English students often learn syllable and word stress rules before venturing into sentence stress. This is because sentence stress rules are far more variable and complex, while the rules for correct intonation in English generally stay the same. To demonstrate the differences, let’s look at a few different examples of stress in English.

Syllable Stress vs. Sentence Stress

When you learn how to pronounce different vowel and consonant sounds, you must also learn how to stress different parts of a word correctly. Stress is just another way to say “emphasize.” This means that some parts of a word are stronger (and slightly louder) than others. Here are a few examples:

- Away (pronounced: a-WAY)

- Delicious (pronounced: de-LI-cious)

- Anticipate (pronounced: an-TI-ci-PATE)

- Communication (pronounced: comm-un-i-CA-tion)

- Autobiography (pronounced: au-to-bi-O-gra-phy)

Some longer words have a primary stressed syllable and one or more secondary stressed syllables. The primary stressed syllable is always stronger than the secondary stressed syllable, while both are stronger than unstressed syllables. Be sure to check out our guide on stressed and unstressed syllables to learn more about using proper English intonation.

Sentence stress refers to the words in a sentence that get the most emphasis. While common sayings and phrases usually have unchanging sentence stress rules, you can emphasize different words in a sentence to create new meanings. For example, let’s look at the common saying: I told you so!

The most common way to say this phrase is to put the primary stress on “told” and the secondary stress on “so,” like this:

I TOLD you SO!

However, you could also change the implicit meaning of the phrase by emphasizing “I.” By doing this, you will stress the fact that you (the speaker) were the one who told them (the listener) about something.

Which words should you stress in a sentence?

So, how can you know which words to stress in a sentence? Again, there are no hard-and-fast sentence stress rules, but there are some general principles that will help you use stress properly when speaking in English. You can often tell which words should be stressed based on the parts of speech and where the words fall in a sentence.

- Content words (nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and main verbs) are usually stressed.

- Function words (determiners, prepositions, and conjunctions) are usually unstressed unless you want to emphasize their role(s) in a sentence.

- Question words (who, what, when, where, why, and how) are usually unstressed unless you want to emphasize their role(s) in a sentence.

- Subject pronouns (I, You, He, She, We, They) are usually unstressed, while object pronouns (me, you, him, her, us, them) are usually stressed.

Sentence Stress in a Statement

| Pronoun | Main Verb | Adverb | Preposition | Determiner | Noun |

| I | ran | quickly | to | the | desk. |

| unstressed | unstressed | STRESSED (primary) | unstressed | unstressed | STRESSED (secondary) |

This example denotes the natural rise and fall of the sentence. However, as previously stated, you could stress different words to alter the meaning:

- I ran quickly to the desk. (emphasizes who is doing the running)

- I ran quickly to the desk. (emphasizes what action is being done)

- I ran quickly to the desk. (emphasizes the way in which you ran, but does not fundamentally change the meaning of the sentence)

- I ran quickly to the desk. (inappropriate sense stress, but emphasizes the direction in which you ran)

- I ran quickly to the desk. (inappropriate sense stress, but emphasizes that it was a specific desk)

- I ran quickly to the desk. (emphasizes the object or location to which you ran)

Sentence Stress in a Question

| Pronoun | Modal Verb | Main Verb | Preposition | Determiner | Noun |

| Who | will | come | to | the | party? |

| unstressed | unstressed | STRESSED (primary) | unstressed | unstressed | STRESSED (secondary) |

Like the previous example, the sentence stress here also denotes the natural rise and fall of the word combination. However, you could still ask this question six different ways to convey six slightly different meanings:

- Who will come to the party? (you want to know who the party attendees are)

- Who will come to the party? (you want to know who will definitely be attending the party)

- Who will come to the party? (you want to know who will attend the party, but this form does not change the standard meaning of the question)

- Who will come to the party? (inappropriate sense stress, but emphasizes the location of the party)

- Who will come to the party? (inappropriate sense stress, but emphasizes which party you’re talking about)

- Who will come to the party? (you want to emphasize the party, possibly in contrast to a separate event)

Sentence Stress and Intonation in English

If you couldn’t already tell, sentence stress is often linked to the way our voices rise and fall (intonation) while speaking. The natural rise and fall in pitch usually determines which words are stressed and unstressed. This is why the two example sentences above have similar structures. They are both examples of falling intonation.

In American English, there are two basic types of intonation: rising intonation and falling intonation. Falling intonation is far more common. When you speak with falling intonation, the pitch of your voice starts high and gets lower by the end of the sentence. More often than not, sentences with falling intonation use stressed verbs and objects. For example:

- I saw a crab at the beach.

- They never return my calls.

- Frank is a responsible person.

- My dad doesn’t like to wash the dishes.

Alternatively, rising intonation occurs when the pitch of your voice starts lower and gets higher at the end of the sentence. This type of intonation is less common, but you can use it when you want to ask a Yes/No question or when you want to express a negative emotion, like anger. Similarly, the stress often falls on verbs and objects, though this can vary depending on the meaning you want to convey. Here are some examples:

- Are you sure?

- Do you want to go to the park?

- You’re so mean!

- I don’t want to talk to you!

What is sense stress?

You might have heard of sense stress, which is very similar to the concept of sentence stress. Sense stress simply refers to the use of stress on different words to convey different meanings. Thus, sense stress is a form of sentence stress. Usually, people refer to appropriate or inappropriate sense stress. Appropriate sense stress sounds natural and correctly conveys the meaning of a sentence. Here are some examples of appropriate sense stress:

- How many HAMBURGERS should we get?

- What TIME is it?

- He ANSWERED the phone.

- They did NOT want to go swimming.

Alternatively, inappropriate sense stress sounds unnatural and conveys strange or incorrect meanings. Here are a few examples:

- Where do you want to eat?

- Did you go to the doctor?

- I never go to the supermarket by myself.

- She was watching a movie when the guests arrived.

Conclusion

Sentence stress is an element of English that can be difficult to grasp, especially for beginner or even intermediate learners. However, with practice, you can use stress to accurately express yourself. With time, you’ll find that sense and sentence stress are some of the best ways to get your point across to other English speakers!

If you’d like to hear native English speakers using sentence stress, be sure to subscribe to the Magoosh Youtube channel!

The stress placed on syllables within words is

called word stress or lexical

stress. The stress placed on words

within sentences is called sentence

stress or prosodic

stress.

Sentence stress is a greater prominence of words which are made more

prominent in the international group. The prominence of accented

words is achieved through the greater force of utterance and changes

in the direction of voice pitch.

Stress in utterance provide the basis for understanding the content,

they help to perform constitutive, distinctive, indemnificatory

function of intonation.

Word stress is definitely the key to understanding spoken English and

it is used so naturally by native speakers of the English language

that they are not even aware they are doing it. When non native

speakers talk to English natives without the use of word stress they

are likely to encounter two problems:

1. The listener will find it difficult to understand the fast

speaking native.

2. The native speakers may find it difficult to understand the non

native speakers.

Any word spoken in isolation has at least one prominent syllable. We

perceive it as stressed. Stress in the isolated word is termed word

stress, stress in connected speech is termed sentence stress. Stress

is indicated by placing a stress mark before the stressed syllable.

Stress is defined differently by different

authors. B. A. Bogoroditsky,

for instance, defined stress as an

increase of energy, accompanied by an

increase of expiratory and

articulatory activity. D. Jones defined stress as

the degree of

force, which is accompanied by a strong force of exhala

tion

and gives an impression of loudness. H.

Sweet also stated that stress

is

connected with the force of breath.

Word stress can be defined as the singling out of one or more

syllables in a word, which is accompanied by the change of the

force of utterance, pitch of the voice, qualitative and quantitative

characteristics of the sound, which is usually a vowel.

-

Theories of syllable formation and syllable division.

