In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority.[1] The term crime does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,[2] though statutory definitions have been provided for certain purposes.[3] The most popular view is that crime is a category created by law; in other words, something is a crime if declared as such by the relevant and applicable law.[2] One proposed definition is that a crime or offence (or criminal offence) is an act harmful not only to some individual but also to a community, society, or the state («a public wrong»). Such acts are forbidden and punishable by law.[1][4]

The notion that acts such as murder, rape, and theft are to be prohibited exists worldwide.[5] What precisely is a criminal offence is defined by the criminal law of each relevant jurisdiction. While many have a catalogue of crimes called the criminal code, in some common law nations no such comprehensive statute exists.

The state (government) has the power to severely restrict one’s liberty for committing a crime. In modern societies, there are procedures to which investigations and trials must adhere. If found guilty, an offender may be sentenced to a form of reparation such as a community sentence, or, depending on the nature of their offence, to undergo imprisonment, life imprisonment or, in some jurisdictions, death.

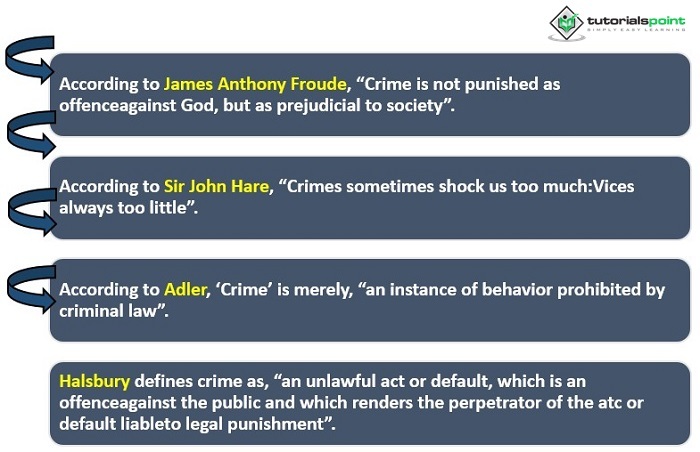

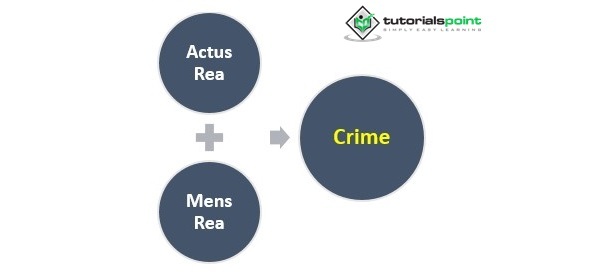

Usually, to be classified as a crime, the «act of doing something criminal» (actus reus) must – with certain exceptions – be accompanied by the «intention to do something criminal» (mens rea).[4]

While every crime violates the law, not every violation of the law counts as a crime. Breaches of private law (torts and breaches of contract) are not automatically punished by the state, but can be enforced through civil procedure.

Overview

When informal relationships prove insufficient to establish and maintain a desired social order, a government or a state may impose more formalized or stricter systems of social control. With institutional and legal machinery at their disposal, agents of the state can compel populations to conform to codes and can opt to punish or attempt to reform those who do not conform.

Authorities employ various mechanisms to regulate (encouraging or discouraging) certain behaviors in general. Governing or administering agencies may for example codify rules into laws, police citizens and visitors to ensure that they comply with those laws, and implement other policies and practices that legislators or administrators have prescribed with the aim of discouraging or preventing crime. In addition, authorities provide remedies and sanctions, and collectively these constitute a criminal justice system. Legal sanctions vary widely in their severity; they may include (for example) incarceration of temporary character aimed at reforming the convict. Some jurisdictions have penal codes written to inflict permanent harsh punishments: legal mutilation, capital punishment, or life without parole.

Usually, a natural person perpetrates a crime, but legal persons may also commit crimes. Historically, several premodern societies believed that non-human animals were capable of committing crimes, and prosecuted and punished them accordingly.[6]

The sociologist Richard Quinney has written about the relationship between society and crime. When Quinney states «crime is a social phenomenon» he envisages both how individuals conceive crime and how populations perceive it, based on societal norms.[7]

Etymology

The word crime is derived from the Latin root cernō, meaning «I decide, I give judgment». Originally the Latin word crīmen meant «charge» or «cry of distress».[8] The Ancient Greek word κρίμα, krima, with which the Latin crimen is cognate, typically referred to an intellectual mistake or an offense against the community, rather than a private or moral wrong.[9]

In 13th century English crime meant «sinfulness», according to the Online Etymology Dictionary. It was probably brought to England as Old French crimne (12th century form of Modern French crime), from Latin crimen (in the genitive case: criminis). In Latin, crimen could have signified any one of the following: «charge, indictment, accusation; crime, fault, offense».

The word may derive from the Latin cernere – «to decide, to sift» (see crisis, mapped on Kairos and Chronos). But Ernest Klein (citing Karl Brugmann) rejects this and suggests *cri-men, which originally would have meant «cry of distress». Thomas G. Tucker suggests a root in «cry» words and refers to English plaint, plaintiff, and so on. The meaning «offense punishable by law» dates from the late 14th century. The Latin word is glossed in Old English by facen, also «deceit, fraud, treachery», [cf. fake]. Crime wave is first attested in 1893 in American English.

Definition

Legalism

In the scope of law, crime is defined by the criminal law of a given jurisdiction, including all actions that are subject to criminal procedure. There is no limit to what can be considered a crime in a legal system, so there may not be a unifying principle used to determine whether an action should be designated as a crime.[10]

Legislatures can pass laws (called mala prohibita) that define crimes against social norms. These laws vary from time to time and from place to place: note variations in gambling laws, for example, and the prohibition or encouragement of duelling in history. Other crimes, called mala in se, count as outlawed in almost all societies, (murder, theft and rape, for example).

English criminal law and the related criminal law of Commonwealth countries can define offences that the courts alone have developed over the years, without any actual legislation: common law offences. The courts used the concept of malum in se to develop various common law offences.[11]

In the military sphere, authorities can prosecute both regular crimes and specific acts (such as mutiny or desertion) under martial-law codes that either supplant or extend civil codes in times of (for example) war. Many constitutions contain provisions to curtail freedoms and criminalize otherwise tolerated behaviors under a state of emergency in case of war, natural disaster or civil unrest. Undesired activities at such times may include assembly in the streets, violation of curfew, or possession of firearms.

Sociology

A normative definition views crime as deviant behavior that violates prevailing norms – cultural standards prescribing how humans ought to behave normally. This approach considers the complex realities surrounding the concept of crime and seeks to understand how changing social, political, psychological, and economic conditions may affect changing definitions of crime and the form of the legal, law-enforcement, and penal responses made by society.

These structural realities remain fluid and often contentious. For example: as cultures change and the political environment shifts, societies may criminalise or decriminalise certain behaviours, which directly affects the statistical crime rates, influence the allocation of resources for the enforcement of laws, and (re-)influence the general public opinion.

Similarly, changes in the collection and/or calculation of data on crime may affect the public perceptions of the extent of any given «crime problem». All such adjustments to crime statistics, allied with the experience of people in their everyday lives, shape attitudes on the extent to which the state should use law or social engineering to enforce or encourage any particular social norm. Behaviour can be controlled and influenced by a society in many ways without having to resort to the criminal justice system.

Indeed, in those cases where no clear consensus exists on a given norm, the drafting of criminal law by the group in power to prohibit the behaviour of another group may seem to some observers an improper limitation of the second group’s freedom, and the ordinary members of society have less respect for the law or laws in general – whether the authorities actually enforce the disputed law or not.

