Wiki User

∙ 14y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Language is generally written with the characters 语言, pronounced

yu3yan2 (in pinyin romanization).

Wiki User

∙ 14y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: How do you spell the word language in Chinese?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

For many, learning Chinese is a road strewn with broken glass, which has to be walked barefoot. The guide below will clear the path in front of you and give you directions. We have collected a lot of resources and tips that will be useful for any level of language proficiency. So sit back and 我们走吧!

Features of the Chinese language

- Pronunciation and spelling. It is impossible to determine the pronunciation of a hieroglyph by its appearance. Therefore, oral and written speech in Chinese are two different worlds. You can speak fluently about everyday topics, but still, be unable to write or read.

- Many dialects. In fact, Chinese is not just one language, but a whole group. Usually, they are called dialects, but many of them are so different from each other that they are more like separate languages: a speaker of a northern dialect will not understand a speaker of a southern one. In China, as well as in Singapore and Taiwan, Standard Chinese, also known as Mandarin, is the officially recognized language. It is spoken by the majority of China’s population — 65%. In total, there are 10 large groups of languages in China, which make up a total of 266 dialects. On the other hand, different dialects use the same writing rules. Therefore, even if their speakers do not understand each other verbally, they will be able to explain themselves using paper and pen.

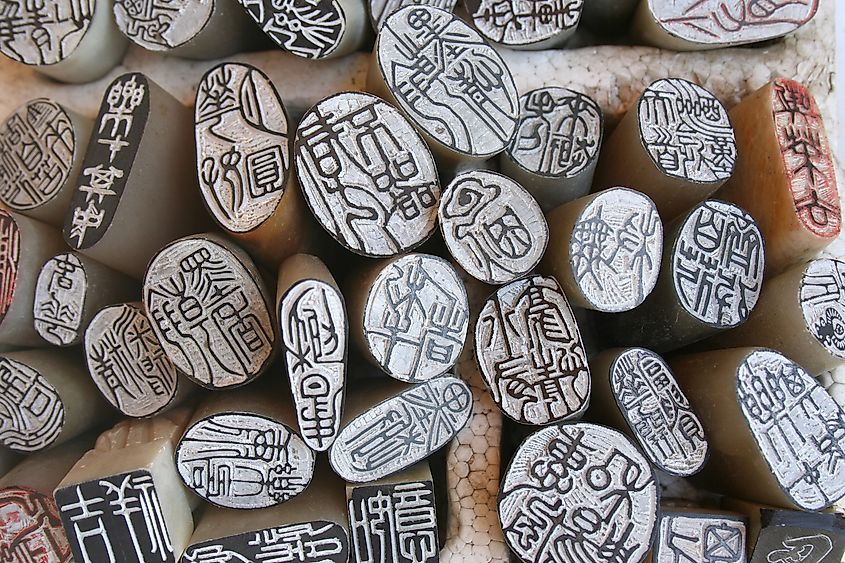

- Hieroglyphs. The Chinese language is famous for its complex hieroglyphic writing. The difference between a hieroglyph and a letter is that the letter only indicates a sound, while hieroglyphs also have their own meanings. The simplest hieroglyphs are called pictographic. These are schematic drawings of real objects. But more complex signs have nothing to do appearance-wise with what they represent. Such hieroglyphs, like building blocks, are made up of components — graphemes. Through them, it is easy to memorize the whole symbol. For fluency in the language, it is enough to know 3000-3500 hieroglyphs. Words sometimes consist of several symbols, therefore, having learned 3000 characters, you will be able to make several times more words out of them.

- Tones. One of the biggest challenges for all beginners who learn Chinese is the tones. You may have already heard that you “cannot learn Chinese without absolute pitch.” This is not at all true — the tones are approachable by anyone. Each hieroglyph represents a syllable, and the tone is a change of pitch within the syllable. There are four of them, plus the “neutral” tone, which sounds muffled, and the pitch does not change. Knowing the tones is important because they affect the meaning of the word. For example, the syllable ma, depending on the tone, can mean “mom,” “horse,” “hemp,” and the verb “to scold.”

- Transcription. Chinese words can be written not only in hieroglyphs but also in Latin letters. For this purpose, there is a separate system of transcribing — Pinyin (pīnyīn). It also reflects the tones of the syllables, so at the initial stage, it will greatly assist you in studying.

- There are many similar words. In Chinese, many words sound the same but are written in different characters. For example, not accounting for the tones, 177 hieroglyphs are read as [yi]. This phenomenon is called homophony. To illustrate it, a Chinese-American linguist Zhao Yuanren wrote the poem Shī Shì shí shī shǐ (Lion-eating Poet in a Stone Den), consisting only of tonal varieties of the syllable shi. You can listen to it here.

- Simplified and traditional writing. Modern Chinese writing has two variants — simplified and traditional. Simplified hieroglyphs have fewer strokes. They were introduced in the 1950s in China to raise literacy levels. Simplified writing is also used in Singapore and Malaysia. Traditional hieroglyphs are more complex. They are still used in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. At the same time, it cannot be said that if you learn traditional hieroglyphs, you will automatically know the simplified versions. They are quite different: 遠 → 远 (yuǎn — “far away”), 後 → 后 (hòu — “after”), 國 → 国 (guó — “country”).

- Grammar. The basic grammar of Chinese is pretty simple. Parts of speech do not inflect, nouns do not have cases and genders, and verbs have no tenses. Therefore, you do not have to struggle with case agreements. The one hard part is to master the word order in sentences. Everything else relies on it.

How do I learn Chinese on my own?

The Chinese language is dauntingly complex at first glance. It seems to many that only superhumans with some special and mysterious «talent for languages» can learn it. This is not true. It is possible to learn Chinese, but it is indeed much more difficult than, say, German or Russian. And a lot depends on the goals that you set.

If you want to work professionally with the Chinese language, it is better to find a tutor right away or sign up for a course. But the so-called level of «survival» is quite achievable even by studying independently. At this point, you should concentrate on colloquial phrases — writing is not so useful. But in order to conduct correspondence with business partners, the spoken speech comprehension skill, on the contrary, is not so important. Below we give tips on how to fully master the language. First of all, a few basic rules:

- Exercise every day. This is critical. Without daily practice, knowledge will flow out of your head like water through a sieve. So 20 minutes every day is better than a five-hour marathon on Sundays.

- Schedule your classes. Without a teacher, it is difficult to control oneself. When difficulties begin (which is inevitable), you will want to postpone the lesson for the evening, for tomorrow, for the next week — for later. Unfortunately, “later” may never come. To avoid this, discipline yourself. Make a schedule and obey it. It will help you separate your studies from the rest of your daily life and make them almost a ritual.

- Don’t be afraid of difficulties. When you are just starting to learn Chinese, you have to digest a lot of new information: unusual sounds, tones, hieroglyphs, symbols. But after a certain point, your knowledge will snowball. It will become easier for you to memorize new hieroglyphs when you understand what they are made of. And there will be no problems with the perception of speech when you master the tones and vocabulary. So the efforts at the initial stage will pay off handsomely.

- Love Chinese. The best motivation for learning a language is genuine interest. With it, you will not have to force yourself to study, and you will learn new words and hieroglyphs not only from textbooks but from a variety of sources. So if you started learning Chinese not out of love for the language or culture itself, but for practical reasons, try watching TV shows, listening to Chinese music, and reading literature. In general, find something that will hook you.

Pinyin — Chinese transcription

Pinyin (pīnyīn) is the official phonetic system that regulates the reading of Chinese hieroglyphs. It uses Latin letters, so mastering it will not be a problem. This must be the first thing done when learning Chinese. Pinyin will help you figure out what sounds are generally used in Chinese and how to pronounce them correctly. This is the most fundamental skill for learning the language.

Master the theory first. In Chinese, sounds are usually divided not into consonants and vowels, but into initials and finals. The initial is the sound with which the syllable begins, the final is the sound with which it ends. There are 21 initials and 34 finals in Chinese. In total, they create about 400 combinations. Additionally, in pinyin, many characters are read differently than we are used to. Zh, ch, and j are especially difficult for beginners.

Once you have mastered pinyin, you can type in Chinese on your computer. This is done very simply — enter the reading of the hieroglyph in the Latin alphabet, and then select the one you want from the list that appears (many of the hieroglyphs have the same readings). So once you learn pinyin, you can use the vocabulary and even communicate with the Chinese.

