Even if you’ve already polished your chapters to perfection, you still need to prepare various other parts of your book before publishing — namely, the front matter and back matter.

If you haven’t come across these terms before, don’t be intimidated! They simply refer to the first and last sections of a book: the bits that make it look put-together and “official,” rather than like randomly bound pages.

In this guide, we’ll dissect the anatomy of a book, covering which components a publisher can (and should) include in their final product.

In subsequent sections, we’ll burrow deeper into the most common and important sections of a book’s front, body, and back matter. But first, let’s start with a wide-angle view, beginning with…

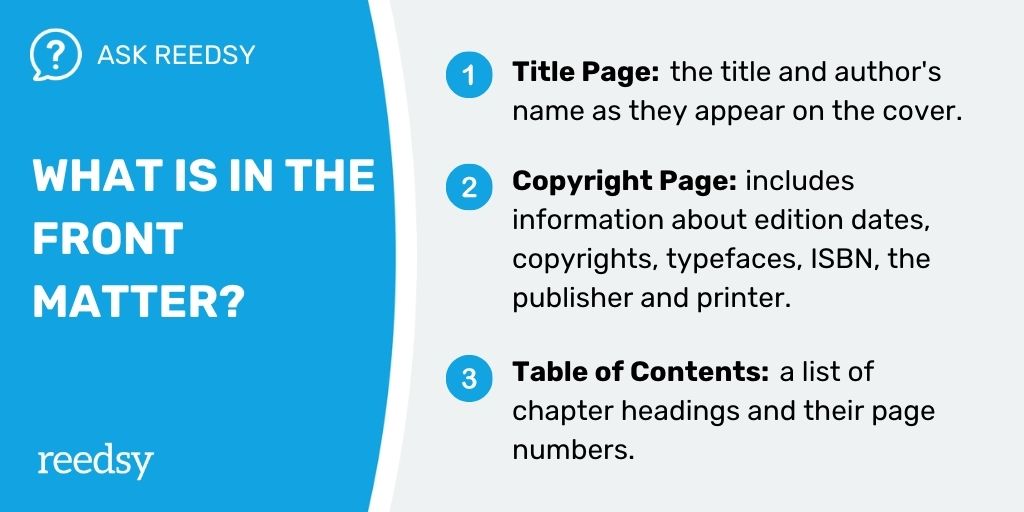

The front matter of a book consists of its very first pages: the title page, copyright page, table of contents, etc. There may also be a preface by the author, or a foreword by someone familiar with their work.

Though many readers skip right over it, the front matter contains some pretty important information about the book’s author and publisher. And for those who DO read it, the front matter forms their first impression, so make sure you get it right!

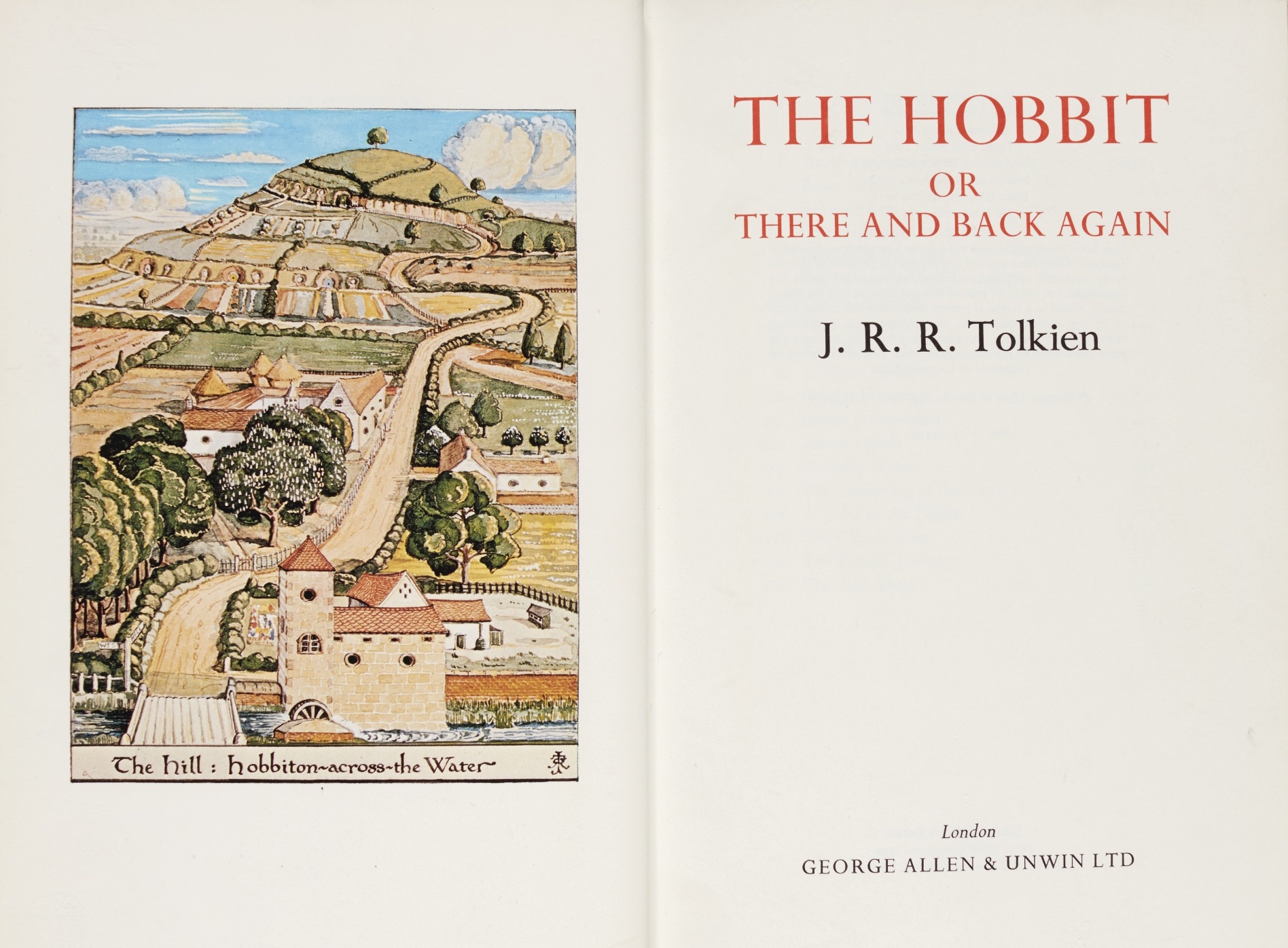

The full title and author’s name — as they appear on the cover.

Frontispiece

A decorative illustration or photo on the page next to the title page. Typically goes on the left.

Accolades

Quotes from esteemed reviewers and publications in praise of the book. This praise often appears on the back cover as well.

Copyright page

Also called a “colophon,” the copyright page includes technical information about copyrights, edition dates, typefaces, ISBN, as well as your publisher and printer. Usually appears on the reverse of the title page.

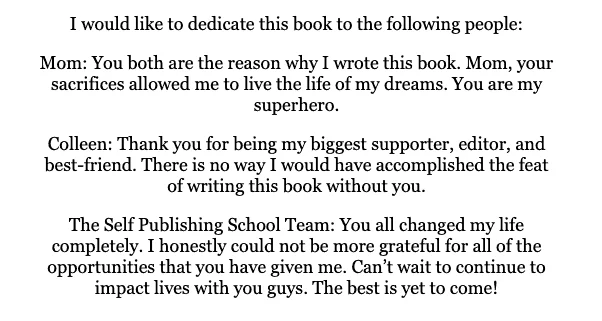

Dedication page

A page where the author names the person or people to whom they dedicate their book, and why. This typically comes after the copyright page.

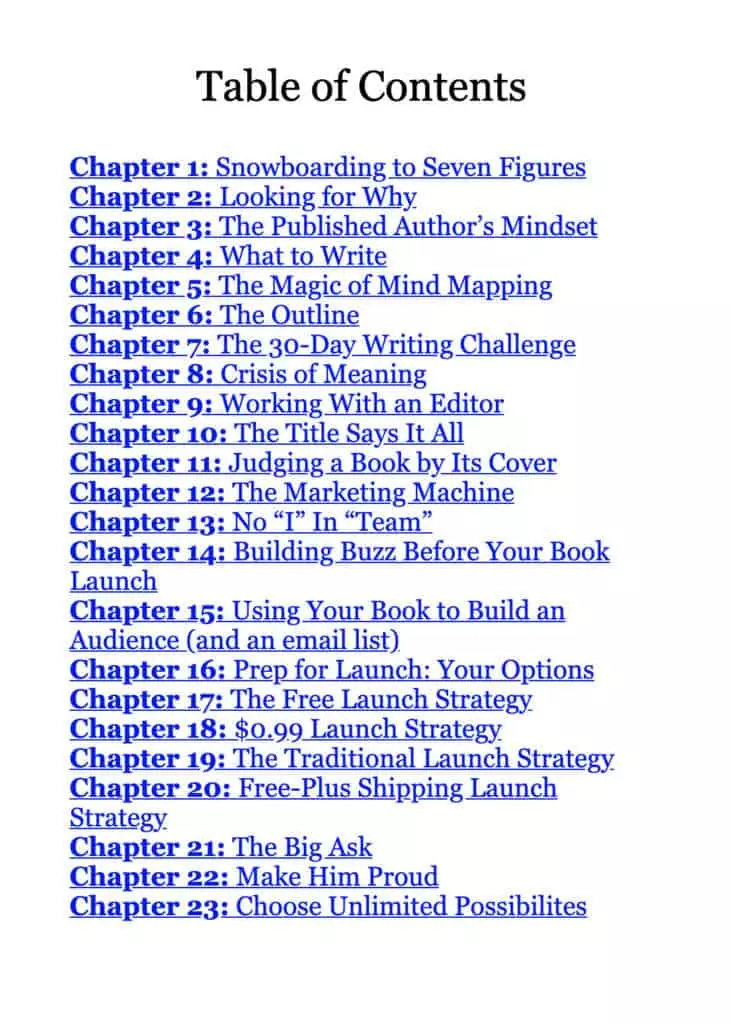

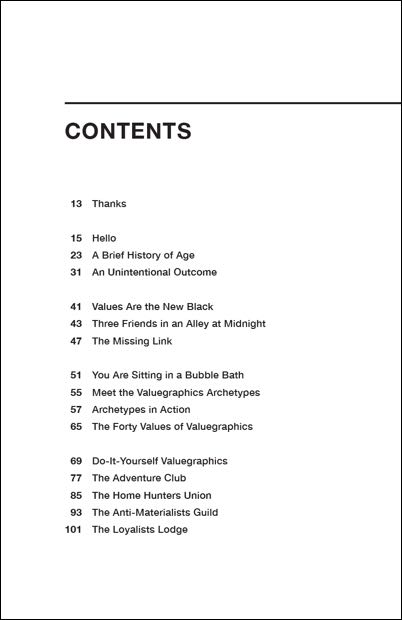

Table of contents

A list of chapter headings and the page numbers where they begin. The table of contents (abbreviated ToC) should list all major sections that follow it, both body and back matter.

