Subjects>Hobbies>Toys & Games

Jbiddy ∙

Lvl 1

∙ 15y ago

Best Answer

Copy

self taught

Self taught isn’t a word though we are all entitled to our own

opinions. Try autodidact.

Wiki User

∙ 15y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What word means to teach yourself?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

Ever wanted to become a master at Excel? Or learn how to negotiate effectively? What about coding, or becoming a better writer, or learning how to edit photos?

Thanks to the internet, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

There’s a whole lot you can teach yourself these days — especially if you have access to an internet connection. You don’t need to buy fancy equipment or sign up for expensive courses to learn skills that could be invaluable to your career and your personal life.

The key is finding the educational material that’s high quality enough to be worth your time. Below, we’ve come up with a list of 13 skills you can teach yourself for free, along with resources to help you acquire those skills. Check ’em out.

1) How to negotiate better.

Whether you’re negotiating with your team to implement an idea or negotiating with your boss for a raise, negotiating skills will come in very, very handy. They’ll help you become more confident, eliminate inequalities, gain a competitive advantage, and even preserve relationships by managing conflict more effectively.

There’s a lot of reading material out there to help you become a better negotiator. If you’re looking for a few quick reads, two helpful blog posts include «How to Disagree Without Being Disagreeable: 7 Tips for Having More Productive Discussions» and «The Introvert’s Guide to Successful Negotiating.»

If you’re looking for a deeper dive, head over to the library and grab these two books: Ronald Shapiro’s «Perfecting Your Pitch: How to Succeed in Business and in Life by Finding Words That Work,» which explores the art of crafting a pitch and the importance of nuanced language, and William Ury’s «Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving,» which serves as a guide to reaching mutually beneficial agreements in any conflict.

Want to take a class? There are a few free online negotiation courses you can choose from, too.

- «Introducing the Art of Negotiation» (Alison)

- «Negotiation: Problems Solved, Not Battles Fought» (Udemy)

You can also practice negotiating for free by simply working on it in real life. Start by practicing being an active listener so that the person on the other side of the negotiation feels like you’re not only hearing them, but also understanding them. Practice feeling out the other person’s emotional state throughout the conversation and choosing your words, tone, and approach based on their emotions.

2) How to use Microsoft Excel for more than just simple tables.

Most people have some experience with Excel, whether it’s gathering ideas or making simple tables or equations. But if that’s the limit of your Excel knowledge, you’re missing out on a whole world of reporting automation that could save you hours upon hours of time.

Want to work more efficiently in Excel and avoid the tedium of updating your spreadsheets manually? There’s a lot you can learn about Excel for free online. Actually, we’ve created a whole bunch of educational content about Excel here at HubSpot. Here are a few of the best ones:

- «How to Use Excel: The Essential Training Guide for Data-Driven Marketing» (free ebook)

- «9 Excel Templates to Make Marketing Easier» (free templates)

- «How to Use Excel: 14 Simple Excel Shortcuts, Tips & Tricks» (blog post)

- «40 Handy Excel Shortcuts You Can’t Live Without» (blog post)

- «How to Create a Pivot Table in Excel: A Step-by-Step Tutorial» (video & blog post)

- «10 Design Tips to Create Beautiful Excel Charts and Graphs» (blog post)

3) How to invest your money.

Investing your money is intimidating for many reasons. First of all, the jargon is foreign. What are index funds? What’s the difference between a 401(k) and a Roth IRA? If you aren’t used to the vocabulary, it can seem pretty daunting. Secondly, the process seems super complicated and overwhelming — not to mention, painfully boring.

At the same time, most of us know it’s important to learn about savings and investment as early as possible, especially if you have a regular income.

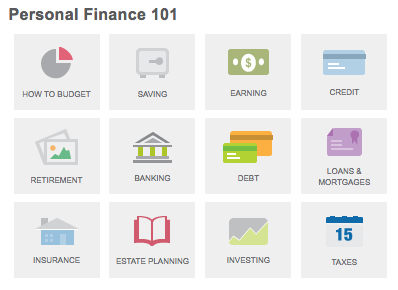

There are a lot of helpful resources out there, but I’ve found Investopedia to be especially helpful. Those folks have a ton of free online resources, including this free stocks basics course. I’ve also found LearnVest’s Knowledge Center to be particularly helpful. They have a ton of content about investing along with other personal finance topics like budgeting, saving, loans and mortgages, and so on.

Image Credit: LearnVest’s Knowledge Center

4) How to write better.

Everyone is a writer. This is especially true in our content-driven world, where we all partake in online communication of some sort on a regular basis — from writing emails to authoring blog posts to banging out a few short tweets. Plus, it turns out that there are benefits to doing a bit of freewriting in the morning.

Do you want to cut down on spelling errors and grammatical mistakes? Find your writing voice? Author your first blog post? Get better at structuring your paragraphs? Name your writing goal, and there’s probably a free resource for that.

If you’re looking to improve your writing in a more general sense, start by watching this awesome, 18-minute talk my colleague Beth Dunn gave at INBOUND a few years ago on how to become a better writer. I have this video bookmarked when I need some inspiration.

Like Beth says in her talk, the best way to get better at writing is by practicing. Every day. You can certainly use good ol’ pen and paper to practice, but there are also some great writing prompts apps that’ll give you jumping-off points for a piece. While some of them cost a buck or two (like Prompts and Writing Challenge), there are some free ones out there. Grid Diary, for example, is good for folks who want to write something down in a diary-like format, asking questions like, «What did I do for my family today?» and «How can I make tomorrow better?» (For more tools, check out this list of 31 online tools for improving your writing.)

Looking for a deeper dive into improving your writing? Download our free ebook, «The Marketer’s Pocket Guide to Writing Well,» for free tips on how to become a better writer. You might also check out Macalester College’s lecture series on writing well for full videos on topics like sentence structure, how to write intro paragraphs, how to engage readers, and so on.

Finally, if you’re more interested in cutting back on spelling and grammatical errors, try out the free Hemingway web app. Once you’ve written something down, paste your text into this app and it’ll assess how readable your writing is, as well as identify opportunities to make it simpler.

Here are a couple more grammar- and spelling-related resources that might be helpful, too:

- «Grammar Police: 25 of the Most Common Grammatical Errors We All Need to Stop Making» (blog post)

- «How to Spell Words You Don’t Know: Techniques From Grammar Experts» (infographic)

5) How to read faster.

Thanks (yet again) to our content-driven world, many of us find ourselves with a list of books we want to read, training we need to complete, and news we need to «stay on top of» every single day. For slow readers like myself, getting through all of this material — and retaining the information from it — can be a huge struggle. How on earth do I get better at skimming?

Turns out, reading faster often means changing the way you read. I, for example, have gotten into the habit of sounding out each word in my head. Without a concerted effort on my part, I’ll never be able to get out of that habit.

