainly conveys some shades of attitudinal or emotional meaning

there’s no reason to consider it alongside with the 3

prosodic components of intonation (pitch, loudness and tempo).

Nowadays the term “prosody” substitutes the term “intonation”.

On the acoustic level pitch

correlates with the fundamental frequency of the vibrations of the

vocal cords; loudness correlates with the amplitude of vibrations;

tempo is a correlate of time during which a speech unit lasts.

The auditory level is very

important for teachers of foreign languages. Each syllable of the

speech chain has a special pitch colouring. Some of the syllables

have significant moves of tone up and down. Each syllable bears a

definite amount of loudness. Pitch movements are inseparably

connected with loudness. Together with the tempo of speech they form

an intonation pattern which is the basic unit of intonation.

An intonation pattern contains

one nucleus and may contain other stressed or unstressed syllables

normally preceding or following the nucleus. The boundaries of an

intonation pattern may be marked by stops of phonation, that is

temporal pauses.

Intonation patterns serve to

actualize syntagms in oral speech. The syntagm

is a group of words which are semantically and syntactically

complete. In phonetics they are called intonation

groups. The

intonation group is a stretch of speech which may have the length of

the whole phrase. But the phrase often contains more than one

intonation group. The number of them depends on the length of phrase

and the degree of semantic impotence or emphasis given to various

parts of it. The position of intonation groups may affect the

meaning.

-2-

The communicative

function of

intonation is realized in various ways which can be grouped under

five – six general headings:

-

to

structure the intonation content of a textual unit. So as to show

which information is new or can not be taken for granted, as against

information which the listener is assumed to possess or to be able

to acquire from the context, that is given information; -

to

determine the speech function of a phrase, to indicate whether it is

intended as a statement, question, etc; -

to

convey connotational meanings of attitude, such as surprise, etc. In

the written form we are given only the lexics and the grammar; -

to

structure a text. Intonation is an organizing mechanism. It divides

texts into smaller parts and on the other hand it integrates them

forming a complete text; -

to

differentiate the meaning of textual units of the same phonetic

structure and the same lexical composition (distinctive or

phonological function); -

to

characterize a particular style or variety of oral speech which may

be called a stylistic function.

-3-

Classification of intonation

patterns:

Different combinations of

pitch sections (pre-heads, heads and nuclei) may result in more than

one hundred pitch-and-stress patterns. But it is not necessary to

deal with all of them, because some patterns occur very rarely. So,

attention must be concentrated on the commonest ones:

-

The Low (Medium) Fall

pitch-and-stress group -

The

High Fall group -

Rise

Fall group -

The

Low Rise group -

The

High Rise group -

The

Fall Rise group -

The

Rise-Fall-Rise group -

The

Mid-level group

No intonation pattern is used

exclusively with this or that sentence type. Some sentences are more

likely to be said with one intonation pattern than with any other. So

we can speak about “common intonation” for a particular type of

sentence.

-

Statements are most widely

used with the Low Fall preceded by the Falling or the High level

Head. They are final, complete and definite. -

Commands,

with the Low Fall are very powerful, intense, serious and strong. -

Exclamations

are very common with the High Fall.

-4-

We cannot fully describe

English intonation without reference to speech rhythm. Rhythm

seems to be a kind of framework of speech organization. Some

linguists consider it to be one of the components of intonation.

Rhythm is understood as

periodicity in time and space. We find it everywhere in life. Rhythm

as a linguistic notion is realized in lexical, syntactical and

prosodic means and mostly in their combinations.

In speech,

the type of rhythm depends on the language. Linguists divide

languages into two groups:

-

syllable-timed(French, Spanish);

-

stress-timed(English, German, Russian).

In a

syllable-timed language the speaker gives an approximately equal

amount of time to each syllable, whether the syllable is stressed or

unstressed.

In a

stress-timed language the rhythm is based on a larger unit, than

syllable. Though the amount of time given on each syllable varies

considerably, the total time of uttering each rhythmic unit is

practically unchanged. The stressed syllables of a rhythmic unit form

peaks of prominence. They tend to be pronounced at regular intervals

no matter how many unstressed syllables are located between every 2

stressed ones. Thus the distribution of time within the rhythmic unit

is unequal.

Speech

rhythm is traditionally defined as recurrence of stressed syllables

at more or less equal intervals of time in a speech continuum.

Questions:

-

Name

the basic components of intonation. -

What

is the connection between pitch and tempo? -

What

for do we need different nuclear tones? -

Which

nuclei are the commonest?

Lecture

9. Territorial varieties of English pronunciation

-

Varieties

of language. -

English

variants.

-1-

The

varieties of the language are conditioned by language communities

ranging from small groups to nations. National

language is the language of a nation,

the standard of its form, the language of a nation’s literature.

The literary spoken form has its national

pronunciation standard. A “standard”

may be defined as a socially accepted variety of a language

established by a codified norm of correctness. It is generally

accepted that for the “English English” it is “Received

Pronunciation” or RP; for the “American English” – “General

American pronunciation”; for the Australian English – “Educated

Australian”.

Though

every national variant of English has considerable differences in

pronunciation, lexics and grammar, they all have much in common which

gives us ground to speak of one and the same language – the English

language.

Every

national variety of the language falls into territorial

or regional dialects. Dialects are

distinguished from each other by differences in pronunciation,

grammar and vocabulary. When we refer to varieties in pronunciation

only, we use the word “accent”.

The social

differentiation of language is closely connected with the social

differentiation of society. Every language community, ranging from a

small group to a nation has its own social

dialect, and consequently, its own

social accent.

The

“language situation” may be spoken about in terms of the

horizontal and vertical differentiations of the language, the first

in accordance with the sphere of social activity, the second – with

its situational variability. Situational varieties of the language

are called functional dialects or functional styles and situational

pronunciation varieties – situational accents or phonostyles.

-2-

Nowadays

two main types of English are spoken in the English-speaking world:

English English and American English.

According to British

dialectologists (P. Trudgill, J. Hannah, A. Hughes and others) the

following variants of English are referred to the English-based

group: English English, Welsh English, Australian English, New

Zealand English; to the American-based group: United States English,

Canadian English.

Scottish English and Irish

English fall somewhere between the two being somewhat by themselves.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

What is word stress?

Word stress, also called lexical stress, is the emphasis a speaker places on a specific syllable in a multi-syllable word.

Word stress is especially hard for non-native speakers to master. While there are a few conventions and general rules governing which syllable is stressed in a word based on its spelling alone, these conventions are often unreliable.

Before we look at these conventions and their exceptions, let’s discuss how we can indicate syllables and word stress in writing.

Indicating syllables in writing

In this section, we’ll be using different symbols to indicate syllable division in words. For the normal spelling of words, we’ll be using a symbol known as an interpunct ( · ) (also called a midpoint, middle dot, or centered dot). For example, the word application would appear as app·li·ca·tion.