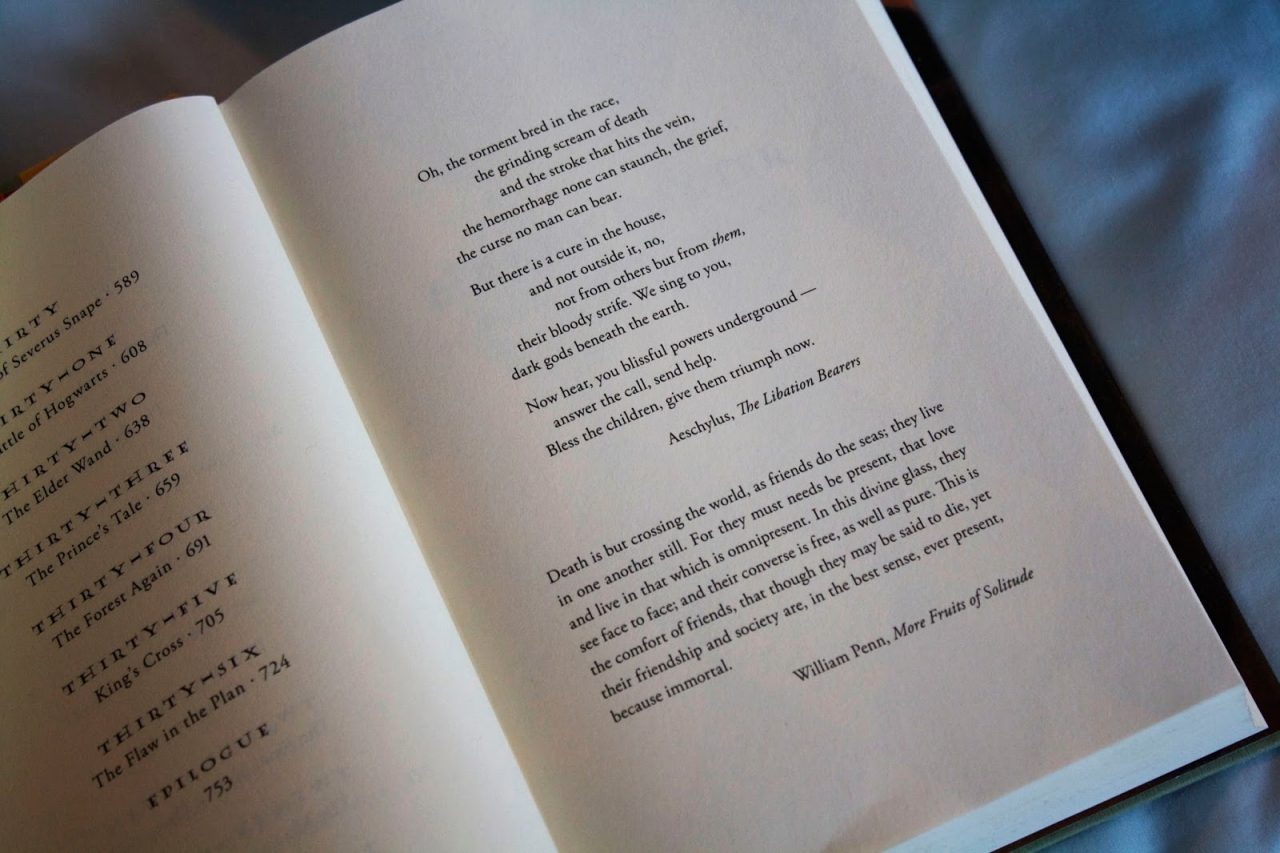

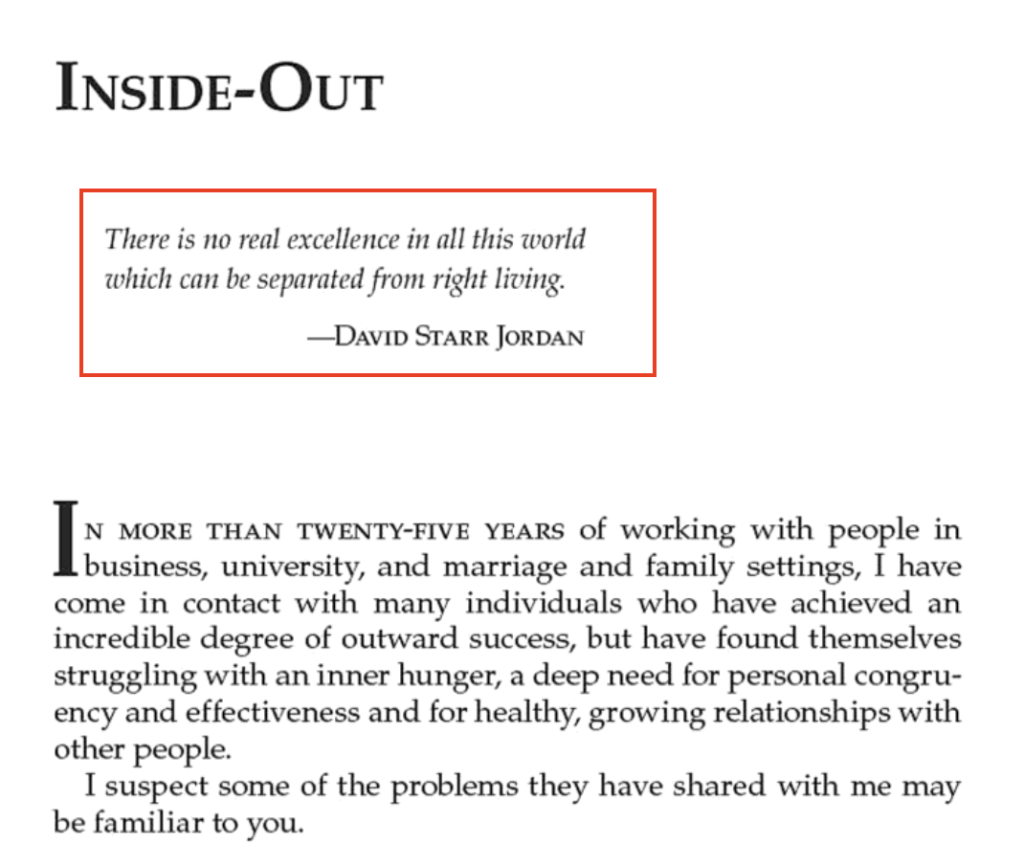

Epigraph

A quote or excerpt that indicates the book’s subject matter, the epigraph can be taken from another book, a poem, a song, or almost any source. It usually comes immediately before the first chapter.

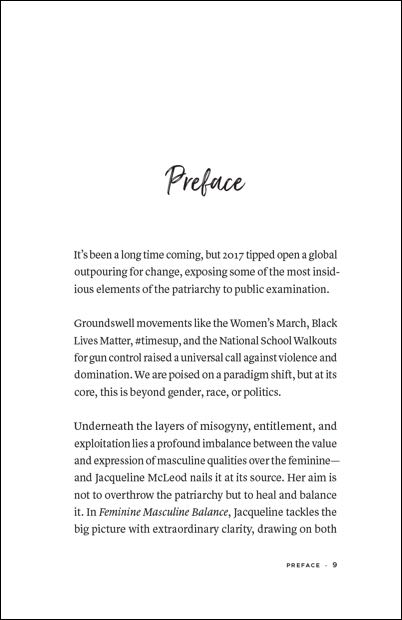

Preface

An introduction written by the author, a preface relates how the book came into being, or provides context for the current edition.

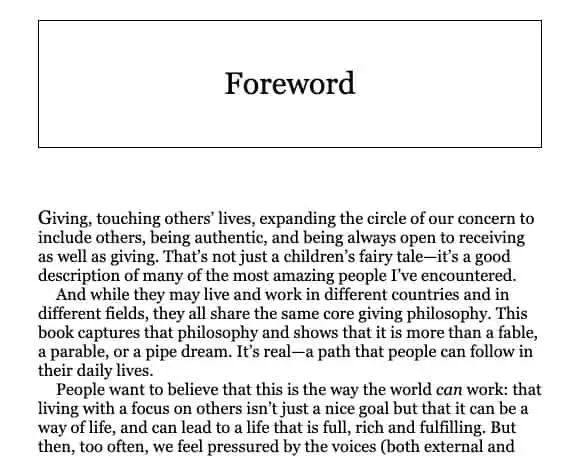

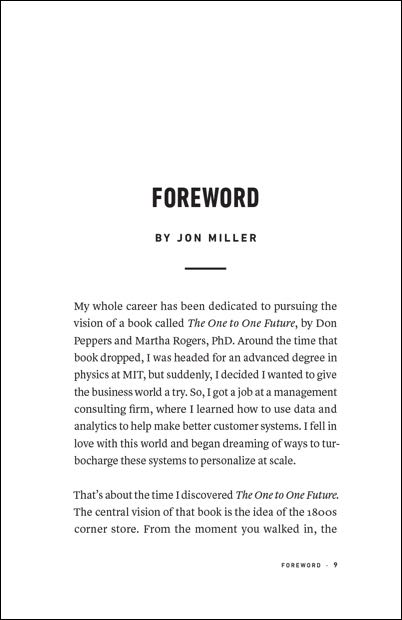

Foreword

An introduction written by another person, usually a friend, family member, or scholar of the author’s work.

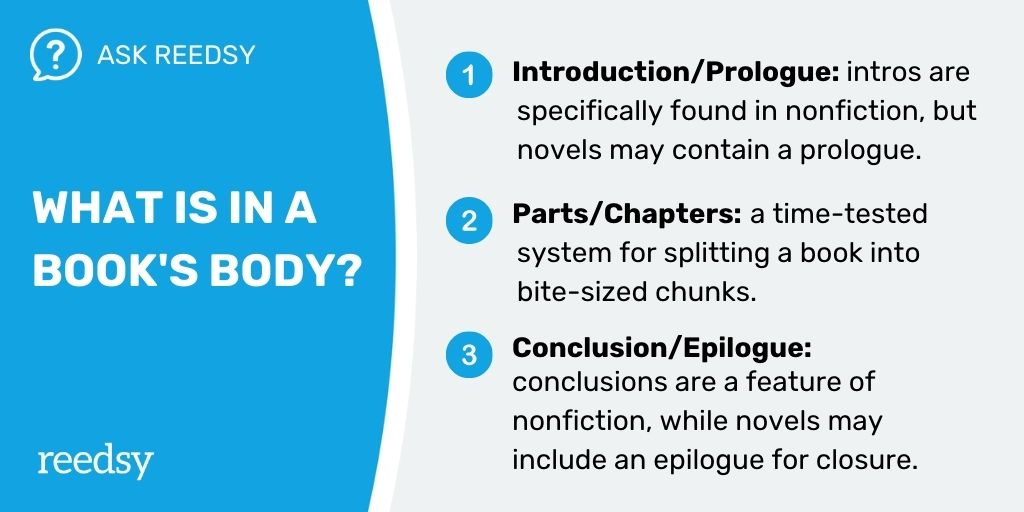

The body

The body of a book is pretty self-explanatory: the main text that goes between the front matter and back matter. For readers and writers alike, this is where the magic happens — but it’s not just the content that’s crucial, but also how you arrange it. Don’t worry, we’ll show you how!

