A picture of a lightbulb is associated with someone having an idea, an example of creativity.

Creativity is a phenomenon whereby something new and valuable is formed. The created item may be intangible (such as an idea, a scientific theory, a musical composition, or a joke) or a physical object (such as an invention, a printed literary work, or a painting).

Scholarly interest in creativity is found in a number of disciplines, primarily psychology, business studies, and cognitive science. However, it can also be found in education, the humanities (philosophy, the arts) and theology, social sciences (sociology, linguistics, economics), engineering, technology and mathematics. These disciplines cover the relations between creativity and general intelligence, personality type, mental and neural processes, mental health, artificial intelligence; the potential for fostering creativity through education, training, leadership and organizational practices;[1] the factors that determine how creativity is evaluated and perceived;[2] the fostering of creativity for national economic benefit; and the application of creative resources to improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning.

Etymology[edit]

The English word creativity comes from the Latin term creare, «to create, make»: its derivational suffixes also come from Latin. The word «create» appeared in English as early as the 14th century, notably in Chaucer (in The Parson’s Tale[3]), to indicate divine creation.[4]

However, its modern meaning as an act of human creation did not emerge until after the Enlightenment.[4]

Definition[edit]

In a summary of scientific research into creativity, Michael Mumford suggested: «Over the course of the last decade, however, we seem to have reached a general agreement that creativity involves the production of novel, useful products» (Mumford, 2003, p. 110),[5] or, in Robert Sternberg’s words, the production of «something original and worthwhile».[6] Authors have diverged dramatically in their precise definitions beyond these general commonalities: Peter Meusburger estimates that over a hundred different definitions can be found in the literature, typically elaborating on the context (field, organisation, environment etc.) which determines the originality and/or appropriateness of the created object, and the processes through which it came about.[7] As an illustration, one definition given by Dr. E. Paul Torrance in the context of assessing an individual’s creative ability, described it as «a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions, making guesses, or formulating hypotheses about the deficiencies: testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results.»[8]

Creativity in general is usually distinguished from innovation in particular, where the stress is on implementation. For example, Teresa Amabile and Pratt (2016) define creativity as production of novel and useful ideas and innovation as implementation of creative ideas,[9] while the OECD and Eurostat state that «Innovation is more than a new idea or an invention. An innovation requires implementation, either by being put into active use or by being made available for use by other parties, firms, individuals or organisations.»[10]

There is also an emotional creativity[11] which is described as a pattern of cognitive abilities and personality traits related to originality and appropriateness in emotional experience.[12]

Aspects[edit]

Theories of creativity (particularly investigation of why some people are more creative than others) have focused on a variety of aspects. The dominant factors are usually identified as «the four Ps» – process, product, person, and place/press, a framework first put forward by Mel Rhodes.[13] A focus on process is shown in cognitive approaches that try to describe thought mechanisms and techniques for creative thinking. Theories invoking divergent rather than convergent thinking (such as Guilford), or those describing the staging of the creative process (such as Wallas) are primarily theories of creative process. A focus on creative product usually appears in attempts to assess creative output, whether for psychometrics (see below) or in understanding why some objects are considered creative. It is from a consideration of product that the standard definition of creativity as the production of something novel and useful arises.[14]

A focus on the nature of the creative person considers more general intellectual habits, such as openness, levels of ideation, autonomy, expertise, exploratory behavior, and so on. A focus on place (sometimes called press) considers the circumstances in which creativity flourishes, such as degrees of autonomy, access to resources, and the nature of gatekeepers. Creative lifestyles are characterized by nonconforming attitudes and behaviors as well as flexibility.[15]

In 2013, based on a sociocultural critique of the Four P model as individualistic, static, and decontextualised, Glǎveanu proposed a «five A’s» model consisting of actor, action, artifact, audience, and affordance.[16] In this model, the actor is the person with attributes, but also located within social networks; action is the process of creativity not only in internal cognitive terms, but also external, bridging the gap between ideation and implentation; artifact emphasises how creative products typically represent cumulative innovations over time rather than abrupt discontinuities; and «press/place» is divided into audience and affordance, which consider the interdependence of the creative individual with the social and material world respectively. Although not supplanting the four Ps model in creativity research, the five As model has exerted influence over the direction of some creativity research,[17] and has been credited with bringing coherence to studies across a number of creative domains.[18]

Conceptual history[edit]

Greek philosophers like Plato rejected the concept of creativity, preferring to see art as a form of discovery. Asked in The Republic, «Will we say, of a painter, that he makes something?», Plato answers, «Certainly not, he merely imitates.»[19]

Ancient[edit]

Most ancient cultures, including thinkers of Ancient Greece,[19] Ancient China, and Ancient India,[20] lacked the concept of creativity, seeing art as a form of discovery and not creation. The ancient Greeks had no terms corresponding to «to create» or «creator» except for the expression «poiein» («to make»), which only applied to poiesis (poetry) and to the poietes (poet, or «maker») who made it. Plato did not believe in art as a form of creation. Asked in The Republic,[21] «Will we say, of a painter, that he makes something?», he answers, «Certainly not, he merely imitates.»[19]