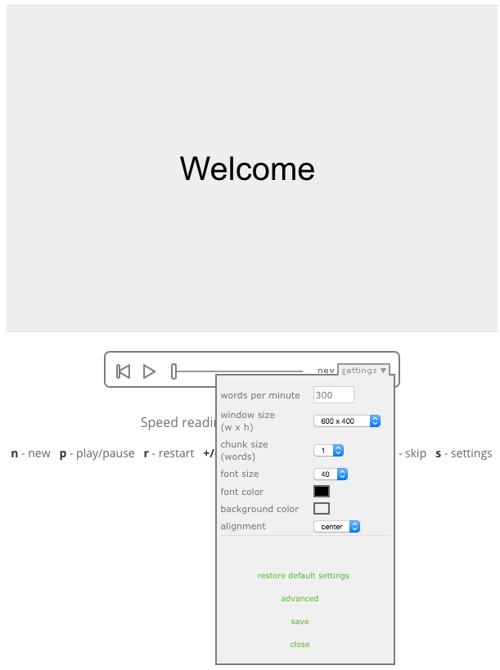

Luckily, there are places online that’ll teach you how to read faster and help you practice on a regular basis. Spreeder, for example, is a free online program that claims it can help people learn to to double, triple, or even quadruple the speed at which they read passages. Simply paste the text you want to read in the text box, choose your settings (like how fast words are flashed, and how many words are flashed at a given time), and press «play.» From there, the app will flash one or more words on the screen at whatever pace you choose.

Once you’ve gotten used to the app, you’ll want to practice speed reading «in the wild,» which you can also do for free using all the content that’s out in the world already. (Remember, improving your reading speed will take time.) Start with easier reading material, like blog posts and short articles. If you’re reading print, use your finger or a pen or index card to set the pace.

6) How to type faster.

If you don’t know how to touch type (i.e. type without looking at the keys), then trust me: It’s worth learning. Think about how much typing you do in a day, and then think about how much faster you’d get things done if you could speed that up. Overall, it’s a skill that will make you much, much more productive.

I’ve spent far too much time playing online typing games and trying to beat my words-per-minute records. There are a lot of typing games out there, but Sense-Lang’s Balloon Typing Game is one of the simplest. In the game, balloons with letters on them float down your screen, and your job is to burst them by hitting the right key before they reach the bottom. If you’re looking for more of a challenge, check out their car racing game.

7) How to take beautiful photos.

You don’t need to take an expensive photography course to learn how to take beautiful photos. In fact, you don’t even need a fancy camera — all it really takes is a smartphone camera, a good subject, and the patience to learn some specific photo-taking techniques.

For example, learning to place the subjects in certain parts of your photos can go a long way to make your photo appear more balanced. The rule of thirds says to break an image down into thirds, both horizontally and vertically (so you have nine parts in total), and then place points of interest in these intersections or along the lines.

To make this easier, turn on gridlines on your phone by following these steps:

- iPhone: Go to «Settings,» choose «Photos & Camera,» and switch «Grid» on.

- Samsung Galaxy S5: Launch the camera app, go to «Settings,» scroll down and tap «Gridlines on.»

Image Credit: Lynda.com

Read through these 17 tips for taking great photos with your smartphone to learn more about how to line up your shots, find interesting perspectives, and take advantage of symmetry, patterns, «leading lines,» and more. Then, get in the habit of taking photos on a regular basis to practice.

How to edit those photos.

How to edit those photos.

Once you’ve taken a good photo, don’t just call it a day. Learning how to edit those photos can take them from good to great — and you don’t need fancy editing software. There are plenty of free photo editing apps out there.

- VSCO Cam (free on iOS and Android) is a great choice for editing photos on-the-go, especially if all you want to do is slap on a filter. Their filters have more of a softer, authentic look that resembles real film, as compared with the over-saturated looks of many Instagram filters.

- Snapseed (also free on iOS and Android) is another solid app for doing some basic image enhancements like tuning, cropping, and straightening.

- You can also do wonders for an image simply by editing it in the Instagram app — which is also free. (Read this blog post for step-by-step instructions on how to edit a photo using Instagram.)

Want to edit your photo using Adobe Photoshop? If you don’t already own Photoshop, you can try it for free before you commit. And if you want to learn how to use it, you can also do that for free.

- Here’s a great introductory post from Adobe Support on how to edit your very first photo in Photoshop.

- Here’s a library of 45 Photoshop tutorials — everything from how to create a «soft haze» effect to how to create a faded film look.

- Here’s a free Photoshop tutorial for beginners from HubSpot, which covers 12 of the most useful tools in Photoshop and explains what they do, where to find them, how to use them, and a few tips and tricks for getting the most out of them.

9) How to code.

Nowadays, learning the basics of coding is a huge advantage for marketers, entrepreneurs, and other folks in the business world. Even if you don’t have to do a lot of hard coding yourself, knowing the basics will help empower you to make quick fixes, and help you communicate effectively with developers when you do need help with something.

While there are plenty of coding courses and bootcamps out there that costs hundreds or even thousands of dollars, there are plenty of free online resources you can use to teach yourself.

- Codecademy is a longtime favorite for beginners because it teaches you how to code interactively, and really holds your hand through the learning process.

- Coursera also has a number of free introductory programming courses from universities like University of Washington, Stanford, the University of Toronto, and Vanderbilt.

- The online learning platform Udemy has some free programming courses that are taught via video lessons, like «Programming for Entrepreneurs — HTML & CSS» or «Introduction to Python Programming.»

If you’re just looking for a quick overview of how HTML, CSS, and/or JavaScript work, start by reading this blog post that covers the basics of how these three programming languages work.

10) How to implement inbound marketing.

Gaining some real, in-depth marketing knowledge definitely doesn’t require signing up for an expensive marketing course. There are tons of free resources out there that’ll teach you about everything from the basics for developing a customer-centric inbound strategy, to detailed instructions about how to build an optimized landing page.

Start by heading over to HubSpot Academy, which has a wealth of free resources. The inbound marketing certification course, for example, is a free marketing training course that covers how SEO, blogging, landing pages, lead nurturing, conversion analysis, and reporting come together to form a modern inbound marketing strategy. There are also a whole bunch of helpful training videos on topics like buyer personas, content creation, and more.

You can also get a Google Analytics certification for free by taking Google’s GA proficiency course online, and then passing the Google Analytics IQ exam.

To stay on top of marketing trends and news, you might also subscribe to a handful of marketing blogs. Some of our favorites include Unbounce, CrazyEgg, KISSMetrics, Content Marketing Institute, CopyBlogger, and Search Engine Land. (And HubSpot, of course.)

11) How to read and speak in a foreign language.

While it might take years to become totally fluent in a foreign language, you can get pretty close simply by teaching yourself regularly over a long period of time. And you can do it for free.

If you want to learn the old-fashioned way, you might go to your local library to look for language instruction books you can take out and use without having to buy them.

If you prefer going the app route, DuoLingo (free on iOS and Android) is a language-learning app that actually makes the process fun. Each lesson is short, painless, and super visual. Slate even called it «the most productive means of procrastination I’ve ever discovered.» Plus, the listening components make it great for learning pronunciation — even on-the-go.

Another simple hack to keep that new language top-of-mind? Simply change your phone and computer interface languages to the foreign language you’re learning. (Just make sure you know how to navigate to change the settings back.)

- iPhone: Open the «Settings» app, and choose «General.» Choose «Language & Region» and tap on «iPhone Language.» Then, select the language you want to change the iPhone to, and confirm.

- Android: Open the «Settings» app and select «Languages & input.» Select the «Language» option and select the language you want to change your Android device to.

Teaching yourself language skills will only get you so far, though. If you want to practice with other humans (and you live in a city), consider joining language-specific gatherings via Meetup.com, which are volunteer-driven and therefore totally free.

12) How to become a better public speaker.

Did you know that public speaking is the number one fear in America, beating out heights, bugs, and snakes? Whether you share that fear or just want to become a better public speaker, I have good news for you: There’s a lot you can do to improve those skills for free, without textbooks or public speaking classes. Here are a few places to start:

- «A Helpful Guide of Public Speaking Tips» (infographic)

- «The Uneasy Speaker’s Guide to Confident Public Speaking» (blog post)

Want to see how you look when giving a presentation? Knovio is a cool, free app that lets you upload your presentation slides and then record yourself giving the presentation using the camera on your computer or smartphone. You can either review the video yourself, or share it with coworkers or friends for feedback by posting your Knovio presentation to YouTube, Vimeo, or simply emailing it out.

