In linguistics, morphology ([1]) is the study of words, how they are formed, and their relationship to other words in the same language.[2][3] It analyzes the structure of words and parts of words such as stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes. Morphology also looks at parts of speech, intonation and stress, and the ways context can change a word’s pronunciation and meaning. Morphology differs from morphological typology, which is the classification of languages based on their use of words,[4] and lexicology, which is the study of words and how they make up a language’s vocabulary.[5]

While words, along with clitics, are generally accepted as being the smallest units of syntax, in most languages, if not all, many words can be related to other words by rules that collectively describe the grammar for that language. For example, English speakers recognize that the words dog and dogs are closely related, differentiated only by the plurality morpheme «-s», only found bound to noun phrases. Speakers of English, a fusional language, recognize these relations from their innate knowledge of English’s rules of word formation. They infer intuitively that dog is to dogs as cat is to cats; and, in similar fashion, dog is to dog catcher as dish is to dishwasher. By contrast, Classical Chinese has very little morphology, using almost exclusively unbound morphemes («free» morphemes) and it relies on word order to convey meaning. (Most words in modern Standard Chinese [«Mandarin»], however, are compounds and most roots are bound.) These are understood as grammars that represent the morphology of the language. The rules understood by a speaker reflect specific patterns or regularities in the way words are formed from smaller units in the language they are using, and how those smaller units interact in speech. In this way, morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies patterns of word formation within and across languages and attempts to formulate rules that model the knowledge of the speakers of those languages.

Phonological and orthographic modifications between a base word and its origin may be partial to literacy skills. Studies have indicated that the presence of modification in phonology and orthography makes morphologically complex words harder to understand and that the absence of modification between a base word and its origin makes morphologically complex words easier to understand. Morphologically complex words are easier to comprehend when they include a base word.[6]

Polysynthetic languages, such as Chukchi, have words composed of many morphemes. For example, the Chukchi word «təmeyŋəlevtpəγtərkən», meaning «I have a fierce headache», is composed of eight morphemes t-ə-meyŋ-ə-levt-pəγt-ə-rkən that may be glossed. The morphology of such languages allows for each consonant and vowel to be understood as morphemes, while the grammar of the language indicates the usage and understanding of each morpheme.

The discipline that deals specifically with the sound changes occurring within morphemes is morphophonology.

History[edit]

The history of morphological analysis dates back to the ancient Indian linguist Pāṇini, who formulated the 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology in the text Aṣṭādhyāyī by using a constituency grammar. The Greco-Roman grammatical tradition also engaged in morphological analysis.[7] Studies in Arabic morphology, conducted by Marāḥ al-arwāḥ and Aḥmad b. ‘alī Mas’ūd, date back to at least 1200 CE.[8]

The linguistic term «morphology» was coined by August Schleicher in 1859.[a][9]

Fundamental concepts[edit]

Lexemes and word-forms[edit]

The term «word» has no well-defined meaning.[10] Instead, two related terms are used in morphology: lexeme and word-form. Generally, a lexeme is a set of inflected word-forms that is often represented with the citation form in small capitals.[11] For instance, the lexeme eat contains the word-forms eat, eats, eaten, and ate. Eat and eats are thus considered different word-forms belonging to the same lexeme eat. Eat and Eater, on the other hand, are different lexemes, as they refer to two different concepts.

Prosodic word vs. morphological word[edit]

Here are examples from other languages of the failure of a single phonological word to coincide with a single morphological word form. In Latin, one way to express the concept of ‘NOUN-PHRASE1 and NOUN-PHRASE2‘ (as in «apples and oranges») is to suffix ‘-que’ to the second noun phrase: «apples oranges-and». An extreme level of the theoretical quandary posed by some phonological words is provided by the Kwak’wala language.[b] In Kwak’wala, as in a great many other languages, meaning relations between nouns, including possession and «semantic case», are formulated by affixes, instead of by independent «words». The three-word English phrase, «with his club», in which ‘with’ identifies its dependent noun phrase as an instrument and ‘his’ denotes a possession relation, would consist of two words or even one word in many languages. Unlike most other languages, Kwak’wala semantic affixes phonologically attach not to the lexeme they pertain to semantically but to the preceding lexeme. Consider the following example (in Kwak’wala, sentences begin with what corresponds to an English verb):[c]

kwixʔid-i-da

clubbed-PIVOT—DETERMINER

bəgwanəmai-χ-a

man-ACCUSATIVE—DETERMINER

q’asa-s-isi

otter-INSTRUMENTAL—3SG—POSSESSIVE

«the man clubbed the otter with his club.»

(Notation notes:

- accusative case marks an entity that something is done to.

- determiners are words such as «the», «this», and «that».

- the concept of «pivot» is a theoretical construct that is not relevant to this discussion.)

That is, to a speaker of Kwak’wala, the sentence does not contain the «words» ‘him-the-otter’ or ‘with-his-club’ Instead, the markers —i-da (PIVOT-‘the’), referring to «man», attaches not to the noun bəgwanəma («man») but to the verb; the markers —χ-a (ACCUSATIVE-‘the’), referring to otter, attach to bəgwanəma instead of to q’asa (‘otter’), etc. In other words, a speaker of Kwak’wala does not perceive the sentence to consist of these phonological words:

i-da-bəgwanəma

PIVOT-the-mani

s-isi-t’alwagwayu

with-hisi-club

A central publication on this topic is the volume edited by Dixon and Aikhenvald (2002), examining the mismatch between prosodic-phonological and grammatical definitions of «word» in various Amazonian, Australian Aboriginal, Caucasian, Eskimo, Indo-European, Native North American, West African, and sign languages. Apparently, a wide variety of languages make use of the hybrid linguistic unit clitic, possessing the grammatical features of independent words but the prosodic-phonological lack of freedom of bound morphemes. The intermediate status of clitics poses a considerable challenge to linguistic theory.[12]

Inflection vs. word formation[edit]

Given the notion of a lexeme, it is possible to distinguish two kinds of morphological rules. Some morphological rules relate to different forms of the same lexeme, but other rules relate to different lexemes. Rules of the first kind are inflectional rules, but those of the second kind are rules of word formation.[13] The generation of the English plural dogs from dog is an inflectional rule, and compound phrases and words like dog catcher or dishwasher are examples of word formation. Informally, word formation rules form «new» words (more accurately, new lexemes), and inflection rules yield variant forms of the «same» word (lexeme).

The distinction between inflection and word formation is not at all clear-cut. There are many examples for which linguists fail to agree whether a given rule is inflection or word formation. The next section will attempt to clarify the distinction.

