Lecture 1

1. What are the basic elements of the relationship between a language and extralinguistic world?

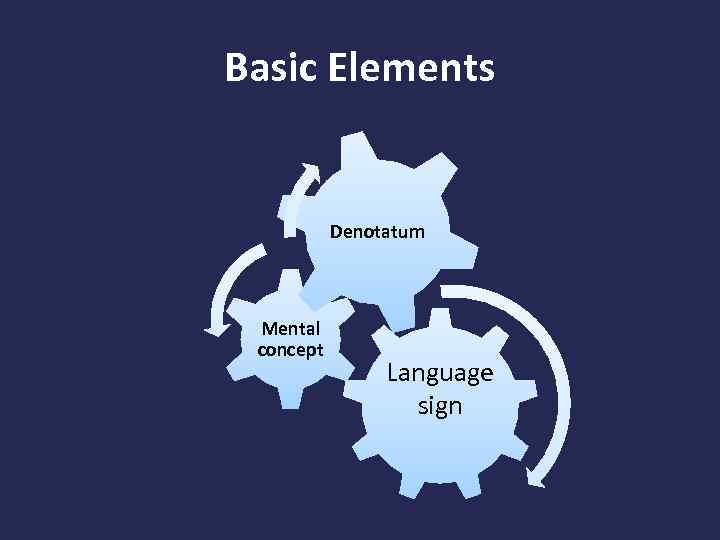

The relation of language to the extralinguistic world involves three basic sets of elements: language signs, mental concepts

and parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing) which are usually called denotata

(Singular: denotatum).

2. What is a language sign, a concept and a denotatum? Give definitions. Show the relation between them?

The LS is a sequence of sounds (in spoken language) or symbols (in written language) which is associated with a single

concept in the minds of speakers of that or another language. Те, що ми написали чи сказали.

The MC is an array of mental images and associations related to a particular part of the extralinguistic world (both really

existing and imaginary), on the one hand, and connected with a particular language sign, on the other. Тлумачення. Яка який

яке?

Denotata- parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing)- object + concept.

Denotatum is the actual object or meaning of a word, rather than the feeling or ideas connected with the word.

The relation between words (language signs) and parts of the extralinguistic world (denotata) is only indirect and going

through the mental concepts.

The relationship between a language sign and a concept is ambiguous: it is often different even in the minds of different

people, speaking the same language, though it has much in common, hence, is recognizable by all the members of the

language speakers community.

3. What is a lexical meaning, a connotation and an association? Give definitions and examples.

LM is the general mental concept corresponding to a word or a combination of words.

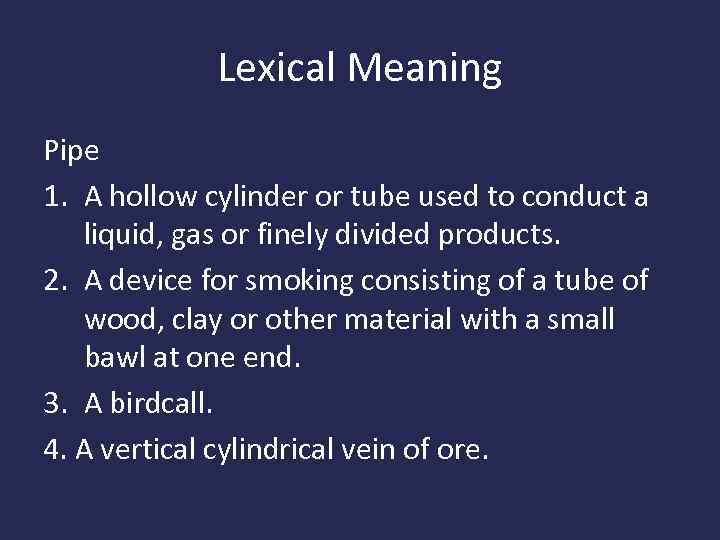

noodle — 1. type of paste of flour and water or flour and eggs pre- pared in long, narrow strips and used in soups, with a sauce,

etc.; 2. fool.

Connotation is an additional, contrastive value of the basic usually designative function of the lexical meaning. (emotional

attitude). For example, blue is a color, but it is also a word used to describe a feeling of sadness, as in: “She’s feeling blue.”