As with learning languages, teaching yourself public speaking skills will get you to a certain point. Try joining a public speaking group via Meetup.com to practice in front of others.

13) How to meditate.

You might be thinking to yourself: Meditation isn’t a business skill! Not so fast, my friend. Turns out starting your day off with a quick meditation session can make you more productive throughout the rest of the day. According to a 2012 study, people who mediated «stayed on tasks longer and made fewer task switches, as well as reporting less negative feedback after task performance.»

Not sure how to meditate? There are a slew of resources online that’ll teach you how to meditate for free. My personal favorite is Headspace, an app that gives you 10 free guided meditation sessions. If you’d rather not pay the monthly subscription fee after that, then try the free guided meditation sessions on UCLA Health that range from three minutes to 20 minutes in length. Here are some more free guided meditation sessions from Fragrant Heart if you can’t get enough.

What other skills can you teach yourself for free? Share them with us in the comments.

Are you wondering how to learn a language by yourself? Or finding the best way to learn a language?

Then you have come to the right place.

Table of Content

- My story of learning Spanish in Chile, South America

- Why should you learn a foreign language

- What is language learning? Is it hard to learn a new language?

- My 24 best tips for learning a language by yourself

- Download pdf

- Further Reading

First, let me tell you my story of learning Spanish in Chile so that you know you can learn a language on your own.

Before traveling to Chile, I couldn’t speak Spanish and wondered how I was going to survive in a predominantly Spanish continent. I assumed that Latin Americans would make my life easy by talking to me in English.

But neither the Latinos nor the foreigners living in Chile spoke English, at least not as much as I expected. That’s when I realized I had to learn Spanish. Reality hit me hard, and I prayed for survival.

Learning Spanish in Chile, a country notorious for bad Spanish, wasn’t easy. I struggled to make my way around Chile from morning until night. I couldn’t understand the conversations on the dining table and longed to participate. I missed cracking jokes. I wanted to cry.

Words fell on my ears but my brain couldn’t comprehend them.

Rather than pitying myself, I decided to learn enough Spanish to understand the people around me and reply. So that’s what I did. From speaking incorrect Spanish unabashedly to practicing Spanish grammar with workbooks, I tried all ways to learn a language.

Fast forwards a few weeks, I started speaking Spanish fluently. I was still a foreigner in Chile, but as I began to understand more Spanish, I became a part of the Chilean host family. We woke up, greeted each other by kissing both cheeks, ate toast with avocados and Nescafe coffee, and talked about life at supper or the evening Once.

I had a second home now just because I could converse in Spanish.

Related read: Most Common Spanish phrases that you would need to travel in South America.

Now when you know that you can teach yourself a language, let us come to the next question.

Why should you learn a foreign language?

Do you want to travel or study abroad? Or maybe you want to work or volunteer in a different country?

Language is the brain and heart of every community. If you want to become a part of another culture and assimilate with people at the other end of the world, you will have to converse in their language else you wouldn’t understand their lives and would always remain a foreigner.

To survive or to feel at home anywhere, invest time in learning a foreign language. A new language also aids developing personally because a new culture and new means of communications open us up.

If you have the right motivation, you can learn a language on your own.

What is language learning? Is it hard to learn a new language?

Language is not only its words and grammar. Language consists of slang, local dialects, the speed and rhythm with which its spoken, abbreviations, and idioms which people use. Understanding all these dimensions of a language in addition to learning its vocabulary and speaking the right words is what learning a language means.

But now you can imagine that learning a language by yourself can be hard.

Teaching myself Spanish was a challenging task. I studied Spanish every day and talked to locals so that I could speak the language colloquially.

When people heard me converse in Spanish after a few months of my stay in Latin America, they thought that I had been speaking for years and refused to believe that I did not speak Spanish before traveling to the continent. From blankly watching my Chilean friends’ faces to making the same friends laugh and run behind me as I pulled their legs in Spanish, I went through an incredible language learning journey.

In this “how to learn a foreign language on your own” guide, I list all the best ways to learn a new language that I have collected from my personal experience of mastering Spanish in a few weeks. I promise that my language learning tips will help, but you would need a motivation to learn a language for it is not an easy task.

The Internet has a plethora of language learning apps and tutorials. Memrise is one of my favorite apps to learn and play around with a new language. Irrespective of which ones you pick, use these ways to learn a foreign language.

Let’s get you started with a new language.

Here is a downloadable pdf of this guide in case you wish to print it.

My 24 best tips for learning a new language by yourself.

1. Find a native speaker of the language

This is the first step of how to learn any language.

The need to speak the language is the biggest push to learn another language. I could speak Spanish in a few weeks because I was surrounded by people who only spoke Spanish and I had to talk to them. But I cannot still talk in Kannada, the local language of Bangalore, because almost everyone in Karnataka speaks Hindi or English.

If you have to talk to a native speaker, you will not only have a necessity to speak the target language, but you will also have access to someone who knows the language thoroughly. Talking to a native speaker will make you think in the language you want to learn.

But how will you find a native speaker?

Many people, like you, want to learn new languages, and you can have a language exchange with these language aspirants. You can easily find a native of the target language with one of the many free or budget-friendly online language learning applications and websites.

Some of the sites which offer language exchanges are iTalki, My Language exchange, Couch Surfing(look for coffee and conversation in the same city), The Mixxer, Polyglot club, LingoGlobe, SprachDuo, and Verbling.

Most of these language learning websites let you connect with learners on the go, some allow scheduling a session, and a few even have other language learning resources.

You can also find people who want to learn the same language in meetups in your city or on social media. Use Skype or any other voice over call media and get started.

For the rest of the article let us assume that you are either in the country of the target language or you can speak to at least one native speaker of that language regularly.

2. Watch and listen to the native speaker speaking the target language

When I started learning Spanish, I watched my Latin-American friends carefully whenever they spoke. At one point, they even got conscious of my constant staring. But by observing the way they spoke Spanish or pronounced certain words, I absorbed the nuances of South-American Spanish, without even knowing.

Pay attention to how people greet each other, how do they wish good morning and goodbye, what do they say when they overeat or are late for a party, the speed with which they speak, the sounds they make, et cetera.

Listen and observe, as much as you can. Soon you would start speaking at least some words of the language you want to learn with the correct accent and sounds.

3. Start speaking the foreign language

If you ask me what is the best way to learn a new language, I will tell you to start speaking in the language as soon as you can.

Start speaking the language irrespective of incorrect grammar, incomplete sentences, missing articles, and an awkward accent. Don’t be embarrassed or hide behind the convenience of not knowing the foreign language.

If you don’t have anyone to listen to you, just record an audio message and play it later for your language partner.

Once you overcome the inertia against speaking a new language, you are on the right steps to learning a language.

4. Use facial expressions, point at objects, and act with hands if you don’t find the right words

Sometimes when I had finished speaking a Spanish sentence, I used to create sinusoidal waves going to the left with my hands. The waves signified that what I said had happened in the past, for I didn’t know the past tenses in Spanish until then.

Either you can blankly stare or pick up a pen to show that you need stationery. If you want to ask your language partner if he had food, find the right sign language.

You get the idea.

Design your own hand movements and facial expressions to add to the broken conversation. Your gestures will aid the conversation, and the person with whom you are speaking would be more willing to help you learn the language.

