You might choose the word “purposed” or “purposeful” to describe such a person. If a stronger word is required, then perhaps “adamant” might work.

You might choose the word “purposed” or “purposeful” to describe such a person. If a stronger word is required, then perhaps “adamant” might work.

What is a word for knowing things?

| astute | experienced |

|---|---|

| cognizant | conversant |

| observant | perspicacious |

| sagacious | sensible |

| sentient | brainy |

What can I say instead of I want?

- covet,

- crave,

- desire,

- die (for),

- hanker (for or after),

- wish (for),

- yearn (for)

What is another word for wanting something badly?

| burn | yearn |

|---|---|

| ache | long |

| desire | itch |

| crave | hanker |

| hunger | want |

What do you call someone who knows alot about something?

An expert is a person who is very skilled at doing something or who knows a lot about a particular subject. You may also read,

What does it mean if someone is knowing?

Something that’s knowing is sneakily wise or perceptive. … You can use this adjective to simply mean “having knowledge” or “intentional” too, as when someone makes a knowing purchase of stolen goods. The noun version of knowing is also simple, meaning “the state of having knowledge or being aware.” Check the answer of

What is a perspicacious person?

adjective. having keen mental perception and understanding; discerning: to exhibit perspicacious judgment.

How do you say I want to formally?

If it’s politeness you’re trying to achieve, you could say I would like to know. This transforms what might have been interpreted as a demand into a request. An alternative word would be enquire, such as in I would like to enquire. Read:

What is it called when you want something?

keen. adjective. wanting to do something, or wanting other people to do something.

How do you say I want to be politely?

If you want something, don’t just say “I want.” So don’t say “I want a tuna sandwich” or “I want a cup of coffee” – because this is really, really rude. Instead, you should say “I’d like”. “I’d like” is short for “I would like”. So “I’d like a tuna sandwich” or “I’d like a cup of coffee”.

What’s a powerful word?

A power word (also sometimes confused as a trigger word) is a word that evokes an emotion and a response. It instills in people the desire or need to respond to whatever you’re presenting them with.

What is Feening?

Also feen [feen] . Slang. to desire greatly: just another junkie fiending after his next hit;As soon as I finish a cigarette I’m fiending to light another.

What is the word when you want to be like someone?

Wanting what someone else has and resenting them for having it is envy. … Envy can be used as a noun or as a verb: Envy (noun) is the feeling you have when you envy (verb) what someone else has.

How do you describe someone who knows everything?

A person who knows everything : Omniscient.

alert,brainy,bright,brilliant,clever,exceptional,fast,hyperintelligent,

How do you say someone is very smart?

Introspection is the observation or examination of one’s own mental and emotional state, mental processes, etc. In psychology the process of introspection relies exclusively on observation of one’s mental state, while in a spiritual context it may refer to the examination of one’s soul.

What is it called when you get to know someone?

An acquaintance is someone you know a little about, but they’re not your best friend or anything. An acquaintance is less intimate than a friend, like a person in your class whose name you know, but that’s it. When you “make the acquaintance of” someone, you meet them for the first time.

How long should you know someone before you start dating?

two months

How many dates until you are in a relationship?

Follow the 10 date rule. If you are wondering how many dates you need to go on with someone to classify the relationship as such, it’s about ten dates. This isn’t just arbitrary number though. There’s some science behind it.

How does first kiss feel like?

Your First Kiss Could Feel Gentle Although the experience may not be that long, the tender feeling of the person’s lips will stay with you for a very long time. It may not be a make-out session, but it will be a romantic moment shared between you and your partner and you are likely to enjoy the experience.

What is next step after kiss?

What comes after kissing in a relationship is step 8, moving onto step 8 is quite easy from step 7 and usually happens during a kiss. That next stage we should expect is ‘hand to head. ‘ If you don’t place your hand on your partners head usually, now is the time to try it.

Can you feel love through a kiss?

Answer: Love is easy to feel. You can tell by a kiss! You can also look into the eyes of the one you love and if you look close enough you will see. His pupils dilate and become bigger if he likes you and a kiss from someone you love feels passionate and comfortable at the same time.

English

Русский

Český

Deutsch

Español

عربى

Български

বাংলা

Dansk

Ελληνικά

Suomi

Français

עִברִית

हिंदी

Hrvatski

Magyar

Bahasa indonesia

Italiano

日本語

한국어

മലയാളം

मराठी

Bahasa malay

Nederlands

Norsk

Polski

Português

Română

Slovenský

Slovenščina

Српски

Svenska

தமிழ்

తెలుగు

ไทย

Tagalog

Turkce

Українська

اردو

Tiếng việt

中文

Examples of using

Knowing what you want

in a sentence and their translations

This confidence comes from knowing what you want to say and being comfortable with your communication skills.

Уверенность в себе возникает, когда Вы знаете что хотите сказать, и когда

вы

уверены в своих коммуникативных способностях.

When it comes to looking for a certain product,

Когда это прибывает в искать некоторый продукт,

Results: 30,

Time: 0.0684

Word by word translation

Phrases in alphabetical order

Search the English-Russian dictionary by letter

English

—

Russian

Russian

—

English

There’s nothing wrong with knowing what you don’t want. Actually, that knowledge is essential, especially when it comes to making decisions. If you didn’t know what you don’t want, you might accept a job that you don’t like, eat a meal that leaves you nauseous, or even marry the wrong person.

On the other hand, clarity about what you desire keeps you moving toward it. And it stops you from making decisions you might later regret.

Thinking about what you want when you don’t have it yet can leave you feeling depressed or angry, though. I understand. It’s upsetting to want something you don’t have—unless you realize that what’s upsetting you is your focus on what you don’t want…not your attention to what you do want. The thought that makes you feel so lousy is “I don’t want to not have the thing I desire!”

You’ve got a lot of clarity about what you don’t want. Now you need a stronger sense of knowing about what you do want—and some focus and energy placed on that desire.

Put Your Energy Into What You Want

The other day, I got really upset about something. I needed to leave for an appointment, so I got in the car. As I drove, I gripped the wheel and cried while shouting aloud, “I don’t want it. I don’t want it. I hate that. I don’t like it. I want it out of my life. I don’t want it.”

In other words, I put an enormous amount of emotional and mental energy towards what I didn’t want.

I know better than that.

I don’t want to direct all that energy toward what I don’t desire—ever. Why? The more energy and focus you put on anything, the more likely you are to attract it into your life.