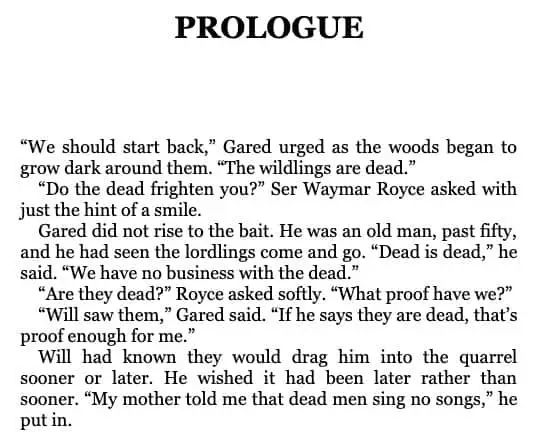

Prologue (for fiction)

A section just before the main story begins, a prologue aims to set the stage and intrigue the reader. Indeed, many prologues contain intriguing events that only become contextualized later in the story.

Introduction (for nonfiction)

A few pages that usher the reader into the subject matter. The intro goes over early events or information related to the main narrative, so the reader has a solid footing before they begin.

“What’s the difference between a preface and an introduction? A preface is personal to the author, discussing why they wrote the book and what their process was. An introduction relates directly to the subject matter and really kicks things off — which is why it’s part of the body, not the front matter.”

Chapters

Every single book has chapters, or at least sections, into which the narrative is divided. These chapters may not be designated by a chapter heading, or appear in a ToC; some authors start new chapters just by using page breaks. But if you don’t use anything to break up your content, your readers will not be happy. (Also, if you’re unsure how long your chapters should be, check out this post on the subject!)

Epilogue (for fiction)

A scene that wraps up the story in a satisfying manner, an epilogue often takes place some time in the future. Alternatively, if there are more books to come in the series, the epilogue may raise new questions or hint at what will happen in the next book.

Conclusion (for nonfiction)

A section that sums up the core ideas and concepts of the text. Explicitly labeled conclusions are becoming less common in nonfiction books, which commonly offer final thoughts in the last chapter, but academic theses may still be formatted this way.

Afterword

Any other final notes on the book; can be written by the author or by someone they know.

Postscript

A brief final comment after the narrative comes to an end, usually just a sentence or two (e.g. “Matthew died at sea in 1807, but his memory lives on”).

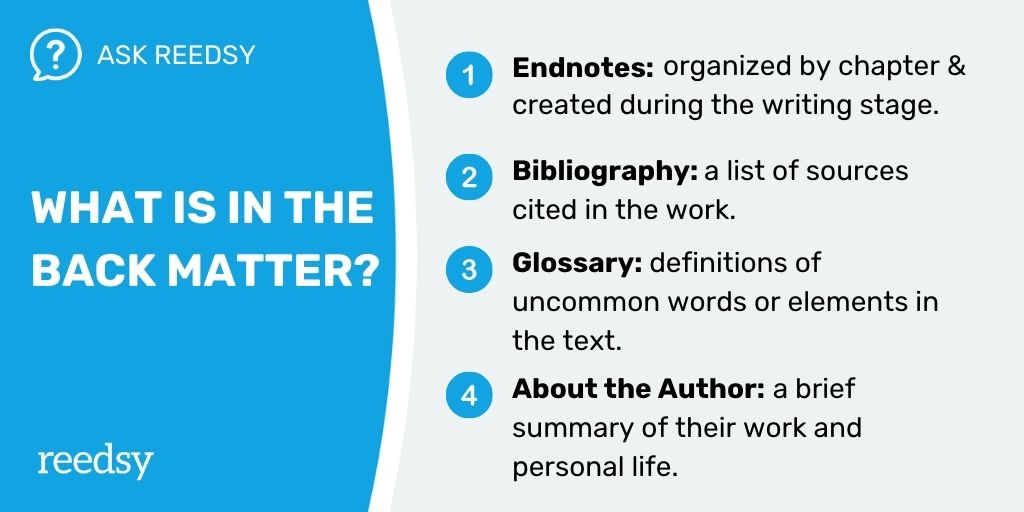

The back matter

The back matter (also known as the “end matter”) is — you guessed it — material found at the back of a book. Authors use their back matter to offer readers further context or information about the story, though back matter can also be extremely simple: sometimes just a quick mention of the author’s website or a note from the publisher.

Acknowledgments

A section to acknowledge and thank all those who contributed to the book’s creation. This may be the author’s agent and editor(s), their close friends and family, and other sources of inspiration. The acknowledgments typically appear right after the last chapter.

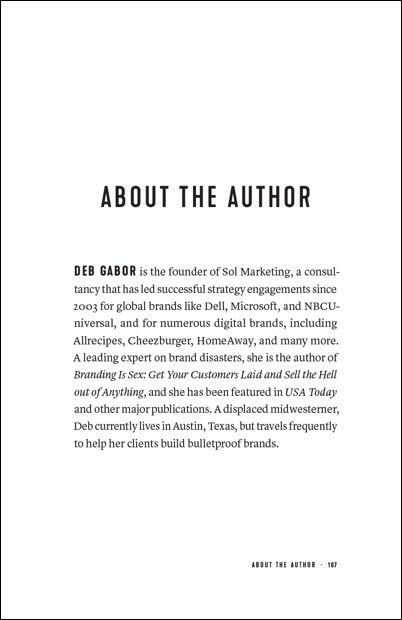

This is where the author gives a brief summary of their previous work, education, and personal life (e.g. “She lives in New York with her husband and two Great Danes”). For more on this topic, read through our guide to writing an author bio or check out some stellar About the Author examples.

Copyright permissions

If the author has sought permission to reproduce song lyrics, artwork, or extended excerpts from other books, they should be attributed here (may also appear in the front matter).

Discussion questions

Thought-provoking questions and prompts about the book, intended for use in an academic context or for book clubs.

Appendix or addendum (nonfiction)

Additional details or updated information relevant to the book, especially if it’s a newer edition.

Chronology or timeline (nonfiction)

List of events in sequential order, which may be helpful for the reader, especially if the narrative is presented out of order. A chronology is sometimes part of the appendix.

Endnotes

Supplementary notes that relate to specific passages of the text, and denoted within the body by superscripts. Almost always used in nonfiction, but occasionally found in experimental/comedic fiction as well, such as Infinite Jest.

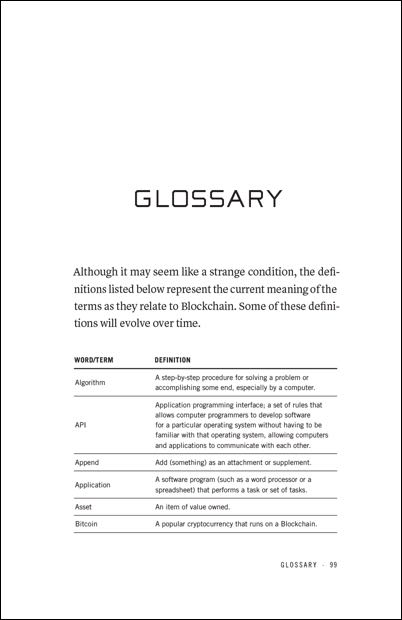

Glossary

Definitions of words or other elements that appear in the text. In works of fiction, the glossary may contain entries about individual characters or settings. The glossary usually appears in alphabetical order.

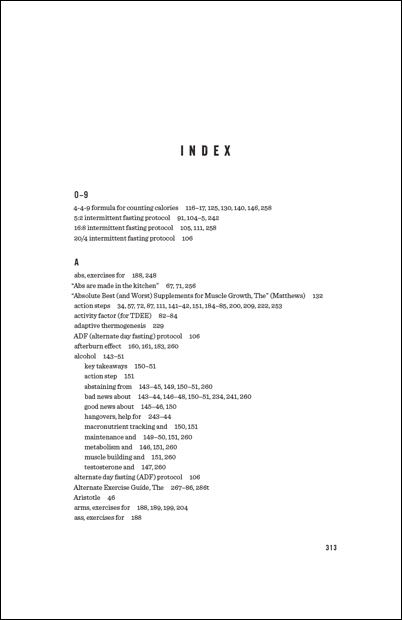

Index

A list of specialty terms or phrases used in the book, along with the pages on which they appear, so the reader can find them easily. The index is also usually in alphabetical order.

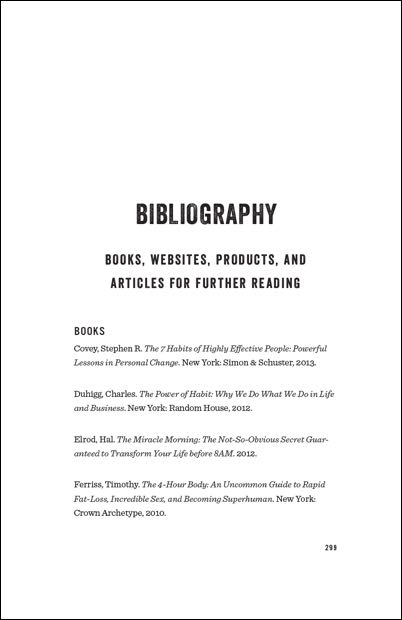

Bibliography/reference list

A comprehensive breakdown of sources cited in the work. Your bibliography should follow a manual of style — luckily, it’s easy to create one using free tools like Easybib. Note that this is a formal list of citations, not a bonus reading list on your subject; that would go in the afterword or appendix.

Get a professional to format your book

Reedsy’s professional designers can make your books look like they belong on the bestsellers lists. Sign up for FREE and meet them today.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

If you’re ready to go a little deeper, head to the next part of this guide and prepare to get up close and personal with copyright pages!

For all the books we may have read during our lifetime, we probably haven’t paid much attention to the actual parts that, collectively, comprise the interior content of books. From the title page that launches the front matter to the index or bibliography that completes the back matter, the sections of a book all serve a particular role in its cohesion.

When self-publishing your first book, it pays to know how the parts of a book function as integral parts of the larger whole. Understanding not only each component’s purpose but also the exact placement of each within the body of the manuscript will keep you on track to align with the publishing industry standards.

Basic Parts of a Book to Know Before Publishing

The anatomy of a book is divided into two primary sections, the front matter and the back matter.

As you can surmise, the front matter precedes the body of work or the story. And, accordingly, the back matter follows the work or story. Not every manuscript will include all of these parts. The author selects the parts of the book that best fit his or her genre or story.

For example, a nonfiction book may require some additional back matter elements, such as an appendix or addendum. It may even need a timeline or chronology, elements not required in a work of fiction. The author will pick and choose the elements that are appropriate for their specific book.

So, what are the parts of a book?

Front Matter

The front matter is the first section of the book that the reader encounters. These pages outline the various technical details as well as some input from the author about what inspired or drove the project. The front matter includes:

1. Title page

The title page contains the title of the book, the subtitle, the author or authors, and the publisher.

2. Copyright page

The copyright page, or edition notice, contains the copyright notice, the Library of Congress catalog identification, the ISBN, the edition, any legal notices, and credits for book design, illustration, photography credits, or to note production entities. The copyright page may contain contact information for individuals seeking to use any portions of the work to request permission.

3. Dedication

The dedication page allows the author to honor an individual or individuals. The dedication is usually a short sentence or two.

