Table of Contents

- Is Spanish and Italian language the same?

- What language is a mix of Spanish and Italian?

- Can a Spanish person understand Italian?

- Which language came first, Spanish or Italian?

- Is Italian similar to Spanish?

- What are the similarities between Italian and Spanish?

- How similar are Spanish and Italian languages?

Italian

Italian is an official language in Italy, Switzerland (Ticino and the Grisons), San Marino, and Vatican City.

Is Spanish and Italian language the same?

Spanish and Italian are mutually intelligible to various degrees. They both come from “Vulgar Latin,” that’s why they have so much in common. Italian and Spanish share 82% lexical similarity. In Spanish, the word “jardín” and, in Italian word “Giardino” means “place.”

What language is a mix of Spanish and Italian?

Cocoliche

Cocoliche is an Italian–Spanish mixed language or pidgin that was spoken by Italian immigrants in Argentina (especially in Greater Buenos Aires) and Uruguay between 1870 and 1970. In the last decades of the 20th century, it was replaced with or evolved into Lunfardo, which in turn has influenced Rioplatense Spanish.

Can a Spanish person understand Italian?

Italian is a great complement to Spanish, French and Latin. Often times, even without any previous formal training, Spanish speakers are able to understand a lot of Italian (and Portuguese, for that matter), mostly in their written, but often also in their spoken forms.

Which language came first, Spanish or Italian?

Spanish came first. The Spanish language is really Vulgate Latin , spoken by the lower classes in Rome as far back as the days of Cicero and Julius Caesar.

Is Italian similar to Spanish?

Italian is very similar to Spanish in some ways. But, after all is said and done, it is still a foreign language. They have different spelling rules, phonemes, and vocabulary. On a positive note, they have nearly identical grammar rules, as far as nouns having gender and agreement with adjectives, but the word endings are different (more complex).

What are the similarities between Italian and Spanish?

Spanish and Italian share a very similar phonological system and do not differ very much in grammar. At present, the lexical similarity with Italian is estimated at 82%. As a result, Spanish and Italian are mutually intelligible to various degrees.

How similar are Spanish and Italian languages?

The lexical similarity between Spanish and Italian is over 80%. That means that 4/5 of the two languages’ words are similar but does not mean that they are necessarily mutually intelligible to native speakers due to additional differences in pronunciation and syntax.

Why learn the 1000 most common Italian words?

Are you trying to learn Italian?

The best way to get started is to memorize the 1000 most common Italian words.

Many language experts will point out that focusing on the basic vocabulary in any language is the best investment for your time.

You will rarely use complicated or trivial words in your daily life when speaking with friends, colleagues, or family members.

So why not focus on getting familiar with only the words you know you’ll use?

With the basic words, you can make simple phrases for your first Italian conversation or your next trip to Italy!

With basic Italian words, you’ll start forming sentences in Italian and ultimately have flowing Italian conversations.

Learn how to form sentences in Italian.

How much can you say with 1,000 words?

How much can you understand with the top 1000 most common Italian words?

A study revealed how much you can understand with 1000, 2000, or 3000 words.

Studying the first 1000 most commonly used Italian words in the language will familiarize you with:

- 76.0% of all vocabulary in non-fiction literature

- 79.6% of all vocabulary in fiction literature

- 87.8% of vocabulary in oral speech

Studying the 2000 most commonly Italian used words will familiarize you with:

- 84% of vocabulary in non-fiction

- 86.1% of vocabulary in fictional literature

- 92.7% of vocabulary in oral speech

And studying the 3000 most commonly Italian used words will familiarize you with:

- 88.2% of vocabulary in non-fiction

- 89.6% of vocabulary in fiction

- 94.0% of vocabulary in oral speech

If you’re an ambitious language learner, you can certainly learn 3,000 of the most common words for 94% comprehension.

However, for most of us, we want to optimize for what’s the best return for our time.

Based on this study, it seems that 1,000 most common words are the best bet.

The reason is, you have to memorize 3x (or 2,000 more words) to be able to understand only 6.2% of vocabulary in oral speech.

It doesn’t seem very exciting considering how valuable your time is.

In fact, we’ve seen that most Italian learners can get to a comfortable conversation speaking level with less than 1,000 Italian words.

If you listen to Italian music to learn this beautiful language and improve your Italian pronunciation, choose the right Italian songs because some lyrics aren’t exactly what you’d say in real life.

The same applies to Italian idioms, Italian sayings, verbal phrases, Italian proverbs, Italian quotes, or even Italian swear words.

Frequent Italian words: facts and figures

The Italian language is estimated to be made out of a total of 450000 words with the largest Italian dictionary having over 270000 words.

This can seem a really big and frightening number to someone wanting to start learning Italian, but here’s the good news: you only need to know roughly 5% of the total words to be fluent in Italian.

This means that focusing your efforts on learning the most frequent Italian words you will be fluent in Italian in no time.

What’s even more encouraging is that knowing as little as 100 words helps you understand half of the words in an article or book written in Italian.

Learn the most common 1000 words and you get to a 75% understanding of texts in Italian.

Also, each new word you learn helps you guess the Italian meaning of up to 135 words you have never seen before.

This means that knowing only 1000 words helps you guess up to 135000 Italian words.

Doesn’t seem that frightening now, right?

The problem with lists of common Italian words

Now that you know what you can do with 1000 words in the Italian language, the question is: how to learn these basic Italian words?

Many people make flashcards with word lists.

These word lists are usually generated from a huge multi-billion sample of language called a corpus which ensures all topics and text types are covered and the word list reflects how words are used by real users.

On the internet, you can find quite a few lists of the most 1000 common Italian words like this, this, and this.

Some of these lists of 100, 500, 1000, and 2000 basic Italian words are available for free in PDF or CSV format.

However, many are not very useful because they include “function words” like “for, but, when”.

For example, here are the top 50 words from one of those lists:

non che di e la il un a è per in una sono mi ho si lo ma ti ha le cosa con i no da se come io ci questo qui hai bene sei tu del me mio al solo sì tutto te più della era c lei gli

Does that help? No.

Even though these words are frequent and useful, they don’t make any sense per se and need a context to be practiced and mastered.

Another reason for not using them is how different forms of the same word are counted.

Some wordlists are not lemmatized.

This means that different forms of the same words are not counted together, i.e. goes, went, gone, going and go. This is generally more practical.

Ironically, one of the largest lists of Italian words is made from movie subtitles, which are often a translation of foreign movie scripts. Often, they’re not even professionally translated.

So, they don’t reflect the way an Italian speaker really talk.

In other words, the top 1000 Italian words are not the same for everyone.

The 1000 most used Italian words depend on who uses them, and on their purpose.

Do you want to chat with friends with natural Italian phrases? Travel? Or watch the news in Italian? These situations require a different vocabulary.

The best list of common Italian words

This is what you were looking for: the best list of common Italian words.

The smartest word list for the Italian language I’ve found so far is this.

It’s divided into:

- Italian nouns

- Italian adjectives

- Italian verbs

- Italian function words like and adverbs, prepositions, articles

Judging from the words, I guess they were taken from newspaper articles.

How to Learn Languages Fast

The picture below is a preview. As you can see, the words are arranged according to parts of speech.

Feel free to download it and edit it as you wish.

However, this list lacks a translation.

For my translation, keep reading!

Top 1000 common Italian words with English translation

The list of common Italian words I recommend doesn’t come with an English translation, so I translated the words for you.

Open the spreadsheet below to see the list of the top 1000 most frequent Italian words with English translation:

- Italian nouns make the longest list

- Then come Italian adjectives with translation

- Italian verbs with English translation in the infinitive form

- Other Italian words include adverbs, prepositions, and adjectives

You may also download the file to edit it as you wish.

To download it in a printable PDF format, just tell me where I should send it.

You’ll receive it immediately!

If you create a free account, you’ll also get other freebies for members. 100% free!

Just tell me where I should send it.

What are the most common words used in Italian?

