It is important to pay attention to stress and intonation if we want to learn a language properly. In this article, we are going to look at these two concepts differently and then move onto the discussion about difference between Stress and Intonation.

What is Stress?

Stress is the emphasis given to a specific syllable or word in speech, usually through a combination of relatively greater loudness, higher pitch, and longer duration. Syllable is a part of a word that is pronounced with one uninterrupted sound. It is also important to remember that we stress the vowel sound of the word, not the consonant sound.

The stress placed on syllables in a word is called lexical stress or word stress. Stress placed on some words within a sentence is called sentence stress or prosodic stress.

Word Stress

Take the word Garden for example. It has two syllables: ‘Gar’ and ‘den’. The stress is placed on ‘Gar’. Similarly, given below are some examples. The stressed syllables are written in capital letters.

- Water: WAter

- Station : STAtion

- People: PEOple

Sentence Stress

Sentence stress is the way of highlighting the important words in a sentence. Unlike in word stress, you can choose where you can place the stress. Selecting which words to stress depends on the meaning and context. However, if the stress is not used correctly, the sentence might be misinterpreted.

Examples:

- CLOSE the DOOR.

- WHAT did HE SAY to you in the GARDEN?

- Have you SEEN the NEW FILM of TOM CRUISE?

WHERE are you GOING?

What is Intonation?

Intonation is the variation of our pitch, in the spoken language. Intonation indicates our emotions and attitudes, determine the difference between statements and questions and sometimes highlight the importance of the verbal message we’re giving out. In English, there are 3 basic intonation patterns: Falling Intonation, Rising Intonation, and Partial/Fall-rise Intonation.

Falling intonation

Falling intonation describes how the voice falls on the final stressed syllable of a phrase or a group of words. It is used in expressing a complete,definite thought, and asking wh-questions.

- “Where is the nearest Police Station?”

- “She got a new dog”

Rising intonation

Rising intonation describes how the voice rises at the end of a sentence. This is common in yes-no questions or in expressing surprise.

- “Your dog can speak?”

- “Are you hungry?”

Partial Intonation

Partial Intonation describes how voice rises then falls. People use this intonation when they are not sure, or they have more to add to a sentence. We also use this intonation pattern to ask questions, as it sounds more polite.

- “Would you like some coffee?”

- “I want to go to France, but…”

You trust her.

Definition

Intonation is the variation of our pitch, in the spoken language.

Stress is the emphasis given to a specific syllable or word in speech

Focus

Stress pays particular attention to syllables and words.

Intonation pays attention to pitch.

Emotions/Attitudes

Intonation helps you to detect the emotions and attitudes of the speaker.

Stress does not enable us to understand the attitudes of the speaker.

About the Author: Hasa

Hasa has a BA degree in English, French and Translation studies. She is currently reading for a Masters degree in English. Her areas of interests include literature, language, linguistics and also food.

You May Also Like These

If you are to speak a language clearly, paying attention to the difference between stress and intonation is essential. Stress and intonation are two terms that come in linguistics and play a vital role in communication as it allows us to get through to the others by being comprehensive. As we articulate syllables, the energy used or else the force that we used is considered stress. Intonation, on the other hand, refers to the manner in which we speak, to be more specific, it concentrates on the variation of pitch when speaking. This article attempts to provide a basic understanding of the two terms enabling the reader to grasp the differences between the two terms.

What is Stress?

Stress refers to the emphasis laid on specific syllables of a word or a specific word in a sentence. This highlights that there are two types as word stress and sentence stress. Word stress is when we pronounce a particular syllable with more emphasis or force in comparison to the other syllables. For example, let us take the word ‘garden’. As we pronounce it, the stress is on ‘gar’ , and the rest are unstressed. Sentence stress, on the other hand, refers to a particular word that is given prominence in comparison to the rest of the words. For example, when we say:

It was awesome.

The main stress is laid on the word ‘awesome‘. This highlights that the stress can be used to emphasize a particular fact in a sentence or else to bring out the meaning.

It was awesome.

What is Intonation?

As we express our thoughts, the way in which our voice changes as the pitch rises and falls allows the others to understand our stance of various things. This is referred to as intonation. Intonation consists of tone units and a pitch range. Tone units refer to the phrases that we divide as we speak. In each tone unit, there is a combination of rise and fall of the pitch. Pitch range, on the other hand, focuses specifically on the highs and lows of the pitch. This allows us to understand how a person feels about a certain thing through the manner in which he expresses it. For example, let us take a very ordinary occurrence.

You trust him.

You trust him.

With the change of the pitch, this can express different meanings such as disbelief, satisfaction, acknowledgement, etc. So, intonation assists in effective communication through the rise and fall of the voice. If people spoke in the same pitch without any changes , it would certainly be very difficult to grasp the exact meaning.

You trust him.

What is the difference between Stress and Intonation?

• Stress refers to the emphasis laid on specific syllables or words of a sentence.

• Intonation refers to the variation of the pitch as an individual speaks.

• The difference between the two is that while stress pays particular attention to syllables and words, intonation can create an entire variation of the meaning through the usage of stress.

Images Courtesy:

- Party by Nicor (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Man by Halfhaggis (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Correct intonation and stress are the key to speaking English fluently with good pronunciation. Intonation and stress refer to the music of the English language. Words that are stressed are key to understanding and using the correct intonation brings out the meaning.

Introduction to Intonation and Stress Exercise

Say this sentence aloud and count how many seconds it takes.

The beautiful mountain appeared transfixed in the distance.

Time required? Probably about five seconds. Now, try speaking this sentence aloud

He can come on Sundays as long as he doesn’t have to do any homework in the evening.

Time required? Probably about five seconds.

Wait a minute—the first sentence is much shorter than the second sentence!

The beautiful Mountain appeared transfixed in the distance. (14 syllables)

He can come on Sundays as long as he doesn’t have to do any homework in the evening. (22 syllables)

Even though the second sentence is approximately 30 percent longer than the first, the sentences take the same time to speak. This is because there are five stressed words in each sentence. From this example, you can see that you needn’t worry about pronouncing every word clearly to be understood (we native speakers certainly don’t). You should, however, concentrate on pronouncing the stressed words clearly.

This simple exercise makes a very important point about how we speak and use English. Namely, English is considered a stressed language while many other languages are considered syllabic. What does that mean? It means that, in English, we give stress to certain words while other words are quickly spoken (some students say eaten!). In other languages, such as French or Italian, each syllable receives equal importance (there is stress, but each syllable has its own length).

Many speakers of syllabic languages don’t understand why we quickly speak, or swallow, a number of words in a sentence. In syllabic languages, each syllable has equal importance, and therefore equal time is needed. English however, spends more time on specific stressed words while quickly gliding over the other, less important, words.

Simple Exercise to Help With Understanding

The following exercise can be used by students and teachers to further help with pronunciation by focusing on the stressing content words rather than function words in the exercise below.

Let’s look at a simple example: The modal verb «can.» When we use the positive form of «can» we quickly glide over the can and it is hardly pronounced.

They can come on Friday. (stressed words in italics)

On the other hand, when we use the negative form «can’t» we tend to stress the fact that it is the negative form by also stressing «can’t».

They can’t come on Friday. (stressed words in italics)

As you can see from the above example the sentence, «They can’t come on Friday» is longer than «They can come on Friday» because both the modal «can’t» and the verb «come» are stressed.

Understanding Which Words to Stress

To begin, you need to understand which words we generally stress and which we do not stress. Stress words are considered content words such as:

- Nouns (e.g., kitchen, Peter)

- (Most) main verbs (e.g., visit, construct)

- Adjectives (e.g., beautiful, interesting)

- Adverbs (e.g., often, carefully)

- Negatives including negative helping verbs, and words with «no» such as «nothing,» «nowhere,» etc.