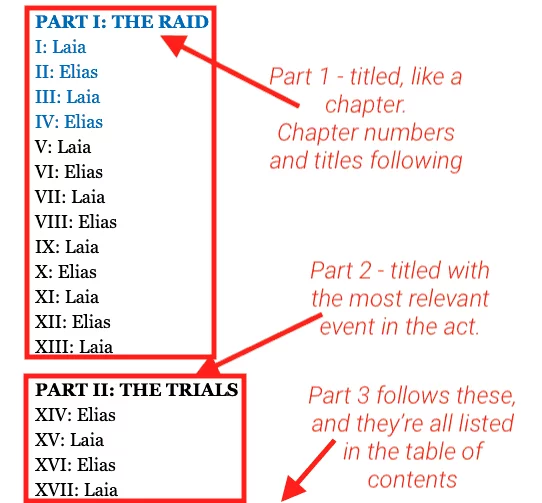

4. Table of contents

The table of contents outlines the book’s body of work by dividing it into chapters, and sometimes sections or parts. Much thought goes into the titles of the chapters, as the chapter titles can set the tone for the book. When someone quickly glances through the table of contents, they should be able to discern the scope and basic theme of the book.

5. Foreword

The foreword is a short section written by someone other than the author that summarizes or sets up the theme of the book. The person who writes the foreword is often an eminent colleague or associate, a professional who has had personal interaction with the author.

6. Acknowledgments

This page allows the author to express thanks to individuals who may have inspired them, contributed research or data, or helped them during the writing process. Acknowledgments are a public thank you for the support and contributions of individuals who were involved in the project.

7. Preface or Introduction

The author explains the purpose behind writing the book, personal experiences that are pertinent to the book, and describes the scope of the book. An introduction can be deeply personal, seeking to draw the reader into the book on an emotional level, and usually explains why the book was written. For scholarly works, the preface or introduction helps erect a framework for the content that follows, as well as to explain the author’s point of view or thesis.

8. Prologue

With works of fiction, the prologue is written in the voice of a character from the story and sets the scene prior to the first chapter. This section may describe the setting of the story or the background details and helps launch the story.

Body Matter

The core content of the book is referred to as the body matter. This is a collection of chapters, sometimes divided up into sections, in which the body of work is organized. In works of fiction, chapters drive the narrative, events, and locations in the story. In nonfiction, chapters might each consist of a singular area of study.

Back Matter

Once the story is completed, it is followed by back matter or end material, those pages that include references pertaining to the core content, as well as an author biography in some cases. Back matter includes:

1. Afterword or Epilogue

These are author comments that follow the end of the body matter. These thoughts may summarize the project or the experience of writing it that helps bring closure to the book. The epilogue can help soothe the reader after a particularly harrowing story. Or even serve as a final chapter that helps to wrap up the loose ends of a story.

2. Appendix or Addendum

The addendum refers to documents that were added after the body of work that may not have fit in with the narrative or is simply additional information that fortifies the work.

3. Glossary

The glossary is an alphabetical list of terms and definitions found within the body matter. These terms may be common terms or specialized terms that refer to a particular field of study.

4. Bibliography or Endnotes

The bibliography is the listing of books or literary sources that were cited within the body matter. These sources may be books, magazines, or online sources that were accessed during the research phase. Endnotes resemble footnotes that are found in the back matter instead of at the footer of a page.

5. Index

A guide that offers an alphabetical list of terms, people, concepts, or events with the associated page number. The index provides an easy manner to locate key items within the body matter.

6. Author biography

The biography page summarizes the author’s professional background. The biography should be relevant to the publication and also include a few personal facts about the author. Instead of a page at the end, the author’s biography may be on the dust jacket, or on the back cover.

Need Help Formatting Your Book?

Once you have written a bestseller, there are important next steps to undertake. The next stage of publishing is ordering the various front matter and back matter elements according to standard publishing guidelines for the genre. Trying to sort out the basic parts of a book can become a quagmire for the novice who desires a professional final project, but who might benefit from a guiding hand.

The pros at Gatekeeper Press can assist the self-publishing author in assembling the various sections of a book in the correct order. In addition, our team can guide authors through all the formatting and design steps to create a first-class publication. Check out Gatekeeper Press today!

For start, we should define the paragraph. There are many definitions of it. Let’s take, that it is a non-named, but maybe numbered sequence of sentences, visible as one text block.

Second, I won’t speak on sub- and super- terms. Obviously, we could add them at wish. Let’s search for the «naked» terms.

I thought, the most elaborated documents makes the Catholic Church.

They use Part, Section, Chapter, Article, Paragraph.

Also they have about 4-5 levels under their paragraph. Names of them are unknown for me. But it is obvious that their paragraph is something else, and much greater than usual one — about 8 A4 pages.

Lawyers love complicated documents, too. According to this law site, Clauses could be equivalent to Articles. They also add Items. Their sections are below paragraphs and divided in Phrases — obviously, equivalent to our paragraph.

A West African lawyer site «Akoma Ntoso» gives us even more structural terms. It adds to already mentioned:

tome, list, statement, point, indent, alinea.

The title can appear not only as a name of some element, but as that very element. On the contrary the article can mean the title of something (explained here)

With list we are coming to structural elements, that are on the same level with usual ones, but have special name due to their special use.

Also, there are names for special kinds of texts. They can have special names for structural elements. Hunting with Thesaurus in the Free Dictionary, I have found:

- canto — a major division of a long poem

- episode — a brief section of a literary or dramatic work that forms part of a connected series

- passage — a section of text; particularly a section of medium length

- sura — one of the sections (or chapters) in the Koran; «the Quran is divided in 114 suras»

- mezuza, mezuzah — religious texts from Deuteronomy inscribed on parchment and rolled up in a case that is attached to the doorframe of many Jewish households in accordance with Jewish law

Feel free to use >-)

Putting together a book willy nilly won’t get you the book sales you’re looking for. If you lack the right parts of a book, yours will look low quality, and it won’t sell (or get good reviews).

You know what you want to write about…

What you don’t know is which parts of a book are actually necessary in your book.

Getting this wrong can make you look like a real amateur instead of a credible professional—which is what you actually want.

Right?

Knowing which parts of a book to include in yours and which don’t make any sense starts with knowing what they are to begin with.

These are the parts of a book you need & what we’ll cover in detail for you:

- Book Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Prologue

- Epilogue

- Epigraph

- Book introduction

- Inciting incident

- Sections of a book

- Act structure

- First slap

- Second slap

- Climax

- Acknowledgements

- Author bio

- Coming soon / Read more

- Synopsis

Click to jump to that section.

What are the parts of a book?

Design and content make up the entirety of the book, including the title, introduction, body, conclusion, and back cover.

In order to write a book in full, you need to have all the moving parts to make it not only good but also effective.

Without essential pieces, your book will appear unprofessional and worse: you’ll lose the credibility and authority writing a book is so useful for.

Parts of a Book You Need for Success

It’s not enough to just write and self-publish a book by throwing it up on Amazon or any other publishing site.

You have to get the parts of your book right if you want it to sell more, get those 5-star reviews, and place you as an authority figure in your field.

Here’s how to do that.

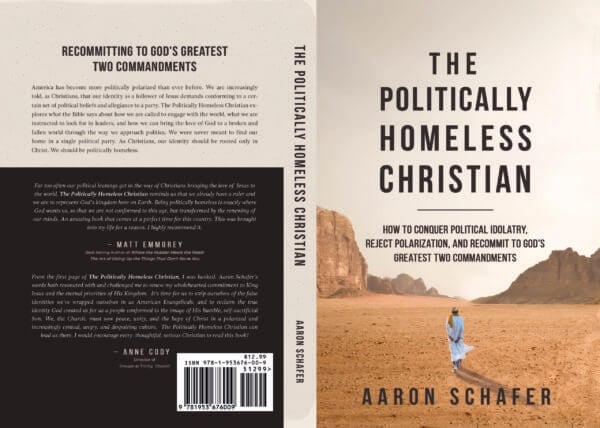

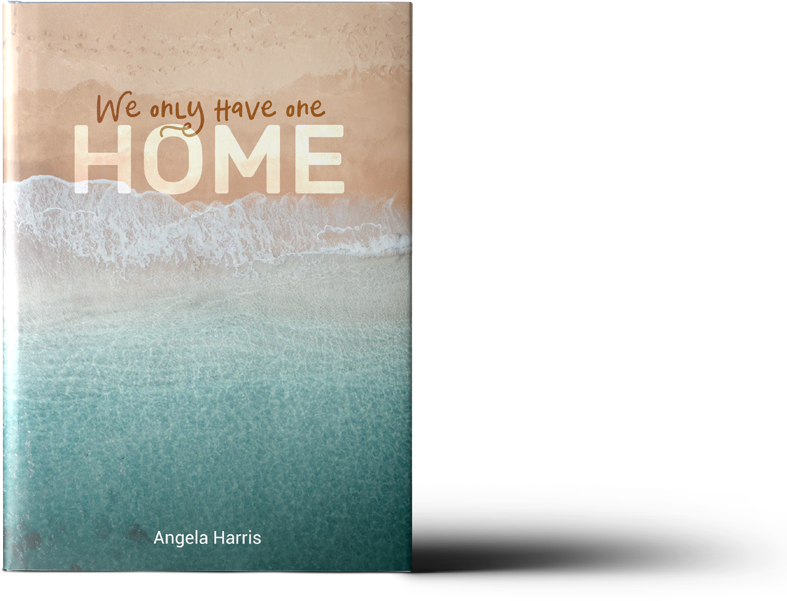

#1 – Book Cover

Every book needs a great book cover. As much as we’d love to think people don’t just a book by its cover…they do.

Having a quality book cover is among one of the best ways you can ensure your book sells well, especially as a self-published author. It’s the first thing they see, and a potential buyer can form an opinion in seconds.

Here’s an example of a full, front-to-back strong book cover that fits the tone, style, and contents of a book titled The Politically Homeless Christian by Aaron Schafer.

#2 – Title Page

For obvious reasons, your title is important…

But that’s not all that’s important to your book. The title page is also necessary and without it, your book will be missing something crucial.

Your title page serves as a means of not only declaring your title clearly, but also ensuring your name, subtitle, endorsement, and any other crucial information is present for your readers to view clearly.

Here’s an example of a great title page and what you can use to replicate your own from I Wish Everyone Was an Immigrant by Pedro Mattos:

As you can see, the title page is really just the main title, any subtitle you may have, and the author’s name as the bottom.

Other than this being an industry standard for books, it helps to keep everything clear without the obstruction of any title images.

#3 – Copyright

Your book needs to be copyrighted. Unless you’re okay with others stealing its content and reaping the rewards for themselves, that is.

We have a great guide on what it takes to copyright a book right here for you to view, but here are some of the basics.

- Technically a book is copyrighted as you write it. But if you want it to be fully legal, you do have to pay to have it copyrighted.

- Your copyright content will change depending on the type of book you’re writing.

- There are certain copyrights you cannot have exclusive rights to depending on what you cover in your book, which is usually impacted the most by what you write in a memoir and its legality

Here’s an example of what a copyright section of a book may look like:

#4 – Table of Contents

There are a lot of reasons to have a table of contents in your book. For one, it helps readers know where to find the information they’re really looking for.

Secondly, this is highly useful in kindle or ebook versions of your book in order to help readers click and navigate without having to actually arrow over through the pages in order to get there.

The happier the reader, the better the reviews they leave.

What is a table of contents?