Let’s start with some of the most common Italian words used in this popular language:

cosa

thing

giorno

day

anno

year

uomo

man

donna

woman

volta (as in “many times”)

time

casa

home

vita

life

tempo

time and weather

mano

hand

ora

now

paese

country, town

momento

moment

parola

word

famiglia

family

padre

father

madre

mother

figlio, figlia

son, daughter

amico

friend

lavoro

work

strada

street

nome

name

acqua

water

gente

people

persona

person

amore

love

mare

sea

What are the 100 most common words in Italian?

Even from a list of 1000 words, it still makes sense to start memorizing the 100 most common Italian words.

That’s your foundation to start forming an Italian phrase and ultimately have flowing conversations.

Indeed, you will rarely use complicated words in your daily conversations with friends, colleagues, or family members.

You find the 100 most common Italian words on the top of the list.

Once you’re done with them, you can move on to the other 900 words.

While apps like Quizlet and Anki are popular choices, I still recommend learning these words by putting them in context, for example in conversations with native speakers.

Learn more about Italian words.

What is the most popular Italian word?

You only need to look at the top of this list of the 1000 most used Italian words.

According to the list above, the most popular Italian word is a noun: cosa.

The word cosa in Italian gets so many colours and flavours according to the context.

Let’s see a few examples:

E’ la cosa piu’ bella che abbia mai visto.

It’s the most beautiful thing I have ever seen.

In this sentence, cosa doesn’t get any specific meaning besides the generic ”thing” we’re referring to.

Cosa mangiamo stasera?

What do we eat tonight?

In this sentence cosa is actually used to refer to something which, in this specific context, can be replaced with “food”.

We give for granted that we’re talking of food because of the type of question we do.

This would already be enough to make it to the top 1000.

Ti ricordi quella cosa che avevi visto tempo fa? L’ho vista anch’io ora!

Do you remember that thing you saw a while ago? I’ve just seen it now!

Again, the use of cosa, in this context, is referred to as a generic “thing” that could be potentially anything (A star? A spoon? A mouse? A spaceship? A waterfall?).

In this 3rd example, is that we use cosa in the same way you’d say “thingy” when you don’t remember the actual name of an object.

“Cosa” is a noun, thus you will need to remember, in this specific 3rd scenario, to also decline it according to what are you referring to/pointing at.

If you’re referring to a piatto (male noun meaning plate, dish) then you should say coso if you’re referring to it.

If you’re referring to some specific breed of conigli (means “rabbits”) then you will need to use the plural form of the noun which would be cosi (sounds a little bit rude).

With so many uses, it’s no wonder that it ranks #1 among the top 1000 most common Italian words in the Italian language.

Learn more about other meanings of the word cosa in Italian.

The most popular Italian word

We just told you the most popular word is cosa. However, deciding which is the most popular Italian word is not so simple.

Here’s another very common Italian word: ciao.

Ciao means hello and is pronounced as “chaw” since it’s a word Italians use every day.

It is mainly used in informal contexts. You can say ciao to friends and family members.

Ciao comes from the Venetian dialect (spoken in the Northeast of Italy), more specifically from the phrase s-ciào vostro, literally meaning “I am your slave”.

In the 17th century, this expression was used by servants when addressing their employers.

Often, s-ciào vostro was shortened to simply s-ciào and then to ciào.

With time, this word lost all its servile connotations and started to be used as an informal greeting (instead of Buongiorno, Buona Sera or Buona Notte).

Read more about the most popular Italian word.

The verb mangiare in Italian

This is probably the most important Italian verb you need to know if you’re planning to go to Italy!

It is well known all around the world that the boot-shaped peninsula has a huge eating culture.

Mangiare is a regular verb of the first conjugation and follows the typical –are pattern:

Io mangio= I eat

Tu mangi= you eat

Lui/Lei mangia= He/she eats

Noi mangiamo= we eat

Voi mangiate= you (plural) eat

Loro mangiano= they eat

Here’s a list of all the Italian meals you will find yourself invited to by your Italian friends:

colazione

breakfast

spuntino

light meal, nibble

pranzo

lunch

merenda

snack

aperitivo

aperitif

cena

dinner

spuntino di mezzanotte

midnight snack

Just so you know, it is incorrect to use mangiare followed by the meals we just described above, so we DO NOT SAY: mangiare colazione, pranzo, etc.

Instead, for colazione, spuntino, merenda, and aperitivo, we use the word fare (to do):

fare colazione

to have breakfast

fare uno spuntino

to have a nibble

fare merenda

to have a snack

fare l’aperitivo

to have an aperitif

To talk about lunch (pranzo) and dinner (cena), we actually use these verbs:

pranzare

to have lunch

cenare

to have dinner

Learn more about the verb mangiare and other Italian food phrases.

Are flashcards useful to learn common Italian words?

Now that we’ve shown you the benefits of focusing on the common words, let’s go over the methods to memorize them.

Casual learners love making flashcards, either on paper, on websites, or apps like Anki, Memrise, and Quizlet.

Anki is a digital flashcard creator that’s fairly popular in the language learning community.

You can use it to create your flashcards and its function goes beyond language learning.

The user interface is not the most modern, but it gets the job done.

Plus, you can use your phone, desktop, or tablet to learn basic Italian words.

Memrise has a more friendly user interface for creating and reading digital flashcards.

Our favorite part about Memrise is the ability to leverage the other digital flashcards that other community members have created.

For learning Italian, you’ll find several flashcard collections you can choose from.

Here’s an example of how to go through flashcards with Quizlet:

Does that help? Maybe, but it has some serious limits.

The problem with flashcards of common words

Now that you’re about to rush to download an app to memorize the top 1000 Italian words, I’ll spoil the fun.

This point is going to upset a lot of people.

Even though flashcard apps are the hottest thing in language learning right now, I’ll tell you to stop using them.

Stop using flashcards. Stop learning vocabulary from list of terms, or decks, or programs. Stop.

It doesn’t work, it’s a waste of time, and it’s creating bad patterns in your brain.

Even if your goal is to memorize these 1000 words, it won’t help you.

It could be Italian numbers, common Italian phrases, anything.

Learning anything (words, phrases, ideas, whatever) against its translation is creating extra steps in your brain.

It’s making you slow. It makes you think slowly, hear slowly, speak slowly.

I have a feeling that many of you reading this have experienced this frustration. I have experienced it, and it’s horrible.

There are few things as frustrating as knowing that you know what something means, but not being able to understand it when you see or hear it.

But the problem is that learning incorrectly is creating a maze that your brain has to run through as it processes every word.

You don’t do that to yourself in English (or whatever your native language), so why are you doing that with a foreign language?

Even if you take nootropics for studying languages to boost brain power, you can still get better results with other methods.

