Standard word order in English declarative sentences is first the subject, then the verb. (See Basic Word Order in the section Grammar.) For example:

Lena went to the park yesterday.

I am reading a book now.

This story is rather long.

She has found her keys.

Changing standard word order is called «inversion» (inverted word order; inverse word order). Inversion in English usually refers to placing the auxiliary, modal, or main verb before the subject. Inversion is used with a certain aim, often for emphasis. For example:

Never before have I seen such beauty.

There may be another problem.

Away ran the witch and the monster.

The words «standard word order; normal word order; ordinary word order» (that is, first the subject, then the verb) do not mean that inverted word order (that is, first the verb, then the subject) is incorrect or abnormal.

Standard word order and inverted word order have different uses. For example, inverted word order is necessary in questions, which means that inverted word order is normal word order for questions.

Note:

It is advisable for language learners to avoid using most of the emphatic inverted constructions described below. It is necessary to understand inversion, but it is better to use standard, ordinary word order in your own speech and writing.

Cases of inversion that you really need to use in your speech include questions, the construction «there is, there are», sentences beginning with «here» or «there», and responses like «So do I; Neither do I». Examples of other inverted constructions are given here in two variants for comparison of inverted and standard word order.

Note that English inversion may not always be reflected in Russian translation.

Typical cases of inversion

Inversion in questions

The most common type of inversion in English consists in moving the auxiliary verb into the position before the subject. This type of inversion is most often used in questions. For example:

Did Lena go to the park yesterday?

Has she found her keys?

Will he come to the party?

Is this story long?

How long is this story?

(For more examples of questions, see Word Order in Questions in the section Grammar.)

Construction «there is, there are»

Inversion is required in the construction «there is, there are» and in cases where a modal verb or a main verb is used in such constructions.

There is an interesting article about Spain in today’s paper.

There are several books on the table.

There must be a reason for it.

There can be no doubt about it.

There exist several theories on this matter.

Once upon a time, there lived an old man in a small house by the sea.

Inversion after «here» and «there»

Inversion takes place in sentences beginning with the adverb «here» or «there». Some phrases beginning with «here» or «there» have idiomatic character.

Here is the book you asked for.

Here comes the sun.

Here comes my bus.

Here comes your friend.

There is my sister!

There goes the bell.

There goes my money!

If the subject of the sentence beginning with «here» or «there» is expressed by a personal pronoun, the verb is placed after the subject.

Here it is. Here you are. Here you go.

There you are. There you go.

Here he comes. There he goes.

Here I am. There she is.

Here we go again.

Constructions with «so» and «neither»

Inversion is required in responses like «So do I» and «Neither do I». (See So do I. Neither do I. in the section Phrases.)

I like coffee. – So do I.

I don’t like coffee. – Neither do I.

She will wait for them. – So will I.

She won’t wait for them. – Neither will I.

Inversion is also required in compound sentences with such constructions.

I like coffee, and so does Ella.

I don’t like coffee, and neither does Ella.

She will wait for them, and so will I.

She won’t wait for them, and neither will I.

Conditional sentences

Inversion is required in the subordinate clause of conditional sentences in which the subordinating conjunction «if» is omitted. If the conjunction «if» is used, inversion is not used. Compare these conditional sentences in which inverted word order and standard word order are used.

Should my son call, ask him to wait for me at home. – If my son should call, ask him to wait for me at home. If my son calls, ask him to wait for me at home.

Were I not so tired, I would go there with you. – If I weren’t so tired, I would go there with you.

Had I known it, I would have helped him. – If I had known it, I would have helped him.

(See «Absence of IF» in Conditional Sentences in the section Grammar.)

Inversion after direct speech

Inversion takes place in constructions with verbs like «said, asked, replied» placed after direct speech.

«I’ll help you,» said Anton.

«What’s the problem?» asked the driver.

«I lost my purse,» replied the woman.

If the subject of such constructions is expressed by a personal pronoun, the verb is usually placed after the subject.

«Thank you for your help,» she said.

«Don’t mention it,» he answered.

Note: Many examples of inverted constructions like «said he; said she; said I» (used interchangeably with «he said; she said; I said» after direct speech) can be found in literary works of the past centuries. For example: ‘I am not afraid of you,’ said he, smilingly. (Jane Austen) ‘Where is the Prince?’ said he. (Charles Dickens) «That’s a fire,» said I. (Mark Twain)

If verbs like «said, asked, replied» are used in compound tense forms, or if there is a direct object after «ask», inversion is not used. For example: «I’ll help you,» Anton will say. «What’s the problem?» the driver asked her.

Standard word order is also used in constructions with verbs like «said, asked, replied» placed after direct speech, especially in American English. For example: «I’ll help you,» Anton said. «What’s the problem?» the driver asked.

If verbs like «said, asked, replied» stand before direct speech, inversion is not used. For example: Nina said, «Let’s go home.»

Inversion in exclamatory sentences

Inversion is sometimes used for emphasis in exclamatory sentences. Compare inverted and standard word order in the following exclamatory sentences.

Oh my, am I hungry! – I’m so hungry!

Oh boy, was she mad! – She was so mad!

Have we got a surprise for you! – We’ve got a surprise for you!

May all your wishes come true!

How beautiful are these roses! – How beautiful these roses are!

Inversion depending on the beginning of the sentence

The following cases of inversion occur when some parts of the sentence, for example, the adverbial modifier of place or direction, come at the beginning of the sentence. Inversion in such cases consists in moving the auxiliary verb, and in some cases the main verb (i.e., the whole tense form), into the position before the subject.

Such types of inversion are used for emphasis, mostly in literary works. It is advisable for language learners to use standard word order in such cases. The examples below are given in pairs: Inverted word order – Standard word order.

Inversion after «so», «such», «as»

So unhappy did the boy look that we gave him all the sweets that we had. – The boy looked so unhappy that we gave him all the sweets that we had.

Such was her disappointment that she started to cry. – Her disappointment was so strong that she started to cry.

Owls live in tree hollows, as do squirrels. – Owls and squirrels live in tree hollows.

As was the custom, three fighters and three shooters were chosen.

Inversion after adjectives and participles

Gone are the days when he was young and full of energy. – The days when he was young and full of energy are gone.

Blessed are the pure in heart.

Beautiful was her singing. – Her singing was beautiful.

Inversion after adverbial modifiers of place

Right in front of him stood a huge two-headed dragon. – A huge two-headed dragon stood right in front of him.

In the middle of the road was sitting a strange old man dressed in black. – A strange old man dressed in black was sitting in the middle of the road.

Behind the mountain lay the most beautiful valley that he had ever seen. – The most beautiful valley that he had ever seen lay behind the mountain.

Inversion after postpositions

The doors opened, and out ran several people. – Several people ran out when the doors opened.

Up went hundreds of toy balloons. – Hundreds of toy balloons went up.

If the subject is expressed by a personal pronoun, the verb is placed after the subject.

Are you ready? Off we go!

Out he ran. – He ran out.

Note: Direct object at the beginning of the sentence

Direct object is sometimes placed at the beginning of the sentence for emphasis. In such cases, the subject usually stands after the object, and the predicate follows the subject; that is, inverted word order is generally not used if the object is moved. Compare:

That we don’t know. – We don’t know that.

Those people I can ask. – I can ask those people.

Red dresses Lena doesn’t like. – Lena doesn’t like red dresses.

Inversion in negative constructions

Inversion is required in negative sentences beginning with the following negative adverbs and adverbial phrases: never; never before; not only…but also; not until; no sooner; at no time; on no account; under no circumstances.

Inversion also takes place in sentences beginning with the following adverbs and adverbial phrases used in a negative sense: rarely; seldom; hardly; scarcely; little; only when; only after; only then.

Inverted negative constructions are used for emphasis, mostly in formal writing and in literary works.

If you don’t need or don’t want to use emphatic inverted negative constructions, don’t put the above-mentioned expressions at the beginning of the sentence.

Compare the following examples of inverted and standard word order in sentences with such negative constructions. The first sentence in each group has inverted order of words.

Examples:

Never before have I felt such fear. – I have never felt such fear before.

Never in his life had he seen a more repulsive creature. – He had never in his life seen a more repulsive creature.

Not only did he spill coffee everywhere, but he also broke my favorite vase. – He not only spilled coffee everywhere but also broke my favorite vase.

Not only was the princess strikingly beautiful, but she was also extremely intelligent. – The princess was not only strikingly beautiful but also extremely intelligent.

Not until much later did I understand the significance of that event. – I understood the significance of that event much later.