A table of contents is a list of a book’s chapters or sections with the heading name and often the page number if there are no links inside.

Here’s an example of this part of a book:

#5 – Dedication

This is the part of a book that most of us write long before the actual book is finished…we just tend to jot it down in our minds instead of on paper.

Your book dedication is like your acceptance speech when given an award. Except your book is the award and therefore, you get to write this “speech” and place it where everyone can read it before even starting the book.

This dedicated often comes after the title page and before the table of contents.

It’s a short few sentences thanking whomever helped you get to the point of writing the book or just people you want to acknowledge as thanks.

This is an example what a dedication of your book may look like from our own Student Success Strategist Pedro Mattos’s debut book I Wish Everyone Was an Immigrant:

#6 – Foreword

If you’re looking to increase your credibility, get a book endorsement by someone who knows you and your story well, then a foreword is what you want.

What is a foreword?

A foreword is an introduction to a book written by someone other than the author that lends credibility to the author’s status to write the book.

Think of a foreword as a sort of endorsement of the book. The person who writes it is usually an author themselves, though they can also just be a person of authority in the same or similar field.

Above is an example of a foreword from The Go-Giver by Bob Burg.

Forewords typically come after the table of contents and before the introduction or first chapter of the book.

#7 – Prologue

Fiction is where prologues live. Oftentimes, stories may need additional context before the actual story begins in order for the reader to make sense of it and elements within the book itself.

What is a prologue?

A prologue is a short chapter that usually takes place before the main story begins as a means of granting understanding to the reader. It’s also used to increase intrigue and captivate readers.

Not all books require prologues and in fact, if you can write your novel without it, that’s actually preferred as many readers skip the prologue altogether.

Below is an example of a prologue from the very popular Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin.

#8 – Epilogue

Not all book series get happily-ever-after endings. When your book series ends but you want a way to let the readers know what’s in store for the characters’ futures, an epilogue is a strong way to do that.

What is an epilogue?

An epilogue is a short chapter that comes after the last chapter of a book as a way to tie the story together in a conclusion.

Essentially, the epilogue is the answer to the question, “what happens to them next?” This serves as a more satisfying way to let readers know that characters live “happily ever after.”

Sometimes the ending of the story isn’t satisfying enough for readers.

That part of their story may end, but if your readers want a more in-depth look at their life “after” the story, that’s when an epilogue would come into play to tie everything together.

#9 – Epigraph

Epigraphs aren’t necessarily important, nor are they required. Oftentimes, these short snippets serve as a way to let readers know what lesson or subject will be covered in the chapter.

What is an epigraph?

An epigraph is a short question, quote, or even a poem at the beginning of a chapter meant to indicate the chapter’s theme or focus. This often ties the current work to predecessors with similar ideas and learnings.

For example, below is an epigraph from The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey.

#10 – Book introduction

Most nonfiction books include an introduction to the book—a chapter before your first chapter as a means to introduce yourself and your credibility or author on the subject matter to your readers.

Your book introduction is extremely important for showing your readers why they should read the book and how you’re the person to help them with whatever problem your book solves.

One of the best ways to do this is to first establish the pain points your book helps to solve, and then make it clear how you, someone they don’t know, can help with this issue. This is the typical strategy for writing a self-help book that really impacts readers.

This usually involves some of your own backstory, but keep it specific to the problem at hand. Your readers don’t need an entire rundown of your personal history.

#11 – Inciting incident

If you’re writing fiction, you may have come across the term “inciting incident” before.

What is an inciting incident?

This is an early part of a book that’s the point of no return for your characters. The inciting incident is what kicks your plot into full drive.

Here are a couple examples of inciting incidents:

- Katniss volunteers to take her sister’s place in The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- Tobias enters the Tournament and gets accepted in The Savior’s Champion by Jenna Moreci

- Bella moves to Forks, where she meets Edward in biology class in Twilight by Stephanie Meyer

- Bran gets pushed off the wall in Winterfell when he catches Jaime and Cersei Lannister together in Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

These are all points in the novel that the characters cannot come back from. In this instance, their lives are changed forever, which drive the plot forward.

#12 – Sections of a book

This will mostly pertain to nonfiction authors, we we’ll cover the fiction equivalent in the next section.

Some nonfiction books are written with different parts. These are usually separated into 3 parts that make up a greater whole in the book.

For example, in the book I’m currently writing, I break it up into 3 separate sections. Each part has its own focus and theme but they all work with one another to achieve a greater purpose.

Here’s an example of how the sections of my book work:

- Part 1 – This part focuses on how your childhood impacts your adult behaviors

- Part 2 – This part aims to show readers how to move past their childhood and get control of their “now”

- Part 3 – This section moves beyond getting control and focuses on how readers can work toward building the future they both want and deserve despite their childhood traumas

Each part of this book has a main focus and theme but when utilized together, they form a solution to a larger problem.

#13 – Act structure

In fiction, instead of creating separate sections like in the example above, you may split your work into different acts.

Most commonly used is the three act structure.

Although this isn’t required of novels, it’s still quite popular to write a book with this structure, as it forms a cohesive order of events that’s proven to be intriguing to readers.

A popular example of this 3 act structure is in Sabaa Tahir’s An Ember in the Ashes, featured below.

#14 – First slap

If you’re familiar with our lingo around how to write a novel, or you’re a student already, you may have heard of the first and second slap.

These are pivotal points in your character’s journey that further the plot and often make their efforts more difficult.

The first slap is often the biggest setback for your character following the inciting incident.

Here are some examples of what a “first slap” is in popular stories:

- Katniss entering the hunger games after trials and tests

- Bella finding out Edward is a vampire in Twilight

- Tobias’s first challenge in the tournament in The Savior’s Champion by Jenna Moreci

All of these have one thing in common: they make the lives harder for the characters.

#15 – Second slap

Like the first slap, the second slap is a pivotal point in the novel where your character faces a downfall, most often after having a win or two under their belt since the first slap.

The second slap needs to be placed shortly after your readers have gained hope in your character’s ability to succeed in whatever their goal is.

The idea behind this is to hook your readers again and let them know that it is not all smooth sailing for your characters throughout the rest of the book.

Oftentimes, the second slap is worse than the first, where 90% of your character’s hope in succeeding is lost and therefore, your readers will lose hope too. This makes them root for your character even more, increasing the amount they care for your character.

#16 – Climax

We all know the climax of the book is the most important part. It’s where your character faces the biggest obstacle in achieving their goal in the book.

Here are a few examples of climaxes in popular books:

- Whenever Harry Potter comes face-to-face with Voldemort in the books

- Katniss and Peeta are up against one more foe before “winning” the games in the first book

- Bella gets taken by James and Edward has to fight to save her

The climax is the last challenge before the ending, or resolution, of your book. It is the point of the highest tension and it’s where your character faces the worst odds—worse than the first and second slaps.

#17 – Acknowledgements

We all have people in our lives to acknowledge for our success in writing a book.

Much like the dedication, the acknowledgments are meant to recognize impactful people in our lives. These, unlike the dedication, typically come at the end of the book and can be written in longer, paragraph form as a pose to a short sentence for each.

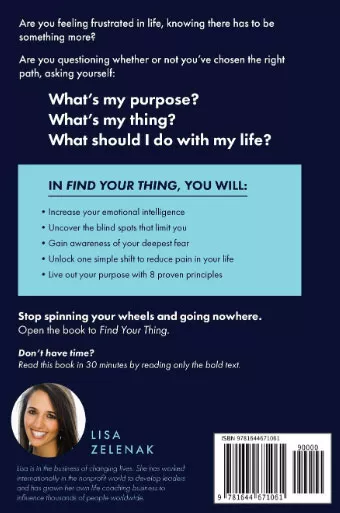

#18 – Author bio

Not all books contain an author bio in it, specifically fiction (unless it’s a hardback copy).

If you’re writing a nonfiction book, however, is a type where the author bio can be at the bottom of the back page of your book, beneath the back cover synopsis.

Your author bio doesn’t have to be very long. Keep it short and simple while still showing your readers your credibility in what your book covers.

#19 – Coming soon / Read more

This part of a book might not matter to you unless you have a book series or multiple books to your name.

The coming soon and read more pages are used to help your readers purchase and read more of your books.

This section of a book often comes at the very end, after your epilogue and acknowledgments. It’s a single page with the cover images of your other book/s, their titles, and links for your ebook copy.

This not only makes it easier for your readers to buy the next book, but it’s also a great way to sell more books overall.

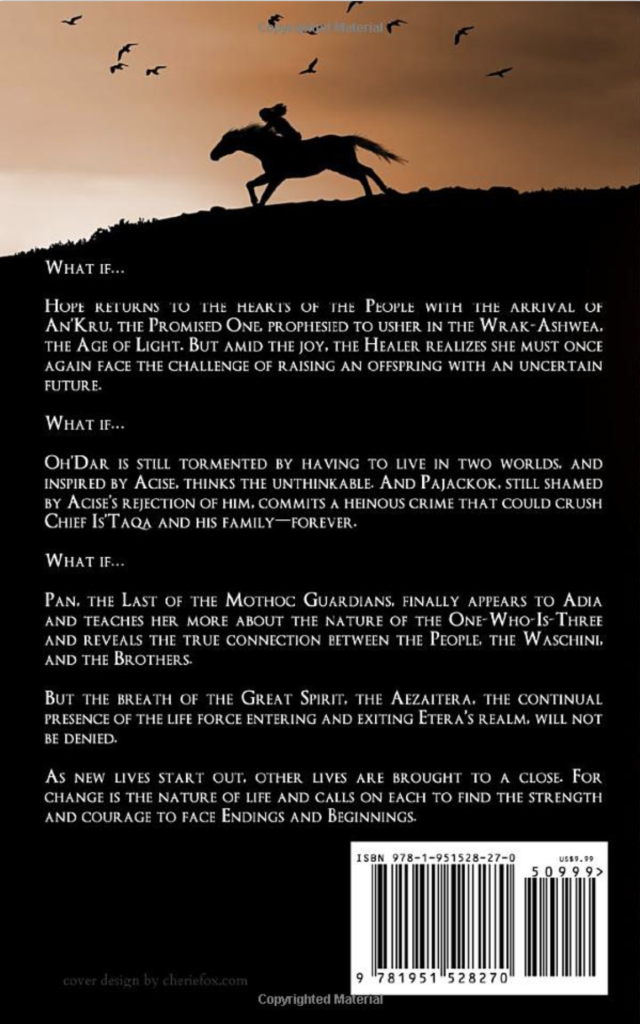

#20 – Back cover or synopsis of a book

I saved the best (and most important) for last. The back cover, also known as the synopsis of your book, is by far the most critical for getting people to buy.

Without a good synopsis to hook readers and buy them into your book, you won’t sell.

These are crucial for both fiction and nonfiction.

With your fiction synopsis, you want to create intrigue and show your readers that they’ll get a good story. The trick is doing this with a few short paragraphs.

Here’s an example of a fiction synopsis that works, from Fundamentals of Fiction student Leigh Robert’s Endings and Beginnings: Wrak-Ayya: The Age of Shadows Book 10.

Here’s a nonfiction example of the back cover from Lisa Zelenak’s Find Your Thing:

Parts of a Book in Summary

As you can see, these look very different, though they serve the same purpose. The back of your book is the first thing someone reads in order to decide if they want to buy your book.