- Words expressing quantities (e.g., a lot of, a few, many, etc.)

Non-stressed words are considered function words such as:

- Determiners (e.g., the, a, some, a few)

- Auxiliary verbs (e.g., don’t, am, can, were)

- Prepositions (e.g., before, next to, opposite)

- Conjunctions (e.g., but, while, as)

- Pronouns (e.g., they, she, us)

- Verbs «have» and «be» even when used as main verbs

Practice Quiz

Test your knowledge by identifying which words are content words and should be stressed in the following sentences:

- They’ve been learning English for two months.

- My friends have nothing to do this weekend.

- I would have visited in April if I had known Peter was in town.

- Natalie will have been studying for four hours by six o’clock.

- The boys and I will spend the weekend next to the lake fishing for trout.

- Jennifer and Alice had finished the report before it was due last week.

Answers:

Words in italics are stressed content words while unstressed function words are in lower case.

- They’ve been learning English for two months.

- My friends have nothing to do this weekend.

- I would have visited in April if i had known Peter was in town.

- Natalie will have been studying for fours hours by six o’clock.

- The boys and i will spend the weekend next to the lake fishing for trout.

- Jennifer and Alice had finished the report before it was due last week.

Continue Practicing

Speak to your native English speaking friends and listen to how we concentrate on the stressed words rather than giving importance to each syllable. As you begin to listen and use stressed words, you will discover words you thought you didn’t understand are really not crucial for understanding the sense or making yourself understood. Stressed words are the key to excellent pronunciation and understanding of English.

After students have learned basic consonant and vowel sounds, they should move on to learning to differentiate between individual sounds by using minimal pairs. Once they are comfortable with individual words, they should move on to intonation and stress exercises such as sentence markup. Finally, students can take the next step by choosing a focus word to help further improve their pronunciation.

You’ve probably noticed that I love talking about stress and intonation. In my opinion, speaking with clear stress and expressive intonation will help native speakers understand you better.

You’ll communicate what you really mean, sound more natural, and feel more confident as a result.

Even if you recognize that stress and intonation are important, you may feel confused about why they matter, what they communicate, or how to get started changing the way you use your voice.

This is totally normal!

In this article and video, I want to clarify five myths about intonation that I often receive questions about.

This video will be more of an exploration of how stress and intonation relate to communication, rather than a step-by-step tutorial.

If you want more guidance on how to actually use stress and intonation, be sure to check out all the links to my related articles and videos.

Let’s discuss these five intonation myths.

Myth #1: Stress and intonation are the same thing.

You’ve probably heard people talk about stress and intonation as if they were the same thing.

However, it’s better to think of them as working together.

Stress and intonation are key elements of prosody, or the characteristics of speech beyond words that affect how information is communicated and understood.

Prosody includes:

- pitch

- stress

- intonation

- rhythm

- pace, or speaking speed, and

- loudness.

All of these elements work together to create meaning.

When we stress content words, or emphasize the important words of a sentence by making one syllable longer, louder and higher in pitch, we create the rhythm and melody of English.

In normal, neutral sentences, this rhythm and melody should be predictable and regular.

This is what we most often call sentence stress.

(I talk about this in depth in my video on sentence stress in American English.)

When we refer to stress, we’re talking about how we emphasize certain syllables of certain words, which includes changes in pitch, volume, syllable length, and vowel clarity.

Stress plays a role in intonation because native speakers are expecting to hear you stress sentences in a particular way.

Any changes in stress may signal a completely different meaning.

When we change stress through inflection, by emphasizing one word more than the others, by making its key syllable longer, louder, and higher in pitch, we can completely change the meaning.

Beyond changing which word receives the most stress, we can express different emotions, attitudes, feelings, and moods through rises and falls in pitch, by speaking with more or less pitch variation, or speaking with a wider or more limited pitch range.

We also use intonation for different conversational purposes, such as:

- checking and confirming information

- making observations

- asking for information

- indicating we’re still speaking

- hesitating

- giving tentative suggestions, and

- expressing uncertainty.

Our pitch can rise or fall steeply or sharply. It can be a gradual climb or drop, or it can change through steps or a glide.

These changes in pitch can start on just about any word in the sentence.

Your intonation will change based on what you’re trying to express.

To summarize, stress refers to how we emphasize key syllables of key words.

Intonation refers to how we communicate additional meaning through rises and falls in pitch.

Myth #2: Intonation is just the ups and downs of speech.

Related to the confusion between stress and intonation, some people think that intonation is just the ups and downs, the rises and falls of your speech.

While you’ll definitely sound more like a native speaker if you increase the variety of pitch you use when speaking, it doesn’t stop at the ups and the downs.

If you’re mechanical in changing your pitch, just practicing steps up and down, you’ll probably still sound unnatural or robotic.

English rhythm and melody are regular, but not THAT regular.

After all, stress includes lengthened syllables, and rushing through words that just don’t matter.

We use volume and speed changes to communicate additional meaning.

We might stress a word for contrast, clarity, or emphasis.

We might include a steep rise or fall in pitch in order to sound excited, curious, doubtful or bored.

We use glides or pitch slides up or down on lengthened syllables just as much as steps, and you need to learn how to use them too.

Be sure to check out my video on pitch exercises in order to practice steps and glides and see the different ways we change our pitch in English.

Myth #3: It’s not possible for me to improve my intonation because I’m not fluent or I’m too old.

Even if you’re not yet fluent in English, you can start working on your intonation.

First of all, you want to do your best to master word and sentence stress so that your overall intonation makes sense.

You need to be consistently creating English rhythm so that people can hear when you stress a different word than expected, or when you change your pitch to express a different attitude.

Please remember that it takes practice to stress your words consistently.

At first, you’ll have to work at it as you continue to internalize English rhythm and stress patterns.

You might also have to train your ear to hear these variations in stress, pitch, and intonation.

But eventually it will click, and you’ll start doing it automatically. Trust the process.

As you get started with intonation, focus on the most common conversational uses of rising and falling intonation.

Make sure you’re asking information questions and saying normal sentences with falling intonation.

Be sure to ask yes/no questions with rising intonation.

From there, you can start practicing different emotions and attitudes.

Check out my intonation exercises video for some fun practice.

Once you’re more fluent and more comfortable speaking at length, then you can work on intonation in longer sentences and breaking your ideas into thought groups.

The sooner you can get started including intonation practice in your everyday routine, the better results you’ll have.

It’s not that intonation is too advanced for you, but you may need to deepen your social, emotional, and cultural sensitivity to the message that you’re conveying through your intonation.

The more sensitive you are, the more you’ll appreciate the importance of intonation.

The fact that you’re concerned about intonation shows that you’re partway there, so trust the process and keep going.

Myth #4: Intonation doesn’t matter.

You know my answer to this one. Yes, it does!

The way we emphasize a certain word or a pitch rise or fall can completely change the meaning.

If people ask you “What did you mean by that?”, they probably weren’t able to interpret your tone of voice.

I often hear this kind of comment from people who think what they have to say is more important than how it’s received by others.

The truth is, good communication is often more subtle than what you’re saying with your words, and whether they’re understood.

Your voice and the way you express yourself is influenced by a number of factors:

- cultural background

- gender

- education level

- your profession

- how much authority you’re used to having when you’re speaking

- socioeconomic level

- your manners or politeness,

- even your personality.

Get curious about why you speak the way you do in both your native language and in English.

Then you can adjust as necessary.

Quite honestly, I’ve run into communication challenges when speaking Spanish for this same reason!

I’ve spoken with too much authority and directness for the situation, and I’ve also tried to be too polite and ended up sounding unclear.

Adjusting to speaking a different language in a culture you weren’t raised in takes time, patience, and practice.

Because we use intonation to communicate different emotions and attitudes, to show compassion, interest, and connection, to be more direct, or to soften our language in order to sound more polite, it absolutely does matter.

Of course, you’ll find yourself in situations where your intonation doesn’t matter as much, because people understand that you’re a non-native speaker, and they’re more open-minded and patient.

But you’ll also have many interactions where intonation will help you communicate better, such as when you’re giving presentations, leading meetings, or in a job interview.

For many people, intonation helps them go from speaking fluently to actually sounding fluent.

Your speech will have better flow, and you’ll sound more culturally sensitive.

Rather than deciding it doesn’t matter, think about how intonation can help you improve how you sound. Then start experimenting!

Myth #5: We use intonation in my language so I don’t need to learn it.

If intonation is important in your language, then you’re lucky!

You’ll be able to relate what you learn about American intonation to what you already know about your own language.

After all, there are some characteristics about how we express emotions through intonation that tend to stay the same across languages.

However, once again, I would encourage you to get more curious about intonation.

We often express ourself in our native language without thinking about our tone of voice and what it means.

It’s unconscious.

When it comes to the most common intonation patterns in your language, you may be transferring these patterns directly into English, even though English uses intonation differently.

Your native language might use more pitch variation, or less.

You might use more rises and falls mid-sentence, or they might be used differently.

You might use different intonation patterns when asking a question, or when finalizing a statement.

In fact, intonation patterns vary between different varieties of English and even regional dialects.

If you’re speaking with Australian intonation in the United States, it might sound more tentative. If you’re speaking with British intonation, you might sound more serious or matter of fact.

The more curious you get about your intonation, the more you’ll understand how you sound when speaking English.

That will give you more control over how you use your voice.

Even by recording and editing my own YouTube videos, I’ve learned a lot about how I use intonation and prosody!

We can always learn more about communicating more effectively.

Bonus Myth: Intonation is only pronounced one way.

Have you noticed that people pronounce the word “intonation” differently?

I’ve always pronounced the word “intonation” following the typical pattern of words that end in -tion: /ˌɪntəˈneɪʃən/

In fact, this is the pronunciation you see when searching Google for the word “intonation.”

However, I started noticing that other accent and language coaches say the word “intonation” with a long “o” on the second syllable: /ˌɪntoʊˈneɪʃən/

Although it sounds wrong to me, it turns out that /ˌɪntoʊˈneɪʃən/ is another accepted pronunciation of the word.

So whether you hear people say /ˌɪntəˈneɪʃən/ or /ˌɪntoʊˈneɪʃən/, we’re talking about the same thing.

Your Turn

Now that we’ve discussed five myths about intonation, I’d love to hear from you! What else confuses you about stress, intonation, and prosody? What would you like me to clarify in a future video?

Leave a comment and let me know!

For more on why intonation matters, check out these videos:

- Pitch and Intonation When Speaking – Intonation For Statements, Questions, and Thought Groups

- Change Your Meaning with Your Voice – Intonation, Inflection, and Tone of Voice

- Intonation for Clear Communication – Why Intonation is So Important in American English

Ready to work on your intonation? Consider joining the Intonation Clinic, where you’ll learn how to change your pitch to express your meaning through your tone of voice.

-

Word stress, its acoustic

nature. -

The

linguistic function of a word stress. -

Degree

and position of a word stress.

-1-

The

sequence of syllables in the word is not pronounced identically. The

syllable or syllables which are pronounced with more prominence than

the other syllables of the word are said to be stressed or accented.

The correlation of varying prominences of syllables in a word is

understood as the accentual structure of the word.

According

to A.C. Gimson, the effect of prominence is achieved by any or all of

four factors: force, tone, length and vowel colour. The dynamic

stress implies greater force with which the syllable is pronounced.

In other words in the articulation of the stressed syllable greater

muscular energy is produced by the speaker. The European languages

such as English, German, French, Russian are believed to possess

predominantly dynamic word stress. In Scandinavian languages the word

stress is considered to be both dynamic and musical (e.g. in Swedish,

the word komma

(comma) is distinguished from the word komma

(come) by a difference in tones). The musical (tonic) word stress is

observed in Chinese, Japanese. It is effected by the variations of

the voice pitch in relation to neighbouring syllables. In Chinese the

sound sequence “chu” pronounced with the level tone means “pig”,

with the rising tone “bamboo”, and with the falling tone “to

live”.

It is fair

to mention that there is a terminological confusion in discussing the

nature of stress. According to D. Crystal, the terms “heaviness,

intensity, amplitude, prominence, emphasis, accent, stress” tend to

be used synonymously by most writers. The discrepancy in terminology

is largely due to the fact that there are 2 major views depending on

whether the productive or receptive aspects of stress are discussed.

The main

drawback with any theory of stress based on production of speech is

that it only gives a partial explanation of the phenomenon but does

not analyze it on the perceptive level.

Instrumental

investigations study the physical nature of word stress. On the

acoustic level the counterpart of force is the intensity of the

vibrations of the vocal cords of the speaker which is perceived by

the listener as loudness. Thus the greater energy with which the

speaker articulates the stressed syllable in the word is associated

by the listener with greater loudness. The acoustic counterparts of

voice pitch and length are frequency and duration respectively. The

nature of word stress in Russian seems to differ from that in

English. The quantitative component plays a greater role in Russian

accentual structure than in English word accent. In the Russian

language of full formation and full length in unstressed positions,

they are always reduced. Therefore the vowels of full length are

unmistakably perceived as stressed. In English the quantitative

component of word stress is not of primary importance because of the

non-reduced vowels in the unstressed syllables which sometimes occur

in English words (e.g. “transport”, “architect”).

-2-

In discussing accentual

structure of English words we should turn now to the functional

aspect of word stress. In language the word stress performs 3

functions:

-

constitutive– word

stress constitutes a word, it organizes the syllables of a word into

a language unit. A word does not exist without the word stress. Thus

the function is constitutive – sound continuum becomes a phrase

when it is divided into units organized by word stress into words. -

Word

stress enables a person to identify a succession of syllables as a

definite accentual pattern of a word. This function is known as

identificatory (or

recognitive). -

Word

stress alone is capable of differentiating the meaning of words or

their forms, thus performing its distinctive

function. The accentual patterns of

words or the degrees of word stress and their positions form

oppositions (“/import – im /port”, “/present – pre

/sent”).

-3-

There are

actually as many degrees of word stress in a word as there are

syllables. The British linguists usually distinguish three degrees of

stress in the word. The primary stress is the strongest (e.g.

exami/nation), the secondary stress is the second strongest one (e.g.

ex,ami/nation). All the other degrees are termed “weak stress”.

Unstressed syllables are supposed to have weak stress. The American

scholars, B. Bloch and J. Trager, find 4 contrastive degrees

of word stress: locid, reduced locid, medial and weak.

In

Germanic languages the word stress originally fell on the initial

syllable or the second syllable, the root syllable in the English

words with prefixes. This tendency was called recessive. Most English

words of Anglo-Saxon origin as well as the French borrowings are

subjected to this recessive tendency.

Languages

are also differentiated according to the placement of word stress.

The traditional classification of languages concerning the place of

stress in a word is into those with a

fixed stress and a free stress. In

languages with a fixed stress the occurrence of the word stress is

limited to a particular syllable in a multisyllabic word. For

example, in French the stress falls on the last syllable of the word

(if pronounced in isolation), in Finnish and Czech it is fixed on the

first syllable.

Some

borrowed words retain their stress.