The syllable is a complicated phenomenon and like

a phoneme it can be studied on four levels — articulatory, acoustic,

auditory and functional.

The complexity of the phenomenon gave rise to many theories.

We could start with the so-called expiratory

(chest pulse or pressure) theory by R.H. Stetson.

This theory is based on the assumption that expiration in speech is a

pulsating process and each syllable should correspond to a single

expiration. So the number of syllables in an utterance is determined

by the number of expirations made in the production of the utterance.

This theory was strongly criticized by Russian and foreign linguists.

G.P. Torsuyev,

for example, wrote that in a phrase a number of words and

consequently a number of syllables can be pronounced with a single

expiration. This fact makes the validity of the theory doubtful.

Another theory of syllable put forward by O.

Jespersen is generally called the

sonority theory.

According to O. Jespersen, each sound is characterized by a certain

degree of sonority which is understood us acoustic property of a

sound that determines its perceptibility. According to V.A.

Vassilyev the most serious drawback of

this theory is that it fails to explain the actual mechanism of

syllable formation and syllable division. Besides, the concept of

sonority is not very clearly defined.

Further experimental work aimed to description of

the syllable resulted in lot of other theories. However the question

of articulatory mechanism of syllable in a still an open question in

phonetics. We might suppose that this mechanism is similar in all

languages and could be regarded as phonetic universal.

In Russian linguistics there has been adopted

the theory of syllable by LV Shcherba.

It is called the theory of muscular tension. In most languages there

is the syllabic phoneme in the centre of the syllable which is

usually a vowel phoneme or, in some languages, a sonorant. The

phonemes preceding or following the syllabic peak are called

marginal. The tense of articulation increases within the range of

prevocalic consonants and then decreases within the range of

postvocalic consonants.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

By

Last updated:

August 16, 2022

Every language has a rhythm.

When you learn a new language, you use the rhythm and music from your native language without meaning to.

But when you do this, your English might sound off-beat!

By improving your rhythm and sentence stress in English, you’ll be improving your speaking and listening skills, as well.

Contents

- What Is Sentence Stress in English?

-

- Content words

- Structure words

- Focus Words in Sentence Stress

-

- Pitch changes in focus words

- Thought Groups

- Sources to Master Sentence Stress

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

What Is Sentence Stress in English?

So you know that sentence stress is the music of the language, but what does that mean exactly? English is a stress-timed language that has a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables and words. You change stress to emphasize, give new information, contrast information or to clarify.

In other words, English lets you put the stress on different words (or parts of words) to change the meaning of the whole sentence. You can make some information more important than the rest of the sentence through sentence stress.

In English, we have content words and structure words. You can think about it in terms of “strong” and “soft” beats.

Content words

Content words are the “strong” beats and usually include words with more lexical (more in-depth) meaning, such as nouns (cat, house), verbs (sleep, run), adverbs (slowly, quickly) and adjectives (small, large). The main stress in these words get the the emphasis, or stress, in a sentence:

I’m SORry. The CLASS is FULL.

LIons and TIgers and BEARS, oh MY.

Try saying the sentences above out loud, putting a stronger stress on the capitalized parts. You can even drum the beat on a table, hitting harder as you say the stressed words.

In this video, Tom Hanks, an American movie actor, performs slam poetry about the classic television series “Full House.” You can really hear the emphasis on the content words.

There are other words that can be content words, depending on the meaning. These include the following: Wh-words (who, what, where and why), interjections (Yes, ahh, dear me) and negatives (can’t, won’t). For example:

NO, you CAN’T come.

WHAT are you SAYing?

Structure words

Structure words are the “soft” beats with less meaning in the sentence. They provide the grammatical elements of the sentence and are said with a quieter beat. Structure words are articles (a, an), prepositions (in, on), conjunctions (but, and), pronouns (I, you) and auxiliary verbs (is, was).

For example, the words “I,” “the” and “is” in the following example are structure words:

I KNOW. The STORE is FULL.

If you give a strong beat to the wrong word or even the wrong syllable, you can change the meaning or make the sentence hard to understand. “You enjoy HIStory,” can sound like “You enjoy his STOry.”

Here’s a video from Rachel’s English going over content and structure word stress in action.

Focus Words in Sentence Stress

You now know about the strong and soft beats that make up the music of the English language. In every sentence or phrase, there’s one word that has the main emphasis or focus. The loudest part is the strong syllable of the focus word.

Focus words help your listener understand the main point of what you’re trying to convey. It can provide essential or new information. It can contrast ideas or even make a correction.

Many times, the focus word is the last content word in the phrase or sentence:

Taylor Swift is AMAzing!

Sometimes, though, you might move the focus word to change the meaning of your sentence. For example. if someone asks you what you plan to do next year, you might answer:

I’m going to COLlege.

The focus is the answer to the question: College is where you’ll be going.

On the other hand, if someone misheard that your sister is going to college, you might respond:

I’M going to college.

In this case, the focus is on the fact that it’s you (and not your sister) who’s going to college.

Pitch changes in focus words

Along with placing a stronger stress on the focus word, you’ll also need to raise the pitch—that is, make the sound of your voice higher.

To understand this better, St. George International has a great video that shows how stress and pitch placed on different words in the same sentence can completely change the meaning of the sentence.

Understanding the pitch change can also help improve your listening comprehension skills. When you hear the pitch change, you know what’s coming is critical. For those taking the TOEFL or IELTS listening test, practicing listening for the pitch change can improve your score.

Jill Diamond offers up some quick tips on how to identify the focus words in her online videos.

If you want more help on the topic, English with Lucy is super popular for a reason: She has lots of useful videos on English pronunciation.

Thought Groups

If you’re going to practice sentence stress, you have to also understand thought groups. Thought groups are phrases or sentences that express your “thought” by using natural pausing and a focus word.

In writing, we use punctuation (periods, commas, question marks) to show the natural pause.

Roses are red, violets are blue. (The comma shows the natural pause.)

In speech, you do this by adding a slight or quick pause before going to the next thought group. If you don’t pause, the sentences stream together, making your ideas unclear or completely wrong.

Let’s eat GRANDma!

Let’s EAT, GRANDma!

In the first example above, you’re telling the listener you want to eat Grandma. And in the second, you’re telling Grandma that it’s time to eat. Both mean very different things, shown through a correctly emphasized and paused thought group.

Not only do you pause at the end of a thought group, but you also use pitch and intonation—or the rise and fall of our voice—to signal the pause.

I love eating ↗GRANDpa. I love ↗EATing,↘ ↗GRANDdpa!

You can hear this in action with this silly animation from Justin Franko.

You can also have more than one thought group within a sentence. And within each thought group, you have a focus word:

It’s better to be SAFE than SORry.

Where there’s a WILL, there’s a WAY.

You can think of it like you’re “chunking” the language. Pronunciation Pro has some “chunking videos” that break down intonation and pausing.

Gabby Wallace from Go Natural English has some dynamic English pronunciation videos on thought groups that help you chunk like a native speaker.

Sources to Master Sentence Stress

Learning about sentence stress isn’t enough! These resources help you hear and practice the music of the language:

- “Well Said”: If you want to buy a pronunciation textbook, it should be the “Well Said” series by Linda Grant and Eve Einselen Yu. The books have fun activities that focus on all the important features of English pronunciation, including sentence stress.

The series goes over the latest research in pronunciation, TOEFL iBT preparation exercises and a full audio program.

- FluentU: This website and app lets you learn with short English videos featuring native speakers. With the help of the “loop-back” rewind feature, you can listen to clip sections over again and imitate what’s being said. All the videos come with transcripts and interactive subtitles that allow you to follow along and learn vocabulary.

After watching, you can test out your writing, speaking and listening skills with personalized quizzes.

- English Club: This is a free website for English learners that covers the rhythm of sentence stress. You can listen and practice with included bite-sized chunks of dialogue or learn about sentence stress rules. English Club is an excellent place to start when first learning about the beat of sentence stress.

- Oxford Online English: If you love YouTube, then you’re going to love Oxford Online English. You can subscribe to their channel and watch and learn from pronunciation experts all about English sentence stress.

You’ll never become bored with a vast (large) selection of pronunciation videos, taught by certified teachers.

Sentence stress is all about hearing the beat and using the English rhythm correctly. It’s not about having a perfect accent, but rather about emphasizing the correct focus word by raising and lowering your pitch, and taking a pause when needed.

Mastering sentence stress is a small step you can take that’ll help you sound much more natural when speaking English!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Sentence stress, or prominence, is the emphasis that certain words have in utterances. There is a general tendency to place stress in the stronger syllables of content words (e.g. main verbs, nouns, adjectives) rather than on function words (e.g. auxiliary verbs, preposition, pronouns etc.).

Sentence stress results in a particular rhythm the English language having, where not all syllables receive the same emphasis. That is why we tend to refer to the English language as a stress-timed language rather than syllable-timed (i.e. a language where all syllables carry similar weight).

Take the sentence below as an example and try to say it in a natural rhythm:

I’ll go to the cinema next Friday.

You’ve probably emphasized some syllables more than others, and most likely placed greater emphasis on the stressed syllables of the content words, resulting in something like this:

I’ll GO to the CInema next FRIday.

An important implication of that is that, in order for the rhythm to be maintained, it is common for us to “under-pronounce” function words, using their weak forms (e.g. the preposition to is often pronounced /tʊ/ or /tə/, rather than the strong form /tu/ in this context).

Unlike word stress, which tends to be fixed, prominence can vary quite frequently depending on the intention of the speaker. Look at the examples below and say the sentences with emphasis on the highlighted syllables. Compare the emphasis given with their intention in brackets:

I’LL go to the cinema next Friday. (me, not John)

I’ll go to the CInema next Friday. (not to the theatre)

I’ll go to the cinema NEXT Friday. (not this Friday)

I’ll go to the cinema next FRIday. (not next Thursday)

Why should I teach sentence stress?

It might be a good idea to help students notice and practice sentence stress for two main reasons:

-

It may help them communicate better, using prominence to emphasize specific parts of the sentence, conveying the intended message more effectively.

-

Because they are more aware of how sentence stress is produced orally, learners may be better able to understand fast speech.

How can I include sentence stress in a lesson?

Sentence stress could be dealt with during clarification of language.

Let’s say you are helping students become more aware of how to use the present perfect to describe past experiences. After helping students notice the meaning of the structure, you can board a sample sentence and ask the group what syllables should receive more emphasis. It is also a good idea to provide visual reference by, for example, underlining the stronger syllables:

I’ve never been to China.

I’ve travelled to Poland twice this year.

If you want to spend more time helping learners notice how sentence stress is placed, you could carry out a discovery activity, using a scene from a film, course book audio or any other source of listening input. Take a look at the example below:

1) Ask students to look at the lyrics from the song Price Tag, by British singer Jessie J. For each line, they should underline the syllables that they expect to be stronger.

Seems like everybody’s got a price (3 syllables)

I wonder how they sleep at night (3 Syllables)

When the sale comes first (2 syllables)

And the truth comes second (2 syllables)

Just stop for a minute and smile (3 syllables)

Why is everybody so serious? (3 syllables)

Acting so damn mysterious? (3 syllables)

Got shades on your eyes (2 syllables)

And your heels so high (2 Syllables)

that you can’t even have a good time (3 syllables)

Source: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/jessiej/pricetag.html

2) Now students listen to the song and check whether their predictions were correct.

Answer Key:

Seems like everybody’s got a price (3 syllables)

I wonder how they sleep at night (3 Syllables)

When the sale comes first (2 syllables)

And the truth comes second (2 syllables)

Just stop for a minute and smile (3 syllables)

Why is everybody so serious? (3 syllables)

Acting so damn mysterious? (3 syllables)

Got your shades on your eyes (2 syllables)

And your heels so high (2 Syllables)

that you can’t even have a good time (3 syllables)

Source: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/jessiej/pricetag.html

3) Learners could practise by clapping or tapping their desks with a regular rhythm (or using an online metronome) and trying to say the lines in a way that each underlined syllable coincides with a clap or beat.

References:

Underhill, A. (1994) Sound foundations: learning and teaching pronunciation. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

Rubens Heredia is an Academic Coordinator, CELTA and ICELT tutors at Cultura Inglesa São Paulo and one of the co-founders of What is ELT?

What is sentence stress?

Sentence stress (also called prosodic stress) refers to the emphasis placed on certain words within a sentence. This varying emphasis gives English a cadence, resulting in a natural songlike quality when spoken fluently.

Sentence stress is generally determined by whether a word is considered a “content word” or a “function word,” and the vocal space between stressed words creates the rhythm of a sentence.

Content Words vs. Function Words

In the most basic pattern, content words will always be stressed, while function words will often be unstressed. Let’s briefly discuss the difference between the two.

Content words

A content word (also known as a lexical word) is a word that communicates a distinct lexical meaning within a particular context—that is, it expresses the specific content of what we’re talking about at a given time. Nouns (e.g., dog, Betty, happiness, luggage), most* verbs (e.g., run, talk, decide, entice), adjectives (e.g., sad, outrageous, good, easy), and adverbs (e.g., slowly, beautifully, never) all have meaning that is considered lexically important.

Content words will always have at least one syllable that is emphasized in a sentence, so if a content word only has a single syllable, it will always be stressed.

(*Auxiliary verbs are specific types of verbs that are used in the grammatical construction of tense and aspect or to express modality—that is, asserting or denying possibility, likelihood, ability, permission, obligation, or future intention. These types of verbs are fixed in their structure and are used to convey a relationship between other “main” verbs, so they are considered function words, which we’ll look at next.)

Function words

A function word (also known as a structure word) is a word that primarily serves to complete the syntax and grammatical nuance of a sentence. These include pronouns (e.g., he, she, it, they), prepositions (e.g., to, in, on, under), conjunctions (e.g., and, but, if, or), articles (e.g., a, an, the), other determiners (e.g., this, each, those), and interjections (e.g., ah, grr, hello).

In addition to these parts of speech, function words also include a specific subset of verbs known as auxiliary verbs, which add structural and grammatical meaning to other main verbs. These include the three primary auxiliary verbs be, do, and have, as well as a number of others known as modal auxiliary verbs, such as can, may, must, will, and others.

Finally, function words, especially those with only one syllable, are commonly (but not always) unstressed in a sentence—since they are not providing lexical meaning integral to the sentence, we often “skip over” them vocally. For example, in the sentence, “Bobby wants to walk to the playground,” the particle to, the preposition to, and the definite article the are all said without (or without much) stress. The content words (Bobby, wants, walk, and playground), on the other hand, each receive more emphasis to help them stand out and underline their importance to the meaning of the sentence.

Sentence Stress vs. Word Stress

While function words are often unstressed in a sentence, those that have more than one syllable still have internal word stress on one of their syllables. For example, the word because has two syllables (be·cause), with stress placed on the second syllable (/bɪˈkɔz/). However, in a sentence with a normal stress pattern, because will have less overall emphasis than the content words around it, which helps maintain the cadence and flow of the sentence in everyday speech.

Likewise, multi-syllable content words will have even more emphasis placed on the syllable that receives the primary stress. It is this syllable that is most articulated within a sentence, with the rest of the word being unstressed like the function words.

Examples of normal sentence stress

Let’s look at some examples, with function words in italics and the primary stress of content words in bold:

- “I have a favor to ask.”

- “Jonathan will be* late because his car broke down.”

- “I’m going to the store later.”

- “We do not agree with the outcome.”

- “Please don’t tell me how the movie ends.”

(*Note that be is technically a content word here—it is the main verb in the phrase will be late—but it remains unstressed like a function word. Because they are often used as auxiliary verbs to form verb tense, conjugations of be are almost always unstressed in sentences irrespective of their technical grammatical function.)

Rhythm

English is what’s known as a stress-timed language, which means that we leave approximately the same amount of time between stressed syllables in a sentence to create a natural cadence. These are sometimes referred to as the “beats” of a sentence.

This rhythm is easier to hear in sentences in which content words and function words alternate regularly, as in:

- “I have a favor to ask.”

Things become more complicated when a sentence has multiple content or function words in a row.

Generally speaking, when multiple function words appear together, we vocally condense them into a single beat, meaning that they are spoken slightly faster than content words on either side.

When multiple single-syllable content words appear together, the reverse effect occurs: a greater pause is given between each word to create natural beats while still maintaining the proper amount of emphasis. (Content words with more than one syllable are usually not affected, since at least one part of the word is unstressed.)

Let’s look at one of our previous examples to see this more clearly:

- “Jonathan will be late because his car broke down.”

After the first syllable of the content word Jonathan is stressed, the words will be and the last two syllables of Jonathan are all unstressed and spoken together quickly to form a beat before the next content word, late. The next two words, because his, are also unstressed and spoken quickly to form the next beat. The next three words, car broke down, are all content words, and they are each stressed separately. Because of this, we add a slight pause between them to help the rhythm of the sentence sound natural.

This rhythmic pattern between stressed and unstressed words occurs when a sentence is spoken “neutrally”—that is, without any additional emphasis added by the speaker. However, we can add extra stress to any word in a sentence in order to achieve a particular meaning. This is known as emphatic stress.

Emphatic Stress

The convention regarding the stress and rhythm of content words and function words is consistent in normal (sometimes called “neutral”) sentence stress. However, English speakers often place additional emphasis on a specific word or words to provide clarity, emphasis, or contrast; doing so lets the listener know more information than the words can provide on their own. Consider the following “neutral” sentence, with no stress highlighted at all:

- “Peter told John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.”

Now let’s look at the same sentence with emphatic stress applied to different words, and we’ll see how its implied meaning changes accordingly:

- “Peter told John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.” (Clarifies that Peter, as opposed to someone else, told John not to make the deal.)

- “Peter told John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.” (Emphasizes the fact that John had been told not to make the deal but did so anyway.)

- “Peter told John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.” (Clarifies that John was told not to make the deal, not someone else.)

- “Peter told John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.” (Emphasizes that Peter said the deal was not allowed, indicating that John thought or said the opposite.)

Representing emphatic stress in writing

In writing, we normally use the italic, underline, or bold typesets to represent this emphasis visually. Italics is more common in printed text, while underlining is more common in handwritten text.

Another quick way to indicate emphatic stress in writing is to put the emphasized word or words in capital letters, as in:

- “Peter TOLD John that a deal like this wasn’t allowed.”

This is much less formal, however, and is only appropriate in conversational writing.

What is Sentence Stress?

Words in a sentence are not all given the same salience in oral English. Some words are picked out and are stressed in contrast to others. The one that is the most stressed is said to receive the sentence stress. This usually implies differences in meaning. In the following sentences, the sentence stress is indicated in bold case. Consider the difference in meaning for each of these scenarios.

Sentence Stress Illustrated:

| Sentences | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1. I don’t think she would write it. | I don’t think that, but someone else does. |

| 2. I DON’T think she will listen to him. | It is not true that I think that. |

| 3. I don’t THINK she will listen to him. | I don’t think that, I know that. Or: I don’t think that, but I could be wrong. |

| 4. I don’t think SHE will listen to him. | I think that someone other than her will listen to him. |

| 5. I don’t think she WILL listen to him. | I think that she will not be willing or agreeable to listening to him. |

| 6. I don’t think she will LISTEN to him. | Instead of listening, she might talk to him. |

| 7. I don’t think she will listen to HIM. | I think that she will listen to someone else than him. |

Now listen to the sentences to hear the differences:

As you can see, the sentence stress depends a lot on the context. It is closely related to the meaning.

Sentence Stress Rule

Usually:

- Content words are stressed (words that still have some meaning if you put them out of context: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.)

- Grammatical words are not stressed (words that help structure a sentence in English but that do not really have some meaning if you put them out of context: a, an, the, is, etc.)

But, as in the examples above, even grammatical words can be stressed in some specific contexts.

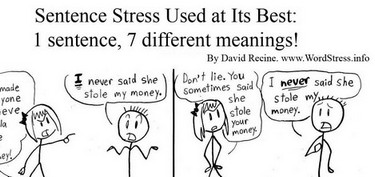

Sentence Stress Cartoon

Click here or on the image below to read a funny example of how sentence stress can be used to convey different meanings.

Sentence stress: 1 Sentence, 7 Different meanings. By David Recine.

Sentence Stress Exercise

Do this short exercise to check if you can recognize sentence stress!

This time I am going to draw your attention to some delicate item of the English language. To begin with, you’ve got to remember that each time you learn new vocabulary, it is important to make sure you

know the following:

• the meaning of the word you’re learning;

• collocation (which other words commonly go with it);

• “currency” — whether or not the word is restricted to certain situations or can be used widely;

• its spelling;

• and pronunciation.

Let’s take the word “ DESPERATE“.

|

Meaning |

— feeling that you have no hope and are ready to do anything to change the situation you are in (desperate with sth) ; — needing or wanting something very much (desperate for sth, desperate to do sth ); — a desperate situation is very bad or serious. |

|

Collocation |

desperate attempt/bid/effort; desperate battle/struggle/fight |

|

“Currency” |

quite frequently used (especially by pessimists) |

|

Spelling |

desperate (not disparate or whatever else) |

|

Pronunciation |

/ˈdes.pər.ət/ |

Although the last point is crucially important, very often it’s neglected by students and even by teachers. There are two interesting features of English pronunciation which give you the key to understanding and being understood and these are STRESS and INTONATION. Today we’ll start by considering WORD and SENTENCE STRESS (наголос).

English is considered a stressed language while many other languages are considered syllabic. What does that mean? It means that in English, certain words have stress within a sentence, and certain syllables have stress within a word. And it is this stress that allows our ears to understand the meaning and also to pick up the important parts of the sentence. We give stress to certain words while other words are quickly spoken (some students say eaten!). In other languages, such as French or Italian, each syllable receives equal importance (there is stress, but each syllable has its own length). English however, spends more time on specific stressed words while quickly gliding over the other, less important, words.

What is word stress?

In multi-syllable words (багатоскладових словах) the stress falls on one of the syllables while the other syllables tend to be spoken over quickly. For example, try saying the following words to yourself: qualify, banana, understand. All of them have 3 syllables and one of the syllables in each word will sound louder than the others: so, we get QUAlify, baNAna and underSTAND. (The syllables indicated in capitals are the stressed syllables). What makes a syllable stressed? It is usually higher in pitch (the level of the speaker’s voice). It’s pronounced louder. And finally, it’s longer in duration.

Stress can fall on the first, middle or last syllables of words, as is shown here:

|

Ooo |

oOo |

ooO |

|

SYLlabus |

enGAGEment |

usheRETTE |

|

SUBstitute |

baNAna |

kangaROO |

|

TECHnical |

phoNEtic |

underSTAND |

In order for one syllable to be perceived as stressed, the syllables around it need to be

unstressed.

Have another look at the groups of words in the table above. In the word SYLLABUS, we said the first syllable was stressed. This logically implies that the final two are unstressed. Also, in the word BANANA, the first and third syllables are unstressed, and the middle one is stressed. In order to improve your pronunciation, focus on pronouncing the stressed syllable clearly. However, don’t be afraid to «mute» (not say clearly) the other unstressed vowels.

But how do we recognize where the stress falls? Well, there are a couple of ideas:

1. Try putting this word in the end of a short sentence, and saying it over a few times: for example, It’s in the syllabus; He had a prior engagement; I don’t understand.

2. Try saying this word as though you have been completely taken by surprise: for example, SYLlabus? baNAna? kangaROO?

In dictionaries we spot the stress with help of a mark before the stressed syllable like in the following examples: /bəˈnɑː.nə/, /ɪnˈgeɪdʒ.mənt/, /ˌʌn.dəˈstænd/.

The table below is a kind of a ‘rough guide’ to stressed syllables. Though these are rather tendencies than rules, since they only tell us what is true most of the time, and it is always possible to find exceptions.

In longer words with many syllables, there can be a primary stress and a secondary stress. So the primary stress would be the highest in pitch and perhaps the longest, but there might also be another syllable that is important. For example, the word EMBARRASSMENT (ɪmˈbær.ə.smənt ).So there it is the last two syllables that are not stressed. And it is the second syllable that is stressed. But the first syllable is also somewhat important and higher in pitch than the last two. So, the first syllable there has a secondary stress, and the second syllable has the primary stress. The last two syllables are unstressed.

There are several ways of indicating stress when it comes to making notes as you are learning a new vocabulary item. And I strongly advise you to use one of them. For this, of course, you will need to consult your dictionary all the time.

What is sentence stress?

Sentence Stress is actually the “music” of English, the thing that gives the language its particular “beat” or “rhythm”. In general, in any given English sentence there will be particular words that carry more “weight” or “volume” (stress) than others. Believe me, we do convey a lot of meaning through how much stress we place in a sentence and which word the stress is on.

Consider the following example:

At the moment, nothing is particularly stressed. The meaning seems fairly obvious. But what if some stress is placed on the first word — I:

I did not say you stole my red hat.

Then the meaning contains the idea that someone else said it, not me. Stress the second and third word and you get another shade of meaning:

I did not say you stole my red hat. (Strong anger and denial of the fact.)

I did not say you stole my red hat.

I did not say you stole my red hat. (But I implied it that you did. Did you?)

I did not say you stole my red hat (I wasn’t accusing you. I know it was someone else)

I did not say you stole my red hat. (I said you did something else with it, or maybe borrowed it.)

I did not say you stole my red hat. (I meant that you stole someone else’s red hat)

I did not say you stole my red hat. (I said that you stole my blue hat.)

I did not say that you stole my red hat. (I said that you stole my red bat. You misunderstood my pronunciation)

Analyzing this way, you can see how important stress is in English. Now, you need to understand which words we generally stress and which we do not stress. Stressed words carry the meaning or the sense behind the sentence, and for this reason they are called content words – they carry the content of the sentence. The example below gives us three content words – LIVES, HOUSE and CORNER:

he LIVES in the HOUSE on the CORNER.

These three content words carry the most important ideas in the sentence. Unstressed words tend to be smaller words which we need in order to make our language hold together. They help the sentence “function” and for this reason they are called function words.

|

Content Words |

Function Words |

||

|

Main Verbs |

go, talk, writing |

Pronouns |

I, you, he ,they |

|

Nouns |

student, desk |

Prepositions |

on, under, with |

|

Adjectives |

big, clever |

Articles |

the, a, some |

|

Adverbs |

quickly, loudly |

Conjunctions |

but, and, so |

|

Negative Aux. Verbs |

can’t, don’t, aren’t |

Auxiliary Verbs |

can, should, must |

|

Demonstratives |

this, that, those |

Verb “to be” |

is, was, am |

|

Question Words |

who, which, where |

Now, say this sentence aloud and count how many seconds it takes:

The beautiful Mountain appeared transfixed in the distance.

Time required? Probably about 5 seconds. Now, try speaking this sentence aloud:

He can come on Sundays as long as he doesn’t have to do any homework in the evening.

Time required? Probably about 5 seconds. But the first sentence is much shorter than the second sentence?! How’s it possible? The thing is that Even though the second sentence is approximately 30% longer than the first, it has the same number of stressed words – 5. From this example, you can see that you needn’t worry about pronouncing every word clearly to be understood. You should however, concentrate on pronouncing the stressed words clearly.

You will soon find that you can understand and communicate more because you begin to listen for (and use in speaking) stressed words. All those words that you thought you didn’t understand are really not crucial for understanding the sense or making yourself understood. Stressed words are the key to excellent pronunciation and understanding of English. I hope this ode to the importance of stress in English will help you to improve your understanding and speaking skills :-).

Now watch the videos to review what we’ve learned this time:

Мы рассмотрели правила и примеры постановки ударений в английском языке. Чтобы узнать больше об английской грамматике, читайте другие публикации в разделе Grammar!

For other uses, see Stress.

| Primary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˈ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 501 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˈ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02C8 |

| Secondary stress | |

|---|---|

| ˌ◌ | |

| IPA Number | 502 |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | ˌ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+02CC |

In linguistics, and particularly phonology, stress or accent is the relative emphasis or prominence given to a certain syllable in a word or to a certain word in a phrase or sentence. That emphasis is typically caused by such properties as increased loudness and vowel length, full articulation of the vowel, and changes in tone.[1][2] The terms stress and accent are often used synonymously in that context but are sometimes distinguished. For example, when emphasis is produced through pitch alone, it is called pitch accent, and when produced through length alone, it is called quantitative accent.[3] When caused by a combination of various intensified properties, it is called stress accent or dynamic accent; English uses what is called variable stress accent.

Since stress can be realised through a wide range of phonetic properties, such as loudness, vowel length, and pitch (which are also used for other linguistic functions), it is difficult to define stress solely phonetically.

The stress placed on syllables within words is called word stress. Some languages have fixed stress, meaning that the stress on virtually any multisyllable word falls on a particular syllable, such as the penultimate (e.g. Polish) or the first (e.g. Finnish). Other languages, like English and Russian, have lexical stress, where the position of stress in a word is not predictable in that way but lexically encoded. Sometimes more than one level of stress, such as primary stress and secondary stress, may be identified.

Stress is not necessarily a feature of all languages: some, such as French and Mandarin, are sometimes analyzed as lacking lexical stress entirely.

The stress placed on words within sentences is called sentence stress or prosodic stress. That is one of the three components of prosody, along with rhythm and intonation. It includes phrasal stress (the default emphasis of certain words within phrases or clauses), and contrastive stress (used to highlight an item, a word or part of a word, that is given particular focus).

Phonetic realization[edit]

There are various ways in which stress manifests itself in the speech stream, and they depend to some extent on which language is being spoken. Stressed syllables are often louder than non-stressed syllables, and they may have a higher or lower pitch. They may also sometimes be pronounced longer. There are sometimes differences in place or manner of articulation. In particular, vowels in unstressed syllables may have a more central (or «neutral») articulation, and those in stressed syllables have a more peripheral articulation. Stress may be realized to varying degrees on different words in a sentence; sometimes, the difference is minimal between the acoustic signals of stressed and those of unstressed syllables.

Those particular distinguishing features of stress, or types of prominence in which particular features are dominant, are sometimes referred to as particular types of accent: dynamic accent in the case of loudness, pitch accent in the case of pitch (although that term usually has more specialized meanings), quantitative accent in the case of length,[3] and qualitative accent in the case of differences in articulation. They can be compared to the various types of accent in music theory. In some contexts, the term stress or stress accent specifically means dynamic accent (or as an antonym to pitch accent in its various meanings).

A prominent syllable or word is said to be accented or tonic; the latter term does not imply that it carries phonemic tone. Other syllables or words are said to be unaccented or atonic. Syllables are frequently said to be in pretonic or post-tonic position, and certain phonological rules apply specifically to such positions. For instance, in American English, /t/ and /d/ are flapped in post-tonic position.

In Mandarin Chinese, which is a tonal language, stressed syllables have been found to have tones that are realized with a relatively large swing in fundamental frequency, and unstressed syllables typically have smaller swings.[4] (See also Stress in Standard Chinese.)

Stressed syllables are often perceived as being more forceful than non-stressed syllables.

Word stress[edit]

Word stress, or sometimes lexical stress, is the stress placed on a given syllable in a word. The position of word stress in a word may depend on certain general rules applicable in the language or dialect in question, but in other languages, it must be learned for each word, as it is largely unpredictable. In some cases, classes of words in a language differ in their stress properties; for example, loanwords into a language with fixed stress may preserve stress placement from the source language, or the special pattern for Turkish placenames.

Non-phonemic stress[edit]

In some languages, the placement of stress can be determined by rules. It is thus not a phonemic property of the word, because it can always be predicted by applying the rules.

Languages in which the position of the stress can usually be predicted by a simple rule are said to have fixed stress. For example, in Czech, Finnish, Icelandic, Hungarian and Latvian, the stress almost always comes on the first syllable of a word. In Armenian the stress is on the last syllable of a word.[5] In Quechua, Esperanto, and Polish, the stress is almost always on the penult (second-last syllable). In Macedonian, it is on the antepenult (third-last syllable).

Other languages have stress placed on different syllables but in a predictable way, as in Classical Arabic and Latin, where stress is conditioned by the structure of particular syllables. They are said to have a regular stress rule.

Statements about the position of stress are sometimes affected by the fact that when a word is spoken in isolation, prosodic factors (see below) come into play, which do not apply when the word is spoken normally within a sentence. French words are sometimes said to be stressed on the final syllable, but that can be attributed to the prosodic stress that is placed on the last syllable (unless it is a schwa, when stress is placed on the second-last syllable) of any string of words in that language. Thus, it is on the last syllable of a word analyzed in isolation. The situation is similar in Standard Chinese. French (some authors add Chinese[6]) can be considered to have no real lexical stress.

Phonemic stress[edit]

With some exceptions above, languages such as Germanic languages, Romance languages, the East and South Slavic languages, Lithuanian, as well as others, in which the position of stress in a word is not fully predictable, are said to have phonemic stress. Stress in these languages is usually truly lexical and must be memorized as part of the pronunciation of an individual word. In some languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Lakota and, to some extent, Italian, stress is even represented in writing using diacritical marks, for example in the Spanish words célebre and celebré. Sometimes, stress is fixed for all forms of a particular word, or it can fall on different syllables in different inflections of the same word.

In such languages with phonemic stress, the position of stress can serve to distinguish otherwise identical words. For example, the English words insight () and incite () are distinguished in pronunciation only by the fact that the stress falls on the first syllable in the former and on the second syllable in the latter. Examples from other languages include German Tenor ([ˈteːnoːɐ̯] «gist of message» vs. [teˈnoːɐ̯] «tenor voice»); and Italian ancora ([ˈaŋkora] «anchor» vs. [aŋˈkoːra] «more, still, yet, again»).

In many languages with lexical stress, it is connected with alternations in vowels and/or consonants, which means that vowel quality differs by whether vowels are stressed or unstressed. There may also be limitations on certain phonemes in the language in which stress determines whether they are allowed to occur in a particular syllable or not. That is the case with most examples in English and occurs systematically in Russian, such as за́мок ([ˈzamək], «castle») vs. замо́к ([zɐˈmok], «lock»); and in Portuguese, such as the triplet sábia ([ˈsaβjɐ], «wise woman»), sabia ([sɐˈβiɐ], «knew»), sabiá ([sɐˈβja], «thrush»).

Dialects of the same language may have different stress placement. For instance, the English word laboratory is stressed on the second syllable in British English (labóratory often pronounced «labóratry», the second o being silent), but the first syllable in American English, with a secondary stress on the «tor» syllable (láboratory often pronounced «lábratory»). The Spanish word video is stressed on the first syllable in Spain (vídeo) but on the second syllable in the Americas (video). The Portuguese words for Madagascar and the continent Oceania are stressed on the third syllable in European Portuguese (Madagáscar and Oceânia), but on the fourth syllable in Brazilian Portuguese (Madagascar and Oceania).

Compounds[edit]

With very few exceptions, English compound words are stressed on their first component. Even the exceptions, such as mankínd,[7] are instead often stressed on the first component by some people or in some kinds of English.[8] The same components as those of a compound word are sometimes used in a descriptive phrase with a different meaning and with stress on both words, but that descriptive phrase is then not usually considered a compound: bláck bírd (any bird that is black) and bláckbird (a specific bird species) and páper bág (a bag made of paper) and páper bag (very rarely used for a bag for carrying newspapers but is often also used for a bag made of paper).[9]

Levels of stress[edit]

Some languages are described as having both primary stress and secondary stress. A syllable with secondary stress is stressed relative to unstressed syllables but not as strongly as a syllable with primary stress : for example, saloon and cartoon both have the main stress on the last syllable, but whereas cartoon also has a secondary stress on the first syllable, saloon does not. As with primary stress, the position of secondary stress may be more or less predictable depending on language. In English, it is not fully predictable, but the different secondary stress of the words organization and accumulation (on the first and second syllable, respectively) is predictable due to the same stress of the verbs órganize and accúmulate. In some analyses, for example the one found in Chomsky and Halle’s The Sound Pattern of English, English has been described as having four levels of stress: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary, but the treatments often disagree with one another.

Peter Ladefoged and other phoneticians have noted that it is possible to describe English with only one degree of stress, as long as prosody is recognized and unstressed syllables are phonemically distinguished for vowel reduction.[10] They find that the multiple levels posited for English, whether primary–secondary or primary–secondary–tertiary, are not phonetic stress (let alone phonemic), and that the supposed secondary/tertiary stress is not characterized by the increase in respiratory activity associated with primary/secondary stress in English and other languages. (For further detail see Stress and vowel reduction in English.)

Prosodic stress[edit]

| Extra stress |

|---|

| ˈˈ◌ |

Prosodic stress, or sentence stress, refers to stress patterns that apply at a higher level than the individual word – namely within a prosodic unit. It may involve a certain natural stress pattern characteristic of a given language, but may also involve the placing of emphasis on particular words because of their relative importance (contrastive stress).

An example of a natural prosodic stress pattern is that described for French above; stress is placed on the final syllable of a string of words (or if that is a schwa, the next-to-final syllable). A similar pattern is found in English (see § Levels of stress above): the traditional distinction between (lexical) primary and secondary stress is replaced partly by a prosodic rule stating that the final stressed syllable in a phrase is given additional stress. (A word spoken alone becomes such a phrase, hence such prosodic stress may appear to be lexical if the pronunciation of words is analyzed in a standalone context rather than within phrases.)

Another type of prosodic stress pattern is quantity sensitivity – in some languages additional stress tends to be placed on syllables that are longer (moraically heavy).

Prosodic stress is also often used pragmatically to emphasize (focus attention on) particular words or the ideas associated with them. Doing this can change or clarify the meaning of a sentence; for example:

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (Somebody else did.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did not take it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I did something else with it.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took one of several. or I didn’t take the specific test that would have been implied.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took something else.)

I didn’t take the test yesterday. (I took it some other day.)

As in the examples above, stress is normally transcribed as italics in printed text or underlining in handwriting.

In English, stress is most dramatically realized on focused or accented words. For instance, consider the dialogue

«Is it brunch tomorrow?»

«No, it’s dinner tomorrow.»

In it, the stress-related acoustic differences between the syllables of «tomorrow» would be small compared to the differences between the syllables of «dinner«, the emphasized word. In these emphasized words, stressed syllables such as «din» in «dinner» are louder and longer.[11][12][13] They may also have a different fundamental frequency, or other properties.

