Mechanical engineer Joel Steinkraus and systems engineer Farah Alibay (right) from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory hold a full-scale mockup of Mars Cube One |

|

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Engineer |

|

Occupation type |

Profession |

|

Activity sectors |

Applied science |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Mathematics, science, design, analysis, critical thinking, engineering ethics, project management, engineering economics, creativity, problem solving, (See also: Glossary of engineering) |

|

Education required |

Engineering education |

|

Fields of |

Research and development, industry, business |

|

Related jobs |

Scientist, architect, project manager, inventor, astronaut |

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limitations imposed by practicality, regulation, safety and cost.[1][2] The word engineer (Latin ingeniator[3]) is derived from the Latin words ingeniare («to contrive, devise») and ingenium («cleverness»).[4][5] The foundational qualifications of an engineer typically include a four-year bachelor’s degree in an engineering discipline, or in some jurisdictions, a master’s degree in an engineering discipline plus four to six years of peer-reviewed professional practice (culminating in a project report or thesis) and passage of engineering board examinations.

The work of engineers forms the link between scientific discoveries and their subsequent applications to human and business needs and quality of life.[1]

Definition[edit]

In 1961, the Conference of Engineering Societies of Western Europe and the United States of America defined «professional engineer» as follows:[6]

A professional engineer is competent by virtue of his/her fundamental education and training to apply the scientific method and outlook to the analysis and solution of engineering problems. He/she is able to assume personal responsibility for the development and application of engineering science and knowledge, notably in research, design, construction, manufacturing, superintending, managing and in the education of the engineer. His/her work is predominantly intellectual and varied and not of a routine mental or physical character. It requires the exercise of original thought and judgement and the ability to supervise the technical and administrative work of others. His/her education will have been such as to make him/her capable of closely and continuously following progress in his/her branch of engineering science by consulting newly published works on a worldwide basis, assimilating such information and applying it independently. He/she is thus placed in a position to make contributions to the development of engineering science or its applications. His/her education and training will have been such that he/she will have acquired a broad and general appreciation of the engineering sciences as well as thorough insight into the special features of his/her own branch. In due time he/she will be able to give authoritative technical advice and to assume responsibility for the direction of important tasks in his/her branch.

Roles and expertise[edit]

Design[edit]

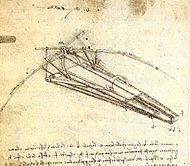

An aerial screw (c. 1489), suggestive of a helicopter, from the Codex Atlanticus

Engineers develop new technological solutions. During the engineering design process, the responsibilities of the engineer may include defining problems, conducting and narrowing research, analyzing criteria, finding and analyzing solutions, and making decisions. Much of an engineer’s time is spent on researching, locating, applying, and transferring information.[7] Indeed, research suggests engineers spend 56% of their time engaged in various information behaviours, including 14% actively searching for information.[8]

Engineers must weigh different design choices on their merits and choose the solution that best matches the requirements and needs. Their crucial and unique task is to identify, understand, and interpret the constraints on a design in order to produce a successful result.

Analysis[edit]

Engineers conferring on prototype design, 1954

Engineers apply techniques of engineering analysis in testing, production, or maintenance. Analytical engineers may supervise production in factories and elsewhere, determine the causes of a process failure, and test output to maintain quality. They also estimate the time and cost required to complete projects. Supervisory engineers are responsible for major components or entire projects. Engineering analysis involves the application of scientific analytic principles and processes to reveal the properties and state of the system, device or mechanism under study. Engineering analysis proceeds by separating the engineering design into the mechanisms of operation or failure, analyzing or estimating each component of the operation or failure mechanism in isolation, and recombining the components. They may analyze risk.[9][10][11][12]

Many engineers use computers to produce and analyze designs, to simulate and test how a machine, structure, or system operates, to generate specifications for parts, to monitor the quality of products, and to control the efficiency of processes.

Specialization and management[edit]

NASA Launch Control Center Firing Room 2 as it appeared in the Apollo era

Most engineers specialize in one or more engineering disciplines.[1] Numerous specialties are recognized by professional societies, and each of the major branches of engineering has numerous subdivisions. Civil engineering, for example, includes structural engineering, along with transportation engineering, geotechnical engineering, and materials engineering, including ceramic, metallurgical, and polymer engineering. Mechanical engineering cuts across most disciplines since its core essence is applied physics. Engineers also may specialize in one industry, such as motor vehicles, or in one type of technology, such as turbines or semiconductor materials.[1]

Several recent studies have investigated how engineers spend their time; that is, the work tasks they perform and how their time is distributed among these. Research[8][13] suggests that there are several key themes present in engineers’ work: technical work (i.e., the application of science to product development), social work (i.e., interactive communication between people), computer-based work and information behaviors. Among other more detailed findings, a 2012 work sampling study[13] found that engineers spend 62.92% of their time engaged in technical work, 40.37% in social work, and 49.66% in computer-based work. Furthermore, there was considerable overlap between these different types of work, with engineers spending 24.96% of their time engaged in technical and social work, 37.97% in technical and non-social, 15.42% in non-technical and social, and 21.66% in non-technical and non-social.

Engineering is also an information-intensive field, with research finding that engineers spend 55.8% of their time engaged in various different information behaviors, including 14.2% actively information from other people (7.8%) and information repositories such as documents and databases (6.4%).[8]

The time engineers spend engaged in such activities is also reflected in the competencies required in engineering roles. In addition to engineers’ core technical competence, research has also demonstrated the critical nature of their personal attributes, project management skills, and cognitive abilities to success in the role.[14]

Types of engineers[edit]

There are many branches of engineering, each of which specializes in specific technologies and products. Typically, engineers will have deep knowledge in one area and basic knowledge in related areas. For example, mechanical engineering curricula typically include introductory courses in electrical engineering, computer science, materials science, metallurgy, mathematics, and software engineering.

An engineer may either be hired for a firm that requires engineers on a continuous basis, or may belong to an engineering firm that provides engineering consulting services to other firms.

When developing a product, engineers typically work in interdisciplinary teams. For example, when building robots an engineering team will typically have at least three types of engineers. A mechanical engineer would design the body and actuators. An electrical engineer would design the power systems, sensors, electronics, embedded software in electronics, and control circuitry. Finally, a software engineer would develop the software that makes the robot behave properly. Engineers that aspire to management engage in further study in business administration, project management and organizational or business psychology. Often engineers move up the management hierarchy from managing projects, functional departments, divisions and eventually CEOs of a multi-national corporation.

| Branch | Focus | Related sciences | Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automobile engineering | Focuses on the development of automobiles and related technology | Structural engineering, electronics, materials science, automotive safety, fluid mechanics, thermodynamics, engineering mathematics, ergonomics, environmental compliance, road traffic safety, chemistry | Automobiles |

| Aerospace engineering | Focuses on the development of aircraft and spacecraft | Aeronautics, astrodynamics, astronautics, avionics, control engineering, fluid mechanics, kinematics, materials science, thermodynamics | Aircraft, robotics, spacecraft, trajectories |

| Agricultural engineering | Focuses on the engineering, science, and technology for the production and processing of food from agriculture, such as the production of arable crops, soft fruit and livestock. A key goal of this discipline is to improve the efficacy and sustainability of agricultural practices for food production. | Agricultural engineering often combines and converges many other engineering disciplines such as Mechanical engineering, Civil engineering, electrical engineering, chemical engineering, biosystems engineering, soil science, environmental engineering | Livestock, food, horticulture, forestry, renewable energy crops.

