Interrogative sentence is the type of sentences, when we ask something to receive information. As declarative sentences, interrogative ones can be one-member and two-member, simple and compound. The word order in an interrogative sentence depends on the way it has been formed. For example, we can turn declarative sentence into interrogative and the word order will be the same — we will change only intonation.

For example:

Мы пойдём вечером в парк — We will go to the park tonight.

and

Мы ПОЙДЁМ вечером в парк? — WILL we GO to the park tonight?

Мы пойдём ВЕЧЕРОМ в парк? — Will we go to the park TONIGHT?

Мы пойдём вечером в ПАРК? — Will we go TO THE PARK tonight?

We raise the intonation on any part of a sentence depending on what we want to ask. In another case, the word order can be changed, if it should be done according to the norms of speech and if this option sounds more naturally. For example:

Мы пойдем в парк ВЕЧЕРОМ? — Will we go to the park TONIGHT?

sounds more naturally because along with intonation we point out the word, which we want to specify, by putting it in the end of a sentence (we pay much more attention to the words standing in the beginning and in the end of a phrase in Russian).

All interrogative sentences can be divided into 2 groups: pronominal and nonpronominal.

The first group includes those sentences where interrogative word is interrogative pronoun or adverb. In the second one — interrogative word is a content word (you can answer these questions only with «да» (yes) or «нет» (no)). There can be particles «неужели» (really), «разве» (really), «если» (if) in the second group of interrogative sentences. Here are the examples:

1. Кто съел бутерброд? — Who ate the sandwich?

2. Маша съела бутерброд? — Did Masha eat the sandwich?

The word order in the question of the first group is quite clear: a pronoun does always stand in the beginning of a sentence (if there is no inversion). An interrogative word in the second group is often in the end of a sentence.

You can find Russian language schools and teachers:

In some languages, you can ask a question by changing only the intonation in the voice. This is not enough in English. In English, there is special word order in interrogative sentences.

Therefore, in English, when we see the interrogative word order, we already understand that this is a question and not a statement!

What is the interrogative word order? This is the order in which we put the auxiliary verb first in the sentence.

Take a look at these two examples:

Statement: I know you.

Question: Do I know you?

As you can see, this interrogative order still contains the main verb after the subject. That is, the subject and predicate remain in their usual order. But in the question, the predicate has an additional part: an auxiliary verb. And this auxiliary comes first.

The auxiliary verb in an interrogative sentence plays a huge role. The auxiliary verb depends on who we ask the question, who is the subject in our question.

Does she like you?

Did you throw your ring?

Have they been there before?

Will he work here someday?

Another important function of the auxiliary verb in the question is that the auxiliary verb indicates the tense. By changing the auxiliary verb, we change the meaning of the question.

Thus, if we want to know what a person is currently doing, we ask:

Do you live here?

If we are interested in the past of this person, we ask:

Did you live here?

Or we can ask about future plans:

Will you live here?

Word Order in Interrogative Sentence With the Verb To Be

We ask a question with the verb to be using the same scheme where we put an auxiliary verb at the beginning of the question.

But the main difference between to be and other verbs is that to be has no auxiliary verbs. The verb to be acts as an auxiliary verb for itself.

So to ask a question with to be we just put to be first before the subject. Compare:

I am going to spoil the plan!

Am I going to spoil the plan?

The only exception to this rule is when we form a question with the to be verb in the future.

The verb to be in the future has the form: Will be.

To ask a question with Will be, we put only Will in the first place, and be remains in its place.

Correct: Will you be there next time?

Incorrect: Will be you there next time?

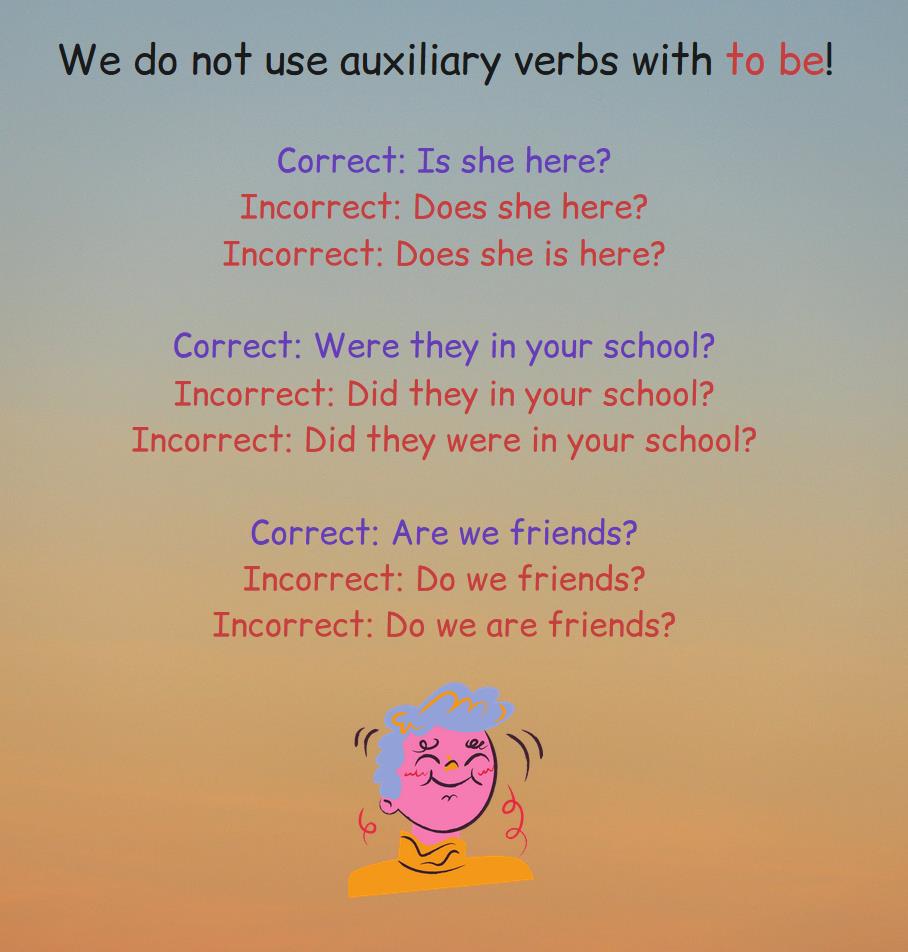

Remember that we do not use auxiliary verbs with to be. Many English learners make the mistake of using auxiliary verbs to form a question with to be.

Correct: Is she here?

Incorrect: Does she here?

Incorrect: Does she is here?Correct: Were they in your school?

