From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A tablet from c. 65 AD, reading «Londinio Mogontio»- «In London, to Mogontius»

The name of London is derived from a word first attested, in Latinised form, as Londinium. By the first century CE, this was a commercial centre in Roman Britain.

The etymology of the name is uncertain. There is a long history of mythicising etymologies, such as the twelfth-century Historia Regum Britanniae asserting that the city’s name is derived from the name of King Lud who once controlled the city. However, in recent times a series of alternative theories have also been proposed. As of 2017, the trend in scholarly publications supports derivation from a Brittonic form *Londonjon, which would itself have been of Celtic origin.[1][2]

Attested forms[edit]

Richard Coates, in the 1998 article where he published his own theory of the etymology, lists all the known occurrences of the name up to around the year 900, in Greek, Latin, British and Anglo-Saxon.[3] Most of the older sources begin with Londin- (Λονδίνιον, Londino, Londinium etc.), though there are some in Lundin-. Later examples are mostly Lundon- or London-, and all the Anglo-Saxon examples have Lunden- with various terminations. He observes that the modern spelling with <o> derives from a medieval writing habit of avoiding <u> between letters composed of minims.

The earliest written mention of London occurs in a letter discovered in London in 2016. Dated AD 65–80, it reads Londinio Mogontio which translates to «In London, to Mogontius».[4][5][6][7] Mogontio, Mogontiacum is also the Celtic name of the German city Mainz.

Phonology[edit]

Coates (1998) asserts that «It is quite clear that these vowel letters in the earliest forms [viz., Londinium, Lundinium], both <o> and <u>, represent phonemically long vowel sounds». He observes that the ending in Latin sources before 600 is always -inium, which points to a British double termination -in-jo-n.

However, it has long been observed that the proposed Common Brittonic name *Londinjon cannot give either the known Anglo-Saxon form Lunden, or the Welsh form Llundein. Following regular sound changes in the two languages, the Welsh name would have been *Lunnen or similar, and Old English would be *Lynden via i-mutation.[8]

Coates (1998) tentatively accepts the argument by Jackson (1938)[9] that the British form was -on-jo-n, with the change to -inium unexplained. Coates speculates further that the first -i- could have arisen by metathesis of the -i- in the last syllable of his own suggested etymon (see below).

Peter Schrijver (2013) by way of explaining the medieval forms Lunden and Llundein considers two possibilities:

- In the local dialect of Lowland British Celtic, which later became extinct, -ond- became -und- regularly, and -ī- became -ei-, leading to Lundeinjon, later Lundein. The Welsh and English forms were then borrowed from this. This hypothesis requires that the Latin form have a long ī: Londīnium.

- The early British Latin dialect probably developed similarly as the dialect of Gaul (the ancestor of Old French). In particular, Latin stressed short i developed first into close-mid /e/, then diphthongised to /ei/. The combination -ond- also developed regularly into -und- in pre-Old French. Thus, he concludes, the remaining Romans of Britain would have pronounced the name as Lundeiniu, later Lundein, from which the Welsh and English forms were then borrowed. This hypothesis requires that the Latin form have a short i: Londinium.

Schrijver therefore concludes that the name of Londinium underwent phonological changes in a local dialect (either British Celtic or British Latin) and that the recorded medieval forms in Welsh and Anglo-Saxon would have been derived from that dialectal pronunciation.

Proposed etymologies[edit]

Celtic[edit]

Coates says (p. 211) that «The earliest non-mythic speculation … centred on the possibility of deriving London from Welsh Llyn din, supposedly ‘lake fort’. But llyn derives from British *lind-, which is incompatible with all the early attestations.[3] Another suggestion, published in The Geographical Journal in 1899, is that the area of London was previously settled by Belgae who named their outposts after townships in Gallia Belgica. Some of these Belgic toponyms have been attributed to the namesake of London including Limé, Douvrend, and Londinières.[10]

H. D’Arbois de Jubainville suggested in 1899 that the name meant Londino’s fortress.[11] But Coates argues that there is no such personal name recorded, and that D’Arbois’ suggested etymology for it (from Celtic *londo-, ‘fierce’) would have a short vowel. Coates notes that this theory was repeated by linguistics up to the 1960s, and more recently still in less specialist works. It was revived in 2013 by Peter Schrijver, who suggested that the sense of the proto-Indo-European root *lendh— (‘sink, cause to sink’), which gave rise to the Celtic noun *londos (‘a subduing’), survived in Celtic. Combined with the Celtic suffix *-injo— (used to form singular nouns from collective ones), this could explain a Celtic form *londinjon ‘place that floods (periodically, tidally)’. This, in Schrijver’s reading, would more readily explain all the Latin, Welsh, and English forms.[1] Similar approaches to Schrijver’s have been taken by Theodora Bynon, who in 2016 supported a similar Celtic etymology, while demonstrating that the place-name was borrowed into the West Germanic ancestor-language of Old English, not into Old English itself.[2]

Coates (1998) proposes a Common Brittonic form of either *Lōondonjon or *Lōnidonjon, which would have become *Lūndonjon and hence Lūndein or Lūndyn. An advantage of the form *Lōnidonjon is that it could account for Latin Londinium by metathesis to *Lōnodinjon. The etymology of this *Lōondonjon would however lie in pre-Celtic Old European hydronymy, from a hydronym *Plowonida, which would have been applied to the Thames where it becomes too wide to ford, in the vicinity of London. The settlement on its banks would then be named from the hydronym with the suffix -on-jon, giving *Plowonidonjon and Insular Celtic *Lowonidonjon. According to this approach, the name of the river itself would be derived from the Indo-European roots *plew- «to flow, swim; boat» and *nejd- «to flow», found in various river names around Europe. Coates does admit that compound names are comparatively rare for rivers in the Indo-European area, but they are not entirely unknown.[3] Lacey Wallace describes the derivation as «somewhat tenuous».[12]

Non-Celtic[edit]

Among the first scientific explanations was one by Giovanni Alessio in 1951.[3][13] He proposed a Ligurian rather than a Celtic origin, with a root *lond-/lont- meaning ‘mud’ or ‘marsh’. Coates’ major criticisms are that this does not have the required long vowel (an alternative form Alessio proposes, *lōna, has the long vowel, but lacks the required consonant), and that there is no evidence of Ligurian in Britain.

Jean-Gabriel Gigot in a 1974 article discusses the toponym of Saint-Martin-de-Londres, a commune in the French Hérault département. Gigot derives this Londres from a Germanic root *lohna, and argues that the British toponym may also be from that source.[14] But a Germanic etymology is rejected by most specialists.[15]

Historical and popular suggestions[edit]

The earliest account of the toponym’s derivation can be attributed to Geoffrey of Monmouth. In Historia Regum Britanniae, the name is described as originating from King Lud, who seized the city Trinovantum and ordered it to be renamed in his honour as Kaerlud. This eventually developed into Karelundein and then London. However, Geoffrey’s work contains many fanciful suppositions about place-name derivation and the suggestion has no basis in linguistics.[16]

Other fanciful theories over the years have been:

- William Camden reportedly suggested that the name might come from Brythonic lhwn (modern Welsh Llwyn), meaning «grove», and «town». Thus, giving the origin as Lhwn Town, translating to «city in the grove».[17]

- John Jackson, writing in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1792,[18] challenges the Llyn din theory (see below) on geographical grounds, and suggests instead a derivation from Glynn din – presumably intended as ‘valley city’.

- Some British Israelites claimed that the Anglo-Saxons, assumed to be descendants of the Tribe of Dan, named their settlement lan-dan, meaning «abode of Dan» in Hebrew.[19]

- An unsigned article in The Cambro Briton for 1821[20] supports the suggestion of Luna din (‘moon fortress’), and also mentions in passing the possibility of Llong din (‘ship fortress’).

- Several theories were discussed in the pages of Notes and Queries on 27 December 1851,[21] including Luandun (supposedly «city of the moon», a reference to the temple of Diana supposed to have stood on the site of St Paul’s Cathedral), and Lan Dian or Llan Dian («temple of Diana»). Another correspondent dismissed these, and reiterated the common Llyn din theory.

- In The Cymry of ’76 (1855),[22] Alexander Jones says that the Welsh name derives from Llyn Dain, meaning ‘pool of the Thames’.

- An 1887 Handbook for Travellers[23] asserts that «The etymology of London is the same as that of Lincoln» (Latin Lindum).

- The general Henri-Nicolas Frey, in his 1894 book Annamites et extrême-occidentaux: recherches sur l’origine des langues,[24] emphasises the similarity between the name of the city and the two Vietnamese words lœun and dœun which can both mean «low, inferior, muddy».

