Compounding

or word-composition

is

one

of the major and highly productive types of word-formation, one of

the potent means of replenishment of English word-stock. This type of

word formation was very productive in Old English and it hasn’t

lost its productivity till present time. More than one third of all

the new words in modern English are compound words. Compound words as

the term itself suggests are lexical units of complex structure.

Many

definitions offered by linguists (А.I.Smirnitsky, I.V.Аrnold,

О.D.Меshkov, H.Маrchаnd, О.Jesрersеn, R.V.Zаndvоrt) соme

to the following one: a

compound word is a lexical unit formed by joining together two or

more derivational bases and singled out in speech due to its

integrity.

The

derivational bases may be of different degrees of complexity as, e.g.

arm-chair,

prizefighter, fancy-dress-maker, forget-me-not, merry-go-round,

pay-as-you-earn,

etc. Notwithstanding the fact that many linguists devoted their

researches to word-composition, still some of the issues concerning

this type of word formation are open to debate. One of the

difficulties is the problem of distinguishing compound words from

word combinations (word-groups, phrases). Comparing such compound

words as

running water

‘water coming from a mains supply – Rus. водопровод’

a

dancing—girl

‘a professional dancer – Rus. танцовщица’ with the

word combinations running

water

‘water that runs – Rus. проточная вода’ and

a dancing girl

‘a girl who is dancing – Rus. танцующая девушка’

and many others, it is difficult to determine whether we deal with

compound words or word combinations.

The

most important property of compound words is their integrity (see

section 1 of chapter I) which is understood as impossibility to

insert other units of the language (morphemes, words) between the

components of a compound word. Integrity might be also considered

the basic criterion of distinguishing compound words from word

combinations and other language units. Compound words possess both

structural and semantic integrity.

Structural

integrity of compound words manifests itself in the fixed

order of

their components. The second IC (Immediate Constituent) is in

overwhelming majority of compound words the structural and semantic

centre, the onomasiological basis of the word. In compound words like

a

house-dog

and a

dog-house

and many others, it is the second component that determines the part

of speech, i.e. lexico-grammatical properties of the compound, and

its referent, or what actually the word denotes, while the first

component modifies the meaning of the second one:

a house-dog

– a

dog

trained to guard a house; a

dog-house

– a

house

for a dog.

For

some types of compound words the indication of integrity is the

reverse order of the components as compared with word combinations.

It is the case of the compounds with the second components expressed

by adjectives and participles, e.g.

oil-rich, man-made.

In the synonymous word combinations the word order is: rich

in oil, made by man.

There

are other criteria employed for distinguishing compound words from

word combinations taking into account various aspects of compound

words. The phonetic

(phonic) criterion rests

on the marked tendency in English to give compounds a heavy stress on

the first component. It is true that compound words in many cases are

given single, or the so-called unity stress; or two stresses – a

primary and a secondary one. Such stress patterns differ from the

stress patterns of word combinations where each notional word is

stressed. For instance, each of the words road

and

house

is stressed in a word combination, e.g. a

`house

by the `road

but when they make up a compound word a `roadhouse ‘a building on a

main road’ the stress pattern is changed, the word acquires a unity

stress on the first component or double stress (the primary and

secondary ones) as in the words `blood-vessel,

`washing-maֽِchine.

The phonic criterion will prove that `laughing

`boys

‘the boys who are laughing’ is a word combination (word group)

but `laughing-gas

‘gas used in dental surgery’ is a compound word. However, not

infrequent are the cases with the so-called level stress when each

component is equally stressed: `arm-`chair,

`snow-`white,

`icy-`cold.

Hence, the phonic criterion is not quite reliable.

The

structural integrity of a compound word differing from structural

separateness of a word combination is backed up by the morphological

(morphemic)

criterion.

A

sequence of components making up a

compound

word is a morphemic unity and it has a single paradigm. It means that

the grammatical inflections are added to the word as a whole but not

to its separate parts, e.g. earthquake

– earthquakes,

weekend – weekends.

In a word combination each of the component parts is morphemically

independent and may attract the grammatical inflections (сf.

age-long

and ages

ago).

This criterion, however, is limited for the English language because

of the scarcity of its grammatical morphemic means.

To

the syntactic

criterion

besides the above-mentioned fixed order of the components refers the

character of

syntactic

relations. The components of compound words cannot enter into the

syntactic

relations

of their own. Thus in the word combination (a

factory)

financed

by the government

each notional word may be modified by an attribute: a

factory generously

financed by the British

government

(the example is borrowed from [Мешков 1976: 182]). None of the

components of a compound word can be modified by an attribute:

*generously

government-financed.

Modifying a component of a compound word is only possible by

introducing one more component into the structure of a compound word:

Labour-government-financed.

However, syntactic parameters do not unambiguously solve the problem

of distinguishing a compound word from a word combination because the

collocability of the components of word combinations may be limited.

The

semantic

criterion presupposes

the semantic integrity of a compound word, close semantic links

between its components. According to this criterion the following

examples refer to compound words: daybreak,

blackmail,

killjoy

and

many others. But the semantic criterion seems to be the most

unreliable one as it is not always possible to objectively determine

to what extent the components are semantically linked together.

Besides it is impossible to draw a line between compound words and

phraseological units, idioms which are characterized by semantic

unity.

As

one more criterion of structural integrity of compound words might be

named the graphic

criterion.

The majority of compound words are spelled either solidly or with a

hyphen. But there is no consistency in English spelling in this

respect. The same words may be spelt either solidly, with a hyphen or

with a break. The spelling varies with different texts and even

dictionaries (e.g. airline,

air-line, air line).

There is statistic data concerning the variability of spelling, e.g.

complexes with the first components well-,

ill—

(e.g. ill-advised,

ill-affected,

well-dressed,

well-aimed)

in 34 % cases are spelt with a break, in 66% with a hyphen

[Харитончик 1992: 180]. The vacillations in spelling are

most frequent in ‘n + n’ pattern: war(-)time,

money(-)order, post(-)card,

etc. E. Pаrtridge in his book “Usage and Abusage” writes that a

compound word goes through three stages in its evolution: (1) two

separate words (cat

bird);

(2) a compound word spelt with a hyphen (cat-bird);

(3) a solidly spelt word (catbird).

Thus, solid spelling of compounds is manifestation of language

consciousness, the moment when the lexical unit is perceived as

having acquired a semantic unity. Solid or hyphenated spellings are

indications of compound words, although cases of a break between

components allow of various interpretations.

So

far not a single criterion is reliable enough to identify compound

words. Moreover, even a combination of criteria is not sufficient

enough to unequivocally decide whether the lexical unit is a compound

word or a word combination.

The

second aspect of the issue of identification of compound words and

determining the types of word-formation is the problem of delineation

between compounding and other types of word-formation resulting in

appearance of compound words. Such words as long-legged,

three-cornered,

schoolmasterish

are complex in their morphological structure but according to the

type of word formation they refer to suffixal derivatives. Their

derivational patterns are as follows: long-legged

~ (long

+ leg)

+-ed

~ (a + n) + sf , but not long

+ legged,

as there is no such a derivational base as *legged.

By analogy: three-cornered

~ (num + n) + sf, schoolmasterish

~ (n + n) + sf. Such words are considered to be compound

derivatives.

They must be distinguished from the words of the type pen-holder,

tongue-twister,

which are derived by compounding, i.e. bringing together two

derivational bases pen

+

(hold

+ —er)

~

n + (n + sf), which are compound words.

Besides

suffixal

compound

derivatives to compound derivatives refer the words formed by

conversion: breakthrough

n. from to

break through,

breakdown

n. from to

break down,

based on V > N pattern, to

blackmail

from blackmail

n. (N > V), back formation (see the next section 5):