At that moment, I asked myself an enormously important question: “What do I want?”

I continued to grip the steering wheel and, with the same intensity of emotion, I began to recite out loud all the things I wanted. I placed all my focus and passion on what I wanted…my desires.

To do that, though, I had to know what I wanted.

Clarity Aids Creation

If you don’t know what you want, it’s difficult—often impossible—to create it in your life.

Keep in mind that what you want is ever-changing. Sometimes you have the same desire for years and years—like the desire for a red Corvette or to become a parent or to be happy. Other times it’s as if our desires change hourly or daily—you want a mocha…no a chai tea…to get married…to stay single…to get promoted…or maybe to find a new job.

Indeed, what we want changes all the time.

Today, get clear about what you want at this moment. Then, you can figure out what you want in the future.

How to Know What You Want

Grab a journal and make a list of everything you want…everything! Consider all the areas of your life. Keep that list in a safe place, so you can refer back to it regularly.

Next, create a practice of revisiting what you want on a regular basis. Tonight before you go to bed, think about what you want tomorrow. You can make a list in your journal again, but do this every evening.

When you wake up in the morning, review the list and ask yourself if anything has changed since the night before. Maybe you need to add or subtract an item. Review the list; make sure it’s really what you want for the day.

That becomes your weekday ritual. You can continue on Saturday or Sunday, but on Sunday make another list of what you want for the coming week. Review that list daily for the next seven days.

Also, make a list of what you want for the month and for the year. Review this list monthly.

Review Brings Clarity

Sometimes your lists will need to be revamped. You might do it for the whole year and then come back six months later and read it and think, “You know what? My desires have changed.” Okay, fine.

Change it up. A consistent review process will increase your level of clarity around what you want.

Now, you can expand this list by adding an explanation of why you want each item. Determine “why” and get emotionally connected to the reason.

Plus, you can also give each desire a deadline. For example, write I want to create a new home to live in by such and such a date. This adds some more clarity to it.

Every day, strive for increased clarity around what you want. Get really clear about what you want and create a regular practice of evaluating your desires so you gain more clarity. Doing so will make it much easier to create what you want. Without clarity on what you want. You’re going to have a hard time bringing that into your life.

So this week, get some clarity on what it is you want. Get really clear on what it is you want and stick with this practice for the next 12 months and see how it changes your life.

Are you clear about what you want? I’d love it if you left a comment below and told me.

Never miss one of my videos! Click here to subscribe to my YouTube channel.

Photo courtesy of sydney Rae on Unsplash

Download Article

Download Article

The world offers so many opportunities and choices to make that it’s not easy to know what you want. Sometimes, you may confuse what you want with what others want of you. To figure out what you actually want, you will need to do some soul searching and decision making.

-

1

Separate the «shoulds» from the «wants.» Most people have an idea of things they think others expect of them versus the things they actually want. You may feel you should be more organized, you should go back to college, or you should settle down and get married. But all those shoulds won’t get you anywhere if you have no drive to do them. If you do manage to do them, the energy may wane and then you’re back to the starting point five or 10 years down the line. Get rid of your shoulds now so you can focus instead on what you want.[1]

- Most people have trouble seeing which urges are shoulds and which are wants. Take a moment to figure out which is which. What do you actually want? What do you feel like the rest of the world wants you to do? Are you feeling pressure from your parents, your community, society, or peers to do something they feel you should do, but you don’t feel passionate about?

-

2

Make a list of what you’d do if you lived without fear. All people have intangible, abstract fears. Many people are afraid people aren’t going to like or respect them, that they’re going to be broke, that they won’t find a job, have friends, or that they’ll end up alone. To get at what you want, erase all of those for just a second. Fear can control you and keep you from what you want.[2]

- Make a list of all the things you want despite your fears. What would you do if you weren’t afraid of what people thought, afraid of money, or afraid of getting hurt?

Advertisement

-

3

Figure out what dissatisfies you. You probably already know what dissatisfies you. Almost everyone is better at complaining than they are fixing it. By identifying the places in your life where you feel dissatisfied, you can begin to strategize how to change or eliminate those things. Make a list of what makes you unhappy. Why are you dissatisfied? What is it that you’re craving? What would make things better? Write down the answers to these questions.

- For example, think about your job. If you hate your job, it may be possible that you don’t hate the job, but only hate aspects of it. Those aspects need isolating. What things would you change if you could? How might that change your outlook?

- Simply identifying dissatisfying elements of your life won’t make them better. Once you’ve made this list, you need to start thinking about if these are things over which you have some control, and what you can do to change them or remove them from your life. If you hate your job, maybe you need to start figuring out how to find a new position. Or, if it’s simply certain aspects of your job you don’t like, brainstorm ways to improve those things and talk to your boss about implementing some new ideas.

Advertisement

-

1

Make a list of what is important to you. When you don’t know what you want, it can be helpful to get a clear idea of what your values are. Start by making a list of what is important to you. You can include abstract ideas, like love, or concrete things, like food.[3]

- To help you identify your values, ask yourself these questions:

- Which moments in your life thus far have been the most satisfying or fulfilling? What was it about that moment that made you feel satisfied?

- If your house were on fire and you could only grab 3 objects (all pets and family members are already safe), what would they be? Why? What do these things represent to you?

- Think of two people you respect and admire. What characteristics do you admire the most about them? Why?

- What issues get you the most excited when you talk about them? Could you talk for hours about foreign policy, or fashion, or animal rights?

- Look at your answers to these questions and ask yourself if any themes, principles, or beliefs emerge from your answers.

- Once you have identified your values, you should find that making decisions that are in line with these beliefs will help you feel satisfied and happy.[4]

- Values can seem too vague or philosophical to be helpful, but they can give you clues into which decisions and outcomes would be most satisfying.

- To help you identify your values, ask yourself these questions:

-

2

Choose values that cause an emotional response. Values can be described as the combination of goals, beliefs, and positive or negative emotional attitudes. Values play an important part in emotional health because they can produce strong emotional reactions based on if our behaviors align with our values or not. When making your list, don’t just put what you think you should put. Think about things that cause you to feel emotions.[5]

- For example, if you value family time most but make the decision to continuously work 80 hour weeks, you may feel guilt or shame because you have violated a value that is important to you.

