When students engage in “word analysis” or “word study,” they break words down into their smallest units of meaning — morphemes. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to our understanding of the whole word.

What does word analysis mean?, Word analysis is a process of learning more about word meanings by studying their origins and parts. A “morpheme” is the smallest meaningful part of a word. Other terms for word analysis: Morphemic analysis.

Furthermore, How do you analyze a word?, In “word analysis” or “word study,” students break words down into morphemes, their smallest units of meaning. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to the whole word. Students’ knowledge of morphemes helps them to identify the meaning of words and builds their vocabulary.

Finally, What is analysis of word structure?, Structural analysis is the process of breaking words down into their basic parts to determine word meaning. … When using structural analysis, the reader breaks words down into their basic parts: Prefixes – word parts located at the beginning of a word to change meaning. Roots – the basic meaningful part of a word.

Frequently Asked Question:

How do you teach the word meaning?

How to teach:

- Introduce each new word one at a time. Say the word aloud and have students repeat the word. …

- Reflect. …

- Read the text you’ve chosen. …

- Ask students to repeat the word after you’ve read it in the text. …

- Use a quick, fun activity to reinforce each new word’s meaning. …

- Play word games. …

- Challenge students to use new words.

How do you understand words meaning?

To understand a word without a dictionary, try re-reading the entire sentence to see if the context helps you to find out what the word means. If it’s unclear, try to figure it out by thinking about the meaning of the words you’re familiar with, since the unknown word might have a similar meaning.

How do you teach word concepts?

The first step with Concept of Word Instruction is to teach the poem to the students. They need to have the poem memorized, so that they can accurately match the memorized words to the print they see. Teachers can use pictures that represent the text or hand motions with common nursery rhymes and finger plays.

How do you teach words with multiple meanings?

Play word games that ask students to recognize words‘ multiple meanings. For example, create—or have students illustrate—pairs of cards to tell or show two meanings of a specific word. Use the cards to play a matching game. Students should collect both pictures for a word and give a verbal definition of each picture.

How can we help students to understand meaning?

Follow these steps and try some different techniques in your classroom:

- Choose a lesson from your textbook. …

- Before the lesson, select some words that you think your students won’t know. …

- Decide how you could help your students understand these words. …

- Before your students read the lesson, write the words on the board.

What does structural analysis mean?

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS is a strategy that is used to facilitate decoding as students become more proficient readers. These advanced decoding strategies help students learn parts of words so they can more easily decode unknown multi-‐syllabic words. In structural analysis, students are taught to read prefixes and suffixes.

What is structure in structural analysis?

1.1 Structural Analysis Defined. A structure, as it relates to civil engineering, is a system of interconnected members used to support external loads. Structural analysis is the prediction of the response of structures to specified arbitrary external loads.

What is word analysis?

When students engage in “word analysis” or “word study,” they break words down into their smallest units of meaning — morphemes. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to our understanding of the whole word.

What are the types of structural analysis?

What are the types of Structural Analysis?

- Hand Calculations. Hand Calculations in Structural Analysis. …

- Finite Element Analysis. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) …

- Structural Analysis Software.

What is structural analysis of words?

Structural analysis is the process of breaking words down into their basic parts to determine word meaning. … When using structural analysis, the reader breaks words down into their basic parts: Prefixes – word parts located at the beginning of a word to change meaning. Roots – the basic meaningful part of a word.

How do I teach word study?

A cycle of instruction for word study might include the following:

- introduce the spelling pattern by choosing words for students to sort.

- encourage students to discover the pattern in their reading and writing.

- use reinforcement activities to help students relate this pattern to previously acquired word knowledge.

How do you teach the word meaning?

How to teach:

- Introduce each new word one at a time. Say the word aloud and have students repeat the word. …

- Reflect. …

- Read the text you’ve chosen. …

- Ask students to repeat the word after you’ve read it in the text. …

- Use a quick, fun activity to reinforce each new word’s meaning. …

- Play word games. …

- Challenge students to use new words.

What are some strategies for breaking words apart to get their meaning?

5 Ways To Have K-2 Students Practice Breaking Apart Words

- Segment the sounds in a CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) word.

- Read the onset and rime of a word (i.e. sh-ip)

- Recognize and read word families.

- Read “smaller” words inside compound words.

- Derive meaning from root words, prefixes, and suffixes.

What is word analysis?

When students engage in “word analysis” or “word study,” they break words down into their smallest units of meaning — morphemes. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to our understanding of the whole word.

How do you analyze a word?

In “word analysis” or “word study,” students break words down into morphemes, their smallest units of meaning. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to the whole word. Students’ knowledge of morphemes helps them to identify the meaning of words and builds their vocabulary.

What is analysis example?

The definition of analysis is the process of breaking down a something into its parts to learn what they do and how they relate to one another. Examining blood in a lab to discover all of its components is an example of analysis. noun.

What is Analysis sentence?

The purpose of analysis is to make the complete grammatical structure of a sentence clear. Each part of the sentence is identified, its function des- cribed, and its relationship to the other parts of the sentence explained. There are different ways of presenting a sentence analysis.

Introduction

When students engage in “word analysis” or “word study,” they break words down into their smallest units of meaning — morphemes. Each morpheme has a meaning that contributes to our understanding of the whole word. As such, students’ knowledge of morphemes helps them to identify the meaning of words and build their vocabulary. The Institute for Educational Science (IES) Practice Guide strongly recommends providing explicit vocabulary instruction, which includes providing students with strategies for acquiring new vocabulary. The ability to analyze words is a critical foundational reading skill and is essential for vocabulary development as students become college and career ready.

Teaching word analysis skills satisfies several of the Common Core State Standards for literacy, including:

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.10 Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.li>

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.4 Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases by using context clues, analyzing meaningful word parts, and consulting general and specialized reference materials, as appropriate.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.5 Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

Teaching word analysis

As you create your plan for teaching word analysis strategies, think about the tools and methods that can support students’ understanding, and provide students with opportunities to practice using these tools and methods. Think, too, about how you could differentiate instruction and take advantage of technology tools to engage the diverse students in your classroom.

You can effectively differentiate word analysis techniques by providing clear and varied models, keeping in mind the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Model how to analyze a new word by breaking it down into its sub-parts, studying each part separately, and then putting the parts back together in order to understand the whole word (see UDL Checkpoint 3.3: Guide information processing, visualization, and manipulation ).

It also helps to demonstrate that when you are studying vocabulary in a specific content area (e.g., science), you can find patterns in the prefixes that will help you understand what the words mean in that context. For example:

- Science: biology, biodegradable, biome, biosphere

- Mathematics: quadruple, quadrant, quadrilateral, quadratic

- Geography: disassemble, disarmament, disband, disadvantage

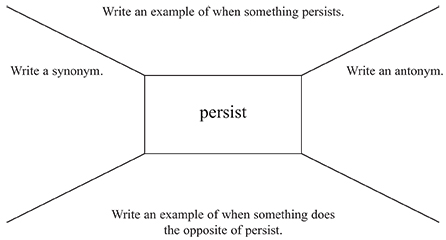

Students should also learn to track both the words and the word parts they learn through these strategies. Show students how to use offline and online visual diagrams, worksheets, and graphic organizers to visualize the relationship between words and store new vocabulary.