Make it concise, convincing, and show them the value they’ll get from reading it—be that an entertaining read or a solution to their problem.

Ready To Become a Published Author?

Grab your copy of the #1 Bestselling Book on How to Become A Published Author…

Does the foreword belong before the preface? When do the page numbers start? What’s the difference between a preface and an introduction? If you need answers to demystify the front matter of your book, read on.

Books are generally divided into three sections: front matter, principal text, and back matter. Front matter is the material at the front of a book that usually offers information about the book. The principal text is the meat of a book. Back matter is the final pages of a book, where endnotes, the appendix, the bibliography, the index, and related elements reside. Though the front matter may not be as sexy as the main text or as information packed as the back matter, it’s an opportunity for authors to set the tone for their readers’ experience.

Barebones front matter may consist of only a half-title page, full-title page, and copyright page in a work of fiction, and these elements plus a table of contents in a work of nonfiction. A really extensive front matter section might contain the following components (listed in the order preferred by The Chicago Manual of Style): half title, series title or frontispiece, title page, copyright page, dedication, epigraph, table of contents, list of illustrations, list of tables, foreword, preface, acknowledgements (if not part of the preface or in the back matter), introduction (if not part of the principal text), list of abbreviations (if not in the back matter), chronology (if not in the back matter), and second half title.

The name of each component is generally descriptive of the information it provides. For example, a table of contents is a list of the contents in a book, and the half title page consists only of the main title (sans subtitle). The kind of information that goes into a foreword, an introduction, or a preface, however, is less obvious. As a result, many authors choose not to include these elements in their books, which is unfortunate because each of these components could enhance a reader’s experience with a book.

The front matter is the only section where a page can be easily added once the book is in page proofs (printed typeset pages that show all elements as they will appear in a printed book). Because of this, the front matter has a separate page numbering sequence from the rest of the book. All pages in the principle text have arabic numbers, and the first page of actual content is page 1 (this may be chapter 1 or an introduction or prologue). Front matter pages are numbered from 1 through whatever page is necessary, but the page numbers appear as lowercase roman numerals. Some front matter pages do not include page numbers—blanks, half title, title, copyright, dedication, and epigraph—although they are counted as numbered pages.

Be Foreword

A foreword is a substantial introduction or statement about a book by someone other than the author of the book. Since someone else is giving your book props just by agreeing to write a foreword and sign his name to it, it’s almost like a very long endorsement of the work minus the gushiness about how great you are. The better the author of the foreword is known, the more helpful the foreword will be in generating interest in your book and increasing sales. Imagine the readers a foreword by Jack Welch or Steve Jobs would attract compared to a foreword written by your neighbor (unless your neighbor happens to be Jack Welch or Steve Jobs, of course). But don’t sweat it if you don’t have access to the big names; it’s unlikely that a foreword by Author’s Neighbor will hinder your sales.

Tell ’Em All About It

A preface could be described as a book’s profile. It includes material about the book that is separate from the book’s subject matter, such as why the author decided to begin the work, the scope of the work, and the work’s intended audience. Sometimes authors use the preface as a place to discuss research methods and to acknowledge assistance, though the latter is usually included in a separate front matter element, the acknowledgments.

Introduce Yourself

Though introductions vary in the type of content they present, they generally should identify the book’s audience, establish a clear sense of the topic and angle the author will develop, tell the reader why the topic has value, and set the stage for the rest of the book by establishing the necessary context and language. Some introductions will describe the function of each chapter in a book, which could help readers decide if they want to read the entire book or only parts of it.

The introduction should be more closely connected to the book than any other component in the front matter. Ideally, an introduction functions as the first couple of paragraphs in a chapter should, by drawing in readers and making them want to keep reading.

Either the author or someone the author deems appropriate and capable to write about the subject can write an introduction. Keep in mind that though introductions can be written by the author or a contributor, someone other than the book’s author must write the foreword.

A big bad review of the order in which the top 10 most common front matter elements should be presented:

- Half-title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

During the editing of my first book, my editor asked me if I wanted to put in a List of Contributors.

What?

Then he proceeded to ask me a series of other questions I had never even thought to consider.

Do I need a foreword? Should I include an index? What the hell even is “back matter”?

It felt overwhelming.

He sent me a list of all the parts of a book, and looking at this list, I got confused by many of the sections. I was mostly afraid of leaving something out and looking like an idiot.

I eventually figured it all out, learned what all of these things were, and realized something: most of this stuff was useless.

In this post, I am going to walk through all the parts of a book, and help you understand the reasons for including them, so you can decide if they belong in your book.

What Goes In The “Front Matter”?

Front matter comes before your book’s content and introduces the reader to your book. It’s made up of several components, many of which your book does not need.

Let’s look at each component to see which ones you should include.

Half Title Page

This is the first page of your book a reader sees. It has your book title with no subtitle or byline.

Why you might need it: It’s a customary part of every book.

Do most books need it: Yes, pretty much. All books have it, yours might look weird without it.

Series Title Page

If you’ve published other books, the second page is where you can list them by title. If you need to include the subtitle, you can, but it’s not necessary.

Typically this page begins with: “Also by [Your Name]…”

Why you might need it: To refer readers to your previous books.

Do most books need it: Only if you’ve published other books, and want to promote them.

Blurbs/Testimonials

Also known as endorsements, blurbs are quotes from notable people saying something positive about you or your book. Blurbs can also be included in the cover design, but in the front matter, they typically go in a section called “Advance Praise.”

Why you might need it: Testimonials are a great way to “credential” a book (and more importantly in many cases, an author) and help readers see that the book is relevant to them.

Most of all, testimonials should convince a potential reader to buy the book.

In terms of who to ask: it’s better not to have testimonials than to have bad ones or ones from unknown sources. If you include a testimonial, the reader should recognize the name.

For more guidance on getting good blurbs, check out the guide we wrote on book blurbs.

Do most books need it: No—testimonials are nice to have, not a necessity.

Frontispiece

An illustration on the left (or verso) side of the page facing the title page on the right side (or recto). Originally, the frontispiece (from the French word frontispice) was purely decorative, using architectural elements such as columns and pediments, and went on the title page.

Over time, the frontispiece moved to the verso page and evolved to be more illustrative and informative, giving readers a clue to a book’s themes or the time period in which it was written. Some books, including biographies, used a portrait of the author as the frontispiece.

Why you might need it: If you want your book to look like an old book. A frontispiece is common in classic books, but not today’s books.

Do most books need it: No.

Title Page

This page has your title, subtitle, and byline.

Why you might need it: Same as before—this is a customary part of every book.

Do most books need it: Yes, all books do.

Copyright Page

A page that shares the copyright information and may include the following elements:

The word “Copyright” and the symbol: Copyright ©

Copyright year: The year the book was published.

Copyright owner: In almost every case, this should be you, the author. Publishers should not try to take your copyright or publish the copyright in anyone’s name but yours.

Put the last three elements together on one line: Copyright © 2019 Author Name

Copyright statement: This boilerplate text is mainly a formality, but many books include it.

Here’s an example:

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Publisher information: In conjunction with the copyright notice, publishers will include their name, an email address, and a website to request permission to reproduce the book.

They might also include ordering information and trademark notices for their name or logo.

Disclaimer: Based on the type of book you write, you can include various disclaimers on the copyright page to protect yourself from being sued by readers. Here are a few examples:

Some parts of this book have been fictionalized in varying degrees, for various purposes.

This book is not intended as a substitute for the medical advice of physicians.

The information in this book is meant to supplement, not replace, proper football training.

Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN): A unique identification number the Library of Congress assigns to titles it’s likely to acquire. Librarians use the LCCN to locate a specific Library of Congress catalog record in the national databases and to order catalog cards.

Your publisher must apply for this number in advance of the book being printed through the Preassigned Control Number Program (PCN). After publication, a “best edition” of the book (either paperback or hardcover) must be sent to the Library of Congress. Self-published books, ebooks, and books published outside the U.S. aren’t eligible to receive an LCCN.

Cataloguing-in-publication data: Also known as CIP data, this block of text includes the bibliographical information created by the Library of Congress prior to a book’s publication. It is an abbreviated version of the machine-readable cataloging (or MARC) record found in the Library’s database that is distributed to libraries and book vendors.

For examples of what a CIP data block looks like, click here.

ISBN: The International Standard Book Number is a 13-digit code that identifies the registrant, book title, format, and edition. That means you’ll need separate ISBN numbers for each format of your book (hardcover, paperback, ebook) and a new ISBN for each edition you publish.

ISBN numbers are used by every party involved with ordering, listing, selling, and stocking your book: publishers, booksellers, libraries, internet retailers, and other links in the supply chain.

A traditional publisher will apply for an ISBN on your behalf.

If you’re self-publishing, you can purchase one through an ISBN agency like Bowker.

Place of printing: List where your book was printed.

Edition number: For 2nd edition and beyond, list the edition number here or on the title page.

Printer’s key: A long-held convention of book printing, this seemingly random string of numbers near the bottom of the copyright page is used to indicate the printing history.

For the first edition of a book, you might see: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

For the second edition, the 1 will be dropped: 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Different printers have different conventions around the printer’s key, but the same intent.

Credits: It is common (but not required) to give credit on this page to your cover and interior designer, illustrator, editor, proofreader, photographer, indexer, or production manager.

Why you might need it: You don’t need a copyright page, as you own the copyright for your book when you create it. Since it’s your intellectual property, copyright law automatically applies. A copyright page is helpful to identify the copyright owner.

Do most books need it: Yes.

Dedication

A book dedication is a device that some authors use to bestow a high honor on a person (or small group of people) they want to praise or otherwise spotlight.

The dedication page goes in the very front of the book, after the title page.

Why you might need it: Do you want to thank someone who supported you while writing the book, or call out a person who had a seminal impact on your work? You can dedicate the book to them.

There’s no formula for a dedication, other than keeping it short and sweet. For more detail, read our post on writing book dedications.

Do most books need it: No, although many books have a dedication.

Epigraph

A short quotation that typically faces the table of contents or the first page of the book. Epigraphs can also be used to lead off chapters. Be sure to attribute the epigraph to its source.

Why you might need it: Done right, epigraphs hook the reader and prep them to dive into your book.

Do most books need it: No.

Table of Contents

This page lists each of your chapters by title and includes the page number where they begin. If your book has sections, the section title should go above the chapters in that section.

The designer adds this page during layout once they know the page numbers for each chapter.

Why you might need it: To help readers navigate quickly to certain chapters.

Do most books need it: Yes, all books have them.

List of Illustrations/Figures

Similar to a table of contents, this list includes the page numbers for your book’s illustrations.

Why you might need it: This page is useful only if your book includes illustrations that are critical to understanding your book’s content (e.g. highly technical or science-focused books).

Most books use illustrations as visual aids that add context but aren’t critical for readers.

If you’re in the first group, give your designer a list of illustrations and they’ll generate this page and the corresponding page numbers during layout. The second group can skip this section.

Do most books need it: No.

List of Tables

This page lists your tables and their corresponding page numbers.

Why you might need it: Only if your tables are fundamental to understanding the book’s content.

Do most books need it: No.

List of Abbreviations or Chronology

A list of commonly used abbreviations in your book, alphabetized by the abbreviation (not the spelled out words), and including the page number where the abbreviation is first used.