- Edward P. Cheney, in his 1904 book A Short History of England (p. 18), attributes the origin of the name to dun: «Elevated and easily defensible spots were chosen [in pre-Roman times], earthworks thrown up, always in a circular form, and palisades placed upon these. Such a fortification was called a dun, and London and the names of many other places still preserve that termination in varying forms.»

- A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare (1918)[25] mentions a variant on Geoffrey’s suggestion being Lud’s town, although refutes it saying that the origin of the name was most likely Saxon.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages, Routledge Studies in Linguistics, 13 (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 57.

- ^ a b Theodora Bynon, ‘London’s Name’, Transactions of the Philological Society, 114:3 (2016), 281–97, doi: 10.1111/1467-968X.12064.

- ^ a b c d Coates, Richard (1998). «A new explanation of the name of London». Transactions of the Philological Society. 96 (2): 203–229. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00027.

- ^ «Earliest written reference to London found», on Current Archaeology, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «UK’s oldest hand-written document ‘at Roman London dig'», on BBC News, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «Oldest handwritten documents in UK unearthed in London dig», in The Guardian, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 26 January 2018.

- ^ «Oldest reference to Roman London found in new tube station entrance», on IanVisits, 1 June 2016. Retrieved on 2022-11-27.

- ^ Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages (2013), p. 57.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth H. (1938). «Nennius and the 28 cities of Britain». Antiquity. 12: 44–55. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00013405. S2CID 163506021.

- ^ «The Geographical Journal». The Geographical Journal. 1899.

- ^ D’Arbois de Jubainville, H (1899). La Civilisation des Celtes et celle de l’épopée homérique (in French). Paris: Albert Fontemoing.

- ^ Wallace, Lacey (2015). The Origin of Roman London. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781107047570.

- ^ Alessio, Giovanni (1951). «L’origine du nom de Londres». Actes et Mémoires du troisième congrès international de toponymie et d’anthroponymie (in French). Louvain: Instituut voor naamkunde. pp. 223–224.

- ^ Gigot, Jean-Gabriel (1974). «Notes sur le toponyme «Londres» (Hérault)». Revue international d’onomastique. 26: 284–292. doi:10.3406/rio.1974.2193. S2CID 249329873.

- ^ Ernest Nègre, Toponymie générale de la France, Librairie Droz, Genève, p. 1494 [1]

- ^ Legends of London’s Origins

- ^ Prickett, Frederick (1842). «The history and antiquities of Highgate, Middlesex»: 4.

- ^ Jackson, John (1792). «Conjecture on the Etymology of London». The Gentleman’s Magazine. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

- ^ Gold, David L (1979). «English words of supposed Hebrew origin in George Crabb’s «English Synonymes»«. American Speech. Duke University Press. 51 (1): 61–64. doi:10.2307/454531. JSTOR 454531.

- ^ «Etymology of ‘London’«. The Cambro Briton: 42–43. 1821.

- ^ «Notes and Queries». 1852.

- ^ Jones, Alexander (1855). The Cymry of ’76. New York: Sheldon, Lamport. p. 132.

etymology of london.

- ^ Baedeker, Karl (1887). London and Its Environs: Handbook for Travellers. K. Baedeker. p. 60.

- ^ Henry, Frey (1894). Annamites et extrême-occidentaux: recherches sur l’origine des langues. Hachette et Cie.

- ^ Furness, Horace Howard, ed. (1918). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. J B Lippincott & co. ISBN 0-486-21187-8.

Londinium.

The name of London is derived from a word first attested, in Latinised form, as Londinium. By the first century CE, this was a commercial centre in Roman Britain.

Contents

- 1 What was the original name of London?

- 2 What was London called in Viking times?

- 3 What was London before it was London?

- 4 What is the origin of the word London?

- 5 What is another name for London?

- 6 When did London start being called London?

- 7 Did the Vikings Occupy London?

- 8 Is Lunden a London?

- 9 Did the Vikings sack London?

- 10 Who first settled London?

- 11 Why London is called the swinging city?

- 12 What is London known for?

- 13 What is the nickname for England?

- 14 What did the Romans call England?

- 15 Is Vikings Valhalla a true story?

- 16 Is London in Mercia?

- 17 Who defeated the Vikings in England?

- 18 Is London part of Wessex?

- 19 Are Danes Germanic?

- 20 Where is Wessex now?

What was the original name of London?

Londinium

Ancient Romans founded a port and trading settlement called Londinium in 43 A.D., and a few years later a bridge was constructed across the Thames to facilitate commerce and troop movements.

What was London called in Viking times?

Lundwic

By the 8th century, Lundwic was a prosperous trading centre, both by land and sea. The term “Wic” itself means “trading town” and was derived from the latin word Vicus. So Lundenwic can loosely be translated as “London Trading Town.”

What was London before it was London?

Londinium was established as a civilian town by the Romans about four years after the invasion of AD 43. London, like Rome, was founded on the point of the river where it was narrow enough to bridge and the strategic location of the city provided easy access to much of Europe.

What is the origin of the word London?

The origin of the name London is the subject matter of much debate but most historians agree that the name is a derivative of the word Londinium – the name of the port city established around 43 AD by the Romans. It is this ancient settlement that is believed to have grown into present-day London.

What is another name for London?

London, also known as Greater London, is one of nine regions of England and the top subdivision covering most of the city’s metropolis.

When did London start being called London?

around 43AD

The short story of London’s name goes like this: when the Romans invaded what was then a series of small kingdoms (Britain as we know it today didn’t yet exist), they founded a huge trading settlement on the banks of the Thames and called it Londinium, in around 43AD.

Did the Vikings Occupy London?

Viking attacks

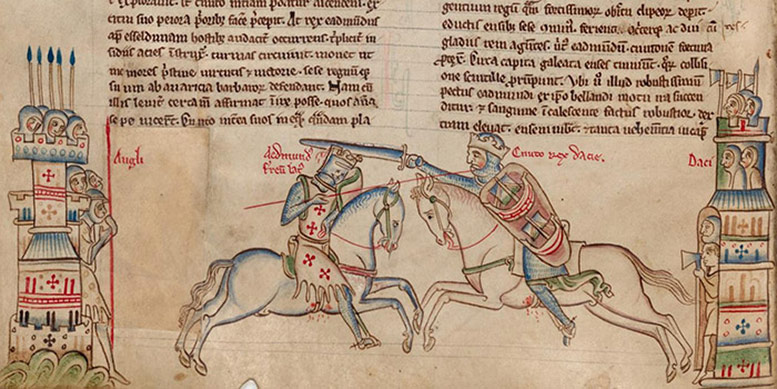

By the 9th century London was yet again a powerful and wealthy town attracting the attention of the Danish Vikings. They attacked London in AD 842, and again in AD 851, and The Great Army spent the winter in the town in AD 871-72.

Is Lunden a London?

London (Latin: Londinium; Old English: Lunden) is a city in southern England, and the current capital of the United Kingdom.

Did the Vikings sack London?

Disaster struck London in AD 842 when the Danish Vikings looted London. They returned in AD 851 and this time they burned a large part of the town. In 1871, King Alfred the Great became ruler of the southern kingdom of Wessex – the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom to at that time remain independent from the invading Danes.

Who first settled London?

the Roman armies

When was London founded? London’s founding can be traced to 43 CE, when the Roman armies began their occupation of Britain under Emperor Claudius. At a point just north of the marshy valley of the River Thames, where two low hills were sited, they established a settlement they called Londinium.

Why London is called the swinging city?

Swinging London is a catch-all term applied to the fashion and cultural scene which flourished in London, in the 1960s. It was a phenomenon which emphasized the young, the new and the modern. It was a period of optimism and hedonism, and a cultural revolution.

What is London known for?

What is London Most Famous For?

- Buckingham Palace.

- Big Ben and The Houses of Parliament.

- Natural History Museum.

- Covent Garden.

- Oxford Street.

- Borough Market.

- Take a river bus from Westminster to Tower Bridge.

- Spitalfields Market.

What is the nickname for England?

Nicknames for England

Old Blighty is an affectionate nickname for England that has its origins in the Boer War in Africa. The moniker became popular in Western Europe after World War I.

What did the Romans call England?

Britannia

Britannia (/brɪˈtæniə/) is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin Britannia was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great Britain, and the Roman province of Britain during the Roman Empire.

Is Vikings Valhalla a true story?

Is Vikings: Valhalla based on actual events? Yes, Vikings: Vallhalla is somewhat inspired by actual events that happened in history. Many of the characters and occurrences that take place in the well-written narrative are real.

Is London in Mercia?

During the 8th century the kingdom of Mercia extended its dominance over south-eastern England, initially through overlordship which at times developed into outright annexation. London seems to have come under direct Mercian control in the 730s.

Who defeated the Vikings in England?

