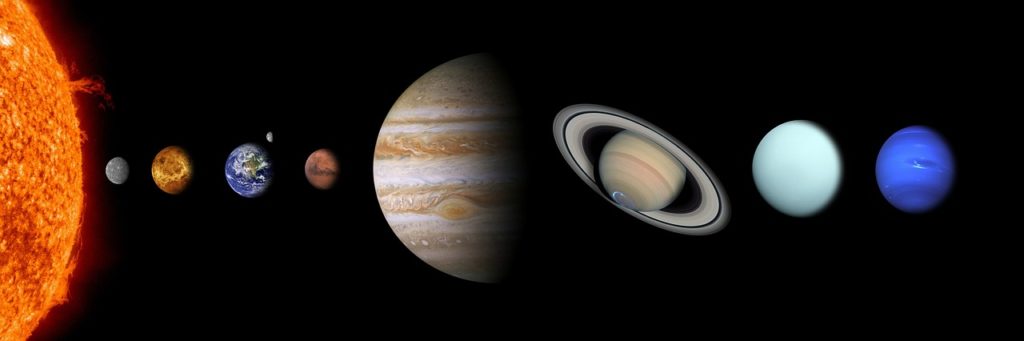

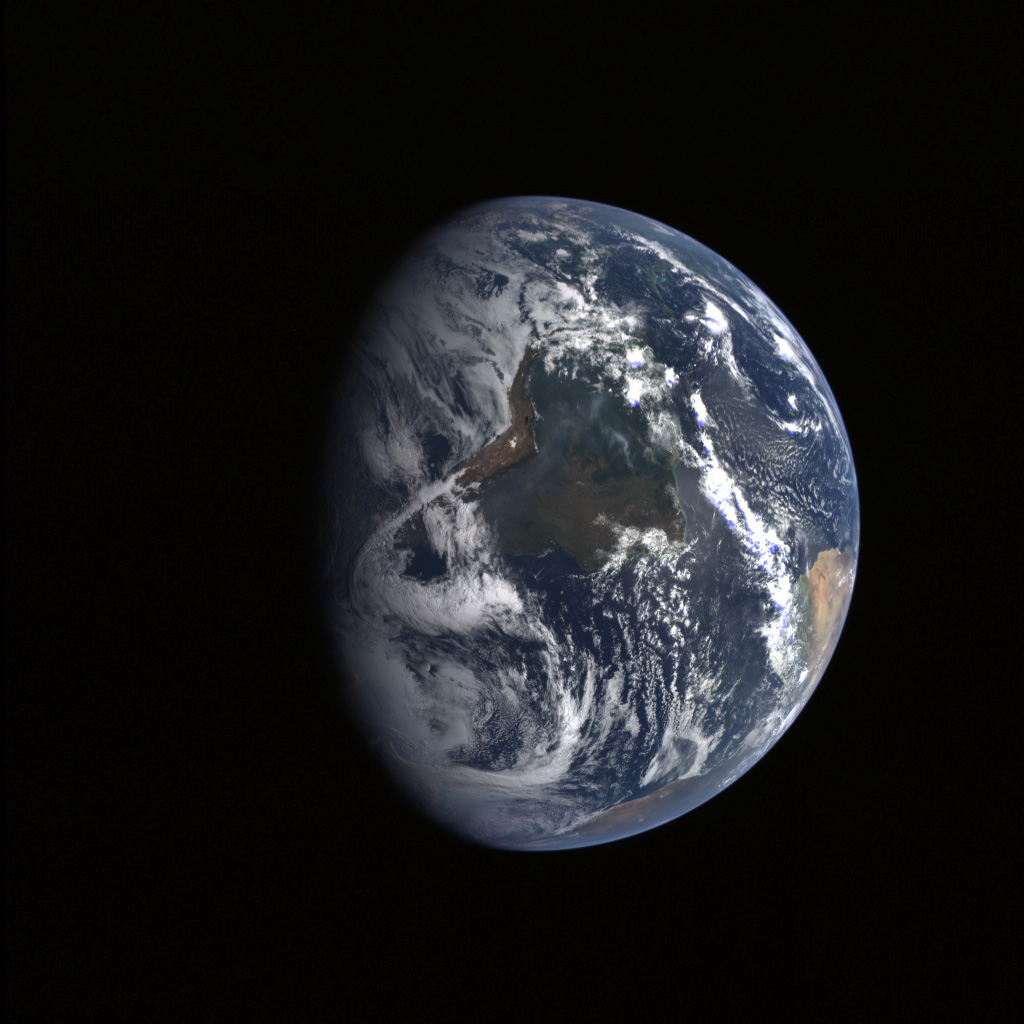

Earth as seen from space beyond low Earth orbit, with its facing side fully illuminated by sunlight. The image is a widely used photograph of Earth called The Blue Marble.[1][2] |

||||||||||||

| Designations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alternative names |

Prithvi, Gaia, Terra, Tellus, the world, the globe, Sol III | |||||||||||

| Adjectives | Earthly, terrestrial, terran, tellurian | |||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000[n 1] | ||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 152,097,597 kilometres (94,509,065 mi) | |||||||||||

| Perihelion | 147098450 km (91402740 mi)[n 2] | |||||||||||

|

Semi-major axis |

149598023 km (92955902 mi)[3] | |||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0167086[3] | |||||||||||

|

Orbital period (sidereal) |

365.256363004 d[4] (1.00001742096 aj) |

|||||||||||

|

Average orbital speed |

29.7827 km/s[5] (107218 km/h; 66622 mph) |

|||||||||||

|

Mean anomaly |

358.617° | |||||||||||

| Inclination |

|

|||||||||||

|

Longitude of ascending node |

−11.26064°[5] to J2000 ecliptic | |||||||||||

|

Time of perihelion |

2023-Jan-04[7] | |||||||||||

|

Argument of perihelion |

114.20783°[5] | |||||||||||

| Satellites |

|

|||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | ||||||||||||

|

Mean radius |

6371.0 km (3958.8 mi)[9] | |||||||||||

|

Equatorial radius |

6378.137 km (3963.191 mi)[10][11] | |||||||||||

|

Polar radius |

6356.752 km (3949.903 mi)[12] | |||||||||||

| Flattening | 1/298.257222101 (ETRS89)[13] | |||||||||||

| Circumference |

|

|||||||||||

|

Surface area |

Total: 510072000 km2 (196940000 sq mi)[15][n 5]

Land: 148940000 km2 (57510000 sq mi) – 29.2% Ocean: 361132000 km2 (139434000 sq mi) – 70.8% |

|||||||||||

| Volume | 1.08321×1012 km3 (2.59876×1011 cu mi)[5] | |||||||||||

| Mass | 5.972168×1024 kg (1.31668×1025 lb)[16] (3.0×10−6 M☉) |

|||||||||||

|

Mean density |

5.5134 g/cm3 (0.19918 lb/cu in)[5] | |||||||||||

|

Surface gravity |

9.80665 m/s2 (1 g; 32.1740 ft/s2)[17] | |||||||||||

|

Moment of inertia factor |

0.3307[18] | |||||||||||

|

Escape velocity |

11.186 km/s[5] (40270 km/h; 25020 mph) | |||||||||||

|

Synodic rotation period |

1.0 d |

|||||||||||

|

Sidereal rotation period |

0.99726968 d[19] |

|||||||||||

|

Equatorial rotation velocity |

0.4651 km/s[20] (1674.4 km/h; 1040.4 mph) |

|||||||||||

|

Axial tilt |

23.4392811°[4] | |||||||||||

| Albedo |

|

|||||||||||

| Temperature | 287.91 K (14.76 °C) (blackbody temperature)[21] | |||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Surface equivalent dose rate | 0.274 μSv/h[25] | |||||||||||

| Atmosphere | ||||||||||||

|

Surface pressure |

101.325 kPa (at MSL) | |||||||||||

| Composition by volume |

|

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only place known in the universe where life has originated and found habitability. While Earth may not contain the largest volumes of water in the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water, extending over 70.8% of the Earth with its ocean, making Earth an ocean world. Earth’s polar regions currently retain most of all other water with large sheets of ice covering ocean and land, dwarfing Earth’s groundwater, lakes, rivers and atmospheric water. Land, consisting of continents and islands, extends over 29.2% of the Earth and is widely covered by vegetation. Below Earth’s surface material lies Earth’s crust consisting of several slowly moving tectonic plates, which interact to produce mountain ranges, volcanoes, and earthquakes. Earth’s liquid outer core generates a magnetic field that shapes the magnetosphere of Earth, largely deflecting destructive solar winds and cosmic radiation.

Earth has an atmosphere, which sustains Earth’s surface conditions and protects it from most meteoroids and UV-light at entry. It has a composition of primarily nitrogen and oxygen. Water vapor is widely present in the atmosphere, forming clouds that cover most of the planet. The water vapor, like the liquid surface water, mainly persists by traping together with other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), energy from the Sun’s light, creating a crucial average surface temperature of currently 14.76 °C. Differences in the amount of captured energy between geographic regions (as with the equatorial region receiving more sunlight than the polar regions) drive atmospheric and ocean currents, producing a global climate system with different climate regions, and a range of weather phenomena such as precipitation, allowing components such as nitrogen to cycle.

