Within

the domain of syntax two levels should be distinguished: that of

phrases and that of sentences.

The

phrase can generally be defined as a combination of two or more words

which is a grammatical unit but is not an analytical form of some

word. The constituent elements of a phrase may belong to any part of

speech. A word-combination can also be defined as a compound

nominative unit of speech which is semantically global and

articulated.

The

difference between a phrase and a sentence is a fundamental one. A

phrase is a means of naming some phenomena or processes, just as a

word is. Each component of a phrase can undergo grammatical changes

while a sentence is a unit with every word having its definite form.

A change in the form of one or more words would produce a new

sentence.

Grammar

has to study the

aspects of phrases which spring from the grammatical peculiarities of

the words making up the phrase, and of the syntactical functions

of the phrase as a whole, while lexicology has to deal with the

lexical meaning of the words and their semantic groupings. For

example from

the grammatical point of view the two phrases

read

letters and

invite

friends are

identical (the

same pattern verb +

noun

indicating the object of the

action).

Phrases

can be divided according

to their function in the sentence into:

(1)

those

which

perform the function of one or more parts of the sentence (predicate,

or predicate and object, or predicate and adverbial

modifier, etc.)

(2)

those

which do not perform any such function

but whose function is equivalent to that of a preposition, or

conjunction, and which are equivalents

of those parts of speech.

1.3. Syntagmatic Connections of Words.

Words

in an utterance form various syntagmatic connections with one

another:

-

syntagmatic

groupings of notional words alone,

Such

groups (notional phrases) have self-dependent nominative destination,

they denote complex phenomena and their properties (semi-predicative

combinations): a

sudden trembling; a soul in pain; hurrying along the stream;

strangely familiar; so sure of their aims.

-

syntagmatic

groupings of notional words with functional words,

Such

combinations (formative phrases) are equivalent to separate words by

their nominative function: with

difficulty; must finish; but a moment; and Jimmy; too cold; so

unexpectedly.

They are contextually dependent (synsemantism).

-

syntagmatic

groupings of functional words alone.

They

are analogous to separate functional words and are used as connectors

and specifiers of notional elements:

from out of; up to; so that; such as; must be able; don’t let’s.

Combinations

of notional

words

fall into two mutually opposite types:

1)

combinations of words related to one another on an equal rank

(equipotent

combinations)

2)

combinations of words which are syntactically unequal (dominational

combinations)

Equipotent

connection

is realised with the help of conjunctions (syndetically), or without

the help of conjunctions (asyndetically):

prose and poetry; came and went; on the beach or in the water; quick

but not careless; —

no

sun, no moon; playing, chatting, laughing; silent, immovable, gloomy;

Mary’s, not John’s.

The

constituents of such combinations form coordinative consecutive

connections.

Alongside

of these, there exist equipotent connections of a non-consecutive

type. In such combinations a sequential element is unequal to the

foregoing element in its character of nomination connections is

classed as (cumulative connections): agreed,

but reluctantly; satisfied, or nearly so.

Dominational

connection

is effected in such a way that one of the constituents of the

combination is principal (dominating/headword) and the other is

subordinate (dominated/adjunct, adjunct-word, expansion).

Dominational

connection can be both consecutive

and cumulative:

a

careful observer; an observer, seemingly careful; definitely out of

the point;

out

of the point, definitely; will be helpful in any case will be

helpful;

at

least, in some cases.

The

two basic types of dominational connection are:

-

bilateral

(reciprocal, two-way) domination (in predicative connection of

words); -

monolateral

(one-way) domination (in completive connection of words).

The

predicative connection

of words, uniting the subject and the predicate, builds up the basis

of the sentence. The nature of this connections is reciprocal (the

subject dominates the predicate and vice versa).

Such

word combinations are divided into:

-

complete

predicative combinations (the subject + the finite verb-predicate); -

incomplete

predicative/semi-predicative/potentially-predicative combinations (a

non-finite verbal form + a substantive element): for

the pupil to understand his mistake; the pupil’s understanding his

mistake;

the

pupil understanding his mistake.

Monolateral

domination is considered as subordinative since the syntactic status

of the whole combination is determined by the head-word:

a nervous wreck. astonishingly beautiful.

The

completive connections fall into two main divisions:

-

objective

connections -

qualifying

connections.

Objective

connections

reflect the relation of the object to the process. By their form

these connections are subdivided into:

-

non-prepositional;

-

prepositional.

From

the semantico-syntactic point of view they are classed as:

-

direct

(the immediate transition of the action to the object); -

indirect

or oblique (the indirect relation of the object to the process).

Direct

objective connections are non-prepositional, the preposition serving

as an intermediary of combining words by its functional nature.