In languages with a free

stress its place is not confined to a specific position in the word.

The free placement of stress is exemplified in the English and

Russian languages

(e.g. E. appetite – begin –

examination

R.

озеро – погода

– молоко)

The word

stress in English as well as in Russian is not only free but it may

also be shifting performing semantic function of differentiating

lexical units, parts of speech, grammatical forms. It is worth noting

that in English word stress is used as a means of word-building (e.g.

/contrast – con/trast, /music – mu /sician).

Questions:

-

What

features characterize word accent? -

Identify

the functions of word stress. -

What

are the types of word stress? -

Do AmE and

BE have any differences in the system of word stress? Give your

examples.

Lecture 8. Intonation

-

Intonation.

-

The

linguistic function of intonation. -

The

implications of a terminal tone. -

Rhythm.

-1-

Intonation is a language

universal. There are no languages which are spoken as a monotone,

i.e. without any change of prosodic parametres. On perceptional level

intonation is a complex, a whole, formed by significant variations of

pitch, loudness and tempo closely related. Some linguists regard

speech timber as the fourth component of intonation. Though it

certainly conveys some shades of attitudinal or emotional meaning

there’s no reason to consider it alongside with the 3

prosodic components of intonation (pitch, loudness and tempo).

Nowadays the term “prosody” substitutes the term “intonation”.

On the acoustic level pitch

correlates with the fundamental frequency of the vibrations of the

vocal cords; loudness correlates with the amplitude of vibrations;

tempo is a correlate of time during which a speech unit lasts.

The auditory level is very

important for teachers of foreign languages. Each syllable of the

speech chain has a special pitch colouring. Some of the syllables

have significant moves of tone up and down. Each syllable bears a

definite amount of loudness. Pitch movements are inseparably

connected with loudness. Together with the tempo of speech they form

an intonation pattern which is the basic unit of intonation.

An intonation pattern contains

one nucleus and may contain other stressed or unstressed syllables

normally preceding or following the nucleus. The boundaries of an

intonation pattern may be marked by stops of phonation, that is

temporal pauses.

Intonation patterns serve to

actualize syntagms in oral speech. The syntagm

is a group of words which are semantically and syntactically

complete. In phonetics they are called intonation

groups. The

intonation group is a stretch of speech which may have the length of

the whole phrase. But the phrase often contains more than one

intonation group. The number of them depends on the length of phrase

and the degree of semantic impotence or emphasis given to various

parts of it. The position of intonation groups may affect the

meaning.

-2-

The communicative

function of

intonation is realized in various ways which can be grouped under

five – six general headings:

-

to

structure the intonation content of a textual unit. So as to show

which information is new or can not be taken for granted, as against

information which the listener is assumed to possess or to be able

to acquire from the context, that is given information; -

to

determine the speech function of a phrase, to indicate whether it is

intended as a statement, question, etc; -

to

convey connotational meanings of attitude, such as surprise, etc. In

the written form we are given only the lexics and the grammar; -

to

structure a text. Intonation is an organizing mechanism. It divides

texts into smaller parts and on the other hand it integrates them

forming a complete text; -

to

differentiate the meaning of textual units of the same phonetic

structure and the same lexical composition (distinctive or

phonological function); -

to

characterize a particular style or variety of oral speech which may

be called a stylistic function.

-3-

Classification of intonation

patterns:

Different combinations of

pitch sections (pre-heads, heads and nuclei) may result in more than

one hundred pitch-and-stress patterns. But it is not necessary to

deal with all of them, because some patterns occur very rarely. So,

attention must be concentrated on the commonest ones:

-

The Low (Medium) Fall

pitch-and-stress group -

The

High Fall group -

Rise

Fall group -

The

Low Rise group -

The

High Rise group -

The

Fall Rise group -

The

Rise-Fall-Rise group -

The

Mid-level group

No intonation pattern is used

exclusively with this or that sentence type. Some sentences are more

likely to be said with one intonation pattern than with any other. So

we can speak about “common intonation” for a particular type of

sentence.

-

Statements are most widely

used with the Low Fall preceded by the Falling or the High level

Head. They are final, complete and definite. -

Commands,

with the Low Fall are very powerful, intense, serious and strong. -

Exclamations

are very common with the High Fall.

-4-

We cannot fully describe

English intonation without reference to speech rhythm. Rhythm

seems to be a kind of framework of speech organization. Some

linguists consider it to be one of the components of intonation.

Rhythm is understood as

periodicity in time and space. We find it everywhere in life. Rhythm

as a linguistic notion is realized in lexical, syntactical and

prosodic means and mostly in their combinations.

In speech,

the type of rhythm depends on the language. Linguists divide

languages into two groups:

-

syllable-timed(French, Spanish);

-

stress-timed(English, German, Russian).

In a

syllable-timed language the speaker gives an approximately equal

amount of time to each syllable, whether the syllable is stressed or

unstressed.

In a

stress-timed language the rhythm is based on a larger unit, than

syllable. Though the amount of time given on each syllable varies

considerably, the total time of uttering each rhythmic unit is

practically unchanged. The stressed syllables of a rhythmic unit form

peaks of prominence. They tend to be pronounced at regular intervals

no matter how many unstressed syllables are located between every 2

stressed ones. Thus the distribution of time within the rhythmic unit

is unequal.

Speech

rhythm is traditionally defined as recurrence of stressed syllables

at more or less equal intervals of time in a speech continuum.

Questions:

-

Name

the basic components of intonation. -

What

is the connection between pitch and tempo? -

What

for do we need different nuclear tones? -

Which

nuclei are the commonest?

Lecture

9. Territorial varieties of English pronunciation

-

Varieties

of language. -

English

variants.

-1-

The

varieties of the language are conditioned by language communities

ranging from small groups to nations. National

language is the language of a nation,

the standard of its form, the language of a nation’s literature.

The literary spoken form has its national

pronunciation standard. A “standard”

may be defined as a socially accepted variety of a language

established by a codified norm of correctness. It is generally

accepted that for the “English English” it is “Received

Pronunciation” or RP; for the “American English” – “General

American pronunciation”; for the Australian English – “Educated

Australian”.

Though

every national variant of English has considerable differences in

pronunciation, lexics and grammar, they all have much in common which

gives us ground to speak of one and the same language – the English

language.

Every

national variety of the language falls into territorial

or regional dialects. Dialects are

distinguished from each other by differences in pronunciation,

grammar and vocabulary. When we refer to varieties in pronunciation

only, we use the word “accent”.

The social

differentiation of language is closely connected with the social

differentiation of society. Every language community, ranging from a

small group to a nation has its own social

dialect, and consequently, its own

social accent.

The

“language situation” may be spoken about in terms of the

horizontal and vertical differentiations of the language, the first

in accordance with the sphere of social activity, the second – with

its situational variability. Situational varieties of the language

are called functional dialects or functional styles and situational

pronunciation varieties – situational accents or phonostyles.

-2-

Nowadays

two main types of English are spoken in the English-speaking world:

English English and American English.

According to British

dialectologists (P. Trudgill, J. Hannah, A. Hughes and others) the

following variants of English are referred to the English-based

group: English English, Welsh English, Australian English, New

Zealand English; to the American-based group: United States English,

Canadian English.

Scottish English and Irish

English fall somewhere between the two being somewhat by themselves.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

THE ELEMENTS OF PRONUNCIATION.

Pronunciation is understood to include:-

- intonation

- stress (on words and in sentences)

- phonology (the sounds of the language)

Not all textbooks agree that the concept of pronunciation should be taught in this order although the sounds produced in individual words should come without too much difficulty if intonation and stress are focussed upon within the structure of a sentence or phrase.