5. If you want to learn a language quickly, you can’t be shy

Draw those curtains of shame. You would never learn otherwise.

I knew foreign volunteers in Chile who could not speak Spanish even by the end of our four months English teaching program as they were too shy to say anything beyond a hola. You have to face the fear of speaking incorrectly and have to keep aside the embarrassment to learn a language fast.

Remember — even if you don’t speak, people know that you don’t know their language. Then what are you hesitant about?

Related Read: 15 things we can care less about

6. Label objects with their names in the language you are learning

Dr. Kenneth Higbee, memory expert and author of the book Your Memory: How It Works and How to Improve It, tells: It is the disorganization in your mind, not the amount of material, that hinders memory.

Label all your home and office objects that you can put a sticker on. When you will look at the new words frequently, they will get added to your vocabulary. You can buy the labels of any language online. Here are some Spanish ones that I really liked.

Label objects, and notice yourself stutter how you forgot huevos (eggs) while walking back home from work.

7. Practice the basic grammar rules from a grammar book — One of the crucial steps to learn a new language

My English-teaching volunteer program gave me a Spanish workbook which expedited my Spanish learning process. Apart from explaining the basic grammar of Spanish, the book also listed easily confused words, false friends, and incorrectly used verbs.

I practiced grammar exercises and discussed them with friends every day. By reading and writing the words and resolving my doubts with the native speakers, I laid a strong Spanish foundation.

Find a grammar book of the language you are studying. Then start practicing grammar rules from it one by one. Live with present tense, then accept past, and then prepare for the future. Explore a few regular and irregular verbs every day. Learn to modify the tense form of verbs.

Buy a practice book and study like a child. When you write a word or a sentence correctly in five attempts, the chances of you getting it wrong would be close to zero. You will be able to think the right tense for the verb while speaking because you had practiced the tenses and their rules.

Find some grammar books of the most popular foreign languages to learn here. And this French grammar book almost makes me want to learn French.

8. Clear your doubts

Whenever I thought my host mother was going to thrash me for confusing between the Spanish words for snowy (nevado) and clouded (nublado), she explained even better. People have much more patience than we credit them for.

Ask questions from your language exchange partner or in meetups and online forums. Your interest and resilience increase others’ motivation to help you.

9. Watch movies and TV shows in the foreign language you want to learn

— My answer to how to teach yourself a language with fun.

I can’t remember how many telenovelas I watched while I was on my South America travel trip. What was the master plan of the vamp in ‘Te Doy La Vida’, what time was ‘A Corazón Abierto’ telecasted, and what was the wicked lady in ‘La Raina del Sur’ planning to do next were on my fingertips. But also some of the words and phrases the characters spoke and how they spoke them.

Watching the TV shows and the cinema of the target language is not only a way to practice the language, but you can also learn a lot about the culture even before you travel to the country. While having fun, you develop your vocabulary, pick up the colloquial words, gestures, and accents.

As you hear more people speak the language, you also start thinking in the language, thus eventually speaking it and understanding it better. Try some newly-learned phrases on your language-exchange friend and see how she reacts.

10. Understand the concepts of the language rather than learning the phrases

When my Chilean friend said good morning to a school colleague, I learned the phrase and repeated it the next time I met my friend. She laughed. I hadn’t replaced the “he” with “she.”

You can learn the solution to one linear equation in Mathematics but to solve another, you need to know the concept. Don’t memorize the answer; understand the steps. You can then modify the language and use it as per your convenience.

Here comes the grammar books again. You might want to try some funny grammar workbooks, too.

11. Don’t leave even a single chance to practice the language you want to learn — Force yourself to think in the new language.

I recited the recipe of an Indian curry to my host mother because I wanted to learn the utensils’ and spatula names. Our conversation was hilarious.

Watch a Bollywood movie with your target language subtitles. Find a recipe you want to cook in the language you want to learn. Change the language of your phone and computer to the target language. Search for popular podcasts.

The more you have to see and understand the new language, the more you will think in the language.

12. Write in the language — One of the well-proven language learning methods.

Take small notes. Write your dreams. List numbers.

Once you start writing in the target language, you will never forget the words that you wrote down.

13. Listen to Audio lessons of the target language

Almost all the languages have online podcasts to which you can tune into and keep listening. The podcasts are a combination of audio lessons, dialogues, tips, and tricks. I am thinking about purchasing this Spanish one just for fun.

Listening to someone speak to us is sometimes more impactful than reading ourselves.

14. Keep translation applications handy

Google Translate and Spanish Dict were like those emergency phone calls back home that you make when you are cooking paneer butter masala, and you can’t remember whether you add cream before or after adding the tomatoes.

Translation applications are handy while directing a taxi, shopping, or during a conversation. But if you have some free time, you can use the applications to learn new words by translating whatever comes to your mind.

Translation applications aren’t perfect, but they are good to learn the basics of a new language.

15. Know the right order of learning — One of the many secrets on how to learn a language fast.

Before traveling to Latin America, I tried learning Spanish with DuoLingo but the application proved useless. The course started with greetings, a few words from the everyday vocabulary, how are you, and that’s about it. It never came to daily conversations.

The right order of learning is important.

Start learning a language with greetings, then daily routine questions such as did you eat lunch or want a cup of tea — these everyday conversations would ease your way into the language slowly and naturally.

Then come numbers, time, pronouns, introductory phrases, routine verbs such as to be, need, want, say, come, go, have, eat, drink, party, read, learn, forget, watch, work, live, see, sit, sleep, shower, wash, clean.

Relations, surrounding objects, seasons, places, temperature, professions, come next.

Start with less. When I started speaking Spanish, I used to thrust out a string of jumbled words without articles, pronouns, and right tenses. Then I started adding these missing constructors one by one.

Choose an online tutorial or application that respects the order of learning foreign languages. If you are feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of tasks or phrases on the first few days of your learning a new language, you might want to switch to a different application.

I didn’t like DuoLingo, but Memrise seems promising. Here is a complete Spanish step by step book.

16. Read a foreign language book aloud — One of the very under-rated steps of language teaching.

By reading aloud you can practice the sounds, accents, and the pronunciations of the target language. Just pick up a book or an article on the internet and read it loudly as if you are narrating it to someone.

The more you practice speaking words of the new language, the more confident you will be to use the language in public or with your language partner.

17. Write the phonetics of the foreign language words in your native language

I used to write down the phonetics of the Spanish words in Hindi to remember the correct Spanish pronunciation. Even today when I get confused on how to pronounce a Spanish word, I dig into my hilarious notes that only I can understand.

Ask your language exchange partner to enunciate the word for you. You can also listen to the correct pronunciation by playing the Google Translate voice feature or even Memrise tutorials introduce new words in audio formats. Then write down the phonetics in your native language and refer to them whenever you need.

You can learn the correct sounds of the new language if you know the right phonetics.

Helpful read if you are learning Spanish: Important phrases of Spanish with Hindi and English Phonetics

18. Don’t be lazy — Sadly the quickest way to learn a language

Learning a language is a lot of work but extremely rewarding activity.

When you start speaking a foreign language, you have found another culture that you can become part of. As I said before, find the right motivation. And don’t give up.

A helpful read: Tips on making an efficient daily routine

19. Focus on details

In Yoga, we correct ourselves little by little to get the perfect posture.

Similarly, when you start learning another language, you would be far from perfect. But learn from your mistakes. Focus on details to slowly improve your language skills.

Teaching yourself a new language is a process. Notice, listen, think, repeat, write, improve, repeat.

