Reading wars, Whole word VS. Phonics, whole language advocates vs. phonetics enthusiasts…

Who would imagine that learning to read could be such a controversial topic?

But sadly, it is!

And I use the word SADLY for a good reason: Because the ones that normally pay the consequences of this disagreement are our children!

In this article we will look at the differences between the whole word approach and the phonics approach, so you can learn the ins and outs of this hot debate and form your own opinion.

If your child is learning to read, this is a crucial topic for you to understand as a parent. The reading success of your child can depend very much upon the actual approach used to teach your child to read; and, as you will discover on this article, schools do not always use the most effective method.

When it comes to teaching children to read there are two main teaching methods.

These two main methods are the whole word approach (also called the “sight words” approach) and the phonetic or phonics approach.

Some prefer the whole word method, while others use the phonics approach.

There are also educators that use a mix of different approaches.

But, who is right?

The Whole Word Approach

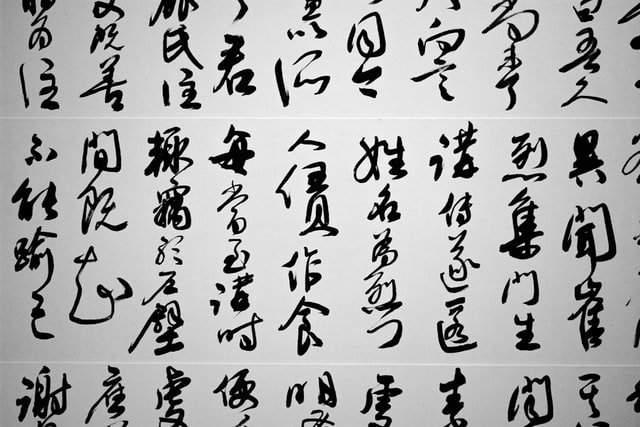

The whole word approach relies on what are called “sight words”. This method basically consists of getting children to memorize lists of words and teaching them various strategies of figuring out the text from a series of clues. Using the whole word approach, English is being taught as an ideographic language, such as Chinese or Japanese.

One of the biggest arguments of whole word advocates is that teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables which have no actual meaning. Yet they fail to acknowledge that once the child is able to decode the word, they will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning. So, in practicality, this is a very weak argument, from our point of view.

Unlike Chinese, English is an alphabet-based language. This means the letters of the English alphabet are not ideograms (also called ideographs), like Chinese characters are.

An ideogram (or ideograph) is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or a concept. Simply put, ideograms are like logos.

So, in a way, you could say that in the Chinese language you need to teach children to memorize “logos” and the meaning of each of them.

It is not logic to think that English should be taught using an ideographic approach…

So, the very popular reading programs that use a whole word approach simply get children to memorize words using different strategies, but without teaching any proper decoding methodology.

Think of the example we used before of the logos and the Chinese language.

Besides, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that teaching your child to using the whole word approach is an effective method. However, there are large numbers of studies which have consistently stated that teaching children to read using phonics and phonemic awareness is a highly effective method.

The Whole-Word Approach in Schools…

So, is your child learning to read using sight words? Or maybe a mixture of phonetics and sight words? What is the standard approach in our education system?

Well, every country – and even every educator / school – is different.

However, in English speaking countries in general -with the exception of the UK, which has been encouraging schools to adopt a systematic synthetic phonics approach since 2011- reading instruction is normally more heavily weighted towards the teaching of sight words, emphasizing the learning of “word shapes”.

Despite all the evidence to suggest otherwise, the whole word method of teaching still dominates how reading is taught at schools.

Why? Well, our guess is that children can appear to make fast progress with the whole language approach, and that makes everybody happy…

That is until their progress stalls, which is what usually happens, because with this method many children do not learn the relationships between letters and sounds correctly.

Some children can finally understand the letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned, but unfortunately many children aren’t able to figure this out. So, they are left with only one strategy for learning to read: memory and continuous repetition.

This is a very poor strategy these children are left with, in our opinion.

On the other hand, the reading ability of children is normally exaggerated on whole word programs as the texts used are very repetitive and extremely predictable. The children know what to expect. So… They are basically guessing!

When children are presented with a less predictable text without pictures, they struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text with illustrations.

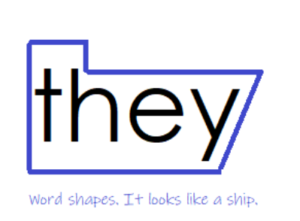

Another strategy used in whole word programs consists of focusing on word shapes.

Just have a look at this image. This is a “reading strategy” used on whole word programs.

Encouraging children to learn to read by looking at word shapes is completely madness! They are told to look at words as if they were “pictures”, focusing on the overhangs in the shapes of words! This does not apply for the English language!! Again, this is a method used for ideographic languages, such us Chinese or Japanese.

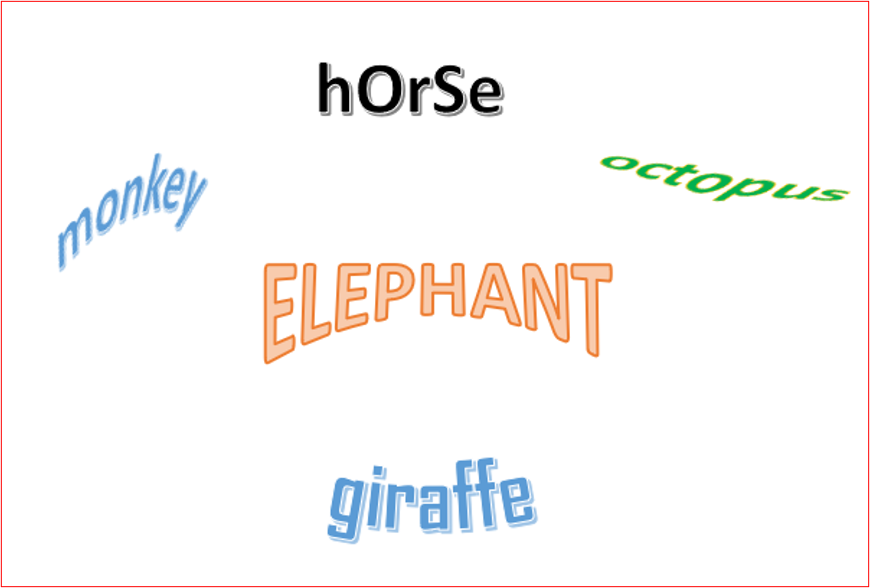

It does not make sense! There are just so many words with very similar shapes!