Word formation includes a process in which one combines two complete words, but inflection allows the combination of a suffix with a verb to change the latter’s form to that of the subject of the sentence. For example: in the present indefinite, ‘go’ is used with subject I/we/you/they and plural nouns, but third-person singular pronouns (he/she/it) and singular nouns causes ‘goes’ to be used. The ‘-es’ is therefore an inflectional marker that is used to match with its subject. A further difference is that in word formation, the resultant word may differ from its source word’s grammatical category, but in the process of inflection, the word never changes its grammatical category.

Types of word formation[edit]

There is a further distinction between two primary kinds of morphological word formation: derivation and compounding. The latter is a process of word formation that involves combining complete word forms into a single compound form. Dog catcher, therefore, is a compound, as both dog and catcher are complete word forms in their own right but are subsequently treated as parts of one form. Derivation involves affixing bound (non-independent) forms to existing lexemes, but the addition of the affix derives a new lexeme. The word independent, for example, is derived from the word dependent by using the prefix in-, and dependent itself is derived from the verb depend. There is also word formation in the processes of clipping in which a portion of a word is removed to create a new one, blending in which two parts of different words are blended into one, acronyms in which each letter of the new word represents a specific word in the representation (NATO for North Atlantic Treaty Organization), borrowing in which words from one language are taken and used in another, and coinage in which a new word is created to represent a new object or concept.[14]

Paradigms and morphosyntax[edit]

A linguistic paradigm is the complete set of related word forms associated with a given lexeme. The familiar examples of paradigms are the conjugations of verbs and the declensions of nouns. Also, arranging the word forms of a lexeme into tables, by classifying them according to shared inflectional categories such as tense, aspect, mood, number, gender or case, organizes such. For example, the personal pronouns in English can be organized into tables by using the categories of person (first, second, third); number (singular vs. plural); gender (masculine, feminine, neuter); and case (nominative, oblique, genitive).

The inflectional categories used to group word forms into paradigms cannot be chosen arbitrarily but must be categories that are relevant to stating the syntactic rules of the language. Person and number are categories that can be used to define paradigms in English because the language has grammatical agreement rules, which require the verb in a sentence to appear in an inflectional form that matches the person and number of the subject. Therefore, the syntactic rules of English care about the difference between dog and dogs because the choice between both forms determines the form of the verb that is used. However, no syntactic rule shows the difference between dog and dog catcher, or dependent and independent. The first two are nouns, and the other two are adjectives.

An important difference between inflection and word formation is that inflected word forms of lexemes are organized into paradigms that are defined by the requirements of syntactic rules, and there are no corresponding syntactic rules for word formation.

The relationship between syntax and morphology, as well as how they interact, is called «morphosyntax»;[15][16] the term is also used to underline the fact that syntax and morphology are interrelated.[17] The study of morphosyntax concerns itself with inflection and paradigms, and some approaches to morphosyntax exclude from its domain the phenomena of word formation, compounding, and derivation.[15] Within morphosyntax fall the study of agreement and government.[15]

Allomorphy[edit]

Above, morphological rules are described as analogies between word forms: dog is to dogs as cat is to cats and dish is to dishes. In this case, the analogy applies both to the form of the words and to their meaning. In each pair, the first word means «one of X», and the second «two or more of X», and the difference is always the plural form -s (or -es) affixed to the second word, which signals the key distinction between singular and plural entities.

One of the largest sources of complexity in morphology is that the one-to-one correspondence between meaning and form scarcely applies to every case in the language. In English, there are word form pairs like ox/oxen, goose/geese, and sheep/sheep whose difference between the singular and the plural is signaled in a way that departs from the regular pattern or is not signaled at all. Even cases regarded as regular, such as -s, are not so simple; the -s in dogs is not pronounced the same way as the -s in cats, and in plurals such as dishes, a vowel is added before the -s. Those cases, in which the same distinction is effected by alternative forms of a «word», constitute allomorphy.[18]

Phonological rules constrain the sounds that can appear next to each other in a language, and morphological rules, when applied blindly, would often violate phonological rules by resulting in sound sequences that are prohibited in the language in question. For example, to form the plural of dish by simply appending an -s to the end of the word would result in the form *[dɪʃs], which is not permitted by the phonotactics of English. To «rescue» the word, a vowel sound is inserted between the root and the plural marker, and [dɪʃɪz] results. Similar rules apply to the pronunciation of the -s in dogs and cats: it depends on the quality (voiced vs. unvoiced) of the final preceding phoneme.

Lexical morphology[edit]

Lexical morphology is the branch of morphology that deals with the lexicon that, morphologically conceived, is the collection of lexemes in a language. As such, it concerns itself primarily with word formation: derivation and compounding.

Models[edit]

There are three principal approaches to morphology and each tries to capture the distinctions above in different ways:

- Morpheme-based morphology, which makes use of an item-and-arrangement approach.

- Lexeme-based morphology, which normally makes use of an item-and-process approach.

- Word-based morphology, which normally makes use of a word-and-paradigm approach.

While the associations indicated between the concepts in each item in that list are very strong, they are not absolute.

Morpheme-based morphology[edit]

Morpheme-based morphology tree of the word «independently»

In morpheme-based morphology, word forms are analyzed as arrangements of morphemes. A morpheme is defined as the minimal meaningful unit of a language. In a word such as independently, the morphemes are said to be in-, de-, pend, -ent, and -ly; pend is the (bound) root and the other morphemes are, in this case, derivational affixes.[d] In words such as dogs, dog is the root and the -s is an inflectional morpheme. In its simplest and most naïve form, this way of analyzing word forms, called «item-and-arrangement», treats words as if they were made of morphemes put after each other («concatenated») like beads on a string. More recent and sophisticated approaches, such as distributed morphology, seek to maintain the idea of the morpheme while accommodating non-concatenated, analogical, and other processes that have proven problematic for item-and-arrangement theories and similar approaches.

Morpheme-based morphology presumes three basic axioms:[19]

- Baudouin’s «single morpheme» hypothesis: Roots and affixes have the same status as morphemes.

- Bloomfield’s «sign base» morpheme hypothesis: As morphemes, they are dualistic signs, since they have both (phonological) form and meaning.

- Bloomfield’s «lexical morpheme» hypothesis: morphemes, affixes and roots alike are stored in the lexicon.

Morpheme-based morphology comes in two flavours, one Bloomfieldian[20] and one Hockettian.[21] For Bloomfield, the morpheme was the minimal form with meaning, but did not have meaning itself.[clarification needed] For Hockett, morphemes are «meaning elements», not «form elements». For him, there is a morpheme plural using allomorphs such as -s, -en and -ren. Within much morpheme-based morphological theory, the two views are mixed in unsystematic ways so a writer may refer to «the morpheme plural» and «the morpheme -s» in the same sentence.