Word analysis in practice

If you provide students with opportunities to repeatedly practice analyzing unfamiliar vocabulary, their word analysis skills will continue to develop. Engage students individually, in pairs, or in small groups in a variety of games and activities, based on their individual abilities and needs. Consider ways in which you could modify the following games and activities to benefit struggling students:

- The mix-and-match game using roots, prefixes, and suffixes

- A word search in social studies, science, and mathematics texts to find words with prefixes and suffixes

- Using Scrabble or Boggle tiles to form and re-form words

- Movement activities that involve students holding up cards with root words, prefixes, and suffixes and reordering themselves to make words

- Inventing a word by creating and defining nonsense words with prefixes and suffixes

Build word study into your classroom reading routine by pre-teaching words, introducing new vocabulary words weekly, and reviewing new words. Motivate students to practice using their word analysis skills by having them create glossaries of words with prefixes and suffixes from self-selected, high-interest texts.

You can also make use of multimedia and embedded supports to further support your varied learners and foster vocabulary development. Take a look at the videos below on Captioning and Embedded Supports for more ideas on how to leverage multimedia for vocabulary learning.

In the classroom

Searching for meaning in new words can be a bit like gathering clues to solve a mystery. Mr. Chen took advantage of this analogy in his unit on Ancient India by thematically tying vocabulary acquisition to the archeological excavation of the sites his students were studying. In particular, Mr. Chen sought to assist his struggling readers by offering strategies for tackling the unfamiliar terms in the social studies text, which aligns with the CCSS for literacy (see above).

Mr. Chen focused his instruction on modeling a good technique for word analysis. He presented a word that students would encounter several times in their reading — terracotta — and led the class through an analysis of the roots and parts of the word. By listing other words that sound like the prefix terra- (such as terrarium and extraterrestrial), students were able to determine that terra- relates to dirt and the earth.

Mr. Chen has access to several technology tools that he knows will benefit his struggling students. On his interactive whiteboard, he will demonstrate how to use Harappa.com to explore audio, video, text, and photos. He will also encourage students to use online reference tools — such as Visual Thesaurus , the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary , and PrefixSuffix.com — to help students understand word parts. He has found that the classroom wiki, which was created in order to record and share words, has become a “go-to” place for students.

Mr. Chen’s lesson plan is detailed in the chart below, which divides the lesson into three parts: before reading, during reading, and after reading.

Lesson Plan

| Before Reading |

|

|---|---|

| During Reading |

|

| After Reading |

|

Online teacher resources

This article draws from the PowerUp WHAT WORKS website, particularly the Word Analysis Instructional Strategy Guide . PowerUp is a free, teacher-friendly website that requires no log in or registration. The Instructional Strategy Guide on Word Analysis includes a brief overview that defines word analysis along with an accompanying slide show; a list of the relevant ELA Common Core State Standards; evidence-based teaching strategies to differentiate instruction using technology; another case story; short videos; and links to resources that will help you use technology to support instruction in word analysis. If you are responsible for professional development, check out the PD Support Materials for helpful ideas and materials for using the word analysis resources. Want more information? See PowerUp WHAT WORKS .

With hundreds of thousands of words in the English language, teaching vocabulary can seem quite a hard process. The average native speaker uses about five thousand words in everyday speech. As for ESL students, Professor Stuart Webb says the most effective way to be able to speak a language quickly is to pick the 800 to 1,000 lemmas which appear most frequently in a language, and learn those. If you learn only 800 of the most frequently-used lemmas in English, you’ll be able to understand 75% of the language as it is spoken in normal life. There are a number of important steps to consider what students need to know about the items, and how you can teach them.

What may a student need to know about a vocabulary item?

When teaching new vocabulary, make sure to include the following information:

- The meaning

It is vital to get across the meaning of the item clearly and to ensure that your students have understood correctly with checking questions.

- The form

Students need to know if it is a verb / a noun / an adjective etc to be able to use it effectively.

- The Pronunciation/Spelling

This aspect is important especially as in many cases the word’s pronunciation and spelling are quite different. So it is essential to turn to the word’s written transcript, drill and highlight the word stresses.

- The grammatical patterns the word follows

For example, tooth-teeth (singular-plural) and if the word is followed by a particular preposition (e.g. rely on, belong to)

- The Register of the Word

Is the word formal/informal or neutral, when and with whom it is appropriate to use the language. - For example, comprehend is formal, understand is neutral and get is informal.

- How the word is collocated to others

You describe things ‘in great detail’ not ‘in big detail’ and to ask a question you ‘raise your hand’ you don’t ‘lift your hand’. It is important to highlight this to students to prevent mistakes in usage later.

Where can the teacher find that information?

1) There are a number of resources which the teacher can use to find the information necessary for vocabulary analysis. The most reliable resources are the officially recognized online dictionaries, such as Cambridge Dictionary, Oxford Dictionary, Dictionary.com. In these dictionaries, you can find detailed information about the word’s meaning, American vs British spelling and pronunciation, its register, collocations, synonyms, antonyms, the grammatical patterns in which it is used.

If we look at the word entry “comprehend” and search it in Oxford Dictionary we get a full information about its American and British pronunciation, its register (formal), a number of collocations it is used in (with adverbs- fully, barely, easily, verb + comprehend be (un)able to..), the synonymic set accompanying the word (understand, get, see, follow, grasp) and what kind of different shades of meanings they have and in which contexts they are mostly used. There is also information about its origin.

The Dictionary.com provides extra information about the other words from “comprehend”, like (comprehender, precomprehend, self-comprehending, well-comprehended, etc). There is extra information about the words which may be confused with the word comprehend. All the information provided in this dictionary is really valuable in terms of word analysis.

2) British National Corpus gives you relevant information about the frequency level of the word entry and how it is collocated to other words. This is a very handy resource for all English teachers. See how to use it following this video. Read more about corpora in this article.

3) There are a number of vocabulary profilers that analyze the text according to the vocabulary level and its frequency. Here is the link to an article that describes the main vocabulary profilers.

4) Useful information about word collocations teachers can find in Cambridge Dictionary under each meaning, on the right corner of the page for each entry. Oxford Dictionary also provides a huge amount of information on each entry in terms of collocations under the heading Check out also Oxford Collocations Dictionary and (Google Play app) and Longman Collocations Dictionary and Thesaurus.

Lextutor is another amazing tool for text analysis, including collocations.

I also use ozdic.com, phrasebank and just-the-word.com to help students find the right collocations.

Surely, it is quite a difficult work to provide full and comprehensive information for the students. Based on the given resources the teacher will have ample tools for a good vocabulary analysis to prepare for a lesson.

In the following sentence, write an appropriate modal in the blank provided.

Choose your answer from the modals can, could, may, might, must, ought, shall, should, will, and would.

Example: Most kindergartners can‾underline{color{#c34632}{can}} memorize their own phone number.

I _______________ have spoken in his defense; unfortunately, I did not.

As

has been already mentioned, no vocabulary of any living language is

ever stable but is constantly changing, growing and decaying. The

changes occurring in the vocabulary are due both to linguistic and

non-linguistic causes, but in most cases to the combination of both.

Words may drop out altogether as a result of the disappearance of the

actual objects they denote, e.g. the OE.

wunden-stefna

—

‘a curved-stemmed ship’; зãг—

180

’spear,

dart’; some words were ousted1

as a result of the influence of Scandinavian and French borrowings,

e.g. the Scandinavian take

and

die

ousted

the OE:

niman

and

sweltan,

the

French army

and

place

replaced

the OE.

hēre

and

staÞs.

Sometimes

words do not actually drop out but become obsolete, sinking to the

level of vocabulary units used in narrow, specialised fields of human

intercourse making a group of archaisms: e g. billow

— ‘wave’;

welkin

— ’sky’;

steed

— ‘horse’;

slay

— ‘kill’

are practically never used except in poetry; words like halberd,

visor, gauntlet are

used only as historical terms.