For example, look at this:

- hat vs. bat

- tree vs. free

- fall vs. tall vs hall

- hunt vs. hurt vs. hard

And the list goes on and on and on… Honestly, we could find thousands of words that have similar shape if we had the time to do this exercise!

The Whole- Word Method and Spelling

Even if a child has some early success learning to read using whole words programs, it gets him/her into the habit of ignoring the letters in words. This causes serious reading problems later on (when texts get more complicated), including spelling problems.

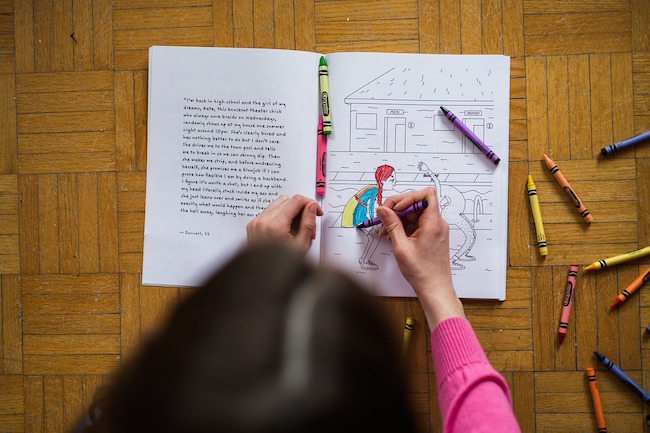

Another strategy that we are told to do on whole word programs is encouraging our children to look at the pictures in storybooks to “guess” or “predict” words.

-

Can they use the picture to help?

-

Can they look at the initial letter and predict what word would make sense that starts with that letter?

-

What word makes sense based on the context?

A little bit of history on the Whole-Word Approach

The main idea behind this theory is that if you see words enough number of times, you eventually store them in your memory as visual images.

They also embrace the idea that kids can naturally learn to read if they are exposed a lot of books.

Since the 1980s, these beliefs had strongly influenced the way children in North America and most English speaking countries are taught to read and write.

These ideas start to emerge in the 1970’s, and they become extremely popular for teaching reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

There is a strong focus on meaning, rather than sounds.

The Phonics Approach

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find reading instruction based on phonemic awareness and phonics.

The phonics approach focuses on the sounds in words, which are represented by the letters (or groups of letters) in the alphabet.

There is a myriad of methods and systems within the phonics approach itself, but the the two main methodologies for teaching phonics are Synthetic and Analytic phonics.

Even though they both have the label “Phonics” attached to them, they are in fact quite different ways for teaching children to read.

However, for the sake of this article (and to keep things simple) we will just say that the main difference is that in the Synthetic Phonics approach skills are taught in a highly structured ‘systematic’ way.

Children start with very simple sounds and decoding regular words. Gradually, they are introduced to more complex sounds (such us letter combination sounds) and to irregularities and exceptions. Every step of the way is planned, and children only move to the next stage of phonics once they have mastered the previous one.

In the Analytic Phonics approach, reading instruction is less structured, and learning happens in a more ‘embedded’ fashion. Children are encouraged to analyze groups of whole words to identify similar sounds and letter patterns. Instruction relies a lot on the analysis of “families of words”.

For instance, the family of words ending up in -all, such us “tall, fall, mall, hall, small”, or the family of words ending up in -at, such “mat, cat, rat, bat, fat, pat”.

If you are interested in knowing more about the differences between analytics and synthetic phonics, you can check this video.ç

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/twDjIsFkhFM” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Is there a Winner in the Reading Wars?

What Research / Modern Science has to say…

The best way to put an end to this controversy and start making decisions that are RIGHT for our kids – and not based on personal preferences or ideology- is by looking at what research and scientific studies have to say.

However, you may think that if opinions on the topic are still so divided, then it must be that the results of these studies are somehow inconclusive.

Well, not really…

Look at these statements by the US National Reading

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes in words was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to Phonemic Awareness.”

“Conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.”

^* Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Excerpts from the meta-analysis of over 1,900 scientific studies.

Overwhelmingly research has found that phonemic awareness and phonics is a superior way for teaching children to read!

But wait there is more…

Modern Scientific Research on the Brain and How we learn to read

For a very long time many experts have embraced the idea that we store words in our memory in the same way we store visual memories, such us faces or objects. That belief is at the core of the whole word approach.

And, in fact, many reading experts still believe this is the cse.

However, modern scientific research proves otherwise…

But before I tell you how we actually store words in our memory, look at the following factors already pointing out at how visual memory -contrary to still popular belief – is NOT involved:

-

We can read mixed case letters without difficulties.

-

We can read words with different fonts, in print and cursive, and handwritting without difficulties.

-

Word recognition works faster than object recognition, indicating that we are using different storage and retrieval processes.

Let me tell you about the sound scientific evidence now…

Brain scans show that the parts of the brain activated while performing visual memory tasks are different than the parts of the brain activated while reading…

Moreover, scientists in the visual memory area (not related to reading research, therefore unbiased) have indicated that we don’t have the cognitive capacity to remember 30 – 90,000 words for immediate retrieval.

As reading instruction still assumes that we store words as visual images, students who struggle to remember words are many times presumed to have poor visual memory.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. There is only a small relationship between visual memory and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading.

However, there is a very strong relationship between HEARING skills and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading (fluent reading capacity).

To be more specific, children that have been trained to hear the actual sounds that form words (phonemic /phonological skills) and are capable to recognize and store those common strings of sounds and visually link them to the letters / words they know become fluent readers.

There is no evidence to suggest that visual memory has a role in word recognition /reading fluency once the letters and the connection between letters and sounds have been learned.

If there seems to be a winner on the ‘Reading Wars’, why do we keep arguing?

Phonics instruction cons…

These are the main arguments against phonics instruction:

- Children only read phonics books: This is one of the main pillars of a proper phonics system. Children should only attempt to read books that are in line with their level of phonics. Otherwise, it is overwhelming for them and can get confused, since they may be exposed to too many exceptions and irregularities. While this is true, that doesn’t mean that parents can’t read more difficult books to their children. And, in fact, they are encouraged to do so.

- Phonics doesn’t help with reading comprehension. Besides, teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables, which have no actual meaning. However, once the child is able to decode the word, he/she will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning.