- If you value family time, make it a point to always be home by 5 PM, and never work during family time, you might feel proud and fulfilled because your behaviors reflect your values.

-

3

Question yourself. Knowing what you value can help you make decisions about what you want and don’t want. If you’ve never thought about what you value, you may have a difficult time figuring it out. Ask yourself these questions to help you start thinking about what you value:[6]

- At the end of your life, what will you want people to remember about you? That you contributed to science? That you loved your family? That you were honest?

- If you had to choose between work and family, which would be most important to you?

- What topics are you passionate about? Environmentalism? Women’s rights? Finance? Use your passions to help you narrow down what is most important to you.

- If you could only save a few items from a house fire, what would they be? What about those items gives you clues about some of your core values?

-

4

Use your values to make changes. Write down the answers to the questions so you can see them. These answers give you an outline of what you want in life. You can even add to this information as you continue to think about what is important to you. Once you have an idea of what you value most in life, you can begin to construct a clearer picture of what you want. Then, you can start making choices that align with your values.[7]

- For example, if you highly value green energy and recycling, but the company you work for deals mainly in oil, you may feel dissatisfied with your job or even frustrated and angry because much of your work is supporting something that you don’t agree with. You now can recognize this and work to find a job that also values green energy so they can align with your values.

Advertisement

-

1

Focus on the present. Not knowing what you want or not being able to decide often leads to feelings of worry or uncomfortableness. A lot of this worry comes from being afraid of making a wrong decision.[8]

As you begin to make decisions about your life, keep your focus on the present or the near-present. Trying to go too far into the future can lead to stress.- Research shows that our ability to predict what we’ll want in the future is skewed, so you can only make decisions that are right for you in the present with the information you have now. Don’t focus so much on getting it right for your future-self.

-

2

Start by making small decisions. Making decisions can be difficult and scary. You may need to decide what you want from life, or you may need to decide how to get what you want after you know. If you don’t know what you want, making decisions can be difficult. Learning how to make decisions can help you become better at deciding what is right for you. Start with small decisions first, so that you become more comfortable and confident in your ability to make decisions for yourself.[9]

- Not making any decisions at all is also a deciding choice. Sometimes, not making a decision at all often causes more regret than making any decision.

-

3

State the decision that needs to be made. Being able to make informed decisions is helpful because poor decisions or no decision at all can sometimes bring about feelings of pain or regret.[10]

You can start building these skills by stating specifically the decision that you want to make.- You can write down the decision or state it mentally. You need to make it known to yourself what decision has to be made so you can start working towards what you want.

- For example, if you are trying to decide which college major to choose, you would write down, “Decide between engineering and nursing.” If you are trying to decide how to deal with a friend, write, “Decide how to deal with my friend who makes me feel bad sometimes.”

-

4

Gather more information. In this stage, you should gather as much information as you can about your options. Making an informed decision is extremely important because this helps you feel like you have made the right decision. Make sure to include information that is important to your values. You can make a pro/con chart, list details about each option, and make notes about how each option will impact your life, future, and other’s lives.[11]

- For example, you may look up salaries, job opportunities, and amount of time in school when choosing a career. You may consider that nurses deal with and help people daily while engineers deal with numbers and building plans.

- List out all of the information which is important to you.

-

5

Look for alternatives. In this phase of the decision-making process, you should ask yourself if there are options you haven’t thought of or considered yet. This may take a few days to complete. You can do research, talk to people, or think the topic over for a few days. Ask yourself if these are the only choices you can make in the decision. Have you been fair to yourself? Is there another decision you can make that you haven’t written down? Make sure you have all your options listed before making the decision.[12]

- For example, maybe you’ve limited yourself too much in just deciding between engineering and nursing. Possibly, you could also consider a general business major, an art degree, a career as a contractor, or even medical school.

-

6

Evaluate your options. At this stage, look at all the information and possibilities you’ve gathered. Now imagine each possibility carried out through the end and what that would entail. Imagine the outcome of each decision and evaluate your emotional response. Do you feel satisfied with this picture? Does the outcome support your values? The answers to these questions can help you make your decision.[13]

- For example, you can imagine yourself in engineering classes working with computers and numbers, then to your first job at an engineering firm. Imagine yourself doing this type of work every day and evaluate your emotional response. Are you satisfied with this picture? Does your work support your values? Then do the same process with nursing.

Advertisement

-

1

Implement the choice. Review all of your information, and make the best possible choice that is right for you, has fulfilled your values, and seems to align with your professional goals. Then implement the choice. This is the action part of knowing what you want. This is where you start going after what you want.[14]

- For example, you can go to your academic advisor or the dean and formally change your major. Then you can sign up for the appropriate classes.

-

2

Be willing to make mistakes. Sometimes knowing what you want will not be clear until you’ve tried something out. Once you’ve tried something, you can find out if it isn’t for you or if it’s a perfect match. So if you don’t know if it’s what you want, go and try it. Making mistakes is part of learning what we want and discovering what we want.

- Studies show that not knowing an outcome causes more anxiety or discomfort more than knowing that the outcome will be unfavorable.[15]

- For example, if you’re still undecided about nursing or engineering, take active steps to decide which you will like. Look for internships at an engineering office to get a feel for what the work environment might be like. Ask an engineer to show you what he or she does all day. Ask questions to understand more about what the job entails and what to expect. You can shadow a nurse and follow him or her around during the shift to see what a nurse actually does.

- Another possibility would be to take a class specific to engineering and at the same time volunteer at a hospital. Maybe at the end of the semester you’ll find that you actually can’t stand working with computers all day and that you have a knack for calming patients at your volunteering job. Even if you don’t go into engineering, the class wasn’t a waste of time — it helped you make a more informed decision, and you probably still learned a lot from the class.

- Studies show that not knowing an outcome causes more anxiety or discomfort more than knowing that the outcome will be unfavorable.[15]

-

3

Reevaluate your decision from time to time. Just because you want something at one point in your life doesn’t mean you may want something different later. Periodically, go back to your choices and decide if they are still what you want.[16]

- Reflect on the decision to see if it still fits with your goals and values. If it does, you can stay on your current course, but if not, it may be time to reevaluate and go through the decision making process again — and that’s okay.