Mastering ‘pronunciation’ as a feature of English involves students in three main areas:

‘Awareness’ exercises means listening to differences in intonation or differences between words. You can listen out for the mood of a speaker or you can listen for differences in words bet/bit/bat

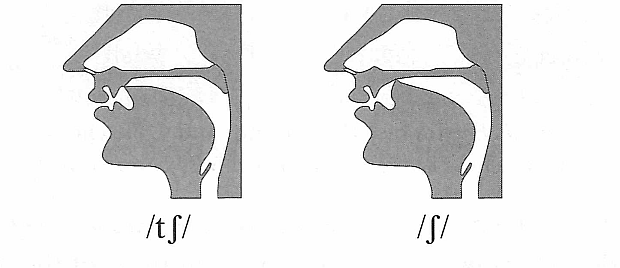

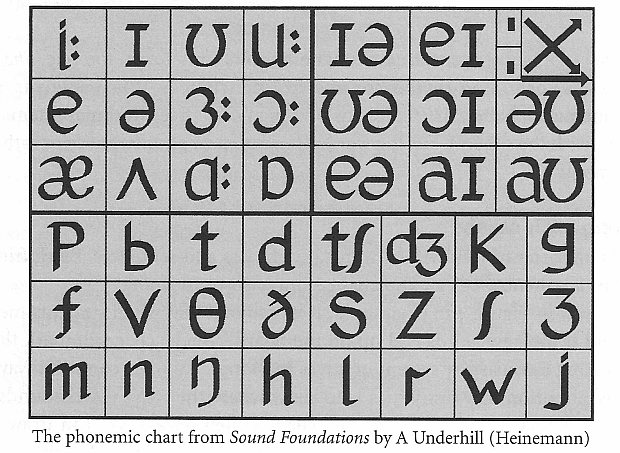

‘Independence’ exercises help students to learn things for themselves and include teaching them how to use a dictionary, the phonemic chart and about patterns in words.

‘Mouth’ exercises are when students say something themselves in order to practice the sounds physically — to practice moving their mouth into the right shape..

You should integrate A, I and M exercises into your work. Learners may still have bad pronunciation even when they are quite advanced learners in terms of their good grammatical knowledge and wide vocabulary. Make learning fun so they are not shy!

A I M to teach pronunciation. A little bit every day, every lesson.

a) INTONATION

Intonation is to do with how you say a word or phrase rather than what you say. Speakers can change the pitch of their voice making it higher or lower as and when required. Thus intonation is the ‘music’ of speech which can convey various feelings or attitudes such as surprise, curiosity, boredom, politeness, abruptness etc. It is important for the speaker to convey his appropriate feelings at the time otherwise an incorrect impression might be gained by the listener and confusion or offence might be caused. Intonation is also used for the more mundane job of showing whether a speaker has finished speaking or not.

It is difficult to learn the rules of intonation as English has a wide intonation range compared with other languages; nevertheless students should be encouraged to acquire them naturally rather than to consciously learn them.

SELF-CHECK 2:2 1

When teaching English to students with little experience of the language, teachers should note that there are two basic intonation patterns:

The rising tone which is used in questions expecting a yes/no response or to express surprise, disbelief etc. The voice rises sharply on the stressed syllable.

eg The single word — Really? expects a yes/no response

As does:-

Did you see the Queen?

Would you like a scone?

The rising tone is also used mid-sentence to show that the speaker has not finished speaking — for example in listing:

I bought potatoes, mangoes and carrots

The falling tone is used for statements, commands and for wh… questions. The voice rises sharply earlier in the sentence and then falls on the key word being stressed.

eg How’s your brother?

Stand back!

Two returns to Bristol, please.

As we said above, it is also used for indicating when a speaker is finishing what he/she has to say.

In repetition activities there are two main techniques of demonstrating falling and rising tones: the first is by gesture using arm and hand movements, the teacher taking care that the student will observe each movement starting on the left and finishing on the right; the second is simply by drawing arrows on the blackboard after the sentence or phrase, thus or /.

STRESS

Stress refers to the emphasis we place on the syllable of a word (word stress) or on (a) word(s) within a sentence (sentence stress). It presents great difficulty for the foreign learner of English.

Unlike a language such as Spanish, there are no easy rules in governing where the stress falls on a word. We have all made mistakes ourselves when pronouncing a word we have not seen or heard before. A native speaker can only work from experience with similar words but is not always guided towards correct pronunciation.

SENTENCE STRESS

If we take the average sentence or utterance in English we will find stressed and unstressed words. The speaker will demonstrate the words that are of most importance to the listener by stressing them more, ie by making them more audible. For example, in the sentence

«I’ve lost my wallet!»

the words which are of most importance are ‘lost‘ and ‘wallet‘ and they will therefore be stressed. It also helps to remember that NEW information is stressed in a sentence. Shared information is not:

Look at this sentence:

Mary’s given birth to a girl!

The sex of the new baby is the new information. The fact that the baby is Mary’s is already shared by both speakers and is not stressed.

However:

Mary’s given birth to a girl.

In this case the birth of a girl baby is known about already but some wrong information has been given and the speaker is correcting- giving NEW information that the baby in fact belongs to Mary not anyone else.

English makes ample use of stress in order to point to a context. You can ask the same question but can place the stress on different words depending on which fact you would like to have confirmed or denied.

eg Is Bernard going to France in July? (Stress on Bernard)

No, Zoe is.

Is Bernard going to France in July? (Stress on France)

No, he’s going to Belgium.

Is Bernard going to France in July? (Stress on July)

No, he’s going in August.

There are various ways of marking where the stress falls in a sentence or a word. Some E.S.O.L. teachers draw small squares above the place where the stress falls. For written exercises you could mark the stressed syllable in bold or underline where the stress falls.

SELF-CHECK 2:2 2

As already stated, in English we place stress on the most important parts of the sentence or message we wish to be conveyed. The unstressed part of the sentence is more difficult to catch so the foreign learner has to train his ear to pick up the less important part of the message so he/she can fully understand what is being said.

English is often referred to as a ‘stress-timed’ language. This means that the length of time between the stressed syllables is always about the same. The greater the number of unstressed syllables between those that are stressed, the quicker the unstressed syllables are uttered.

eg He gave a speech.

He gave a short speech.

He gave a very short speech.

In each sentence, the unstressed syllables ( ‘a’, ‘a short‘, ‘a very short‘ ) took about the same amount of time to say, so ‘a very short‘ had to be said more quickly.

However, there are times when normally unstressed words are stressed for obvious reasons:-

eg Bill and George are coming to the party (stressing that George is to be included in the party guest list).

‘And‘ and lots of other small words or weak forms (listed below) are habitually unstressed within the structure of a sentence unless used in isolation.

Unstressed words in speech do not always retain their original pronunciation.

Vowels change into different forms (see the next section).

Consonant clusters get pushed together and even left out without us losing the meaning of the word.

Read these two sentences aloud and listen to the change in the words

‘last chance’ which contain 3 consonant sounds in the middle — ‘s’ ‘t’ and ‘ch’. In the second sentence they are not pronounced clearly and separately because the words are not stressed.

John, your last chance to hand in your work is tomorrow.

But your last chance, Peter, was yesterday!

WEAK FORMS

Prepositions:- at, to, of, for, from

Auxiliary and modal verbs: be, been, am, is, are, was, were, have, has, had, do, does, shall, should, will, would, can, could, must

Pronouns: me, he, him, his, she, we, us, you, your, them

Others: who, that (as a relative pronoun), a, an, the, some, and, but, as, than, there, not

The sound produced in the weak form is called ‘shwa’ and is represented by the phonemic symbol as seen on the phonemic script chart at the end of this unit, like a back to front upside down ‘e’. The sound is the one that needs the minimum effort from your mouth — a sort of small grunt. Full vowels would take too much effort and time to say in connected speech and slow it down. So the schwa is the ‘default’ sound to help the speaker progress at speed.