Yet

the number of new words that appear in the language is so much

greater than those that drop out or become obsolete, that the

development of vocabularies may be described as a process of

never-ending growth.2

|

Groups of Synonyms |

Frequency Value |

Structure |

The Number of Meanings |

Style |

Etymology |

|||||||

|

Morphemic |

Derivational |

1 |

2 |

3 and |

Neutral, standard |

Bookish, non-literary |

Native, |

Late borrowings |

||||

|

Monomorphic |

Polymorphic |

Simple |

Derived |

|||||||||

|

I

Fair

Dispassionate

Composed Imperturbable Nonchalant |

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||||||

|

7 |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

11 |

+ |

+ |

-4- |

+ |

||||||||

|

13 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||||

|

14 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||||

|

15 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||||||

|

17 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

||||||

|

17 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||||||

|

19 |

+ |

— |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

||||||

1

‘Etymological Survey…’, §

12, p.

172.

2 It

is of interest to note that the number of vocabulary units in Old

English did not exceed 30

— 40 thousand

words, the vocabulary of Modern English is at least ten times larger

and contains about 400

— 500 thousand

words.

181

The

appearance of a great number of new words and the development of new

meanings in the words already available in the language may be

largely accounted for by the rapid flow of events, the progress of

science and technology and emergence of new concepts in different

fields of human activity. The influx of new words has never been more

rapid than in the last few decades of this century. Estimates suggest

that during the past twenty-five years advances in technology and

communications media have produced a greater change in our language

than in any similar period in history. The specialised vocabularies

of aviation, radio, television, medical and atomic research, new

vocabulary items created by recent development in social history

— all

are part of this unusual influx. Thus war has brought into English

such vocabulary items as blackout,

fifth-columnist, paratroops, A-bomb, V-Day, etc.;

the development of science gave such words as hydroponics,

psycholinguistics, polystyrene, radar, cyclotron, meson, positron;

antibiotic, etc.;1

the conquest and research of cosmic space by the Soviet people gave

birth to

sputnik, lunnik, babymoon, space-rocket, space-ship, space-suit,

moonship, moon crawler, Lunokhod, etc.

The

growth of the vocabulary reflects not only the general progress made

by mankind but also the peculiarities of the way of life of the

speech community in which the new words appear, the way its science

and culture tend to develop. The peculiar developments of the

American way of life for example find expression in the vocabulary

items like taxi-dancer

— , ‘a

girl employed by a dance hall, cafe, cabaret to dance with patrons

who pay for each dance’; to

job-hunt

— ‘to

search assiduously for a job’; the political life of America of

to-day gave items like witchhunt

— ‘the

screening and subsequent persecution of political opponents’;

ghostwriter

— ‘a

person engaged to write the speeches or articles of an eminent

personality’; brinkmanship

— ‘a

political course of keeping the world on the brink of war’;

sitdowner

— ‘a

participant of a sit-down strike’; to

sit in

— ‘to

remain sitting in available places in a cafe, unserved in protest of

Jim Crow Law’; a

sitter-in; a lie-in or

a

lie-down

— ‘a

lying

1

The

results of the analysis of the New

Word Section of Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary covering

a period of 14

years

(from 1927

to

1941)

and

A

Dictionary of New English by

С.

Barnhart covering a period of 10

years

(from 1963

to

1972)

confirm

the statement; out of the 498

vocabulary

items 100

(about

1/5

of

the total number) are the result of technological development, about

80

items

owe their appearance to the development of science, among which 60

are

new terms in the field of physics, chemistry, nuclear physics and

biochemistry. 42

words

are connected with the sphere of social relations and only 28

with

art, literature, music, etc. See P.

С.

Гинзбург. О

пополнении словарного состава.

«Иностранные языки в школе», 1954, № 1

;

Р. С. Гинзбург, Н. Г. Позднякова. Словарь

новых слов Барнхарта и некоторые

наблюдения над пополнением словарного

состава современного английского языка.

«Иностранные языки в школе», 1975, № 3.

A

similar result is obtained by a count conducted for seven letters of

the Addenda to The

Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English by

A. S. Hornby, E. V. Gatenby, H. Wakefield, 1956.

According

to these counts out of 122

new

units 65

are

due to the development of science and technology, 21

to

the development of social relations and only 31

to

the general, non-specialised vocabulary. See Э.

М. Медникова, Т. Ю. Каравкина.

Социолингвистический

аспект продуктивного словообразования.

«Вестник Московского университета»,

1964, № 5.

182

down

of a group of people in a public place to disrupt traffic as a form

of protest or demonstration’; to

nuclearise — ‘to

equip conventional armies with nuclear weapons’; nuclearisation;

nuclearism

— ‘emphasis

on nuclear weapons as a deterrent to war or as a means of attaining

political and social goals’.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

01.03.2016250.37 Кб459.doc

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

7 Ways to Teach Word Analysis Every Day

I love teaching word analysis skills because they help kids become stronger readers. Learning strategies to figure out the meaning of new words helps students become more confident and independent in their reading. And as they increase their vocabularies, their reading comprehension improves.

But with increasingly harder vocabulary in the upper elementary grades, word analysis can be really challenging for students. So how can we make time for students to practice and improve their word-solving skills all year long?

What Are Word Analysis Skills?

When students use word analysis skills, they are independently using strategies and resources to figure out what unfamiliar words and phrases mean.

Here are specific word analysis skills you might teach to 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders:

- use context clues

- differentiate among multiple meanings of words

- use knowledge of roots, prefixes, suffixes, synonyms, antonyms, and homophones

- use word reference materials (dictionary, glossary, thesaurus)

- identify figurative language

.

How Do We Make Word Analysis Part of the Daily Routine?

Here are some ways that I’ve made word analysis instruction a part of the daily routine so students keep using these skills all year long:

Get Kids Reading

The single best thing kids can do is read different types of text (fiction, nonfiction, poetry, literary nonfiction, functional text, etc.) at different levels. Independent reading, guided reading groups, and literature circles are all opportunities to use vocabulary skills.

As they’re reading, students can use sticky notes and graphic organizers to show the word analysis strategies they used to figure out different words.

Read Aloud

A daily read-aloud is an easy place to incorporate word analysis practice. As you read a chapter book or mentor text, you can model how you stop at an unfamiliar word and infer its meaning using different clues and strategies. After a few examples, you can have students try this out.

Use Anchor Charts and Word Walls

I LOVE using word analysis anchor charts. I use them when I first teach all of the different strategies and keep them up all year long so students can refer back to them. Mini anchor charts in reading notebooks also work if you’re short on wall space!

You can also create a word wall for synonym and antonym pairs, homophone pairs, and common affixes. I like using interactive word walls that students can add to when they find examples in their reading. They can jot them on a sticky note and add them to the wall.

Use Warmup Questions

Starting each day with a word analysis question is a quick and easy spiral review method. I love showing a daily warmup question on the interactive whiteboard and having students answer on their own whiteboards. Stand-alone analysis questions (questions that don’t require reading a passage) are also great to use as time fillers when you have a few extra minutes.

Need help coming up with questions? Grab a free word analysis question stems list below!

Try a Vocabulary Word of the Day

A vocabulary word of the day is another great activity. You can ask students to segment a word into its root word and affixes, come up with a synonym or antonym for a word, etc. It can go up on your whiteboard, be included in a morning message, or even be an “entrance ticket” to enter the classroom. You can make it more fun by challenging students to use the word in their normal conversations.