Incorrect: Did they in your school?

Incorrect: Did they were in your school?Correct: Are we friends?

Incorrect: Do we friends?

Incorrect: Do we are friends?

The verb to be in questions plays the same role as auxiliary verbs with ordinary verbs. The verb to be also changes depending on who is the subject in the sentence:

Is she your girlfriend?

Were they in your old team?

Will you be working as always?

Are we the people you are looking for?

Also, the verb to be indicates the tense we are asking about:

Past: Was she your friend?

Present: Is she your friend?

Future: Will she be your friend?

Look at all forms of the verb to be not to be mistaken when you use it:

Present:

- I am

- He is

- She is

- It is

- We are

- They are

- You are

Past:

- I was

- He was

- She was

- It was

- We were

- They were

- You were

Future:

- I will be

- He will be

- She will be

- It will be

- We will be

- They will be

- You will be

Word Order in Subject Question

A subject question has exactly the same word order as an affirmative sentence. But at the beginning, we use the question word who or what.

Who broke the vase?

Who told you the truth?

What fell to the roof?

Thus, it is the word who or what that plays the role of the subject in the sentence. But we do not know who exactly is the subject, who is this person, thing, or being. Therefore, we ask a question.

Compare the usual question in which we know who the subject is and the question to the subject.

Who did she ask about it? (The subject is she)

Who asked you about it? (The subject is who)What did he throw from the roof? (The subject is he)

Who threw something from the roof? (The subject is who)Who will you take with you to the dance? (The subject is you)

Who will take you to the dance? ((The subject is who)This is your car? (The subject is you)

Whose car is this? (Subject is Whose)

Most often, we use a singular verb after the word who or what. Because by asking a question to the subject, we mean that who or what is one person or thing.

Who works here?

We can use the main verb as we do it for the plural if we and our interlocutor understand exactly that who or what in the question means several people or objects:

Who were the people you are talking about?

Word Order in Short Answer and Full Answer

A short answer to a question in English also has its own specific order.

In English, it is not customary to answer questions shortly: Yes or No.

Question: Do you like the movie?

Answer: Yes.

This answer may be considered rude.

So, in English, it is customary to form an answer in this order:

- Affirmative or negative word.

- Subject.

- Auxiliary verb.

Question: Do you like the movie?

Answer: Yes, I do.

The word order in the answer above is considered correct and polite.

A full answer is even simpler. In a full answer, we keep the order of an affirmative or negative sentence. At the beginning of the sentence, we add the affirmative or negative words Yes or No.

- Affirmative or negative word.

- Subject

- Predicate.

- Object.

Question: Do you like the movie?

Answer: Yes, I like the movie. (Yes, I like / Yes, I like it)

If the answer is no, then we add an auxiliary verb with a negative particle not. In a full negative answer, the order looks like this:

- Affirmative or negative word.

- Subject

- Auxiliary verb + not.

- Predicate.

- Object.

Question: Do you like the movie?

Answer: No, I don’t like the movie. (No, I don’t like / No, I don’t like it)

In some cases, we can add an auxiliary verb even in an affirmative full answer if we want to emphasize the main verb.

Question: Do you like the movie?

Answer: Yes, I do like the movie.

In this example, the verb do underlines the main verb like. Such an answer seems to mean:

Yes, I really like the movie.

Word Order in Interrogative Sentences

Interrogative Sentences — вопросительные предложения — в английском языке представлены четырьмя типами вопросов: общими, специальными, альтернативными и разъединительными. Все виды вопросительных предложений, кроме специального вопроса к подлежащему, характеризуются частично инвертированным порядком слов.

| Вопросительное слово |

Вспомогательный, связочный или модальный глагол |

Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Обстоятельство |

| Общие вопросы | |||||

| Do | you | study | at the Institute? | ||

| Does | your friend | tell | you about his studies | when you meet him? | |

| Did | you | translate | the new text | yesterday? | |

| Will | Prof. Sokolov | deliver | a lecture | at the club tomorrow? | |

| Can | you | speak | English | well? | |

| Is | your friend | a student? | |||

| Was | this text | translated | by you | at the last lesson? |

| Вопросительное слово |

Вспомогательный, связочный или модальный глагол |

Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Обстоятельство |

| Специальные вопросы | |||||

| Where | do | you | study? | ||

| When | does | your friend | tell | you about his studies? | |

| What | are | you? | |||

| By whom | was | this text | translated? | ||

| How often | do | students | go | to the library? | |

| What language | can | you | speak? | ||

| How many English words | do | you | know? | ||

| What | will | you | do | on Sunday? |

Примечания:

1) При вопросе к подлежащему или его определению сохраняется прямой порядок слов:

Who is speaking there?

What question has been discussed?

2) При вопросе к определению (любого члена предложения) за вопросительным словом или группой слов сразу следует существительное.

What film did you see yesterday?

How many books do you need?

3) Если вопросительное слово сопровождается предлогом, то, в отличие от русского языка, он ставится после сказуемого, а при наличии дополнения — после дополнения.

What were you speaking about when I entered?

О чем вы говорили, когда я вошел?

Примерами альтернативного и разъединительного вопросов могут служить следующие предложения:

Do you study English or German?

Вы изучаете английский язык или немецкий?

(альтернативный)

You speak French, don’t you?

Вы говорите по-французски, не так ли?

(разъединительный)

You don’t know French, do you?

Вы не знаете французского, не так ли?

(разъединительный)

Прочтение займет примерно: < 1 мин.

Правило

В английском языке чаще всего существует строгий порядок слов в вопросительном предложении.

Схема

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Вопросительное слово | Вспомогательный глагол | Подлежащее | Смысловой глагол | Дополнение | Обстоятельства |

Примеры

Пример порядка слов в утвердительном предложении.

| Вопросительное слово | Вспомогательный глагол | Подлежащее | Смысловой глагол | Другие члены предложения |

| What | do | you | like | here? |

| How often | does | she | see | him? |

| Where | did | they | go | for a holiday? |

Упражнения

Elementary

Упражнения на вопросительные предложения

Полезная статья?! Ставьте Like

Like

4

Вы можете написать нам комментарий:

Нашли описку или у вас есть дополнение, напишите нам.

Is it safe?Dr Szell, Marathon Man

Interrogative sentences are one of the four sentence types (declarative, interrogative, imperative, exclamative).

Interrogative sentences ask questions.

| form | function | example |

|---|---|---|

| auxiliary verb + subject + verb… | ask a question | Does Mary like John? |

What is the form of an interrogative sentence?