Indirect objective connections may be both prepositional and

non-prepositional.

Further

subdivision of objective connections is realised on the basis of

subcategorising the elements of objective combinations, and first of

all the verbs; thus, we recognise objects of immediate action, of

perception, of speaking, etc.

Qualifying

completive connections

are divided into

-

attributive

(an

enormous appetite; an emerald ring; a woman of strong character, the

case for the prosecution);

They

unite a substance with its attribute expressed by an adjective or a

noun.

-

adverbial:

-

primary

(the verb + its adverbial modifiers):

to talk glibly, to come nowhere; to receive (a letter) with

surprise; to throw (one’s arms) round a person’s neck; etc -

secondary

(the non-verbal headword expressing a quality + its adverbial

modifiers):

marvellously becoming; very much at ease; strikingly alike; no

longer oppressive; unpleasantly querulous; etc.

-

Completive

noun combinations are directly related to whole sentences

(predicative combinations of words): The

arrival of the train → The train arrived. The baked potatoes →

The potatoes are baked. The gifted pupil → The pupil has a gift.

Completive

combinations of adjectives and adverbs (adjective-phrases and

adverb-phrases) are indirectly related to predicative constructions:

utterly

neglected — utter neglect — The neglect is utter; very carefully

— great carefulness — The carefulness is great; speechlessly

reproachful — speechless reproach

— The reproach is speechless.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

A phrase is a combination of 2 or more words which is a gram. unit, i.e. there exists definite syntagmatic & syntactic relation between the words and the phrase is not supposed to be an analytical form of some word. The constituent elements of the phrase may belong to diff. parts of speech. If there is no semantic, syntactic relation, then it’s not a phrase: He took it badly (phrase), He took it bad (not a phrase). There is a specific type of phrase called syntactic construction. Syntactic constructions are those word-combinations which serve as a separate part of the sentence usually represented by 1 word. It is supposed to display some kind of predicative relation. We saw him cross the street (We saw – predicative relation, him cross – syntactic construction. |The difference between a sentence & a phrase is: 1) they have different functions; 2) a phrase can undergo grammatical changes without destroying itself: write letters – wrote letters – will write letters – it’s 1 phrase. BUT Last year he wrote a lot of letters to our friends – He writes a lot of letters – these are diff. sentences. |Sentence is a predicative unit, its function is predication. It’s a minimum synt. unit used in the communicative speech acts, built up according to some definite structural & intonational patterns & possessing some properties (categories) of the sentence, such as predicativity, modality, temporality, communicativity. |Structurally sentences fall into 2 major groups: 1) simple; 2) composite. |Simple have only 1 predicative relation, i.e. 1 subject & 1 predicate: Children jump and run in the street. |Composite may be compound & complex. |Compound consist of clauses, minimum 2 coordinate clauses; in complex sent-s 1 clause is principal, another 1 – subordinate. |In the speech sent-s do not occur separately, they’re supposed to be connected both semantically-topically & syntactically. These groups of words form textual unities & the process is called cumulation. Units of speech are cumulemes. |These groups may also be called complex syntactic unities or supra-phrasal unities. In the written speech they’re called paragraphs which have their own internal organization, they’re characterized by predicativity & modality. Paragraphs are connected into bigger units – texts. Paragraph groupings are cumulated into whole texts.

25. Syntagmatic relations in syntax. Syntactic relations & syntactic connections

Syntagmas are parts which the sentence may be broken into. Syntactic relations may be of 2 kinds: 1) equipotent (between words related to 1 another on equal basis)=coordinate; 2) dominational (between syntactically unequal words)=subordinate. In the case of equipotent relation the words in the phrase aren’t modified with 1 another, but the 2nd word is modifier of the other. |According to the nature of the headword in the dominational word-combinations phrases can be subdivided into: noun phrases (good friend), verb phrases (to go quickly), pronominal phrases (for him to go), adjectival phrases (very nice), adverbial phrases (very well). Synt.relations have their own connections. Equipotent relations have 2 types of connections: 1) syndetic (deals with conjunctions and, but, or); 2) asyndetic (realised through comma: no moon, no stars). Dominational have 4 types: 1) agreement (concord) – the headword & the adjunct must have the same grm.form: this girl – these girls; 2) government – subordinate word is used in the form required by the headword but not coinciding to it: We invited him to the party (not he); 3) attachment (adjoinment) – there must exist some syntactic relations between words: to run quickly (not brightly); 4) enclosure – 1 element of the phrase is enclosed between the elements of the other which is usually headword: the then president.