to baby-sit

from baby-sitter,

to

fact-find

from fact-finding

‘inquiring into facts’.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

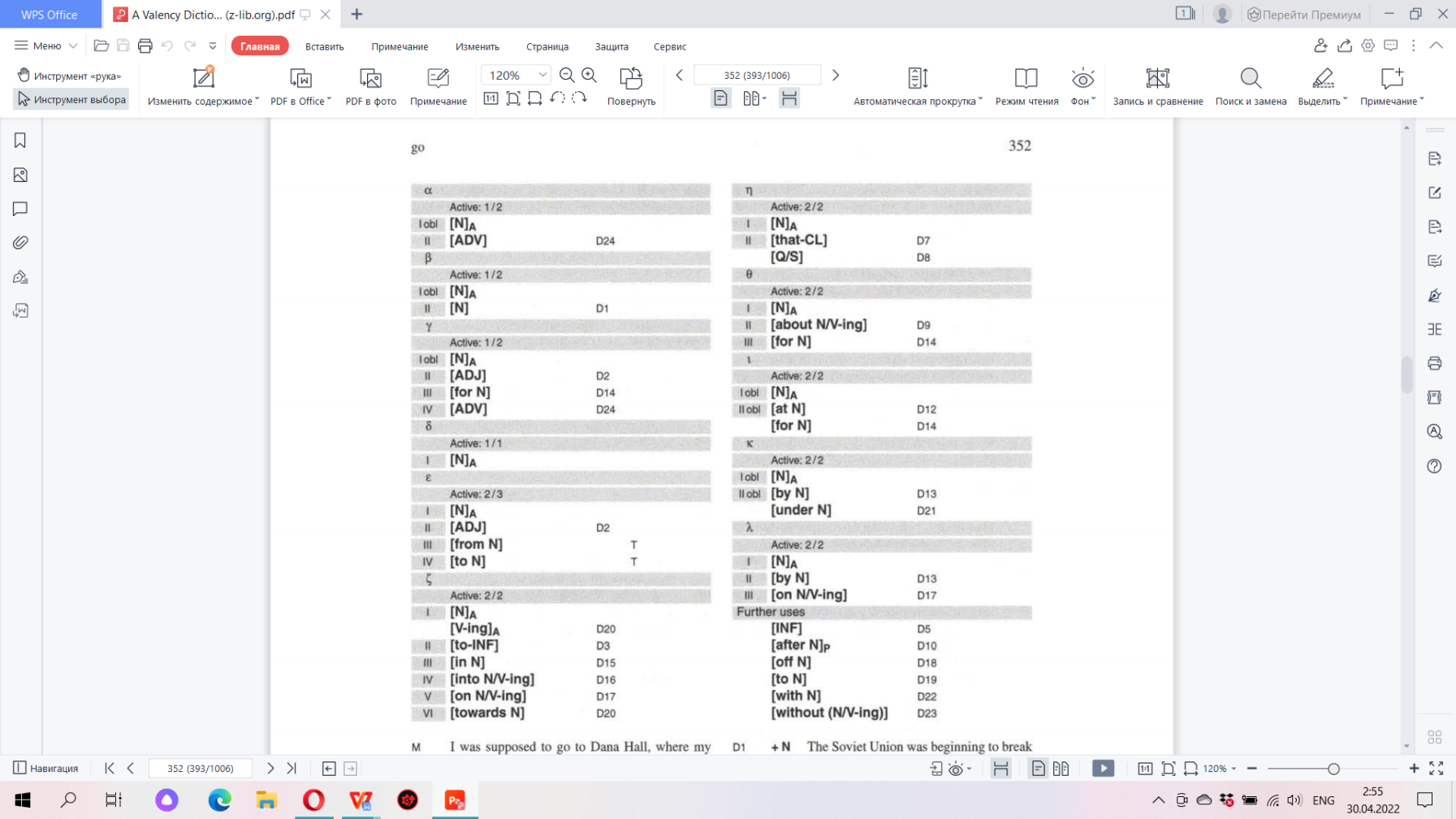

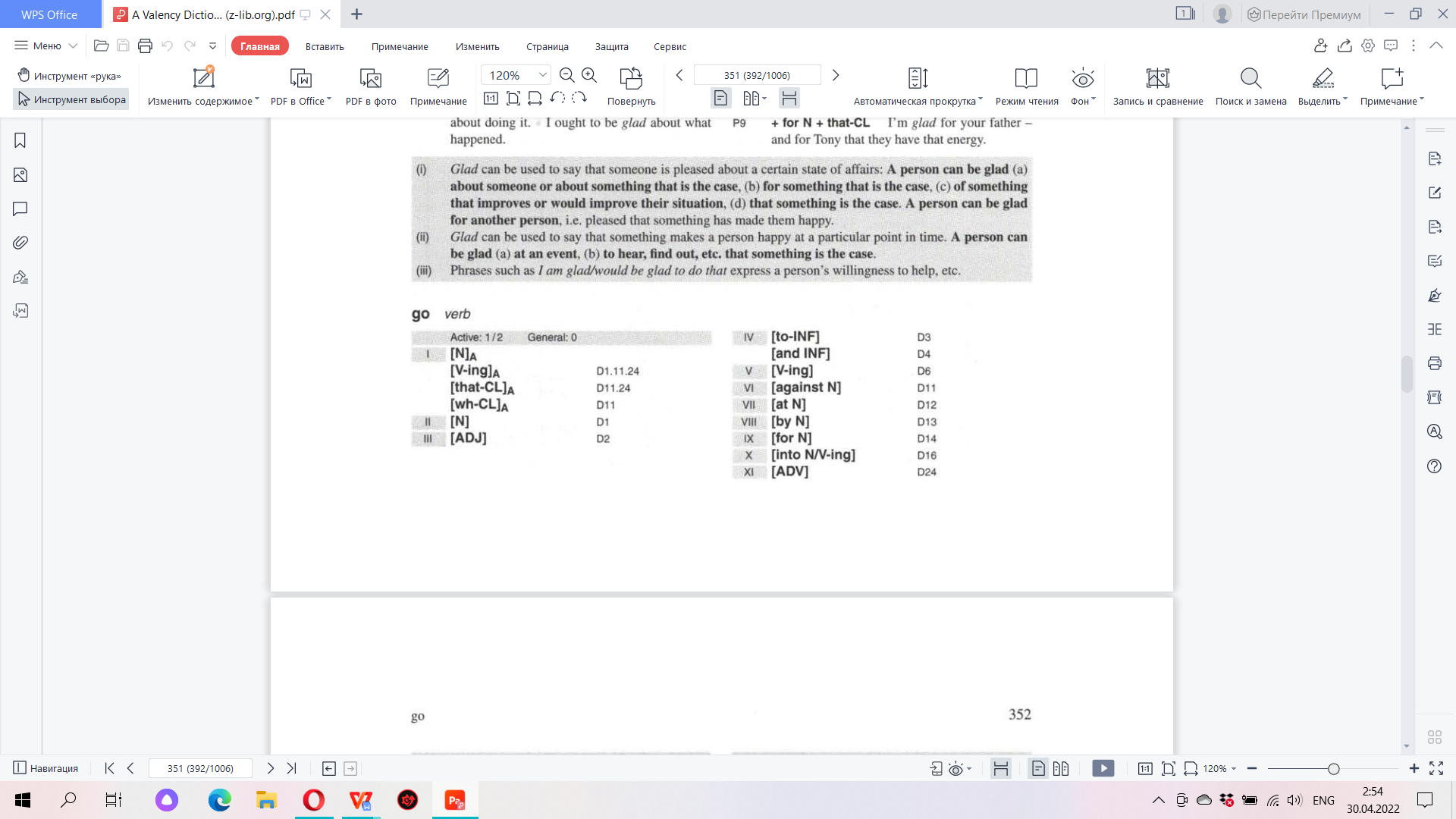

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |

WORD COMBINATIONS IN MODERN ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY

WORD COMBINATIONS Words traditionally collocated in speech tend to make up so called cliches or traditional word combinations. In traditional combinations words retain their full semantic independence although they are limited in their combinative power (e. g. : to wage a war, to render a service, to make friends). Words in traditional combinations are combined according to the patterns of grammatical structure of the given language.

WORD COMBINATION it should be pointed out that the syntactic terminology varies from author to author. Thus, Professor Illiysh operates with the term “phrase”. The definition given by the scholar to the phrase (“every combination of two or more words which is a grammatical unit but is not an analytical form of some word”) leaves no doubt as to its equivalence to the term “word combination”. The word combination, along with the sentence, is the main syntactic unit. The smallest word combination consists of two members, whereas the largest word combination may theoretically be indefinitely large though this issue has not yet been studied properly.

