Calling 2020 «unique» feels like an understatement. Many things have changed this year, from the way we work to the way we function in society, and the Oxford English Dictionary «Word of the Year» is no different. Since 2020 has been hard to put into words, Oxford Languages had to adjust how they normally do things in response to a year full of surprises they couldn’t describe succinctly. Rather than having just one word represent 2020, Oxford moved to a full list of «Words of an Unprecedented Year.» Keep reading for all of the Oxford Words of the Year, and for words we should leave behind in 2020, check out these 5 Words to Ditch From Your Vocabulary ASAP.

Generally speaking, the (usually singular) Word of the Year is chosen to reflect the year it signifies. «The Oxford Word of the Year is a word or expression that is judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of the passing year, and have lasting potential as a term of cultural significance,» Oxford Languages explains. In 2018, the Word of the Year was «toxic,» and in 2019, it was «climate emergency.»

When faced with the challenge of selecting a word to reflect this tumultuous year, Oxford Languages couldn’t pick just one. The 2020 Words of an Unprecedented Year report says, «The English language, like all of us, has had to adapt rapidly and repeatedly this year. Given the phenomenal breadth of language change and development during 2020, Oxford Languages concluded that this is a year which cannot be neatly accommodated in one single word.»

Instead, Oxford Languages assigned Words of the Year to the months in which they reached their peak frequency of usage. Here are Oxford’s 2020 Words of an Unprecedented Year, and to see what words you should ditch, here are 4 Words the Dictionary Says You Should Stop Using.

At the end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, the Australian bushfire season rolled in and became the worst in documented history. The bushfires across the country were fueled by record-breaking temperatures and lengthy bouts of severe drought. And for the etymology of other common words, discover The Amazing Origins of Everyday Slang Terms You Use Constantly.

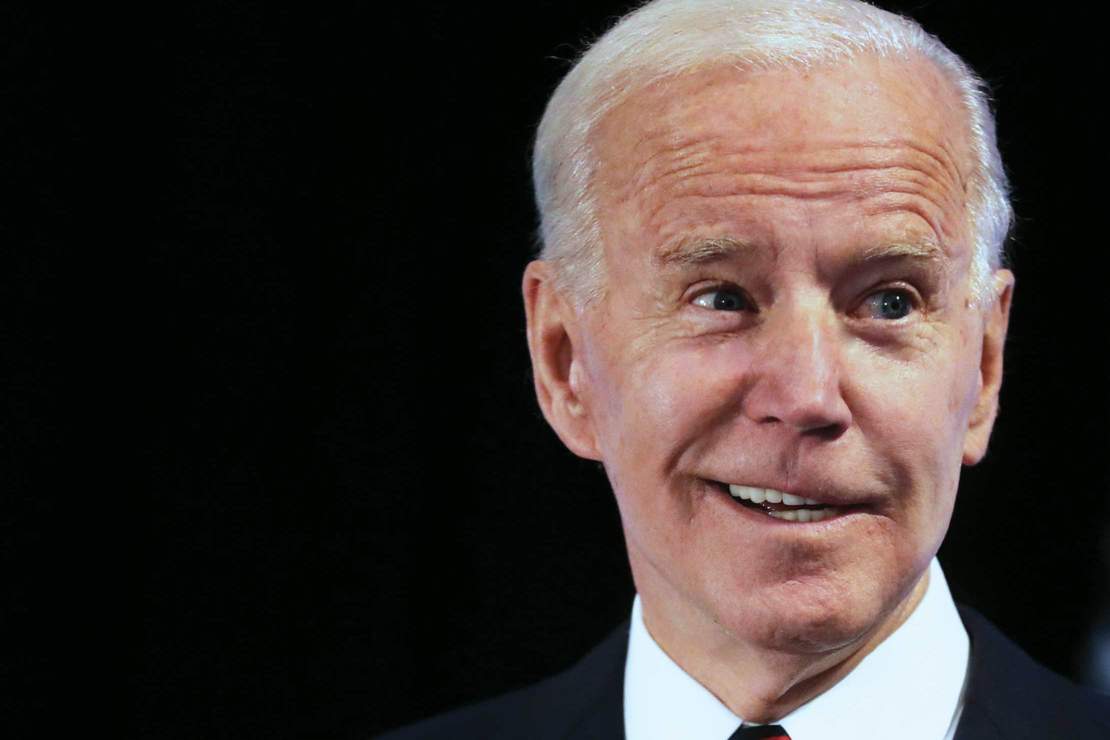

Impeachment became a hot topic in January when President Donald Trump faced an impeachment trial.

In February, following Trump’s acquittal—allowing him to remain in office, despite being impeached—this word became popular. And for more useful information delivered straight to your inbox, sign up for our daily newsletter.

By the end of March, «coronavirus» became «one of the most frequently used nouns in the English language, after being used to designate the SARS-CoV-2 virus,» according to the report.

While the word «coronavirus» already existed before the pandemic, «COVID-19» was a completely new word that reached the height of its popularity in April. According to the report, the term was first used by the World Health Organization as an abbreviation of «coronavirus disease 2019.» The term quickly became the more common designation.

In April, «lockdown» was the word on everyone’s lips as much of the world entered into government-enforced quarantine to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. And for cheerier words, check out The Most Beautiful Words in the English Language—And How to Use Them.

Governments across the globe introduced citizens to social distancing, the act of keeping six feet of distance between people to reduce the spread of COVID-19. As governments began to lift lockdown measures, the term «social distancing» spiked in popularity toward the end of April.

«Towards the Northern Hemisphere summer more hopeful words increased in frequency, including reopening,» says the report. The word «reopening» spiked in popularity in mid-May when used to refer to businesses, schools, restaurants, offices, and more that were able to open again.

The phrase «Black Lives Matter» originated in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin. However, the phrase «exploded in usage beginning in June of this year, remaining at elevated levels for the rest of the year as protests against law enforcement agencies over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black Americans took root in communities across the United States and across the world,» according to the report. And if you are committed to anti-racism, ditch these 7 Common Phrases That You Didn’t Know Have Racist Origins.

A societal shift followed the resurgence of momentum behind the Black Lives Matter movement. People in positions of power began to get called out for their actions, which led to repercussions that some dubbed «cancel culture.» According to the report, cancel culture—which saw a surge in usage in July—is «the culture of boycotting and withdrawing support from public figures whose words and actions are considered socially unacceptable.» And for words you need to stop using, find out The One Word Older People Should Never Say.

BIPOC surged in usage in tandem with Black Lives Matter—the abbreviation stands for «Black, indigenous, and other people of color.»

The 2020 election is now over, but Americans were discussing the issue of voting in a presidential election amid a pandemic back in August. The report found that the term «mail-in» saw a 3,000 percent increase in use as compared to last year.

In August, the re-election of President Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus caused an uprising in the country. The adjective «Belarusian» skyrocketed in usage as a result.

As the UK government rolled out Moonshot, their plan for mass COVID testing, in September, the term rose to significance.

According to the report, the word «superspreader» dates back to the 1970s but gained popularity in 2020. «There was a particular spike in usage in October, mainly with reference to the well-publicized spread of cases in the White House,» says the report.

The report says the term net zero has been «on the rise as the year draws to an end: the recent increase partly relates to the historic pledge made by President Xi Jinping in September, that China will be carbon neutral by 2060.»

pandemic.

Based upon a statistical analysis of words that are looked up in extremely high numbers in our online dictionary while also showing a significant year-over-year increase in traffic, Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2020 is pandemic.

No single word chosen

Oxford

| Year | UK Word of the Year |

|---|---|

| 2017 | youthquake |

| 2018 | toxic |

| 2019 | climate emergency |

| 2020 | No single word chosen |

What is 2021 word of the year?

vaccine

Merriam Webster has chosen ‘vaccine‘ as the word of the year for 2021. The word ‘vaccine’ was chosen as the word of the year by Merriam Webster, while the dictionary also stated that interest in the word has been high ever since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

What is the top word of 2020?

Pandemic

‘Pandemic‘ is Merriam-Webster’s top word of the year in 2020.

What will be the word of 2020?

Some runners-up include coronavirus, malarkey, schadenfreude, icon and kraken.

What is the word of the year 2020 according to Collins Dictionary?

