Lloegr

What is the meaning of Bryn Mawr?

high hill

What does the Welsh word BOPA mean?

aunty

What do Welsh people call their mother?

BBC Vocab: A Window into Welsh….

| Y Teulu | The family |

|---|---|

| Mam | Mother |

| Tad | Father |

| Rhieni | Parents |

| Brawd | Brother |

What is Welsh for dad?

Family words in Welsh (Cymraeg)

| Welsh (Cymraeg) | |

|---|---|

| family | teulu |

| parents | rhieni |

| father | tad |

| mother | mam |

How do you use Welsh?

There is no indefinite article (a and an in English) in Welsh. The definite articles (corresponding to the in English) are y, yr and ‘r. The rules for their use are: y is used before consonants.

What does ping mean in Welsh?

What’s the Welsh for microwave? It’s not really popty-ping, if that’s what you’re getting at. [Popty means ‘oven’, so it’s an oven that goes ping. It’s a joke.] The proper name is microdon – the don bit means ‘wave’.

How did hugs originate?

The first is that the verb “hug” (first used in the 1560s) could be related to the Old Norse word hugga, which meant to comfort. The second theory is that the word is related to the German word hegen, which means to foster or cherish, and originally meant to enclose with a hedge.

How do you pronounce Euouae?

Euouae (/juːˈuːiː/) or Evovae is an abbreviation used in Latin psalters and other liturgical books to show the distribution of syllables in the differentia or variable melodic endings of the standard Psalm tones of Gregorian chant.

What do you mean by Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis?

What is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis? noun | A lung disease caused by the inhalation of very fine silicate or quartz dust, causing inflammation in the lungs.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Saesneg» redirects here. For the language called «Welsh», see Welsh language.

| Welsh English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Wales |

|

Native speakers |

(undated figure of 2.5 million[citation needed]) |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Old English

|

|

Writing system |

Latin (English alphabet) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

An example of a male with a South Wales accent (Rob Brydon).

Welsh English (Welsh: Saesneg Gymreig) comprises the dialects of English spoken by Welsh people. The dialects are significantly influenced by Welsh grammar and often include words derived from Welsh. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, a variety of accents are found across Wales, including those of North Wales, the Cardiff dialect, the South Wales Valleys and West Wales.

Accents and dialects in the west of Wales have been more heavily influenced by the Welsh language while dialects in the east have been influenced more by dialects in England.[1] In the east and south east, it has been influenced by West Country and West Midland dialects[2] while in north east Wales and parts of the North Wales coast, it has been influenced by Merseyside English.

A colloquial portmanteau word for Welsh English is Wenglish. It has been in use since 1985.[3]

Pronunciation[edit]

Vowels[edit]

Short monophthongs[edit]

- The vowel of cat /æ/ is pronounced either as an open front unrounded vowel [a][4][5] or a more central near-open front unrounded vowel [æ̈].[6] In Cardiff, bag is pronounced with a long vowel [aː].[7] In Mid-Wales, a pronunciation resembling its New Zealand and South African analogue is sometimes heard, i.e. trap is pronounced /trɛp/[8]

- The vowel of end /ɛ/ is a more open vowel and thus closer to cardinal vowel [ɛ] than RP[6]

- In Cardiff, the vowel of «kit» /ɪ/ sounds slightly closer to the schwa sound of above, an advanced close-mid central unrounded vowel [ɘ̟][6]

- The vowel of «bus» /ʌ/ is usually pronounced [ɜ~ə][9][10] and is encountered as a hypercorrection in northern areas for foot.[8] It is sometimes manifested in border areas of north and mid Wales as an open front unrounded vowel /a/. It also manifests as a near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ without the foot–strut split in northeast Wales, under influence of Cheshire and Merseyside accents,[8] and to a lesser extent in south Pembrokeshire.[11]

- The schwa tends to be supplanted by an /ɛ/ in final closed syllables, e.g. brightest /ˈbrəitɛst/. The uncertainty over which vowel to use often leads to ‘hypercorrections’ involving the schwa, e.g. programme is often pronounced /ˈproːɡrəm/[7]

Long monophthongs[edit]

Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from Coupland & Thomas (1990), pp. 135–136.

Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from Coupland & Thomas (1990), pp. 93–95. Depending on the speaker, the long /ɛː/ may be of the same height as the short /ɛ/.[12]

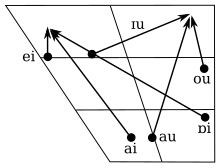

Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from Coupland & Thomas (1990), pp. 135–136

Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from Coupland & Thomas (1990), p. 97

- The trap-bath split is variable in Welsh English, especially among social status. In some varieties such as Cardiff English, words like ask, bath, laugh, master and rather are usually pronounced with PALM while words like answer, castle, dance and nasty are normally pronounced with TRAP. On the other hand, the split may be completely absent in other varieties like Abercraf English.[13]

- The vowel of car is often pronounced as an open central unrounded vowel [ɑ̈][14] and more often as a long open front unrounded vowel /aː/[8]

- In broader varieties, particularly in Cardiff, the vowel of bird is similar to South African and New Zealand, i.e. a mid front rounded vowel [ø̞ː][15]

- Most other long monophthongs are similar to that of Received Pronunciation, but words with the RP /əʊ/ are sometimes pronounced as [oː] and the RP /eɪ/ as [eː]. An example that illustrates this tendency is the Abercrave pronunciation of play-place [ˈpleɪˌpleːs][16]

- In northern varieties, /əʊ/ as in coat and /ɔː/ as in caught/court may be merged into /ɔː/ (phonetically [oː]).[7]

Diphthongs[edit]

- Fronting diphthongs tend to resemble Received Pronunciation, apart from the vowel of bite that has a more centralised onset [æ̈ɪ][16]

- Backing diphthongs are more varied:[16]

- The vowel of low in RP, other than being rendered as a monophthong, like described above, is often pronounced as [oʊ̝]

- The word town is pronounced with a near-open central onset [ɐʊ̝]

- Welsh English is one of few dialects where the Late Middle English diphthong /iu̯/ never became /juː/, remaining as a falling diphthong [ɪʊ̯]. Thus you /juː/, yew /jɪʊ̯/, and ewe /ɪʊ̯/ are not homophones in Welsh English. As such yod-dropping never occurs: distinctions are made between choose /t͡ʃuːz/ and chews /t͡ʃɪʊ̯s/, through /θruː/ and threw /θrɪʊ̯/, which most other English varieties do not have.

Consonants[edit]

- Most Welsh accents pronounce /r/ as an alveolar tap [ɾ] (a ‘tapped r’), similar to Scottish English and some Northern English and South African accents, in place of an approximant [ɹ] like in most accents in England[17] while an alveolar trill [r] may also be used under the influence of Welsh[18]

- Welsh English is mostly non-rhotic, however variable rhoticity can be found in accents influenced by Welsh, especially northern varieties. Additionally, while Port Talbot English is mostly non-rhotic like other varieties of Welsh English, some speakers may supplant the front vowel of bird with /ɚ/, like in many varieties of North American English.[19]

- H-dropping is common in many Welsh accents, especially southern varieties like Cardiff English,[20] but is absent in northern and western varieties influenced by Welsh.[21]

- Some gemination between vowels is often encountered, e.g. money is pronounced [ˈmɜn.niː][22]

- As Welsh lacks the letter Z and the voiced alveolar fricative /z/, some first-language Welsh speakers replace it with the voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ for words like cheese and thousand, while pens (/pɛnz/) and pence merge into /pɛns/, especially in north-west, west and south-west Wales.[22][23]

- In northern varieties influenced by Welsh, chin (/tʃɪn/) and gin may also merge into /dʒɪn/[22]

- In the north-east, under influence of such accents as Scouse, ng-coalescence does not take place, so sing is pronounced /sɪŋɡ/[24]

- Also in northern accents, /l/ is frequently strongly velarised [ɫː]. In much of the south-east, clear and dark L alternate much like they do in RP[19]

- The consonants are generally the same as RP but Welsh consonants like /ɬ/ and /x/ (phonetically [χ]) are encountered in loan words such as Llangefni and Harlech[22]

Distinctive vocabulary and grammar[edit]

Aside from lexical borrowings from Welsh like bach (little, wee), eisteddfod, nain and taid (grandmother and grandfather respectively), there exist distinctive grammatical conventions in vernacular Welsh English. Examples of this include the use by some speakers of the tag question isn’t it? regardless of the form of the preceding statement and the placement of the subject and the verb after the predicate for emphasis, e.g. Fed up, I am or Running on Friday, he is.[22]

