Table of Contents

- What is the root of the word dictionary?

- Who is poorest of poor class 9?

- What is always poor?

- What are the six types of poverty?

- What are the characteristics of rural poor?

- What are the key features of the poorest households?

- What did Gandhi say about poverty class 9?

- What is consumption method Class 9?

- What are the two methods of estimating the poverty line class 9?

- Which methods are used to estimate the poverty line?

- Which country has the largest concentration of poor?

- Is Nigeria poorer than India?

- Is India poorer than Africa?

- Who is richest country in the world?

The Latin root word dict and its variant dic both mean ‘say. ‘ Some common English vocabulary words that come from this word root include dictionary, contradict, and dedicate.

Who is poorest of poor class 9?

Women, infants and elderly are considered as the poorest of the poor.

What is always poor?

Transient poor are those who are: Always poor. Usually poor. Never poor. Churning poor moving in and out of poverty and occasionally poor.

What are the six types of poverty?

However you define it, poverty is complex; it does not mean the same thing for all people. For the purposes of this book, we can identify six types of poverty: situational, generational, absolute, relative, urban, and rural.

What are the characteristics of rural poor?

In general, poor people living in rural areas share several characteristics including: low levels of educational attainment; a relatively large number of children; relatively low access to material resources, social and physical infrastructure; and higher susceptibility to community-wide exogenous shocks (e.g. weather …

What are the key features of the poorest households?

Starvation and hunger are the key features of the poorest households. The poor lack basic literacy and skills and hence have very limited economic opportunities. Poor people also face unstable employment.

What did Gandhi say about poverty class 9?

(6) What did Mahatma Gandhi say about about poverty? A: Mahatma Gandhi always said that India would be truly independent only when the poorest of its people become free of human suffering.

What is consumption method Class 9?

Consumption method: A minimum nutritional food requirement is measured and energy obtained from this food is measured in calories. If the calories requirement is not fulfilled then the person is considered to be below the poverty line.

What are the two methods of estimating the poverty line class 9?

The two methods to estimate poverty lines are: i) Consumption method- determining the poverty line in India based on the desired calorie requirement. E.g. the average calorie requirement in India is 2400 calories per person per day in rural areas and 2100 calories per person per day in urban areas.

Which methods are used to estimate the poverty line?

A common method used to estimate poverty in India is based on the income or consumption levels and if the income or consumption falls below a given minimum level, then the household is said to be Below the Poverty Line (BPL).

Which country has the largest concentration of poor?

Nigeria has become the poverty capital of the world A new report by The World Poverty Clock shows Nigeria has overtaken India as the country with the most extreme poor people in the world.

Is Nigeria poorer than India?

India has a GDP per capita of $7,200 as of 2017, while in Nigeria, the GDP per capita is $5,900 as of 2017.

Is India poorer than Africa?

1/3rd world’s poor is in India. It also has a higher proportion of its population living on less than $ 2 per day than even sub-Saharan Africa. 828 million people or 75.6% of the population is living below $2 a day. 33% of the global poor are Indians which equals to 14 billion people.

Who is richest country in the world?

Luxembourg

The Latin root word dict and its variant dic both mean ‘say. ‘ Some common English vocabulary words that come from this word root include dictionary, contradict, and dedicate. Perhaps the easiest way in which to remember this root is the word prediction, for a prediction is ‘said’ before something actually happens.

Also asked, what is the root word for friends?

AMICUS: Latin root meaning “friend” amicable: friendly. amity: friendship between nations. amiable: friendly.

What are the root words in English?

The most frequently used English root words are listed below:

- Root Word: pan. Meaning: all.

- Root Word: thei. Meaning: God.

- Root Word: logy. Meaning of the English root word: study of something.

- Root Word: cert. Meaning: sure.

- Root Word: carnio. Meaning: skull.

- Root Word: max. Meaning: largest.

- Root Word: min.

- Root Word: medi.

What are the 3 types of friendship?

According to Aristotle, there are three types of friendships: those based on utility, those based on pleasure or delight, and those grounded in virtue. In the first type, friendship based on utility, people associate for their mutual usefulness. These relationships are the most common.

What is the root or base word for illegal?

The root word for the word illegal is legal. Prefixes are words, letters or some numbers that placed before the word itself. In this case, il- is the prefix of illegal, which means not acquired or done in a moral or official manner contrary to legal, which is the opposed definition of illegal.

Write Your Answer

Dictionary definition entries

A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically (or by radical and stroke for ideographic languages), which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies, pronunciations, translation, etc.[1][2][3] It is a lexicographical reference that shows inter-relationships among the data.[4]

A broad distinction is made between general and specialized dictionaries. Specialized dictionaries include words in specialist fields, rather than a complete range of words in the language. Lexical items that describe concepts in specific fields are usually called terms instead of words, although there is no consensus whether lexicology and terminology are two different fields of study. In theory, general dictionaries are supposed[citation needed] to be semasiological, mapping word to definition, while specialized dictionaries are supposed to be onomasiological, first identifying concepts and then establishing the terms used to designate them. In practice, the two approaches are used for both types.[5] There are other types of dictionaries that do not fit neatly into the above distinction, for instance bilingual (translation) dictionaries, dictionaries of synonyms (thesauri), and rhyming dictionaries. The word dictionary (unqualified) is usually understood to refer to a general purpose monolingual dictionary.[6]

There is also a contrast between prescriptive or descriptive dictionaries; the former reflect what is seen as correct use of the language while the latter reflect recorded actual use. Stylistic indications (e.g. «informal» or «vulgar») in many modern dictionaries are also considered by some to be less than objectively descriptive.[7]

The first recorded dictionaries date back to Sumerian times around 2300 BCE, in the form of bilingual dictionaries, and the oldest surviving monolingual dictionaries are Chinese dictionaries c. 3rd century BCE. The first purely English alphabetical dictionary was A Table Alphabeticall, written in 1604, and monolingual dictionaries in other languages also began appearing in Europe at around this time. The systematic study of dictionaries as objects of scientific interest arose as a 20th-century enterprise, called lexicography, and largely initiated by Ladislav Zgusta.[6] The birth of the new discipline was not without controversy, with the practical dictionary-makers being sometimes accused by others of having an «astonishing» lack of method and critical-self reflection.[8]

History

Catalan-Latin dictionary from the year 1696 with more than 1000 pages. Gazophylacium Dictionary.

