Table of Contents

- Is having knowledge the same thing as being correct?

- What is word knowledge?

- How can I improve my vocabulary knowledge?

- What is skill fluency?

- How do you build fluency?

- How can I learn fluency?

- Can fluency be taught?

- Why do students struggle with reading?

- What causes poor reading fluency?

- How can I practice fluency at home?

The three levels of Word Knowledge are the unknown, acquainted, and established. The unknown level of word knowledge occurs when the student has no idea of a word’s meaning. … At the established level, student meaning of words become easy, more faster, and actually very supportive.

Is having knowledge the same thing as being correct?

Knowledge is information of which someone is aware. Knowledge is also used to mean the confident understanding of a subject, potentially with the ability to use it for a specific purpose. Wisdom is the ability to make correct judgments and decisions.

Word knowledge is knowing the meanings of words, knowing about the relationships between words (word schema), and having linguistic knowledge about words.

How can I improve my vocabulary knowledge?

7 Ways to Improve Your Vocabulary

- Develop a reading habit. Vocabulary building is easiest when you encounter words in context. …

- Use the dictionary and thesaurus. …

- Play word games. …

- Use flashcards. …

- Subscribe to “word of the day” feeds. …

- Use mnemonics. …

- Practice using new words in conversation.

What is skill fluency?

Fluency is the ability to read a text accurately, quickly, and with expression. Reading fluency is important because it provides a bridge between word recognition and comprehension.

How do you build fluency?

10 Ways to improve reading fluency

- Read aloud to children to provide a model of fluent reading. …

- Have children listen and follow along with audio recordings. …

- Practice sight words using playful activities. …

- Let children perform a reader’s theater. …

- Do paired reading. …

- Try echo reading. …

- Do choral reading. …

- Do repeated reading.

How can I learn fluency?

5 Surefire Strategies for Developing Reading Fluency

- Model Fluent Reading. In order to read fluently, students must first hear and understand what fluent reading sounds like. …

- Do Repeated Readings in Class. …

- Promote Phrased Reading in Class. …

- Enlist Tutors to Help Out. …

- Try a Reader’s Theater in Class.

Can fluency be taught?

It ranges from reading a text with appropriate accuracy, pacing, and expression to decoding words and comprehending what the text means. Moreover, how we teach fluency varies as well. … Rather, I have found in my own experience that essential fluency skills still need to be continually taught in grades K-12.

Why do students struggle with reading?

Children may struggle with reading for a variety of reasons, including limited experience with books, speech and hearing problems, and poor phonemic awareness.

What causes poor reading fluency?

Some children fail to develop adequate fluency for another reason: They have had limited reading practice, particularly practice in high-success texts. High-success reading experiences are characterized by accurate, fluent read– ing with good understanding of the text that was read.

How can I practice fluency at home?

What kids can do to help themselves

- Track the words with your finger as a parent or teacher reads a passage aloud. Then you read it.

- Have a parent or teacher read aloud to you. Then, match your voice to theirs.

- Read your favorite books and poems over and over again. Practice getting smoother and reading with expression.

Sentence level work is everything your child will be taught about grammar, text content and punctuation in the primary-school classroom. We offer some examples of activities to help them practise and improve their writing at home.

What is a sentence?

A sentence is one word or a group of words that makes sense by itself (a grammatical unit).

Sentences begin with a capital letter and end with a full stop, a question mark or an exclamation point.

Download Fantastic FREE Grammar Resources!

- Perfect Punctuation Workbook

- Grammar Games Pack

- PLUS 100s of other grammar resources

There are four types of sentence: statements, commands, questions and exclamations.

What is sentence level?

Teachers focus on three areas in literacy: word level work, sentence level work and text level work.

Word level relates to the spelling of individual words.

Sentence level relates to grammar, content and punctuation.

Text level relates to the structuring of a text as a whole, for example: writing a beginning, a middle and an end for a story, using paragraphs, remembering an introduction for a report, etc.

Sentence level work in the primary classroom

Sentence level work could involve the following in Reception, KS1 and KS2:

- Reminding children to use capitals at the start of their sentences and full stops at the end. For this, children need to understand what a sentence is (a grammatical unit made up of one or more words). Lots of practice paying attention to pausing at the full stop when you’re reading together at home can help with this.

- Encouraging children to think about where question marks and exclamation marks should go. It is important to discuss with them what these forms of punctuation are for and point them out when reading.

- Showing children how commas are often used to split up clauses in a sentence.

- Modelling correct use of speech punctuation.

- Helping them understand how to make nouns and verbs agree (for example, if a child has written: He take the bucket and spade, this would need to be corrected to: He takes the bucket and spade).

- Modelling making a sentence more interesting by adding adjectives to a noun, or adding adverbs to a verb.

- Showing children how two simple sentences can be joined together using a connective to make a complex sentence. For example: The monster roared loudly. It was hungry. could be changed to: The monster roared loudly because it was hungry.

Sentence level work can be done as a stand-alone activity, for example: teachers may give children worksheets on connectives, punctuation or powerful verbs.

It is also often taught as part of the main literacy teaching of a text; when modelling or editing a piece of writing, a teacher will pay particular attention to sentence level work. Modelling good sentences on the board is crucial for children to be able to learn how to form their own sentences. Reading a range of texts is also very important in terms of getting used to how sentences are structured.

Creating sentences (writing)

Often the focus in classrooms is on producing whole texts; however, it is important to give students explicit opportunity to pay attention to writing at the text, sentence and word levels (Rose and Martin 2012).

Text level requires attention to patterns that are evident in different genres (e.g. passive voice in an explanation, abstract nouns in an argument) as well as to the ways in which the parts of the text are linked (e.g. through the use of connectives) (Derewianka, 2011).

Sentence level requires examination of the ways in which clauses are combined or how clauses relate to each other (e.g. relationships of time, place, causality) (Derewianka, 2011). Word level attends to the individual words or groups of words such as nouns/ noun groups. (Derewianka, 2011).