This is also a good way to review previously taught vocabulary words. Multiple exposures to words in different scenarios will help expand kids’ vocabularies and get them reviewing all those word-solving skills!

Use Literacy Station Activities

If you have word work stations, morning work bins, early finisher options, or centers, you can easily add some quick individual or partner activities that get kids using their word analysis strategies. Here are a few ideas to try:

- file folder games

- crosswords and word searches

- task cards

- sorting activities

- vocabulary word scavenger hunts

- poem of the day/week

- holiday/seasonal themed activities

- board games like Scrabble

If you have laptops or iPads handy, you can also have students practice using online word reference tools. But keep in mind that they’re set up differently than print resources. My students always needed needed a lot of practice with both.

Bring Other Content Areas into Language Arts

Students are certainly going to come across new words in areas like science, social studies, and math. Using short, leveled content-focused passages in reading groups is a helpful way to introduce vocabulary they’ll need to learn. The key is making sure they have enough background knowledge to grasp the majority of the content. We don’t want every word to be new!

I also like to have students create a class glossary or dictionary of terms they learn throughout a unit.

The biggest way to incorporate word analysis skills in your classroom all year long is to have kids read, read, read and to read, read, read to them! The more they come across new words and phrases, the more opportunities they have to figure out what they mean. Doing a spiral review of word solving skills like using context clues, word parts, and word reference sources will keep kids actively working to solve those unknown word meanings all year long.

This article is about learning vocabulary during childhood, as part of a first language. For learning vocabulary while learning a second language, see Vocabulary learning.

Vocabulary development is a process by which people acquire words. Babbling shifts towards meaningful speech as infants grow and produce their first words around the age of one year. In early word learning, infants build their vocabulary slowly. By the age of 18 months, infants can typically produce about 50 words and begin to make word combinations.

In order to build their vocabularies, infants must learn about the meanings that words carry. The mapping problem asks how infants correctly learn to attach words to referents. Constraints theories, domain-general views, social-pragmatic accounts, and an emergentist coalition model have been proposed[1] to account for the mapping problem.

From an early age, infants use language to communicate. Caregivers and other family members use language to teach children how to act in society. In their interactions with peers, children have the opportunity to learn about unique conversational roles. Through pragmatic directions, adults often offer children cues for understanding the meaning of words.

Throughout their school years, children continue to build their vocabulary. In particular, children begin to learn abstract words. Beginning around age 3–5, word learning takes place both in conversation and through reading. Word learning often involves physical context, builds on prior knowledge, takes place in social context, and includes semantic support. The phonological loop and serial order short-term memory may both play an important role in vocabulary development.

Reading is an important means through which children develop their vocabulary.

Early word learning[edit]

Infants begin to understand words such as «Mommy», «Daddy», «hands» and «feet» when they are approximately 6 months old.[2][3] Initially, these words refer to their own mother or father or hands or feet. Infants begin to produce their first words when they are approximately one year old.[4][5] Infants’ first words are normally used in reference to things that are of importance to them, such as objects, body parts, people, and relevant actions. Also, the first words that infants produce are mostly single-syllabic or repeated single syllables, such as «no» and «dada».[5] By 12 to 18 months of age, children’s vocabularies often contain words such as «kitty», «bottle», «doll», «car» and «eye». Children’s understanding of names for objects and people usually precedes their understanding of words that describe actions and relationships. «One» and «two» are the first number words that children learn between the ages of one and two.[6] Infants must be able to hear and play with sounds in their environment, and to break up various phonetic units to discover words and their related meanings.

Development in oral languages[edit]

Studies related to vocabulary development show that children’s language competence depends upon their ability to hear sounds during infancy.[4][7][8] Infants’ perception of speech is distinct. Between six and ten months of age, infants can discriminate sounds used in the languages of the world.[4] By 10 to 12 months, infants can no longer discriminate between speech sounds that are not used in the language(s) to which they are exposed.[4] Among six-month-old infants, seen articulations (i.e. the mouth movements they observe others make while talking) actually enhance their ability to discriminate sounds, and may also contribute to infants’ ability to learn phonemic boundaries.[9] Infants’ phonological register is completed between the ages of 18 months and 7 years.[4]

Children’s phonological development normally proceeds as follows:[4]

6–8 weeks: Cooing appears

16 weeks: Laughter and vocal play appear

6–9 months: Reduplicated (canonical) babbling appears

12 months: First words use a limited sound repertoire

18 months: Phonological processes (deformations of target sounds) become systematic

18 months–7 years: Phonological inventory completion

At each stage mentioned above, children play with sounds and learn methods to help them learn words.[7] There is a relationship between children’s prelinguistic phonetic skills and their lexical progress at age two: failure to develop the required phonetic skills in their prelinguistic period results in children’s delay in producing words.[10] Environmental influences may affect children’s phonological development, such as hearing loss as a result of ear infections.[4] Deaf infants and children with hearing problems due to infections are usually delayed in the beginning of vocal babbling.

Babbling[edit]

Babbling is an important aspect of vocabulary development in infants, since it appears to help practice producing speech sounds.[11] Babbling begins between five and seven months of age. At this stage, babies start to play with sounds that are not used to express their emotional or physical states, such as sounds of consonants and vowels.[7] Babies begin to babble in real syllables such as «ba-ba-ba, neh-neh-neh, and dee-dee-dee,»[7] between the ages of seven and eight months; this is known as canonical babbling.[4] Jargon babbling includes strings of such sounds; this type of babbling uses intonation but doesn’t convey meaning. The phonemes and syllabic patterns produced by infants begin to be distinctive to particular languages during this period (e.g., increased nasal stops in French and Japanese babies) though most of their sounds are similar.[4][7] There is a shift from babbling to the use of words as the infant grows.[12]

Vocabulary spurt[edit]

As children get older their rate of vocabulary growth increases. Children probably understand their first 50 words before they produce them. By the age of eighteen months, children typically attain a vocabulary of 50 words in production, and between two and three times greater in comprehension.[5][7] A switch from an early stage of slow vocabulary growth to a later stage of faster growth is referred to as the vocabulary spurt.[13] Young toddlers acquire one to three words per month. A vocabulary spurt often occurs over time as the number of words learned accelerates. It is believed that most children add about 10 to 20 new words a week.[13] Between the ages of 18 to 24 months, children learn how to combine two words such as no bye-bye and more please.[5] Three-word and four-word combinations appear when most of the child’s utterances are two-word productions. In addition, children are able to form conjoined sentences, using and.[5] This suggests that there is a vocabulary spurt between the time that the child’s first word appears, and when the child is able to form more than two words, and eventually, sentences. However, there have been arguments as to whether or not there is a spurt in acquisition of words. In one study of 38 children, only five of the children had an inflection point in their rate of word acquisition as opposed to a quadratic growth.[13]

Development in sign languages[edit]

The learning mechanisms involved in language acquisition are not specific to oral languages. The developmental stages in learning a sign language and an oral language are generally the same. Deaf babies who are exposed to sign language from birth will start babbling with their hands from 10 to 14 months. Just as in oral languages, manual babbling consists of a syllabic structure and is often reduplicated. The first symbolic sign is produced around the age of 1 year.[14]

Young children will simplify complex adult signs, especially those with difficult handshapes. This is likely due to fine motor control not having fully developed yet. The sign’s movement is also often proximalized: the child will articulate the sign with a body part that is closer to the torso. For example, a sign that requires bending the elbow might be produced by using the shoulder instead. This simplification is systematic in that these errors are not random, but predictable.[14]

Signers can represent the alphabet through the use of fingerspelling.[15] Children start fingerspelling as early as the age of 2.[14] However, they are not aware of the association between fingerspelling and alphabet. It is not until the age of 4 that they realize that fingerspelling consists of a fixed sequence of units.[14]

Mapping problem[edit]

In word learning, the mapping problem refers to the question of how infants attach the forms of language to the things that they experience in the world.[16] There are infinite objects, concepts, and actions in the world that words could be mapped onto.[16] Many theories have been proposed to account for the way in which the language learner successfully maps words onto the correct objects, concepts, and actions.