Lexeme-based morphology[edit]

Lexeme-based morphology usually takes what is called an item-and-process approach. Instead of analyzing a word form as a set of morphemes arranged in sequence, a word form is said to be the result of applying rules that alter a word-form or stem in order to produce a new one. An inflectional rule takes a stem, changes it as is required by the rule, and outputs a word form;[22] a derivational rule takes a stem, changes it as per its own requirements, and outputs a derived stem; a compounding rule takes word forms, and similarly outputs a compound stem.

Word-based morphology[edit]

Word-based morphology is (usually) a word-and-paradigm approach. The theory takes paradigms as a central notion. Instead of stating rules to combine morphemes into word forms or to generate word forms from stems, word-based morphology states generalizations that hold between the forms of inflectional paradigms. The major point behind this approach is that many such generalizations are hard to state with either of the other approaches. Word-and-paradigm approaches are also well-suited to capturing purely morphological phenomena, such as morphomes. Examples to show the effectiveness of word-based approaches are usually drawn from fusional languages, where a given «piece» of a word, which a morpheme-based theory would call an inflectional morpheme, corresponds to a combination of grammatical categories, for example, «third-person plural». Morpheme-based theories usually have no problems with this situation since one says that a given morpheme has two categories. Item-and-process theories, on the other hand, often break down in cases like these because they all too often assume that there will be two separate rules here, one for third person, and the other for plural, but the distinction between them turns out to be artificial. The approaches treat these as whole words that are related to each other by analogical rules. Words can be categorized based on the pattern they fit into. This applies both to existing words and to new ones. Application of a pattern different from the one that has been used historically can give rise to a new word, such as older replacing elder (where older follows the normal pattern of adjectival superlatives) and cows replacing kine (where cows fits the regular pattern of plural formation).

Morphological typology[edit]

In the 19th century, philologists devised a now classic classification of languages according to their morphology. Some languages are isolating, and have little to no morphology; others are agglutinative whose words tend to have many easily separable morphemes; others yet are inflectional or fusional because their inflectional morphemes are «fused» together. That leads to one bound morpheme conveying multiple pieces of information. A standard example of an isolating language is Chinese. An agglutinative language is Turkish. Latin and Greek are prototypical inflectional or fusional languages.

It is clear that this classification is not at all clearcut, and many languages (Latin and Greek among them) do not neatly fit any one of these types, and some fit in more than one way. A continuum of complex morphology of language may be adopted.

The three models of morphology stem from attempts to analyze languages that more or less match different categories in this typology. The item-and-arrangement approach fits very naturally with agglutinative languages. The item-and-process and word-and-paradigm approaches usually address fusional languages.

As there is very little fusion involved in word formation, classical typology mostly applies to inflectional morphology. Depending on the preferred way of expressing non-inflectional notions, languages may be classified as synthetic (using word formation) or analytic (using syntactic phrases).

Examples[edit]

Pingelapese is a Micronesian language spoken on the Pingelap atoll and on two of the eastern Caroline Islands, called the high island of Pohnpei. Similar to other languages, words in Pingelapese can take different forms to add to or even change its meaning. Verbal suffixes are morphemes added at the end of a word to change its form. Prefixes are those that are added at the front. For example, the Pingelapese suffix –kin means ‘with’ or ‘at.’ It is added at the end of a verb.

- ius = to use → ius-kin = to use with

- mwahu = to be good → mwahu-kin = to be good at

sa- is an example of a verbal prefix. It is added to the beginning of a word and means ‘not.’

- pwung = to be correct → sa-pwung = to be incorrect

There are also directional suffixes that when added to the root word give the listener a better idea of where the subject is headed. The verb alu means to walk. A directional suffix can be used to give more detail.

- -da = ‘up’ → aluh-da = to walk up

- -di = ‘down’ → aluh-di = to walk down

- -eng = ‘away from speaker and listener’ → aluh-eng = to walk away

Directional suffixes are not limited to motion verbs. When added to non-motion verbs, their meanings are a figurative one. The following table gives some examples of directional suffixes and their possible meanings.[23]

| Directional suffix | Motion verb | Non-motion verb |

|---|---|---|

| -da | up | Onset of a state |

| -di | down | Action has been completed |

| -la | away from | Change has caused the start of a new state |

| -doa | towards | Action continued to a certain point in time |

| -sang | from | Comparative |

See also[edit]

- Morphome (linguistics)

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Für die lere von der wortform wäle ich das wort « morphologie», nach dem vorgange der naturwißenschaften […] (Standard High German «Für die Lehre von der Wortform wähle ich das Wort «Morphologie», nach dem Vorgange der Naturwissenschaften […]», «For the science of word-formation, I choose the term «morphology»….»

- ^ Formerly known as Kwakiutl, Kwak’wala belongs to the Northern branch of the Wakashan language family. «Kwakiutl» is still used to refer to the tribe itself, along with other terms.

- ^ Example taken from Foley (1998) using a modified transcription. This phenomenon of Kwak’wala was reported by Jacobsen as cited in van Valin & LaPolla (1997).

- ^ The existence of words like appendix and pending in English does not mean that the English word depend is analyzed into a derivational prefix de- and a root pend. While all those were indeed once related to each other by morphological rules, that was only the case in Latin, not in English. English borrowed such words from French and Latin but not the morphological rules that allowed Latin speakers to combine de- and the verb pendere ‘to hang’ into the derivative dependere.

References[edit]

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ Anderson, Stephen R. (n.d.). «Morphology». Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. Macmillan Reference, Ltd., Yale University. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Aronoff, Mark; Fudeman, Kirsten (n.d.). «Morphology and Morphological Analysis» (PDF). What is Morphology?. Blackwell Publishing. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Brown, Dunstan (December 2012) [2010]. «Morphological Typology» (PDF). In Jae Jung Song (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Typology. pp. 487–503. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199281251.013.0023. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Sankin, A.A. (1979) [1966]. «I. Introduction» (PDF). In Ginzburg, R.S.; Khidekel, S.S.; Knyazeva, G. Y.; Sankin, A.A. (eds.). A Course in Modern English Lexicology (Revised and Enlarged, Second ed.). Moscow: VYSŠAJA ŠKOLA. p. 7. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Wilson-Fowler, E.B., & Apel, K. (2015). «Influence of Morphological Awareness on College Students’ Literacy Skills: A path Analytic Approach». Journal of Literacy Research. 47 (3): 405–32. doi:10.1177/1086296×15619730. S2CID 142149285.

- ^ Beard, Robert (1995). Lexeme-Morpheme Base Morphology: A General Theory of Inflection and Word Formation. Albany: NY: State University of New York Press. pp. 2, 3. ISBN 0-7914-2471-5.

- ^ Åkesson 2001.

- ^ Schleicher, August (1859). «Zur Morphologie der Sprache». Mémoires de l’Académie Impériale des Sciences de St.-Pétersbourg. VII°. Vol. I, N.7. St. Petersburg. p. 35.