The oldest known dictionaries were cuneiform tablets with bilingual Sumerian–Akkadian wordlists, discovered in Ebla (modern Syria) and dated to roughly 2300 BCE, the time of the Akkadian Empire.[9][10][11] The early 2nd millennium BCE Urra=hubullu glossary is the canonical Babylonian version of such bilingual Sumerian wordlists. A Chinese dictionary, the c. 3rd century BCE Erya, is the earliest surviving monolingual dictionary; and some sources cite the Shizhoupian (probably compiled sometime between 700 BCE to 200 BCE, possibly earlier) as a «dictionary», although modern scholarship considers it a calligraphic compendium of Chinese characters from Zhou dynasty bronzes.[citation needed] Philitas of Cos (fl. 4th century BCE) wrote a pioneering vocabulary Disorderly Words (Ἄτακτοι γλῶσσαι, Átaktoi glôssai) which explained the meanings of rare Homeric and other literary words, words from local dialects, and technical terms.[12] Apollonius the Sophist (fl. 1st century CE) wrote the oldest surviving Homeric lexicon.[10] The first Sanskrit dictionary, the Amarakośa, was written by Amarasimha c. 4th century CE. Written in verse, it listed around 10,000 words. According to the Nihon Shoki, the first Japanese dictionary was the long-lost 682 CE Niina glossary of Chinese characters. The oldest existing Japanese dictionary, the c. 835 CE Tenrei Banshō Meigi, was also a glossary of written Chinese. In Frahang-i Pahlavig, Aramaic heterograms are listed together with their translation in the Middle Persian language and phonetic transcription in the Pazend alphabet. A 9th-century CE Irish dictionary, Sanas Cormaic, contained etymologies and explanations of over 1,400 Irish words. In the 12th century, The Karakhanid-Turkic scholar Mahmud Kashgari finished his work «Divan-u Lügat’it Türk», a dictionary about the Turkic dialects, but especially Karakhanid Turkic. His work contains about 7500 to 8000 words and it was written to teach non Turkic Muslims, especially the Abbasid Arabs, the Turkic language.[13] Al-Zamakhshari wrote a small Arabic dictionary called «Muḳaddimetü’l-edeb» for the Turkic-Khwarazm ruler Atsiz.[14] In the 14th century, the Codex Cumanicus was finished and it served as a dictionary about the Cuman-Turkic language. While in Mamluk Egypt, Ebû Hayyân el-Endelüsî finished his work «Kitâbü’l-İdrâk li-lisâni’l-Etrâk», a dictionary about the Kipchak and Turcoman languages spoken in Egypt and the Levant.[15] A dictionary called «Bahşayiş Lügati», which is written in old Anatolian Turkish, served also as a dictionary between Oghuz Turkish, Arabic and Persian. But it is not clear who wrote the dictionary or in which century exactly it was published. It was written in old Anatolian Turkish from the Seljuk period and not the late medieval Ottoman period.[16] In India around 1320, Amir Khusro compiled the Khaliq-e-bari, which mainly dealt with Hindustani and Persian words.[17]

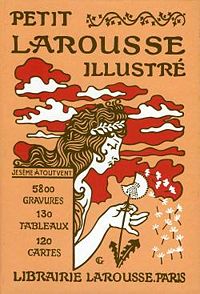

The French-language Petit Larousse is an example of an illustrated dictionary.

Arabic dictionaries were compiled between the 8th and 14th centuries CE, organizing words in rhyme order (by the last syllable), by alphabetical order of the radicals, or according to the alphabetical order of the first letter (the system used in modern European language dictionaries). The modern system was mainly used in specialist dictionaries, such as those of terms from the Qur’an and hadith, while most general use dictionaries, such as the Lisan al-`Arab (13th century, still the best-known large-scale dictionary of Arabic) and al-Qamus al-Muhit (14th century) listed words in the alphabetical order of the radicals. The Qamus al-Muhit is the first handy dictionary in Arabic, which includes only words and their definitions, eliminating the supporting examples used in such dictionaries as the Lisan and the Oxford English Dictionary.[18]

In medieval Europe, glossaries with equivalents for Latin words in vernacular or simpler Latin were in use (e.g. the Leiden Glossary). The Catholicon (1287) by Johannes Balbus, a large grammatical work with an alphabetical lexicon, was widely adopted. It served as the basis for several bilingual dictionaries and was one of the earliest books (in 1460) to be printed. In 1502 Ambrogio Calepino’s Dictionarium was published, originally a monolingual Latin dictionary, which over the course of the 16th century was enlarged to become a multilingual glossary. In 1532 Robert Estienne published the Thesaurus linguae latinae and in 1572 his son Henri Estienne published the Thesaurus linguae graecae, which served up to the 19th century as the basis of Greek lexicography. The first monolingual Spanish dictionary written was Sebastián Covarrubias’s Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española, published in 1611 in Madrid, Spain.[19] In 1612 the first edition of the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, for Italian, was published. It served as the model for similar works in French and English. In 1690 in Rotterdam was published, posthumously, the Dictionnaire Universel by Antoine Furetière for French. In 1694 appeared the first edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française (still published, with the ninth edition not complete as of 2021). Between 1712 and 1721 was published the Vocabulario portughez e latino written by Raphael Bluteau. The Real Academia Española published the first edition of the Diccionario de la lengua española (still published, with a new edition about every decade) in 1780; their Diccionario de Autoridades, which included quotes taken from literary works, was published in 1726. The Totius Latinitatis lexicon by Egidio Forcellini was firstly published in 1777; it has formed the basis of all similar works that have since been published.

The first edition of A Greek-English Lexicon by Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott appeared in 1843; this work remained the basic dictionary of Greek until the end of the 20th century. And in 1858 was published the first volume of the Deutsches Wörterbuch by the Brothers Grimm; the work was completed in 1961. Between 1861 and 1874 was published the Dizionario della lingua italiana by Niccolò Tommaseo. Between 1862 and 1874 was published the six volumes of A magyar nyelv szótára (Dictionary of Hungarian Language) by Gergely Czuczor and János Fogarasi. Émile Littré published the Dictionnaire de la langue française between 1863 and 1872. In the same year 1863 appeared the first volume of the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal which was completed in 1998. Also in 1863 Vladimir Ivanovich Dahl published the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language. The Duden dictionary dates back to 1880, and is currently the prescriptive source for the spelling of German. The decision to start work on the Svenska Akademiens ordbok was taken in 1787.[20]

English dictionaries in Britain

The earliest dictionaries in the English language were glossaries of French, Spanish or Latin words along with their definitions in English. The word «dictionary» was invented by an Englishman called John of Garland in 1220 – he had written a book Dictionarius to help with Latin «diction».[21] An early non-alphabetical list of 8000 English words was the Elementarie, created by Richard Mulcaster in 1582.[22][23]

The first purely English alphabetical dictionary was A Table Alphabeticall, written by English schoolteacher Robert Cawdrey in 1604.[2][3] The only surviving copy is found at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. This dictionary, and the many imitators which followed it, was seen as unreliable and nowhere near definitive. Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield was still lamenting in 1754, 150 years after Cawdrey’s publication, that it is «a sort of disgrace to our nation, that hitherto we have had no… standard of our language; our dictionaries at present being more properly what our neighbors the Dutch and the Germans call theirs, word-books, than dictionaries in the superior sense of that title.»[24]

In 1616, John Bullokar described the history of the dictionary with his «English Expositor». Glossographia by Thomas Blount, published in 1656, contains more than 10,000 words along with their etymologies or histories. Edward Phillips wrote another dictionary in 1658, entitled «The New World of English Words: Or a General Dictionary» which boldly plagiarized Blount’s work, and the two criticised each other. This created more interest in the dictionaries. John Wilkins’ 1668 essay on philosophical language contains a list of 11,500 words with careful distinctions, compiled by William Lloyd.[25] Elisha Coles published his «English Dictionary» in 1676.

It was not until Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) that a more reliable English dictionary was produced.[3] Many people today mistakenly believe that Johnson wrote the first English dictionary: a testimony to this legacy.[2][26] By this stage, dictionaries had evolved to contain textual references for most words, and were arranged alphabetically, rather than by topic (a previously popular form of arrangement, which meant all animals would be grouped together, etc.). Johnson’s masterwork could be judged as the first to bring all these elements together, creating the first «modern» dictionary.[26]

Johnson’s dictionary remained the English-language standard for over 150 years, until the Oxford University Press began writing and releasing the Oxford English Dictionary in short fascicles from 1884 onwards.[3][27] It took nearly 50 years to complete this huge work, and they finally released the complete OED in twelve volumes in 1928.[27] One of the main contributors to this modern dictionary was an ex-army surgeon, William Chester Minor, a convicted murderer who was confined to an asylum for the criminally insane.[28]

The OED remains the most comprehensive and trusted English language dictionary to this day, with revisions and updates added by a dedicated team every three months.

