Deoxyribonucleic acid (;[1] DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids. Alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life.

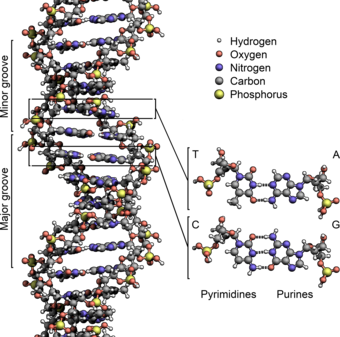

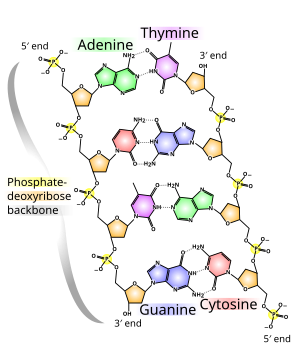

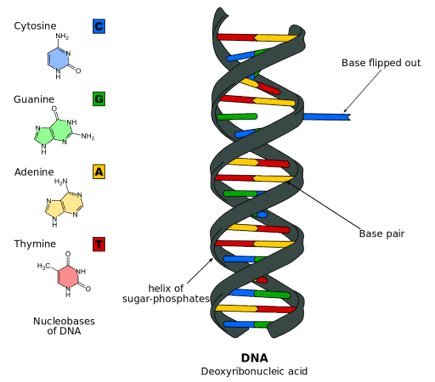

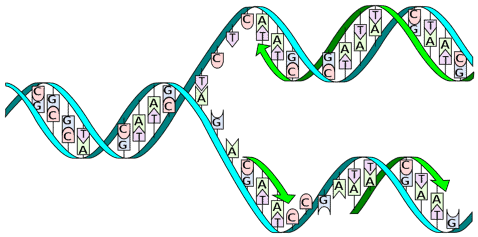

The two DNA strands are known as polynucleotides as they are composed of simpler monomeric units called nucleotides.[2][3] Each nucleotide is composed of one of four nitrogen-containing nucleobases (cytosine [C], guanine [G], adenine [A] or thymine [T]), a sugar called deoxyribose, and a phosphate group. The nucleotides are joined to one another in a chain by covalent bonds (known as the phosphodiester linkage) between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the next, resulting in an alternating sugar-phosphate backbone. The nitrogenous bases of the two separate polynucleotide strands are bound together, according to base pairing rules (A with T and C with G), with hydrogen bonds to make double-stranded DNA. The complementary nitrogenous bases are divided into two groups, pyrimidines and purines. In DNA, the pyrimidines are thymine and cytosine; the purines are adenine and guanine.

Both strands of double-stranded DNA store the same biological information. This information is replicated when the two strands separate. A large part of DNA (more than 98% for humans) is non-coding, meaning that these sections do not serve as patterns for protein sequences. The two strands of DNA run in opposite directions to each other and are thus antiparallel. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of nucleobases (or bases). It is the sequence of these four nucleobases along the backbone that encodes genetic information. RNA strands are created using DNA strands as a template in a process called transcription, where DNA bases are exchanged for their corresponding bases except in the case of thymine (T), for which RNA substitutes uracil (U).[4] Under the genetic code, these RNA strands specify the sequence of amino acids within proteins in a process called translation.

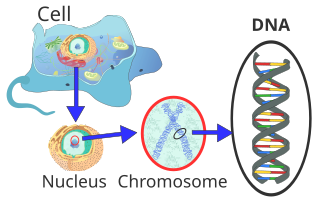

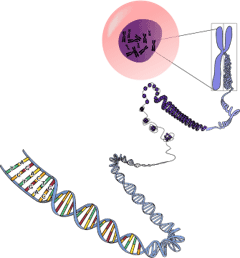

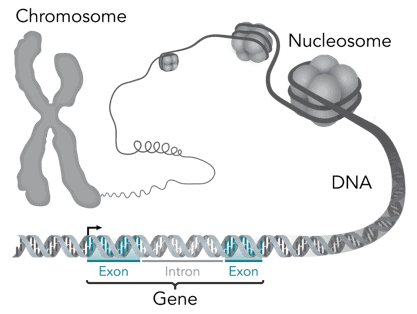

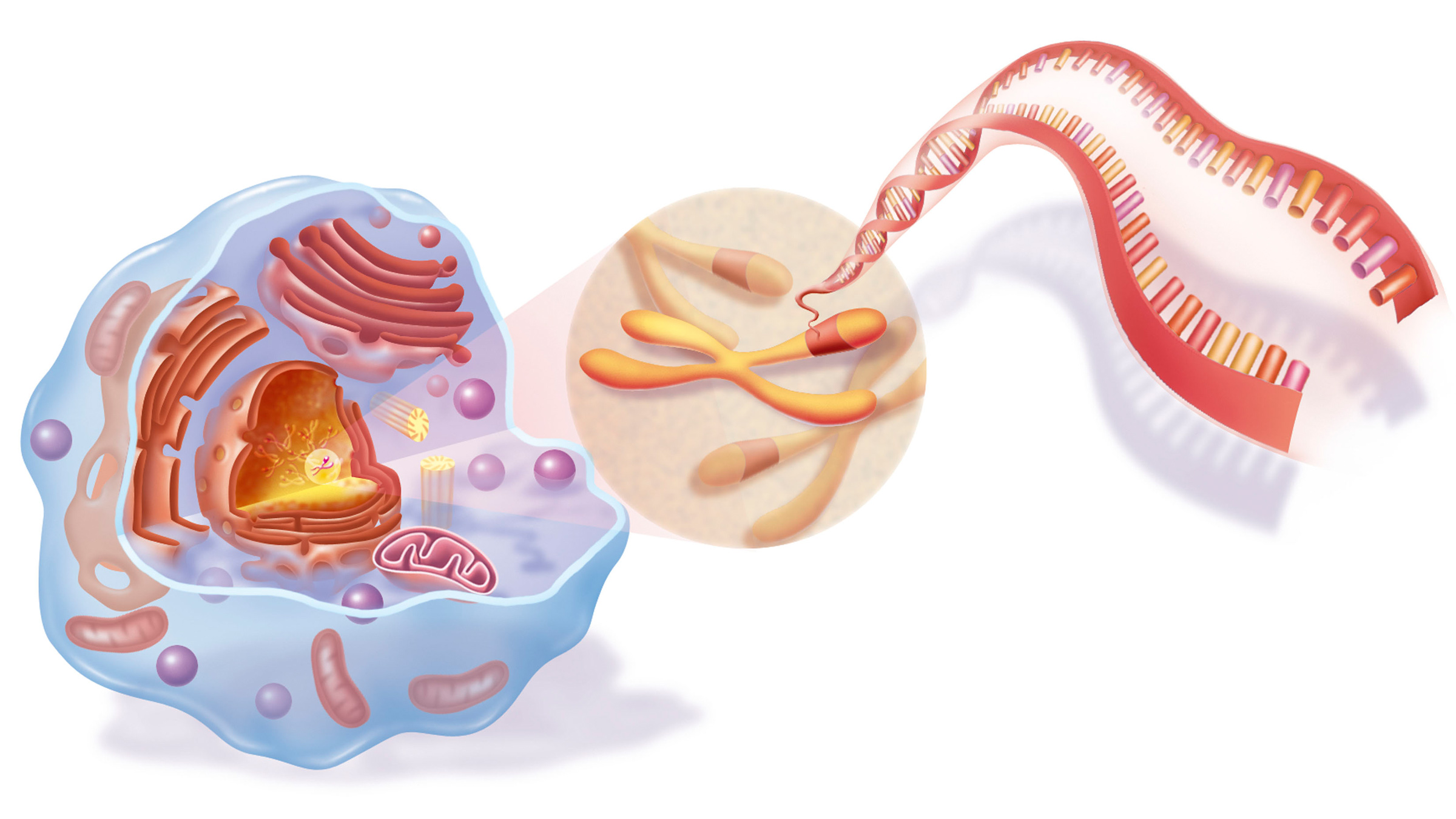

Within eukaryotic cells, DNA is organized into long structures called chromosomes. Before typical cell division, these chromosomes are duplicated in the process of DNA replication, providing a complete set of chromosomes for each daughter cell. Eukaryotic organisms (animals, plants, fungi and protists) store most of their DNA inside the cell nucleus as nuclear DNA, and some in the mitochondria as mitochondrial DNA or in chloroplasts as chloroplast DNA.[5] In contrast, prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) store their DNA only in the cytoplasm, in circular chromosomes. Within eukaryotic chromosomes, chromatin proteins, such as histones, compact and organize DNA. These compacting structures guide the interactions between DNA and other proteins, helping control which parts of the DNA are transcribed.

Properties

Chemical structure of DNA; hydrogen bonds shown as dotted lines. Each end of the double helix has an exposed 5′ phosphate on one strand and an exposed 3′ hydroxyl group (—OH) on the other.