No sooner had she put down the phone than it started to ring again. – As soon as she put down the phone, it started to ring again. The phone started to ring again as soon as she put down the receiver.

At no time should you let him out of your sight. – You should not let him out of your sight at any time. Don’t let him out of your sight even for a second.

Under no circumstances can she be held responsible for his actions. – She cannot be held responsible for his actions.

Rarely have I seen such a magnificent view. – I have rarely seen such a magnificent view.

Seldom do we realize what our actions might lead to. – We seldom realize what our actions might lead to.

Little did he know what his fate had in store for him. – He did not know what his fate had in store for him.

Hardly had I stepped into the house when the light went out. – I had hardly stepped into the house when the light went out.

Scarcely had he said it when the magician appeared. – He had scarcely said it when the magician appeared.

Only when I arrived at the hotel did I notice that my travel bag was missing. – I noticed that my travel bag was missing only when I arrived at the hotel.

Only after my guest left did I remember his name. – I remembered my guest’s name only after he left.

Инверсия

Стандартный порядок слов в английских повествовательных предложениях – сначала подлежащее, затем глагол. (См. «Basic Word Order» в разделе Grammar.) Например:

Лена ходила в парк вчера.

Я читаю книгу сейчас.

Этот рассказ довольно длинный.

Она нашла свои ключи.

Изменение стандартного порядка слов называется «инверсия» (обратный порядок слов). Инверсия в английском языке обычно имеет в виду помещение вспомогательного, модального или основного глагола перед подлежащим. Инверсия используется с определённой целью, часто для эмфатического усиления. Например:

Никогда раньше не видел я такой красоты.

Может быть и другая проблема.

Прочь убежали ведьма и чудовище.

Слова «стандартный порядок слов; нормальный порядок слов; обычный порядок слов» (то есть сначала подлежащее, затем глагол) не значат, что обратный порядок слов (то есть сначала глагол, затем подлежащее) является неправильным или ненормальным.

Стандартный порядок слов и обратный порядок слов имеют разное применение. Например, обратный порядок слов необходим в вопросах, что значит, что обратный порядок слов – это нормальный порядок слов для вопросов.

Примечание:

Изучающим язык целесообразно избегать употребления большинства описанных ниже эмфатических конструкций с обратным порядком слов. Необходимо понимать инверсию, но в своей устной и письменной речи лучше использовать стандартный, обычный порядок слов.

Случаи инверсии, которые вам действительно нужно использовать в вашей речи, включают вопросы, конструкцию «there is, there are», предложения, начинающиеся с «here» или «there», и фразы-отклики типа «So do I; Neither do I». Примеры других конструкций с обратным порядком слов даются здесь в двух вариантах для сравнения обратного и стандартного порядка слов.

Обратите внимание, что английская инверсия не всегда может быть отражена в русском переводе.

Типичные случаи инверсии

Инверсия в вопросах

Наиболее распространённый тип инверсии в английском языке заключается в перемещении вспомогательного глагола в положение перед подлежащим. Этот тип инверсии чаще всего используется в вопросах. Например:

Лена ходила в парк вчера?

Она нашла свои ключи?

Он придёт на вечеринку?

Этот рассказ длинный?

Какой длины этот рассказ?

(Ещё примеры вопросов можно посмотреть в статье «Word Order in Questions» в разделе Grammar.)

Конструкция «there is, there are»

Инверсия требуется в конструкции «there is, there are», а также в случаях, где модальный глагол или основной глагол употреблён в таких конструкциях.

В сегодняшней газете есть интересная статья об Испании.

На столе несколько книг.

Для этого должна быть причина.

В этом не может быть сомнения.

Существует несколько теорий по этому вопросу.

Когда-то давным-давно, в маленьком доме у моря жил старик.

Инверсия после «here» и «there»

Инверсия имеет место в предложениях, начинающихся с наречия «here» или «there». Некоторые фразы, начинающиеся с «here» или «there», имеют идиоматический характер.

Вот книга, которую вы просили.

Вот восходит солнце.

Вот идёт мой автобус.

Вот идёт твой друг.

Вот (там) моя сестра! / Вон моя сестра!

А вот и звонок.

Вот и пропали мои денежки!

Если подлежащее предложения, начинающегося с «here» или «there», выражено личным местоимением, глагол ставится после подлежащего.

Вот оно. / Вот. / Вот, возьмите.

Вот оно. / Вот. / Вот, возьмите.

Вот и он. / Вот он идёт. Вон он идёт.

Вот и я. Вон она.

Ну вот, опять начинается.

Конструкции с «so» и «neither»

Обратный порядок слов требуется в откликах типа «So do I» и «Neither do I». (См. статью «So do I. Neither do I.» в разделе Phrases.)

Я люблю кофе. – Я тоже.

Я не люблю кофе. – Я тоже (не люблю).

Она подождёт их. – Я тоже.

Она не будет их ждать. – Я тоже (не буду).

Инверсия также требуется в сложносочинённых предложениях с такими конструкциями.

Я люблю кофе, и Элла тоже (любит).

Я не люблю кофе, и Элла тоже (не любит).

Она подождёт их, и я тоже (подожду).

Она не будет ждать их, и я тоже (не буду).

Условные предложения

Инверсия требуется в придаточном предложении условных предложений, в которых опущен подчинительный союз «if». Если союз «if» употреблён, инверсия не используется. Сравните эти условные предложения, в которых употреблены обратный порядок слов и стандартный порядок слов.

В случае, если позвонит мой сын, попросите его подождать меня дома. – Если позвонит мой сын, попросите его подождать меня дома. Если позвонит мой сын, попросите его подождать меня дома.

Будь я не таким уставшим, я пошёл бы туда с вами. – Если бы я не был таким уставшим, я пошёл бы туда с вами.

Знай я это (раньше), я бы помог ему. – Если бы я знал это (раньше), я бы помог ему.

(См. «Absence of IF» в статье «Conditional Sentences» в разделе Grammar.)

Инверсия после прямой речи

Инверсия имеет место в конструкциях с глаголами типа «said, asked, replied», стоящими после прямой речи.

«Я помогу вам», – сказал Антон.

«В чём проблема?» – спросил водитель.

«Я потеряла кошелёк», – ответила женщина.

Если подлежащее таких конструкций выражено личным местоимением, глагол обычно ставится после подлежащего.

«Спасибо за вашу помощь», – сказала она.

«Не стоит благодарности», – ответил он.

Примечание: Много примеров конструкций с обратным порядком слов типа «said he; said she; said I» (используемых наряду с «he said; she said; I said» после прямой речи) можно найти в литературных произведениях прошлых веков. Например: ‘I am not afraid of you,’ said he, smilingly. (Jane Austen) ‘Where is the Prince?’ said he. (Charles Dickens) «That’s a fire,» said I. (Mark Twain)

Если глаголы типа «said, asked, replied» употреблены в сложных формах времён, или если прямое дополнение стоит после «ask», инверсия не используется. Например: «I’ll help you,» Anton will say. «What’s the problem?» the driver asked her.

Стандартный порядок слов тоже используется в конструкциях с глаголами типа «said, asked, replied», стоящими после прямой речи, особенно в американском английском. Например: «I’ll help you,» Anton said. «What’s the problem?» the driver asked.

Если глаголы типа «said, asked, replied» стоят перед прямой речью, инверсия не используется. Например: Nina said, «Let’s go home.»

Инверсия в восклицательных предложениях

Инверсия иногда используется для усиления в восклицательных предложениях. Сравните обратный и прямой порядок слов в следующих восклицательных предложениях.

Ну и голоден же я! – Я такой голодный!

Ну и разозлилась же она! – Она так разозлилась!

А какой у нас сюрприз для вас! – У нас есть сюрприз для вас!

Пусть сбудутся все ваши желания!

Как красивы эти розы! – Как красивы эти розы!

Инверсия, зависящая от начала предложения

Следующие случаи инверсии возникают, когда некоторые части предложения, например, обстоятельство места или направления, идут в начале предложения. Инверсия в таких случаях заключается в перемещении вспомогательного глагола, а в некоторых случаях основного глагола (т.е. всей формы времени), в положение перед подлежащим.

Такие типы инверсии используются для эмфатического усиления, в основном в литературных произведениях. Изучающим язык желательно использовать прямой порядок слов в таких случаях. Примеры ниже даны в парах: Обратный порядок слов – Прямой порядок слов.

Инверсия после «so», «such», «as»

Таким несчастным выглядел мальчик, что мы дали ему все конфеты, которые у нас были. – Мальчик выглядел таким несчастным, что мы дали ему все конфеты, которые у нас были.