When the pronunciation of a word is transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), there are three different symbols we use. For syllables that receive the primary stress, we use a short vertical line above and immediately before the syllable being emphasized ( ˈ ); for secondary stress, we use the same vertical line, but it appears below and before the syllable ( ˌ ); and, while this guide usually does not mark them in IPA transcriptions, we will indicate unstressed syllables in this section with periods. Using application as an example again, its pronunciation would be transcribed in IPA as /ˌæp.lɪˈkeɪ.ʃən/.

Written syllables vs. spoken syllables

The syllable breakdowns in the written “dictionary” form of words are often divided slightly differently compared to the phonetic “spoken” form used in IPA transcriptions.

Specifically, the written form divides syllables according to established syllable “types,” based on spelling patterns such as double consonants, short vowels contained within two consonants, and vowel digraphs. The spoken form, on the other hand, divides syllables according to the phonetic pronunciation of the word, and the difference between these two can sometime lead to syllable breakdowns that don’t look like they correspond to one another. For example, the word learning is divided in the dictionary as learn·ing, but it is divided as /ˈlɜr.nɪŋ/ in IPA transcription—the placement of the first N is not the same.

Because this part of the guide is more concerned with the phonetic placement of word stress rather than the technical breakdown of syllables (as found in dictionary entries), the examples we use will try to match the written form as closely as possible to the spoken form. Looking at the learning example again, we would divide the syllables as lear·ning to match its IPA transcription. Just be aware that these will often be slightly different to what one may find in a dictionary. For more technical information on how syllables are formed and divided within words, check out the chapter on Syllables.

Primary vs. secondary stress

Every word has one syllable that receives a primary stress—that is, it is vocally emphasized more than any other syllable. Some longer words also have a secondary stress, which is more emphatic than the unstressed syllables but not as strong as the primary stress. (Some words can even have more than one secondary stress.)

Let’s look at some examples, with the primary stress in bold and the secondary stress in italics:

- ab·sen·tee (/ˌæb.sənˈti/)

- cem·e·ter·y (/ˈsɛm.ɪˌtɛr.i/)

- dis·be·lief (/ˌdɪs.bɪˈlif/)

- in·for·ma·tion (/ˌɪn fərˈmeɪ ʃən/)

- labo·ra·tor·y (/ˈlæb.rəˌtɔr.i/; the initial O is usually silent)

- mil·i·tar·y (/ˈmɪl.ɪˌtɛr.i/)

- or·din·ar·y (/ˈɔr.dənˌɛr.i/)

- sec·re·tar·y (/ˈsɛk.rɪˌtɛr.i/)

- tem·po·rar·y (/ˈtɛm.pəˌrɛr.i/)

- un·a·pol·o·get·ic (/ˌʌn.əˌpɑl.əˈʤɛt.ɪk/)

Unfortunately, secondary stress is extremely unpredictable. Primary stress, on the other hand, can often be predicted according to a few different conventions.

Determining word stress

There are only two consistent, reliable rules about word stress in English:

- 1. Only the vowel sound within a syllable is stressed; stress is not applied to consonant sounds.

- 2. Any given word, even one with many syllables, will only have one syllable that receives the primary stress in speech. Some longer words also receive a secondary stress, which we’ll look at more closely further on. (By definition, single-syllable words only ever have a single stress, though certain function words can be unstressed altogether, which we’ll discuss later.)

However, determining which syllable is emphasized in a given word is not always straightforward, as a word’s spelling is usually not enough on its own to let us know the appropriate stress. There are a few general conventions that can help make this easier to determine, but there are many exceptions and anomalies for each.

Determining stress based on word type

One common pronunciation convention many guides provide is that nouns and adjectives with two or more syllables will have stress placed on the first syllable, while verbs and prepositions tend to have their stress on the second syllable. While there are many examples that support this convention, it is also very problematic because there are many exceptions that contradict it.

Let’s look at some examples that support or contradict this convention.

Nouns and adjectives will have stress on the first syllable

|

Nouns |

Adjectives |

|---|---|

|

app·le (/ˈæp.əl/) bott·le (/ˈbɑt.əl/) busi·ness (/ˈbɪz.nɪs/; the I is silent) cherr·y (/ˈʧɛr.i/) cli·mate (/ˈklaɪ.mɪt/) crit·ic (/ˈkrɪt.ɪk/) dia·mond (/ˈdaɪ.mənd/) el·e·phant (/ˈɛl.ə.fənt/) en·ve·lope (/ˈɛnvəˌloʊp/) fam·i·ly (/ˈfæm.ə.li/) In·ter·net (/ˈɪn.tərˌnɛt/) knowl·edge (/ˈnɑl.ɪʤ/) mu·sic (/ˈmju.zɪk/) pa·per (/ˈpeɪ.pər/) sam·ple (/ˈsæm.pəl/) satch·el (/ˈsætʃ.əl/) ta·ble (/ˈteɪ.bəl/) tel·e·phone (/ˈtɛl.əˌfoʊn /) ton·ic (/ˈtɑn.ɪk/) win·dow (/ˈwɪn.doʊ/) |

clev·er (/ˈklɛv.ər/) comm·on (/ˈkɑm.ən/) diff·i·cult (/ˈdɪf.ɪˌkʌlt/) fa·vor·ite (/ˈfeɪ.vər.ɪt/) fem·i·nine (/ˈfɛm.ə.nɪn/) funn·y (/ˈfʌn.i/) happ·y (/ˈhæp.i/) hon·est (/ɑn.ɪst/) litt·le (/ˈlɪt.əl/) mas·cu·line (/ˈmæs.kju.lɪn/) narr·ow (/ˈnær.oʊ/) or·ange (/ˈɔr.ɪnʤ/) pleas·ant (/ˈplɛz.ənt/) pre·tty (/ˈprɪ.ti/) pur·ple (/ˈpɜr.pəl/) qui·et (/ˈkwaɪ.ət/) sim·ple (/ˈsɪm.pəl/) sub·tle (/ˈsʌt.əl/) trick·y (/ˈtrɪk.i/) ug·ly (/ˈʌg.li/) |

As we said already, though, there are many exceptions to this convention for both nouns and adjectives. Let’s look at some examples:

|

Nouns |

Adjectives |

|---|---|

|

ba·na·na (/bə.ˈnæ.na/) ca·nal (/kə.ˈnæl/) com·put·er (/kəm.ˈpju.tər/) de·fence (/dɪ.ˈfɛns/) des·sert (/dɪ.ˈzɜrt/) di·sease (/dɪ.ˈziz/) ex·tent (/ɪk.ˈstɛnt/) ho·tel (/hoʊ.ˈtɛl/) ma·chine (/mə.ˈʃin/) pi·a·no (/pi.ˈæ.noʊ/) po·ta·to (/pə.ˈteɪˌtoʊ/) re·ceipt (/rɪ.ˈsit/) re·venge (/rɪ.ˈvɛnʤ/) suc·cess (/sɪk.ˈsɛs/) |

a·live (/ə.ˈlaɪv/) a·noth·er (/əˈnʌð.ər/) com·plete (/kəm.ˈplit/) dis·tinct (/dɪsˈtinkt/) e·nough (/ɪ.ˈnʌf/) ex·pen·sive (/ɪk.ˈspɛn.sɪv/) ex·tinct (/ɪk.ˈtiŋkt/) i·ni·tial (/ɪ.ˈnɪ.ʃəl/) in·tense (/ɪn.ˈtɛns/) po·lite (/pəˈlaɪt/) re·pet·i·tive (/rɪ.ˈpɛt.ɪ.tɪv/) un·think·a·ble (/ʌnˈθɪŋk.ə.bəl/) |