Earth is rounded into an ellipsoid with a circumference of about 40,000 km. It is the densest planet in the Solar System. Of the four rocky planets, it is the largest and most massive. Earth is about eight light-minutes away from the Sun and orbits it, taking a year (about 365.25 days) to complete one revolution. The Earth rotates around its own axis in slightly less than a day (in about 23 hours and 56 minutes). The Earth’s axis of rotation is tilted with respect to the perpendicular to its orbital plane around the Sun, producing seasons. Earth is orbited by one permanent natural satellite, the Moon, which orbits Earth at 384,400 km (1.28 light seconds) and is roughly a quarter as wide as Earth. Through tidal locking, the Moon always faces the Earth with the same side, which causes tides, stabilizes Earth’s axis, and gradually slows its rotation.

Earth, like most other bodies in the Solar System, formed 4.5 billion years ago from gas in the early Solar System. During the first billion years of Earth’s history, the ocean formed and then life developed within it. Life spread globally and has been altering Earth’s atmosphere and surface, leading to the Great Oxidation Event two billion years ago. Humans emerged 300,000 years ago, and have reached a population of 8 billion today. Humans depend on Earth’s biosphere and natural resources for their survival, but have increasingly impacted the planet’s environment. Humanity’s current impact on Earth’s climate and biosphere is unsustainable, threatening the livelihood of humans and many other life, causing widespread extinctions.[27]

Etymology

The Modern English word Earth developed, via Middle English, from an Old English noun most often spelled eorðe.[28] It has cognates in every Germanic language, and their ancestral root has been reconstructed as *erþō. In its earliest attestation, the word eorðe was already being used to translate the many senses of Latin terra and Greek γῆ gē: the ground, its soil, dry land, the human world, the surface of the world (including the sea), and the globe itself. As with Roman Terra/Tellūs and Greek Gaia, Earth may have been a personified goddess in Germanic paganism: late Norse mythology included Jörð (‘Earth’), a giantess often given as the mother of Thor.[29]

Historically, earth has been written in lowercase. From early Middle English, its definite sense as «the globe» was expressed as the earth. By the era of Early Modern English, capitalization of nouns began to prevail, and the earth was also written the Earth, particularly when referenced along with other heavenly bodies. More recently, the name is sometimes simply given as Earth, by analogy with the names of the other planets, though earth and forms with the remain common.[28] House styles now vary: Oxford spelling recognizes the lowercase form as the most common, with the capitalized form an acceptable variant. Another convention capitalizes «Earth» when appearing as a name (for example, «Earth’s atmosphere») but writes it in lowercase when preceded by the (for example, «the atmosphere of the earth»). It almost always appears in lowercase in colloquial expressions such as «what on earth are you doing?»[30]

Occasionally, the name Terra is used in scientific writing and especially in science fiction to distinguish humanity’s inhabited planet from others,[31] while in poetry Tellus has been used to denote personification of the Earth.[32] Terra is also the name of the planet in some Romance languages (languages that evolved from Latin) like Italian and Portuguese, while in other Romance languages the word gave rise to names with slightly altered spellings (like the Spanish Tierra and the French Terre). The Latinate form Gæa or Gaea () of the Greek poetic name Gaia (Γαῖα; Ancient Greek: [ɡâi̯.a] or [ɡâj.ja]) is rare, though the alternative spelling Gaia has become common due to the Gaia hypothesis, in which case its pronunciation is rather than the more classical English .[33]

There are a number of adjectives for the planet Earth. From Earth itself comes earthly. From the Latin Terra comes terran ,[34] terrestrial ,[35] and (via French) terrene ,[36] and from the Latin Tellus comes tellurian [37] and telluric.[38]

Chronology

Formation

Artist’s impression of the early Solar System’s protoplanetary disk, out of which Earth and other Solar System bodies formed

The oldest material found in the Solar System is dated to 4.5682+0.0002

−0.0004 Ga (billion years) ago.[39] By 4.54±0.04 Ga the primordial Earth had formed.[40] The bodies in the Solar System formed and evolved with the Sun. In theory, a solar nebula partitions a volume out of a molecular cloud by gravitational collapse, which begins to spin and flatten into a circumstellar disk, and then the planets grow out of that disk with the Sun. A nebula contains gas, ice grains, and dust (including primordial nuclides). According to nebular theory, planetesimals formed by accretion, with the primordial Earth being estimated as likely taking anywhere from 70 to 100 million years to form.[41]

Estimates of the age of the Moon range from 4.5 Ga to significantly younger.[42] A leading hypothesis is that it was formed by accretion from material loosed from Earth after a Mars-sized object with about 10% of Earth’s mass, named Theia, collided with Earth.[43] It hit Earth with a glancing blow and some of its mass merged with Earth.[44][45] Between approximately 4.1 and 3.8 Ga, numerous asteroid impacts during the Late Heavy Bombardment caused significant changes to the greater surface environment of the Moon and, by inference, to that of Earth.[46]

After formation

Earth’s atmosphere and oceans were formed by volcanic activity and outgassing.[48] Water vapor from these sources condensed into the oceans, augmented by water and ice from asteroids, protoplanets, and comets.[49] Sufficient water to fill the oceans may have been on Earth since it formed.[50] In this model, atmospheric greenhouse gases kept the oceans from freezing when the newly forming Sun had only 70% of its current luminosity.[51] By 3.5 Ga, Earth’s magnetic field was established, which helped prevent the atmosphere from being stripped away by the solar wind.[52]

As the molten outer layer of Earth cooled it formed the first solid crust, which is thought to have been mafic in composition. The first continental crust, which was more felsic in composition, formed by the partial melting of this mafic crust. The presence of grains of the mineral zircon of Hadean age in Eoarchean sedimentary rocks suggests that at least some felsic crust existed as early as 4.4 Ga, only 140 Ma after Earth’s formation.[53] There are two main models of how this initial small volume of continental crust evolved to reach its current abundance:[54] (1) a relatively steady growth up to the present day,[55] which is supported by the radiometric dating of continental crust globally and (2) an initial rapid growth in the volume of continental crust during the Archean, forming the bulk of the continental crust that now exists,[56][57] which is supported by isotopic evidence from hafnium in zircons and neodymium in sedimentary rocks. The two models and the data that support them can be reconciled by large-scale recycling of the continental crust, particularly during the early stages of Earth’s history.[58]

New continental crust forms as a result of plate tectonics, a process ultimately driven by the continuous loss of heat from Earth’s interior. Over the period of hundreds of millions of years, tectonic forces have caused areas of continental crust to group together to form supercontinents that have subsequently broken apart. At approximately 750 Ma, one of the earliest known supercontinents, Rodinia, began to break apart. The continents later recombined to form Pannotia at 600–540 Ma, then finally Pangaea, which also began to break apart at 180 Ma.[59]

The most recent pattern of ice ages began about 40 Ma,[60] and then intensified during the Pleistocene about 3 Ma.[61] High- and middle-latitude regions have since undergone repeated cycles of glaciation and thaw, repeating about every 21,000, 41,000 and 100,000 years.[62] The Last Glacial Period, colloquially called the «last ice age», covered large parts of the continents, to the middle latitudes, in ice and ended about 11,700 years ago.[63]

Origin of life and evolution

Chemical reactions led to the first self-replicating molecules about four billion years ago. A half billion years later, the last common ancestor of all current life arose.[65] The evolution of photosynthesis allowed the Sun’s energy to be harvested directly by life forms. The resultant molecular oxygen (O2) accumulated in the atmosphere and due to interaction with ultraviolet solar radiation, formed a protective ozone layer (O3) in the upper atmosphere.[66] The incorporation of smaller cells within larger ones resulted in the development of complex cells called eukaryotes.[67] True multicellular organisms formed as cells within colonies became increasingly specialized. Aided by the absorption of harmful ultraviolet radiation by the ozone layer, life colonized Earth’s surface.[68] Among the earliest fossil evidence for life is microbial mat fossils found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone in Western Australia,[69] biogenic graphite found in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks in Western Greenland,[70] and remains of biotic material found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.[71][72] The earliest direct evidence of life on Earth is contained in 3.45 billion-year-old Australian rocks showing fossils of microorganisms.[73][74]

During the Neoproterozoic, 1000 to 539 Ma, much of Earth might have been covered in ice. This hypothesis has been termed «Snowball Earth», and it is of particular interest because it preceded the Cambrian explosion, when multicellular life forms significantly increased in complexity.[75][76] Following the Cambrian explosion, 535 Ma, there have been at least five major mass extinctions and many minor ones.[77] Apart from the proposed current Holocene extinction event, the most recent was 66 Ma, when an asteroid impact triggered the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and other large reptiles, but largely spared small animals such as insects, mammals, lizards and birds. Mammalian life has diversified over the past 66 Mys, and several million years ago an African ape species gained the ability to stand upright.[78][better source needed] This facilitated tool use and encouraged communication that provided the nutrition and stimulation needed for a larger brain, which led to the evolution of humans. The development of agriculture, and then civilization, led to humans having an influence on Earth and the nature and quantity of other life forms that continues to this day.[79]

Future

Conjectured illustration of the scorched Earth after the Sun has entered the red giant phase, about 5–7 billion years from now

Earth’s expected long-term future is tied to that of the Sun. Over the next 1.1 billion years, solar luminosity will increase by 10%, and over the next 3.5 billion years by 40%.[80] Earth’s increasing surface temperature will accelerate the inorganic carbon cycle, reducing CO2 concentration to levels lethally low for plants (10 ppm for C4 photosynthesis) in approximately 100–900 million years.[81][82] The lack of vegetation will result in the loss of oxygen in the atmosphere, making animal life impossible.[83] Due to the increased luminosity, Earth’s mean temperature may reach 100 °C (212 °F) in 1.5 billion years, and all ocean water will evaporate and be lost to space, which may trigger a runaway greenhouse effect, within an estimated 1.6 to 3 billion years.[84] Even if the Sun were stable, a fraction of the water in the modern oceans will descend to the mantle, due to reduced steam venting from mid-ocean ridges.[84][85]

The Sun will evolve to become a red giant in about 5 billion years. Models predict that the Sun will expand to roughly 1 AU (150 million km; 93 million mi), about 250 times its present radius.[80][86] Earth’s fate is less clear. As a red giant, the Sun will lose roughly 30% of its mass, so, without tidal effects, Earth will move to an orbit 1.7 AU (250 million km; 160 million mi) from the Sun when the star reaches its maximum radius, otherwise, with tidal effects, it may enter the Sun’s atmosphere and be vaporized.[80]

Geophysical characteristics

Size and shape

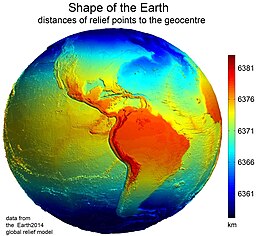

Topographic view of Earth relative to Earth’s center (instead of to mean sea level, as in common topographic maps)

Earth has a rounded shape, through hydrostatic equilibrium,[87] with an average diameter of 12,742 kilometers (7,918 mi), making it the fifth largest planetary sized and largest terrestrial object of the Solar System.

Due to Earth’s rotation it has the shape of an ellipsoid, bulging at its Equator, reaching 43 kilometers (27 mi) further out from its center of mass than at its poles.[88][89]

Earth’s shape furthermore has local topographic variations. Though the largest local variations, like the Mariana Trench (10,925 meters or 35,843 feet below local sea level),[90] only shortens Earth’s average radius by 0.17% and Mount Everest (8,848 meters or 29,029 feet above local sea level) lengthens it by only 0.14%.[n 6][92] Since Earth’s surface is farthest out from Earth’s center of mass at its equatorial bulge, the summit of the volcano Chimborazo in Ecuador (6,384.4 km or 3,967.1 mi) is its farthest point out.[93][94]

Parallel to the rigid land topography the Ocean exhibits a more dynamic topography.[95]

To measure the local variation of Earth’s topography, geodesy employs an idealized Earth producing a shape called a geoid. Such a geoid shape is gained if the ocean is idealized, covering Earth completely and without any perturbations such as tides and winds. The result is a smooth but gravitational irregular geoid surface, providing a mean sea level (MSL) as a reference level for topographic measurements.[96]

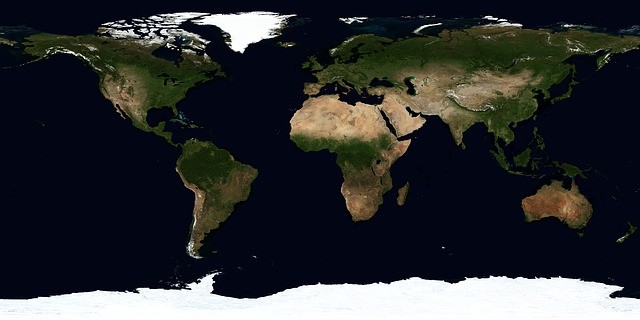

Surface

Earth’s surface is the top layer of Earth’s rigid or liquid structure, at the interface with its atmosphere. Earth as an idealized spheroid has a surface area of about 510 million km2 (197 million sq mi).[15] Earth can be divided into two hemispheres. Generally, Earth is divided by latitude into the polar Northern and Southern hemispheres, or by longitude into the continental Eastern and Western hemispheres. Regarding the surface distribution of land and water, Earth can be divided into an oceans-focused water hemisphere and a landmasses-focused land hemisphere.

Most of Earth’s surface is made of water, in liquid form or in smaller amounts as ice. 70.8% or 361.13 million km2 (139.43 million sq mi) of Earth’s surface consists of the interconnected ocean,[97] making it Earth’s global ocean or world ocean.[98][99] This makes Earth, along with its vibrant hydrosphere, a water world[100][101] or ocean world,[102][103] particularly in Earth’s early history when the ocean is thought to have possibly covered Earth completely.[104] The world ocean is commonly divided into the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Southern Ocean, and Arctic Ocean, from largest to smallest. The ocean fills the oceanic basins. The ocean floor comprises abyssal plains, continental shelves, seamounts, submarine volcanoes,[88] oceanic trenches, submarine canyons, oceanic plateaus, and a globe-spanning mid-ocean ridge system.

At Earth’s polar regions, the ocean surface is covered by a seasonally variable amount of sea ice that often connects with polar land, permafrost and ice sheets, forming polar ice caps.

Earth’s land is 29.2%, or 148.94 million km2 (57.51 million sq mi) of Earth’s surface area. Earth’s land consists of many islands around the globe, but mainly of four continental landmasses, which are, from largest to smallest: Africa-Eurasia, America (landmass), Antarctica, and Australia (landmass).[105][106][107] These landmasses are further broken down and grouped into the continents. The terrain varies greatly and consists of mountains, deserts, plains, plateaus, and other landforms. The elevation of the land surface varies from the low point of −418 m (−1,371 ft) at the Dead Sea, to a maximum altitude of 8,848 m (29,029 ft) at the top of Mount Everest. The mean height of land above sea level is about 797 m (2,615 ft).[108]

Land can be covered by surface water, snow, ice, artificial structures or vegetation. Most of Earth’s land hosts vegetation,[109] but ice sheets (10 %,[110] not including the equally large land under permafrost)[111] or cold as well as hot deserts (33 %)[112] occupy also considerable amounts of it.

The pedosphere is the outermost layer of Earth’s continental surface and is composed of soil and subject to soil formation processes. Soil is crucial for land to be arable. Earth’s total arable land is 10.7% of the land surface, with 1.3% being permanent cropland.[113][114] Earth has an estimated 16.7 million km2 (6.4 million sq mi) of cropland and 33.5 million km2 (12.9 million sq mi) of pastureland.[115]

The pedosphere and the ocean, with its ocean floor, rest on Earth’s crust, which together with parts of the upper mantle form Earth’s lithosphere.

Earth’s crust is divided into oceanic and continental crusts, while the latter consists of lower density material such as the igneous rocks granite and andesite. Basalt, a denser volcanic rock primarily constitutes the lithosphere of the ocean floors.[116]

Earth’s surface topography consists mostly of the topography of the ocean surface and to a lesser extend of the terrain of Earth’s crust above sea level. The larger part of Earth’s crust that lies below the ocean hosts the ocean floor at an average bathymetric depth of 4 km and has a terrain as varied as the terrain above sea level. Earth’s terrain and landscape is being shaped by internal seismic and volcanic processes, asteroid impacts, wind and temperature weathering, tidal forces, life and the large presence of water and the processes that place and move Earth’s water as surface water and ocean water.

Erosion and tectonics, volcanic eruptions, flooding, weathering, glaciation, the growth and decomposition of biomass into soil or other remains such as coral reefs, and meteorite impacts are among the processes that constantly reshape Earth’s crust over geological time.[117][118]

Sedimentary rock is formed from the accumulation of sediment that becomes buried and compacted together. Nearly 75% of the continental surfaces are covered by sedimentary rocks, although they form about 5% of the crust.[119] The third form of rock material found on Earth is metamorphic rock, which is created from the transformation of pre-existing rock types through high pressures, high temperatures, or both. The most abundant silicate minerals on Earth’s surface include quartz, feldspars, amphibole, mica, pyroxene and olivine.[120] Common carbonate minerals include calcite (found in limestone) and dolomite.[121]

Tectonic plates

Earth’s mechanically rigid outer layer of Earth’s crust and upper mantle, the lithosphere, is divided into tectonic plates. These plates are rigid segments that move relative to each other at one of three boundaries types: at convergent boundaries, two plates come together; at divergent boundaries, two plates are pulled apart; and at transform boundaries, two plates slide past one another laterally. Along these plate boundaries, earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation can occur.[123] The tectonic plates ride on top of the asthenosphere, the solid but less-viscous part of the upper mantle that can flow and move along with the plates.[124]

As the tectonic plates migrate, oceanic crust is subducted under the leading edges of the plates at convergent boundaries. At the same time, the upwelling of mantle material at divergent boundaries creates mid-ocean ridges. The combination of these processes recycles the oceanic crust back into the mantle. Due to this recycling, most of the ocean floor is less than 100 Ma old. The oldest oceanic crust is located in the Western Pacific and is estimated to be 200 Ma old.[125][126] By comparison, the oldest dated continental crust is 4,030 Ma,[127] although zircons have been found preserved as clasts within Eoarchean sedimentary rocks that give ages up to 4,400 Ma, indicating that at least some continental crust existed at that time.[53]

The seven major plates are the Pacific, North American, Eurasian, African, Antarctic, Indo-Australian, and South American. Other notable plates include the Arabian Plate, the Caribbean Plate, the Nazca Plate off the west coast of South America and the Scotia Plate in the southern Atlantic Ocean. The Australian Plate fused with the Indian Plate between 50 and 55 Ma. The fastest-moving plates are the oceanic plates, with the Cocos Plate advancing at a rate of 75 mm/a (3.0 in/year)[128] and the Pacific Plate moving 52–69 mm/a (2.0–2.7 in/year). At the other extreme, the slowest-moving plate is the South American Plate, progressing at a typical rate of 10.6 mm/a (0.42 in/year).[129]

Internal structure

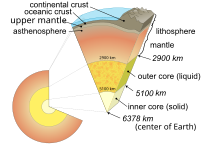

|

Illustration of Earth’s cutaway, not to scale |

||

| Depth[131] (km) |

Component layer name |

Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|

| 0–60 | Lithosphere[n 8] | — |

| 0–35 | Crust[n 9] | 2.2–2.9 |

| 35–660 | Upper mantle | 3.4–4.4 |

| 660–2890 | Lower mantle | 3.4–5.6 |

| 100–700 | Asthenosphere | — |

| 2890–5100 | Outer core | 9.9–12.2 |

| 5100–6378 | Inner core | 12.8–13.1 |

Earth’s interior, like that of the other terrestrial planets, is divided into layers by their chemical or physical (rheological) properties. The outer layer is a chemically distinct silicate solid crust, which is underlain by a highly viscous solid mantle. The crust is separated from the mantle by the Mohorovičić discontinuity.[132] The thickness of the crust varies from about 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) under the oceans to 30–50 km (19–31 mi) for the continents. The crust and the cold, rigid, top of the upper mantle are collectively known as the lithosphere, which is divided into independently moving tectonic plates.[133]

Beneath the lithosphere is the asthenosphere, a relatively low-viscosity layer on which the lithosphere rides. Important changes in crystal structure within the mantle occur at 410 and 660 km (250 and 410 mi) below the surface, spanning a transition zone that separates the upper and lower mantle. Beneath the mantle, an extremely low viscosity liquid outer core lies above a solid inner core.[134] Earth’s inner core may be rotating at a slightly higher angular velocity than the remainder of the planet, advancing by 0.1–0.5° per year, although both somewhat higher and much lower rates have also been proposed.[135] The radius of the inner core is about one-fifth of that of Earth.

Density increases with depth, as described in the table on the right.

Among the Solar System’s planetary-sized objects Earth is the object with the highest density.

Chemical composition

Earth’s mass is approximately 5.97×1024 kg (5,970 Yg). It is composed mostly of iron (32.1% by mass), oxygen (30.1%), silicon (15.1%), magnesium (13.9%), sulfur (2.9%), nickel (1.8%), calcium (1.5%), and aluminum (1.4%), with the remaining 1.2% consisting of trace amounts of other elements. Due to gravitational separation, the core is primarily composed of the denser elements: iron (88.8%), with smaller amounts of nickel (5.8%), sulfur (4.5%), and less than 1% trace elements.[136] The most common rock constituents of the crust are oxides. Over 99% of the crust is composed of various oxides of eleven elements, principally oxides containing silicon (the silicate minerals), aluminum, iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, or sodium.[137][136]

Internal heat

The major heat-producing isotopes within Earth are potassium-40, uranium-238, and thorium-232.[138] At the center, the temperature may be up to 6,000 °C (10,830 °F),[139] and the pressure could reach 360 GPa (52 million psi).[140] Because much of the heat is provided by radioactive decay, scientists postulate that early in Earth’s history, before isotopes with short half-lives were depleted, Earth’s heat production was much higher. At approximately 3 Gyr, twice the present-day heat would have been produced, increasing the rates of mantle convection and plate tectonics, and allowing the production of uncommon igneous rocks such as komatiites that are rarely formed today.[141][142]

The mean heat loss from Earth is 87 mW m−2, for a global heat loss of 4.42×1013 W.[143] A portion of the core’s thermal energy is transported toward the crust by mantle plumes, a form of convection consisting of upwellings of higher-temperature rock. These plumes can produce hotspots and flood basalts.[144] More of the heat in Earth is lost through plate tectonics, by mantle upwelling associated with mid-ocean ridges. The final major mode of heat loss is through conduction through the lithosphere, the majority of which occurs under the oceans because the crust there is much thinner than that of the continents.[145]

Gravitational field

The gravity of Earth is the acceleration that is imparted to objects due to the distribution of mass within Earth. Near Earth’s surface, gravitational acceleration is approximately 9.8 m/s2 (32 ft/s2). Local differences in topography, geology, and deeper tectonic structure cause local and broad regional differences in Earth’s gravitational field, known as gravity anomalies.[146]

Magnetic field

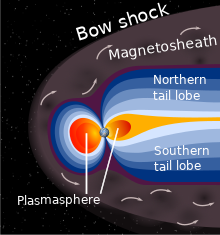

Schematic of Earth’s magnetosphere, with the solar wind flows from left to right

The main part of Earth’s magnetic field is generated in the core, the site of a dynamo process that converts the kinetic energy of thermally and compositionally driven convection into electrical and magnetic field energy. The field extends outwards from the core, through the mantle, and up to Earth’s surface, where it is, approximately, a dipole. The poles of the dipole are located close to Earth’s geographic poles. At the equator of the magnetic field, the magnetic-field strength at the surface is 3.05×10−5 T, with a magnetic dipole moment of 7.79×1022 Am2 at epoch 2000, decreasing nearly 6% per century (although it still remains stronger than its long time average).[147] The convection movements in the core are chaotic; the magnetic poles drift and periodically change alignment. This causes secular variation of the main field and field reversals at irregular intervals averaging a few times every million years. The most recent reversal occurred approximately 700,000 years ago.[148][149]

The extent of Earth’s magnetic field in space defines the magnetosphere. Ions and electrons of the solar wind are deflected by the magnetosphere; solar wind pressure compresses the dayside of the magnetosphere, to about 10 Earth radii, and extends the nightside magnetosphere into a long tail.[150] Because the velocity of the solar wind is greater than the speed at which waves propagate through the solar wind, a supersonic bow shock precedes the dayside magnetosphere within the solar wind.[151] Charged particles are contained within the magnetosphere; the plasmasphere is defined by low-energy particles that essentially follow magnetic field lines as Earth rotates.[152][153] The ring current is defined by medium-energy particles that drift relative to the geomagnetic field, but with paths that are still dominated by the magnetic field,[154] and the Van Allen radiation belts are formed by high-energy particles whose motion is essentially random, but contained in the magnetosphere.[155][156]

During magnetic storms and substorms, charged particles can be deflected from the outer magnetosphere and especially the magnetotail, directed along field lines into Earth’s ionosphere, where atmospheric atoms can be excited and ionized, causing the aurora.[157]

Orbit and rotation

Rotation

Earth’s rotation period relative to the Sun—its mean solar day—is 86,400 seconds of mean solar time (86,400.0025 SI seconds).[158] Because Earth’s solar day is now slightly longer than it was during the 19th century due to tidal deceleration, each day varies between 0 and 2 ms longer than the mean solar day.[159][160]

Earth’s rotation period relative to the fixed stars, called its stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), is 86,164.0989 seconds of mean solar time (UT1), or 23h 56m 4.0989s.[4][n 10] Earth’s rotation period relative to the precessing or moving mean March equinox (when the Sun is at 90° on the equator), is 86,164.0905 seconds of mean solar time (UT1) (23h 56m 4.0905s).[4] Thus the sidereal day is shorter than the stellar day by about 8.4 ms.[161]

Apart from meteors within the atmosphere and low-orbiting satellites, the main apparent motion of celestial bodies in Earth’s sky is to the west at a rate of 15°/h = 15’/min. For bodies near the celestial equator, this is equivalent to an apparent diameter of the Sun or the Moon every two minutes; from Earth’s surface, the apparent sizes of the Sun and the Moon are approximately the same.[162][163]

Orbit

Exaggerated illustration of Earth’s elliptical orbit around the Sun, marking that the orbital extreme points (apoapsis and periapsis) are not the same as the four seasonal extreme points (equinox and solstice)

Earth orbits the Sun, making Earth the third-closest planet to the Sun and part of the inner Solar System. Earth’s average orbital distance is about 150 million km (93 million mi), which is the basis for the Astronomical Unit and is equal to roughly 8.3 light minutes or 380 times Earth’s distance to the Moon.

Earth orbits the Sun every 365.2564 mean solar days, or one sidereal year. With an apparent movement of the Sun in Earth’s sky at a rate of about 1°/day eastward, which is one apparent Sun or Moon diameter every 12 hours. Due to this motion, on average it takes 24 hours—a solar day—for Earth to complete a full rotation about its axis so that the Sun returns to the meridian.

The orbital speed of Earth averages about 29.78 km/s (107,200 km/h; 66,600 mph), which is fast enough to travel a distance equal to Earth’s diameter, about 12,742 km (7,918 mi), in seven minutes, and the distance to the Moon, 384,000 km (239,000 mi), in about 3.5 hours.[5]

The Moon and Earth orbit a common barycenter every 27.32 days relative to the background stars. When combined with the Earth-Moon system’s common orbit around the Sun, the period of the synodic month, from new moon to new moon, is 29.53 days. Viewed from the celestial north pole, the motion of Earth, the Moon, and their axial rotations are all counterclockwise. Viewed from a vantage point above the Sun and Earth’s north poles, Earth orbits in a counterclockwise direction about the Sun. The orbital and axial planes are not precisely aligned: Earth’s axis is tilted some 23.44 degrees from the perpendicular to the Earth-Sun plane (the ecliptic), and the Earth-Moon plane is tilted up to ±5.1 degrees against the Earth-Sun plane. Without this tilt, there would be an eclipse every two weeks, alternating between lunar eclipses and solar eclipses.[5][164]

The Hill sphere, or the sphere of gravitational influence, of Earth is about 1.5 million km (930,000 mi) in radius.[165][n 11] This is the maximum distance at which Earth’s gravitational influence is stronger than the more distant Sun and planets. Objects must orbit Earth within this radius, or they can become unbound by the gravitational perturbation of the Sun.[165] Earth, along with the Solar System, is situated in the Milky Way and orbits about 28,000 light-years from its center. It is about 20 light-years above the galactic plane in the Orion Arm.[166]

Axial tilt and seasons

Earth’s axial tilt causing different angles of seasonal illumination at different orbital positions around the Sun

The axial tilt of Earth is approximately 23.439281°[4] with the axis of its orbit plane, always pointing towards the Celestial Poles. Due to Earth’s axial tilt, the amount of sunlight reaching any given point on the surface varies over the course of the year. This causes the seasonal change in climate, with summer in the Northern Hemisphere occurring when the Tropic of Cancer is facing the Sun, and in the Southern Hemisphere when the Tropic of Capricorn faces the Sun. In each instance, winter occurs simultaneously in the opposite hemisphere. During the summer, the day lasts longer, and the Sun climbs higher in the sky. In winter, the climate becomes cooler and the days shorter.[167] Above the Arctic Circle and below the Antarctic Circle there is no daylight at all for part of the year, causing a polar night, and this night extends for several months at the poles themselves. These same latitudes also experience a midnight sun, where the sun remains visible all day.[168][169]

By astronomical convention, the four seasons can be determined by the solstices—the points in the orbit of maximum axial tilt toward or away from the Sun—and the equinoxes, when Earth’s rotational axis is aligned with its orbital axis. In the Northern Hemisphere, winter solstice currently occurs around 21 December; summer solstice is near 21 June, spring equinox is around 20 March and autumnal equinox is about 22 or 23 September. In the Southern Hemisphere, the situation is reversed, with the summer and winter solstices exchanged and the spring and autumnal equinox dates swapped.[170]

The angle of Earth’s axial tilt is relatively stable over long periods of time. Its axial tilt does undergo nutation; a slight, irregular motion with a main period of 18.6 years.[171] The orientation (rather than the angle) of Earth’s axis also changes over time, precessing around in a complete circle over each 25,800-year cycle; this precession is the reason for the difference between a sidereal year and a tropical year. Both of these motions are caused by the varying attraction of the Sun and the Moon on Earth’s equatorial bulge. The poles also migrate a few meters across Earth’s surface. This polar motion has multiple, cyclical components, which collectively are termed quasiperiodic motion. In addition to an annual component to this motion, there is a 14-month cycle called the Chandler wobble. Earth’s rotational velocity also varies in a phenomenon known as length-of-day variation.[172]

In modern times, Earth’s perihelion occurs around 3 January, and its aphelion around 4 July. These dates change over time due to precession and other orbital factors, which follow cyclical patterns known as Milankovitch cycles. The changing Earth-Sun distance causes an increase of about 6.8% in solar energy reaching Earth at perihelion relative to aphelion.[173][n 12] Because the Southern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun at about the same time that Earth reaches the closest approach to the Sun, the Southern Hemisphere receives slightly more energy from the Sun than does the northern over the course of a year. This effect is much less significant than the total energy change due to the axial tilt, and most of the excess energy is absorbed by the higher proportion of water in the Southern Hemisphere.[174]

Earth–Moon system

Moon

Earth–Moon system seen from Mars

The Moon is a relatively large, terrestrial, planet-like natural satellite, with a diameter about one-quarter of the Earth’s. It is the largest moon in the Solar System relative to the size of its planet, although Charon is larger relative to the dwarf planet Pluto.[175][176] The natural satellites of other planets are also referred to as «moons», after Earth’s.[177] The most widely accepted theory of the Moon’s origin, the giant-impact hypothesis, states that it formed from the collision of a Mars-size protoplanet called Theia with the early Earth. This hypothesis explains (among other things) the Moon’s relative lack of iron and volatile elements and the fact that its composition is nearly identical to that of Earth’s crust.[44]

The gravitational attraction between Earth and the Moon causes tides on Earth.[178] The same effect on the Moon has led to its tidal locking: its rotation period is the same as the time it takes to orbit Earth. As a result, it always presents the same face to the planet.[179] As the Moon orbits Earth, different parts of its face are illuminated by the Sun, leading to the lunar phases.[180] Due to their tidal interaction, the Moon recedes from Earth at the rate of approximately 38 mm/a (1.5 in/year). Over millions of years, these tiny modifications—and the lengthening of Earth’s day by about 23 µs/yr—add up to significant changes.[181] During the Ediacaran period, for example, (approximately 620 Ma) there were 400±7 days in a year, with each day lasting 21.9±0.4 hours.[182]

The Moon may have dramatically affected the development of life by moderating the planet’s climate. Paleontological evidence and computer simulations show that Earth’s axial tilt is stabilized by tidal interactions with the Moon.[183] Some theorists think that without this stabilization against the torques applied by the Sun and planets to Earth’s equatorial bulge, the rotational axis might be chaotically unstable, exhibiting large changes over millions of years, as is the case for Mars, though this is disputed.[184][185]

Viewed from Earth, the Moon is just far enough away to have almost the same apparent-sized disk as the Sun. The angular size (or solid angle) of these two bodies match because, although the Sun’s diameter is about 400 times as large as the Moon’s, it is also 400 times more distant.[163] This allows total and annular solar eclipses to occur on Earth.[186]

Asteroids and artificial satellites

Earth’s co-orbital asteroids population consists of quasi-satellites, objects with a horseshoe orbit and trojans. There are at least five quasi-satellites, including 469219 Kamoʻoalewa.[187][188] A trojan asteroid companion, 2010 TK7, is librating around the leading Lagrange triangular point, L4, in Earth’s orbit around the Sun.[189] The tiny near-Earth asteroid 2006 RH120 makes close approaches to the Earth–Moon system roughly every twenty years. During these approaches, it can orbit Earth for brief periods of time.[190]

As of September 2021, there are 4,550 operational, human-made satellites orbiting Earth.[8] There are also inoperative satellites, including Vanguard 1, the oldest satellite currently in orbit, and over 16,000 pieces of tracked space debris.[n 3] Earth’s largest artificial satellite is the International Space Station.[191]

Hydrosphere

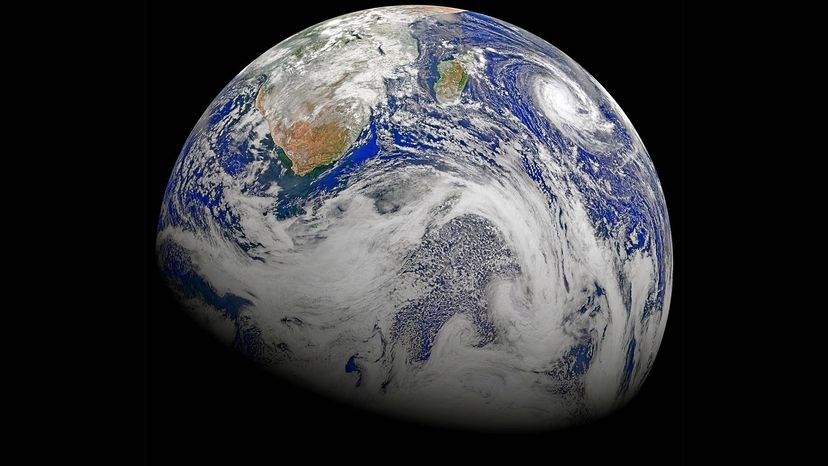

A view of Earth with its global ocean and cloud cover, which dominate Earth’s surface and hydrosphere. At Earth’s polar regions Earth’s hydrosphere forms larger areas of ice cover.

Earth’s hydrosphere is the sum of Earth’s water and its distribution.

Most of Earth’s hydrosphere consists of Earth’s global ocean. Nevertheless, Earth’s hydrosphere also consists of water in the atmosphere and on land, including clouds, inland seas, lakes, rivers, and underground waters down to a depth of 2,000 m (6,600 ft). The mass of the oceans is approximately 1.35×1018 metric tons or about 1/4400 of Earth’s total mass. The oceans cover an area of 361.8 million km2 (139.7 million sq mi) with a mean depth of 3,682 m (12,080 ft), resulting in an estimated volume of 1.332 billion km3 (320 million cu mi).[192] If all of Earth’s crustal surface were at the same elevation as a smooth sphere, the depth of the resulting world ocean would be 2.7 to 2.8 km (1.68 to 1.74 mi).[193] About 97.5% of the water is saline; the remaining 2.5% is fresh water.[194][195] Most fresh water, about 68.7%, is present as ice in ice caps and glaciers.[196] The remaining 30% is ground water, 1% surface water (covering only 2.8% of Earth’s land)[197] and other small forms of fresh water deposits such as permafrost, water vapor in the atmosphere, biological binding, etc. .[198][199]

In Earth’s coldest regions, snow survives over the summer and changes into ice. This accumulated snow and ice eventually forms into glaciers, bodies of ice that flow under the influence of their own gravity. Alpine glaciers form in mountainous areas, whereas vast ice sheets form over land in polar regions. The flow of glaciers erodes the surface changing it dramatically, with the formation of U-shaped valleys and other landforms.[200] Sea ice in the Arctic covers an area about as big as the United States, although it is quickly retreating as a consequence of climate change.[201]

The average salinity of Earth’s oceans is about 35 grams of salt per kilogram of seawater (3.5% salt).[202] Most of this salt was released from volcanic activity or extracted from cool igneous rocks.[203] The oceans are also a reservoir of dissolved atmospheric gases, which are essential for the survival of many aquatic life forms.[204] Sea water has an important influence on the world’s climate, with the oceans acting as a large heat reservoir.[205] Shifts in the oceanic temperature distribution can cause significant weather shifts, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.[206]

The abundance of water, particularly liquid water, on Earth’s surface is a unique feature that distinguishes it from other planets in the Solar System. Solar System planets with considerable atmospheres do partly host atmospheric water vapor, but they lack surface conditions for stable surface water.[207] Despite some moons showing signs of large reservoirs of extraterrestrial liquid water, with possibly even more volume than Earth’s ocean, all of them are large bodies of water under a kilometers thick frozen surface layer.[208]

Atmosphere

The atmospheric pressure at Earth’s sea level averages 101.325 kPa (14.696 psi),[209] with a scale height of about 8.5 km (5.3 mi).[5] A dry atmosphere is composed of 78.084% nitrogen, 20.946% oxygen, 0.934% argon, and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gaseous molecules.[209] Water vapor content varies between 0.01% and 4%[209] but averages about 1%.[5] Clouds cover around two thirds of Earth’s surface, more so over oceans than land.[210] The height of the troposphere varies with latitude, ranging between 8 km (5 mi) at the poles to 17 km (11 mi) at the equator, with some variation resulting from weather and seasonal factors.[211]

Earth’s biosphere has significantly altered its atmosphere. Oxygenic photosynthesis evolved 2.7 Gya, forming the primarily nitrogen–oxygen atmosphere of today.[66] This change enabled the proliferation of aerobic organisms and, indirectly, the formation of the ozone layer due to the subsequent conversion of atmospheric O2 into O3. The ozone layer blocks ultraviolet solar radiation, permitting life on land.[212] Other atmospheric functions important to life include transporting water vapor, providing useful gases, causing small meteors to burn up before they strike the surface, and moderating temperature.[213] This last phenomenon is the greenhouse effect: trace molecules within the atmosphere serve to capture thermal energy emitted from the surface, thereby raising the average temperature. Water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone are the primary greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Without this heat-retention effect, the average surface temperature would be −18 °C (0 °F), in contrast to the current +15 °C (59 °F),[214] and life on Earth probably would not exist in its current form.[215]

Weather and climate

Earth’s atmosphere has no definite boundary, gradually becoming thinner and fading into outer space.[216] Three-quarters of the atmosphere’s mass is contained within the first 11 km (6.8 mi) of the surface; this lowest layer is called the troposphere.[217] Energy from the Sun heats this layer, and the surface below, causing expansion of the air. This lower-density air then rises and is replaced by cooler, higher-density air. The result is atmospheric circulation that drives the weather and climate through redistribution of thermal energy.[218]

The primary atmospheric circulation bands consist of the trade winds in the equatorial region below 30° latitude and the westerlies in the mid-latitudes between 30° and 60°.[219] Ocean heat content and currents are also important factors in determining climate, particularly the thermohaline circulation that distributes thermal energy from the equatorial oceans to the polar regions.[220]

Earth receives 1361 W/m2 of solar irradiance.[221][222] The amount of solar energy that reaches the Earth’s surface decreases with increasing latitude. At higher latitudes, the sunlight reaches the surface at lower angles, and it must pass through thicker columns of the atmosphere. As a result, the mean annual air temperature at sea level decreases by about 0.4 °C (0.7 °F) per degree of latitude from the equator.[223] Earth’s surface can be subdivided into specific latitudinal belts of approximately homogeneous climate. Ranging from the equator to the polar regions, these are the tropical (or equatorial), subtropical, temperate and polar climates.[224]

Further factors that affect a location’s climates are its proximity to oceans, the oceanic and atmospheric circulation, and topology.[225] Places close to oceans typically have colder summers and warmer winters, due to the fact that oceans can store large amounts of heat. The wind transports the cold or the heat of the ocean to the land.[226] Atmospheric circulation also plays an important role: San Francisco and Washington DC are both coastal cities at about the same latitude. San Francisco’s climate is significantly more moderate as the prevailing wind direction is from sea to land.[227] Finally, temperatures decrease with height causing mountainous areas to be colder than low-lying areas.[228]

Water vapor generated through surface evaporation is transported by circulatory patterns in the atmosphere. When atmospheric conditions permit an uplift of warm, humid air, this water condenses and falls to the surface as precipitation.[218] Most of the water is then transported to lower elevations by river systems and usually returned to the oceans or deposited into lakes. This water cycle is a vital mechanism for supporting life on land and is a primary factor in the erosion of surface features over geological periods. Precipitation patterns vary widely, ranging from several meters of water per year to less than a millimeter. Atmospheric circulation, topographic features, and temperature differences determine the average precipitation that falls in each region.[229]

The commonly used Köppen climate classification system has five broad groups (humid tropics, arid, humid middle latitudes, continental and cold polar), which are further divided into more specific subtypes.[219] The Köppen system rates regions based on observed temperature and precipitation.[230] Surface air temperature can rise to around 55 °C (131 °F) in hot deserts, such as Death Valley, and can fall as low as −89 °C (−128 °F) in Antarctica.[231][232]

Upper atmosphere

Earth’s atmosphere as it appears from space, as bands of different colours at the horizon. From the bottom, afterglow illuminates the troposphere in orange with silhouettes of clouds, and the stratosphere in white and blue. Next the mesosphere (pink area) extends to just below the edge of space at one hundred kilometers and the pink line of airglow of the lower thermosphere (invisible), which hosts green and red aurorae over several hundred kilometers.

The upper atmosphere, the atmosphere above the troposphere,[233] is usually divided into the stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere.[213] Each layer has a different lapse rate, defining the rate of change in temperature with height. Beyond these, the exosphere thins out into the magnetosphere, where the geomagnetic fields interact with the solar wind.[234] Within the stratosphere is the ozone layer, a component that partially shields the surface from ultraviolet light and thus is important for life on Earth. The Kármán line, defined as 100 km (62 mi) above Earth’s surface, is a working definition for the boundary between the atmosphere and outer space.[235]

Thermal energy causes some of the molecules at the outer edge of the atmosphere to increase their velocity to the point where they can escape from Earth’s gravity. This causes a slow but steady loss of the atmosphere into space. Because unfixed hydrogen has a low molecular mass, it can achieve escape velocity more readily, and it leaks into outer space at a greater rate than other gases.[236] The leakage of hydrogen into space contributes to the shifting of Earth’s atmosphere and surface from an initially reducing state to its current oxidizing one. Photosynthesis provided a source of free oxygen, but the loss of reducing agents such as hydrogen is thought to have been a necessary precondition for the widespread accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere.[237] Hence the ability of hydrogen to escape from the atmosphere may have influenced the nature of life that developed on Earth.[238] In the current, oxygen-rich atmosphere most hydrogen is converted into water before it has an opportunity to escape. Instead, most of the hydrogen loss comes from the destruction of methane in the upper atmosphere.[239]

Life on Earth

An animation of the changing density of productive vegetation on land (low in brown; heavy in dark green) and phytoplankton at the ocean surface (low in purple; high in yellow)

Earth is the only known place that was and has been habitable for life. Earth’s life developed in Earth’s early bodies of water some hundred million years after Earth formed.

Earth’s life has been shaping and inhabiting many particular ecosystems on Earth and has eventually expanded globally forming an overarching biosphere.[240] Therefore, life has impacted Earth, significantly altering Earth’s atmosphere and surface over long periods of time, causing changes like the Great oxidation event.

Earth’s life has over time greatly diversified, allowing the biosphere to have different biomes, which are inhabited by comparatively similar plants and animals.[241] The different biomes developed at distinct elevations or water depths, planetary temperature latitudes and on land also with different humidity. Earth’s species diversity and biomass reaches a peak in shallow waters and with forests, particularly in equatorial, warm and humid conditions. While freezing polar regions and high altitudes, or extremely arid areas are relatively barren of plant and animal life.[242]

Earth provides liquid water—an environment where complex organic molecules can assemble and interact, and sufficient energy to sustain a metabolism.[243] Plants and other organisms take up nutrients from water, soils and the atmosphere. These nutrients are constantly recycled between different species.[244]

Extreme weather, such as tropical cyclones (including hurricanes and typhoons), occurs over most of Earth’s surface and has a large impact on life in those areas. From 1980 to 2000, these events caused an average of 11,800 human deaths per year.[245] Many places are subject to earthquakes, landslides, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, tornadoes, blizzards, floods, droughts, wildfires, and other calamities and disasters.[246] Human impact is felt in many areas due to pollution of the air and water, acid rain, loss of vegetation (overgrazing, deforestation, desertification), loss of wildlife, species extinction, soil degradation, soil depletion and erosion.[247] Human activities release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere which cause global warming.[248] This is driving changes such as the melting of glaciers and ice sheets, a global rise in average sea levels, increased risk of drought and wildfires, and migration of species to colder areas.[249]

Human geography

Originating from earlier primates in eastern Africa 300,000 years ago humans have since been migrating and with the advent of agriculture in the 10th millennium BC increasingly settling Earth’s land. In the 20th century Antarctica had been the last continent to see a first and until today limited human presence.

Human population has since the 19th century grown exponentially to seven billion in the early 2010s,[250] and is projected to peak at around ten billion in the second half of the 21st century.[251] Most of the growth is expected to take place in sub-Saharan Africa.[251]

Distribution and density of human population varies greatly around the world with the majority living in south to eastern Asia and 90% inhabiting only the Northern Hemisphere of Earth,[252] partly due to the hemispherical predominance of the world’s land mass, with 68% of the world’s land mass being in the Northern Hemisphere.[253] Furthermore, since the 19th century humans have increasingly converged into urban areas with the majority living in urban areas by the 21st century.[254]

Beyond Earth’s surface humans have lived on a temporary basis, with only special purpose deep underground and underwater presence, and a few space stations. Human population virtually completely remains on Earth’s surface, fully depending on Earth and the environment it sustains. Humans have gone and temporarily stayed beyond Earth with some hundreds of people, since the latter half of the 20th century, and only a fraction of them reaching another celestial body, the Moon.[255][256]

Earth has been subject to extensive human settlement, and humans have developed diverse societies and cultures. Most of Earth’s land has been territorially claimed since the 19th century by sovereign states (countries) separated by political borders, and more than 200 such states exist today,[257] with only parts of Antarctica and few small regions remaining unclaimed.[258] Most of these states together form the United Nations, the leading worldwide intergovernmental organization,[259] which extends human governance over the ocean and Antarctica, and therefore all of Earth.

Natural resources and land use

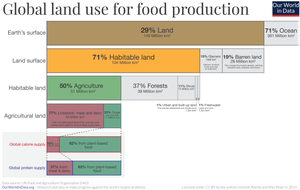

Earth’s land use for human agriculture

Earth has resources that have been exploited by humans.[260] Those termed non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels, are only replenished over geological timescales.[261] Large deposits of fossil fuels are obtained from Earth’s crust, consisting of coal, petroleum, and natural gas.[262] These deposits are used by humans both for energy production and as feedstock for chemical production.[263] Mineral ore bodies have also been formed within the crust through a process of ore genesis, resulting from actions of magmatism, erosion, and plate tectonics.[264] These metals and other elements are extracted by mining, a process which often brings environmental and health damage.[265]

Earth’s biosphere produces many useful biological products for humans, including food, wood, pharmaceuticals, oxygen, and the recycling of organic waste. The land-based ecosystem depends upon topsoil and fresh water, and the oceanic ecosystem depends on dissolved nutrients washed down from the land.[266] In 2019, 39 million km2 (15 million sq mi) of Earth’s land surface consisted of forest and woodlands, 12 million km2 (4.6 million sq mi) was shrub and grassland, 40 million km2 (15 million sq mi) were used for animal feed production and grazing, and 11 million km2 (4.2 million sq mi) were cultivated as croplands.[267] Of the 12–14% of ice-free land that is used for croplands, 2 percentage points were irrigated in 2015.[268] Humans use building materials to construct shelters.[269]

Humans and the environment

Change in average surface air temperature and drivers for that change. Human activity has caused increased temperatures, with natural forces adding some variability.[270]

Human activities have impacted Earth’s environments. Through activities such as the burning of fossil fuels, humans have been increasing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, altering Earth’s energy budget and climate.[248][271] It is estimated that global temperatures in the year 2020 were 1.2 °C (2.2 °F) warmer than the preindustrial baseline.[272] This increase in temperature, known as global warming, has contributed to the melting of glaciers, rising sea levels, increased risk of drought and wildfires, and migration of species to colder areas.[249]

The concept of planetary boundaries was introduced to quantify humanity’s impact on Earth. Of the nine identified boundaries, five have been crossed: Biosphere integrity, climate change, chemical pollution, destruction of wild habitats and the nitrogen cycle are thought to have passed the safe threshold.[273][274] As of 2018, no country meets the basic needs of its population without transgressing planetary boundaries. It is thought possible to provide all basic physical needs globally within sustainable levels of resource use.[275]

Cultural and historical viewpoint

Human cultures have developed many views of the planet.[276] The standard astronomical symbols of Earth are a quartered circle, ,[277] representing the four corners of the world, and a globus cruciger,

. Earth is sometimes personified as a deity. In many cultures it is a mother goddess that is also the primary fertility deity.[278] Creation myths in many religions involve the creation of Earth by a supernatural deity or deities.[278] The Gaia hypothesis, developed in the mid-20th century, compared Earth’s environments and life as a single self-regulating organism leading to broad stabilization of the conditions of habitability.[279][280][281]

Images of Earth taken from space, particularly during the Apollo program, have been credited with altering the way that people viewed the planet that they lived on, called the overview effect, emphasizing its beauty, uniqueness and apparent fragility.[282][283] In particular, this caused a realization of the scope of effects from human activity on Earth’s environment. Enabled by science, particularly Earth observation,[284] humans have started to take action on environmental issues globally,[285] acknowledging the impact of humans and the interconnectedness of Earth’s environments.

Scientific investigation has resulted in several culturally transformative shifts in people’s view of the planet. Initial belief in a flat Earth was gradually displaced in Ancient Greece by the idea of a spherical Earth, which was attributed to both the philosophers Pythagoras and Parmenides.[286][287] Earth was generally believed to be the center of the universe until the 16th century, when scientists first concluded that it was a moving object, one of the planets of the Solar System.[288]

It was only during the 19th century that geologists realized Earth’s age was at least many millions of years.[289] Lord Kelvin used thermodynamics to estimate the age of Earth to be between 20 million and 400 million years in 1864, sparking a vigorous debate on the subject; it was only when radioactivity and radioactive dating were discovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that a reliable mechanism for determining Earth’s age was established, proving the planet to be billions of years old.[290][291]

See also

- Celestial sphere

- Earth phase

- Earth physical characteristics tables

- Earth science

- Extremes on Earth

- List of Solar System extremes

- Outline of Earth

- Table of physical properties of planets in the Solar System

- Timeline of natural history

- Timeline of the far future

Notes

- ^ All astronomical quantities vary, both secularly and periodically. The quantities given are the values at the instant J2000.0 of the secular variation, ignoring all periodic variations.

- ^ aphelion = a × (1 + e); perihelion = a × (1 – e), where a is the semi-major axis and e is the eccentricity. The difference between Earth’s perihelion and aphelion is 5 million kilometers.—Wilkinson, John (2009). Probing the New Solar System. CSIRO Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-643-09949-4.

- ^ a b As of 4 January 2018, the United States Strategic Command tracked a total of 18,835 artificial objects, mostly debris. See: Anz-Meador, Phillip; Shoots, Debi, eds. (February 2018). «Satellite Box Score» (PDF). Orbital Debris Quarterly News. 22 (1): 12. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Earth’s circumference is almost exactly 40,000 km because the meter was calibrated on this measurement—more specifically, 1/10-millionth of the distance between the poles and the equator.

- ^ Due to natural fluctuations, ambiguities surrounding ice shelves, and mapping conventions for vertical datums, exact values for land and ocean coverage are not meaningful. Based on data from the Vector Map and Global Landcover Archived 26 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine datasets, extreme values for coverage of lakes and streams are 0.6% and 1.0% of Earth’s surface. The ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland are counted as land, even though much of the rock that supports them lies below sea level.

- ^ If Earth were shrunk to the size of a billiard ball, some areas of Earth such as large mountain ranges and oceanic trenches would feel like tiny imperfections, whereas much of the planet, including the Great Plains and the abyssal plains, would feel smoother.[91]

- ^ Including the Somali Plate, which is being formed out of the African Plate. See: Chorowicz, Jean (October 2005). «The East African rift system». Journal of African Earth Sciences. 43 (1–3): 379–410. Bibcode:2005JAfES..43..379C. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.019.

- ^ Locally varies between 5 and 200 km.

- ^ Locally varies between 5 and 70 km.

- ^ The ultimate source of these figures, uses the term «seconds of UT1» instead of «seconds of mean solar time».—Aoki, S.; Kinoshita, H.; Guinot, B.; Kaplan, G. H.; McCarthy, D. D.; Seidelmann, P. K. (1982). «The new definition of universal time». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 105 (2): 359–61. Bibcode:1982A&A…105..359A.

- ^ For Earth, the Hill radius is

, where m is the mass of Earth, a is an astronomical unit, and M is the mass of the Sun. So the radius in AU is about

.

- ^ Aphelion is 103.4% of the distance to perihelion. Due to the inverse square law, the radiation at perihelion is about 106.9% of the energy at aphelion.

References

- ^ Petsko, Gregory A. (28 April 2011). «The blue marble». Genome Biology. 12 (4): 112. doi:10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-112. PMC 3218853. PMID 21554751.

- ^ «Apollo Imagery – AS17-148-22727». NASA. 1 November 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b Simon, J.L.; et al. (February 1994). «Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets». Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–83. Bibcode:1994A&A…282..663S.

- ^ a b c d e Staff (13 March 2021). «Useful Constants». International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Williams, David R. (16 March 2017). «Earth Fact Sheet». NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Allen, Clabon Walter; Cox, Arthur N. (2000). Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities. Springer. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-387-98746-0. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ «HORIZONS Batch call for 2023 perihelion». ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA/JPL. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b «UCS Satellite Database». Nuclear Weapons & Global Security. Union of Concerned Scientists. 1 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Various (2000). David R. Lide (ed.). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0481-1.

- ^ «Selected Astronomical Constants, 2011». The Astronomical Almanac. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b World Geodetic System (WGS-84). Available online Archived 11 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine from National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

- ^ Cazenave, Anny (1995). «Geoid, Topography and Distribution of Landforms» (PDF). In Ahrens, Thomas J (ed.). Global Earth Physics: A Handbook of Physical Constants. Global Earth Physics: A Handbook of Physical Constants. AGU Reference Shelf. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union. Bibcode:1995geph.conf…..A. doi:10.1029/RF001. ISBN 978-0-87590-851-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) Working Group (2004). «General Definitions and Numerical Standards» (PDF). In McCarthy, Dennis D.; Petit, Gérard (eds.). IERS Conventions (2003) (PDF). IERS Technical Note No. 32. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag des Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-89888-884-4. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Humerfelt, Sigurd (26 October 2010). «How WGS 84 defines Earth». Home Online. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ a b Pidwirny, Michael (2 February 2006). «Surface area of our planet covered by oceans and continents.(Table 8o-1)». University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ «Planetary Physical Parameters». Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ The international system of units (SI) (PDF) (2008 ed.). United States Department of Commerce, NIST Special Publication 330. p. 52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009.

- ^ Williams, James G. (1994). «Contributions to the Earth’s obliquity rate, precession, and nutation». The Astronomical Journal. 108: 711. Bibcode:1994AJ….108..711W. doi:10.1086/117108. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 122370108.

- ^ Allen, Clabon Walter; Cox, Arthur N. (2000). Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities. Springer. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-387-98746-0. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Arthur N. Cox, ed. (2000). Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities (4th ed.). New York: AIP Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-387-98746-0. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ «Atmospheres and Planetary Temperatures». American Chemical Society. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ «World: Lowest Temperature». WMO Weather and Climate Extremes Archive. Arizona State University. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Jones, P. D.; Harpham, C. (2013). «Estimation of the absolute surface air temperature of the Earth». Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 118 (8): 3213–3217. Bibcode:2013JGRD..118.3213J. doi:10.1002/jgrd.50359. ISSN 2169-8996.

- ^ «World: Highest Temperature». WMO Weather and Climate Extremes Archive. Arizona State University. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (2008). Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. New York: United Nations (published 2010). Table 1. ISBN 978-92-1-142274-0. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ «Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide: Recent Global CO2 Trend». Earth System Research Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 19 October 2020. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020.

- ^ Nations, United. «What Is Climate Change?». United Nations. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b «earth, n.¹«. Oxford English Dictionary (3 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 2010. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3.

- ^ Simek, Rudolf (2007). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Hall, Angela. D.S. Brewer. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-85991-513-7.

- ^ «earth». The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6.

- ^ «Terra». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Tellus». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Gaia». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Terran». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «terrestrial». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «terrene». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «tellurian». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «telluric». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021.

- ^ Bouvier, Audrey; Wadhwa, Meenakshi (September 2010). «The age of the Solar System redefined by the oldest Pb–Pb age of a meteoritic inclusion». Nature Geoscience. 3 (9): 637–41. Bibcode:2010NatGe…3..637B. doi:10.1038/ngeo941.

- ^ See:

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (1991). The Age of the Earth. California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1569-0.

- Newman, William L. (9 July 2007). «Age of the Earth». Publications Services, USGS. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). «The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved». Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 190 (1): 205–21. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ Righter, K.; Schonbachler, M. (7 May 2018). «Ag Isotopic Evolution of the Mantle During Accretion: New Constraints from Pd and Ag Metal-Silicate Partitioning». Differentiation: Building the Internal Architecture of Planets. 2084: 4034. Bibcode:2018LPICo2084.4034R. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Tartèse, Romain; Anand, Mahesh; Gattacceca, Jérôme; Joy, Katherine H.; Mortimer, James I.; Pernet-Fisher, John F.; Russell, Sara; Snape, Joshua F.; Weiss, Benjamin P. (2019). «Constraining the Evolutionary History of the Moon and the Inner Solar System: A Case for New Returned Lunar Samples». Space Science Reviews. 215 (8): 54. Bibcode:2019SSRv..215…54T. doi:10.1007/s11214-019-0622-x. ISSN 1572-9672.

- ^ Reilly, Michael (22 October 2009). «Controversial Moon Origin Theory Rewrites History». Discovery News. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ a b Canup, R.; Asphaug, E. I. (2001). «Origin of the Moon in a giant impact near the end of the Earth’s formation». Nature. 412 (6848): 708–12. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..708C. doi:10.1038/35089010. PMID 11507633. S2CID 4413525.

- ^ Meier, M. M. M.; Reufer, A.; Wieler, R. (4 August 2014). «On the origin and composition of Theia: Constraints from new models of the Giant Impact». Icarus. 242: 5. arXiv:1410.3819. Bibcode:2014Icar..242..316M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.08.003. S2CID 119226112.

- ^ Claeys, Philippe; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2011). «Late Heavy Bombardment». In Gargaud, Muriel; Amils, Prof Ricardo; Quintanilla, José Cernicharo; Cleaves II, Henderson James (Jim); Irvine, William M.; Pinti, Prof Daniele L.; Viso, Michel (eds.). Encyclopedia of Astrobiology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 909–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11274-4_869. ISBN 978-3-642-11271-3.

- ^ Trainer, Melissa G.; et al. (28 November 2006). «Organic haze on Titan and the early Earth». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (48): 18035–18042. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608561103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1838702. PMID 17101962.

- ^ «Earth’s Early Atmosphere and Oceans». Lunar and Planetary Institute. Universities Space Research Association. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ Morbidelli, A.; et al. (2000). «Source regions and time scales for the delivery of water to Earth». Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 35 (6): 1309–20. Bibcode:2000M&PS…35.1309M. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2000.tb01518.x.

- ^ Piani, Laurette; et al. (2020). «Earth’s water may have been inherited from material similar to enstatite chondrite meteorites». Science. 369 (6507): 1110–13. Bibcode:2020Sci…369.1110P. doi:10.1126/science.aba1948. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32855337. S2CID 221342529.

- ^ Guinan, E. F.; Ribas, I. (2002). Benjamin Montesinos, Alvaro Gimenez and Edward F. Guinan (ed.). Our Changing Sun: The Role of Solar Nuclear Evolution and Magnetic Activity on Earth’s Atmosphere and Climate. ASP Conference Proceedings: The Evolving Sun and its Influence on Planetary Environments. San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Bibcode:2002ASPC..269…85G. ISBN 978-1-58381-109-2.

- ^ Staff (4 March 2010). «Oldest measurement of Earth’s magnetic field reveals battle between Sun and Earth for our atmosphere». Phys.org. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b Harrison, T. M.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Müller, W.; Albarede, F.; Holden, P.; Mojzsis, S. (December 2005). «Heterogeneous Hadean hafnium: evidence of continental crust at 4.4 to 4.5 ga». Science. 310 (5756): 1947–50. Bibcode:2005Sci…310.1947H. doi:10.1126/science.1117926. PMID 16293721. S2CID 11208727.

- ^

- ^ Hurley, P. M.; Rand, J. R. (June 1969). «Pre-drift continental nuclei». Science. 164 (3885): 1229–42. Bibcode:1969Sci…164.1229H. doi:10.1126/science.164.3885.1229. PMID 17772560.

- ^ Armstrong, R. L. (1991). «The persistent myth of crustal growth» (PDF). Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 38 (5): 613–30. Bibcode:1991AuJES..38..613A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.9577. doi:10.1080/08120099108727995.

- ^ De Smet, J.; Van Den Berg, A.P.; Vlaar, N.J. (2000). «Early formation and long-term stability of continents resulting from decompression melting in a convecting mantle» (PDF). Tectonophysics. 322 (1–2): 19–33. Bibcode:2000Tectp.322…19D. doi:10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00055-X. hdl:1874/1653.