Put words in context

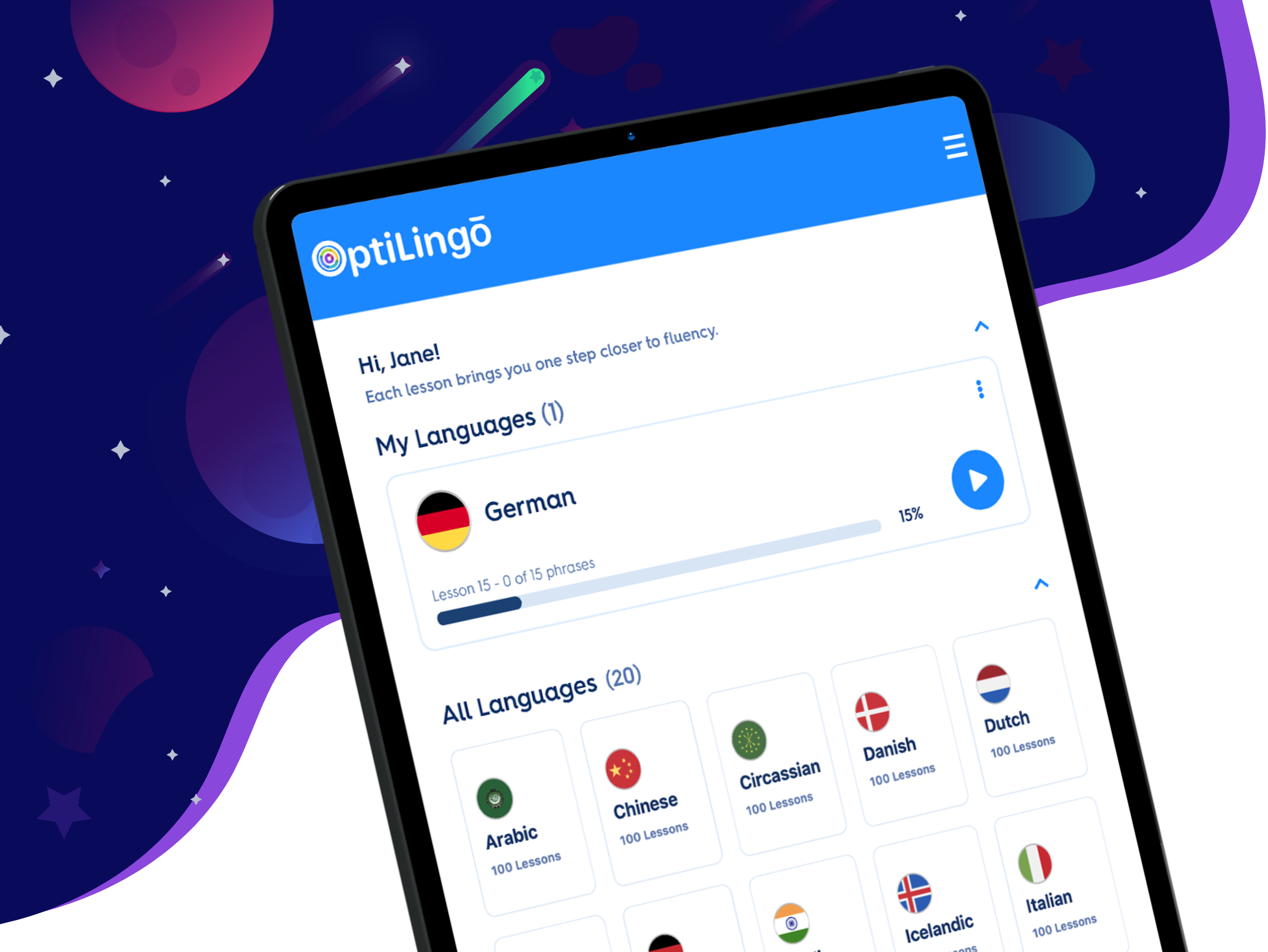

Apps such as Anki, Memrise, and Quizlet focus on traditional single-word flashcard study.

For example, a student of Italian may have a set of flashcards for studying the days of the week, with the basic Italian word on one side and the English translation on the other side.

In contrast, well-designed language courses focus on studying vocabulary in context by prompting the user to fill in the missing word in a sentence or repeating whole sentences.

With context-based flashcards, you’ll learn the meaning of the word, the appropriate situations to use the word, and you’ll also have the chance to learn related vocabulary at the same time.

When presented with vocabulary in rich contexts provided by authentic texts instead of in isolated vocabulary drills, students become more actively engaged in using words, analyzing word meanings, and creating relationships between words.

That’s also the case of the top 1000 Italian words.

This helps develop skills and strategies that will allow them to more easily determine the meaning of unfamiliar words.

A growing number of people have realized that studying in context provides a faster, more enjoyable, and more effective method for studying a large amount of vocabulary.

If you’re currently using a single-word study app and are looking for a better way to learn, here’s the best learning resource for the Italian language.

How to put words in context

One of the great things about learning a foreign language is that you can be creative. You need creativity and motivation to develop your language skills.

This is why, when it comes to vocabulary, one of the best tools you have to memorize new words and grasp their meanings is your own brain.

You could start with the easiest words.

Choose five to ten words that you like and invent a story, a tongue twister, a song, or a poem.

Something that makes sense or that makes you laugh.

You can repeat it and show it to your friends.

Your brain will remember those words in context and that’s your aim.

You could then move onto the next level and choose five to ten words that you find hard to remember.

If what you find difficult is the correct pronunciation, you could invent a tongue twister for each word and repeat it.

You could then invent Italian stories with those words.

These are just ideas.

You can find your own way to be creative.

The important thing is that you use the vocabulary in context.

Group words into sentences, not categories

These words will form the foundation of your Italian vocabulary.

They’re some of the most frequent words you will encounter, and they’re all easy to learn.

Because these words are grouped together into sentences, they will be much easier to memorize when compared with the typical word lists that you find in language textbooks and classrooms, where you learn colors one day, types of vegetables the next day, members of the family the following day, etc.

Learning entire categories of words is a waste of time because you don’t need all those words and many compete with each other for your memory. After all, they’re similar.

Learn more about Italian vocabulary.

Common Italian phrases

How to use these words in real phrases?

Check out this list of common Italian phrases sorted by context:

- Travel information

- Restaurants

- Hotels

- Making plans

- Attractions

- Food & drink

- Polite expressions

- Culture

Every phrase comes with its English translation.

If you want to practice those words and phrases and not just read them, I recommend audio lessons based on spaced repetition.

The best way to put words in practice: Ripeti con me!

You don’t have to give up on learning the top 1000 Italian words. You only need a good method!

The best way to acquire words and phrases naturally without relying on translation is with a well-designed set of sentences from conversations in the right order.

A focus on audio over text also helps bypass reading habits based on your native language.

This also makes it possible to learn Italian in the car.

The Italian audio course “Ripeti con me!” covers the 1000 most common Italian words in a set of sentences grouped by grammar patterns.

Those patterns are acquired almost unconsciously, while the very act of speaking bypassing translation will get you to think in Italian.

What’s more, since these are audio lessons, you’ll learn the new words with pronunciation.

This course provides plenty of comprehensible input balanced by variety and relevance, in small daily doses (spaced repetition).

Learn more about Ripeti Con Me.verbal phrases

This article is for everyone in love with the Italian language. Whether you are just thinking of learning italiano or are already proficient in it, it doesn’t matter. Here you will find a selection of materials and tips on how to learn Italian. Brew a delicious coffee, pause The Young Pope, open your favorite notebook, and andiamo!

Features of the Italian language

- Dialects or individual languages? Italy historically developed as a country of city-states. As a result, each of them has a local dialect. A single language standard was introduced only in 1861, after the unification of the country. The dialects of lingua italiana are still so diverse that not all Italians understand each other (especially if one is from the South and the other from the North).

| Phrase | Official Italian | Venetian languageused in the North-East of the country (around Venice) | Venetian dialect |

|---|---|---|---|

| We arrive | Stiamo arrivando | Sémo drio rivàr | Stémo rivando |

- Omnipresent articles. Not as bad as German, Italian still tries to knock you out of your shoes with its 8 articlesor 15, if you count their variants and short versions — take a gander.

| Genus | Single Indefinite | Plural Indefinite | Single Definite | Plural Definite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Un (Unoif the word begins with z, or s + consonant) | Dei (Degliif the word begins with z, or s + consonant) | Il (loif the word begins with z, or s) / (l ‘ if the word begins with a vowel) | I (gliif the word begins with a vowel, z, or s + consonant) |

| Feminine | Una (Un’ if the word begins with a vowel) | Delle | La (l ‘ if the word begins with a vowel) | Le |

- Language of art. Music students should be familiar with words like crescendo, staccato, or forte. Many terms of art and music originated in Italian culture during the Renaissance. By the way, modern italiano originated in the Tuscan dialect group. This is the high style that Petrarch and Dante used and popularized. So Italian is truly a literary language.

- It is read like it is written. A big advantage of Italian is that it is “phonetic» — the pronunciation of words coincides with their spelling. This is no French with its four-letter-one-sound combinations. The pronunciation itself is not easy for everyone, but more on that later.

- Vowel endings. Many words in Italian end with vowels. This gives it a special melody. Italians also love double consonants. There are words with three such pairs at once. For example: appallottolareto form into a ball or disseppellireto unearth.

- The subject is often omitted in colloquial Italian. It is already clear who or what is performing the action from the agreement of the verb. Therefore, the subject is not pronounced.

- Active suffixes. In this way, Italian is reminiscent of Russian. Both use suffixes to give the word different shades of meaning. For example, ragazzo — a guy; ragazzino, ragazzetto — a small guy; ragazzone — a big guy.

How to learn Italian on your own?