Verbs and prepositions will have stress on the second syllable

|

Verbs |

Prepositions |

|---|---|

|

a·pply (/əˈplaɪ/) be·come (/bɪˈkʌm/) com·pare (/kəmˈpɛr/) di·scuss (/dɪˈskʌs/) ex·plain (/ɪkˈspleɪn/) ful·fil (/fʊlˈfɪl/) in·crease (/ɪnˈkris/) ha·rass (/həˈræs/) la·ment (/ləˈmɛnt/) ne·glect (/nɪˈglɛkt/) pre·vent (/prɪˈvɛnt/) qua·dru·ple (/kwɑˈdru.pəl/) re·ply (/rɪˈplaɪ/) suc·ceed (/səkˈsid/) tra·verse (/trəˈvɜrs/) un·furl (/ʌnˈfɜrl/) with·hold (/wɪθˈhoʊld/) |

a·bout (/əˈbaʊt/) a·cross (/əˈkrɔs/) a·long (/əˈlɔŋ/) a·mong (/əˈmʌŋ/) a·round (/əˈraʊnd/) be·hind (/bɪˈhaɪnd/) be·low (/bɪˈloʊ/) be·side (/bɪˈsaɪd/) be·tween (/bɪˈtwin/) de·spite (/dɪˈspaɪt/) ex·cept (/ɪkˈsɛpt/) in·side (/ˌɪnˈsaɪd/) out·side (/ˌaʊtˈsaɪd/) un·til (/ʌnˈtɪl/) u·pon (/əˈpɑn/) with·in (/wɪðˈɪn/) with·out (/wɪðˈaʊt/) |

As with nouns and adjectives, there are a huge number of exceptions that have primary stress placed on the first or third syllable. In fact, almost every verb beginning with G, H, J, K, L, and M has its primary stress placed on the first syllable, rather than the second.

Let’s look at a few examples:

|

Verbs |

Prepositions |

|---|---|

|

ar·gue (/ˈɑr.gju/) beck·on (/ˈbɛk.ən/) can·cel (/ˈkæn.səl/) dom·i·nate (/ˈdɑm.əˌneɪt/) en·ter·tain (/ˌɛn.tərˈteɪn/) fas·ten (/ˈfæs.ən/) gam·ble (/ˈgæm.bəl/) hin·der (/ˈhɪn.dər/) i·so·late (/ˈaɪ.səˌleɪt/) jin·gle (/ˈʤɪŋ.gəl/) kin·dle (/ˈkɪn.dəl/) leng·then (/ˈlɛŋk.θən/) man·age (/ˈmæn.ɪʤ/) nour·ish (/ˈnɜr.ɪʃ/) or·ga·nize (/ˈɔr.gəˌnaɪz/) per·ish (/ˈpɛr.ɪʃ/) qua·ver (/ˈkweɪ.vər/) ram·ble (/ˈræm.bəl/) sa·vor (/ˈseɪ.vər/) threat·en (/ˈθrɛt.ən/) un·der·stand (/ˌʌn.dərˈstænd/) van·ish (/ˈvæn.ɪʃ/) wan·der (/ˈwɑn.dər/) yo·del (/ˈjoʊd.əl/) |

af·ter (/ˈæf.tər/) dur·ing (/ˈdʊr.ɪŋ/) in·to (/ˈɪn.tu/) on·to (/ˈɑn.tu/) un·der (/ˈʌn.dər/) |

Initial-stress-derived nouns

As we saw previously, we commonly place stress on the first syllable of a noun. When a word can operate as either a noun or a verb, we often differentiate the meanings by shifting the stress from the second syllable to the first (or initial) syllable—in other words, these nouns are derived from verbs according to their initial stress.

Let’s look at a few examples of such words that change in pronunciation when functioning as nouns or verbs:

|

Word |

Noun |

Verb |

|---|---|---|

|

contest |

con·test (/ˈkɑn.tɛst/) Meaning: “a game, competition, or struggle for victory, superiority, a prize, etc.” |

con·test (/kənˈtɛst/) Meaning: “to dispute, contend with, call into question, or fight against” |

|

desert |

des·ert (/ˈdɛz.ərt/) Meaning: “a place where few things can grow or live, especially due to an absence of water” |

de·sert (/dɪˈzɜrt/) Meaning: “to abandon, forsake, or run away from” |

|

increase |

in·crease (/ˈɪn.kris/) Meaning: “the act or process of growing larger or becoming greater” |

in·crease (/ɪnˈkris/) Meaning: “to grow larger or become greater (in size, amount, strength, etc.)” |

|

object |

ob·ject (/ˈɑb.ʤɛkt/) Meaning: “any material thing that is visible or tangible” |

ob·ject (/əbˈʤɛkt/) Meaning: “to present an argument in opposition (to something)” |

|

permit |

per·mit (/ˈpɜr.mɪt/) Meaning: “an authoritative or official certificate of permission; license” |

per·mit (/pərˈmɪt/) Meaning: «to allow to do something» |

|

present |

pres·ent (/ˈprɛz.ənt/) Meaning: “the time occurring at this instant” or “a gift” |

pre·sent (/prɪˈzɛnt/) Meaning: “to give, introduce, offer, or furnish” |

|

project |

proj·ect (/ˈprɑʤ.ɛkt/) Meaning: “a particular plan, task, assignment, or undertaking” |

pro·ject (/prəˈʤɛkt/) Meaning: “to estimate, plan, or calculate” or “to throw or thrust forward” |

|

rebel |

reb·el (/ˈrɛb.əl/) Meaning: “a person who revolts against a government or other authority” |

re·bel (/rɪˈbɛl/) Meaning: “to revolt or act in defiance of authority” |

|

record |

rec·ord (/ˈrɛk.ərd/) Meaning: “information or knowledge preserved in writing or the like” or “something on which sound or images have been recorded for subsequent reproduction” |

re·cord (/rəˈkɔrd/) Meaning: “to set down in writing or the like” |

|

refuse |

ref·use (/ˈrɛf.juz/) Meaning: “something discarded or thrown away as trash” |

re·fuse (/rɪˈfjuz/) Meaning: “to decline or express unwillingness to do something” |

|

subject |

sub·ject (/ˈsʌb.ʤɛkt/) Meaning: “that which is the focus of a thought, discussion, lesson, investigation, etc.” |

sub·ject (/səbˈʤɛkt/) Meaning: “to bring under control, domination, authority” |

Although this pattern is very common in English, it is by no means a rule; there are just as many words that function as both nouns and verbs but that have no difference in pronunciation. For instance:

|

Word |

Noun |

Verb |

|---|---|---|

|

amount |

a·mount (/əˈmaʊnt/) |

a·mount (/əˈmaʊnt/) |

|

answer |

an·swer (/ˈæn.sər/) |

an·swer (/ˈæn.sər/) |

|

attack |

a·ttack (/əˈtæk/) |

a·ttack (/əˈtæk/) |

|

challenge |

chall·enge (/ˈtʃæl.ɪnʤ/) |

chall·enge (/ˈtʃæl.ɪnʤ/) |

|

contact |

con·tact (/ˈkɑn.tækt/) |

con·tact (/ˈkɑn.tækt/) |

|

control |

con·trol (/kənˈtroʊl/) |

con·trol (/kənˈtroʊl/) |

|

forecast |

fore·cast (/ˈfɔrˌkæst/) |

fore·cast (/ˈfɔrˌkæst/) |

|

monitor |

mon·i·tor (/ˈmɑn.ɪ.tər/) |

mon·i·tor (/ˈmɑn.ɪ.tər/) |

|

pepper |

pep·per (/ˈpɛp.ər/) |

pep·per (/ˈpɛp.ər/) |

|

report |

re·port (/rɪˈpɔrt/) |

re·port (/rɪˈpɔrt/) |

|

respect |

re·spect (/rɪˈspɛkt/) |

re·spect (/rɪˈspɛkt/) |

|

support |

su·pport (/səˈpɔrt/) |

su·pport (/səˈpɔrt/) |

|

witness |

wit·ness (/ˈwɪt.nɪs/) |

wit·ness (/ˈwɪt.nɪs/) |

|

worry |

worr·y (/ˈwɜr.i/) |

worr·y (/ˈwɜr.i/) |

Word stress in compound words

Compound nouns and compound verbs typically create pronunciation patterns that help us determine which of their syllables will have the primary stress. Compound adjectives, on the other hand, are most often pronounced as two separate words, with each receiving its own primary stress, so we won’t be looking at them here.

We’ll also briefly look at reflexive pronouns. Although these aren’t technically compounds, they have a similarly predictable stress pattern.

Compound nouns

A compound noun is a noun consisting of two or more words working together as a single unit to name a person, place, or thing. Compound nouns are usually made up of two nouns or an adjective and a noun, but other combinations are also possible, as well.

In single-word compound nouns, whether they are conjoined by a hyphen or are simply one word, stress is almost always placed on the first syllable. For example:

- back·pack (/ˈbækˌpæk/)

- bath·room (/ˈbæθˌrum/)

- draw·back (/ˈdrɔˌbæk/)

- check-in (/ˈtʃɛkˌɪn/)

- foot·ball (/ˈfʊtˌbɔl/)

- hand·bag (/ˈhændˌbæɡ/)

- green·house (/ˈgrinˌhaʊs/)

- hair·cut (/ˈhɛrˌkʌt/)

- log·in (/ˈsʌn.ɪnˌlɔ/)

- mo·tor·cy·cle (/ˈmoʊ.tərˌsaɪ kəl/)

- on·look·er (/ˈɑnˌlʊkər/)

- pas·ser·by (/ˈpæs.ərˌbaɪ/)

- son-in-law (/ˈsʌn.ɪnˌlɔ/)

- ta·ble·cloth (/ˈteɪ.bəlˌklɔθ/)

- wall·pa·per (/ˈwɔlˌpeɪ.pər/)

- web·site (/ˈwɛbˌsaɪt/)

One notable exception to this convention is the word af·ter·noon, which has its primary stress on the third syllable: /ˌæf.tərˈnun/.

Single-word compound verbs

The term “compound verb” can refer to a few different things: phrasal verbs, which consist of a verb paired with a specific preposition or particle to create a new, unique meaning; prepositional verbs, in which a preposition connects a noun to a verb; combinations with auxiliary verbs, which form tense and aspect; and single-word compounds, in which a verb is combined with a noun, preposition, or another verb to create a new word. For the first three types of compound verbs, each word is stressed individually, but single-word compounds have a unique pronunciation pattern that we can predict.

For most single-word compound verbs, stress will be on the first syllable. However, if the first element of the compound is a two-syllable preposition, stress will be placed on the second element. For example:

- air-con·dit·ion (/ˈeɪr.kənˌdɪʃ.ən/)

- ba·by·sit (/ˈbeɪ.biˌsɪt/)

- cop·y·ed·it (/ˈkɑ.piˌɛd.ɪt/)

- day·dream (/ˈdeɪˌdrim/)

- down·load (/ˈdaʊnˌloʊd/)

- ice-skate (/ˈaɪsˌskeɪt/)

- jay·walk (/ˈʤeɪˌwɔk/)

- kick-start (/ˈkɪkˌstɑrt/)

- o·ver·heat (/ˌoʊ.vərˈhit/)

- proof·read (/ˈprufˌrid/)

- stir-fry (/ˈstɜrˌfraɪ/)

- test-drive (/ˈtɛstˌdraɪv/)

- un·der·cook (/ˌʌndərˈkʊk/)

- wa·ter·proof (/ˈwɔ.tərˌpruf/)

Reflexive Pronouns

Reflexive pronouns are not technically compounds (“-self” and “-selves” are suffixes that attach to a base pronoun), but they look and behave similarly. In these words, -self/-selves receives the primary stress.

- my·self (/maɪˈsɛlf/)

- her·self (/hərˈsɛlf/)

- him·self (/hɪmˈsɛlf/)

- it·self (/ɪtˈsɛlf/)

- one·self (/wʌnˈsɛlf/)

- your·self (/jərˈsɛlf/)

- your·selves (/jərˈsɛlvz/)

- them·selves (/ðəmˈsɛlvz/)

Word stress dictated by suffixes

While the stress in many words is very difficult to predict, certain suffixes and other word endings will reliably dictate where stress should be applied within the word. This can be especially useful for determining the pronunciation of longer words. (There are still some exceptions, but much fewer than for the other conventions we’ve seen.)

For the suffixes we’ll look at, primary stress is either placed on the suffix itself, one syllable before the suffix, or two syllables before the suffix. Finally, we’ll look at some suffixes that don’t affect a word’s pronunciation at all.

Stress is placed on the suffix itself

“-ee,” “-eer,” and “-ese”

These three suffixes all sound similar, but they have different functions: “-ee” indicates someone who benefits from or is the recipient of the action of a verb; “-eer” indicates someone who is concerned with or engaged in a certain action; and “-ese” is attached to place names to describe languages, characteristics of certain nationalities, or (when attached to non-place names) traits or styles of particular fields or professions.