27. Predicative word-combinations. Primary and secondary predication. Infinitival, participial and gerundial construction, their function in the sentence

Predicative word-combinations are those consisting of N+V and displaying some kind of predicative relation (the relation between subject and predicate of the phrase) man writes-man wrote. If this noun & verb in predicative phrase coincide with subject & predicate of the sentence this type of predication is called primary. If it isn’t the case our phrase will present secondary nomination: The lessons over(secondary),everybody went(primary predication) home. The Nominative Absolute Participial Construction is a construction in which the participle stands in predicate relation to a noun in the common case or a pronoun in the nominative case; the noun or pronoun is not the subject of the sentence. The door and window of the vacant room being open, we looked in. It is used in the function of an adverbial modifier. It can be an adverbial modifier: (a)of time (b)of cause (c)of attendant circumstances. (d)of condition. The Nominative Absolute Construction is used in the function of an adverbial modifier of time or attendant circumstances. In the function of an adverbial modifier of time this construction is rendered in Russian by an adverbial clause. Breakfast over, he went to his counting house. The Objective Participial Construction is a construction in which the participle is in predicate relation to a noun in the common case or a pronoun in the objective case. In the Objective Participial Construction Participle 1 Indefinite Active or Participle II is used. In the sentence this construction has the function of a complex object. Occasionally the meaning of the construction is different: it may show that the person denoted by the subject of the sentence experiences the action expressed by the participle. The Subjective Participial Construction is a construction in which the participle (mostly Participle I) is in predicate relation to a noun in the common case or a pronoun in the nominative case, which is the subject of the sentence. The peculiarity of this construction is that it does not serve as one part of the sentence: one of its component parts has the function of the subject, the other forms part of a compound verbal predicate.

The Objective-with-the-infinitive Construction is a construction in which the infinitive is in predicate relation to a noun in the common case or a pronoun in the objective case. In the sentence this construction has the function of a complex object, The Subjective Infinitive Construction (traditionally called the Nominative-with-the-Infinitive Construction) is a construction in which the infinitive is in predicate relation to a noun in the common case or a pronoun in the nominative case. The peculiarity of this construction is that it does not serve as one part of the sentence: one of its component parts has the function of the subject, the other forms part of a compound verbal predicate. Edith is said to resemble me. The for-to- Infinitive Construction is a construction in which the infinitive is in predicate relation to a noun or pronoun preceded by the preposition for. The construction can have different functions in the sentence. It can be:1. Subject (often with the introductory it). 2. Predicative. 3. Complex object. 4. Attribute. 5. Adverbial modifier; (a) of purpose. (b) of result. Predicative constructions with the gerund. Like all the verbals the gerund can form predicative constructions, i. e. constructions in which the verbal element expressed by the gerund is in predicate relation to the nominal element expressed by a noun or pronoun. I don’t like your going off without any money. The nominal element of the construction can be expressed in different ways.1. If it denotes a living being it may be expressed: (a) by a noun in the genitive case or by a possessive pronoun, b) by a noun in the common case.2. If the nominal element of the construction denotes a lifeless thing, it is expressed by a noun in the common case (such nouns, as a rule, are not used in the genitive case) or by a possessive pronoun. I said something about my clock being slow. 3. The nominal element of the construction can also be expressed by a pronoun which has no case distinctions, such as all, this, that, both, each, something. I insist on both of them coming in time. Again Michael… was conscious of something deep and private stirring within himself.

|

Функция спроса населения на данный товар Функция спроса населения на данный товар: Qd=7-Р. Функция предложения: Qs= -5+2Р,где… |

Аальтернативная стоимость. Кривая производственных возможностей В экономике Буридании есть 100 ед. труда с производительностью 4 м ткани или 2 кг мяса… |

Вычисление основной дактилоскопической формулы Вычислением основной дактоформулы обычно занимается следователь. Для этого все десять пальцев разбиваются на пять пар… |

Расчетные и графические задания Равновесный объем — это объем, определяемый равенством спроса и предложения… |

The phrase is traditionally considered an independent syntactic unit, fundamentally different from the sentence. It appears in the language for nominative purposes. A complex name bearing in itself the same nominative function that a word has, is a phrase.

The sentence and the phrase — how to distinguish them?

The difference between the word-combination and the word does not need an explanation. The very name of the term indicates it. And how does the phrase differ from the sentence? First of all, it is a combination of word and word form, the implementation of the obligatory and typically optional faculties. In «Russian grammar-80» the phrase is understood as a semantic-grammatical model of word spreading.

The proposal is an extremely complex and multifaceted unit. Behind each of them are 3 samples: formal, semantic and communicative (pragmatic). The main grammatical meaning of the sentence is predicativity, which makes it possible to correlate information about extralinguistic reality (the fact of communication) with that speech situation in which the utterance is generated (with the act of communication). This is how the phrase differs from the sentence, briefly.