Tones — basic Chinese pronunciation

The number of sounds in the Chinese language is limited, while the number of homophones — the same sounding words — is very large. In order for the words to somehow differ, a special system for changing the pitch of the voice, that is, tones, has developed in the language.

While learning pinyin and the basics of phonetics, you will inevitably get to tones. And it is better to immediately give them due attention so that later you do not have to retrain. After all, if you completely ignore the tones, you will be misunderstood or not understood at all. For example, the words «soup» and “sugar” are pronounced with the same sounds, but in different tones — tāng and táng, respectively. Therefore, if in a restaurant you ask for soup, but use the wrong tone, the waiter will bring you sugar or will not understand at all what you are asking. Occasional mistakes are fine, but in order for them to stay rare, you still need to know the tones.

There are four tones in total, and the fifth is neutral — rather, it indicates the absence of a tone. You don’t need an ear for music to master them. Intonation in English works in a similar way — you already change your tone of voice when you ask a question or exclaim. There are three steps you need to take on the path to practicing tones.

Learn to hear tones

If you are just starting to learn the language, you will likely find it difficult to hear the difference between tones. After all, the brain of a person speaking a European language is not sculpted from early childhood to recognize such changes in voice. This skill needs to be taught.

Try saying the word «yes» in a declarative tone. Imagine answering confidently: “Have you completed the task? — Yes.” And then say it again, but as a response: “John, can you come here for a moment? — Yes?” Continue with an exclamation: “Do you want a promotion? — Yes!” Feel the difference? Now do the same, but with the Chinese syllable ma. Hear how the same syllable is pronounced in different tones in the table. Feel the similarities with what you were doing just now? You can practice here.

Once you get used to it, move on to words with two syllables. It is better to listen to how the tones are pronounced together, one after the other. In context, they can be more difficult to distinguish, so they should not be studied in isolation. For training, use resources like FluentU. There you can listen to how words are pronounced by native speakers.

Practice pronunciation

As you listen, repeat the sounds after the recording. Do this slowly and in an exaggerated manner, so that you can better feel the difference between the words. With a neutral tone, do the opposite — you don’t need to highlight it at all. Over time, the muscles of the mouth and lips will get used to the new sounds, and then you will not have to put in as much effort.

Ideally, you should find a native speaker who can correct you and explain what you are pronouncing incorrectly. This can be done using various services such as italki or Speaky.

If you can’t find a teacher, try recording your voice. Compare the recording with the pronunciation from the sample recordings, so the difference will be easier to spot. In general, if you hear that you speak differently from the examples, that’s good. This means that you can feel the difference between the tones. You will get better eventually and your pronunciation will become more natural.

Memorize the tones

Words must be memorized in conjunction not only with the spelling but also with the tones. This is very important, as a word spoken with the wrong tone can have a completely different meaning. Memorizing may seem tedious, but remember that the more effort you put into learning the tones in the beginning, the less you will have to relearn later. To make the associative bridge between written and spoken words stronger, say them out loud whenever you learn, and repeat them several times.

Basic words

It is best to practice pronunciation using basic words. This way, you will kill two hawks with one arrow — you will both learn the tones and become able to, for example, introduce yourself, or make an order in a restaurant. A list of the most common words with pronunciation can be found here.

Expand the list of topics gradually. Learn to talk about your family, hobbies, favorite food, or whatever interests you. Words combined into groups are much better remembered. If you study from a textbook (more about those a little later), then there you will also find such a system. The apps Duolingo and Memrise are also great for expanding your vocabulary. Finally, words can be taken from ChinesePod podcasts.

Resources

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Arch Chinese | Simulator for training tones by listening |

| Pleco | Online Dictionary. For an additional fee, it offers audio recordings of words that can be used to train tones |

| FluentU | Chinese audio and video |

| Sinosplice | An app for practicing tones in combinations |

What is a Chinese character

Once you have mastered the basics of pronunciation and vocabulary, you can move on to learning writing. First of all, figure out what a hieroglyph is. This will help you memorize them most effectively.

How many hieroglyphs are there in Chinese?

A hieroglyph is a symbol that, unlike a letter, not only contains a sound, but also a meaning. Moreover, a hieroglyph is not always equal to a word. Most often they consist of two characters.

The total number of characters in the Chinese language exceeds 80 thousand. But do not be alarmed, for fluency in the language (level C1) it is enough to know 3000-3500. More than 3000 will be required only if you are studying classical literature or historical chronicles.

Stroke

The most basic element of a hieroglyph is the stroke. There are 24 types of them. You need to learn how to write them at the very beginning.

The strokes of a hieroglyph are written in a specific order, according to the rules. There are eight of these rules, and it’s best to remember them. Here’s why:

- This is really the most convenient way to write hieroglyphs. The system has been perfected over several millennia, and you are unlikely to come up with anything better.

- Knowing the order of the strokes makes the hieroglyph easier to learn and write correctly.

- A handwritten hieroglyph can often only be recognized by the correct order of strokes.

Read more about the order of strokes here.

Pictographic hieroglyphs

Pictographic hieroglyphs are the simplest type. Initially, they were schematic representations of objects in the surrounding world. The connection between their look and meaning can still be traced. In the hieroglyph 魚, for example, a fish with a head, body, and tail is recognizable, in the hieroglyph 山 — mountains, and in 人 — a person with two legs. Such characters are very easy to remember, but, unfortunately, in the total volume of hieroglyphs, they are an insignificant minority.

Grapheme — a component of a hieroglyph

The rest of the hieroglyphs consist of parts — graphemes. The hieroglyphs are made up of them, as in Tetris, only there are about three hundred shapes instead of seven. It seems like a lot, but you will quickly realize that it is actually quite possible to remember them. You will learn to recognize graphemes as you study the characters. By the way, the role of graphemes is often played by the already familiar pictographic hieroglyphs, so each component has a meaning, which will make it even easier to memorize them.

«Complex» hieroglyphs

Among the more complex hieroglyphs, two large groups can be distinguished.

The first is ideographic hieroglyphs. Don’t be intimidated by complicated names, you don’t have to memorize them. The main thing is to understand the essence, and this is the following: the meaning of ideographic hieroglyphs consists of the meanings of their constituent parts.

The hieroglyph 男 means «man» and consists of two parts: 田 — “field” and 力 — “strength.” The main task of a man in an agrarian society, and this is exactly what ancient China was, is to work in the field, so everything is logical. Such hieroglyphs are very easy to remember. But unfortunately, like pictograms, they are in the minority. Here are some more examples:

- 好 — means “good,” consists of parts 女 — “woman” and 子 — “child”;

- 忘 — means “to forget”, consists of parts 亡 — “to die” and 心 — “heart”;

- 森 — means “forest,” consists of three “trees” — 木.

The second large group of hieroglyphs is the phono-semantic compounds. They make up about 80% of the total number of hieroglyphs. The constituent parts in them are not connected in meaning, and the writing of such a hieroglyph has almost nothing to do with the designated object.

Phonoideograms consist of two parts:

- Phonetic component shows an approximate reading of a hieroglyph. “Approximate,” because it does not reflect the tone, and sometimes there can be more than one reading. For example, in the hieroglyph “mother” 妈 (mā), the phonetic component is 马 (mǎ) — a horse. Have you noticed? In its separate form, its tone is different. All other characters with 马 will also be read as the syllable ma with one tone or another. But the component 斤 (“axe”) can refer to seven readings at once: jin, qin, qi, xin, xi, ting, zhe. Of course, there is not much help from that.

- Radical shows approximately to which range of meanings the hieroglyph belongs. Again, only roughly. Let’s take the already familiar hieroglyph “mother” 妈 (mā). The radical is 女 — “a woman.” Now let’s consider the whole hieroglyph together: it is read as “horse” — 马 (ma) and refers to the range of meanings of “woman” — 女. The result is “mother.” See the logic? Neither do we. But the ancient Chinese did.

Over the centuries, the radical lost more and more function in determining the meaning of the hieroglyph. Now its main task is dictionary navigation. The hieroglyphs in them are divided by radicals. There are 214 radicals in total, and it is better to learn them. Memorizing hieroglyphs from them is much easier, and using a paper dictionary too (if you ever happen to do this).

Traditional and simplified writing

In modern Chinese, writing exists in two versions — traditional and simplified. Traditional is the one that the Chinese have been using for the past two thousand years. And simplified hieroglyphs were introduced in 1956 in China to raise the general level of literacy. In addition to China, simplified hieroglyphs are common in Singapore and Malaysia. The traditional ones, for historical reasons, are still used in Hong Kong and Macau. Therefore, the choice of which hieroglyphs to learn depends on the country you want to visit or live in.