Таким было её разочарование, что она начала плакать. – Её разочарование было таким сильным, что она начала плакать.

Совы живут в дуплах деревьев, как и белки. – Совы и белки живут в дуплах деревьев.

Как следовало по обычаю, были избраны три бойца и три стрелка.

Инверсия после прилагательных и причастий

Ушли те дни, когда он был молод и полон энергии. – Те дни, когда он был молод и полон энергии, ушли.

Благословенны чистые сердцем.

Прекрасным было её пение.– Её пение было прекрасным.

Инверсия после обстоятельств места

Прямо перед ним стоял громадный двухголовый дракон. – Громадный двухголовый дракон стоял прямо перед ним.

Посередине дороги сидел странный старик, одетый в чёрное. – Странный старик, одетый в чёрное, сидел посередине дороги.

Позади горы лежала самая красивая долина, которую он когда-либо видел. – Самая красивая долина, которую он когда-либо видел, лежала позади горы.

Инверсия после послелогов

Двери открылись, и наружу выбежали несколько человек. – Несколько человек выбежали наружу, когда двери открылись.

Вверх полетели сотни детских воздушных шаров. – Сотни детских воздушных шаров полетели вверх.

Если подлежащее выражено личным местоимением, глагол ставится после подлежащего.

Вы готовы? Уходим! (выходим; отъезжаем)

Наружу он выбежал. – Он выбежал наружу.

Примечание: Прямое дополнение в начале предложения

Прямое дополнение иногда ставится в начале предложения для усиления. В таких случаях, подлежащее обычно стоит за дополнением, а сказуемое следует за подлежащим; то есть обратный порядок слов обычно не используется, если передвигается дополнение. Сравните:

Этого мы не знаем. – Мы не знаем этого.

Тех людей я могу спросить. – Я могу спросить тех людей.

Красные платья Лена не любит. – Лена не любит красные платья.

Инверсия в отрицательных конструкциях

Инверсия требуется в отрицательных предложениях, начинающихся со следующих отрицательных наречий и наречных сочетаний: never; never before; not only…but also; not until; no sooner; at no time; on no account; under no circumstances.

Инверсия также имеет место в предложениях, начинающихся со следующих наречий и наречных сочетаний, употребляемых в отрицательном смысле: rarely; seldom; hardly; scarcely; little; only when; only after; only then.

Отрицательные конструкции с обратным порядком слов используются для эмфатического усиления, в основном в официальной письменной речи и в литературных произведениях.

Если вам не нужно или вы не хотите использовать эмфатические отрицательные конструкции с обратным порядком слов, не ставьте вышеуказанные выражения в начале предложения.

Сравните следующие примеры обратного и стандартного порядка слов в предложениях с такими отрицательными конструкциями. Первое предложение в каждой группе имеет обратный порядок слов.

Примеры:

Никогда раньше я не испытывал такой страх. – Я никогда не испытывал такой страх раньше.

Никогда в жизни он не видел более отвратительного создания. – Он никогда в жизни не видел более отвратительного создания.

Он не только везде пролил кофе, но он также разбил мою любимую вазу. – Он не только везде пролил кофе, но также разбил мою любимую вазу.

Принцесса была не только поразительно красива, но она была также чрезвычайно умна. – Принцесса была не только поразительно красива, но и чрезвычайно умна.

Только гораздо позже я понял значение / значительность того события. – Я понял значение того события гораздо позже.

Не успела она положить / Едва / Как только она положила трубку, телефон зазвонил снова. – Как только она положила трубку, телефон зазвонил снова. Телефон зазвонил снова, как только она положила трубку.

Никогда вам нельзя выпускать его из поля зрения. – Вам не следует никогда выпускать его из поля зрения. Не выпускайте его из поля зрения ни на секунду.

Ни при каких обстоятельствах она не может считаться ответственной за его действия. – Её нельзя считать ответственной за его действия.

Редко приходилось мне видеть такой великолепный вид. – Я редко видел такой великолепный вид.

Редко мы осознаём, к чему могут привести наши действия. – Мы редко осознаём, к чему могут привести наши действия.

Он и представить не мог, что ему приготовила судьба. – Он не знал, что ему приготовила судьба.

Не успел я войти / Едва я вошёл в дом, как свет погас. – Я едва вошёл в дом, как свет погас.

Едва он сказал это, как появился волшебник. – Он едва успел сказать это, как появился волшебник.

Только когда я прибыл в гостиницу, я заметил, что пропала моя дорожная сумка. – Я заметил, что пропала моя дорожная сумка, только когда я прибыл в гостиницу.

Только после того, как мой гость ушёл, я вспомнил его имя. – Я вспомнил имя моего гостя только после того, как он ушёл.

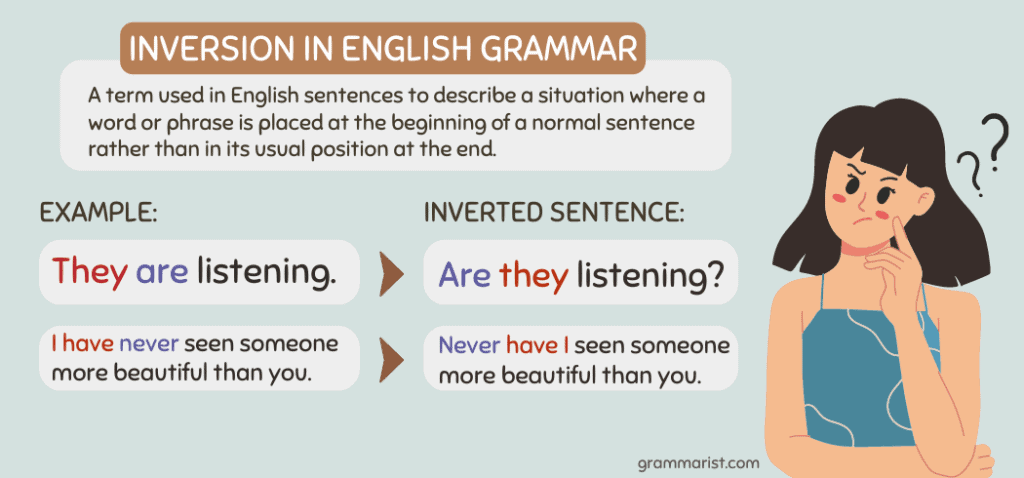

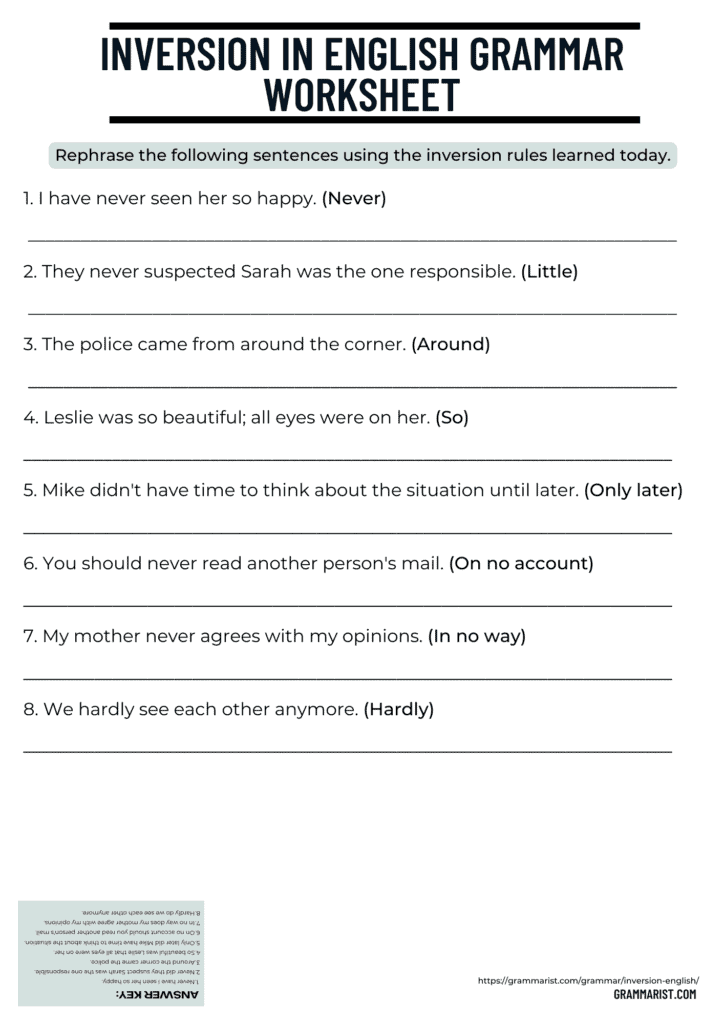

Such a mystery is English grammar inversion that we wonder how we can decipher it. When looking to expand your English vocabulary and upgrade your writing to more than just subject-plus-verb sentences, inversions can be of great help. See what inversion grammar is, how to use it in a sentence, and explore the different situations where it might be useful as I explain everything.