WORD COMBINATION Despite its cornerstone status for the syntactic theory, the generally recognized definition of the word combination has not been agreed upon: it receives contradictory interpretations both from different linguists. The traditional point of view, dating back to Prof. Vinogradov’s works (i. e. to the middle of the 20 th century), interprets the word combination exclusively as subordinate unit. Meanwhile, many linguists tend to treat any syntactically organized group of words as word combination regardless the type of relationship between its elements.

Free and bound (phraseological) word combinations Another definition of word combination says that. . A Word combination (phrase ) is a non-predicative unit of speech which is, semantically, both global and articulated. In grammar, it is seen as a group of words that functions as a single unit in the syntax of a sentence. It is an intermediate unit between a word and a sentence. The main function of a word combination is polinomination (it describes an object, phenomenon or action and its attributes and properties at the same time). There are two types of word combinations (also known as setexpressions, set-phrases, fixed word-groups, etc. ): Free word combinations in which each component may enter different combinations Set (phraseological) combinations consist of elements which are used only in combination with one another

Traditional combinations fall into structural types as: 1. V+N combinations E. G. : deal a blow, bear a grudge, take a fancy, etc 2. V+ preposition + N E. G. : fall into disgrace, go into details, go into particular, take into account, come into being, etc.

Traditional combinations fall into structural types as: 3. V + Adj. : E. G. : work hard, rain heavily etc. 4. V + Adj. : E. G. : set free, make sure, put right etc.