It is commonly argued that the notion of «creativity» originated in Western cultures through Christianity, as a matter of divine inspiration.[4] According to the historian Daniel J. Boorstin, «the early Western conception of creativity was the Biblical story of creation given in the Genesis.»[22] However, this is not creativity in the modern sense, which did not arise until the Renaissance. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, creativity was the sole province of God; humans were not considered to have the ability to create something new except as an expression of God’s work.[23] A concept similar to that of Christianity existed in Greek culture. For instance, Muses were seen as mediating inspiration from the Gods.[24] Romans and Greeks invoked the concept of an external creative «daemon» (Greek) or «genius» (Latin), linked to the sacred or the divine. However, none of these views are similar to the modern concept of creativity, and the rejection of creativity in favor of discovery and the belief that individual creation was a conduit of the divine would dominate the West probably until the Renaissance and even later.[23][25]

Renaissance[edit]

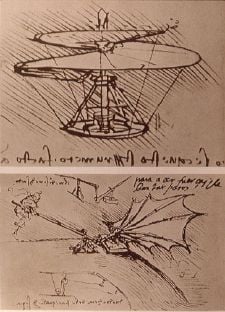

It was during the Renaissance that creativity was first seen, not as a conduit for the divine, but from the abilities of «great men».[25] The development of the modern concept of creativity began in the Renaissance, when creation began to be perceived as having originated from the abilities of the individual and not God. This could be attributed to the leading intellectual movement of the time, aptly named humanism, which developed an intensely human-centric outlook on the world, valuing the intellect and achievement of the individual.[26] From this philosophy arose the Renaissance man (or polymath), an individual who embodies the principals of humanism in their ceaseless courtship with knowledge and creation.[27] One of the most well-known and immensely accomplished examples is Leonardo da Vinci.

Enlightenment and thereafter[edit]

However, the shift from divine inspiration to the abilities of the individual was gradual and would not become immediately apparent until the Enlightenment.[25] By the 18th century and the Age of Enlightenment, mention of creativity (notably in aesthetics), linked with the concept of imagination, became more frequent.[28] In the writing of Thomas Hobbes, imagination became a key element of human cognition;[4] William Duff was one of the first to identify imagination as a quality of genius, typifying the separation being made between talent (productive, but breaking no new ground) and genius.[24]

As a direct and independent topic of study, creativity effectively received no attention until the 19th century.[24] Runco and Albert argue that creativity as the subject of proper study began seriously to emerge in the late 19th century with the increased interest in individual differences inspired by the arrival of Darwinism. In particular, they refer to the work of Francis Galton, who through his eugenicist outlook took a keen interest in the heritability of intelligence, with creativity taken as an aspect of genius.[4]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading mathematicians and scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz (1896) and Henri Poincaré (1908) began to reflect on and publicly discuss their creative processes.

Modern[edit]

The insights of Poincaré and von Helmholtz were built on in early accounts of the creative process by pioneering theorists such as Graham Wallas[29] and Max Wertheimer. In his work Art of Thought, published in 1926, Wallas presented one of the first models of the creative process. In the Wallas stage model, creative insights and illuminations may be explained by a process consisting of five stages:

- (i) preparation (preparatory work on a problem that focuses the individual’s mind on the problem and explores the problem’s dimensions),

- (ii) incubation (where the problem is internalized into the unconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening),

- (iii) intimation (the creative person gets a «feeling» that a solution is on its way),

- (iv) illumination or insight (where the creative idea bursts forth from its preconscious processing into conscious awareness);

- (v) verification (where the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied).

Wallas’ model is often treated as four stages, with «intimation» seen as a sub-stage.

Wallas considered creativity to be a legacy of the evolutionary process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments. Simonton[30] provides an updated perspective on this view in his book, Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity.

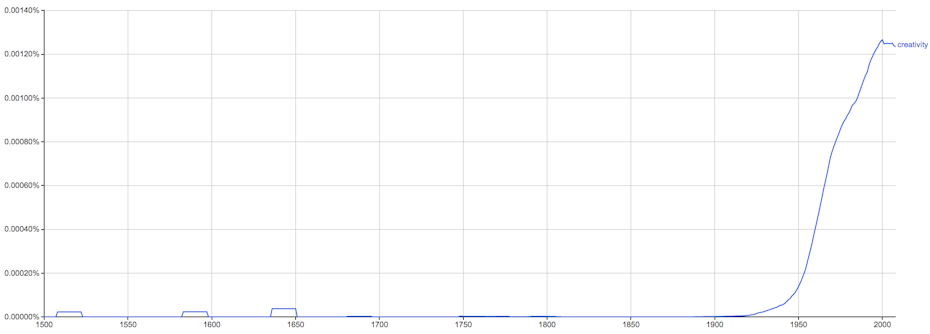

In 1927, Alfred North Whitehead gave the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh, later published as Process and Reality.[31] He is credited with having coined the term «creativity» to serve as the ultimate category of his metaphysical scheme: «Whitehead actually coined the term – our term, still the preferred currency of exchange among literature, science, and the arts… a term that quickly became so popular, so omnipresent, that its invention within living memory, and by Alfred North Whitehead of all people, quickly became occluded».[32]