A chronology is a timeline of events that are covered in your book.

Why you might need it: If your book uses abbreviations the reader is unfamiliar with, or if you include dozens of abbreviations, this page will help the reader keep things straight.

The same is true with the chronology. If your book covers several time periods or includes multiple dates, the reader can quickly reference the chronology if they get confused.

You should include these parts in the front matter if they’re critical to the reader’s understanding of your book. If they’re simply meant as reference points, move them to the back matter.

Do most books need it: No.

Second Half Title

A second instance of the half title page used at the end of the front matter.

Why you might need it: If your front matter is lengthy, a designer might add a second half title page to the front of your main text. Typically it’s followed by a blank page or an epigraph.

Do most books need it: No.

Foreword

A foreword is an introduction that’s written by someone other than the author. The foreword author doesn’t have to read the book, nor do they have to write the foreword themselves.

We wrote the guide on book forewords, and is worth the read if you’re considering including one.

Why you might need it: Most books don’t need a foreword, but there are two reasons to include one.

First, to confer status and credibility on you, the author. If this is your first book, having an expert or well-known authority write your foreword shows readers you should be taken seriously.

The second reason is to provide context and background for the reader. A foreword explains why readers need your book, and says things about the book that you cannot.

A good foreword should confer credibility and provide context. At the very least, it needs to do one of these jobs. If it does neither, it shouldn’t be included in your book.

Do most books need it: No.

Preface

A preface goes after a foreword and before the introduction. It’s your chance to talk directly to the reader about why you wrote the book, what they’ll learn, and why it’s important.

Why you might need it: Unless your preface provides critical insight for the reader before they dive into your content, or otherwise enhances their reading experience, you don’t need one.

Do most books need it: No.

What Goes In The “Back Matter”?

The back matter comes after your book’s content. It’s comprised of supplementary material that enhances the reader’s experience, some of which might be relevant for your book.

Acknowledgments

In the acknowledgments, you recognize and thank everyone who helped you with your book. It’s a way to display your appreciation to them in a public and permanent forum.

Don’t worry about length. You may only write one book in your life, so take as much space as you want to thank everyone. You don’t want to leave someone out for the sake of length.

If you need help writing your acknowledgments, check out our guide to writing book acknowledgments.

Why you might need it: Writing a book is a group effort. Whether it’s family, friends, colleagues, mentors, editors, agents, publishers, or contributors—this is your chance to say thanks.

Being named in the acknowledgments of your book will make a big impact on people. If you can write something meaningful for them, you should. If you can’t, it’s OK to skip this section.

Do most books need it: No, although most books have acknowledgments.

Appendix

An appendix provides additional content that is useful to the reader but would have disrupted the flow of the chapter where it was referenced. In biographies or memoirs, an appendix can include original materials like photos and letters that add richness to the story.

You can have different appendices for different types of information.

Why you might need it: To supplement what the reader learned in the main book text.

Do most books need it: No.

Postface

A postface is like a preface in that it speaks directly to the reader, but unlike the preface, it appears at the end of the book, usually as part of the appendices.

Why you might need it: To offer the reader a comment or explanation that is relevant to the text, but would have confused them if it had been included in the front matter.

Do most books need it: No.

Notes

Also called endnotes, this is a list of notes, arranged by chapter, that further explain material in your book’s main text. Unlike footnotes, which appear at the bottom of the page where the reference is made, endnotes get their own section in the back matter.

Notes and Appendix are very similar, and you probably don’t need both. The only difference—and this is debatable—is that an Appendix tends to be more formal research, and you can have several Appendices, whereas Notes tend to be more informal, and you only have one Notes section.

Why you might need it: To expand the ideas in your book or cite your sources without disrupting the flow of the text. If your notes are longer, or are relevant but not essential to the reader’s understanding of the main text, use endnotes to avoid distracting the reader.

Do most books need it: No.

Footnotes

Unlike endnotes, footnotes appear at the bottom of the page where the reference is made using a superscript number (like this¹) after a word or at the end of a sentence.

Why you might need it: Footnotes are used to add an interesting comment that doesn’t relate directly to the sentence being referenced, to let readers know where you got certain material from, or point them toward resources so they can learn more about the topic being referenced.

The key difference between footnotes and endnotes, aside from the placement, is that footnotes are used to deliver information the reader needs to know while reading the book.

Since footnotes interrupt the flow of the main text, they need to be important.

If the information is relevant but not important, cite it using an endnote.

Do most books need it: No, unless it’s an academic text.

Bibliography or References

A list of the works cited in your book, formatted using the style guide most appropriate for your book. Most books use the Chicago Manual of Style, but scientific books tend to use APA.

Why you might need it: To have the proper citation of other work, so readers can look it up. Basically, if you make a claim, and want to back it up with evidence, a bibliography is the common place to put all these references.

Do most books need it: If you cite other works in your book, yes.

Copyright Permissions

This is where you acknowledge if you reproduced other copyrighted works in your book.

Why you might need it: If you were given permission to use the copyrighted work of another creator, such as a song, book excerpt, or artwork, attribute credit to the creator in this section.

Do most books need it: Only those that include copyrighted material requiring attribution.

Glossary

An alphabetical list of terms used in your book and their definitions.

Why you might need it: If you use terms that are not generally known, or coin new terms for the book.

Do most books need it: No.

Index

An alphabetical list of important terms used throughout your book. Unlike a glossary, definitions are not included, but rather the page numbers for every significant instance of that term.

An index does not include every mention of a term because that kind of cumbersome list would be of little use to the reader. As such, don’t try to do this yourself or use a computer-generated list. An experienced indexer anticipates the reader’s needs and creates an accessible list.

Why you might need it: To provide a reference point for your book’s most important subjects.

Do most books need it: No.

List of Contributors

A list of anyone who helped you with research or contributed content to your book.

Why you might need it: This is different from the acknowledgments in that here, you’re giving people credit for contributing their ideas to the book, not just for assisting you with the process.

Here’s an example: if your book is a collected work where each chapter was contributed by someone, list those contributors by name here and include biographical information.

As the person with the idea who curated and edited these contributions, your name will go on the cover, but those contributors should definitely be credited in this section.

Do most books need it: Only if your book has contributors.

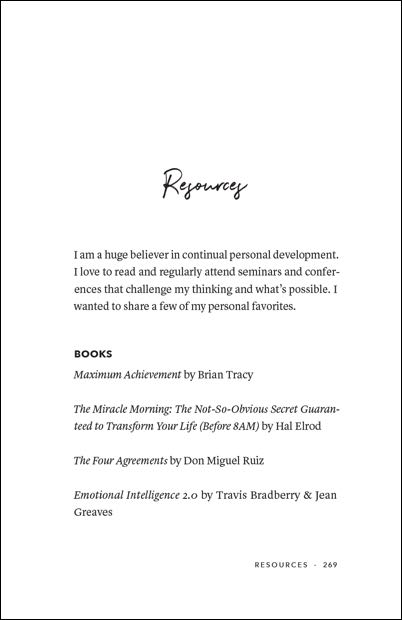

Resources

A list of organizations, associations, websites, books, podcasts, publications, and other sources of information that allow the reader to learn more about your subject.

Why you might need it: The resources section is your opportunity to share your sources of inspiration, those influences that molded you and shaped your book, or that you know would benefit readers who are hungry for more knowledge after they finish reading.

It’s helpful if you have experience with these resources, but it’s not a requirement.

Do most books need it: No.

Coming Soon

If you’re already working on another book, you can use this section (also called “Author Ads”) to give readers a taste of what’s to come with a description of the book or even an excerpt.

Why you might need it: To build anticipation for your next book and get readers excited to buy it.

Do most books need it: No.

About the Author

An expanded look at the author’s life and other works. Unlike the short author bio that adorns your book cover, you can go into much more detail about yourself here.

Most about the author sections are written in third person.

Why you might need it: This is your chance to remind readers of your previous works (or upcoming books) and include a call to action to engage with your other content: websites, online courses, one-on-one coaching, podcasts, training, speaking engagements, and more.

Do most books need it: No, although most books have one.

What Matters?

As you can see, most of the front and back matter is either irrelevant for your book or can be outsourced to a third party such as a designer, indexer, or publisher.

Don’t get bogged down when it comes to the parts of your book outside the chapters.

Your content determines your book’s success, not whether it has an appendix or a preface.

Save this image, print it out and circle the parts of the book that you think you need to include in yours. Remember, only add in what is essential to the reader and supporting the book’s content.

In this tutorial we will look at the different parts of a book (the anatomy of the book); understanding the individual parts of a book will make it easier for you when following the rest of our tutorials and will prove to be invaluable in your bookbinding journey.

If you have ever been confused by the jargon used to describe the physical parts of a book, then this video will help. We explain and demystify a series of terms including spine, boards, hinge and joint, leaf, endpapers, book block and plates. Discover the meanings of more book terms at the AbeBooks’ glossary of book terminology: http://bit.ly/nO8hcA.

Don’t forget to subscribe to our YouTube channel to get access to HD videos of hundreds of Book Binding tutorials and reviews!

My Bible: ABC for Book Collectors by John Carter & Nicholas Barker

Probably the most well known of all reference materials on the subject of book anatomy and book collecting terminology, known by many as THE table of contents or the ‘how-to bible’. It contains a complete A-Z of in-depth descriptions on every aspect of antique and modern book collecting including many descriptive texts on book manufacture and the jargon that goes along with it. A must for any book collector, book enthusiast or anyone interested in bookbinding or book related arts, a fantastic read and one that I always keep next to me when teaching — a timeless classic.

Check out reviews, prices and further information here on Amazon.com.

UPDATE: Now in it’s 9th edition, it’s been updated with the latest web-based terminology which I’ve found very useful in this modern world.

- Hardcover: 264 pages

- Publisher: Oak Knoll Pr; 9 edition (July 31, 2016)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1584563524

- ISBN-13: 978-1584563525

- Product Dimensions: 1 x 5.2 x 8.2 inches

A short, random selection of topics discussed within this book that might be of use to budding bookbinders:

- How to tell japon vellum from India proof paper

- How to take care of pigskin, morocco, or Russian leather

- Library bindings

- Plate-numbers

- Fly-sheet / fly leaf

- Blank verso

- Book Finds: How to Find, Buy, and Sell Used and Rare Books

- Modern Book Collecting: A Basic Guide to All Aspects of Book Collecting

- A Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions

- The Care of Fine Books

- The home-based bookstore

Photos by Binding Obsession — http://bindingobsession.com/parts-of-a-book/

A few more diagrams outlining the parts of a book

External Parts of a Book

Dust Jacket or Dust Wrapper – First used during the 19th century, the original purpose of the dust jacket was to protect the cover of books from scratches and dust which could have been made from fine leather, linen cloth, silk or other expensive materials.

It wasn’t until after World War I when booksellers and publishers realised the correlation between well designed book cover jackets and book sales, during this time an explosion of book cover designs hit the market; it was around the same time that The British Library Started its Dust Jacket Collection (early 1920’s) which now contains over 11,000 items.

In today’s modern world, dust jackets serve the same purpose but are generally used to host eye-catching artwork designed to lure the reader in and increase sales.

Found only on hardcover books, the dust jacket will normally be made from paper or plastic (or plastic covered paper) with the ends of which wrapped inside the book cover.