If you learn the traditional hieroglyphs first, it will not always be possible to «automatically» recognize the simplified ones — most will have to be learned from scratch. There are 2236 simplified hieroglyphs in total. For details on how they were simplified, see here.

However, you can also find your reasons for studying traditional hieroglyphs. You will definitely need them if you plan to study Chinese philology, literature, art, and history. In addition, in mainland China, traditional hieroglyphs are considered a sign of intelligence. Modern Chinese hipsters write on WeChat using traditional hieroglyphs.

How to learn Chinese characters

Learn systematically

When you memorize a hieroglyph, learn everything at once: spelling, meaning, and reading with tone. Two out of three won’t work. Without memorizing the tone, you will not be able to reproduce the word correctly in oral speech, and you will not be understood. On the Internet, there are people who do not learn reading, only the meaning and the written form of characters. The utility of such exercises is just incomprehensible. Please don’t.

Start with basic hieroglyphs

Learn pictograms first. They are simple and are part of the rest of the hieroglyphs, so it will be easier to memorize them. Here you will find 20 of the most basic characters. Along the way, it is worth learning the radicals. Usually, they are included in all courses on hieroglyphics (you will find them in the table below).

Use mnemonics

Mnemonic or memorization techniques allow you to create a strong associative connection between the writing of a hieroglyph, its meaning, and reading. As you already know, hieroglyphs are made up of component parts — graphemes. On their basis, you can come up with whole stories.

For example, the hieroglyph 眺 (Zhào) — «look into the distance» consists of parts 目 — “eye” and 兆 — “trillion.” From this, we get some juicy imagery: “a trillion eyes look into the distance.” Of course, not all hieroglyphs can be memorized this way, but at least some of them can.

Learn hieroglyphs together with words

Learn hieroglyphs not separately, but together with the words where they are used. Depending on the word, a hieroglyph can take on different meanings. For example, 会 (huì) means «to know how to,» “to be able to,” “to meet,» and “unification.”

- 社会 (shè huì) — society;

- 不会 (bù huì) — unlikely;

- 会议 (huì yì) — meeting.

To remember better, make sentences from words, see the use of words in context using corpus dictionaries. Learning a word without context is often meaningless. As a result, you will not understand in what situations they are used and how they join other words.

Use cards

It doesn’t have to be paper or cardboard cards. You can install an application to practice. One of the most famous is Anki. It uses the Spaced Repetition System (SRS) to keep you from forgetting a character or word. The first time you repeat the word after a few minutes, then after a few hours, days, and so on. This method of memorization is considered the most effective.

Another popular app is Quizlet flashcards. It does not use a spaced repetition system, but it has a nice design and different game modes for learning. You can try both and decide which one works best for you. Both apps have ready-made sets of words and characters, so you don’t have to create your own.

Write hieroglyphs

Yes, it really helps to better remember hieroglyphs and words. When you write by hand, the fusiform gyrus of the brain is exercised. Because of this, you begin to better reproduce and recognize the symbols. So write, and the more the better.

Drawing Chinese characters is quite a meditative activity, and that is why many people like it. If writing characters becomes a stress reliever, you will again kill two hawks. This makes four already.

Resources

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| digmandarin.com | Basics of Chinese logograms. |

| Anki | An app that uses the spaced repetition system. |

| Quizlet Flashcard | An application with a user-friendly design. |

| Skitter | Application for learning hieroglyphs. They are explained in context with examples. Uses the spaced repetition system. |

| Pleco | Online Dictionary. Audio recordings of the words are available for an additional fee. |

| Tatoeba | Corpus Dictionary. It is convenient to watch the use of words in context. |

| remembr.it. | Application for learning hieroglyphs. Invites you to master 2,194 characters in 90 days. |

| Remembering Simplified Hanzi | One of the most popular hieroglyphic textbooks. The series consists of two books, each with 1500 characters. |

Chinese Textbooks

Learning a foreign language from scratch is very difficult: beginners often do not know where to begin. Textbooks will help to deal with this because the course in them is thought out so that you master the information gradually.

If words and hieroglyphs can be learned using additional resources, in the case of grammar, textbooks will become the main source of information. You need to understand it, otherwise, you will not be able to combine words into phrases and sentences. For a detailed guide on what to learn, look here.

Good textbooks not only provide grammar materials, but also explanations of pinyin, basic pronunciation, and hieroglyphics. Therefore, you can study them from scratch. Just keep a few tips in mind:

- Follow the tutorial program. Do not jump from topic to topic or skip the initial lessons with an explanation of the basics. The curriculum in the textbooks is structured so that the new lessons use material from those already taken. Therefore, if you go straight to an interesting topic about travel, it will be more difficult to join.

- Exercise. Most textbooks come with worksheets. Do not think that they are there just for the extra flavor. Be sure to complete the tasks. You will not learn new information just by reading a lesson.

- Compare several tutorials. Try to study several textbooks at once. They differ not only by covers but also in the style of presentation, assignments, examples, explanations. And not each will suit you equally well.

- Study at a comfortable pace. Don’t rush to learn 10 new topics in a week. If you feel that the information was poorly understood, it is better to repeat what you have done, including the exercises.

- Don’t just study from the textbook. On the thorny path of language learning, a textbook is more of an auxiliary tool. But don’t rely solely on it. Use all available study materials: watch movies, listen to music, read. If you are studying without a teacher, and something is not clear in the textbook, look for explanations in other sources.

Below we have selected four good beginner tutorials.

中文 听说 读写 | Integrated Chinese

One of the most popular Chinese textbooks in the world. In many colleges in the United States, it is used as the main teaching aid in Chinese studies programs. Good for learning the language from scratch.

Pros:

- Good explanation of the basics of phonetics and tones.

- The set includes a workbook for studying pinyin and hieroglyphs.

- The grammar is explained using dialogues as an example.

- Includes materials about the culture of China.

- There are versions with both simplified and traditional writing.

Cons:

- The glossary at the end of chapters does not contain all the new words.

- Words are not always grouped by topic: the word “morning” may appear at the beginning of the textbook, and “evening” — near the end.

- Not all dialogues sound natural.

The book

Developing Chinese: Two-part Beginner Course

This tutorial is recommended by the Chinese Ministry of Education. There are many tasks for speaking practice, so it is especially suitable for group work. The complexity of the texts increases gradually: first, the hieroglyphs are signed with pinyin, then only the tone designations remain, and then they also disappear.

Pros:

- Lots of dialogues from everyday life;

- Large vocabulary volume: 2000-2500 words;

- There are additional books in the series for practicing listening, reading, writing, and speaking;

- Materials about the culture of China;

- Nice and understandable design of the textbook.

Cons:

- In the second part, there are no words and sections on hieroglyphics;

- The set comes with CD, which you most likely have nowhere to insert.

The book

Contemporary Chinese

Recommended by the Confucius Institute. The series consists of three books: a general textbook, a collection of exercises, and a textbook on hieroglyphics.

Pros:

- Many interesting texts about Chinese and China;

- Good design of a textbook on hieroglyphics: all materials are provided with pictures and explanations;

- Vocabulary topics are not limited to student life, as is often the case.

Cons:

- Hieroglyphs and compound words are used from the very beginning;

- Explanations of phonetics are very brief, additional materials will be needed;

- There are no hieroglyph-related assignments. You’ll need to buy a separate tutorial

The book

Road to Success

The textbook is well suited for slowly starting to learn: you will not be getting large amounts of information, all the explanations are very accommodative and include pictures. If you’re afraid of getting overwhelmed, try this tutorial.

Pros:

- Only the most basic information — 100 first words and 50 hieroglyphs;

- Study texts and assignments are written in Pinyin with explanations in English;

- Simple dialogues;

- Most of the textbook is devoted to phonetics.

Cons:

- There is no grammar at all;

- For quick progress, it is better to choose a different tutorial.