Foundational systems

Natural-law theory

Justifying the state’s use of force to coerce compliance with its laws has proven a consistent theoretical problem. One of the earliest justifications involved the theory of natural law. This posits that the nature of the world or of human beings underlies the standards of morality or constructs them. Thomas Aquinas wrote in the 13th century: «the rule and measure of human acts is the reason, which is the first principle of human acts».[12] He regarded people as by nature rational beings, concluding that it becomes morally appropriate that they should behave in a way that conforms to their rational nature. Thus, to be valid, any law must conform to natural law and coercing people to conform to that law is morally acceptable. In the 1760s, William Blackstone described the thesis:[13]

- «This law of nature, being co-eval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original.»

But John Austin (1790–1859), an early positivist, applied utilitarianism in accepting the calculating nature of human beings and the existence of an objective morality. He denied that the legal validity of a norm depends on whether its content conforms to morality. Thus in Austinian terms, a moral code can objectively determine what people ought to do, the law can embody whatever norms the legislature decrees to achieve social utility, but every individual remains free to choose what to do. Similarly, H.L.A. Hart saw the law as an aspect of sovereignty, with lawmakers able to adopt any law as a means to a moral end.[14]

Thus the necessary and sufficient conditions for the truth of a proposition of law involved internal logic and consistency, and that the state’s agents used state power with responsibility. Ronald Dworkin rejects Hart’s theory and proposes that all individuals should expect the equal respect and concern of those who govern them as a fundamental political right. He offers a theory of compliance overlaid by a theory of deference (the citizen’s duty to obey the law) and a theory of enforcement, which identifies the legitimate goals of enforcement and punishment. Legislation must conform to a theory of legitimacy, which describes the circumstances under which a particular person or group is entitled to make law, and a theory of legislative justice, which describes the law they are entitled or obliged to make.[15]

There are natural-law theorists who have accepted the idea of enforcing the prevailing morality as a primary function of the law.[16] This view entails the problem that it makes any moral criticism of the law impossible: if conformity with natural law forms a necessary condition for legal validity, all valid law must, by definition, count as morally just. Thus, on this line of reasoning, the legal validity of a norm necessarily entails its moral justice.[17]

One can solve this problem by granting some degree of moral relativism and accepting that norms may evolve over time and, therefore, one can criticize the continued enforcement of old laws in the light of the current norms. People may find such law acceptable, but the use of state power to coerce citizens to comply with that law lacks moral justification. More recent conceptions of the theory characterise crime as the violation of individual rights.

Since society considers so many rights as natural (hence the term right) rather than human-made, what constitutes a crime also counts as natural, in contrast to laws (seen as human-made). Adam Smith illustrates this view, saying that a smuggler would be an excellent citizen, «…had not the laws of his country made that a crime which nature never meant to be so.»

Natural-law theory therefore distinguishes between «criminality» (which derives from human nature) and «illegality» (which originates with the interests of those in power). Lawyers sometimes express the two concepts with the phrases malum in se and malum prohibitum respectively. They regard a «crime malum in se» as inherently criminal; whereas a «crime malum prohibitum» (the argument goes) counts as criminal only because the law has decreed it so.

It follows from this view that one can perform an illegal act without committing a crime, while a criminal act could be perfectly legal. Many Enlightenment thinkers (such as Adam Smith and the American Founding Fathers) subscribed to this view to some extent, and it remains influential among so-called classical liberals[citation needed] and libertarians.[citation needed]

Religion

Religious sentiment often becomes a contributory factor of crime. In the 1819 anti-Jewish Hep-Hep riots in Würzburg, rioters attacked Jewish businesses and destroyed property.

Different religious traditions may promote distinct norms of behaviour, and these in turn may clash or harmonise with the perceived interests of a state. Socially accepted or imposed religious morality has influenced secular jurisdictions on issues that may otherwise concern only an individual’s conscience. Activities sometimes criminalized on religious grounds include (for example) alcohol consumption (prohibition), abortion and stem-cell research. In various historical and present-day societies, institutionalized religions have established systems of earthly justice that punish crimes against the divine will and against specific devotional, organizational and other rules under specific codes, such as Roman Catholic canon law and Islamic Shariah Law.

Criminalization

The spiked heads of executed criminals once adorned the gatehouse of the medieval London Bridge.

One can view criminalization as a procedure deployed by society as a preemptive harm-reduction device, using the threat of punishment as a deterrent to anyone proposing to engage in the behavior causing harm. The state becomes involved because governing entities can become convinced that the costs of not criminalizing (through allowing the harms to continue unabated) outweigh the costs of criminalizing it (restricting individual liberty, for example, to minimize harm to others).[citation needed]

States control the process of criminalization because:

- Even if victims recognize their own role as victims, they may not have the resources to investigate and seek legal redress for the injuries suffered: the enforcers formally appointed by the state often have better access to expertise and resources.

- The victims may only want compensation for the injuries suffered, while remaining indifferent to a possible desire for deterrence.[18]

- Fear of retaliation may deter victims or witnesses of crimes from taking any action. Even in policed societies, fear may inhibit from reporting incidents or from co-operating in a trial.

- Victims, on their own, may lack the economies of scale that could allow them to administer a penal system, let alone to collect any fines levied by a court.[19] Garoupa and Klerman (2002) warn that a rent-seeking government has as its primary motivation to maximize revenue and so, if offenders have sufficient wealth, a rent-seeking government will act more aggressively than a social-welfare-maximizing government in enforcing laws against minor crimes (usually with a fixed penalty such as parking and routine traffic violations), but more laxly in enforcing laws against major crimes.

- As a result of the crime, victims may die or become incapacitated.

Labelling theory

The label of «crime» and the accompanying social stigma normally confine their scope to those activities seen as injurious to the general population or to the state, including some that cause serious loss or damage to individuals. Those who apply the labels of «crime» or «criminal» intend to assert the hegemony of a dominant population, or to reflect a consensus of condemnation for the identified behavior and to justify any punishments prescribed by the state (if standard processing tries and convicts an accused person of a crime).

History

Some religious communities regard sin as a crime; some may even highlight the crime of sin very early in legendary or mythological accounts of origins – note the tale of Adam and Eve and the theory of original sin. What one group considers a crime may cause or ignite war or conflict. However, the earliest known civilizations had codes of law, containing both civil and penal rules mixed together, though not always in recorded form.

Ancient Near East

The Sumerians produced the earliest surviving written codes.[20] Urukagina (reigned c. 2380 BC – c. 2360 BC, short chronology) had an early code that has not survived; a later king, Ur-Nammu, left the earliest extant written law system, the Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100 – c. 2050 BC), which prescribed a formal system of penalties for specific cases in 57 articles. The Sumerians later issued other codes, including the «code of Lipit-Ishtar». This code, from the 20th century BCE, contains some fifty articles, and scholars have reconstructed it by comparing several sources.

The Sumerian was deeply conscious of his personal rights and resented any encroachment on them, whether by his King, his superior, or his equal. No wonder that the Sumerians were the first to compile laws and law codes.