Connotations can be either positive, negative, or neutral.

Compare the words to die(померти) and to peg out(здихати). It is easy to note that the former has no connotation, whereas

the latter has a definite connotation of vulgarity.

An association is a more or less regular connection established between the given and other mental concepts in the minds of

the language speakers.

A rather regular association is established between green and fresh {young) and between green and environment protection.

4. What is the range of application of a word? Give examples.

The peculiarities of conceptual fragmentation of the world by the language speakers are manifested by the range of

application of the lexical meanings (reflected in limitations in the combination of words and stylistic peculiarities). This is

yet another problem having direct relation to translation — a translator is to observe the compatibility rules of the language

signs (e. g. make mistakes, but do business).

5. What are the main sources of translation ambiguity stemming from the sign-concept relationship?

The concepts being strongly subjective and largely different in different languages for similar denotata give rise to one of the

most difficult problems of translation, the problem of ambiguity of translation equivalents(неоднозначність

еквівалентів перекладу).

Denotata — parts of the extralinguistic world (not necessarily material or physically really existing)- object + concept.

Denotatum is the actual object or meaning of a word, rather than the feeling or ideas connected with the word.

Another source of translation ambiguity is the polysemantic nature of the language signs: the relationship between the signs

and concepts is very seldom one-to-one, most frequently it is one-to-many or many-to-one, i.e. one word has several meanings

or several words have similar meanings.

Language and Extralinguistic World Lecture 1

Overview • notions of a linguistic sign, concept and denotatum; • relations between linguistic sign, concept and denotatum; • difference between the denotative and connotative meanings of a linguistic sign; • mental concept of a linguistic sign; • relations of polysemy and synonymy • ambiguity of translation equivalents.

Basic Elements Denotatum Mental concept Language sign

Language Sign is a sequence of sounds (in spoken language) or symbols (in written language) which is associated with a single concept in the minds of speakers of that or another language.

Language Sign Vrouw Frau Femeie Kobieta

Mental Concept is an array of mental images and associations related to particular part of the extralinguistic world (both really existing and imaginary), on the other hand, and connected with a particular language sign, on the other

Mental Concept Meet Mr. X. He is an engineer.

THUS Differences in relations between language signs and mental concepts translation difficulties

Mental Concept Elements • • Lexical meanings Connotations Associations Grammatical meanings

Lexical Meaning is the general mental concept corresponding to a word or a combination of words.

Lexical Meaning Pipe 1. A hollow cylinder or tube used to conduct a liquid, gas or finely divided products. 2. A device for smoking consisting of a tube of wood, clay or other material with a small bawl at one end. 3. A birdcall. 4. A vertical cylindrical vein of ore.

Connotation is an additional, contrastive value of the basic usually designative function of the lexical meaning. Example: To avoid = to back out Fish = fish in oil field ?

Association is a more or less regular connection established between the given and other mental concepts in the minds of the language speakers

Translation Challenges Ambiguity of translation equivalents Polysemy and Synonymy

The

extralinguistic causes are determined by the social nature of the

language: they are observed in changes of meaning resulting from the

development of the notion expressed and the thing named and by the

appearance of new notions and things. In other words, extralinguistic

causes of semantic change are connected with the development of the

human mind as it moulds reality to conform with its needs.

Languages are powerfully

affected by social, political, economic, cultural and technical

change. The influence of those factors upon linguistic phenomena is

studied by sociolinguistics. It shows that social factors can

influence even structural features of linguistic units: terms of

science, for instance, have a number of specific features as compared

to words used in other spheres of human activity.

The

word being a linguistic realisation of notion, it changes with the

progress of human consciousness. This process is reflected in the

development of lexical meaning. As the human mind achieves an ever

more exact understanding of the world of reality and the objective

relationships that characterise it, the notions become more and more

exact reflections of real things. The history of the social, economic

and political life of the people, the progress of culture and science

bring about changes in notions and things influencing the semantic

aspect of language. For instance, OE eorde

meant

‘the ground under people’s feet’, ‘the soil’ and ‘the

world of man’ as opposed to heaven that was supposed to be

inhabited first by Gods and later on, with the spread of

Christianity, by God, his angels, saints and the souls of the dead.