The book

Additional Resources

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Chinese Grammar Wiki | Online reference for all levels. |

| LTL Mandarin School | Sentence structure and word order reference. |

| ICL | Online grammar guide for all levels. Audio lessons available. |

| Ninchinese | Online Grammar Reference. Some tasks are accompanied by games. There is a blog with articles about the Chinese language. |

| HiNative | On this site, you can ask a question on a topic you struggle with to a native speaker. Usually, the answers come within a few minutes. |

What to read in Chinese

If you want to learn a foreign language, be sure to read, and as much as possible. Most of the materials are available online, many are free. In addition, reading will help you with several things:

- Expand vocabulary. Moreover, you will learn not only new words but also better memorize the old ones. In the text, you will see how words work in a sentence, and this will help you better understand them. As you study the words, after each new topic, read the text using the vocabulary you’ve learned.

- Learn grammar. Like words, grammar should be taught by example. Reading different texts, you get used to varied structures and styles.

- Learn new things about the culture. Thanks to reading, you will gain a lot of new knowledge not only about the language but also about the people who speak it. Interest in culture raises motivation, and language learning, in general, gets easier.

Pinyin texts

You can read at a very basic level, even before you start learning hieroglyphs. For this, there are pinyin texts. Most often, these will be children’s books, so they have a limited range of topics and vocabulary. You can also read classic European fairy tales in Chinese, for example, Snow White.

Pinyin texts are also a good way to practice your tones. Just be sure to read aloud. If in doubt, check how the word sounds in the dictionary.

Adapted Texts

Once you have mastered the basic hieroglyphs, move on to using them. The best place to start is with adapted texts. In them, words match the reader’s level, and if necessary, there are also readings of hieroglyphs in pinyin. You can find such texts in both printed and electronic forms.

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| New Practical Chinese Reader | A series of textbooks with texts for reading |

| Graded Chinese Reader | A series of books with adapted stories for all levels |

| Du Chinese | The resource is available as an application on the phone. Materials are selected according to the level of difficulty, you can add undertexts in pinyin, there is a built-in dictionary. The texts in the app are available in audio format — they are all read by native speakers. You can even tweak the playback speed. |

Newspapers

The unadapted press is designed for a higher level, but don’t be afraid. At B1, you can already partially understand it. Here are five tips to help you overcome the fear of newspapers:

- Start with the headlines. Try to disassemble large characters, and check the dictionary for unfamiliar ones;

- Read your favorite sections. Sports, culture, news, travel — it doesn’t matter what. The main part is that you like it;

- Concentrate on words, not sentences. You can count how many words in a paragraph you understand. Pay attention to what is next to them. Then look in the dictionary for the rest of the words and try to understand the meaning of the section. Over time, the percentage of unfamiliar vocabulary will become gradually smaller;

- See translation of articles. Most major newspapers have an English version of their website. Some materials will be presented in two languages at once. It is convenient to use them to check if you have understood everything correctly.

- Do not hurry. You won’t be able to learn to read newspaper articles overnight. Give yourself time. If at first, it doesn’t work out — that’s okay. Keep practicing, expanding your vocabulary, and you will soon see progress.

| Newspaper | Description |

|---|---|

| 中国 日 报告 | China Daily | The most famous newspaper in China. Designed mainly for foreigners. There are versions of the site in different languages. |

| 人民日报 | People’s Daily | Official publication of the government. Covers issues of politics and international relations. |

| 环球 时报 | Global Times | This periodic is also about politics. Unlike other newspapers, the articles in English here are not just translations, but exclusive materials. Therefore, it will not work for self-testing. |

| 世界 日报 | World Journal A | Chinese newspaper published in New York. Its target audience is Chinese immigrants. |

| 光明 日报 | Guangming Daily | Dedicated to science, technology, culture, and education. The site has an English version. |

| 经济 观察 报 | Economic Observer The | The main topics of the newspaper are economics and market news. |

| 中国 青年 报 | China Youth Daily | The publication is aimed at students and young professionals. Topics include not only news and politics, but also culture, art, travel, relationships. |

Fiction

China is famous for its long literary tradition. Classical Chinese novels — «Romance of the Three Kingdoms,» “Water Margin,” “Journey to the West,” “Dream of the Red Chamber” were written in the XIV-XVIII centuries. Therefore, it is rather difficult to read them even at a high level of language proficiency. But there are also more modern books that are better suited for language learning. For example, works by authors such as Gao Xingjian (高行健), Ma Jian (馬 建), Yu Hua (余華), Zhu Wen (朱 文), Wang Anyi (王安忆). However, it is difficult to read fiction unadapted. This way of acquiring the language will become available when you reach the B2-C1 level.

What to listen to and watch in Chinese

Because of the many similar words, difficult tones, and dialects, listening becomes the most difficult part of the language for many. But you shouldn’t worry. Listening to speech is the same skill as any, it can also be trained. And you don’t even have to be Chinese for that.

Podcasts

Podcasts are a great language learning tool. Thanks to them, you will learn to comprehend Chinese speech, enrich your vocabulary, and just learn a lot of interesting things. Podcasts exist for all levels, many come with printed scripts of the episodes. Such podcasts are especially good for pronunciation practice: read the text aloud along with the speaker, copying all intonations. When choosing podcasts, remember a few simple rules:

- Choose a podcast according to your level — usually, the podcast level is indicated in the title of the episode or description;

- The podcast should not contain a lot of slang and dialecticisms — this rule is especially true for beginners. First of all, master the literary norm, which you can use in all situations, and only then move on to slang;

- Choose a speaker with standard pronunciation — each dialect, of which there are several hundred in China, has its own pronunciation characteristics. Unless you specifically seek to speak with a Cantonese or Taiwanese accent, choose the generally accepted Beijing version;

- Look for podcasts with a script — they are better suited for studying. You can check yourself and write out unfamiliar words with the script,

| Podcast | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese Pod | A1-C1 A | A resource for all-encompassing language learning. Lessons are in audio and video format, so you can listen to them like podcasts. Basic subscription costs 14 USD, advanced — 29 USD per month. |

| 青春 愛 消遣 (qīngchūn ài xiāoqiǎn) — The Pastimes of Youth | A1-B1 | A podcast about everyday life in Taiwan. Perfect if you want to immerse yourself in the culture of this island. The presenters’ communication style is not very formal, homelike cozy. |

| MandarinBean | A1-C1 | The podcast is well suited for learning new vocabulary. Topics are varied, for all levels of language proficiency. |

| 狗熊 有话说 (gǒuxióng yǒu huàshuō) — BearTalk | B1-C1 | Quite a well-known podcast dedicated to technology, books, and self-development. Useful for learning informal speech. |

| 听 故事 学 中文 (tīng gùshì xué zhōngwén) — Learning Chinese through Stories | B1-C1 | Each podcast episode is a separate story, from 2 to 20 minutes long. More suitable for those who are already fluent in the language. Audio recordings are provided with a text transcript. |

| 鬼話連篇 (guǐhuà liánpiān) — A Big Load of Paranormal Events | B1-C1 | Not a podcast, but a YouTube channel dedicated to the paranormal. The hosts visit abandoned houses rumored to be haunted. So if you enjoy The Twilight Zone, follow the link. All videos are subtitled, so they are suitable for intermediate language proficiency. |

| too 慢速 中文 (màn sù zhōngwén) — Slow Chinese | B2-C1 | A podcast about student life in China. The vocabulary can be difficult, but the speed of speech is slow. It will be especially useful if you are going to study in China. |

Songs

Songs will not only help you in learning the language but also bring you closer to native speakers. The lyrics can be translated as an exercise (which can be very interesting, by the way). Here are three more reasons why you should try listening to Chinese music:

- Songs get stuck. A good melody and beautiful vocals are enough for the song to stick with you for a long time, even if you don’t understand the meaning. As you listen over and over again, you will gradually begin to understand the words that will nest in your head as firmly as the melody.

- The songs will teach you useful vocabulary. Modern pop music often uses fairly simple expressions that will be useful in everyday life. Some songs can even teach you slang. But you have to be careful with it — it becomes outdated very quickly.

- Chinese pop music is really good. Even if you don’t find the phonetics of Chinese very pleasant, you will probably like the songs. In them, the beauty of the sound of the Chinese language is revealed to the fullest.

TV

TV shows can make learning a language more fun. But if you want them to be of some use, viewing alone will not be enough. TV shows need to be turned into study material. How to do it?

- Watch with Chinese subtitles. To learn to perceive speech without translation, the subtitles must be exactly Chinese. You can find original shows on streaming platforms like Netflix.

- Write out unfamiliar words. You can set the bar for each activity: 10, 20, 30 new words, or more if memory allows. At the same time, choose the most useful ones, especially at the initial levels. Write them down in a notebook or add to a flashcard app, and don’t forget to repeat. This way you can seriously improve your vocabulary.