Inversion Explained

Inversion is a style where we change the natural order of the words in a sentence. I know it sounds strange, but it can work when done well. This goes beyond the inversion of a subject and verb and is used with more complexity to creating interesting sentence structures.

What Is an Inversion in English Grammar?

Inversion is a term used in English sentences to describe a situation where a word or phrase is placed at the beginning of a normal sentence rather than in its usual position at the end. It means you’re changing the natural order of the words in a sentence.

This can be used for stylistic purposes, to create a more complex or emphatic sentence structure, or simply for variety. In many cases, inverting words and phrases also involves changing their order from normal.

I’ve used it in my own writing from time to time. But if you’re writing fiction, I’d advise you to use this writing device sparingly.

A common type of inversion involves using adverbs or adjectives before main verbs. An inversion is a useful tool that can help to add variety and complexity to sentence structure, whether you are writing casually or formally.

Inversion of subject sentence examples:

- Never have I been more insulted in my life!

- Gone are the days when this used to be a peaceful town.

- Such greatness lies in the human heart; it knows no boundaries.

- Had you paid attention to me, we wouldn’t be in this mess!

What Are Inversions in Writing?

An inversion can contribute to various effects, from adding emphasis to creating a sense of suspense or irony. For instance, instead of saying, “I will go there tomorrow,” one might use an inversion by saying, “Tomorrow I will go there.”

In this case, the unexpected word order adds a subtle sense of urgency to the statement by pulling the focus away from the expected subject and verb.

This emphasis could be further strengthened by using an inversion and emphatic stress, such as “Right now, I have to go there!” or “Not today – tomorrow!”

Other techniques for using inversions include intentionally misdirecting the reader by inverting explicit clues to obscure certain information or drawing attention to certain key elements through unusual syntax.

Ultimately, an effective writer needs to carefully consider both the effect that they want to achieve and how best to accomplish it with the craft tools at their disposal – which may very well include the use of an inversion.

Why Is Inversion Used in English?

Inversion plays an important role in English grammar, providing a variety of functions both within and across sentences. For starters, inversions are often used to create a rhetorical impact or express surprise.

This can be seen, for example, in expressions like “Here comes the Sun!” where the normal word order is inverted for greater emphasis. In addition, inversions are often used to focus on a specific part of the sentence.

For instance, if we wished to highlight a particular object as being unique or noteworthy in some way, we might insert an “inverted” object into our phrasing: “A fugitive was all that lay between me and freedom.”

Inversion is used for formal, dramatic, or emphatic purposes.

What Are the Types of Inversion in Grammar?

The most common type of grammar inversion is when we form questions.

For example:

- They are listening. -> Are they listening?

Another type of grammar inversion is when we have negative adverbs. In formal writing and speech, adverbs with negative meanings go at the start of the sentence for added emphasis.

Some negative adverb examples include scarcely, seldom, never, hardly, rarely, etc.

Examples of inverted sentences with negative adverbs:

- Rarely does one see a gesture of good faith these days.

- Never have I seen someone more beautiful than you.

“Here” and “there” are words that can also be found in inverted sentences. They have to be used as adverbs of place to create an inversion.

Examples:

- Here is the book you wanted to borrow.

- I glanced across the room, and there was Candace in her beautiful red dress.

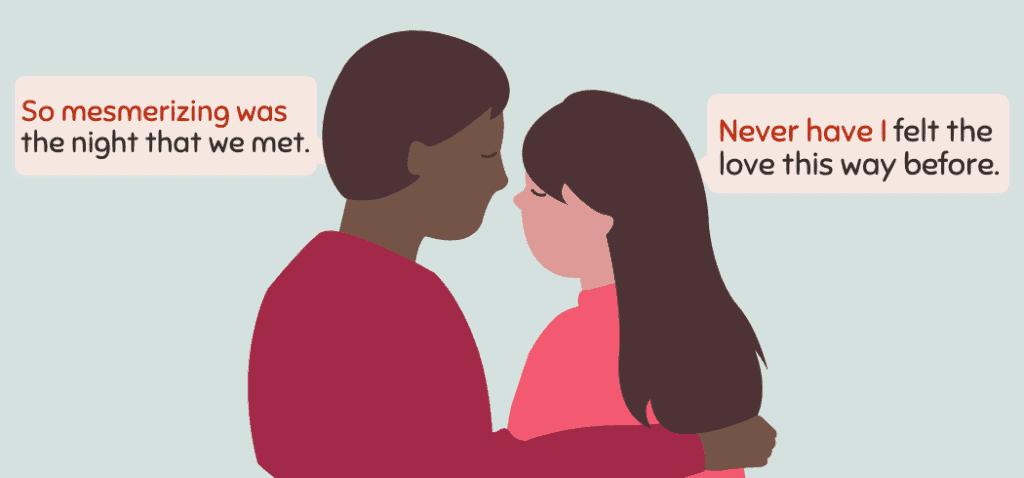

Another type of inversion in English is when we have “so” and “such.” To form inversions, remember the following two formulas:

- So + adjective + that + to be

- Such + to be + noun

Let’s look at this type of inversion in a sentence:

- So mesmerizing was the night that we met.

- Such are the troubles of the human mind.

You can also form an inversion by starting a sentence with the word “little.”

For example:

- Little did I know who was at the other end of the phone line.

Here is a more comprehensive list of negative adverbs and phrases used to make inversion:

- Only later

- Not only

- In no way

- Seldom

- Scarcely

- Rarely

- Never

- Hardly

- Only then

- Only in this way

- On no account

- No sooner

- So

- Such

- Only by

- Under no circumstance

Inversion With the Present Simple and Past Simple

When we speak or write in the present simple and past simple tenses, we don’t use any form of the auxiliary verb “to do.”

This means that when looking to create inversions, auxiliary verbs are used the same as when forming questions.

If you’re confused, here is what these inversions would look like:

- She rarely shows up on time.

- Rarely does she show up on time.

Inversion in Questions

You can take any normal sentence and invert it into a question.

- John will go to the university. (Normal sentence)

- Will John go to the university? (Question)

- Celia has done the homework. (Normal sentence)

- Has Celia done the homework? (Question)

Wrap Up

Inversion is a style where we change the natural order of the words in a sentence. It’s tricky to master, but when done right, it can elevate your writing. It is used in English grammar to describe a situation where a word or phrase is placed at the beginning of a sentence rather than in its usual position at the end. Inversions are often used to create a rhetorical impact or express surprise.

Какой все-таки странный английский язык!

Чтобы задать вопрос на русском мы просто изменяем интонацию. А на английском – достаем вспомогательный глагол, меняем порядок слов. И только тогда предложение действительно становится общим или информационным вопросом.

В русском языке чтобы сделать акцент на отдельном слове или идее, достаточно поставить эту информацию на первое место в предложении или выделить ее голосом, интонационно. А в английском, если вы хотите акцентировать, логически выделить (emphasize) какую-либо идею, – то нужно освоить целую науку под названием инверсия (inversion).

Тему “Inversion” обычно рассматривают на уровне Upper-Intermediate и выше. Однако в том или ином виде инверсия попадается нам и на более ранних уровнях изучения.

Я встретила свою первую инверсию когда училась в третьем классе: мы ставили сценку про котят. В тексте детской сказки были предложения:

Once upon a time there lived three little kittens.

In front of them stood a box of flour.

And off the kittens ran

и другие предложения с непрямым порядком слов.

Даже если ваш уровень начальный, на уровне третьего класса и детских сказок, вы точно встречались с непрямым порядком слов и инверсией. Она пряталась в предложениях с предлогом на первом месте и со словом there. А в текстах и аудио вы наверняка пересекались и с более сложными случаями использования инверсии.

В этой статье я расскажу вам все об инверсии в английском языке, вы научитесь узнавать ее и использовать в своей речи.

Каждый, кто изучает английский, знает, что в нем огромную роль играет порядок слов. Именно порядок слов отличает типы высказывания (утверждение, отрицание и вопрос) друг от друга.

Обычно в английском утверждении глагол следует после подлежащего (прямой порядок слов):

I understood how to use inversion after reading this article. – Я понял как использовать инверсию после прочтения этой статьи.

The phone rang when I had finished the dinner. – Телефон зазвонил, когда я закончил ужинать.