20. Don’t get offended if a native speaker corrects you.

Learning the colloquial nuances of a language is an art. You can only speak a language like its native speakers if you talk to them and let them correct you. But if you get offended, people would not point out your mistakes, and that is the last thing you want.

If you are attentive, you grasp the accent, appropriate words, modifications, speed, and idioms. These amalgamate you with the people. I have seen truck drivers, who let me hitchhike, light up as I referred to them as Caballero (gentlemen). Or women gleaming with pride as I complimented their cheese empanadas with Spanish idioms.

But for colloquial learning, you can’t get angry. Please keep your ego on the side while teaching yourself a language.

Also Read: Why are human relationships important and how to create them

21. Crack jokes to test your progress

If your language partner or meet up friends, laugh at your jokes, you are making progress.

Cracking funny jokes in a foreign language shows that you understand the language and its philosophy.

22. Be patient — Fastest way to learn a language

The appropriate greeting, the accent, and the right grammar won’t come in a few days or even in a few weeks.

We all learn at our own pace. Be easy on yourself, and take a break sometimes. Enjoy the language learning journey for the process is always more important than the result.

23. If you are studying a foreign language, be prepared to feel like an idiot sometimes

Once at a pharmacy in Santiago, I realized that I had not practiced the Spanish words for sanitary napkins. I stood there staring at the pharmacist as if I was trying to recall a complex chemical equation. Believe me; it gets worse.

Don’t think that you are forced to learn a language. Instead, embrace that you are learning a new thing, voluntarily, and have fun with it.

You would pull your hair — more than you imagined. Pour a glass of wine and Netflix.

Or try these fun language learning books along with some short story collections.

24. Conversation. Conversation. Conversation — The most effective way to learn a language

I took a French course in college, but I cannot speak any French as I never practiced it. But I spoke as much Spanish as I could while I was exploring South America, and I speak fluent Spanish even two years later.

Jump at every chance of conversation in the foreign language or create your own reasons.

Your hard work to learn a language would pay off. You would be able to travel the world and work wherever you want to. People would remember your timely jokes and your kind words even years after you have left their country.

Learn a foreign language and get to know some strangers. Good luck.

Download: Remember to download the pdf version of this “How to learn a new language by yourself” guide if you want to read and refer to the guide later.

Further Reading: My incredible journey of learning Spanish in South America

Like my guide? Please pin it and share it with the world.

Do you now know how to learn a language on your own? Feel free to ask your questions in the comments.

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter «Looking Inwards»!

In this piece Mark K Smith explores the nature of teaching – those moments or sessions where we make specific interventions to help people learn particular things. He sets this within a discussion of pedagogy and didactics and demonstrates that we need to unhook consideration of the process of teaching from the role of ‘teacher’ in schools.

contents: introduction • what is teaching? • a definition of teaching • teaching, pedagogy and didactics • approaching teaching as a process • structuring interventions and making use of different methods • what does good teaching look like? • conclusion • further reading and references • acknowledgements • how to cite this piece

Linked piece: the key activities of teaching

A definition for starters: Teaching is the process of attending to people’s needs, experiences and feelings, and intervening so that they learn particular things, and go beyond the given.

Introduction

In teacher education programmes – and in continuing professional development – a lot of time is devoted to the ‘what’ of teaching – what areas we should we cover, what resources do we need and so on. The ‘how’ of teaching also gets a great deal of space – how to structure a lesson, manage classes, assess for learning for learning and so on. Sometimes, as Parker J. Palmer (1998: 4) comments, we may even ask the “why” question – ‘for what purposes and to what ends do we teach? ‘But seldom, if ever’, he continues: ‘do we ask the “who” question – who is the self that teaches?’

The thing about this is that the who, what, why and how of teaching cannot be answered seriously without exploring the nature of teaching itself.

What is teaching?

In much modern usage, the words ‘teaching’ and ‘teacher’ are wrapped up with schooling and schools. One way of approaching the question ‘What is teaching?’ is to look at what those called ‘teachers’ do – and then to draw out key qualities or activities that set them apart from others. The problem is that all sorts of things are bundled together in job descriptions or roles that may have little to do with what we can sensibly call teaching.

Another way is to head for dictionaries and search for both the historical meanings of the term, and how it is used in everyday language. This brings us to definitions like:

Impart knowledge to or instruct (someone) as to how to do something; or

Cause (someone) to learn or understand something by example or experience.

As can be seen from these definitions we can say that we are all teachers in some way at some time.

Further insight is offered by looking at the ancestries of the words. For example, the origin of the word ‘teach’ lies in the Old English tæcan meaning ‘show, present, point out’, which is of Germanic origin; and related to ‘token’, from an Indo-European root shared by Greek deiknunai ‘show’, deigma ‘sample (http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/teach).

Fostering learning

To make sense of all this it is worth turning to what philosophers of education say. Interestingly, the question, ‘What is teaching?’ hasn’t been a hotbed of activity in recent years in the UK and USA. However, as Paul Hirst (1975) concluded, ‘being clear about what teaching is matters vitally because how teachers understand teaching very much affects what they actually do in the classroom’.

Hirst (1975) makes two very important points. For him teaching should involve:

- Setting out with the intention of someone learning something.

- Considering people’s feelings, experiences and needs. Teaching is only teaching if people can take on what is taught.

To this we can add Jerome Bruner’s insights around the nature of education, and the process of learning and problem solving.

To instruct someone… is not a matter of getting him to commit results to mind. Rather, it is to teach him to participate in the process that makes possible the establishment of knowledge. We teach a subject not to produce little living libraries on that subject, but rather to get a student to think mathematically for himself, to consider matters as an historian does, to take part in the process of knowledge-getting. Knowing is a process not a product. (1966: 72)

We can begin to weave these into a definition – and highlight some forms it takes.

A definition: Teaching is the process of attending to people’s needs, experiences and feelings, and intervening so that they learn particular things, and go beyond the given.

Interventions commonly take the form of questioning, listening, giving information, explaining some phenomenon, demonstrating a skill or process, testing understanding and capacity, and facilitating learning activities (such as note taking, discussion, assignment writing, simulations and practice).

Let us look at the key elements.

Attending to people’s feelings, experiences and needs

Considering what those we are supposed to be teaching need, and what might be going on for them, is one of the main things that makes ‘education’ different to indoctrination. Indoctrination involves knowingly encouraging people to believe something regardless of the evidence (see Snook 1972; Peterson 2007). It also entails a lack of respect for their human rights. Education can be described as the ‘wise, hopeful and respectful cultivation of learning undertaken in the belief that all should have the chance to share in life’ (Smith 2015). The process of education flows from a basic orientation of respect – respect for truth, others and themselves, and the world (op. cit.). For teachers to be educators they must, therefore:

- Consider people’s needs and wishes now and in the future.

- Reflect on what might be good for all (and the world in which we live).

- Plan their interventions accordingly.

There are a couple of issues that immediately arise from this.

First, how do we balance individual needs and wishes against what might be good for others? For most of us this is probably something that we should answer on a case-by-case basis – and it is also something that is likely to be a focus for conversation and reflection in our work with people.

Second, what do we do when people do not see the point of learning things – for example, around grammar or safety requirements? The obvious response to this question is that we must ask and listen – they may have point. However, we also must weigh this against what we know about the significance of these things in life, and any curriculum or health and safety or other requirements we have a duty to meet. In this case we have a responsibility to try to introduce them to people when the time is right, to explore their relevance and to encourage participation.