- Repeat after the actors. Having become familiar with the sound of a word, you will remember it even better and at the same time practice pronunciation.

- Don’t forget to rest. Watch TV shows for fun, and not just as an assignment. Don’t turn entertainment into hard labor.

Need to learn a language?

There are four main options for where to learn Chinese:

- Group lessons in a language school;

- Individual lessons with a tutor;

- Language courses abroad;

- Self-study.

We wrote in detail about the advantages and disadvantages of each method here.

Sites for finding a tutor in the Chinese language

| Resource | Specificities |

|---|---|

| Preply | A platform for finding native speakers-tutors |

| italki | A platform for finding native speakers-tutors |

Chinese language courses abroad

| City | Cost of Standard Coursesone week, living expenses not accounted for | Cost of Intensive Coursesone week, living expenses not accounted for |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 283 USD | 340 USD |

| Shanghai | 188 USD | 300 USD |

| Guangzhou | 263 USD | 500 USD |

| Shenzhen | 283 USD | 833 USD |

| Kunming | 288 USD | 674 USD |

Resources for self-studying Chinese

| Resource | Specificities |

|---|---|

| Duolingo | Gamified language learning. |

| Memrise | Suitable for learning basic words and expressions. |

| LingQ | A resource for learning languages. The assignments and materials cover different aspects: hieroglyphs, reading, listening. |

| Chinese Pod | A resource for learning Chinese. Lessons are available in audio and video formats. Basic subscription costs 14 USD, advanced — 29 USD per month. |

| Yabla Chinese | Resource for learning Chinese using video and audio supplements. |

| Hacking Chinese | Blog with articles and podcasts about Chinese. The materials cover all aspects of the language: vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation. |

Why learn Chinese?

The Chinese language is the first by the number of native speakers in the world. In total, 1.3 billion people speak all dialects. At the same time, due to the growing economy, the demand for the Chinese language is only increasing: it is studied by at least 25 million people. Why are they doing that?

Chinese for study

The first reason is education in China. Due to its low price and prestige, it is becoming more and more popular. On average, higher education costs 3,000-5,000 USD per year. About 30% of programs are in English, but in terms of employment, studying in Chinese will be more promising. At universities, there are preparatory programs in which you can improve your language skills to the level required for admission — usually HSK 4 or 5. Such programs cost 2,500 USD and above. Living expenses in China are quite low — 400 USD is enough for a month. And even these costs can be reduced with scholarships offered by the government and educational institutions.

In total, there are more than 2,000 universities in China, and some of them are considered very prestigious. The QS World Ranking has included six Chinese universities in the top 100[1]. Only the US and the UK are represented by more institutions on that list. Graduates of these universities will be able to find work in any country.

Chinese for work

The most popular professions in China are engineers, IT specialists, sales and tourism specialists. The unemployment rate is quite low — 3.7%. For comparison, in the USA it is 4.5%[2]. That said, even programmers and engineers need to know the language for a career in China. Companies rarely put non-Chinese speaking employees in leadership positions.

Another popular profession among foreigners is teaching English. According to Chinese law, you can legally work as an English teacher only if you are a native speaker or have a special international certificate. But the market demand is so high that out of 400,000 foreigners, ⅔ work illegally[3]. The average salary is 2,912 USD per month, but with legal employment, the amount will be higher.

The Chinese language is also useful for a career in other countries — it is one of the most demanded second languages in the business world.

Chinese for immigration

If you are planning to live in China, you will have a hard time without knowing the language. Only 1% of Chinese speak English[4], so basic knowledge of Chinese is essential for survival. To obtain citizenship, you must have lived in the country for at least 10 years. Additionally, one of the conditions is knowledge of the Chinese language.

Keep in mind that China is by no means Heaven on Earth, and life there is not for everyone. Before thinking about moving, research the experiences of different people. Perhaps it will influence your opinion.

The Chinese language for travel

China is a huge and very diverse country, where attractions for every taste can be found. There are modern megacities, picturesque villages, and famous natural parks. In Zhangjiajie, for example, the famous «floating mountains» from Avatar were filmed.

At the same time, basic knowledge of the language will greatly improve your stay in China. Without it, even finding a pharmacy on the street will be difficult — after all, all the signs are in hieroglyphs. And knowing how to talk, you can step away from the guide and get closer to the locals, immersing yourself in the real culture of China.

Find language courses

The Chinese language exams

HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) exam is the most common Chinese proficiency test. It consists of two parts — written and oral. You can take them separately. The written exam is divided into six levels, HSK 1 is the lowest, HSK 6 is the highest. HSK 6 roughly corresponds to C1 level on the European scale CEFR. The oral part of the exam is divided into three levels of difficulty. To enter the university, it is enough to pass the second. The exam is held several times a year, and the cost usually does not exceed 18 USD.

Proof of proficiency in Chinese is required if you want to:

- Study in China. When applying for a Bachelor’s degree, you will need a level 4-5 certificate, for a master’s program — levels 5-6. If you plan to study in China in English, you do not need to take HSK.

- Work in China. High-paying executive positions accept candidates with HSK 5-6 levels. You will also need a Level 3 Oral Exam Certificate.

More details

WikipediaRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

Chinese language

Chinese (中文; Zhōngwén, especially when referring to written Chinese) is a group of languages spoken natively by the ethnic Han Chinese majority and many minority ethnic groups in Greater China. About 1.3 billion people (or approximately 16% of the world’s population) speak a variety of Chinese as their first language.Chinese languages form the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages family. The spoken varieties of Chinese are usually considered by native speakers to be variants of a single language. However, their lack of mutual intelligibility means they are sometimes considered separate languages in a family. Investigation of the historical relationships among the varieties of Chinese is ongoing. Currently, most classifications posit 7 to 13 main regional groups based on phonetic developments from Middle Chinese, of which the most spoken by far is Mandarin (with about 800 million speakers, or 66%), followed by Min (75 million, e.g. Southern Min), Wu (74 million, e.g. Shanghainese), and Yue (68 million, e.g. Cantonese). These branches are unintelligible to each other, and many of their subgroups are unintelligible with the other varieties within the same branch (e.g. Southern Min). There are, however, transitional areas where varieties from different branches share enough features for some limited intelligibility, including New Xiang with Southwest Mandarin, Xuanzhou Wu with Lower Yangtze Mandarin, Jin with Central Plains Mandarin and certain divergent dialects of Hakka with Gan (though these are unintelligible with mainstream Hakka). All varieties of Chinese are tonal to at least some degree, and are largely analytic.

The earliest Chinese written records are Shang dynasty-era oracle bone inscriptions, which can be dated to 1250 BCE. The phonetic categories of Old Chinese can be reconstructed from the rhymes of ancient poetry. During the Northern and Southern dynasties period, Middle Chinese went through several sound changes and split into several varieties following prolonged geographic and political separation. Qieyun, a rime dictionary, recorded a compromise between the pronunciations of different regions. The royal courts of the Ming and early Qing dynasties operated using a koiné language (Guanhua) based on Nanjing dialect of Lower Yangtze Mandarin.

Standard Chinese (Standard Mandarin), based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin, was adopted in the 1930s and is now an official language of both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan), one of the four official languages of Singapore, and one of the six official languages of the United Nations. The written form, using the logograms known as Chinese characters, is shared by literate speakers of mutually unintelligible dialects. Since the 1950s, simplified Chinese characters have been promoted for use by the government of the People’s Republic of China, while Singapore officially adopted simplified characters in 1976. Traditional characters remain in use in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and other countries with significant overseas Chinese speaking communities such as Malaysia (which although adopted simplified characters as the de facto standard in the 1980s, traditional characters still remain in widespread use).

FreebaseRate this definition:0.0 / 0 votes

-

Chinese language

Chinese is a group of related language varieties, several of which are not mutually intelligible, and is variously described as a language or language family. Originally the indigenous speech of the Han majority in China, Chinese forms one of the branches of the Sino-Tibetan language family. About one-fifth of the world’s population, or over one billion people, speaks some form of Chinese as their native language.

Varieties of Chinese are usually perceived by native speakers as dialects of a single Chinese language, rather than separate languages, although this identification is considered inappropriate by some linguists and sinologists. The internal diversity of Chinese has been likened to that of the Romance languages, although all varieties of Chinese are tonal and analytic. There are between 7 and 13 main regional groups of Chinese, of which the most spoken, by far, is Mandarin, followed by Wu, Yue and Min. Most of these groups are mutually unintelligible, although some, like Xiang and the Southwest Mandarin dialects, may share common terms and some degree of intelligibility.