What’s more, Collins Dictionary recently bestowed its word-of-the-year title on “lockdown,” while Oxford Dictionaries highlighted several terms related to COVID-19, including “pandemic” and “lockdown,” among the key words of 2020.

What is Oxford word of the year 2021?

Vax

Oxford Word of the Year 2021 | Oxford Languages. Vax is our 2021 Word of the Year. When our lexicographers began digging into our English language corpus data it quickly became apparent that vax was a particularly striking term.

What is word of the year 2022?

embrace

Scaggs says her word for 2022 is “embrace.” “And for me, the meaning behind the word is everything. I spent a lot of time thinking about the why. And I chose embrace, because as I move into this year, I want to be fully present in a moment, and each moment I find myself in.

Why is vaccine the word of the year?

The word vaccine was about much more than medicine in 2021. For many, the word symbolized a possible return to the lives we led before the pandemic. But it was also at the center of debates about personal choice, political affiliation, professional regulations, school safety, healthcare inequality, and so much more.

How do I find my word of the year?

Steps for choosing your best word of the year:

- List the things you want to focus on this year.

- Determine the common theme[s] of your list.

- List some words that would work.

- Decide which of the words on your list feels like it will be the MOST motivational.

What is the most popular word this year?

“Covid” is the top word of 2020 so far, according to Global Language Monitor, an American data-research company that tracks trends in worldwide use of the English language.

What’s the most popular word?

Top 100 words

| Rank | Word |

|---|---|

| 1 | the |

| 2 | be |

| 3 | to |

| 4 | of |

What’s the most popular word in the world?

‘The’ tops the league tables of most frequently used words in English, accounting for 5% of every 100 words used. “’The’ really is miles above everything else,” says Jonathan Culpeper, professor of linguistics at Lancaster University.

What is the meaning of UN president?

: having no precedent : novel, unexampled. Other Words from unprecedented Synonyms & Antonyms Example Sentences Learn More About unprecedented.

What are precedented times?

Welcome to Precedented Times— the show about America’s past, America’s present, and how it all seems to be repeating itself. This limited-time series tries to disprove the notion that we are living through “unprecedented times,” and host Dillon Mims turns to history to make his case.

How old is the word unprecedented?

unprecedented (adj.)

1620s, from un- (1) “not” + precedented. In common use from c. 1760.

Which word has been chosen as the word of the year 2021 according to the Collins Dictionary?

NFT

NFT has become Collins Dictionary’s word of the year for 2021. In essence, an NFT (the abbreviation for ‘non-fungible token’) is a chunk of digital data which records who a piece of digital artwork or a collectible belongs to.

What is the word of the year 2021 as per Collins Dictionary?

The word’s usage was up 11,000 per cent

Collins Dictionary has chosen the term NFT as its word of the year after surging interest in the digital tokens that can sell for millions of dollars brought it into the mainstream. NFT is short for non-fungible token.

What is the year of VAX?

Oxford’s 2021 Word of the Year Is a Shot in the Arm. Amid an explosion of Covid-related wordplay, the publisher of the Oxford English Dictionary crowns “vax.” Apologies to jab, shot and “Fauci ouchie.” Oxford Languages’s 2021 Word of the Year is “vax.” That may seem like a no-brainer.

What is the word of the year 2001?

9-11

2001: 9-11 (noun)

When did Oxford start word of the year?

The Oxford Word of the Year is a word or expression that has attracted a great deal of interest over the last 12 months.

Earlier Words of the Year.

| 2008 | credit crunch (UK) & hypermiling (US) |

| 2007 | carbon footprint (UK) & locavore (US) |

| 2006 | bovvered (UK) & carbon-neutral (US) |

| 2005 | Sudoku (UK) & podcast (US) |

| 2004 | chav |

Contents

- 1 What is the Oxford word of the year for 2020?

- 2 What is 2021 word of the year?

- 3 What is the top word of 2020?

- 4 What will be the word of 2020?

- 5 What is the word of the year 2020 according to Collins Dictionary?

- 6 What is Oxford word of the year 2021?

- 7 What is word of the year 2022?

- 8 Why is vaccine the word of the year?

- 9 How do I find my word of the year?

- 10 What is the most popular word this year?

- 11 What’s the most popular word?

- 12 What’s the most popular word in the world?

- 13 What is the meaning of UN president?

- 14 What are precedented times?

- 15 How old is the word unprecedented?

- 16 Which word has been chosen as the word of the year 2021 according to the Collins Dictionary?

- 17 What is the word of the year 2021 as per Collins Dictionary?

- 18 What is the year of VAX?

- 19 What is the word of the year 2001?

- 20 When did Oxford start word of the year?

Based upon a statistical analysis of words that are looked up in extremely high numbers in our online dictionary while also showing a significant year-over-year increase in traffic, Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2020 is pandemic.

Likewise, What was the word of the year 2020?

That word is pandemic, our 2020 Word of the Year.

Also, Which word is most used in 2020?

“Covid” is the top word of 2020 so far, according to Global Language Monitor, an American data-research company that tracks trends in worldwide use of the English language.

Secondly, What was the OED word of the year 2020?

OED Word of the Year expanded for ‘unprecedented‘ 2020.

Furthermore What is the most useful word? ‘The’ tops the league tables of most frequently used words in English, accounting for 5% of every 100 words used. “’The’ really is miles above everything else,” says Jonathan Culpeper, professor of linguistics at Lancaster University.

What is the least popular word?

Least Common English Words

- abate: reduce or lesson.

- abdicate: give up a position.

- aberration: something unusual, different from the norm.

- abhor: to really hate.

- abstain: to refrain from doing something.

- adversity: hardship, misfortune.

- aesthetic: pertaining to beauty.

- amicable: agreeable.

What are the slang words for 2020?

Here’s the latest instalment in our “slang for the year ahead” series, featuring terms that range from funny to just plain weird.

- Hate to see it. A relatable combination of cringe and disappointment, this phrase can be used as a reaction to a less than ideal situation. …

- Ok, boomer. …

- Cap. …

- Basic. …

- Retweet. …

- Fit. …

- Fr. …

- Canceled.

What words are being removed from the dictionary 2020?

These words may be removed from some dictionaries

- Aerodrome.

- Alienism.

- Bever.

- Brabble.

- Charabanc.

- Deliciate.

- Frigorific.

- Supererogate.

What word takes 3 hours to say?

METHIONYLTHREONYLTHREONYGLUTAMINYLARGINYL …

All told, the full chemical name for the human protein titin is 189,819 letters, and takes about three-and-a-half hours to pronounce.

What are the 12 powerful words?

Trace, Analyze, Infer, Evaluate, Formulate, Describe, Support, Explain, Summarize, Compare, Contrast, Predict. Why use the twelve powerful words? These are the words that always give students more trouble than others on standardized tests.

What are the three most powerful words?

It can enable you to see how God can empower your prayers, tear down hindrances to healing and open the pathway to receiving His blessings into your life. Three little words that change your future. Do you know the three most power words? According to Derek Prince, they are, ‘I forgive you.

What is the most annoying word?

The word “whatever” just tallied its twelfth consecutive year of being named the most annoying word or phrase. It received an astounding 47% of the vote, handily beating out the competition. Second place, the word “like,” gathered a mere 19% of the vote.

What is a rare word?

The 15 most unusual words you’ll ever find in English

- Serendipity. This word appears in numerous lists of untranslatable words. …

- Gobbledygook. …

- Scrumptious. …

- Agastopia. …

- Halfpace. …

- Impignorate. …

- Jentacular. …

- Nudiustertian.

What does YEET mean?

Oof: an exclamation used to sympathize with someone else’s pain or dismay, or to express one’s own. Snack: (Slang) a sexy and physically attractive person; hottie. Yeet: an exclamation of enthusiasm, approval, triumph, pleasure, joy, etc.

What does OK Boomer mean in text?

This is the latest accepted revision, reviewed on 7 August 2021. « OK boomer » is a catchphrase and Internet meme often used by teenagers and young adults to dismiss or mock attitudes typically associated with baby boomers, people born in the two decades following World War II.

Why does my kid say YEET?

Yeeting means throwing things. But it also apparently means an expression of excitement or happiness or nervousness. But you don’t always say yeet, in fact, you have it use it correctly because yeet is a verb, a noun, and a source of unending frustration for moms everywhere.