Although psychometric studies of creativity had been conducted by The London School of Psychology as early as 1927 with the work of H. L. Hargreaves into the Faculty of Imagination,[33] the formal psychometric measurement of creativity, from the standpoint of orthodox psychological literature, is usually considered to have begun with J. P. Guilford’s address to the American Psychological Association in 1950.[34] The address helped to popularize the study of creativity and to focus attention on scientific approaches to conceptualizing creativity. Statistical analyses led to the recognition of creativity (as measured) as a separate aspect of human cognition to IQ-type intelligence, into which it had previously been subsumed. Guilford’s work suggested that above a threshold level of IQ, the relationship between creativity and classically measured intelligence broke down.[35]

«Four C» model[edit]

James C. Kaufman and Beghetto introduced a «four C» model of creativity; mini-c («transformative learning» involving «personally meaningful interpretations of experiences, actions, and insights»), little-c (everyday problem solving and creative expression), Pro-C (exhibited by people who are professionally or vocationally creative though not necessarily eminent) and Big-C (creativity considered great in the given field). This model was intended to help accommodate models and theories of creativity that stressed competence as an essential component and the historical transformation of a creative domain as the highest mark of creativity. It also, the authors argued, made a useful framework for analyzing creative processes in individuals.[36]

The contrast of terms «Big C» and «Little c» has been widely used. Kozbelt, Beghetto and Runco use a little-c/Big-C model to review major theories of creativity.[35] Margaret Boden distinguishes between h-creativity (historical) and p-creativity (personal).[37]

Robinson[38] and Anna Craft[39] have focused on creativity in a general population, particularly with respect to education. Craft makes a similar distinction between «high» and «little c» creativity[39] and cites Ken Robinson as referring to «high» and «democratic» creativity. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi[40] has defined creativity in terms of those individuals judged to have made significant creative, perhaps domain-changing contributions. Simonton has analysed the career trajectories of eminent creative people in order to map patterns and predictors of creative productivity.[41]

Process theories[edit]

There has been much empirical study in psychology and cognitive science of the processes through which creativity occurs. Interpretation of the results of these studies has led to several possible explanations of the sources and methods of creativity.

Incubation[edit]

Incubation is a temporary break from creative problem solving that can result in insight.[42] There has been some empirical research looking at whether, as the concept of «incubation» in Wallas’ model implies, a period of interruption or rest from a problem may aid creative problem-solving. Early work proposed that creative solutions to problems arise mysteriously from the unconscious mind while the conscious mind is occupied on other tasks.[43]

This hypothesis is discussed in Csikszentmihalyi’s five-phase model of the creative process which describes incubation as a time that your unconscious takes over. This was supposed to allow for unique connections to be made without our consciousness trying to make logical order out of the problem.[44]

Ward[45] lists various hypotheses that have been advanced to explain why incubation may aid creative problem-solving, and notes how some empirical evidence is consistent with a different hypothesis: Incubation aids creative problem in that it enables «forgetting» of misleading clues. Absence of incubation may lead the problem solver to become fixated on inappropriate strategies of solving the problem.[46]

Convergent and divergent thinking[edit]

J. P. Guilford[47] drew a distinction between convergent and divergent production (commonly renamed convergent and divergent thinking). Convergent thinking involves aiming for a single, correct solution to a problem, whereas divergent thinking involves creative generation of multiple answers to a set problem. Divergent thinking is sometimes used as a synonym for creativity in psychology literature or is considered the necessary precursor to creativity.[48] Other researchers have occasionally used the terms flexible thinking or fluid intelligence, which are roughly similar to (but not synonymous with) creativity.[49]

Creative cognition approach[edit]

In 1992, Finke et al. proposed the «Geneplore» model, in which creativity takes place in two phases: a generative phase, where an individual constructs mental representations called «preinventive» structures, and an exploratory phase where those structures are used to come up with creative ideas. [50] Some evidence shows that when people use their imagination to develop new ideas, those ideas are heavily structured in predictable ways by the properties of existing categories and concepts.[51] Weisberg[52] argued, by contrast, that creativity only involves ordinary cognitive processes yielding extraordinary results.