I learnt new words and improved my grammar knowledge. – Я выучил новые слова и улучшил знания грамматики.

Эти примеры звучат как факты. Вы просто рассказываете о том, что произошло, без всяких акцентов и эмоций.

Если же вы хотите выделить, акцентировать отдельный факт (отдельную часть предложения), вам нужно применить инверсию (изменить порядок слов). Вот те же примеры, только с инверсией:

Only after reading this article did I understand how to use inversion. – Только прочитав эту статью, я понял, как использовать инверсию.

Hardly had I finished my dinner when the phone rang. – Едва я закончил ужинать, как зазвонил телефон.

Not only did I learn new words but also improved my knowledge of grammar. – Я не только выучил новые слова, но еще и улучшил знания грамматики.

Иногда смысловой глагол в утверждениях занимает место перед подлежащим или присутствует вспомогательный глагол, который стоит перед подлежащим (как в вопросе).

Сложность в том, что не всегда инверсию можно перевести на русский язык, потому что в русском мы привыкли выделять важное интонациями и ударениями.К тому же, не каждое предложение можно трансформировать при помощи инверсии.

Как определить, нужно ли использовать инверсию? Прежде всего это зависит от цели высказывания. Инверсия уместна если вы хотите что-либо выделить, подчеркнуть, сделать акцент, поделиться эмоцией. Инверсию можно употреблять только с определенными конструкциями, словами и фразами. Часто по первым словам в предложении можно определить, есть ли необходимость менять порядок слов.

Мы рассмотрим 19 случаев использования инверсии. Я старалась организовать и сгруппировать информацию таким образом, чтобы вы не запутались и усвоили материал. Будет отлично, если вы создадите свой конспект, таблицу, mindmap и составите свои примеры.

1. После слов here и there

В разговорной речи распространены предложения, которые начинаются с «пустого» подлежащего there или here, которые переводим на русский, как «вот» или «вон»:

There goes your sister. – Вон идет твоя сестра.

Here comes Bobby. – А вот и Бобби.

Here’s your tea. – Вот твой чай.

Если подлежащее выражено личным местоимением (personal pronoun), то инверсии нет:

Here you go! – Держи! Вот, пожалуйста! (когда что-то кому-либо передаете)

There he is! – А вот и он!

Еще несколько примеров предложений с инверсией, в которых акцентируется именно место действия:

There are some questions after the text. – После текста несколько вопросов.

There is a table in the middle of the room. – Посередине комнаты стол.

I looked out and there were playing the children. – Я выглянула на улицу и там играли дети.

She opened the door and there stood a postman. – Она открыла дверь и там стоял почтальон.

Читайте подробнее об обороте there is/ there are, если забыли.

2. После указателей места (adverbials of place)

Если нужно сделать акцент на месте (emphasis on place), но хотите использовать не глагол to be, а именно глагол-действие (stand, sit, lie, hang etc.), то указатель места можно поставить на первое место, после него – глагол, а после подлежащее. Слово there в этом случае не нужно:

In front of the house lay a small garden. – Перед домом располагался маленький сад.

Above the table hung an old mirror. – Над столом висело старое зеркало.

At the fireplace was sitting an old man. – У камина сидел старик.

3. После указателей направления движения

Часто инверсия встречается в предложениях с глаголами движения (do, run, walk, drive etc.). На первом месте стоит указатель движения (предлог движения или фраза). Обратите внимание на предлоги, которые используются с разными глаголами движения. Рекомендую также вспомнить Глаголы перемещения на английском.

Across the road was running a boy. – Через дорогу бежал мальчик. And off they went! – И они ушли прочь!

Up the mountain were climbing three people. – Вверх по горе взбирались трое людей.

В описаниях, повествованиях, историях, указатели места и направления специально ставят в начале предложения, чтобы передать обстановку (setting), создать атмосферу.

4. После прямой речи

В рассказах после прямой речи можно услышать инверсию:

“Good night,” said mother (or mother said). – «Спокойной ночи», – сказала мама.

“Nothing serious has happened,” replied the policeman (or the policeman replied). – «Ничего серьезного не произошло», – ответил полицейский.

“Where is my bag?” asked the girl (or the girl asked). – «Где моя сумка?» – спросила девочка.

А если в качестве подлежащего используется личное местоимение – то нужен прямой порядок слов:

“Good night,” she said. – «Спокойной ночи», – сказала она.

“Nothing serious has happened,” he replied. – «Ничего серьезного не произошло», – ответил он.

Если после вопроса в прямой речи у глагола ask есть дополнение (указывается, у кого спросить) – нужен прямой порядок слов:

“Where is my bag?” the girl asked her friend. – «Где моя сумка?» – спросила девочка свою подругу.

Подведем итог: во всех вышеописанных случаях инверсия получается путем перестановки глагола на позицию перед подлежащим. При этом переносится вся форма, то есть если вспомогательный глагол во временной форме уже есть (was sitting, were playing, have done) – он не отделяется от смыслового (как происходит в вопросе), а если вспомогательного глагола в утверждении нет (во временах Present Simple и Past Simple) – то вспомогательные глаголы (do, does, did) не появляются.

В случаях использования, которые мы рассматрим далее, обращайте внимание на вспомогательный глагол. Теперь мы не просто переставляем слова местами, а следуем порядку слов, типичному для вопроса: вспомогательный глагол появляется и выходит на место перед подлежащим, а смысловой глагол остается после подлежащего. Не забывайте также, что во временах Present Simple и Past Simple, когда в предложении появляется вспомогательный глагол (does, did), смысловой лишается всех окончаний и стоит в первой форме.

5. В восклицаниях

В разговорной речи можно услышать эмоциональные восклицания с инверсией:

Oh, am I starving! – Какой же я голодный!/ Ну и голоден же я!

Have we got a present for you! – А какой у нас подарок для тебя!

Oh my, was he furious! – Ну и разозлился же он!

Отдельно стоит выделить восклицания-пожелания с модальным глаголом may:

May all your dreams come true! – Пусть сбудутся все твои желания!

May your life be happy! – Пусть твоя жизнь будет счастливой!

Узнайте больше о пожеланиях и о поздравлениях на английском.

Инверсия в восклицаниях часто встречается в письменных произведениях и в описаниях. Это книжный стиль (bookish style), который сейчас считают устаревшим:

How beautiful are these flowers! – Как красивы эти цветы!

How amazing is the view! – Какой потрясающий вид!

6. После прилагательных и причастий

Кстати, не всегда описательные предложения восклицательные. После прилагательных и причастий тоже можно использовать инверсию, если вы хотите сделать акцент на описании и выразить свое эмоциональное отношение к нему:

Amazing was the view. – Как прекрасен был вид.

Gone were those days. – Давно прошли те дни.

7. После комбинации so + прилагательное

При переводе этих предложений на русский язык, следует переводить so как «такой» и выделять его интонацией:

So huge was the airport that we got lost. – Аэропорт был такой огромный, что мы заблудились.

So unusual has her singing been that she has received a standing ovation. – Ее пение было таким необычным, что ей аплодировали стоя.

8. После слова such

Such – это тоже «такой» и служит для выделения меры чего-либо. Только в отличие от so, употребляется с существительными, а не с прилагательными:

Such is the price of this estate that no one can afford to buy it. – Цена поместья была такой, что никто не мог позволить себе его приобрести.

Such was the risk that he could not go out without the security. – Риск был таким, что он не мог выходить без охраны.

Полезно будет также вспомнить или узнать, как использовать слова so и such и в чем различия между ними.

9. После as и than

В литературе, повествованиях авторы применяют инверсию после as и than, когда что-либо сравнивают или указывают на сходство:

Many animals hibernate in winter, as do bears. – Многие животные впадают в зимнюю спячку, как и медведи.

As was the tradition, we threw some coins into the water. – По традиции мы бросили несколько монет в воду.

Native speakers of English speak more fluently, than do learners. – Носители английского языка говорят более бегло, чем это делают изучающие.

Кроме того, существует целый ряд слов и выражений с отрицательным значением, после которых непременно используется инверсия.

10.После наречий с отрицательным значением: barely, hardly, scarcely, seldom, rarely

Seldom did she think about her future. – Она почти не думала о своем будущем.

Rarely does a day pass without any phone calls. – Почти ни дня не проходит без телефонных звонков.

Обратите внимание: в предложениях с наречиями barely, hardly, scarcely (они все могут переводиться, как «едва», «только-только», «как только») когда есть два действия: одно едва завершилось, а другое сразу же началось, очень часто присутствует слово when:

Barely was I ready when the taxi arrived. – Едва я собрался, приехало такси.