Learning Italian on your own is plausible. The only question is how much time, effort, and money you are willing to spend. Here are some general tips for learning lingua italiana:

- Study your “own” resources. With studying languages, everything is individual. You can find dozens of tutorials that have worked for others but somehow don’t for you. Look for something you find interesting personally. It’s not just about specific textbooks, but about methods in general. For some, it is easier to perceive information with their eyes, for some to listen, and others are advised to touch the objects in order to better memorize new words. Ideally, all of these techniques should be used. This makes the learning process faster.

- Always find new motivation. Learning Italian is easier when you need it: for college admission, work, or marriage. In this case, you do not need to look for motivation — it is always with you. But more often italiano is learned out of love. It lives for three years for some, for others for three months, and for the rest for only three days. Italian can easily carry you away: it’s beautiful and melodic, the language of fashion and art. However, this motivation is easy to lose. So always remind yourself why you fell in love with the language. Remember how you first wanted to learn Italian, when you saw a game by “Inter”Italian football team or watched The Taming of the Scoundrela 1980 feature film starring Adriano Celentano.

- Un passo alla volta, which means “step by step.” Learn gradually. Take your time with grammar. First, pay attention to Italian phonetics, reading rules, learn the first 100 words and basic constructions. Leave all the other complications for later. If you need italiano for study or work, you will have to get there anyway.

- Immerse yourself in the language environment. The ideal option is to go there to live, study at the university, or at least attend one-week courses. If that doesn’t suit you, surround yourself with Italy. And no, this does not mean eating pizza and drinking espresso every day (although this is also possible). Listen to Italian music and podcasts, watch TV shows and movies, switch your phone to Italian, and so on.

Lessico — Italian words

Vocabulary is the main component of the language. And you need to improve yours regularly and correctly. We will tell you about the methods of learning Italian words. Spoiler alert: there is no cramming in this section.

Borrowed words

Generous Italians have gifted many words to other languages, including English. They are familiar to everyone: bank, tomato, passport, etc. And don’t even get us started on lexical borrowings in culture and architecture:

- Balcone — balcony;

- Arca — arch;

- Museo — museum;

- Musica — music;

- Ballerina is still a ballerina.

English and Italian vocabulary are very similar. When learning italiano, pay attention to the roots of words. In English, they sound different, but the writing and meaning are the same. The Spanish speakers have nothing to do here. These languages are so close that you almost speak Italian already.

| Italian word | English word |

|---|---|

| Responsabile | Responsible |

| Celebrazione | Celebration |

| Drammatico | Dramatic |

| Generosità | Generosity |

Sometimes you come across words posing as others. For example, the Italian word camera means «room» and “camera” is macchina fotografica.

The Importance of context

A common mistake when learning new words is to take them out of context. How does it usually happen at school? We write down the vocabulary in a column, add the translations and memorize it all. You are lucky if the words were given on the same topic, for example, «medicine.» Then they are easier to remember. But more often than not, the vocabulary is given randomly: we begin with the verb mangiare — “to eat,” and end with tirapugni — “brass knuckles.” So no associations are built between words.

Therefore, it is best to learn vocabulary in context. You will sooner remember that mago is a «magician» if you read at least a few sentences where it is used. For example: Il mago ha fatto un incantesimo sul cavalierethe wizard cursed the knight; Il mago l’ha trasformato in una ranathe wizard has turned him into a frog. The same goes for the set expressions: alzare i tacchiflee (as in «run away»), montare la testato put on airs, etc.

List of necessary words

Make a list of essential words with which to start learning a language. Here we are talking not only about the clichéd «20 basic phrases in Italian», but also about what is important for you. Let’s say you love movies and can chat about them for hours. Find and make a list of words on the topic of «cinema». It will be easier for you to memorize new vocabulary, because it is related to the topic of interest to you. Plus, it will come in handy in communicating with the native, to tell about yourself and your hobbies.

Italian songs

Lingua italiana is a melodic language. There are just so many beautiful songs written in it. You don’t have to be an opera lover to listen to Italian music. Some of the most popular performers are Il Volo, Andrea Bocelli, Adriano Celentano, Laura Pausini, and others. Enjoy the music while learning new words. There are special apps to learn the language from the lyrics. For example, lyricstraining.com.

30 first verbs to learn in Italian

| Italian | Translation |

|---|---|

| Fare | Do |

| Chiedere / Domandare | Ask |

| Comprare | Buy |

| Bere | Drink |

| Stare | Stay |

| Mangiare | Eat |

| Trovare | Find |

| Finire | Finish |

| Dare | Give |

| Avere | Have |

| Andare | Go |

| Sentire | Hear /feel |

| Sapere / Conoscere | Know |

| Vivere | Live |

| Guardare | Look at |

| Aver bisogno | Have a necessity |

| Aprire | Open |

| Essere | Be |

| Pagare | Pay |

| Rispondere | Answer |

| Dire | Tell |

| Vedere | See |

| Sedersi | Sit |

| Parlare | Talk |

| Prendere | Take |

| Pensare | Think |

| Usare | Use |

| Aspettare | Wait |

| Volere / Desiderare | Want |

| Lavorare | Work |

| Scrivere | Write |

Daily Phrases

- Mi scusi — Sorry

- Per favore — Please;

- Prego — You’re welcome;

- Grazie — Thank you;

- Altrettanto — The same to you;

- Si / No — Yes / No;

- Buongiorno — Good afternoon (as a greeting);

- Buona giornata — Good day (as goodbye);

- Come ti chiami? — What is your name?

- Mi chiamo … — My name is …;

- Come? — What did you say? (as “could you repeat, please”)

- Non lo so — I don’t know;

- Non capisco — I don’t understand;

- Mi puo aiutare — Can you help me?

- Un caffè — Coffee (specifically espresso);

- Perché — Because;

Examples:

- Buongiorno, mi chiamo Alexa. Come ti chiami?

- Mi scusi, non capisco. Come?

- Si. Un caffè, per favore.

- Mi puo aiutare, per favore?

- Grazie, buona giornata.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificities |

| Italian Pod101 | A1-A2 | Playlist with videos for learning Italian from pictures. The vocabulary is broken down by topics. The pronunciation is also covered. |

| Italian Pod101 | A1-B1 | A list of 100 key Italian words with examples, pronunciation, and translations into English. |

| IE languages | B1-C1 | For those interested. Site with vocabulary of Romance languages: French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese (with translation into English). It clearly shows how similar their words are. |

| Garzanti Linguistica | B1-C1 | Explanatory dictionary in Italian. A good way to learn the meaning of new words. |

| Quizlet | A1-C1 | Online resource for working with flashcards. You can create your own set or use the existing ones. |

| Reverso Context | A1-C1 | A site where you can see the translation of words or phrases within context. |

| Anki | A1-C1 | Free platform for learning new words. Uses the spaced repetition method. |

Grammatica — Italian grammar

Grammar is one of the most difficult aspects of any language, and Italian is no exception. At first, it looks rather simple, but as the days get longer, the cold gets stronger. Every time you think you’ve learned a rule, a new detail appears, and then another and another. Here are some tricks that should help you to survive and not get lost in the thicket of Imperativo, Condizionale, and Congiuntivo.

Define a goal

First, define a goal. Why are you learning Italian? There are two main approaches: jumping straight into the rules or immersing yourself in the language — listen, watch and read, without delving into grammar. You don’t always need to know how something works in order to apply it in life. This is also true for foreign languages. To understand and speak it, you don’t need to waste time on a detailed analysis of grammar. Basic knowledge is enough for traveling and communication. But if you are taking CILS, going to study or work in Italy, it is better to understand the twists and turns of grammar rules from the very beginning.

First the rule — then practice

We analyze the rule and only then use it with examples. A universal order, which many tend to forget. In most textbooks, the authors first give texts with constructions unknown to the student and only afterward do they explain what has just happened. It’s much better to do it in the opposite order: read the rule → look at the examples → put it all into practice. The latter should preferably be done both in writing and out loud. This way, the grammar is also consolidated in oral speech.