While domain-specific accounts of word learning argue for innate constraints that limit infants’ hypotheses about word meanings,[17] domain-general perspectives argue that word learning can be accounted for by general cognitive processes, such as learning and memory, which are not specific to language.[18] Yet other theorists have proposed social pragmatic accounts, which stress the role of caregivers in guiding infants through the word learning process.[19] According to some[who?] research, however, children are active participants in their own word learning, although caregivers may still play an important role in this process.[20][21] Recently, an emergentist coalition model has also been proposed to suggest that word learning cannot be fully attributed to a single factor. Instead, a variety of cues, including salient and social cues, may be utilized by infants at different points in their vocabulary development.[1]

Theories of constraints[edit]

Theories of word-learning constraints argue for biases or default assumptions that guide the infant through the word learning process. Constraints are outside of the infant’s control and are believed to help the infant limit their hypotheses about the meaning of words that they encounter daily.[17][22] Constraints can be considered domain-specific (unique to language).

Critics[who?] argue that theories of constraints focus on how children learn nouns, but ignore other aspects of their word learning.[23] Although constraints are useful in explaining how children limit possible meanings when learning novel words, the same constraints would eventually need to be overridden because they are not utilized in adult language.[24] For instance, adult speakers often use several terms, each term meaning something slightly different, when referring to one entity, such as a family pet. This practice would violate the mutual exclusivity constraint.[24]

Below, the most prominent constraints in the literature are detailed:

- Reference is the notion that a word symbolizes or stands in for an object, action, or event.[25] Words consistently stand for their referents, even if referents are not physically present in context.[25]

- Mutual Exclusivity is the assumption that each object in the world can only be referred to by a single label.[17][26]

- Shape has been considered to be one of the most critical properties for identifying members of an object category.[27] Infants assume that objects that have the same shape also share a name.[28] Shape plays an important role in both appropriate and inappropriate extensions.[27]

- The Whole Object Assumption is the belief that labels refer to whole objects instead of parts or properties of those objects.[17][29] Children are believed to hold this assumption because they typically label whole objects first, and parts of properties of objects later in development.[29]

- The Taxonomic Assumption reflects the belief that speakers use words to refer to categories that are internally consistent.[30] Labels to pick out coherent categories of objects, rather than those objects and the things that are related to them.[17][30] For example, children assume that the word «dog» refers to the category of «dogs», not to «dogs with bones», or «dogs chasing cats».[30]

Domain-general views[edit]

Domain-general views of vocabulary development argue that children do not need principles or constraints in order to successfully develop word-world mappings.[18] Instead, word learning can be accounted for through general learning mechanisms such as salience, association, and frequency.[18] Children are thought to notice the objects, actions, or events that are most salient in context, and then to associate them with the words that are most frequently used in their presence.[18] Additionally, research on word learning suggests that fast mapping, the rapid learning that children display after a single exposure to new information, is not specific to word learning. Children can also successfully fast map when exposed to a novel fact, remembering both words and facts after a time delay.[23]

Domain-general views have been criticized for not fully explaining how children manage to avoid mapping errors when there are numerous possible referents to which objects, actions, or events might point.[31] For instance, if biases are not present from birth, why do infants assume that labels refer to whole objects, instead of salient parts of these objects?[31] However, domain-general perspectives do not dismiss the notion of biases. Rather, they suggest biases develop through learning strategies instead of existing as built-in constraints. For instance, the whole object bias could be explained as a strategy that humans use to reason about the world; perhaps we are prone to thinking about our environment in terms of whole objects, and this strategy is not specific to the language domain.[23] Additionally, children may be exposed to cues associated with categorization by shape early in the word learning process, which would draw their attention to shape when presented with novel objects and labels.[32] Ordinary learning could, then, lead to a shape bias.[32]

[edit]

Social pragmatic theories, also in contrast to the constraints view, focus on the social context in which the infant is embedded.[19] According to this approach, environmental input removes the ambiguity of the word learning situation.[19] Cues such as the caregiver’s gaze, body language, gesture, and smile help infants to understand the meanings of words.[19] Social pragmatic theories stress the role of the caregiver in talking about objects, actions, or events that the infant is already focused-in upon.[19]

Joint attention is an important mechanism through which children learn to map words-to-world, and vice versa.[33] Adults commonly make an attempt to establish joint attention with a child before they convey something to the child. Joint attention is often accompanied by physical co-presence, since children are often focused on what is in their immediate environment.[33] As well, conversational co-presence is likely to occur; the caregiver and child typically talk together about whatever is taking place at their locus of joint attention.[33] Social pragmatic perspectives often present children as covariation detectors, who simply associate the words that they hear with whatever they are attending to in the world at the same time.[34] The co-variation detection model of joint attention seems problematic when we consider that many caregiver utterances do not refer to things that occupy the immediate attentional focus of infants. For instance, caregivers among the Kaluli, a group of indigenous peoples living in New Guinea, rarely provide labels in the context of their referents.[34] While the covariation detection model emphasizes the caregiver’s role in the meaning-making process, some theorists[who?] argue that infants also play an important role in their own word learning, actively avoiding mapping errors.[21] When infants are in situations where their own attentional focus differs from that of a speaker, they seek out information about the speaker’s focus, and then use that information to establish correct word-referent mappings.[20][34] Joint attention can be created through infant agency, in an attempt to gather information about a speaker’s intent.[34]

From early on, children also assume that language is designed for communication. Infants treat communication as a cooperative process.[35] Specifically, infants observe the principles of conventionality and contrast. According to conventionality, infants believe that for a particular meaning that they wish to convey, there is a term that everyone in the community would expect to be used.[35][36] According to contrast, infants act according to the notion that differences in form mark differences in meaning.[35][36] Children’s attention to conventionality and contrast is demonstrated in their language use, even before the age of 2 years; they direct their early words towards adult targets, repair mispronunciations quickly if possible, ask for words to relate to the world around them, and maintain contrast in their own word use.[35]

Emergentist coalition model[edit]

The emergentist coalition model suggests that children make use of multiple cues to successfully attach a novel label to a novel object.[1] The word learning situation may offer an infant combinations of social, perceptual, cognitive, and linguistic cues. While a range of cues are available from the start of word learning, it may be the case that not all cues are utilized by the infant when they begin the word learning process.[1] While younger children may only be able to detect a limited number of cues, older, more experienced word learners may be able to make use of a range of cues. For instance, young children seem to focus primarily on perceptual salience, but older children attend to the gaze of caregivers and use the focus of caregivers to direct their word mapping.[1] Therefore, this model argues that principles or cues may be present from the onset of word learning, but the use of a wide range of cues develops over time.[37]