American English dictionaries

In 1806, American Noah Webster published his first dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language.[3] In 1807 Webster began compiling an expanded and fully comprehensive dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language; it took twenty-seven years to complete. To evaluate the etymology of words, Webster learned twenty-six languages, including Old English (Anglo-Saxon), German, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, Hebrew, Arabic, and Sanskrit.

Webster completed his dictionary during his year abroad in 1825 in Paris, France, and at the University of Cambridge. His book contained seventy thousand words, of which twelve thousand had never appeared in a published dictionary before. As a spelling reformer, Webster believed that English spelling rules were unnecessarily complex, so his dictionary introduced spellings that became American English, replacing «colour» with «color», substituting «wagon» for «waggon», and printing «center» instead of «centre». He also added American words, like «skunk» and «squash,» which did not appear in British dictionaries. At the age of seventy, Webster published his dictionary in 1828; it sold 2500 copies. In 1840, the second edition was published in two volumes. Webster’s dictionary was acquired by G & C Merriam Co. in 1843, after his death, and has since been published in many revised editions. Merriam-Webster was acquired by Encyclopedia Britannica in 1964.

Controversy over the lack of usage advice in the 1961 Webster’s Third New International Dictionary spurred publication of the 1969 The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, the first dictionary to use corpus linguistics.

Types

In a general dictionary, each word may have multiple meanings. Some dictionaries include each separate meaning in the order of most common usage while others list definitions in historical order, with the oldest usage first.[29]

In many languages, words can appear in many different forms, but only the undeclined or unconjugated form appears as the headword in most dictionaries. Dictionaries are most commonly found in the form of a book, but some newer dictionaries, like StarDict and the New Oxford American Dictionary are dictionary software running on PDAs or computers. There are also many online dictionaries accessible via the Internet.

Specialized dictionaries

According to the Manual of Specialized Lexicographies, a specialized dictionary, also referred to as a technical dictionary, is a dictionary that focuses upon a specific subject field, as opposed to a dictionary that comprehensively contains words from the lexicon of a specific language or languages. Following the description in The Bilingual LSP Dictionary, lexicographers categorize specialized dictionaries into three types: A multi-field dictionary broadly covers several subject fields (e.g. a business dictionary), a single-field dictionary narrowly covers one particular subject field (e.g. law), and a sub-field dictionary covers a more specialized field (e.g. constitutional law). For example, the 23-language Inter-Active Terminology for Europe is a multi-field dictionary, the American National Biography is a single-field, and the African American National Biography Project is a sub-field dictionary. In terms of the coverage distinction between «minimizing dictionaries» and «maximizing dictionaries», multi-field dictionaries tend to minimize coverage across subject fields (for instance, Oxford Dictionary of World Religions and Yadgar Dictionary of Computer and Internet Terms)[30] whereas single-field and sub-field dictionaries tend to maximize coverage within a limited subject field (The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology).

Another variant is the glossary, an alphabetical list of defined terms in a specialized field, such as medicine (medical dictionary).

Defining dictionaries

The simplest dictionary, a defining dictionary, provides a core glossary of the simplest meanings of the simplest concepts. From these, other concepts can be explained and defined, in particular for those who are first learning a language. In English, the commercial defining dictionaries typically include only one or two meanings of under 2000 words. With these, the rest of English, and even the 4000 most common English idioms and metaphors, can be defined.

Prescriptive vs. descriptive

Lexicographers apply two basic philosophies to the defining of words: prescriptive or descriptive. Noah Webster, intent on forging a distinct identity for the American language, altered spellings and accentuated differences in meaning and pronunciation of some words. This is why American English now uses the spelling color while the rest of the English-speaking world prefers colour. (Similarly, British English subsequently underwent a few spelling changes that did not affect American English; see further at American and British English spelling differences.)[31]

Large 20th-century dictionaries such as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and Webster’s Third are descriptive, and attempt to describe the actual use of words. Most dictionaries of English now apply the descriptive method to a word’s definition, and then, outside of the definition itself, provide information alerting readers to attitudes which may influence their choices on words often considered vulgar, offensive, erroneous, or easily confused.[32] Merriam-Webster is subtle, only adding italicized notations such as, sometimes offensive or stand (nonstandard). American Heritage goes further, discussing issues separately in numerous «usage notes.» Encarta provides similar notes, but is more prescriptive, offering warnings and admonitions against the use of certain words considered by many to be offensive or illiterate, such as, «an offensive term for…» or «a taboo term meaning…».

Because of the widespread use of dictionaries in schools, and their acceptance by many as language authorities, their treatment of the language does affect usage to some degree, with even the most descriptive dictionaries providing conservative continuity. In the long run, however, the meanings of words in English are primarily determined by usage, and the language is being changed and created every day.[33] As Jorge Luis Borges says in the prologue to «El otro, el mismo»: «It is often forgotten that (dictionaries) are artificial repositories, put together well after the languages they define. The roots of language are irrational and of a magical nature.»

Sometimes the same dictionary can be descriptive in some domains and prescriptive in others. For example, according to Ghil’ad Zuckermann, the Oxford English-Hebrew Dictionary is «at war with itself»: whereas its coverage (lexical items) and glosses (definitions) are descriptive and colloquial, its vocalization is prescriptive. This internal conflict results in absurd sentences such as hi taharóg otí kshetiré me asíti lamkhonít (she’ll tear me apart when she sees what I’ve done to the car). Whereas hi taharóg otí, literally ‘she will kill me’, is colloquial, me (a variant of ma ‘what’) is archaic, resulting in a combination that is unutterable in real life.[34]

Historical dictionaries

A historical dictionary is a specific kind of descriptive dictionary which describes the development of words and senses over time, usually using citations to original source material to support its conclusions.[35]

Dictionaries for natural language processing

In contrast to traditional dictionaries, which are designed to be used by human beings, dictionaries for natural language processing (NLP) are built to be used by computer programs. The final user is a human being but the direct user is a program. Such a dictionary does not need to be able to be printed on paper. The structure of the content is not linear, ordered entry by entry but has the form of a complex network (see Diathesis alternation). Because most of these dictionaries are used to control machine translations or cross-lingual information retrieval (CLIR) the content is usually multilingual and usually of huge size. In order to allow formalized exchange and merging of dictionaries, an ISO standard called Lexical Markup Framework (LMF) has been defined and used among the industrial and academic community.[36]

Other types

- Bilingual dictionary

- Collegiate dictionary (American)

- Learner’s dictionary (mostly British)

- Electronic dictionary

- Encyclopedic dictionary

- Monolingual learner’s dictionary

- Advanced learner’s dictionary

- By sound

- Rhyming dictionary

- Reverse dictionary (Conceptual dictionary)

- Visual dictionary

- Satirical dictionary

- Phonetic dictionary

Pronunciation

In many languages, such as the English language, the pronunciation of some words is not consistently apparent from their spelling. In these languages, dictionaries usually provide the pronunciation. For example, the definition for the word dictionary might be followed by the International Phonetic Alphabet spelling (in British English) or (in American English). American English dictionaries often use their own pronunciation respelling systems with diacritics, for example dictionary is respelled as «dĭk′shə-nĕr′ē» in the American Heritage Dictionary.[37] The IPA is more commonly used within the British Commonwealth countries. Yet others use their own pronunciation respelling systems without diacritics: for example, dictionary may be respelled as DIK-shə-nerr-ee. Some online or electronic dictionaries provide audio recordings of words being spoken.

Examples

Major English dictionaries

- A Dictionary of the English Language by Samuel Johnson (prescriptive)

- The American College Dictionary by Clarence L. Barnhart

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- Black’s Law Dictionary, a law dictionary

- Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable

- Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Century Dictionary

- Chambers Dictionary

- Collins English Dictionary

- Concise Oxford English Dictionary

- Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English / Longman

- Macmillan Dictionary

- Macquarie Dictionary, a dictionary of Australian English

- Merriam-Webster, a dictionary of American English

- Oxford Dictionary of English

- Oxford English Dictionary (descriptive) (well-known as OED/O.E.D.)