In South Wales the word where may often be expanded to where to, as in the question, «Where to is your Mam?«. The word butty (Welsh: byti, probably related to «buddy»[citation needed]) is used to mean «friend» or «mate».[25]

There is no standard variety of English that is specific to Wales, but such features are readily recognised by Anglophones from the rest of the UK as being from Wales, including the (actually rarely used) phrase look you which is a translation of a Welsh language tag.[22]

The word tidy has been described as «one of the most over-worked Wenglish words» and can have a range of meanings including — fine or splendid, long, decent, and plenty or large amount. A tidy swill is a wash involving at least face and hands.[26]

Code-switching[edit]

As Wales has become increasingly more anglicised, code-switching has become increasingly more common.[27][28]

Examples[edit]

Welsh code-switchers fall typically into one of three categories: the first category is people whose first language is Welsh and are not the most comfortable with English, the second is the inverse, English as a first language and a lack of confidence with Welsh, and the third consists of people whose first language could be either and display competence in both languages.[29]

Welsh and English share congruence, meaning that there is enough overlap in their structure to make them compatible for code-switching. In studies of Welsh English code-switching, Welsh frequently acts as the matrix language with English words or phrases mixed in. A typical example of this usage would look like dw i’n love-io soaps, which translates to «I love soaps».[28]

In a study conducted by Margaret Deuchar in 2005 on Welsh-English code-switching, 90 per cent of tested sentences were found to be congruent with the Matrix Language Format, or MLF, classifying Welsh English as a classic case of code-switching.[28] This case is identifiable as the matrix language was identifiable, the majority of clauses in a sentence that uses code-switching must be identifiable and distinct, and the sentence takes the structure of the matrix language in respect to things such as subject verb order and modifiers.[27]

History of the English language in Wales[edit]

The presence of English in Wales intensified on the passing of the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542, the statutes having promoted the dominance of English in Wales; this, coupled with the closure of the monasteries, which closed down many centres of Welsh education, led to decline in the use of the Welsh language.

The decline of Welsh and the ascendancy of English was intensified further during the Industrial Revolution, when many Welsh speakers moved to England to find work and the recently developed mining and smelting industries came to be manned by Anglophones. David Crystal, who grew up in Holyhead, claims that the continuing dominance of English in Wales is little different from its spread elsewhere in the world.[30] The decline in the use of the Welsh language is also associated with the preference in the communities for English to be used in schools and to discourage everyday use of the Welsh language in them, including by the use of the Welsh Not in some schools in the 18th and 19th centuries.[31]

Influence outside Wales[edit]

While other British English accents from England have affected the accents of English in Wales, especially in the east of the country, influence has moved in both directions.[1] Accents in north-east Wales and parts of the North Wales coastline have been influenced by accents in North West England, accents in the mid-east have been influenced by accents in the West Midlands while accents in south-east Wales have been influenced by West Country English.[2] In particular, Scouse and Brummie (colloquial) accents have both had extensive Anglo-Welsh input through migration, although in the former case, the influence of Anglo-Irish is better known.

Literature[edit]

«Anglo-Welsh literature» and «Welsh writing in English» are terms used to describe works written in the English language by Welsh writers. It has been recognised as a distinctive entity only since the 20th century.[32] The need for a separate identity for this kind of writing arose because of the parallel development of modern Welsh-language literature; as such it is perhaps the youngest branch of English-language literature in the British Isles.

While Raymond Garlick discovered sixty-nine Welsh men and women who wrote in English prior to the twentieth century,[32] Dafydd Johnston believes it is «debatable whether such writers belong to a recognisable Anglo-Welsh literature, as opposed to English literature in general».[33] Well into the 19th century English was spoken by relatively few in Wales, and prior to the early 20th century there are only three major Welsh-born writers who wrote in the English language: George Herbert (1593–1633) from Montgomeryshire, Henry Vaughan (1622–1695) from Brecknockshire, and John Dyer (1699–1757) from Carmarthenshire.

Welsh writing in English might be said to begin with the 15th-century bard Ieuan ap Hywel Swrdwal (?1430 — ?1480), whose Hymn to the Virgin was written at Oxford in England in about 1470 and uses a Welsh poetic form, the awdl, and Welsh orthography; for example:

- O mighti ladi, owr leding — tw haf

-

- At hefn owr abeiding:

- Yntw ddy ffast eferlasting

- I set a braents ws tw bring.

-

A rival claim for the first Welsh writer to use English creatively is made for the diplomat, soldier and poet John Clanvowe (1341–1391).[citation needed]

The influence of Welsh English can be seen in the 1915 short story collection My People by Caradoc Evans, which uses it in dialogue (but not narrative); Under Milk Wood (1954) by Dylan Thomas, originally a radio play; and Niall Griffiths whose gritty realist pieces are mostly written in Welsh English.

See also[edit]

- Cardiff English

- Abercraf English

- Gower dialect

- Port Talbot English

- Welsh literature in English

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Gallo (Brittany)

- Scots language

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages

- Anglo-Cornish

- Anglo-Manx

- Bungi creole

- Hiberno-English

- Highland English (and Scottish English)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Rhodri Clark (27 March 2007). «Revealed: the wide range of Welsh accents». Wales Online. Wales Online. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ a b «Secret behind our Welsh accents discovered». Wales Online. Wales Online. 7 June 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Lambert, James (2018). «A multitude of «lishes»«. English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English. 39: 1–33. doi:10.1075/eww.00001.lam.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 380, 384–385.

- ^ Connolly (1990), pp. 122, 125.

- ^ a b c Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Wells (1982), pp. 384, 387, 390

- ^ a b c d Schneider, Edgar Werner; Kortmann, Bernd (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. — Google Books. ISBN 9783110175325. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 380–381.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (27 April 2019). «Wales’s very own little England». The New European. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Coupland & Thomas (1990), p. 95.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 387.

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Peter Garrett; Nikolas Coupland; Angie Williams, eds. (15 July 2003). Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. University of Wales Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781783162086. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change — Google Books. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland (1988), p. 29.

- ^ Approaches to the Study of Sound Structure and Speech: Interdisciplinary Work in Honour of Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk. Magdalena Wrembel, Agnieszka Kiełkiewicz-Janowiak and Piotr Gąsiorowski. 21 October 2019. pp. 1–398. ISBN 9780429321757.

- ^ a b c d e f Crystal (2003), p. 335.

- ^ The British Isles. Bernd Kortmann and Clive Upton. 10 December 2008. ISBN 9783110208399. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 390.

- ^ «Why butty rarely leaves Wales». Wales Online. 2 October 2006 [updated: 30 Mar 2013]. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Edwards, John (1985). Talk Tidy. Bridgend, Wales, UK: D Brown & Sons Ltd. p. 39. ISBN 0905928458.

- ^ a b Deuchar, Margaret (1 November 2006). «Welsh-English code-switching and the Matrix Language Frame model». Lingua. 116 (11): 1986–2011. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2004.10.001. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b c Deuchar, Margaret (December 2005). «Congruence and Welsh–English code-switching». Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 8 (3): 255–269. doi:10.1017/S1366728905002294. ISSN 1469-1841. S2CID 144548890.

- ^ Deuchar, Margaret; Davies, Peredur (2009). «Code switching and the future of the Welsh language». International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2009 (195). doi:10.1515/ijsl.2009.004. S2CID 145440479.

- ^ Crystal (2003), p. 334.

- ^ «Welsh and 19th century education». BBC. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b Garlick (1970).

- ^ Johnston (1994), p. 91.

Bibliography[edit]

- Coupland, Nikolas (1988), Dialect in Use: Sociolinguistic Variation in Cardiff English, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-70830-958-5

- Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan R., eds. (1990), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, Multilingual Matters Ltd., ISBN 978-1-85359-032-0

- Crystal, David (4 August 2003), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521530330

- Johnston, Dafydd (1994), A Pocket Guide to the Literature of Wales, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, ISBN 978-0708312650

- Garlick, Raymond (1970), «Welsh Arts Council», An introduction to Anglo-Welsh literature, University of Wales Press, ISSN 0141-5050

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Volume 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–393, ISBN 0-52128540-2

Further reading[edit]

- Penhallurick, Robert (2004), «Welsh English: phonology», in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, Vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 98–112, ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5

- Podhovnik, Edith (2010), «Age and Accent — Changes in a Southern Welsh English Accent» (PDF), Research in Language, 8 (2010): 1–18, doi:10.2478/v10015-010-0006-5, hdl:11089/9569, ISSN 2083-4616, S2CID 145409227, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015, retrieved 25 August 2015

- Parry, David, A Grammar and Glossary of the Conservative Anglo-Welsh Dialects of Rural Wales, The National Centre for English Cultural Tradition: introduction and phonology available at the Internet Archive.

External links[edit]

- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects from across the UK on the British Library’s ‘Sounds Familiar’ website

- Talk Tidy : John Edwards, Author of books and CDs on the subject «Wenglish».

- Some thoughts and notes on the English of south Wales : D Parry-Jones, National Library of Wales journal 1974 Winter, volume XVIII/4

- Samples of Welsh Dialect(s)/Accent(s) Archived 26 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Welsh vowels

- David Jandrell: Introducing The Welsh Valleys Phrasebook

-

#1

Welsh names for the English language and an English person (Saesneg, Sais) clearly derive from the name of the Saxon tribe (same in Scottish Gaelic).

However, the country is called Lloegr. Any ideas where it comes from?

-

#3

Thank you Stoggler. So no one really knows, as it turns out.

-

#4

This Logres and Logris (England) reminds me of the Greek toponym Lokris, of unknown etymology as well. Some non academic sources say that Lokris is related to the word Lokroi or Likroi (plural) which means the stag’s antlers. Metaphorically also meaned the archers.

-

#5

According to Alister Moffat in ‘The British; a genetic journey’ the word Lloegr means ‘lost lands’ which would make sense in the context in which the distinction from Cymru (‘countrymen’) needed to be made at the time of the Saxon invasion.

-

#6

According to Alister Moffat in ‘The British; a genetic journey’ the word Lloegr means ‘lost lands’ which would make sense in the context in which the distinction from Cymru (‘countrymen’) needed to be made at the time of the Saxon invasion.

The meaning «lost lands» would indeed make sense historically, but is there any linguistic evidence to prove that? «Lloegr» doesn’t seem to be related to the Welsh verb «colli» (to lose) although there may be synonyms I don’t know about since my Welsh is very basic.

-

#7

Since those parts they are calling Lloegr used to be Celtic and Welsh is Celt, could it be they name it that cause it’s an area they inhabited. At the moment they inhabitted, they gave it a name and it stayed. Loga in Serbian today means den/lair..logor is a camp. I think these are all from what they marked as a pie *legh-lay down. Generally sometimes when using an expression «loga» we’d say our «loga» with a meaning of our home. Where we lay down/rest actually live/settle. You can try to check their dictionaries.

Good luck, keep researching

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

Best Answer

Copy

English , adj , Seisnig ()English(language), n , Saesneg ()English (people), coll , Saeson ()

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the Welsh for ‘English’?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

This is a list of English language words of Welsh language origin. As with the Goidelic languages, the Brythonic tongues are close enough for possible derivations from Cumbric, Cornish or Breton in some cases.

Beyond the acquisition of common nouns, there are numerous English toponyms, surnames, personal names or nicknames derived from Welsh (see Celtic toponymy, Celtic onomastics).[1]

ListEdit

As main word choice for meaningEdit

- bara brith

- speckled bread. Traditional Welsh bread flavoured with tea, dried fruits and mixed spices.

- bard

- from Old Celtic bardos, either through Welsh bardd (where the bard was highly respected) or Scottish bardis (where it was a term of contempt); Cornish bardh

- cawl

- a traditional Welsh soup/stew; Cornish kowl

- coracle

- from corwgl. This Welsh term was derived from the Latin corium meaning «leather or hide», the material from which coracles are made.[2]

- corgi

- from cor, «dwarf» + gi (soft mutation of ci), «dog».

- cwm

- (very specific geographic sense today) or coomb (dated). Cornish; komm; passed into Old English where sometimes written ‘cumb’

- flannel

- the Oxford English Dictionary says the etymology is «uncertain», but Welsh gwlanen = «flannel wool» is likely. An alternative source is Old French flaine, «blanket». The word has been adopted in most European languages. An earlier English form was flannen, which supports the Welsh etymology. Shakspeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor contains the term «the Welsh flannel».[3][4]

- flummery

- from llymru[3][4]