King Alfred

King Alfred ruled from 871-899 and after many trials and tribulations (including the famous story of the burning of the cakes!) he defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Edington in 878. After the battle the Viking leader Guthrum converted to Christianity. In 886 Alfred took London from the Vikings and fortified it.

Is London part of Wessex?

The Danes were ousted from the city by Alfred the Great in 886, and Alfred made London a part of his kingdom of Wessex. In the years following the death of Alfred, however, the city fell once more into the hands of the Danes.

Are Danes Germanic?

The Danes were a North Germanic tribe inhabiting southern Scandinavia, including the area now comprising Denmark proper, and the Scanian provinces of modern-day southern Sweden, during the Nordic Iron Age and the Viking Age. They founded what became the Kingdom of Denmark.

Where is Wessex now?

Wessex, one of the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England, whose ruling dynasty eventually became kings of the whole country. In its permanent nucleus, its land approximated that of the modern counties of Hampshire, Dorset, Wiltshire, and Somerset.

Rudolf Meyer loves to travel. He’s been to all seven continents, and he has a particular interest in visiting the more remote and dangerous parts of the world. He’s an avid mountaineer, and has climbed some of the most challenging peaks on Earth. Rudolf is also a skilled outdoorsman, and can survive in almost any environment.

Aerial panoramic cityscape view of London and the River Thames, England, United Kingdom | © Engel Ching/Shuttertock

London has not always been London. Successive occupants have used their own phrases for the city. Some are mythical, some are historical and some are vaguely insulting.

Ancient names

People lived in the area we now call London long before the Romans arrived. For millennia, small tribes would have ranged across the land and fished in the Thames. Several prehistoric structures have been discovered. It’s possible to see 6,000-year-old timbers during very low tide at Vauxhall, for example. Yet no strong evidence of permanent settlement has ever been found.

With no settled population, perhaps the region had no name until the Romans founded the city around 43 AD. However, it’s unlikely that the Romans conjured their name of Londinium from nowhere. Some linguists suggest that they adapted an existing name, possibly Plowonida, from the pre-Celtic words plew and nejd, which together suggest a wide, flowing river (i.e. the Thames). This then became Lowonidonjon in Celtic times, and eventually Londinium. Another theory suggests a Celtic place name of Londinion, either derived from the name of a local chieftain, or the Celtic word lond (meaning ‘wild’). There is no consensus and, in the absence of written records, we will probably never know.

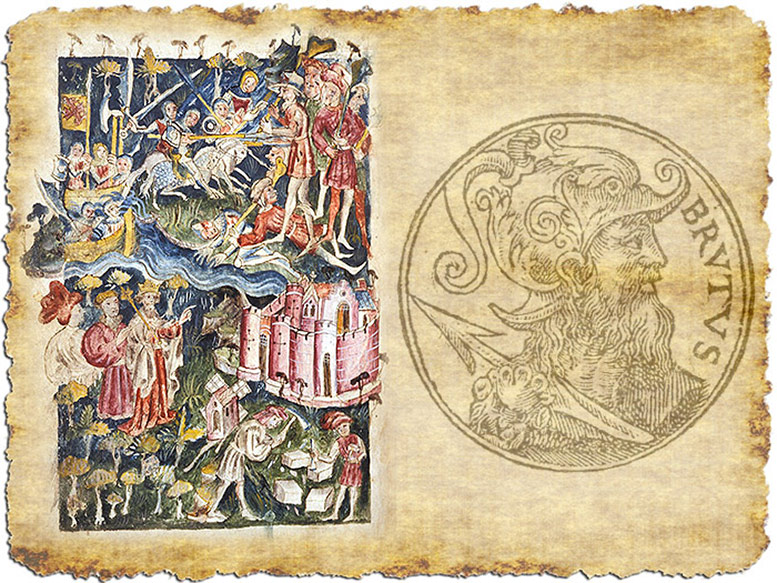

Mythical founding

12th century scholar Geoffrey of Monmouth played fast and loose with history, and is responsible for one of London’s best known origin myths. He tells us that the city was founded by Brutus, an exiled Trojan, who named his new stronghold Troia Nova (New Troy). Over time, according to Geoffrey, this became Trinovantum. There’s a whiff of non-fiction about this. The Trinovantes were one of the pre-eminent local tribes encountered by the Romans. Our medieval cleric was probably indulging in some creative wordplay, back-forming Trinovantes into Troia Nova and thence making up the whole Troy origin thing (or else repeating lost sources who did this). Geoffrey takes the story further. Trinovantum was at some point rebuilt by a pre-Roman figure called King Lud, who was eventually buried beneath Ludgate, and hence its name. Lud’s city was known as Caer-Lud (fortress of Lud), and later Kaer Llundain. This whole paragraph is firmly in the realms of myth, with no existing source other than Geoffrey. However, you can view a statue of King Lud and his sons outside St Dunstan-in-the-West, not far from the foot of Ludgate Hill.

Roman London

We now step back into verified historical territory. The Romans founded the first known settlement of any note in 43AD, and at some point soon after called it Londinium. The first written record comes from around 117AD, when Tacitus tells us «Londinium…though undistinguished by the name of a colonia, was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels.» Here, he’s writing about the city some 60 years before…around 15 years after its founding.

Other sources referring to the city by its Roman name are surprisingly rare, but include grammatical and syntactical variations such as Londinio, Londiniensi and Londiniensium. Around the year 368, the city was renamed Augusta, as shown on numerous coins from the era. It is thought that the name was predominantly used by officials, as a way of highlighting the city as an important imperial centre.

Anglo-Saxon London

Roman domination of London effectively ended in 410, when the legions were withdrawn to tackle some pressing domestic matters (Rome was being sacked). We know very little about London over the next two hundred years. The city inside the Roman walls was at some point abandoned. Germanic tribes, whom we now call Anglo-Saxons, took over the area and established a colony around Aldwych and Covent Garden. Sources from the 7th and 8th century name this port as Lundenwic, which means ‘London settlement or trading town’. In the year 886, Alfred the Great resettled the land inside the still-standing Roman walls, and shored up the defences. The rejuvenated stronghold was known as Lundenburh, meaning the fortified town of London. The old port area near Covent Garden was largely abandoned, and referred to as Ealdwic (‘old settlement’). We now know it as Aldwych.

London arises

The city slowly grew around Alfred’s City and the religious centre of Westminster. Following the Norman conquest, records begin to show the area referred to by its modern name, or similar versions such as Lundin, Londoun, Lunden and Londen. Over the centuries, the spelling settled down on London. However, the geographic definition of ‘London’ has changed over the years. Until recent centuries, places such as Westminster or Southwark would have been considered distinct from ‘London’, the name for the Square Mile within the old Roman walls. Even today, we refer to this area as The City of London, a city within a city. Boundary changes, such as the creation of the County of London, and Greater London are fascinating in their own right, but beyond the scope of this article.

Nicknames for London

As well as official names, the capital has also attracted a number of sobriquets over the years. Probably the most famous is The Big Smoke, The Old Smoke, or simply The Smoke. These names refer to the dense fogs and smogs that would permeate the city from ancient times. These were greatly exacerbated by the Industrial Revolution and the incredible growth of 19th century London, which created millions of new chimneys. The name was revived in the 1950s, when the city’s worst ever smogs claimed thousands of lives.

Another, less well known nickname for London is The Great Wen. A ‘wen’ is what today we’d call a sebaceous cyst. The phrase was coined in the 1820s by William Cobbett, who was comparing the rapidly growing city to a biological swelling. The phrase lives on in the name of an excellent London blog by journalist Peter Watts (who, incidentally, previously edited a much lamented section of Time Out called The Big Smoke).

Perhaps in an age dominated by rapid communications and time-poor typing, London will eventually be officially contracted to LDN, a name gaining traction in recent years on the back of other city abbreviations like NYC and LA.

Suggestions, Please!

As you can see, our city has enjoyed many names over the millennia. Yet, it’s been pretty stable for the past 900 years. Time for a change, we reckon. So please unleash your best suggestions — silly, serious, mildly offensive, whatever… — in the comments below. Perhaps we can effect a change for the 2000th anniversary of Londinium in 2043.

See also: How London’s boroughs got their names.