For example:

|

-ee |

-eer |

-ese |

|---|---|---|

|

ab·sen·tee (/ˌæbsənˈti/) a·tten·dee (/əˌtɛnˈdi/) de·tai·nee (/dɪˈteɪˈni/) in·ter·view·ee (/ɪnˌtər.vyuˈi/) li·cen·see (/ˌlaɪ.sənˈsi/) mort·ga·gee (/ˌmɔr.gəˈʤi/) pa·ro·lee (/pə.roʊˈli/) ref·e·ree (/ˌrɛf.əˈri/) ref·u·gee (/ˌrɛf.jʊˈʤi/) trai·nee (/treɪˈni/) warr·an·tee (/ˌwɔr.ənˈti/) |

auc·tio·neer (/ˌɔk.ʃəˈnɪər/) com·man·deer (/ˌkɑ.mənˈdɪər/) dom·i·neer (/ˌdɑm.ɪˈnɪər/) en·gi·neer (/ˌɛn.ʤɪˈnɪər/) moun·tai·neer (/ˌmaʊn.tɪˈnɪər/) prof·i·teer (/ˌprɑf.ɪˈtɪər/) pupp·e·teer (/ˌpʌp.ɪˈtɪər/) rack·e·teer (/ˌræk.ɪˈtɪər/) vol·un·teer (/ˌvɑl.ɪnˈtɪər/) |

Chi·nese (/tʃaɪˈniz/) Jap·a·nese (/ˌʤæp.əˈniz/) jour·na·lese (/ˌʤɜr.nəˈliz/) Leb·a·nese (/ˌlɛb.əˈniz/) le·ga·lese (/ˌli.gəˈliz/) Mal·tese (/ˌmɔlˈtiz/) Por·tu·guese (/ˌpɔr.tʃəˈgiz/) Si·a·mese (/ˌsaɪ.əˈmiz/) Tai·wa·nese (/ˌtaɪ.wɑˈniz/) Vi·et·na·mese (/viˌɛt.nɑˈmiz/) |

(The word employee usually follows this same pattern, but it is one of a few words that has its primary stress on different syllables depending on dialect and personal preference.)

Some other words that feature the “-ee” ending also follow the same pattern, even though they are not formed from another base word. For instance:

- chim·pan·zee (/ˌtʃɪm.pænˈzi/)

- guar·an·tee (/ˌgær.ənˈti/)

- jam·bo·ree (/ˌʤæm.bəˈri/)

- ru·pee (/ru.ˈpi/)

Be careful, though, because other words don’t follow the pattern. For example:

- ap·o·gee (/ˈæp.əˌʤi/)

- co·ffee (/ˈkɔ.fi/)

- co·mmit·tee (/kəˈmɪt.i/)

- kedg·e·ree (/ˈkɛʤ.əˌri/)

- te·pee (/ˈti.pi/)

“-ology”

This suffix is used to denote fields of scientific study or discourse; sets of ideas, beliefs, or principles; or bodies of texts or writings. Primary stress is placed on the syllable in which “-ol-” appears. For example:

- a·strol·o·gy (/əˈstrɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- bi·ol·o·gy (/baɪˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- car·di·ol·o·gy (/ˌkɑr.diˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- e·col·o·gy (/ɪˈkɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- ge·ol·o·gy (/ʤiˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- i·de·ol·o·gy (/ˌaɪ.diˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- lex·i·col·o·gy (/ˌlɛk.sɪˈkɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- meth·o ·dol·o·gy (/ˌmɛθ.əˈdɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- neu·rol·o·gy (/nʊˈrɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- psy·chol·o·gy (/saɪˈkɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- ra·di·ol·o·gy (/reɪ.diˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- so·ci·ol·o·gy (/ˌsoʊ.siˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- tech·nol·o·gy (/tɛkˈnɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- u·rol·o·gy (/jʊˈrɑl.ə.ʤi/)

- zo·ol·o·gy (/zuˈɑl.ə.ʤi/)

“-osis”

This suffix is used to form the names of diseases, conditions, and other medical processes. Stress is placed on the syllable in which “-o-” appears

- ac·i·do·sis (/ˌæs.ɪˈdoʊ.sɪs/)

- cir·rho·sis (/sɪˈroʊ.sɪs/)

- di·ag·no·sis (/ˌdaɪ.əgˈnoʊ.sɪs/)

- en·do·me·tri·o·sis (/ˌɛn.doʊˌmi.triˈoʊ.sɪs/)

- fib·ro·sis (/faɪˈbroʊ.sɪs/)

- hyp·no·sis (/hɪpˈnoʊ.sɪs/)

- mi·to·sis (/maɪˈtoʊ.sɪs/)

- ne·cro·sis (/nəˈkroʊ.sɪs/)

- os·te·o·po·ro·sis (/ˌɑs.ti.oʊ.pəˈroʊ.sɪs/)

- prog·no·sis (/prɑgˈnoʊ.sɪs/)

- sym·bi·o·sis (/ˌsɪm.biˈoʊ.sɪs/)

- tu·ber·cu·lo·sis (/tʊˌbɜr.kjəˈloʊ.sɪs/)

Stress is placed on syllable immediately before the suffix

“-eous” and -“ious”

These two suffixes are both used to form adjectives meaning “having, characterized by, or full of,” most often attaching to base nouns.

In many cases, the E and I are pronounced individually, but for many other words they are silent, instead serving to mark a change in pronunciation for the previous consonant. For example:

|

-eous |

-ious |

|---|---|

|

ad·van·ta·geous (/ˌæd vənˈteɪ.ʤəs/) boun·te·ous (/ˈbaʊn.ti.əs/) cou·ra·geous (/kəˈreɪ.ʤəs/) dis·cour·te·ous (/dɪsˈkɜr.ti.əs/) ex·tra·ne·ous (/ɪkˈstreɪ.ni.əs/) gas·e·ous (/ˈgæs.i.əs/) hid·e·ous (/ˈhɪd.i.əs/) ig·ne·ous (/ˈɪg.ni.əs/) misc·e·lla·ne·ous (/ˌmɪs.əˈleɪ.ni.əs/) nau·seous (/ˈnɔ.ʃəs/) out·ra·geous (/aʊtˈreɪ.ʤəs/) pit·e·ous (/ˈpɪt.i.əs/) righ·teous (/ˈraɪ.tʃəs/) si·mul·ta·ne·ous (/ˌsaɪ.məlˈteɪ.ni.əs/) vi·tre·ous (/ˈvɪ.tri.əs/) |

am·phib·i·ous (/æmˈfɪb.i.əs/) bo·da·cious (/boʊˈdeɪ.ʃəs/) con·ta·gious (/kənˈteɪ.ʤəs/) du·bi·ous (/ˈdu.bi.əs/) ex·pe·diti·ous (/ˌɛk spɪˈdɪʃ.əs/) fa·ce·tious (/fəˈsi.ʃəs/) gre·gar·i·ous (/grɪˈgɛər.i.əs/) hi·lar·i·ous (/hɪˈlɛr.i.əs/) im·per·vi·ous (/ɪmˈpɜr.vi.əs/) ju·dici·ous (/ʤuˈdɪʃ.əs/) la·bor·i·ous (/ləˈbɔr.i.əs/) my·ster·i·ous (/mɪˈstɪr.i əs/) ne·far·i·ous (/nɪˈfɛr.i.əs/) ob·vi·ous (/ˈɑb.vi.əs/) pro·digi·ous (/prəˈdɪʤ.əs/) re·bell·ious (/rɪˈbɛl.jəs/) su·per·sti·tious (/ˌsu.pərˈstɪ.ʃəs/) te·na·cious (/teˈneɪ.ʃəs/) up·roar·i·ous (/ʌpˈrɔr.i.əs/) vi·car·i·ous (/vaɪˈkɛər.i.əs/) |

“-ia”

This suffix is used to create nouns, either denoting a disease or a condition or quality.