- pikelet

- a type of small, thick pancake. Derived from the Welsh bara pyglyd, meaning «pitchy [i.e. dark or sticky] bread», later shortened simply to pyglyd;[5][6] The early 17th century lexicographer, Randle Cotgrave, spoke of «our Welsh barrapycleds».[7][8] The word spread initially to the West Midlands of England,[9] where it was anglicised to picklets and then to pikelets.[8] The first recognisable crumpet-type recipe was for picklets, published in 1769 by Elizabeth Raffald in The Experienced English Housekeeper.[10]

- wrasse

- a kind of sea fish (derived via Cornish wrach, Welsh gwrach (meaning hag or witch)).[11]

Esoteric or specialistEdit

- cist

- (archaeological) a stone-lined coffin

- cromlech

- from crom llech literally «crooked flat stone»

- crwth

- «a bowed lyre»

- kistvaen

- from cist (chest) and maen (stone).

- lech /lɛk/

- capstone of a cromlech, see above[12]

- tref

- meaning “hamlet, home, town.”;[13] Cornish tre.

Words with indirect or possible linksEdit

Similar cognates across Goidelic (gaelic), Latin, Old French and the other Brittonic families makes isolating a precise origin hard. This applies to cross from Latin crux, Old Irish cros overtaking Old English rood ; appearing in Welsh and Cornish as Croes, Krows. It complicates Old Welsh attributions for, in popular and technical topography, Tor (OW tŵr) and crag (Old Welsh carreg or craig) with competing Celtic derivations, direct and indirect, for the Old English antecedents.

- adder

- The Proto-Indo-European root netr- led to Latin natrix, Welsh neidr, Cornish nader, Breton naer, West Germanic nædro, Old Norse naðra, Middle Dutch nadre, any of which may have led to the English word.

- bow

- May be from Old English bugan «to bend, to bow down, to bend the body in condescension,» also «to turn back», or more simply from the Welsh word bwa. A reason for the word Bow originating from Welsh, is due to Welsh Bowmen playing a major role in the Hundred Years War, such as the Battle of Crécy, Battle of Agincourt and the Battle of Patay, and the bows were often created in Wales.[14][15]

- coombe

- meaning «valley», is usually linked with the Welsh cwm, also meaning «valley», Cornish and Breton komm. However, the OED traces both words back to an earlier Celtic word, *kumbos. It suggests a direct Old English derivation for «coombe».

- (Coumba, or coumbo, is the common western-alpine vernacular word for «glen», and considered genuine gaulish (celtic-ligurian branch). Found in many toponyms of the western Alps like Coumboscuro (Grana valley), Bellecombe and Coumbafréide (Aoste), Combette (Suse), Coumbal dou Moulin (Valdensian valleys). Although seldom used, the word «combe» is included into major standard-french dictionaries. This could justify the celtic origin thesis).[citation needed]

- crockery

- It has been suggested that crockery might derive from the Welsh crochan, as well as the Manx crocan and Gaelic crogan, meaning «pot». The OED states that this view is «undetermined». It suggests that the word derives from Old English croc, via the Icelandic krukka, meaning «an earthenware pot or pitcher».

- crumpet

- Welsh crempog, cramwyth, Cornish krampoeth or Breton Krampouezh; ‘little hearth cakes’

- druid

- From the Old Celtic derwijes/derwos («true knowledge» or literally «they who know the oak») from which the modern Welsh word derwydd evolved, but travelled to English through Latin (druidae) and French (druide)

- gull

- from either Welsh or Cornish;[16] Welsh gwylan, Cornish guilan, Breton goelann; all from O.Celt. *voilenno— «gull» (OE mæw)

- iron

- or at least the modern form of the word «iron» (c/f Old English ísern, proto-Germanic *isarno, itself borrowed from proto-Celtic), appears to have been influenced by pre-existing Celtic forms in the British Isles: Old Welsh haearn, Cornish hoern, Breton houarn, Old Gaelic íarn (Irish iaran, iarun, Scottish iarunn)[17]

- lawn

- from Welsh Llan Cornish Lan (cf. Launceston, Breton Lann); Heath; enclosed area of land, grass about a Christian site of worship from Cornish Lan (e.g. Lanteglos, occasionally Laun as in Launceston) or Welsh Llan (e.g. Llandewi)[18]

- penguin

- possibly from pen gwyn, «white head». «The fact that the penguin has a black head is no serious objection.»[3][4] It may also be derived from the Breton language, or the Cornish Language, which are all closely related. However, dictionaries suggest the derivation is from Welsh pen «head» and gwyn «white», including the Oxford English Dictionary,[19] the American Heritage Dictionary,[20] the Century Dictionary[21] and Merriam-Webster,[22] on the basis that the name was originally applied to the great auk, which had white spots in front of its eyes (although its head was black). Pen gwyn is identical in Cornish and in Breton. An alternative etymology links the word to Latin pinguis, which means «fat». In Dutch, the alternative word for penguin is «fat-goose» (vetgans see: Dutch wiki or dictionaries under Pinguïn), and would indicate this bird received its name from its appearance.