- Children learn to read naturally, therefore they don’t need tedious phonics instruction. Whereas it is truth that some children can learn to read by themselves, most won’t be able to figure it out. Besides, there is no harm in receiving phonics instruction for those that are able to learn to decode by themselves.

- There are just too many exceptions and irregularities in English. While it is true that English is full of irregularities and exceptions, there are less of these than what we are led to believe. Besides, there are some rules, patterns and tips and tricks that apply to those “irregular” words that certainly do help in the process of learning to read.

So, saying that phonics has won the war is quite far from what happens in reality.

As we stated at the beginning of the article, there are different ways for teaching phonics.

What our schools have evolved to do to keep both sides of the war happy is establishing a “balanced literacy” strategy that combines both whole word and phonics principles.

What in practicality ends up happening is that there is only a little bit of phonics instruction here and there, rather than a proper curriculum based on phonics.

That is an ineffective method for teaching phonics, and certainly doesn’t work. And this is precisely the sort of evidence that whole word enthusiasts hold on to.

Final thoughts on the Reading Wars

The debate is still hot. This is bizarre as, in our opinion, based on the latest scientific evidence, the number one skill that we need to develop in our children is phonemic awareness.

This way we would have far fewer students with reading difficulties.

And, after having developed strong phonological / phonemic awareness skills, using a proper phonics approach (and not just a little bit of phonics instruction here and there) seems like the way to go.

Free Resources you may be interested in!

Phonemic Awareness Activity Worksheets

Nursery Rhymes Ebook

44+ English sounds chart

List of CVC Words

Learning how to read is one of the most important things a child will do before the age of 10. That’s because everything from vocabulary growth to performance across all major subjects at school is linked to reading ability. The Phonics Method teaches children to pair sounds with letters and blend them together to master the skill of decoding.

The Whole-word Approach teaches kids to read by sight and relies upon memorization via repeat exposure to the written form of a word paired with an image and an audio. The goal of the Language Experience Method is to teach children to read words that are meaningful to them. Vocabulary can then be combined to create stories that the child relates to. Yet while there are various approaches to reading instruction, some work better than others for children who struggle with learning difficulties.

Dyslexia can cause individuals to have trouble hearing the sounds that make up words. This makes it difficult for them to sound out words in reading and to spell correctly. Dyslexic learners may therefore benefit from a method that teaches whole-word reading and deemphasizes the decoding process.

Orton-Gillingham is a multi-sensory approach that has been particularly effective for dyslexic children. It combines visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile learning to teach a program of English phonics, allowing children to proceed at a pace that suits them and their ability.

No two students will learn to read in exactly the same way, thus remaining flexible in your approach is key. It can be useful to combine methods, teach strategies and provide the right classroom accommodations, particularly for students who have specific learning differences. Remember that motivation is key and try to be patient so as to avoid introducing any negative associations with school and learning.

Learn more about motivating children to read, different kinds of dyslexia, identifying dyslexia, the Orton-Gillingham approach to reading, and strategies to help children with dyslexia in these posts.

Pre-literacy skills

Children begin acquiring the skills they need to master reading from the moment they are born. In fact, an infant as young as six months old can already distinguish between the sounds of his or her mother tongue and a foreign language and by the age of 2 has mastered enough native phonemes to regularly produce 50+ words. Between the ages of 2-3 many children learn to recognize a handful of letters.

They may enjoy singing the alphabet song and reciting nursery rhymes, which helps them develop an awareness of the different sounds that make-up English words. As fine motor skills advance, so does the ability to write, draw and copy shapes, which eventually can be combined to form letters.

There are plenty of ways parents can encourage pre-literacy skills in children, including pointing out letters, providing ample opportunities for playing with language, and fostering an interest in books. It can be helpful to ask a child about their day and talk through routines to assist with the development of narrative skills.

Visit your local library and bookstore as often as possible. The more kids read with their parents, teachers and caregivers, the more books become a familiar and favorite pastime. Young children should be encouraged to participate in reading by identifying the pictures they recognize and turning the pages.

Discover more about fostering pre-literacy skills.

1. The Phonics Method

The smallest word-part that carries meaning is a phoneme. While we typically think of letters as the building blocks of language, phonemes are the basic units of spoken language. In an alphabetic language like English, sounds are translated into letters and letter combinations in order to represent words on the page. Reading thus relies on an individual’s ability to decode words into a series of sounds. Encoding is the opposite process and is how we spell.

The Phonics Method is concerned with helping a child learn how to break words down into sounds, translate sounds into letters and combine letters to form new words. Phonemes and their corresponding letters may be taught based on their frequency in English words. Overall there are 40 English phonemes to master and different programs take different approaches to teaching them. Some materials introduce word families with rhyming words grouped together. It’s also possible to teach similarly shaped letters or similar sounding letters together.

The Phonics Method is one of the most popular and commonly used methods. In the beginning progress may be slow and reading out loud halting, but eventually the cognitive processes involved in translating between letters and sounds are automatized and become more fluent. However, English is not always spelled the way it sounds. This means some words can’t be sounded out and need to be learned through memorization.

2. The Whole-word Approach

This method teaches reading at the word level. Because it skips the decoding process, students are not sounding out words but rather learning to say the word by recognizing its written form. Context is important and providing images can help. Familiar words may initially be presented on their own, then in short sentences and eventually in longer sentences. As their vocabulary grows, children begin to extract rules and patterns that they can use to read new words.

Reading via this method is an automatic process and is sometimes called sight-reading. After many exposures to a word children will sight-read the majority of the vocabulary they encounter, only sounding out unfamiliar terms.

Sight-reading is faster and facilitates reading comprehension because it frees up cognitive attention for processing new words. That’s why it is often recommended that children learn to read high frequency English vocabulary in this way. The Dolch word list is a set of terms that make-up 50-75% of the vocabulary in English children’s books.

Learn more about teaching sight-reading and the Dolch List.

3. The Language Experience Method

Learning to read nonsense words in a black-and-white activity book is not always the most effective approach. The Language Experience Method of teaching reading is grounded in personalized learning where the words taught are different for every child. The idea is that learning words that the child is already familiar with will be easier.

Teachers and parents can then create unique stories that use a child’s preferred words in different configurations. Children can draw pictures that go with them and put them together in a folder to create a special reading book. You can look for these words in regular children’s fiction and use them to guess at the meaning of unknown words met in a context – an important comprehension strategy that will serve kids in later grades.