Is YEET a word?

So yeet is a word that means “to throw,” and it can be used as an exclamation while throwing something. It’s also used as a nonsense word, usually to add humor to an action or verbal response.

What is the oldest word?

Mother, bark and spit are some of the oldest known words, say researchers. … Mother, bark and spit are just three of 23 words that researchers believe date back 15,000 years, making them the oldest known words. The words, highlighted in a new PNAS paper, all come from seven language families of Europe and Asia.

Is YEET in the dictionary?

The online dictionary states that yeet can be used as “an exclamation of enthusiasm, triumph, pleasure, joy, etc.” … In addition to being an interjection, it can also be used as a verb in two ways.

What is the longest Australian word?

The longest official geographical name in Australia is Mamungkukumpurangkuntjunya. It has 26 letters and is a Pitjantjatjara word meaning « where the Devil urinates ».

What is the hardest word to say?

The Most Difficult English Word To Pronounce

- Rural.

- Otorhinolaryngologist.

- Colonel.

- Penguin.

- Sixth.

- Isthmus.

- Anemone.

- Squirrel.

What word takes 2 hours to say?

Casey Chan. The longest word in English has 189,819 letters and would take you about two hours to mumble through.

Who made the 12 powerful words?

Larry Bell, author of « The 12 Powerful Words » and a nationally-recognized educational consultant, identified twelve words that are commonly used in standardized tests that cause students’ difficulty when they encounter them.

How do you teach the 12 powerful words?

Word Short, « at-promise » student friendly phrases

- Trace List in steps.

- Analyze Break apart.

- Infer Read between the lines.

- Evaluate Judge.

- Formulate Create.

- Describe Tell all about.

- Support Back up with details.

- Explain Tell how.

Don’t forget to share this post on Facebook and Twitter !

Discover

pandemic: life upended, language transformed

2020 has been, well, a lot.

At Dictionary.com, the task of choosing a single word to sum up 2020—a year roiled by a public health crisis, an economic downturn, racial injustice, climate disaster, political division, and rampant disinformation—was a challenging and humbling one.

But at the same time, our choice was overwhelmingly clear. From our perspective as documenters of the English language, one word kept running through the profound and manifold ways our lives have been upended—and our language so rapidly transformed—in this unprecedented year.

That word is pandemic, our 2020 Word of the Year.

Can you guess which word won our People’s Choice 2020 Word of the Year contest?

How pandemic defined 2020

As most of us now know painfully well, a pandemic is defined as “a disease prevalent throughout an entire country, continent, or the whole world.” And yet, the loss of life and livelihood caused by the COVID-19 pandemic defies definition.

With over 60 million confirmed cases, the pandemic has claimed over one million lives across the globe and is still rising to new peaks. The pandemic has wreaked social and economic disruption on a historic scale and scope, globally impacting every sector of society—not to mention its emotional and psychological toll. All other events for most of 2020, from the protests for racial justice to a heated presidential election, were shaped by the pandemic. Despite its hardships, the pandemic inspired the best of our humanity: resilience and resourcefulness in the face of struggle. And we thought 2019 was an existential year …

This upheaval was reflected in our language, notably in the word pandemic itself. On March 11, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the first caused by a coronavirus. “Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly,” Director-General Tedros Adhanom observed of this momentous announcement.

That day, when COVID-19 had then only taken 4,291 lives around the world, searches for pandemic skyrocketed 13,575% on Dictionary.com compared to 2019. Pandemic joined a cluster of other terms that users searched in massive numbers, whether to learn an unfamiliar word used during a government briefing or to process the swirl of media headlines: asymptomatic, CDC, coronavirus, furlough, nonessential, quarantine, and sanitizer, to spotlight a few.

But of all these many queries, search volume for pandemic sustained the highest levels on site over the course of 2020, averaging a 1000% increase, month over month, relative to previous years. Because of its ubiquity as the defining context of 2020, it remained in the top 10% of all lookups for much of the year since.

At the start of 2020, it was unthinkable that parents would need to have a serious conversation about the word pandemic—a word which may have previously felt like a term from the history books—to their children around the dinner table. It was unfathomable that, by the year’s end, the word pandemic would become part of our everyday speech to the point of overfamiliarity, even fatigue.

How rare it is for the origin of a word—with pandemic ultimately coming from the Greek pân, “all,” and dêmos, “people”—to prove so literal. Without a doubt, the pandemic affected all of us, all over the world, in nearly all aspects of our lives.

How pandemic changed the dictionary

The pandemic defined 2020, and it will define the years to come. It is a consequential word for a consequential year.

As the pandemic upended life in 2020, it also dramatically reshaped our language, requiring a whole new vocabulary for talking about our new reality. It defined much of the work we did at Dictionary.com this year in order to meet the urgent need for information and explanation amid a fast-changing crisis.

In a period of just a few weeks in the spring, the pandemic introduced a host of new and newly prominent words that, normally, only public health professionals knew and used. Specialized lingo, spanning topics from epidemiology to social behavior, formed a shared—and ever-expanding—glossary for daily life. Besides more obvious items like COVID-19 and coronavirus, highlights include:

- asymptomatic

- contact tracing

- flatten the curve

- fomites

- frontliner

- furlough

- herd immunity

- hydroxychloroquine

- infodemic

- lockdown

- long-hauler

- essential/nonessential

- PPE

- pod

- quarantine

- shelter in place

- social distancing

- superspreader

- twindemic

- viral load

Supported by efforts of our editors to bring clarity and context to these terms and trends in articles and other content, our lexicographers updated our dictionary—twice this year—to document this extensive language change. We cannot overstate how rare it is for so many entries, so abruptly, to be added to the dictionary.

The resilience and resourcefulness people confronted the pandemic with also manifested itself in tremendous linguistic creativity. Throughout 2020, our team has been tracking a growing body of so-called coronacoinages that have given expression—and have offered some relief from tragedy, some connection in isolation—to the lived experience of a surreal year. In addition to shortened forms like rona and quar, we saw a slew of puns, blends, novel expressions, and other new words for a new normal. Corona (from coronavirus) and Zoom (from a leading video communication platform) were especially productive in forming neologisms.

- anti-masker

- bubble

- the Before Times

- cluttercore

- coronababy

- coronacation

- coronacoaster

- coronacut

- coronasomnia

- COVID-10

- covidiot

- drive-by birthday

- drive-in rally

- maskne

- quarantini

- quaranteam

- Zoom-bombing

- Zoom fatigue

- Zoom mom

- Zoom town

This outbreak of new language—matched by a surge of searches for these terms on site—is unlike anything we’ve ever seen at Dictionary.com. It takes an event on the order of a pandemic to generate such innovation. And on its own, this evolving vernacular serves as a striking timeline of life under COVID-19.

WATCH: Why Dictionary.com Chose This Word To Describe 2020

Pandemic: the defining context for 2020

While pandemic rose to the top of the many words that drove both the search and lexicographical activity on Dictionary.com this year, 2020 barraged us, month after month, with unprecedented occurrences. The experience of such a welter of uncertainty and change—even as many of us were hunkered down at home—was jolting and disorienting.

President Donald Trump was acquitted of impeachment charges. After the killing of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter sparked a powerful reckoning with racism. Record wildfires ravaged the West Coast along with other extreme climate episodes. Americans voted, early and by mail like never before, in an impassioned presidential election.

This year was a lot to handle, and as our data shows, our users, in one form or another, tried to do so by looking up the terms surrounding these major events on our site in significant numbers.

Still, all of this took place in the context of—on account of, in spite of, in a now faraway-seeming world prior to—the COVID-19 pandemic. Everything from news headlines to advertisements to casual speech registered the totality of the pandemic by framing all of the events in terms of before, during, amid, and since the pandemic. We applied pandemic as a modifier in novel ways: pandemic teaching, pandemic fashion, pandemic baking, or pandemic depression, for instance, characterize how these activities altered during life in the time of COVID-19.

Year in Review: 2020 Trends By Month

To acknowledge the multitude of other terms that directed our users’ interests and our work as a dictionary, we think it’s worth reviewing notable words that spiked or spoke to the unrest and transformation of this indelible year. But in revisiting all these terms, it’s unmistakable that the COVID-19 pandemic was the turning point and throughline for all the events of the entire year.