The Explicit–Implicit Interaction (EII) theory[edit]

Helie and Sun[53] more recently proposed a unified framework for understanding creativity in problem solving, namely the Explicit–Implicit Interaction (EII) theory of creativity. This new theory constitutes an attempt at providing a more unified explanation of relevant phenomena (in part by reinterpreting/integrating various fragmentary existing theories of incubation and insight).

The EII theory relies mainly on five basic principles, namely:

- The co-existence of and the difference between explicit and implicit knowledge;

- The simultaneous involvement of implicit and explicit processes in most tasks;

- The redundant representation of explicit and implicit knowledge;

- The integration of the results of explicit and implicit processing;

- The iterative (and possibly bidirectional) processing.

A computational implementation of the theory was developed based on the CLARION cognitive architecture and used to simulate relevant human data. This work represents an initial step in the development of process-based theories of creativity encompassing incubation, insight, and various other related phenomena.

Conceptual blending[edit]

In The Act of Creation, Arthur Koestler introduced the concept of bisociation – that creativity arises as a result of the intersection of two quite different frames of reference.[54] This idea was later developed into conceptual blending. In the 1990s, various approaches in cognitive science that dealt with metaphor, analogy, and structure mapping have been converging, and a new integrative approach to the study of creativity in science, art and humor has emerged under the label conceptual blending.

Honing theory[edit]

Honing theory, developed principally by psychologist Liane Gabora, posits that creativity arises due to the self-organizing, self-mending nature of a worldview. The creative process is a way in which the individual hones (and re-hones) an integrated worldview. Honing theory places emphasis not only on the externally visible creative outcome but also the internal cognitive restructuring and repair of the worldview brought about by the creative process. When faced with a creatively demanding task, there is an interaction between the conception of the task and the worldview. The conception of the task changes through interaction with the worldview, and the worldview changes through interaction with the task. This interaction is reiterated until the task is complete, at which point not only is the task conceived of differently, but the worldview is subtly or drastically transformed as it follows the natural tendency of a worldview to attempt to resolve dissonance and seek internal consistency amongst its components, whether they be ideas, attitudes, or bits of knowledge.

A central feature of honing theory is the notion of a potentiality state.[55] Honing theory posits that creative thought proceeds not by searching through and randomly ‘mutating’ predefined possibilities, but by drawing upon associations that exist due to overlap in the distributed neural cell assemblies that participate in the encoding of experiences in memory. Midway through the creative process one may have made associations between the current task and previous experiences, but not yet disambiguated which aspects of those previous experiences are relevant to the current task. Thus the creative idea may feel ‘half-baked’. It is at that point that it can be said to be in a potentiality state, because how it will actualize depends on the different internally or externally generated contexts it interacts with.

Honing theory is held to explain certain phenomena not dealt with by other theories of creativity – for example, how different works by the same creator are observed in studies to exhibit a recognizable style or ‘voice’, even in different creative outlets. This is not predicted by theories of creativity that emphasize chance processes or the accumulation of expertise, but it is predicted by honing theory, according to which personal style reflects the creator’s uniquely structured worldview. Another example is in the environmental stimulus for creativity. Creativity is commonly considered to be fostered by a supportive, nurturing, trustworthy environment conducive to self-actualization. However, research shows that creativity is also associated with childhood adversity, which would stimulate honing.

Everyday imaginative thought[edit]

In everyday thought, people often spontaneously imagine alternatives to reality when they think «if only…».[56] Their counterfactual thinking is viewed as an example of everyday creative processes.[57] It has been proposed that the creation of counterfactual alternatives to reality depends on similar cognitive processes to rational thought.[58]

Dialectical theory of creativity[edit]

The term «dialectical theory of creativity» dates back to psychoanalyst Daniel Dervin[59] and was later developed into an interdisciplinary theory.[60] The dialectical theory of creativity starts with the antique concept that creativity takes place in an interplay between order and chaos. Similar ideas can be found in neurosciences and psychology. Neurobiologically, it can be shown that the creative process takes place in a dynamic interplay between coherence and incoherence that leads to new and usable neuronal networks. Psychology shows how the dialectics of convergent and focused thinking with divergent and associative thinking leads to new ideas and products.[61] Also, creative personality traits like the ‘Big Five’ seem to be dialectically intertwined in the creative process: emotional instability vs. stability, extraversion vs. introversion, openness vs. reserve, agreeableness vs. antagonism, and disinhibition vs. constraint.[62] The dialectical theory of creativity applies also to counseling and psychotherapy.[63]

Neuroeconomic framework for creative cognition[edit]

Lin and Vartanian developed a framework that provides an integrative neurobiological description of creative cognition.[64] This interdisciplinary framework integrates theoretical principles and empirical results from neuroeconomics, reinforcement learning, cognitive neuroscience, and neurotransmission research on the locus coeruleus system. It describes how decision-making processes studied by neuroeconomists as well as activity in the locus coeruleus system underlie creative cognition and the large-scale brain network dynamics associated with creativity.[65] It suggests that creativity is an optimization and utility-maximization problem that requires individuals to determine the optimal way to exploit and explore ideas (multi-armed bandit problem). This utility maximization process is thought to be mediated by the locus coeruleus system[66] and this creativity framework describes how tonic and phasic locus coerulues activity work in conjunction to facilitate the exploiting and exploring of creative ideas. This framework not only explains previous empirical results but also makes novel and falsifiable predictions at different levels of analysis (ranging from neurobiological to cognitive and personality differences).