The city of London has one of the longest and richest histories in the modern world. Despite having continuous settlement for centuries, very little is known about the word’s origin. Many historians believe that the city’s current name comes from Londinium, a name that was given to the city when the Romans established it in 43 AD. The suffix «-inium» is thought to have been common among the Romans. Other names used included Londinio, Londiniesi, and Londiniensium. There is, however, heated debate on the reason why the Romans settled for them. The subject has led to the emergence of several theories that aim at solving the puzzle. A theory from William Camden suggested that the name was derived from “Lon” formerly «Llyn,» a Welsh word that translates to «grove» and «don» which was once «dun» meaning fort. His theory relies on links to the pre-roman Celtic occupation of Wales. Some scholars have also suggested that the word London could be a combination of the Celtic words Lin, which means «pool» and “dun,” which means «Fortress.» Those supporting the Celtic theories point to city names such as Dublin which is considered Celtic for dark pool and Lincoln which was initially known as Lindon in Celtic. The name changed to Lincoln after the fortress settlement as converted to a Colonia. Richard Coates argues that the original name was derived from the pre-Celtic name Plowonida, an Indo-European compound word. He argues that the name translated to swim river or boat river (Thames River). As the name of a place, it meant «the wide river area» where swimming and the use of a boat were the only means of crossing. According to his theory, the Celts that later occupied the area were unable to pronounce the “p” hence the river became known as Lownida while the settlement was called Lownedonjon. The settlement’s name was then converter to Londinium by the Romans. A theory from Geoffrey Monmouth, suggests that the word London relates to the etymology of Britain, which is derived from Brutus. He states that London was founded as the «New Troy» by the Trojan Aeneas who was the great-grandfather of Brutus. A tribe known as the Trinovantes later inherited the legacy. He suggests that the settlement which at one point called Trinovantum was rebuilt by King Lud. Lud later got buried under the Ludgate which is where it gets its name. The city’s name then became Caer-Lud which translates to the fortress of Lud and later evolved to Kaer Llundain and eventually London. Roman control over the city ended in 410. Germanic tribes called Anglo-Saxons later occupied the area. Alfred the Great settled in the ancient Roman city and enhanced its defenses in 886. The settlement got renamed to Lundenburh which translated to fortified London. The city gradually grew around the site and, Westminster, which was the religious center. Names like Lunden, Lundin, Londoun, and Londen began to emerge after the Norman Conquest. Centuries later the name changed to London. Today London serves as the capital of England and the UK as well as the country’s leading financial hub. Celtic Theories

Pre-Celtic Theories

Mythical Theories

Post-Roman Domination and Modern London

Continue Learning about History

What was the roman name for the city of London in England?

The name of Roman London was Londinium.

How did London got its name?

How did London get its name?From the Roman Londinium.

What year was London built as a roman city?

The Roman name for London is Londinium

Why was London named London?

London was named after its Roman name — Londinium

Was London called londinium in the middle ages?

No. Londinium was the Roman name but by the Middle Ages it was

called London.

London, the capital city of England and the United Kingdom, is one of the most visited cities in the world. A city steeped in culture, London boasts of a history dating back many centuries. The origin of the name London is the subject matter of much debate but most historians agree that the name is a derivative of the word Londinium – the name of the port city established around 43 AD by the Romans. It is this ancient settlement that is believed to have grown into present-day London.

London’s Original Name

The debate starts with the fact that Londinium itself was referred to by other names such as Londiniensi, Londiniensium, and Londinio. This in itself should not be much of a worry given the similarity in the names. The real differences start when we wonder why the Romans decided to call their settlement on the Thames Londinium.

The Celts who lived in the region before the Roman invasion probably referred to it as Llan Dian. This literally means Temple of Diana and could have been a reference to the system of Dianic worship practiced here. The name could also have been derived from the Welsh words Llyn Dain meaning a Fort by a Pool (of the River Thames) or even from Glynn Din meaning Valley City.

Going further back in history, experts suggest that the Celts may have themselves been influenced by pre-Celtic tribes that inhabited the region, in the matter of London’s nomenclature. It looks possible that the region was called Plowonida. This comes from the words plew and need from the Pre-Celtic languages spoken in these parts. Plowonida suggests a wide basin of a flowing river and could have been a reference to the Thames. The Celtic language does not assimilate the “P” sound of most pre-Celtic words and this could have been the source of the Celtic name for London.

Another account of the name London was put forth by the controversial 12th-century writer Geoffrey of Monmouth. In his ‘The History of the Kings of Britain’ (Historia Regum Britanniae) Geoffrey says that King Lud (the brother of Cassivellaunus, contemporary of Julius Caesar) seized control of the ancient city of Trinovatum and renamed it Kaerlud, or Lud’s City. Thereafter, Kaerlud became Kaerlundein, and eventually London. Geoffrey’s works, however, are so full of fantasy, that it is quite impossible to glean historic facts from them.

There are numerous other theories, each more fanciful than the other about the origins of London’s name. These make a good read but in the absence of written records, each is difficult to prove.

Related Maps:

London city did not acquire its name overnight. Throughout the centuries, from one civilisation to another, its name has changed to become what it is now. Prehistoric structures, dating back to 6000 BC are found around the Thames river valley, suggesting human habitation in the area. There isn’t enough evidence to confirm whether the area was given a name at all during those times.

The original name of London city, therefore, should be traced back to 43 AD, during the Roman occupation of the land. The Roman’s called the area “Londinium”. It appears in ‘ Tacitus’s’ records in 117 AD, where he states: “Some merchants and trading vessels much frequented Londinium”.

Some suggest that the Romans adopted the name from the pre-Celtic name “Plowonida”, which is a combination of the words ‘nejd’ (flowing river) and ‘plew’ (wide), referring to the river Thames. It then changed with time to “Lowonidonjon” and was eventually referred to as “Londinium”. Others suggest that it derived from the name of a Celtic chieftain called: “Londinion” or from the Celtic word for ‘wild’: ‘Lond’. Some other sources present variations of the name, such as Londiniensi, Londinio and Londiniensium.

Following the Roman withdrawal from London in 410 AD, the Anglo-Saxons conquered the land and built settlements around ‘Covent Garden’ and ‘Aldwych’. They referred to that area as “Lundenwic “, meaning ‘trading town’ or ‘London settlement’. ‘Alfred the Great’ moved inland and claimed the previous Roman settlements, naming the city “Lundenburh”, which means ‘fortified London town’. The city slowly began to expand around Alfred’s stronghold.

During the Norman conquest of the lands, the city name began to take a similar form to its present day name, appearing in texts as ” Lundin, Londoun and Lunden”, until eventually, a reference was made to the name “London”. In geographical terms, ‘Lunden’ did not have its current boundaries. It is by passing the stages of ‘County of London’, ‘Greater London’, etc. over the years that London city eventually acquired its name.

A rather mythical reference is also available to the origin of the name ‘London,’ made by a 12th-century scholar called ‘Geoffrey of Monmouth’. His historical accounts, though based on facts, were without much credence. Thus, his tale of London’s founding became a myth. According to it, London city was founded by an exiled Trojan by the name of “Brutus”. He gave the land the title: ‘Troia Nova’, which translates into ‘New Troy’. When a pre-Roman ruler, ‘King Lud’, took the throne, he named the city “Caer-Lud” which evolved to “Kaer Llundain” from which today’s “London” was derived.

London city names have also expanded to include a few nicknames. ‘The Big Smoke’, ‘The Smoke’ and ‘The Old Smoke’ are some of the most famous sobriquets used for London, created about the thick fogs and smoke which flooded the city from time to time following the industrial revolution. ‘The Great Wen’ is another lesser known nickname for London city.

Londinium, modern day London was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50. It sat at a key crossing point over the River Thames which turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century.

Following the foundation of the town in the mid-1st century, early Londinium occupied the relatively small area of 1.4 km2, roughly half the area of the modern City of London and equivalent to the size of present-day Hyde Park. In the year 60 or 61, the rebellion of the Iceni under Boudica compelled the Roman forces to abandon the settlement, which was then razed. Following the defeat of Boudica by the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus a military installation was established and the city was rebuilt. It had probably largely recovered within about a decade. During the later decades of the 1st century, Londinium expanded rapidly, becoming Britannia’s largest city, and it was provided with large public buildings such as a forum and amphitheatre. By the turn of the century, Londinium had grown to perhaps 30,000 or 60,000 people, almost certainly replacing Camulodunum (Colchester) as the provincial capital, and by the mid-2nd century Londinium was at its height. Its forum-basilica was one of the largest structures north of the Alps when the Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122. Excavations have discovered evidence of a major fire that destroyed much of the city shortly thereafter, but the city was again rebuilt. By the second half of the 2nd century, Londinium appears to have shrunk in both size and population.

Although Londinium remained important for the rest of the Roman period, no further expansion resulted. Londinium supported a smaller but stable settlement population as archaeologists have found that much of the city after this date was covered in dark earth—the by-product of urban household waste, manure, ceramic tile, and non-farm debris of settlement occupation, which accumulated relatively undisturbed for centuries. Some time between 190 and 225, the Romans built a defensive wall around the landward side of the city. The London Wall survived for another 1,600 years and broadly defined the perimeter of the old City of London.

Classical References to Londinium

The standard second century geographical reference work by Claudius Ptolemaeus, mentions both the town of Londinium (vide infra) and the Tamesa Aestuarium (the Thames Estuary), on the upper reaches of which the settlement was located.