DNA is a long polymer made from repeating units called nucleotides.[6][7] The structure of DNA is dynamic along its length, being capable of coiling into tight loops and other shapes.[8] In all species it is composed of two helical chains, bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. Both chains are coiled around the same axis, and have the same pitch of 34 ångströms (3.4 nm). The pair of chains have a radius of 10 Å (1.0 nm).[9] According to another study, when measured in a different solution, the DNA chain measured 22–26 Å (2.2–2.6 nm) wide, and one nucleotide unit measured 3.3 Å (0.33 nm) long.[10]

DNA does not usually exist as a single strand, but instead as a pair of strands that are held tightly together.[9][11] These two long strands coil around each other, in the shape of a double helix. The nucleotide contains both a segment of the backbone of the molecule (which holds the chain together) and a nucleobase (which interacts with the other DNA strand in the helix). A nucleobase linked to a sugar is called a nucleoside, and a base linked to a sugar and to one or more phosphate groups is called a nucleotide. A biopolymer comprising multiple linked nucleotides (as in DNA) is called a polynucleotide.[12]

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar groups.[13] The sugar in DNA is 2-deoxyribose, which is a pentose (five-carbon) sugar. The sugars are joined by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms of adjacent sugar rings. These are known as the 3′-end (three prime end), and 5′-end (five prime end) carbons, the prime symbol being used to distinguish these carbon atoms from those of the base to which the deoxyribose forms a glycosidic bond.[11]

Therefore, any DNA strand normally has one end at which there is a phosphate group attached to the 5′ carbon of a ribose (the 5′ phosphoryl) and another end at which there is a free hydroxyl group attached to the 3′ carbon of a ribose (the 3′ hydroxyl). The orientation of the 3′ and 5′ carbons along the sugar-phosphate backbone confers directionality (sometimes called polarity) to each DNA strand. In a nucleic acid double helix, the direction of the nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other strand: the strands are antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of DNA strands are said to have a directionality of five prime end (5′ ), and three prime end (3′), with the 5′ end having a terminal phosphate group and the 3′ end a terminal hydroxyl group. One major difference between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with the 2-deoxyribose in DNA being replaced by the related pentose sugar ribose in RNA.[11]

A section of DNA. The bases lie horizontally between the two spiraling strands[14] (animated version).

The DNA double helix is stabilized primarily by two forces: hydrogen bonds between nucleotides and base-stacking interactions among aromatic nucleobases.[15] The four bases found in DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). These four bases are attached to the sugar-phosphate to form the complete nucleotide, as shown for adenosine monophosphate. Adenine pairs with thymine and guanine pairs with cytosine, forming A-T and G-C base pairs.[16][17]

Nucleobase classification

The nucleobases are classified into two types: the purines, A and G, which are fused five- and six-membered heterocyclic compounds, and the pyrimidines, the six-membered rings C and T.[11] A fifth pyrimidine nucleobase, uracil (U), usually takes the place of thymine in RNA and differs from thymine by lacking a methyl group on its ring. In addition to RNA and DNA, many artificial nucleic acid analogues have been created to study the properties of nucleic acids, or for use in biotechnology.[18]

Non-canonical bases

Modified bases occur in DNA. The first of these recognized was 5-methylcytosine, which was found in the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1925.[19] The reason for the presence of these noncanonical bases in bacterial viruses (bacteriophages) is to avoid the restriction enzymes present in bacteria. This enzyme system acts at least in part as a molecular immune system protecting bacteria from infection by viruses.[20] Modifications of the bases cytosine and adenine, the more common and modified DNA bases, play vital roles in the epigenetic control of gene expression in plants and animals.[21]

A number of noncanonical bases are known to occur in DNA.[22] Most of these are modifications of the canonical bases plus uracil.

- Modified Adenine

- N6-carbamoyl-methyladenine

- N6-methyadenine

- Modified Guanine

- 7-Deazaguanine

- 7-Methylguanine

- Modified Cytosine

- N4-Methylcytosine

- 5-Carboxylcytosine

- 5-Formylcytosine

- 5-Glycosylhydroxymethylcytosine

- 5-Hydroxycytosine

- 5-Methylcytosine

- Modified Thymidine

- α-Glutamythymidine

- α-Putrescinylthymine

- Uracil and modifications

- Base J

- Uracil

- 5-Dihydroxypentauracil

- 5-Hydroxymethyldeoxyuracil

- Others

- Deoxyarchaeosine

- 2,6-Diaminopurine (2-Aminoadenine)

Grooves

DNA major and minor grooves. The latter is a binding site for the Hoechst stain dye 33258.

Twin helical strands form the DNA backbone. Another double helix may be found tracing the spaces, or grooves, between the strands. These voids are adjacent to the base pairs and may provide a binding site. As the strands are not symmetrically located with respect to each other, the grooves are unequally sized. The major groove is 22 ångströms (2.2 nm) wide, while the minor groove is 12 Å (1.2 nm) in width.[23] Due to the larger width of the major groove, the edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove than in the minor groove. As a result, proteins such as transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contact with the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.[24] This situation varies in unusual conformations of DNA within the cell (see below), but the major and minor grooves are always named to reflect the differences in width that would be seen if the DNA was twisted back into the ordinary B form.

Base pairing

Top, a GC base pair with three hydrogen bonds. Bottom, an AT base pair with two hydrogen bonds. Non-covalent hydrogen bonds between the pairs are shown as dashed lines.

In a DNA double helix, each type of nucleobase on one strand bonds with just one type of nucleobase on the other strand. This is called complementary base pairing. Purines form hydrogen bonds to pyrimidines, with adenine bonding only to thymine in two hydrogen bonds, and cytosine bonding only to guanine in three hydrogen bonds. This arrangement of two nucleotides binding together across the double helix (from six-carbon ring to six-carbon ring) is called a Watson-Crick base pair. DNA with high GC-content is more stable than DNA with low GC-content. A Hoogsteen base pair (hydrogen bonding the 6-carbon ring to the 5-carbon ring) is a rare variation of base-pairing.[25] As hydrogen bonds are not covalent, they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of DNA in a double helix can thus be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a mechanical force or high temperature.[26] As a result of this base pair complementarity, all the information in the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each strand, which is vital in DNA replication. This reversible and specific interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the functions of DNA in organisms.[7]

ssDNA vs. dsDNA

As noted above, most DNA molecules are actually two polymer strands, bound together in a helical fashion by noncovalent bonds; this double-stranded (dsDNA) structure is maintained largely by the intrastrand base stacking interactions, which are strongest for G,C stacks. The two strands can come apart—a process known as melting—to form two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules. Melting occurs at high temperatures, low salt and high pH (low pH also melts DNA, but since DNA is unstable due to acid depurination, low pH is rarely used).

The stability of the dsDNA form depends not only on the GC-content (% G,C basepairs) but also on sequence (since stacking is sequence specific) and also length (longer molecules are more stable). The stability can be measured in various ways; a common way is the melting temperature (also called Tm value), which is the temperature at which 50% of the double-strand molecules are converted to single-strand molecules; melting temperature is dependent on ionic strength and the concentration of DNA. As a result, it is both the percentage of GC base pairs and the overall length of a DNA double helix that determines the strength of the association between the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high GC-content have more strongly interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content have more weakly interacting strands.[27] In biology, parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in some promoters, tend to have a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.[28]

In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be measured by finding the melting temperature Tm necessary to break half of the hydrogen bonds. When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules. These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but some conformations are more stable than others.[29]

Amount

In humans, the total female diploid nuclear genome per cell extends for 6.37 Gigabase pairs (Gbp), is 208.23 cm long and weighs 6.51 picograms (pg).[30] Male values are 6.27 Gbp, 205.00 cm, 6.41 pg.[30] Each DNA polymer can contain hundreds of millions of nucleotides, such as in chromosome 1. Chromosome 1 is the largest human chromosome with approximately 220 million base pairs, and would be 85 mm long if straightened.[31]

In eukaryotes, in addition to nuclear DNA, there is also mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) which encodes certain proteins used by the mitochondria. The mtDNA is usually relatively small in comparison to the nuclear DNA. For example, the human mitochondrial DNA forms closed circular molecules, each of which contains 16,569[32][33] DNA base pairs,[34] with each such molecule normally containing a full set of the mitochondrial genes. Each human mitochondrion contains, on average, approximately 5 such mtDNA molecules.[34] Each human cell contains approximately 100 mitochondria, giving a total number of mtDNA molecules per human cell of approximately 500.[34] However, the amount of mitochondria per cell also varies by cell type, and an egg cell can contain 100,000 mitochondria, corresponding to up to 1,500,000 copies of the mitochondrial genome (constituting up to 90% of the DNA of the cell).[35]

Sense and antisense

A DNA sequence is called a «sense» sequence if it is the same as that of a messenger RNA copy that is translated into protein.[36] The sequence on the opposite strand is called the «antisense» sequence. Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the same strand of DNA (i.e. both strands can contain both sense and antisense sequences). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense RNA sequences are produced, but the functions of these RNAs are not entirely clear.[37] One proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression through RNA-RNA base pairing.[38]