The typical form (structure) of an interrogative sentence is:

| auxiliary verb | + | subject | + | main verb | |

| Do | you | speak | English? |

| main verb BE | + | subject | |

| Were | you | cold? |

If we use a WH- word it usually goes first:

| WH-word | auxiliary verb | + | subject | + | main verb |

| When | does | the movie | start? |

The final punctuation is always a question mark (?).

Interrogative sentences can be in positive or negative form, and in any tense.

What is the function of an interrogative sentence?

The basic function (job) of an interrogative sentence is to ask a direct question. It asks us something or requests information (as opposed to a statement which tells us something or gives information). Interrogative sentences require an answer. Look at these examples:

- Is snow white? (answer → Yes.)

- Why did John arrive late? (answer → Because the traffic was bad.)

- Have any people actually met an alien? (answer → I don’t know.)

How do we use an interrogative sentence?

We use interrogative sentences frequently in spoken and written language. They are one of the most common sentence types. Here are some extremely common interrogative sentences:

- Is it cold outside?

- Are you feeling better?

- Was the film good?

- Did you like it?

- Does it taste good?

- What is your name?

- What’s the time?

- Where is the toilet please?

- Where shall we go?

- How do you open this?

There are three basic question types and they are all interrogative sentences:

- Yes/No question: the answer is «yes or no», for example:

Do you want dinner? (No thank you.) - Question-word (WH) question: the answer is «information», for example:

Where do you live? (In Paris.) - Choice question: the answer is «in the question», for example:

Do you want tea or coffee? (Tea please.)

Look at some more positive and negative examples:

| positive | negative |

|---|---|

| Does two plus two make four? Why does two plus two make four? |

Doesn’t two plus two make five? Why doesn’t two plus two make five? |

| Do you like coffee? How do you like your coffee? |

Do you not drink coffee? When do you not drink coffee? |

| Did they watch TV or go out last night? | Why didn’t you do your homework? |

| When will people go to Mars? | Why won’t they return from Mars? |

| How long have they been married for? | Haven’t they lived together for over thirty years? |

Indirect questions are not interrogative sentences

Try to recognize the difference between direct questions (in interrogative form) and indirect questions (in declarative form).

Direct question: Do you like coffee? This is an interrogative sentence, with the usual word order for direct questions: auxiliary verb + subject + main verb…

Indirect question: She asked me if I was hungry. This is a declarative sentence (and it contains an indirect question with no question mark). This sentence has the usual word order for statements: subject + main verb…

Contributor: Josef Essberger

An interrogative clause is a clause whose form is typically associated with question-like meanings. For instance, the English sentence «Is Hannah sick?» has interrogative syntax which distinguishes it from its declarative counterpart «Hannah is sick». Also, the additional question mark closing the statement assures that the reader is informed of the interrogative mood. Interrogative clauses may sometimes be embedded within a phrase, for example: «Paul knows who is sick», where the interrogative clause «who is sick» serves as complement of the embedding verb «know».

Languages vary in how they form interrogatives. When a language has a dedicated interrogative inflectional form, it is often referred to as interrogative grammatical mood.[1] Interrogative mood or other interrogative forms may be denoted by the glossing abbreviation INT.

Question types[edit]

Interrogative sentences are generally divided between yes–no questions, which ask whether or not something is the case (and invite an answer of the yes/no type), and wh-questions, which specify the information being asked about using a word like which, who, how, etc.

An intermediate form is the choice question, disjunctive question or alternative question, which presents a number of alternative answers, such as «Do you want tea or coffee?»

Negative questions are formed from negative sentences, as in «Aren’t you coming?» and «Why does he not answer?»

Tag questions are questions «tagged» onto the end of sentences to invite confirmation, as in «She left earlier, didn’t she?»

Indirect questions (or interrogative content clauses) are subordinate clauses used within sentences to refer to a question (as opposed to direct questions, which are interrogative sentences themselves). An example of an indirect question is where Jack is in the sentence «I wonder where Jack is.» English and many other languages do not use inversion in indirect questions, even though they would in the corresponding direct question («Where is Jack?»), as described in the following section.

Features[edit]

Languages may use both syntax and prosody to distinguish interrogative sentences (which pose questions) from declarative sentences (which state propositions). Syntax refers to grammatical changes, such as changing word order or adding question words; prosody refers to changes in intonation while speaking. Some languages also mark interrogatives morphologically, i.e. by inflection of the verb. A given language may use one or more of these methods in combination.

Inflection[edit]

Certain languages mark interrogative sentences by using a particular inflection of the verb (this may be described as an interrogative mood of the verb). Languages with some degree of this feature include Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Greenlandic, Nenets, Central Alaskan Yup’ik, Turkish, Finnish, Korean and Venetian.

In most varieties of Venetian, interrogative verb endings have developed out of what was originally a subject pronoun, placed after the verb in questions by way of inversion (see following section). For example, Old Venetian magnè-vu? («do you eat?», formed by inversion from vu magnè «you eat») has developed into the modern magneto? or magnèu?. This form can now also be used with overt subjects: Voaltri magnèo co mi? («do you eat with me?», literally «you eat-you with me?»).

In Turkish, the verb takes the interrogative particle mı (also mi, mu, mü according to the last vowel of the word – see vowel harmony), with other personal or verbal suffixes following after that particle:

- Geliyorum. («I am coming.») → Geliyor muyum? («Am I coming?»)

- Geliyordum. («I was coming.») → Geliyor muydum? («Was I coming?»)

- Geldim. («I came.») → Geldim mi? («Did I come?»)

- Evlisin. («You are married.») → Evli misin? («Are you married?»)

In Central Alaskan Yup’ik, verbs are conjugated in what is called the interrogative mood if one wishes to pose a content question:

- Taiciquten. («You sg. will come.») → Qaku taiciqsit? («When (future) will you come?)

- Qimugta ner’uq neqmek. («The dog is eating some fish.») → Camek ner’a qimugta? («What is the dog eating?)

Yes/no questions in Yup’ik, however, are formed by attaching the enclitic -qaa to the end of the first word of the sentence, which is what is being questioned:

- Taiciquten-qaa? («Will you come?»)

- Qimugta-qaa ner’uq neqmek? («Is the dog eating some fish?»)

Further details on verb inflection can be found in the articles on the languages listed above (or their grammars).

Syntax[edit]

The main syntactic devices used in various languages for marking questions are changes in word order and addition of interrogative words or particles.

In some modern Western European languages, questions are marked by switching the verb with the subject (inversion), thus changing the canonical word order pattern from SVO to VSO. For example, in German:

- Er liebt mich. («he loves me»; declarative)

- Liebt er mich? («does he love me?», literally «loves he me?»; interrogative)

Similar patterns are found in other Germanic languages and French. In the case of Modern English, inversion is used, but can only take place with a limited group of verbs (called auxiliaries or «special verbs»). In sentences where no such verb is otherwise present, the auxiliary do (does, did) is introduced to enable the inversion (for details see do-support, and English grammar § Questions. Formerly, up to the late 16th century, English used inversion freely with all verbs, as German still does.) For example:

- They went away. (normal declarative sentence)

- They did go away. (declarative sentence re-formed using do-support)

- Did they go away? (interrogative formed by inversion with the auxiliary did)

An inverted subject pronoun may sometimes develop into a verb ending, as described in the previous section with regard to Venetian.

Another common way of marking questions is with the use of a grammatical particle or an enclitic, to turn a statement into a yes–no question enquiring whether that statement is true. A particle may be placed at the beginning or end of the sentence, or attached to an element within the sentence. Examples of interrogative particles typically placed at the start of the sentence include the French est-ce que and Polish czy. (The English word whether behaves in this way too, but is used in indirect questions only.) The constructed language Esperanto uses the particle ĉu, which operates like the Polish czy:

- Vi estas blua. («You are blue.»)

- Ĉu vi estas blua? («Are you blue?»)

Particles typically placed at the end of the question include Japanese か ka and Mandarin 吗 ma. These are illustrated respectively in the following examples:

- 彼は日本人です Kare wa Nihon-jin desu. («He is Japanese.»)

- 彼は日本人ですか? Kare wa Nihon-jin desu ka? («Is he Japanese?»)

- 他是中國人 Tā shì Zhōngguórén. («He is Chinese.»)

- 他是中國人吗? Tā shì Zhōngguórén ma? («Is he Chinese?»)

Enclitic interrogative particles, typically placed after the first (stressed) element of the sentence, which is generally the element to which the question most strongly relates, include the Russian ли li, and the Latin nē (sometimes just n in early Latin). For example:[2]

- Tu id veritus es. («You feared that.»)

- Tu nē id veritus es? («Did you fear that?»)

This ne usually forms a neutral yes–no question, implying neither answer (except where the context makes it clear what the answer must be). However Latin also forms yes–no questions with nonne, implying that the questioner thinks the answer to be the affirmative, and with num, implying that the interrogator thinks the answer to be the negative. Examples: num negāre audēs? («You dare not deny, do you?»; Catullus 1,4,8); Mithridātēs nōnne ad Cn. Pompeium lēgātum mīsit? («Didn’t Mithridates send an ambassador to Gnaeus Pompey?»; Pompey 16,46).[3]

In Indonesian and Malay, the particle -kah is appended as a suffix, either to the last word of a sentence, or to the word or phrase that needs confirmation (that word or phrase being brought to the start of the sentence). In more formal situations, the question word apakah (formed by appending -kah to apa, «what») is frequently used.

- Kita tersesat lagi. («We are lost again.») → Kita tersesat lagikah? («Are we lost again?»)

- Jawaban saya benar. («My answer is correct.») → Benarkah jawaban saya? («Is my answer correct?»)

- Presiden sudah menerima surat itu. «The president has received the letter.» → Apakah presiden sudah menerima surat itu? («Has the president received the letter?»)

For Turkish, where the interrogative particle may be considered a part of the verbal inflection system, see the previous section.

Another way of forming yes–no questions is the A-not-A construction, found for example in Chinese,[2] which offers explicit yes or no alternatives:

- 他是中国人 Tā shì Zhōngguórén. («He is Chinese.»)

- 他不是中国人 Tā bu shì Zhōngguórén. («He is not Chinese.»)

- 他是不是中国人? Tā shì bu shì Zhōngguórén? («Is he Chinese?»; literally «He is, is not Chinese»)

Somewhat analogous to this is the method of asking questions in colloquial Indonesian, which is also similar to the use of tag questions («…, right?», «…, no?», «…, isn’t it?», etc.), as occur in English and many other languages:

- Kamu datang ke Indonesia, tidak? («Do you come to Indonesia?»; literally «You come to Indonesia, not?»)

- Dia orang Indonesia, bukan? («Is he Indonesian?»; literally «He is Indonesian, not?»)

- Mereka sudah belajar bahasa Indonesia, belum? («Have they learnt Indonesian?»; literally «They have learnt Indonesian, not?»)

Non-polar questions (wh-questions) are normally formed using an interrogative word (wh-word) such as what, where, how, etc. This generally takes the place in the syntactic structure of the sentence normally occupied by the information being sought. However, in terms of word order, the interrogative word (or the phrase it is part of) is brought to the start of the sentence (an example of wh-fronting) in many languages. Such questions may also be subject to subject–verb inversion, as with yes–no questions. Some examples for English follow:

- You are (somewhere). (declarative word order)

- Where are you? (interrogative: where is fronted, subject and verb are inverted)

- He wants (some book). (declarative)

- What book does he want? (interrogative: what book is fronted, subject and verb are inverted, using do-support)

However wh-fronting typically takes precedence over inversion: if the interrogative word is the subject or part of the subject, then it remains fronted, so inversion (which would move the subject after the verb) does not occur:

- Who likes chips?

- How many people are coming?

Not all languages have wh-fronting (and as for yes–no questions, inversion is not applicable in all languages). In Mandarin, for example, the interrogative word remains in its natural place (in situ) in the sentence:

- 你要什麼? Nǐ yào shénme? («what do you want», literally «you want what?»)

This word order is also possible in English: «You did what?» (with rising intonation). (When there is more than one interrogative word, only one of them is fronted: «Who wants to order what?») It is also possible to make yes–no questions without any grammatical marking, using only intonation (or punctuation, when writing) to differentiate questions from statements – in some languages this is the only method available. This is discussed in the following section.

Intonation and punctuation[edit]

Questions may also be indicated by a different intonation pattern. This is generally a pattern of rising intonation. It applies particularly to yes–no questions; the use of rising question intonation in yes–no questions has been suggested to be one of the universals of human languages.[4][5] With wh-questions, however, rising intonation is not so commonly used – in English, questions of this type usually do not have such an intonation pattern.

The use of intonation to mark yes–no questions is often combined with the grammatical question marking described in the previous section. For example, in the English sentence «Are you coming?», rising intonation would be expected in addition to the inversion of subject and verb. However it is also possible to indicate a question by intonation alone.[6] For example:

- You’re coming. (statement, typically spoken with falling intonation)

- You’re coming? (question, typically spoken with rising intonation)

A question like this, which has the same form (except for intonation) as a declarative sentence, is called a declarative question. In some languages this is the only available way of forming yes–no questions – they lack a way of marking such questions grammatically, and thus do so using intonation only. Examples of such languages are Italian, Modern Greek, Portuguese, and the Jakaltek language[citation needed]. Similarly in Spanish, yes–no questions are not distinguished grammatically from statements (although subject–verb inversion takes place in wh-questions).

On the other hand, it is possible for a sentence to be marked grammatically as a question, but to lack the characteristic question intonation. This often indicates a question to which no answer is expected, as with a rhetorical question. It occurs often in English in tag questions, as in «It’s too late, isn’t it?» If the tag question («isn’t it») is spoken with rising intonation, an answer is expected (the speaker is expressing doubt), while if it is spoken with falling intonation, no answer is necessarily expected and no doubt is being expressed.

Sentences can also be marked as questions when they are written down. In languages written in Latin or Cyrillic, as well as certain other scripts, a question mark at the end of the sentence identifies it as a question. In Spanish, an additional inverted mark is placed at the beginning (e.g.¿Cómo está usted?). Question marks are also used in declarative questions, as in the example given above (in this case they are equivalent to the intonation used in speech, being the only indication that the sentence is meant as a question). Question marks are sometimes omitted in rhetorical questions (the sentence given in the previous paragraph, when used in a context where it would be spoken with falling intonation, might be written «It’s too late, isn’t it.», with no final question mark).

Responses[edit]

Responses to questions are often reduced to elliptical sentences rather than full sentences, since in many cases only the information specially requested needs to be provided. (See Answer ellipsis.) Also many (but not all) languages have words that function like the English yes and no, used to give short answers to yes–no questions. In languages that do not have words compared to English yes and no, e.g. Chinese, speakers may need to answer the question according to the question. For example, when asked 喜歡喝茶嗎?(Do you like tea?), one has to answer 喜歡 (literally like) for affirmative or 不喜歡 (literally not like) for negative. But when asked 你打籃球嗎? (Do you play basketball?), one needs to answer 我打 (literally I play) for affirmative and 我不打 (literally I don’t play) for negative. There is no simple answering word for yes and no in Chinese. One needs to answer the yes-no question using the main verb in the question instead.

Responses to negative interrogative sentences can be problematic. In English, for example, the answer «No» to the question «Don’t you have a passport?» confirms the negative, i.e. it means that the responder does not have a passport. In proper context, on the other hand, it can also imply that the responder does have the passport. Most often, a native speaker would also state an indicative sentence for clarification, i.e. «No, I don’t have a passport,» or even «No, I do have a passport,» the latter most likely being used if the question were phrased, «Do you not have a passport?» which would connote serious doubt. However, in some other languages, such as Japanese, a negative answer to a negative question asserts the affirmative – in this case that the responder does have a passport. In English, «Yes» would most often assert the affirmative, though a simple, one-word answer could still be unclear, while in some other languages it would confirm the negative without doubt.[7]

Some languages have different words for «yes» when used to assert an affirmative in response to a negative question or statement; for example the French si, the German doch, and Danish, Swedish or Norwegian jo.

Ambiguity may also arise with choice questions.[8] A question like «Do you like tea or coffee?» can be interpreted as a choice question, to be answered with either «tea» or «coffee»; or it can be interpreted as a yes–no question, to be answered «yes (I do like tea or coffee)» or «no (I do not like tea or coffee)».

More information on these topics can be found in the articles Question, Yes and no, and Yes–no question.

References[edit]

- ^ Loos, Eugene E.; Susan Anderson; Dwight H. Day Jr; Paul C. Jordan; J. Douglas Wingate. «What is interrogative mood?». Glossary of linguistic terms. SIL International. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ^ a b Ljiljana Progovac (1994). Negative and Positive Polarity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-521-44480-4.

- ^ William G. Hale and Carl D. Buck (1903). A Latin Grammar. University of Alabama Press. pp. 136. ISBN 0-8173-0350-2.

- ^ Dwight L. Bolinger (ed.) (1972). Intonation. Selected Readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin, p. 314

- ^ Allan Cruttenden (1997). Intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 155-156

- ^ Alan Cruttenden (1997). Intonation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-521-59825-5.

- ^ Farkas and Roelofsen (2015)

- ^ Javier Gutiérrez-Rexach (2003). Semantics. Routledge. pp. 410–411. ISBN 0-415-26637-8.

- Классификация вопросов в английском языке

- Общие вопросы

- Альтернативные вопросы

- Специальные вопросы

- Вопросы к подлежащему

- Разделительные вопросы

- Тест по теме: «Вопросительные предложения в английском»

Классификация вопросов в английском языке

При изучении английского языка большое значение имеет синтаксис – раздел грамматики, посвященный построению предложений. Причина в том, что строй этого языка предполагает строгий порядок слов в предложении.

Задавая вопрос, недостаточно произнести предложение с вопросительной интонацией и поставить знак вопроса в конце. Вопросы формируются по определенным схемам, которые различаются в зависимости от типа вопроса.

Основные виды вопросов:

- Общий

- Альтернативный

- Специальный

- Вопрос к подлежащему

- Разделительный

Интонация зависит от типа вопроса. Общие вопросы произносятся с низким восходящим тоном в конце предложения. В специальных — интонация отличается нисходящей шкалой. Альтернативные сочетают восходящий и нисходящий тон.

Общие вопросы

К общим вопросам в английском языке относятся те, которые требуют ответа «да» или «нет». Цель вопроса – получить от собеседника подтверждение какой-либо мысли.

Does Leila have any nephews? — У Лейлы есть племянники?

Порядок слов в таких предложениях называется инверсией: то есть прямой порядок слов (подлежащее + сказуемое + второстепенные члены) нарушается. В начало вопроса выходит вспомогательный глагол.

Do you collect stamps? — Ты коллекционируешь марки?

В качестве вспомогательных глаголов могут выступать have/has, will/shall, had, was/were и модальные глаголы.

Should I call her parents? — Следует ли мне позвонить ее родителям?

Are you listening to me? — Ты меня слушаешь?

Weren’t you at the concert last night? — Разве ты не был на концерте вчера вечером?

Альтернативные вопросы

Альтернативные вопросы в английском языке очень похожи на общие по цели и структуре. Их единственное отличие – наличие двух вариантов на выбор, озвученных в самом вопросе.

Такие вопросы строятся по тому же принципу, что и общие: на первом месте стоит вспомогательный глагол, затем подлежащее, основной глагол и/или второстепенные члены. Но в структуре предложения обязательно должен быть союз «or».