Traditional combinations fall into structural types as: 5. Adj. + N. : maiden voyage, ready money, dead silence, feline eyes, aquiline nose, auspicious circumstances etc. 6. N + V: time passes / flies / elapses, options differ, tastes vary etc. 7. N + preposition + N: breach of promise, flow of words, flash of hope, flood of tears.

SET-PHRASES OR PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS The degree of structural and semantic cohesion of words within word-groups may vary. Some word-groups are functionally and semantically inseparable, e. g. rough diamond, cooked goose, to stew in one’s own juice. Such word-groups are traditionally described as set-phrases or phraseological units. Characteristic features of phraseological units are non-motivation for idiomaticity and stability of context. The cannot be freely made up in speech but are reproduced as ready-made units.

WORD-GROUPS Every utterance is a patterned, rhythmed and segmented sequence of signals. On the lexical level these signals building up the utterance are not exclusively words. Alongside with separate words speakers use larger blocks consisting of more than one word. Words combined to express ideas and thoughts make up word-groups.

FREE WORD-GROUPS The component members in other word-groups possess greater semantic and structural independence, e. g. to cause misunderstanding, to shine brightly, linguistic phenomenon, red rose. Word-groups of this type are defined as free word-groups for free phrases. They are freely made up in speech by the speakers according to the needs of communication.

SET EXPRESSIONS Set expressions are contrasted to free phrases and semi-fixed combinations. All these different stages of restrictions imposed upon co-occurance of words, upon the lexical filling of structural patterns which are specific for every language. The restriction may be independent of the ties existing in extra-linguistic reality between the object spoken of and be conditioned by purely linguistic factors, or have extralinguistic causes in the history of the people

STRUCTURE OF WORD GROUPS Structurally word-groups may be approached in various ways. All word-groups may be analysed by the criterion of distribution into two big classes. Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit can be used. If the word-group has the same linguistic distribution as one of its members, It is described as endocentric, i. e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole wordgroup. The word-groups, e. g. red flower, bravery of all kinds, are distributionally identical with their central components flower and bravery: I saw a red flower — I saw a flower. I appreciate bravery of all kinds — I appreciate bravery.

STRUCTURE OF WORD GROUPS If the distribution of the word-group is different from either of its members, it is regarded as exocentric, i. e. as having no such central member, for instance side by side or grow smaller and others where the component words are not syntactically substitutable for the whole word-group. In endocentric word-groups the central component that has the same distribution as the whole group is clearly the dominant member or the head to which all other members of the group are subordinated. In the word-group red flower the head is the noun flower and in the word-group kind of people the head is the adjective kind.

PREDICATIVE AND NONPREDICATIVE GROUPS Word-groups are also classified according to their syntactic pattern into predicative and non-predicative groups. Such word-groups, e. g. John works, he went that have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence, are classified as predicative, and all others as non-predicative. Non-predicative word-groups may be subdivided according to the type of syntactic relation between the components into subordinative and coordinative. Such word-groups as red flower, a man of wisdom and the like are termed subordinative in which flower and man are headwords and red, of wisdom are subordinated to them respectively and function as their attributes. Such phrases as woman and child, day and night, do or die are classified as coordinative. Both members in these wordgroups are functionally and semantically equal.

SUBORDINATIVE WORDGROUPS Subordinative word-groups may be classified according to their head-words into nominal groups (red flower), adjectival groups (kind to people), verbal groups (to speak well), pronominal (all of them), statival (fast asleep). The head is not necessarily the component that occurs first in the word-group. In such nominal wordgroups as e. g. very great bravery, bravery in the struggle the noun bravery is the head whether followed or preceded by other words.

THE LEXICAL MEANING OF THE WORD-GROUP The lexical meaning of the word-group may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component words. Thus the lexical meaning of the word-group red flower may be described denotationally as the combined meaning of the words red and flower. The meaning of the component words are mutually dependent and the meaning of the word-group naturally predominates over the lexical meanings of its constituents.

PATTERN OF ARRANGEMENT Word-groups possess not only the lexical meaning, but also the meaning conveyed by the pattern of arrangement of their constituents. Such word-groups as school grammar and grammar school are semantically different because of the difference in the pattern of arrangement of the component words.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING What do we call word groups? What are set expressions? What does the term linguistic distribution mean and what are their types? What do you know about predicative and nonpredicative groups? The classification of subordinative word-groups is… What does the pattern of arrangement mean? What is another term for traditional word combinations?