A few DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmids and viruses, blur the distinction between sense and antisense strands by having overlapping genes.[39] In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein when read along one strand, and a second protein when read in the opposite direction along the other strand. In bacteria, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription,[40] while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.[41]

Supercoiling

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling. With DNA in its «relaxed» state, a strand usually circles the axis of the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound.[42] If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzymes called topoisomerases.[43] These enzymes are also needed to relieve the twisting stresses introduced into DNA strands during processes such as transcription and DNA replication.[44]

Alternative DNA structures

From left to right, the structures of A, B and Z-DNA

DNA exists in many possible conformations that include A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA forms, although only B-DNA and Z-DNA have been directly observed in functional organisms.[13] The conformation that DNA adopts depends on the hydration level, DNA sequence, the amount and direction of supercoiling, chemical modifications of the bases, the type and concentration of metal ions, and the presence of polyamines in solution.[45]

The first published reports of A-DNA X-ray diffraction patterns—and also B-DNA—used analyses based on Patterson functions that provided only a limited amount of structural information for oriented fibers of DNA.[46][47] An alternative analysis was proposed by Wilkins et al. in 1953 for the in vivo B-DNA X-ray diffraction-scattering patterns of highly hydrated DNA fibers in terms of squares of Bessel functions.[48] In the same journal, James Watson and Francis Crick presented their molecular modeling analysis of the DNA X-ray diffraction patterns to suggest that the structure was a double helix.[9]

Although the B-DNA form is most common under the conditions found in cells,[49] it is not a well-defined conformation but a family of related DNA conformations[50] that occur at the high hydration levels present in cells. Their corresponding X-ray diffraction and scattering patterns are characteristic of molecular paracrystals with a significant degree of disorder.[51][52]

Compared to B-DNA, the A-DNA form is a wider right-handed spiral, with a shallow, wide minor groove and a narrower, deeper major groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in partly dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, and in enzyme-DNA complexes.[53][54] Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form.[55] These unusual structures can be recognized by specific Z-DNA binding proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.[56]

Alternative DNA chemistry

For many years, exobiologists have proposed the existence of a shadow biosphere, a postulated microbial biosphere of Earth that uses radically different biochemical and molecular processes than currently known life. One of the proposals was the existence of lifeforms that use arsenic instead of phosphorus in DNA. A report in 2010 of the possibility in the bacterium GFAJ-1 was announced,[57][58] though the research was disputed,[58][59] and evidence suggests the bacterium actively prevents the incorporation of arsenic into the DNA backbone and other biomolecules.[60]

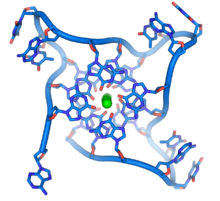

Quadruplex structures

DNA quadruplex formed by telomere repeats. The looped conformation of the DNA backbone is very different from the typical DNA helix. The green spheres in the center represent potassium ions.[61]

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomeres. The main function of these regions is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as the enzymes that normally replicate DNA cannot copy the extreme 3′ ends of chromosomes.[62] These specialized chromosome caps also help protect the DNA ends, and stop the DNA repair systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected.[63] In human cells, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.[64]

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilize chromosome ends by forming structures of stacked sets of four-base units, rather than the usual base pairs found in other DNA molecules. Here, four guanine bases, known as a guanine tetrad, form a flat plate. These flat four-base units then stack on top of each other to form a stable G-quadruplex structure.[65] These structures are stabilized by hydrogen bonding between the edges of the bases and chelation of a metal ion in the centre of each four-base unit.[66] Other structures can also be formed, with the central set of four bases coming from either a single strand folded around the bases, or several different parallel strands, each contributing one base to the central structure.

In addition to these stacked structures, telomeres also form large loop structures called telomere loops, or T-loops. Here, the single-stranded DNA curls around in a long circle stabilized by telomere-binding proteins.[67] At the very end of the T-loop, the single-stranded telomere DNA is held onto a region of double-stranded DNA by the telomere strand disrupting the double-helical DNA and base pairing to one of the two strands. This triple-stranded structure is called a displacement loop or D-loop.[65]

Branched DNA can form networks containing multiple branches.

Branched DNA

In DNA, fraying occurs when non-complementary regions exist at the end of an otherwise complementary double-strand of DNA. However, branched DNA can occur if a third strand of DNA is introduced and contains adjoining regions able to hybridize with the frayed regions of the pre-existing double-strand. Although the simplest example of branched DNA involves only three strands of DNA, complexes involving additional strands and multiple branches are also possible.[68] Branched DNA can be used in nanotechnology to construct geometric shapes, see the section on uses in technology below.

Artificial bases

Several artificial nucleobases have been synthesized, and successfully incorporated in the eight-base DNA analogue named Hachimoji DNA. Dubbed S, B, P, and Z, these artificial bases are capable of bonding with each other in a predictable way (S–B and P–Z), maintain the double helix structure of DNA, and be transcribed to RNA. Their existence could be seen as an indication that there is nothing special about the four natural nucleobases that evolved on Earth.[69][70] On the other hand, DNA is tightly related to RNA which does not only act as a transcript of DNA but also performs as molecular machines many tasks in cells. For this purpose it has to fold into a structure. It has been shown that to allow to create all possible structures at least four bases are required for the corresponding RNA,[71] while a higher number is also possible but this would be against the natural principle of least effort.

Acidity

The phosphate groups of DNA give it similar acidic properties to phosphoric acid and it can be considered as a strong acid. It will be fully ionized at a normal cellular pH, releasing protons which leave behind negative charges on the phosphate groups. These negative charges protect DNA from breakdown by hydrolysis by repelling nucleophiles which could hydrolyze it.[72]

Macroscopic appearance

Impure DNA extracted from an orange

Pure DNA extracted from cells forms white, stringy clumps.[73]

Chemical modifications and altered DNA packaging

Structure of cytosine with and without the 5-methyl group. Deamination converts 5-methylcytosine into thymine.

Base modifications and DNA packaging

The expression of genes is influenced by how the DNA is packaged in chromosomes, in a structure called chromatin. Base modifications can be involved in packaging, with regions that have low or no gene expression usually containing high levels of methylation of cytosine bases. DNA packaging and its influence on gene expression can also occur by covalent modifications of the histone protein core around which DNA is wrapped in the chromatin structure or else by remodeling carried out by chromatin remodeling complexes (see Chromatin remodeling). There is, further, crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modification, so they can coordinately affect chromatin and gene expression.[74]

For one example, cytosine methylation produces 5-methylcytosine, which is important for X-inactivation of chromosomes.[75] The average level of methylation varies between organisms—the worm Caenorhabditis elegans lacks cytosine methylation, while vertebrates have higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine.[76] Despite the importance of 5-methylcytosine, it can deaminate to leave a thymine base, so methylated cytosines are particularly prone to mutations.[77] Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria, the presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the brain,[78] and the glycosylation of uracil to produce the «J-base» in kinetoplastids.[79][80]

Damage

DNA can be damaged by many sorts of mutagens, which change the DNA sequence. Mutagens include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and X-rays. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light can damage DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between pyrimidine bases.[82] On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, and double-strand breaks.[83] A typical human cell contains about 150,000 bases that have suffered oxidative damage.[84] Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions, deletions from the DNA sequence, and chromosomal translocations.[85] These mutations can cause cancer. Because of inherent limits in the DNA repair mechanisms, if humans lived long enough, they would all eventually develop cancer.[86][87] DNA damages that are naturally occurring, due to normal cellular processes that produce reactive oxygen species, the hydrolytic activities of cellular water, etc., also occur frequently. Although most of these damages are repaired, in any cell some DNA damage may remain despite the action of repair processes. These remaining DNA damages accumulate with age in mammalian postmitotic tissues. This accumulation appears to be an important underlying cause of aging.[88][89][90]

Many mutagens fit into the space between two adjacent base pairs, this is called intercalation. Most intercalators are aromatic and planar molecules; examples include ethidium bromide, acridines, daunomycin, and doxorubicin. For an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate, distorting the DNA strands by unwinding of the double helix. This inhibits both transcription and DNA replication, causing toxicity and mutations.[91] As a result, DNA intercalators may be carcinogens, and in the case of thalidomide, a teratogen.[92] Others such as benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide and aflatoxin form DNA adducts that induce errors in replication.[93] Nevertheless, due to their ability to inhibit DNA transcription and replication, other similar toxins are also used in chemotherapy to inhibit rapidly growing cancer cells.[94]

Biological functions

Location of eukaryote nuclear DNA within the chromosomes

DNA usually occurs as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. The set of chromosomes in a cell makes up its genome; the human genome has approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes.[95] The information carried by DNA is held in the sequence of pieces of DNA called genes. Transmission of genetic information in genes is achieved via complementary base pairing. For example, in transcription, when a cell uses the information in a gene, the DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA sequence through the attraction between the DNA and the correct RNA nucleotides. Usually, this RNA copy is then used to make a matching protein sequence in a process called translation, which depends on the same interaction between RNA nucleotides. In an alternative fashion, a cell may copy its genetic information in a process called DNA replication. The details of these functions are covered in other articles; here the focus is on the interactions between DNA and other molecules that mediate the function of the genome.