-

Word of the Year:

Pandemic

Sometimes a single word defines an era, and it’s fitting that in this exceptional—and exceptionally difficult—year, a single word came immediately to the fore as we examined the data that determines what our Word of the Year will be.

Based upon a statistical analysis of words that are looked up in extremely high numbers in our online dictionary while also showing a significant year-over-year increase in traffic, Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2020 is pandemic.

The first big spike in dictionary lookups for pandemic took place on February 3rd, the same day that the first COVID-19 patient in the U.S. was released from a Seattle hospital. That day, pandemic was looked up 1,621% more than it had been a year previous, but close inspection of the dictionary data shows that searches for the word had begun to tick up consistently starting on January 20th, the date of the first positive case in the U.S.

People were clearly paying attention to the news and to early descriptions of the nature of this disease. That initial February spike in lookups didn’t fall off—it grew. By early March, the word was being looked up an average of 4,000% over 2019 levels. As news coverage continued, alarm among the public was rising.

On March 11th, the World Health Organization officially declared “that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic,” and this is the day that pandemic saw the single largest spike in dictionary traffic in 2020, showing an increase of 115,806% over lookups on that day in 2019. What is most striking about this word is that it has remained high in our lookups ever since, staying near the top of our word list for the past ten months—even as searches for other related terms, such as coronavirus and COVID-19, have waned.

Pandemic is defined as:

an outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area (such as multiple countries or continents) and typically affects a significant proportion of the population

The Greek roots of this word tell a clear story: pan means “all” or “every,” and dēmos means “people”; its literal meaning is “of all the people.” The related word epidemic comes from roots that mean “on or upon the people.” The two words are used in ways that overlap, but in general usage a pandemic is an epidemic that has escalated to affect a large area and population.

The dēmos of these words is also the etymological root of democracy.

This has been a year unlike any other (the word unprecedented also had a significant spike in March), and pandemic is the word that has connected the worldwide medical emergency to the political response and to our personal experience of it all.

-

Rarely has a word moved from the jargon of medical professionals to the general public’s everyday vocabulary as quickly as coronavirus. Though not a new word, coronavirus rocketed from obscurity to ubiquity in a span of a few weeks.

The word was largely ignored as the year began, but that changed on January 20th, with the announcement of the first U.S. case of COVID-19. The largest spike in lookups came on March 19th; overall, coronavirus was looked up a staggering 162,551% more this year than in 2019.

A coronavirus is an RNA virus that was given its name in 1968 by a group of research virologists who noticed that, under a microscope, the virus resembled a solar corona visible during an eclipse (corona is the Latin word for “crown”). Both SARS and MERS are examples of coronaviruses.

The current pandemic is caused by a new, or novel, type of coronavirus dubbed COVID-19 in February. The name stands for “coronavirus disease 2019,” and was added to our dictionary in a special release of new words in March, giving COVID-19 the distinction of being the fastest term to go from coinage to inclusion in a Merriam-Webster dictionary—the process took only 34 days.

-

Protests in response to the killing of Black people by police officers punctuated the year, and a word from those protests rose in lookups beginning in June: defund. The word was key in the many conversations about how to address police violence, as activists called for the defunding of police forces, and others tried to understand what that in practicality would mean. Overall, defund was looked up 6,059% more in 2020 than in 2019.

We define defund as “to withdraw funding from.” The word is a recent addition to English, in use only since the middle of the 20th century.

-

In January, the world lost one of basketball’s greats: Kobe Bryant, along with nine other people including one of Bryant’s daughters, died in a helicopter crash. As news of the crash spread, dictionary users searched for a word strongly associated with the player: mamba. “Black Mamba,” he was called—a nickname the player had chosen for himself more than a decade before.

Mamba refers to “any of several chiefly arboreal venomous green or black elapid snakes (genus Dendroaspis) of sub-Saharan Africa,” and comes from the Zulu word imamba. The black mamba in particular is very fast, and very deadly.

Mamba spiked in lookups on the day of Bryant’s tragic death, with users looking up the word 42,750% more than is typical; the next day that number had increased to 66,366%. Overall, mamba was looked up 934% more frequently in 2020 than it had been in 2019.

-

On July 23rd, Seattle’s brand-new National Hockey League franchise chose “Kraken” as its team name, hurling the word kraken into top lookup territory. Searches for the word increased 128,000% that day.

A kraken is a mythical Scandinavian sea monster; the word, which comes from Norwegian dialect, has been used in English since the middle of the 18th century. Krakens have featured in various contexts more familiar to English speakers than Scandinavian folklore, including various iterations of krakens in Marvel comics and a memorable monster in “Clash of the Titans.” In the 2010 remake of that movie, Zeus commands his underlings to “Release the Kraken” in a particularly dramatic scene. That phrase has gone on to enjoy a life of its own, with “Release the Kraken” being attached to memes as occasions warrant. Kraken spiked in lookups again in mid-November, when lawyer Sidney Powell said she would “release the Kraken,” which in this case meant to present evidence that votes for President Donald Trump had been deleted. No evidence has been put forth, and the Department of Homeland Security has described the 2020 presidential election as “the most secure in American history.”

-

As the reality of the global pandemic set in, policy responses received as much attention as medical analyses of this new disease. Accordingly, the biggest increase in lookups for one of the most important terms in this new circumstance, quarantine, was on March 20th, nine days after the greatest spike for pandemic.

Quarantine means “a state of enforced isolation designed to prevent the spread of disease.” It came into English through the intersection of French and Italian influences; the French word quarantaine (“about forty”) was borrowed in the late 1400s with a meaning of “a period of forty days”; it later blended with the Italian word quarantena, meaning “isolation of a ship to protect the port city from potential disease.” The Italian term was first used during the pandemic of bubonic plague in the 14th century.

Quarantine is also used as a verb in English, a use that dates back to the early 19th century.

As with pandemic, there was interest in this word before the stay-at-home orders became a reality in the U.S., with February’s reports of outbreaks on cruise ships in early February in the news triggering lookups. Quarantine was looked up 1,856% more frequently in 2020 than in 2019.

-

The word antebellum was looked up in significantly higher numbers for two distinct reasons in 2020. The first jump in lookups came in June, when an award-winning musical trio announced a name change: “Lady Antebellum” would now officially be called “Lady A.” The second increase came with the September release of a movie that uses the word as its title. These two events made for a year-over-year increase in lookups of 885%.

Antebellum comes from Latin ante bellum, meaning “before the war.” We define the English word in a two-part definition: the word can mean simply “existing before a war,” but it is especially used to specifically mean “existing before the American Civil War.” The enslavement of Black Americans that so painfully characterizes the antebellum period was centered in both instances of the word’s increase in lookups: the movie imagines the horrors of antebellum slavery imposed on modern Black Americans; the musical group’s name change means that its name no longer evokes a time when Black Americans were slaves.

-

Schadenfreude is a word-lover’s word, one that pops up in spelling bees and vocabulary tests all the time. This is partly because it’s hard to spell, and partly because it’s fun to say out loud, although its pronunciation isn’t necessarily easy to discern for an English speaker. In fact, this entry’s audio pronunciation is one of the most clicked-on in our online dictionary.

It’s pronounced /SHAH-dun-froy-duh/, by the way.

But this word is perhaps also popular among wordies because of its specific and slightly malicious meaning: “enjoyment obtained from the troubles of others.” It had a spike in lookups in March when news of the collegiate admissions scandal broke, but the biggest single spike this year took place on October 2nd, when it was announced that President Trump had contracted the novel coronavirus. An example of this use came in the form of a headline from USA Today:

President Donald Trump’s coronavirus infection draws international sympathy and a degree of schadenfreude

Such uses created a spike of 24,800% compared to last year’s lookups.

Following the announcement of President Trump’s loss to Joe Biden, the word again returned to a high spot in our list.

Schadenfreude belongs to a class of German borrowings that highlight that language’s penchant for referring to complex ideas in a single, though lengthy, compound word. It comes from Schaden, meaning “damage,” and Freude, meaning “joy.”

-

In this year when the public’s mind has so often been focused on COVID-19, the word asymptomatic is a reminder of one of the coronavirus’ most challenging characteristics—that people who are without symptoms can be contagious.