How to pronounce chinese language?

How to say chinese language in sign language?

Numerology

-

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of chinese language in Chaldean Numerology is: 9

-

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of chinese language in Pythagorean Numerology is: 5

Translation

Find a translation for the chinese language definition in other languages:

Select another language:

- — Select —

- 简体中文 (Chinese — Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese — Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a FREE new word definition delivered to your inbox daily?

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:

Are we missing a good definition for chinese language? Don’t keep it to yourself…

- Standard Chinese is the official language in mainland China, as well as in Taiwan, and is also known as Standard Mandarin or Modern Standard Mandarin.

- Wu Chinese is a dialect of Chinese that is predominantly spoken in the eastern region of China. The language exists in six main subgroups, which are geographically defined.

- English is one of the most critical foreign languages in China, with about 10 million speakers all over the country. The majority of English speakers are found in the urban centers of the country.

- Chinese Sign Language is the primary sign language used among the deaf population in mainland China and Taiwan and is used by a significant percentage of the estimated 20 million deaf people in China.

China is home to 56 ethnic groups, all of whom have played a critical role in the development of the various languages spoken in China. Linguists believe that there are 297 living languages in China today. These languages are geographically defined, and are found in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Tibet. Mandarin Chinese is the most popular language in China, with over 955 million speakers out of China’s total population of 1.21 billion people.

National Language of China: Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese is the official language in mainland China, as well as in Taiwan, and is also known as Standard Mandarin or Modern Standard Mandarin. The language is a standardized dialect of Mandarin language, but features aspects of other dialects in its usage, including written vernacular Chinese in the language’s grammar, Mandarin dialects in its vocabulary, and the Beijing dialect in the pronunciation of its words. In mainland China, Standard Chinese is also known as Putonghua (loosely translating to “common speech”), while in Taiwan the language is referred to as Guoyu, which loosely translates to “national language.» The use of Standard Chinese in mainland China is regulated by the National Language Regulating Committee, while the National Languages Committee is mandated to regulate the language’s use in Taiwan. The law provides Standard Chinese as the lingua franca in China and is used as a means of communication, enabling speakers of unintelligible varieties of Chinese languages. Mainland China has a law titled the “National Common Language and Writing Law,” whose provisions call for the mandatory promotion of Standard Chinese by the Chinese government. Records from China’s Ministry of Education show that about 70% of the population in mainland China can speak Standard Chinese, but only 10% can speak the language fluently. Standard Chinese is incorporated into the education curriculum in both mainland China as well as in Taiwan, with the government aiming to have the language achieve a penetration of at least 80% across the country by 2020. In its written format, Standard Chinese uses both simplified Chinese characters (used mainly in Putonghua), as well as traditional Chinese characters (used primarily in Guoyu). For the braille system, the language uses Taiwanese Braille, Mainland Chinese Braille, and Two-Cell Chinese Braille.

Official Languages of China

Another language that has official status in China is Cantonese. The origin of the language can be traced to the port city of Guangzhou, from where its use spread throughout the Pearl River Delta. Guangzhou is also known as Canton, and it is from this city that the language got its name. Cantonese is used as the official language in Hong Kong, as provided for by the Hong Kong Basic Law, and is utilized in all government communication, including court and tribunal proceedings. Cantonese is also the official language in Macau, along with Portuguese. The use of Cantonese in Hong Kong is regulated by the Official Language Division of the Civil Service Bureau, a government institution. In Macau, the use of the language is regulated by the Public Administration and Civil Service Bureau. According to linguists, Cantonese is defined as a variant of the Chinese language or as a prestige variant of Yue, a subdivision of Chinese. When classified with other closely related Yuehai dialects, Cantonese has about 80 million speakers across the country. In the Guangzhou province, Cantonese is used as the lingua franca as well as in the neighboring region of Guangxi. Cantonese can be divided into three main dialects: the Guangzhou dialect, Hong Kong dialect, and Macau dialect. All of these dialects are geographically defined. Written Cantonese uses traditional Chinese characters, as well as characters from written vernacular Chinese. Blind Cantonese speakers use the Cantonese braille system.

Regional Languages of China

Wu Chinese is a dialect of Chinese that is predominantly spoken in the eastern region of China. The language exists in six main subgroups, which are geographically defined. These subgroups include Taihu, Taizhou, Oujiang, Wuzhou, Chu-Qu, and Xuanzhou. The language can also be divided into 14 varieties, which include the Shanghainese, Huzhou, Wuxi, Ningbo, Suzhou, Changzhou, Jiaxing, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, Xuanzhou, Chuqu, Taizhou, Wuzhou, and Oujiang dialects. The total number of Wu speakers in China is estimated to be about 80 million people. Fuzhou is a dialect of Houguan Chinese subgroup and a prestige variety of the Eastern Min branch of the Chinese language. The dialect is classified as one of the major regional languages in China and has speakers predominantly located in the Fujian province. The dialect is centered in the city of Fuzhou, from which the dialect gets its name. The total number of Fuzhou speakers is estimated to be over 10 million all over the country.

The Hokkien dialect is another major regional language in China. The language is a dialect of the Southern Min language group. The dialect originated from the Fujian province and spread to different regions in southeastern China. Today, the total number of Hokkien dialect speakers is estimated to be about 37 million people. In Taiwan, Hokkien is one of the statutory languages used for the signage in public transportation. The Hokkien dialect is divided into ten dialects, which include Medan, Penang, Taiwanese, Zhangzhou, Quanzhou, Xiamen, and Singaporean. Other regional languages include Hakka, Xiang, Foochow, and Gan.

Foreign Languages Spoken in China

English is one of the most critical foreign languages in China, with about 10 million speakers all over the country. The majority of English speakers are found in the urban centers of the country. In Hong Kong, English is established as an official language and is used in both print and electronic media. English is also used as a lingua franca in China during international engagements. Another major international language in China is Portuguese, which is used as the official language in Macau.

Sign Language in China

Chinese Sign Language is the primary sign language used among the deaf population in mainland China and Taiwan and is used by a significant percentage of the estimated 20 million deaf people in China. Tibetan Sign Language is used by the deaf residents of Tibet, and particularly in the Lhasa region. Tibetan Sign Language exists as a standardized language, which was formulated between 2001 and 2004. In the past, the use of sign Language in China was discouraged and in some cases completely banned as people believed that it would further inhibit a child’s auditory capabilities.

Overview of Languages Spoken in China

| Rank | Languages in China |

|---|---|

| 1 | Standard Chinese (Mandarin) |

| 2 | Yue (Cantonese) |

| 3 | Wu (Shanghainese) |

| 4 | Minbei (Fuzhou) |

| 5 | Minnan (Hokkien-Taiwanese) |

| 6 | Xiang |

| 7 | Gan |

| 8 | Hakka |

| 9 | Zhuang |

| 10 | Mongolian |

| 11 | Uighur |

| 12 | Krygyz |

| 13 | Tibetan |

- Home

-

Society

- What Languages Are Spoken in China?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Languages of China | |

|---|---|

Historical distribution map of linguistic groups in Greater China |

|

| Official | Standard Mandarin

Cantonese (Hong Kong and Macau) Portuguese (Macau) English (Hong Kong) Mongolian (Inner Mongolia, Haixi in Qinghai, Bayingolin and Bortala in Xinjiang) Korean (Yanbian in Jilin) Tibetan (Tibet, Qinghai) Uyghur (Xinjiang) Zhuang (Guangxi, Wenshan in Yunnan) Kazakh (Ili in Xinjiang) Yi (Liangshan in Sichuan, Chuxiong and Honghe in Yunnan) |

| National | Standard Mandarin |

| Indigenous | Achang

Ai-Cham Akha Amis Atayal Ayi Äynu Babuza Bai Baima Basay Blang Bonan Bunun Buyang Buyei Daur De’ang Dong Dongxiang E, Chinese Pidgin English Ersu Evenki Fuyü Gïrgïs Gelao Groma Hani Hlai Hmong Ili Turki Iu Mien Jingpho Jino Jurchen Kanakanavu Kangjia Kavalan Kim Mun Khitan Korean Lahu Lisu Lop Macanese Manchu Miao Maonan Mongolian Monguor Monpa Mulam Nanai Naxi Paiwan Pazeh Puyuma Ong-Be Oroqen Qabiao Qoqmončaq Northern Qiang Southern Qiang, Prinmi Rukai Russian Saaroa Saisiyat Salar Sarikoli Seediq She Siraya Sui Tai Dam Tai Lü Tai Nüa Tao Tangut Thao Amdo Tibetan Central Tibetan (Standard Tibetan) Khams Tibetan Tsat Tsou Tujia Uyghur Waxianghua Wutun Xibe Yi Eastern Yugur Western Yugur Zhaba Zhuang |

| Regional | Cantonese (Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau)