Genes and genomes

Genomic DNA is tightly and orderly packed in the process called DNA condensation, to fit the small available volumes of the cell. In eukaryotes, DNA is located in the cell nucleus, with small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.[96] The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the complete set of this information in an organism is called its genotype. A gene is a unit of heredity and is a region of DNA that influences a particular characteristic in an organism. Genes contain an open reading frame that can be transcribed, and regulatory sequences such as promoters and enhancers, which control transcription of the open reading frame.

In many species, only a small fraction of the total sequence of the genome encodes protein. For example, only about 1.5% of the human genome consists of protein-coding exons, with over 50% of human DNA consisting of non-coding repetitive sequences.[97] The reasons for the presence of so much noncoding DNA in eukaryotic genomes and the extraordinary differences in genome size, or C-value, among species, represent a long-standing puzzle known as the «C-value enigma».[98] However, some DNA sequences that do not code protein may still encode functional non-coding RNA molecules, which are involved in the regulation of gene expression.[99]

Some noncoding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes. Telomeres and centromeres typically contain few genes but are important for the function and stability of chromosomes.[63][101] An abundant form of noncoding DNA in humans are pseudogenes, which are copies of genes that have been disabled by mutation.[102] These sequences are usually just molecular fossils, although they can occasionally serve as raw genetic material for the creation of new genes through the process of gene duplication and divergence.[103]

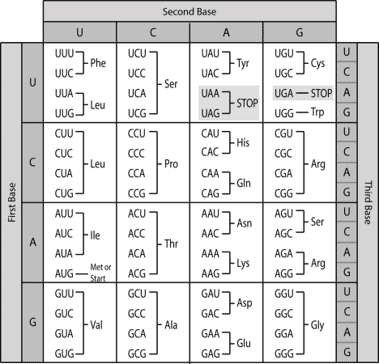

Transcription and translation

A gene is a sequence of DNA that contains genetic information and can influence the phenotype of an organism. Within a gene, the sequence of bases along a DNA strand defines a messenger RNA sequence, which then defines one or more protein sequences. The relationship between the nucleotide sequences of genes and the amino-acid sequences of proteins is determined by the rules of translation, known collectively as the genetic code. The genetic code consists of three-letter ‘words’ called codons formed from a sequence of three nucleotides (e.g. ACT, CAG, TTT).

In transcription, the codons of a gene are copied into messenger RNA by RNA polymerase. This RNA copy is then decoded by a ribosome that reads the RNA sequence by base-pairing the messenger RNA to transfer RNA, which carries amino acids. Since there are 4 bases in 3-letter combinations, there are 64 possible codons (43 combinations). These encode the twenty standard amino acids, giving most amino acids more than one possible codon. There are also three ‘stop’ or ‘nonsense’ codons signifying the end of the coding region; these are the TAG, TAA, and TGA codons, (UAG, UAA, and UGA on the mRNA).

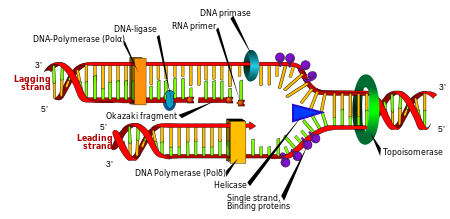

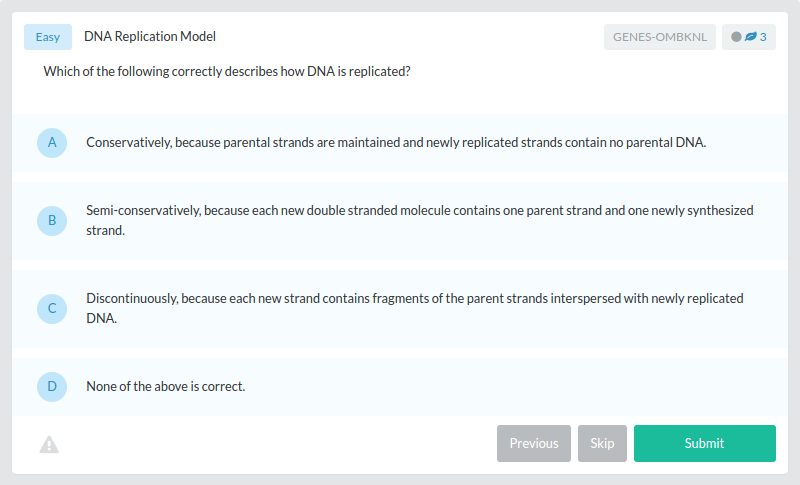

Replication

Cell division is essential for an organism to grow, but, when a cell divides, it must replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure of DNA provides a simple mechanism for DNA replication. Here, the two strands are separated and then each strand’s complementary DNA sequence is recreated by an enzyme called DNA polymerase. This enzyme makes the complementary strand by finding the correct base through complementary base pairing and bonding it onto the original strand. As DNA polymerases can only extend a DNA strand in a 5′ to 3′ direction, different mechanisms are used to copy the antiparallel strands of the double helix.[104] In this way, the base on the old strand dictates which base appears on the new strand, and the cell ends up with a perfect copy of its DNA.

Naked extracellular DNA (eDNA), most of it released by cell death, is nearly ubiquitous in the environment. Its concentration in soil may be as high as 2 μg/L, and its concentration in natural aquatic environments may be as high at 88 μg/L.[105] Various possible functions have been proposed for eDNA: it may be involved in horizontal gene transfer;[106] it may provide nutrients;[107] and it may act as a buffer to recruit or titrate ions or antibiotics.[108] Extracellular DNA acts as a functional extracellular matrix component in the biofilms of several bacterial species. It may act as a recognition factor to regulate the attachment and dispersal of specific cell types in the biofilm;[109] it may contribute to biofilm formation;[110] and it may contribute to the biofilm’s physical strength and resistance to biological stress.[111]

Cell-free fetal DNA is found in the blood of the mother, and can be sequenced to determine a great deal of information about the developing fetus.[112]

Under the name of environmental DNA eDNA has seen increased use in the natural sciences as a survey tool for ecology, monitoring the movements and presence of species in water, air, or on land, and assessing an area’s biodiversity.[113][114]

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are networks of extracellular fibers, primarily composed of DNA, which allow neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, to kill extracellular pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cells.

Interactions with proteins

All the functions of DNA depend on interactions with proteins. These protein interactions can be non-specific, or the protein can bind specifically to a single DNA sequence. Enzymes can also bind to DNA and of these, the polymerases that copy the DNA base sequence in transcription and DNA replication are particularly important.

DNA-binding proteins

Interaction of DNA (in orange) with histones (in blue). These proteins’ basic amino acids bind to the acidic phosphate groups on DNA.

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held in complexes with structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA into a compact structure called chromatin. In eukaryotes, this structure involves DNA binding to a complex of small basic proteins called histones, while in prokaryotes multiple types of proteins are involved.[115][116] The histones form a disk-shaped complex called a nucleosome, which contains two complete turns of double-stranded DNA wrapped around its surface. These non-specific interactions are formed through basic residues in the histones, making ionic bonds to the acidic sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA, and are thus largely independent of the base sequence.[117] Chemical modifications of these basic amino acid residues include methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation.[118] These chemical changes alter the strength of the interaction between the DNA and the histones, making the DNA more or less accessible to transcription factors and changing the rate of transcription.[119] Other non-specific DNA-binding proteins in chromatin include the high-mobility group proteins, which bind to bent or distorted DNA.[120] These proteins are important in bending arrays of nucleosomes and arranging them into the larger structures that make up chromosomes.[121]

A distinct group of DNA-binding proteins is the DNA-binding proteins that specifically bind single-stranded DNA. In humans, replication protein A is the best-understood member of this family and is used in processes where the double helix is separated, including DNA replication, recombination, and DNA repair.[122] These binding proteins seem to stabilize single-stranded DNA and protect it from forming stem-loops or being degraded by nucleases.