The word asymptomatic was looked up 1,688% more this year than it typically is. We define the word as “presenting no symptoms of disease.” It was formed in the middle of the 19th century to contrast with symptomatic, a word that predates it by more than a century. Both words can be traced back to Greek sympiptein, meaning “to happen.” The prefix a- means “not; without.”

-

When all was said and done in 2020, the word irregardless had earned a spot in the Words of the Year pantheon—mostly just by having the temerity to be a word. While some will deem the word’s presence in this list as further evidence of how truly odious the year was, we in the dictionary business know that the word qualified for inclusion here because people care about language, and that’s worth celebrating.

Lookups for irregardless increased dramatically in July, up 464%, when actress Jamie Lee Curtis asserted on Twitter that we had just entered the word. Ms. Curtis was wrong: we first entered irregardless in one of our dictionaries in 1934, and an entry for it has been at Merriam-Webster.com since the dawn of that website. (Wrong or not, Ms. Curtis, we still love you.) Other celebrities tweeted about the word as well, helping to boost irregardless into a level of lookup significance that we couldn’t ignore.

-

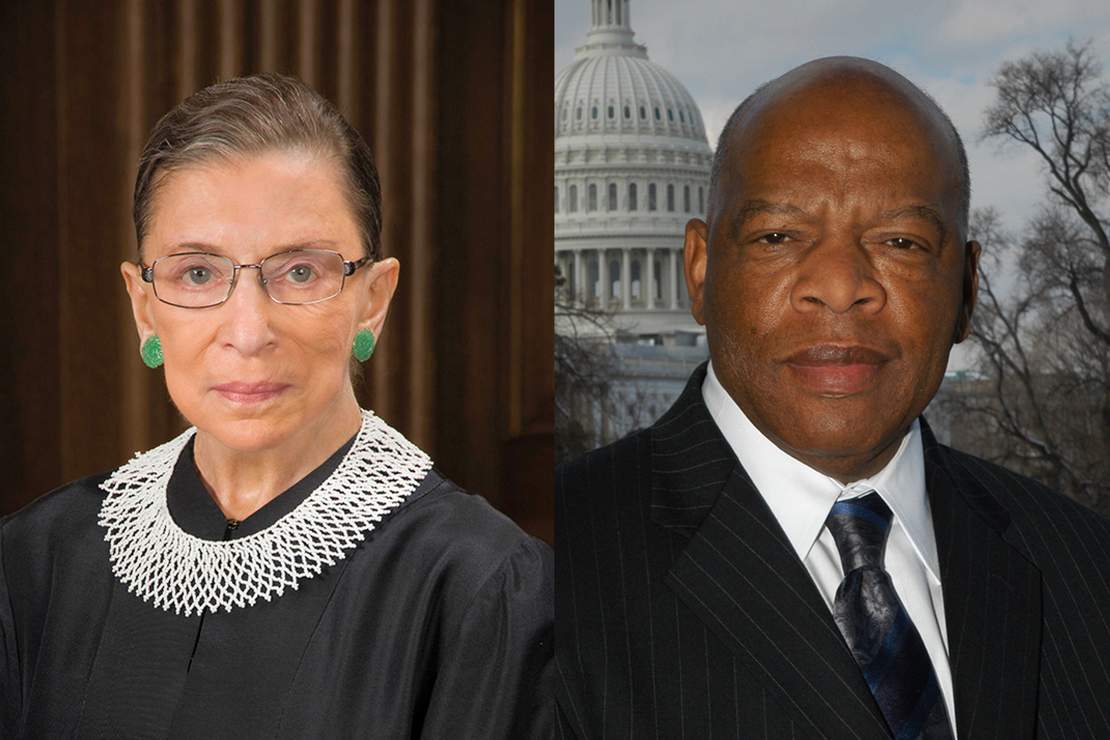

Photo: Steve Petteway, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States / United States House of Representatives | Public Domain

Among those lost in a year of many painful losses were two individuals whose life’s work persisted long after they’d earned a restful retirement. As writers sought to eulogize first Representative John Lewis in July, and then Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in September, they called upon the word icon to do so. The word saw significant increases in lookups in both instances, averaging 2,205% higher than last year.

A person who is identified as an icon is widely admired for having great influence or significance in a particular sphere, and frequently also representative of some ideal. Like many human icons, the word’s beginning was a modest one: in earliest use it referred simply to an image. Eventually, it referred specifically to an image of religious value, an icon being a sacred image, often one painted on a small wooden panel and used by Eastern Christians in their prayer and worship.

-

Presidents can propel a word into the common vernacular—or at least the public eye. Ronald Reagan’s verbal tic of beginning responses with “Well…” and George W. Bush’s malapropism misunderestimated qualify, and President-elect Joe Biden’s use of malarkey is on track to do the same.

Biden used malarkey several times during the vice-presidential debate with Paul Ryan in October 2012, sending many people to the dictionary to look the word up. He used it again during the 2016 Democratic National Convention, saying, of then-candidate Donald Trump:

He is trying to tell us he cares about the middle class. Give me a break. That is a bunch of malarkey.

The word’s biggest increase in lookups in 2020 was when Biden used it during the presidential debate on October 22nd, when it spiked 3,200% over last year.

It’s clear that this word is a favorite of Biden’s. In fact, our research shows that he is quoted using it going back to at least 1983, and it has since become part of his personal rhetorical style. The word seems to resonate with Biden’s public image: folksy, a bit old-fashioned, and Irish-American.

In fact, the word’s true origins are not clear. It resembles an Irish last name (sometimes spelled Mullarkey), but could also have come from Irish slang or even a similar-sounding Greek word. One thing is certain: malarkey was used first in the U.S., not Ireland. We trace its earliest use back to the 1920s.

The informal and even euphemistic nature of malarkey may account for some of the visits to the dictionary’s pages, which likely aim to answer the very basic question: “is that word in the dictionary?”

Subscribe to America’s largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Merriam-Webster unabridged

Подайте заявку и узнайте все подробности

Введенный вами номер телефона не соответствуют формату выбранного региона

Напишите мне в вацап

Отправить заявку >>

Нажимая на кнопку, вы принимаете данные условия

Back to Word of the Year 2022

The Committee’s Choice & People’s Choice for Word of the Year 2020

Posted on 7 December 2020

What is the Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year

Once a year, at Macquarie Dictionary HQ, we get together with a select group of people with a mind to decide on a single Word of the Year for the year that has passed. We look at all the new words and new definitions that have entered the Macquarie Dictionary in the past year.

Our editors create a longlist of 75 words (you can check them out here) split into different categories (some of which we have discussed in our blogs here).

Because COVID-19 has so deeply affected every aspect of life in 2020, it was a foregone conclusion that a word related to the pandemic would be the Word of the Year. So we’ve done things a little differently – Macquarie has selected two Words of the Year for 2020! One from the non-pandemic side of life, and one from the hefty vocabulary introduced by our collected dealings with COVID.

People’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year 2020: Karen

In 2020, Karen has proved to be a strong contender, winning the People’s Choice ballot and scoring an Honourable Mention from the Committee. Colloquial and contentious, it was used as a neat descriptor of this particular type of woman, its popularity being kicked along by viral social media videos. Interestingly, of the people named Karen who voted in the People’s Choice, half gave a nod to Karen themselves. – MACQUARIE DICTIONARY

People’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary COVID Word of the Year 2020: covidiot

Another colloquialism, embraced enthusiastically by Australians, especially during Victoria’s second wave, covidiot was a runaway winner in the People’s Choice vote. Like Karen, covidiot was given an Honourable Mention by the Committee, one member saying ‘we saw no end of covidiots on TV – and the occasional maskhole as well’.– MACQUARIE DICTIONARY

Committee’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year 2020: doomscrolling

Do your thumbs hurt from scrolling through the seemingly endless barrage of bad news in 2020? Ours do too, and that’s why doomscrolling is the 2020 Commitee’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year.

A very salient marker of 2020, with its barrage of troubling news, from the bushfires to the US elections and, of course, coronavirus. Doomscrolling is a neat construction, and gives a nod to our modern-day addiction to our digital devices. –THE COMMITTEE

Committee’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year Honorable Mentions

There were two Honourable Mentions this year, Karen and pyrocumulonimbus. Karen is a piece of slang you have likely heard that is used predominantly to refer to a middle-class white woman, often of generation X, who is regarded as having an entitled, condescending and often racist attitude.