In most words, the I is pronounced individually. In other words, it becomes silent and indicates a change in the pronunciation of the previous consonant. (In a handful of words, I blends with a previous vowel sound that is stressed before the final A.)

For example:

- ac·a·de·mi·a (/ˌæk.əˈdi.mi.ə/)

- bac·ter·i·a (/bæk.ˈtɪər.i.ə/)

- cat·a·to·ni·a (/ˌkæt.əˈtoʊ.ni.ə/)

- de·men·tia (/dɪˈmɛn.ʃə/)

- en·cy·clo·pe·di·a (/ɛnˌsaɪ.kləˈpi.di.ə/)

- fan·ta·sia (/fænˈteɪ.ʒə/)

- hy·po·ther·mi·a (ˌhaɪ.pəˈθɜr.mi.ə/)

- in·som·ni·a (/ɪnˈsɑm.ni.ə/)

- leu·ke·mi·a (/luˈki.mi.ə/)

- mem·or·a·bil·i·a (/ˌmɛm.ər.əˈbɪl.i.ə/)

- no·stal·gia (/nɑˈstæl.ʤə/)

- par·a·noi·a (/ˌpær.əˈnɔɪ.ə/)

- re·ga·li·a (/rɪˈgeɪ.li.ə/)

- su·bur·bi·a (/səˈbɜr.bi.ə/)

- tri·vi·a (/ˈtrɪ.vi.ə/)

- u·to·pi·a (/juˈtoʊ.pi.ə/)

- xen·o·pho·bi·a (/ˌzɛn.əˈfoʊ.bi.ə/)

“-ial”

The suffix “-ial” is used to form adjectives from nouns, meaning “of, characterized by, connected with, or relating to.” Like “-ia,” I is either pronounced individually or else becomes silent and changes the pronunciation of the previous consonant. For example:

- ad·ver·bi·al (/ædˈvɜr.bi.əl/)

- bac·ter·i·al (/bækˈtɪr.i.əl/)

- con·fi·den·tial (/ˌkɑn.fɪˈdɛn.ʃəl/)

- def·e·ren·tial (/ˌdɛf.əˈrɛn.ʃəl/)

- ed·i·tor·i·al (/ˌɛd.ɪˈtɔr.i.əl/)

- fa·mil·i·al (/fəˈmɪl.jəl/)

- gla·cial (/ˈgleɪ.ʃəl/)

- in·flu·en·tial (/ˌɪn.fluˈɛn.ʃəl/)

- ju·di·cial (/ʤuˈdɪʃ.əl/)

- me·mor· i·al (/məˈmɔr.i.əl/)

- o·ffici·al (/əˈfɪʃ.əl/)

- pro·ver·bi·al (/prəˈvɜr.bi.əl/)

- ref·e·ren·tial (/ˌrɛf.əˈrɛn.ʃəl/)

- su·per·fi·cial (/ˌsu.pərˈfɪʃ.əl/)

- terr·i·tor·i·al (/ˌtɛr.ɪˈtɔr.i.əl/)

- ve·stig·i·al (/vɛˈstɪʤ.i.əl/)

“-ic” and “-ical”

These two suffixes form adjectives from the nouns to which they attach. For both, the primary stress is placed on the syllable immediately before “-ic-.” For example:

|

-ic |

-ical |

|---|---|

|

a·tom·ic (/əˈtɑm.ɪk) bur·eau·crat·ic (/ˌbjʊər.əˈkræt.ɪk) cha·ot·ic (/keɪˈɑt.ɪk/) dem·o·crat·ic (/ˌdɛm.əˈkræt.ɪk/) en·er·get·ic (/ˌɛn.ərˈʤɛt.ɪk/) for·mu·la·ic (/ˌfɔr.mjəˈleɪ.ɪk/) ge·net·ic (/ʤəˈnɛt.ɪk/) hyp·not·ic (/hɪpˈnɑt.ɪk/) i·con·ic (/aɪˈkɑn.ɪk/) ki·net·ic (/kəˈnɛt.ɪk/) la·con·ic (/leɪˈkɑn.ɪk/) mag·net·ic (/mægˈnɛt.ɪk/) no·stal·gic (/nəˈstæl.ʤɪk) opp·or·tu·nis·tic (/ˌɑp.ər.tuˈnɪs.tɪk/) pe·ri·od·ic (/ˌpɪər.iˈɑd.ɪk/) re·a·lis·tic (/ˌri.əˈlɪs.tɪk/) sym·pa·thet·ic (/ˌsɪm.pəˈθɛt.ɪk/) ti·tan·ic (taɪˈtæn.ɪk/) ul·tra·son·ic (/ˌʌl.trəsɑn.ɪk/) vol·can·ic (/vɑlˈkæn.ɪk/) |

an·a·tom·i·cal (/ˌæn.əˈtɑm.ɪ.kəl) bi·o·log·i·cal (/ˌbaɪ.əˈlɑʤ.ɪ.kəl/) chron·o·log·i·cal (/ˌkrɑn.əˈlɑʤ.ɪ.kəl/) di·a·bol·i·cal (/ˌdaɪ.əˈbɑl.ɪ.kəl/) e·lec·tri·cal (/ɪˈlɛk.trɪ.kəl/) far·ci·cal (/ˈfɑr.sɪ.kəl/) ge·o·graph·i·cal (/ʤi.əˈgræf.ɪ.kəl/) his·tor·i·cal (/hɪˈstɔr.ɪ.kəl/) in·e·ffec·tu·al (/ˌɪn.ɪˈfɛk.tʃu.əl/) lack·a·dai·si·cal (/ˌlæk.əˈdeɪ.zɪ.kəl/) mu·si·cal (/ˈmju.zɪ.kəl/) nau·ti·cal (/ˈnɔ.tɪ.kəl/) op·ti·cal (/ˈɑp.tɪ.kəl/) par·a·dox·i·cal (/pær.əˈdɑks.ɪ.kəl/) psy·cho·an·a·lyt·i·cal (/ˌsaɪ.koʊ.æn.əˈlɪt.ɪ.kəl/) rhe·tor·i·cal (/rɪˈtɔr.ɪ.kəl/) sy·mmet·ri·cal (/sɪˈmɛt.rɪ.kəl/) ty·ran·ni·cal (/tɪˈræn.ɪ.kəl/) um·bil·i·cal (/ʌmˈbɪl.ɪ.kəl/) ver·ti·cal (/ˈvɜr.tɪ.kəl/) whim·si·cal (/ˈwɪm.zɪ.kəl/) zo·o·log·i·cal (ˌzoʊ.əˈlɑʤ.ɪ.kəl/) |