— Kramer[21]

Successive legal codes in Babylon, including the code of Hammurabi (c. 1790 BC), reflected Mesopotamian society’s belief that law derived from the will of the gods (see Babylonian law).[22][23]

Many states at this time functioned as theocracies, with codes of conduct largely religious in origin or reference. In the Sanskrit texts of Dharmaśāstra (c. 1250 BC), issues such as legal and religious duties, code of conduct, penalties and remedies, etc. have been discussed and forms one of the elaborate and earliest source of legal code.[24][25]

Sir Henry Maine studied the ancient codes available in his day, and failed to find any criminal law in the «modern» sense of the word.[26] While modern systems distinguish between offences against the «state» or «community», and offences against the «individual», the so-called penal law of ancient communities did not deal with «crimes» (Latin: crimina), but with «wrongs» (Latin: delicta). Thus the Hellenic laws treated all forms of theft, assault, rape, and murder as private wrongs, and left action for enforcement up to the victims or their survivors. The earliest systems seem to have lacked formal courts.[27][28]

Rome and its legacy in Europe

The Romans systematized law and applied their system across the Roman Empire. Again, the initial rules of Roman law regarded assaults as a matter of private compensation. The most significant Roman law concept involved dominion.[29] The pater familias owned all the family and its property (including slaves); the pater enforced matters involving interference with any property. The Commentaries of Gaius (written between 130 and 180 AD) on the Twelve Tables treated furtum (in modern parlance: «theft») as a tort.

Similarly, assault and violent robbery involved trespass as to the pater’s property (so, for example, the rape of a slave could become the subject of compensation to the pater as having trespassed on his «property»), and breach of such laws created a vinculum juris (an obligation of law) that only the payment of monetary compensation (modern «damages») could discharge. Similarly, the consolidated Teutonic laws of the Germanic tribes,[30] included a complex system of monetary compensations for what courts would now consider the complete[citation needed] range of criminal offences against the person, from murder down.

Even though Rome abandoned its Britannic provinces around 400 AD, the Germanic mercenaries – who had largely become instrumental in enforcing Roman rule in Britannia – acquired ownership of land there and continued to use a mixture of Roman and Teutonic Law, with much written down under the early Anglo-Saxon kings.[31] But only when a more centralized English monarchy emerged following the Norman invasion, and when the kings of England attempted to assert power over the land and its peoples, did the modern concept emerge, namely of a crime not only as an offence against the «individual», but also as a wrong against the «state».[32]

This idea came from common law, and the earliest conception of a criminal act involved events of such major significance that the «state» had to usurp the usual functions of the civil tribunals, and direct a special law or privilegium against the perpetrator. All the earliest English criminal trials involved wholly extraordinary and arbitrary courts without any settled law to apply, whereas the civil (delictual) law operated in a highly developed and consistent manner (except where a king wanted to raise money by selling a new form of writ). The development of the idea that the «state» dispenses justice in a court only emerges in parallel with or after the emergence of the concept of sovereignty.

In continental Europe, Roman law persisted, but with a stronger influence from the Christian Church.[33] Coupled with the more diffuse political structure based on smaller feudal units, various legal traditions emerged, remaining more strongly rooted in Roman jurisprudence, but modified to meet the prevailing political climate.

In Scandinavia the effect of Roman law did not become apparent until the 17th century, and the courts grew out of the things – the assemblies of the people. The people decided the cases (usually with largest freeholders dominating). This system later gradually developed into a system with a royal judge nominating a number of the most esteemed men of the parish as his board, fulfilling the function of «the people» of yore.

From the Hellenic system onwards, the policy rationale for requiring the payment of monetary compensation for wrongs committed has involved the avoidance of feuding between clans and families.[34] If compensation could mollify families’ feelings, this would help to keep the peace. On the other hand, the institution of oaths also played down the threat of feudal warfare. Both in archaic Greece and in medieval Scandinavia, an accused person walked free if he could get a sufficient number of male relatives to swear him not guilty. (Compare the United Nations Security Council, in which the veto power of the permanent members ensures that the organization does not become involved in crises where it could not enforce its decisions.)

These means of restraining private feuds did not always work, and sometimes prevented the fulfillment of justice. But in the earliest times the «state» did not always provide an independent policing force. Thus criminal law grew out of what 21st-century lawyers would call torts; and, in real terms, many acts and omissions classified as crimes actually overlap with civil-law concepts.

The development of sociological thought from the 19th century onwards prompted some fresh views on crime and criminality, and fostered the beginnings of criminology as a study of crime in society. Nietzsche noted a link between crime and creativity – in The Birth of Tragedy he asserted:[needs context] «The best and brightest that man can acquire he must obtain by crime». In the 20th century, Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish made a study of criminalization as a coercive method of state control.

Types

The following classes of offences are used, or have been used, as legal terms:

- Offence against the person[35]

- Violent offence[36]

- Sexual offence[36]

- Offence against property[35]

Researchers and commentators have classified crimes into the following categories, in addition to those above:

- Forgery, personation and cheating[37]

- Firearms and offensive weapons[38]

- Offences against the state/offences against the Crown and Government,[39] or political offences[40]

- Harmful or dangerous drugs[41]

- Offences against religion and public worship[42]

- Offences against public justice,[43] or offences against the administration of public justice[44]

- Public order offence[45]

- Commerce, financial markets and insolvency[46]

- Offences against public morals and public policy[47]

- Motor vehicle offences[48]

- Conspiracy, incitement and attempt to commit crime[49]

- Inchoate offence

- Juvenile delinquency

- Victimless crime

- Cruelty to animals

Classification

By penalty

One can categorise crimes depending on the related punishment, with sentencing tariffs prescribed in line with the perceived seriousness of the offence. Thus fines and noncustodial sentences may address the crimes seen as least serious, with lengthy imprisonment or (in some jurisdictions) capital punishment reserved for the most serious.

Common law

Under the common law of England, crimes were classified as either treason, felony or misdemeanour, with treason sometimes being included with the felonies. This system was based on the perceived seriousness of the offence. It is still used in the United States but the distinction between felony and misdemeanour is abolished in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

By mode of trial

The following classes of offence are based on mode of trial:

- Indictable-only offence

- Indictable offence

- Hybrid offence, a.k.a. either-way offence in England and Wales

- Summary offence, a.k.a. infraction in the US

By origin

In common law countries, crimes may be categorised into common law offences and statutory offences. In the US, Australia and Canada (in particular), they are divided into federal crimes and under state crimes.

Reports, studies and organizations

There are several national and International organizations offering studies and statistics about global and local crime activity, such as United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the United States of America Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) safety report or national reports generated by the law-enforcement authorities of EU state member reported to the Europol.

«Offence» in common law jurisdictions

In England and Wales, as well as in Hong Kong, the term «offence» means the same thing as «crime»,[50] They are further split into:

- Summary offences

- Indictable offences

Causes and correlates

Many different causes and correlates of crime have been proposed with varying degree of empirical support. They include socioeconomic, psychological, biological, and behavioral factors. Controversial topics include media violence research and effects of gun politics.

Emotional state (both chronic and current) have a tremendous impact on individual thought processes and, as a result, can be linked to criminal activities. The positive psychology concept of Broaden and Build posits that cognitive functioning expands when an individual is in a good-feeling emotional state and contracts as emotional state declines.[51] In positive emotional states an individual is able to consider more possible solutions to problems, but in lower emotional states fewer solutions can be ascertained. The narrowed thought-action repertoires can result in the only paths perceptible to an individual being ones they would never use if they saw an alternative, but if they can’t conceive of the alternatives that carry less risk they will choose one that they can see. Criminals who commit even the most horrendous of crimes, such as mass murders, did not see another solution.[52]

International

Crimes defined by treaty as crimes against international law include:

- Crimes against peace

- Crimes of apartheid

- Forced disappearance

- Genocide

- Incitement to genocide

- Piracy

- Sexual slavery

- Slavery

- Torture

- Waging a war of aggression

- War crimes

From the point of view of state-centric law, extraordinary procedures (international courts or national courts operating with universal jurisdiction) may prosecute such crimes. Note the role of the International Criminal Court at The Hague in the Netherlands.[citation needed]

Occupational

Two common types of employee crime exist: embezzlement and wage theft.