The second word came to our editors’ attention during the Black Summer bushfires. A pyrocumulonimbus is a cumulonimbus cloud which forms above a source of intense heat, such as a bushfire, volcanic eruption, etc.

Honourable Mention: Karen

A contentious term, but a big one in 2020, from Bunnings stores to the footpaths of St Kilda. The lack of a male equivalent points to the sexist nature of the word — there are definitely plenty of entitled male versions about . . .–THE COMMITTEE

Honourable Mention: pyrocumulonimbus

Who could forget the news stories of last summer, and the images of these massive weather events caused by the fires? A lovely-sounding word for a horror that hit home for us all. –THE COMMITTEE

Committee’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary COVID Word of the Year 2020: rona

And for our second Word of the Year for 2020, we have selected rona, a shortening of coronavirus a.k.a. COVID-19.

In true Australian fashion, we started using this shortened version of coronavirus at the very start of the pandemic. It’s neat, it’s quintessentially 2020, and it’s a typical Australian formation. – THE COMMITTEE

Committee’s Choice Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year Honorable Mentions: Covid category

Given how tough it was to choose just one word from a shortlist of twenty, the Committee also nominated two COVID words for Honourable Mentions. These were covidiot and COVID normal.

A covidiot is a person who refuses to follow health advice aimed at halting the spread of COVID-19, while COVID normal refers to a way of living in which a community takes precautions against the transmission of COVID-19, prior to the availability of an effective vaccine, as a natural part of day-to-day life

Honourable Mention: covidiot

This appeared very early, but really took hold during Victoria’s second-wave lockdown, during which we saw no end of covidiots on TV – and the occasional maskhole as well. –THE COMMITTEE

Honourable Mention: COVID normal

After much reference to ‘the new normal’ in the first months of the coronavirus, COVID normal gave this term a twist to neatly refer to what will be our accepted way of life when community transmission has been halted, but before the wide availability of a vaccine. –THE COMMITTEE

Word of the Year Shortlist 2020

Please find all the shortlisted words below, or you can read the definitions for the Word of the Year shortlist here and the COVID Word of the Year shortlist here.

Quarantine was the only word to rank in the top five for both search spikes and overall views (more than 183,000 by early November), with the largest spike in searches (28,545) seen the week of 18-24 March, when many countries around the world went into lockdown as a result of COVID-19.

Noticing this spike in searches, our editors were keen to research how people were using the word quarantine, and were interested to find a new meaning emerging: a general period of time in which people are not allowed to leave their homes or travel freely, so that they do not catch or spread a disease.

Research shows the word is being used synonymously with lockdown, particularly in the United States, to refer to a situation in which people stay home to avoid catching the disease.

This new sense of quarantine has now been added to the Cambridge Dictionary, and marks a shift from the existing meanings, which relate to containing a person or animal suspected of being contagious.

The words that people search for reveal not just what is happening in the world, but what matters most to them in relation to those events.

Neither coronavirus nor COVID-19 appeared among the words that Cambridge Dictionary users searched for most this year. We believe this indicates that people have been fairly confident about what the virus is. Instead, users have been searching for words related to the social and economic impacts of the pandemic, as evidenced not just by quarantine but by the two runners-up on the shortlist for Word of the Year: lockdown, and pandemic itself.

This interest in quarantine and other related terms was reflected not only in our search statistics, but also in visits to this blog. The most highly viewed blog post this year was Quarantine, carriers and face masks: the language of the coronavirus, which had almost 80,000 views in the first six weeks after it was posted on February 26, and now ranks as the ninth most viewed post in the nearly ten years that the blog has been live. The post covers a range of related terms, such as infectious, contagious, carriers, super spreaders, and symptoms as well as phrases such as contract a virus, a spike in cases, contain the spread, and develop a vaccine.

Our editors regularly monitor a wide range of sources for the new words and meanings that are added monthly to the online dictionary. On the New Words blog, potential new additions are posted weekly for readers to cast their vote on whether they feel these words should be added. In a recent poll, 33 percent of respondents said quaranteam – combining quarantine and team, meaning a group of people who go into quarantine together – should be added to the dictionary. Other suggestions include the portmanteau words quaranteen, coronnial and lockstalgia.

Find out more about our Word of the Year 2020.

CNN

—

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has been unable to name its traditional word of the year for 2020, instead exploring how far and how quickly the language has developed this year.

“It quickly became apparent that 2020 is not a year that could neatly be accommodated in one single ‘word of the year,’” the OED said, with the language adapting “rapidly and repeatedly.”

The report, titled “Words of an Unprecedented Year,” uses an adjective that has itself seen a big spike in use during 2020.

“Though what was genuinely unprecedented this year was the hyper-speed at which the English-speaking world amassed a new collective vocabulary relating to the coronavirus, and how quickly it became, in many instances, a core part of the language,” the report reads.

It moves through the year, detailing the most important words in certain months, based on spikes in use, from “bushfire” in January, when Australia suffered its worst fire season on record, to “acquittal” in February, when US President Donald Trump’s impeachment trial ended.

From March onward, terms related to the coronavirus pandemic start to dominate, including “Covid-19,” a completely new word, first recorded on February 11; “lockdown,” “social distancing” and “reopening.”

In June, use of the phrase “Black Lives Matter” exploded, followed by “cancel culture” and “BIPOC,” an abbreviation of “Black, indigenous and other people of color.”

“Mail-in” and “Belarusian” were both flagged as words of the month for August, referring to mail-in voting for the US election and the controversial reelection of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, respectively.

“Moonshot,” the name the UK government gave to its mass coronavirus testing program, appears in September, while “net zero” and “superspreader” are highlighted in October.

Net zero refers to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s pledge that the country will be carbon neutral by 2060, and superspreader, a word that dates to the 1970s, according to the OED, saw a spike in use after a cluster of Covid-19 cases at the White House.

The OED named “climate emergency” as word of the year in 2019, and “toxic” in 2018.

Беспрецедентный и многословный:

21 слово 2020 года

Пока мы вспоминаем, что успели сделать за год, лингвисты выбирают самые частотные, яркие и «говорящие» слова. Экспертный совет конкурса «Слово года» назвал главным «обнуление». Филолог и журналист Марина Королёва — одна из экспертов — рассказала, как проходили «выборы», а мы собрали и визуализировали информацию обо всех словах 2020 года.

Знак большого ноля

«Слово года» — ежегодная акция. Её проводят в России и многих других странах. Например, в Германии, США, Великобритании, Польше, Японии, Австралии. В этом году «выборы» прошли четырнадцатый раз.

Российских «кандидатов» выдвигают участники групп «Слово года» и «Неологизм года» на Фейсбуке. Заметки о новых и интересных словах каждый год начинают появляться на этих страницах уже в январе. Самые частотные варианты попадают в списки для голосования. Их передают Экспертному совету из четырнадцати человек. Это известные писатели, филологи, лингвисты, журналисты, культурологи и философы. Каждый член комиссии выбирает по семь слов и присваивает им от одного до семи баллов. Чем выше оценка у «кандидата», тем он, по мнению эксперта, ближе к победе.

Словом 2020 года стало обнуление. Оно ассоциируется, в первую очередь, с поправками, которые по итогам всероссийского голосования внесли в конституцию летом, но, по мнению руководителя совета, филолога и культуролога Михаила Эпштейна, слово связано не только с политикой. Об этом он пишет на сайте проекта «Сноб»:

Пока мы вспоминаем, что успели сделать за год, лингвисты выбирают самые частотные, яркие и «говорящие» слова. Экспертный совет конкурса «Слово года» назвал главным «обнуление». Филолог и журналист Марина Королёва — одна из экспертов — рассказала, как проходили «выборы», а мы собрали и визуализировали информацию обо всех словах 2020 года.

Знак большого ноля

«Слово года» — ежегодная акция. Её проводят в России и многих других странах. Например, в Германии, США, Великобритании, Польше, Японии, Австралии. В этом году «выборы» прошли четырнадцатый раз.