- Mither

- An English word possibly from the Welsh word «moedro» meaning to bother or pester someone. Possible links to the Yorkshire variant «moither»

In Welsh EnglishEdit

These are the words widely used by Welsh English speakers, with little or no Welsh, and are used with original spelling (largely used in Wales but less often by others when referring to Wales):

- afon

- river

- awdl

- ode

- bach

- literally «small», a term of affection

- cromlech

- defined at esoteric/specialist terms section above

- cwm

- a valley

- crwth

- originally meaning «swelling» or «pregnant»

- cwrw

- Welsh ale or beer

- cwtch

- hug, cuddle, small cupboard, dog’s kennel/bed[23]

- cynghanedd

- eisteddfod

- broad cultural festival, «session/sitting» from eistedd «to sit» (from sedd «seat,» cognate with L. sedere; see sedentary) + bod «to be» (cognate with O.E. beon; see be).[24]

- Urdd Eisteddfod (in Welsh «Eisteddfod Yr Urdd»), the youth Eisteddfod

- englyn

- gorsedd

- hiraeth

- homesickness tinged with grief or sadness over the lost or departed. It is a mix of longing, yearning, nostalgia, wistfulness, or an earnest desire.

- hwyl

- iechyd da

- cheers, or literally «good health»

- mochyn

- pig

- nant

- stream

- sglod, sglods

- latter contrasts to Welsh plural which is sglodion. Chips (England); fries (universally); french-fried potatoes such as from takeaways (used in Flintshire)

- twp/dwp

- idiotic, daft

- ych â fi

- an expression of disgust

See alsoEdit

- Lists of English words of Celtic origin

- List of English words of Brittonic origin

- Brittonicisms in English

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Max Förster Keltisches Wortgut im Englischen, 1921, cited by J.R.R. Tolkien, English and Welsh, 1955. «many ‘English’ surnames, ranging from the rarest to the most familiar, are linguistically derived from Welsh, from place-names, patronymics, personal names, or nick-names; or are in part so derived, even when that origin is no longer obvious. Names such as Gough, Dewey, Yarnal, Merrick, Onions, or Vowles, to mention only a few.»

- ^ «corium | Etymology, origin and meaning of corium by etymonline». www.etymonline.com.

- ^ a b c Weekley, Ernest (1921), An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English.

- ^ a b c Skeat, Walter W (1888), An Etymological Dictionary the English Language, Oxford Clarendon Press.

- ^ Edwards, W. P. The Science of Bakery Products, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007, p. 198

- ^ Luard, E. European Peasant Cookery, Grub Street, 2004, p. 449

- ^ The folk-speech of south Cheshire, English Dialect Society, 1887, p. 293

- ^ a b Notes & Queries, 3rd. ser. VII (1865), 170

- ^ Wilson, C. A. Food & drink in Britain, Barnes and Noble, 1974, p. 266

- ^ Davidson, A. The Penguin Companion to Food, 2002, p. 277

- ^ «Wrasse», Etymology online.

- ^ «Lech», Etymology online.

- ^ «Tref», Etymology online.

- ^ «The Welsh Longbow». Sarah Woodbury. 9 July 2014.

- ^ «The Welsh Longbow — Warbow Wales». Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ «Gull», Etymology online.

- ^ «Iron», OED.

- ^ «Lawn», Etymology online.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Accessed 2007-03-21

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary at wordnik.com Archived 2014-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-01-25

- ^ Century Dictionary at wordnik.com Archived 2014-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-01-25

- ^ Merriam-Webster Accessed 2010-01-25

- ^ «What is a ‘cwtch’?». University of South Wales. 26 February 2018.

- ^ «eisteddfod | Search Online Etymology Dictionary». www.etymonline.com.

SourcesEdit

- Oxford English Dictionary