The main stress within a sentence, often found on the last stressed word, is called the nuclear stress.[14]

Stress and vowel reduction[edit]

In many languages, such as Russian and English, vowel reduction may occur when a vowel changes from a stressed to an unstressed position. In English, unstressed vowels may reduce to schwa-like vowels, though the details vary with dialect (see stress and vowel reduction in English). The effect may be dependent on lexical stress (for example, the unstressed first syllable of the word photographer contains a schwa , whereas the stressed first syllable of photograph does not /ˈfoʊtəˌgræf -grɑːf/), or on prosodic stress (for example, the word of is pronounced with a schwa when it is unstressed within a sentence, but not when it is stressed).

Many other languages, such as Finnish and the mainstream dialects of Spanish, do not have unstressed vowel reduction; in these languages vowels in unstressed syllables have nearly the same quality as those in stressed syllables.

Stress and rhythm[edit]

Some languages, such as English, are said to be stress-timed languages; that is, stressed syllables appear at a roughly constant rate and non-stressed syllables are shortened to accommodate that, which contrasts with languages that have syllable timing (e.g. Spanish) or mora timing (e.g. Japanese), whose syllables or moras are spoken at a roughly constant rate regardless of stress. For details, see isochrony.

Historical effects[edit]

It is common for stressed and unstressed syllables to behave differently as a language evolves. For example, in the Romance languages, the original Latin short vowels /e/ and /o/ have often become diphthongs when stressed. Since stress takes part in verb conjugation, that has produced verbs with vowel alternation in the Romance languages. For example, the Spanish verb volver (to return, come back) has the form volví in the past tense but vuelvo in the present tense (see Spanish irregular verbs). Italian shows the same phenomenon but with /o/ alternating with /uo/ instead. That behavior is not confined to verbs; note for example Spanish viento «wind» from Latin ventum, or Italian fuoco «fire» from Latin focum. There are also examples in French, though they are less systematic : viens from Latin venio where the first syllabe was stressed, vs venir from Latin venire where the main stress was on the penultimate syllable.

Stress «deafness»[edit]

An operational definition of word stress may be provided by the stress «deafness» paradigm.[15][16] The idea is that if listeners perform poorly on reproducing the presentation order of series of stimuli that minimally differ in the position of phonetic prominence (e.g. [númi]/[numí]), the language does not have word stress. The task involves a reproduction of the order of stimuli as a sequence of key strokes, whereby key «1» is associated with one stress location (e.g. [númi]) and key «2» with the other (e.g. [numí]). A trial may be from 2 to 6 stimuli in length. Thus, the order [númi-númi-numí-númi] is to be reproduced as «1121». It was found that listeners whose native language was French performed significantly worse than Spanish listeners in reproducing the stress patterns by key strokes. The explanation is that Spanish has lexically contrastive stress, as evidenced by the minimal pairs like tópo («mole») and topó («[he/she/it] met»), while in French, stress does not convey lexical information and there is no equivalent of stress minimal pairs as in Spanish.

An important case of stress «deafness» relates to Persian.[16] The language has generally been described as having contrastive word stress or accent as evidenced by numerous stem and stem-clitic minimal pairs such as /mɒhi/ [mɒ.hí] («fish») and /mɒh-i/ [mɒ́.hi] («some month»). The authors argue that the reason that Persian listeners are stress «deaf» is that their accent locations arise postlexically. Persian thus lacks stress in the strict sense.

Stress «deafness» has been studied for a number of languages, such as Polish[17] or French learners of Spanish.[18]

Spelling and notation for stress[edit]

The orthographies of some languages include devices for indicating the position of lexical stress. Some examples are listed below:

- In Modern Greek, all polysyllables are written with an acute accent (´) over the vowel of the stressed syllable. (The acute accent is also used on some monosyllables in order to distinguish homographs, as in η (‘the’) and ή (‘or’); here the stress of the two words is the same.)

- In Spanish orthography, stress may be written explicitly with a single acute accent on a vowel. Stressed antepenultimate syllables are always written with that accent mark, as in árabe. If the last syllable is stressed, the accent mark is used if the word ends in the letters n, s, or a vowel, as in está. If the penultimate syllable is stressed, the accent is used if the word ends in any other letter, as in cárcel. That is, if a word is written without an accent mark, the stress is on the penult if the last letter is a vowel, n, or s, but on the final syllable if the word ends in any other letter. However, as in Greek, the acute accent is also used for some words to distinguish various syntactical uses (e.g. té ‘tea’ vs. te a form of the pronoun tú ‘you’; dónde ‘where’ as a pronoun or wh-complement, donde ‘where’ as an adverb). For more information, see Stress in Spanish.

- In Portuguese, stress is sometimes indicated explicitly with an acute accent (for i, u, and open a, e, o), or circumflex (for close a, e, o). The orthography has an extensive set of rules that describe the placement of diacritics, based on the position of the stressed syllable and the surrounding letters.

- In Italian, the grave accent is needed in words ending with an accented vowel, e.g. città, ‘city’, and in some monosyllabic words that might otherwise be confused with other words, like là (‘there’) and la (‘the’). It is optional for it to be written on any vowel if there is a possibility of misunderstanding, such as condomìni (‘condominiums’) and condòmini (‘joint owners’). See Italian alphabet § Diacritics. (In this particular case, a frequent one in which diacritics present themselves, the difference of accents is caused by the fall of the second «i» from Latin in Italian, typical of the genitive, in the first noun (con/domìnìi/, meaning «of the owner»); while the second was derived from the nominative (con/dòmini/, meaning simply «owners»).

Though not part of normal orthography, a number of devices exist that are used by linguists and others to indicate the position of stress (and syllabification in some cases) when it is desirable to do so. Some of these are listed here.

- Most commonly, the stress mark is placed before the beginning of the stressed syllable, where a syllable is definable. However, it is occasionally placed immediately before the vowel.[19] In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), primary stress is indicated by a high vertical line (primary stress mark:

ˈ) before the stressed element, secondary stress by a low vertical line (secondary stress mark:ˌ). For example, [sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən] or /sɪˌlæbəfɪˈkeɪʃən/. Extra stress can be indicated by doubling the symbol: ˈˈ◌. - Linguists frequently mark primary stress with an acute accent over the vowel, and secondary stress by a grave accent. Example: [sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən] or /sɪlæ̀bəfɪkéɪʃən/. That has the advantage of not requiring a decision about syllable boundaries.

- In English dictionaries that show pronunciation by respelling, stress is typically marked with a prime mark placed after the stressed syllable: /si-lab′-ə-fi-kay′-shən/.

- In ad hoc pronunciation guides, stress is often indicated using a combination of bold text and capital letters. For example, si-lab-if-i-KAY-shun or si-LAB-if-i-KAY-shun

- In Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian dictionaries, stress is indicated with marks called znaki udareniya (знаки ударения, ‘stress marks’). Primary stress is indicated with an acute accent (´) on a syllable’s vowel (example: вимовля́ння).[20][21] Secondary stress may be unmarked or marked with a grave accent: о̀колозе́мный. If the acute accent sign is unavailable for technical reasons, stress can be marked by making the vowel capitalized or italic.[22] In general texts, stress marks are rare, typically used either when required for disambiguation of homographs (compare в больши́х количествах ‘in great quantities’, and в бо́льших количествах ‘in greater quantities’), or in rare words and names that are likely to be mispronounced. Materials for foreign learners may have stress marks throughout the text.[20]

- In Dutch, ad hoc indication of stress is usually marked by an acute accent on the vowel (or, in the case of a diphthong or double vowel, the first two vowels) of the stressed syllable. Compare achterúítgang (‘deterioration’) and áchteruitgang (‘rear exit’).