In contrast, other proteins have evolved to bind to particular DNA sequences. The most intensively studied of these are the various transcription factors, which are proteins that regulate transcription. Each transcription factor binds to one particular set of DNA sequences and activates or inhibits the transcription of genes that have these sequences close to their promoters. The transcription factors do this in two ways. Firstly, they can bind the RNA polymerase responsible for transcription, either directly or through other mediator proteins; this locates the polymerase at the promoter and allows it to begin transcription.[124] Alternatively, transcription factors can bind enzymes that modify the histones at the promoter. This changes the accessibility of the DNA template to the polymerase.[125]

As these DNA targets can occur throughout an organism’s genome, changes in the activity of one type of transcription factor can affect thousands of genes.[126] Consequently, these proteins are often the targets of the signal transduction processes that control responses to environmental changes or cellular differentiation and development. The specificity of these transcription factors’ interactions with DNA come from the proteins making multiple contacts to the edges of the DNA bases, allowing them to «read» the DNA sequence. Most of these base-interactions are made in the major groove, where the bases are most accessible.[24]

DNA-modifying enzymes

Nucleases and ligases

Nucleases are enzymes that cut DNA strands by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds. Nucleases that hydrolyse nucleotides from the ends of DNA strands are called exonucleases, while endonucleases cut within strands. The most frequently used nucleases in molecular biology are the restriction endonucleases, which cut DNA at specific sequences. For instance, the EcoRV enzyme shown to the left recognizes the 6-base sequence 5′-GATATC-3′ and makes a cut at the horizontal line. In nature, these enzymes protect bacteria against phage infection by digesting the phage DNA when it enters the bacterial cell, acting as part of the restriction modification system.[128] In technology, these sequence-specific nucleases are used in molecular cloning and DNA fingerprinting.

Enzymes called DNA ligases can rejoin cut or broken DNA strands.[129] Ligases are particularly important in lagging strand DNA replication, as they join the short segments of DNA produced at the replication fork into a complete copy of the DNA template. They are also used in DNA repair and genetic recombination.[129]

Topoisomerases and helicases

Topoisomerases are enzymes with both nuclease and ligase activity. These proteins change the amount of supercoiling in DNA. Some of these enzymes work by cutting the DNA helix and allowing one section to rotate, thereby reducing its level of supercoiling; the enzyme then seals the DNA break.[43] Other types of these enzymes are capable of cutting one DNA helix and then passing a second strand of DNA through this break, before rejoining the helix.[130] Topoisomerases are required for many processes involving DNA, such as DNA replication and transcription.[44]

Helicases are proteins that are a type of molecular motor. They use the chemical energy in nucleoside triphosphates, predominantly adenosine triphosphate (ATP), to break hydrogen bonds between bases and unwind the DNA double helix into single strands.[131] These enzymes are essential for most processes where enzymes need to access the DNA bases.

Polymerases

Polymerases are enzymes that synthesize polynucleotide chains from nucleoside triphosphates. The sequence of their products is created based on existing polynucleotide chains—which are called templates. These enzymes function by repeatedly adding a nucleotide to the 3′ hydroxyl group at the end of the growing polynucleotide chain. As a consequence, all polymerases work in a 5′ to 3′ direction.[132] In the active site of these enzymes, the incoming nucleoside triphosphate base-pairs to the template: this allows polymerases to accurately synthesize the complementary strand of their template. Polymerases are classified according to the type of template that they use.

In DNA replication, DNA-dependent DNA polymerases make copies of DNA polynucleotide chains. To preserve biological information, it is essential that the sequence of bases in each copy are precisely complementary to the sequence of bases in the template strand. Many DNA polymerases have a proofreading activity. Here, the polymerase recognizes the occasional mistakes in the synthesis reaction by the lack of base pairing between the mismatched nucleotides. If a mismatch is detected, a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is activated and the incorrect base removed.[133] In most organisms, DNA polymerases function in a large complex called the replisome that contains multiple accessory subunits, such as the DNA clamp or helicases.[134]

RNA-dependent DNA polymerases are a specialized class of polymerases that copy the sequence of an RNA strand into DNA. They include reverse transcriptase, which is a viral enzyme involved in the infection of cells by retroviruses, and telomerase, which is required for the replication of telomeres.[62][135] For example, HIV reverse transcriptase is an enzyme for AIDS virus replication.[135] Telomerase is an unusual polymerase because it contains its own RNA template as part of its structure. It synthesizes telomeres at the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres prevent fusion of the ends of neighboring chromosomes and protect chromosome ends from damage.[63]

Transcription is carried out by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase that copies the sequence of a DNA strand into RNA. To begin transcribing a gene, the RNA polymerase binds to a sequence of DNA called a promoter and separates the DNA strands. It then copies the gene sequence into a messenger RNA transcript until it reaches a region of DNA called the terminator, where it halts and detaches from the DNA. As with human DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, RNA polymerase II, the enzyme that transcribes most of the genes in the human genome, operates as part of a large protein complex with multiple regulatory and accessory subunits.[136]

Genetic recombination

A current model of meiotic recombination, initiated by a double-strand break or gap, followed by pairing with an homologous chromosome and strand invasion to initiate the recombinational repair process. Repair of the gap can lead to crossover (CO) or non-crossover (NCO) of the flanking regions. CO recombination is thought to occur by the Double Holliday Junction (DHJ) model, illustrated on the right, above. NCO recombinants are thought to occur primarily by the Synthesis Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA) model, illustrated on the left, above. Most recombination events appear to be the SDSA type.

A DNA helix usually does not interact with other segments of DNA, and in human cells, the different chromosomes even occupy separate areas in the nucleus called «chromosome territories».[138] This physical separation of different chromosomes is important for the ability of DNA to function as a stable repository for information, as one of the few times chromosomes interact is in chromosomal crossover which occurs during sexual reproduction, when genetic recombination occurs. Chromosomal crossover is when two DNA helices break, swap a section and then rejoin.

Recombination allows chromosomes to exchange genetic information and produces new combinations of genes, which increases the efficiency of natural selection and can be important in the rapid evolution of new proteins.[139] Genetic recombination can also be involved in DNA repair, particularly in the cell’s response to double-strand breaks.[140]

The most common form of chromosomal crossover is homologous recombination, where the two chromosomes involved share very similar sequences. Non-homologous recombination can be damaging to cells, as it can produce chromosomal translocations and genetic abnormalities. The recombination reaction is catalyzed by enzymes known as recombinases, such as RAD51.[141] The first step in recombination is a double-stranded break caused by either an endonuclease or damage to the DNA.[142] A series of steps catalyzed in part by the recombinase then leads to joining of the two helices by at least one Holliday junction, in which a segment of a single strand in each helix is annealed to the complementary strand in the other helix. The Holliday junction is a tetrahedral junction structure that can be moved along the pair of chromosomes, swapping one strand for another. The recombination reaction is then halted by cleavage of the junction and re-ligation of the released DNA.[143] Only strands of like polarity exchange DNA during recombination. There are two types of cleavage: east-west cleavage and north–south cleavage. The north–south cleavage nicks both strands of DNA, while the east–west cleavage has one strand of DNA intact. The formation of a Holliday junction during recombination makes it possible for genetic diversity, genes to exchange on chromosomes, and expression of wild-type viral genomes.

Evolution

DNA contains the genetic information that allows all forms of life to function, grow and reproduce. However, it is unclear how long in the 4-billion-year history of life DNA has performed this function, as it has been proposed that the earliest forms of life may have used RNA as their genetic material.[144][145] RNA may have acted as the central part of early cell metabolism as it can both transmit genetic information and carry out catalysis as part of ribozymes.[146] This ancient RNA world where nucleic acid would have been used for both catalysis and genetics may have influenced the evolution of the current genetic code based on four nucleotide bases. This would occur, since the number of different bases in such an organism is a trade-off between a small number of bases increasing replication accuracy and a large number of bases increasing the catalytic efficiency of ribozymes.[147] However, there is no direct evidence of ancient genetic systems, as recovery of DNA from most fossils is impossible because DNA survives in the environment for less than one million years, and slowly degrades into short fragments in solution.[148] Claims for older DNA have been made, most notably a report of the isolation of a viable bacterium from a salt crystal 250 million years old,[149] but these claims are controversial.[150][151]

Building blocks of DNA (adenine, guanine, and related organic molecules) may have been formed extraterrestrially in outer space.[152][153][154] Complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine, and thymine, have also been formed in the laboratory under conditions mimicking those found in outer space, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar cosmic dust and gas clouds.[155]

In February 2021, scientists reported, for the first time, the sequencing of DNA from animal remains, a mammoth in this instance over a million years old, the oldest DNA sequenced to date.[156][157]

Uses in technology

Genetic engineering

Methods have been developed to purify DNA from organisms, such as phenol-chloroform extraction, and to manipulate it in the laboratory, such as restriction digests and the polymerase chain reaction. Modern biology and biochemistry make intensive use of these techniques in recombinant DNA technology. Recombinant DNA is a man-made DNA sequence that has been assembled from other DNA sequences. They can be transformed into organisms in the form of plasmids or in the appropriate format, by using a viral vector.[158] The genetically modified organisms produced can be used to produce products such as recombinant proteins, used in medical research,[159] or be grown in agriculture.[160][161]

DNA profiling

Forensic scientists can use DNA in blood, semen, skin, saliva or hair found at a crime scene to identify a matching DNA of an individual, such as a perpetrator.[162] This process is formally termed DNA profiling, also called DNA fingerprinting. In DNA profiling, the lengths of variable sections of repetitive DNA, such as short tandem repeats and minisatellites, are compared between people. This method is usually an extremely reliable technique for identifying a matching DNA.[163] However, identification can be complicated if the scene is contaminated with DNA from several people.[164] DNA profiling was developed in 1984 by British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys,[165] and first used in forensic science to convict Colin Pitchfork in the 1988 Enderby murders case.[166]

The development of forensic science and the ability to now obtain genetic matching on minute samples of blood, skin, saliva, or hair has led to re-examining many cases. Evidence can now be uncovered that was scientifically impossible at the time of the original examination. Combined with the removal of the double jeopardy law in some places, this can allow cases to be reopened where prior trials have failed to produce sufficient evidence to convince a jury. People charged with serious crimes may be required to provide a sample of DNA for matching purposes. The most obvious defense to DNA matches obtained forensically is to claim that cross-contamination of evidence has occurred. This has resulted in meticulous strict handling procedures with new cases of serious crime.