Next to these,¹ but farther eastward, are the Canti² among whom are the towns: Londinium 20*00 54? Darvernum 21*00 54? Rutupie 21*45 54?.³

- The Atrebates tribe of Hampshire and Berkshire.

- The Cantiaci tribe inhabited Cantium (Kent). This is curious, for London is generally thought to have been located in the territories of the Catuvellauni.

- These three towns are, respectively; London, Canterbury, and Richborough, the latter two being in Kent.

The work which best describes the location of Londinium is the Antonine Itinerary, an official imperial document of the late-second century which listed many of the major road routes of the Roman empire, fifteen of them in Britain, over half of which mention Londinium.

Location:: 12 miles from Sulloniacis (Brockley Hill, Greater London) 10 miles from Noviomago (Crayford, Greater London)

Route: From London to Dover (Kent)

Location:: 27 miles from Durobrivis (Rochester, Kent)

Route: From London to Lympne (Kent)

Location:: 27 miles from Durobrivis (Rochester, Kent)

Iter: V

Route: From London to Carlisle (Cumbria) on the Wall

Location:: 28 miles from Caesaromago (Chelmsford, Essex)

Route: From London to Lincoln

Location:: 21 miles from Verolami (St. Alban’s, Hertfordshire)

Route: From Chichester (West Sussex) to London

Location:: 22 miles from Pontibus (Staines, Surrey)

Route: From York to London

Location:: 21 miles from Verolamo (St. Alban’s, Hertfordshire)

Location:: 15 miles from Durolito(Romford, Greater London)

Part XI – The Count of the Sacred Bounties

Under the control of the illustrious count of the sacred bounties: … The accountant of the general tax of the Britains. Provosts of the storehouses: … In the Britains: The provost of the storehouses at London. … Procurators of the weaving-houses: … The procurator of the weaving-house at Winchester in Britain. …”

London also appears in the Ravenna Cosmology of the seventh century as Londinium Augusti (R&C#97), which appears between the entries for Verulamium (St. Albans, Hertfordshire) and Caesaromagus ( Chelmsford, Essex).

Epigraphic Evidence from London

There are thirty-nine Latin inscriptions on stone recorded in the R.I.B. for London, about a fifth of which are fragmentary or otherwise illegible. A selection of the more interesting inscriptions are presented on this page, under several categories; the Roman military presence in London, the gods and religious institutions, also military and civilian tombstones.

The Claudian Encampment

A length of an early camp ditch was found at Fenchurch Street (Britannia 18 (1987) p.333; Brit. 20 (1989) pp.305-6) and Duke’s Place (Brit. 4 (1973) p.306), evidence suggests that the ditch was filled-in soon after it was dug. There is room on the east hill for a camp of no more than c.75 acres (30.5ha), which is slightly more than half the size of the enclosure at Richborough. Because of this, it has been suggested that another large camp was erected near the Westminster Crossing, probably somewhere near Hyde Park.

The Roman Military

The only type of Roman military unit attested on stone at London are those of the Legions, even though it is generally thought that an auxiliary unit was stationed here nothing ‘concrete’ has been turned up. Three of Britain’s legions are represented at London, The Second Augusta is attested on an altar dedicated to the god Mithras and on two tombstones of former soldiers from the legion (respectively, RIB 3, 17 & 19), one of them dated to the first quarter of the third century, the Twentieth Legion is represented by another two tombstones (RIB 13 & 18), and the Victorious Sixth is mentioned only on a single funerary inscription (RIB 11). All of these Latin texts are detailed and translated separately below.

Legio Secundae Augusta – The Second Augustan Legion

RIB 17 — Funerary inscription for Vivius Marcianus

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

To the spirits of the departed and to Vivius Marcianus, centurion of the Second Legion Augusta, Januaria Martina his most devoted wife set up this memorial.

D M

VIVIO MARCI

ANO 𐆛 ❦ LEG II

AVG IANVARIA

MARTINA CONIVNX

PIENTISSIMA POSV

IT MEMORIAM

RIB 19 — Funerary inscription for Celsus

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

To the spirits of the departed: […]r Celsus, son of Lucius, of the Claudian voting-tribe, [from …], speculator of the Second Legion Augusta An[to]nius Dardanus Cu[rsor], [Val]erius Pudens, and […]s Probus, speculatores of the legion (set this up).

[…]BVS

[4]R L F C[…] CELSV[…]

[4 ]PEC LEG [… ]VG AṆ

[…]N DARDANVS CV[…]

[…]ERIVS PVDENS

[4]S PROBVS SP[…]C L[…]

Legio Sextae Victrix – The Sixth Victorious Legion

RIB 11 — Funerary inscription for Flavius Agricola

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

To the spirits of the departed: Flavius Agricola, soldier of the Sixth Legion Victrix, lived 42 years, 10 days Albia Faustina had this made for her peerless husband.

D M

FL AGRICOLA MIL

LEG VI VICT V AN

XLII D X ALBIA

FAVSTINA CONIVGI

INCONPARABILI

F C

Legio Vicesimae Valeria Victrix – The Twentieth Legion, Valiant and Victorius

RIB 13 — Funerary inscription for Julius Valens

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

To the spirits of the departed Julius Valens, soldier of the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, aged 40, lies here, his heir Flavius Attius having the matter in charge.

D M

IVL VALENS

MIL LEG XX V V

AN XL H S E C A FLAVIO

ATTIO HER

The Gods of Roman London

The Temple of Mithras

RIB 3 — Dedication to Mithras

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

Ulpius Silvanus, emeritus of the Second Legion Augusta, paid his vow enlisted at Orange.

VLPI

VS

SILVA

NVS

FAC

TVS

ARAV

SIONE

EMERI

TVS LEG

II AVG

VOTVM

SOLVIT

The Temple of Isis

A temple to the great Egyptian goddess Isis was tantalizingly suggested by the discovery of an earthenware jug at Southwark on the opposite side of the Thames from the Londinium settlement, close to the line of the Watling Street through Cantium. This object was inscribed with the words LONDINI AD FANVM ISIDIS or “From London at the temple of Isis“, and has been dated to the latter half of the second century. It was not until the mid-1970’s that a Roman altarstone dedicated to the goddess was finally discovered (vide RIB 39b infra).

Possible Apsidal Temple

Aside from the famous temple of Mithras and the suspected temples of Isis and Camulos Mars detailed above, a possible temple is thought to have lain beneath the south-west corner of the 2nd-century forum/basilica, and obviously predated these monumental public buildings. The building is rectangular, measuring about 60 ft. by 34 ft. (c.18.3 x 10.4), with a squarish apse at its northern end. The walls of the building were an almost-uniform 3 ft. thick throughout, including a dividing wall which bisected the building into two, a squat rectangular room to the south had an entrance in its east side, and a portal in the partition wall led through to a square room at the north end with a projecting apse. This building is thought to be an apsidal shrine to some unknown deity.

Civilian and Military Tombstones

Of the five inscriptions shown in the table above, RIB 16 is a scarcophagus, RIB 22 is a base of some sort, RIB 10 is undefined and the other two are tombstones.

The History of Roman London

The settlement of Londinium was established shortly after the Claudian invasion in the summer of 43AD. The first Roman building was an Auxiliary Fort, built on the north bank of the Thames to the east of the Walbrook on the instructions of the military governor Aulus Plautius. The fort was established to guard the northern end of a wooden bridge which had been rapidly built across the Thames between Southwark and the north bank, also to secure the western flank during the Roman push eastwards against the British capital at Camulodunum (Colchester, Essex).

A civilian settlement comprised of the soldiers dependents, assorted native tradesmen and foreign merchants soon developed to the east of the Walbrook outside the defences of the fort, which was itself demolished after only a short period of use, probably before the 50AD’s, as the Roman military campaigns were extended into the Midlands and Wales. Though unprotected, the settlement had become well established as an important provincial town by the time the Iceni and the Trinovantes tribes rose in revolt in the winter of 60/61AD and destroyed the colony at Colchester, fifty miles from London. At the time, the governor Suetonius Paulinus was campaigning on the Isle of Anglesey, over two-hundred miles away.

London Razed During the Boudiccan Revolt

Suetonius, however, with wonderful resolution, marched amidst a hostile population to Londinium, which, though undistinguished by the name of a colony, was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels.

Upon hearing of the uprising to his rear, the Roman legate immediately gathered together all the legionary and auxiliary forces as he could possibly spare from the Midlands and Wales, then marched south-east to counter the rebel force. Despite his swift response, he was unable to stop the ravaging horde from falling upon defenceless London. The revolting natives razed the entire town to the ground. All who did not flee were massacred, their severed heads thown into the Walbrook stream. Chaos reigned throughout the South-East. Suetonius was forced to retreat back along the Watling Street, surrendering also the thriving town of Verulamium to the rebels as he fled north-west into the Midlands. Here however, as the unruly revolutionaries were delighting in rapine and destruction, he was able to concentrate his forces and a short time afterwards engineered a crushing defeat on the combined British army outside Manduessedum (Mancetter, Warwickshire).