Did you buy a red or a green dress? — Ты купила красное или зеленое платье?

Are you listening to me or to the radio? — Ты слушаешь меня или радио?

Специальные вопросы

Специальные вопросы задаются к одному из членов предложения, то есть цель вопроса – выяснить определенную подробность, какое-либо обстоятельство или факт.

Специальные вопросы всегда начинаются с вопросительных слов, начинающихся на «wh» (what, why, where), поэтому их называют «wh-questions».

When did you see Alice? — Когда ты видел Элис?

Предложения строятся по тому же правилу, что и общие вопросы, только первое место занимает вопросительное слово. Далее идет вспомогательный или модальный глагол, затем подлежащее, вторая часть сказуемого и/или второстепенные члены.

What are they fixing today? — Что они сегодня ремонтируют?

Where will you live during the holiday? — Где ты будешь жить во время отпуска?

Why should I listen to you? — Почему я должен слушать тебя?

Вопросы к подлежащему

Вопросы к подлежащему по сути относятся к специальным вопросам, но выделяются в отдельный блок, так как строятся по другим правилам. После вопросительного слова (Who или What) порядок слов в предложении остается прямым. Но следует обратить внимание на предложения в Present Simple. К смысловому глаголу прибавляется окончание 3л.ед.ч – «-S» или «-ES».

Who knows the answer? — Кто знает ответ?

Такой вопрос очень легко построить – вместо подлежащего ставится нужное вопросительное слово, далее порядок остается прежним.

Who came to the tutorial? — Кто пришел на урок?

What made you think about it? — Что заставило тебя об этом подумать?

Разделительные вопросы

Разделительные вопросы, которые также часто называют «tag-questions», то есть «вопросы с хвостиком», очень характерны для английского языка. Цель разделительного вопроса – уточнить информацию, получить подтверждение своей мысли, выразить сомнение или удивление.

She has three children, doesn’t she? — У нее трое детей, да?

Вопросительная часть в разделительном вопросе строится таким образом: от сказуемого в первой части предложении выделяется вспомогательный глагол, он используется с частицей «not», если основная часть утвердительная, или без частицы, если она отрицательная, далее ставится подлежащее, выраженное местоимением.

You will help me, won’t you? — Ты же поможешь мне, да?

Sarah can’t swim, can she? — Сара же не умеет плавать, так?

Тест по теме: «Вопросительные предложения в английском»

Определите тип вопросительного предложения.

General questions

In general questions, the auxiliary verb (do, be, have, will) is placed before the subject, and the main verb follows the subject, i.e., the word order is: auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier). Responses to general questions can be in the form of short «Yes» or «No» answers or in the form of full statements. (General questions are also called Yes / No questions or yes-no questions.) General questions are pronounced with rising intonation.

Do you live here? – Yes, I do. / Yes, I live here. – No, I don’t. / No, I don’t live here.

Does Bell work? – Yes, she does. – No, she doesn’t.

Did you like the film? – Yes, I did. – No, I didn’t like the film.

Are you reading now? – Yes. / Yes, I am. / Yes, I’m reading now. – No. / No, I am not. / No, I’m not reading.

Have the guests left already? – Yes, they have. – No, they haven’t.

Will you see him tomorrow? – Yes, I will. / Yes, I will see him. – No, I won’t. / No, I will not.

General questions with modal verbs have the same structure and word order.

Can you help me? – Yes, I can. / Yes, I can help you. – No, I can’t. / No, I can’t help you.

Should we call Maria? – Yes. / Yes, we should. – No. / No, we shouldn’t.

May I come in? – Yes, you may. – No, you may not.

In general questions with the verb BE as a main verb or a linking verb, the verb BE is placed before the subject.

Is he in Rome now? – Yes. / Yes, he is in Rome now. – No. / No, he isn’t.

Is Anna a teacher? – Yes, she is. / Yes, Anna is a teacher. – No, she isn’t. / No, Anna is not a teacher.

Were they happy? – Yes, they were. – No, they weren’t.

Word order in negative questions

Didn’t she like the film? – Yes, she did. / Yes, she liked the film. – No, she did not. / No, she didn’t like it.

Aren’t they reading now? – Yes, they are. / Yes, they are reading now. – No, they aren’t. / No, they are not reading now.

Isn’t he a student?

Hasn’t he left already?

Won’t you see him tomorrow?

Can’t you speak more slowly?

Note: Negative questions usually contain some emotion, for example, expecting «yes» for an answer, surprise, annoyance, mockery. Negative questions may sound impolite in some situations, for example, in requests. Read more about negative questions in Word Order in Requests and Requests and Permission in the section Grammar.

Special questions

When the question is put to any part of the sentence, except the subject, the word order after the interrogative word (e.g., how, whom, what, when, where, why) is the same as in general questions: interrogative + auxiliary verb + subject + main verb (+ object + adverbial modifier). The answer is usually given in full, but short responses are also possible. Special questions (information questions) are pronounced with falling intonation.

How did you get there? – I got there by bus. / By bus.

How much did it cost? – It cost ten dollars. / Ten dollars.

How many people did he see? – He saw five people. / Five.

How long have you been here? – I’ve been here for a week. / For a week. / A week.

Who(m) will you ask? – I’ll ask Tom. / Tom.

What is he doing? – He’s sleeping. / Sleeping.

What did she say? – Nothing.

What book is he reading? – The Talisman.

Which coat did she choose? – The red one.

When is he leaving? – He’s leaving at six. / At six.

Where does she live? – She lives on Tenth Street. / On Tenth Street.

Where are you from? – I am from Russia. / From Russia.

Where did he go? – He went home. / Home.

Why are you late? – I missed my bus.

Why didn’t you call me? – I’m sorry. I forgot.

Questions to the subject

When the interrogative word «who» or «what» is the subject in the question (i.e., the question is put to the subject), the question is asked without an auxiliary verb, and the word order is that of a statement: interrogative word (i.e., the subject) + predicate (+ object + adverbial modifier). The same word order is used when the subject of the question is in the form of which / whose / how many + noun.

Who told you about it? – Tom told me. / Tom did. / Tom.

Who called her yesterday? – I called her. / I did.

Who will tell him about it? – I will.

Who hasn’t read this book yet? – I haven’t.

What happened? – I lost my bag.

What made you do it? – I don’t know.

Which coat is yours? – This coat is mine. / This one.

Whose book is this? – It’s mine.

How many people came to work? – Ten people came to work. / Ten.