Hokkien (Fujian) Shanghainese (Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang) Hunanese (Hunan) Jiangxinese (Jiangxi) Hakka (Fujian and Guangdong) Portuguese (Macau) English (Hong Kong) Mongolian (Inner Mongolia, Haixi in Qinghai, Bayingolin and Bortala in Xinjiang) Korean Tibetan (Tibet, Qinghai) Central Tibetan (U-Tsang) Amdo Tibetan (Amdo) Khams Tibetan (Khams) Uyghur (Xinjiang) Zhuang (Guangxi, Wenshan in Yunnan) Kazakh (Ili in Xinjiang) Yi (Liangshan in Sichuan, Chuxiong and Honghe in Yunnan) Hong Kong Sign (Hong Kong and Macau) Tibetan Sign (Tibet) |

| Minority | Kazakh

Korean Kyrgyz Russian Tatar Tuvan Uzbek Wakhi Vietnamese |

| Foreign | English[1][2]

Portuguese French[3] German Russian Japanese[4] |

| Signed | Chinese Sign

Hong Kong Sign Tibetan Sign |

| Keyboard layout |

Chinese input methods |

There are several hundred languages in China. The predominant language is Standard Chinese, which is based on central Mandarin, but there are hundreds of related Chinese languages, collectively known as Hanyu (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ, ‘Han language’), that are spoken by 92% of the population. The Chinese (or ‘Sinitic’) languages are typically divided into seven major language groups, and their study is a distinct academic discipline.[5] They differ as much from each other morphologically and phonetically as do English, German and Danish, but meanwhile share the same writing system (Hanzi) and are mutually intelligible in written form. There are in addition approximately 300 minority languages spoken by the remaining 8% of the population of China.[6] The ones with greatest state support are Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang.

According to the 2010 edition of Nationalencyklopedin, 955 million out of China’s then-population of 1.34 billion spoke some variety of Mandarin Chinese as their first language, accounting for 71% of the country’s population.[7] According to the 2019 edition of Ethnologue, 904 million people in China spoke some variety of Mandarin as their first language in 2017.[8]

Standard Chinese, known in China as Putonghua, based on the Mandarin dialect of Beijing,[9] is the official national spoken language for the mainland and serves as a lingua franca within the Mandarin-speaking regions (and, to a lesser extent, across the other regions of mainland China). Several other autonomous regions have additional official languages. For example, Tibetan has official status within the Tibet Autonomous Region and Mongolian has official status within Inner Mongolia. Language laws of China do not apply to either Hong Kong or Macau, which have different official languages (Cantonese, English and Portuguese) from the mainland.

Spoken languages[edit]

The spoken languages of nationalities that are a part of the People’s Republic of China belong to at least nine families:

Ethnolinguistic map of China

- The Sino-Tibetan family: 19 official ethnicities (including the Han and Tibetans)

- The Tai–Kadai family: several languages spoken by the Zhuang, the Bouyei, the Dai, the Dong, and the Hlai (Li people). 9 official ethnicities.

- The Hmong–Mien family: 3 official ethnicities

- The Austroasiatic family: 4 official ethnicities (the De’ang, Blang, Gin (Vietnamese), and Wa)

- The Turkic family: Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Salars, etc. 7 official ethnicities.[10]

- The Mongolic family: Mongols, Dongxiang, and related groups. 6 official ethnicities.[10]

- The Tungusic family: Manchus (formerly), Hezhe, etc. 5 official ethnicities.

- The Koreanic family: Korean language

- The Indo-European family: 2 official ethnicities, the Russians and Tajiks (actually Pamiri people). There is also a heavily Persian-influenced Äynu language spoken by the Äynu people in southwestern Xinjiang who are officially considered Uyghurs.

- The Austronesian family: 1 official ethnicity (the Gaoshan, who speak many languages of the Formosan branch), 1 unofficial (the Utsuls, who speak the Tsat language but are considered Hui.)

Below are lists of ethnic groups in China by linguistic classification. Ethnicities not on the official PRC list of 56 ethnic groups are italicized. Respective Pinyin transliterations and Chinese characters (both simplified and traditional) are also given.

Sino-Tibetan[edit]

- Sinitic

- Chinese, 汉语, 漢語

- Mandarin Chinese, 官话, 官話

- Beijing Mandarin, 北京官话, 北京官話

- Standard Chinese, 普通话, 普通話

- Singaporean Mandarin, 新加坡华语, 新加坡華語

- Malaysian Mandarin, 马来西亚华语, 馬來西亞華語

- Taiwanese Mandarin, 台湾华语, 臺灣華語

- Taipei Mandarin, 台北腔/国语, 臺北腔/國語

- Northeastern Mandarin, 东北官话, 東北官話

- Jilu Mandarin, 冀鲁官话, 冀魯官話

- Jiaoliao Mandarin, 胶辽官话, 膠遼官話

- Zhongyuan Mandarin, 中原官话, 中原官話

- Lanyin Mandarin, 兰银官话, 蘭銀官話

- Lower Yangtze Mandarin, 江淮官话, 江淮官話

- Southwestern Mandarin, 西南官话, 西南官話

- Beijing Mandarin, 北京官话, 北京官話

- Jin Chinese, 晋语, 晉語

- Wu Chinese, 吴语, 吳語

- Shanghainese, 上海话, 上海話

- Huizhou Chinese, 徽语, 徽語

- Yue Chinese, 粤语, 粤語

- Cantonese, 广东话, 廣東話

- Ping Chinese, 平话, 平話

- Gan Chinese, 赣语, 贛語

- Xiang Chinese, 湘语, 湘語

- Hakka language, 客家话, 客家話

- Min Chinese, 闽语, 閩語

- Southern Min, 闽南语, 閩南語

- Hokkien, 泉漳话, 泉漳話

- Teochew dialect, 潮州话, 潮州話

- Eastern Min, 闽东语, 閩東語

- Pu-Xian Min, 莆仙话, 莆仙話

- Leizhou Min, 雷州话, 雷州話

- Hainanese, 海南话, 海南話

- Northern Min, 闽北语, 閩北語

- Central Min, 闽中语, 閩中語

- Shao-Jiang Min, 邵将语, 邵將語

- Southern Min, 闽南语, 閩南語

- Mandarin Chinese, 官话, 官話

- Chinese, 汉语, 漢語

- Bai, 白語

- Dali language, 大理語

- Dali dialect(Bai: Darl lit)

- Xiangyun dialect

- Yitdut language/Jianchuan language, 剑川语, 劍川語

- Yitdut dialect(Bai: Yit dut)

- Heqing dialect(Bai: hhop kait)

- Bijiang language

- Bijiang dialect

- Lanping dialect(Bai: ket dant)

- Dali language, 大理語

- Tibeto-Burman

- Tujia

- Qiangic

- Qiang

- Northern Qiang

- Southern Qiang

- Prinmi

- Baima

- Tangut

- Qiang

- Bodish

- Tibetan

- Central Tibetan (Standard Tibetan)

- Amdo Tibetan

- Khams Tibetan

- Lhoba

- Monpa/Monba

- Tibetan

- Lolo–Burmese–Naxi

- Burmish

- Achang

- Loloish

- Yi

- Lisu

- Lahu

- Hani

- Jino

- Nakhi/Naxi

- Burmish

- Jingpho–Nungish–Luish

- Jingpho

- Derung

- Nu

- Nusu

- Rouruo

Kra–Dai[edit]

(Possibly the ancient Bǎiyuè 百越)

- Be

- Kra

- Gelao

- Kam–Sui

- Dong

- Sui

- Maonan

- Mulao/Mulam

- Hlai/Li

- Tai

- Zhuang (Vahcuengh)

- Northern Zhuang

- Southern Zhuang

- Bouyei

- Dai

- Tai Lü language

- Tai Nüa language

- Tai Dam language

- Tai Ya language

- Tai Hongjin language

- Zhuang (Vahcuengh)