Failing to attend to people’s feelings and experiences is problematic – and not just because it reveals a basic lack of respect for them. It is also pointless and counter-productive to try to explore things when people are not ready to look at them. We need to consider their feelings and look to their experiences – both of our classroom or learning environment, and around the issues or areas we want to explore. Recent developments in brain science has underlined the significance of learning from experience from the time in the womb on (see, for example Lieberman 2013). Bringing people’s experiences around the subjects or areas we are looking to teach about into the classroom or learning situation is, thus, fundamental to the learning process.

Learning particular things

Teaching involves creating an environment and engaging with others, so that they learn particular things. This can be anything from tying a shoe lace to appreciating the structure of a three act play. I want highlight three key elements here – focus, knowledge and the ability to engage people in learning.

Focus

This may be a bit obvious – but it is probably worth saying – teaching has to have a focus. We should be clear about we are trying to do. One of the findings that shines through research on teaching is that clear learning intentions help learners to see the point of a session or intervention, keep the process on track, and, when challenging, make a difference in what people learn (Hattie 2009: location 4478).

As teachers and pedagogues there are a lot of times when we are seeking to foster learning but there may not be great clarity about the specific goals of that learning (see Jeffs and Smith 2018 Chapter 1). This is especially the case for informal educators and pedagogues. We journey with people, trying to build environments for learning and change, and, from time-to-time, creating teaching moments. It is in the teaching moments that we usually need an explicit focus.

Subject knowledge

Equally obvious, we need expertise, we need to have content. As coaches we should know about our sport; as religious educators about belief, practice and teachings; and, as pedagogues, ethics, human growth and development and social life. Good teachers ‘have deep knowledge of the subjects they teach, and when teachers’ knowledge falls below a certain level it is a significant impediment to students’ learning’ (Coe et. al. 2014: 2).

That said, there are times when we develop our understandings and capacities as we go. In the process of preparing for a session or lesson or group, we may read, listen to and watch YouTube items, look at other resources and learn. We build content and expertise as we teach. Luckily, we can draw on a range of things to support us in our efforts – video clips, web resources, textbooks, activities. Yes, it might be nice to be experts in all the areas we have to teach – but we can’t be. It is inevitable that we will be called to teach in areas where we have limited knowledge. One of the fascinating and comforting things research shows is that what appears to count most for learning is our ability as educators and pedagogues. A good understanding of, and passion for, a subject area; good resources to draw upon; and the capacity to engage people in learning yields good results. It is difficult to find evidence that great expertise in the subject matter makes a significant difference within a lot of schooling (Hattie 2009: location 2963).

Sometimes subject expertise can get in the way – it can serve to emphasize the gap between people’s knowledge and capacities and that of the teacher. On the other hand, it can be used to generate enthusiasm and interest; to make links; and inform decisions about what to teach and when. Having a concern for learning – and, in particular, seeking to create environments where people develop as and, can be, self-directed learners – is one of the key features here.

Engaging people in learning

At the centre of teaching lies enthusiasm and a commitment to, and expertise in, the process of engaging people in learning. This is how John Hattie (2009: location 2939) put it:

… it is teachers using particular teaching methods, teachers with high expectations for all students, and teachers who have created positive student-teacher relationships that are more likely to have the above average effects on student achievement.

Going beyond the given

The idea of “going beyond the information given” was central to Jerome Bruner’s explorations of cognition and education. He was part of the shift in psychology in the 1950s and early 1960s towards the study of people as active processors of knowledge, as discoverers of new understandings and possibilities. Bruner wanted people to develop their ability to ‘go beyond the data to new and possibly fruitful predictions’ (Bruner 1973: 234); to experience and know possibility. He hoped people would become as ‘autonomous and self-propelled’ thinkers as possible’ (Bruner 1961: 23). To do this, teachers and pedagogues had to, as Hirst (1975) put it, appreciate learner’s feelings, experiences and needs; to engage with their processes and view of the world.

Two key ideas became central to this process for Jerome Bruner – the ‘spiral’ and scaffolding.

The spiral. People, as they develop, must take on and build representations of their experiences and the world around them. (Representations being the way in which information and knowledge are held and encoded in our memories). An idea, or concept is generally encountered several times. At first it is likely to be in a concrete and simple way. As understanding develops, it is likely to encountered and in greater depth and complexity. To succeed, teaching, educating, and working with others must look to where in the spiral people are, and how ‘ready’ they are to explore something. Crudely, it means simplifying complex information where necessary, and then revisiting it to build understanding (David Kolb talked in a similar way about experiential learning).

Scaffolding. The idea of scaffolding (which we will come back to later) is close to what Vygotsky talked about as the zone of proximal development. Basically, it entails creating a framework, and offering structured support, that encourages and allows learners to develop particular understandings, skills and attitudes.

Intervening

The final element – making specific interventions – concerns the process of taking defined and targeted action in a situation. In other words, as well as having a clear focus, we try to work in ways that facilitate that focus.

Thinking about teaching as a process of making specific interventions is helpful, I think, because it:

Focuses on the different actions we take. As we saw in the definition, interventions commonly take the form of questioning, listening, giving information, explaining some phenomenon, demonstrating a skill or process, testing understanding and capacity, and facilitating learning activities (such as note taking, discussion, assignment writing, simulations and practice).

Makes us look at how we move from one way of working or communicating to another. Interventions often involve shifting a conversation or discussion onto a different track or changing the process or activity. It may well be accompanied by a change in mood and pace (e.g. moving from something that is quite relaxed into a period of more intense activity). The process of moving from one way of working – or way of communicating – to another is far from straightforward. It calls upon us to develop and deepen our practice.

Highlights the more formal character of teaching. Interventions are planned, focused and tied to objectives or intentions. Teaching also often entails using quizzes and tests to see whether planned outcomes have been met. The feel and character of teaching moments are different to many other processes that informal educators, pedagogues and specialist educators use. Those processes, like conversation, playing a game and walking with people are usually more free-flowing and unpredictable.

Teaching, however, is not a simple step-by-step process e.g. of attending, getting information and intervening. We may well start with an intervention which then provides us with data. In addition, things rarely go as planned – at least not if we attend to people’s feelings, experiences and needs. In addition, learners might not always get the points straightaway or see what we are trying to help them learn. They may be able to take on what is being taught – but it might take time. As a result, how well we have done is often unlikely to show up in the results of any tests or in assessments made in the session or lesson.

Teaching, pedagogy and didactics

Earlier, we saw that relatively little attention had been given to defining the essential nature of teaching in recent years in the UK and North America. This has contributed to confusion around the term and a major undervaluing of other forms of facilitating learning. The same cannot be said in a number of continental European countries where there is a much stronger appreciation of the different forms education takes. Reflecting on these traditions helps us to better understand teaching as a particular process – and to recognize that it is fundamentally concerned with didactics rather than pedagogy.

Perhaps the most helpful starting point for this discussion is the strong distinction made in ancient Greek society between the activities of pedagogues (paidagögus) and subject teachers (didáskalos or diadacts). The first pedagogues were slaves – often foreigners and the ‘spoils of war’ (Young 1987). They were trusted and sometimes learned members of rich households who accompanied the sons of their ‘masters’ in the street, oversaw their meals etc., and sat beside them when being schooled. These pedagogues were generally seen as representatives of their wards’ fathers and literally ‘tenders’ of children (pais plus agögos, a ‘child-tender’). Children were often put in their charge at around 7 years and remained with them until late adolescence. As such pedagogues played a major part in their lives – helping them to recognize what was wrong and right, learn how to behave in different situations, and to appreciate how they and those around them might flourish.