Practise these examples. The weak forms are selected.

Take a look at it.

It’s for you.

I was here yesterday.

We must go.

Stress-timing is a noticeable characteristic of the spoken language. By getting used to hearing English spoken with a natural rhythm in class, students will find it easier to understand real English beyond the confines of the classroom. It will take some time however, for the students themselves to produce this sort of language so they need a lot of time and every encouragement in this endeavour.

If you have a tape recorder or other means of recording your own voice, then try reading a short paragraph from any piece of writing, fiction or non-fiction and listen to how you ‘elide’ — slip together — the words as you are reading at normal speed. If English is not your first language and you might read slowly and carefully, then you can also listen to yourself reading in your own language. All languages have a rhythm.

SOUNDS OF THE LANGUAGE/PHONOLOGY

It is important when teaching students new vocabulary to indicate where the stress falls. With the majority there is no argument

eg programme completely lesson intention

Remember, the stressed syllable is longer and more audible.

With other words there is disagreement on pronunciation, sometimes depending on your origins.

eg harass and harass (American origin)

advertisement and advertisement (localised northern pronunciation)

Carlisle and Carlisle (local pronunciation)

At other times it is essential to differentiate:

eg invalid (noun = incapacitated person )

invalid (adjective = cannot be accepted)

Unstressed syllables are often pronounced as shwa (see chart) regardless of spelling. It is the vowel sound many British people make when hesitating in speech, spelt as ‘uh’ or ‘er’. Here are some examples:-

Occupations: teacher, driver, doctor, sailor

Comparatives: longer, bigger, better

Beginning with ‘a’: ago, about, along

Ending in : ‘-ory’, ‘-ary : factory, library

Ending : ‘-ion’, ‘-ian’ : nation, Egyptian

Ending : ‘-man’ : woman

Days: Sunday, etc.

Plurals: horses, matches etc.

Third person endings: washes etc.

Superlatives: shortest, fastest etc.

Ending ‘-age’, ‘-ege’ : luggage, language, college

Beginning ‘be-‘, ‘re-‘ : begin, reply

VOWELS AND CONSONANTS

All sounds, whether they are made by a vowel or a consonant are represented by a phonemic symbol (see chart) to enable the native as well as the foreign speaker to pronounce words correctly. The same letters or combination of letters can make a different sound eg a word such as ‘the’ is pronounced differently according to whether a vowel or a consonant follows. Compare the pronunciation of ‘the’ before ‘book’ with ‘the’ before ‘apple’.

In English there are variations in the pronunciation of the same vowels

eg contrast

hat — hard

bed — beer

bid — bird

dog — do — ford

cut — cute — could

As you can see from this, different letters can be pronounced in an identical way : note the case of ‘do’ and ‘cute’.

There are two types of vowel in English: those represented by the phonemic symbols above are monothongs meaning that the vowel sound consists of one phoneme. (A phoneme is the smallest unit of speech) There are also diphthongs which are often recognised by two vowels together, but not always.

‘Beer’ contains a diphthong, where you experience a gradual change in lip and tongue position during the making of the sound. ‘Bay’ is another example, it is monosyllabic but has two phonemes.

In all there are 20 vowel sounds and 24 consonant sounds compared with, for example, Japanese and Spanish that have only 5 vowel sounds.

SELF-CHECK 2:2 3

Dictionaries, both monolingual and good bilingual, clearly mark both stress and pronunciation on words. You should use one to check anything you are not sure of and should work with your students to make sure they

- have a dictionary (!)

- know how to use it effectively!

SELF-CHECK 2:2 4

BEING A PRONUNCIATION TEACHER

As a teacher you should know the phonemic chart, have it on the wall of the classroom and know how to use it when you use the dictionary. You can find the phonemic chart at the front or the back of any good English dictionary.

Have a standard technique for marking the word stress of new words on your board work:

poTAto and postcard

Be aware of what a ‘schwa’ sound is. This will help your students to imitate natural speech.

Be aware of what a ‘schwa’ sound is. This will help your students to imitate natural speech.

Think carefully every lesson about when and how you are going to spend a little time on the sounds of English. Remember: AIM

Here are some top tips on how you can include ‘sound’ work in your lessons:

- Use the phonemic symbols next to new words on the board. If you do not know them, then start now! Mark the stress of all new words on the board and in handouts. PoTAto

- Use clapping and rhythmic tapping to show sentence stress and make all the students say the sentence IN TIME with you. This gives the sentence the correct rhythm.

- Have students practice saying short phrases (perhaps from a coursebook dialogue) in different ways:

eg Can I help you? (smiling, bored, angry, nervous) and discuss how the intonation changes.

- Have students do speak and write activities with word cards in pairs and groups.

- Dictate short phrases to students at normal speed and have them write them down in order to show them how elision and rhythm work.

- Use simple poetry to highlight rhythm and stress — it is also fun!

- Make pronunciation a game — exaggerate the pronunciation of new words and phrases and have students do the same so that they are no longer embarrassed.

- Use the dictionary to find out how things are pronounced — you can turn this into a research and pronounce game in teams.

- Introduce new words in groups -ation words, for example, and highlight and practice the common word stress pattern and pronunciation.

SELF-CHECK 2:2 5

USING DIALOGUES

Many coursebooks have dialogues so make sure you use them.

Before the lesson starts, see if there is a good intonation pattern on one phrase in the dialogue. Choose a few phrases that you would like them to say well. Can the students copy them?

Make sure that you have a good model for the dialogues you present. Most coursebooks have a recording to listen to, so use it. Do not have the students reading the dialogue aloud before they hear it.

If you set up information gap activities — where students have to give each other information such as directions to a place on a map or information about opening times of a museum — make sure that they are trying to speak clearly and checking if their listener has understood. Encourage students to say things like ‘I’m sorry I didn’t catch that’, and repeat the instructions back to whoever gave them, not revert to Arabic. These are communication strategies and are very important.

Add a pronunciation corner to your lesson plan aims and you will soon see the difference in your classes! Try these self check exercises.

SELF-CHECK 2:2 6

SELF-CHECK 2:2 7

Now consider the following extract:

Teaching pronunciation

Pronunciation teaching not only makes students aware of different sounds and sound features (and what these mean), but can also improve their speaking immeasurably. Concentrating on sounds, showing where they are made in the mouth, making students aware of where words should be stressed — all these things give them extra information about spoken English and help them achieve the goal of improved comprehension and intelligibility.

In some particular cases, pronunciation help allows students to get over serious intelligibility problems. Joan Kerr, a speech pathologist, described (in a paper at the 1998 ELICOS conference in Melbourne, Australia) how she was able to help a Cantonese speaker of English achieve considerably greater intelligibility by working on his point of articulation — changing his focus of resonance. Whereas many Cantonese vowels occur towards the back of the mouth, English ones are frequently articulated nearer the front or in the centre of the mouth. The moment you can get Cantonese speakers, she suggested, to bring their vowels further forward, increased intelligibility occurs. With other language groups it may be an issue of nasality (e.g. Vietnamese) or the degree to which speakers do or do not open their mouths. Some language groups may have particular intonation or stress patterns in phrases and sentences which sound strange when replicated in English, and there are many individual sounds which cause difficulty for speakers of various different first languages.

For all these people, being made aware of pronunciation issues will be of immense benefit not only to their own production, but also to their understanding of spoken English.