The complexity and anonymity of computer systems may help criminal employees camouflage their operations. The victims of the most costly scams include banks, brokerage houses, insurance companies, and other large financial institutions.[53]

In the United States, it is estimated[by whom?] that $40 billion to $60 billion are lost annually due to all forms of wage theft.[54] This compares to national annual losses of $340 million due to robbery, $4.1 billion due to burglary, $5.3 billion due to larceny, and $3.8 billion due to auto theft in 2012.[55] In Singapore, as in the United States, wage theft was found to be widespread and severe. In a 2014 survey it was found that as many as one-third of low wage male foreign workers in Singapore, or about 130,000, were affected by wage theft from partial to full denial of pay.[56]

Liability

If a crime is committed, the individual responsible is considered to be liable for the crime. For liability to exist, the individual must be capable of understanding the criminal process and the relevant authority must have legitimate power to establish what constitutes a crime.[57]

See also

- Crime displacement

- Crime science

- Federal Crime

- Law and order (politics)

- National Museum of Crime & Punishment in Washington DC

- Organized crime (also knows as the criminal underworld)

- Category:Age of criminal responsibility

Notes

- ^ a b «Crime». Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009.

- ^ a b Farmer, Lindsay: «Crime, definitions of», in Cane and Conoghan (editors), The New Oxford Companion to Law, Oxford University Press, 2008 (ISBN 978-0-19-929054-3), p. 263 (Google Books Archived 2016-06-04 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ In the United Kingdom, for instance, the definitions provided by section 243(2) of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 and by the Schedule to the Prevention of Crimes Act 1871.

- ^ a b Elizabeth A. Martin (2003). Oxford Dictionary of Law (7 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860756-4.

- ^ Easton, Mark (17 June 2010). «What is crime?». BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Girgen, Jen (2003). «The Historical and Contemporary Prosecution and Punishment of Animals». Animal Law Journal. 9: 97. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Quinney, Richard, «Structural Characteristics, Population Areas, and Crime Rates in the United States,» The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science, 57(1), pp. 45–52

- ^ Ernest Klein, Klein’s Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language Archived 2016-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bakaoukas, Michael. «The conceptualisation of ‘Crime’ in Classical Greek Antiquity: From the ancient Greek ‘crime’ (krima) as an intellectual error to the christian ‘crime’ (crimen) as a moral sin.» ERCES ( European and International research group on crime, Social Philosophy and Ethics). 2005. «Ercesoqr». Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ Lamond, G. (2007-01-01). «What is a Crime?». Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 27 (4): 609–632. doi:10.1093/ojls/gqm018. ISSN 0143-6503.

- ^ Canadian Law Dictionary, John A. Yogis, Q.C., Barrons: 2003

- ^ Thomas, Aquinas, Saint, 1225?-1274. (2002). On law, morality, and politics. Regan, Richard J., Baumgarth, William P. (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. ISBN 0872206637. OCLC 50423002.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Blackstone, William, 1723-1780. (1979). Commentaries on the laws of England. William Blackstone Collection (Library of Congress). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 41. ISBN 0226055361. OCLC 4832359.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hart, H. L. A. (Herbert Lionel Adolphus), 1907-1992. (1994). The concept of law (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198761228. OCLC 31410701.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dworkin, Ronald. (1978). Taking rights seriously : [with a new appendix, a response to critics]. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674867114. OCLC 4313351.

- ^ Finnis, John (2015). Natural Law & Natural Rights. 3.2 Natural law & (purely) positive law as concurrent dimensions of legal reasoning. OUP. ISBN 978-0199599141. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

The moral standards…which Dworkin (in line with natural law theory) treats as capable of being morally objective & true, thus function as a direct source of law and…as already law, except when their fit with the whole set of social-fact sources in the relevant community is so weak that it would be more accurate (according to Dworkin) to say that judges who apply them are applying morality not law.

- ^ Bix, Brian H. (August 2015). «Kelsen, Hart, & legal normativity». 3.3 Law and morality. Revus — OpenEdition Journals. 34 (34). doi:10.4000/revus.3984.

…it was part of the task of a legal theorist to explain the ‘normativity’ or ‘authority’ of law, by which they meant ‘our sense that ‘legal’ norms provide agents with special reasons for acting, reasons they would not have if the norm were not a ‘legal’ one’…this may be a matter calling more for a psychological or sociological explanation, rather than a philosophical one.

- ^ See Polinsky & Shavell (1997) on the fundamental divergence between the private and the social motivation for using the legal system.

- ^ See Polinsky (1980) on the enforcement of fines

- ^ Oppenheim (1964)

- ^ Kramer (1971: 4)

- ^ Driver and Mills (1952–55) and Skaist (1994)

- ^ The Babylonian laws. Driver, G. R. (Godfrey Rolles), 1892–1975; Miles, John C. (John Charles), Sir, 1870–1963. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Pub. April 2007. ISBN 978-1556352294. OCLC 320934300.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^

Anuradha Jaiswal, Criminal Justice Tenets of Manusmriti – A Critique of the Ancient Hindu Code - ^ Olivelle, Patrick. 2004. The Law Code of Manu. New York: Oxford UP.

- ^ Maine, Henry Sumner, 1822–1888 (1861). Ancient law : its connection with the early history of society, and its relation to modern ideas. Tucson. ISBN 0816510067. OCLC 13358229.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gagarin, Michael. (1986). Early Greek law. London: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520909168. OCLC 43477491.

- ^ Garner, Richard, 1953- (1987). Law & society in classical Athens. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0312008562. OCLC 15365822.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Daube, David. (1969). Roman law: linguistic, social and philosophical aspects. Edinburgh: Edinburgh U.P. ISBN 0852240511. OCLC 22054.

- ^ Guterman, Simeon L. (Simeon Leonard), 1907- (1990). The principle of the personality of law in the Germanic kingdoms of western Europe from the fifth to the eleventh century. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 0820407313. OCLC 17731409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attenborough: 1963

- ^ Kern: 1948; Blythe: 1992; and Pennington: 1993

- ^ Vinogradoff (1909); Tierney: 1964, 1979

- ^ The concept of the pater familias acted as a unifying factor in extended kin groups, and the later practice of wergild functioned in this context.[citation needed]

- ^ a b For example, by the Visiting Forces Act 1952

- ^ a b For example, by section 31(1) of the Criminal Justice Act 1991, and by the Criminal Justice Act 2003

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 22

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 24

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 25

- ^ E.g. Card, Cross and Jones: Criminal Law, 12th ed, 1992, chapter 17

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 26

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 27

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 28

- ^ E.g. Card, Cross and Jones: Criminal Law, 12th ed, 1992, chapter 16

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 29

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 30

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 31

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 32

- ^ E.g. Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice, 1999, chapter 33

- ^ Glanville Williams, Learning the Law, Eleventh Edition, Stevens, 1982, p. 3

- ^ Fredrickson, B.L. (2005). Positive Emotions broaden the scope of attention and though-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19: 313–332.

- ^ Baumeister, R.F. (2012). Human Evil: The myth of pure evil and the true causes of violence. In A.P. Association, M. Mikulincer, & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), The social psychology of morality: Exploring the causes of good and evil (pp. 367–380). Washington, DC

- ^ Sara Baase, A Gift of Fire: Social, Legal, and Ethical Issues for Computing and The Internet. Third Ed. «Employee Crime» (2008)

- ^ Michael De Groote, Michael De Groote (24 June 2014). «Wage theft: How employers steal millions from workers every week». Desert News National. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ «Crime in the United States 2012, Table 23». Uniform Crime Reports. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05.

- ^ Choo, Irene (1 September 2014). «Cheap foreign labour to spur economic growth – think deeper and harder». The Online Citizen. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

- ^ Duff, R. (1998-06-01). «Law, language and community: some preconditions of criminal liability». Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. 18 (2): 189–206. doi:10.1093/ojls/18.2.189. ISSN 0143-6503.

References and further reading

- Attenborough, F.L. (ed. and trans.) (1922). The Laws of the Earliest English Kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprint March 2006. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 1-58477-583-1

- Blythe, James M. (1992). Ideal Government and the Mixed Constitution in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03167-3

- Cohen, Stanley (1985). Visions of Social Control: Crime, Punishment, and Classification. Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-0021-2

- Foucault, Michel (1975). Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison, New York: Random House.

- Garoupa, Nuno & Klerman, Daniel. (2002). «Optimal Law Enforcement with a Rent-Seeking Government». American Law and Economics Review Vol. 4, No. 1. pp. 116–140.

- Hart, H.L.A. (1972). Law, Liberty and Morality. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0154-7

- Hitchins, Peter. A Brief History of Crime (2003) 2nd edition was issued as he Abolition of Liberty: The Decline of Order and Justice in England (2004)

- Kalifa, Dominique. Vice, Crime, and Poverty: How the Western Imagination Invented the Underworld (Columbia University Press, 2019)

- Kern, Fritz. (1948). Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages. Reprint edition (1985), Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. (1971). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-45238-7

- Maine, Henry Sumner. (1861). Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas. Reprint edition (1986). Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1006-7

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (and Reiner, Erica as editor). (1964). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Revised edition (September 15, 1977). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-63187-7

- Pennington, Kenneth. (1993). The Prince and the Law, 1200–1600: Sovereignty and Rights in the Western Legal Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07995-7

- Polinsky, A. Mitchell. (1980). «Private versus Public Enforcement of Fines». The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. IX, No. 1, (January), pp. 105–127.

- Polinsky, A. Mitchell & Shavell, Steven. (1997). On the Disutility and Discounting of Imprisonment and the Theory of Deterrence, NBER Working Papers 6259, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Skaist, Aaron Jacob. (1994). The Old Babylonian Loan Contract: Its History and Geography. Ramat Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University Press. ISBN 965-226-161-0

- Théry, Julien. (2011). «Atrocitas/enormitas. Esquisse pour une histoire de la catégorie de ‘crime énorme’ du Moyen Âge à l’époque moderne», Clio@Themis, Revue électronique d’histoire du droit, n. 4 Archived 2015-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Tierney, Brian. (1979). Church Law and Constitutional Thought in the Middle Ages. London: Variorum Reprints. ISBN 0-86078-036-8

- Tierney, Brian (1988) [1964]. The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300: with selected documents (Reprint ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6701-2.

- Vinogradoff, Paul. (1909). Roman Law in Medieval Europe. Reprint edition (2004). Kessinger Publishing Co. ISBN 1-4179-4909-0

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Crime.

Look up crime in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crimes.

Wikivoyage has travel information for crime.

- Crime at Curlie

A crime is generally a deliberate act that results in harm, physical or otherwise, toward one or more people, in a manner prohibited by law. The determination of which acts are to be considered criminal has varied historically, and continues to do so among cultures and nations. When a crime is committed, a process of discovery, trial by judge or jury, conviction, and punishment occurs. Just as what is considered criminal varies between jurisdictions, so does the punishment, but elements of restitution and deterrence are common.

Although extensive studies in criminology and penology have been carried out, and numerous theories of its causes have emerged, no criminal justice system has succeeded in eliminating crime. Understanding and resolving the root of crime involves the depths of human nature and relationships. Some regard religious faith as a preventative, turning ex-convicts to a meaningful life in society. There is evidence that the bonds of family can be a deterrent, embedding the would-be criminal within bonds of caring and obligation that make a life of crime unattractive.

Definition of Crime

Crime can be viewed from either a legal or normative perspective.

A legalistic definition takes as its starting point the common law or the statutory/codified definitions contained in the laws enacted by the government. Thus, a crime is any culpable action or omission prohibited by law and punished by the state. This is an uncomplicated view: a crime is a crime because the law defines it as such.

A normative definition views crime as deviant behavior that violates prevailing norms, i.e. cultural standards specifying how humans ought to behave. This approach considers the complex realities surrounding the concept of crime and seeks to understand how changing social, political, psychological, and economic conditions may affect the current definitions of crime and the forms of legal, law enforcement, and penal responses made by the state.

Deviance and crime are related but not the same. Actions can be criminal and deviant, criminal but not deviant, or deviant but not criminal. For instance, a crime that is not deviant may be speeding or jaywalking. While legally criminal, speeding and jaywalking are not considered socially unacceptable, nor are the perpetrators considered criminals by their peers. An example of a deviant but not criminal act is homosexuality. Homosexuality deviates from mainstream values, but a person is not labeled a criminal just for being homosexual. Crimes that are deviant include murder, rape, assault, and other violent crimes. These realities are fluid and often contentious. For example, as cultures change and the political environment shifts, behavior may be criminalized or decriminalized.

Similarly, crime is distinguished from sin, which generally refers to disregard for religious or moral law, especially norms revealed by God. Sins such as murder and rape are generally also crimes, whereas blasphemy or adultery may not be treated as criminal acts.

In modern conceptions of natural law, crime is characterized as the violation of individual rights. Since rights are considered as natural, rather than manmade, what constitutes a crime is also natural, in contrast to laws, which are manmade. Adam Smith illustrated this view, saying that a smuggler would be an excellent citizen, «had not the laws of his country made that a crime which nature never meant to be so.»

Natural law theory therefore distinguishes between «criminality» which is derived from human nature, and «illegality» which is derived from the interests of those in power. The two concepts are sometimes expressed with the phrases malum in se and malum prohibitum. A crime malum in se is argued to be inherently criminal; whereas a crime malum prohibitum is argued to be criminal only because the law has decreed it so. This view leads to a seeming paradox, that an act can be illegal but not a crime, while a criminal act could be perfectly legal.

The action of crime is settled in a criminal trial. In the trial, a specific law, one set in the legal code of a society, has been broken, and it is necessary for that society to understand who committed the crime, why the crime was committed, and the necessary punishment against the offender to be levied. Civil trials are not necessarily focused on a broken law. Those trials are usually focused on private parties and a personal dispute that arose between them. The solution in civil trials usually aims, through monetary compensation, to provide restitution to the wronged party.

In some societies, crimes have been prosecuted entirely by civil law. In early England, after the Roman Empire collapsed, communities prosecuted all crimes through civil law. There were no prisons and serious criminals were declared «outlaws.» This meant that if any harm befell one who was outside the law, no trial would be conducted. Outlaws fled for fear they would be dead on the street the next morning. This is why many outlaws found sanctuary in Sherwood Forest.

Types of Crime

Antisocial behavior is criminalized and treated as offenses against society, which justifies punishment by the government. A series of distinctions are made depending on the passive subject of the crime (the victim), or on the offended interest(s), in crimes against:

- Personality of the state. For instance, a person may not agree with the laws in their society, so he or she may commit a crime to show their disapproval. For instance, there have been crimes committed by those disapproving of abortion, involving attacks on abortion clinics.

- Rights of the citizen.

- Administration of justice. This type of crime includes abuse of the judicial system and non-compliance with the courts and law enforcement agencies.

- Religious sentiment and faith. For instance, church burnings, graffiti on synagogues, and religiously motivated attacks on the Muslim community post-September 11, 2001 in the United States reflect crimes against religion.

- Public order. Riots and unwarranted demonstrations represent crimes against public order, as they break down established order and create hysteria, panic, or chaos.

- Public economy, industry, and commerce. Any illegal buying and selling of goods and services classifies as this type of crime, for example, bootlegging, smuggling, and the black market.

- Person and honor. In certain societies, there exists the «culture of honor,» in which people may act to defend their honor if they feel it is insulted or violated.

Crimes may also be distinguished based on the related punishment prescribed in line with the perceived seriousness of the offense with fines and noncustodial sentences for the least serious, and in some places, capital punishment for the most serious.

Crimes are also grouped by severity, some common categorical terms being: felony and misdemeanor, indictable offense, and summary offense. For convenience, infractions are also usually included in such lists although, in the U.S., they may not be the subject of the criminal law, but rather of the civil law.

The following are considered crimes in many jurisdictions:

|

|

|

|

|

Theories of Crime

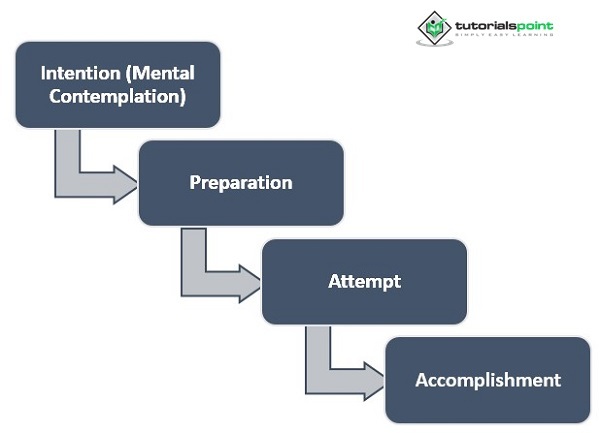

There are many theories discussing why people commit crimes and deviant acts. Criminal theories can be divided into biological theories versus classical theories. Biological theories focus on pathology, sickness, and determinism, basically assuming that a person is born a criminal. Classical theories focus on free will and the idea of a social contract to which people conform. These theories assume that no one is born a criminal, and that they come to commit criminal acts as a result of their experiences.

Psychoanalytical Theories of Crime assume that criminals are different from non-criminals, and that criminal offenders have different personalities from those of non-offenders. Freudian theory suggests that crime is a result of frustration, resulting from stunted growth in one of the four stages of maturation: oral, anal, genital, and phallic. Aggression is then a result of the frustration that developed from lack of goal attainment.

Cognitive Theories of Crime involve the development of people’s ability to make judgments. Psychologists and criminologists have detailed a variety of theories of developmental psychology and moral psychology and its relationship to crime. Jean Piaget suggested that there are two stages in the cognitive development of judgment. The first stage involves the «acceptance of rules as absolute.» For instance, in order for a child to develop judgment, he or she must realize from a young age that the rules his or her parents make are unchanging in nature and apply directly to them. The second step describes the «spirit of law.» This is basically a realization that the law has consequences, that if one acts counter to the law, it will affect them. Lawrence Kohlberg also researched the development of moral judgment, describing six steps, which were then divided into three stages: «pre-conventional,» «conventional,» and «post-conventional.» These stages represent Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. In the «pre-conventional stage,» the first two steps, the goals in life are to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, and the desire to gain reward without punishments or consequences. Kohlberg suggested that most criminals are stuck in this stage. The next stage, the «conventional stage,» involves people following the rules absolutely in order to gain social approval and respect. People feel empathy and guilt in this stage, and according to Kohlberg, most people are in this stage. The final stage, the «post-conventional stage,» involves people judging rules according to their own values along with a sense of there being a universal justice. Most people do not reach this stage.

The Functionalist Theory of Crime involves a macro level theory of crime. Functionalism assumes that: society is a living organism, comprised of social institutions that overlap, and that social institutions work to keep society in order. Emile Durkheim suggested that crime is functional because it has always existed in society, making crime a normal part of society. Crime serves as a guide for acceptable social behavior, and it creates consensus among people in a society on what is deviant. Durkheim also suggested that deviance brings social change, which is a positive and needed aspect in all societies. Too much crime, however, results in weakened social consensus and social order, leading to anomie, a state of normlessness, which no society can survive for long.

The Social Disorganization Theory of Crime is an ecological perspective on crime, dealing with places, not people, as the reason crime happens: where one lives is causal to criminality; the physical and social conditions a person is surrounded by create crime. The assumption of this theory is that people are inherently good, but are changed by their environment. According to this theory, five types of change are most responsible for criminality. They are: urbanization, migration, immigration, industrialization, and technological change. If any one of these aspects occurs rapidly, it breaks down social control and social bonds, creating disorganization.

The Strain Theory of Crime proposes that crime occurs when a person is unable to attain their goals through legitimate means. Robert K. Merton described strain by showing different ways an individual can meet their goals. Conformity is the method by which most people achieve what they want: a person conforms to the ideals and values of mainstream society. Merton said that criminals use «innovation» to achieve their goals, which means that they agree with the goals that mainstream society offers, but seek or require different means to achieve them. He also identified other ways in which individuals achieve their own goals, including «retreatism,» «rebellion,» and «ritualism.» Strain theory was modified by Robert Agnew (2005) when he said that it was too tied to social class and cultural variables and needed to take into account a more universal perspective of crime. Three components of Agnew’s modification of strain theory are: failure to achieve positive goals, loss of some positively valued stimuli, and presentation of negative stimuli. He suggested that these cause strain between a person and the society they live in, resulting in a negative affective state, which may lead to criminal activity.

Crime as a Function of Family and Community

It has long been suggested that a core family is a valuable preventative measure to crime. However, the relationship between criminal activity and a strong family has a number of different dimensions.

«Collective efficacy» in neighborhoods is often thought of as the foundations for preventing violent crime in communities. Collective efficacy holds that there is social cohesion among neighbors, common values of neighborhood residents, an informal social control, and a willingness to regulate crime or deviance amongst neighbors. This collective efficacy requires the presence of strong families, each member committed to each other and their neighbors.

The studies of Mary Pattillo-McCoy (2000) examined collective efficacy, but brought a startling new revelation to light. Her study on Groveland (a middle class typically African American neighborhood in Chicago), concluded that collective efficacy can lead to a unique pattern of violent crime. Groveland had a strong collective efficacy; however, gang violence was also prevalent. The neighborhood gang members participated in violent activity, but since they were involved in the collective efficacy, they kept violent crime out of their home neighborhood. They did not want their families or friends put in harm’s way due to their gang activity. This unique take on collective efficacy shows how strong family and neighborhood bonds can foster, as well as prevent, violent crime.

Travis Hirschi (1969) suggested an idea called «social bond theory.» The underlying idea of this theory is that the less attachment a person has to society, the more likely they are to participate in activities that harm society or go against mainstream social values. Hirschi contended that attachment to friends and family, commitment to family and career, involvement in education and family, and belief in the law and morality will ensure that a person will not undertake criminal activities. If even one of these variables is weakened, the chances one will participate in crime increases. This is an element of «social control theory,» which states that people’s bonds and relationships are what determine their involvement in crime.

Elijah Anderson (2000) identified families as perhaps the most important factor in criminality. Anderson is responsible for the idea of the «code of the street,» which are informal rules governing interpersonal behavior, particularly violence. His studies identified two types of families in socially disorganized neighborhoods: «decent families» and «street families.» Decent families, he said, accept mainstream social values and socialize their children to these values, sometimes using the knowledge of the «code of the street» to survive. Street families have very destructive behaviors and a lack of respect for those around them. They apparently have superficial ties to the community and other family members, only vying for respect of those around them. Anderson argued that street families breed criminals, suggesting that the family one is raised in could possibly identify if a person will become a criminal.

Age, Race, and Gender

The idea of crime being specific to a particular age, race, or gender has been examined thoroughly in criminology. Crime is committed by all types of people, men and women, of any age. There is evidence, however, that these different variables have important effects on crime rates, which criminal theories attempt to explain.