Moral supervision by the pedagogue (paidagogos) was also significant in terms of status.

He was more important than the schoolmaster, because the latter only taught a boy his letters, but the paidagogos taught him how to behave, a much more important matter in the eyes of his parents. He was, moreover, even if a slave, a member of the household, in touch with its ways and with the father’s authority and views. The schoolmaster had no such close contact with his pupils. (Castle 1961: 63-4)

The distinction between teachers and pedagogues, instruction and guidance, and education for school or life was a feature of discussions around education for many centuries. It was still around when Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) explored education. In On Pedagogy (Über Pädagogik) first published in 1803, he talked as follows:

Education includes the nurture of the child and, as it grows, its culture. The latter is firstly negative, consisting of discipline; that is, merely the correcting of faults. Secondly, culture is positive, consisting of instruction and guidance (and thus forming part of education). Guidance means directing the pupil in putting into practice what he has been taught. Hence the difference between a private teacher who merely instructs, and a tutor or governor who guides and directs his pupil. The one trains for school only, the other for life. (Kant 1900: 23-4)

It was later – and particularly associated with the work of Herbart (see, for example, Allgemeine pädagogik – General Pedagogics, 1806 and Umriss Pädagogischer Vorlesungen, 1835 – Plan of Lectures on Pedagogy and included in Herbart 1908) – that teaching came to be seen, wrongly, as the central activity of education (see Hamilton 1999).

Didactics – certainly within German traditions – can be approached as Allgemeine Didaktik (general didactics) or as Fachdidaktik (subject didactics). Probably, the most helpful ways of translating didaktik is as the study of the teaching-learning process. It involves researching and theorizing the process and developing practice (see Kansanen 1999). The overwhelming focus within the didaktik tradition is upon the teaching-learning process in schools, colleges and university.

To approach education and learning in other settings it is necessary to turn to the pädagogik tradition. Within this tradition fields like informal education, youth work, community development, art therapy, playwork and child care are approached as forms of pedagogy. Indeed, in countries like Germany and Denmark, a relatively large number of people are employed as pedagogues or social pedagogues. While these pedagogues teach, much of their activity is conversationally, rather than curriculum, -based. Within this what comes to the fore is a focus on flourishing and of the significance of the person of the pedagogue (Smith and Smith 2008). In addition, three elements stand out about the processes of the current generation of specialist pedagogues. First, they are heirs to the ancient Greek process of accompanying and fostering learning. Second, their pedagogy involves a significant amount of helping and caring for. Indeed, for many of those concerned with social pedagogy it is a place where care and education meet – one is not somehow less than the other (Cameron and Moss 2011). Third, they are engaged in what we can call ‘bringing situations to life’ or ‘sparking’ change (animation). In other words, they animate, care and educate (ACE). Woven into those processes are theories and beliefs that we also need to attend to (see Alexander 2000: 541).

We can see from this discussion that when English language commentators talk of pedagogy as the art and science of teaching they are mistaken. As Hamilton (1999) has pointed out teaching in schools is properly approached in the main as didactics – the study of teaching-learning processes. Pedagogy is something very different. It may include didactic elements but for the most part it is concerned with animation, caring and education (see what is education?). It’s focus is upon flourishing and well-being. Within schools there may be specialist educators and practitioners that do this but they are usually not qualified school teachers. Instead they hold other professional qualifications, for example in pedagogy, social work, youth work and community education. To really understand teaching as a process we need to unhook it from school teaching and recognize that it is an activity that is both part of daily life and is an element of other practitioner’s repertoires. Pedagogues teach, for example, but from within a worldview or haltung that is often radically different to school teachers.

Approaching teaching as a process

Some of the teaching we do can be planned in advance because the people involved know that they will be attending a session, event or lesson where learning particular skills, topics or feelings is the focus. Some teaching arises as a response to a question, issue or situation. However, both are dependent on us:

Recognizing and cultivating teachable moments.

Cultivating relationships for learning.

Scaffolding learning – providing people with temporary support so that they deepen and develop their understanding and skills and grow as independent learners.

Differentiating learning – adjusting the way we teach and approach subjects so that we can meet the needs of diverse learners.

Accessing resources for learning.

Adopting a growth mindset.

We are going to look briefly at each of these in turn.

Recognizing and cultivating teachable moments

Teachers – certainly those in most formal settings like schools – have to follow a curriculum. They have to teach specified areas in a particular sequence. As a result, there are always going to be individuals who are not ready for that learning. As teachers in these situations we need to look out for moments when students may be open to learning about different things; where we can, in the language of Quakers, ‘speak to their condition’. Having a sense of their needs and capacities we can respond with the right things at the right time.

Informal educators, animators and pedagogues work differently for a lot of the time. The direction they take is often not set by a syllabus or curriculum. Instead, they listen for, and observe what might be going on for the people they are working with. They have an idea of what might make for well-being and development and can apply it to the experiences and situations that are being revealed. They look out for moments when they can intervene to highlight an issue, give information, and encourage reflection and learning.

In other words, all teaching involves recognizing and cultivating ‘learning moments’ or ‘teaching moments’.

It was Robert J Havinghurst who coined the term ‘teachable moment’. One of his interests as an educationalist was the way in which certain things have to be learned in order for people to develop.

When the timing is right, the ability to learn a particular task will be possible. This is referred to as a ‘teachable moment’. It is important to keep in mind that unless the time is right, learning will not occur. Hence, it is important to repeat important points whenever possible so that when a student’s teachable moment occurs, s/he can benefit from the knowledge. (Havinghurst 1953)

There are times of special sensitivity when learning is possible. We have to look out for them, to help create environments that can create or stimulate such moments, be ready to respond, and draw on the right resources.

Cultivating collaborative relationships for learning

The main thing here is that teaching, like other parts of our work, is about relationship. We have to think about our relationships with those we are supposed to be teaching and about the relationships they have with each other. Creating an environment where people can work with each other, cooperate and learning is essential. One of the things that has been confirmed by recent research in neuroscience is that ‘our brains are wired to connect’, we are wired to be social (Lieberman 2013). It is not surprising then, that on the whole cooperative learning is more effective that either competitive learning (where students compete to meet a goal) or individualistic learning (Hattie 2011: 4733).

As teachers, we need to be appreciated as someone who can draw out learning; cares about what people are feeling, experiencing and need; and breathe life to situations. This entails what Carl Rogers (in Kirschenbaum and Henderson 1990: 304-311) talked about as the core conditions or personal qualities that allow us to facilitate learning in others:

Realness or genuineness. Rogers argued that when we are experienced as real people -entering into relationships with learners ‘without presenting a front or a façade’, we more likely to be effective.

Prizing, acceptance, trust. This involves caring for learners, but in a non-possessive way and recognizing they have worth in their own right. It entails trusting in capacity of others to learn, make judgements and change.

Empathic understanding. ‘When the teacher has the ability to understand the student’s reactions from the inside, has a sensitive awareness of the way the process of education and learning seems to the student, then again the likelihood of significant learning is increased’.

In practical terms this means we talk to people, not at them. We listen. We seek to connect and understand. We trust in their capacity to learn and change. We know that how we say things is often more important than what we say.

Scaffolding

Scaffolding entails providing people with temporary support so that they deepen and develop their understanding and skills – and develop as independent learners.

Like physical scaffolding, the supportive strategies are incrementally removed when they are no longer needed, and the teacher gradually shifts more responsibility over the learning process to the student. (Great Schools Partnership 2015)

To do this well, educators and workers need to be doing what we have explored above – cultivating collaborative relationships for learning, and building on what people know and do and then working just beyond it. The term used for latter of these is taken from the work of Lev Vygotsky – is working in the learner’s zone of proximal development.