Following the revolt, the province of Britain was very nearly surrendered by Rome, but the emperor Nero was turned from this course of action by the arguments of his advisor and former tutor Seneca, who had invested a lot of money in Britain and would have suffered financially if Rome were not to retain the island. As a result of Seneca’s persuasive arguments, Julius Classicanus was appointed to the post of procurator of Britain. This was a non-military position whose main role was to restore economic order in the war-torn province. Classicianus was to succeed in his appointment but died in late 61AD, his body cremated and his ashes placed in a small tomb along with containers of food outside the Roman town boundary at Tower Hill, where the fragments of his tomb were later discovered (vide RIB 12 infra).

RIB 12 — Funerary inscription for Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus

- Translation

- Latin

- Commentary

To the spirits of the departed (and) of Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus, son of Gaius, of the Fabian voting-tribe, … procurator of the province of Britain Julia Pacata I[ndiana], daughter of Indus, his wife, had this built.

DIS

[…]ANIBVS

[… ]AB ALPINI CLASSICIANI

[…]

[…]

PRO PROVINC BRITA[…]

IVLIA INDI FILIA PACATA I[…]

VXOR […]

The Aftermath of the Revolt

Following the revolt, during the last quarter of the first century, Londinium was rebuilt, spreading west to the hill across the Walbrook, and soon became transformed into a Roman city. The first forum and basilica, which included a small temple, was constructed out of timber in the Bank area, while two public baths were built on the west hill at Cheapside and Trinity Lane. Remodelling and refinement of these bathhouses continued into the late second century. The palace of the provincial governor was built c.80-100AD on the north bank of the Thames, just east of the Walbrook. Evidence of gold smelting was found beneath the Palace area. The original basilica and forum were replaced in the late-first/early-second century by more substantial stone buildings, wooden wharves were constructed on the north bank of the Thames, and the town soon became the centre of both provincial government and trade.

The Hadrianic Fort

A large Fort was constructed sometime between 100AD and 120AD, possibly in preparation for Hadrians visit to Britain in 122AD. It was seemingly built into a grid of city streets already in existance which covered an area of around 330 acres. The fort measured about 750 x 705 feet (c.230 x 215 m) and its four-feet thick ragstone walls backed by an earthen rampart enclosed an area of around 12¼ acres (c.5 ha), sufficient to hold three or four legionary cohorts, between one-and-a-half to two-thousand soldiers. The Romans evidently thought London of such importance that they were willing to garisson ten percent of its British legionary forces here.

Shortly after the fort was built, perhaps around 125-30AD, part of the city was destroyed by fire. The conflagration was probably accidental for there is no evidence to support the theory that the damage was the result of an attack. Whatever the cause, it would seem that a number of large public works were undertaken to restore the fire-damaged sectors of the city.

Evidence for the Provincial Capital

By the early second century London had become the recognised capital of the Roman province of Britannia.

A wooden writing tablet has been found near the Walbrook, branded with a circular stamp which bears the words: BRIT PROV – DEDERVNT PROC AVG “The province of Britain – Issued by the imperial procurator”.

Roofing tiles: P.PR.BR.LON “The provincial procurator of Britain, at Londinium“.

A Sinking in the Thames

During the late second century Britain began to suffer attacks from hostile Picts, Scots and Saxons. These attacks rapidly increased in frequency and destruction, and would naturally have caused some concern in Londinium. Around this same period a boat containing a cargo of ragstone sank in the River Thames in the vicinity of Blackfriars. There is nothing to suggest that the sinking was anything more than an accident, but the same lack of evidence means that the possibility of the boat being involved in some sort of altercation with Saxon pirates also cannot be disproved.

City Defences Started

Around the turn of the third century the city defences were begun. The entire town was enclosed on it’s landward sides by a large ditch backed by a twenty-foot (six metre) high rampart wall which consisted of a ragstone facing with a rubble infill, bonded by several courses of flat bricks. Part of the defensive circuit of the existing Hadrianic fort was incorporated into the north-western perimeter of these city defences. Some parts of the wall itself can still be seen between the tall office buildings in the Bank area. In the mid-fourth century the remaining riverside wall was built, completely enclosing the city. Bastions were also added to the existing landward walls at this time.

London in the Fourth Century Based on the plan by R. Merrifield and the DUA, Museum of London.

The city wall was pierced by five large gates, through which superbly constructed roads reached out, arrow-straight through the surrounding countryside, linking Londinium with several nearby towns and beyond them, across the entire province. Surviving portions of these roads have been recorded during building work throughout modern times and their destinations are well known, but unfortunately none of the structures of the gates themeselves have survived. The locations of all the gates, however, have been preserved in the names of districts within the City of London; from Aldgate the road ran north-east to Camulodunum (Colchester, Essex), from Bishopsgate the road led north to Durovigutum (Godmanchester, Cambridgeshire), from Aldersgate the Watling Street ran north-west towards Verulamium (St. Albans, Hertfordshire), and the two roads from Newgate and Ludgate converged outside the city perimeter and ran westwards to Silchester (Calleva Attrebatum). London lay at the very hub of the Roman road system in Britain.

The late-third century saw the Roman empire torn apart by the struggles of several rebel generals who each claimed for themselves the right to be emperor. Emperor Constantinus Chlorus saved Londinium from rebels in 296AD, and after a century of upheaval, during which London suffered many attacks from Saxon raiders, in 410AD emperor Honorius refused British cities help in defending against invading forces, and Londinium was gradually abandoned.

References for Londinivm Avgvsta

- Chapter 3 of The Towns of Roman Britain by John Wacher (2nd Ed., BCA, London, 1995);

- Temples in Roman Britain by M.J.T. Lewis (Cambridge 1966);

- The Roman Inscriptions of Britain by R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright (Oxford 1965).

Map References for Londinivm Avgvsta

NGRef: TQ3281 OSMap: LR176/177; Londinium.

Roman Roads near Londinivm Avgvsta

Ermine Street: N (28) to Bravghing Stane Street: SSW (14) to Ewell (Surrey) NE (32) to Great Dvnmow (Essex) River Stort Downstream: N (23) to Harlow S (44) to Hassocks (West Sussex) Iter II/Watling Street: NW (11) to Svlloniacis ENE (14) to

Durolitum(Harold Wood, Romford, Greater London) W (18) to Pontes (Staines, Surrey) Watling Street: ESE (13) to Noviomagvs Cantiacorvm (Crayford, Greater London) SSW (17) to Titsey (Surrey) River Stort Downstream: N (23) to Old Harlow

Study the past if you would define the future – Confucius

When you think of London, you might think of the booming metropolis it is today, the magnificent sights, the gorgeous places to dine and its lush inner-city green spaces. However, London is one of the oldest cities on earth and is shrouded in mystery and legend. Here we will briefly summarise London’s history and the historical events which occurred in this marvellous place. So let’s delve into this ancient pool of London history knowledge and discover the hidden facets to such an esteemed and popular city.

Covering the entire history of London is an arduous task indeed, which requires much research and lots of writing, but we aim to cover a brief history of London and many major events that have taken place in this amazing city in a nutshell.

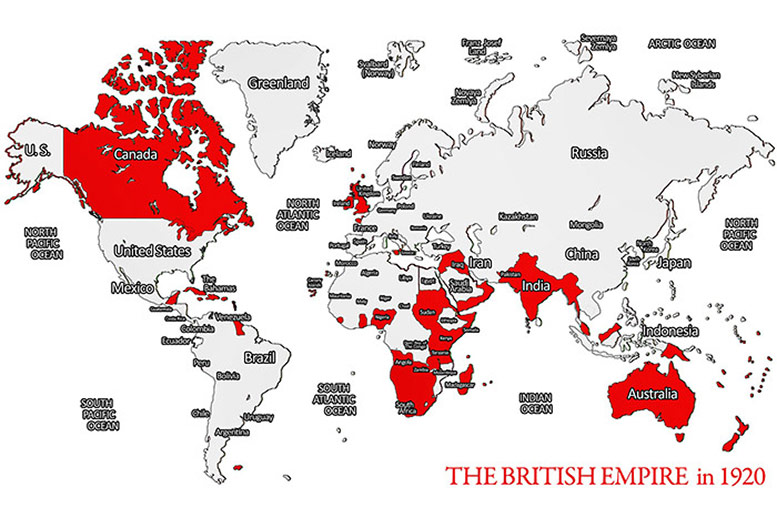

Since London is the capital, it will become apparent that it plays a major role in most events in the history of the entire country and even around the world, so discussing political decisions and events in faraway places isn’t really a digression from the topic, as the decisions came from the ultimate seat of power in England: London.