Age

Studies in criminology detail what is popularly known as the «age-crime curve,» named for the curve of the graph comparing age as the independent variable to crime as the dependent variable. The graph shows an increase in crime in teenage years, tapering off and decreasing in the early to mid-twenties, and continuing to decrease as age increases. This «age-crime curve» has been discovered in nearly every society, internationally and historically.

In 2002, according to the Uniform Crime Report in the United States, 58.6 percent of violent crime offenders were under the age of 25, with 14.9 percent being under the age of 18. A disturbing trend in the U.S. from the very end of the twentieth century has been the increasing incidence of homicides and other violent assaults by teenagers and even younger children, occurring in the context of robberies, gang-related incidents, and even random shootings in public places, including their own high schools.

Race

In 2002, according to the Uniform Crime Report in the United States, whites made up 59.7 percent of all violent crime arrestees, blacks comprised 38.0 percent, and other minorities 2.3 percent.

Historically, through phrenology and biology, scientists attempted to prove that certain people were destined to commit crime. However, these theories were proven unfounded. No race or culture has been shown to be biologically predisposed towards committing crimes or deviance.

The Social Disorganization Theory of Crime explains instances of urban crime, dividing the city into different regions, explaining that the transitional zone, which surrounds the business zone, is the most notorious for crime. For example, the transitional zone is known for deteriorated housing, factories, and abandoned buildings. In urban areas, minorities are usually inhabitants of the transitional zone, surrounding them in urban decay. This urban decay results in strain (as described in Agnew’s strain theory) and leads to criminal activity, through their having been disenfranchised from mainstream goals. In other words, society’s failure to maintain urban transitional zones is a major factor in minorities committing crimes.

Elijah Anderson, an African American who has written much on the subject of race and crime, claimed that institutions of social control often engage in «color coding,» such that an African American is assumed guilty until proven innocent (Anderson 2000). Others have noted that social institutions are victims of institutional racism. For instance, in The Rich Get Richer, and the Poor Get Prison, Jeffrey Reiman examined the differences between white middle to upper class teenagers and black lower class teenagers and how they were treated by the police. The difference he discovered for even first time offenders of both white and black teenagers was unsettling. White teenagers typically were treated with respect, their parents are informed immediately, and often jurisdiction and punishment was given to the parents to decide. However, black teenagers were often held over night, their parents informed later or not at all, and first time offenders treated like multiple offenders.

Thus, overall, there appear to be many different aspects of society responsible for the preponderance of minority crime.

Gender

Gender distribution in criminal behavior is very disproportionate. In 2002, according to Uniform Crime Report in the United States, men made up 82.6 percent of violent crime arrestees.

There are different gender theories and criticisms that attempt to explain gender discrepancies, usually referred to as the «gender-ratio problem of crime.» While it is still uncertain why women do not engage in violent crime at nearly the rate that men do, there are many sociological theories that attempt to account for this difference.

The Marxist-Feminist approach suggests that gender oppression is a result of social class oppression, and that feminine deviance and crime occurs because of women’s marginalized economic position within the legitimate world and the world of crime. For instance, prostitution represents those at the top of the hierarchy abusing those at the bottom of the hierarchy through corruption of wage labor. Women do not engage in violent crime because gender and capitalistic oppression disenfranchises them from mainstream criminal activities.

The Liberal-Feminist approach assumes that gender represents one of many competing categories in a society. For example, another competing category could be elderly citizens, or the impoverished, or minority cultures. Those who agree with this approach support initiatives designed to improve women’s standing in the existing social structure, but do not wish to challenge the system as a whole. A liberal-feminist would argue that prostitution is acceptable because it represents a business contract between two people: one person pays for a rendered service. Liberal-feminists suggest that low levels of violent crime among women are a result of their social category, that there is no perceived benefit for females to engage in violent crime.

The Radical-Feminist approach is opposite to the liberal-feminist approach. Radical-feminists argue that gender is the most important form of social oppression. Through this approach, women need to start a social movement to create a new system with equality written into the social structure. To a radical-feminist, prostitution is a form of gender oppression that needs to end. Radical-feminists argue that some women are driven to violent crime because of perceived hopelessness and abandonment by society because of the oppression of a patriarchal society.

Crime and Punishment

Generally, in the criminal justice system, when a crime is committed the perpetrator is discovered, brought to trial in a court, and if convicted, receives punishment as prescribed by the penal system. Penologists, however, have differing views on the role of punishment.

Punishment is as much to protect society as it is to penalize and reform the criminal. Additionally, it is intended as a deterrent to future crimes, by the same perpetrator or by others. However, the efficacy of this is not universally accepted, particularly in the case of capital punishment. A desired punishment is one that is equal to the crime committed. Any more is too severe, any less is too lenient. This serves as justice in equilibrium with the act of crime. Punishment gives the criminal the tools to understand the way they wronged the society around them, granting them the ability to one day possibly come to terms with their crime and rejoin society, if their punishment grants the privilege.

Punishmment as deterrence can take two forms:

- Specific: The intention underlying the penal system is to deter future wrongdoing by the defendant, if convicted. The punishment demonstrates the unfortunate consequences that follow any act that breaks the law.

- General: The punishment imposed on the particular accused is also a warning to other potential wrongdoers. Thus the function of the trial is to gain the maximum publicity for the crime and its punishment, so that others will be deterred from following in the particular accused’s footsteps.

Theoretical justification of punishment

A consistent theoretical problem has been to justify the state’s use of punishment to coerce compliance with its laws. One of the earliest justifications was the theory of natural law. This posits that the standards of morality are derived from or constructed by the nature of the world or of human beings. Thomas Aquinas said: «the rule and measure of human acts is the reason, which is the first principle of human acts» (Aquinas, ST I-II, Q.90, A.I), i.e. since people are by nature rational beings, it is morally appropriate that they should behave in a way that conforms to their rational nature. Thus, to be valid, any law must conform to natural law and coercing people to conform to that law is morally acceptable. William Blackstone (1979) described the thesis:

This law of nature, being co-eval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries, and at all times: no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this; and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their authority, mediately or immediately, from this original (41).

John Austin, an early positivist, developed a theory based on utilitarian principles, which deviates slightly from natural law theory. This theory accepts the calculating nature of human beings and the existence of an objective morality, but, unlike natural law theory, denies that the legal validity of a norm depends on whether its content conforms to morality, i.e. a moral code objectively determines what people ought to do, and the law embodies whatever norms the legislature decrees to achieve social utility. Similarly, Hart (1961) saw the law as an aspect of sovereignty, with lawmakers able to adopt any law as a means to a moral end. Thus, the necessary and sufficient conditions for the truth of a proposition of law were simply that the law was internally logical and consistent, and that state power was being used with responsibility.

Dworkin (2005) rejected Hart’s theory and argued that fundamental among political rights is the right of each individual to the equal respect and concern of those who govern him. He offered a theory of compliance overlaid by a theory of deference (the citizen’s duty to obey the law) and a theory of enforcement, which identified the legitimate goals of enforcement and punishment. According to his thesis, legislation must conform to a theory of legitimacy, which describes the circumstances under which a particular person or group is entitled to make law, and a theory of legislative justice, which describes the law they are entitled or obliged to make and enforce.