Agricultural machinery such as tractors, combine harvesters, forage harvesters. Agricultural technology incorporates such things as robotics and autonomous vehicles. |

| Architectural engineering and building engineering | Focuses on building and construction | Architecture, architectural technology | Buildings and bridges |

| Biomedical engineering | Focuses on closing the gap between engineering and medicine to advance various health care treatments. | Biology, physics, chemistry, medicine | Prostheses, medical devices, regenerative tissue growth, various safety mechanisms, genetic engineering |

| Chemical engineering | Focuses on the manufacturing of chemicals and or extraction of chemical species from natural resources | Chemistry, thermodynamics, chemical thermodynamics, process engineering, transport phenomena, nanotechnology, biology, chemical kinetics, genetic engineering medicine, fluid mechanics, textiles | Chemicals, hydrocarbons, fuels, medicines, raw materials, food and drink, waste treatment, pure gases, plastics, coatings, water treatment, textiles |

| Civil engineering | Focuses on the construction of large systems, structures, and environmental systems | Statics, fluid mechanics, soil mechanics, structural engineering, transportation engineering, geotechnical engineering, environmental engineering, hydraulic engineering | Roads, bridges, dams, buildings, structural system, foundation, earthworks, waste management, water treatment |

| Computer engineering | Focuses on the design and development of computer hardware & software systems | Computer science, mathematics, electrical engineering | Microprocessors, microcontrollers, operating systems, embedded systems, computer networks |

| Electrical engineering | Focuses on application of electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism | Mathematics, probability and statistics, engineering ethics, engineering economics, instrumentation, materials science, physics, network analysis, electromagnetism, linear system, electronics, electric power, logic, computer science, data transmission, systems engineering, control engineering, signal processing | Electricity generation and equipment, remote sensing, robotics, control system, computers, home appliances, Internet of things, consumer electronics, avionics, hybrid vehicles, spacecraft, unmanned aerial vehicles, optoelectronics, embedded systems |

| Fire protection engineering | Focuses on application of science and engineering principles to protect people, property, and their environments from the harmful and destructive effects of fire and smoke. | Fire, smoke, fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, heat transfer, combustion, physics, materials science, chemistry, statics, dynamics, probabilistic risk assessment or risk management, environmental psychology, engineering ethics, engineering economics, systems engineering, reliability, fire suppression, fire alarms, building fire safety, wildfire, building codes, measurement and simulation of fire phenomena, mathematics, probability and statistics. | Fire suppression systems, fire alarm systems, passive fire protection, smoke control systems, sprinkler systems, Code consulting, fire and smoke modeling, emergency management, water supply systems, fire pumps, structural fire protection, foam extinguishing systems, gaseous fire suppression systems, oxygen reduction systems, flame detection, aerosol fire suppression. |

| Industrial engineering | Focuses on the design, optimization, and operation of production, logistics, and service systems and processes | Operations research, engineering statistics, applied probability and stochastic processes, automation engineering, methods engineering, production engineering, manufacturing engineering, systems engineering, logistics engineering, ergonomics | quality control systems, manufacturing systems, warehousing systems, supply chains, logistics networks, queueing systems, business process management |

| Mechatronics engineering | Focuses on the technology and controlling all the industrial field | Process control, automation | Robotics, controllers, CNC |

| Mechanical engineering | Focuses on the development and operation of energy systems, transport systems, manufacturing systems, machines and control systems | Dynamics, kinematics, statics, fluid mechanics, materials science, metallurgy, strength of materials, thermodynamics, heat transfer, mechanics, mechatronics, manufacturing engineering, control engineering | Cars, airplanes, machines, power generation, spacecraft, buildings, consumer goods, manufacturing, HVAC |

| Metallurgical engineering/materials engineering | Focuses on extraction of metals from its ores and development of new materials | Material science, thermodynamics, extraction of metals, physical metallurgy, mechanical metallurgy, nuclear materials, steel technology | Iron, steel, polymers, ceramics, metals |

| Mining engineering | Focuses on the use of applied science and technology to extract various minerals from the earth, not to be confused with metallurgical engineering, which deals with mineral processing of various ores after they have already been mined | Rock mechanics, geostatistics, soil mechanics, control engineering, geophysics, fluid mechanics, drilling and blasting | Gold, silver, coal, iron ore, potash, limestone, diamond, rare-earth element, bauxite, copper |

| Software engineering | Focuses on the design and development of software systems | Computer science, information theory, systems engineering, formal language | Application software, Mobile apps, Websites, operating systems, embedded systems, real-time computing, video games, virtual reality, AI software, edge computing, distributed systems, computer vision, music sequencers, digital audio workstations, software synthesizers, robotics, CGI, medical software, computer-assisted surgery, Internet of things, avionics software, computer simulation, quantum programming, satellite navigation software, antivirus software, electronic design automation, computer-aided design, self-driving cars, educational software |

Ethics[edit]

Engineers have obligations to the public, their clients, employers, and the profession. Many engineering societies have established codes of practice and codes of ethics to guide members and inform the public at large. Each engineering discipline and professional society maintains a code of ethics, which the members pledge to uphold. Depending on their specializations, engineers may also be governed by specific statute, whistleblowing, product liability laws, and often the principles of business ethics.[15][16][17]

Some graduates of engineering programs in North America may be recognized by the iron ring or Engineer’s Ring, a ring made of iron or stainless steel that is worn on the little finger of the dominant hand. This tradition began in 1925 in Canada with The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, where the ring serves as a symbol and reminder of the engineer’s obligations to the engineering profession. In 1972, the practice was adopted by several colleges in the United States including members of the Order of the Engineer.

Education[edit]

Most engineering programs involve a concentration of study in an engineering specialty, along with courses in both mathematics and the physical and life sciences. Many programs also include courses in general engineering and applied accounting. A design course, often accompanied by a computer or laboratory class or both, is part of the curriculum of most programs. Often, general courses not directly related to engineering, such as those in the social sciences or humanities, also are required.

Accreditation is the process by which engineering programs are evaluated by an external body to determine if applicable standards are met. The Washington Accord serves as an international accreditation agreement for academic engineering degrees, recognizing the substantial equivalency in the standards set by many major national engineering bodies. In the United States, post-secondary degree programs in engineering are accredited by the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology.

Regulation[edit]

In many countries, engineering tasks such as the design of bridges, electric power plants, industrial equipment, machine design and chemical plants, must be approved by a licensed professional engineer. Most commonly titled professional engineer is a license to practice and is indicated with the use of post-nominal letters; PE or P.Eng. These are common in North America, as is European engineer (EUR ING) in Europe. The practice of engineering in the UK is not a regulated profession but the control of the titles of chartered engineer (CEng) and incorporated engineer (IEng) is regulated. These titles are protected by law and are subject to strict requirements defined by the Engineering Council UK. The title CEng is in use in much of the Commonwealth.

Many skilled and semi-skilled trades and engineering technicians in the UK call themselves engineers. A growing movement in the UK is to legally protect the title ‘Engineer’ so that only professional engineers can use it; a petition[18] was started to further this cause.

In the United States, engineering is a regulated profession whose practice and practitioners are licensed and governed by law. Licensure is generally attainable through combination of education, pre-examination (Fundamentals of Engineering exam), examination (professional engineering exam),[19] and engineering experience (typically in the area of 5+ years). Each state tests and licenses professional engineers. Currently, most states do not license by specific engineering discipline, but rather provide generalized licensure, and trust engineers to use professional judgment regarding their individual competencies; this is the favoured approach of the professional societies. Despite this, at least one of the examinations required by most states is actually focused on a particular discipline; candidates for licensure typically choose the category of examination which comes closest to their respective expertise. In the United States, an «industrial exemption» allows businesses to employ employees and call them an «engineer», as long as such individuals are under the direct supervision and control of the business entity and function internally related to manufacturing (manufactured parts) related to the business entity, or work internally within an exempt organization. Such person does not have the final authority to approve, or the ultimate responsibility for, engineering designs, plans, or specifications that are to be incorporated into fixed works, systems, or facilities on the property of others or made available to the public. These individuals are prohibited from offering engineering services directly to the public or other businesses, or engage in practice of engineering unless the business entity is registered with the state’s board of engineering, and the practice is carried on or supervised directly only by engineers licensed to engage in the practice of engineering.[20] In some instances, some positions, such as a «sanitation engineer», does not have any basis in engineering sciences. Although some states require a BS degree in engineering accredited by the Engineering Accreditation Commission (EAC) of Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) with no exceptions, about two thirds of the states accept BS degrees in engineering technology accredited by the Engineering Technology Accreditation Commission (ETAC) of ABET to become licensed as professional engineers. Each state has different requirements on years of experience to take the Fundamentals of Engineering (FE) and Professional Engineering (PE) exams. A few states require a graduate MS in engineering to sit for the exams as further learning. After seven years of working after graduation, two years of responsibility for significant engineering work, continuous professional development, some highly qualified PEs are able to become International Professional Engineers Int(PE). These engineers must meet the highest level of professional competencies and this is a peer reviewed process. Once the IntPE title is awarded, the engineer can gain easier admission to national registers of a number of members jurisdictions for international practice.[21]

In Canada, engineering is a self-regulated profession. The profession in each province is governed by its own engineering association. For instance, in the Province of British Columbia an engineering graduate with four or more years of post graduate experience in an engineering-related field and passing exams in ethics and law will need to be registered by the Association for Professional Engineers and Geoscientists (APEGBC)[22] in order to become a Professional Engineer and be granted the professional designation of P.Eng allowing one to practice engineering.