8 Tips for parents

No matter which method or methods you use, keep these tips in mind:

-

Read as often as possible. Develop a routine where you read a book together in the morning or in the evening. You may start by reading aloud but have the child participate by running a finger along the text. Make reading fun, include older children and reserve some family reading time where everyone sits together with their own book to read for half an hour—adults included!

-

Begin with reading material that the child is interested in. If he or she has a favorite subject, find a book full of related vocabulary to boost motivation.

-

Let the child choose his or her own book. When an individual has agency and can determine how the learning process goes, he or she is more likely to participate. Take children to libraries or bookstores and encourage them to explore books and decide what they would like to read.

-

Consider graded readers. As a child develops his or her reading ability, you will want to increase the challenge of books moving from materials that present one word per page to longer and longer sentences, and eventually, paragraph level text. If you’re not sure a book is at the right level for your child, try counting how many unfamiliar words it contains per page. You can also take the opposite approach and check to see how many Dolch words are present.

-

Talk about what you see on the page. Use books as a way to spur conversation around a topic and boost vocabulary by learning to read words that are pictured but not written. You can keep a special journal where you keep a record of the new words. They will be easier to remember because they are connected through the story.

-

Avoid comparisons with peers. Every child learns to read at his or her own pace. Reading is a personal and individual experience where a child makes meaning and learns more about how narrative works as he or she develops stronger skills.

-

Don’t put too much pressure. Forcing a child into reading when he or she is not ready can result in negative reactions and cause more harm than good.

-

Do speak with your child’s teacher. If your child doesn’t enjoy reading and struggles with decoding and/or sight reading, it may be due to a specific learning difficulty. It’s advised you first discuss it with your child’s teacher who may recommend an assessment by a specialist.

Learning difficulties

If reading is particularly challenging and your child isn’t making progress there could be a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia or ADHD that is causing the problem. Conditions like dyslexia are hereditary and it’s not unlikely that another family member will also have a hard time with reading. Visual processing, visual impairment and hearing impairment can also cause reading difficulties.

In the case of the latter, if you can’t hear the words it’s hard to identify the sounds inside them and develop an understanding of phonics. Hearing impairment based reading difficulties are a common issue in teaching children with Down syndrome to read.

Orton-Gillingham

Orton-Gillingham is an approach designed to help struggling readers. It’s based on the work of Dr. Samuel Orton and Dr. Anna Gillingham and has been in use for the past 80+ years. Orton-Gillingham allows every child to proceed at a pace that is right for him or her and introduces English phonics in a multi-sensory way.

For example, children may see a letter combination, say it aloud and trace it in the air with their finger. Rich sensory experiences help to enhance learning and can be provided using different materials like drawing in sand, dirt, shaving cream or chocolate pudding. Children may form letters using their hands or move in a rhythmic way that mimics the syllables in a word. Singing, dancing, art activities and plenty of repetition develop reading skills.

Learn more in this post on taking a multi-sensory approach to reading.

Touch-typing and multi-sensory reading

TTRS is a touch-typing program that follows the Orton-Gillingham approach and teaches reading in a multi-sensory way. Children see a word on the screen, hear it read aloud and type it. They use muscle memory in the fingers to remember spelling – which is particularly important for children who have dyslexia— and practice with high frequency words that build English phonics knowledge and decoding skills. Learning happens via bite-size modules that can be repeated as often as is needed. Progress is shown through automatized feedback and result graphs build confidence and motivation.

При обучении чтению на родном языке давно используют метод целого слова с картинкой с детьми от 2-летнего возраста. У нас в стране это известные педагоги Никитины, например. Карточка с картинкой и словом под ней, листочки с крупно написанным словом, приклееные к соответствующему предмету по всей квартире и т.п. методы и приемы. Как бы две картинки для обозначения одного предмета (один текст на двух языках). Далее игры всякие на подбор элементов (букв) составляющих слово и т.д.

Достаточно часто этот прием срабатывает и с младшими школьниками.

Но, начиная изучать иностранный язык во 2-м классе, дети уже хорошо знают, что такое буквы и зачем они , умеют читать. Буквы иностранного языка для них уже не картинка. И вот я постоянно на практике сталкиваюсь с тем, что после года-двух изучения языка (2-3 классы) в 4-м классе дети совершенно не могут прочитать ни одного нового слова — читают только те, что выучили визуально как картинку. Правильно подставить первую букву в короткие слова, если их озвучивают!. Если 6 человек из одной группы в 12 человек обращаются к репетиторам, потому что неумение читать не позволяет им нормально осваивать учебник, то это уже какие-то методические неправильности. То, что эффективно срабатывает с дошкольниками при обучении чтению на первом (родном) языке, не всегда эффективно для изучения иностранного школьниками со 2-го класса.

Нельзя рассчитывать на прекрасную память, которая позволит «сфотографировать» весь словарь. На то, что умение анализировать и находить какие-то закономерности словообразования само появится. Всему этому надо ребенка обучать, давать ему подсказки и задания, развивающие аналитический подход. Пусть он будет рассматривать слово как набор букву (звуков) в определенном порядке, как пазл, который зазвучит, если правильно сложены все его элементы и т.п. И начинать надо от простого к сложному. На мой взгляд, фонетически сложные и длинные иностранные слова должны приходить после освоения более простых и четких по звукам. В частности поэтому, я считаю неудачными такие УМК, как SPOTLIGHT или Кузовлев для 5 класса (первый год обучения).

Мне приходится учить чтению учеников 3-6 классов, и анализ причин, почему способные дети за 2-5 лет не научились читать даже весьма простые слова — понимают на слух, но не опознают в тексте и не могут их написать, «вспоминают» при наличии картинки 3-5-буквенные слова, а без картинки сразу путаются — позволяет делать вывод, что одной из важнейших причин является отказ от обычного обучения чтению и письму, в т.ч. прописному, а не только печатному. Не надо перегружать количеством, но стоит следовать принципу лучше меньше да лучше в смысле перехода к новому только после прочного усвоения старого.

Many schools are moving away from teaching children to recognise whole words to teaching them how to decode. It is important for anyone reading with children, or teaching them to read to understand why this is so significant.