Learn verb conjugation

Verbs are perhaps the most daunting part of Italian grammar. Mostly because of the conjugations that strike terror into the hearts of beginners. For example, the complete declension table of the verb essere — «to be» — in all tenses and forms looks like this:

In reality, everything is not that scary. In short, there are 3 groups of verbs in Italian:

- With the ending -are: lavorare — to work, visitare — to visit;

- With the ending -ere: scrivere — to write, decidere — to decide;

- With the ending -ire: dormire — to sleep, sentire — to feel/hear.

Within the same group, they all conjugate in the same way. Of course, there are exceptions. Every self-respecting language has a couple (dozen or hundred). But for the entry level, only the most basic ones are needed: essere — to be, and avere — to have.

Multiple sources are better than one

Get your knowledge of the language from different resources. Even if you are sure that you are studying the best textbook in the world, written by an Italian, still take several sources. Don’t limit yourself to one thing. Use the Internet, mobile applications, and other study materials: videos, podcasts, magazines, blogs, and more.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificity |

| Una grammatica italiana per tutti | A1-B2 | Italian grammar textbook for levels A1-B2. |

| Italian verbs | A1-C1 | Site with Italian verb conjugations. |

| Europass | A1-C1 | Site of the Italian language school. Explanation of Italian grammar from the articles to Subjunctive mode. |

Comprensione orale — What to listen to in Italian?

The most enjoyable part of learning Italian is listening. It is pleasant for two reasons. First, the very sound of lingua italiana. Second, the amount of fun and free study materials you can use. How to develop listening skills?

Films and TV shows

Watch movies and TV shows in Italian. It’s a fun and effective way to learn to understand native speakers. The only nuance is that it works well as an addition, but not as the primary method. Perhaps not everyone will like Italian cinema, but there are many world-famous classics among their directors. So getting to know them will be useful not only for language learning but also for general development. Famous Italian directors are Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Paolo Sorrentino, and so on.

You can find subtitled Italian films and series on streaming services like Netflix or YouTube. You can always find content with English subtitles, but if your level is B1 or higher, it is better to watch immediately with Italian subs. This way you will not get lost in translation and get the greatest benefits from the series.

Radio and podcasts

A great way to learn to understand a language is to listen to radio and podcasts. If you like the first option, then get ready. Italian speakers speak very quickly. There are many different stations: the first state-owned RAI Radio, the musical Lattemiele, the Neapolitan Radio Kiss Kiss Italia, and others.

Among the podcasts, we suggest you look into News in Slow Italian. This is a topical news program covering the field of politics, science, and culture. They are recorded at different speeds and vocabulary for levels from Beginner to Advanced. Plus, the site has free Italian courses and the news itself contains a transcript and even translations of some words. Other interesting resources: Italy made easy, Max Mondo, Sientificast, Daily Cogito. The last two are suitable for levels B2-C1.

Audiobooks

Another source for developing your language comprehension skills is audiobooks in Italian. Here the choice depends only on your preferences. In theory, you can even listen to those works that you do not understand. The bottom line is that you get used to Italian and after a while, you begin to distinguish between individual phrases and words. Audiobooks are easy to find on Audible, but they cost money. More options are available on YouTube or on LibriVox. And you can choose the book yourself: The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller by Italo Calvino, or whatever you like.

Italian YouTube

We promised that listening will be the most fun part of learning the language. Any resources are suitable for developing skills, and YouTube is no exception. Find Italian blogs with topics that interest you: the culture and life of the country, comedic sketches, film analysis, and more. A big advantage of this format is that people communicate less formally. From them you can learn trendy words, slang and other amenities of the Italian language, which you will not hear on the radio or in podcasts. Also try to watch bloggers from different cities. This will help you to better understand dialects and learn about the regional characteristics of Italy. Channels to look out for: Marcello Ascani, Massimo Polidoro, Breaking Italy.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificity |

| Italy made easy | A1-B2 | Podcast for Italian learners. The host, Manu, speaks the standard dialect, is slow and understandable. |

| Max Mondo | B1-B2 | Podcast about Italian culture. Designed for Intermediate learners. |

| Sientificast | B2-C1 | Italian science podcast. For those looking to expand their vocabulary in this topic. |

| Daily Cogito | B2-C1 | The host talks about current news, life, philosophy and other eternal topics. |

| News in Slow Italian | A1-C1 | News in Italian. The speed and vocabulary depend on the level: for beginners, it is easier. The hosts speak a wide variety of dialects. |

| LibriVox | A1-C1 A | A website with a selection of audiobooks in different languages, including Italian. Has both fairytales and serious literature. |

Lettura — What to read in Italian?

Reading in a foreign language is difficult. Many people postpone this skill for later. They think: «Now I will learn to speak, then enrich my vocabulary, and finally…» And finally what? In reality, without reading, you cannot improve other aspects of Italian. After all, from books you will learn new words and expressions that make speaking more interesting, and practice grammar at the same time. So what to read in italiano?

Adapted texts

For those who are just starting out on their journey of learning Italian, short stories and dialogues are suitable. They can be found in textbooks or on the internet. For example, sites such as Think in Italian or Lingua have easy texts specifically for the A2 level. When you get bored with such reading, move on to adapted works or books with parallel translation.

News

If you want to get a feel of the modern Italian language, read the news. This is a good way to train your reading skills and stay up-to-date with world events. Plus, this way you immerse yourself in the political and social life of Italy — you will find out what is important for the local population. Find extracts from the daily newspapers like Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, Il Messaggero, and La Stampa.

Fiction

It is impossible to learn Italian without referring to its literature. After all, the works of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio essentially became the primary source from which the modern version of the language emerged. We are not suggesting that you charge the classics of the Renaissance. This way you will scare both yourself and them. You need to gradually submerge in Italian literature. Below is a video showing Italians offering 15 of the best books to read in their language. You can choose one of the options, but always remember two rules: personal interest and level of language proficiency.

Better start with more relevant pieces. There you will find vocabulary that will be useful now, not 500 years ago. Books in Italian can be found on the Readlang, Liber Liber, and in many FB communities. Italiano enthusiasts enjoy sharing their accumulated wisdom.

Poems

This method is more suitable for developing the feeling of language and expanding your general outlook. If you have already reached the heights in Italian prose, try to study the subtle matters of poetry. Untranslated poems are easy to find on the Internet. For example, here on this resource there are poems with a parallel translation into English.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificity |

| Readlang | A1-C1 | Resource with books in various languages, including Italian. You can choose a piece by level. The reader gives a parallel translation of the words. |

| Liber Liber | A1-C1 | Site in Italian. There are audio and regular reading books. |

| Think in Italian | A1-C1 | More than 100 Italian proverbs for those who wish to enlarge their vocabulary. |

Produzione scritta — Let’s write in Italian

A big upside of the Italian language — words are written as they are heard. The difficulty in writing in italiano comes mainly from grammar and sounding like an italian. If you are learning the language for travels, you can omit the rules and practice of writing. But for those wishing to study and work in Italy, there is no escape from them. Take a notebook, a pen, and get ready for work.

Look at samples

Use materials that someone else has written as examples. It is better to take them from the native speakers themselves in order to write like a true Italian. A common mistake of foreign learners is direct translations. This is especially true for beginners who do not yet have a sense of the language. They take the sentence in their native language and translate it «as is» into Italian. Most often, it turns out logically and grammatically correct, but it is noticeable that a foreigner is writing. For example, you can start a business letter with the words “Buongiorno, …” and you will be understood. However, the locals are more likely to greet you like this: “Egregiodear (close to «darling») / Spettabiledear (more official) / Gentileestimable.” This also needs to be learned. Interaction with natives helps a lot in this.

Find a pen pal

To spice up your practice, chat in Italian. There are many platforms on the Internet where you can meet native speakers. For example, Tandem, Hello Talk, Ablo, or Interpals. Try to find someone who really fixes your shortcomings. Also, remember that «native» is not always equal to “flawless.” They can sometimes make mistakes in spelling and punctuation just like your doing in the English.

Corresponding with an Italian is great. But if your goal is to work and study in the country, business writing skills, essays and abstracts are required. So practice with all types of texts. Of course, here we are talking about people who have already reached the level of B1-B2. At the beginning of the journey, there is no point in tormenting yourself with the description of graphs in Italian.