In Continental Europe, Latin America, Turkey, and elsewhere the title is limited by law to people with an engineering degree and the use of the title by others is illegal. In Italy, the title is limited to people who hold an engineering degree, have passed a professional qualification examination (Esame di Stato) and are enrolled in the register of the local branch of National Associations of Engineers (a public body). In Portugal, professional engineer titles and accredited engineering degrees are regulated and certified by the Ordem dos Engenheiros. In the Czech Republic, the title «engineer» (Ing.) is given to people with a (masters) degree in chemistry, technology or economics for historical and traditional reasons. In Greece, the academic title of «Diploma Engineer» is awarded after completion of the five-year engineering study course and the title of «Certified Engineer» is awarded after completion of the four-year course of engineering studies at a Technological Educational Institute (TEI).

Perception[edit]

Archimedes regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity.

The perception and definition of the term ‘engineer’ varies across countries and continents.

Corporate culture[edit]

In companies and other organizations, there is sometimes a tendency to undervalue people with advanced technological and scientific skills compared to celebrities, fashion practitioners, entertainers, and managers. In his book, The Mythical Man-Month,[23] Fred Brooks Jr says that managers think of senior people as «too valuable» for technical tasks and that management jobs carry higher prestige. He tells how some laboratories, such as Bell Labs, abolish all job titles to overcome this problem: a professional employee is a «member of the technical staff.» IBM maintains a dual ladder of advancement; the corresponding managerial and engineering or scientific rungs are equivalent. Brooks recommends that structures need to be changed; the boss must give a great deal of attention to keeping managers and technical people as interchangeable as their talents allow.

Europe[edit]

As of 2022, thirty two countries in Europe (including nearly all 27 countries of the EU) now recognise the title of ‘European Engineer’ which permits the use of the pre-nominal title of «EUR ING» (always fully capitalised). Each country sets its own precise qualification requirement for the use of the title (though they are all broadly equivalent). Holding the requisite qualification does not afford automatic entitlement. The title has to be applied for (and the appropriate fee paid). The holder is entitled to use the title in their passport. EUR INGs are allowed to describe themselves as professionally qualified engineers and practise as such in any of the 32 participating countries including those where the title of engineer is regulated by law.[citation needed]

UK[edit]

British school children in the 1950s were brought up with stirring tales of «the Victorian Engineers», chief among whom were Brunel, Stephenson, Telford, and their contemporaries. In the UK, «engineering» has more recently been erroneously styled as an industrial sector consisting of employers and employees loosely termed «engineers» who include tradespeople. However, knowledgeable practitioners reserve the term «engineer» to describe a university-educated professional of ingenuity represented by the Chartered (or Incorporated) Engineer qualifications.[24] A large proportion of the UK public incorrectly thinks of «engineers» as skilled tradespeople or even semi-skilled tradespeople with a high school education. Also, many UK skilled and semi-skilled tradespeople falsely style themselves as «engineers». This has created confusion in the eyes of some members of the public in understanding what professional engineers actually do, from fixing car engines, television sets and refrigerators (technicians, handymen) to designing and managing the development of aircraft, spacecraft, power stations, infrastructure and other complex technological systems (engineers).[citation needed]

France[edit]

In France, the term ingénieur (engineer) is not a protected title and can be used by anyone who practices this profession.[25]

However, the title ingénieur diplomé (graduate engineer) is an official academic title that is protected by the government and is associated with the Diplôme d’Ingénieur, which is a renowned academic degree in France. Anyone misusing this title in France can be fined a large sum and jailed, as it is usually reserved for graduates of French engineering grandes écoles. Engineering schools which were created during the French revolution have a special reputation among the French people, as they helped to make the transition from a mostly agricultural country of late 18th century to the industrially developed France of the 19th century. A great part of 19th-century France’s economic wealth and industrial prowess was created by engineers that have graduated from École Centrale Paris, École des Mines de Paris, École polytechnique or Télécom Paris. This was also the case after WWII when France had to be rebuilt. Before the «réforme René Haby» in the 1970s, it was very difficult to be admitted to such schools, and the French ingénieurs were commonly perceived as the nation’s elite. However, after the Haby reform and a string of further reforms (Modernization plans of French universities), several engineering schools were created which can be accessed with relatively lower competition.

In France, engineering positions are now shared between the ingénieurs diplomés graduating from engineering grandes écoles; and the holders of a Master’s degree in Science from public universities.

Italy[edit]

In Italy, only people who hold a formal engineering qualification of at least a bachelor’s degree are permitted to describe themselves as an engineer. So much so that people holding such qualifications are entitled to use the pre-nominal title of «Ingegnere» (or «Ingegnera» if female — in both cases often abbreviated to «Ing.») in lieu of «Signore», «Signorina» or «Signora» (Mr, Miss and Mrs respectively) in the same manner as someone holding a doctorate would use the pre-nominal title «Doctor».

North America[edit]

Canada[edit]

In Canada, engineering is a regulated profession whose practice and practitioners are licensed and governed by law.[26] Licensed professional engineers are referred to as P.Eng. Many Canadian engineers wear an Iron Ring.[27]

In all Canadian provinces, the title «Professional Engineer» is protected by law and any non-licensed individual or company using the title is committing a legal offence and is subject to fines and restraining orders.[28] Contrary to insistence from the Professional Engineers Ontario («PEO») and Engineers Canada, use of the title «Engineer» itself has been found by Canadian law to be acceptable by those not holding P.Eng. titles.[29][30]

The title of engineer is not exclusive to P.Eng titles. The title of Engineer is commonly held by «Software Engineer»,[31] the Canadian Military as various ranks and positions,[32] railway locomotive engineers,[33] and Aircraft Maintenance Engineers (AME), all of which do not commonly hold a P.Eng. designation.

United States[edit]

In the United States, the practice of professional engineering is highly regulated and the title «professional engineer» is legally protected, meaning that it is unlawful to use it to offer engineering services to the public unless permission, certification or other official endorsement is specifically granted by that state through a professional engineering license.[34]

Spanish-speaking countries[edit]

Certain Spanish-speaking countries follow the Italian convention of engineers using the pre-nominal title, in this case «ingeniero» (or «ingeniera» if female). Like in Italy, it is usually abbreviated to «Ing.» In Spain this practice is not followed.

The engineering profession enjoys high prestige in Spain, ranking close to medical doctors, scientists and professors, and above judges, journalists or entrepreneurs, according to a 2014 study.[35]

Asia and Africa[edit]

In the Indian subcontinent, Russia, Middle East, Africa, and China, engineering is one of the most sought after undergraduate courses, inviting thousands of applicants to show their ability in highly competitive entrance examinations.

In Egypt, the educational system makes engineering the second-most-respected profession in the country (after medicine); engineering colleges at Egyptian universities requires extremely high marks on the General Certificate of Secondary Education (Arabic: الثانوية العامة al-Thānawiyyah al-`Āmmah)—on the order of 97 or 98%—and are thus considered (along with the colleges of medicine, natural science, and pharmacy) to be among the «pinnacle colleges» (كليات القمة kullīyāt al-qimmah).

In the Philippines and Filipino communities overseas, engineers who are either Filipino or not, especially those who also profess other jobs at the same time, are addressed and introduced as Engineer, rather than Sir/Madam in speech or Mr./Mrs./Ms. (G./Gng./Bb. in Filipino) before surnames. That word is used either in itself or before the given name or surname.

See also[edit]

- Building engineer

- Engineer’s degree

- Engineers Without Borders

- European Engineer

- Greatest Engineering Achievements

- History of engineering

- List of Bangladeshi engineers

- List of engineering branches

- List of engineers

- List of fictional scientists and engineers

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Manual Labor (2006). «Engineers». Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2006–07 Edition (via Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- ^ National Society of Professional Engineers (2006). «Frequently Asked Questions About Engineering». Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 21 September 2006. «Science is knowledge based on our observed facts and tested truths arranged in an orderly system that can be validated and communicated to other people. Engineering is the creative application of scientific principles used to plan, build, direct, guide, manage, or work on systems to maintain and improve our daily lives.»