Hardly did she open the window when it started to rain. – Как только она открыла окно, пошел дождь.

Scarcely had he fallen asleep when the phone rang. – Едва она уснула как зазвонил телефон.

11. После слов never, nowhere

Never had we been more motivated than during the first month of work. – Никогда не были они более мотивированы, чем в течение первого месяца работы.

Nowhere could we buy flowers in the middle of the night. – Нам нигде не купить цветы среди ночи.

12. После слова little

Слово little в инвертированных конструкциях переводится как «совсем не, вовсе не», и употребляется с глаголами know, understand, think и подобными, после которых часто можно встретить слова what, how, when:

Little did they know what to do. – Они совсем не знали, что делать.

Little could he understand how to drive a car. – Она совсем не понимала, как водить машину.

Little do I know when to start her presentation. – Она совсем не знала, когда начинать презентацию.

13. После no sooner

Список слов и выражений с отрицательным значением продолжает no sooner: «как только», или «не успел что-либо сделать, как…»:

No sooner had we boarded than the baby started to cry. – Как только мы зашли на борт, ребенок начал плакать.

No sooner had she got the job than the recession started. – Как только она получила работу, начался кризис.

Обратите внимание: в случае со словами barely, hardly, scarcely мы употребляли when, чтобы связать во времени две чаcти предложения, два действия.

А с no sooner нужно использовать than. Запомнить можно так: sooner – это сравнительная степень, а чтобы сравнить, нам нужно не when, a than.

14. После not в различных выражениях

Not может вступать в разные сочетания, после которых порядок слов должен быть изменен. Предложения такого типа могут переводиться на русский по-разному:

Not a single word of apology did we hear from them. – Ни единого слова извинения мы о нее не услышали.

Not until two hours later did I remember about the appointment. – Не ранее, чем через два часа я вспомнил о договоренности.

Not for a moment did I forget about him. – Ни на момент я о нем не забывала.

Not till I finished the work could I go home. – Я мог пойти домой не ранее чем окончу работу.

Отдельно хочу прокомментировать комбинацию not only … but also. Когда вы хотите сделать акцент на двух идеях или действиях, и в обычном предложении использовали бы союз and, то можете смело применить инверсию:

People can see the paintings and meet the artist. – Люди могут увидеть картины и встретиться с художником.

Not only can people see the paintings, they can also meet the artist. – Люди могут не только увидеть картины, но и встретиться с художником.

Yesterday I overslept and my flight was delayed. – Я проспал и мой рейс задержали.

Not only did I oversleep yesterday, but also the flight was delayed. – Вчера я не только проспал, еще и мой рейс задержали.

Как видите, в первых предложениях информация преподносится нейтрально, а вот во вторых присутствует акцент.

15. После устойчивых выражений со словом no

Если предложение начинается с этих выражений со словом no – нужна инверсия: оn no account (ни в коем случае), under no circumstances (не при каких обстоятельствах), in no way (никоим образом), at no time (никогда):

On no account are the children to stay out late! – Ни в коем случае детям не разрешается гулять допоздна.

Under no circumstances should you open the door. – Ни при каких обстоятельствах не открывай дверь.

In no way did I want to offend you. – Никоим образом я не хотел тебя обидеть.

At no time did you tell me the truth. – Никогда ты не говорил мне правды.

16. После фраз-указателей времени (time clause) со словом only

Если вы хотите поставить акцент на время или на частоту, то выносите указатель времени с only (только, лишь, едва) вперед, и после него – непрямой порядок слов:

Only after the investigation is finished will he get his passport back. – Только после того, как расследование будет завершено, он получит назад свой паспорт.

Only once before have I lost my keys. – Лишь один-единственный раз я терял свои ключи.

Only when I left the house did I remember about your warning. – Только когда я уже вышел из дому, я вспомнил про твое предостережение.

17. Had it not been for … , would have + V3

Здесь нужно разобраться подробнее. Мы часто используем такое выражение: Если бы не …, то … , когда что-то произошло в прошлом и мы рассуждаем на эту тему. Например, мы можем кого-то поблагодарить или порадоваться тому, как сложились обстоятельства:

Если бы не ты, у меня бы ничего не получилось.

Если бы не та конференция, мы с тобой никогда бы не встретились.

Как же это выразить на английском? При помощи конструкции Had it not been for …, would have + V3:

Had it not been for you, I would not have passed that exam. – Если бы не ты, я бы не сдал тот экзамен.

Had it not been for that conference, we would never have met with you. – Если бы не та конференция, мы с вами никогда бы не встретились.

Эта конструкция всегда начинается с отрицания, а вторая часть можнт быть как утвердительной, так и отрицательной. Возможно использовать третий тип условных предложений или условное предложение смешанного типа, но таким образом вы не сделаете акцент на «Если бы не …».

18. В условной части условных предложений

Условная часть условных предложений (после if) часто имеет «инвертированный» вид:

Conditional 1:

If you should need my help, please contact me.

Should you need my help, please contact me. – Если вам понадобится помощь, связывайтесь со мной, пожалуйста.

Conditional 2:

If you worked from morning till night, you would be very tired.

Were you to work from morning till night, you would be very tired. – Работай ты с утра до ночи, ты бы очень устал.

Conditional 3:

If I had known there was a queue, I would have booked the tickets online.

Had I known there was a queue, I would have booked the tickets online. – Знай я раньше, что там очередь, я бы купил билеты онлайн.

Конечно, чтобы трансформировать обычные conditional sentences в inverted conditional sentences, вам нужно разобраться, как их образовывать и использовать. Читайте об условных предложениях подробнее:

Conditional 1. Условные предложения первого типа

Conditional 2. Условные предложения второго типа

Conditional 3. Условные предложения третьего типа

19. После so, neither, nor значении «тоже»

Говоря об инверсии с so, neither и nor, для удобства можно выделить два типа предложений: короткие реакции и предложения-повествования.

Использование этих слов в реакциях изучают на уровне pre-intermediate, помните: «So do I», «Neither do I»?

В блоге мы уже обсуждали эту тему, читайте подробнее в статье Как сказать «тоже» на английском?. Инверсия в данном случае подчеркивает, акцентирует сходство или согласие. Основной принцип: соглашаетесь с утверждением – говорите so (и после инверсия), соглашаетесь с отрицанием – говорите neither (и после инверсия):

I like summer. – So do I! – Я люблю лето. – Я тоже!

I have not travelled this year yet. – Neither/Nor have I! – В этом году я еще никуда не ездил. – Я тоже!

Непрямой порядок слов может возникнуть и в середине повествовательного предложения, во второй его части:

My brother dreams of becoming a lawyer and so do I. – Мой брат мечтает стать юристом и я тоже.

Mary has not lost any weight and neither has her husband. – Мэри совсем не похудела и ее муж тоже.

The tourist did not know which way to go and nor did we. – Турист не знал, куда идти и мы тоже не знали.

Для чего же вам пригодится инверсия?

1. Понимание языка в оригинале

Как вы заметили, многие из случаев использования относятся как к литературному, формальному стилю, так и характерны для разговорного английского, поэтому чтобы понимать, что конкретно имеет в виду автор вам нужно владеть знаниями об инверсии.

2. Яркая и насыщенная естественная речь

Если вы хотите преодолеть эффект плато и кризис среднего уровня и выйти на новый уровень, четко передавать свои мысли и эмоции, то обогащайте вашу речь предложениями с инверсией.

3. Международные экзамены

Инверсия – это тот золотой ключик, который откроет перед вами дополнительные баллы на экзаменах. Все, без исключения пособия для подготовки к FCE, CAE, CPE, IELTS рассматривают эту тему и выносят ее на отдельное место. Если в вашем сочинении или устном ответе будет уместное, содержательное, правильно сформулированное предложение – плюс на экзамене вам гарантирован.

А если вам нужна профессиональная помощь с грамматикой, разговорным английским, подготовкой к экзаменам – наши опытные преподаватели всегда готовы составить для вас индивидуальную программу и предложить удобное время для обучения по Скайп! В ENGINFORM мы не читаем скучных лекций, не используем русский язык на занятии, а говорим только на английском и максимум времени посвящаем вашей практике!

Попробуйте английский по скайп в ENGINFORM на бесплатном вводном занятии и оцените все преимущества индивидуального обучения.

Успехов вам в изучении английского!

Увидели ошибку в тексте? Выделите её и нажмите на появившуюся стрелку или CTRL+Enter.