Supporters of the emergentist coalition model argue that, as a hybrid, this model moves towards a more holistic explanation of word learning that is not captured by models with a singular focus. For instance, constraints theories typically argue that constraints/principles are available to children from the onset of word learning, but do not explain how children develop into expert speakers who are not limited by constraints.[38] Additionally, some argue[who?] that domain-general perspectives do not fully address the question of how children sort through numerous potential referents in order to correctly sort out meaning.[38] Lastly, social pragmatic theories claim that social encounters guide word learning. Although these theories describe how children become more advanced word learners, they seem to tell us little about children’s capacities at the start of word learning.[38] According to its proponents, the emergentist coalition model incorporates constraints/principles, but argues for the development and change in these principles over time, while simultaneously taking into consideration social aspects of word learning alongside other cues, such as salience.[39]

Pragmatic development[edit]

Both linguistic and socio-cultural factors affect the rate at which vocabulary develops.[40] Children must learn to use their words appropriately and strategically in social situations.[41] They have flexible and powerful social-cognitive skills that allow them to understand the communicative intentions of others in a wide variety of interactive situations. Children learn new words in communicative situations.[42] Children rely on pragmatic skills to build more extensive vocabularies.[43] Some aspects of pragmatic behaviour can predict later literacy and mathematical achievement, as children who are pragmatically skilled often function better in school. These children are also generally better liked.[44]

Children use words differently for objects, spatial relations and actions. Children ages one to three often rely on general purpose deictic words such as «here», «that» or «look» accompanied by a gesture, which is most often pointing, to pick out specific objects.[43] Children also stretch already known or partly known words to cover other objects that appear similar to the original. This can result in word overextension or misuses of words. Word overextension is governed by the perceptual similarities children notice among the different referents. Misuses of words indirectly provide ways of finding out which meanings children have attached to particular words.[43] When children come into contact with spatial relations, they talk about the location of one object with respect to another. They name the object located and use a deictic term, such as here or «there» for location, or they name both the object located and its location. They can also use a general purpose locative marker, which is a preposition, postposition or suffix depending on the language that is linked in some way to the word for location.[43] Children’s earliest words for actions usually encode both the action and its result. Children use a small number of general purpose verbs, such as «do» and «make» for a large variety of actions because their resources are limited. Children acquiring a second language seem to use the same production strategies for talking about actions. Sometimes children use a highly specific verb instead of a general purpose verb. In both cases children stretch their resources to communicate what they want to say.[43]

Infants use words to communicate early in life and their communication skills develop as they grow older. Communication skills aid in word learning. Infants learn to take turns while communicating with adults. While preschoolers lack precise timing and rely on obvious speaker cues, older children are more precise in their timing and take fewer long pauses.[45] Children get better at initiating and sustaining coherent conversations as they age. Toddlers and preschoolers use strategies such as repeating and recasting their partners’ utterances to keep the conversation going. Older children add new relevant information to conversations. Connectives such as then, so, and because are more frequently used as children get older.[46] When giving and responding to feedback, preschoolers are inconsistent, but around the age of six, children can mark corrections with phrases and head nods to indicate their continued attention. As children continue to age they provide more constructive interpretations back to listeners, which helps prompt conversations.[47]

Pragmatic influences[edit]

Caregivers use language to help children become competent members of society and culture. From birth, infants receive pragmatic information. They learn structure of conversations from early interactions with caregivers. Actions and speech are organized in games, such as peekaboo to provide children with information about words and phrases. Caregivers find many ways to help infants interact and respond. As children advance and participate more actively in interactions, caregivers adapt their interactions accordingly.[48] Caregivers also prompt children to produce correct pragmatic behaviours. They provide input about what children are expected to say, how to speak, when they should speak, and how they can stay on topic. Caregivers may model the appropriate behaviour, using verbal reinforcement, posing a hypothetical situation, addressing children’s comments, or evaluating another person.[49]

Family members contribute to pragmatic development in different ways. Fathers often act as secondary caregivers, and may know the child less intimately. Older siblings may lack the capacity to acknowledge the child’s needs. As a result, both fathers and siblings may pressure children to communicate more clearly. They often challenge children to improve their communication skills, therefore preparing them to communicate with strangers about unfamiliar topics. Fathers have more breakdowns when communicating with infants, and spend less time focused on the same objects or actions as infants. Siblings are more directive and less responsive to infants, which motivates infants to participate in conversations with their older siblings.[50] There are limitations to studies that focus on the influences of fathers and siblings, as most research is descriptive and correlational. In reality, there are many variations of family configurations, and context influences parent behaviour more than parent gender does.[51] The majority of research in this field is conducted with mother/child pairs.

Peers help expose children to multi-party conversations. This allows children to hear a greater variety of speech, and to observe different conversational roles. Peers may be uncooperative conversation partners, which pressures the children to communicate more effectively. Speaking to peers is different from speaking to adults, but children may still correct their peers. Peer interaction provides children with a different experience filled with special humour, disagreements and conversational topics.[44]

Culture and context in infants’ linguistic environment shape their vocabulary development. English learners have been found to map novel labels to objects more reliably than to actions compared to Mandarin learners. This early noun bias in English learners is caused by the culturally reinforced tendency for English speaking caregivers to engage in a significant amount of ostensive labelling as well as noun-friendly activities such as picture book reading.[52] Adult speech provides children with grammatical input. Both Mandarin and Cantonese languages have a category of grammatical function word called a noun classifier, which is also common across many genetically unrelated East Asian languages. In Cantonese, classifiers are obligatory and specific in more situations than in Mandarin. This accounts for the research found on Mandarin-speaking children outperforming Cantonese-speaking children in relation to the size of their vocabulary.[40]

Pragmatic directions[edit]

Pragmatic directions provide children with additional information about the speaker’s intended meaning. Children’s learning of new word meanings is guided by the pragmatic directions that adults offer, such as explicit links to word meanings.[53] Adults present young children with information about how words are related to each other through connections, such as «is a part of», «is a kind of», «belongs to», or «is used for». These pragmatic directions provide children with essential information about language, allowing them to make inferences about possible meanings for unfamiliar words.[54] This is also called inclusion. When children are provided with two words related by inclusion, they hold on to that information. When children hear an adult say an incorrect word, and then repair their mistake by stating the correct word, children take into account the repair when assigning meanings to the two words.[53]

In school-age children[edit]

Children in school share an interactive reading experience.

Vocabulary development during the school years builds upon what the child already knows, and the child uses this knowledge to broaden their vocabulary. Once children have gained a level of vocabulary knowledge, new words are learned through explanations using familiar, or «old» words. This is done either explicitly, when a new word is defined using old words, or implicitly, when the word is set in the context of old words so that the meaning of the new word is constrained.[55] When children reach school-age, context and implicit learning are the most common ways in which their vocabularies continue to develop.[56] By this time, children learn new vocabulary mostly through conversation and reading.[57] Throughout schooling and adulthood, conversation and reading are the main methods in which vocabulary develops. This growth tends to slow once a person finishes schooling, as they have already acquired the vocabulary used in everyday conversation and reading material and generally are not engaging in activities that require additional vocabulary development.[55][58]

During the first few years of life, children are mastering concrete words such as «car», «bottle», «dog», «cat». By age 3, children are likely able to learn these concrete words without the need for a visual reference, so word learning tends to accelerate around this age.[59] Once children reach school-age, they learn abstract words (e.g. «love», «freedom», «success»).[60] This broadens the vocabulary available for children to learn, which helps to account for the increase in word learning evident at school age.[61] By age 5, children tend to have an expressive vocabulary of 2,100–2,200 words. By age 6, they have approximately 2,600 words of expressive vocabulary and 20,000–24,000 words of receptive vocabulary.[62] Some claim that children experience a sudden acceleration in word learning, upwards of 20 words per day,[58] but it tends to be much more gradual than this. From age 6 to 8, the average child in school is learning 6–7 words per day, and from age 8 to 10, approximately 12 words per day.[23]

Means[edit]

Exposure to conversations and engaging in conversation with others help school-age children develop vocabulary. Fast mapping is the process of learning a new concept upon a single exposure and is used in word learning not only by infants and toddlers, but by preschool children and adults as well.[23] This principle is very useful for word learning in conversational settings, as words tend not to be explained explicitly in conversation, but may be referred to frequently throughout the span of a conversation.