Note: «who» and «whom»

Nominative case – who; objective case – whom. The interrogative word «whom» is often replaced by «who» in everyday speech and writing, but «who» is an object in this case, not the subject, i.e., it is not a question to the subject. Consequently, an auxiliary verb is required for the formation of special questions in which «who» is used instead of «whom», and the word order in them is that of a question, not of a statement. Compare:

Who saw you? – Tom saw me.

Who / whom did you see? – I saw Anna.

Who asked her to do it? – Ben asked her.

Who / whom did she ask for help? – She asked Mike to help her.

Prepositions at the end of questions

When the interrogatives «what, whom/who» ask a question to the object with a preposition, the preposition is often placed at the end of the question after the predicate (or after the direct object, if any), especially in everyday speech.

What are you talking about? – I’m talking about our plans.

What are you interested in? – I’m interested in psychology.

Who are you looking at? – I’m looking at Sandra.

Who does it depend on? – It depends on my brother.

Who are you playing tennis with on Friday? – I’m playing tennis with Maria.

Who did she make a pie for? – She made a pie for her co-workers.

Note that not all prepositions can be placed at the end of such special questions, and the preposition at the end should not be too far from the interrogative word. In formal speech and writing, placing the preposition before the interrogative word in long constructions is often considered more appropriate. For example: With whom are you playing tennis on Friday? For whom did she make a pie?

Alternative questions

Word order in alternative questions (questions with a choice) is the same as in general questions. The answer is usually given in full because you need to make a choice, but short responses are also possible. Use the rising tone on the first element of the choice (before «or») and the falling tone on the second element of the choice.

Is your house large or small? – My house is small. / It’s small.

Are you a first-year or a third-year student? – I’m a third-year student.

Would you like tea or coffee? – I’d like coffee, please.

Would you like to go to a restaurant or would you rather eat at home? – I’d rather eat at home.

Alternative questions are sometimes asked in the form of special questions:

Where does he live: in Paris or Rome? – He lives in Rome. / In Rome.

Which do you like more: hazelnuts or walnuts? – I like hazelnuts more than walnuts. / Hazelnuts.

Tag questions

A tag question (a disjunctive question) consists of two parts. The first part is a declarative sentence (a statement). The second part is a short general question (the tag). If the statement is affirmative, the tag is negative. If the statement is negative, the tag is affirmative. Use falling intonation in the first part and rising or falling intonation in the second part of the tag question.

With the verb BE:

It’s a nice day, isn’t it?

He is here now, isn’t he?

It was true, wasn’t it?

He wasn’t invited, was he?

With main verbs:

You know him, don’t you?

He went there, didn’t he?

She will agree, won’t she?

He hasn’t seen her, has he?

He’s sleeping, isn’t he?

He didn’t study French, did he?

With modal verbs:

You can swim, can’t you?

He should go, shouldn’t he?

I shouldn’t do it, should I?

Responses to tag questions

Responses to tag questions can be in the form of short «Yes» or «No» answers or in the form of full statements. Despite the fact that tag questions are asked to get confirmation, the answer may be negative.

You live here, don’t you?

Yes, I do. / Yes, I live here. (agreement)

No, I don’t. / No, I don’t live here. (disagreement)

You don’t live here, do you?

No, I don’t. / No, I don’t live here. (agreement)

Yes, I do. / Yes, I live here. (disagreement)

It was difficult, wasn’t it?

Yes, it was. / Yes, it was difficult. (agreement)

No, it wasn’t. / No, it wasn’t difficult. (disagreement)

It wasn’t difficult, was it?

No, it wasn’t. / No, it wasn’t difficult. (agreement)

Yes, it was. / Yes, it was difficult. (disagreement)

(Intonation in different types of questions is described in Falling Intonation and Rising Intonation in the section Phonetics.)

Порядок слов в вопросах

Общие вопросы

В общих вопросах, вспомогательный глагол (do, be, have, will) ставится перед подлежащим, а основной глагол следует за подлежащим, т.е. порядок слов такой: вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство). Ответы на общие вопросы могут быть в виде кратких ответов Yes или No или в виде полных повествовательных предложений. (Общие вопросы также называются Yes / No questions или yes-no questions.) Общие вопросы произносятся с интонацией повышения.

Вы живете здесь? – Да, живу. / Да, я живу здесь. – Нет, не живу. / Нет, я не живу здесь.

Белл работает? – Да, она работает. – Нет, она не работает.

Вам понравился фильм? – Да, понравился. – Нет, мне не понравился фильм.

Вы читаете сейчас? – Да. / Да, читаю. / Да, я читаю сейчас. – Нет. / Нет, не читаю. / Нет, я не читаю.

Гости уже ушли? – Да, они ушли. – Нет, они не ушли.

Вы увидите его завтра? – Да, увижу. / Да, я увижу его. – Нет, не увижу.

Общие вопросы с модальными глаголами имеют такое же строение и порядок слов.

Вы можете мне помочь? – Да, могу. / Да, я могу помочь вам. – Нет, не могу. / Нет, я не могу помочь вам.

Следует ли нам позвонить Марии? – Да. / Да, следует. – Нет. / Нет, не следует.

Можно мне войти? – Да, можно. – Нет, нельзя.

В общих вопросах с глаголом BE как основным глаголом или глаголом-связкой, глагол BE ставится перед подлежащим.

Он сейчас в Риме? – Да. / Да, он сейчас в Риме. – Нет.

Анна учитель? – Да. / Да, Анна учитель. – Нет. / Нет, Анна не учитель.

Они были счастливы? – Да, были. – Нет, не были.

Порядок слов в отрицательных вопросах

Разве ей не понравился фильм? – Да, понравился. / Да, ей понравился фильм. – Нет, не понравился. / Нет, ей он не понравился.

Разве они не читают сейчас? – Да, читают. / Да, они читают сейчас. – Нет, не читают. / Нет, они не читают сейчас.

Разве он не студент?

Разве он уже не ушел?

Разве вы не увидите его завтра?

Разве вы не можете говорить помедленнее?

Примечание: Отрицательные вопросы обычно содержат какую-то эмоцию, например, ожидание ответа yes, удивление, раздражение, насмешку. Отрицательные вопросы могут звучать невежливо в некоторых ситуациях, например, в просьбах. Прочитайте еще об отрицательных вопросах в статьях Word Order in Requests и Requests and Permission в разделе Grammar.

Специальные вопросы

Когда вопрос ставится к любому члену предложения, кроме подлежащего, порядок слов после вопросительного слова (например, как, кого, что, когда, где, почему) такой же, как в общих вопросах: вопросительное слово + вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + основной глагол (+ дополнение + обстоятельство). Ответ обычно дается полностью, но краткие ответы тоже возможны. Специальные вопросы (информационные вопросы) произносятся с интонацией понижения.