DNA profiling is also used successfully to positively identify victims of mass casualty incidents,[167] bodies or body parts in serious accidents, and individual victims in mass war graves, via matching to family members.

DNA profiling is also used in DNA paternity testing to determine if someone is the biological parent or grandparent of a child with the probability of parentage is typically 99.99% when the alleged parent is biologically related to the child. Normal DNA sequencing methods happen after birth, but there are new methods to test paternity while a mother is still pregnant.[168]

DNA enzymes or catalytic DNA

Deoxyribozymes, also called DNAzymes or catalytic DNA, were first discovered in 1994.[169] They are mostly single stranded DNA sequences isolated from a large pool of random DNA sequences through a combinatorial approach called in vitro selection or systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX). DNAzymes catalyze variety of chemical reactions including RNA-DNA cleavage, RNA-DNA ligation, amino acids phosphorylation-dephosphorylation, carbon-carbon bond formation, etc. DNAzymes can enhance catalytic rate of chemical reactions up to 100,000,000,000-fold over the uncatalyzed reaction.[170] The most extensively studied class of DNAzymes is RNA-cleaving types which have been used to detect different metal ions and designing therapeutic agents. Several metal-specific DNAzymes have been reported including the GR-5 DNAzyme (lead-specific),[169] the CA1-3 DNAzymes (copper-specific),[171] the 39E DNAzyme (uranyl-specific) and the NaA43 DNAzyme (sodium-specific).[172] The NaA43 DNAzyme, which is reported to be more than 10,000-fold selective for sodium over other metal ions, was used to make a real-time sodium sensor in cells.

Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics involves the development of techniques to store, data mine, search and manipulate biological data, including DNA nucleic acid sequence data. These have led to widely applied advances in computer science, especially string searching algorithms, machine learning, and database theory.[173] String searching or matching algorithms, which find an occurrence of a sequence of letters inside a larger sequence of letters, were developed to search for specific sequences of nucleotides.[174] The DNA sequence may be aligned with other DNA sequences to identify homologous sequences and locate the specific mutations that make them distinct. These techniques, especially multiple sequence alignment, are used in studying phylogenetic relationships and protein function.[175] Data sets representing entire genomes’ worth of DNA sequences, such as those produced by the Human Genome Project, are difficult to use without the annotations that identify the locations of genes and regulatory elements on each chromosome. Regions of DNA sequence that have the characteristic patterns associated with protein- or RNA-coding genes can be identified by gene finding algorithms, which allow researchers to predict the presence of particular gene products and their possible functions in an organism even before they have been isolated experimentally.[176] Entire genomes may also be compared, which can shed light on the evolutionary history of particular organism and permit the examination of complex evolutionary events.

DNA nanotechnology

DNA nanotechnology uses the unique molecular recognition properties of DNA and other nucleic acids to create self-assembling branched DNA complexes with useful properties.[178] DNA is thus used as a structural material rather than as a carrier of biological information. This has led to the creation of two-dimensional periodic lattices (both tile-based and using the DNA origami method) and three-dimensional structures in the shapes of polyhedra.[179] Nanomechanical devices and algorithmic self-assembly have also been demonstrated,[180] and these DNA structures have been used to template the arrangement of other molecules such as gold nanoparticles and streptavidin proteins.[181] DNA and other nucleic acids are the basis of aptamers, synthetic oligonucleotide ligands for specific target molecules used in a range of biotechnology and biomedical applications.[182]

History and anthropology

Because DNA collects mutations over time, which are then inherited, it contains historical information, and, by comparing DNA sequences, geneticists can infer the evolutionary history of organisms, their phylogeny.[183] This field of phylogenetics is a powerful tool in evolutionary biology. If DNA sequences within a species are compared, population geneticists can learn the history of particular populations. This can be used in studies ranging from ecological genetics to anthropology.

Information storage

DNA as a storage device for information has enormous potential since it has much higher storage density compared to electronic devices. However, high costs, slow read and write times (memory latency), and insufficient reliability has prevented its practical use.[184][185]

History

Maclyn McCarty (left) shakes hands with Francis Crick and James Watson, co-originators of the double-helix model based on the X-ray diffraction data and insights of Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling.

Pencil sketch of the DNA double helix by Francis Crick in 1953

DNA was first isolated by the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher who, in 1869, discovered a microscopic substance in the pus of discarded surgical bandages. As it resided in the nuclei of cells, he called it «nuclein».[186][187] In 1878, Albrecht Kossel isolated the non-protein component of «nuclein», nucleic acid, and later isolated its five primary nucleobases.[188][189]

In 1909, Phoebus Levene identified the base, sugar, and phosphate nucleotide unit of RNA (then named «yeast nucleic acid»).[190][191][192] In 1929, Levene identified deoxyribose sugar in «thymus nucleic acid» (DNA).[193] Levene suggested that DNA consisted of a string of four nucleotide units linked together through the phosphate groups («tetranucleotide hypothesis»). Levene thought the chain was short and the bases repeated in a fixed order. In 1927, Nikolai Koltsov proposed that inherited traits would be inherited via a «giant hereditary molecule» made up of «two mirror strands that would replicate in a semi-conservative fashion using each strand as a template».[194][195] In 1928, Frederick Griffith in his experiment discovered that traits of the «smooth» form of Pneumococcus could be transferred to the «rough» form of the same bacteria by mixing killed «smooth» bacteria with the live «rough» form.[196][197] This system provided the first clear suggestion that DNA carries genetic information.

In 1933, while studying virgin sea urchin eggs, Jean Brachet suggested that DNA is found in the cell nucleus and that RNA is present exclusively in the cytoplasm. At the time, «yeast nucleic acid» (RNA) was thought to occur only in plants, while «thymus nucleic acid» (DNA) only in animals. The latter was thought to be a tetramer, with the function of buffering cellular pH.[198][199]

In 1937, William Astbury produced the first X-ray diffraction patterns that showed that DNA had a regular structure.[200]

In 1943, Oswald Avery, along with co-workers Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty, identified DNA as the transforming principle, supporting Griffith’s suggestion (Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment).[201] Erwin Chargaff developed and published observations now known as Chargaff’s rules, stating that in DNA from any species of any organism, the amount of guanine should be equal to cytosine and the amount of adenine should be equal to thymine.[202][203] Late in 1951, Francis Crick started working with James Watson at the Cavendish Laboratory within the University of Cambridge. DNA’s role in heredity was confirmed in 1952 when Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase in the Hershey–Chase experiment showed that DNA is the genetic material of the enterobacteria phage T2.[204]

In May 1952, Raymond Gosling, a graduate student working under the supervision of Rosalind Franklin, took an X-ray diffraction image, labeled as «Photo 51»,[205] at high hydration levels of DNA. This photo was given to Watson and Crick by Maurice Wilkins and was critical to their obtaining the correct structure of DNA. Franklin told Crick and Watson that the backbones had to be on the outside. Before then, Linus Pauling, and Watson and Crick, had erroneous models with the chains inside and the bases pointing outwards. Franklin’s identification of the space group for DNA crystals revealed to Crick that the two DNA strands were antiparallel.[206] In February 1953, Linus Pauling and Robert Corey proposed a model for nucleic acids containing three intertwined chains, with the phosphates near the axis, and the bases on the outside.[207] Watson and Crick completed their model, which is now accepted as the first correct model of the double helix of DNA. On 28 February 1953 Crick interrupted patrons’ lunchtime at The Eagle pub in Cambridge to announce that he and Watson had «discovered the secret of life».[208]

The 25 April 1953 issue of the journal Nature published a series of five articles giving the Watson and Crick double-helix structure DNA and evidence supporting it.[209] The structure was reported in a letter titled «MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF NUCLEIC ACIDS A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid«, in which they said, «It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.»[9] This letter was followed by a letter from Franklin and Gosling, which was the first publication of their own X-ray diffraction data and of their original analysis method.[47][210] Then followed a letter by Wilkins and two of his colleagues, which contained an analysis of in vivo B-DNA X-ray patterns, and which supported the presence in vivo of the Watson and Crick structure.[48]