Behaviorism theory of creativity[edit]

Skinner attributed creativity to accidental behaviors that are reinforced by the environment.[67] Spontaneous behaviors done by living creatures reflect past learned behavior.[68] In Karen Pryor’s book Don’t Shoot the Dog she refers to how she reinforced a dolphin to display novel behaviors. This is what one can attribute to both those who are creative and those who appreciate creativity. A behaviorist may say that prior learning caused novel behaviors to be reinforced many times over and the individual has been shaped to produce increasingly novel behaviors.[69] A creative person, according to this definition, would be someone who has been reinforced more often for novel behaviors than others. Behaviorists would also suggest that anyone can be creative, they just need to be reinforced to learn to produce novel behaviors.

Personal assessment[edit]

Psychometric approaches[edit]

J. P. Guilford’s group,[47] which pioneered the modern psychometric study of creativity, constructed several performance-based tests to measure creativity in 1967:

- Plot Titles, where participants are given the plot of a story and asked to write original titles.

- Quick Responses is a word-association test scored for uncommonness.

- Figure Concepts, where participants were given simple drawings of objects and individuals and asked to find qualities or features that are common by two or more drawings; these were scored for uncommonness.

- Unusual Uses is finding unusual uses for common everyday objects such as bricks.

- Remote Associations, where participants are asked to find a word between two given words (e.g. Hand _____ Call)

- Remote Consequences, where participants are asked to generate a list of consequences of unexpected events (e.g. loss of gravity)

Originally, Guilford was trying to create a model for intellect as a whole, but in doing so also created a model for creativity. Guilford made an important assumption for creative research: creativity is not one abstract concept. The idea that creativity is a category rather than one single concept opened up the ability for other researchers to look at creativity with a whole new perspective.[70][71]

Additionally, Guilford hypothesized one of the first models for the components of creativity. He explained that creativity was a result of having:

- Sensitivity to problems, or the ability to recognize problems;

- Fluency, which encompasses

- a. Ideational fluency, or the ability rapidly to produce a variety of ideas that fulfill stated requirements;

- b. Associational fluency, or the ability to generate a list of words, each of which is associated with a given word;

- c. Expressional fluency, or the ability to organize words into larger units, such as phrases, sentences, and paragraphs;

- Flexibility, which encompasses

- a. Spontaneous flexibility, or the ability to demonstrate flexibility;

- b. Adaptive flexibility, or the ability to produce responses that are novel and high in quality.

This represents the base model by which several researchers would take and alter to produce their new theories of creativity years later.[70] Building on Guilford’s work, tests were developed, sometimes called Divergent Thinking (DT) tests have been both supported[72] and criticized.[73] For example, Torrance[74] developed the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking in 1966.[75] They involved task of divergent thinking and other problem-solving skills, which were scored on:

- Fluency – The total number of interpretable, meaningful, and relevant ideas generated in response to the stimulus.

- Originality – The statistical rarity of the responses among the test subjects.

- Elaboration – The amount of detail in the responses.

Considerable progress has been made in automated scoring of divergent thinking tests using semantic approach. When compared to human raters, NLP techniques were shown to be reliable and valid in scoring the originality.[76][77] The reported computer programs were able to achieve a correlation of 0.60 and 0.72 respectively to human graders.

Semantic networks were also used to devise originality scores that yielded significant correlations with socio-personal measures.[78] Most recently, an NSF-funded[79] team of researchers led by James C. Kaufman and Mark A. Runco[80] combined expertise in creativity research, natural language processing, computational linguistics, and statistical data analysis to devise a scalable system for computerized automated testing (SparcIt Creativity Index Testing system). This system enabled automated scoring of DT tests that is reliable, objective, and scalable, thus addressing most of the issues of DT tests that had been found and reported.[73] The resultant computer system was able to achieve a correlation of 0.73 to human graders.[81]

[edit]

Some researchers have taken a social-personality approach to the measurement of creativity. In these studies, personality traits such as independence of judgement, self-confidence, attraction to complexity, aesthetic orientation, and risk-taking are used as measures of the creativity of individuals.[34] A meta-analysis by Gregory Feist showed that creative people tend to be «more open to new experiences, less conventional and less conscientious, more self-confident, self-accepting, driven, ambitious, dominant, hostile, and impulsive.» Openness, conscientiousness, self-acceptance, hostility, and impulsivity had the strongest effects of the traits listed.[82] Within the framework of the Big Five model of personality, some consistent traits have emerged.[83] Openness to experience has been shown to be consistently related to a whole host of different assessments of creativity.[84] Among the other Big Five traits, research has demonstrated subtle differences between different domains of creativity. Compared to non-artists, artists tend to have higher levels of openness to experience and lower levels of conscientiousness, while scientists are more open to experience, conscientious, and higher in the confidence-dominance facets of extraversion compared to non-scientists.[82]