With the progress of science earth

came

to mean the third planet from

the

sun and the knowledge is constantly enriched. With the development of

electrical engineering earth

n means

‘a connection of a wire

1

ellipsis combined with metonymy see p. 68.

73

conductor

with the earth’, either accidental (with the result of leakage of

current) or intentional (as for the purpose of providing a return

path). There is also a correspond ing verb earth.

E.

g.: With

earthed appliances the continuity of the earth wire ought to be

checked.

The

word space

meant

‘extent of time or distance’ or ‘intervening distance’.

Alongside this meaning a new meaning developed ‘the limitless and

indefinitely great expanse in which all material objects are

located’. The phrase outer

space was

quickly ellipted into space.

Cf.

spacecraft,

space-suit, space travel, etc.

It

is interesting to note that the English word cosmos

was

not exactly a synonym of outer

space but

meant ‘the universe as an ordered system’, being an antonym to

chaos.

The

modern usage is changing under the influence of the Russian language

as a result of Soviet achievements in outer space. The OED Supplement

points out that the adjective cosmic

(in

addition to the former meanings ‘universal’, ‘immense’) in

modern usage under the influence of Russian космический

means

‘pertaining to space travel’, e. g. cosmic

rocket ‘space

rocket’.

The

extra-linguistic motivation is sometimes obvious, but some cases are

not as straightforward as they may look. The word bikini

may

be taken as an example. Bikini, a very scanty two-piece bathing suit

worn by women, is named after Bikini atoll in the Western Pacific but

not because it was first introduced on some fashionable beach there.

Bikini

appeared at the time when the atomic bomb tests by the US in

the Bikini atoll were fresh in everybody’s memory. The associative

field is emotional referring to the “atomic” shock the first

bikinis produced.

The

tendency to use technical imagery is increasing in every language,

thus the expression to

spark off in chain reaction is

almost international. Live

wire ‘one

carrying electric current’ used figuratively about a person of

intense energy seems purely English, though.

Other

international expressions are black

box and

feed-back.

Black box formerly

a term of aviation and electrical engineering is now used

figuratively to denote any mechanism performing intricate functions

or any unit of which we know the effect but not the components or

principles of action.

Feed-back

a

cybernetic term meaning ‘the return of a sample of the output of a

system or process to the input, especially with the purpose of

automatic adjustment and control’ is now widely used figuratively

meaning ‘response’.

Some

technical expressions that were used in the first half of the 19th

century tend to become obsolete: the English used to talk of people

being

galvanised into activity, or

going

full steam ahead but

the phrases sound dated now.

The

changes of notions and things named go hand in hand. They are

conditioned by changes in the economic, social, political and

cultural history of the people, so that the extralinguistic causes of

semantic change might be conveniently subdivided in accordance with

these. Social relationships are at work in the cases of elevation and

pejoration of meaning discussed in the previous section where the

attitude of the upper classes to their social inferiors determined

the strengthening of emotional tone among the semantic components of

the word.

74

Sociolinguistics

also teaches that power relationships are reflected in vocabulary

changes. In all the cases of pejoration that were mentioned above,

such as boor,

churl, villain, etc.,

it was the ruling class that imposed evaluation. The opposite is

rarely the case. One example deserves attention though: sir

+

-ly

used

to mean ‘masterful1

and now surly

means

‘rude in a bad-tempered way’.

D.

Leith devotes a special paragraph in his “Social History of

English” to the semantic disparagement of women. He thinks that

power relationships in English are not confined to class

stratification, that male domination is reflected in the history of

English vocabulary, in the ways in which women are talked about.

There is a rich vocabulary of affective words denigrating women, who

do not conform to the male ideal. A few examples may be mentioned.

Hussy

is

a reduction of ME huswif

(housewife), it

means now ‘a woman of low morals’ or ‘a bold saucy girl’;

doll

is

not only a toy but is also used about a kept mistress or about a

pretty and silly woman; wench

formerly

referred to a female child, later a girl of the rustic or working

class and then acquired derogatory connotations.

Within

the diachronic approach the phenomenon of euphemism

(Gr

euphemismos

<

eu

‘good’

and pheme

‘voice’)

has been repeatedly classed by many linguists as tabоо,

i.e.

a prohibition meant as a safeguard against supernatural forces. This

standpoint is hardly acceptable for modern European languages. St.