Если сравнивать английскую грамматику с русской, то здесь несколько больше законов и правил, соблюдение которых строго необходимо. Если взять, к примеру, такое явление, как порядок слов в английском предложении, то здесь можно заметить, что отступить от норм так, как в русском языке уже не получится. Правила грамматики запрещают переставлять слова во фразе так, как того хочется говорящему, и строго регламентируют позицию каждого члена предложения.

Порядок слов в английском языке бывает двух видов: прямой и обратный (инверсионный). О каждом из них следует сказать более подробно.

Принцип прямого порядка слов

Прямой порядок слов в английском предложении – это расстановка членов предложения в определенном порядке. Так, в любой фразе на первом месте должно стоять подлежащее, за ним идет сказуемое, простое или составное, а дальше оставшиеся члены предложения.

Вот примеры того, как это выглядит:

· He came to me at sunset – Он пришел ко мне на закате

· We shall pass all our exams – Мы сдадим все свои экзамены

При этом у второстепенных членов также есть свой некий, пусть и негласный, порядок использования и своя последовательность. Если, например, в предложении употреблено несколько прилагательных, то оптимальной будет следующая схема их расположения (взяты основные типы определений):

Личное мнение – размер – возраст – форма – цвет – происхождение – материал

· He brought me a beautiful new green English book

· I want you to but that big old Italian wooden armchair

У обстоятельств в английском предложении также имеется свой порядок. Вообще считается, что английский язык лучше всего строить по следующему принципу: что? где? когда? Это значит, что при упоминании в предложении нескольких обстоятельств правильнее употреблять сначала место, а затем время:

· I met her near the shop yesterday – Я встретил ее у магазина вчера

· She will arrive at the station in a few hours – Она прибудет на станцию через несколько часов

Note: иногда допустимо ставить наречие времени в начале, нарушая тем самым прямой порядок слов в предложении. Это допустимо в том случае, когда говорящий хочет выразительно подчеркнуть срок совершения действия:

Tomorrow she will be 20 – Завтра ей будет 20 лет (акцент делается именно на слове «завтра»)

Обратный порядок слов в английском предложении

Inversion in English – это обратный порядок, характерный для ряда ситуаций и противоречащий прямому порядку. Инверсия в английском языке встречается довольно часто и, несмотря то, что многие не слышали о таком понятии, инверсионный порядок встречается практически в любом диалоге и самых обыденных ситуациях.

Инверсия в вопросах

Самая привычная ситуация для неправильного порядка слов – это вопросительные предложения. В таких конструкциях привычная поставка подлежащего на первое место невозможна.

Кроме того, порядок слов в вопросительном предложении зависит еще и от типа самого используемого вопроса. К примеру, в общем вопросе первоначальную позицию занимает либо вспомогательный глагол нужного времени, либо форма глагола to be, и только за чем-то из этого должно идти подлежащее:

· Will they set off tomorrow? – Они отправятся завтра?

· Are you a military man? – Вы военный?

Например, порядок слов в специальном вопросе тоже особенный: сначала должно идти главное вопросительное слово (why, when, how, etc.), за ним – вспомогательный глагол (или to be), и только потом идет подлежащее:

· Why did you return? – Почему ты вернулся?

· Where is your favorite cup? – Где твоя любимая чашка?

Note: для вопросов к подлежащему, начинающихся со слов who или what, обратный порядок слов не характерен; здесь не используется никаких вспомогательных глаголов, и English grammar не предусматривает инверсии в таких предложениях:

· Who brought this letter? – Кто принес это письмо?

· What made you feel happy? – Что заставило тебя чувствовать себя счастливым?

Стилистическая инверсия

Stylistic inversion – это особая сфера употребления обратного порядка слов, когда инверсия в английском языке нужна для выразительной передачи автором своей мысли и подчеркивания особенности высказывания. Здесь есть даже некая inversion table, так как случаев подобного использования обратного порядка слов несколько.

У такого типа inversion переводом часто служат эмоциональные фразы, которые передает сильный посыл автора, например:

Little does she know about me! – Мало она обо мне знает!

Еще один случай, который встречается довольно часто – это инверсия в условных предложениях, когда союз, вводящий условие, опускается, и порядок слов становится стандартным. Можно сравнить такие предложения:

· Had he come yesterday, we wouldn’t have had any problems – Приди он вчера, у нас бы не было никаких проблем

· Were she a little cleverer, she could understand everything – Будь она немного умнее, она могла бы все понять

Случаев инверсии в английском языке достаточно, но, как правило, ее использование редко является обязательным (за исключением вопросительных предложений) и относится скорее к авторским приемам, нежели к обязательному грамматическому строю. Особенно это касается случаев употребления стилистической инверсии, характерной больше для разговорного английского. Хотя знать подобные случаи будет совершенно нелишним, ведь их употребление сделает язык богаче и позволит выразить свою мысль ярко и в максимально свободном стиле.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the syntactic phenomenon. For the sound change, see Metathesis.

In linguistics, inversion is any of several grammatical constructions where two expressions switch their canonical order of appearance, that is, they invert. There are several types of subject-verb inversion in English: locative inversion, directive inversion, copular inversion, and quotative inversion. The most frequent type of inversion in English is subject–auxiliary inversion in which an auxiliary verb changes places with its subject; it often occurs in questions, such as Are you coming?, with the subject you is switched with the auxiliary are. In many other languages, especially those with a freer word order than English, inversion can take place with a variety of verbs (not just auxiliaries) and with other syntactic categories as well.

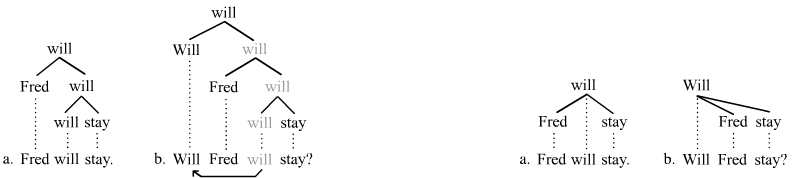

When a layered constituency-based analysis of sentence structure is used, inversion often results in the discontinuity of a constituent, but that would not be the case with a flatter dependency-based analysis. In that regard, inversion has consequences similar to those of shifting.

In English[edit]

In broad terms, one can distinguish between two major types of inversion in English that involve verbs: subject–auxiliary inversion and subject–verb inversion.[1] The difference between these two types resides with the nature of the verb involved: whether it is an auxiliary verb or a full verb.

Subject–auxiliary inversion[edit]

The most frequently occurring type of inversion in English is subject–auxiliary inversion. The subject and auxiliary verb invert (switch positions):

-

- a. Fred will stay.

- b. Will Fred stay? — Subject–auxiliary inversion with yes/no question

-

- a. Larry has done it.

- b. What has Larry done? — Subject–auxiliary inversion with constituent question

-

- a. Fred has helped at no point.

- b. At no point has Fred helped. — Subject–auxiliary inversion with fronted expression containing negation (negative inversion)

-

- a. If we were to surrender, …

- b. Were we to surrender, … — Subject–auxiliary inversion in condition clause

The default order in English is subject–verb (SV), but a number of meaning-related differences (such as those illustrated above) motivate the subject and auxiliary verb to invert so that the finite verb precedes the subject; one ends up with auxiliary–subject (Aux-S) order. That type of inversion fails if the finite verb is not an auxiliary:

-

- a. Fred stayed.

- b. *Stayed Fred? — Inversion impossible here because the verb is NOT an auxiliary verb

(The star * is the symbol used in linguistics to indicate that the example is grammatically unacceptable.)

Subject–verb inversion[edit]

In languages like Italian, Spanish, Finnish, etc. subject-verb inversion is commonly seen with a wide range of verbs and does not require an element at the beginning of the sentence. See the following Italian example:

In English, on the other hand, subject-verb inversion generally takes the form of a Locative inversion. A familiar example of subject-verb inversion from English is the presentational there construction.

There’s a shark.

English (especially written English) also has an inversion construction involving a locative expression other than there («in a little white house» in the following example):

In a little white house lived two rabbits.[2]

Contrary to the subject-auxiliary inversion, the verb in cases of subject–verb inversion in English is not required to be an auxiliary verb; it is, rather, a full verb or a form of the copula be. If the sentence has an auxiliary verb, the subject is placed after the auxiliary and the main verb. For example:

-

- a. A unicorn will come into the room.

- b. Into the room will come a unicorn.