History of Criminal Law

The first civilizations had codes of law, containing both civil and penal rules mixed together, though these codes were not always recorded. According to Oppenheim (1964), the first known written codes were produced by the Sumerians, and it was probably their king Ur-Nammu (who ruled over Ur in the twenty-first century B.C.E.) who acted as the first legislator, creating a formal system in 32 articles. The Sumerians later issued other codes including the «code of Lipit-Istar» (last king of the third dynasty of Ur, Isin, twentieth century B.C.E.). This code contained some 50 articles and has been reconstructed by the comparison among several sources. Kramer (1971) adds a further element: «The Sumerian was deeply conscious of his personal rights and resented any encroachment on them, whether by his King, his superior, or his equal. No wonder that the Sumerians were the first to compile laws and law codes» (4).

In Babylon, Driver and Mills (1952–1955) and Skaist (1994) describe the successive legal codes, including the code of Hammurabi (one of the richest of ancient times), which reflected society’s belief that law was derived from the will of the gods. Many of the states at this time were theocratic, and their codes of conduct were religious in origin or reference.

While modern legal systems distinguish between offenses against the «State» or «Community,» and offenses against the «Individual,» what was termed the penal law of ancient communities was not the law of «Crimes» (criminal); it was the law of «Wrongs» (delicta). Thus, the Hellenic laws (Gagarin 1986 and Garner 1987) treated all forms of theft, assault, rape, and murder as private wrongs, and action for enforcement was up to the victim or their survivors (which was a challenge in that although there was law, there were no formalized courts in the earliest system).

It was the Romans who systematized law and exported it to their empire. Again, the initial rules of Roman law were that assaults were a matter of private compensation. The significant Roman law concept was of dominion (Daube 1969). The pater familias was in possession of all the family and its property (including slaves). Hence, interference with any property was enforced by the pater. The Commentaries of Gaius on the Twelve Tables treated furtum (modern theft) as if it was a tort. Similarly, assault and violent robbery were allied with trespass as to the pater’s property (so, for example, the rape of a female slave, would be the subject of compensation to the pater as having trespassed on his «property») and breach of such laws created a vinculum juris (an obligation of law) that could only be discharged by the payment of monetary compensation (modern damages). Similarly, in the consolidated Teutonic Laws of the Germanic tribes (Guterman 1990), there was a complex system of money compensations for what would now be considered the complete range of criminal offenses against the person.

Even though Rome abandoned England sometime around 400 C.E., the Germanic mercenaries who had largely been enforcing the Roman occupation, stayed on and continued to use a mixture of Roman and Teutonic law, with much written down by the early Anglo-Saxon kings (Attenborough 1963). But, it was not until a more unified kingdom emerged following the Norman invasion and the king attempting to assert power over the land and its peoples, that the modern concept emerged, namely that a crime is not only an offense against the «individual,» it is also a wrong against the «state» (Kern 1948, Blythe 1992, and Pennington 1993). This is a common law idea and the earliest conception of a criminal act involved events of such major significance that the «state» had to usurp the usual functions of the civil tribunals and direct a special law or privilegium against the perpetrator. The Magna Carta, issued in 1215, also granted more power to the state, clearing the passage for legal procedures that King John had previously refused to recognize. All the earliest criminal trials were wholly extraordinary and arbitrary without any settled law to apply, whereas the civil law was highly developed and generally consistent in its operation. The development of the idea that it is the «state» dispensing justice in a court only emerged in parallel with or after the emergence of the concept of sovereignty.

In continental Europe, Vinogradoff (1909) reported the persistence of Roman law, but with a stronger influence from the church (Tierney 1964, 1979). Coupled with the more diffuse political structure based on smaller state units, rather different legal traditions emerged, remaining more strongly rooted in Roman jurisprudence, modified to meet the prevailing political climate. In Scandinavia, the effect of Roman law was not felt until the seventeenth century, and the courts grew out of the things (or tings), which were the assemblies of the people. The cases were decided by the people (usually the largest freeholders dominating), which later gradually transformed into a system of a royal judge nominating a number of most esteemed men of the parish as his board, fulfilling the function of «the people» of yore.

Conclusion

Crime has existed in all societies, and that efforts to legislate, enforce, punish, or otherwise correct criminal behavior have not succeeded in eliminating crime. While some have concluded that crime is a necessary evil in human society, and have sought to justify its existence by pointing to its role in social change, an alternative view is that the cause of crime is to be found in the problems of human nature and human relationships that have plagued us since the origins of human history. Correcting these problems would effectively remove the source of crime, and bring about a peaceful world in which all people could realize their potential as individuals, and develop satisfying, harmonious relationships with others.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1988. On Law, Morality and Politics, 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 0872206637

- Agnew, Robert. 2005. Pressured Into Crime: An Overview of General Strain Theory. Roxbury Publishing. ISBN 1933220252

- Anderson, Elijah. 2000. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. W.W. Norton and Company. ISBN 093320782

- Attenborough, F. L., ed. and trans. 1922. The Laws of the Earliest English Kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprint March 2006: The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 9781584775836

- Blackstone, William. 1979 (original 1765–1769). Commentaries on the Law of England, vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226055388

- Blythe, James M. 1992. Ideal Government and the Mixed Constitution in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691031673

- Daube, David. 1969. Roman Law: Linguistic, Social and Philosophical Aspects. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0852240511

- Driver, G. R., and John C. Mills. 1952–1955. The Babylonian Laws, 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198251106

- Dworkin, Ronald. 2005. Taking Rights Seriously. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674867114

- Gagarin, Michael. 1989 (original 1986). Early Greek Law, reprint ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520066022

- Garner, Richard. 1987. Law and Society in Classical Athens. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312008562

- Garoupa, Nuno, and Daniel Klerman. 2002. «Optimal Law Enforcement with a Rent-Seeking Government» in American Law and Economics Review vol. 4, no. 1: pp. 116–140.

- Guterman, Simeon L. 1990. The Principle of the Personality of Law in the Germanic Kingdoms of Western Europe from the Fifth to the Eleventh Century. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 0820407313

- Hart, H. L. A. 1972. Law, Liberty and Morality. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804701547

- Hart, H. L. A. 1997 (original 1961). The Concept of Law, 2nd rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198761236

- Hirischi, Travis. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. University of California Press. ISBN 0765809001

- Kern, Fritz. 1985 (original 1948). Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages, reprint ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1984. The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages. Harpercollins College Division. ISBN 0060647612

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. 1971. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226452387

- Maine, Henry Sumner. 1986 (original 1861). Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas, reprint ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816510067

- Merton, Robert. 1967. On Theoretical Sociology. Free Press. ISBN 0029211506

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. 1977 (original 1964). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, edited by Erica Reiner, revised ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226631877

- Patillo-McCoy, Mary. 2000. Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among the Black Middle Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226649269

- Pennington, Kenneth. 1993. The Prince and the Law, 1200–1600: Sovereignty and Rights in the Western Legal Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Polinsky, A. Mitchell. 1980. «Private versus Public Enforcement of Fines» in Journal of Legal Studies vol. IX, no. 1 (January): pp. 105–127.

- Polinsky, A. Mitchell, and Steven Shavell. 1997. «On the Disutility and Discounting of Imprisonment and the Theory of Deterrence,» NBER Working Papers 6259, National Bureau of Economic Research [1].

- Reiman, Jeffrey. 2005. The Rich Get Richer, and the Poor Get Prison: Ideology, Class, and Criminal Justice. Allyn and Bacon Publishing. ISBN 0205480322

- Skaist, Aaron Jacob. 1994. The Old Babylonian Loan Contract: Its History and Geography. Ramat Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University Press. ISBN 9652261610

- Tierney, Brian. 1979. Church Law and Constitutional Thought in the Middle Ages. London: Variorum Reprints. ISBN 0860780368

- Tierney, Brian. 1988 (original 1964). The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300, reprint ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802067018

- Vinogradoff, Paul. 2004 (original 1909). Roman Law in Medieval Europe, reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417949090

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article