The following strategies support students to focus on the construction of sentences and to develop confidence in talking about their writing. Both also offer students the experience of exploring articulating both the language choices they have made and exploring the effect of their writing on others (VCELY395 and

VCELY396).

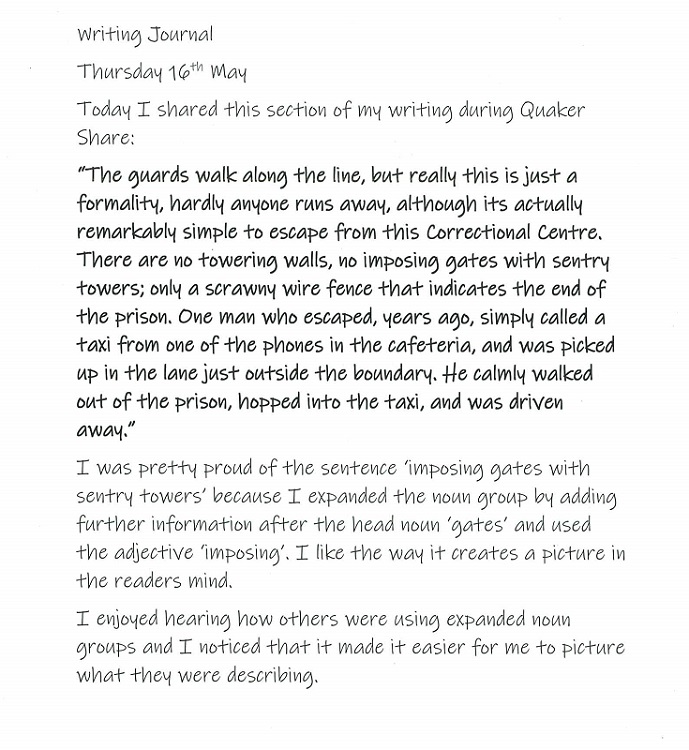

Quaker share

A Quaker Share (Dawson 2009) is used to support students to share their own writing in a group, to build confidence about reading aloud, and to provide them with opportunities to explore the impact of their writing on others.

A traditional Quaker Share is loosely structured in the following ways:

- Students read aloud a few of their sentences to the group.

- The reading moves around the group, but no comments are made about what is read.

- Students can be encouraged to record things they hear that they find enjoyable or particularly interesting.

- Once each member of the group has shared some of their writing, they discuss how it felt to read to a group who is quiet and listens.

This activity can be adapted and focused in in many ways, depending upon the context of the group and purpose of learning. Always consider the ways that you may employ this strategy so that your students feel comfortable to share their writing. The teacher may decide that on the first occasion students share with a small group but then progress to a larger group as confidence is developed.

In the context of narrative writing, the teacher might ask for students to share a paragraph that includes 2-3 sentences that use expanded noun groups well (for example, ‘a kind-hearted soul in the shape of a lonely old man leaning on the window’) or employs particular types of figurative language such as metaphor or simile (for example, ‘like a hungry lion grabbing free meat’).

Students can be led in a sharing time once the reading has completed, where they reflect on their experiences reading their work aloud, and experiences of listening to others. What did they learn about language and their own writing through this process?

Supports and scaffolds can be adjusted for differing student abilities and confidence, particularly for students for whom English is an additional language/dialect.

If the activity is done regularly through writing units, students can build up reflections on the writing process in a writing journal.

Celebrating sentences

Hattie and Timperley (2007) remind us of the vital role of

feedback on student learning.

Building on the Quaker Share strategies, Celebrating Sentences is designed to:

- support the sharing of writing at the level of sentences in the classroom

- to draw attention to the way language creates meaning and effect

- to encourage students to feel empowered as writers.

This strategy is used when students are peer conferencing a piece of writing, such as an argumentative text.

They are asked to highlight two to three sentences in the paragraph, or paragraphs they are reading that they find convincing. Both students (writer and reader) are then tasked with identifying what makes these sentences convincing, and then applying this learning to another part of the text.

For example, the following sentence from a Year 8 persuasive essay on compulsory sport might be highlighted by the student writer’s peer:

Secondly, compulsory sport is a negative experience for students who are not good at sport.

Some students feel embarrassed, degraded, and belittled about their skill levels and might be bullied by their team mates because they aren’t very good at sport.

16% of students in America are overweight, they need to do some activity but compulsory sport is not the solution. A school psychologist called Emma says that for some students, sport is an ‘uncomfortable experience’. If students

feel bad about themselves then they might quit sport as adults which

will be bad for their health. This means that compulsory sport can have a bad impact on students’ wellbeing.

The questions students might ask each other are:

- Which words have an impact on the reader? They might notice the sensing verb

‘feel’ and evaluative adjectives embarrassed, degraded, and belittled which present negative feelings. - What might this mean for other sentences that are not as persuasive? They might notice

will be bad and

might be bullied to consider more effective use of modal verbs and intensifying or modal adverbs (for example, possibly, probably, certainly, definitely) to suggest the degree of likelihood or probability of the occurrence of feelings. The table below assists student to build verb groups in this and other activities.

Experimenting with modal verbs and modal adverbs (intensifiers)

| ‘Everyday language’ | More precise language with modal adverbs (intensifiers) | |

|---|---|---|

| low modality | might feel bad | might possibly experience discomfort or embarrassment or might possibly have an impact on student confidence |

| medium modality | will feel bad | will probably experience discomfort and embarrassment or would probably have a significant impact on student confidence |

| high modality | will absolutely feel bad | will definitely experience discomfort and embarrassment or would certainly have a significant impact on student confidence |

Students can write the sentences they are celebrating on a shared digital space (such as a word document or padlet.com). The teacher can then lead a discussion of the characteristics of the celebratory sentences. This can provide opportunities for the class to see and understand what makes successful writing in the particular genre being studied, such as the examples detailed below that explore the use of modality in persuasive texts.