- ^ Pevsner, N. (1942). «The Term ‘Architect’ in the Middle Ages». Speculum. 17 (4): 549–562. doi:10.2307/2856447. JSTOR 2856447. S2CID 162586473.

- ^ Oxford Concise Dictionary, 1995

- ^ «engineer». Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010. Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010. Oxford University Press. 22 October 2011

- ^ Steen Hyldgaard Christensen, Christelle Didier, Andrew Jamison, Martin Meganck, Carl Mitcham, and Byron Newberry Springer. Engineering Identities, Epistemologies and Values: Engineering Education and Practice in Context, Volume 2, p. 170, at Google Books

- ^ A. Eide, R. Jenison, L. Mashaw, L. Northup. Engineering: Fundamentals and Problem Solving. New York City: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.,2002

- ^ a b c Robinson, M. A. (2010). «An empirical analysis of engineers’ information behaviors». Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 61 (4): 640–658. doi:10.1002/asi.21290.

- ^ Baecher, G.B.; Pate, E.M.; de Neufville, R. (1979). «Risk of dam failure in benefit/cost analysis». Water Resources Research. 16 (3): 449–456. Bibcode:1980WRR….16..449B. doi:10.1029/wr016i003p00449.

- ^ Hartford, D.N.D. and Baecher, G.B. (2004) Risk and Uncertainty in Dam Safety. Thomas Telford

- ^ International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD) (2003) Risk Assessment in Dam Safety Management. ICOLD, Paris

- ^ British Standards Institution (BSIA) (1991) BC 5760 Part 5: Reliability of systems equipment and components – Guide to failure modes effects and criticality analysis (FMEA and FMECA).

- ^ a b Robinson, M. A. (2012). «How design engineers spend their time: Job content and task satisfaction». Design Studies. 33 (4): 391–425. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2012.03.002.

- ^ Robinson, M. A.; Sparrow, P. R.; Clegg, C.; Birdi, K. (2005). «Design engineering competencies: Future requirements and predicted changes in the forthcoming decade». Design Studies. 26 (2): 123–153. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2004.09.004.

- ^ American Society of Civil Engineers (2006) [1914]. Code of Ethics. Reston, Virginia, USA: ASCE Press. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Institution of Civil Engineers (2009). Royal Charter, By-laws, Regulations and Rules. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ National Society of Professional Engineers (2007) [1964]. Code of Ethics (PDF). Alexandria, Virginia, USA: NSPE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ «Make ‘Engineer’ a protected title». Petitions – UK Government and Parliament.

- ^ [1] NCEES is a national nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing professional licensure for engineers and surveyors.

- ^ «Texas Engineering and Land Surveying Practice Acts and Rules Concerning Practice and Licensure» (PDF). texas.gov. The State of Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ «NCEES International Registry for Professional Engineers». NCEES. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ «Engineers and Geoscientists BC». egbc.ca. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering, p119 (see also p242), Frederick P. Brooks, Jr., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2nd ed. 1995, pub. Addison-Wesley

- ^ Burns, Corrinne (19 September 2013). «Are you an engineer? Then don’t be shy about it | Are you an engineer? Then don’t be shy about it | Corrinne Burns». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Pourrat, Yvonne (1 April 2011). «Perception of French students in engineering about the ethics of their profession and implications for engineering education». ResearchGate. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ «About Engineers Canada». engineerscanada.ca. Engineers Canada. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ «The Calling of an Engineer», The Corporation of the Seven Wardens, Retrieved November 29, 2022

- ^ «Engineering licensing body clarifies the use of the term «engineer» following reported dismissal of Hydro One employee». peo.on.ca. Professional Engineers Ontario. 13 May 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Assn. of Professional Engineers, Geologists and Geophysicists of Alberta (Council of) v. Merhej, 2003 ABCA 360 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/1g18s>, retrieved on 2022-11-29

- ^ Section (3)(f) of the Professional Engineer Act of Ontario does not prevent people form using the title Engineer. (3) Subsections (1) and (2) do not apply to prevent a person, (f) from using the title “engineer” or an abbreviation of that title in a manner that is authorized or required by an Act or regulation. It does prevent Professional Engineer title under section 2 of the act.

- ^ «Computer Software Engineer in Canada | Job requirements — Job Bank». www.jobbank.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ «Who Are We? | Canadian Military Engineers». cmea-agmc.ca. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ «Train Engineer in Canada | Labour Market Facts and Figures — Job Bank». www.jobbank.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ «What is a PE?». National Society of Professional Engineers. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ Lobera, Josep; Torres Albero, Cristóbal (2015). «El prestigio social de las profesiones tecnocientíficas». Percepción social de la Ciencia y la Tecnología 2014 (PDF) (in Spanish). FECYT. pp. 218–240. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

External links[edit]

Look up engineer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Engineers at Wikimedia Commons

English word engineer comes from Latin genitus, Latin inganno (I trick, deceive.), Latin gignere, Latin ingratus (Thankless. Ungrateful. Unpleasant, disagreeable.)

Detailed word origin of engineer

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| genitus | Latin (lat) | |

| inganno | Latin (lat) | I trick, deceive. |

| gignere | Latin (lat) | |

| ingratus | Latin (lat) | Thankless. Ungrateful. Unpleasant, disagreeable. |

| ingenium | Latin (lat) | A man of genius, a genius. Disposition, temper, inclination. Innate or natural quality, natural character; nature. Intelligence, natural capacity. Talent. |

| engin | Old French (842-ca. 1400) (fro) | Intelligence. Invention; ingenuity; creativity. Machine; device; contraption. Ruse; trickery; deception. |

| ingeniarius | Malayalam (mal) | |

| engignier | Old French (842-ca. 1400) (fro) | To create; to make. To trick; to deceive. |

| engineour | Middle English (1100-1500) (enm) | |

| engineer | English (eng) | (transitive) To alter or construct something by means of genetic engineering.. (transitive) To control motion of substance; to change motion.. (transitive) To design, construct or manage something as an engineer.. (transitive) To plan or achieve some goal by contrivance or guile; to wangle or finagle. (Philippines) A title given to an engineer.. (chiefly, American) A person who controls […] |

Words with the same origin as engineer

Nearly all the manmade objects that surround you result from the efforts of engineers. Just think of all that went into making the chair upon which you sit. Its metal components came from ores extracted from mines designed by mining engineers. The metal ores were refined by metallurgical engineers in mills that civil and mechanical engineers helped build. Mechanical engineers designed the chair components as well as the machines that fabricated them. The polymers and fabrics in the chair were probably derived from oil that was produced by petroleum engineers and refined by chemical engineers. The assembled chair relived to you in a truck that was designed by mechanical, aerospace, and electrical engineers, in plants that industrial engineers optimized to make the best use of space, capital, and labor. The roads on which the truck traveled were designed and constructed by civil engineers.

Obviously, engineers play an important role in bringing ordinary objects to markets. In addition, engineers are key players in some of the most existing ventures of humankind.

WHAT ARE ENGINEERS?

Engineers are individuals who combine knowledge of science, mathematics, and economics to solve technical problems that confront society. It is our practical knowledge that distinguishes engineers from scientists for they too are masters of science and mathematics. In another word, we described engineering as “the art of doing …well with one dollar, which any bungler can do with two”.

Although engineers must be very cost-conscious when making ordinary objects for consumer use, some engineering projects are not governed strictly by cost considerations. Thus, engineers can be viewed as problem solvers who assemble the necessary resources to achieve a clearly defined technical objective.

Engineer: Origins of the Word

The root of the word engineer derives from the engine and ingenious, both of which come from the Latin root in generare, meaning “to create”. In early English, the verb engine meant “to contrive” or “to create”.

The word enginner traces to around A.D 200, when the Christian author Tertullian described a Roman attack on the Carthaginians using a battering ram described by him as an ingenium, an ingenious invention. Later, around A.D. 1200, a person responsible for developing such ingenious engines of war ( battering rams, floating bridges, assault towers, catapults, etc) was dubbed an ingeniator. In the 1500s, as the meaning of “engines” was broadened, an engineer was a person who made engines. Today, we would classify a builder of engines as a mechanical engineer, because an engineer, in the more general sense, is “a person who applies science, mathematics, and economics to meet the needs of humankind”.