In 1962, after Franklin’s death, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[211] Nobel Prizes are awarded only to living recipients. A debate continues about who should receive credit for the discovery.[212]

In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the central dogma of molecular biology, which foretold the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, and articulated the «adaptor hypothesis».[213] Final confirmation of the replication mechanism that was implied by the double-helical structure followed in 1958 through the Meselson–Stahl experiment.[214] Further work by Crick and co-workers showed that the genetic code was based on non-overlapping triplets of bases, called codons, allowing Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley, and Marshall Warren Nirenberg to decipher the genetic code.[215] These findings represent the birth of molecular biology.[216]

See also

- Autosome – Any chromosome other than a sex chromosome

- Crystallography – Scientific study of crystal structures

- DNA Day – Holiday celebrated on April 25

- DNA microarray – Collection of microscopic DNA spots attached to a solid surface

- DNA sequencing – Process of determining the nucleic acid sequence

- Genetic disorder – Health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome

- Genetic genealogy – DNA testing to infer relationships

- Haplotype – Group of genes from one parent

- Meiosis – Cell division producing haploid gametes

- Nucleic acid notation – Universal notation using the Roman characters A, C, G, and T to call the four DNA nucleotides

- Nucleic acid sequence – Succession of nucleotides in a nucleic acid

- Ribosomal DNA – specific region of DNA that that codes for ribosomal RNA

- Southern blot – DNA analysis technique

- X-ray scattering techniques – family of non-destructive analytical techniques

- Xeno nucleic acid – group of compounds

References

- ^ «deoxyribonucleic acid». Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2014). Molecular Biology of the Cell (6th ed.). Garland. p. Chapter 4: DNA, Chromosomes and Genomes. ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ Purcell A. «DNA». Basic Biology. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017.

- ^ «Uracil». Genome.gov. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Russell P (2001). iGenetics. New York: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-4553-1.

- ^ Saenger W (1984). Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90762-9.

- ^ a b Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Peter W (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (Fourth ed.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. OCLC 145080076. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016.

- ^ Irobalieva RN, Fogg JM, Catanese DJ, Catanese DJ, Sutthibutpong T, Chen M, Barker AK, Ludtke SJ, Harris SA, Schmid MF, Chiu W, Zechiedrich L (October 2015). «Structural diversity of supercoiled DNA». Nature Communications. 6: 8440. Bibcode:2015NatCo…6.8440I. doi:10.1038/ncomms9440. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4608029. PMID 26455586.

- ^ a b c d Watson JD, Crick FH (April 1953). «Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid» (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 737–38. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..737W. doi:10.1038/171737a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13054692. S2CID 4253007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2007.

- ^ Mandelkern M, Elias JG, Eden D, Crothers DM (October 1981). «The dimensions of DNA in solution». Journal of Molecular Biology. 152 (1): 153–61. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(81)90099-1. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 7338906.

- ^ a b c d Berg J, Tymoczko J, Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6.

- ^ IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (CBN) (December 1970). «Abbreviations and Symbols for Nucleic Acids, Polynucleotides and their Constituents. Recommendations 1970». The Biochemical Journal. 120 (3): 449–54. doi:10.1042/bj1200449. ISSN 0306-3283. PMC 1179624. PMID 5499957. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- ^ a b Ghosh A, Bansal M (April 2003). «A glossary of DNA structures from A to Z». Acta Crystallographica Section D. 59 (Pt 4): 620–26. doi:10.1107/S0907444903003251. ISSN 0907-4449. PMID 12657780.

- ^ Bank, RCSB Protein Data. «RCSB PDB — 1D65: MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF THE B-DNA DODECAMER D(CGCAAATTTGCG)2; AN EXAMINATION OF PROPELLER TWIST AND MINOR-GROOVE WATER STRUCTURE AT 2.2 ANGSTROMS RESOLUTION». www.rcsb.org. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Yakovchuk P, Protozanova E, Frank-Kamenetskii MD (2006). «Base-stacking and base-pairing contributions into thermal stability of the DNA double helix». Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (2): 564–74. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj454. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 1360284. PMID 16449200.

- ^ Tropp BE (2012). Molecular Biology (4th ed.). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Barlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-8663-2.

- ^ Carr S (1953). «Watson-Crick Structure of DNA». Memorial University of Newfoundland. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Verma S, Eckstein F (1998). «Modified oligonucleotides: synthesis and strategy for users». Annual Review of Biochemistry. 67: 99–134. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.99. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 9759484.

- ^ Johnson TB, Coghill RD (1925). «Pyrimidines. CIII. The discovery of 5-methylcytosine in tuberculinic acid, the nucleic acid of the tubercle bacillus». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 47: 2838–44. doi:10.1021/ja01688a030. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Weigele P, Raleigh EA (October 2016). «Biosynthesis and Function of Modified Bases in Bacteria and Their Viruses». Chemical Reviews. 116 (20): 12655–12687. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00114. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 27319741.

- ^ Kumar S, Chinnusamy V, Mohapatra T (2018). «Epigenetics of Modified DNA Bases: 5-Methylcytosine and Beyond». Frontiers in Genetics. 9: 640. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00640. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 6305559. PMID 30619465.

- ^ Carell T, Kurz MQ, Müller M, Rossa M, Spada F (April 2018). «Non-canonical Bases in the Genome: The Regulatory Information Layer in DNA». Angewandte Chemie. 57 (16): 4296–4312. doi:10.1002/anie.201708228. PMID 28941008.

- ^ Wing R, Drew H, Takano T, Broka C, Tanaka S, Itakura K, Dickerson RE (October 1980). «Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA». Nature. 287 (5784): 755–58. Bibcode:1980Natur.287..755W. doi:10.1038/287755a0. PMID 7432492. S2CID 4315465.

- ^ a b Pabo CO, Sauer RT (1984). «Protein-DNA recognition». Annual Review of Biochemistry. 53: 293–321. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001453. PMID 6236744.

- ^ Nikolova EN, Zhou H, Gottardo FL, Alvey HS, Kimsey IJ, Al-Hashimi HM (2013). «A historical account of Hoogsteen base-pairs in duplex DNA». Biopolymers. 99 (12): 955–68. doi:10.1002/bip.22334. PMC 3844552. PMID 23818176.

- ^ Clausen-Schaumann H, Rief M, Tolksdorf C, Gaub HE (April 2000). «Mechanical stability of single DNA molecules». Biophysical Journal. 78 (4): 1997–2007. Bibcode:2000BpJ….78.1997C. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76747-6. PMC 1300792. PMID 10733978.

- ^ Chalikian TV, Völker J, Plum GE, Breslauer KJ (July 1999). «A more unified picture for the thermodynamics of nucleic acid duplex melting: a characterization by calorimetric and volumetric techniques». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (14): 7853–58. Bibcode:1999PNAS…96.7853C. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.14.7853. PMC 22151. PMID 10393911.

- ^ deHaseth PL, Helmann JD (June 1995). «Open complex formation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: the mechanism of polymerase-induced strand separation of double helical DNA». Molecular Microbiology. 16 (5): 817–24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02309.x. PMID 7476180. S2CID 24479358.

- ^ Isaksson J, Acharya S, Barman J, Cheruku P, Chattopadhyaya J (December 2004). «Single-stranded adenine-rich DNA and RNA retain structural characteristics of their respective double-stranded conformations and show directional differences in stacking pattern» (PDF). Biochemistry. 43 (51): 15996–6010. doi:10.1021/bi048221v. PMID 15609994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 June 2007.

- ^ a b Piovesan A, Pelleri MC, Antonaros F, Strippoli P, Caracausi M, Vitale L (2019). «On the length, weight and GC content of the human genome». BMC Res Notes. 12 (1): 106. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4137-z. PMC 6391780. PMID 30813969.

- ^ Gregory SG, Barlow KF, McLay KE, Kaul R, Swarbreck D, Dunham A, et al. (May 2006). «The DNA sequence and biological annotation of human chromosome 1». Nature. 441 (7091): 315–21. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..315G. doi:10.1038/nature04727. PMID 16710414.

- ^ Anderson, S.; Bankier, A. T.; Barrell, B. G.; de Bruijn, M. H. L.; Coulson, A. R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I. C.; Nierlich, D. P.; Roe, B. A.; Sanger, F.; Schreier, P. H.; Smith, A. J. H.; Staden, R.; Young, I. G. (April 1981). «Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome». Nature. 290 (5806): 457–465. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A. doi:10.1038/290457a0. PMID 7219534. S2CID 4355527.

- ^ «Untitled». Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Satoh, M; Kuroiwa, T (September 1991). «Organization of multiple nucleoids and DNA molecules in mitochondria of a human cell». Experimental Cell Research. 196 (1): 137–140. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(91)90467-9. PMID 1715276.