- Random House Dictionary of the English Language

- Webster’s New World Dictionary (especially the college edition, used as the official desk dictionary of many American press journalists)

Dictionaries of other languages

Histories and descriptions of the dictionaries of other languages on Wikipedia include:

- Arabic dictionaries

- Chinese dictionaries

- Dehkhoda Dictionary (Persian Language)

- Dutch dictionaries

- French dictionaries

- German dictionaries

- Japanese dictionaries

- Polish dictionaries

- Scottish Gaelic dictionaries

- Scottish Language Dictionaries

- Sindhi Language Dictionaries

Online dictionaries

The age of the Internet brought online dictionaries to the desktop and, more recently, to the smart phone. David Skinner in 2013 noted that «Among the top ten lookups on Merriam-Webster Online at this moment are holistic, pragmatic, caveat, esoteric and bourgeois. Teaching users about words they don’t already know has been, historically, an aim of lexicography, and modern dictionaries do this well.»[38]

There exist a number of websites which operate as online dictionaries, usually with a specialized focus. Some of them have exclusively user driven content, often consisting of neologisms. Some of the more notable examples are given in List of online dictionaries and Category:Online dictionaries.

See also

Books portal

- Comparison of English dictionaries

- Centre for Lexicography

- COBUILD, a large corpus of English text

- Corpus linguistics

- DICT, the dictionary server protocol

- Dictionary Society of North America

- Fictitious entry

- Foreign language writing aid

- Lexicographic error

- Lists of dictionaries

- Thesaurus

- Dreaming of Words

Notes

- ^ Webster’s New World College Dictionary, Fourth Edition, 2002

- ^ a b c Nordquist, Richard (August 9, 2019). «The Features, Functions, and Limitations of Dictionaries». ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e «Dictionary». Britannica. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Nielsen, Sandro (2008). «The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Dictionary Naming and Use». Lexikos. 18: 170–189. ISSN 1684-4904.

- ^ A Practical Guide to Lexicography, Sterkenburg 2003, pp. 155–157

- ^ a b A Practical Guide to Lexicography, Sterkenburg 2003, pp. 3–4

- ^ A Practical Guide to Lexicography, Sterkenburg 2003, p. 7

- ^ R. R. K. Hartmann (2003). Lexicography: Dictionaries, compilers, critics, and users. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-25366-6.

- ^ «DCCLT – Digital Corpus of Cuneiform Lexical Texts». oracc.museum.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ a b Dictionary – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29.

- ^ Jackson, Howard (2022-02-24). The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-18172-4.

- ^ Peter Bing (2003). «The unruly tongue: Philitas of Cos as scholar and poet». Classical Philology. 98 (4): 330–348. doi:10.1086/422370. S2CID 162304317.

- ^ Besim Atalay, Divanü Lügat-it Türk Dizini, TTK Basımevi, Ankara, 1986

- ^ Zeki Velidi Togan, Zimahşeri’nin Doğu Türkçesi İle Mukaddimetül Edeb’i

- ^ Ahmet Caferoğlu, Kitab Al Idrak Li Lisan Al Atrak, 1931

- ^ Bahşāyiş Bin Çalıça, Bahşayiş Lügati: Hazırlayan: Fikret TURAN, Ankara 2017,

- ^ Rashid, Omar. «Chasing Khusro». The Hindu. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ «Ḳāmūs», J. Eckmann, Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Brill

- ^ Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española, edición integral e ilustrada de Ignacio Arellano y Rafael Zafra, Madrid, Iberoamericana-Vervuert, 2006, pg. XLIX.

- ^ «OSA – Om svar anhålles». g3.spraakdata.gu.se. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Mark Forsyth. The etymologicon. // Icon Books Ltd. London N79DP, 2011. p. 128

- ^ «1582 – Mulcaster’s Elementarie». www.bl.uk. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ A Brief History of English Lexicography Archived 2008-03-09 at the Wayback Machine, Peter Erdmann and See-Young Cho, Technische Universität Berlin, 1999.

- ^ Jack Lynch, «How Johnson’s Dictionary Became the First Dictionary» (delivered 25 August 2005 at the Johnson and the English Language conference, Birmingham) Retrieved July 12, 2008,

- ^ John P. Considine (27 March 2008). Dictionaries in Early Modern Europe: Lexicography and the Making of Heritage. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-521-88674-1. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ a b «Lynch, «How Johnson’s Dictionary Became the First Dictionary»«. andromeda.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ a b «Oxford Dictionary Debuts». History. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne.

- ^ «Language Core Reference Sources – Texas State Library». Archived from the original on 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Times, The Sindh (24 February 2015). «The first English to Einglish and Sindhi Dictionary of Computer and Internet Terms published – The Sindh Times». Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Phil Benson (2002). Ethnocentrism and the English Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. pp. 8–11. ISBN 9780203205716.

- ^ Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade; Wim van der Wurff (2009). Current Issues in Late Modern English. Peter Lang. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9783039116607.

- ^ Ned Halley, The Wordsworth Dictionary of Modern English Grammar (2005), p. 84

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (1999). Review of the Oxford English-Hebrew Dictionary, International Journal of Lexicography 12.4, pp. 325-346.

- ^ See for example Toyin Falola, et al. Historical dictionary of Nigeria (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018) excerpt

- ^ Imad Zeroual, and Abdelhak Lakhouaja, «Data science in light of natural language processing: An overview.» Procedia Computer Science 127 (2018): 82-91 online.

- ^ «dictionary». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ Skinner, David (May 17, 2013). «The Role of a Dictionary». Opinionator. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

References

- Bergenholtz, Henning; Tarp, Sven, eds. (1995). Manual of Specialised Lexicography: The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 90-272-1612-6.

- Erdmann, Peter; Cho, See-Young. «A Brief History of English Lexicography». Technische Universität Berlin. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Landau, Sidney I. (2001) [1984]. Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78040-3.

- Nielsen, Sandro (1994). The Bilingual LSP Dictionary: Principles and Practice for Legal Language. Tübingeb: Gunter Narr. ISBN 3-8233-4533-8.

- Nielsen, Sandro (2008). «The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Dictionary Making and Use». Lexikos. 18: 170–189. ISSN 1684-4904.

- Atkins, B.T.S. & Rundell, Michael (2008) The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927771-1

- Winchester, Simon (1998). The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-099486-X. (published in the UK as The Surgeon of Crowthorne).

- P. G. J. van Sterkenburg, ed. (2003). A practical guide to lexicography. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-58811-381-8.

Further reading

- Guy Jean Forgue, «The Norm in American English», Revue Française d’Etudes Americaines, Nov 1983, Vol. 8 Issue 18, pp. 451–461. An international appreciation of the importance of Webster’s dictionaries in setting the norms of the English language.

External links

- Dictionary at Curlie

- Glossary of dictionary terms by the Oxford University Press

Texts on Wikisource:

- «Dictionary». Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- «Dictionary». Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- «Dictionary». New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Wikisource:Language (directory of language-related works on Wikisource – includes dictionaries)

For Wikimedia’s dictionary project visit Wiktionary, or see the Wiktionary article.

A dictionary (also called a wordbook, lexicon or vocabulary) is a collection of words in one or more specific languages, often listed alphabetically, with usage information, definitions, etymologies, phonetics, pronunciations, and other information;[1] or a book of words in one language with their equivalents in another, also known as a lexicon.[1] According to Nielsen (2008) a dictionary may be regarded as a lexicographical product that is characterised by three significant features: (1) it has been prepared for one or more functions; (2) it contains data that have been selected for the purpose of fulfilling those functions; and (3) its lexicographic structures link and establish relationships between the data so that they can meet the needs of users and fulfill the functions of the dictionary.