London’s Legendary Beginnings

Although it is widely known that London was originally built by the Romans, legend dictates that the city was founded on the banks of the River Thames by Brutus of Troy after he defeated Gog Magog; ancient giants who were residents on the island in around 1000 BCE. He called the city New Troy (Caer Troia or Troia Nova) but the name soon changed to Trinovantum, and the tribe that existed around the River Thames in the Iron Age were the Trinovantes.

Legend has it that Britain was named after Brutus of Troy who became it’s first King. He ruled for twenty-four years and after his death, the island was split between his three sons; Locrinus, who took over England, Albanactus; who took over Scotland and Camber; who took over Wales.

Roman London (43 – 410 AD)

The Roman conquest of Britain, which began in 43 AD, took a while and many battles were fought by the Roman legions against the native Celtic tribes. In 47 AD the small civilian town of Londinium was built by the Romans and was very small, equivalent to the size of Hyde Park today.

Londinium was destroyed in 60 AD following a revolt led by Queen Boudicca and her tribe, the Iceni, but was then rebuilt after her defeat and death. She was said to have poisoned herself before losing the battle to avoid being captured. The town then rapidly grew under Roman administration, there were approximately 60,000 inhabitants and IT became the capital of Britannia replacing Colchester.

The Romans improved infrastructure in the town and built bathhouses and temples, Londinium even had its own amphitheater and basilica, a building where the Romans held court meetings. The garrison of Londinium was stationed in a large fort making it a highly tenable position should the natives try to ransack it again.

The Romans then built the London Wall at sometime around 180 – 225 AD which survived for 1,600 years; they clearly didn’t want to repeat the disaster caused by Boudicca. In the 3rd century, Londinium was raided several times by Saxon pirates resulting in the Romans building even more defensive structures including a riverside wall.

The 5th century saw the decline of the Roman Empire as a whole, this led to Britannia being abandoned by the Romans and Londinium became derelict as it was considered as a far-flung place and not worth spending resources and military power on when there were much greater problems closer to Rome itself.

Anglo-Saxon London (5th century — 1066)

When the Romans left Britannia, settlers from Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands arrived in search of a new homeland; these people formed the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. The Heptarchy consisted of seven kingdoms: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. The Anglo-Saxon settlement located close to the former town of Londinium was called Lundenwic and was disputed between the kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex in 796. Archaeologists actually found it hard to find where Anglo-Saxon London was really located, recent discoveries, such as the cemetery in Covent Garden, shows that it was much closer to modern London than they originally thought, perhaps even in the same boundaries but smaller in size of course. The area surrounding the River Thames is a strategic location so it is of no surprise that it didn’t stay abandoned for long after the Romans left and it became a trading hot spot.

In 871 the Great Heathen Army of the Vikings invaded, they overran most of England and reached Lundenwic, camping at the site where the old Roman wall was, the majority of the population then moved to the former Londinium and formed a new settlement called Lundenburg. Winchester was the capital of England until Æthelred the Unready made London his capital in 978. The Anglo-Saxon King, Alfred the Great took control of Lundenburg and renewed its fortifications, this was useful because in 996, Sweyn Forkbeard, the King of Denmark, attacked the city but was defeated. Lundenwic was mostly abandoned and renamed Ealdwic, today it is called Aldwych.

In 1016 however, Sweyn Forkbeard’s son, Cnut the Great conquered Lundenburg and the rest of England. Cnut’s stepson, the famed Edward the Confessor became the King in 1042 and built Westminster Abbey and the first Palace of Westminster which is now known as the Houses of Parliament. When Edward the Confessor died in 1066, Duke William of Normandy claimed the English throne but Edwards’s brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson was crowned King of the Anglo-Saxons thus provoking William to invade.

Norman and Medieval London (1066 — 15th century)

William of Normandy defeated Harold Godwinson at the battle of Hastings in 1066 and became King of England, he then became known as William the Conqueror. In order to subdue London’s population, William built a number of forts, the most famous of these survives today and is the Tower of London, it was the first stone castle in England.

1097 saw the construction of the Westminster Hall by William Rufus, William the conqueror’s son. The only bridge to cross the River Thames until 1739 was the London Bridge construction began in 1176 and it was completed in 1209.

In 1216, Louis of France was crowned King of England during the First Barons’ War when the rebel forces pledged allegiance to him against King John. When John died, however, the rebels began to support his son Henry III and Louis withdrew from England. During these years there were several violent acts committed against London’s Jewish population and ended with them being exiled from the city by Edward I in 1290.

Despite strong cultural and linguistic influences, the development of early modern English allowed the population to form a separate culture that would eventually set the English culture apart from French culture in the coming medieval period. Due to the increase of trade in the Middle Ages, London rapidly grew as due to its location on the River Thames being ideal for commerce.

The population of London grew rapidly, in 1100, there were around 15,000 people living in the city but by 1300, it had grown to roughly 80,000 inhabitants. In London, trade was administered by guilds that managed the city as they were also the ones who elected the Lord Mayor of the City of London.

Norman London was a very different place from modern London, most of the buildings were made from timber or straw and the streets were very narrow, this combination made it extremely vulnerable to fires which were deadly and if not put out could potentially destroy the whole city.

The Knights Templar, who played a part in the Crusades, actually had their base in London from 1185 up until their dissolution in 1312 after they were charged with devil-worshipping. There are a few buildings, located in Temple, which can be visited today such as Middle Temple Hall, Inner Temple Hall, Temple Church and a few dormitories. The Middle Temple and Inner Temple Inns of Court are also based here (all barristers have to belong to one of the four Inns of Court; two of them are former Knights Templar buildings).

During the 14th century, London lost more than half of its population due to the Black Death, a plague that was carried by fleas living on rats that came from trading ships. Despite this, London’s economy made a swift recovery and was soon operating as normal.

In 1475, a merchant guild from Central Europe known as the Hanseatic League set up its base in London known as the Steelyard; it was from here that woolen cloth was shipped to the Netherlands where it was much sought after ultimately boosting London’s economy.

Tudor London (1485 — 1603)

In 1485, Henry Tudor became King of England as Henry VII; he also put an end to the bloody Wars of the Roses by marrying Elizabeth of York (the Wars of the Roses were fought between the House of Lancaster, whose emblem was a red rose, and the House of York, their emblem being a white rose; they were civil wars for the English throne). This marked the beginning of the Tudor period.

When the second Tudor monarch, Henry VIII, came to power in 1491, there were some major changes in London as well as England as a whole through the significant event known as the English Reformation.

London nearly came under attack in 1497 when Perkin Warbeck, a pretender to the throne, camped outside the city with his band of followers. The King took swift action however, and Warbeck was caught and hung.

In 1515, Hampton Court Palace was built by the order of King Henry VIII for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was a personal favourite of the King at the time.

The English Reformation is the name given to the changes and events that took place in the country after the Church of England broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and the authority of the Pope. It is often believed that Henry VIII was provoked to make these changes after Pope Clement VII decided not to allow his annulment with Catherine of Aragon in 1534. Henry VIII then declared himself “Supreme Head on Earth of the Church of England” and the country then became largely Protestant. (An interesting point to note is that even though Henry VIII annulled his marriage to Catherine to marry Anne Boleyn, when Anne couldn’t give him a son, he had her beheaded after just three years!)

More than half of the properties in London at the time were monasteries and nunneries, and over a third of the inhabitants were monks and nuns; the Reformation affected them terribly as all these properties were seized by the King and other nobles. This was known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries and even once-powerful individuals, like Thomas Wolsey, (as he was a cardinal of the Catholic Church) had their houses seized and converted into whatever their new owners saw fit; Henry VIII converted the lands surrounding Westminster Abbey, Hyde Park and St. James’s Park all into deer parks for his personal entertainment. St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which is still there today, was reopened by the King as it had been operating without that name and without pay during the Dissolution.

When Henry VIII died in 1547, most of the seized buildings that were left empty were handed over to the City Livery Companies to make up for crown debts by his son Edward VI. The City Livery Companies were a collection of guilds and trade associations that used some of the newly gained property in ways that were helpful to the public; the former St. Thomas’ monastery was converted into St. Thomas’ Hospital and Bridewell Palace was converted into a children’s home.

In 1553, Edward VI died and Mary I became queen. In between Edwards’s death and Mary coming to the throne, Lady Jane Grey reigned for just nine days but was removed by Mary who had her beheaded. When Mary decided to marry Philip II of Spain, there was an uprising led by Sir Thomas Wyatt who took control of Southwark, he then moved through Charing Cross, Westminster and then reached Ludgate, however his lack of supporters in the City of London, forced him to surrender in 1554. Mary I tried to reverse the Reformation and executed Protestants by burning them at the stake and for this, she was known as “Bloody Mary”. She returned England to Roman Catholicism, a process that just added more chaos to the discord caused by the English Reformation.