The Engineers as problem solvers

Engineers are problem solvers. Given the historical roots of the word engineer, we can expand this to say that engineers are ingenious problem solvers.

In a sense, all humans are engineers. A child playing with building blocks who learns how to construct a taller structure is doing engineering. A secretary who stabilizes a wobbly desk by inserting a piece of cardboard under the short leg has engineered a solution to the problem.

Early in human history, there were no formal schools to teach engineering. Engineering was performed by those who had a gift for manipulating the physical world to achieve a practical goal. Often, it would be learned through an apprenticeship with experienced practitioners. This approach resulted in some remarkable accomplishments.

Current engineering education emphasizes mathematics, science, and economics, making engineering “applied science”. Historically, this is was not true: rather, engineers were largely guided by intuition and experience gained either personally or vicariously. For example, many great buildings, aqueducts, tunnels, mines, and bridges were constructed prior to the early 1700s, when the first scientific foundations were laid in engineering. Engineers often must solve problems without even understanding the underlying theory. Certainly, engineers benefit from scientific theory, but sometimes the solution is required before the theory can catch up to the practice. For example, theorists are still trying to fully explain high-temperature superconductors while engineers are busy forming flexible wires out of these new materials that may be used in future generations of electrical devices.

THE TECHNOLOGY TEAM

Modern technical challenges are seldom met by the lone engineer. Technology development is a complex process involving the coordinated efforts of a technology team consisting of:

- Scientists, study nature in order to advance human knowledge. Although some scientists work on industry problems, others have successful careers publishing results that may not have immediate practical applications. Typical degree requirements: BS, MS, Ph.D.

- Engineers, who apply their knowledge of science, mathematics, and economics to develop useful devices, structures, and processes. Typical degree requirements: BS, MS, Ph.D.

- Technologists, apply science, and mathematics to well-defined problems that generally do not require the depth of knowledge possessed by engineers and scientists. Typical degree requirement: BS.

- Technicians, work closely with engineers and scientists to accomplish specific tasks such as drafting, laboratory procedures, and model buildings. Typical degree requirement: two-year associate’s degree.

- Artisans, have the manual skills (welding, machining, carpentry) to construct devices specified by scientists, technologists, and technicians. Typical degree requirement: high school diploma plus experience.

Successful teamwork results in accomplishments larger than can be produced by individual team members. There is magic when a team coalesces and each member builds off of the ideas and enthusiasm of teammates. For this magic to occur and to produce output that surpasses individual efforts, several characteristics must be:

- Mutual respect for the ideas of fellow team members.

- The ability of team members to transmit and receive the ideas of the team.

- The ability to lay aside criticism of an idea during the early formulation of of solutions to a problem.

- The ability to build on initial or weakly formed ideas.

- The skill to accurately criticize a proposed solution and analyze for both strengths and weaknesses.

- The patience to try again when an idea fails or a solution is incomplete.

Engineering functions

Regardless of their discipline, engineers can be classified by the functions they perform:

- Research engineers, search for new knowledge to solve difficult problems that do not have readily apparent solutions. They require the greatest training, generally an MS or Ph.D. degree.

- Development engineers, apply existing and new knowledge to develop prototypes of new devices, structures, and processes.

- Design engineers, apply the results of research and development engineers to produce detailed designs of devices, structures, and processes that will be used by the public.

- Production engineers are concerned with specifying production schedules, determining new raw materials availability, and optimizing assembly lines to mass-produce the devices conceived by design engineers.

- Testing engineers, perform tests on engineered products to determine the reliability and suitability for particular applications.

- Construction engineers, build large structures.

- Operation engineers, run and maintain production facilities such as factories and chemical plants.

- Sales engineers, have the technical background required to sell technical products.

- Managing engineers, are needed in the industry to coordinate the activities of the technology team.

- Consulting engineers, are specialists who are called upon by companies to supplement their in-house engineering talent.

- Teaching engineers, educate other engineers in the fundamentals of each engineering discipline.

To illustrate the roles of engineering disciplines and functions, consider all the steps required to produce a new battery for automotive propulsion. (The probable engineering discipline is in parentheses and the engineering function is in italics.) A research engineer (a chemical engineer) performs fundamental laboratory studies on new materials that are possible candidates for a rechargeable battery that is lightweight but stores much energy. The development engineer (chemical or electrical engineer) reviews the results of the research engineer and selects a few candidates for further development. She constructs some battery prototypes and tests them for such properties as a maximum number of recharge cycles, voltage output at various temperatures, the effect of discharge rate on battery life, and corrosion. If the development engineer lacks expertise in corrosion, the company would temporarily hire a consulting engineer (chemical, mechanical or materials engineer) to solve a corrosion problem.

When the development engineer has finally amassed sufficient information, the design engineer (mechanical engineer) designs each battery model that will be produced by the company. He must specify the exact composition and dimension of each component and how each component will be manufactured. A construction engineer (civil engineer) erects the building in which the batteries will be manufactured and a production engineer (industrial engineer) designs the production line (e.g. machine tools, assembly areas) to mass-produce the new battery.

Operations engineers (mechanical or industrial engineers) operate the production line and ensure that it is properly maintained. Once the production line is operating, testing engineers (industrial or electrical engineers) randomly select batteries and test them to ensure that they meet company specifications. Sales engineers (electrical or mechanical engineers)meet with automotive companies to explain the advantages of their company’s battery and answer technical questions. Managing engineers (any discipline) make decisions about financing plant expansions, product pricing, hiring new personnel, and setting company goals. All of these engineers were trained by teaching engineers (many disciplines) in college.

In this example, the engineering disciplines that satisfy each function are unique to the project. Other projects would require the coordinated efforts of other engineering disciplines. Also, the disciplines selected for this project are an idealization. A company might not have the ideal mix of engineers required by a project and would expect its existing engineering staff to adapt to the needs of the project. After many years, engineers become cross-trained in other disciplines, so it becomes difficult to classify them by the disciplines, they studied in college. An engineer who wishes to stay employed must be adaptable, which means being well acquainted with the fundamentals of other engineering disciplines.

Popular on AziziKatepa Right Now!

-

DAMPNESS PROOFING AND CAUSES OF DAMPNESS

-

Best Engineering Universities In The US 2023

-

Best Architecture Schools In The US 2022 | Architecture Schools Rankings

-

WHAT IS A WALL CLADDING?, DESIGN CRITERIA, MATERIAL, AND TYPES

INTELLIGENT WORK FORUMS

FOR ENGINEERING PROFESSIONALS

Contact US

Thanks. We have received your request and will respond promptly.

Log In

Come Join Us!

Are you an

Engineering professional?

Join Eng-Tips Forums!

- Talk With Other Members

- Be Notified Of Responses

To Your Posts - Keyword Search

- One-Click Access To Your

Favorite Forums - Automated Signatures

On Your Posts - Best Of All, It’s Free!

*Eng-Tips’s functionality depends on members receiving e-mail. By joining you are opting in to receive e-mail.

Posting Guidelines

Promoting, selling, recruiting, coursework and thesis posting is forbidden.

Students Click Here

Origin of the word ‘engineer’?Origin of the word ‘engineer’?(OP) 2 Aug 05 04:31 Does anyone know the origin of the word ‘engineer’? Red Flag SubmittedThank you for helping keep Eng-Tips Forums free from inappropriate posts. |

ResourcesLearn methods and guidelines for using stereolithography (SLA) 3D printed molds in the injection molding process to lower costs and lead time. Discover how this hybrid manufacturing process enables on-demand mold fabrication to quickly produce small batches of thermoplastic parts. Download Now Examine how the principles of DfAM upend many of the long-standing rules around manufacturability — allowing engineers and designers to place a part’s function at the center of their design considerations. Download Now Metal 3D printing has rapidly emerged as a key technology in modern design and manufacturing, so it’s critical educational institutions include it in their curricula to avoid leaving students at a disadvantage as they enter the workforce. Download Now This ebook covers tips for creating and managing workflows, security best practices and protection of intellectual property, Cloud vs. on-premise software solutions, CAD file management, compliance, and more. Download Now |

Join Eng-Tips® Today!