The approach of teaching kids to recognise whole words is a ‘top down’ approach. It requires children to memorise the word by shape. Remember those ‘Look and Say’ days? Children would be given flash cards with words on them and expected to remember how to read and spell them. This approach has failed many, many children. Why? Because after a while, precious memory gets clogged up. Each word is memorised in isolation with no connection to any other words. The typical result of this failing approach is the ‘Year 4 slump’. Kids seem to be reading OK until Year 4 when suddenly they stop making progress. A sign that they can no longer remember more words and are completely stuck.

The decoding approach is a ‘bottom up’ approach. Kids learn to segment individual sounds in words, how these sounds are represented by letters and how to blend the sounds/letters into words. Because every word can be broken up into spellings (graphemes), the decoding route is like having a versatile box of Lego bricks that you can reassemble every time, reusing bits that you already know. So much more efficient, as it makes links between words with the same spellings and enables kids to teach themselves to read new words. This approach is supported by research. The image above demonstrates how a child would see words in a text in these two different approaches.

If we follow the Alphabetic Principle – that letters spell sounds in words – then should be consistent and teach children to decode all words, even high-frequency words (sight words). To see our graphics on how to decode high-frequency words click here

UK versions

USA versions

#decoding #phonicsreading #phonicsforkids

This approach, which is sometimes described as ‘look and say’, encourages children to learn words as whole units rather than focusing on the letters. A number of infant reading programmes use this method and many children are taught so-called sight words this way. But how effective is it?

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

Contents:

- Background Information

- Similar Words and Limited Visual Memory

- Laboratory Studies

- Brain Studies

- Eye Tracking Studies

- Classroom Studies

- Do Some Words Need to Be Learned by Sight?

- Whole Word and Spelling

- Conclusion

- Further Information

- References

Summary

- Children can appear to make fast progress with this method, but their progress usually stalls if they don’t learn the relationships between letters and sounds.

- The predictable and repetitive texts used with some whole word programmes can give an exaggerated impression of a child’s true reading ability.

- It can be easy for a child to mix up similar looking words when they use a whole word strategy.

- Learning whole words doesn’t activate the brain areas which are important for reading as much as phonics instruction does.

- Eye tracking technology shows that skilled readers focus on all the letters in words rather than the shapes or outlines.

- Reviews of classroom studies show that children make better progress when they are taught to read using phonics-based programmes rather than a whole word approach.

- Whole word instruction doesn’t help very much with spelling.

Back to contents…

Background Information

In the early stages of whole word instruction, children learn to read by recognising the shapes or outlines of words. But, according to critics, learning to recognise a significant number of words from their shapes can be a slow process.

Although children might be able to recognise a few words successfully at first, progress often slows considerably as a greater number of words are introduced.

It seems that some children can eventually figure out letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned in this way. But for those who aren’t able to do this, their only strategy for learning new words is rote learning by continuous repetition.

Some reading programmes use predictable and repetitive books to help children learn whole words, and these can give the impression that youngsters are making good progress. But it might just be that children are able to figure out patterns in the texts due to the recurring phrases. Illustrations can also make it easy for a child to guess the one or two different words on each page.

If a child is presented with a less predictable passage that doesn’t contain illustrations, he or she might struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text.

Alison Clarke has made a very good short video clip outlining the problems children would encounter if they actually attempted to read the words in these books without the help of the repetitive phrases and pictures.1

Similar Words and Limited Visual Memory

Another problem with the look and say approach is that words with similar looking outlines, like house and horse, or girl and grill can easily be mixed up.

Additionally, there seems to be a limit to the number of abstract visual symbols people can remember. Some people argue that it’s possible to learn many thousands of words without focussing on individual letters, and they often cite more visually complex writing systems like Chinese and Japanese to support their case.

However, contrary to popular belief, Chinese and Japanese writing systems have a limited number of symbols that need to be remembered, and the number of these symbols is many times smaller than the tens of thousands of words that can be found in an English dictionary.2

Back to contents…

Laboratory Studies

The difficulty of learning whole words has been demonstrated experimentally by researchers using invented alphabets with words constructed in unusual ways.

For example, one study used alternative letter symbols stacked on top of each other rather than side-to-side. A group of volunteers was asked to learn the words as whole shapes, while another group was taught how the individual letters were arranged to make the words.

The whole word/shape group made faster progress on the first day, but on following days, when new lists of words were introduced, the whole word/shape group quickly forgot the earlier words they had learned and lost ground compared to the letters group.3

Some Whole word advocates say that children eventually pick up phonics knowledge independently after they’ve learned enough words. However, although some children can do this, there is evidence that others can find it difficult to infer the associations between letters and sounds, even when they appear to have been presented in an obvious way.

For example, Byrne (1991) taught children to recognise short words by pairing them up with pictures. Examples included ‘fat’ and ‘bat’. However, in a subsequent test, when they were asked to judge whether a printed word said ‘fun’ or ‘bun’, the children were unable to demonstrate that they had figured out the sounds represented by the first letters.4

In a detailed article published by the American Psychological Society in 2001, researchers who considered the evidence from laboratory studies concluded:

“… learning correspondences between letters and sounds is more productive (so there is more transfer to new words) than learning whole words, even though learning whole words may be faster at first.” 4

Back to contents…

Brain Studies

Stanford Professor, Bruce McCandliss found that beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the brain areas that are engaged the most by skilled readers (regions in the left hemisphere).

In contrast, these brain regions are not activated to the same degree when readers focus on learning whole words.5

So it appears that different teaching strategies for reading have different neural impacts, and that teaching phonics is better at activating the brain areas that are most important for skilled reading.

“… strong left hemisphere engagement during early word recognition is a hallmark of skilled readers, and is characteristically lacking in children and adults who are struggling with reading.” 5

Stanislas Dehaene, a neuroscientist who specializes in reading and number sense, very much favours “a strong phonics approach” to teaching reading and he is against whole-word or whole-language approaches. His opinion is based on his expert knowledge of the research in this area:

“… analysis of how reading operates at the brain level provides no support for the notion that words are recognized globally by their overall shape or contour. Rather, letters and groups of letters … are the units of recognition.” 6

Back to contents…

Eye Tracking Studies

Experiments have been done using sophisticated technology that tracks the detailed movements of a person’s eyes when they are reading. These experiments confirm the findings from brain studies (mentioned above) which showed that we process the individual letters in words when we read, rather than the outlines or shapes of words.7

This can even be demonstrated without sophisticated technology by changing the outlines of words.