Как вы туда добрались? – Я добрался туда автобусом. / Автобусом.

Сколько это стоило? – Это стоило десять долларов. / Десять долларов.

Сколько человек он увидел? – Он увидел пять человек. / Пять.

Сколько вы здесь пробыли? – Я пробыл здесь неделю. / Неделю. / Неделю.

Кого вы спросите? – Я спрошу Тома. / Тома.

Что он делает? – Он спит. / Спит.

Что она сказала? – Ничего.

Какую книгу он читает? – «Талисман».

Которое пальто она выбрала? – Красное.

Когда он уезжает? – Он уезжает в шесть. / В шесть.

Где она живет? – Она живет на Десятой улице. / На Десятой улице.

Откуда вы? – Я из России. / Из России.

Куда он пошел? – Он пошел домой. / Домой.

Почему вы опоздали? – Я пропустил свой автобус.

Почему вы мне не позвонили? – Извините. Я забыл.

Вопросы к подлежащему

Когда вопросительное слово who или what является подлежащим в вопросе (т.е. вопрос ставится к подлежащему), вопрос задается без вспомогательного глагола и порядок слов как в повествовательном предложении: вопросительное слово (т.е. подлежащее) + сказуемое (+ дополнение + обстоятельство). Такой же порядок слов, когда подлежащее в вопросе в виде which / whose / how many + существительное.

Кто вам сказал об этом? – Том сказал мне. / Том.

Кто ей звонил вчера? – Я звонил ей. / Я звонил.

Кто ему скажет об этом? – Я скажу.

Кто еще не прочитал эту книгу? – Я не прочитал.

Что случилось? – Я потерял свою сумку.

Что заставило вас сделать это? – Не знаю.

Которое пальто ваше? – Это пальто мое. / Вот это.

Чья это книга? – Моя.

Сколько человек пришли на работу? – Десять человек пришли на работу. / Десять.

Примечание: who и whom

Именительный падеж – who; косвенный падеж – whom. Вопросительное слово whom часто заменяется словом who в разговорной устной и письменной речи, но who в этом случае дополнение, а не подлежащее, т.е. это не вопрос к подлежащему. Следовательно, требуется вспомогательный глагол для образования специальных вопросов, в которых вопросительное слово who употреблено вместо whom, и порядок слов в них как в вопросе, а не как в повествовательном предложении. Сравните:

Кто видел вас? – Том видел меня.

Кого вы видели? – Я видел Анну.

Кто попросил ее сделать это? – Бен попросил ее.

Кого она попросила о помощи? – Она попросила Майка помочь ей.

Предлоги в конце вопросов

Когда вопросительные слова what, whom/who задают вопрос к дополнению с предлогом, предлог часто ставится в конец вопроса после сказуемого (или после прямого дополнения, если оно есть), особенно в разговорной речи.

О чем вы говорите? – Я говорю о наших планах.

Чем вы интересуетесь? – Я интересуюсь психологией.

На кого вы смотрите? – Я смотрю на Сандру.

От кого это зависит? – Это зависит от моего брата.

С кем вы играете в теннис в пятницу? – Я играю в теннис с Марией.

Для кого она сделала пирог? – Она сделала пирог для своих сотрудников.

Отметьте, что не все предлоги можно поместить в конец таких специальных вопросов, и предлог в конце предложения не должен быть слишком далеко от вопросительного слова. В официальной устной и письменной речи, помещение предлога перед вопросительным словом в длинных конструкциях часто считается более подходящим. Например: With whom are you playing tennis on Friday? For whom did she make a pie?

Альтернативные вопросы

Порядок слов в альтернативных вопросах (вопросах с выбором) такой же, как в общих вопросах. Ответ обычно дается полностью, потому что нужно сделать выбор, но краткие ответы тоже возможны. Употребите тон повышения на первом элементе выбора (перед or) и тон понижения на втором элементе выбора.

Ваш дом большой или маленький? – Мой дом маленький. / Маленький.

Вы студент первого или третьего курса? – Я студент третьего курса.

Вы хотели бы чай или кофе? – Я хотел бы кофе, пожалуйста.

Вы хотели бы пойти в ресторан или предпочли бы поесть дома? – Я предпочел бы поесть дома.

Альтернативные вопросы иногда задаются в форме специальных вопросов:

Где он живет: в Париже или Риме? – Он живет в Риме. / В Риме.

Что вы больше любите: фундук или грецкие орехи? – Я люблю фундук больше, чем грецкие орехи. / Фундук.

Разъединенные вопросы

Разъединенный вопрос (разделительный вопрос, расчлененный вопрос) состоит из двух частей. Первая часть – повествовательное предложение (утверждение). Вторая часть – краткий общий вопрос. Если повествовательное предложение утвердительное, краткий вопрос отрицательный. Если предложение отрицательное, краткий вопрос утвердительный. Употребите интонацию понижения в первой части и интонацию повышения или понижения во второй части разъединенного вопроса.

С глаголом BE:

Приятный день, не так ли?

Он здесь сейчас, не так ли?

Это была правда, не так ли?

Его не пригласили, не так ли?

С основными глаголами:

Вы знаете его, не так ли?

Он пошел туда, не так ли?

Она согласится, не так ли?

Он не видел ее, не так ли?

Он спит, не так ли?

Он не изучал французский язык, не так ли?

С модальными глаголами:

Вы можете плавать, не так ли?

Ему следует идти, не так ли?

Мне не следует этого делать, не так ли?

Ответы на разделительные вопросы

Ответы на разделительные вопросы могут быть в виде кратких ответов Yes или No или в виде полных повествовательных предложений. Несмотря на то, что разъединенные вопросы задаются для получения подтверждения, ответ может быть отрицательным.

Вы живете здесь, не так ли?

Да, живу. / Да, я живу здесь. (согласие)

Нет, не живу. / Нет, я не живу здесь. (несогласие)

Вы не живете здесь, не так ли?

Нет, не живу. / Нет, я не живу здесь. (согласие)

Нет, живу. / Нет, я живу здесь. (несогласие)

Это было трудно, не так ли?

Да, трудно. / Да, это было трудно. (согласие)

Нет, не трудно. / Нет, это было не трудно. (несогласие)

Это было не трудно, не так ли?

Нет, не трудно. / Нет, это было не трудно. (согласие)

Нет, трудно. / Нет, это было трудно. (несогласие)

(Интонация в различных типах вопросов описывается в статьях Falling Intonation и Rising Intonation в разделе Phonetics.)