Join your peers on the Internet’s largest technical engineering professional community.

It’s easy to join and it’s free.

Here’s Why Members Love Eng-Tips Forums:

Talk To Other Members

- Notification Of Responses To Questions

- Favorite Forums One Click Access

- Keyword Search Of All Posts, And More…

Register now while it’s still free!

Already a member? Close this window and log in.

Join Us Close

English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The noun is derived from:[1]

- Middle English enginour (“one who designs, constructs, or operates military works for attack or defence, etc.; machine designer”) [and other forms],[2] from Anglo-Norman enginour, engigneour [and other forms], and Middle French and Old French engigneor, engigneour, engignier (“one who designs, constructs, or operates military works for attack or defence; architect; carpenter; craftsman; designer; planner; one who deceives or schemes”) (modern French ingénieur), from engin (“contraption, device; machine; invention; creativity, ingenuity; intelligence; deception, ruse, trickery”) + -eor, -or (suffix forming agent nouns); engin is derived from Latin ingenium (“innate or natural quality, nature; intelligence, natural capacity; ability, skill, talent; (Medieval Latin) engine; machine”), from in- (prefix meaning ‘in, inside, within’) + gignere (the present active infinitive of gignō (“to bear, beget, give birth to; to cause, produce, yield”), ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *ǵenh₁- (“to beget, give birth to; to produce”)) + -ium (suffix forming abstract nouns); and

- from engine + -er (occupational suffix); and

- from engine + -eer (suffix forming nouns denoting people associated with, concerned with, or engaged in specified activities), possibly modelled after Middle French ingénieur (a variant of Middle French, Old French engigneour; see above), and Italian ingegniere (“engineer”) (obsolete; modern Italian ingegnere).

The verb is derived from the noun.[3]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /ˌɛn(d)ʒɪˈnɪə/

- (General American) IPA(key): /ˌɛnd͡ʒɪˈnɪ(ə)ɹ/

- Rhymes: -ɪə(ɹ)

- Hyphenation: en‧gin‧eer

Noun[edit]

engineer (plural engineers)

- (military, also figuratively)

- A soldier engaged in designing or constructing military works for attack or defence, or other engineering works.

-

c. 1599–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke: […] (Second Quarto), London: […] I[ames] R[oberts] for N[icholas] L[ing] […], published 1604, →OCLC, [Act III, scene iv]:

-

For tis the ſport to haue the enginer / Hoiſt with his ovvne petar, an’t ſhall goe hard / But I vvill delue one yeard belovve their mines, / And blovve them at the Moone: […]

- For it’s amusing to have the engineer / Hoisted into the sky with his own explosive, and if I’m lucky / I will dig one yard below their mines, / And blow them towards the Moon: […]

-

-

1625, Edmund Scot, “A Discourse of Iaua, and of the First English Factorie there, with Diuers Indian, English, and Dutch Occurrents, […]”, in [Samuel] Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes. […], 1st part, London: […] William Stansby for Henrie Fetherstone, […], →OCLC, 3rd book, § IIII, page 173:

-

Novv he began another Trade, and became an Ingenor, hauing got eight Fire-brands of hell more to him, onely of purpoſe to ſet our houſe a fire.

-

-

1627, Michaell Drayton [i.e., Michael Drayton], “The Battaile of Agin Court”, in The Battaile of Agincourt. […], London: […] A[ugustine] M[atthews] for VVilliam Lee, […], published 1631, →OCLC, page 12:

-

Cannons vpon their Carriage mounted are, / VVhole Battery Fraunce muſt feele vpon her VValls, / The Engineer prouiding the Petar, / To breake the ſtrong Percullice, and the Balls / Of VVild fire deuis’d to throvv from farre, / To burne to ground their Pallaces and Halls: […]

-

-

1794 May 28, Edmund Burke, “Trial of Warren Hastings, Esq. Wednesday, 28th May 1794. First Day of Reply.”, in [Walker King], editor, The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, volume XV, new edition, London: […] [Luke Hansard & Sons] for C[harles] & J[ohn] Rivington, […], published 1827, →OCLC, pages 63–64:

-

But your Lordships must have heard with astonishment, that, upon points of law, relative to the tenure of lands, instead of producing any law document or authority on the usages and local customs of the country, he has referred to officers in the army, colonels of artillery and engineers, to young gentlemen just come from school, not above three or four years in the country.

-

-

1866, C[harles] Kingsley, “How Earl Godwin’s Widow Came to St. Omer”, in Hereward the Wake, “Last of the English.” […], volume I, London; Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Macmillan and Co., →OCLC, page 341:

-

And she began praising Hereward’s valour, his fame, his eloquence, his skill as a general and engineer; and when he suggested, smiling, that he was an exile and an outlaw, she insisted he was all the fitter from that very fact.

-

-

- (obsolete) A soldier in charge of operating a weapon; an artilleryman, a gunner.

-

1599, [Thomas Heywood], “The Second Part […]”, in The First and Second Partes of King Edvvard the Fourth. […], London: […] I. W. for Iohn Oxenbridge, […], →OCLC; reprinted Philadelphia, Pa.; New York, N.Y.: The Rosenbach Company, 1922, →OCLC:

-

This is hard welcome, but it was not you, / At whom the fatal enginer did ayme, / My breaſt the levell was, though you the marke, / In which conſpiracie anſwere me Duke, / Is not thy ſoule as guiltie as the Earles?

-

-

[1633], George Herbert, “The Church-porch”, in [Nicholas Ferrar], editor, The Temple: Sacred Poems, and Private Ejaculations, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: […] Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel; and are to be sold by Francis Green, […], →OCLC; reprinted London: Elliot Stock, […], 1885, →OCLC, page 9:

-

Wit’s an unruly engine, wildly ſtriking / Sometimes a friend, ſometimes the engineer.

-

-

1716 March 6 (Gregorian calendar), Joseph Addison, “The Free-holder: No. 19. Friday, February 24. [1716.]”, in The Works of the Right Honourable Joseph Addison, Esq; […], volume IV, London: […] Jacob Tonson, […], published 1721, →OCLC, page 426:

-

An Author who points his ſatyr at a great man, is to be looked upon in the ſame view with the engineer who ſignalized himſelf by this ungenerous practice.

-

-

1855 July 4, Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Brooklyn, New York, N.Y.: [James and Andrew Rome], →OCLC, page v, column 1:

-

In war he [the poet] is the most deadly force of the war. Who recruits him recruits horse and foot … he fetches parks of artillery the best that engineer ever knew.

-

-

- A soldier engaged in designing or constructing military works for attack or defence, or other engineering works.

- (by extension)

- A person professionally engaged in the technical design and construction of large-scale private and public works such as bridges, buildings, harbours, railways, roads, etc.; a civil engineer.

-

1606, C[aius, i.e., Gaius] Suetonius Tranquillus, “The Historie of Flavius Vespatianus Augustus”, in Philemon Holland, transl., The Historie of Twelve Cæsars Emperours of Rome. […], London: […] [Humphrey Lownes and George Snowdon] for Matthew Lownes, →OCLC, section 17, page 249:

-

[T]o an Enginer alſo, vvho promiſed to bring into the Capitoll huge Columnes vvith ſmall charges, hee gave for his deviſe no meane revvard; and releaſed him his labour in performing that vvorke, ſaying vvithall by vvay of preface, That he ſhould ſuffer him to feed the poore commons.

-

-

- Originally, a person engaged in designing, constructing, or maintaining engines or machinery; now (more generally), a person qualified or professionally engaged in any branch of engineering, or studying to do so.

-

1598, John Florio, “Macanopoietico”, in A Worlde of Words, or Most Copious, and Exact Dictionarie in Italian and English, […], London: […] Arnold Hatfield for Edw[ard] Blount, →OCLC, page 209, column 3:

-

Macanopoietico, an inginer, an engine-maker.

-

-

1623 November 8 (Gregorian calendar; first performance), Thomas Middleton, “The Triumphs of Integrity”, in A[rthur] H[enry] Bullen, editor, The Works of Thomas Middleton […] (The English Dramatists), volume VII, London: John C. Nimmo […], published 1886, →OCLC, page 391:

-

[N]ear St. Laurence-Lane his lordship receives an entertainment from an unparalleled masterpiece of art, called the Crystal Sanctuary, styled by the name of the Temple of Integrity, […] and more to express the invention and the art of the engineer, as also for motion, variety, and the content of the spectators, this Crystal Temple is made to open in many parts, at fit and convenient times, and upon occasion of the speech; […]

-

-

- A person trained to operate an engine; an engineman.