For example, you can probably read each of the words below even though we’ve made various adjustments to alter their normal appearance:

The cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene has written:

“… our visual system pays no attention to the contours of words or to the pattern of ascending and descending letters: it is only interested in the letters they contain. … our capacity to recognize words does not depend on an analysis of their overall shape.”

Dehaene, S. (2009), Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, Penguin Books.

Studies have also revealed that all the letters in a word are processed by skilled readers, not just the first or last letters.

Back to contents…

Classroom Studies

There has been a lot of research done on reading instruction over the past few decades and there have been several extensive independent reviews of this research in some of the main English speaking countries.

Every one of these major reviews has concluded that children make better progress when they are taught to read using phonics-based programmes rather than a whole word approach. See our article, ‘Is Phonics the Best Way to Teach a Child to Read?‘ for more information on these reviews.

Back to contents…

Do Some Words Need to Be Learned By Sight?

Words that appear a lot in children’s literature are sometimes called ‘high-frequency words’. Some educators encourage children to learn high-frequency words as whole words and they refer to them as ‘sight words‘.

The idea is that kids will learn to read faster if they focus on learning high-frequency words ‘by sight’ rather than learning to decode them using the letter-sound relationships taught in phonics lessons. This argument sounds logical enough but we’re inclined to disagree with it.

Although the strategy gives the illusion of fast progress there is a negative trade-off because time spent learning whole words by sight means less time spent learning the principles of phonics.

Even if a child has some early success learning whole words, this could get them into a habit of ignoring the letters, which could cause serious problems later on. It’s a bit like building a house without proper foundations – it goes up quicker, but cracks will soon begin to appear and the finished product won’t be up to standard.

Promoters of the sight word strategy often point out that there are lots of high-frequency words with irregular spellings, which are more difficult to read using phonics rules. However, around half of the most common words are completely regular and the vast majority of the others contain some regular letter-sound correspondences. Research shows that children are better at reading irregular words after they have developed a sound foundation in phonics.

Completely irregular words are very rare. The word ‘eye’ is one of the most often quoted examples, but even this is similar to other common words such as ‘bye’ and ‘dye’. And even for the most irregular words, letter patterns still need to be learned before a child will be able to spell them correctly (see Whole Word and Spelling below). Consequently, it would be a mistake to rely on memorising the outline of irregular words without paying any attention to the individual letters.

See our articles ‘Common Objections To Phonics’ and ‘Should I Teach My Child Sight Words?’ for a more detailed discussion of this point.

Back to contents…

Whole Word and Spelling

Although this article is about learning to read, it’s important to be aware that the way a child is taught to read can also have a significant impact on their future spelling ability.

Whole word instruction does very little to help children get to grips with spelling. That’s because the most efficient way to spell is by considering the individual sounds in a word and the letters that represent those sounds. With whole word, children only really focus on the outlines or shapes of words.

Some teachers do encourage children to say the letter names too, but saying the letter names (rather than the sounds) is an inefficient way to learn spellings.

Click on the following link if you would like to know more about teaching spelling with phonics.

Back to contents…

Conclusion

Although some children can learn to read by starting off with a whole word approach, evidence from a variety of sources suggests that it is more effective to use phonics as the main method of instruction.

Phonics takes more time to show results in the early stages, but children will become better readers and spellers in the long-run if they are taught phonics explicitly and systematically.

“Getting children to learn sight words is like throwing them some fish. Helping them to learn phonics is like teaching them how to fish.”

If you want to teach your child to read for free, you should find some of the links below helpful.

Further Information…

Click on the following link if you would like to learn more about teaching your child to read using phonics.

Another way to learn more about phonics is to register with some of the specialist reading programmes that offer free trials.

For example:

Parents and teachers can register for a 30-day free trial with Reading Eggs. This allows you to access over 500 highly interactive games and fun animations for developing Phonemic awareness, Phonics, Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension.

A 30-day free trial is also available from ABCmouse.com. This is a leading online educational website for children ages 2–8. With more than 9,000 interactive learning activities that teach reading, math, science, art, music, and more.

Although it’s not quite free, you can get a 30-day trial with the award-winning Hooked on Phonics programme for just $1.

IXL Learning cover 8000 skills in 5 subjects including phonics and reading comprehension. You can click on the following link to access a 7-day free trial if you live in the US.

If you live outside of the US you can get 20% off a month’s subscription if you click on the ad. below:

References

- Clarke, A. Spelfabet, Predictable or repetitive texts: https://www.spelfabet.com.au/2015/08/predictable-or-repetitive-texts/

- Look and Say, dyslexics.org.uk: https://www.dyslexics.org.uk/look-and-say-whole-language-teacher-training/

- Nurture a Reader Blog. Learning Words as Whole: An Experiment (Oct. 2011). Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention, Stanislaus Dehaene (pp. 225-226): http://nurtureareader.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/learning-words-as-whole-experiment.html

- Study sourced from Rayner, K. et al. (2001), HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE INFORMS THE TEACHING OF READING. American Psychological Society. VOL. 2, NO. 2, NOVEMBER 2001

- Stanford study on brain waves shows how different teaching methods affect reading development: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2015/may/reading-brain-phonics-052815.html

- Source: Human Neuroplasticity and Education Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Scripta Varia 117, Vatican City 2011.

- McConkie & Rayner, 1975; Rayner, 1975; Rayner & Bertera, 1979. Study sourced from Rayner, K. et al. (2001), HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE INFORMS THE TEACHING OF READING. American Psychological Society. VOL. 2, NO. 2, NOVEMBER 2001

This post may contain affiliate links. Affiliate links use cookies to track clicks and qualifying purchases for earnings. Please read my Disclosure Policy, Terms of Service, and Privacy policy for specific details.

Two techniques to teach reading include 1) using phonics to decode words and 2) recognizing whole words by sight. Whole word reading programs have fewer prerequisite skills in comparison to decoding reading programs. CLICK HERE to read an overview of the prerequisite skills for learning to read. This article is a round-up of whole word reading methods and curriculum posts.

First assess a child’s readiness for whole word reading methods.

The prerequisite skills for learning to read using whole word programs include being able to discriminate the differences between the groups of letters that form words.

CLICK HERE to for instructions on evaluating prerequisite visual discrimination skills.

Next select a curriculum or instructional method.

Published Curriculum

Edmark

Edmark is a complete whole word reading program. Word recognition, sentence fluency, and comprehension are all covered in this curriculum.