Российских «кандидатов» выдвигают участники групп «Слово года» и «Неологизм года» на Фейсбуке. Заметки о новых и интересных словах каждый год начинают появляться на этих страницах уже в январе. Самые частотные варианты попадают в списки для голосования. Их передают Экспертному совету из четырнадцати человек. Это известные писатели, филологи, лингвисты, журналисты, культурологи и философы. Каждый член комиссии выбирает по семь слов и присваивает им от одного до семи баллов. Чем выше оценка у «кандидата», тем он, по мнению эксперта, ближе к победе.

Словом 2020 года стало обнуление. Оно ассоциируется, в первую очередь, с поправками, которые по итогам всероссийского голосования внесли в конституцию летом, но, по мнению руководителя совета, филолога и культуролога Михаила Эпштейна, слово связано не только с политикой. Об этом он пишет на сайте проекта «Сноб»:

«Обнулилась в буквальном смысле, то есть подошла к концу жизнь множества людей. Обнулились работы, бизнесы, профессии, отрасли, бюджеты. В значительной степени обнулилась общественная и культурная жизнь. Знаком большого НОЛЯ помечено главное в минувшем году — обнуляющее воздействие пандемии на цивилизацию. Поэтому обнуление, какой бы смысл в него ни вкладывали конкретные эксперты, мне представляется самой ёмкой характеристикой уходящего года»

«Обнулилась в буквальном смысле, то есть подошла к концу жизнь множества людей. Обнулились работы, бизнесы, профессии, отрасли, бюджеты. В значительной степени обнулилась общественная и культурная жизнь. Знаком большого НОЛЯ помечено главное в минувшем году — обнуляющее воздействие пандемии на цивилизацию. Поэтому обнуление, какой бы смысл в него ни вкладывали конкретные эксперты, мне представляется самой ёмкой характеристикой уходящего года»

Марина Королёва, кандидат филологических наук и член Экспертного совета конкурса «Слово года», говорит, что «политическая» лексика могла обойти «ковидную» по разным причинам:

«Слова и выражения года выбирают всё-таки люди, а не машины. У каждого из них есть свои политические взгляды, каждый живёт в своём информационном «пузыре». У меня, например, на первых местах во всех номинациях были слова, связанные с коронавирусом, и моё мнение не совпало с мнением большинства. Вообще всё, что относится к коронавирусу, выражается несколькими словами: выбрать одно действительно непросто. Кроме того, не исключено, что люди просто устали от темы ковида или хотели сделать результаты голосования неочевидными»

«Слова и выражения года выбирают всё-таки люди, а не машины. У каждого из них есть свои политические взгляды, каждый живёт в своём информационном «пузыре». У меня, например, на первых местах во всех номинациях были слова, связанные с коронавирусом, и моё мнение не совпало с мнением большинства. Вообще всё, что относится к коронавирусу, выражается несколькими словами: выбрать одно действительно непросто. Кроме того, не исключено, что люди просто устали от темы ковида или хотели сделать результаты голосования неочевидными»

Объективно определить слово года, по мнению Марины Королёвой, можно только полностью «машинным» способом: «Нужна программа, которая выявит самые частотные слова. На каком-то этапе их можно предложить экспертам, но тогда эксперимент уже не будет чистым».

«Результаты наших «выборов» субъективны, — говорит филолог, — но мы чётко можем объяснить, как проводим конкурс. На мой взгляд, это плюс: как другие институции определяют слово года, понятно не всегда».

Кроме слова года, Экспертный совет всегда выбирает победителей в трёх других номинациях. Выражением года стал патриотический лозунг «Жыве Беларусь!», который в 2020-м ассоциируется с протестами в Минске. Самым ярким явлением антиязыка — языка пропаганды, лжи и агрессии — объявили фразу Владимира Путина «Навальный мог сам себя отравить».

Ещё одна номинация конкурса — протологизм года, то есть слово, которое автор создаёт и предлагает ввести в язык, но которое в итоге не закрепляется в качестве неологизма. Эксперты выбирают лучшее из слов, «сконструированных» участниками группы «Неологизм года». В 2020-м «словом, которое стоит придумать» стал обнулидер — этимологический родственник победителя в главной номинации.

«Среди протологизмов было много ковидной лексики, — рассказывает Марина Королёва. — Мне, например, очень понравилось слово самоизолектор. Это о лекторе, который соблюдает режим самоизоляции. Ещё я отметила глагол расковидеться (увидеться после карантина, по аналогии с разговеться. — Прим. «Изборника»)».

Инфекция пробралась в верхнюю часть списков и в других номинациях. Звание слова года могли получить коронавирус, ковид и самоизоляция, а в первой тройке выражений закрепились масочный режим и социальное дистанцирование.

Не Фейсбуком единым

Обнуление словом 2020 года объявил не только Экспертный совет одноимённого конкурса, но и Государственный институт русского языка имени А. С. Пушкина. Правда, первое место в рейтинге оно разделило с самоизоляцией.

Редакции авторитетных англоязычных словарей тоже подвели лингвистические итоги года. По версии британского Collins Dictionary, слово года — lockdown (локдаун), а по версии редакции американского словаря Уэбстера (Merriam-Webster) — pandemic (пандемия, пандемический).

Объективно определить слово года, по мнению Марины Королёвой, можно только полностью «машинным» способом: «Нужна программа, которая выявит самые частотные слова. На каком-то этапе их можно предложить экспертам, но тогда эксперимент уже не будет чистым».

«Результаты наших «выборов» субъективны, — говорит филолог, — но мы чётко можем объяснить, как проводим конкурс. На мой взгляд, это плюс: как другие институции определяют слово года, понятно не всегда».

Кроме слова года, Экспертный совет всегда выбирает победителей в трёх других номинациях. Выражением года стал патриотический лозунг «Жыве Беларусь!», который в 2020-м ассоциируется с протестами в Минске. Самым ярким явлением антиязыка — языка пропаганды, лжи и агрессии — объявили фразу Владимира Путина «Навальный мог сам себя отравить».

Ещё одна номинация конкурса — протологизм года, то есть слово, которое автор создаёт и предлагает ввести в язык, но которое в итоге не закрепляется в качестве неологизма. Эксперты выбирают лучшее из слов, «сконструированных» участниками группы «Неологизм года». В 2020-м «словом, которое стоит придумать» стал обнулидер — этимологический родственник победителя в главной номинации.

«Среди протологизмов было много ковидной лексики, — рассказывает Марина Королёва. — Мне, например, очень понравилось слово самоизолектор. Это о лекторе, который соблюдает режим самоизоляции. Ещё я отметила глагол расковидеться (увидеться после карантина, по аналогии с разговеться. — Прим. «Изборника»)».

Инфекция пробралась в верхнюю часть списков и в других номинациях. Звание слова года могли получить коронавирус, ковид и самоизоляция, а в первой тройке выражений закрепились масочный режим и социальное дистанцирование.

Не Фейсбуком единым

Обнуление словом 2020 года объявил не только Экспертный совет одноимённого конкурса, но и Государственный институт русского языка имени А. С. Пушкина. Правда, первое место в рейтинге оно разделило с самоизоляцией.

Редакции авторитетных англоязычных словарей тоже подвели лингвистические итоги года. По версии британского Collins Dictionary, слово года — lockdown (локдаун), а по версии редакции американского словаря Уэбстера (Merriam-Webster) — pandemic (пандемия, пандемический).

Оксфордский словарь выбрал не одно слово года, а шестнадцать. Их распределили по месяцам в зависимости от частоты использования.

Из-за природных пожаров в Австралии, которые полыхали с сентября 2019 по март 2020 года, bushfire (лесной пожар) стало одним из слов января. Второй символ месяца — impeachment (импичмент). Это слово напоминает об отставке президента США Дональда Трампа, которая, правда, не состоялась. Американский сенат прекратил процедуру импичмента, а февраль отреагировал на это словом аcquittal (оправдание).

Март стал месяцем коронавируса. А может быть, тогда началась целая эра. В списке слов, который Оксфордский словарь приводит в конце доклада «2020. Слова беспрецедентного года», есть аббревиатура BC — before Covid/before coronavirus (до ковида/до коронавируса). Практически до Рождества Христова.