A third key aspect of scaffolding is that the support around the particular subject or skill is gradually removed as people develop their expertise and commitment to learning.

Scaffolding can take different forms. It might simply involve ‘showing learners what to do while talking them through the activity and linking new learning to old through questions, resources, activities and language’ (Zwozdiak-Myers and Capel, S. 2013 location 4568). (For a quick overview of some different scaffolding strategies see Alber 2014).

The educational use of the term ‘scaffolding’ is linked to the work of Jerome Bruner –who believed that children (and adults) were active learners. They constructed their own knowledge. Scaffolding was originally used to describe how pedagogues interacted with pre-school children in a nursery (Woods et. al. 1976). Bruner defined scaffolding as ‘the steps taken to reduce the degrees of freedom in carrying out some task so that the child can concentrate on the difficult skill she is in the process of acquiring’ (Bruner 1978: 19).

Differentiation

Differentiation involves adjusting the way we teach and approach subjects so that we can meet the needs of diverse learners. It entails changing content, processes and products so that people can better understand what is being taught and develop appropriate skills and the capacity to act.

The basic idea is that the primary educational objectives—making sure all students master essential knowledge, concepts, and skills—remain the same for every student, but teachers may use different instructional methods to help students meet those expectations. (Great Schools Partnership 2013)

It is often used when working with groups that have within them people with different needs and starting knowledge and skills. (For a quick guide to differentiation see BBC Active).

Accessing resources for learning

One of the key elements we require is the ability to access and make available resources for learning. The two obvious and central resources we have are our own knowledge, feelings and skills; and those of the people we are working with. Harnessing the experience, knowledge and feelings of learners is usually a good starting point. It focuses attention on the issue or subject; shares material; and can encourage joint working. When it is an area that we need to respond to immediately, it can also give us a little space gather our thoughts and access the material we need.

The third key resource is the internet – which we can either make a whole group activity by using search via a whiteboard or screen, or an individual or small group activity via phones and other devices. One of the good things about this is that it also gives us an opportunity not just to reflect on the subject of the search but also on the process. We can examine, for example, the validity of the source or the terms we are using to search for something.

The fourth great resource is activities. Teachers need to build up a repertoire of different activities that can be used to explore issues and areas (see the section below).

Last, and certainly not least, there are the standard classroom resources – textbooks, handouts and study materials.

As teachers we need to have a range of resources at our fingertips. This can be as simple as carrying around a file of activities, leaflets and handouts or having materials, relevant sites and ebooks on our phones and devices.

Adopting a growth mindset

Last, we need to encourage people to adopt what Carol Dweck (2012) calls a growth mindset. Through researching the characteristics of children who succeed in education (and more generally flourish in life), Dweck found that some people have a fixed mindset and some a growth mindset.

Believing that your qualities are carved in stone—the fixed mindset—creates an urgency to prove yourself over and over. If you have only a certain amount of intelligence, a certain personality, and a certain moral character—well, then you’d better prove that you have a healthy dose of them. It simply wouldn’t do to look or feel deficient in these most basic characteristics….

There’s another mindset in which these traits are not simply a hand you’re dealt and have to live with, always trying to convince yourself and others that you have a royal flush when you’re secretly worried it’s a pair of tens. In this mindset, the hand you’re dealt is just the starting point for development. This growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts. Although people may differ in every which way—in their initial talents and aptitudes, interests, or temperaments—everyone can change and grow through application and experience. (Dweck 2012: 6-7)

The fixed mindset is concerned with outcomes and performance; the growth mindset with getting better at the task.

In her research she found, for example, that students with a fixed mindset when making the transition from elementary school to junior high in the United States, declined – their grades immediately dropped and over the next two years continued to decline. Students with a growth mindset showed an increase in their grades (op. cit.: 57). The significance of this for teaching is profound. Praising and valuing achievement tends to strengthen the fixed mindset; praising and valuing effort helps to strengthen a growth mindset.

While it is possible to question elements of Dweck’s research and the either/or way in which prescriptions are presented (see Didau 2015), there is particular merit when teaching of adopting a growth mindset (and encouraging it in others). It looks to change and development rather than proving outselves.

Structuring interventions and making use of different methods

One of the key things that research into the processes of teaching and educating tells us is that learners tend to like structure; they want to know the shape of a session or intervention and what it is about. They also seem to like variety, and changes in the pace of the work (e.g. moving from something quite intense to something free flowing).

It is also worth going back to the dictionary definitions – and the origins of the word ‘teach’. What we find here are some hints of what Geoff Petty (2009) has talked about as ‘teacher-centred’ methods (as against active methods and student-centred methods).

Teacher-centred

|

Active

|

Student-centred

|

Talking |

Supervised student

|

Reading for

|

Explaining |

Discussion |

Private study

|

Showing |

Group work |

Assignments and

|

Questioning |

Games |

Projects and reports |

Note-making |

Role-play, drama

|

Independent

|

Seminars |

Self-directed

|

If we ask learners about their experiences and judgements, one of things that comes strongly through the research in this area is that students overwhelming prefer group discussion, games and simulations and activities like drama, artwork and experiments. At the bottom of this list come analysis, theories, essays and lectures (see Petty 2009: 139-141). However, there is not necessarily a connection between what people enjoy doing and what produces learning.

Schoolteachers may use all of these methods – but so might sports workers and instructors, youth ministers, community development workers and social pedagogues. Unlike schoolteachers, informal educators like these are not having to follow a curriculum for much of their time, nor teach content to pass exams. As such they are able to think more holistically and to think of themselves as facilitators of learning. This means:

Focusing on the active methods in the central column;

Caring about people’s needs, experiences and feeling;

Looking for teachable moments when then can make inputs often along the lines of the first column (teacher-centred methods); and

Encouraging people to learn for themselves i.e. take on projects, to read and study, and to learn independently and be self-directed (student-centred methods).

In an appendix to this piece we look at some key activities of teaching and provide practical guidance. [See key teaching activities]

What does good teaching look like?

What one person sees as good teaching can easily be seen as bad by another. Here we are going to look at what the Ofsted (2015) framework for inspection says. However, before we go there it is worth going back to what Paul Hirst argued back in 1975 and how we are defining teaching here. Our definition was:

Teaching is the process of attending to people’s needs, experiences and feelings, and making specific interventions to help them learn particular things.

We are looking at teaching as a specific process – part of what we do as educators, animators and pedagogues. Ofsted is looking at something rather different. They are grouping together teaching, learning and assessment – and adding in some other things around the sort of outcomes they want to see. That said, it is well worth looking at this list as the thinking behind it does impact on a lot of the work we do.

Inspectors will make a judgement on the effectiveness of teaching, learning and assessment by evaluating the extent to which:

teachers, practitioners and other staff have consistently high expectations of what each child or learner can achieve, including the most able and the most disadvantaged

teachers, practitioners and other staff have a secure understanding of the age group they are working with and have relevant subject knowledge that is detailed and communicated well to children and learners

assessment information is gathered from looking at what children and learners already know, understand and can do and is informed by their parents/previous providers as appropriate

assessment information is used to plan appropriate teaching and learning strategies, including to identify children and learners who are falling behind in their learning or who need additional support, enabling children and learners to make good progress and achieve well

except in the case of the very young, children and learners understand how to improve as a result of useful feedback from staff and, where relevant, parents, carers and employers understand how learners should improve and how they can contribute to this