- ^ Haspelmath & Sims 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Haspelmath & Sims 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Word : a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. I︠U︡. Aĭkhenvalʹd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-511-48624-1. OCLC 704513339.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Anderson, Stephen R. (1992). A-Morphous Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 74, 75. ISBN 9780521378666.

- ^ Plag, Ingo (2003). «Word Formation in English» (PDF). Library of Congress. Cambridge. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- ^ a b c

Dufter and Stark (2017) Introduction — 2 Syntax and morphosyntax: some basic notions in Dufter, Andreas, and Stark, Elisabeth (eds., 2017) Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG - ^ Emily M. Bender (2013) Linguistic Fundamentals for Natural Language Processing: 100 Essentials from Morphology and Syntax, ch.4 Morphosyntax, p.35, Morgan & Claypool Publishers

- ^ Van Valin, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., van Valin Jr, R. D., LaPolla, R. J., & LaPolla, R. J. (1997) Syntax: Structure, meaning, and function, p.2, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin; Sims, Andrea D. (2002). Understanding Morphology. London: Arnold. ISBN 0-340-76026-5.

- ^ Beard 1995.

- ^ Bloomfield 1933.

- ^ Hockett 1947.

- ^ Bybee, Joan L. (1985). Morphology: A Study of the Relation Between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 11, 13.

- ^ Hattori, Ryoko (2012). Preverbal Particles in Pingelapese. pp. 31–33.

Further reading[edit]

- Aronoff, Mark (1993). Morphology by Itself. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262510721.

- Aronoff, Mark (2009). «Morphology: an interview with Mark Aronoff» (PDF). ReVEL. 7 (12). ISSN 1678-8931. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06..

- Åkesson, Joyce (2001). Arabic morphology and phonology: based on the Marāḥ al-arwāḥ by Aḥmad b. ʻAlī b. Masʻūd. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 9789004120280.

- Bauer, Laurie (2003). Introducing linguistic morphology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: SGeorgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-343-4.

- Bauer, Laurie (2004). A glossary of morphology. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Bloomfield, Leonard (1933). Language. New York: Henry Holt. OCLC 760588323.

- Bubenik, Vit (1999). An introduction to the study of morphology. LINCOM coursebooks in linguistics, 07. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-570-2.

- Dixon, R. M. W.; Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y., eds. (2007). Word: A cross-linguistic typology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Foley, William A (1998). Symmetrical Voice Systems and Precategoriality in Philippine Languages (Speech). Voice and Grammatical Functions in Austronesian. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1947). «Problems of morphemic analysis». Language. 23 (4): 321–343. doi:10.2307/410295. JSTOR 410295.

- Fabrega, Antonio; Scalise, Sergio (2012). Morphology: from Data to Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Katamba, Francis (1993). Morphology. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-10356-5.

- Korsakov, Andrey Konstantinovich (1969). «The use of tenses in English». In Korsakov, Andrey Konstantinovich (ed.). Structure of Modern English pt. 1.

- Kishorjit, N; Vidya Raj, RK; Nirmal, Y; Sivaji, B. (December 2012). Manipuri Morpheme Identification (PDF) (Speech). Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on South and Southeast Asian Natural Language Processing (SANLP). Mumbai: COLING.

- Matthews, Peter (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42256-6.

- Mel’čuk, Igor A (1993). Cours de morphologie générale (in French). Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Mel’čuk, Igor A (2006). Aspects of the theory of morphology. Berlin: Mouton.

- Scalise, Sergio (1983). Generative Morphology. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Singh, Rajendra; Starosta, Stanley, eds. (2003). Explorations in Seamless Morphology. SAGE. ISBN 0-7619-9594-3.

- Spencer, Andrew (1991). Morphological theory: an introduction to word structure in generative grammar. Blackwell textbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16144-9.

- Spencer, Andrew; Zwicky, Arnold M., eds. (1998). The handbook of morphology. Blackwell handbooks in linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18544-5.

- Stump, Gregory T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: a theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge studies in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78047-0.

- van Valin, Robert D.; LaPolla, Randy (1997). Syntax : Structure, Meaning And Function. Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

- Lecture 7 Morphology in Linguistics 001 by Mark Liberman, ling.upenn.edu

- Intro to Linguistics – Morphology by Jirka Hana, ufal.mff.cuni.cz

- Morphology by Stephen R. Anderson, part of Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, cowgill.ling.yale.edu

- Introduction to Linguistic Theory — Morphology: The Words of Language by Adam Szczegielniak, scholar.harvard.edu

- LIGN120: Introduction to Morphology by Farrell Ackerman and Henry Beecher, grammar.ucsd.edu

- Morphological analysis by P.J.Hancox, cs.bham.ac.uk

What is Word Formation?

Word formation process is subject of morphology where we learn how new words are formed. In linguistics, word formation process is the creation of a new word by making changes in existing words or by creating new words. In other words, it refers to the ways in which new words are made on the basis of other words.

Different Forms of Word Formation

Word Formation process is achieved by different ways to create a new word that includes; coinage, compounding, borrowing, blending, acronym, clipping, contraction, backformation, affixation and conversion.

Compounding

Compounding is a type of word formation where we join two words side by side to create a new word. It is very common type of word formation in a language. Some time we write a compound word with a hyphen between two words and some time we keep a space and sometime we write them jointly. All these three forms are common in all languages.

Common examples of word compounding are:

· Part + time = part-time

· Book + case = bookcase

· Low + paid = low-paid

· Door + knob = doorknob

· Finger + print = fingerprint

· Wall + paper = wallpaper

· Sun + burn = sunburn

· Text + book = textbook

· Good + looking = good-looking

· Ice + cream = Ice-cream

Borrowing

In word formation process, borrowing is the process by which a word from one language is adapted for use in another language. The word that is borrowed is called a borrowing, a loanword, or a borrowed word. It is also known as lexical borrowing. It is the most common source of new words in all languages.

Common Examples of borrowed words in English language are:

· Dope (Dutch)

· Croissant (French)

· Zebra (Bantu)

· Lilac (Persian)

· Pretzel (German)

· Yogurt (Turkish)

· Piano (Italian)

· Sofa (Arabic)

· Tattoo (Tahitian)

· Tycoon (Japanese)

Blending

Blending is the combination of two separate words to form a single new word. It is different from compounding where we add two words side by side to make a new word but in blending we do not use both words in complete sense but new/derived word has part of both words e.g. word smog and fog are different words and when we blend them to make a new word, we use a part of each word to make a new word that is smog. We took first two letters from first word (sm) from smoke and last two (og) from fog to derive a new word smog.

Some more examples of blending are:

· Smoke + murk=smurk

· Smoke + haze= smaze

· Motel (hotel + motor)

· Brunch (breakfast + lunch )

· Infotainment ( information + entertainment)

· Franglais ( French + English)

· Spanglish (Spanish + English )

.