Discussion of the example sentences could include discussion points such as the following:

- Modal verbs of different strength such as might, will, must can modulate the writer’s stance or position.

- Modal adverbs or intensifiers of different strength such as possibly, probably, certainly can also modulate the writer’s stance or position.

- More precise language choices such as ‘experience’ instead of ‘feel’, ‘discomfort’ or ‘embarrassment’ instead of ‘bad’ suggest a stronger sense of negative attitudes or feelings.

- Including a noun group such as ‘a significant impact on student confidence’ is more ‘written like’ or academic language and provides a sense of the author’s authority or expertise on the topic.

Identifying key vocabulary (writing)

Helping students to identify key words about their topic before they commence the writing process is an important way to build vocabulary.

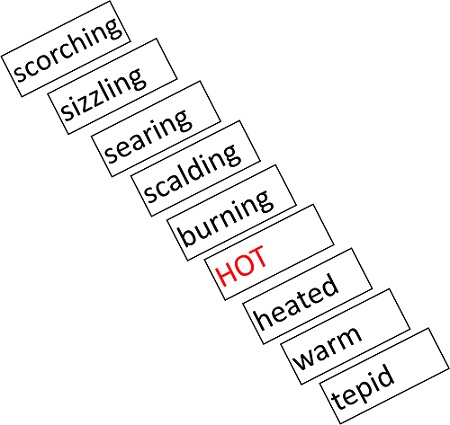

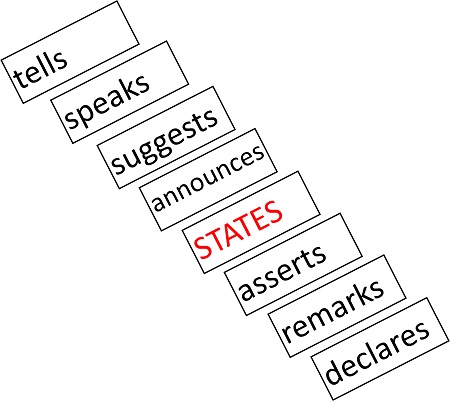

Word cline

A word cline is an effective strategy that helps students to reinforce their understanding of the meaning of words and to extend their vocabularies. The word cline comes from the Greek word clino – to slope.

A word cline, therefore, is a graded sequence of words whose meanings are arranged in a continuum that is usually shown on a sloping line. The purpose of the activity is to have students discuss and explore the subtle shifts in meaning that occur when language is arranged in a graduated manner. This strategy can be used in all forms of writing, including, narratives, imaginative and persuasive texts.

| Verb | walk | pace, tread, stroll, saunter, march, amble, hike, promenade |

| Adjective | hot | burning, scorching, blistering, sizzling, searing, broiling, warm, tepid, scalding, heated |

| Adverb | slowly | gradually, leisurely, unhurriedly, sluggishly, gently |

Word cline for the adjective ‘hot’

Word cline for the verb ‘states’

At the Year 7 level, word clines help students investigate how language works and prepare students for their own writing (VCELA371,

VCELY387).

Word clines for verbs are helpful scaffolds that assist students’ discussion of word choices and shades of meaning, setting them up well for textual analysis in the later secondary years (VCELA474).

Sentence starters (writing)

When students begin to write more sustained pieces of written work, one of the challenges they often face is being able to vary the language used to open new paragraphs.

Teachers can help students to experiment with their language, through the explicit teaching (HITS Strategy 3) of sentence starters. This strategy supports students to build their repertoire of text connectives so that they develop cohesion in their writing.

Using sentence starter lists

A useful way for students to learn to build sentence starters into their own work is to provide them with a list of words that relate specifically to the text type or genre they are creating.

The most appropriate text connectives to use are the ones that fit the purpose of the writing. For example, the text connectives in a narrative indication time are used to sequence events chronologically, often at the beginning of the sentence. For example, after that, after a while, then.

In an exposition, a range of text connectives might be used for different purposes. For example:

- additive, also, moreover; causative

- as a result, consequently, conditional/concessional

- otherwise, in that case, however, sequential

- to begin with, in conclusion; clarifying

- for instance, in fact, in addition.

For the purposes of this activity, focus on the text connectives that can be used at the beginning of sentences.

To clarify

- in other words

- in other words

- to put it another way

- for example

- for instance

- in particular

- in fact

- as a matter of fact

- namely

To show cause/result

- therefore

- then

- consequently

- as a consequence

- as a result

- accordingly

- in that case

- due to

- for that reason

To indicate time

- then

- next

- afterwards

- previously

- meanwhile

- later

- earlier

- finally

- in the end

To sequence ideas

- firstly

- to begin

- at this point

- then

- finally

- all in all

To add information

- furthermore

- also

- moreover

- likewise

- equally

- above all

- again

To concede

- in that case

- otherwise

- however

- besides

- despite

- still

- instead

(Adapted from Derewianka, Beverly. (2011) A New Grammar Companion for Teachers. NSW, PETA.)

In addition to highlighting text connectives, students can be taught about the ways in which dependent clauses and prepositional phrases are used at the beginning of sentences to create particular narrative effect.

For example, after a second of wondering, they ran through the door… In the enchanted forest on a magical land far, far away, three pixies were sleeping under a tree …In an exposition, passive voice might be used to foreground the object e.g. When the rainforests are burnt to make way for palm oil plantations, the orangutans’ habitat is destroyed.

Curriculum link for the above example:

VCELA414.

Supporting student spelling (reading and viewing, writing)

Developing spelling knowledge is best undertaken contextually, through the production of texts. The spelling strategies below, conducted in the context of meaningful interaction with texts, take a number of forms that increase in complexity, including strategies which develop knowledge at four levels:

- Phonological knowledge — knowledge of the sound structure of language.

- Visual knowledge — knowledge of the system of written symbols used to represent spoken language.

- Morphological knowledge — knowledge of the smallest parts of words that carry meaning.

- Etymological knowledge — knowledge of the origins of words (Oakley & Fellowes, 2016, p.6).

We might also translate this knowledge into simpler terms:

- Phonological strategies: how words sound.

- Visual strategies: how words look.

- Morphological strategies: how to find meaningful parts within words.

- Etymological strategies: how the origin of words determine spellings.

Teachers should consider how to incorporate these spelling strategies into the teaching of genre and text types, as a way of building and extending vocabulary.

While the Look, Say, Cover Write, Check (LSCWC) approach has dominated English classrooms for decades as the primary strategy for teaching spelling, research has found that this approach provides minimal transfer to later independent writing and that students lack the ability to use this strategy to generalise (Beckham-Hungler et al, 2003).

The memorisation of whole words from lists that are then assessed through weekly spelling tests does not represent best practice, and research has shown that successful spellers use a greater variety of strategies compared to poor spellers (Critten, Connelly, Dockrell & Walter, 2014).

Systematic instruction in spelling is important, however, it should take place in the context of general principles and sound policy towards writing.

In addition to

inquiry-based approaches to teach spelling, Winch et al. (2012) describe the following principles which should be kept in mind when supporting students to develop connections between spoken and written words:

- The language skills of reading, writing, listening and speaking are inextricably linked.

- The main responsibility of a teacher is to motivate students to write clearly over a wide range of text-types.

- Shared, guided and independent writing activities will help students to write more confidently.

- The teacher should assist where advice is most likely to be noticed and acted upon, namely at the individual student’s point of need.

- The teacher should encourage a habit of self-correcting when students write (p.329).

Segmenting

Phonological knowledge refers to knowledge about the sounds in language. It is an important part of learning to write (and read). As part of learning to spell, students need to develop phonological awareness, that is, the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate syllables, rhymes and individual sounds (phonemes) in increasingly complex words (VCELA475).

One way to improve spelling is through segmenting activities. Segmenting is the ability to split words into their separate speech sounds. Segmenting advances in complexity, from:

- sentence segmentation

- to syllable segmenting and blending

- to blending and segmenting individual sounds (phonemes).

It cannot be assumed that all students in the secondary years have successfully developed phonological knowledge, and secondary English teachers may find it useful to introduce sentence segmenting activities (below) before moving onto to more complex segmenting approaches.

Segmenting at the word level begins with an emphasis on syllables. Teachers should begin with one and two syllable words, asking students to sound-out aloud each syllable in a word (as in ‘to-pic’, ‘no-vel’, ‘po-em’). Students can be encouraged to clap as they complete this activity which will allow them to make stronger connections between individual sounds and syllables. Progression can be made by adding two-three syllable words, and so on.

For some students in secondary school, there might be a need to identify individual sounds (phonemes) in words and to provide support in blending sounds or using onset-rime activities to decode words.

Onset-rime activities involve breaking words into their onsets (consonants before the consonants), and the rime (everything left in the word).

For example, the rime «own» as in «down» could have different onsets to make words such as:

- fr-own

- t-own

- cl-own.

This use of segmenting, from the sentence to syllable to phoneme, will help develop phonological awareness and an understanding of the relationship between sounds and the alphabetic symbols that represent them in writing (phonics).

Visualisation

Visual, or orthographic, knowledge is the awareness of the symbols (letters or groups of letters) used to represent the individual sounds of spoken language in written form. To spell fluently, students also need to know about how written letters are arranged in English (VCELA384).

Two visual strategies which represent variations of Look, Say, Cover, Write, Check, have been devised by Westwood (1994) and develop visual knowledge. They are:

Variation 1:

- Look at the word.

- Say – make sure you know how to pronounce the word.

- Break the word into syllables.

- Write the word without copying.

- Check what you have written.

- Revise.

Variation 2:

- Select a difficult word.

- Pronounce the word slowly and clearly.

- Say each syllable of the word.

- Name the letters in the word.

- Write the word, naming each letter as you write.

These visual strategies can help students remember specific written words and word parts.

Grouping common morphemes

Morphemes represent the smallest meaningful units of language. Morphemes come in two forms.

Free morphemes that can stand alone with a specific meaning. For example, Catch, Cook, or Strong.

Bound morphemes cannot stand on their own and can only appear as part of another word. Prefixes and suffixes are examples of bound morphemes. Prefixes are bolted on to the front of a word to add specific meaning.

Prefixes can give a sense of order in time. For example, the prefix [fore-] in the words

- foresee

- foretell

- forewarn.

Fore- indicates a sense of something happening before the action described in the base word. To foresee is to see something before it happens.

Other English prefixes like [dis-] [de-] [mis-] and [un-] signal the opposite meaning to the word it is attached to (Hamawand, 2011).

We can see negative prefixes in words like:

- destabilise

- deconstruct

- dissimilar

- displease

- uncertain

- unrest

- misinterpret

- misshapen.

English spelling rule for adding prefixes

When you add a prefix to a base or root word, you can always just bolt it straight on. No need to change the spelling of the word it attaches to.

Dis + similar = dissimilar mis + shapen = misshapen un + necessary = unnecessary

Suffixes carry meaning and are bolted on to the end of a word where the combination of the base and the suffix forms a new word.

Suffixes also play an important role in the nominalisation of English words. Nominalisation refers to the process of turning a verb into a noun form.

Example, ‘Consideration of this issue is vital’ instead of ‘You should consider this issue’.

Nominal suffixes

Nominal suffixes are attached to the end of verbs or adjectives to form nouns.

For example, we can form nouns when we add the suffixes:

- [-al]

- [-ce]

- [-ion]

- [-ment].

We can see how verbs are nominalised by adding a nominal suffix in these word sums:

- celebrate + ion = celebration

- modulate + ion = modulation

- enjoy + ment = enjoyment.

We can see how adjectives are nominalised by adding a nominal suffix in these word sums:

- aware + ness = awareness

- appear + ance = appearance.

English spelling rule for adding suffixes

When you add a suffix to a word, you need to change the spelling if the word it attaches to ends in a vowel letter and the suffix also begins with a vowel letter.

For example, the verb ‘regulate’ can be nominalised by adding the suffix [-ion]. The spelling rule for adding suffixes determines that the final letter ‘e’ must be dropped before adding ‘ion’ as it begins with a vowel letter (a, e, I, o, u or y).

If the suffix begins with a consonant letter as in [-ment] or [-ness], you can always just bolt these suffixes onto the base word. For example, the verb ‘amaze’ can be nominalised by adding the suffix [-ment]. The spelling rule for adding suffixes determines it is bolted on to the base without dropping the final ‘e’, so we have ‘amazement’.

Working with morphemes teaches students to ‘look inside’ the word to find meaningful parts within the whole word (VCELA354). Working with students to group words that share common morphemes is an effective strategy for developing their morphological understandings (Herrington & Macken-Horarik, 2015).

Grouping common morphemes together provides an opportunity for students to make meaningful connections or links between words despite changes in sounds. For example, Herrington and Macken-Horarik explain how a grouping activity allowed the following words to be grouped:

- native

- nature

- natural

- nationwide

- nationality

- national

- naturalistic

- naturally.

All words shared the common root morpheme [nat-] (meaning source, birth or tribe) even though the [nat-] morpheme is spoken differently. For example, the morpheme [nat-] in ‘natural’ is spoken with a short vowel sound, and in the word ‘native’ it is spoken with a long /a/ sound.

This activity can also be conducted in reverse, with the teacher placing a target word on the whiteboard, for example, the word, remember, and asking students to identify the various morphemes.

Once the morpheme [-mem-] (meaning to call to mind) is identified, students are encouraged to brainstorm other words that share this morpheme, encouraging them to look inside words to find the meaningful parts. Word sums are an effective grouping activity to build understanding about how meaningful word structures (morphemes) combine to construct words and play a vital role in the English spelling system (Bowers & Cooke, 2012).

Here are some examples of word sums using the base word, construct:

- construct + s = constructs

- construct + ed = constructed

- construct + ing = constructing

- construct + ive = constructive

- construct + ion = construction

- de + construct = deconstruct

- de + construct + ion = deconstruction

- re + construct + ing = reconstructing

- re + construct + ed = reconstructed

- re + construct + ion = reconstruction.

Parts cards

Another strategy seeking to develop morphological knowledge is the parts card strategy.

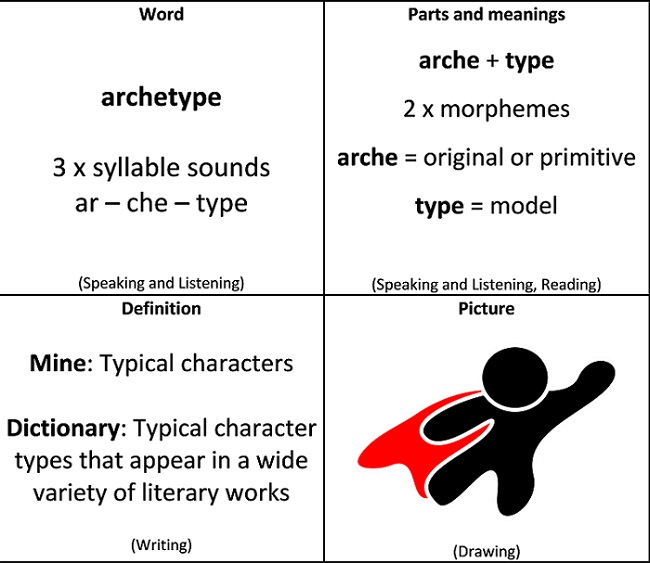

Stants’s (2013) parts card strategy is one way for teachers to introduce students to new vocabulary. The parts card strategy requires students to:

- dissect new vocabulary

- generate a meaning

- and then draw a diagram to demonstrate their understanding.

Zoski et al. (2018) have modified Stants’s parts card strategy to emphasise the language modes (reading, writing, speaking and listening). An example is below.

Image source: Pixabay.com

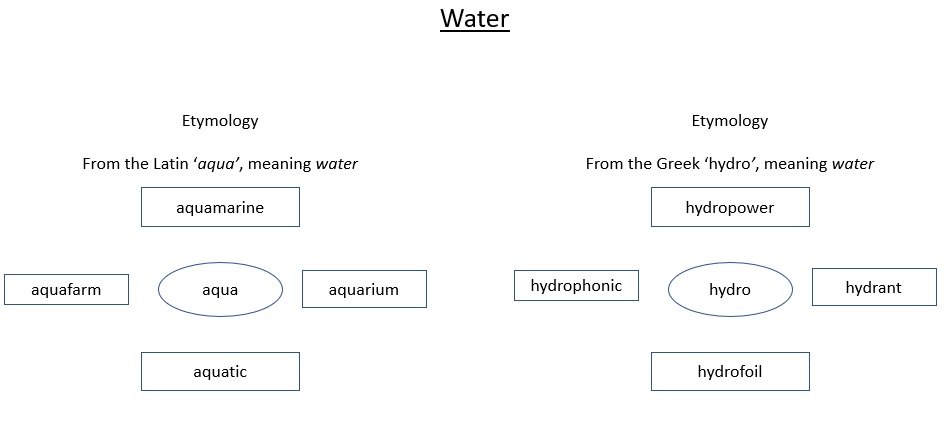

Word webs

Etymological knowledge refers to how the history and origins of words relate to their meaning and spelling. Knowing about the origin of these words is helpful to students when learning to spell them (VCELA384).

Devonshire, Morris, and Fluck (2013) describe a word web activity:

- begin with researching the historical origins of the target word

- place this at the top of the whiteboard

- Write the morpheme (smallest meaningful units of language) of the target word in the middle of the whiteboard

- students are encouraged to brainstorm other words that share the same morpheme.

For example:

Using and editing punctuation (writing, reading and viewing)

Punctuation is “the use of standard symbols, spaces, capitalisation and indentation to help the reader understand written text” (Wing Jan, 2009, p.37).

Punctuation “provides the conventional framework for sentence structure” to aid in meaning making.

Knowing how and when to use the most appropriate punctuation when writing is a skill that requires development over time. As students move through the secondary years of English, the explicit teaching (HITS Strategy 3) of punctuation continues to play a critical role in the way that students develop as writers.

Students can be shown examples of the ways that subtle changes to punctuation can drastically change the meaning of a sentence, such as the one below:

The teacher stood by the door and called the students’ names.

The teacher stood by the door and called the students names.

Discussions of punctuation are supported by an understanding of the impact that it has on meaning, and the potential for clarifying or confusing a reader. One of the most effective ways for students to improve their own punctuation use is through the drafting and editing of their own writing. One strategy to support this is through individual or peer reviews that target punctuation use.

Individual or peer reviews of punctuation use

Once the explicit teaching/revision of punctuation has been completed:

- teachers request students to make two copies of one piece of their own writing

- the other copy has its punctuation removed

- students read the version that has had the punctuation omitted and insert a new set of punctuation

- students compare the newly punctuated version to the original version

- in pairs, students discuss the two different versions of the same piece of writing. Through negotiation and discussion, students make decisions about the correct and most appropriate way to punctuate the piece.

Narrative: original version (with punctuation)

That morning Mark woke up early, the early morning sun was streaming through the open window. Mark did not groan, he did not struggle to get out of bed, for he knew exactly what he had to do, and his heart was thumping just thinking about it. He climbed out of bed and pulled on a tracksuit. The bitter outside air hit him like a brick wall, but he did not stumble. He put his hands in his pockets and stepped out onto the street. The day was just starting up, cars and trams drizzling down Flinders street. Mark joined the small group of people crossing the street, and while waiting there, thought carefully about the plans in his head. The crossing signal indicated go, and Mark walked slowly but purposefully across, and ducked into the coffee shop. He ordered his coffee, and then sat and waited. Mark checked the clock on the wall, he had exactly five minutes before Thaddeus’ train should arrive…

Narrative: clean version (no punctuation)

That morning Mark woke up early the early morning sun was streaming through the open window Mark did not groan he did not struggle to get out of bed for he knew exactly what he had to do and his heart was thumping just thinking about it He climbed out of bed and pulled on a tracksuit The bitter outside air hit him like a brick wall but he did not stumble he put his hands in his pockets and stepped out onto the street The day was just starting up cars and trams drizzling down Flinders street Mark joined the small group of people crossing the street and while waiting there thought carefully about the plans in his head The crossing signal indicated go and Mark walked slowly but purposefully across and ducked into the coffee shop he ordered his coffee and then sat and waited Mark checked the clock on the wall he had exactly five minutes before Thaddeus train should arrive

Curriculum links for the above example:

VCELA415,

VCELA445,

VCELY450,

VCELY480,

VCELA472.

Using feedback to increase the sophistication of student writing (writing, reading and viewing)

Writing demands in the secondary years increase significantly in complexity and sophistication (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Students can be explicitly taught how to create more sophistication in their writing through a range of approaches.

The examples below demonstrate the kind of feedback that teachers can provide students, focusing on two aspects of language:

Nominalisation

Nominalisation refers to the process of turning a verb into a noun form.

Example:

‘Consideration of this issue is vital’ instead of ‘You should consider this issue’.

It is a linguistic tool frequently used in many disciplines particularly when describing abstract ideas or making theoretical arguments. Nominalisation is less evident in spoken language but is a critical feature in written academic texts.

Compare the two examples below, taken from Derewianka and Jones (2016, p. 308):

Spoken example:

‘When plastic bags are made, toxic gases and other dangerous substances are released into the air and these by-products pollute the atmosphere and ruin water supplies.

Written example:

The production of toxic gases during the manufacture of plastic bags causes air and water pollution.

There are four clauses in the spoken example; these have been collapsed into one in the written example. As a result, the text is more dense and information is compressed. There is also a causal relationship between the production of plastic bags and the impact.

The following table (also called an anchor chart) was created by a Year 8 class as they worked on persuasive essays regarding the topic ‘Climate Change’ (VCELA397,

VCELA401,

VCELA415).

The class (initially led by teacher, and increasingly independently):

- identifies everyday phrases that could increase in sophistication

- brainstorms ways to nominalise these terms

- lists these on the chart

The anchor chart should be visible for the class to pool their ideas about changing every day phrases into nominalised, sophisticated language choices.

| Everyday language | Nominalised word choices |

|---|---|

| The climate is getting hotter |

Climate change global warming |

| People can’t agree about climate change… |

Disagreement about climate change… |

| Solve the problem | Find a workable solution |

| Human’s actions are making the issue worse | Human impact Human involvement |

| Scientists have told us why | Scientific explanation |

| Cutting down trees | Deforestation of areas |

The presence of the anchor chart in the classroom creates an additional scaffold to support students in providing peer feedback to one another. They can refer to the chart to identify ways that their peers can improve their work by making nominalised word choices.

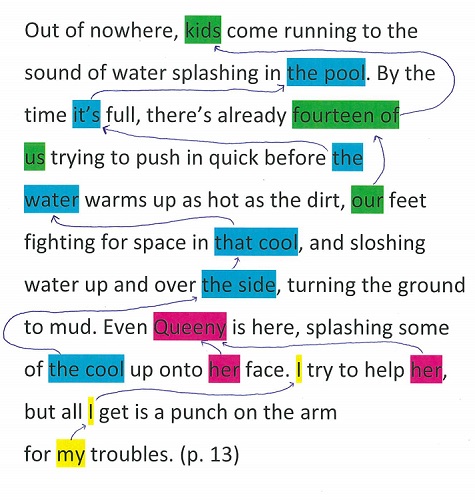

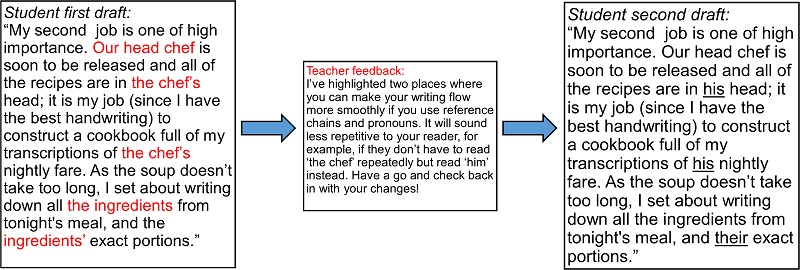

Creating reference chains

Reference chains refer ways in which links are made between items in a text to help the reader track meaning, for example, through the use of

pronouns or the definite article (the) or

demonstratives such as this, that, these.

To strengthen student understanding of reference chains and cohesive links, teachers can use a model text to demonstrate the interconnected ideas across a passage. This can begin at the paragraph level, in the case modelled below.

This example demonstrates how reference chains can be colour coded to show how they operate in a paragraph from Zana Fraillon’s The Bone Sparrow in a Year 8 class (VCELA414). It can also be modelled at the whole-of-text level to highlight how cohesive devices are employed in text, for example, when explicitly teaching the structure of websites in Year 7 (VCELA380).

In this example, sets of reference chains are highlighted in three different colours to show the three different sets of chains, and arrows show the linkage between the references.

Once students have had these features modelled to them, teachers can provide specific feedback to students on how to improve their writing by employing these language features, as seen in the student work sample below.

References

Beckham-Hungler, D., Williams, C., Smith, K., & Dudley-Marling, C. (2003). Teaching words that students misspell: Spelling instruction and young children’s writing. Language Arts, 80(4), 299–309.

Bowers, P. N., & Cooke, G. (2012). Morphology and the common core building students’ understanding of the written word. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 38(4), 31–35.

Critten, S., Connelly, V., Dockrell, J. E., & Walter, K. (2014). Inflectional and derivational morphological spelling abilities of children with Specific Language Impairment. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–10.

Dawson, C. (2009). Beyond checklists and rubrics: Engaging students in authentic conversations about their writing. The English Journal, 98(5), 66–71.

Derewianka, B. (2011). A new grammar companion for teachers. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association of Australia.

Derewianka, B., & Jones, P. (2016). Teaching language in context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Devonshire, V., Morris, P., & Fluck, M. (2013). Spelling and reading development: The effect of teaching children multiple levels of representation in their orthography. Learning and Instruction, 25, 85–94.

Hamawand, Z. (2011). Morphology in English: Word formation in cognitive grammar. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Herrington, M. H., & Macken-Horarik, M. (2015). Linguistically informed teaching of spelling: Toward a relational approach. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(2), 61¬–71.

Oakley, G., & Fellowes, J. (2016). A closer look at spelling in the primary classroom. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association of Australia.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content area literacy. Harvard Education Review, 78(1), 40–59.

Stants, N. (2013). Parts cards: Using morphemes to teach science vocabulary. Science Scope, 36(5), 58–63.

Westwood, P. (1994). Issues in spelling instruction. Special Education Perspectives, 3(1), 31–44.

Winch, G., Johnston, R., March, P., Ljungdahl, L., & Holliday, M. (2012). Literacy. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Wing Jan, L. (2009). Write ways: Modelling writing forms (3rd Ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Zoski, J.L., Nellenbach, K.M., & Erickson, K.A. (2018). Using morphological strategies to help adolescents decode, spell, and comprehend big words in science. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 40(1), 57–64.

______________________________________________________________

When you boil it down, vocabulary is one of the most important things you can learn. Communicating at higher levels in corporate america or even to higher (financial class) class individuals used to hearing certain words all the time.

In some circles if you don’t use certain words and use the correctly, you can be shunned as an outsider. One place this really holds true is in high earning job interviews. How you talk and what words you use can show your astute or a poser, words can convey intelligence and even class.

Years ago I came to realize that words are much more than just communication tools, they can make or break an article, a meeting, even a job interview.

I got a program called «Verbal Advantage» and it changed my life. Besides just teaching you all the powerful vocabulary commonly used by all classes (some specific to higher classes) they explain the entire history of the word, the proper pronunciation of the word, and how it’s used. You learn as you go adding more and more words to your vocabulary.

The system uses a tiered system where by you learn gradually and gradually the terminology your learning gets more complex. By the time you finish the course you not only know fluently the words, can say them and even explain how they came to be, but you will use them correctly and see your life change around you. I never thought vocabulary alone could change everything but it really can!

You also realize that using certain words, for example, in an article that’s supposed to appeal to several levels of people, you don’t use elusive words (elusive if you never heard them before). You save those for power emails (i.e. to a corporate body) and the like. You can also use them in different potency for different things to make yourself look pretty astute, and in reality- you are.

Good Luck out there!

______________________________________________________________

Word study, word work, and spelling…confused about the difference and why it matters in your upper elementary classroom?! These three types of word learning structures often get thrown around interchangeably in the upper elementary teaching world, but they have important differences in approach and purpose. You may have landed on this blog post as a new teacher who really wants to know what distinguishes each practice, as a veteran teacher who’s curious to see if our definitions match, or as someone who falls in between. While word study, word work, and spelling have quite a bit of crossover, there are also some fundamental differences that we should take into consideration.

I was always an A+ speller, but I had everything going for me in that department—I loved to read, my ability to memorize was fantastic, my enjoyment of all things school and my type-A personality allowed me to thrive on practice worksheets, I loved having my mom call words out to me to spell, and I gave myself my own spelling tests to make sure I would do well on the tests…heck, I probably even had index cards to help myself focus on any words with tricky spellings. How many of your students sound like that kind of kid?!