Perfection versus intelligibility

A question we need to answer is how good our students’ pronunciation ought to be. Should they sound exactly like speakers of a prestige variety of English so that just by listening to them we would assume that they were British, American, Australian or Canadian? Or is this asking too much? Perhaps their teacher’s pronunciation is the model they should aspire to. Perhaps we should be happy if they can at least make themselves understood.

The degree to which students acquire ‘perfect’ pronunciation seems to depend very much on their attitude to how they speak and how well they hear. In the case of attitude, there are a number of psychological issues which may well affect how ‘foreign’ a person sounds when they speak English. Some students, as Vicky Kuo suggests, want to be exposed to a ‘native speaker’ variety, and will strive to achieve pronunciation which is indistinguishable from that of a first language English speaker. Other students, however, do not especially want to sound like ‘inner circle’ speakers; frequently they wish to be speakers of English as an international or global language and this does not necessarily imply trying to sound exactly like someone from Britain or Canada. It may imply sounding more like their teacher, whatever variety he or she speaks. Frequently, too, students want to retain their own accent when they speak a foreign language because that is part of their identity. Thus speaking English with, say, a Mexican accent is fine for the speaker who wishes to retain his or her ‘Mexican-ness’ when speaking in a foreign language.

Under the pressure of such personal, political and phonological considerations it has become customary for language teachers to consider intelligibility as the prime goal of pronunciation teaching. This implies that the students should be able to use pronunciation which is good enough for them to be always understood. If their pronunciation is not up to this standard, then clearly there is a serious danger that they will fail to communicate effectively.

If intelligibility is the goal, then it suggests that some pronunciation features are more important than others. Some sounds, for example, have to be right if the speaker is to get their message across, though others may not cause a lack of intelligibility if they are used interchangeably. In the case of individual sounds, a lot depends on the context of the utterance, which frequently helps the listener to hear what the speaker intends. However, stressing words and phrases correctly is vital if emphasis is to be given to the important parts of messages and if words are to be understood correctly. Intonation is a vital carrier of meaning; by varying the pitch of our voice we indicate whether we are asking a question or making a statement, whether we are enthusiastic or bored, or whether we want to keep talking or whether, on the contrary, we are inviting someone else to come into the conversation.

The fact that we may want our students to work towards an intelligible pronunciation rather than achieve an L1-speaker perfection may not appeal to all, however. Despite what we have said about identity and the global nature of English (and the use of ELF), some students do indeed wish to sound exactly like a native speaker. In such circumstances it would be absurd to try to deny them such an objective.

Problems

Two particular problems occur in much pronunciation teaching and learning.

What students can hear: some students have great difficulty hearing pronunciation features which we want them to reproduce. Frequently, speakers of different first languages have problems with different sounds, especially where, as with Ibl and Ivl for Spanish speakers, their language does not have the same two sounds. If they cannot distinguish between them, they will find it almost impossible to produce the two different English phonemes. There are two ways of dealing with this: in the first place, we can show students how sounds are made through demonstration, diagrams and explanation. But we can also draw the sounds to their attention every time they appear on a recording or in our own conversation. In this way we gradually train the students’ ears. When they can hear correctly, they are on the way to being able to speak correctly.

What students can say: all babies are born with the ability to make the whole range of sounds available to human beings. But as we grow and focus in on one or two languages, we lose the habit of making some of those sounds. Learning a foreign language often presents us with the problem of physical unfamiliarity (i.e. it is actually physically difficult to make the sound using particular parts of the mouth, uvula or nasal cavity). To counter this problem, we need to be able to show and explain exactly where sounds are produced (e.g. Where is the tongue in relation to the teeth? What is the shape of the lips when making a certain vowel?) .

The intonation problem: for many teachers the most problematic area of pronunciation is intonation. Some of us (and many of our students) find it extremely difficult to hear tunes or to identify the different patterns of rising and falling tones. In such situations it would be foolish to try to teach them. However, the fact that we may have difficulty recognising specific intonation tunes does not mean that we should abandon intonation teaching altogether. Most of us can hear when someone is surprised, enthusiastic or bored, or when they are really asking a question rather than just confirming something they already know. One of our tasks, then, is to give students opportunities to recognise such moods and intentions either on an audio track or through the way we ourselves model them. We can then get students to imitate the way these moods are articulated, even though we may not (be able to) discuss the technicalities of the different intonation patterns themselves.

The key to successful pronunciation teaching, however, is not so much getting students to produce correct sounds or intonation tunes, but rather to have them listen and notice how English is spoken — either on audio or video or by their teachers themselves. The more aware they are, the greater the chance that their own intelligibility levels will rise.

Phonemic symbols: to use or not to use?

It is perfectly possible to work on the sounds of English without ever using any phonemic symbols. We can get students to hear the difference, say, between sheep and cheap or between ship and sheep just by saying the words enough times. There is no reason why this should not be effective. We can also describe how the sounds are made (by demonstrating, drawing pictures of the mouth and lips or explaining where the sounds are made).

However, since English is bedevilled, for many students, by an apparent lack of sound and spelling correspondence (though in fact most spelling is highly regular and the number of exceptions fairly small), it may make sense for them to be aware of the different phonemes, and the clearest way of promoting this awareness is to introduce the symbols for them.

There are other reasons for using phonemic symbols, too. Paper dictionaries usually give the pronunciation of headwords in phonemic symbols. If students can read such symbols, they can know how the word is said even without having to hear it. Online and CD-ROM dictionaries have recordings of words being said, of course.

When both teacher and students know the symbols, it is easier to explain what mistake has occurred and why it has happened; we can also use the symbols for pronunciation tasks and games.

Some teachers complain that learning symbols places an unnecessary burden on students. For certain groups this may be true, and the level of strain is greatly increased if they are asked to write in phonemic script (Newton 1999). But if they are only asked to recognise rather than produce the different symbols, then the strain is not so great, especially if they are introduced to the various symbols gradually rather than all at once.

When to teach pronunciation

Just as with any aspect of language — grammar, vocabulary, etc. — teachers have to decide when to include pronunciation teaching in lesson sequences. There are a number of alternatives to choose from.

Whole lessons: some teachers devote whole lesson sequences to pronunciation, and some schools timetable pronunciation lessons at various stages during the week. Though it would be difficult to spend a whole class period working on one or two sounds, it can make sense to work on connected speech, concentrating on stress and intonation, over some 45 minutes, provided that we follow normal planning principles. Thus we could have students do recognition work on intonation patterns, work on the stress in certain key phrases, and then move on to the rehearsing and performing of a short play extract which exemplifies some of the issues we have worked on. Making pronunciation the main focus of a lesson does not mean that every minute of that lesson has to be spent on pronunciation work. Sometimes students may also listen to a longer recording, working on listening skills before moving to the pronunciation part of the sequence. Sometimes they may look at aspects of vocabulary before going on to work on word stress and sounds and spelling.

Discrete slots: some teachers insert short, separate bits of pronunciation work into lesson sequences. Over a period of weeks, they work on all the individual phonemes, either separately or in contrasting pairs. At other times they spend a few minutes on a particular aspect of intonation, say, or on a contrast between two or more sounds. Such separate pronunciation slots can be extremely useful, and provide a welcome change of pace and activity during a lesson. Many students enjoy them, and they succeed precisely because we do not spend too long on any one issue. However, pronunciation is not a separate skill; it is part of the way we speak. Even if we want to keep our pronunciation phases separate for the reasons we have suggested, we will also need times when we integrate pronunciation work into longer lesson sequences.