Advertisement

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To know what you want, you should first figure out what you don’t want by separating the things you think you «should» do, from the things you actually want to do. In order to pin down your real desires, try writing out a list of everything you would do if you lived without fear. From here, you should be able to figure out what dissatisfies you and what is important to you. If you need more help, ask yourself what moments in your life so far have been the most satisfying or fulfilling, and determine what you admire the most about the people that you respect. Once you’ve pinned what’s important to you, begin making changes in your life to better align your actions with your values. For more advice from our co-author, like how to successfully go after what you want, scroll down!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 86,744 times.

Did this article help you?

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Firm, fixed, abiding, clear, positive, sure…

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Another word for knowing exactly what you want?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

Listen to this Guide.

Brought to you by Curio, a Psyche partner

Need to know

Claire, a smart, ambitious student at Tulane University in Louisiana, was on track to have her pick of law schools, but she decided she’d like to get some real-world experience – and have some fun – in New Orleans first. She landed a job as a paralegal, spending her days researching expert witnesses to defend Big Pharma cases, and that’s when the crisis came. Claire had always loved cooking and learning about humanity through cuisine. She was like a female Anthony Bourdain trapped inside an overworked paralegal, and it was slowly making her life miserable.

She began to entertain thoughts of leaving the law firm and working in a kitchen or a coffee shop until she could figure out how to make a career out of her lifelong interest in food. But doubts haunted her. What would other people think? Maybe she’s not that driven. Maybe she’s not that smart, after all. Maybe she’s lazy. What other people expected her to want to do – and her ability to meet those expectations – began to determine her self-worth.

Many people face dilemmas like Claire’s. Each of us is occasionally overwhelmed by a multitude of competing desires: pursue job offer A or B? Start a new relationship or stay single? Sign up to run a marathon, or enjoy not getting up early to train? But life is full of marathons, and they don’t necessarily involve running. It’s good to know which desires to pursue and which ones to leave behind – to know which marathons are worth running. In this Guide, I aim to show you how.

Desires are fundamentally different from needs

It’s true that when people strongly desire something, such as a new shirt, they might feel like they ‘need’ it – but they don’t need it in the same way that they need water or food. Their survival isn’t at stake.

Desire (as opposed to need) is an intellectual appetite for things that you perceive to be good, but that you have no physical, instinctual basis for wanting – and that’s true whether those things are actually good or not.

Your intellectual appetites might include knowing the answer to a mathematics problem; the satisfaction of receiving a text from someone you have a crush on; or getting a coveted job offer. These things won’t necessarily cause physical pleasure. They might spill over into physical enjoyment, but they are not dependent on it. Rather, the pleasure is primarily intellectual.

The 13th-century philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas wrote that these intellectual appetites are part of what has traditionally been called the ‘will’. When a person wills something, they strive toward it. If they come to possess the object of their desire, their will finds rest in it – and they are able to experience joy, so long as they are able to rest in the object of their desire.

But, for most people, such joy is fleeting. There is always something else to strive for – and this keeps most of us in a constant, sometimes painful, state of never-satisfied striving. And that striving for something that we do not yet possess is called desire. Desire doesn’t bring us joy because it is, by definition, always for something we feel we lack. Understanding the mechanism by which desires take shape, though, can help us avoid living our lives in an endless merry-go-round of desire.

Desire is a social process – it is mimetic

When it comes to understanding the mystery of desire, one contemporary thinker stands above all others: the French social theorist René Girard, a historian-turned-polymath who came to the United States shortly after the Second World War and taught at numerous US universities, including Johns Hopkins and Stanford. By the time he died in 2015, he had been named to the Académie Française and was considered one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.

Girard realised one peculiar feature of desire: ‘We would like our desires to come from our deepest selves, our personal depths,’ he said, ‘but if it did, it would not be desire. Desire is always for something we feel we lack.’ Girard noted that desire is not, as we often imagine it, something that we ourselves fully control. It is not something that we can generate or manufacture on our own. It is largely the product of a social process.

‘Man is the creature who does not know what to desire,’ wrote Girard, ‘and he turns to others in order to make up his mind.’ He called this mimetic, or imitative, desire. Mimesis comes from the Greek word for ‘imitation’, which is the root of the English word ‘mimic’. Mimetic desires are the desires that we mimic from the people and culture around us. If I perceive some career or lifestyle or vacation as good, it’s because someone else has modelled it in such a way that it appears good to me.

I first encountered Girard during a period of soul-searching. I had bounced around majors in school, then bounced around jobs, and eventually bounced around starting various companies. But I noticed something odd: whether my business ventures were successful or not, I always grew bored quickly.

At the urging of a friend, I went on a silent retreat. The retreat director recommended I read Girard to help me make sense of why various desires would come to my awareness and then fade away, like distant music heard in a dense forest that I could never quite track down and enjoy for myself.

When I Googled Girard, I found a video of him on a 1970s French talk show smoking a cigarette on live TV, explaining his ideas to a panel of interviewers. At first, I dismissed him as an eccentric French academic who had little to teach me. But the ideas in his book Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978) began to haunt me as I saw mimetic desire playing out all around – and within – me.

I learned that Girard had spent the last 14 years of his career as the Andrew B Hammond Professor of French Language, Literature, and Civilization, at Stanford, where he was the philosophical mentor of Peter Thiel, co-founder of the payments company PayPal and the intelligence company Palantir Technologies – a billionaire who was the first major investor in Facebook. Thiel has credited Girard with helping him see the power of Facebook before most others – and also for helping him escape an unfulfilling career in corporate law and finance. Once he was able to break free from the mimetic herd, he could start thinking more for himself and undertaking projects that were not merely the product of other people’s desires.

That’s when I began to realise that understanding mimetic desire was crucial if I wanted to break free from the cycle that I was stuck in. If, like me, you’d like to get a deeper understanding of your own wants and desires, and to take more control over them, read on.

Think it through

Identify the people influencing what you want

The first step is to identify the models of desire who are influencing what you want. These are the people who serve as your models, or mediators, colouring what you consider to be desirable.

At one point, I wanted a Tesla Model S. I almost talked myself into the purchase with all the ‘objective’ reasons that I thought made it desirable: such as that it goes from zero to 60 miles per hour in under two seconds.

But I would have been better off asking the question who, not what, had generated and shaped my desire for the car. The same is true for your own desires, whether in relation to material purchases, educational paths, career choices, even romantic interests. When it came to the Model S, it wasn’t until I thought seriously about it that I realised that I follow someone on Twitter who obsessively shows videos of himself driving in cool places in that particular vehicle, and that I’d never had a desire to own one until I saw these. From there, I started piling on all the evidence that would support the desire that had already formed – mimetically – within me. Desire comes first from social influences, often long before we realise it, or understand why.