Self-report questionnaires[edit]

An alternative is using biographical methods. These methods use quantitative characteristics such as the number of publications, patents, or performances of a work. While this method was originally developed for highly creative personalities, today it is also available as self-report questionnaires supplemented with frequent, less outstanding creative behaviors such as writing a short story or creating your own recipes. For example, the Creative Achievement Questionnaire, a self-report test that measures creative achievement across 10 domains, was described in 2005 and shown to be reliable and valid when compared to other measures of creativity and to independent evaluation of creative output.[85] Besides the English original, it was also used in a Chinese,[86] French,[87] and German-speaking[88] version. It is the self-report questionnaire most frequently used in research.[86]

Intelligence[edit]

The potential relationship between creativity and intelligence has been of interest since the late 1900s, when a multitude of influential studies – from Getzels & Jackson,[89] Barron,[90] Wallach & Kogan,[91] and Guilford[92] – focused not only on creativity, but also on intelligence. This joint focus highlights both the theoretical and practical importance of the relationship: researchers are interested not only if the constructs are related, but also how and why.[93]

There are multiple theories accounting for their relationship, with the three main theories as follows:

- Threshold Theory – Intelligence is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for creativity. There is a moderate positive relationship between creativity and intelligence until IQ ~120.[90][92]

- Certification Theory – Creativity is not intrinsically related to intelligence. Instead, individuals are required to meet the requisite level intelligence in order to gain a certain level of education/work, which then in turn offers the opportunity to be creative. Displays of creativity are moderated by intelligence.[94]

- Interference Theory – Extremely high intelligence might interfere with creative ability.[95]

Sternberg and O’Hara[96] proposed a framework of five possible relationships between creativity and intelligence:

- Creativity is a subset of intelligence

- Intelligence is a subset of creativity

- Creativity and intelligence are overlapping constructs

- Creativity and intelligence are part of the same construct (coincident sets)

- Creativity and intelligence are distinct constructs (disjoint sets)

Creativity as a subset of intelligence[edit]

A number of researchers include creativity, either explicitly or implicitly, as a key component of intelligence.

Examples of theories that include creativity as a subset of intelligence

- Sternberg’s Theory of Successful intelligence[95][96][97] (see Triarchic theory of intelligence) includes creativity as a main component, and comprises three sub-theories: Componential (Analytic), Contextual (Practical), and Experiential (Creative). Experiential sub-theory – the ability to use pre-existing knowledge and skills to solve new and novel problems – is directly related to creativity.

- The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory includes creativity as a subset of intelligence. Specifically, it is associated with the broad group factor of long-term storage and retrieval (Glr). Glr narrow abilities relating to creativity include:[98] ideational fluency, associational fluency, and originality/creativity. Silvia et al.[99] conducted a study to look at the relationship between divergent thinking and verbal fluency tests, and reported that both fluency and originality in divergent thinking were significantly affected by the broad level Glr factor. Martindale[100] extended the CHC-theory in the sense that it was proposed that those individuals who are creative are also selective in their processing speed. Martindale argues that in the creative process, larger amounts of information are processed more slowly in the early stages, and as the individual begins to understand the problem, the processing speed is increased.

- The Dual Process Theory of Intelligence[101] posits a two-factor/type model of intelligence. Type 1 is a conscious process, and concerns goal directed thoughts, which are explained by g. Type 2 is an unconscious process, and concerns spontaneous cognition, which encompasses daydreaming and implicit learning ability. Kaufman argues that creativity occurs as a result of Type 1 and Type 2 processes working together in combination. The use of each type in the creative process can be used to varying degrees.

Intelligence as a subset of creativity[edit]

In this relationship model, intelligence is a key component in the development of creativity.

Theories of creativity that include intelligence as a subset of creativity

- Sternberg & Lubart’s Investment Theory.[102][103] Using the metaphor of a stock market, they demonstrate that creative thinkers are like good investors – they buy low and sell high (in their ideas). Like under/low-valued stock, creative individuals generate unique ideas that are initially rejected by other people. The creative individual has to persevere, and convince the others of the ideas value. After convincing the others, and thus increasing the ideas value, the creative individual ‘sells high’ by leaving the idea with the other people, and moves onto generating another idea. According to this theory, six distinct, but related elements contribute to successful creativity: intelligence, knowledge, thinking styles, personality, motivation, and environment. Intelligence is just one of the six factors that can either solely, or in conjunction with the other five factors, generate creative thoughts.