- ^ Zhang D, Keilty D, Zhang ZF, Chian RC (2017). «Mitochondria in oocyte aging: current understanding». Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 9 (1): 29–38. PMC 5506767. PMID 28721182.

- ^ «Chemistry — Queen Mary University of London». www.qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Hüttenhofer A, Schattner P, Polacek N (May 2005). «Non-coding RNAs: hope or hype?». Trends in Genetics. 21 (5): 289–97. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.03.007. PMID 15851066.

- ^ Munroe SH (November 2004). «Diversity of antisense regulation in eukaryotes: multiple mechanisms, emerging patterns». Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 93 (4): 664–71. doi:10.1002/jcb.20252. PMID 15389973. S2CID 23748148.

- ^ Makalowska I, Lin CF, Makalowski W (February 2005). «Overlapping genes in vertebrate genomes». Computational Biology and Chemistry. 29 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2004.12.006. PMID 15680581.

- ^ Johnson ZI, Chisholm SW (November 2004). «Properties of overlapping genes are conserved across microbial genomes». Genome Research. 14 (11): 2268–72. doi:10.1101/gr.2433104. PMC 525685. PMID 15520290.

- ^ Lamb RA, Horvath CM (August 1991). «Diversity of coding strategies in influenza viruses». Trends in Genetics. 7 (8): 261–66. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(91)90326-L. PMC 7173306. PMID 1771674.

- ^ Benham CJ, Mielke SP (2005). «DNA mechanics» (PDF). Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 7: 21–53. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.062403.132016. PMID 16004565. S2CID 1427671. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2019.

- ^ a b Champoux JJ (2001). «DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism» (PDF). Annual Review of Biochemistry. 70: 369–413. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. PMID 11395412. S2CID 18144189.

- ^ a b Wang JC (June 2002). «Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective». Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 3 (6): 430–40. doi:10.1038/nrm831. PMID 12042765. S2CID 205496065.

- ^ Basu HS, Feuerstein BG, Zarling DA, Shafer RH, Marton LJ (October 1988). «Recognition of Z-RNA and Z-DNA determinants by polyamines in solution: experimental and theoretical studies». Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics. 6 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1080/07391102.1988.10507714. PMID 2482766.

- ^

- Franklin RE, Gosling RG (6 March 1953). «The Structure of Sodium Thymonucleate Fibres I. The Influence of Water Content» (PDF). Acta Crystallogr. 6 (8–9): 673–77. doi:10.1107/S0365110X53001939. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2016.

- Franklin RE, Gosling RG (1953). «The structure of sodium thymonucleate fibres. II. The cylindrically symmetrical Patterson function» (PDF). Acta Crystallogr. 6 (8–9): 678–85. doi:10.1107/S0365110X53001940. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2017.

- ^ a b Franklin RE, Gosling RG (April 1953). «Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate» (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 740–41. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..740F. doi:10.1038/171740a0. PMID 13054694. S2CID 4268222. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2011.

- ^ a b Wilkins MH, Stokes AR, Wilson HR (April 1953). «Molecular structure of deoxypentose nucleic acids» (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 738–40. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..738W. doi:10.1038/171738a0. PMID 13054693. S2CID 4280080. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ Leslie AG, Arnott S, Chandrasekaran R, Ratliff RL (October 1980). «Polymorphism of DNA double helices». Journal of Molecular Biology. 143 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(80)90124-2. PMID 7441761.

- ^ Baianu IC (1980). «Structural Order and Partial Disorder in Biological systems». Bull. Math. Biol. 42 (4): 137–41. doi:10.1007/BF02462372. S2CID 189888972.

- ^ Hosemann R, Bagchi RN (1962). Direct analysis of diffraction by matter. Amsterdam – New York: North-Holland Publishers.

- ^ Baianu IC (1978). «X-ray scattering by partially disordered membrane systems» (PDF). Acta Crystallogr A. 34 (5): 751–53. Bibcode:1978AcCrA..34..751B. doi:10.1107/S0567739478001540. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Wahl MC, Sundaralingam M (1997). «Crystal structures of A-DNA duplexes». Biopolymers. 44 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:1<45::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 9097733.

- ^ Lu XJ, Shakked Z, Olson WK (July 2000). «A-form conformational motifs in ligand-bound DNA structures». Journal of Molecular Biology. 300 (4): 819–40. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3690. PMID 10891271.

- ^ Rothenburg S, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F (December 2001). «DNA methylation and Z-DNA formation as mediators of quantitative differences in the expression of alleles». Immunological Reviews. 184: 286–98. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840125.x. PMID 12086319. S2CID 20589136.

- ^ Oh DB, Kim YG, Rich A (December 2002). «Z-DNA-binding proteins can act as potent effectors of gene expression in vivo». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 16666–71. Bibcode:2002PNAS…9916666O. doi:10.1073/pnas.262672699. PMC 139201. PMID 12486233.

- ^ Palmer J (2 December 2010). «Arsenic-loving bacteria may help in hunt for alien life». BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ a b Bortman H (2 December 2010). «Arsenic-Eating Bacteria Opens New Possibilities for Alien Life». Space.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Katsnelson A (2 December 2010). «Arsenic-eating microbe may redefine chemistry of life». Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.645. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- ^ Cressey D (3 October 2012). «‘Arsenic-life’ Bacterium Prefers Phosphorus after all». Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11520. S2CID 87341731.

- ^ «Structure Summary for 1KF1». ndbserver.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b Greider CW, Blackburn EH (December 1985). «Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts». Cell. 43 (2 Pt 1): 405–13. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. PMID 3907856.

- ^ a b c Nugent CI, Lundblad V (April 1998). «The telomerase reverse transcriptase: components and regulation». Genes & Development. 12 (8): 1073–85. doi:10.1101/gad.12.8.1073. PMID 9553037.

- ^ Wright WE, Tesmer VM, Huffman KE, Levene SD, Shay JW (November 1997). «Normal human chromosomes have long G-rich telomeric overhangs at one end». Genes & Development. 11 (21): 2801–09. doi:10.1101/gad.11.21.2801. PMC 316649. PMID 9353250.

- ^ a b Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S (2006). «Quadruplex DNA: sequence, topology and structure». Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (19): 5402–15. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl655. PMC 1636468. PMID 17012276.

- ^ Parkinson GN, Lee MP, Neidle S (June 2002). «Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA». Nature. 417 (6891): 876–80. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..876P. doi:10.1038/nature755. PMID 12050675. S2CID 4422211.

- ^ Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T (May 1999). «Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop». Cell. 97 (4): 503–14. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.2649. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80760-6. PMID 10338214. S2CID 721901.

- ^ Seeman NC (November 2005). «DNA enables nanoscale control of the structure of matter». Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 38 (4): 363–71. doi:10.1017/S0033583505004087. PMC 3478329. PMID 16515737.

- ^ Warren M (21 February 2019). «Four new DNA letters double life’s alphabet». Nature. 566 (7745): 436. Bibcode:2019Natur.566..436W. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00650-8. PMID 30809059.

- ^ Hoshika S, Leal NA, Kim MJ, Kim MS, Karalkar NB, Kim HJ, et al. (22 February 2019). «Hachimoji DNA and RNA: A genetic system with eight building blocks (paywall)». Science. 363 (6429): 884–887. Bibcode:2019Sci…363..884H. doi:10.1126/science.aat0971. PMC 6413494. PMID 30792304.

- ^ Burghardt B, Hartmann AK (February 2007). «RNA secondary structure design». Physical Review E. 75 (2): 021920. arXiv:physics/0609135. Bibcode:2007PhRvE..75b1920B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.75.021920. PMID 17358380. S2CID 17574854.

- ^ Reusch, William. «Nucleic Acids». Michigan State University. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ «How To Extract DNA From Anything Living». University of Utah. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Hu Q, Rosenfeld MG (2012). «Epigenetic regulation of human embryonic stem cells». Frontiers in Genetics. 3: 238. doi:10.3389/fgene.2012.00238. PMC 3488762. PMID 23133442.

- ^ Klose RJ, Bird AP (February 2006). «Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators». Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 31 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. PMID 16403636.

- ^ Bird A (January 2002). «DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory». Genes & Development. 16 (1): 6–21. doi:10.1101/gad.947102. PMID 11782440.

- ^ Walsh CP, Xu GL (2006). «Cytosine methylation and DNA repair». Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 301: 283–315. doi:10.1007/3-540-31390-7_11. ISBN 3-540-29114-8. PMID 16570853.

- ^ Kriaucionis S, Heintz N (May 2009). «The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain». Science. 324 (5929): 929–30. Bibcode:2009Sci…324..929K. doi:10.1126/science.1169786. PMC 3263819. PMID 19372393.

- ^ Ratel D, Ravanat JL, Berger F, Wion D (March 2006). «N6-methyladenine: the other methylated base of DNA». BioEssays. 28 (3): 309–15. doi:10.1002/bies.20342. PMC 2754416. PMID 16479578.