A broad distinction is made between general and specialized dictionaries. Specialized dictionaries do not contain information about words that are used in language for general purposes—words used by ordinary people in everyday situations. Lexical items that describe concepts in specific fields are usually called terms instead of words, although there is no consensus whether lexicology and terminology are two different fields of study. In theory, general dictionaries are supposed to be semasiological, mapping word to definition, while specialized dictionaries are supposed to be onomasiological, first identifying concepts and then establishing the terms used to designate them. In practice, the two approaches are used for both types.[2] There are other types of dictionaries that don’t fit neatly in the above distinction, for instance bilingual (translation) dictionaries, dictionaries of synonyms (thesauri), or rhyming dictionaries. The word dictionary (unqualified) is usually understood to refer to a monolingual general-purpose dictionary.[3]

A different dimension on which dictionaries (usually just general-purpose ones) are sometimes distinguished is whether they are prescriptive or descriptive, the latter being in theory largely based on linguistic corpus studies—this is the case of most modern dictionaries. However, this distinction cannot be upheld in the strictest sense. The choice of headwords is considered itself of prescriptive nature; for instance, dictionaries avoid having too many taboo words in that position. Stylistic indications (e.g. ‘informal’ or ‘vulgar’) present in many modern dictionaries is considered less than objectively descriptive as well.[4]

Although the first recorded dictionaries date back to Sumerian times (these were bilingual dictionaries), the systematic study of dictionaries as objects of scientific interest themselves is a 20th century enterprise, called lexicography, and largely initiated by Ladislav Zgusta.[3] The birth of the new discipline was not without controversy, the practical dictionary-makers being sometimes accused of «astonishing» lack of method and critical-self reflection.[5]

Contents

- 1 History

- 1.1 English Dictionaries

- 1.2 American Dictionaries

- 2 General dictionaries

- 3 Specialized dictionaries

- 4 Glossaries

- 5 Pronunciation

- 6 Variations between dictionaries

- 6.1 Prescription and description

- 7 Major English dictionaries

- 8 Dictionaries of other languages

- 9 Online dictionaries

- 10 See also

- 11 Notes

- 12 References

- 13 External links

History

The oldest known dictionaries were Akkadian Empire cuneiform tablets with bilingual Sumerian–Akkadian wordlists, discovered in Ebla (modern Syria) and dated roughly 2300 BCE.[6] The early 2nd millennium BCE Urra=hubullu glossary is the canonical Babylonian version of such bilingual Sumerian wordlists. A Chinese dictionary, the ca. 3rd century BCE Erya, was the earliest surviving monolingual dictionary, although some sources cite the ca. 800 BCE Shizhoupian as a «dictionary», modern scholarship considers it a calligraphic compendium of Chinese characters from Zhou dynasty bronzes. Philitas of Cos (fl. 4th century BCE) wrote a pioneering vocabulary Disorderly Words (Ἄτακτοι γλῶσσαι, Átaktoi glôssai) which explained the meanings of rare Homeric and other literary words, words from local dialects, and technical terms.[7] Apollonius the Sophist (fl. 1st century CE) wrote the oldest surviving Homeric lexicon.[6] The first Sanskrit dictionary, the Amarakośa, was written by Amara Sinha ca. 4th century CE. Written in verse, it listed around 10,000 words. According to the Nihon Shoki, the first Japanese dictionary was the long-lost 682 CE Niina glossary of Chinese characters. The oldest existing Japanese dictionary, the ca. 835 CE Tenrei Banshō Meigi, was also a glossary of written Chinese.

Arabic dictionaries were compiled between the 8th and 14th centuries CE, organizing words in rhyme order (by the last syllable), by alphabetical order of the radicals, or according to the alphabetical order of the first letter (the system used in modern European language dictionaries). The modern system was mainly used in specialist dictionaries, such as those of terms from the Qur’an and hadith, while most general use dictionaries, such as the Lisan al-`Arab (13th c., still the best-known large-scale dictionary of Arabic) and al-Qamus al-Muhit (14th c.) listed words in the alphabetical order of the radicals. The Qamus al-Muhit is the first handy dictionary in Arabic, which includes only words and their definitions, eliminating the supporting examples used in such dictionaries as the Lisan and the Oxford English Dictionary.[8]

The earliest modern European dictionaries were bilingual dictionaries. In 1502 appeared the Cornucopia of Ambrogio Calepino, which in fact was a multilingual glossary. In 1532 Robert Estienne published the Thesaurus linguae latinae and in 1572 his son Henri Estienne published the Thesaurus linguae graecae, which served up to the nineteenth century as the basis of Greek lexicography. In 1612 was published the first edition of the Vocabolario dell’Accademia della Crusca, for Italian, which also served as the model for similar works in French, Spanish and English. In 1690 in Rotterdam was published, posthumously, the Dictionnaire Universel by Antoine Furetière for French. In 1694 appeared the first edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française. Between 1712 and 1721 was published the Vocabulario portughez e latino written by Raphael Bluteau. The Real Academia Espanola published the first edition of the Diccionario de la lengua espanola in 1780. The Totius Latinitatis lexicon by Egidio Forcellini was firstly published in 1777, it has formed the basis of all similar works that have since been published.

The first edition of A Greek-English Lexicon by Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott appeared in 1843; this work remained the basic dictionary of Greek until the end of the XX century. And in 1858 was published the first volume of the Deutsches Wörterbuch by the Brothers Grimm; the work was completed in 1961. Between 1861 and 1874 was published the Dizionario della lingua italiana by Niccolò Tommaseo. Émile Littré published the Dictionnaire de la langue française between 1863 and 1872. In the same year 1863 appeared the first volume of the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal which was completed in 1998. Also in 1863 Vladimir Ivanovich Dahl published the Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language. The Duden dictionary dates back to 1880, and is currently the prescriptive source for the spelling of German. In 1898 was printed the first volume of the Svenska Akademiens ordbok, whose publication is still in progress.

English Dictionaries

The earliest dictionaries in the English language were glossaries of French, Italian or Latin words along with definitions of the foreign words in English. An early non-alphabetical list of 8000 English words was the Elementarie created by Richard Mulcaster in 1592.[9][10]

The first purely English alphabetical dictionary was A Table Alphabeticall, written by English schoolteacher Robert Cawdrey in 1604. The only surviving copy is found at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Yet this early effort, as well as the many imitators which followed it, was seen as unreliable and nowhere near definitive. Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield was still lamenting in 1754, 150 years after Cawdrey’s publication, that it is «a sort of disgrace to our nation, that hitherto we have had no… standard of our language; our dictionaries at present being more properly what our neighbors the Dutch and the Germans call theirs, word-books, than dictionaries in the superior sense of that title.» [11]

It was not until Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) that a truly noteworthy, reliable English Dictionary was deemed to have been produced, and the fact that today many people still mistakenly believe Johnson to have written the first English Dictionary is a testimony to this legacy.[12] By this stage, dictionaries had evolved to contain textual references for most words, and were arranged alphabetically, rather than by topic (a previously popular form of arrangement, which meant all animals would be grouped together, etc.). Johnson’s masterwork could be judged as the first to bring all these elements together, creating the first ‘modern’ dictionary.[12]

Johnson’s Dictionary remained the English-language standard for over 150 years, until the Oxford University Press began writing and releasing the Oxford English Dictionary in short fascicles from 1884 onwards. It took nearly 50 years to finally complete the huge work, and they finally released the complete OED in twelve volumes in 1928. It remains the most comprehensive and trusted English language dictionary to this day, with revisions and updates added by a dedicated team every three months. One of the main contributors to this modern day dictionary was an ex-army surgeon, William Chester Minor, a convicted murderer who was confined to an asylum for the criminally insane.[13]

American Dictionaries

In 1806, American Noah Webster published his first dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. In 1807 Webster began compiling an expanded and fully comprehensive dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language; it took twenty-seven years to complete. To evaluate the etymology of words, Webster learned twenty-six languages, including Old English (Anglo-Saxon), German, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, Hebrew, Arabic, and Sanskrit. Webster hoped to standardize American speech, since Americans in different parts of the country used different languages. They also spelled, pronounced, and used English words differently.