In the syntax, only free phrases are studied, that is, in which the independent lexical meanings of the words included in it are fully preserved. If they are lost, we are dealing with phraseological units that are no longer the subject of grammar.

Construction of word combinations

Phrases are built on a certain historically formed in the language model, that is, reproduced in speech. They have a system of forms of change, a paradigm that completely coincides with the paradigm of the main word (here is another difference of the phrase from the sentence).

They can include not only two components: the main and the dependent (a simple phrase). In a sentence, several components (more than two) can be combined in meaning and grammatically, between which there are different kinds of syntactic dependence.

Types of multicomponent word combinations

They may be:

— combined (consistent submission): buy a desk, my father’s friend;

— complex (parallel submission): widely known in the city, give a friend a book;

— common (with heterogeneous definitions at the main): an antique crystal vase, a juicy uncoated grass;

— merged (formed when the proposal is formed): bought newspapers and magazines, woolen and silk fabrics.

Analysis of word combinations

The first procedure of analysis is to extract a whole word-block from the sentence, define its type and divide it into simple (two-component) blocks.

The second step is the analysis of a simple phrase combination, taking into account many parameters characterizing it according to the following scheme:

1) the initial form;

2) spurious ownership of the main word;

3) the type of syntactic connection and means of expression;

4) the type of syntactic relations;

5) conditionality of the form of the dependent word;

6) model (structural diagram).

Conditionality of the form of the dependent word

The conditional nature of the form of the dependent word can be determined by the grammatical properties of the principal, for example, belonging to a certain class of words (part of speech) or to a particular grammatical category. Thus, the ability to determine with the help of an adjective is inherent in nouns: a cheerful milkman, an old book.

Verbs as a grammatical class of words are determined by qualitative adverbs: work hard, speak loudly. All these phrases are grammatically conditioned. The presence of a dependent form in the accusative case without a preposition is determined by lexico-grammatical properties, the transitivity of the main verb: read the book, drink milk.

The form of the dependent word can be determined by the belonging of the principal to a certain semantic class or lexical-semantic group (LSG). Thus, all words with the meaning of verbal communication form word combinations with a dependent noun in the form of an instrumental with the preposition «c»: to talk with someone, to discuss with someone. Lexems of different parts of speech, including the modal component (possibility, desire, necessity, etc.) in their meaning, have the infinitive of the verb as dependent: to want to learn, we must learn, the desire to learn, ready to learn. All these phrases are semantically conditioned.

Finally, the form of the dependent word can be determined by the individual lexical meaning of the principal. In this case, even representatives of one LSG can form different phrases: selling fruits — selling fruit; Pay for travel — pay for travel; To be proud of another is to bow before a friend. In this case, they speak of lexically conditioned phrases.

The difference from other combinations of words

Knowing how the phrase differs from the sentence, it is necessary to distinguish it from other combinations of words.

As a special syntactic unit with a number of properties and having a language model (structural scheme), it must be distinguished from the following combinations of words in the sentence:

1) from predicative combinations (subject + predicate): the boy runs;

2) from semi-predictive: and he, rebellious, asks for storms;

3) from the co-authors: trees and shrubs grew in the clearing;

4) from the apposition combinations (combination of the application and the word being defined): the student Ivanov went out;

5) from combinations that arise only in the sentence: father and son were very similar.

Knowing how the phrase differs from the sentence and other combinations of words in it, you will intelligently parse and not allow grammatical errors. This is an important point in the study of the «syntax» section, since the above elements are basic in it, and they need to be delimited. We hope, we have explained clearly in this article how to distinguish the word combination from the sentence.

1. What is a Phrase?

A phrase is a group of two or more words that work together but don’t form a clause. In truth, “phrase” is a very broad term that we often use as a name for sayings, quotes, or other parts of every day speech, but this article will discuss phrases as they work in grammar.

It’s important to know the difference between a phrase and a clause. As you might know, a clause must include a subject and a predicate. A phrase, however, doesn’t contain a subject and a predicate, so while it’s found within a clause, a phrase can’t be a clause. Instead, a phrase can be made up of any two or more connected words that don’t make a clause. For example, “buttery popcorn” is a phrase, but “I eat buttery popcorn” is a clause.

Because it isn’t a clause, a phrase is never a full sentence on its own.

2. Examples of Phrases

Phrases are a huge part of speaking and writing in English. Here are a few you are probably familiar with, and their types, which will be explained later:

- Once in a blue moon (prepositional phrase)

- Reading a book (present participle phrase)

- To be free (infinitive phrase)

- Totally delicious food (noun phrase)

- Running water (gerund phrase)

As you can see, none of the groups of words above are full sentences, but they still work together—which is why we have phrases!