CLICK HERE to read my complete review of the Edmark Reading Curriculum.

Instructional Methods

Fernald Method

CLICK HERE to read about how to implement this approach. This approach is appropriate for individuals with severe reading disabilities.

Time Delay

Time delay is an instructional procedure that can be used to teach high frequency sight words or other selected whole words. This approach to teaching whole words has been demonstrated as effective in research (Knight, Ross, & Taylor, 2003; Ledford, Gast, Luscre, & Ayres, 2008; Redhair, McCoy, Zucker, Mathur, & Caterina, 2013).

CLICK HERE to read an overview of how to implement time delay. One of the included time delay examples is for math facts. The exact same procedure can be applied to teaching whole words.

Stimulus Fading

CLICK HERE to read about how to use the stimulus fading approach.

Time Delay vs. Stimulus Fading

Both time delay and stimulus fading are research based methods for teaching children to read whole words. The materials for time delay procedures are easy to create. Stimulus fading materials require more sophisticated computer skills, namely knowing how to use a paint app or editing program to 1) superimpose words over an image and 2) fade out the image. Both time delay and stimulus fading are easy to implement once you have your materials ready. The main advantage of a time delay procedure is ease of implementation. One advantage of a stimulus fading procedure is that a child may incidentally learn new words. Redhair, McCoy, Zucker, Mathur, & Caterino (2013) found that children may learn knew words from exposure to the word superimposed over a cooresponding image prior to actually teaching the new word.

Conclusion

Whole word methods are commonly used to teach children to read high frequency sight words. They may also be used to improve overall reading ability and fluency alone, or in combination with a phonics based reading program.

References

Knight, M. G., Ross, D. E., & Taylor, R. L. (2003). Constant time delay and interspersed of known items to teach sight words to students with mental retardation and learning disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 179-191.

Ledford, J. R., Gast, D. L., Luscre, D., & Ayres, K. M. (2008). Observational and incidental learning by children with autism during small group instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 86–103.

Redhair, E. I., McCoy, K. M., Zucker, S. H., Mathur, S. R., & Caterino, L. (2013). Identification of printed nonsense words for an individual with autism: A comparison of constant time delay and stimulus fading. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 351-362.

It has been interesting to read about the evolution of education in America. During the eighteenth century, education moved from the home into schools and textbooks were created to help teachers tutor their students in the basics like reading and math. The McGuffy Readers were among the first of these easy-to-read books that are now called a basal reading series.

At that time, first and second grade books were specifically written to include stories that emphasized the sounds of letters in words. Teaching in the eighteenth century tended to be teacher-centered with students doing a lot of rote memorization.

Around the beginning of the twentieth entury, the Progressive Education Movement introduced instruction that focused more on the interests of students and what research was discovering about teaching and learning.

More and more stories began to emphasize particular sounds and other targeted reading strategies. Sometime in the 1950s a “whole word” approach to teaching reading began to be used – returning students once again to rote memorization.

So what is the problem with this whole word memorization approach? The best answer I can find is this analogy by Steve Waller. Reading music (phonics reading) versus playing by ear (whole word reading).

You can read faster by whole word reading just as you can play music faster by playing by ear.

But you can read more difficult passages by reading phonetically just as you can play more difficult music by reading music.

You can spell better with phonics just as you can write music better if you can read music.

Listed here are some other challenges associated with whole word reading:

Pronouncing Unfamiliar Written Words

If a whole word reader looks up a written word in the dictionary, they can define it but still can’t pronounce the word because the dictionary pronunciation keys have little or no meaning. Dictionaries don’t help whole word readers with pronunciation.

Spelling

Whole word readers are frequently and understandably poor spellers. Without the skills of phonics, what spelling mechanism can be applied to a word not already memorized? How would a whole word reader know that a spelling mistake has been made? It makes sense that a whole word reader must either guess or substitute an alternative word, one with a known spelling.

Phonics does not ensure perfect spelling. More and more English words are adopted from other languages. However, additional reading strategies and skills, like marking can resolve most, if not all, spelling challenges.

Dictionaries

Whole word readers are not inclined to use dictionaries. This tends to limit their vocabulary to written and spoken words they already know, words they were taught when they were learning to read or words that they needed to learn by whatever non-phonetic method the student was forced to utilize in school or work.

Motivation to Read

New and difficult words are a chore to read or hear because the resources that would make pronunciation or comprehension easier are not very helpful for whole word readers. New spoken words cannot even be noted down for later investigation because it cannot be spelled. Whole word readers need spoken words written for them and written words spoken for them.

Research has been conclusive that explicit phonics instruction is the most effective. The U.S. Department of Education, the National Research Council, and the National Reading Panel have all conducted research and have released finding reports that support this statement. The National Reading Panel’s report on its quantitative research studies on areas of reading instruction was published in 2000. The panel reported that several reading skills are critical to becoming good readers: phonics for word identification, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

What is the “Real Books” or whole word method?

Over the 200 years or so of mainstream education, literacy has been a constant point of failure. While people often believe there was a golden time when “children at least learnt to read” at school, it is not true. Our current situation of 1 in 5 children being unable to read well at the age of 11 is as good as it has ever been.

And over the years almost everything has been tried.

I have mentioned why synthetic phonics struggles and why analytical phonics does not work, for the most at-risk children, elsewhere.

So, desperate to find a solution, educators and politicians are seduced by the arguments of the believers in Real Books literacy and Look and Say. That is natural because the logic is attractive.

What they say is that:

“Phonics is very boring. If children are bored it is difficult to teach them anything.There is such wonderful stuff within a book that we must get them involved in that, using great content and intriguing pictures. Then, through natural curiousity, the child will begin to pick up the way text works.”

So, this involves using interesting picture books, putting labels on everything in sight and a bit of Look and Say coaching.

Look and Say is effectively flashcard coaching of frequent words. It is a form of whole word sight-memorization. And it does not work.

The problems with whole word reading

The idea is lovely and, as with any reading system, around 50% of children will pick up literacy in this way. But for the rest of the class it is a disaster. Literacy levels in Real Books classes can drop to 60% because it feeds into the most common error many children make when learning to read – sight-memorization.

Many bright children can sight-memorize all the simple little words presented in “early reader” books. And they think that is reading, naturally enough.

However, once the vocabulary being used increases, this approach begins to collapse in on the child. And they usually reach the age of 7 or 8 on a reading plateau, with a declining sense of confidence.