In 1558, Elizabeth I, who was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, became the queen and brought the country into what historians like to call the golden age of English history and the peak of the English Renaissance. She was the last of the five Tudor monarchs.

Queen Elizabeth loved watching plays and many theatres were built during her reign, her advisors feared however, that the crowds that the theatres attracted could turn in to mobs so most of them were built in the city boundaries. Theatres built in London during the Elizabethan era include The Globe, The Rose, The Swan, The Hope, The Blackfriars Theatre, The Theatre and The Curtain. It was at this time, during the 16th century, that William Shakespeare lived and worked in London. It was these forms of entertainment that had a massive impact on English culture.

William Shakespeare is regarded as the national poet of England, and is one of the most famous playwrights and poets in the world; his works are studied in English schools and Universities. The Globe Theatre, which is located in the London Borough of Southwark, was built by Shakespeare’s playing company known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in 1599. The Globe Theatre was actually destroyed by fire in 1613 but was rebuilt on the same site in 1614. (The Globe is still there today and can be visited).

Elizabethan London was a lot different from modern London, although it was much more built-up than previous eras, there were still some surprising contrasts; Covent Garden was a market garden, Islington and Hoxton were just villages and areas like Holborn and Bloomsbury had hospitals built there due to the fine country air.

Earthquakes in England are rare but in 1580 there was one known as the Dover Straits Earthquake, which affected France, England and all the way up to Scotland. In London, many chimney stacks and parts of Westminster Abbey were destroyed; falling stones also killed two children. The Puritans, who were a group of Protestants, blamed the emergence of theatres for the earthquake as they were opposed to it all along declaring them “the work of the devil”.

The Tudor period saw London expand into a large trading city, one of the most important in Europe; trade from London went all the way to the Americas, Russia and the Levant (modern day Syria, Palestine and surrounding areas).

Stuart London (1603 — 1714)

After the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, James I became King of England starting the Stuart period, James I was already the King of Scotland, as James VI, before becoming the King of both countries after the Union of the Crowns which put England, Ireland and Scotland under the ownership of a single monarch.

In 1605, the famous Gunpowder Plot took place where a Catholic group led by Robert Catesby, including the notorious Guy Fawkes, attempted to blow up the House of Lords. The plan failed as it was discovered by the King and the conspirators were executed; this event is remembered by celebrating Bonfire Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Night, on the 5th of November every year where people set off of fireworks and light bonfires.

During James’ reign, the Lord Mayor’s Show was brought back in 1609, and is still implemented today, to celebrate the appointment of a new mayor of London; it is an annual event with a new mayor being chosen every year.

In 1611, a businessman named Thomas Sutton had purchased the dissolved monastery of the Charterhouse and it was converted into a hospital, chapel and medical school.

When Charles I came to power in 1625, many rich people and aristocrats began to buy properties in the West End of London; due to the rich social life in the rapidly growing city, it became a place where some people, who could afford it, spent a part of the year in London.

London also played a part in the English Civil War of 1642, which lasted until 1651, fought between the Parliamentarians who didn’t support the King and the Royalists who did (the belligerents are also known as the “Roundheads” and “Cavaliers”).

The Battle of Brentford in 1642 was fought a few miles away from London and many defenses and bastions were built in the areas of Westminster and Southwark, deterring attacks from the Royalists. It was the extensive funding from London that contributed to the Parliamentarian victory.

The Royalists were defeated and King Charles was executed in 1649; Oliver Cromwell came to power and founded the Commonwealth, where England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales were governed as a republic. Oliver Cromwell wasn’t a King and instead had the title of “Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England”.

After 365 years of banishment, Oliver Cromwell allowed the Jews to return to London in 1655, their first Synagogue was built in 1657 at Creechurch Lane.

In 1658, after Oliver Cromwell’s death, his son Richard Cromwell took over the Commonwealth but was unable to manage it properly and lost the support of the army. His failure led to monarchy being restored under Charles II in 1660.

During the 17th century the over cramped conditions of London at the time weren’t the safest place to live and there was an extreme lack of sanitation. Over the years there had been several plagues that effected London but the eight and last one was known as the “Great Plague” and brought very terrible times upon the city’s inhabitants.

The plague first started in the Netherlands in 1663 so shipping from there was banned officially, however, illegal shipping continued and the plague reached the coastal town of Yarmouth. When the disaster reached London, Charles II, his court, and other rich residents fled the city to areas where the plague had not affected. By 1666, it is estimated that there were more than 100,000 deaths in London alone, more than a quarter of the population.

As if a mass bubonic plague wasn’t enough for the inhabitants of London, in the same year the plague ended, in 1666, an event that is remembered throughout history occurred; the Great Fire of London.

The Great Fire started at one o’clock in the morning on Pudding Lane and the wind spread it to other houses made from timber (as most houses were made from timber and had thatched roofs at the time). The fire then reached a warehouse near the Tower of London containing flammable materials like pitch and this transformed it into a raging inferno that destroyed 300 houses in just 2 hours.

Much to the dismay of property owners, the King ordered houses that weren’t burnt to be demolished in order to create fire breaks but by this time the fire was out of control and had even destroyed the city’s wooden water pipes.

After an investigation, it was found out that it wasn’t just the timber houses that caused the fire to spread as it did, since London had a large trading industry at the time, the riverside district was full of warehouses stored with flammable goods like oil, tar, pitch and gunpowder. The fire reached such a high intensity that even the imported steel in the area was melted.

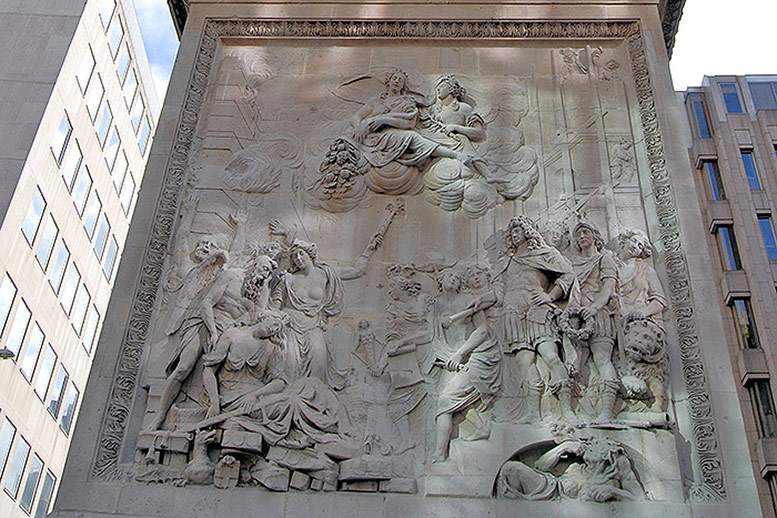

The Great Fire of London was so intense that the smoke was even seen all the way from Oxford, The fire destroyed Old St Paul’s Cathedral, 87 parish churches, 44 livery company halls, the Royal Exchange (a centre of commerce) and many prisons. Around 100,000 people became homeless after an estimated 13,500 houses were destroyed in the fire and there was a £10 million loss (the equivalent of £1.66 billion as of 2018). Refugee camps were set up at Moorfields and St. George’s Fields all the way to Highgate. The most surprising thing about this whole event however, is that only 16 people are believed to have died in the fire, the reason for this is unknown.

The Rebuilding of London Act 1666 stated that «building with brick [is] not only more comely and durable but also safer against future perils of fire». From then on, all houses had to be built using bricks and only doors and window frames were made from wood. St Paul’s Cathedral and the other destroyed churches were restored and many people moved to the East End looking for work among the expanding docks. The areas, Whitechapel, Wapping, Stepney and Limehouse became heavily populated with the dockworkers and their families, turning them into slums.

In 1694, the Bank of England was founded and the British East India Company was expanding rapidly; Lloyds of London was also founded in the 17th Century. At this time London handled 80% of England’s imports, 69% of its exports and traded with goods like silk, sugar, tea and tobacco which were luxuries at the time.

18th Century London

In 1707, the Act of Union joined the parliaments of England and Scotland together forming the Kingdom of Great Britain (England and Scotland were already ruled by a single monarch but had different parliaments). The restoration of St Paul’s Cathedral was finished in 1708 and was designed by Christopher Wren who completed the work on his birthday; St Paul’s Cathedral is thought to be one of the finest buildings in Britain.

During the 18th century, a wave of immigrants came from other countries who, not only increased the population of London but contributed to the city’s development. Britain also emerged victorious from the Seven Years’ War which expanded the economy by opening many doors for trading with other nations. In 1760, London was the largest city in Europe with a population of 750,000.