To become more aware of the models influencing your desire, ask yourself these questions:

- When I think about the lifestyle that I would most like to have, who do I feel most embodies it? In reality, this person almost certainly does not live the lifestyle you imagine them to have, but it’s still good to identify those you pay attention to the most when you’re thinking about the kind of life you want.

- Aside from my parents, who were the most important influences on me in my childhood? Which ‘world’ did they come from – a familiar one or a less familiar one? Were they close to me (friends, family), or far away from me (professional athletes, rock stars)? As I’ll explain shortly, the proximity of our models of desire determines how they affect us.

- Is there anyone I would not like to see succeed? Are there certain people whose achievements make me uncomfortable or self-conscious? This is the first clue that they might be a ‘negative model of desire’ – ie, someone you are constantly measuring yourself against.

Categorise your models as internal and external

Next, it’s useful to recognise what kind of models are influencing you. Girard identified two main types: those inside your world, and those outside it.

Models inside your world (‘internal’ models of desire) are the people you might really come into contact with: friends, family, co-workers, or really anyone you can actually interact with in some way – it could be the person who cuts your hair, for instance. These are people whose desires are in some sense intertwined with your own – they can affect your desires, and you can in turn affect theirs.

Models outside your world (‘external’ models of desire) are people you have no serious possibility of coming into contact with: celebrities, historical figures and much of our legacy media. (For instance, most of us can’t interact with Steven Spielberg after watching one of his movies, or debate with the writer of a New York Times article that we disagree with.) External models are one-way streams of desire – they can affect your desires, but you can’t affect theirs. For instance, the Count of Monte Cristo – the protagonist of Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 novel of the same name – was a powerful model of desire for me (for better or worse) after I first read the book as a kid. But the count is a fictional character, so he is necessarily an external model of desire for me. That doesn’t mean that he can’t be a highly influential one, though. Models don’t need to be, and often are not, real people.

Social media falls in a strange, grey area. Many people you encounter there are external models of desire in the sense that you’ll probably never meet them and they might not even ‘follow’ you back. At the same time, everyone at least feels accessible to everyone else. You never know when something you Tweet or post is going to get noticed by someone. This is part of what makes social media so seductive: it straddles the worlds of internal and external mediation of desire. (When you’re on social media, ask yourself: Are these people even real? Do they really want the things they model a desire for, or are we all engaged in a game of signalling?)

Online or offline, the closer someone seems to being like you, the more you can relate to them – and the more you are likely to pay attention to what they want. Who are most people more jealous of? Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world? Or the colleague who has a similar education to you, and a similar job and works roughly the same hours, but who makes an extra $5,000 a year? For almost everyone, it’s the second person. The difference between the internal and the external mediation of desire explains why.

Advertisements also model desires to us, obviously, but notice how they usually work: the companies serving the ads typically show you not the thing itself, but other people wanting the thing. Advertisers play right into our mimetic nature.

Be aware that internal models lead to more volatility of desire in your life because the world of internal models is highly reflexive: you can affect one another’s desires, which isn’t possible in the world of external models.

Working out who your internal and external models of desire are (and which ones are in the grey area) will help you gain greater agency over your desires. I recommend drawing the two overlapping circles above on a blank piece of paper and trying to fill out the spheres with as many specific examples from your own life as you can.

Beware of becoming obsessively focused on what your neighbours have or want

Because desire is mimetic, people are naturally drawn to want what others want. ‘Two desires converging on the same object are bound to clash,’ writes Girard. This means that mimetic desire often leads people into unnecessary competition and rivalry with one another in an infernal game of status anxiety. Mimetic desire is why a class of students can enter a university with very different ideas of what they want to do when they graduate (ideas formed from all the diverse influences and places they came from) yet converge on a much smaller set of opportunities – which they mimetically reinforce in one another – by the time they graduate.

Be aware that your desires can become hijacked through this process of mimetic attraction. It’s easy to become obsessively focused on what your neighbours have or want, rather than on your immediate responsibilities and relationship commitments. We humans are social creatures who know others so that we can also know ourselves, and that’s a good thing – but, if we’re not careful, we can become excessively concerned with others.

The solution involves learning a new way of entering into non-rivalrous relationships with other people – a new kind of relationship in which your sense of self-worth is not derived from them (more on this later).

Map out the systems of desire in your life

As well as identifying the specific models influencing your desires, it is also helpful to consider whether you have become embedded in a particular system of desire. For example, consider the chef Sébastien Bras, owner of Le Suquet restaurant in Laguiole, France, who had three Michelin stars – the highest culinary distinction for a French restaurant – for a full 18 years. Until 2018. That year, he took the unprecedented step of asking the Michelin Guide to stop rating his restaurant and never come back.

Bras had come to the realisation that striving to maintain his three Michelin stars year in and year out had kept him from experimenting with new creative dishes that the Michelin inspectors might not like. His Michelin rating had kept him stuck in a ‘system of desire’. The organising principle for all his choices was simple: keeping Michelin happy.

When he reflected back on why he became a chef in the first place, Bras told me that it was to share ingredients from the Aubrac region of France with the rest of the world – not to become a slave to a ratings system.

When Bras understood the way that the Michelin Guide created a system of desire in which he was trapped, he found the courage to extract himself from that system.

Remember Claire, the paralegal who wanted to go into food? She too was trapped inside a system of desire. In the status-dominated world in which she grew up, it wasn’t viewed as sufficiently ambitious or successful to want to take a lower-paying job in food after graduating from college, so for a time she followed the mimetically magnetic tug of the ‘more prestigious’ track. Claire, it turned out, simply had her own Michelin star system. We all do.

To gain more control over your desires, figure out what your particular version of the Michelin Guide looks like. It might not involve stars at all, but the approval of specific people or the expectations of your friends or family; or the awkwardness of sharing with others that you have always wanted to do something that not many people would understand.

By mapping out the system of desire that you’re enmeshed in (and probably have been your whole life), you can begin to take some critical distance from it. This will allow you to stop accepting your currently dominant desires at face value and save you from defaulting into important life choices instead of choosing them with intentionality.