Abbreviations

Abbreviation is a process where we create a new word by making a change in lexical form of a word keeping same meaning. There are three main types of abbreviations.

1. Clipping / Shortening / Truncation

2. Acronyms / Initialism

3. Contraction

Clipping / Shortening / Truncation

Clipping is the type of word formation where we use a part of word instead of whole word. This form of word formation is used where there is a long/multi-syllable word and to save time we use a short one instead of that long word e.g. the word advertisement is a long word and we use its short form ad (ads for plural form) instead of whole word.

Here are some examples of clipping:

· Ad from advertisement

· Gas from gasoline

· Exam from examination

· Cab from cabriolet

· Fax from facsimile

· Condo from condominium

· Fan from fanatic

· Flu from Influenza

· Edu from education

· Gym from gymnasium

· Lab from laboratory

Acronyms / Initialism

An acronym is a word or name formed as an abbreviation from the initial letters in a phrase or a multi syllable word (as in Benelux). The initials are pronounced as new single words. Commonly derived word are written in upper case e.g. NATO.

Some common examples of acronyms are:

· CD is acronym of compact disk

· VCR is acronym of video cassette recorder

· NATO is acronym of North Atlantic Treaty Organization

· NASA is acronym of National Aeronautics and Space Administration

· ATM is acronym of Automatic Teller Machine

· PIN is acronym of Personal Identification Number

Some time the word is written in lower case (Initial letter capital when at start of sentence)

· Laser is acronym of Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation

· Scuba is acronym of Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus

· Radar is acronym of Radio Detecting And Ranging

Contraction

A contraction is a word formed as an abbreviation from a word. Contractions are abbreviations in which we omit letters from the middle of a word or more than one words.

Some common contractions are below:

· Dr is from Doctor.

· St is from Saint.

· He’s from He is.

· I’ve is from I have.

Affixation

Affixation is the word formation process where a new word is created by adding suffix or prefix to a root word. The affixation may involve prefixes, suffixes, infixes. In prefixes, we add extra letters before root word e.g. re+right to make a new word rewrite. In suffix, we add some extra letters with a base/root word e.g. read+able. In infixes, the base word is changed in its form e.g. the plural of woman is women that creates new word “women”.

1. Prefixes: un+ plug = unplug

2. Suffixes: cut + ie = cutie

3. Infixes: man + plural = men

Zero-derivation (Conversion)

Zero-derivation, or conversion, is a derivational process that forms new words from existing words. Zero derivation, is a kind of word formation involving the creation of a word from an existing word without any change in form, which is to say, derivation using only zero. Zero-derivation or conversion changes the lexical category of a word without changing its phonological shape. For example, the word ship is a noun and we use it also as a verb. See below sentences to understand it.

1. Beach hotel has a ship to enjoy honeymoon.

2. Beach hotel will ship your luggage in two days.

In first sentence, the word ship is a noun and in second sentence the word ship (verb) is derived from the action of ship (noun) that transports luggage, so the word ship (verb) has meaning of transportation.

Backformation

Backformation is the word formation process where a new word is derived by removing what appears to be an affix. When we remove last part of word (that looks like suffix but not a suffix in real) from a word it creates a new word.

Some very familiar words are below:

· Peddle from peddler

· Edit from editor

· Pea from pease

Coinage / Neologism

It is also a process of word formation where new words (either deliberately or accidentally) are invented. This is a very rare process to create new words, but in the media and industry, people and companies try to surpass others with unique words to name their services or products.

Some common examples of coinage are: Kodak, Google, Bing, Nylon etc.

Eponyms

In word formation process, sometime new words are derives by based on the name of a person or a place. Some time these words have attribution to a place and sometime the words are attributes to the things/terms who discover/invent them. For example, the word volt is electric term that is after the name of Italian scientist Alessandro Volta.

Some common examples of eponyms are:

· Hoover: after the person who marketed it

· Jeans: after a city of Italy Genoa

· Spangle: after the person who invented it

· Watt: after the name of scientist James Watt

· Fahrenheit: after the name of German scientist Gabriel Fahrenheit

2.1. Morphology: definition.

The

notion of morpheme.

Morphology

(Gr. morphe – form, and logos – word) is a branch of grammar that

concerns itself with the internal structure of words and

peculiarities of their grammatical categories and their semantics.

The study

of Modern English morphology consists of four main items,

(1) general

study of morphemes and types of word-form derivation,

(2) the system of parts of

speech,

(3) the

study of each separate part of speech, the grammatical categories

connected with it, and its syntactical functions.

The

morpheme

may be defined as an elementary meaningful segmental component of the

word. It is built up by phonemes and is indivisible into smaller

segments as regards its significative function.

Example:

writers

can be divided into three morphemes:

(1) writ-,

expressing the basic lexical meaning of the word,

(2) —er-,

expressing the idea of agent performing the action indicated by the

root of the verb,

(3) —s,

indicating number, that is, showing that more than one person of the

type indicated is meant.

Two or more

morphemes may sound the same but be basically different, that is,

they may be homonyms.

Thus the -er

morpheme indicating the doer of an action as in writer

has a homonym — the morpheme -er

denoting the comparative degree of adjectives and adverbs, as in

longer.

There may

be zero

morphemes,

that is, the absence of a morpheme may indicate a certain meaning.

Thus, if we compare the words book

and books,

both derived from the stem book-,

we may say that while books

is characterised by the –s

morpheme indicating a plural form, book

is characterised by the zero morpheme indicating a singular form.

Traditional

classification of morphemes is based on the two basic criteria:

-

positional

– the location of the marginal

morphemes

(периферийные

морфемы)

in relation to the central

ones

(центральные

морфемы) -

semantic/functional

– the correlative contribution (соотносительный

вклад)

of the morphemes to the general meaning of the word.

According

to this classification, morphemes are divided into:

-

root-morphemes

(roots)

– express the concrete, ‘material’ (насыщенная

конкретным

содержанием,

вещественная)

part of the meaning of the word.

The roots

of notional words are classical lexical

morphemes.

-

affixal

morphemes (affixes) – express

the specificational (спецификационная)

part of the meaning of the word.

This

specification can have lexico-semantic (лексическая)

and grammatico-semantic (грамматическая)

character.

The affixal

morphemes include:

1) prefixes

2) suffixes

Prefixes

and lexical suffixes have word-building functions, and form the stem

of the word together with the root.

3)

inflexions

(флексия)/grammatical

suffix

(Blokh)

The

morpheme serves to derive a grammatical form; it has no lexical

meaning of its own and expresses different morphological categories.

The

abstract complete morphemic model of the common English word is the

following: prefix + root + lexical suffix + inflection/grammatical

suffix.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Morphology

“It is the study of how words are formed.”