- (chiefly historical) A person who operates a steam engine; specifically (nautical), a person employed to operate the steam engine in the engine room of a ship.

-

1856, R[alph] W[aldo] Emerson, “Wealth”, in English Traits, Boston, Mass.: Phillips, Sampson, and Company, →OCLC, pages 170–171:

-

The machinery [the steam engine] has proved, like the balloon, unmanageable, and flies away with the aeronaut. Steam, from the first, hissed and screamed to warn him; it was dreadful with its explosion, and crushed the engineer. The machinist has wrought and watched, engineers and firemen without number have been sacrificed in learning to tame and guide the monster.

-

-

1892, Walt Whitman, “Song of the Answerer”, in Leaves of Grass […], Philadelphia, Pa.: David McKay, publisher, […], →OCLC, part 1, page 136:

-

The engineer, the deck-hand on the great lakes, or on the Mississippi or St. Lawrence or Sacramento, or Hudson or Paumanok sound, claims him.

-

-

1902 January–March, Joseph Conrad, “Typhoon”, in George R. Halkett, editor, The Pall Mall Magazine, volume XXVI, London: Printed by Hazell, Watson & Viney, →OCLC, chapter IV, page 226, column 2:

-

One of the stokers was disabled, the others had given in, the second engineer and the donkey-man were firing-up. The third engineer was standing by the steam-valve. The engines were being tended by hand.

-

-

- (US, firefighting) A person who drives or operates a fire engine.

- (chiefly US, rail transport) A person who drives or operates a locomotive; a train driver.

- (chiefly historical) A person who operates a steam engine; specifically (nautical), a person employed to operate the steam engine in the engine room of a ship.

- Preceded by a qualifying word: a person who uses abilities or knowledge to manipulate events or people.

-

a political engineer

-

1727, [Daniel Defoe], “Of the Present Pretences of the Magicians: How They Defend Themselves; and Some Examples of Their Practice”, in A System of Magick; or, A History of the Black Art. […], London: […] J. Roberts […], →OCLC, page 319:

-

Now that I may not ſeem to paſs my Cenſure raſhly, I deſire that my more intelligent Readers will pleaſe to reduce the following things into Meaning, if they can, and favour us with the Interpretation; being ſome particular Account of the Life of this famous, religious Ingineer, for I know not what elſe to call him, and the Titles of ſome of his Books.

-

-

- (often derogatory) A person who formulates plots or schemes; a plotter, a schemer.

-

1593, Gabriel Harvey, Pierces Supererogation: Or A New Prayse of the Old Asse, London: […] Iohn Wolfe, →OCLC; republished as John Payne Collier, editor, Pierces Supererogation: Or A New Prayse of the Old Asse. A Preparative to Certaine Larger Discourses, Intituled Nashes S. Fame (Miscellaneous Tracts. Temp. Eliz. & Jac. I; no. 8), [London: [s.n.], 1870], →OCLC, page 10:

-

But the trimme ſilke-worme I looked for (as it were in a proper contempt of common fineneſſe) prooveth but a ſilly glow-woorme, and the dreadfull enginer of phraſes, in steede of thunderboltes, ſhooteth nothing but dogboltes and catboltes, and the homelieſt boltes of rude folly: […]

-

-

1603 (first performance; published 1605), Benjamin Jonson [i.e., Ben Jonson], “Seianus his Fall. A Tragœdie. […]”, in The Workes of Ben Jonson (First Folio), London: […] Will[iam] Stansby, published 1616, →OCLC, Act I, page 360:

-

No, Silius, wee are no good inginers; / VVe vvant the fine arts, & their thriuing vſe, / Should make vs grac’d, or fauour’d of the times: / […] / VVe burne with no black ſecrets, vvhich can make / Vs deare to the pale authors; or liue fear’d / Of their ſtill vvaking iealouſies, to raiſe / Our ſelues a fortune, by ſubuerting theirs.

-

-

1903 October, Jack London, “Coronation Day”, in The People of the Abyss, New York, N.Y.: The Macmillan Company; London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., →OCLC, page 144:

-

[T]he fighting men of England, masters of destruction, engineers of death!

-

-

- A person professionally engaged in the technical design and construction of large-scale private and public works such as bridges, buildings, harbours, railways, roads, etc.; a civil engineer.

Hyponyms[edit]

- aeroengineer

- aeronautical engineer

- aerospace engineer

- bioengineer

- certification engineer

- chemical engineer

- civil engineer

- combat engineer

- data engineer

- domestic engineer

- ecosystem engineer

- efficiency engineer

- electrical engineer

- electroengineer

- field applications engineer

- field engineer

- firmware engineer

- flight engineer

- genetic engineer

- gengineer

- geoengineer

- graduate engineer

- hardware engineer

- highway engineer

- HVAC engineer

- integration engineer

- knowledge engineer

- locating engineer

- locomotive engineer

- marine engineer

- mechanical engineer

- mechatronics engineer

- metallurgic engineer

- military engineer

- mining engineer

- naval engineer

- network engineer

- product engineer

- project engineer

- railroad engineer

- sanitary engineer

- social engineer

- software engineer

- sound engineer

- structural engineer

Derived terms[edit]

- engineeress

- engineerish

- engineerization

- engineer’s blue

- engineer’s chain

- engineer’s scale

- engr. (abbreviation)

- nonengineer

- nonengineering

[edit]

- genius

- ingeniosity

- ingenious

- ingeniously

- ingeniousness

- ingenuity

Descendants[edit]

- → Burmese: အင်ဂျင်နီယာ (anggyangniya)

- → Hawaiian: ʻenekinia

- → Hindi: इंजीनियर (iñjīniyar)

- → Japanese: エンジニア (enjinia)

- → Mon: အိန်ဂျေန်နဳယျာ

Translations[edit]

soldier engaged in designing or constructing military works for attack or defence, or other engineering works

person professionally engaged in the technical design and construction of large-scale private and public works such as bridges, buildings, harbours, railways, roads, etc. — see civil engineer

person engaged in designing, constructing, or maintaining engines or machinery; (more generally) a person qualified or professionally engaged in any branch of engineering, or studying to do so

- Abkhaz: анџьныр (andžnər)

- Afrikaans: ingenieur (af)

- Albanian: inxhinier (sq) m, mendis

- Arabic: مُهَنْدِس (ar) m (muhandis), مُهَنْدِسَة f (muhandisa)

- Egyptian Arabic: مهندس m (muhandis)

- Armenian: ինժեներ (hy) (inžener)

- Asturian: inxenieru m

- Azerbaijani: mühəndis (az)

- Belarusian: інжыне́р m (inžynjér)

- Bengali: প্রকৌশলী (prokōuśoli)

- Bulgarian: инжене́р (bg) m (inženér), инжене́рка f (inženérka)

- Burmese: အင်ဂျင်နီယာ (my) (anggyangniya)

- Catalan: enginyer (ca) m, enginyera (ca) f

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 工程師/工程师 (zh) (gōngchéngshī), 技師/技师 (zh) (jìshī)

- Min Nan: 技師/技师 (zh-min-nan) (ki-su), 工程師/工程师 (zh-min-nan) (kang-têng-su)

- Crimean Tatar: müendis

- Czech: inženýr (cs) m, inženýrka (cs) f

- Danish: ingeniør (da) c

- Dutch: ingenieur (nl) m or f

- Esperanto: inĝeniero

- Estonian: insener

- Faroese: verkfrøðingur m

- Finnish: insinööri (fi)

- French: ingénieur (fr) m, ingénieure (fr) f

- Galician: enxeñeiro (gl) m, enxeñeira f

- Georgian: ინჟინერი (inžineri)

- German: Ingenieur (de) m, Ingenieurin (de) f

- Greek: μηχανικός (el) m or f (michanikós), μηχανολόγος (el) m or f (michanológos)

- Ancient: μηχανικός m (mēkhanikós), μηχανοποιός m (mēkhanopoiós)

- Hawaiian: ʻenekinia

- Hebrew: מְהַנְדֵּס (he) m (m’handés)