Most of all: know where your desires came from. Your desires have a history. You can’t know what a ‘true’ or ‘authentic’ desire is unless you understand where it came from – and that involves diving deep into your past, understanding how you have evolved as a person, and seeing which desires have been with you for a long time and which ones have come and gone like the wind.

Take ownership of your desires

Is there such a thing as non-mimetic desires? It’s debatable, even among Girard scholars, so it’s best to think of mimesis on a spectrum:

On the very far left side of this spectrum are desires that aren’t mimetic at all, for instance, a mother’s love for her newborn child. On the less mimetic side would also be desires that are not entirely un-mimetic, but desires that we might call ‘thick’ – they are deeply rooted in a person’s upbringing, or impressed deeply upon their imagination. For someone with a religious sense, these desires could be thought of as given by God as part of a ‘calling’. They are less mimetic in the sense that they have deeper roots, and they aren’t easily variable based on new encounters, seasons or experiences.

On the far right side, there are desires that are nearly entirely mimetic – for instance, the desire to own a stock merely because everyone else wants to own it. (It stimulates a fear of missing out, which is really just a form of mimetic desire.)

Less extreme mimetic desires might include the desire to go to a specific university because all your friends want to go there. Yet the desire could also have something to do with the school’s academic reputation. Desires can have many different influences, some mimetic and some non-mimetic. The key is to understand the forces at work, and to separate the wheat from the chaff.

So are there ‘authentic’ desires? One of the roots of the word authentic is ‘author’. Are any of us authors of our own desires? Yes, we can be. You might not be the sole author of your desires, but you can certainly take ownership and put your mark of authorship on them through your creative freedom.

Consider someone who wants to write a book about a particular subject. Where did the desire to write a book come from in the first place? Hardly anyone wrote books 1,000 years ago. The desire to write a book today likely has a social dimension to it – perhaps a mentor, friend or rival wrote a book. Wanting to write a book, like starting a company or embarking on a career change, is often the product of social interactions.

But whether you have a desire to become an author or to do something else, the crucial point is that the ubiquitous influences that will have shaped that desire don’t preclude you from putting your own stamp of creation on it. Ten people can desire a similar career goal or lifestyle, yet arrive at it in 10 completely unique ways, having discovered nuance in their desires and the way they pursue and live them out.

It’s also possible for a desire to start as highly mimetic but to become less mimetic as you put your own fingerprint on it. Ferruccio Lamborghini got the idea to expand beyond manufacturing tractors due to a personal rivalry with Enzo Ferrari, whose cars he drove. When he kept having a problem with the clutch on one of his Ferraris, he visited Enzo and was mistreated; that day, the desire to make a better sportscar was born in him where previously it didn’t exist.

So does that mean that his desire was merely derivative? Of course not. Once he set out to make a Lamborghini, he made the desire his own, making beautiful vehicles to his own design and drawing on his company’s engineering prowess.

Lamborghini’s story is a great example of how desires do not stay in one place on the spectrum. They’re mobile. They can move to the right (become more mimetic), and they can move to the left (become less mimetic).

Think about which desires you really want to own and cultivate. It doesn’t matter whether they were originally mimetic or not – the intentionality that you bring to them can allow you to become the author of a new creation.

Live an anti-mimetic life

To be anti-mimetic is to be free from the unintentional following of desires without knowing where they came from; it’s freedom from the herd mentality; freedom from the ‘default’ mode that causes us to pursue things without examining why.

It’s possible to develop anti-mimetic machinery in your guts – things that have traditionally been called virtues, or habits of being, such as prudence, fortitude, courage and honesty – that keep you grounded in something deeper even while the mimetic waters swirl around you. In other words, there are certain perennial human values and desires that are worth pursuing no matter what because they have been proven to never disappoint.

Someone with strong underlying values – whether they be religious or philosophical or have another basis – is usually less susceptible to the winds of unhealthy or temporary mimetic desires that lack substance.

There is, as you may have guessed, a religious dimension to all of this. In his Confessions (397-400), Saint Augustine wrote a missive to God about his dawning realisation that his earlier life had been dominated by illusory desires: ‘Our heart is restless until it rests in you.’

In the Christian sense, all desire is a desire for being – which is a desire for God, who is the fullest expression of being. All other desires are merely reflections of, or signposts to, that single greatest desire.

But for a non-religious person, there is still wisdom to be gained from Augustine’s words. Ask yourself: In what person or thing are my desires able to rest without the incessant feeling of restlessness? Why might that be? What is something that seems to bring me longer-lasting joy, without the need for ‘more’?

Restlessness of desire is not necessarily a bad thing – it’s what pushes people to seek more – but a persistent feeling of restlessness could be a sign that the desires you are chasing lack the power to satisfy.

That frustrated paralegal Claire is now my wife. She quit her job at the law firm and embarked on her own anti-mimetic path. She enrolled in a Masters programme in Food Studies at New York University and eventually became an executive at a fast-growing food startup. We met at an Irish pub in Rome as she was travelling doing food research and I was getting my graduate degree. In hindsight, it was an anti-mimetic match: neither one of us would’ve sought out the other or even had the opportunity to meet the other if we had lived by prevailing social norms. The mimesis in our respective worlds would’ve prevented us from ever meeting or falling in love. Fortunately, we were able to bust out of those worlds that night.

Perhaps the most anti-mimetic attitude of all is an openness to wonder and a desire to let reality surprise you. It rarely disappoints.

Key points – How to know what you really want

- Desires are fundamentally different from needs. Unlike physiological needs, such as hunger and thirst, a desire is an intellectual appetite for things that you perceive to be good.

- Desire is a social process – it’s mimetic. As the social theorist René Girard observed, our desires don’t come from within; rather, we mimic what other people want.

- Identify the people or ‘models’ influencing what you want. To better control your desires, the first step is to identify the people influencing you.

- Categorise these models. Working out who is influencing you from within your world, and who is influencing you from the outside, will help you gain greater agency over your desires.

- Beware of becoming obsessively focused on what your neighbours have or want. Mimetic desire often leads people into unnecessary competition and rivalry with one another.

- Map out the systems of desire in your life. It’s not just individuals who influence us, but entire social systems – by identifying them, you can escape their pull.

- Take ownership of your desires. Just because you are not the sole author of your desires, that doesn’t mean you can’t begin to take ownership of them.

- Live an anti-mimetic life. Free yourself from the herd mentality by grounding your life in something deeper.

Why it matters

Mimetic desire is part of the human condition, so it cuts across all domains of life. Here are some brief examples, and how to deal with them:

Relationships

Many people don’t realise that they are in a mimetic rivalry with their own romantic partner or spouse. The Girardian psychologist Jean-Michel Oughourlian, in his book The Genesis of Desire (2007), has said that he sees this relationship dynamic all the time. He calls it the infernal seesaw model of relationships.

‘Couples that are bound by jealousy of each other are always prisoners of the same mechanism: their mirroring desires continually oscillate between the positions of dominating and being dominated – the pattern of relation that transactional analysis calls “one up” and “one down”,’ he writes. It might seem odd to think that a couple could be jealous of one another, or mimetic rivals to one another, but it happens frequently.

‘If I suggest to my husband to read a book, it’s the surest way to make sure that he never reads it,’ one woman told me. Mimetic rivals view the other as a threat to their own autonomy.

Put a serious check on this aspect of your own relationships – romantic or not – and ask yourself if you’re playing a zero-sum game. Make sure that you’re not on a seesaw.

If you suspect that you are, the first task should be to find a way to do something extraordinarily generous for the other person without any expectation of receiving anything in return. It’s difficult because it involves renunciation (renouncing the natural need to get something in return), but it breaks the cycle.

Social media

Social media is a mimetic machine. What we typically call ‘social media’ is really social mediation – the mediation of desires. All day, every day, desires are being modelled to us through people we barely know. Mimetic desire is the hidden engine of these platforms.

Getting off social media completely might be admirable, but it’s not realistic for most people. One thing you can do, though, is be extremely careful – and intentional – about whom you ‘follow’. Make an honest assessment of what kinds of desires the people you follow are cultivating in you. Ask yourself: Is this person I am following actually leading me to develop any positive desires, to aspire to greater things? Or are they causing me more anxiety? At the same time, realise that everything you say or do is a model of desire for someone else.

Career development

Long, stable careers are rare today. Many people make career pivots, but knowing which direction to take is not always easy. It can be helpful to identify and develop some core ‘thick’ desires that underly your motivation, rather than to think in terms of specific job titles, occupations or organisations.

So, what is your core motivation? What is really driving you, and might have been for most of your life? It’s important to put your finger on this because you can apply your core motivational drive across many different types of work. For instance, some people have a core desire to ‘comprehend and express’ – an enduring, motivational drive to do that one thing, no matter the context. This happens to be one of my core desires, and it’s why I enjoy writing books. But the comprehension for me is satisfying only if I also find an outlet for expression. And since I know that about myself, I make sure that any long-term project that I undertake involves the opportunity for me to comprehend and express things constantly. If you can identify those core desires, you will have a powerful tool for cutting through career confusion – because you are also cutting through mimesis.

Possessions

‘It isn’t things themselves that disturb people, but the judgments that they form about them,’ wrote the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Mimetic desire gives significance to things because of the other people who want those things. When the model of desire is gone, so does our interest in the thing.

It’s people we care about most, not things. If you can identify how much significance you place on something merely because of someone else’s relationship to it, you can begin to free yourself from its hold.

My friends Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, authors of the podcast The Minimalists, have devoted themselves to exploring how to live with a minimal amount of material things. ‘Love people, use things,’ they say. Wise advice – every possession, from TVs to NFTs (non-fungible tokens), is merely to be used. From the standpoint of mimetic desire, material things are also talismans for some deeper desire. As Girard wrote, all desire is a desire for being.

So, before you pursue a specific kind of material possession, ask yourself what kind of person you think it’s helping you to become – and, if you don’t like the answer, maybe reconsider the purchase.

Lifestyle

The Instagram hashtag #VanLife looked glamorous to many people in 2020. It was a fad for escaping to the open road in tricked-out motor homes and sharing curated images of the experience on social media. But it’s now becoming clear that the images often covered up the serious hardships involved in travelling with another person for extended periods – everything from temporary traffic anxieties to a permanent lack of stability.

Some people embarked on this journey without weighing up the psychological costs. We know now that many of them regretted it, and some even lost their lives to mental illness – all the while presenting to the world an image of freedom.

Likewise with farm life. Many have fantasised about living on a farm and taking care of animals while ignoring the realities of having to clean up cow manure or feed the pigs every morning.

It’s typical for people to think to themselves: ‘If I only lived in that city [or house/neighbourhood/country] … everything would be better.’ But when it comes to lifestyle, there is no one particular form that is the answer to all our problems, or the key to happiness.

It’s likely that if you can’t be happy right where you’re at, right now, then you probably won’t be happy anywhere. Your happiness will always be something ‘out there’, beyond the horizon, and mimetic desire will continue to exert an unhealthy control over you.

On the other hand, there are some enduring values – such as health, creativity or the opportunity to share meals with other people – that never go out of style, and there are as many ways to pursue them as there are people on this planet. Lifestyle is something that emerges from one’s values and discipline, not something you find at a particular zip code or via the keys to a different house or van.

There is no perfect model out there for the life you want to lead because you’re a unique and unrepeatable person, and the stamp you leave on this world will be your own. Those who come after you might be inspired to model parts of their life or their desires on yours, but they too will need to embark on the same adventure of being a transcendent leader in a mimetic world. Seeing the patterns that exist in the lives and desires of others, and then making something new and beautiful out of them: that is your opportunity and your legacy.

Links & books

The five-minute video ‘How to Know What You Really Want’ (2021) for Big Think, in which I explain the difference between ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ desires and how to tell them apart.

The two-minute video ‘René Girard Explains Mimetic Desire’ (2018) produced by Imitatio, a foundation set up to make Girard’s ideas more widely known and understood.

The article ‘Secrets About People: A Short and Dangerous Introduction to René Girard’ (2019) by Alex Danco, a Shopify employee and Girard aficionado.

The video ‘The Invention of Blame (Scapegoat Mechanism)’ (2017) from the YouTube channel Vsauce2 hosted by Kevin Lieber explains the darker side of mimetic theory: how unrestrained mimesis spreads through contagion until it results in conflict and violence within a community as a means to bring the mimetic crisis under control.

The video ‘Wanting’ (2021), episode 290 in The Minimalists podcast series hosted by Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, with myself as guest, discusses why we want what we want and how we can free ourselves from mimetic desires.