- In Biblical Hebrew, a complex system of cantillation marks is used to mark stress, as well as verse syntax and the melody according to which the verse is chanted in ceremonial Bible reading. In Modern Hebrew, there is no standardized way to mark the stress. Most often, the cantillation mark oleh (part of oleh ve-yored), which looks like a left-pointing arrow above the consonant of the stressed syllable, for example ב֫וקר bóqer (‘morning’) as opposed to בוק֫ר boqér (‘cowboy’). That mark is usually used in books by the Academy of the Hebrew Language and is available on the standard Hebrew keyboard at AltGr-6. In some books, other marks, such as meteg, are used.[23]

See also[edit]

- Accent (poetry)

- Accent (music)

- Foot (prosody)

- Initial-stress-derived noun

- Pitch accent (intonation)

- Rhythm

- Syllable weight

References[edit]

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1955). «Duration and intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stress». Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 27 (4): 765–768. Bibcode:1955ASAJ…27..765F. doi:10.1121/1.1908022.

- ^ Fry, D.B. (1958). «Experiments in the perception of stress». Language and Speech. 1 (2): 126–152. doi:10.1177/002383095800100207. S2CID 141158933.

- ^ a b Monrad-Krohn, G. H. (1947). «The prosodic quality of speech and its disorders (a brief survey from a neurologist’s point of view)». Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 22 (3–4): 255–269. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1947.tb08246.x. S2CID 146712090.

- ^ Kochanski, Greg; Shih, Chilin; Jing, Hongyan (2003). «Quantitative measurement of prosodic strength in Mandarin». Speech Communication. 41 (4): 625–645. doi:10.1016/S0167-6393(03)00100-6.

- ^ Mirakyan, Norayr (2016). «The Implications of Prosodic Differences Between English and Armenian» (PDF). Collection of Scientific Articles of YSU SSS. YSU Press. 1.3 (13): 91–96.

- ^ San Duanmu (2000). The Phonology of Standard Chinese. Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- ^ mankind in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Publishers, HarperCollins. «The American Heritage Dictionary entry: mankind». www.ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ «paper bag» in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ Ladefoged (1975 etc.) A course in phonetics § 5.4; (1980) Preliminaries to linguistic phonetics p 83

- ^ Beckman, Mary E. (1986). Stress and Non-Stress Accent. Dordrecht: Foris. ISBN 90-6765-243-1.

- ^ R. Silipo and S. Greenberg, Automatic Transcription of Prosodic Stress for Spontaneous English Discourse, Proceedings of the XIVth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS99), San Francisco, CA, August 1999, pages 2351–2354

- ^ Kochanski, G.; Grabe, E.; Coleman, J.; Rosner, B. (2005). «Loudness predicts prominence: Fundamental frequency lends little». The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 118 (2): 1038–1054. Bibcode:2005ASAJ..118.1038K. doi:10.1121/1.1923349. PMID 16158659. S2CID 405045.

- ^ Roca, Iggy (1992). Thematic Structure: Its Role in Grammar. Walter de Gruyter. p. 80.

- ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Peperkamp, Sharon; Sebastián-Gallés, Núria (2001). «A robust method to study stress «deafness»«. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 110 (3): 1606–1618. Bibcode:2001ASAJ..110.1606D. doi:10.1121/1.1380437. PMID 11572370.

- ^ a b Rahmani, Hamed; Rietveld, Toni; Gussenhoven, Carlos (2015-12-07). «Stress «Deafness» Reveals Absence of Lexical Marking of Stress or Tone in the Adult Grammar». PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0143968. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043968R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143968. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4671725. PMID 26642328.

- ^ 3:439, 2012, 1-15., Ulrike; Knaus, Johannes; Orzechowska, Paula; Wiese, Richard (2012). «Stress ‘deafness’ in a language with fixed word stress: an ERP study on Polish». Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 439. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00439. PMC 3485581. PMID 23125839.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dupoux, Emmanuel; Sebastián-Gallés, N; Navarrete, E; Peperkamp, Sharon (2008). «Persistent stress ‘deafness’: The case of French learners of Spanish». Cognition. 106 (2): 682–706. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.04.001. hdl:11577/2714082. PMID 17592731. S2CID 2632741.

- ^ Payne, Elinor M. (2005). «Phonetic variation in Italian consonant gemination». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 153–181. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002240. S2CID 144935892.

- ^ a b Лопатин, Владимир Владимирович, ed. (2009). § 116. Знак ударения. Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник (in Russian). Эксмо. ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5.

- ^ Some pre-revolutionary dictionaries, e.g. Dahl’s Explanatory Dictionary, marked stress with an apostrophe just after the vowel (example: гла’сная). See: Dahl, Vladimir Ivanovich (1903). Boduen de Kurtene, Ivan Aleksandrovich (ed.). Толко́вый слова́рь живо́го великору́сского языка́ [Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). Saint Petersburg: M.O. Wolf. p. 4.

- ^ Каплунов, Денис (2015). Бизнес-копирайтинг: Как писать серьезные тексты для серьезных людей (in Russian). p. 389. ISBN 978-5-000-57471-3.

- ^ Aharoni, Amir (2020-12-02). «אז איך נציין את מקום הטעם». הזירה הלשונית – רוביק רוזנטל. Retrieved 2021-11-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links[edit]

- «Feet and Metrical Stress», The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

- «Word stress in English: Six Basic Rules», Linguapress

- Word Stress Rules: A Guide to Word and Sentence Stress Rules for English Learners and Teachers, based on affixation

When a little stress is a good thing…

How do students of English learn to speak like native speakers? Everyone knows that pronunciation is important, but some people forget about sentence stress and intonation. The cadence and rhythm of a language are important for fluency and clarity. Languages of the world vary greatly in word and sentence stress—many languages stress content words (e.g., most European languages) while others are tonal (e.g., Thai) or have little to no word stress (e.g., Japanese). Practicing sentence stress in English helps students speak more quickly and naturally. Fortunately for teachers, students usually enjoy activities like the one in the worksheet below! After one of our subscribers asked us for resources on sentence stress this week, I thought I’d share some tips and a worksheet that you can use in class.

Sentence stress occurs when we say certain words more loudly and with more emphasis than others. In English, we stress content words because they are essential to the meaning of the sentence. In general, shorter words or words that are clear from the context don’t get stressed.

Content words include nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Negative words such as not or never also get stressed because they affect the meaning of the sentence. Modals, too, can change the meaning of a sentence. Here is a list of words to stress in an English sentence:

- nouns (people, places, things)

- verbs (actions, states)

- adjectives (words that modify nouns)

- adverbs (words that modify verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or entire sentences)

- negative words (not, never, neither, etc.)

- modals (should, could, might, etc., but not will or can)

- yes, no, and auxiliary verbs in short answers (e.g., Yes, she does.)

- quantifiers (some, many, no, all, one, two, three, etc.)

- Wh-Question words (what, where, when, why, how, etc.—note that what is often unstressed when speaking quickly because it’s so common)

Not to Stress

Some words don’t carry a lot of importance in an English sentence. Short words such as articles, prepositions, and conjunctions don’t take stress. Pronouns don’t usually get stressed either because the context often makes it clear who we’re talking about. The Be verb and all auxiliary verbs don’t carry much meaning—only the main verb does. Here is a list of words that shouldn’t be stressed in an English sentence:

- articles (a, an, the)

- prepositions (to, in, at, on, for, from, etc.)

- conjunctions (and, or, so, but, etc.)

- personal pronouns (I, you, he, she, etc.)

- possessive adjectives (my, your, his, her, etc.)

- Be verb (am, is, are, was, were, etc.)

- auxiliary verbs (be, have, do in two-part verbs or questions)

- the modals will and be going to (because they’re common, and the future tense is often clear from context)

- the modal can (because it’s so common)

Examples

Model the following examples for your students and have them repeat after you. The words (or syllables when the word has more than one) that should be stressed are in bold.

- The kids are at the park.

- Do you have any brothers or sisters?

- Why aren’t you doing your homework?

- He bought a red car for his daughter.

- I am Brazilian.