Webster completed his dictionary during his year abroad in 1825 in Paris, France, and at the University of Cambridge. His book contained seventy thousand words, of which twelve thousand had never appeared in a published dictionary before. As a spelling reformer, Webster believed that English spelling rules were unnecessarily complex, so his dictionary introduced American English spellings, replacing «colour» with «color», substituting «wagon» for «waggon», and printing «center» instead of «centre». He also added American words, like «skunk» and «squash», that did not appear in British dictionaries. At the age of seventy, Webster published his dictionary in 1828; it sold 2500 copies. In 1840, the second edition was published in two volumes.

Austin (2005) explores the intersection of lexicographical and poetic practices in American literature, and attempts to map out a «lexical poetics» using Webster’s definitions as his base. He explores how American poets used Webster’s dictionaries, often drawing upon his lexicography in order to express their word play. Austin explicates key definitions from both the Compendious (1806) and American (1828) dictionaries, and brings into its discourse a range of concerns, including the politics of American English, the question of national identity and culture in the early moments of American independence, and the poetics of citation and of definition. Austin concludes that Webster’s dictionaries helped redefine Americanism in an era of an emergent and unstable American political and cultural identity. Webster himself saw the dictionaries as a nationalizing device to separate America from Britain, calling his project a «federal language», with competing forces towards regularity on the one hand and innovation on the other. Austin suggests that the contradictions of Webster’s lexicography were part of a larger play between liberty and order within American intellectual discourse, with some pulled toward Europe and the past, and others pulled toward America and the new future.[14]

For an international appreciation of the importance of Webster’s dictionaries in setting the norms of the English language, see Forque (1982).[15]

General dictionaries

In a general dictionary, each word may have multiple meanings. Some dictionaries include each separate meaning in the order of most common usage while others list definitions in historical order, with the oldest usage first.[16]

In many languages, words can appear in many different forms, but only the undeclined or unconjugated form appears as the headword in most dictionaries. Dictionaries are most commonly found in the form of a book, but some newer dictionaries, like StarDict and the New Oxford American Dictionary are dictionary software running on PDAs or computers. There are also many online dictionaries accessible via the Internet.

Specialized dictionaries

According to the Manual of Specialized Lexicographies a specialized dictionary (also referred to as a technical dictionary) is a lexicon that focuses upon a specific subject field. Following the description in The Bilingual LSP Dictionary lexicographers categorize specialized dictionaries into three types. A multi-field dictionary broadly covers several subject fields (e.g., a business dictionary), a single-field dictionary narrowly covers one particular subject field (e.g., law), and a sub-field dictionary covers a singular field (e.g., constitutional law). For example, the 23-language Inter-Active Terminology for Europe is a multi-field dictionary, the American National Biography is a single-field, and the African American National Biography Project is a sub-field dictionary. In terms of the above coverage distinction between «minimizing dictionaries» and «maximizing dictionaries», multi-field dictionaries tend to minimize coverage across subject fields (for instance, Oxford Dictionary of World Religions) whereas single-field and sub-field dictionaries tend to maximize coverage within a limited subject field (The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology). See also LSP dictionary

Glossaries

Another variant is the glossary, an alphabetical list of defined terms in a specialised field, such as medicine or science. The simplest dictionary, a defining dictionary, provides a core glossary of the simplest meanings of the simplest concepts. From these, other concepts can be explained and defined, in particular for those who are first learning a language. In English, the commercial defining dictionaries typically include only one or two meanings of under 2000 words. With these, the rest of English, and even the 4000 most common English idioms and metaphors, can be defined.

Pronunciation

Dictionaries for languages for which the pronunciation of words is not apparent from their spelling, such as the English language, usually provide the pronunciation, often using the International Phonetic Alphabet. For example, the definition for the word dictionary might be followed by the phonemic spelling /ˈdɪkʃənɛri/. American dictionaries, however, often use their own pronunciation spelling systems, for example dictionary [dĭkʹ shə nâr ē] while the IPA is more commonly used within the British Commonwealth countries. Yet others use an ad hoc notation; for example, dictionary may become [DIK-shuh-nair-ee]. Some on-line or electronic dictionaries provide recordings of words being spoken.

Variations between dictionaries

Prescription and description

Lexicographers apply two basic philosophies to the defining of words: prescriptive or descriptive. Noah Webster, intent on forging a distinct identity for the American language, altered spellings and accentuated differences in meaning and pronunciation of some words. This is why American English now uses the spelling color while the rest of the English-speaking world prefers colour. (Similarly, British English subsequently underwent a few spelling changes that did not affect American English; see further at American and British English spelling differences.) Large 20th-century dictionaries such as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and Webster’s Third are descriptive, and attempt to describe the actual use of words.

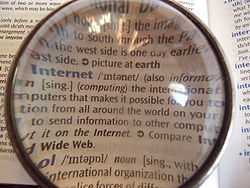

A dictionary open at the word «Internet», viewed through a lens

While descriptivists argue that prescriptivism is an unnatural attempt to dictate usage or curtail change, prescriptivists argue that to indiscriminately document «improper» or «inferior» usages sanctions those usages by default and causes language to deteriorate. Although the debate can become very heated, only a small number of controversial words are usually affected. But the softening of usage notations, from the previous edition, for two words, ain’t and irregardless, out of over 450,000 in Webster’s Third in 1961, was enough to provoke outrage among many with prescriptivist leanings, who branded the dictionary as «permissive.»

The prescriptive/descriptive issue has been given much consideration in modern times. Most dictionaries of English now apply the descriptive method to a word’s definition, and then, outside of the definition itself, add information alerting readers to attitudes which may influence their choices on words often considered vulgar, offensive, erroneous, or easily confused. Merriam-Webster is subtle, only adding italicized notations such as, sometimes offensive or nonstand (nonstandard.) American Heritage goes further, discussing issues separately in numerous «usage notes.» Encarta provides similar notes, but is more prescriptive, offering warnings and admonitions against the use of certain words considered by many to be offensive or illiterate, such as, «an offensive term for…» or «a taboo term meaning…»

Because of the widespread use of dictionaries in schools, and their acceptance by many as language authorities, their treatment of the language does affect usage to some degree, even the most descriptive dictionaries providing conservative continuity. In the long run, however, the meanings of words in English are primarily determined by usage, and the language is being changed and created every day.[17] As Jorge Luis Borges says in the prologue to «El otro, el mismo»: «It is often forgotten that (dictionaries) are artificial repositories, put together well after the languages they define. The roots of language are irrational and of a magical nature.«

Major English dictionaries

|

|

Dictionaries of other languages

Histories and descriptions of the dictionaries of other languages include Scottish Language Dictionaries, Japanese dictionary, Chinese dictionary, and the list of French dictionaries.

Online dictionaries

There exist a number of websites which operate as online dictionaries, usually with a specialized focus. Some of them have exclusively user driven content, often consisting of neologisms. Some of the more notable examples include:

|

|

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ a b Webster’s New World College Dictionary, Fourth Edition, 2002

- ^ Sterkenburg 2003, pp. 155–157

- ^ a b Sterkenburg 2003, pp. 3–4

- ^ Sterkenburg 2003, p. 7

- ^ R. R. K. Hartmann (2003). Lexicography: Dictionaries, compilers, critics, and users. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9780415253666. http://books.google.com/books?id=hLlhyvpg7KoC&pg=PA21.