My short introduction ‘Mimetic Desire 101’ (2021) on my Substack newsletter Anti-Mimetic, which is entirely dedicated to exploring questions related to mimetic desire and especially how one might go about living an anti-mimetic life – or one free from the harmful, negative effects of unrecognised mimesis.

The book Mimesis and Science (2011) edited by the clinical psychologist Scott Garrels in California features empirical research on imitation, and features everything from early childhood development studies to mimetic evolution in nature. I highly recommend this volume for anyone who would like to ground mimetic theory in science.

The book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (1999) by René Girard. If you’d like to explore primary source material, this is Girard’s most accessible book and one that unpacks the theological implications of the ideas in this Guide.

My book Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life (2021) serves as a non-academic introduction to Girard’s thought. The first half of the book provides an in-depth overview of his key ideas, and the second half helps readers apply them to their own lives.

Unit 50- Part A

|

|

| When the question (Where has Tom gone?) is part of a longer sentence (Do you know … ? / I don’t know … / Can you tell me … ? etc.), the word order changes. We say: | |

| • What time is it? but • Who are those people? • Where can I find Linda? • How much will it cost? |

Do you know what time it is? I don’t know who those people are. Can you tell me where I can find Linda? Do you have any idea how much it will cost? |

Be careful with do/does/did questions. We say: |

|

| • What time does the film begin? but • What do you mean? |

Do you know what rime the film begins? (not does the film begin) Please explain what you mean. I wonder why she left early. |

Use if or whether where there is no other question word (what, why etc.): |

|

| • Did anybody see you? but | Do you know if anybody saw you? or … whether anybody saw you? |

Unit 50- Part B

Exercises

{slide=1 Make a new sentence from the question in brackets.}Make a new sentence from the question in brackets.

{tooltip}Key.{end-link}2 Could you tell me where the post office is?

3 I wonder what the time is.

4 I want to know what this word means.

5 Do you know what time they left?

6 I don’t know if/whether Sue is going out tonight.

7 Do you have any idea where Caroline lives?

8 I can’t remember where I parked the car.

9 Can you tell me if/whether there is a bank near here?

10 Tell me what you want.

11 I don’t know why Kate didn’t come to the party.

12 Do you know how much it costs to park here?

13 I have no idea who that woman is.

14 Do you know if/whether Liz got my letter?

15 Can you tell me how far it is to the airport?{end-tooltip}

1 (Where has Tom gone?)

Do you know where Tom has gone?

2 (Where is the post office?)

Could you tell me where ______________________

3 (What’s the time?)

I wonder ______________________

4 (What does this word mean?)

I want to know ______________________

5 (What time did they leave?)

Do you know ______________________

6 (Is Sue going out tonight?)

I don’t know ______________________

7 (Where does Caroline live?)

Do you have any idea ______________________

8 (Where did I park the car?)

I can’t remember ______________________

9 (Is there a bank near here?)

Can you tell me ______________________

10 (What do you want?)

Tell me ______________________

11 (Why didn’t Kate come to the party?)

I don’t know ______________________

12 (How much does it cost to park here?)

Do you know ______________________

13 (Who is that woman?)

I have no idea ______________________

14 (Did Liz get my letter?)

Do you know ______________________

15 (How far is it to the airport?)

Can you tell me ______________________ {/slide} {slide=2 Complete the conversation.}You are making a phone call. You want to speak to Sue, but she isn’t there. Somebody else answers the phone. You want to know three things:

(1) Where has she gone? (2) When will she be back? and (3) Did she go out alone? Complete the conversation:

{tooltip}Key.{end-link}1 Do you know where she has gone?

2 I don’t suppose you know when she’ll be back / she will be back.

3 Do you happen to know it/whether she went out alone?{end-tooltip}

A: Do you know where _____________________? (1)

B: Sorry, I’ve got no idea.

A: Never mind. I don’t suppose you know _____________________. (2)

B: No, I’m afraid not.

A: One more thing. Do you happen to know _____________________? (3)

B: I’m afraid I didn’t see her go out.

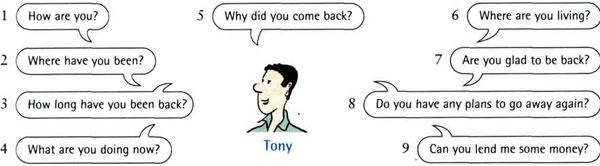

A: OK. Well, thank you anyway. Goodbye. {/slide} {slide=3 Tony asks you a lot of questions.}You have been away for a while and have just come back to your home town. You meet Tony, a friend of yours. He asks you a lot of questions:

{tooltip}Key.{end-link}2 He asked me where I’d been. / … where I had been.

3 He asked me how long I’d been back. / … how long I had been back.

4 He asked me what I was doing now.

5 He asked me why I’d come back. / … why I had come back, or … why I came back.

6 He asked me where I was living.

7 He asked me if/whether I was glad to be back.

8 He asked me if/whether I had any plans to go away again.

9 He asked me if/whether I could lend him some money.{end-tooltip}

Now you tell another friend what Tony asked you. Use reported speech.

1 He asked me how I was.

2 He asked me ______________________

3 He ________________________________

4 ___________________________________

6 ___________________________________

7 ___________________________________

8 ___________________________________

9 ___________________________________ {/slide}

Жилые комплексы с единой концепцией развития окружающей территории, своей инфрастуктурой, однородной социальной средой всегда приквлекают внимание желающих приобрести жилье. Приобретая квартиру в жилом комплексе Гранатный 6, вы приобретаете соответствующее качество жизни, и максимум комфорта.

Exercise 1

Which is right? Tick the correct alternative.

1 a Do you know what time the film starts?

b Do you know what time does the film start?

c Do you know what time starts the film?

2 a Why Amy does get up so early every day?

b Why Amy gets up so early every day?

c Why does Amy get up so early every day?

3 a I want to know what this word means.

b I want to know what does this word mean.

c I want to know what means this word.

4 a I can’t remember where did I park the car.

b I can’t remember where I parked the car.

c I can’t remember where I did park the car.

5 a Why you didn’t phone me yesterday?

b Why didn’t you phone me yesterday?

c Why you not phoned me yesterday?

6 a Do you know where does Helen work?

b Do you know where Helen does work?

c Do you know where Helen works?

7 a How much it costs to park here?

b How much does it cost to park here?

c How much it does cost to park here?

8 a Tell me what you want.

b Tell me what you do want.

c Tell me what do you want.