3. Types of Phrases

The English language has an endless number of phrases. Different types of phrases serve different purposes and have different functions within sentences. All of the types here are both important and used all of the time in our everyday language. In fact, you probably use all of these types and just don’t know their names!

a. Prepositional Phrase

A prepositional phrase is a phrase that begins with a preposition and ends with a noun, pronoun, or clause (called the object of the preposition). For example,

The dog is at the county fair.

In this sentence, “at the county fair” begins with a preposition (at) and ends with a noun (carnival), making it the prepositional phrase.

b. Participle Phrase

A participle phrase begins with a past or present participle, and is usually combined with an object or modifier. Present participles always end in ing, but past participles vary; regular verbs end in ed while irregular words are different. Participle phrases work like adjectives, describing something in the sentence:

- I saw the dog running towards the county fair (present participle)

- The dog ran towards the county fair. (past participle)

In the first sentence, the participle phrase “running towards the county fair” works as an adjective. It combines the present participle “running” with “towards the county fair” to describe the dog. In the second, the past participle “ran” does the same. Here are two more examples:

- Eating popcorn, the dog was very happy.

- The dog’s belly was stuffed with popcorn.

The participle phrase underlined in the first sentence describes the dog, and the participle phrase in the second describes the dog’s belly.

c. Noun Phrase

A noun phrase has a noun or pronoun as the main word, and acts like a noun in a sentence. Sometimes it includes a modifier, like an adjective, for example “big dog” and “brown fur.” Or, a noun phrase can be longer, like “the big dog with brown fur.” Here’s a full sentence:

The big dog with hot popcorn ran to the county fair.

You can tell that the underlined phrase acts as a noun because you could switch it with a single noun, like dog, and the sentence would still be correct. Here’s another example:

I bought a neon green ten-speed bicycle.

Again, let’s switch out the underlined phrase with a single noun to make sure the noun phrase works properly:

I bought a bicycle.

So, you can see that replacing the noun phrase with the single noun “bicycle” still gives us a correct complete sentence.

d. Infinitive Phrase

Quite simply, infinitive phrases start with an infinitive (to + simple form of a verb), and include modifiers or objects.

The dog likes to eat popcorn.

The phrase above uses the infinitive “to eat” combined with the object “popcorn.” Here’s another:

I want to pet the dog.

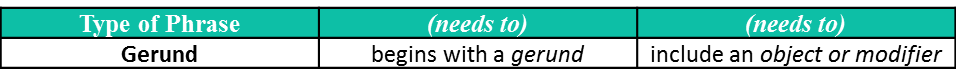

e. Gerund Phrase

A gerund phrase begins with a gerund (a word ending in ing), and includes modifiers or objects.

The dog ate steaming popcorn.

Here, the gerund “steaming” is combined with the object “popcorn” to create a gerund phrase. Here’s another example:

Running water is hard to find in this small village.

Like noun phrases, gerund phrases always work as nouns, and that’s how you tell the difference between a gerund phrase and a present participle phrase. A gerund phrase can replace a noun, while a participle phrase works like an adjective. Compare these two sentences:

The dog ate steaming popcorn. Gerund phrase showing what the dog eats (noun)

The dog was steaming popcorn for the party. Participle phrase describing the dog’s action (adjective)

f. Appositive Phrase

An appositive phrase is a noun or noun phrase that gives another name to the noun next to it. It makes a sentence more descriptive:

- The dog’s favorite food, popcorn

- The dog’s favorite food, hot, salty, buttery popcorn

In both lines above, the underlined parts are appositive phrases that give another name to the noun phrase “the dog’s favorite food.” Here’s are two more:

- The popcorn-eater was a big fluffy beast, a dog.

- The popcorn-eater was a dog, a beagle.

The first sentence describes the dog, and then names what it is. The second sentence says dog, and then specifies what type of dog. Appositive phrases always follow this form.

g. Absolute Phrase

An absolute phrase combines a noun, a participle, and sometimes other modifiers or objects that go with them. It is used to modify a whole clause or sentence.

This absolute phrase has a noun (popcorn) and a participle (popping):

- Popcorn popping, the dog was ready for the movie.

- “Popcorn popping” modifies the clause “the dog was ready for the movie.”

Absolute phrases are optional parts of sentences, so if you one out, the sentence should still work normally—for instance, if you remove “popcorn popping,” “The dog was ready for the movie” still forms a complete sentence.

This absolute phrase has a noun phrase (the dog’s mouth), a participle (watering), and modifier (with excitement):

Mouth watering with excitement, the dog dreamed of eating popcorn.

Here, the absolute phrase modifies the clause “the dog dreamed of eating popcorn.”

4. How to Write a Phrase

Phrases are pretty easy to use in every day writing and speaking. In fact, most logical combinations of words (that aren’t clauses, of course) are phrases. They can take on all kinds of forms and combinations. They can be short, like “the furry dog,” or long, like “the furry dog that liked eating popcorn every day for breakfast.” Being able to distinguish phrases from clauses is what’s most important when writing and identifying them in writing or speech. The best way to do that is to break a sentence or group of words down into parts.

So, let’s make sure the difference between phrases and clauses is clear. To review, a phrase can contain a noun and a verb, but it doesn’t have the subject-predicate combination required to make a clause. A clause follows the pattern Subject + Predicate. Let’s look at this phrase:

The running dog

Here, “the running dog” is a phrase that includes the noun “dog” and the verb “running;” but, there is no predicate—it follows the pattern Verb + Noun, and does not have a subject. But, we can use this phrase to make a full sentence. To make a complete sentence, the phrase “the running dog” works as the subject:

The running dog is hungry.

Here, the subject “the running dog” combined with the predicate “is hungry” makes a full sentence. So, the phrase itself does not have a subject and a predicate, but is part of the subject-predicate combination that makes a sentence.

Phraseological turns are a scourge of everyone wholearns a foreign language, because, faced with them, a person often can not understand what is at stake. Often, in order to understand the meaning of a particular utterance, one has to use a dictionary of phraseological combinations, which is by no means always at hand. However, there is a way out — you can develop the ability to recognize phraseological units, then it will be easier to understand their meaning. True, for this you need to know what kinds of them are and how they differ. Particular attention in this matter should be given to phraseological combinations, because they (because of the different ways of classifying them) create the most problems. So, what is it, what are their distinguishing features and in which dictionaries can you find clues?

Phraseology and the subject of its study

The science of phraseology, which specializes instudy of a variety of stable combinations, relatively young. In Russian linguistics, it began to stand out as a separate section only in the eighteenth century, and even then at the end of this century, thanks to Mikhail Lomonosov.

The most famous of its researchers are linguistsVictor Vinogradov and Nikolay Shansky, and in English — A. Mackey, W. Weinreich and L. P. Smith. By the way, it should be noted that English-speaking linguists, in contrast to Slavic specialists, pay much less attention to phraseological units, and their stock in this language is inferior to Russian, Ukrainian or even Polish.

The main subject, on the study of whichThis discipline concentrates its attention, it is phraseological or phraseological turnover. What is it? This is a combination of several words, which is stable in structure and composition (it is not compiled anew every time, but is used in an already prepared form). For this reason, when syntactically analyzing phraseology, regardless of its type and length of its constituent words, always appears as a single member of the sentence.

The phraseology in each language isA unique thing, connected with its history and culture. It can not be fully translated without losing its meaning. Therefore, when translating the most often selected are already similar in meaning phraseology, existing in another language.

For example, the famous English phraseologicalthe combination: «Keep your fingers on the pulse», which literally means «keep your fingers on the pulse,» but it makes sense to «keep abreast of events.» However, since in Russian there is no one hundred percent equivalent, it is replaced with a very similar one: «Keep your hand on the pulse.»

Sometimes, thanks to the close proximity of countries,their languages there are similar phraseological turns, and then there are no problems with the translation. Thus, the Russian expression «to beat the buckets» (to sit back) has its twin brother in the Ukrainian language — «bytyk’s byties».

Often similar expressions come at the same timeseveral languages because of some important event, such as Christianization. Despite belonging to different Christian denominations, in Ukrainian, French, Spanish, German, Slovak, Russian and Polish, the phraseologism “alpha and omega” taken from the Bible and denoting “from beginning to end” (completely, thoroughly) is common.

Types of phraseological turns

On the classification of phraseologicallinguistic scholars have not come to the same opinion. Some additionally classify to them proverbs (“You cannot stay without the sun, you cannot live without the sweet”), sayings (“God will not give out — the pig will not eat”) and language stamps (“hot support”, “working environment”). But while they are in the minority.

Currently the most popularEast Slavic languages are used by the classification of linguist Viktor Vinogradov, who distributed all the stable phrases into three key categories:

- Phraseological unions.

- Phraseological unity.

- Phraseological combinations.

Many linguists associate adhesions andunity with the term «idiom» (by the way, it is a single-root word with the noun «idiot») which is actually a synonym for the noun «phraseological unit». This is due to the fact that sometimes the line between them is very difficult. This name is worth remembering, as in English phraseological adhesions, unity, combinations are translated with its help — idioms.

The question of phraseological expressions

Vinogradov’s colleague Nikolay Shansky insisted onthe existence of the fourth kind — expressions. In fact, he divided Vinogradov’s phraseological combinations into two categories: combinations and expressions proper.

Although Shansky’s classification leads to confusion in the practical distribution of stable phrases, it does, however, make it possible to examine this linguistic phenomenon more deeply.

What is the difference between phraseological adhesions, phraseological unity, phraseological combinations?

First of all, it is worth understanding that these stable units were divided into these types according to the level of lexical independence of their components.

Turnovers, which are completely inseparable,the meaning of which is not connected with the meaning of their components, called were phraseological adhesions. For example: “sharpen lyasy” (to lead a stupid conversation), to wear one «s heart on one» s sleeve (to be frank, literally means to wear a heart on the sleeve). By the way, figurativeness is characteristic of splices, most often they arise from popular speech, especially outdated expressions or from ancient books.

Phraseological unity are moreindependent species, in relation to its components. Unlike splices, their semantics is determined by the value of their components. For this reason, here are puns. For example: “small and remote” (a person doing something well, despite his unimpressive external data) or Ukrainian idiom: “convicted on merit” (the guilty received a punishment corresponding to his own offense). By the way, both examples illustrate a unique feature of unity: rhyming harmonies. Perhaps that is why Victor Vinogradov attributed to them sayings and proverbs, although their membership in phraseological units is still challenged by many linguists.

The third view: free phraseological combinations of words. They are quite significantly different from the two above. The fact is that the value of their components directly affects the meaning of the whole turnover. For example: “deep drunkenness”, “raise the question”.

Phraseological combinations in Russian (as well asin Ukrainian and English) have a special property: their components can be replaced by synonyms without losing meaning: “offend honor” — “offend pride”, “crimson ringing” — “melodious ringing”. As an example from the language of the proud British, the idiom to show one’s teeth can be adapted to any person: to show my (your, his, her, our) teeth.

Phraseological expressions and combinations: distinctive features

Viktor Vinogradov classification, in whichThe composition was allocated only one analytical form (phraseological combinations), was gradually supplemented by Nikolai Shansky. Distinguishing between idioms and combinations was quite simple (due to their differences in structure). But Shansky’s new unit — expressions (“to fear wolves — not to go to the forest”) was more difficult to distinguish from combinations.

But, if you delve into the question, you can see a cleardistinction that relies on the meaning of phraseological combinations. So, expressions consist of absolutely free words that fully possess independent semantics (“not all gold is that glitters”). However, they differ from the usual phrases and sentences in that they are stable expressions that are not assembled on the new, but are used in finished form as a template: “horseradish is not sweeter” (Ukrainian version of “horseradish is not malt”).

Phraseological combinations (“give head toclipping ”-“ giving a hand to clipping ”) always includes several words with unmotivated meaning, while all components of expressions are absolutely semantically independent (“ Man — this sounds proud ”). By the way, this feature of them forces some linguists to doubt that the expressions belong to phraseological turns.

What word combination is not a phrase phrase?

Phraseological units, from a lexical point of view, areis a unique phenomenon: on the one hand, they have all the signs of word combinations, but at the same time they are more similar in their properties to words. Knowing these features, you can easily learn to distinguish stable phraseological combinations, unity, fusion or expression from ordinary phrases.

- Phraseologisms, like phrases, consist ofseveral related tokens, but most often their meaning is incapable of going beyond the sum of the values of their components. For example: “lose your head” (stop thinking soberly) and “lose your wallet”. The words that make up the idiom are most often used figuratively.

- When used in speaking and writingThe composition of phrases is formed each time. But unity and adhesions are constantly reproduced in finished form (which makes them related to speech clichés). The phraseological combination of words and the phraseological expression in this question are sometimes confused. For example: “hang your head” (saddened), although it is a phraseological unit, but each of its components can also appear freely in the usual phrases: “hang a frock coat” and “hang your head”.

- Phraseological turnover (due to the integritythe values of its components) in most cases, you can safely replace the word-synonym, which can not be done with the phrase. For example: the expression «servant of Melpomene» can be easily changed to the simple word «artist» or «actor.»

- Idioms never act astitles. For example, the Dead Sea hydronym and the phrase «dead season» (unpopular season), «lie a dead weight» (lie unused cargo).

Classification of phraseological units by origin

Considering the question of the origin of phraseological combinations, expressions, unity and adhesions can be divided into several groups.

- Combinations that came from popular speech: “get on your feet,” “without a king in my head” (stupid), “without a year a week” (a very short time).

- Professional cliches, which gradually turned into phraseological units: «black and white», «pour water on the mill», «at cosmic speed.»

- Become iconic sayings of famoushistorical personalities or literary heroes, film characters: “The main thing is to have a suit sitting” (“Wizards”), “You need to be more careful, guys” (M. Zhvanetsky), I have a dream (Martin Luther King).

- Stable phraseological combinations,borrowed from other languages, sometimes without translation. For example: o tempora, o mores (about times, about morals), carpe diem (seize the moment), tempus vulnera sanat (time heals wounds).

- Quotes from the Bible: “Throwing beads” (telling / showing something to ungrateful listeners / viewers), “waiting until the second coming” (waiting for something for a long time and probably meaningless), “prodigal son”, “manna from heaven”.

- Sayings from ancient literature: “the apple of discord” (controversial subject), “gifts of the Danaians” (evil caused under the mask of good), “the glance of Medusa” (what makes it freeze in place, like a stone).

Other classifications: Peter Dudik’s version

- In addition to Vinogradov and Shansky, and other linguiststried to separate idioms, guided by their own principles. So, the linguist Dudik identified not four, but five kinds of phraseological units:

- Semantically inseparable idioms: “to be on a short leg” (close with someone to know).

- Phraseological unity with the freer semantics of the constituent elements: “lather the neck” (punish someone).

- Phraseological expressions, fully composedfrom independent words, the total value of which cannot be matched. Dudik mainly refers to them sayings and proverbs: «The pig goose is not a friend.»

- Phraseological combinations — phrases based on the metaphorical meaning: «blue blood», «falcon eye».

- Phraseological phrase. Characterized by the lack of metaphorical and syntactic unity of the components: “the big swell”.

Igor Melchuk’s classification

Apart from all of the above, there is a classification of Melchuk’s phraseological units. According to it, much more species are allocated, which are divided into four categories.

- Degree: full, semiframem, quasi-phrasyma.

- The role of pragmatic factors in the formation of a phraseological unit: semantic and pragmatic.

- To which language unit does it belong: lexeme, phrase, syntactic phrase.

- The component of a linguistic sign that has undergone phraseology: a syntactic sign meaning and signified.

Boris Larin’s classification

This linguist distributed stable combinations of words by stages of their evolution, from ordinary phrases to phraseological units:

- Variable phrases (analogue of combinations and phraseological expressions): «velvet season».

- Those who have partially lost their primary meaning, but were able to acquire metaphor and stereotype: «keep the stone in the bosom.»

- Idioms completely devoid of semanticindependence of their components, as well as those that have lost their connection with their original lexical meaning and grammatical role (analogous to phraseological adhesions and unities): «out of hand» (bad).

Common examples of phraseological combinations

Below are some more fairly well-known stable phrases.

- “Being at ease” (feeling uncomfortable).

- «Down eyes» (embarrassed).

- «Defeat» (defeat someone).

- “A touchy question” (a problem requiring careful consideration).

Although the classification of idioms of the English languageVinogradov and Shansky does not apply, but you can pick up stable phrases that can be classified as phraseological combinations.

Examples:

- Bosom friend — bosom buddy (bosom friend — bosom buddy).

- A Sisyfean labor.

- A pitched battle — a fierce battle (a fierce battle — a fierce battle).

Phrasebooks

The presence of a large number of classificationsphraseological units due to the fact that none of them does not give one hundred percent guarantee no error. Therefore, it is still worth knowing in which dictionaries you can find a hint, if it is impossible to determine the exact type of phraseological unit. All dictionaries of this type are divided into monolingual and multilingual. The most famous books of this kind are translated below, in which you can find examples of stable expressions that are most common in the Russian language.

- Monolingual: «Educational phraseological dictionary» E. Bystrovoy; «Burning Verb — Dictionary of Popular Phraseology» V. Kuzmich; «Phraseological dictionary of the Russian language» A. Fedoseyev; «Phraseological dictionary of the Russian literary language» I. Fedoseev and «Big explanatory-phraseological dictionary» M. Michelson.

- Multilingual: «Great English-Russian phraseological dictionary»(twenty thousand phraseological revolutions) A. Kunin, “The Great Polish-Russian, Russian-Polish Phraseological Dictionary” by Yu. Lukshin and Random House Russian-English Dictionary of Idioms by Sofia Lubenskaya

Perhaps learning that sometimes it is not easy to goto distinguish which species a particular idiom belongs to, this topic may seem incredibly complex. However, the devil is not so bad as he is painted. The main way to develop the ability to correctly find a phraseological combination of words among other phraseological units is to train regularly. And in the case of foreign languages, study the history of the emergence of such phrases and memorize them. This will not only help in the future not to get into awkward situations, but also make the speech very beautiful and imaginative.