Кстати, о ковиде. Классификационное название нового коронавируса — SARS-CoV-2 — перестали писать довольно быстро. Уже в апреле популярной стала аббревиатура COVID-19, которая позже превратилась в «цельное» слово в английском, русском и многих других языках. Вместе с этим сокращением символами месяца для английского языка стали lockdown (локдаун) и Social Distancing (социальное дистанцирование). В России в это время были карантин — локдаун зазвучал только осенью — и дискусионная социальная дистанция.

В мае коронавирус немного ослабил хватку в России и Европе. Именно поэтому главным словом месяца Оксфорд выбрал reopening (открытие, возобновление).

Летом английский язык стал чуть свободнее от ковида. Громче в нём зазвучали резонансные события общественной и политической жизни. Слово июня — Black Lives Matter. Так называется американское протестное движение в защиту прав темнокожих.

Cancel culture (культура отмены) стало одним из главных слов июля. Это публичная критика или бойкот, который объявляют известным людям и компаниям за оскорбительные или противоречащие моральным нормам слова и поступки. Не менее значима аббревиатура BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color). Ею обозначают темнокожих людей, коренных жителей и тех, кто не относится к белой расе.

Завершилось лето выборами президента США по почте и протестами в Белоруссии. Слова августа — mail-in (по почте) и Belarusian (белорусский).

Осенью языки мира, в том числе английский, накрыла вторая волна «ковидной» лексики. Оксфордское слово сентября — Moonshot. Так называют прорывные, «амбициозные и инновационные» проекты, но если это слово используют в качестве имени собственного, речь идёт о программе британского правительства. По её итогам в стране планируют увеличить количество тестов на коронавирус с 200 тысяч до 10 миллионов в день.

В октябре одним из главных слов стало «пандемическое» superspreader (cуперраспространитель). Оно обозначает инфицированный организм, который особенно заразен для других. Например, человека с большим количеством социальных контактов во время эпидемии коронавируса.

Второе слово второго осеннего месяца связано с экологией. Net zero — цель регулировать выброс парниковых газов и разрабатывать для этого новые методы. Слово стало популярным, когда Китай пообещал к 2060 году сделать так, чтобы выброс углекислого газа в атмосферу полностью прекратился.

Оксфордский словарь выбрал не одно слово года, а шестнадцать. Их распределили по месяцам в зависимости от частоты использования.

Из-за природных пожаров в Австралии, которые полыхали с сентября 2019 по март 2020 года, bushfire (лесной пожар) стало одним из слов января. Второй символ месяца — impeachment (импичмент). Это слово напоминает об отставке президента США Дональда Трампа, которая, правда, не состоялась. Американский сенат прекратил процедуру импичмента, а февраль отреагировал на это словом аcquittal (оправдание).

Март стал месяцем коронавируса. А может быть, тогда началась целая эра. В списке слов, который Оксфордский словарь приводит в конце доклада «2020. Слова беспрецедентного года», есть аббревиатура BC — before Covid/before coronavirus (до ковида/до коронавируса). Практически до Рождества Христова.

Кстати, о ковиде. Классификационное название нового коронавируса — SARS-CoV-2 — перестали писать довольно быстро. Уже в апреле популярной стала аббревиатура COVID-19, которая позже превратилась в «цельное» слово в английском, русском и многих других языках. Вместе с этим сокращением символами месяца для английского языка стали lockdown (локдаун) и Social Distancing (социальное дистанцирование). В России в это время были карантин — локдаун зазвучал только осенью — и дискусионная социальная дистанция.

В мае коронавирус немного ослабил хватку в России и Европе. Именно поэтому главным словом месяца Оксфорд выбрал reopening (открытие, возобновление).

Летом английский язык стал чуть свободнее от ковида. Громче в нём зазвучали резонансные события общественной и политической жизни. Слово июня — Black Lives Matter. Так называется американское протестное движение в защиту прав темнокожих.

Cancel culture (культура отмены) стало одним из главных слов июля. Это публичная критика или бойкот, который объявляют известным людям и компаниям за оскорбительные или противоречащие моральным нормам слова и поступки. Не менее значима аббревиатура BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color). Ею обозначают темнокожих людей, коренных жителей и тех, кто не относится к белой расе.

Завершилось лето выборами президента США по почте и протестами в Белоруссии. Слова августа — mail-in (по почте) и Belarusian (белорусский).

Осенью языки мира, в том числе английский, накрыла вторая волна «ковидной» лексики. Оксфордское слово сентября — Moonshot. Так называют прорывные, «амбициозные и инновационные» проекты, но если это слово используют в качестве имени собственного, речь идёт о программе британского правительства. По её итогам в стране планируют увеличить количество тестов на коронавирус с 200 тысяч до 10 миллионов в день.

В октябре одним из главных слов стало «пандемическое» superspreader (cуперраспространитель). Оно обозначает инфицированный организм, который особенно заразен для других. Например, человека с большим количеством социальных контактов во время эпидемии коронавируса.

Второе слово второго осеннего месяца связано с экологией. Net zero — цель регулировать выброс парниковых газов и разрабатывать для этого новые методы. Слово стало популярным, когда Китай пообещал к 2060 году сделать так, чтобы выброс углекислого газа в атмосферу полностью прекратился.

Слова ноября и декабря редакция Оксфордского словаря не выбрала. Зато приложила к докладу список «кандидатов», которые не получили главный титул, но тоже стали знаковыми для 2020 года.

Среди них plandemic (пландемия) — спланированная пандемия, и infodemic (инфодемия) — распространение разнообразной, часто необоснованной информации о кризисе, споре или событии. Такие сведения быстро и бесконтрольно распространяются и усиливают беспокойство в обществе. Здесь же hygiene theatre (театр гигиены). Это «потёмкинские деревни» эпохи ковида — меры, которые создают иллюзию дезинфекции, но не снижают риск заражения.

Похожий список составили лингвисты Уральского федерального университета вместе с коллегами из Финляндии, Швеции и Испании. Слова, которые в него вошли, описывают типичные для эпидемии коронавируса ситуации и типы отношения к ним. Например, ковидло — повидло, запаха которого не чувствует заболевший, а коронапофигист — тот, кто не боится заработать такой симптом.

«Яндекс» на основе поисковых запросов определил слова десятилетия. Ими стали карантин, пропуск и конституция. Употребление этих имён нарицательных в разные годы учащалось более чем в три раза.

Если коронавирус кто-то умудряется игнорировать, то не заметить, как он изменил язык за 2020 год, трудно. Появились абсолютно новые понятия, стали общеупотребительными профессиональные медицинские термины, актуализировались привычные, но не слишком частотные слова наподобие масок и перчаток. Что будет в новом году, неизвестно. Но никто не запретит попросить деда Мороза, чтобы он обнулил пандемию и сделал историей «ковидную» лексику.

Слова ноября и декабря редакция Оксфордского словаря не выбрала. Зато приложила к докладу список «кандидатов», которые не получили главный титул, но тоже стали знаковыми для 2020 года.

Среди них plandemic (пландемия) — спланированная пандемия, и infodemic (инфодемия) — распространение разнообразной, часто необоснованной информации о кризисе, споре или событии. Такие сведения быстро и бесконтрольно распространяются и усиливают беспокойство в обществе. Здесь же hygiene theatre (театр гигиены). Это «потёмкинские деревни» эпохи ковида — меры, которые создают иллюзию дезинфекции, но не снижают риск заражения.

Похожий список составили лингвисты Уральского федерального университета вместе с коллегами из Финляндии, Швеции и Испании. Слова, которые в него вошли, описывают типичные для эпидемии коронавируса ситуации и типы отношения к ним. Например, ковидло — повидло, запаха которого не чувствует заболевший, а коронапофигист — тот, кто не боится заработать такой симптом.

«Яндекс» на основе поисковых запросов определил слова десятилетия. Ими стали карантин, пропуск и конституция. Употребление этих имён нарицательных в разные годы учащалось более чем в три раза.

Если коронавирус кто-то умудряется игнорировать, то не заметить, как он изменил язык за 2020 год, трудно. Появились абсолютно новые понятия, стали общеупотребительными профессиональные медицинские термины, актуализировались привычные, но не слишком частотные слова наподобие масок и перчаток. Что будет в новом году, неизвестно. Но никто не запретит попросить деда Мороза, чтобы он обнулил пандемию и сделал историей «ковидную» лексику.