In recent years there has been a shift away from traditional spelling programs where students focus solely on memorizing a list of (possibly) random words in order to perform well on a spelling test. Teachers and parents alike often complain that students are able to perform well on spelling tests but continue to misspell words in their written work. It’s like cramming for a test and then forgetting much of the information once time has passed.

Before we get into my recommendations for an upper elementary word study/spelling program that works, let’s make sure we have a good understanding of the nuances of spelling, word study, and word work.

WHAT IS SPELLING?

Traditional spelling instruction focuses on learning to spell words correctly given a list of words. In upper elementary, how words end up on a students’ spelling list can run the gamut. The word list can be based on a spelling pattern, personalized based on a sight-word assessment, derived from books students are reading, come from content area vocabulary, or a combination of sources. Language Arts textbooks and literacy curriculums often include lists of spelling words and lessons for students to complete but they are often not based on developmental spelling levels or individual students’ needs.

In hopes of differentiating spelling lists, teachers sometimes have students choose half of their words from a class word list and half of their words from a “personal” list of words that students need to master.

While a spelling program can teach phonics and word pattern concepts, the focus is often on memorization, spelling tests, and moving on to new words the following week. Spelling activities often involve repeated activities and practice writing words so that students can spell them correctly when they are tested on them—think “three times each,” rainbow words, word pyramids, ABC order, and more as ways to make it fun for students to write their spelling words again and again.

WHAT IS WORD STUDY?

In word study programs, students are guided to discover and make generalizations about patterns in words and how words work. Word study aims to improve students’ ability to read words, spell words accurately, and understand the meaning of words, including how adding different word parts modify word meanings. “Studying” words is a foundational aspect of word study and moves away from a strict focus on memorizing how words are spelled.

For example, students participating in a word study block may be learning about words that end in -ck and -ke. Through reading, sorting, searching for, and writing words that fit in this particular category, students are guided to discover that most words ending in -ke make the long vowel sound, while most words ending in -ck make a short vowel sound. In word study, students move from noticing similarities and differences in word patterns, sounds, and spellings to being able to verbalize a common rule or way words with those patterns and sounds function.

While spelling words accurately is a goal of word study, so is applying the knowledge of word patterns to spell other words that also follow the spelling pattern; transferring their learning to spell new words is a key goal of word study.

Differentiation is another cornerstone of a true word study program. In classrooms where word study is implemented, students are assessed with a spelling inventory to see where they are in their understanding of phonics and word patterns. The inventory contains a variety of words and increases in complexity to identify students’ mastery of sound patterns and ability to represent the sounds they hear through spelling.

Based on the assessment, students are grouped by their developmental level. For example, students who don’t show a solid understanding of long vowel patterns would not be studying how prefixes and suffixes impact a word’s meaning in the scope of word study (although, the teacher may implement whole group lessons focused on Greek and Latin roots and students will surely encounter those kinds of words in content areas like science and social studies.)

Word study often involves tactile sorting of words on word cards where students group words based on spelling patterns and sounds. Students then document their word sorts by copying it down on paper. This practice helps students think about and come up with ideas about how the words work.

WHAT IS WORD WORK?

Word work is largely used with pre-readers and early readers in preschool and lower elementary grades with a focus on phonics, sight words, and spelling—all critical for our earliest readers! It consists of a variety of teacher modeling, hands-on activities, and games that encourage word building and word reading. In my experience, word work has usually been a component added into students’ guided reading time. Many lower grades teachers try to add a few minutes of word work at the start or end of most of their guided reading lessons.

Word work should bring to mind images of students building words and writing different words repeatedly. During word work, students may learn about word families like -at and -an. They can practice reading and writing new words by changing the beginning consonant (pat/mat/cat and fan/man/pan). Word work is also a time to help students memorize high frequency words that are key for developing as readers. Playing with words and manipulating parts of words is a key component of word work.

WHAT’S AN UPPER ELEMENTARY TEACHER TO DO?

I have found that a well balanced word-learning program has the best aspects of word study, word work, and spelling AND as the teacher, you should be well aware of your goals for whichever program you choose to implement.

I can’t not say this—word study/spelling time needs to be differentiated based on students’ developmental levels. If not, in my experience spelling time just feels like a punishment to some students and a waste of time for others. The days of having all students in a class or grade level working to master and spell the same word list should be a thing of the past for upper elementary classrooms. And, when your students’ assignments are based on their developmental level, they’ll be more eager to participate and have a growth mindset about their spelling and word attack abilities.

Next, we can use elements of word work to bring fun and engagement to our word study program. Games and activities can give students many opportunities to see and work with words and word patterns. These word-work-like experiences will naturally support our upper elementary students in making generalizations about spelling patterns, word pronunciations, and word meanings.

My ultimate recommendation for upper elementary teachers is to create an inquiry-based word study routine where the foundational goal is for students to learn to generalize the consistencies they notice in words in ways that help them become better readers and writers. This routine should incorporate 1-2 days of playing with words and sounds and 1-2 low-stress days that are focused on spelling words accurately. #teachersonamission!

Because I’ve realized that the hands-on FUN was missing from my word study routine, I’ve spent 2021 running down the long path of creating word study games and activities for all levels of word study. These games and centers are aligned to Words Their Way, but can complement any word study program where the focus is on word patterns and sounds. See what these are all about here! With the addition of board games, card games, spinners, and picture board activities, you are sure to find the spark of joy in word study that I’ve felt all these years!

Struggling to picture what this would look like on paper?! Don’t worry! I’ve got you covered in some upcoming posts about word study routines and schedules! Stay tuned! (Or, better yet, grab your FREE Word Study Terminology download and you’ll be updated when I publish new posts about word study!)

HELPFUL RESOURCES FOR UPPER ELEMENTARY WORD STUDY