- Amabile’s Componential Model of Creativity.[104][105] In this model, there are three within-individual components needed for creativity – domain-relevant skills, creativity-relevant processes, and task motivation – and 1 component external to the individual: their surrounding social environment. Creativity requires a confluence of all components. High creativity will result when an individual is: intrinsically motivated, possesses both a high level of domain-relevant skills and has high skills in creative thinking, and is working in a highly creative environment.

- Amusement Park Theoretical Model.[106] In this four-step theory, both domain-specific and generalist views are integrated into a model of creativity. The researchers make use of the metaphor of the amusement park to demonstrate that within each of these creative levels, intelligence plays a key role:

- To get into the amusement park, there are initial requirements (e.g., time/transport to go to the park). Initial requirements (like intelligence) are necessary, but not sufficient for creativity. They are more like prerequisites for creativity, and if an individual does not possess the basic level of the initial requirement (intelligence), then they will not be able to generate creative thoughts/behaviour.

- Secondly are the subcomponents – general thematic areas – that increase in specificity. Like choosing which type of amusement park to visit (e.g. a zoo or a water park), these areas relate to the areas in which someone could be creative (e.g. poetry).

- Thirdly, there are specific domains. After choosing the type of park to visit e.g. waterpark, you then have to choose which specific park to go to. Within the poetry domain, there are many different types (e.g. free verse, riddles, sonnet, etc.) that have to be selected from.

- Lastly, there are micro-domains. These are the specific tasks that reside within each domain e.g. individual lines in a free verse poem / individual rides at the waterpark.

Creativity and intelligence as overlapping yet distinct constructs[edit]

This possible relationship concerns creativity and intelligence as distinct, but intersecting constructs.

Theories that include Creativity and Intelligence as Overlapping Yet Distinct Constructs

- Renzulli’s Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness.[107] In this conceptualisation, giftedness occurs as a result from the overlap of above average intellectual ability, creativity, and task commitment. Under this view, creativity and intelligence are distinct constructs, but they do overlap under the correct conditions.

- PASS theory of intelligence. In this theory, the planning component – relating to the ability to solve problems, make decisions and take action – strongly overlaps with the concept of creativity.[108]

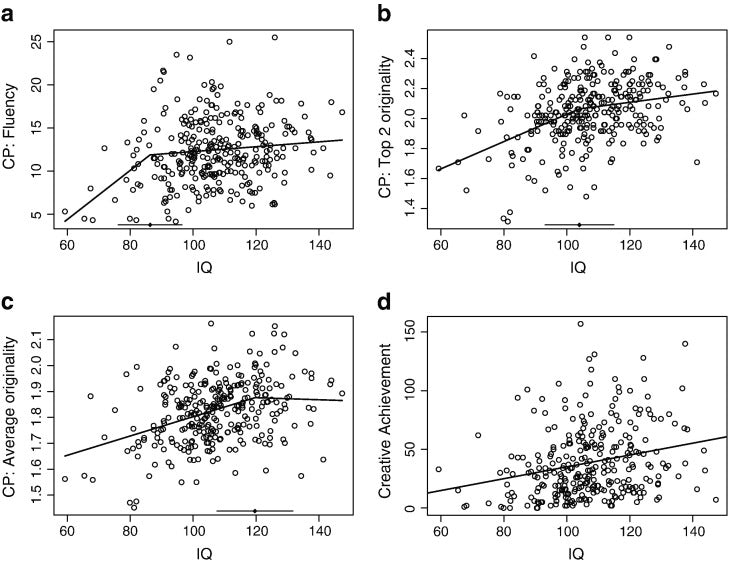

- Threshold Theory (TT). A number of previous research findings have suggested that a threshold exists in the relationship between creativity and intelligence – both constructs are moderately positively correlated up to an IQ of ~120. Above this threshold of an IQ of 120, if there is a relationship at all, it is small and weak.[89][90][109] TT posits that a moderate level of intelligence is necessary for creativity.

In support of the TT, Barron[90][110] reported finding a non-significant correlation between creativity and intelligence in a gifted sample and a significant correlation in a non-gifted sample. Yamamoto[111] in a sample of secondary school children, reported a significant correlation between creativity and intelligence of r = 0.3, and reported no significant correlation when the sample consisted of gifted children. Fuchs-Beauchamp et al.[112] in a sample of preschoolers found that creativity and intelligence correlated from r = 0.19 to r = 0.49 in the group of children who had an IQ below the threshold; and in the group above the threshold, the correlations were r = <0.12. Cho et al.[113] reported a correlation of 0.40 between creativity and intelligence in the average IQ group of a sample of adolescents and adults; and a correlation of close to r = 0.0 for the high IQ group. Jauk et al.[114] found support for the TT, but only for measures of creative potential, not creative performance.