However, DM Easyread does take the best parts of the Real Books approach and uses them. We get children reading interesting text as soon as possible with our TrainerText visual phonics system.

Table of Contents

- What is whole language learning?

- What is whole word reading?

- What is the phonics alphabet?

- What phonics should I teach first?

- What are the 44 phonics sounds?

- What are the 20 vowel sounds?

- What are the 12 vowel sounds in English?

- What are the 12 vowels?

- What are the 7 vowels?

- What are the 8 diphthongs?

- What’s a diphthong example?

- What are 2 vowels together called?

- What words are diphthongs?

- What is the difference between vowels and diphthongs?

- Is it A or a Digraph?

- Is there a rule for EE or EA?

- What is the 2 vowel rule?

- Are double letters Digraphs?

- Is the a Trigraph?

- What order should I teach Digraphs?

- What are the 5 Digraphs?

The whole language approach provides children learning to read with more than one way to work out unfamiliar words. They can begin with decoding—breaking the word into its parts and trying to sound them out and then blend them together.

What is whole language learning?

In whole language, meaning is paramount. Rather than learning phonics skills out of context, children are taught about the parts of language while they pursue “authentic” reading and writing. … Children learn spoken language through being immersed in a world of talk—without carefully sequenced instruction.

What is whole word reading?

The Whole–word Approach teaches kids to read by sight and relies upon memorization via repeat exposure to the written form of a word paired with an image and an audio. The goal of the Language Experience Method is to teach children to read words that are meaningful to them.

What is the phonics alphabet?

Phonics is a method of teaching children to read by linking sounds (phonemes) and the symbols that represent them (graphemes, or letter groups). Phonics is the learning-to-read method used in primary schools in the UK today.

What phonics should I teach first?

In first grade, phonics lessons start with the most common single-letter graphemes and digraphs (ch, sh, th, wh, and ck). Continue to practice words with short vowels and teach trigraphs (tch, dge). When students are proficient with earlier skills, teach consonant blends (such as tr, cl, and sp).

What are the 44 phonics sounds?

Consonants

| Phoneme | IPA Symbol | Graphemes |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | dʒ | j, ge, g, dge, di, gg |

| 7 | k | k, c, ch, cc, lk, qu ,q(u), ck, x |

| 8 | l | l, ll |

| 9 | m | m, mm, mb, mn, lm |

What are the 20 vowel sounds?

English has 20 vowel sounds. Short vowels in the IPA are /ɪ/-pit, /e/-pet, /æ/-pat, /ʌ/-cut, /ʊ/-put, /ɒ/-dog, /ə/-about. Long vowels in the IPA are /i:/-week, /ɑ:/-hard,/ɔ:/-fork,/ɜ:/-heard, /u:/-boot.

What are the 12 vowel sounds in English?

Vowel Sounds

- Vowel Sounds.

- Monophthongs. /i:/ /ɪ/ /e/ /æ/ /a:/ /ɒ/ /ᴐ:/ /ʊ/ /u:/ /ʌ/ /ɜ:/ /ə/

- Diphthongs. /ɪə/ /ʊə/ /eə/ /eɪ/ /ɔɪ/ /aɪ/ /aʊ/ /əʊ/

What are the 12 vowels?

These letters are vowels in English: A, E, I, O, U, and sometimes Y. It is said that Y is “sometimes” a vowel, because the letter Y represents both vowel and consonant sounds. In the words cry, sky, fly, my and why, letter Y represents the vowel sound /aɪ/.

What are the 7 vowels?

In writing systems based on the Latin alphabet, the letters A, E, I, O, U, Y, W and sometimes others can all be used to represent vowels. However, not all of these letters represent the vowels in all languages that use this writing, or even consistently within one language.

What are the 8 diphthongs?

There are eight diphthongs commonlyused in English. They are: /eɪ/, /aɪ/,/əʊ/, /aʊ/, /ɔɪ/, /ɪə/, /eə/, and /ʊə/. 4. It is important to note that the close combination ofthe two vowels causes each of the vowels to lose itspure quality./span>

What’s a diphthong example?

“Diphthong” comes from the Greek word diphthongs. … One of the best diphthong examples is the word “oil.” Here, we have two vowels working side by side and, together, they create a sound different than anything “O” or “I” alone can produce. And that’s just scratching the surface.

What are 2 vowels together called?

Vowel digraphs Sometimes, two vowels work together to form a new sound. This is called a diphthong.

What words are diphthongs?

A diphthong is a sound formed by combining two vowels in a single syllable. The sound begins as one vowel sound and moves towards another. The two most common diphthongs in the English language are the letter combination “oy”/“oi”, as in “boy” or “coin”, and “ow”/ “ou”, as in “cloud” or “cow”.

What is the difference between vowels and diphthongs?

Pure vowels have just one sound. When such a vowel is spoken, the tongue remains still. By contrast, diphthongs have two sounds and the tongue must move while moving from one sound to the other.

Is it A or a Digraph?

Reading the Digraph “or” It’s far simpler to just teach a child to identify “or” as a digraph and say the /or/ sound. Furthermore, when “or” is not the /or/ sound, it represents just one sound anyway, the /er/ sound in words like work, worth and sailor, so in those cases he will be identifying it as a digraph anyway.

Is there a rule for EE or EA?

There is not a rule dictating when to use EE, EA, E at the end of a syllable, or E with a silent E to spell the long /ē/ sound. At the end of a syllable within a base word, E is most common (as in he and cedar), but EE and EA are still permitted (agree, tea), so this is not an absolute rule that lets you know for sure./span>

What is the 2 vowel rule?

Basically, the rule states that when two vowels are adjacent in a word, the first vowel is long and the second vowel is silent.

Are double letters Digraphs?

English. English has both homogeneous digraphs (doubled letters) and heterogeneous digraphs (digraphs consisting of two different letters).

Is the a Trigraph?

A trigraph is a single sound that is represented by three letters, for example: In the word ‘match’, the three letters ‘tch’ at the end make only one sound.

What order should I teach Digraphs?

Start with simple beginning and ending digraphs such as wh, ck, sh, th, and ch. Don’t forget to incorporate phonemic awareness activities while learning and practicing words with digraphs!/span>

What are the 5 Digraphs?

Common consonant digraphs include ch (church), ch (school), ng (king), ph (phone), sh (shoe), th (then), th (think), and wh (wheel)./span>