- ^ a b «Dictionary – MSN Encarta». Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwbLyr75.

- ^ Peter Bing (2003). «The unruly tongue: Philitas of Cos as scholar and poet». Classical Philology 98 (4): 330–348. doi:10.1086/422370.

- ^ «Ḳāmūs», J. Eckmann, Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Brill

- ^ 1582 – Mulcaster’s Elementarie, Learning Dictionaries and Meaning, The British Library

- ^ A Brief History of English Lexicography, Peter Erdmann and See-Young Cho, Technische Universität Berlin, 1999.

- ^ Jack Lynch, “How Johnson’s Dictionary Became the First Dictionary” (delivered 25 August 2005 at the Johnson and the English Language conference, Birmingham) Retrieved July 12, 2008

- ^ a b Lynch, «How Johnson’s Dictionary Became the First Dictionary»

- ^ Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne.

- ^ Nathan W. Austin, «Lost in the Maze of Words: Reading and Re-reading Noah Webster’s Dictionaries», Dissertation Abstracts International, 2005, Vol. 65 Issue 12, p. 4561

- ^ Guy Jean Forgue, «The Norm in American English,» Revue Francaise d’Etudes Americaines, Nov 1983, Vol. 8 Issue 18, pp 451–461

- ^ http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/ld/pubs/corereference/internal/chd.html

- ^ Ned Halley, The Wordsworth Dictionary of Modern English Grammar (2005) p. 84

References

- Bergenholtz, Henning; Tarp, Sven, eds (1995). Manual of Specialised Lexicography: The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027216126.

- Erdmann, Peter; Cho, See-Young. «A Brief History of English Lexicography». Technische Universität Berlin. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080309181613/http://angli02.kgw.tu-berlin.de/lexicography/b_history.html. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Landau, Sidney I. (2001) [1984]. Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521780403.

- Nielsen, Sandro (1994). The Bilingual LSP Dictionary: Principles and Practice for Legal Language. Tübingeb: Gunter Narr. ISBN 3823345338.

- Nielsen, Sandro (2008). «The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Dictionary Making and Use». Lexikos 18: 170–189. ISSN 1684-4904.

- Atkins, B.T.S. & Rundell, Michael (2008) The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978019927771-1

- Winchester, Simon (1998). The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 006099486X. (published in the UK as The Surgeon of Crowthorne).

- P. G. J. van Sterkenburg, ed (2003). A practical guide to lexicography. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9781588113818.

External links

- Dictionary at the Open Directory Project

- Glossary of dictionary terms by the Oxford University Press

Texts on Wikisource:

- «Dictionary». Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). «Dictionary». Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- «Dictionary». New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Wikisource:Languages (directory of language-related works on Wikisource – includes dictionaries)

| v · d · eLexicography | |

|---|---|

| Types of reference works |

Dictionary · Glossary · Lexicon · Thesaurus |

| Types of dictionaries |

Bilingual · Biographical · Conceptual · Defining · Electronic · Encyclopedic · Language for specific purposes dictionary · Machine-readable · Maximizing · Medical · Minimizing · Monolingual learner’s · Multi-field · Phonetic · Picture · Reverse · Rhyming · Rime · Single-field · Specialized · Sub-field · Visual |

| Lexicographic projects |

Lexigraf · WordNet |

| Other |

List of lexicographers · List of online dictionaries |

| v · d · eLexicology | |

|---|---|

| Major terms |

Lexicon · Idiolect · Word · Lexis · Lexical unit |

| Elements |

Morpheme · Grapheme · Glyphs · Phoneme · Sememe · Seme · Lexeme · Lemma · Meronymy · Chereme |

| Semantic relations |

Holonymy · Hyponymy · Troponymy · Idiom · Synonym · Antonymy · Lexical semantics · Semantic net |

| Fonctions |

Function word · Headword |

| Fields |

Morphology · Controlled vocabulary · English lexicology and lexicography · Lexicographic error · Lexicographic information cost · Linguistic prescription · Specialised lexicography · International scientific vocabulary |

| v · d · eDictionaries of English | |

|---|---|

| Old and Middle English dictionaries |

An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary · Dictionary of Old English · Middle English Dictionary |

| Historic dictionaries |

A Dictionary of the English Language · The New World of English Words · A New English Dictionary · An Universal Etymological English Dictionary |

| Descriptive dictionaries |

Oxford English Dictionary · Dictionary of American English · Australian Oxford Dictionary · Canadian Oxford Dictionary · Century Dictionary · Dictionary of American Regional English · Merriam–Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage · Webster’s Third New International Dictionary |

| Prescriptive dictionaries |

The American Heritage Dictionary · Webster’s Dictionary · Chambers Dictionary · Collins English Dictionary · New Oxford American Dictionary · Webster’s New World Dictionary · Concise Oxford English Dictionary · Macquarie Dictionary · Oxford Dictionary of English · Penguin English Dictionary · Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary · Shorter Oxford English Dictionary · World Book Dictionary |

| Online collaborative dictionaries |

Collaborative International Dictionary of English · Urban Dictionary |

| Learners/ESL dictionaries |

Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary · Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary · Collins COBUILD Advanced Dictionary · Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English · Merriam-Webster’s Advanced Learner’s English Dictionary · Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners |

| Slang dictionaries |

Historical Dictionary of American Slang · A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew · A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English |

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions. - Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

A multi-volume Latin dictionary in the University Library of Graz.

A dictionary is basically a list words in a specific language, with definitions, etymologies, pronunciations, and other information; or a list of words in one language with their equivalents in another, also known as a lexicon. Generally, the words are given in alphabetical order. In many languages, words can appear in many different forms, but only the undeclined or unconjugated form appears as the headword in most dictionaries. Historical information about the words’ use, including quotations, may also be included.

The purposes of a dictionary are, thus, many; with different types of dictionaries focusing on different purposes. Generally, though, a dictionary is a valuable source of information about a language, allowing members of the public to improve their knowledge of the history and use of the words they encounter in all aspects of their lives. This improves their ability to communicate both in spoken and written language, with members of their contemporary society and those of different cultures, as well as better understanding the written works of others they do not meet face to face.

Dictionaries are most commonly found in the form of a book, but some newer dictionaries, such as the New Oxford American Dictionary are dictionary software running on PDAs or computers. There are also many online dictionaries accessible via the Internet. Thus, dictionaries advance along with advances in technology, maintaining appropriate ease of use and, thus, continue to have a valuable role even as human society advances.