- Hindi: इंजीनियर (hi) m (iñjīniyar), अभियंता m (abhiyantā), अभियन्ता m (abhiyantā)

- Hungarian: mérnök (hu)

- Icelandic: verkfræðingur m

- Indonesian: insinyur (id)

- Ingrian: inženera

- Irish: innealtóir m

- Italian: ingegnere (it) m, ingegnera f

- Japanese: エンジニア (ja) (enjinia), 技術者 (ja) (ぎじゅつしゃ, gijutsusha), 技師 (ja) (ぎし, gishi)

- Kazakh: инженер (kk) (injener)

- Khmer: វិស្វករ (km) (vɨhsvaʼkɑɑ)

- Korean: 기사(技師) (ko) (gisa), 기술자(技術者) (ko) (gisulja), 공학자(工學者) (gonghakja)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: ئەندازیار (ckb) (endazyar)

- Northern Kurdish: endazyar (ku)

- Kyrgyz: инженер (ky) (injener)

- Ladino: injeniero, moendiz

- Lao: ນາຍຊ່າງ (nāi sāng), ສະຖາປະນິກ (sa thā pa nik), ວິດສະວະກອນ (wit sa wa kǭn)

- Latin: māchinātor m

- Latvian: inženieris m

- Lithuanian: inžinierius m, inžiniẽrė f

- Luxembourgish: Ingenieur m, Ingenieurin f

- Macedonian: инженер m (inžener), инженерка f (inženerka)

- Malay: jurutera (ms)

- Maltese: inġinier m

- Manx: jeshaghteyr m

- Marathi: इंजिनियर m (iñjiniyar)

- Mongolian: инженер (mn) (inžener)

- Neapolitan: ‘ngigniére

- Norman: înginnieux m (Jersey)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: ingeniør (no) m

- Nynorsk: ingeniør m

- Occitan: engenhaire (oc) m

- Persian: انجنیر (fa) (enjenier), مهندس (fa) (mohandes)

- Polish: inżynier (pl) m

- Portuguese: engenheiro (pt) m, engenheira f

- Romanian: inginer (ro) m, ingineră (ro) f

- Russian: инжене́р (ru) m (inženér), инжене́рка (ru) f (inženérka), инжене́рша (ru) f (inženérša)

- Rusyn: інжінї́р m (inžinjír)

- Sanskrit: अभियन्तृ m (abhiyantṛ) (neologism)

- Scots: ingineer

- Scottish Gaelic: einnseanair m, innleadair m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: инжѐње̄р m

- Roman: inžènjēr (sh) m

- Sinhalese: මැවිසුරු (si) (mæwisuru)

- Sicilian: ncigneri (scn) m

- Slovak: inžinier m

- Slovene: inženir m

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: inženjer m, inženjerka f

- Upper Sorbian: inženjer m

- Spanish: ingeniero (es) m, ingeniera f

- Swedish: ingenjör (sv) c

- Tagalog: inhinyero

- Haitian Creole: enjenyè

- Tajik: муҳандис (tg) (muhandis)

- Tatar: инженер (injener), мөхәндис (möxändis)

- Telugu: యంత్రకారుడు (te) (yantrakāruḍu)

- Thai: วิศวกร (th) (wít-sà-wá-gɔɔn)

- Turkish: kıvcı, mühendis (tr)

- Turkmen: injener, inžener

- Ukrainian: інжене́р m (inženér), інжене́рка f (inženérka)

- Urdu: مہندس m (muhandis)

- Uzbek: injener (uz), muhandis (uz)

- Vietnamese: kĩ sư, kỹ sư (vi)

- Welsh: peiriannwr (cy) m, peiriannydd (cy) m

- Yiddish: אינזשעניר m (inzhenir)

- Yoruba: ẹlẹ́rọ, ẹn̄jiníà

person trained to operate an engine — see engineman

person who drives or operates a fire engine

person who drives or operates a locomotive — See also translations at engine driver

- Azerbaijani: maşinist

- Belarusian: машыні́ст m (mašyníst)

- Bulgarian: машини́ст (bg) m (mašiníst)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 司機/司机 (zh) (sījī)

- Dutch: machinist (nl) m, treinbestuurder (nl) m (Belgium)

- Finnish: veturinkuljettaja (fi)

- French: conducteur de train m, machiniste (fr) m or f

- Galician: maquinista (gl) m or f

- German: Maschinist (de) m, Maschinistin (de) f, Lokomotivführer (de) m, Lokomotivführerin (de) f

- Greek: μηχανικός (el) m or f (michanikós)

- Hungarian: mozdonyvezető (hu), masiniszta (hu)

- Italian: macchinista (it) m or f

- Japanese: 機関士 (きかんし, kikanshi)

- Korean: 기술자 (ko) (gisulja), 기관사 (ko) (gigwansa)

- Polish: maszynista (pl) m, maszynistka (pl) f

- Portuguese: maquinista (pt) m or f

- Romanian: mecanic (ro) m or f

- Russian: машини́ст (ru) m (mašiníst) (no feminine form exists)

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: машиновођа m, стројовођа m, влаковођа m, возовођа m

- Roman: mašinovođa (sh) m, strojovođa (sh) m, vlakovođa (sh) m, vozovođa (sh) m

- Sicilian: machinista m

- Spanish: maquinista (es) m or f

- Swedish: lokförare (sv) c

- Tagalog: makinista

- Tigrinya: መራሕ ባቡር (märaḥ babur)

- Turkish: makinist (tr)

- Ukrainian: машині́ст m (mašyníst)

- Uzbek: mashinist (uz)

- Vietnamese: người phụ trách máy

person who uses abilities or knowledge to manipulate events or people

Translations to be checked

Verb[edit]

engineer (third-person singular simple present engineers, present participle engineering, simple past and past participle engineered)

- (transitive)

- To employ one’s abilities and knowledge as an engineer to design, construct, and/or maintain (something, such as a machine or a structure), usually for industrial or public use.

- (specifically) To use genetic engineering to alter or construct (a DNA sequence), or to alter (an organism).

-

2018, Timothy R. Jennings, The Aging Brain, →ISBN, page 41:

-

In an interesting animal study, scientists engineered mice with a specific gene defect that caused memory and learning problems.

-

-

- To plan or achieve (a goal) by contrivance or guile; to finagle, to wangle.

- (intransitive)

- To formulate plots or schemes; to plot, to scheme.

- Synonym: machinate

- (rare) To work as an engineer.

-

1870, Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Works and Days”, in Society and Solitude. Twelve Chapters, Boston, Mass.: Fields, Osgood, & Co., →OCLC, page 144:

-

What of the grand tools with which we engineer, like kobolds and enchanters,—tunnelling Alps, canalling the American Isthmus, piercing the Arabian desert?

-

-

- To formulate plots or schemes; to plot, to scheme.

Derived terms[edit]

- engineerability

- engineerable

- engineered (adjective)

- engineering (adjective, noun)

- nonengineered

- outengineer

- overengineer

- re-engineer

- reengineer

- retro-engineer

- reverse-engineer

- unengineered

Translations[edit]

to employ one’s knowledge and skills as an engineer to design, construct, and/or maintain (something, such as a machine or a structure), usually for industrial or public use

to use genetic engineering to alter or construct (a DNA sequence), or to alter (an organism)

to work as engineer

- Armenian: նախագծել (hy) (naxagcel)

- Finnish: suunnitella (fi), toteuttaa (fi) (depending on the focus of the work)

- Greek: απεργάζομαι (el) (apergázomai), χαλκεύω (el) (chalkévo), εξυφαίνω (el) (exyfaíno), σκαρώνω (el) (skaróno) (informal)

- Norman: înginnyi

- Yiddish: אויסאינזשענירן (oysinzhenirn)

References[edit]

- ^ “engineer, n.”, in OED Online

, Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, December 2021; “engineer, n.”, in Lexico, Dictionary.com; Oxford University Press, 2019–2022.

- ^ “enǧinǒur, -er, n.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007.

- ^ “engineer, v.”, in OED Online

, Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, December 2019; “engineer, v.”, in Lexico, Dictionary.com; Oxford University Press, 2019–2022.

Further reading[edit]

Anagrams[edit]

- re-engine, reengine

Talk To Other Members

Talk To Other Members