Some morphemes can’t be used independently, they are called “bound morphemes.” Here we have such morphemes as e.g. although = al+though, fallen = fall+en, ignoble = ig+noble. In all above examples each one has two morphemes ‘al’ is one and ‘though’ is another morpheme but the morphemes ‘al’, ‘en’, ig’ can’t be used separately whereas ‘though’, ‘fall’, ‘noble’ are used independently and they are called “free morphemes”

Bound morphemes are used for prefixation, suffixation and affixation. Sometimes they change the sense of the word e.g. “impossible” ‘ignoble’ here ‘im’ & ‘ig’ change positive sense of word ‘possible’, noble into negative sense they come under ‘Derivational Morphology’ and ‘Inflectional Morphology’

”Derivational affixes” often involve a change of class. Derivational prefixes don’t always change the function of the word to which they are prefixed e.g. here ‘return’(v) = prefix + turn (v), enjoy (v) = prefix + joy (N) here morphemes ‘re’ and ‘en’ are used as prefixes which make new words not always changing he function of he word.

But commonly occurring suffixes always change the class of word to which they are suffixed e.g. Here the word “quickly” = quick+suffix the word quick is an ‘adj’ but when we add ‘ly’ it becomes an ‘adverb’ and he word ‘engagement’ = engage + suffix “engage” is a ‘verb’ but with the addiction of ‘ment’ it becomes a ‘noun’.

”Inflectional suffixes” never involve a change of class. In nouns, inflection marks plurality in regular nouns e.g. here ‘s’ is used to make two morpheme as ‘village’, posts, here ‘s’ marks plurality in regular nouns-village, post irregular nouns often form their plurals by a vowel change e.g. here we see the word ‘women’ it becomes plural by a vowel change from ‘a’-woman to ‘e’-women.

With regard to verbs, inflectional suffixes are used to indicate present tense present participle as here he word eating = (v)eat+ing, seeing = (v)see+ing.

Whereas with irregular verbs, past tense and past participle are often signaled by a vowel change or a vowel change+suffix e.g. here in he word ‘gave’ then in a change of vowel ‘I’ give to ‘a’ – gave.

I have discussed here some aspects of morphology & now I would deal with this section involving lexicology.

“Lexicology is the study of words what do we mean by word?” a better approach to defining words is to acknowledge that there is no one totally satisfactory definition but that we can isolate four of the most frequently implied meanings of “word”: he orthographic, the morphological word, the lexical word and the semantic word. A morphological word is a unique form and considers only form not meaning but lexical word comprehends the various forms of items which are closely related by meaning e.g. here ‘hold, ‘held’ ‘holding’ are three morphological words but only one lexical word. Similarly a semantic word involves distinguishing between items which may be morphological identical but differ in meaning e.g. here the word “back” has two distinct meaning: ‘to return to he sample lace’––go back and a part of body––clap him on he back. But they are the same morphological word.

Word Formation

The comment type of word-formation is called “compounding”: joining two words together to form a third compounding frequently involves two nouns e.g. here ‘bulldog’ is formed by joining two noun –– bull+dog and stoneflag = stone(n)+flag(n). Other parts of speech can also combine to form new words e.g. here ‘empty feeling’ = empty(adj)+feeling(v) and “go back” = go(verb)+back(adverb).

Word Class

“To sort words into classes according to he way they function” word can function in many different ways e.g. here the word ‘rush’ is used as a noun in “They yelled for he rush of killing” and as a verb in:

“He would place himself to rush through he other attackers”

We can distinguish a number of word classes as nouns, determiners, pronouns, adjectives, verb, adverb, prepositions, conjunctions and exclamations. Nouns ‘A noun is defined as the name of a person, place or thing e.g. here we have Anselmo, Anjustin, Knines, villaconejos determiner. “It is an adjective like word which precedes both adjective and nouns e.g. ‘he has no better feeling’ here determine ‘no’ precedes both adj(beter) and noun (feeling).

There are three main kinds of determiners:

(1) articles as here we have ‘the feeling, a sack, an engagement

(2) demonstratives as here we have ‘that year’, ‘this manage’, ‘those villages’ etc

(3) possessives as here are ‘his head, his hand, his teeth, his mouth, his fists.

Also Study:

Strong and Weak Forms

1 Morphology, derivation, parts of speech

1.1 Morphology, word-formation

The term morphology consists of two parts: μορφή (‘form, shape‘) and λόγος (‘word, doctrine’), therefore morphology can be understood as a science that deals with forms such as cell morphology, phytomorphology, geomorphology etc.

The unit (object) of the study of linguistic morphology is a word whose form is understood to be a structure whose components are morphemes or complexes of morphemes.

In the traditional structural linguistics approach to the language the following are divided:

- the sound plane (sounds, phonemes) — phonetics, phonology,

- the plane of the building elements consisting of the words (morphs and morphemes) — morphematics (morphemics),

- the plane of words or word forms — morphology, lexicology,

- the plane of collocation and sentence — syntax,

- the text plane — text linguistics.

Elements of the lower planes consist of elements of higher planes, e.g. sentences consist of words. The plane of the building elements, which consist of words, examines the linguistic discipline morphematics (morphemics). The smallest, non-separable language units that act as building blocks of words and carry some lexical or grammatical meaning (or have a certain function) and which are repeated at least in two words or verbal forms are called morphs.

The boundary between the two morphs, which are part of the same word, is called a morphemic seam (we will mark it a dash): вод-а, вод-н-ый, на-вод-н-ени-е.

A set of morphs of the same kind, which have the same lexical or grammatical significance (or the same function) and which are similar to their formal structure, are called morphemes. Morpheme is an abstract unit that is realized through one of its morphs, e.g.: ног-а, нож-к-а, без-ног-ий. Concrete morphs -ног- [ног], -нож- [нож], -ног- [ног’] are realising here morpheme with a lexical meaning „одна из двух нижних конечностей человека, а также одна из конечностей птиц, некоторых животных“. The morphs belonging to such a set (which form one morpheme) are referred to as variants of the given morpheme or as an alomorphs, in other words -ног- [ног], -нож- [нож], -ног- [ног’] are the alomorphs of the morpheme -ног- with a lexical meaning „одна из двух нижних конечностей человека, а также одна из конечностей птиц, некоторых животных“.

Morph(eme)s, from which Russian words and grammatical word forms are composed, are usually divided into root word and affixes. Root morph(eme)s (root) are the central type of morph(eme)s and carry the main lexical meaning of the whole word or grammatical form of word, that every word has a root morf(eme): вод-а, жив-ой, трав-а, мног-о, пис-а-ть, глав-н-ый, мой. Affixes are morphemes that are located in a word in front of a root morph(eme)s or after it:

- Prefixes are located in front of the root, e. g.: под-писать, супер-герой, с-делать.

- Suffixes are found after the root or between the root and the ending, e. g.: ум-н-ый, дом-ик, красн-еньк-ий.