Since this type of inversion generally places the focus on the subject, the subject is likely to be a full noun or noun phrase rather than a pronoun. Third-person personal pronouns are especially unlikely to be found as the subject in this construction:

-

- a. Down the stairs came the dog. — Noun subject

- b. ? Down the stairs came it. — Third-person personal pronoun as subject; unlikely unless it has special significance and is stressed

- c. Down the stairs came I. — First-person personal pronoun as subject; more likely, though still I would require stress

In other languages[edit]

Certain other languages, like other Germanic languages and Romance languages, use inversion in ways broadly similar to English, such as in question formation. The restriction of inversion to auxiliary verbs does not generally apply in those languages; subjects can be inverted with any type of verb, but particular languages have their own rules and restrictions.

For example, in French, tu aimes le chocolat is a declarative sentence meaning «you like the chocolate». When the order of the subject tu («you») and the verb aimes («like») is switched, a question is produced: aimes-tu le chocolat? («do you like the chocolate?»). In German, similarly, du magst means «you like», whereas magst du can mean «do you like?».

In languages with V2 word order, such as German, inversion can occur as a consequence of the requirement that the verb appear as the second constituent in a declarative sentence. Thus, if another element (such as an adverbial phrase or clause) introduces the sentence, the verb must come next and be followed by the subject: Ein Jahr nach dem Autounfall sieht er wirklich gut aus, literally «A year after the car accident, looks he really good». The same occurs in some other West Germanic languages, like Dutch, in which this is Een jaar na het auto-ongeval ziet hij er werkelijk goed uit. (In such languages, inversion can function as a test for syntactic constituency since only one constituent may surface preverbally.)

In languages with free word order, inversion of subject and verb or of other elements of a clause can occur more freely, often for pragmatic reasons rather than as part of a specific grammatical construction.

Locative inversion[edit]

Locative inversion is a common linguistic phenomenon that has been studied by linguists of various theoretical backgrounds.

In multiple Bantu languages, such as Chichewa,[3] the locative and subject arguments of certain verbs can be inverted without changing the semantic roles of those arguments, similar to the English subject-verb inversion examples above. Below are examples from Zulu,[4] where the numbers indicate noun classes, SBJ = subject agreement prefix, APPL = applicative suffix, FV = final vowel in Bantu verbal morphology, and LOC is the locative circumfix for adjuncts.

- Canonical word order:

ba-fund-el-a

2.SBJ-study-APPL—FV

e-sikole-ni.

LOC:7—7.school-LOC

«The children study at the school.»

- Locative inversion:

si-fund-el-a

7.SBJ-study-APPL—FV

«The children study at the school.» (lit. «The school studies the children.»)

In the locative inversion example, isikole, «school» acts as the subject of the sentence while semantically remaining a locative argument rather than a subject/agent one. Moreover, we can see that it is able to trigger subject-verb agreement as well, further indicating that it is the syntactic subject of the sentence.

This is in contrast to examples of locative inversion in English, where the semantic subject of the sentence controls subject-verb agreement, implying that it is a dislocated syntactic subject as well:

- Down the hill rolls the car.

- Down the hill roll the cars.

In the English examples, the verb roll agrees in number with cars, implying that the latter is still the syntactic subject of the sentence, despite being in a noncanonical subject position. However, in the Zulu example of locative inversion, it is the noun isikole, «school» that controls subject-verb agreement, despite not being the semantic subject of the sentence.

Locative inversion is observed in Mandarin Chinese. Consider the following sentences:

- Canonical word order

‘At the entrance stands a/the sentry’

- Locative inversion

‘At the entrance stands a/the sentry’ [5]

In canonical word order, the subject (gǎngshào ‘sentry’) appears before the verb and the locative expression (ménkǒu ‘door’) after the verb. In Locative inversion, the two expressions switch the order of appearance: it is the locative that appears before the verb while the subject occurs in postverbal position. In Chinese, as in many other languages, the inverted word order carry a presentational function, that is, it is used to introduce new entities into discourse.[6]

Theoretical analyses[edit]

Syntactic inversion has played an important role in the history of linguistic theory because of the way it interacts with question formation and topic and focus constructions. The particular analysis of inversion can vary greatly depending on the theory of syntax that one pursues. One prominent type of analysis is in terms of movement in transformational phrase structure grammars.[7] Since those grammars tend to assume layered structures that acknowledge a finite verb phrase (VP) constituent, they need movement to overcome what would otherwise be a discontinuity. In dependency grammars, by contrast, sentence structure is less layered (in part because a finite VP constituent is absent), which means that simple cases of inversion do not involve a discontinuity;[8] the dependent simply appears on the other side of its head. The two competing analyses are illustrated with the following trees:

The two trees on the left illustrate the movement analysis of subject-auxiliary inversion in a constituency-based theory; a BPS-style (bare phrase structure) representational format is employed, where the words themselves are used as labels for the nodes in the tree. The finite verb will is seen moving out of its base position into a derived position at the front of the clause. The trees on the right show the contrasting dependency-based analysis. The flatter structure, which lacks a finite VP constituent, does not require an analysis in terms of movement but the dependent Fred simply appears on the other side of its head Will.

Pragmatic analyses of inversion generally emphasize the information status of the two noncanonically-positioned phrases – that is, the degree to which the switched phrases constitute given or familiar information vs. new or informative information. Birner (1996), for example, draws on a corpus study of naturally-occurring inversions to show that the initial preposed constituent must be at least as familiar within the discourse (in the sense of Prince 1992) as the final postposed constituent – which in turn suggests that inversion serves to help the speaker maintain a given-before-new ordering of information within the sentence. In later work, Birner (2018) argues that passivization and inversion are variants, or alloforms, of a single argument-reversing construction that, in turn, serves in a given instance as either a variant of a more general preposing construction or a more general postposing construction.

The overriding function of inverted sentences (including locative inversion) is presentational: the construction is typically used either to introduce a discourse-new referent or to introduce an event which in turn involves a referent which is discourse-new. The entity thus introduced will serve as the topic of the subsequent discourse.[9] Consider the following spoken Chinese example:

‘Right then came over an old man.’

‘this old man, he was standing without moving.’ [10]

The constituent yí lǎotóur «an old man» is introduced for the first time into discourse in post-verbal position. Once it is introduced by the presentational inverted structure, it can be coded by the proximal demonstrative pronoun zhè ‘this’ and then by the personal pronoun tā – denoting an accessible referent: a referent that is already present in speakers’ consciousness.

See also[edit]

- Constituent (linguistics)

- Dependency grammar

- Finite verb

- Head (linguistics)

- Phrase structure grammar

- Verb phrase

Notes[edit]

- ^ The use of terminology here, subject-auxiliary inversion and subject–verb inversion, follows Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:410).

- ^ Birner, Betty Jean (1994). «Information status and word order: an analysis of English inversion». Language. 2 (70): 233–259. doi:10.2307/415828. JSTOR 415828.

- ^ Bresnan, Joan (1994). «Locative Inversion and Architecture of Universal Grammar». Language. 70 (1): 72–131. doi:10.2307/416741. JSTOR 416741.

- ^ Buell, Leston Chandler (2005). «Issues in Zulu Morphosyntax». PhD Dissertation, UCLA.

- ^ Shen 1987, p. 197.

- ^ Lena, L. 2020. Chinese presentational sentences: the information structure of Path verbs in spoken discourse». In: Explorations of Chinese Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- ^ The movement analysis of subject-auxiliary inversion is pursued, for instance, by Ouhalla (1994:62ff.), Culicover (1997:337f.), Radford (1988: 411ff., 2004: 123ff).

- ^ Concerning the dependency grammar analysis of inversion, see Groß and Osborne (2009: 64-66).

- ^ Lambrecht, K., 2000. When subjects behave like objects: An analysis of the merging of S and O in sentence-focus constructions across languages. Studies in Language, 24(3), pp.611-682.

- ^ Lena 2020, ex. 10.

References[edit]

- Birner, B. 2018. On constructions as a pragmatic category. Language 94.2:e158-e179.

- Birner, B. 1996. The discourse function of inversion in English. Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. NY: Garland.

- Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Greenbaum, S. and R. Quirk. 1990. A student’s grammar of the English language. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43-90.

- Lena, L. 2020. Chinese presentational sentences: the information structure of Path verbs in spoken discourse». In: Explorations of Chinese Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

- Prince, E. F. 1992. The ZPG letter: Subjects, definiteness, and information-status. In W. C. Mann and S. A. Thompson, Discourse description: Diverse linguistic analyses of a fundraising text. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 295-325.

- Shen, J. 1987. Subject function and double subject construction in mandarin Chinese. In Cahiers de linguistique — Asie orientale, 16-2. pp. 195-211.

- Quirk, R. S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1979. A grammar of contemporary English. London: Longman.

- Radford, A. 1988. Transformational Grammar: A first course. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Radford, A. 2005. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.