Integrated phases: many teachers get students to focus on pronunciation issues as an integral part of a lesson. When students listen to a recording, for example, one of the things which we can do is to draw their attention to pronunciation features on the recording, if necessary having them work on sounds that are especially prominent, or getting them to imitate intonation patterns for questions, for example. Pronunciation teaching forms a part of many sequences where students study language form. When we model words and phrases, we draw our students’ attention to the way they are said; one of the things we want to concentrate on during an accurate reproduction stage is the students’ correct pronunciation.

Opportunistic teaching: just as teachers may stray from their original plan when lesson realities make this inevitable, and teach vocabulary or grammar opportunistically because it has ‘come up’, so there are good reasons why we may want to stop what we are doing and spend a minute or two on some pronunciation issue that has arisen in the course of an activity. A lot will depend on what kind of activity the students are involved in since we will be reluctant to interrupt fluency work inappropriately, but tackling a problem at the moment when it occurs can be a successful way of dealing with pronunciation.

Although whole pronunciation lessons may be an unaffordable luxury for classes under syllabus and timetable pressure, many teachers tackle pronunciation in a mixture of the ways suggested above.

Helping individual students

We frequently work with the whole class when we organise pronunciation teaching. We conduct drills with minimal pairs or we have all of the students working on variable stress in sentences together. Yet, as we have seen, pronunciation is an extremely personal matter, and even in monolingual groups, different students have different problems, different needs and different attitudes to the subject. In multilingual groups, of course, students from different language backgrounds may have very different concerns and issues to deal with.

One way of responding to this situation, especially when we are working with phonemes, is to get students to identify their own individual pronunciation difficulties rather than telling them, as a group, what they need to work on. So, for example, when revising a list of words we might ask individual students which words they find easy to pronounce and which words they find difficult. We can then help them with the difficult words. We can encourage students to bring difficult words to the lesson so that we can help them with them. This kind of differentiated teaching is especially appropriate because students may be more aware of their pronunciation problems — and be able to explain what they are — than they are with grammar or vocabulary issues.

It is vitally important when correcting students to ensure that we offer help in a constructive and useful way. This involves us showing students which parts of the mouth they need to use, providing them with words in their phonological context, and offering them continual opportunities to hear the sounds being used correctly.

Examples of pronunciation teaching

The areas of pronunciation which we need to draw our students’ attention to include individual sounds they are having difficulty with, word and phrase/sentence stress and intonation. But students will also need help with connected speech for fluency and with the correspondence, or lack of it, between sounds and spelling.

Here are some practical examples:

Working with sounds

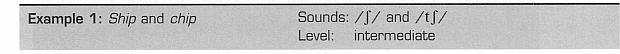

Contrasting two sounds which are very similar and often confused is a popular way of getting students to concentrate on specific aspects of pronunciation.

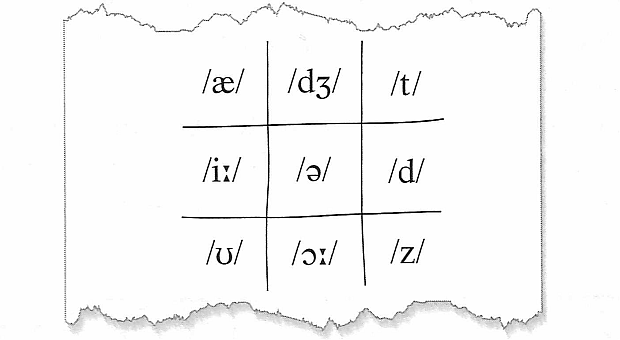

The sequence starts with students listening to pairs of words and practising the difference between the two targeted phonemes:

If they have no problem with these sounds, the teacher may well move on to other sounds and/or merely do a short practice exercise as a reminder of the difference between them. But if the students have difficulty discriminating between the targeted sounds, the teacher asks them to listen to a recording and, in a series of exercises, they have to work out which word they hear, e.g.:

They now move on to exercises in which they say words or phrases with one sound or the other:

It’s very cheap

a grey chair

a cheese sandwich

You cheat!

no chance

a pretty child

before doing a communication task which has words with the target sounds built into it:

If, during this teaching sequence, students seem to be having trouble with either of the sounds, the teacher may well refer to a diagram of the mouth to help them see where the sounds are made:

Contrasting sounds in this way has a lot to recommend it. It helps students concentrate on detail, especially when they are listening to hear the small difference between the sounds. It identifies sounds that are frequently confused by various nationalities. It is manageable for the teacher (rather than taking on a whole range of sounds at the same time), and it can be good fun for the students.

This kind of exercise can be done whether or not the teacher and students work with phonemic symbols.

The writer Adrian Underhill is unambiguous about the use of phonemic symbols and has produced a phonemic chart, which he recommends integrating into English lessons at various points.

This phonemic chart is laid out in relation to where in the mouth the 44 sounds of southern British English are produced. In its top right-hand corner little boxes are used to describe stress patterns, and arrows are used to describe the five basic intonation patterns (i.e. fall, rise, fall-rise, rise-fall and level).

What makes this chart special are the ways in which Adrian Underhill suggests that it should be used. Because each sound has a separate square, either the teacher or the students can point to that square to ask students to produce that sound and/or to show they recognise which sound is being produced. For example, the teacher might point to three sounds one after the other to get the students to say sh-o-p. Among other possibilities, the teacher can say a sound or a word and a student has to point to the sound(s) on the chart. When learners say something and produce an incorrect sound, the teacher can point to the sound they should have made. When the teacher first models a sound, she can point to it on the chart to identify it for the students (Underhill 2005: 101).

The phonemic chart can be carried around by the teacher or left on the classroom wall. If it is permanently there and easily accessible, the teacher can use it at any stage when it becomes appropriate. Such a usable resource is a wonderful teaching aid, as a visit to many classrooms where the chart is in evidence will demonstrate.

There are many other techniques and activities for teaching sounds apart from the ones we have shown here. Some teachers play sound bingo where the squares on the bingo card have sounds, or phonemically ‘spelt’ words instead of ordinary orthographic words. When the teacher says the sound or the word, the student can cross off that square of their board.

When all their squares are crossed off, they shout Bingo! Noughts and crosses can be played in the same way, where each square has a sound and the students have to say a word with that sound in it to win that square, e.g.

Teachers can get students to say tongue-twisters sometimes, too (e.g. She sells sea shells by the sea shore) or to find rhymes for poetry/limerick lines. When students are familiar with the phonemic alphabet, they can play ‘odd man out’ (five vocabulary items where one does not fit in with the others), but the words are written in phonemic script rather than ordinary orthography.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.

You can tell a lot about the meaning behind someone’s words by assessing their intonation. The same sentence can hold a very different meaning in different contexts, and the intonation used will heavily influence this meaning.

There are several intonation types you need to be aware of; this article will cover some intonation examples and explain the difference between prosody and intonation. There are a few other terms that are closely linked to intonation that you’ll need to understand too. These include intonation vs. inflection and intonation vs. stress.

Intonation Definition

To begin, let’s look at a quick definition of the word intonation. This will give us a solid foundation from which to continue exploring this topic:

Intonation refers to how the voice can change pitch to convey meaning. In essence, intonation replaces punctuation in spoken language.

E.g., «This article is about intonation.» In this sentence, the full stop signifies where the pitch falls.

«Would you like to continue reading?» This question ends in a question mark, which shows us that the pitch rises at the end of the question.

Pitch refers to how high or low a sound is. In the context of this article, the sound we’re concerned with is the voice.

We are able to make our voices get higher or deeper (change the pitch of our voices) by altering the shape of our vocal cords (or vocal folds). When our vocal cords are stretched out more, they vibrate more slowly as air passes through them. This slower vibration causes a lower or deeper sound. When our vocal cords are shorter and thinner, the vibration is faster, creating a higher-pitched sound.