- Postfixes for certain types of words or grammatical forms can be attached to the so-called absolute end, i.e. behind a case, gender or personal inflexion or suffix, e. g.: умываться, кто-нибудь.

- Interfixes, which are used to join the front and rear composite members into a new word, in Russian most often -o-, -e-, e.g.: пар-о-ход, земл-е-трясение, вод-о-провод, лес-о-заготовки.

- Inflection (ending, inflectional morph(eme)s), in Russian they are morphemes whose change is accompanied by a change in morphological gender, numbers, case and persons, e. g.: стен-а, стен-ы, стен-е…; нов-ая, нов-ый, нов-ое, нов-ые; пиш-у, пиш-ешь, пиш-ем…, пиш-ут. Inflexion morph(eme)s are at the end of a word or grammatical form, after which only postfixes can be found in Russian, e. g.: -ся, -сь, -те, -то, -либо, -нибудь: стро-ит-ся, занимал-а-сь, ид-ём-те, как-ой-то.

Prefixes and suffixes can also be divided into:

- word-forming (derivation), which specify, modify, change the main lexical meaning of a word or word form, e.g.: дом – дом-ик („маленький дом“), писать – пере-писать („написать заново, иначе“);

- form-building (derivation of word forms), which express grammatical meanings (grammatical categories) and can only be used for flexible word types, e.g. case inflections of nouns (вод-а, вод-ы, вод-е), verb suffix of past time -л- (чит-а-л, чит-а-л-а, чит-а-л-о, чит-а-л-и).

Form-building morph(eme)s in Russian can be realized using so-called null morphs (morphological zero, mark Ø), in other words formally unrecognized morph, e.g. столØ, стол-а, стол-у or учительØ, учител-я, учител-ю, where in the nominative case the ending of a masculine gender is not expressed formally (i.e. by letter or special sound), but in other cases the ending is expressed on a formal level. If the word does not decline or conjugate, we can not speak of any null morphs at its end, e.g. in the words радио, хаки, какаду, Сочи, Брно, бордо, but in words such весело, улыбаясь we can talk about the final suffixes/postfixes: весел-о (suffix -о-), улыб-а-я-сь (postfix -сь).

The stem of a word or word form is the part of it that remains after separation of inflection (ending) or inflection with postfix -те. Morphs of other postfixes are part of a word or word form, e.g.: stem of word form пишется is пиш…ся, stem of word form чья-то is /ч’j/…то. Such stems are called intermittent in the Russian grammatical tradition.

Another branch associated with the structure of the word and its separation into morphs is word-forming (derivation) that deals with word-motivated words, i.e. words whose meaning and pronunciation are influenced in other words by the same root.

The term word-forming motivation refers to the relationship between two words with the same root, the relationship between the two words being of a dual nature:

- the meaning of one word is determined by the meaning of the second word (дом – домик „маленький дом“, победить – победитель „тот, кто победил“);

- the meaning of the two words is similar / the same, but each word of the pair is another part of speech (бежать — бег, белый — белизна, быстрый — быстро).

Words with the same root that do not meet the above requirements are not found in the word-motivation relationship, e.g.: the word домик and домище, but дом – домик, дом – домище are already in relation to word-forming motivation, while one of the words pair is motivating (underlying word), the second word is motivated. Features of a motivated word are as follows:

- If both words have a different lexical meaning, the motivated word is the one whose stem is longer (whether from formal or phonemic point of view): горох — горошина, писать — написать, есть — съесть.

- If both words have a different lexical meaning, but the same/similar formal page, motivated is a word whose semantics is determined over the meaning of the first word: химия – химик („тот, кто занимается химией“), художник – художница („женщина-художник“).

- In pairs verb — noun, adjective — noun motivated word is the noun: косить — косьба, выходить — выход, атаковать — атака, красный — краснота, синий — синь; in the pair adjective — adverb motivated is a word with a longer stem (q. v. point a): вчера – вчерашний.

- Stylistically colored words can not be motivating if they have a stylistically neutral adjective, e.g.: гуманитарный – гуманитар (colloquial), технический – техник (colloquial).

The underlying (motivating) word in relation to the next word may be motivated, e. g.: the word учитель in the pair with the word учительница is underlying, but in relation to the word учить is motivated. Such words form derivation chains (word-forming chains): учить → учитель → учительница. The derivation chain consists of words with the same root, which are related to motivation. The first member of the derivation chain is an unmotivated word, all other members of the derivation chain are determined by their distance from the first non-motivated word (so-called motivation degree):

старый → стареть (I) → устареть (II) → устарелый (III) → устарелость (IV)

The words of the second and the higher motivation degree can be motivated by the words of the previous motivation degree, e.g.: преподавать → преподаватель → преподавательский, where the word преподавательский can be motivated both by the word преподаватель and the word преподавать.

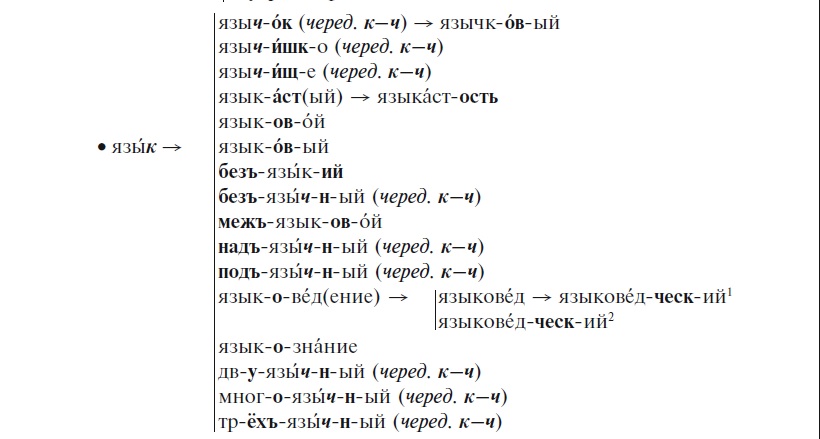

Another important term in the field of morphematics is a family of words, which means a group of words with the same root, which is organized on the basis of its motivation. The first word (vertex) of the family of words can be an unmotivated word. A family of words can also be defined as a series of derivation chains with the same first non-motivated word.

Family of words or derivation chains can be found in Russian-language vocabulary, e.g.:

- ГУРКОВА, И. В.: Морфемно-словообразовательный словарь. Как растёт слово? (1–4 классы). Москва: АСТ-ПРЕСС КНИГА, 2012. 192 с. ISBN 978–5-462–01047–7.

- ПОПОВА, Т. В., ЗАЙКОВА, Е. С.: Морфемно-словообразовательный словарь русского языка (5–11 классы). Москва: АСТ-ПРЕСС КНИГА, 2012. 272 с. ISBN 978–5-462–00922–8.