Turkic[edit]

- Karluk

- Ili Turki

- Uyghur

- Uzbek

- Kipchak

- Kazakh

- Kyrgyz

- Tatar

- Oghuz

- Salar

- Siberian

- Äynu

- Fuyu Kyrgyz

- Western Yugur

- Tuvan

- Old Uyghur (extinct)

- Old Turkic (extinct)

Mongolic[edit]

- Mongolian

- Oirat

- Torgut Oirat

- Buryat

- Daur

- Southeastern

- Monguor

- Eastern Yugur

- Dongxiang

- Bonan

- Kangjia

- Monguor

- Tuoba (extinct)

- Para-Mongolic

- Khitan (extinct)

- Tuyuhun (extinct)

Tungusic[edit]

- Southern

- Manchu

- Jurchen

- Xibe

- Nanai/Hezhen

- Manchu

- Northern

- Evenki

- Oroqen

Korean[edit]

- Korean

Hmong–Mien[edit]

(Possibly the ancient Nánmán 南蛮, 南蠻)

- Hmong

- Mien

- She

Austroasiatic[edit]

- Palaung-Wa

- Palaung/Blang

- De’ang

- Wa/Va

- Vietnamese/Kinh

Austronesian[edit]

- Formosan languages

- Tsat

Indo-European[edit]

- Russian

- Tocharian (extinct)

- Saka (extinct)

- Pamiri, (mislabelled as «Tajik»)

- Sarikoli

- Wakhi

- Portuguese (spoken in Macau)

- English (spoken in Hong Kong)

Yeniseian[edit]

- Jie (Kjet) (extinct) (?)

Unclassified[edit]

- Ruan-ruan (Rouran) (extinct)

Mixed[edit]

- Wutun (Mongolian-Tibetan mixed language)

- Macanese (Portuguese creole)

Written languages[edit]

The first page of the astronomy section of the 御製五體清文鑑 Yuzhi Wuti Qing Wenjian. The work contains four terms on each of its pages, arranged in the order of Manchu, Tibetan, Mongolian, Chagatai, and Chinese languages. For the Tibetan, it includes both transliteration and a transcription into the Manchu alphabet. For the Chagatai, it includes a line of transcription into the Manchu alphabet.

The following languages traditionally had written forms that do not involve Chinese characters (hanzi):

- The Dai people

- Tai Lü language – Tai Lü alphabet

- Tai Nüa language – Tai Nüa alphabet

- The Daur people — Daur language — Manchu alphabet

- The Hmong people — Hmongic languages — Hmong writing(Pollard script, Pahawh Hmong, Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong, etc.)

- The Kazakhs – Kazakh language – Kazakh alphabets

- The Koreans – Korean language – Chosŏn’gŭl alphabet

- The Kyrgyz – Kyrgyz language – Kyrgyz alphabets

- The Lisu people — Lisu language — Lisu script

- The Manchus – Manchu language – Manchu alphabet

- The Mongols – Mongolian language – Mongolian alphabet

- The Naxi – Naxi language – Dongba characters

- The Qiang people — Qiang language or Rrmea language — Rma script

- The Santa people (Dongxiangs in Chinese) — Santa language — Arabic script

- The Sui – Sui language – Sui script

- The Tibetans – Tibetan language – Tibetan alphabet

- The Uyghurs – Uyghur language – Uyghur Arabic alphabet

- The Xibe – Xibe language – Manchu alphabet

- The Yi – Yi language – Yi syllabary

Many modern forms of spoken Chinese languages have their own distinct writing system using Chinese characters that contain colloquial variants.

These typically are used as sound characters to help determine the pronunciation of the sentence within that language:

- Written Sichuanese — Sichuanese

- Written Cantonese — Cantonese

- Written Shanghainese — Shanghainese

- Written Hakka — Hakka

- Written Hokkien — Hokkien

- Written Teochew — Teochew

Some non-Sinitic peoples have historically used Chinese characters:

- The Koreans – Korean language – Hanja

- The Vietnamese — Vietnamese language — Chữ nôm

- The Zhuang (Tai people) – Zhuang languages – Sawndip

- The Bouyei people — Bouyei language — Bouyei writing(方塊布依字)

- The Bai people — Bai language — Bai writing(僰文)

- The Dong people — Dong language (China) — Dong writing(方塊侗字)

Other languages, all now extinct, used separate logographic scripts influenced by, but not directly derived from, Chinese characters:

- The Jurchens (Manchu ancestors) – Jurchen language – Jurchen script

- The Khitans (Mongolic people) – Khitan language – Khitan large and small scripts

- The Tanguts (Sino-Tibetan people) – Tangut language – Tangut script

During Qing dynasty, palaces, temples, and coins have sometimes been inscribed in five scripts:

- Chinese

- Manchu

- Mongol

- Tibetan

- Chagatai

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty, the official writing system was:

- ‘Phags-pa script

The reverse of a one jiao note with Chinese (Pinyin) at the top and Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Zhuang along the bottom.

Chinese banknotes contain several scripts in addition to Chinese script. These are:

- Mongol

- Tibetan

- Arabic (for Uyghur)

- Latin (for Zhuang)

Other writing system for Chinese languages in China include:

- Nüshu script

Ten nationalities who never had a written system have, under the PRC’s encouragement, developed phonetic alphabets. According to a government white paper published in early 2005, «by the end of 2003, 22 ethnic minorities in China used 28 written languages.»

Language policy[edit]

One decade before the demise of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Mandarin was promoted in the planning for China’s first public school system.[9]

Mandarin has been promoted as the commonly spoken language for the country since 1956, based phonologically on the dialect of Beijing. The North Chinese language group is set up as the standard grammatically and lexically. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong and Lu Xun writings are used as the basis of the stylistic standard.[9] Pronunciation is taught with the use of the romanized phonetic system known as pinyin. Pinyin has been criticized for fear of an eventual replacement of the traditional character orthography.[9]

The Chinese language policy in mainland China is heavily influenced by the Soviet nationalities policy and officially encourages the development of standard spoken and written languages for each of the nationalities of China.[9] Language is one of the features used for ethnic identification.[11] In September 1951, the All-China Minorities Education Conference established that all minorities should be taught in their language at the primary and secondary levels when they count with a writing language. Those without a writing language or with an «imperfect» writing language should be helped to develop and reform their writing languages.[11]

However, in this schema, Han Chinese are considered a single nationality and the official policy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) treats the different varieties of Chinese differently from the different national languages, even though their differences are as significant, if not more so, as those between the various Romance languages of Europe.

While official policies in mainland China encourage the development and use of different orthographies for the national languages and their use in educational and academic settings, realistically speaking it would seem that, as elsewhere in the world, the outlook for

minority languages perceived as inferior is grim.[12]

The Tibetan Government-in-Exile argue that social pressures and political efforts result in a policy of sinicization and feels that Beijing should promote the Tibetan language more.

Because many languages exist in China, they also have problems regarding diglossia. Recently, in terms of Fishman’s typology of the relationships between bilingualism and diglossia and his taxonomy of diglossia (Fishman 1978, 1980) in China: more and more minority communities have been evolving from «diglossia without bilingualism» to «bilingualism without diglossia.» This could be an implication of mainland China’s power expanding.[13]

In 2010, Tibetan students protested against changes in the Language Policy on the schools that promoted the use of Mandarin Chinese instead of Tibetan. They argued that the measure would erode their culture.[14] In 2013, China’s Education Ministry said that about 400 million people were unable to speak the national language Mandarin. In that year, the government pushed linguistic unity in China, focusing on the countryside and areas with ethnic minorities.[15]

Mandarin Chinese is the prestige language in practice, and failure to protect ethnic languages does occur. In summer 2020, the Inner Mongolian government announced an education policy change to phase out Mongolian as the language of instructions for humanities in elementary and middle schools, adopting the national instruction material instead. Thousands of ethnic Mongolians in northern China gathered to protest the policy.[16] The Ministry of Education describes the move as a natural extension of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Standard Spoken and Written Chinese Language (Chinese: 通用语言文字法) of 2000.[17]

Study of foreign languages[edit]

English has been the most widely-taught foreign language in China, as it is a required subject for students attending university.[18][19] Other languages that have gained some degree of prevalence or interest are Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian.[20][21][22] During the 1950s and 1960s, Russian had some social status among elites in mainland China as the international language of socialism.