Reading is considered to be a key element of vocabulary development in school-age children.[55][62][63][64] Before children are able to read on their own, children can learn from others reading to them. Learning vocabulary from these experiences includes using context, as well as explicit explanations of words and/or events in the story.[65] This may be done using illustrations in the book to guide explanation and provide a visual reference or comparisons, usually to prior knowledge and past experiences.[66] Interactions between the adult and the child often include the child’s repetition of the new word back to the adult.[67] When a child begins to learn to read, their print vocabulary and oral vocabulary tend to be the same, as children use their vocabulary knowledge to match verbal forms of words with written forms. These two forms of vocabulary are usually equal up until grade 3. Because written language is much more diverse than spoken language, print vocabulary begins to expand beyond oral vocabulary.[68] By age 10, children’s vocabulary development through reading moves away from learning concrete words to learning abstract words.[69]

Generally, both conversation and reading involve at least one of the four principles of context that are used in word learning and vocabulary development: physical context, prior knowledge, social context and semantic support.[70]

Physical context[edit]

Physical context involves the presence of an object or action that is also the topic of conversation. With the use of physical context, the child is exposed to both the words and a visual reference of the word. This is frequently used with infants and toddlers, but can be very beneficial for school-age children, especially when learning rare or infrequently used words.[64] Physical context may include props such as in toy play. When engaging in play with an adult, a child’s vocabulary is developed through discussion of the toys, such as naming the object (e.g. «dinosaur») or labeling it with the use of a rare word (e.g., stegosaurus).[70] These sorts of interactions expose the child to words they may not otherwise encounter in day-to-day conversation.

Prior knowledge[edit]

Past experiences or general knowledge is often called upon in conversation, so it is a useful context for children to learn words. Recalling past experiences allows the child to call upon their own visual, tactical, oral, and/or auditory references.[70] For example, if a child once went to a zoo and saw an elephant, but did not know the word elephant, an adult could later help the child recall this event, describing the size and color of the animal, how big its ears were, its trunk, and the sound it made, then using the word elephant to refer to the animal. Calling upon prior knowledge is used not only in conversation, but often in book reading as well to help explain what is happening in a story by relating it back to the child’s own experiences.[71]

[edit]

Social context involves pointing out social norms and violations of these norms.[72] This form of context is most commonly found in conversation, as opposed to reading or other word learning environments. A child’s understanding of social norms can help them to infer the meaning of words that occur in conversation. In an English-speaking tradition, «please» and «thank you» are taught to children at a very early age, so they are very familiar to the child by school-age. For example, if a group of people is eating a meal with the child present and one person says, «give me the bread» and another responds with, «that was rude. What do you say?», and the person responds with «please», the child may not know the meaning of «rude», but can infer its meaning through social context and understanding the necessity of saying «please».[72]

Semantic support[edit]

Semantic support is the most obvious method of vocabulary development in school-age children. It involves giving direct verbal information of the meaning of a word.[63][73] By the time children are in school, they are active participants in conversation, so they are very capable and willing to ask questions when they do not understand a word or concept. For example, a child might see a zebra for the first time and ask, what is that? and the parent might respond, that is a zebra. It is like a horse with stripes and it is wild so you cannot ride it.[73]

Memory[edit]

Memory plays an important role in vocabulary development, however the exact role that it plays is disputed in the literature. Specifically, short-term memory and how its capacities work with vocabulary development is questioned by many researchers[who?].

The phonology of words has proven to be beneficial to vocabulary development when children begin school. Once children have developed a vocabulary, they utilize the sounds that they already know to learn new words.[74] The phonological loop encodes, maintains and manipulates speech-based information that a person encounters. This information is then stored in the phonological memory, a part of short-term memory. Research shows that children’s capacities in the area of phonological memory are linked to vocabulary knowledge when children first begin school at age 4–5 years old. As memory capabilities tend to increase with age (between age 4 and adolescence), so does an individual’s ability to learn more complex vocabulary.[74]

Serial-order short-term memory may be critical to the development of vocabulary.[75] As lexical knowledge increases, phonological representations have to become more precise to determine the differences between similar sound words (i.e. «calm», «come»). In this theory, the specific order or sequence of phonological events is used to learn new words, rather than phonology as a whole.[75]

See also[edit]

- Semantic mapping (literacy)

- Vocabulary learning

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 145.

- ^ Tincoff & Jusczyk 1999.

- ^ Tincoff & Jusczyk 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hoff 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Hulit & Howard 2002.

- ^ Barner, Zapf & Lui 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Pinker 1994.

- ^ Waxman & Booth 2000.

- ^ Teinonen et al. 2008.

- ^ Keren-Portnoy, Majorano & Vihman 2009.

- ^ Fagan 2009.

- ^ Vihman 1993.

- ^ a b c Ganger & Brent 2004.

- ^ a b c d Emmorey 2001.

- ^ Baker 2016.

- ^ a b Bloom 2000, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e Clark 2009, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 141.

- ^ a b Baldwin 1995.

- ^ a b Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 142.

- ^ Bloom 2000, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom & Markson 1998.

- ^ a b Clark 1993, p. 53.

- ^ a b Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Merriman, Bowman & MacWhinney 1989, p. 3.

- ^ a b Clark 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 52.

- ^ a b Clark 1993, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Clark 1993, p. 52.

- ^ a b Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 144.

- ^ a b Smith 2000, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Clark 2009, p. 285.

- ^ a b c d Sabbagh & Baldwin 2005.

- ^ a b c d Clark 2009, p. 286.

- ^ a b Clark 1993, p. 64.

- ^ Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 159.

- ^ Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff & Hollich 2000, p. 160.

- ^ a b Tardif et al. 2009.

- ^ Bryant 2009, p. 339.

- ^ Tomasello 2000.

- ^ a b c d e Clark 1978.

- ^ a b Bryant 2009, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Bryant 2009, p. 342.

- ^ Bryant 2009, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Bryant 2009, pp. 343–345.

- ^ Bryant 2009, p. 348.

- ^ Bryant 2009, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Bryant 2009, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Bryant 2009, p. 351.

- ^ Chan et al. 2011.

- ^ a b Clark & Grossman 1998.

- ^ Clark & Andrew 2002.

- ^ a b c Baker, Simmons & Kameenui 1995.

- ^ Newton, Padak & Rasinski 2008, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, pp. 93–110.

- ^ a b Anglin & Miller 2000.

- ^ Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, p. 103.

- ^ Nippold 2004, pp. 1–8.

- ^ McKeown & Curtis 1987, p. 7.

- ^ a b Lorraine 2008.

- ^ a b Newton, Padak & Rasinski 2008.

- ^ a b Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Nagy, Herman & Anderson 1985.

- ^ Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, p. 101.

- ^ Kamil & Hiebert 2005.

- ^ McKeown & Curtis 1987, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, p. 105.