While this pattern of pronunciation is very reliable, there are a few words (mostly nouns) ending in “-ic” that go against it:

- a·rith·me·tic* (/əˈrɪθ.mə.tɪk/)

- her·e·tic (/ˈhɛr.ɪ.tɪk/)

- lu·na·tic (/ˈlu.nə.tɪk/)

- pol·i·tics (/ˈpɑl.ɪ.tɪks/)

- rhet·o·ric (/ˈrɛt.ə.rɪk/)

(*This pronunciation is used when arithmetic is a noun. As an adjective, it is pronounced a·rith·me·tic [/ˌæ.rɪθˈmɛ.tɪk/].)

“-ify”

This suffix is used to form verbs, most often from existing nouns or adjectives. While the primary stress is placed immediately before “-i-,” the second syllable of the suffix, “-fy,” also receives a secondary stress. For instance:

- a·cid·i·fy (/əˈsɪd.əˌfaɪ/)

- be·at·i·fy (/biˈæt.əˌfaɪ/)

- class·i·fy (/ˈklæs.əˌfaɪ/)

- dig·ni·fy (/ˈdɪg.nəˌfaɪ/)

- e·lec·tri·fy (/ɪˈlɛk.trəˌfaɪ/)

- fal·si·fy (/ˈfɔlsə.faɪ/)

- horr·i·fy (/ˈhɔr.əˌfaɪ/)

- i·den·ti·fy (/aɪˈdɛn.təˌfaɪ/)

- mag·ni·fy (/ˈmægnəˌfaɪ/)

- no·ti·fy (/ˈnoʊ.təˌfaɪ/)

- ob·jec·ti·fy (/əbˈʤɛk.təˌfaɪ/)

- per·son·i·fy (/pərˈsɑn.əˌfaɪ/)

- rat·i·fy (/ˈræt.əˌfaɪ/)

- so·lid·i·fy (/səˈlɪd.əˌfaɪ/)

- tes·ti·fy (/ˈtɛs.təˌfaɪ/)

- ver·i·fy (/ˈvɛr.əˌfaɪ/)

“-ity”

This suffix is the opposite of “-ic(al)”—that is, it is used to create nouns from adjectives. The I is pronounced in an individual syllable, with the word’s primary stress occurring immediately before it. For instance:

- a·bil·i·ty (/əˈbɪl.ɪ.ti/)

- ba·nal·i·ty (/bəˈnæl.ɪ.ti/)

- ce·leb·ri·ty (/səˈlɛb.rɪ.ti/)

- dis·par·i·ty (/dɪˈspær.ɪ.ti/)

- e·qual·i·ty (/əˈkwɑl.ɪ.ti/)

- func·tion·al·i·ty (/ˌfʌŋk.ʃənˈæl.ɪ.tɪ/)

- gen·e·ros·i·ty (/ˌʤɛn.əˈrɑs.ɪ.ti/)

- hu·mid·i·ty (/hjuˈmɪd.ɪ.ti/)

- i·niq·ui·ty (/ɪˈnɪk.wɪ.ti/)

- jo·vi·al·i·ty (/ʤoʊ.vi.ˈæl.ɪ.ti/)

- le·gal·i·ty (/liˈgæl.ɪ.ti/)

- ma·jor·i·ty (/məˈʤoʊr.ɪ.ti/)

- nor·mal·i·ty (/noʊrˈmæl.ɪ.ti/)

- ob·scur·i·ty (/əbˈskʊər.ɪ.ti/)

- prac·ti·cal·i·ty (/præk.tɪˈkæl.ɪ.ti/)

- qual·i·ty (/ˈkwɑl.ɪ.ti/)

- rec·i·proc·i·ty (/ˌrɛs.əˈprɑs.ɪ.ti/)

- scar·ci·ty (/ˈskɛr.sɪ.ti/)

- tech·ni·cal·i·ty (/ˌtɛk.nɪˈkæl.ɪ.ti/)

- u·na·nim·i·ty (/ˌju.nəˈnɪm.ɪ.ti/)

- ve·loc·i·ty (/vəˈlɑs.ɪ.ti/)

“-tion” and “-sion”

These two syllables are used to create nouns, especially from verbs to describe an instance of that action. Depending on the word, the /ʃ/ or /tʃ/ sounds made by “-tion” and the /ʃ/ or /ʒ/ sounds made by “-sion” will be part of the stressed syllable or the final unstressed syllable. For example:

|

-tion |

-sion |

|---|---|

|

au·diti·on (/ɔˈdɪʃ.ən/) bi·sec·tion (/baɪˈsɛk.ʃən/) can·ce·lla·tion (/ˌkæn.sɪˈleɪ.ʃən/) di·screti· on (/dɪˈskrɛʃ.ən/) ex·haus·tion (/ɪgˈzɔs.tʃən/) flo·ta·tion (/floʊˈteɪ.ʃən/) grad·u·a·tion (/ˌgræʤ.uˈeɪ.ʃən/) hos·pi·tal·i·za·tion (/ˌhɑs.pɪ.təl.ɪˈzeɪʃ.ən/) ig·ni·tion (/ɪgˈnɪʃ.ən/) jur·is·dic·tion (/ˌʤʊər.ɪsˈdɪk.ʃən/) lo·co·mo·tion (/ˌloʊ.kəˈmoʊ,ʃən/) mod·i·fi·ca·tion (/ˌmɑd.ə.fɪˈkeɪ.ʃən/) nom·i·na·tion (/ˌnɑm.əˈneɪ.ʃən/) ob·struc·tion (/əbˈstrʌk.ʃən/) pros·e·cu·tion (/ˌprɑs.ɪˈkyu.ʃən/) re·a·li·za·tion (/ˌri.ə.ləˈzeɪ.ʃən/) se·cre·tion (/sɪˈkri.ʃən/) tra·diti·on (/trəˈdɪʃ.ən/) u·ni·fi·ca·tion (/ˌju.nə.fɪˈkeɪ.ʃən/) vi·bra·tion (/vaɪˈbreɪ.ʃən/) |

a·bra·sion (/əˈbreɪ.ʒən) a·ver·sion (/əˈvɜr.ʒən/) co·llisi·on (/kəˈlɪʒ.ən/) com·pul·sion (/kəmˈpʌl.ʃən/) di·ffu·sion (/dɪˈfju.ʒən/) di·men·sion (/dɪˈmɛn.ʃən/) e·ro·sion (/ɪˈroʊ.ʒən/) fu·sion (/ˈfju.ʒən/) i·llu·sion (/ɪˈlu.ʒən/) in·va·sion (/ɪnˈveɪ.ʒən/) man·sion (/ˈmæn.ʃən/) ob·sessi·on (/əbˈsɛʃ.ən/) o·cca·sion (/əˈkeɪ.ʒən/) per·cussi·on (/pərˈkʌʃ.ən/) pro·pul·sion (/prəˈpʌl.ʃən) re·missi·on (/rɪˈmɪʃ.ən/) sub·ver·sion (/səbˈvɜr.ʒən/) su·spen·sion (/səˈspɛn.ʃən/) trans·fu·sion (/trænsˈfju.ʒən/) ver·sion (/ˈvɜr.ʒən/) |

The word television is an exception to this rule, and in most dialects it has the primary stress placed on the first syllable: /ˈtɛl.əˌvɪʒ.ən/.