- History and further information on dust jackets on Wikipedia

- History of the Dust Jacket

- 75 Vintage Dust Jackets of Classic Books

- The importance of Dust Jackets

- Against Dust Jackets

- No Dust Jackets Required

Book Cover or Book Board – The front and back covers of books are often referred to as book covers or book boards as they are often made of bookbinding board and cover the book.

Joint – The Joint of a book is the small groove which runs vertically down the book itself between the book boards (book cover) and the spine. It bends when the book is opened and is only seen on hardcover books. Also called a French joint or French groove, groove, gully, channel, and outer joint.

Raised Bands – Raised Bands were originally the result of cords (or thongs) used during the sewing process which were affixed to the signatures and used to hold the book covers on. Later on in the binding process the spine or backbone would be covered and the bands would be raised above the rest of the spine. This method of binding is less common today, as a result faux bands are used purely for decorative purposes (see video below).

Don’t forget to subscribe to our YouTube channel to get access to HD videos of hundreds of Book Binding tutorials and reviews!

Tail – The Tail is the bottom part of the book.

Hinge – The Hinge of a book is the section between the cover boards and the spine. It’s the part that bends when the book is opened.

Headband & Tailbands– Headbands are coloured threads (normally mercerized cotton or silk) which are wrapped around a core of some sort (normally vellum backed with leather) and are then sewn through the signatures, filling space left between the spine and the book block. Their original purpose is to help lessen damage to the book when it is removed from a shelf by it’s headcap. It also helps to some degree in keeping the sections upright. Headbands (and tailbands) are often referred to as endbands.

Modern headbands are used for decorative purposes only and are normally glued to the top of the book block.

In the 12th and early 13th centuries, headbands were combined with a leather tab. Conventional cloth or silk headbands came later in the 16th century

- Our Headband Gallery

- Making Bookbinding Headbands Tutorial

- Making and sewing headbands Video Tutorials

Book Block or Text block – The block of internal pages that make up the book.

Spine (textblock spine) – The spine is where the signatures and textblock are bound. Usually the spine will contain important book information so it can be easily found when up on the shelf in book stores or libraries, information might include the book’s title, name of author and publishers name or logo. Also known as the back, and backbone.

A traditional sewn spine will usually be backed, glued and lined with cloth or paper.

Signatures – Signatures are stacks of two or more pieces of paper which are folded and grouped together ready for sewing. Each of the signatures are bound together individually and later bound together as a whole forming the textblock.

You will only find signatures in hard cover books. Also sometimes referred to as gatherings.

End Paper (End Sheets) – Endpapers are the first and last pages of the book which which glued to the cover boards (front and back). Often these end papers will be of heavier weight and decoratively patterned often marbled with a cloth hinge for reinforcement. Often referred to as a pastedown or end sheets; paste-down is the page which has been glued to the board and the other side is known as a free endpaper

Other than providing improved aesthetics to the internals of the book, end papers or pastedowns also help to counteract the warp of the bookbinding board which happens during the drying stage of apply the cover material.

You will often only find end papers in hard-backed books.

Internal

Leaves – Two pages of a book (1 sheet) is referred to as a leaf, front (‘recto’) and back (‘verso’).

Edges / Fore Edge – The edges of the leaves and the textblock as a whole. On more expensive books you will likely find the fore edge has been painted with a hidden painting (known as foredge painting or art) or has gilt edges (smoothed and painted, normally with gold leaf or gold paint).

- Fore-edge Painting Examples

- More Fore Edge Paining examples

- Fore-Edge Paintings: Beauty on the Edge

- Fore-edge Painting Process

- Fore-edge painting on Wikipedia

- Fore-edge painting history

Don’t forget to subscribe to our YouTube channel to get access to HD videos of hundreds of Book Binding tutorials and reviews!

Wire Lines and Chain Lines – In the early days of paper making wet pulp was laid in a kind of wire mesh frame and the water was shaken out of it, the paper made using this process was called Laid Paper. The wide-spaced lines on the frame were known as chain lines and were typically spaced about 1 inch apart; the closer spaced lines perpendicular to the chainlines were called the wirelines and were typically about 1mm apart.

On older books which used paper made via this technique you can visibly see the marks left by the wire and chain lines (see image to the right).

Today it is only very expensive paper which is made in this way, usually by hand.

- Chain and Wire Lines Info

- More info on Chain and Wire Lines

- Laid Paper Chain and Wire Line Photos

- Laid Paper on Wikipedia

Manuscript – A manuscript is generally referred to as a book that was written by hand.

To better understand the anatomy of a book you can have a look at the following book cutaways which help to further depict the internals of different types of bound books.

Photos Courtesy of Book Arts Web – http://www.philobiblon.com/bindorama13/

Photos Courtesy of Book Arts Web – http://www.philobiblon.com/bindorama13/

How to Understand Book Sizes (video)

Books come in different shapes and sizes. They can be tiny….. or massive. To make a book, the printer takes a sheet of paper and folds and cuts it a number of times to produce different sized leaves. A folio is folded once creating two leaves, while a Quarto is folded twice making four leaves. Each leaf size, and hence book size, is given a different name based on the number of folds required.

Today publishers can create a book in any size they wish but terms like Folio and Quarto are still widely used. There are dozens of formal names for book sizes but here are a few of the most commonly used ones.

- Miniature — the smallest books measuring less than 2″ in height. Often bibles were printed as miniatures so they could be easily carried, children’s books too so they could fit into small hands.

- Sexagesimo-quarto (64mo) — a book size approximately 2″ x 3″.

- Quadragesimo-octavo (48mo) — a book size approximately 2 ½” x 4″.

- Tricesimo-secondo (32mo) — a book size approximately 3 ½” x 5 ½”.

- Octodecimo (18mo) — a book size approximately 4″ x 6 ½”.

- Duodecimo (12mo) — these books measure approximately 5 ½” x 7 ½” and require four folds of a paper sheet. You will recognize this size as your typical paperback.

- Crown Octavo (8vo) — a book that is approximately 6” x 9”

- Octavo (8vo) — at roughly 6″ x 9″ tall and requiring three folds, the Octavo is a fairly standard size for small hardcover books.

- Medium Octavo (8vo) — a book that is approximately 6″ x 9 ¼”.

- Royal Octavo (8vo) — a book that is approximately 6 1/2″ x 10″.

- Imperial Octavo (8vo) — a book that is approximately 8 ¼” x 11 ½”.

- Quarto — folded twice and having a maximum size of about 9 ½” x 12″, you can tell a Quarto by its mostly squarish shape.

- Folio (Fo) — at an upward height of 12″ x 19″ the folio is a large upright-shaped book. This format often contain photos, or illustrations

- Elephant Folio (Fo) — an oversized folio book 23″ to 25″ high. Often these will be art books, or atlases, or like this one designed for teachers to read to a large group of children.

- Atlas Folio (Fo) — a book that is approximately 25” to 50” tall.

- Double Elephant Folio (Fo) – a book that is approximately 50” tall or more.

Learn more about book sizes at AbeBooks: http://bit.ly/xY96c7

– Source: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=P66e-6XoM0k

Don’t forget to subscribe to our YouTube channel to get access to HD videos of hundreds of Book Binding tutorials and reviews!

Please Support us on Patreon!

Moreover, starting with the pledge level of $3, you will get a digitized vintage book about bookbinding, book history, or book arts each month from us!

These pledges help iBookBinding to continue its work and bring more information about bookbinding and book arts to you!

- Home

- Resources

- Publishing

- Parts of Your Book

What is the beginning of a book called? What about the back of a book? Can you name at least six parts of a book?

As an author, you should have a firm grasp of what comprises a professionally made book. Including all the necessary parts of a book and putting them in the right order is the first step to making your book credible. The inside of your book, which we call the book block, is divided into three main sections: the front matter, book block text, and back matter.

You must make sure that the manuscript you submit to us includes all three sections combined into a single document and in the correct format. To give you some help, we’ve broken down all the parts of your book.

CONTENTS

Front matter

Front matter introduces your book to your readers. Appearing before the main text, it usually contains just a few pages that include the book’s title, the author’s name, the copyright information, and perhaps even a preface or a foreword. You don’t have to include all of them, though! It’s up to you to determine what’s suitable to your book.

Half Title Page

The half title page is the first page of your book and contains your title only. This page does not include a byline or subtitle. The designer will add this to your book layout.

Series Title Page

Use the second page of your book to list any of your previously published books by title. It is customary to list the books chronologically from first to most recently published. Listing the title only is standard, but in nonfiction works, you may also list the subtitle if you feel it is essential. A common way to begin this page is, «Also by [author’s name] …»

Title Page

The title page is the part of your book that shows your full book title and subtitle, your name, and any co-writer or translator. iUniverse will add its logo and locations at the bottom of the page. The designer will add this to your book layout, although if you have a specific idea of how you want this to look, you may include it.

Copyright Page

The copyright page contains the copyright notice, which consists of the year of publication and the name of the copyright owner. The copyright owner is usually the author but may be an organization or corporation. This page may also list the book’s publishing history, permissions, acknowledgments, and disclaimers.

Copyright Page

The copyright page contains the copyright notice, which consists of the year of publication and the name of the copyright owner. The copyright owner is usually the author but may be an organization or corporation. This page may also list the book’s publishing history, permissions, acknowledgments, and disclaimers.

Please note: iUniverse provides you with a standard copyright page that incorporates your individual information and the International Standard Book Number (ISBN).

(Table of) Contents

A table of contents, or simply “Contents,” is the part of a book that is usually used only in nonfiction works that have parts and chapters. A contents page is less common in fiction works but may be used if your work includes unique chapter titles. A table of contents is never used if your chapters are numbered only (e.g., Chapter One, Chapter Two). If your book requires a contents page, please make sure it lists all the chapters or other divisions (such as poems or short stories) in your manuscript. Chapter listings must be worded exactly as they are in the book itself.

Please do not include page numbers in your contents page—iUniverse will add page numbers during the formatting stage.

List of Illustrations

If your book includes several key illustrations that provide information or enhance the text in some way, consider creating a page that lists them. If this material is included simply for comic relief or as a visual aid, a page listing may not be necessary. Just as with the table of contents, you won’t need to list the page numbers.

List of Tables

If your book includes several key tables that provide information or enhance the text in some way, consider creating a page that lists them. If this material is included simply as a visual aid, a page listing may not be necessary. Just as with the table of contents, you won’t need to list the page numbers.

Foreword

The foreword contains a statement about the book and is usually written by someone other than the author who is an expert or is widely known in the field of the book’s topic. A foreword lends authority to your book and may increase its potential for sales. If you plan to include a foreword, please arrange to have it written and included in your submitted manuscript. A foreword is most commonly found in nonfiction works.

Preface

The preface usually describes why you wrote the book, what your research methods are, and perhaps some acknowledgments if they have not been included in a separate section. It may also establish your qualifications and expertise as an authority in the field in which you’re writing. Again, a preface is far more common in nonfiction titles and should be used only if necessary in fiction works.

Acknowledgments

An acknowledgments page includes your notes of appreciation to people who provided support or help during the writing process or in your writing career in general. This section may also include any credits for illustrations or excerpts if not included on the copyright page. If the information is lengthy, you may choose to put the section in the back matter, before or after the bibliography.

Introduction