Transcribe audios

Technique for intermediate to advanced level — listen to audio and write down a transcript of it (preferably by hand). This is how you simultaneously improve your listening skills and practice writing. At first it seems that this is quite easy, because in general you understand the announcer. But when it comes to writing every single word according to all the rules of grammar, the difficulty rises steeply. But do not worry, a couple of dozen texts and everything will go smoothly.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificity |

| HiNative | A1-C1 | Application where you can submit your proposal for verification to a native speaker. |

| Hello Talk | A1-C1 | Application for communicating with people from other countries. |

| Interpals | A1-C1 | Website for finding pen pals. |

| Languagetool | A1-C1 | Software, which checks texts for errors. Available for Italian. |

| Text Gears | A1-C1 | Resource for Italian Spelling and Grammar. |

Produzione orale — How to speak Italian?

One of the main goals for Italian learners is to learn how to speak it. Fortunately, this is not the most difficult aspect of the language. The main thing is to practice a lot and correctly.

Find a conversation partner

The best way to develop your communication skills is to find a conversation partner. Ideally, they should be Italian. With a partner, you not only train speaking but also get acquainted with the peculiarities of Italian mentality. A native speaker will tell you about the intricacies of pronunciation and use of specific words. Check out italki, Speaky, or Easy Language Exchange. There you can find teachers of Italian and just friends for communication.

But you don’t have to practice exclusively with native speakers. Foreigners who speak italiano also work fine. Try talking clubs, which are often found in language schools and cultural centers. Just choose a group according to your level. If you already have B1, you may not be very comfortable interacting with beginners.

Speak all the phrases out loud

Learning a language while silently moving your lips will not work. You need to speak Italian right away. Now you have learned the first 30 or 300 — no matter how many — words. Take them and make a sentence, and then be sure to say it out loud. If it’s hard for you, read ready-made Italian texts aloud. You need to get used to speaking Italian, and train your vocal apparatus. Otherwise, there is a risk of crashing into the language barrier. A person can know the entire vocabulary inside out, but find it difficult to connect words in speech.

Expand your vocabulary

The vocabulary is divided into passive and active. The first is vocabulary that you only learn but rarely use. The second is regularly used phrases. To communicate fluently in Italian, you need to move as many words as possible from passive to active. How? Through practice, of course. As soon as you learn a new word, immediately add it to your speech. Repeat it one, two, ten times to secure. It is important to do this in context, as part of a phrase.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificities |

| italki | A1-C1 | Resource for finding a teacher among native speakers of Italian. |

| Speaky | A1-C1 | An application for communicating with foreigners. Video and audio chat available. |

| Easy Language Exchange | A1-C1 | Platform for finding speakers of another language for mutual learning. |

| Tandem | A1-C1 | A platform for meeting native speakers. |

Pronuncia — How to master Italian pronunciation?

First, let’s define what «Italian» pronunciation is, and if it exists at all. The special feature of lingua italiana is the huge number of dialects, which in fact were formed as separate languages. Italy had been a country of city-states for a long time, so each region has its own dialect. And although they are all rooted in Latin, they sound completely different. Today, the most common variant is the official Italian, created after the unification of Italy. The second most popular language is the Neapolitan language. It is used in the south of the country.

«Neutral» Italian

Foreigners are advised to learn the official version of italiano. In general, with Italian it is best to focus on the correct pronunciation of words first. And only after, when you have already reached an advanced level, sharpen your accent. The easiest and most efficient way is to move to Italy. Sounds tempting, but expensive, and doesn’t suit everyone. Another option is classes with a professional linguist (maybe an Italian) who will correct all your mistakes. But even without the accent, they will understand you in any case. The question is what do you want: just speak the language or speak like a local. If the former, then leave the accent correction for last.

Observe the articulation

Italian pronunciation is characterized by distinct articulation. Therefore, when learning a language, it is important not only to listen, but also to watch how the native speaker talks. Pay attention to the movement of the lips, tongue: how wide the mouth opens on vowel sounds, how consonants are annunciated, and so on.

Learn gestures

No Italian conversation is complete without active gestures. Non-verbal communication plays a large role in their daily life, so we advise you to study it. Facial expressions, gestures and posture are special parts of the language. It is best to practice speaking with native speakers. Or you can watch the video on YouTube. For example, here are 60 Italian gestures explained (and this is just a part). Well, for aesthetes there is a similar video from Dolce & Gabbana. It is also worth mentioning that the Italians in the comments easily spot foreign models by incorrectly shown gestures. Can you?

But be careful. Do not mindlessly copy every movement of local residents. Otherwise, there is a risk of slipping into the parody zone and offending everyone around you. It is important to understand the true meaning of the gesture (in different situations and regions). This aspect of the language should be considered when you are already on C1-C2 level.

Resources

| Resource | Level | Specificity |

| The mimic method | A1-A2 | Detailed explanation of Italian pronunciation. |

| Learn Italian with Italy Made Easy | A1-A2 | An Italian explains how to pronounce vowels correctly. The video has a second part. |

| Forvo | A1-C1 | Pronunciation dictionary. You can hear Italian words read by a native. |

Need to learn a language?

There are four main options for where to learn Italian:

- Language school (group lessons);

- Individual lessons with a tutor;

- Language courses abroad;

- On your own.

Italian courses abroad

| City | Min. cost of Standard Coursesone week, accommodation not accounted for | Min. cost of Intensive Coursesone week, accommodation not accounted for |

|---|---|---|

| Rome | 273 USD | 357 USD |

| Turin | 242 USD | 273 USD |

| Florence | 231 USD | 347 USD |

| Cefalu | 189 USD | 368 USD |

| Genoa | 265 USD | 372 USD |

Resources for self-studying Italian

| Resource | Specificity |

|---|---|

| Learn Italian with Italy Made Easy | Another YouTube channel. Native speaker explains study material in English and Italian. |

| Rocket Languages | A learning platform. The link is to a selection of study materials in Italian. They are all organized by topic: grammar, vocabulary, phonetics, etc. |

| Fluent U | Learn Italian with videos and music. The site requires a subscription, but you can try it for 14 days for free. |

| Memrise | Site with courses in different foreign languages. The vocabulary is broken down by topic. Lessons are gamified. To watch, you need to register. |

| Yabla Italian | Resource for learning Italian using videos with subtitles. You can adjust the speed of the video and watch the translation of individual words. |

| Learn Italian with Lucrezia | YouTube channel of an Italian woman who explains the rules and subtleties of her native language. The videos have English subtitles. |

| ItalianPod101 | YouTube channel by an Italian online school. You can sign up for their courses, but they are paid, and the videos are not. |

Why learn Italian?

Lingua italiana is significantly less widespread than English and Chinese. But you probably know at least a couple of Italian words and use them regularly in your everyday life. For example, when you order pizza or go to the bank. So you are surrounded by Italy. In addition, italiano is the fourth most studied language in the world. A very good achievement for its relatively small size. Why do people learn Italian?

Italian for Study

Italy is one of the most affordable European countries for study. The average tuition fee is 4,421 USD per year. There are also many ancient universities: Bologna, Padua, Neapolitan and others. Plus, universities in Italy provide students with good scholarships — from 1,105 USD to 11,051 USD. They cover tuition and living expenses. True, to study there you need to know italiano. There are programs in English, but there are much fewer of them. And the level of fluency in the country is not the highest (worse than in Bulgaria). Foreign students say that knowledge of Italian is necessary for staying in the country anyway. The standard admission requirement is B2. To prove your level of proficiency, you need to pass one of the exams. Most often it is CILS, but there are also CELI and PLIDA.

So if you are planning to study in Italy, it is better to study with a tutor right away. Find a tutor who has personally taken one of the exams, or sign up for a preparatory course at a language school. In theory, preparing for CILS on your own is possible, but then you should study using special textbooks to understand the format of the assignments.

Italian for work

In terms of international business, Italian offers fewer opportunities than Spanish or French. However, if you want to work in the country, then you cannot do it without knowing the local language. This is not a mandatory requirement and no one will ask you for confirmation to get a work visa. But it is still desirable to own it at least at the level B1-B2.