Stress applied two syllables before the suffix

“-ate”

This suffix is most often used to create verbs, but it can also form adjectives and nouns. In words with three or more syllables, the primary stress is placed two syllables before the suffix. For example:

- ac·cen·tu·ate (/ækˈsɛn.tʃuˌeɪt/))

- bar·bit·ur·ate (/bɑrˈbɪtʃ.ər.ɪt/)

- co·llab·o·rate (/kəˈlæb.əˌreɪt/)

- diff·e·ren·ti·ate (/ˌdɪf.əˈrɛn.ʃiˌeɪt/)

- e·nu.me·rate (/ɪˈnu.məˌreɪt/)

- fa·cil·i·tate (/fəˈsɪl.ɪˌteɪt/)

- ge·stic·u·late (/ʤɛˈstɪk.jəˌleɪt/)

- hu·mil·i·ate (/hjuˈmɪl.iˌeɪt/)

- in·ad·e·quate (/ɪnˈæd.ɪ.kwɪt/)

- le·git·i·mate (/lɪˈʤɪt.əˌmɪt/)

- ma·tric·u·late (/məˈtrɪk.jəˌleɪt/)

- ne·cess·i·tate (/nəˈsɛs.ɪˌteɪt/)

- o·blit·e·rate (/əˈblɪt.əˌreɪt/)

- par·tic·i·pate (/pɑrˈtɪs.ɪ.ɪt/)

- re·frig·er·ate (/rɪˈfrɪʤ.əˌreɪt/)

- stip·u·late (/ˈstɪp.jəˌleɪt/)

- tri·an·gu·late (/traɪˈæŋ.gjə.leɪt/)

- un·for·tu·nate (/ʌnˈfɔr.tʃə.nɪt/)

- ver·te·brate (/ˈvɜr.tə.brɪt/)

“-cy”

This suffix attaches to adjectives or nouns to form nouns referring to “state, condition, or quality,” or “rank or office.” For example:

- a·dja·cen·cy (/əˈʤeɪ.sən.si/)

- a·gen·cy (/ˈeɪ.ʤən.si/)

- bank·rupt·cy (/ˈbæŋk.rʌpt.si/)

- com·pla·cen·cy (/kəmˈpleɪ.sən.si/)

- de·moc·ra·cy (/dɪˈmɑk.rə.si/)

- ex·pec·tan·cy (/ɪkˈspɛk.tən.si/)

- flam·boy·an·cy (/flæmˈbɔɪ.ən.si/)

- fre·quen·cy (/ˈfri.kwən.si/)

- in·sur·gen·cy (/ɪnˈsɜr.ʤən.si/)

- in·fan·cy (/ ˈɪnfən.si/)

- lieu·ten·an·cy (/luˈtɛn.ən.si/)

- ma·lig·nan·cy (/məˈlɪg.nən.si/)

- pro·fici·en·cy (/prəˈfɪʃ.ən.si/)

- re·dun·dan·cy (/rɪˈdʌn.dən.si/)

- su·prem·a·cy (/səˈprɛm.ə.si/)

- trans·par·en·cy (/trænsˈpɛər.ən.si/)

- va·can·cy (/ˈveɪ.kən.si/)

Unlike some of the other suffixes we’ve looked at so far, this one has a number of exceptions. For these, the primary stress is placed three syllables before the suffix:

- ac·cur·a·cy (/ˈæk.jər.ə.si/)

- can·di·da·cy (/ˈkæn.dɪ.də.si/)

- com·pe·ten·cy (/ˈkɑm.pɪ.tən.si/)

- del·i·ca·cy (/ˈdɛl.ɪ.kə.si/)

- ex·trav·a·gan·cy (/ɪkˈstræv.ə.gən.si/)

- im·me·di·a·cy (/ɪˈmi.di.ə.si/)

- in·ti·ma·cy (/ˈɪn.tɪ.mə.sɪ/)

- lit·er·a·cy (/ˈlɪt.ər.ə.sɪ/)

- le·git·i·ma·cy (/lɪˈʤɪt.ə.mə.si/)

- occ·u·pan·cy (/ˈɑk.jə.pən.si/)

- pres·i·den·cy (/ˈprɛz.ɪ.dən.si/)

- rel·e·van·cy (/ˈrɛl.ɪ.vən.si/)

- surr·o·ga·cy (/ˈsɜr.ə.gə.si/)

Unfortunately, there are no patterns in these words to let us know that their primary stress will be in a different place; we just have to memorize them.

“-phy”

This ending is actually a part of other suffixes, most often “-graphy,” but also “-trophy” and “-sophy.” The primary stress in the word will appear immediately before the “-gra-,” “-tro-,” and “-so-” parts of the words. For example:

- a·tro·phy (/ˈæ.trə.fi/)

- bib·li·og·ra·phy (/ˌbɪb.liˈɑg.rə.fi/)

- cal·lig·ra·phy (/kəˈlɪg.rə.fi/)

- dis·cog·ra·phy (/dɪsˈkɑɡ.rə.fi/)

- eth·nog·ra·phy (/ɛθˈnɑg.rə.fi/)

- fil·mog·ra·phy (/fɪlˈmɑɡ.rə.fi/)

- ge·og·ra·phy (/ʤiˈɑɡ.rə.fi/)

- i·co·nog·ra·phy (/ˌaɪ.kəˈnɑg.rə.fi/)

- or·thog·ra·phy (/ɔrˈθɑg.rə.fi/)

- phi·los·o·phy (/fɪˈlɑs.ə.fi/)

- pho·tog·ra·phy (/fəˈtɑg.rə.fi/)

- ra·di·og·ra·phy (/ˌreɪ.dɪˈɑɡ.rə.fɪ/)

- so·nog·ra·phy (/səˈnɑg.rə.fi/)

- the·os·o·phy (/θɪˈɑs.ə.fi/)

- ty·pog·ra·phy (/taɪˈpɑg.rə.fi/)

Suffixes that don’t affect word stress

While many suffixes dictate which syllable is stressed in a word, there are others that usually do not affect the stress of the base word at all. Let’s look at some examples of these (just note that this isn’t an exhaustive list):

|

“-age” |

“-ish”* |