Ullmann returns to the conception of taboo several times illustrating

it with propitiatory names given in the early periods of language

development to such objects of superstitious fear as the bear and the

weasel. He proves his point by observing the same phenomenon, i.e.

the circumlocution used to name these animals, in other languages.

This is of historical interest, but no similar opposition between a

direct and a propitiatory name for an animal, no matter how

dangerous, can be found in present-day English.

With

peoples of developed culture and civilisation euphemism is

intrinsically different, it is dictated by social usage, etiquette,

advertising, tact, diplomatic considerations and political

propaganda.

From

the semasiological point of view euphemism is important, because

meanings with unpleasant connotations appear in words formerly

neutral as a result of their repeated use instead of words that are

for some reason unmentionable, cf.

deceased

‘dead’,

deranged

‘mad’.

Much

useful material on the political and cultural causes of coining

euphemisms is given in “The Second Barnhart Dictionary of New

English”. We read there that in modern times euphemisms became

important devices in political and military propaganda. Aggressive

attacks by armadas of bombers which most speakers of English would

call air

raids are

officially called protective

reaction, although

there is nothing protective or defensive about it. The CIA agents in

the United States often use the word destabilise

for

all sorts of despicable or malicious acts and subversions designed to

cause to topple an established foreign government or to falsify an

electoral campaign. Shameful secrets of various underhand CIA

operations, assassinations, interception of mail, that might, if

revealed, embarrass the government, are called family

jewels.

75

It

is decidedly less emotional to call countries with a low standard of

living underdeveloped,

but

it seemed more tactful to call them developing.

The

latest terms (in the 70s)

are

L.D.C.

—

less

developed countries and

M.D.C.

—

more

developed countries, or

Third

World countries or

emerging

countries if

they are newly independent.

Other

euphemisms are dictated by a wish to give more dignity to a

profession. Some barbers called themselves hair

stylists and

even hairologists,

airline stewards and

stewardesses

become

flight

attendants, maids

become

house

workers, foremen become

supervisors,

etc.

Euphemisms

may be dictated by publicity needs, hence ready-tailored

and

ready-to-wear

clothes instead

of ready-made.

The

influence of mass-advertising

on language is growing, it is felt in every level of the language.

Innovations

possible in advertising are of many different types as G.N. Leech has

shown, from whose book on advertising English the following example

is taken. A kind of orange juice, for instance, is called Tango.

The

justification of the name is given in the advertising text as

follows: “Get

this different tasting Sparkling Tango. Tell you why: made from whole

oranges. Taste those oranges. Taste the tang in Tango. Tingling tang,

bubbles —

sparks.

You drink it straight. Goes down great. Taste the tang in Tango. New

Sparkling Tango”. The

reader will see for himself how many expressive connotations and

rhythmic associations are introduced by the salesman in this

commercial name in an effort to attract the buyer’s attention. If

we now turn to the history of the language, we see economic causes

are obviously at work in the semantic development of the word wealth.

It

first meant ‘well-being’, ‘happiness’ from weal

from

OE wela

whence

well.

This

original meaning is preserved in the compounds commonwealth

and

commonweal.

The

present meaning became possible due to the role played by money both

in feudal and bourgeois society. The chief wealth of the early

inhabitants of Europe being the cattle, OE feoh

means

both ‘cattle’ and ‘money’, likewise Goth faihu;

Lat

pecus

meant

‘cattle’ and pecunia

meant

‘money’. ME fee-house

is

both a cattle-shed and a treasury. The present-day English fee

most

frequently means the price paid for services to a lawyer or a

physician. It appears to develop jointly from the above mentioned OE

feoh

and

the Anglo-French fee,

fie, probably

of the same origin, meaning ‘a recompense’ and ‘a feudal

tenure’. This modern meaning is obvious in the

following example: Physicians

of the utmost fame were called at once, but

when they came they answered as they took their fees, “There is no

cure for this disease.” (Belloc)

The

constant development of industry, agriculture, trade and transport

bring into being new objects and new notions. Words to name them are

either borrowed or created from material already existing in the

language and it often happens that new meanings are thus acquired by

old words.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #