Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a «work» (the literal translation of the Italian word «opera») is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librettist[1] and incorporates a number of the performing arts, such as acting, scenery, costume, and sometimes dance or ballet. The performance is typically given in an opera house, accompanied by an orchestra or smaller musical ensemble, which since the early 19th century has been led by a conductor. Although musical theatre is closely related to opera, the two are considered to be distinct from one another.[2]

Opera is a key part of the Western classical music tradition.[3] Originally understood as an entirely sung piece, in contrast to a play with songs, opera has come to include numerous genres, including some that include spoken dialogue such as Singspiel and Opéra comique. In traditional number opera, singers employ two styles of singing: recitative, a speech-inflected style,[4] and self-contained arias. The 19th century saw the rise of the continuous music drama.

Opera originated in Italy at the end of the 16th century (with Jacopo Peri’s mostly lost Dafne, produced in Florence in 1598) especially from works by Claudio Monteverdi, notably L’Orfeo, and soon spread through the rest of Europe: Heinrich Schütz in Germany, Jean-Baptiste Lully in France, and Henry Purcell in England all helped to establish their national traditions in the 17th century. In the 18th century, Italian opera continued to dominate most of Europe (except France), attracting foreign composers such as George Frideric Handel. Opera seria was the most prestigious form of Italian opera, until Christoph Willibald Gluck reacted against its artificiality with his «reform» operas in the 1760s. The most renowned figure of late 18th-century opera is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who began with opera seria but is most famous for his Italian comic operas, especially The Marriage of Figaro (Le nozze di Figaro), Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte, as well as Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), and The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte), landmarks in the German tradition.

The first third of the 19th century saw the high point of the bel canto style, with Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini all creating signature works of that style. It also saw the advent of grand opera typified by the works of Daniel Auber and Giacomo Meyerbeer as well as Carl Maria von Weber’s introduction of German Romantische Oper (German Romantic Opera). The mid-to-late 19th century was a golden age of opera, led and dominated by Giuseppe Verdi in Italy and Richard Wagner in Germany. The popularity of opera continued through the verismo era in Italy and contemporary French opera through to Giacomo Puccini and Richard Strauss in the early 20th century. During the 19th century, parallel operatic traditions emerged in central and eastern Europe, particularly in Russia and Bohemia. The 20th century saw many experiments with modern styles, such as atonality and serialism (Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg), neoclassicism (Igor Stravinsky), and minimalism (Philip Glass and John Adams). With the rise of recording technology, singers such as Enrico Caruso and Maria Callas became known to much wider audiences that went beyond the circle of opera fans. Since the invention of radio and television, operas were also performed on (and written for) these media. Beginning in 2006, a number of major opera houses began to present live high-definition video transmissions of their performances in cinemas all over the world. Since 2009, complete performances can be downloaded and are live streamed.

Operatic terminology[edit]

The words of an opera are known as the libretto (meaning «small book»). Some composers, notably Wagner, have written their own libretti; others have worked in close collaboration with their librettists, e.g. Mozart with Lorenzo Da Ponte. Traditional opera, often referred to as «number opera», consists of two modes of singing: recitative, the plot-driving passages sung in a style designed to imitate and emphasize the inflections of speech,[4] and aria (an «air» or formal song) in which the characters express their emotions in a more structured melodic style. Vocal duets, trios and other ensembles often occur, and choruses are used to comment on the action. In some forms of opera, such as singspiel, opéra comique, operetta, and semi-opera, the recitative is mostly replaced by spoken dialogue. Melodic or semi-melodic passages occurring in the midst of, or instead of, recitative, are also referred to as arioso. The terminology of the various kinds of operatic voices is described in detail below.[5] During both the Baroque and Classical periods, recitative could appear in two basic forms, each of which was accompanied by a different instrumental ensemble: secco (dry) recitative, sung with a free rhythm dictated by the accent of the words, accompanied only by basso continuo, which was usually a harpsichord and a cello; or accompagnato (also known as strumentato) in which the orchestra provided accompaniment. Over the 18th century, arias were increasingly accompanied by the orchestra. By the 19th century, accompagnato had gained the upper hand, the orchestra played a much bigger role, and Wagner revolutionized opera by abolishing almost all distinction between aria and recitative in his quest for what Wagner termed «endless melody». Subsequent composers have tended to follow Wagner’s example, though some, such as Stravinsky in his The Rake’s Progress have bucked the trend. The changing role of the orchestra in opera is described in more detail below.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The Italian word opera means «work», both in the sense of the labour done and the result produced. The Italian word derives from the Latin word opera, a singular noun meaning «work» and also the plural of the noun opus. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Italian word was first used in the sense «composition in which poetry, dance, and music are combined» in 1639; the first recorded English usage in this sense dates to 1648.[6]

Dafne by Jacopo Peri was the earliest composition considered opera, as understood today. It was written around 1597, largely under the inspiration of an elite circle of literate Florentine humanists who gathered as the «Camerata de’ Bardi». Significantly, Dafne was an attempt to revive the classical Greek drama, part of the wider revival of antiquity characteristic of the Renaissance. The members of the Camerata considered that the «chorus» parts of Greek dramas were originally sung, and possibly even the entire text of all roles; opera was thus conceived as a way of «restoring» this situation. Dafne, however, is lost. A later work by Peri, Euridice, dating from 1600, is the first opera score to have survived until the present day. However, the honour of being the first opera still to be regularly performed goes to Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, composed for the court of Mantua in 1607.[7] The Mantua court of the Gonzagas, employers of Monteverdi, played a significant role in the origin of opera employing not only court singers of the concerto delle donne (till 1598), but also one of the first actual «opera singers», Madama Europa.[8]

Italian opera[edit]

Baroque era[edit]

Opera did not remain confined to court audiences for long. In 1637, the idea of a «season» (often during the carnival) of publicly attended operas supported by ticket sales emerged in Venice. Monteverdi had moved to the city from Mantua and composed his last operas, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria and L’incoronazione di Poppea, for the Venetian theatre in the 1640s. His most important follower Francesco Cavalli helped spread opera throughout Italy. In these early Baroque operas, broad comedy was blended with tragic elements in a mix that jarred some educated sensibilities, sparking the first of opera’s many reform movements, sponsored by the Arcadian Academy, which came to be associated with the poet Metastasio, whose libretti helped crystallize the genre of opera seria, which became the leading form of Italian opera until the end of the 18th century. Once the Metastasian ideal had been firmly established, comedy in Baroque-era opera was reserved for what came to be called opera buffa. Before such elements were forced out of opera seria, many libretti had featured a separately unfolding comic plot as sort of an «opera-within-an-opera». One reason for this was an attempt to attract members of the growing merchant class, newly wealthy, but still not as cultured as the nobility, to the public opera houses. These separate plots were almost immediately resurrected in a separately developing tradition that partly derived from the commedia dell’arte, a long-flourishing improvisatory stage tradition of Italy. Just as intermedi had once been performed in between the acts of stage plays, operas in the new comic genre of intermezzi, which developed largely in Naples in the 1710s and 1720s, were initially staged during the intermissions of opera seria. They became so popular, however, that they were soon being offered as separate productions.

Opera seria was elevated in tone and highly stylised in form, usually consisting of secco recitative interspersed with long da capo arias. These afforded great opportunity for virtuosic singing and during the golden age of opera seria the singer really became the star. The role of the hero was usually written for the high-pitched male castrato voice, which was produced by castration of the singer before puberty, which prevented a boy’s larynx from being transformed at puberty. Castrati such as Farinelli and Senesino, as well as female sopranos such as Faustina Bordoni, became in great demand throughout Europe as opera seria ruled the stage in every country except France. Farinelli was one of the most famous singers of the 18th century. Italian opera set the Baroque standard. Italian libretti were the norm, even when a German composer like Handel found himself composing the likes of Rinaldo and Giulio Cesare for London audiences. Italian libretti remained dominant in the classical period as well, for example in the operas of Mozart, who wrote in Vienna near the century’s close. Leading Italian-born composers of opera seria include Alessandro Scarlatti, Antonio Vivaldi and Nicola Porpora.[9]

Gluck’s reforms and Mozart[edit]

Opera seria had its weaknesses and critics. The taste for embellishment on behalf of the superbly trained singers, and the use of spectacle as a replacement for dramatic purity and unity drew attacks. Francesco Algarotti’s Essay on the Opera (1755) proved to be an inspiration for Christoph Willibald Gluck’s reforms. He advocated that opera seria had to return to basics and that all the various elements—music (both instrumental and vocal), ballet, and staging—must be subservient to the overriding drama. In 1765 Melchior Grimm published «Poème lyrique«, an influential article for the Encyclopédie on lyric and opera librettos.[10][11][12][13][14] Several composers of the period, including Niccolò Jommelli and Tommaso Traetta, attempted to put these ideals into practice. The first to succeed however, was Gluck. Gluck strove to achieve a «beautiful simplicity». This is evident in his first reform opera, Orfeo ed Euridice, where his non-virtuosic vocal melodies are supported by simple harmonies and a richer orchestra presence throughout.

Gluck’s reforms have had resonance throughout operatic history. Weber, Mozart, and Wagner, in particular, were influenced by his ideals. Mozart, in many ways Gluck’s successor, combined a superb sense of drama, harmony, melody, and counterpoint to write a series of comic operas with libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte, notably Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte, which remain among the most-loved, popular and well-known operas. But Mozart’s contribution to opera seria was more mixed; by his time it was dying away, and in spite of such fine works as Idomeneo and La clemenza di Tito, he would not succeed in bringing the art form back to life again.[15]

Bel canto, Verdi and verismo[edit]

The bel canto opera movement flourished in the early 19th century and is exemplified by the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Pacini, Mercadante and many others. Literally «beautiful singing», bel canto opera derives from the Italian stylistic singing school of the same name. Bel canto lines are typically florid and intricate, requiring supreme agility and pitch control. Examples of famous operas in the bel canto style include Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia and La Cenerentola, as well as Bellini’s Norma, La sonnambula and I puritani and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, L’elisir d’amore and Don Pasquale.

Following the bel canto era, a more direct, forceful style was rapidly popularized by Giuseppe Verdi, beginning with his biblical opera Nabucco. This opera, and the ones that would follow in Verdi’s career, revolutionized Italian opera, changing it from merely a display of vocal fireworks, with Rossini’s and Donizetti’s works, to dramatic story-telling. Verdi’s operas resonated with the growing spirit of Italian nationalism in the post-Napoleonic era, and he quickly became an icon of the patriotic movement for a unified Italy. In the early 1850s, Verdi produced his three most popular operas: Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata. The first of these, Rigoletto, proved the most daring and revolutionary. In it, Verdi blurs the distinction between the aria and recitative as it never before was, leading the opera to be «an unending string of duets». La traviata was also novel. It tells the story of courtesan, and is often cited as one of the first «realistic» operas,[citation needed] because rather than featuring great kings and figures from literature, it focuses on the tragedies of ordinary life and society. After these, he continued to develop his style, composing perhaps the greatest French grand opera, Don Carlos, and ending his career with two Shakespeare-inspired works, Otello and Falstaff, which reveal how far Italian opera had grown in sophistication since the early 19th century. These final two works showed Verdi at his most masterfully orchestrated, and are both incredibly influential, and modern. In Falstaff, Verdi sets the preeminent standard for the form and style that would dominate opera throughout the twentieth century. Rather than long, suspended melodies, Falstaff contains many little motifs and mottos, that, rather than being expanded upon, are introduced and subsequently dropped, only to be brought up again later. These motifs never are expanded upon, and just as the audience expects a character to launch into a long melody, a new character speaks, introducing a new phrase. This fashion of opera directed opera from Verdi, onward, exercising tremendous influence on his successors Giacomo Puccini, Richard Strauss, and Benjamin Britten.[16]

After Verdi, the sentimental «realistic» melodrama of verismo appeared in Italy. This was a style introduced by Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci that came to dominate the world’s opera stages with such popular works as Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly. Later Italian composers, such as Berio and Nono, have experimented with modernism.[17]

German-language opera[edit]

The first German opera was Dafne, composed by Heinrich Schütz in 1627, but the music score has not survived. Italian opera held a great sway over German-speaking countries until the late 18th century. Nevertheless, native forms would develop in spite of this influence. In 1644, Sigmund Staden produced the first Singspiel, Seelewig, a popular form of German-language opera in which singing alternates with spoken dialogue. In the late 17th century and early 18th century, the Theater am Gänsemarkt in Hamburg presented German operas by Keiser, Telemann and Handel. Yet most of the major German composers of the time, including Handel himself, as well as Graun, Hasse and later Gluck, chose to write most of their operas in foreign languages, especially Italian. In contrast to Italian opera, which was generally composed for the aristocratic class, German opera was generally composed for the masses and tended to feature simple folk-like melodies, and it was not until the arrival of Mozart that German opera was able to match its Italian counterpart in musical sophistication.[18] The theatre company of Abel Seyler pioneered serious German-language opera in the 1770s, marking a break with the previous simpler musical entertainment.[19][20]

Mozart’s Singspiele, Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782) and Die Zauberflöte (1791) were an important breakthrough in achieving international recognition for German opera. The tradition was developed in the 19th century by Beethoven with his Fidelio (1805), inspired by the climate of the French Revolution. Carl Maria von Weber established German Romantic opera in opposition to the dominance of Italian bel canto. His Der Freischütz (1821) shows his genius for creating a supernatural atmosphere. Other opera composers of the time include Marschner, Schubert and Lortzing, but the most significant figure was undoubtedly Wagner.

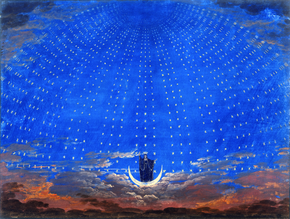

Brünnhilde throws herself on Siegfried’s funeral pyre in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

Wagner was one of the most revolutionary and controversial composers in musical history. Starting under the influence of Weber and Meyerbeer, he gradually evolved a new concept of opera as a Gesamtkunstwerk (a «complete work of art»), a fusion of music, poetry and painting. He greatly increased the role and power of the orchestra, creating scores with a complex web of leitmotifs, recurring themes often associated with the characters and concepts of the drama, of which prototypes can be heard in his earlier operas such as Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin; and he was prepared to violate accepted musical conventions, such as tonality, in his quest for greater expressivity. In his mature music dramas, Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal, he abolished the distinction between aria and recitative in favour of a seamless flow of «endless melody». Wagner also brought a new philosophical dimension to opera in his works, which were usually based on stories from Germanic or Arthurian legend. Finally, Wagner built his own opera house at Bayreuth with part of the patronage from Ludwig II of Bavaria, exclusively dedicated to performing his own works in the style he wanted.

Opera would never be the same after Wagner and for many composers his legacy proved a heavy burden. On the other hand, Richard Strauss accepted Wagnerian ideas but took them in wholly new directions, along with incorporating the new form introduced by Verdi. He first won fame with the scandalous Salome and the dark tragedy Elektra, in which tonality was pushed to the limits. Then Strauss changed tack in his greatest success, Der Rosenkavalier, where Mozart and Viennese waltzes became as important an influence as Wagner. Strauss continued to produce a highly varied body of operatic works, often with libretti by the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Other composers who made individual contributions to German opera in the early 20th century include Alexander von Zemlinsky, Erich Korngold, Franz Schreker, Paul Hindemith, Kurt Weill and the Italian-born Ferruccio Busoni. The operatic innovations of Arnold Schoenberg and his successors are discussed in the section on modernism.[21]

During the late 19th century, the Austrian composer Johann Strauss II, an admirer of the French-language operettas composed by Jacques Offenbach, composed several German-language operettas, the most famous of which was Die Fledermaus.[22] Nevertheless, rather than copying the style of Offenbach, the operettas of Strauss II had distinctly Viennese flavor to them.

French opera[edit]

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian-born French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully at the court of King Louis XIV. Despite his foreign birthplace, Lully established an Academy of Music and monopolised French opera from 1672. Starting with Cadmus et Hermione, Lully and his librettist Quinault created tragédie en musique, a form in which dance music and choral writing were particularly prominent. Lully’s operas also show a concern for expressive recitative which matched the contours of the French language. In the 18th century, Lully’s most important successor was Jean-Philippe Rameau, who composed five tragédies en musique as well as numerous works in other genres such as opéra-ballet, all notable for their rich orchestration and harmonic daring. Despite the popularity of Italian opera seria throughout much of Europe during the Baroque period, Italian opera never gained much of a foothold in France, where its own national operatic tradition was more popular instead.[23] After Rameau’s death, the German Gluck was persuaded to produce six operas for the Parisian stage in the 1770s. They show the influence of Rameau, but simplified and with greater focus on the drama. At the same time, by the middle of the 18th century another genre was gaining popularity in France: opéra comique. This was the equivalent of the German singspiel, where arias alternated with spoken dialogue. Notable examples in this style were produced by Monsigny, Philidor and, above all, Grétry. During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic period, composers such as Étienne Méhul, Luigi Cherubini and Gaspare Spontini, who were followers of Gluck, brought a new seriousness to the genre, which had never been wholly «comic» in any case. Another phenomenon of this period was the ‘propaganda opera’ celebrating revolutionary successes, e.g. Gossec’s Le triomphe de la République (1793).

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian bel canto, especially after the arrival of Rossini in Paris. Rossini’s Guillaume Tell helped found the new genre of grand opera, a form whose most famous exponent was another foreigner, Giacomo Meyerbeer. Meyerbeer’s works, such as Les Huguenots, emphasised virtuoso singing and extraordinary stage effects. Lighter opéra comique also enjoyed tremendous success in the hands of Boïeldieu, Auber, Hérold and Adam. In this climate, the operas of the French-born composer Hector Berlioz struggled to gain a hearing. Berlioz’s epic masterpiece Les Troyens, the culmination of the Gluckian tradition, was not given a full performance for almost a hundred years.

In the second half of the 19th century, Jacques Offenbach created operetta with witty and cynical works such as Orphée aux enfers, as well as the opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann; Charles Gounod scored a massive success with Faust; and Georges Bizet composed Carmen, which, once audiences learned to accept its blend of Romanticism and realism, became the most popular of all opéra comiques. Jules Massenet, Camille Saint-Saëns and Léo Delibes all composed works which are still part of the standard repertory, examples being Massenet’s Manon, Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila and Delibes’ Lakmé. Their operas formed another genre, the Opera Lyrique, combined opera comique and grand opera. It is less grandiose than grand opera, but without the spoken dialogue of opera comique. At the same time, the influence of Richard Wagner was felt as a challenge to the French tradition. Many French critics angrily rejected Wagner’s music dramas while many French composers closely imitated them with variable success. Perhaps the most interesting response came from Claude Debussy. As in Wagner’s works, the orchestra plays a leading role in Debussy’s unique opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) and there are no real arias, only recitative. But the drama is understated, enigmatic and completely un-Wagnerian.

Other notable 20th-century names include Ravel, Dukas, Roussel, Honegger and Milhaud. Francis Poulenc is one of the very few post-war composers of any nationality whose operas (which include Dialogues des Carmélites) have gained a foothold in the international repertory. Olivier Messiaen’s lengthy sacred drama Saint François d’Assise (1983) has also attracted widespread attention.[24]

English-language opera[edit]

Scene from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. The witches’ messenger, in the form of Mercury himself, attempts to convince Aeneas to leave Carthage.

In England, opera’s antecedent was the 17th-century jig. This was an afterpiece that came at the end of a play. It was frequently libellous and scandalous and consisted in the main of dialogue set to music arranged from popular tunes. In this respect, jigs anticipate the ballad operas of the 18th century. At the same time, the French masque was gaining a firm hold at the English Court, with even more lavish splendour and highly realistic scenery than had been seen before. Inigo Jones became the quintessential designer of these productions, and this style was to dominate the English stage for three centuries. These masques contained songs and dances. In Ben Jonson’s Lovers Made Men (1617), «the whole masque was sung after the Italian manner, stilo recitativo».[25] The approach of the English Commonwealth closed theatres and halted any developments that may have led to the establishment of English opera. However, in 1656, the dramatist Sir William Davenant produced The Siege of Rhodes. Since his theatre was not licensed to produce drama, he asked several of the leading composers (Lawes, Cooke, Locke, Coleman and Hudson) to set sections of it to music. This success was followed by The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru (1658) and The History of Sir Francis Drake (1659). These pieces were encouraged by Oliver Cromwell because they were critical of Spain. With the English Restoration, foreign (especially French) musicians were welcomed back. In 1673, Thomas Shadwell’s Psyche, patterned on the 1671 ‘comédie-ballet’ of the same name produced by Molière and Jean-Baptiste Lully. William Davenant produced The Tempest in the same year, which was the first musical adaption of a Shakespeare play (composed by Locke and Johnson).[25] About 1683, John Blow composed Venus and Adonis, often thought of as the first true English-language opera.

Blow’s immediate successor was the better known Henry Purcell. Despite the success of his masterwork Dido and Aeneas (1689), in which the action is furthered by the use of Italian-style recitative, much of Purcell’s best work was not involved in the composing of typical opera, but instead, he usually worked within the constraints of the semi-opera format, where isolated scenes and masques are contained within the structure of a spoken play, such as Shakespeare in Purcell’s The Fairy-Queen (1692) and Beaumont and Fletcher in The Prophetess (1690) and Bonduca (1696). The main characters of the play tend not to be involved in the musical scenes, which means that Purcell was rarely able to develop his characters through song. Despite these hindrances, his aim (and that of his collaborator John Dryden) was to establish serious opera in England, but these hopes ended with Purcell’s early death at the age of 36.

Following Purcell, the popularity of opera in England dwindled for several decades. A revived interest in opera occurred in the 1730s which is largely attributed to Thomas Arne, both for his own compositions and for alerting Handel to the commercial possibilities of large-scale works in English. Arne was the first English composer to experiment with Italian-style all-sung comic opera, with his greatest success being Thomas and Sally in 1760. His opera Artaxerxes (1762) was the first attempt to set a full-blown opera seria in English and was a huge success, holding the stage until the 1830s. Although Arne imitated many elements of Italian opera, he was perhaps the only English composer at that time who was able to move beyond the Italian influences and create his own unique and distinctly English voice. His modernized ballad opera, Love in a Village (1762), began a vogue for pastiche opera that lasted well into the 19th century. Charles Burney wrote that Arne introduced «a light, airy, original, and pleasing melody, wholly different from that of Purcell or Handel, whom all English composers had either pillaged or imitated».

Besides Arne, the other dominating force in English opera at this time was George Frideric Handel, whose opera serias filled the London operatic stages for decades and influenced most home-grown composers, like John Frederick Lampe, who wrote using Italian models. This situation continued throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, including in the work of Michael William Balfe, and the operas of the great Italian composers, as well as those of Mozart, Beethoven, and Meyerbeer, continued to dominate the musical stage in England.

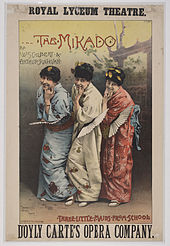

The only exceptions were ballad operas, such as John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728), musical burlesques, European operettas, and late Victorian era light operas, notably the Savoy Operas of W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, all of which types of musical entertainments frequently spoofed operatic conventions. Sullivan wrote only one grand opera, Ivanhoe (following the efforts of a number of young English composers beginning about 1876),[25] but he claimed that even his light operas constituted part of a school of «English» opera, intended to supplant the French operettas (usually performed in bad translations) that had dominated the London stage from the mid-19th century into the 1870s. London’s Daily Telegraph agreed, describing The Yeomen of the Guard as «a genuine English opera, forerunner of many others, let us hope, and possibly significant of an advance towards a national lyric stage».[26] Sullivan produced a few light operas in the 1890s that were of a more serious nature than those in the G&S series, including Haddon Hall and The Beauty Stone, but Ivanhoe (which ran for 155 consecutive performances, using alternating casts—a record until Broadway’s La bohème) survives as his only grand opera.

In the 20th century, English opera began to assert more independence, with works of Ralph Vaughan Williams and in particular Benjamin Britten, who in a series of works that remain in standard repertory today, revealed an excellent flair for the dramatic and superb musicality. More recently Sir Harrison Birtwistle has emerged as one of Britain’s most significant contemporary composers from his first opera Punch and Judy to his most recent critical success in The Minotaur. In the first decade of the 21st century, the librettist of an early Birtwistle opera, Michael Nyman, has been focusing on composing operas, including Facing Goya, Man and Boy: Dada, and Love Counts. Today composers such as Thomas Adès continue to export English opera abroad.[27]

Also in the 20th century, American composers like George Gershwin (Porgy and Bess), Scott Joplin (Treemonisha), Leonard Bernstein (Candide), Gian Carlo Menotti, Douglas Moore, and Carlisle Floyd began to contribute English-language operas infused with touches of popular musical styles. They were followed by composers such as Philip Glass (Einstein on the Beach), Mark Adamo, John Corigliano (The Ghosts of Versailles), Robert Moran, John Adams (Nixon in China), André Previn and Jake Heggie. Many contemporary 21st century opera composers have emerged such as Missy Mazzoli, Kevin Puts, Tom Cipullo, Huang Ruo, David T. Little, Terence Blanchard, Jennifer Higdon, Tobias Picker, Michael Ching, Anthony Davis, and Ricky Ian Gordon.

Russian opera[edit]

Opera was brought to Russia in the 1730s by the Italian operatic troupes and soon it became an important part of entertainment for the Russian Imperial Court and aristocracy. Many foreign composers such as Baldassare Galuppi, Giovanni Paisiello, Giuseppe Sarti, and Domenico Cimarosa (as well as various others) were invited to Russia to compose new operas, mostly in the Italian language. Simultaneously some domestic musicians like Maksym Berezovsky and Dmitry Bortniansky were sent abroad to learn to write operas. The first opera written in Russian was Tsefal i Prokris by the Italian composer Francesco Araja (1755). The development of Russian-language opera was supported by the Russian composers Vasily Pashkevich, Yevstigney Fomin and Alexey Verstovsky.

However, the real birth of Russian opera came with Mikhail Glinka and his two great operas A Life for the Tsar (1836) and Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842). After him, during the 19th century in Russia, there were written such operatic masterpieces as Rusalka and The Stone Guest by Alexander Dargomyzhsky, Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina by Modest Mussorgsky, Prince Igor by Alexander Borodin, Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, and The Snow Maiden and Sadko by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. These developments mirrored the growth of Russian nationalism across the artistic spectrum, as part of the more general Slavophilism movement.

In the 20th century, the traditions of Russian opera were developed by many composers including Sergei Rachmaninoff in his works The Miserly Knight and Francesca da Rimini, Igor Stravinsky in Le Rossignol, Mavra, Oedipus rex, and The Rake’s Progress, Sergei Prokofiev in The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, The Fiery Angel, Betrothal in a Monastery, and War and Peace; as well as Dmitri Shostakovich in The Nose and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Edison Denisov in L’écume des jours, and Alfred Schnittke in Life with an Idiot and Historia von D. Johann Fausten.[28]

Czech opera[edit]

Czech composers also developed a thriving national opera movement of their own in the 19th century, starting with Bedřich Smetana, who wrote eight operas including the internationally popular The Bartered Bride. Smetana’s eight operas created the bedrock of the Czech opera repertory, but of these only The Bartered Bride is performed regularly outside the composer’s homeland. After reaching Vienna in 1892 and London in 1895 it rapidly became part of the repertory of every major opera company worldwide.

Antonín Dvořák’s nine operas, except his first, have librettos in Czech and were intended to convey the Czech national spirit, as were some of his choral works. By far the most successful of the operas is Rusalka which contains the well-known aria «Měsíčku na nebi hlubokém» («Song to the Moon»); it is played on contemporary opera stages frequently outside the Czech Republic. This is attributable to their uneven invention and libretti, and perhaps also their staging requirements – The Jacobin, Armida, Vanda and Dimitrij need stages large enough to portray invading armies.

Leoš Janáček gained international recognition in the 20th century for his innovative works. His later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the opera Jenůfa, which was premiered in 1904 in Brno. The success of Jenůfa (often called the «Moravian national opera») at Prague in 1916 gave Janáček access to the world’s great opera stages. Janáček’s later works are his most celebrated. They include operas such as Káťa Kabanová and The Cunning Little Vixen, the Sinfonietta and the Glagolitic Mass.

Other national operas[edit]

Spain also produced its own distinctive form of opera, known as zarzuela, which had two separate flowerings: one from the mid-17th century through the mid-18th century, and another beginning around 1850. During the late 18th century up until the mid-19th century, Italian opera was immensely popular in Spain, supplanting the native form.

In Russian Eastern Europe, several national operas began to emerge. Ukrainian opera was developed by Semen Hulak-Artemovsky (1813–1873) whose most famous work Zaporozhets za Dunayem (A Cossack Beyond the Danube) is regularly performed around the world. Other Ukrainian opera composers include Mykola Lysenko (Taras Bulba and Natalka Poltavka), Heorhiy Maiboroda, and Yuliy Meitus. At the turn of the century, a distinct national opera movement also began to emerge in Georgia under the leadership Zacharia Paliashvili, who fused local folk songs and stories with 19th-century Romantic classical themes.

The key figure of Hungarian national opera in the 19th century was Ferenc Erkel, whose works mostly dealt with historical themes. Among his most often performed operas are Hunyadi László and Bánk bán. The most famous modern Hungarian opera is Béla Bartók’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle.

Stanisław Moniuszko’s opera Straszny Dwór (in English The Haunted Manor) (1861–64) represents a nineteenth-century peak of Polish national opera.[29] In the 20th century, other operas created by Polish composers included King Roger by Karol Szymanowski and Ubu Rex by Krzysztof Penderecki.

The first known opera from Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) was Arshak II, which was an Armenian opera composed by an ethnic Armenian composer Tigran Chukhajian in 1868 and partially performed in 1873. It was fully staged in 1945 in Armenia.

The first years of the Soviet Union saw the emergence of new national operas, such as the Koroğlu (1937) by the Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov. The first Kyrgyz opera, Ai-Churek, premiered in Moscow at the Bolshoi Theatre on 26 May 1939, during Kyrgyz Art Decade. It was composed by Vladimir Vlasov, Abdylas Maldybaev and Vladimir Fere. The libretto was written by Joomart Bokonbaev, Jusup Turusbekov, and Kybanychbek Malikov. The opera is based on the Kyrgyz heroic epic Manas.[30][31]

In Iran, opera gained more attention after the introduction of Western classical music in the late 19th century. However, it took until mid 20th century for Iranian composers to start experiencing with the field, especially as the construction of the Roudaki Hall in 1967, made possible staging of a large variety of works for stage. Perhaps, the most famous Iranian opera is Rostam and Sohrab by Loris Tjeknavorian premiered not until the early 2000s.

Chinese contemporary classical opera, a Chinese language form of Western style opera that is distinct from traditional Chinese opera, has had operas dating back to The White Haired Girl in 1945.[32][33][34]

In Latin America, opera started as a result of European colonisation. The first opera ever written in the Americas was La púrpura de la rosa, by Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco, although Partenope, by the Mexican Manuel de Zumaya, was the first opera written from a composer born in Latin America (music now lost). The first Brazilian opera for a libretto in Portuguese was A Noite de São João, by Elias Álvares Lobo. However, Antônio Carlos Gomes is generally regarded as the most outstanding Brazilian composer, having a relative success in Italy with its Brazilian-themed operas with Italian librettos, such as Il Guarany. Opera in Argentina developed in the 20th century after the inauguration of Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires—with the opera Aurora, by Ettore Panizza, being heavily influenced by the Italian tradition, due to immigration. Other important composers from Argentina include Felipe Boero and Alberto Ginastera.

Contemporary, recent, and modernist trends[edit]

Modernism[edit]

Perhaps the most obvious stylistic manifestation of modernism in opera is the development of atonality. The move away from traditional tonality in opera had begun with Richard Wagner, and in particular the Tristan chord. Composers such as Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy, Giacomo Puccini,[35] Paul Hindemith, Benjamin Britten and Hans Pfitzner pushed Wagnerian harmony further with a more extreme use of chromaticism and greater use of dissonance. Another aspect of modernist opera is the shift away from long, suspended melodies, to short quick mottos, as first illustrated by Giuseppe Verdi in his Falstaff. Composers such as Strauss, Britten, Shostakovich and Stravinsky adopted and expanded upon this style.

Operatic modernism truly began in the operas of two Viennese composers, Arnold Schoenberg and his student Alban Berg, both composers and advocates of atonality and its later development (as worked out by Schoenberg), dodecaphony. Schoenberg’s early musico-dramatic works, Erwartung (1909, premiered in 1924) and Die glückliche Hand display heavy use of chromatic harmony and dissonance in general. Schoenberg also occasionally used Sprechstimme.

The two operas of Schoenberg’s pupil Alban Berg, Wozzeck (1925) and Lulu (incomplete at his death in 1935) share many of the same characteristics as described above, though Berg combined his highly personal interpretation of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique with melodic passages of a more traditionally tonal nature (quite Mahlerian in character) which perhaps partially explains why his operas have remained in standard repertory, despite their controversial music and plots. Schoenberg’s theories have influenced (either directly or indirectly) significant numbers of opera composers ever since, even if they themselves did not compose using his techniques.

Composers thus influenced include the Englishman Benjamin Britten, the German Hans Werner Henze, and the Russian Dmitri Shostakovich. (Philip Glass also makes use of atonality, though his style is generally described as minimalist, usually thought of as another 20th-century development.)[36]

However, operatic modernism’s use of atonality also sparked a backlash in the form of neoclassicism. An early leader of this movement was Ferruccio Busoni, who in 1913 wrote the libretto for his neoclassical number opera Arlecchino (first performed in 1917).[37] Also among the vanguard was the Russian Igor Stravinsky. After composing music for the Diaghilev-produced ballets Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913), Stravinsky turned to neoclassicism, a development culminating in his opera-oratorio Oedipus Rex (1927). Stravinsky had already turned away from the modernist trends of his early ballets to produce small-scale works that do not fully qualify as opera, yet certainly contain many operatic elements, including Renard (1916: «a burlesque in song and dance») and The Soldier’s Tale (1918: «to be read, played, and danced»; in both cases the descriptions and instructions are those of the composer). In the latter, the actors declaim portions of speech to a specified rhythm over instrumental accompaniment, peculiarly similar to the older German genre of Melodrama. Well after his Rimsky-Korsakov-inspired works The Nightingale (1914), and Mavra (1922), Stravinsky continued to ignore serialist technique and eventually wrote a full-fledged 18th-century-style diatonic number opera The Rake’s Progress (1951). His resistance to serialism (an attitude he reversed following Schoenberg’s death) proved to be an inspiration for many[who?] other composers.[38]

Other trends[edit]

A common trend throughout the 20th century, in both opera and general orchestral repertoire, is the use of smaller orchestras as a cost-cutting measure; the grand Romantic-era orchestras with huge string sections, multiple harps, extra horns, and exotic percussion instruments were no longer feasible. As government and private patronage of the arts decreased throughout the 20th century, new works were often commissioned and performed with smaller budgets, very often resulting in chamber-sized works, and short, one-act operas. Many of Benjamin Britten’s operas are scored for as few as 13 instrumentalists; Mark Adamo’s two-act realization of Little Women is scored for 18 instrumentalists.

Another feature of late 20th-century opera is the emergence of contemporary historical operas, in contrast to the tradition of basing operas on more distant history, the re-telling of contemporary fictional stories or plays, or on myth or legend. The Death of Klinghoffer, Nixon in China, and Doctor Atomic by John Adams, Dead Man Walking by Jake Heggie, and Anna Nicole by Mark-Anthony Turnage exemplify the dramatisation onstage of events in recent living memory, where characters portrayed in the opera were alive at the time of the premiere performance.

The Metropolitan Opera in the US (often known as the Met) reported in 2011 that the average age of its audience was 60.[39] Many opera companies attempted to attract a younger audience to halt the larger trend of greying audiences for classical music since the last decades of the 20th century.[40] Efforts resulted in lowering the average age of the Met’s audience to 58 in 2018, the average age at Berlin State Opera was reported as 54, and Paris Opera reported an average age of 48.[41] New York Times critic Anthony Tommasini has suggested that «companies inordinately beholden to standard repertory» are not reaching younger, more curious audiences.[42]

Smaller companies in the US have a more fragile existence, and they usually depend on a «patchwork quilt» of support from state and local governments, local businesses, and fundraisers. Nevertheless, some smaller companies have found ways of drawing new audiences. In addition to radio and television broadcasts of opera performances, which have had some success in gaining new audiences, broadcasts of live performances to movie theatres have shown the potential to reach new audiences.[43]

From musicals back towards opera[edit]

By the late 1930s, some musicals began to be written with a more operatic structure. These works include complex polyphonic ensembles and reflect musical developments of their times. Porgy and Bess (1935), influenced by jazz styles, and Candide (1956), with its sweeping, lyrical passages and farcical parodies of opera, both opened on Broadway but became accepted as part of the opera repertory. Popular musicals such as Show Boat, West Side Story, Brigadoon, Sweeney Todd, Passion, Evita, The Light in the Piazza, The Phantom of the Opera and others tell dramatic stories through complex music and in the 2010s they are sometimes seen in opera houses.[44] The Most Happy Fella (1952) is quasi-operatic and has been revived by the New York City Opera. Other rock-influenced musicals, such as Tommy (1969) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1971), Les Misérables (1980), Rent (1996), Spring Awakening (2006), and Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 (2012) employ various operatic conventions, such as through composition, recitative instead of dialogue, and leitmotifs.

Acoustic enhancement in opera[edit]

A subtle type of sound electronic reinforcement called acoustic enhancement is used in some modern concert halls and theatres where operas are performed. Although none of the major opera houses «…use traditional, Broadway-style sound reinforcement, in which most if not all singers are equipped with radio microphones mixed to a series of unsightly loudspeakers scattered throughout the theatre», many use a sound reinforcement system for acoustic enhancement and for subtle boosting of offstage voices, child singers, onstage dialogue, and sound effects (e.g., church bells in Tosca or thunder effects in Wagnerian operas).[45]

Operatic voices[edit]

Operatic vocal technique evolved, in a time before electronic amplification, to allow singers to produce enough volume to be heard over an orchestra, without the instrumentalists having to substantially compromise their volume.

Vocal classifications[edit]

Singers and the roles they play are classified by voice type, based on the tessitura, agility, power and timbre of their voices. Male singers can be classified by vocal range as bass, bass-baritone, baritone, baritenor, tenor and countertenor, and female singers as contralto, mezzo-soprano and soprano. (Men sometimes sing in the «female» vocal ranges, in which case they are termed sopranist or countertenor. The countertenor is commonly encountered in opera, sometimes singing parts written for castrati—men neutered at a young age specifically to give them a higher singing range.) Singers are then further classified by size—for instance, a soprano can be described as a lyric soprano, coloratura, soubrette, spinto, or dramatic soprano. These terms, although not fully describing a singing voice, associate the singer’s voice with the roles most suitable to the singer’s vocal characteristics.

Yet another sub-classification can be made according to acting skills or requirements, for example the basso buffo who often must be a specialist in patter as well as a comic actor. This is carried out in detail in the Fach system of German speaking countries, where historically opera and spoken drama were often put on by the same repertory company.

A particular singer’s voice may change drastically over his or her lifetime, rarely reaching vocal maturity until the third decade, and sometimes not until middle age. Two French voice types, premiere dugazon and deuxieme dugazon, were named after successive stages in the career of Louise-Rosalie Lefebvre (Mme. Dugazon). Other terms originating in the star casting system of the Parisian theatres are baryton-martin and soprano falcon.

Historical use of voice parts[edit]

- The following is only intended as a brief overview. For the main articles, see soprano, mezzo-soprano, contralto, tenor, baritone, bass, countertenor and castrato.

The soprano voice has typically been used as the voice of choice for the female protagonist of the opera since the latter half of the 18th century. Earlier, it was common for that part to be sung by any female voice, or even a castrato. The current emphasis on a wide vocal range was primarily an invention of the Classical period. Before that, the vocal virtuosity, not range, was the priority, with soprano parts rarely extending above a high A (Handel, for example, only wrote one role extending to a high C), though the castrato Farinelli was alleged to possess a top D (his lower range was also extraordinary, extending to tenor C). The mezzo-soprano, a term of comparatively recent origin, also has a large repertoire, ranging from the female lead in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas to such heavyweight roles as Brangäne in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (these are both roles sometimes sung by sopranos; there is quite a lot of movement between these two voice-types). For the true contralto, the range of parts is more limited, which has given rise to the insider joke that contraltos only sing «witches, bitches, and britches» roles. In recent years many of the «trouser roles» from the Baroque era, originally written for women, and those originally sung by castrati, have been reassigned to countertenors.

The tenor voice, from the Classical era onwards, has traditionally been assigned the role of male protagonist. Many of the most challenging tenor roles in the repertory were written during the bel canto era, such as Donizetti’s sequence of 9 Cs above middle C during La fille du régiment. With Wagner came an emphasis on vocal heft for his protagonist roles, with this vocal category described as Heldentenor; this heroic voice had its more Italianate counterpart in such roles as Calaf in Puccini’s Turandot. Basses have a long history in opera, having been used in opera seria in supporting roles, and sometimes for comic relief (as well as providing a contrast to the preponderance of high voices in this genre). The bass repertoire is wide and varied, stretching from the comedy of Leporello in Don Giovanni to the nobility of Wotan in Wagner’s Ring Cycle, to the conflicted King Phillip of Verdi’s Don Carlos. In between the bass and the tenor is the baritone, which also varies in weight from say, Guglielmo in Mozart’s Così fan tutte to Posa in Verdi’s Don Carlos; the actual designation «baritone» was not standard until the mid-19th century.

Famous singers[edit]

Early performances of opera were too infrequent for singers to make a living exclusively from the style, but with the birth of commercial opera in the mid-17th century, professional performers began to emerge. The role of the male hero was usually entrusted to a castrato, and by the 18th century, when Italian opera was performed throughout Europe, leading castrati who possessed extraordinary vocal virtuosity, such as Senesino and Farinelli, became international stars. The career of the first major female star (or prima donna), Anna Renzi, dates to the mid-17th century. In the 18th century, a number of Italian sopranos gained international renown and often engaged in fierce rivalry, as was the case with Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni, who started a fistfight with one another during a performance of a Handel opera. The French disliked castrati, preferring their male heroes to be sung by an haute-contre (a high tenor), of which Joseph Legros (1739–1793) was a leading example.[46]

Though opera patronage has decreased in the last century in favor of other arts and media (such as musicals, cinema, radio, television and recordings), mass media and the advent of recording have supported the popularity of many famous singers including Maria Callas, Enrico Caruso, Amelita Galli-Curci, Kirsten Flagstad, Mario Del Monaco, Renata Tebaldi, Risë Stevens, Alfredo Kraus, Franco Corelli, Montserrat Caballé, Joan Sutherland, Birgit Nilsson, Nellie Melba, Rosa Ponselle, Beniamino Gigli, Jussi Björling, Feodor Chaliapin, Cecilia Bartoli, Renée Fleming, Marilyn Horne, Bryn Terfel, Dmitri Hvorostovsky and The Three Tenors (Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, José Carreras).

Changing role of the orchestra[edit]

Before the 1700s, Italian operas used a small string orchestra, but it rarely played to accompany the singers. Opera solos during this period were accompanied by the basso continuo group, which consisted of the harpsichord, «plucked instruments» such as lute and a bass instrument.[47] The string orchestra typically only played when the singer was not singing, such as during a singer’s «…entrances and exits, between vocal numbers, [or] for [accompanying] dancing». Another role for the orchestra during this period was playing an orchestral ritornello to mark the end of a singer’s solo.[47] During the early 1700s, some composers began to use the string orchestra to mark certain aria or recitatives «…as special»; by 1720, most arias were accompanied by an orchestra. Opera composers such as Domenico Sarro, Leonardo Vinci, Giambattista Pergolesi, Leonardo Leo, and Johann Adolf Hasse added new instruments to the opera orchestra and gave the instruments new roles. They added wind instruments to the strings and used orchestral instruments to play instrumental solos, as a way to mark certain arias as special.[47]

German opera orchestra from the early 1950s

The orchestra has also provided an instrumental overture before the singers come onstage since the 1600s. Peri’s Euridice opens with a brief instrumental ritornello, and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) opens with a toccata, in this case a fanfare for muted trumpets. The French overture as found in Jean-Baptiste Lully’s operas[48] consist of a slow introduction in a marked «dotted rhythm», followed by a lively movement in fugato style. The overture was frequently followed by a series of dance tunes before the curtain rose. This overture style was also used in English opera, most notably in Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Handel also uses the French overture form in some of his Italian operas such as Giulio Cesare.[49]

In Italy, a distinct form called «overture» arose in the 1680s, and became established particularly through the operas of Alessandro Scarlatti, and spread throughout Europe, supplanting the French form as the standard operatic overture by the mid-18th century.[50] It uses three generally homophonic movements: fast–slow–fast. The opening movement was normally in duple metre and in a major key; the slow movement in earlier examples was short, and could be in a contrasting key; the concluding movement was dance-like, most often with rhythms of the gigue or minuet, and returned to the key of the opening section. As the form evolved, the first movement may incorporate fanfare-like elements and took on the pattern of so-called «sonatina form» (sonata form without a development section), and the slow section became more extended and lyrical.[50]

In Italian opera after about 1800, the «overture» became known as the sinfonia.[51] Fisher also notes the term Sinfonia avanti l’opera (literally, the «symphony before the opera») was «an early term for a sinfonia used to begin an opera, that is, as an overture as opposed to one serving to begin a later section of the work».[51] In 19th-century opera, in some operas, the overture, Vorspiel, Einleitung, Introduction, or whatever else it may be called, was the portion of the music which takes place before the curtain rises; a specific, rigid form was no longer required for the overture.

The role of the orchestra in accompanying the singers changed over the 19th century, as the Classical style transitioned to the Romantic era. In general, orchestras got bigger, new instruments were added, such as additional percussion instruments (e.g., bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, etc.). The orchestration of orchestra parts also developed over the 19th century. In Wagnerian operas, the forefronting of the orchestra went beyond the overture. In Wagnerian operas such as the Ring Cycle, the orchestra often played the recurrent musical themes or leitmotifs, a role which gave a prominence to the orchestra which «…elevated its status to that of a prima donna».[52] Wagner’s operas were scored with unprecedented scope and complexity, adding more brass instruments and huge ensemble sizes: indeed, his score to Das Rheingold calls for six harps. In Wagner and the work of subsequent composers, such as Benjamin Britten, the orchestra «often communicates facts about the story that exceed the levels of awareness of the characters therein.» As a result, critics began to regard the orchestra as performing a role analogous to that of a literary narrator.»[53]

As the role of the orchestra and other instrumental ensembles changed over the history of opera, so did the role of leading the musicians. In the Baroque era, the musicians were usually directed by the harpsichord player, although the French composer Lully is known to have conducted with a long staff. In the 1800s, during the Classical period, the first violinist, also known as the concertmaster, would lead the orchestra while sitting. Over time, some directors began to stand up and use hand and arm gestures to lead the performers. Eventually this role of music director became termed the conductor, and a podium was used to make it easier for all the musicians to see him or her. By the time Wagnerian operas were introduced, the complexity of the works and the huge orchestras used to play them gave the conductor an increasingly important role. Modern opera conductors have a challenging role: they have to direct both the orchestra in the orchestra pit and the singers on stage.

Language and translation issues[edit]

Since the days of Handel and Mozart, many composers have favored Italian as the language for the libretto of their operas. From the Bel Canto era to Verdi, composers would sometimes supervise versions of their operas in both Italian and French. Because of this, operas such as Lucia di Lammermoor or Don Carlos are today deemed canonical in both their French and Italian versions.[54]

Until the mid-1950s, it was acceptable to produce operas in translations even if these had not been authorized by the composer or the original librettists. For example, opera houses in Italy routinely staged Wagner in Italian.[55] After World War II, opera scholarship improved, artists refocused on the original versions, and translations fell out of favor. Knowledge of European languages, especially Italian, French, and German, is today an important part of the training for professional singers. «The biggest chunk of operatic training is in linguistics and musicianship», explains mezzo-soprano Dolora Zajick. «[I have to understand] not only what I’m singing, but what everyone else is singing. I sing Italian, Czech, Russian, French, German, English.»[56]

In the 1980s, supertitles (sometimes called surtitles) began to appear. Although supertitles were first almost universally condemned as a distraction,[57] today many opera houses provide either supertitles, generally projected above the theatre’s proscenium arch, or individual seat screens where spectators can choose from more than one language. TV broadcasts typically include subtitles even if intended for an audience who knows well the language (for example, a RAI broadcast of an Italian opera). These subtitles target not only the hard of hearing but the audience generally, since a sung discourse is much harder to understand than a spoken one—even in the ears of native speakers. Subtitles in one or more languages have become standard in opera broadcasts, simulcasts, and DVD editions.

Today, operas are only rarely performed in translation. Exceptions include the English National Opera, the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, Opera Theater of Pittsburgh, and Opera South East,[58] which favor English translations.[59] Another exception are opera productions intended for a young audience, such as Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel[60] and some productions of Mozart’s The Magic Flute.[61]

Funding[edit]

Outside the US, and especially in Europe, most opera houses receive public subsidies from taxpayers.[62] In Milan, Italy, 60% of La Scala’s annual budget of €115 million is from ticket sales and private donations, with the remaining 40% coming from public funds.[63] In 2005, La Scala received 25% of Italy’s total state subsidy of €464 million for the performing arts.[64] In the UK, Arts Council England provides funds to Opera North, the Royal Opera House, Welsh National Opera, and English National Opera. Between 2012 and 2015, these four opera companies along with the English National Ballet, Birmingham Royal Ballet and Northern Ballet accounted for 22% of the funds in the Arts Council’s national portfolio. During that period, the Council undertook an analysis of its funding for large-scale opera and ballet companies, setting recommendations and targets for the companies to meet prior to the 2015–2018 funding decisions.[65] In February 2015, concerns over English National Opera’s business plan led to the Arts Council placing it «under special funding arrangements» in what The Independent termed «the unprecedented step» of threatening to withdraw public funding if the council’s concerns were not met by 2017.[66] European public funding to opera has led to a disparity between the number of year-round opera houses in Europe and the United States. For example, «Germany has about 80 year-round opera houses [as of 2004], while the U.S., with more than three times the population, does not have any. Even the Met only has a seven-month season.»[67]

Television, cinema and the Internet[edit]

A milestone for opera broadcasting in the U.S. was achieved on 24 December 1951, with the live broadcast of Amahl and the Night Visitors, an opera in one act by Gian Carlo Menotti. It was the first opera specifically composed for television in America.[68] Another milestone occurred in Italy in 1992 when Tosca was broadcast live from its original Roman settings and times of the day: the first act came from the 16th-century Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle at noon on Saturday; the 16th-century Palazzo Farnese was the setting for the second at 8:15 pm; and on Sunday at 6 am, the third act was broadcast from Castel Sant’Angelo. The production was transmitted via satellite to 105 countries.[69]

Major opera companies have begun presenting their performances in local cinemas throughout the United States and many other countries. The Metropolitan Opera began a series of live high-definition video transmissions to cinemas around the world in 2006.[70] In 2007, Met performances were shown in over 424 theaters in 350 U.S. cities. La bohème went out to 671 screens worldwide. San Francisco Opera began prerecorded video transmissions in March 2008. As of June 2008, approximately 125 theaters in 117 U.S. cities carry the showings. The HD video opera transmissions are presented via the same HD digital cinema projectors used for major Hollywood films.[71] European opera houses and festivals including the Royal Opera in London, La Scala in Milan, the Salzburg Festival, La Fenice in Venice, and the Maggio Musicale in Florence have also transmitted their productions to theaters in cities around the world since 2006, including 90 cities in the U.S.[72][73]

The emergence of the Internet has also affected the way in which audiences consume opera. In 2009 the British Glyndebourne Festival Opera offered for the first time an online digital video download of its complete 2007 production of Tristan und Isolde. In the 2013 season, the festival streamed all six of its productions online.[74][75] In July 2012, the first online community opera was premiered at the Savonlinna Opera Festival. Titled Free Will, it was created by members of the Internet group Opera By You. Its 400 members from 43 countries wrote the libretto, composed the music, and designed the sets and costumes using the Wreckamovie web platform. Savonlinna Opera Festival provided professional soloists, an 80-member choir, a symphony orchestra, and the stage machinery. It was performed live at the festival and streamed live on the internet.[76]

See also[edit]

- Lists of operas, including a general list as well as by theme, by country, by medium, and by venue

- List of fictional literature featuring opera

- Opera management

- Radio opera

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Richard Wagner and Arrigo Boito are notable creators who combined both roles.

- ^ Some definitions of opera: «dramatic performance or composition of which music is an essential part, branch of art concerned with this» (Concise Oxford English Dictionary); «any dramatic work that can be sung (or at times declaimed or spoken) in a place for performance, set to original music for singers (usually in costume) and instrumentalists» (Amanda Holden, Viking Opera Guide); «musical work for the stage with singing characters, originated in early years of 17th century» (Pears’ Cyclopaedia, 1983 ed.).

- ^ Comparable art forms from various other parts of the world, many of them ancient in origin, are also sometimes called «opera» by analogy, usually prefaced with an adjective indicating the region (for example, Chinese opera). These independent traditions are not derivative of Western opera but are rather distinct forms of musical theatre. Opera is also not the only type of Western musical theatre: in the ancient world, Greek drama featured singing and instrumental accompaniment; and in modern times, other forms such as the musical have appeared.

- ^ a b Apel 1969, p. 718

- ^ General information in this section comes from the relevant articles in The Oxford Companion to Music, by P. Scholes (10th ed., 1968).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed., s.v. «opera».

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapter 1; articles on Peri and Monteverdi in The Viking Opera Guide.

- ^ Karin Pendle, Women and Music, 2001, p. 65: «From 1587–1600 a Jewish singer cited only as Madama Europa was in the pay of the Duke of Mantua,»

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 1–3.

- ^ Larousse, Éditions. «Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne – Melchior baron de Grimm». www.larousse.fr.

- ^ Thomas, Downing A (15 June 1995). Music and the Origins of Language: Theories from the French Enlightenment. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-521-47307-1.

- ^ Heyer, John Hajdu (7 December 2000). Lully Studies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62183-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lippman, Edward A. (26 November 1992). A History of Western Musical Aesthetics. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7951-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ «King’s College London – Seminar 1». www.kcl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Man and Music: the Classical Era, ed. Neal Zaslaw (Macmillan, 1989); entries on Gluck and Mozart in The Viking Opera Guide.

- ^ «Strauss and Wagner – Various articles – Richard Strauss». www.richardstrauss.at.

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 5, 8 and 9. Viking Opera Guide entry on Verdi.

- ^ Man and Music: the Classical Era ed. Neal Zaslaw (Macmillan, 1989), pp. 242–247, 258–260; Oxford Illustrated History of Opera pp. 58–63, 98–103. Articles on Hasse, Graun and Hiller in Viking Opera Guide.

- ^ Francien Markx, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Cosmopolitanism, and the Struggle for German Opera, p. 32, BRILL, 2015, ISBN 9004309578

- ^ Thomas Bauman, «New directions: the Seyler Company» (pp. 91–131), in North German Opera in the Age of Goethe, Cambridge University Press, 1985

- ^ General outline for this section from The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 1–3, 6, 8 and 9, and The Oxford Companion to Music; more specific references from the individual composer entries in The Viking Opera Guide.

- ^ Kenrick, John. A History of The Musical: European Operetta 1850–1880. Musicals101.com

- ^ Grout, Donald Jay; Williams, Hermine Weigel (2003). A Short History of Opera. Columbia University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-231-11958-0. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ General outline for this section from The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 1–4, 8 and 9; and The Oxford Companion to Music (10th ed., 1968); more specific references from the individual composer entries in The Viking Opera Guide.

- ^ a b c From Webrarian.com’s Ivanhoe site.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph‘s review of Yeomen stated, «The accompaniments… are delightful to hear, and especially does the treatment of the woodwind compel admiring attention. Schubert himself could hardly have handled those instruments more deftly. …we have a genuine English opera, forerunner of many others, let us hope, and possibly significant of an advance towards a national lyric stage.» (quoted at p. 312 in Allen, Reginald (1975). The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan. London: Chappell & Co. Ltd.).

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 1, 3 and 9. The Viking Opera Guide articles on Blow, Purcell and Britten.

- ^ Taruskin, Richard: «Russia» in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992); Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapters 7–9.

- ^ See the chapter on «Russian, Czech, Polish and Hungarian Opera to 1900» by John Tyrrell in The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (1994).

- ^ Abazov, Rafis (2007). Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics, pp. 144–145. Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-33656-3

- ^ Igmen, Ali F. (2012). Speaking Soviet with an Accent, p. 163. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-7809-1

- ^ Rubin, Don; Chua, Soo Pong; Chaturvedi, Ravi; Majundar, Ramendu; Tanokura, Minoru, eds. (2001). «China». World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre – Asia/Pacific. Vol. 5. p. 111.

Western-style opera (also known as High Opera) exists alongside the many Beijing Opera groups. … Operas of note by Chinese composers include A Girl With White Hair written in the 1940s, Red Squad in Hong Hu and Jiang Jie.

- ^ Zicheng Hong, A History of Contemporary Chinese Literature, 2007, p. 227: «Written in the early 1940s, for a long time The White-Haired Girl was considered a model of new western-style opera in China.»

- ^ Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, vol. 2, p. 145, Lily Xiao Hong Lee, A. D. Stefanowska, Sue Wiles (2003) «… of the PRC, Zheng Lücheng was active in his work as a composer; he wrote the music for the Western-style opera Cloud Gazing.»

- ^ Scott, Derek B. (1998). «Orientalism and Musical Style». The Musical Quarterly. 82 (2): 323. doi:10.1093/mq/82.2.309. JSTOR 742411.

- ^ «Minimalist music: where to start». Classic FM.

- ^ Chris Walton, «Neo-classical opera» in Cooke 2005, p. 108

- ^ Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapter 8; The Viking Opera Guide articles on Schoenberg, Berg and Stravinsky; Malcolm MacDonald Schoenberg (Dent,1976); Francis Routh, Stravinsky (Dent, 1975).

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (17 February 2011). «Met Backtracks on Drop in Average Audience Age». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021.

- ^ General reference for this section: Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, Chapter 9.

- ^ Grey, Tobias (19 February 2018). «An Unlikely Youth Revolution at the Paris Opera». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (6 August 2020). «Classical Music Attracts Older Audiences. Good». The New York Times. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ «On Air & On Line». The Metropolitan Opera. 2007. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (17 December 2003). «Sweeney Todd, Royal Opera House, London». The Guardian. London.

- ^ Harada, Kai (1 March 2001). «Opera’s Dirty Little Secret». Live Design. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012.

- ^ The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera (ed. Parker, 1994), Chapter 11

- ^ a b c John Spitzer. (2009). Orchestra and voice in eighteenth-century Italian opera. In: Anthony R. DelDonna and Pierpaolo Polzonetti (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Opera. pp. 112–139. [Online]. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Waterman, George Gow, and James R. Anthony. 2001. «French Overture». The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Burrows, Donald (2012). Handel. Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-973736-9.

- ^ a b Fisher, Stephen C. 2001. «Italian Overture.» The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ a b Fisher, Stephen C. 1998. «Sinfonia». The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, four volumes, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-333-73432-7

- ^ Murray, Christopher John (2004). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era. Taylor & Francis. p. 772.

- ^ Penner, Nina (2020). Storytelling in Opera and Musical Theater. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780253049971.

- ^ de Acha, Rafael. «Don Carlo or Don Carlos? In Italian or in French?» (Seen and Heard International, 24 September 2013)

- ^ Lyndon Terracini (11 April 2011). «Whose language is opera: the audience’s or the composer’s?». The Australian. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ «For Opera Powerhouse Dolora Zajick, ‘Singing Is Connected To The Body'» (Fresh Air, 19 March 2014)

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony. «So That’s What the Fat Lady Sang» (The New York Times, 6 July 2008)

- ^ «Opera South East’s past productions back to 1980… OSE has always sung its operatic productions in English, fully staged and with orchestra (the acclaimed Sussex Concert Orchestra).» (Opera South East website’s history of ProAm past productions)

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony. «Opera in Translation Refuses to Give Up the Ghost» (The New York Times, 25 May 2001)

- ^ Eddins, Stephen. «Humperdinck’s Hansel & Gretel: A Review». AllMusic.com.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony. «A Mini-Magic Flute? Mozart Would Approve» (The New York Times, 4 July 2005)

- ^ «Special report: Hands in their pockets». The Economist. 16 August 2001. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018.

- ^ Owen, Richard (26 May 2010). «Is it curtains for Italy’s opera houses?». The Times. London.

- ^ Willey, David (27 October 2005). «Italy facing opera funding crisis». BBC News.

- ^ Arts Council England (2015). «Arts Council England’s analysis of its investment in large-scale opera and ballet» Archived 23 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Clark, Nick (15 February 2015). «English National Opera’s public funding may be withdrawn». The Independent. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Osborne, William (11 March 2004). «Marketplace of Ideas: But First, The Bill A Personal Commentary on American and European Cultural Funding». www.osborne-conant.org. William Osborne and Abbie Conant. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Obituary: Gian Carlo Menotti, The Daily Telegraph, 2 February 2007. Accessed 11 December 2008

- ^ O’Connor, John J. (1 January 1993). «A Tosca performed on actual location». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Metropolitan Opera high-definition live broadcast page

- ^ «The Bigger Picture». Thebiggerpicture.us. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ Emerging Pictures Archived 30 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Where to See Opera at the Movies», The Wall Street Journal, 21–22 June 2008, sidebar p. W10.

- ^ Classic FM (26 August 2009). «Download Glyndebourne». Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Rhinegold Publishing (28 April 2013). «With new pricing and more streaming the Glyndebourne Festival is making its shows available to an ever wider audience». Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Partii, Heidi (2014). «Supporting Collaboration in Changing Cultural Landscapes», pp. 208–209 in Margaret S Barrett (ed.) Collaborative Creative Thought and Practice in Music. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1-4724-1584-1

Sources

- Apel, Willi, ed. (1969). Harvard Dictionary of Music (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37501-7.

- Cooke, Mervyn (2005). The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78009-8. See also Google Books partial preview.

Further reading[edit]

- The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie (1992), 5,448 pages, is the best, and by far the largest, general reference in the English language. ISBN 0-333-73432-7, 1-56159-228-5

- The Viking Opera Guide, edited by Amanda Holden (1994), 1,328 pages, ISBN 0-670-81292-7

- The Oxford Illustrated History of Opera, ed. Roger Parker (1994)

- The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, by John Warrack and Ewan West (1992), 782 pages, ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Opera, the Rough Guide, by Matthew Boyden et al. (1997), 672 pages, ISBN 1-85828-138-5

- Opera: A Concise History, by Leslie Orrey and Rodney Milnes, World of Art, Thames & Hudson

- Abbate, Carolyn; Parker, Roger (2012). A History of Opera. New York: W W Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05721-8.

- DiGaetani, John Louis: An Invitation to the Opera, Anchor Books, 1986/91. ISBN 0-385-26339-2.

- Dorschel, Andreas, ‘The Paradox of Opera’, The Cambridge Quarterly 30 (2001), no. 4, pp. 283–306. ISSN 0008-199X (print). ISSN 1471-6836 (electronic). Discusses the aesthetics of opera.

- Silke Leopold, «The Idea of National Opera, c. 1800», United and Diversity in European Culture c. 1800, ed. Tim Blanning and Hagen Schulze (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 19–34.