- ^ Newton, Padak & Rasinski 2008, pp. xvii.

- ^ a b Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, p. 106.

- ^ a b Tabors, Beals & Weizman 2001, pp. 107.

- ^ a b Gathercole et al. 1992.

- ^ a b Leclercq & Majerus 2010.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anglin, Jeremy M.; Miller, George A. (2000). Vocabulary Development: A Morphological Analysis. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 131–132, 136. ISBN 978-0-631-22443-3.

- Baker, Anne (2016). The linguistics of sign languages: an introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027212306. OCLC 932169688.

- Baker, S. K.; Simmons, D. C.; Kameenui, E. J. (1995). Vocabulary acquisition: Synthesis of the research. Technical Report No. 13. Eugene, OR.: National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators.

- Baldwin, D. (1995). «Understanding the link between joint attention and language». In Moore, C.; Dunham, P. J. (eds.). Joint attention: Its origins and role in development. Hillsdale, NJ: LEA. pp. 131–158.

- Barner, D.; Zapf, J.; Lui, T. (2012). «Is two a plural marker in early child language?». Developmental Psychology. 48 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1037/a0025283. PMID 21928879.

- Bloom, L. (2000). «The intentionality model of word learning: How to learn a word, any word». In Golinkoff, R. M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Bloom, L.; Smith, L. B.; Woodward, A. L.; Akhtar, N.; Hollich, G. (eds.). Becoming a word learner: A debate on lexical acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 19–50.

- Bloom, P.; Markson, L. (1998). «Capacities underlying word learning». Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2 (2): 67–73. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01121-8. PMID 21227068. S2CID 18751927.

- Bryant, J. B. (2009). «Pragmatic development». In Bavin, E. L. (ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 339–357.

- Chan, C.Y.; Tardif, T.; Chen, J.; Meng, X.; Zhu, Liqi; Meng, Xiangzhi (2011). «English- and Chinese-learning infants map novel labels to objects and actions differently». Developmental Psychology. 47 (5): 1459–1471. doi:10.1037/a0024049. PMID 21744954.

- Clark, E. V. (1978). «Strategies for communicating». Child Development. 49 (4): 953–959. doi:10.2307/1128734. JSTOR 1128734.

- Clark, E. V. (1993). The lexicon in acquisition. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–66. ISBN 978-0-521-48464-0.

- Clark, E. V. (2009). «Lexical meaning». In Bavin, E. L. (ed.). The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 283–300.

- Clark, E. V.; Andrew, D.-W., W. (2002). «Pragmatic directions about language use: Offers of words and relations». Language in Society. 31 (2): 181–212. doi:10.1017/s0047404501020152. S2CID 145266963.

- Clark, E. V.; Grossman, J. B. (1998). «Pragmatics directions and children’s word learning». Journal of Child Language. 25 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0305000997003309. PMID 9604566. S2CID 40731908.

- Emmorey, Karen (2001). Language, cognition, and the brain : insights from sign language research. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0585390606. OCLC 49570210.

- Fagan, M. (June 2009). «Mean length of utterance before words and grammar: Longitudinal trends and developmental implications of infant vocalizations». Journal of Child Language. 36 (3): 495–527. doi:10.1017/S0305000908009070. PMID 18922207. S2CID 41964944.

- Ganger, J.; Brent, M. R. (2004). «Reexamining the vocabulary spurt». Developmental Psychology. 40 (4): 621–632. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.621. PMID 15238048.

- Gathercole, S. E.; Willis, C. S.; Emslie, H.; Baddeley, A. D. (1992). «Phonological memory and vocabulary development during the early school years: A longitudinal study». Developmental Psychology. 28 (5): 887–898. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.887.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R. M.; Hollich, G. (2000). «An emergentist coalition model for word learning: Mapping words to objects is a product of the interaction of multiple cues». In Golinkoff, R. M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Bloom, L.; Smith, L. B.; Woodward, A. L.; Akhtar, N.; Hollich, G. (eds.). Becoming a word learner: A debate on lexical acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–164.

- Hoff, E. (2006). «Language Experience and Language Milestones During Early Childhood». In McCartney, K.; Phillips, D. (eds.). Blackwell Handbook of Early Childhood Development. Blackwell. pp. 233–251. doi:10.1002/9780470757703.ch12. ISBN 9780470757703.

- Hulit, L. M.; Howard, M. R. (2002). Born to talk. Toronto: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205342969.

- Kamil, M. L.; Hiebert, E. H. (2005). «Teaching and learning vocabulary: Perspectives and persistent issues». In Hiebert, E. H.; Kamil, M. L. (eds.). Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 1–26.

- Keren-Portnoy, T.; Majorano, M.; Vihman, M. M. (2009). «From phonetics to phonology: The emergence of first words in Italian» (PDF). Journal of Child Language. 36 (2): 235–267. doi:10.1017/S0305000908008933. PMID 18789180. S2CID 3119762.

- Leclercq, A.; Majerus, S. (2010). «Serial-order short-term memory predicts vocabulary development: Evidence from a longitudinal study». Developmental Psychology. 46 (2): 417–427. doi:10.1037/a0018540. hdl:2268/29034. PMID 20210500.

- Lorraine, S. (2008). Vocabulary development: Super duper handouts number 149. Greenville, SC: Super Duper Publications.[1]

- McKeown, M. G.; Curtis, M. E. (1987). The nature of vocabulary acquisition. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0-89859-548-2.

- Merriman, W. E.; Bowman, L. L.; MacWhinney, B. (1989). «The mutual exclusivity bias in children’s word learning». Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 54 (3–4, Serial No. 220): 1–30. doi:10.2307/1166130. JSTOR 1166130. PMID 2608077.

- Nagy, W. E.; Herman, P. A.; Anderson, R. C. (1985). «Learning words from context». Reading Research Quarterly. 22 (2): 233–253. doi:10.2307/747758. JSTOR 747758.

- Newton, E.; Padak, N. D.; Rasinski, T. V. (2008). Evidence-based instruction in reading: A professional development guide to vocabulary. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Nippold, M. (2004). «Research on later language development:International perspectives». In Berman, R. A. (ed.). Language Development Across Childhood and Adolescence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 1–8.

- Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. New York: Morrow and Co. pp. 262–296. ISBN 978-0-688-12141-9.

- Sabbagh, M. A.; Baldwin, D. (2005). «Understanding the role of communicative intentions in word learning». In Elain, N.; Hoerl, C.; McCormack, T.; et al. (eds.). Joint Attention: Communication and Other Minds: Issues in Philosophy and Psychology. New York: Clarendon/Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199245635.001.0001. ISBN 9780199245635.

- Smith, L. B. (2000). «Learning how to learn words: An associative crane». In Golinkoff, R. M.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Bloom, L.; Smith, L. B.; Woodward, A. L.; Akhtar, N.; Hollich, G. (eds.). Becoming a word learner: A debate on lexical acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 51–80.

- Tabors, P. O.; Beals, D. E.; Weizman, Z. O. (2001). «‘You know what oxygen is?’: Learning new words at home». In Dickinson, D. K.; Tabor, P. O. (eds.). Beginning literacy with language. Baltimore, ML: Paul H. Brookes. pp. 93–110.

- Tardif, T.; Fletcher, P.; Liang, W.; Kaciroti, N. (2009). «Early vocabulary development in Mandarin (Putonghua) and Cantonese». Journal of Child Language. 36 (5): 1115–1144. doi:10.1017/S0305000908009185. PMID 19435545. S2CID 22135359.