Get ready though — it is not easy to find a job in Italy. The unemployment rate among foreigners is one of the highest in Europe at 13.1%[1]. The problem of finding a job is also relevant for Italians themselves. Over the past few years, more than 800,000 young people have left the country. This is more than the entire population of Palermo[2]. The main reasons are a lack of jobs and poor career prospects.

It is easiest for foreigners to find a job where special qualifications are not required: nanny, worker, entertainer, housemaid, and so on. You can also find a job as an English or another language teacher. Also, always remember that every region of Italy is like a mini-country. Salaries, requirements and the approach to foreigners differ. For example, in the South it will be easier to find a job without knowing italiano. But in the North, you will most likely be checked for your level of language proficiency.

Italian for immigration

There are people who study Italian for one specific purpose — to immigrate. In general, this can be done without knowing italiano. There are many examples of people coming to Italy without knowing the language and staying for life. But we advise you to study it up to level A2-B1. This way, you will avoid problems in everyday communication at first. Knowledge of Italian is essential in any case: without it, you cannot become a part of society. Of course, someone just wants to live in Italy, but what’s the point if you remain an alien to the locals?

The process of obtaining citizenship here is not the fastest (in fact, like all bureaucratic procedures), and takes up to 10 yearsthrough employment. If you graduate from an Italian university, you are given a year to stay in the country and look for a job.

| City | Living expenses per month, not counting rent. | Average monthly salary, net. |

|---|---|---|

| Rome | 918 USD | 1,621 USD |

| Venice | 1,011 USD | 1,823 USD |

| Naples | 807 USD | 1,292 USD |

| Palermo | 718 USD | 1,286 USD |

| Florence | 881 USD | 1,552 USD |

| Milan | 935 USD | 1,804 USD |

Italian for travel

Every year Italy attracts millions of tourists[3]. This amazing country offers travelers everything: delicious food, beautiful landscapes, historical sites and hospitable locals. It’s a great idea to drive through Italy to see all the regions. Indeed, each has its own peculiarities of language, mentality, traditions and even cuisine. Don’t forget that Italian is also useful for visiting other countries: Switzerland, San Marino, as well as some regions of Slovenia and Croatia.

If you are learning italiano for traveling, then focus on speaking, listening, and vocabulary. Choose the words and phrases that you need first. Below is a list of the most important expressions for tourists. Better learn them beforehand. This is more convenient than looking in the dictionary every other minute.

15 phrases in Italian for a tourist

- Parla inglese? — Do you speak English?

- Non parlo l’italiano — I don’t speak Italian

- Non capisco — I don’t understand

- Siamo stranieri / Sono straniero — We are foreigners / I’m a foreigner

- Grazie mille — Thank you very much!

- Quanto costa (questo)? — How much does it cost?

- Come si arriva a …? — How to get to…?

- Dov’è il bagno? — Where is the restroom?

- Vorrei … — I would like to …

- Vorrei vedere questo, per favore — I would like to see this, please …

- Mi puo aiutare — Can you help me?

- Gira a destra / a sinistra — Turn right / left

- Va dritto — Go straight

- Aperto / Chiuso — Open / closed

- Aiuto! — For help!

Italian for yourself

Study, work, and immigration are all noble reasons for learning Italian, but far from the only ones. Many people choose it for its sound and beauty. Others admire the expressiveness and the flamboyant temperament of the natives. And others fall in love with Italian cuisine. Whichever category you put yourself in, the main thing is to stay motivated. Learning lingua italiana «for yourself» is the hardest part, especially if you study it on your own. In order not to lose your enthusiasm, remind yourself why you decided to take on this feat at all. Revisit that movie with Marcello Mastroianni that won you over, or listen to a concert of Il Volo.

Find language courses

Italian Exams

To confirm the level of proficiency, you must pass an international exam. This is required for entry to university and getting a job in Italydepends on the employer. There are several options for Italian:

- CELI;

- CILS;

- PLIDA

The most popular is CILS (Certificazione di Italiano come Lingua Straniera). It has four levels, with 1 being «beginner» and 4 being “native.” The exam has five sections:

- Listening;

- Reading;

- Letter;

- Vocabulary / grammar;

- The oral part.

In CELI (Certificati di Lingua Italiana) there is one more level — 5 major ones, plus an additional CELI Impatto equal to A1. Also, the test does not have separate lexical and grammatical parts.

Unlike English IELTS and TOEFL, all certificates are perpetual.

More details

This article is about the Italian language. For the regional varieties of standard Italian, see Regional Italian.

| Italian | |

|---|---|

| italiano, lingua italiana | |

| Pronunciation | [itaˈljaːno] |

| Native to | Italy, San Marino, Vatican City, Switzerland (Ticino and Italian Grisons), Slovenia (Slovenian Littoral), Croatia (Western Istria) |

| Ethnicity | Italians |

| Speakers | Native: 65 million (2012)[1] L2: 3.1 million[1] Total: 68 million[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Old Latin

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

Latin (Italian alphabet) Italian Braille |

|

Signed forms |

Italiano segnato «(Signed Italian)»[2] italiano segnato esatto «(Signed Exact Italian)»[3] |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

4 countries

2 regions

An order and various organisations

|

|

Recognised minority |

Bosnia and Herzegovina[a] |

| Regulated by | Accademia della Crusca (de facto) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | it |

| ISO 639-2 | ita |

| ISO 639-3 | ita |

| Glottolog | ital1282 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-q |

Official language Former co-official language Presence of Italian-speaking communities |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Italian (italiano [itaˈljaːno] (listen) or lingua italiana [ˈliŋɡwa itaˈljaːna]) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin.[6][7][8][9] Spoken by about 85 million people (2022), Italian is an official language in Italy, Switzerland (Ticino and the Grisons), San Marino, and Vatican City. It has official minority status in Croatia and in some areas of Slovenian Istria.

Italian is also spoken by large immigrant and expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia.[1] Italian is included under the languages covered by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Romania, although Italian is neither a co-official nor a protected language in these countries.[5][10] Many speakers of Italian are native bilinguals of both Italian (either in its standard form or regional varieties) and a local language of Italy, most frequently the language spoken at home in their place of origin.[1]

Italian is a major language in Europe, being one of the official languages of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and one of the working languages of the Council of Europe. It is the second-most-widely spoken native language in the European Union with 67 million speakers (15% of the EU population) and it is spoken as a second language by 13.4 million EU citizens (3%).[11][12] Including Italian speakers in non-EU European countries (such as Switzerland, Albania and the United Kingdom) and on other continents, the total number of speakers is approximately 85 million.[13] Italian is the main working language of the Holy See, serving as the lingua franca (common language) in the Roman Catholic hierarchy as well as the official language of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. Italian has a significant use in musical terminology and opera with numerous Italian words referring to music that have become international terms taken into various languages worldwide.[14] Italian was adopted by the state after the Unification of Italy, having previously been a literary language based on Tuscan as spoken mostly by the upper class of Florentine society.[15] Almost all native Italian words end with vowels and has a 7-vowel sound system (‘e’ and ‘o’ have mid-low and mid-high sounds). Italian has contrast between short and long consonants and gemination (doubling) of consonants.

History[edit]

«History of Italian» redirects here. For the history of the Italian people, see Italians. For the history of the Italian culture, see culture of Italy.

Origins[edit]

During the Middle Ages, the established written language in Europe was Latin, though the great majority of people were illiterate, and only a handful were well versed in the language. In the Italian Peninsula, as in most of Europe, most would instead speak a local vernacular. These dialects, as they are commonly referred to, evolved from Vulgar Latin over the course of centuries, unaffected by formal standards and teachings. They are not in any sense «dialects» of standard Italian, which itself started off as one of these local tongues, but sister languages of Italian. Mutual intelligibility with Italian varies widely, as it does with Romance languages in general. The Romance languages of Italy can differ greatly from Italian at all levels (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, pragmatics) and are classified typologically as distinct languages.[16][17]

The standard Italian language has a poetic and literary origin in the writings of Tuscan and Sicilian writers of the 12th century, and, even though the grammar and core lexicon are basically unchanged from those used in Florence in the 13th century,[18] the modern standard of the language was largely shaped by relatively recent events. However, Romance vernacular as language spoken in the Italian Peninsula has a longer history. In fact, the earliest surviving texts that can definitely be called vernacular (as distinct from its predecessor Vulgar Latin) are legal formulae known as the Placiti Cassinesi from the Province of Benevento that date from 960 to 963, although the Veronese Riddle, probably from the 8th or early 9th century, contains a late form of Vulgar Latin that can be seen as a very early sample of a vernacular dialect of Italy. The Commodilla catacomb inscription is also a similar case.