- ТИХОНОВ, А. Н.: Словообразовательный словарь русского языка: в 2 томах (около 145000 слов). Москва: Русский язык, 1985. 854 с.

- ТИХОНОВ, А. Н.: Новый словообразовательный словарь русского языка для всех, кто хочет быть грамотным. Москва: АСТ, 2014. 639 с. ISBN 978–5-17–082826–5.

Ways of word formation in Russian

I Ways of derivation words having one motivating root (stem)

1 Suffixation (suffixal way of word formation)

New words are created using suffixes that perform a classification function and classify words into certain paradigm, so new words created by the same suffix usually belong to the same paradigm (pattern), e.g.: учить — учи-тель, писать — писа-тель, both new words (учитель, писатель) have the same declension (учитель/писатель, без учителя/без писателя, к учителю/к писателю etc.).

Other examples of sufixation: вода — вод-н-ый, стол — стол-ик, три — три-жды.

The suffix may be null morpheme, e.g.: выходить — выход, синий — синь, задирать — задира, проезжать — проезжий.

2 Prefixation (prefixal way of word formation)

New words are created using prefixes, e.g.: дедушка — прадедушка, огромный — преогромный, завтра — послезавтра, герой — супергерой.

3 Postfixation (postfixal way of word formation)

New words are created by word-forming postfixes. Postfixes in Russian may be form-building (e.g.: -те in the imperative forms пишите, пойте; -ся/-сь in forms of passive voice Дом строится рабочими) and word-forming (-ся/-сь, -то, -либо, -нибудь): переписывать — переписываться (postfix — ся has a word-forming meaning of reciprocity), кто-то / что-либо / где-нибудь (postfixes -то, -либо, -нибудь have the word-forming meaning of uncertainty).

Prefixes and postfixes, unlike suffixes, attach to the whole word, not to the root, so the words created by prefixing or postfixing belong to the same word type and paradigm as an underlying word.

4 Mixed ways

- prefixal sufixal way of word formation (the suffix may be null morpheme): море – приморье, новый – по-новому, стол – застольный, рука – безрукий;

- prefixal postfixal way of word formation: бежать – разбежаться, гулять – нагуляться;

- sufixal postfixal way of word formation: гордый – гордиться, нужда – нуждаться.

5 Substantivation of adjectives and participles (semantic way of word formation)

E.g.: больной (больной ребёнок) – больной (Доктор принял пять больных), заведующий (Иван Петрович, заведующий отделением контроля, сегодня не придёт на работу) – заведующий (Заведующий кафедрой пришёл на работу к восьми утра).

II Ways of derivation words that have more than one motivating root (stem)

1 Composition

New words are created by compounding a few roots (stems), with the last (supporting) component equal to the whole word, the previous part(s) being equal to the stem. A derivation morpheme is an interfix, the order of the components is fixed, the accent is the only one, and is usually located on the last (supporting) component of the word: первый, источник – первоистóчник; половина, обернуться – полуобернýться; слепой, глухой, немой – слепоглухонемóй; чешский, русский — чешско-рýсский. The interfix can be null morpheme, e.g.: царь-пушка.

2 Mixed ways (suffixal compounding way of word formation)

New words are created by a combination of composition (compounding) and suffixation (which may be null morpheme): один, рука – однорукий; хлеб, резать – хлеборез; разный, язык — разноязычный.

3 Coalescence

New words are created based on the word combination with parataxis or governmen: лишённый ума – умалишённый; ребёнок, долго играющий на улице… – долгоиграющий; растворимый, быстро – быстрорастворимый.

4 Abbreviation

New words come from the first letters of words, from the first syllables of words, by combining one part of the word with the whole word, or combining the beginning of the first word and the end of the second word: США (Соединённые Штаты Америки), ЕС (Европейский Союз), вуз (высшее учебное заведение), сбербанк (сберегательный банк), физкультура (физическая культура), педфак (педагогический факультет). The words resulting from the abbreviation are inflected, but the abbreviations США, ЕС are uninflected.

Задания

1

Разделите слова на морфемы, определите, при помощи каких морфем было образовано данное слово:

2

Выделите корневые алломорфы.

а) рука, ручной, безрукий,

б) сонный, сон, сна,

в) земля, земной, земельный,

г) любить, люблю, влюблённый,

д) свет, свеча, освещение,

е) треск, трещина, треснуть.

3

Определите значения омонимичных корней и распределите слова на группы, учитывая значение корня, от которого данное слово образовано. Укажите словообразовательный способ.

а) Дорога, дóрого, дорожать, дорожка, дорогой, дорожный.

б) Зарисовка, рисинка, рисовать, рисовод, рисовый, рисунок.

в) Выкуп, выкупаться, купить, купальник, купля, купать, покупка, покупатель, купальщик.

4

Приведённые ниже слова распределите в зависимости от того, есть ли в них словообразовательный аффикс либо формообразующий.

знал, писатель, быстрее, котёнок, говорить, шелковистый, добрейший, плáча, переделать, наилучший, ближний, ошейник.

5

Определите, в каких словах конечные -а, -о, -е, -и, -ей являются суффиксом, окончанием или входят в состав корня:

6

Определите, какое слово из пары является мотивированным (производным), а какое мотивирующим (производящим):

строитель – строить, жéмчуг – жемчýжина, верно – верный, журналист – журналистка, новизнá – новый, добротá – добрый, сýхость – сухой, брóнза – брóнзовый, газета – газéтный, двигать – движение.

7*

Разделите слова на морфемы. Докажите, что Вы правы, подбирая другие формы слова, родственные слова или слова, построенные по аналогичной модели.

Образец

| выпускной | -пуск- | – | корень (пускать, пусковой, пуск); |

| вы- | – | приставка (выпрямить, выплатить); | |

| -н- | – | суффикс (вкусный, снежный); | |

| -ой | – | окончание (выпускн-ого, выпускн-ые). |

- переводчик

- приземлиться

- бесшумный

- ледник

- водопад

- подарок

- проигрывать

8*

Найдите по пять примеров слов к каждому словообразовательному способу русского языка.

9*

Работая со словообразовательными словарями русского языка, найдите словообразовательные гнёзда следующих слов:

- писать,

- читать,

- думать,

- учить,

- быть,

- виноград,

- вкус,

- голова,

- дочь,

- забота,

- много,

- здесь,

- вода,

- газета,

- новый,

- друг

Какие словообразовательные способы представлены в этих словообразовательных гнёздах?

10*

Прочитайте главу «Активные процессы в словообразовании» из учебника Н. С. Валгиной «Активные процессы в современном русском языке». При помощи каких продуктивных аффиксов в современном русском языке образуются названия лиц (в т. ч. названия лиц, образованные от корней (основ) иностранного происхождения)? Каковы особенности аббревиации в современном русском языке? Приведите примеры.