History

As far as archaeologists have been able to determine, Ancient Mesopotamians were the first to create dictionaries, carving cuneiform words and their Akkadian equivalents on clay tablets.[1] Other ancient dictionaries include the Shuowen Jiezi from China, and a Greek lexicon (specifically a list of words used by Homer, and their meanings) written by Apollonius the Sophist.[1]

The earliest European dictionaries were bilingual dictionaries. These were glossaries of French, Italian, or Latin words, along with definitions of the foreign words in English. An early non-alphabetical list of 8000 English words was the Elementarie, created by Richard Mulcaster in 1592.[2]

The first purely English alphabetical dictionary was A Table Alphabeticall, written by English schoolteacher Robert Cawdrey in 1604. It was eight years ahead of the first Italian dictionary and thirty-five years ahead of the French. Conversely, it is eight hundred years after the first Arabic, and almost one-thousand years after the first Sanskrit dictionary in India. The only surviving copy of Cawdrey’s work is found at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Yet, this early effort, as well as the many imitators which followed it, was seen as unreliable and nowhere near definitive. It was not until Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) that a truly noteworthy, reliable English dictionary was deemed to have been produced, and the fact that today many people still mistakenly believe Johnson to have written the first English dictionary is a testament to this legacy.[3] By this stage, dictionaries had evolved to contain textual references for most words, and were arranged alphabetically, rather than by topic (a previously popular form of arrangement, which meant all animals would be grouped together, for example). Johnson’s masterwork could be judged as the first to bring all these elements together, creating the first «modern» dictionary.[3]

Johnson’s dictionary remained the English-language standard for over 150 years, until the Oxford University Press began writing and releasing the Oxford English Dictionary in short fascicles from 1884 onwards. It took nearly 50 years to finally complete the huge work, and they finally released the complete OED in 12 volumes in 1928. It remains the most comprehensive and trusted English language dictionary to this day, with revisions and updates added by a dedicated team every three months.[4]

Meanwhile, in 1806, Noah Webster published A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. The following year, at the age of 43, he began writing an expanded and comprehensive dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language, which would take 27 years to complete. Webster hoped to standardize American speech, since Americans in different parts of the country spelled, pronounced, and used words differently. His book contained 70,000 words, of which 12,000 had never appeared in any earlier published dictionary. As a spelling reformer, Webster believed that English spelling rules were unnecessarily complex, so his dictionary introduced American English spellings like «color» instead of «colour,» «wagon» instead of «waggon,» «center» instead of «centre,» and «honor» instead of «honour.» He also added American words that were not in British dictionaries like «skunk» and «squash.» Though it now has an honored place in the history of American English, Webster’s first dictionary, published in 1828, sold only 2,500 copies. Webster died in 1843, a few days after he had completed revising an appendix to the second edition. George and Charles Merriam secured publishing and revision rights to the 1840 edition of the dictionary, publishing a modest revision in 1847. In 1864, Merriam published a much expanded edition, largely overhauling Noah Webster’s work, yet retaining Webster’s title, An American Dictionary. This began a series of revisions known as Unabridged, which became increasingly more «Merriam» than «Webster.»

Purpose

Dictionaries exist primarily as reference material on a particular language or languages. In modern times dictionaries are often used to the reference the correct spelling, pronunciation, etymology, meaning and/or usage of a particular word. Bi-lingual dictionaries are often consulted to reference one word’s equivalent in another language (a Spanish-English dictionary will often give the Spanish translation of English words, and vice versa, but not necessarily give the word’s meaning). More academic uses of dictionaries include records of languages, either to trace the roots and evolution of a particular language, or to document those languages that are dying or are extinct. Picture dictionaries contain word entries that, for all or most such entries, are accompanied by photos or drawings illustrating what the words mean. They are usually used with young children, but are also useful when one knows (or has an idea of) what something looks like, but lacks the correct term for it.

Organization

Dictionaries can vary widely in coverage, size, and scope. A maximizing dictionary lists as many words as possible from a particular speech community (such as the Oxford English Dictionary), whereas a minimizing dictionary exclusively attempts to cover only a limited selection of words from a speech community (such as a dictionary of Basic English words). The word order of dictionaries depend upon the language it is based upon. Most languages with alphabetic and syllabic writing systems, such as English, French, and Italian, list words in lexicographic order, usually alphabetical or some analogous phonetic system. In dictionaries of some other languages, most notable Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic, words are grouped together according to their root word, with the roots being arranged alphabetically.[5] If English dictionaries were arranged like this, the words «import,» «export,» «support,» «report,» «porter,» «important,» and «transportation» would theoretically be listed under the Latin portare, «to carry.» This method has the advantage that all words of a common origin are listed together, but the disadvantage is that one must know the roots of a word in order to find it.

While most Japanese and Korean dictionaries are arranged according to their phonetic writing (kana syllabic script for the Japanese, and hangul alphabet for the Korean), the main body of modern Chinese dictionaries is ordered according to the latin alphabet with the pinyin spelling; but most Chinese dictionaries have an appendix ordering entries accordance to the Chinese logographic writing system, in order to allow readers to find words written in logograms whose pronunciation is not known. Chinese characters may be sorted according to one of many schemes based on the component parts of the characters (radicals, number of strokes, overall shape).[6]

Dictionaries for languages for which the pronunciation of words is not apparent from their spelling, such as the English language, usually provide the pronunciation, often using the International Phonetic Alphabet. For example, the definition for the word «dictionary» might be followed by the (American English) phonemic spelling: /ˈdɪkʃəˌnɛri/. English dictionaries, however, often use other systems, such as the English Phonemic Representation system, in which the pronunciation of «dictionary» is given as [dĭk’shə-něr’ē]. Yet others use an ad hoc notation; for example, «dictionary» may become [DIK-shuh-ner-ee].

Issues

Dictionaries function as a record and reference for a particular language, yet there are times when a dictionary can actually affect the lexicon of the language it is trying to document. One of the clearest examples is the debate between how words are recorded in the dictionary.

Dictionary makers apply two basic philosophies to the defining of words: prescriptive or descriptive. Noah Webster, intent on forging a distinct identity for the American language, altered spellings and accentuated differences in meaning and pronunciation of some words. This is why American English now uses the spelling color while the rest of the English-speaking world prefers colour.[7] Similarly, British English subsequently underwent a few spelling changes that did not affect American English. Large twentieth century dictionaries, such as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and Webster’s Third are descriptive, and attempt to describe the actual use of words.

While descriptivists argue that prescriptivism is an unnatural attempt to dictate usage or curtail change, prescriptivists argue that to indiscriminately document «improper» or «inferior» usages sanctions them by default and causes language to «deteriorate.» Although the debate can become very heated, only a small number of controversial words are actually affected. However, the softening of usage notations from the previous edition for two words, ain’t and regardless, out of over 450,000 in Webster’s Third in 1961, was enough to provoke outrage among many with prescriptivist leanings, who branded the dictionary as «permissive.»[8]

The prescriptive/descriptive issue has been given so much consideration in modern times that most dictionaries of English apply the descriptive method to definitions, while additionally informing readers of attitudes which may influence their choices on words often considered vulgar, offensive, erroneous, or easily confused. Merriam-Webster is subtle, only adding italicized notations such as, sometimes offensive or nonstand (nonstandard) American Heritage goes further, discussing issues separately in numerous «usage notes.» Encarta Webster’s Dictionary of the English Language provides similar notes, but is more prescriptive, offering warnings and admonitions against the use of certain words considered by many to be offensive or illiterate, such as, «an offensive term for…» or «a taboo term meaning….»

Specialized dictionaries

There are several different types of dictionaries that focus on specific groups of words or areas of specialized interest.

For example, a medical dictionary is a lexicon for words used in medicine, while a law dictionary is a dictionary that is designed and compiled to give information about terms used in the field of law. A multi-field dictionary broadly covers several semantic fields (such as a dictionary of the social sciences), a single-field dictionary narrowly covers one particular subject field (such as law), and a sub-field dictionary covers a singular field (such as constitutional law). In terms of the above coverage distinction between «minimizing dictionaries» and «maximizing dictionaries,» multi-field dictionaries tend to minimize coverage across lexical fields (for instance, Oxford Dictionary of World Religions) whereas single-field and sub-field dictionaries tend to maximize coverage within a limited subject field (such as The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology).

There are also Language for Specific Purposes (LSP) dictionaries that describe a variety of one or more languages used by experts within a particular subject field.

Data dictionaries

Data sets and databases collected and utilized for statistical analyses are typically accompanied by, or able to be used to generate, a list of all variable names used within the data set, as well as matters such as their meaning, values, level of measurement, length, decimal allowances, and type (numeric, string, and so forth).

Glossaries