The Italian language has progressed through a long and slow process, which started after the Western Roman Empire’s fall in the 5th century.[19]

The language that came to be thought of as Italian developed in central Tuscany and was first formalized in the early 14th century through the works of Tuscan writer Dante Alighieri, written in his native Florentine. Dante’s epic poems, known collectively as the Commedia, to which another Tuscan poet Giovanni Boccaccio later affixed the title Divina, were read throughout the peninsula and his written dialect became the «canonical standard» that all educated Italians could understand. Dante is still credited with standardizing the Italian language. In addition to the widespread exposure gained through literature, the Florentine dialect also gained prestige due to the political and cultural significance of Florence at the time and the fact that it was linguistically an intermediate between the northern and the southern Italian dialects.[16]: 22 Thus the dialect of Florence became the basis for what would become the official language of Italy.

Italian was progressively made an official language of most of the Italian states predating unification, slowly replacing Latin, even when ruled by foreign powers (like Spain in the Kingdom of Naples, or Austria in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia), even though the masses kept speaking primarily their local vernaculars. Italian was also one of the many recognised languages in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Italy has always had a distinctive dialect for each city because the cities, until recently, were thought of as city-states. Those dialects now have considerable variety. As Tuscan-derived Italian came to be used throughout Italy, features of local speech were naturally adopted, producing various versions of Regional Italian. The most characteristic differences, for instance, between Roman Italian and Milanese Italian are syntactic gemination of initial consonants in some contexts and the pronunciation of stressed «e», and of «s» between vowels in many words: e.g. va bene «all right» is pronounced [vabˈbɛːne] by a Roman (and by any standard Italian speaker), [vaˈbeːne] by a Milanese (and by any speaker whose native dialect lies to the north of the La Spezia–Rimini Line); a casa «at home» is [akˈkaːsa] for Roman, [akˈkaːsa] or [akˈkaːza] for standard, [aˈkaːza] for Milanese and generally northern.[20]

In contrast to the Gallo-Italic linguistic panorama of Northern Italy, the Italo-Dalmatian, Neapolitan and its related dialects were largely unaffected by the Franco-Occitan influences introduced to Italy mainly by bards from France during the Middle Ages, but after the Norman conquest of southern Italy, Sicily became the first Italian land to adopt Occitan lyric moods (and words) in poetry. Even in the case of Northern Italian languages, however, scholars are careful not to overstate the effects of outsiders on the natural indigenous developments of the languages.

The economic might and relatively advanced development of Tuscany at the time (Late Middle Ages) gave its language weight, though Venetian remained widespread in medieval Italian commercial life, and Ligurian (or Genoese) remained in use in maritime trade alongside the Mediterranean. The increasing political and cultural relevance of Florence during the periods of the rise of the Medici Bank, humanism, and the Renaissance made its dialect, or rather a refined version of it, a standard in the arts.

Renaissance[edit]

The Renaissance era, known as il Rinascimento in Italian, was seen as a time of rebirth, which is the literal meaning of both renaissance (from French) and rinascimento (Italian).

Venetian Pietro Bembo was an influential figure in the development of the Italian language from the Tuscan dialect, as a literary medium, codifying the language for standard modern usage.

During this time, long-existing beliefs stemming from the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church began to be understood from new perspectives as humanists—individuals who placed emphasis on the human body and its full potential—began to shift focus from the church to human beings themselves.[21] The continual advancements in technology play a crucial role in the diffusion of languages. After the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century, the number of printing presses in Italy grew rapidly and by the year 1500 reached a total of 56, the biggest number of printing presses in all of Europe. This enabled the production of more pieces of literature at a lower cost and as the dominant language, Italian, spread.[22]

Italian became the language used in the courts of every state in the Italian Peninsula, as well as the prestige variety used on the island of Corsica[23] (but not in the neighbouring Sardinia, which on the contrary underwent Italianization well into the late 18th century, under Savoyard sway: the island’s linguistic composition, roofed by the prestige of Spanish among the Sardinians, would therein make for a rather slow process of assimilation to the Italian cultural sphere[24][25]). The rediscovery of Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia, as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. This discussion, known as questione della lingua (i.e., the problem of the language), ran through the Italian culture until the end of the 19th century, often linked to the political debate on achieving a united Italian state. Renaissance scholars divided into three main factions:

- The purists, headed by Venetian Pietro Bembo (who, in his Gli Asolani, claimed the language might be based only on the great literary classics, such as Petrarch and some part of Boccaccio). The purists thought the Divine Comedy was not dignified enough because it used elements from non-lyric registers of the language.

- Niccolò Machiavelli and other Florentines preferred the version spoken by ordinary people in their own times.

- The courtiers, like Baldassare Castiglione and Gian Giorgio Trissino, insisted that each local vernacular contribute to the new standard.

A fourth faction claimed that the best Italian was the one that the papal court adopted, which was a mixture of the Tuscan and Roman dialects.[26] Eventually, Bembo’s ideas prevailed, and the foundation of the Accademia della Crusca in Florence (1582–1583), the official legislative body of the Italian language, led to the publication of Agnolo Monosini’s Latin tome Floris italicae linguae libri novem in 1604 followed by the first Italian dictionary in 1612.

Modern era[edit]

An important event that helped the diffusion of Italian was the conquest and occupation of Italy by Napoleon in the early 19th century (who was himself of Italian-Corsican descent). This conquest propelled the unification of Italy some decades after and pushed the Italian language into a lingua franca used not only among clerks, nobility, and functionaries in the Italian courts but also by the bourgeoisie.

Contemporary times[edit]

Alessandro Manzoni set the basis for the modern Italian language and helping create linguistic unity throughout Italy.[27]

Italian literature’s first modern novel, I promessi sposi (The Betrothed) by Alessandro Manzoni, further defined the standard by «rinsing» his Milanese «in the waters of the Arno» (Florence’s river), as he states in the preface to his 1840 edition.

After unification, a huge number of civil servants and soldiers recruited from all over the country introduced many more words and idioms from their home languages—ciao is derived from the Venetian word s-cia[v]o («slave», that is «your servant»), panettone comes from the Lombard word panetton, etc. Only 2.5% of Italy’s population could speak the Italian standardized language properly when the nation was unified in 1861.[1]

Classification[edit]

Italian is a Romance language, a descendant of Vulgar Latin (colloquial spoken Latin). Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, especially its Florentine dialect, and is, therefore, an Italo-Dalmatian language, a classification that includes most other central and southern Italian languages and the extinct Dalmatian.

According to Ethnologue, lexical similarity is 89% with French, 87% with Catalan, 85% with Sardinian, 82% with Spanish, 80% with Portuguese, 78% with Ladin, 77% with Romanian.[1] Estimates may differ according to sources.[28][29]

One study, analyzing the degree of differentiation of Romance languages in comparison to Latin (comparing phonology, inflection, discourse, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation), estimated that distance between Italian and Latin is higher than that between Sardinian and Latin.[30] In particular, its vowels are the second-closest to Latin after Sardinian.[31][32] As in most Romance languages, stress is distinctive.[33]

Geographic distribution[edit]

A map showing the Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland: the two different shades of blue denote the two cantons where Italian is the official language, dark blue shows areas where Italian is spoken by an important part of the population

Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries’ populations. Italian is the third most spoken language in Switzerland (after German and French), though its use there has moderately declined since the 1970s.[34] It is official both on the national level and on regional level in two cantons: Ticino and the Grisons. In the latter canton, however, it is only spoken by a small minority, in the Italian Grisons.[b] Ticino, which includes Lugano, the largest Italian-speaking city outside Italy, is the only canton where Italian is predominant.[35] Italian is also used in administration and official documents in Vatican City.[36]