Much modern day research reports findings against TT. Wai et al.[115] in a study using data from the longitudinal Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth – a cohort of elite students from early adolescence into adulthood – found that differences in SAT scores at age 13 were predictive of creative real-life outcomes 20 years later. Kim’s[116] meta-analysis of 21 studies did not find any supporting evidence for TT, and instead negligible correlations were reported between intelligence, creativity, and divergent thinking both below and above IQ’s of 120. Preckel et al.,[117] investigating fluid intelligence and creativity, reported small correlations of r = 0.3 to r = 0.4 across all levels of cognitive ability.

Creativity and intelligence as coincident sets[edit]

Under this view, researchers posit that there are no differences in the mechanisms underlying creativity in those used in normal problem solving; and in normal problem solving, there is no need for creativity. Thus, creativity and Intelligence (problem solving) are the same thing. Perkins[118] referred to this as the ‘nothing-special’ view.

Weisberg & Alba[119] examined problem solving by having participants complete the nine dots puzzle – where the participants are asked to connect all nine dots in the three rows of three dots using four straight lines or less, without lifting their pen or tracing the same line twice. The problem can only be solved if the lines go outside the boundaries of the square of dots. Results demonstrated that even when participants were given this insight, they still found it difficult to solve the problem, thus showing that to successfully complete the task it is not just insight (or creativity) that is required.

Creativity and intelligence as disjoint sets[edit]

In this view, creativity and intelligence are completely different, unrelated constructs.

Getzels and Jackson[89] administered five creativity measures to a group of 449 children from grades 6–12, and compared these test findings to results from previously administered (by the school) IQ tests. They found that the correlation between the creativity measures and IQ was r = 0.26. The high creativity group scored in the top 20% of the overall creativity measures, but were not included in the top 20% of IQ scorers. The high intelligence group scored the opposite: they scored in the top 20% for IQ, but were outside the top 20% scorers for creativity, thus showing that creativity and intelligence are distinct and unrelated.

However, this work has been heavily criticised. Wallach and Kogan[91] highlighted that the creativity measures were not only weakly related to one another (to the extent that they were no more related to one another than they were with IQ), but they seemed to also draw upon non-creative skills. McNemar[120] noted that there were major measurement issues, in that the IQ scores were a mixture from three different IQ tests.

Wallach and Kogan[91] administered five measures of creativity, each of which resulted in a score for originality and fluency; and 10 measures of general intelligence to 151 5th grade children. These tests were untimed, and given in a game-like manner (aiming to facilitate creativity). Inter-correlations between creativity tests were on average r = 0.41. Inter-correlations between intelligence measures were on average r = 0.51 with each other. Creativity tests and intelligence measures correlated r = 0.09.

Neuroscience[edit]

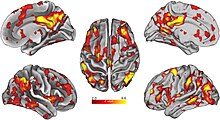

Distributed functional brain network associated with divergent thinking

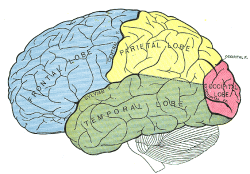

The neuroscience of creativity looks at the operation of the brain during creative behaviour. It has been addressed[121] in the article «Creative Innovation: Possible Brain Mechanisms». The authors write that «creative innovation might require coactivation and communication between regions of the brain that ordinarily are not strongly connected.» Highly creative people who excel at creative innovation tend to differ from others in three ways:

- they have a high level of specialized knowledge,

- they are capable of divergent thinking mediated by the frontal lobe.

- and they are able to modulate neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine in their frontal lobe.

Thus, the frontal lobe appears to be the part of the cortex that is most important for creativity.

This article also explored the links between creativity and sleep, mood and addiction disorders, and depression.

In 2005, Alice Flaherty presented a three-factor model of the creative drive. Drawing from evidence in brain imaging, drug studies and lesion analysis, she described the creative drive as resulting from an interaction of the frontal lobes, the temporal lobes, and dopamine from the limbic system. The frontal lobes can be seen as responsible for idea generation, and the temporal lobes for idea editing and evaluation. Abnormalities in the frontal lobe (such as depression or anxiety) generally decrease creativity, while abnormalities in the temporal lobe often increase creativity. High activity in the temporal lobe typically inhibits activity in the frontal lobe, and vice versa. High dopamine levels increase general arousal and goal directed behaviors and reduce latent inhibition, and all three effects increase the drive to generate ideas.[122] A 2015 study on creativity found that it involves the interaction of multiple neural networks, including those that support associative thinking, along with other default mode network functions.[123]

Similarly, in 2018, Lin and Vartanian proposed a neuroeconomic framework that precisely describes norepinephrine’s role in creativity and modulating large-scale brain networks associated with creativity.[64] This framework describes how neural activity in different brain regions and networks like the default mode network are tracking utility or subjective value of ideas.

In 2018, experiments showed that when the brain suppresses obvious or ‘known’ solutions, the outcome is solutions that are more creative. This suppression is mediated by alpha oscillations in the right temporal lobe.[124]

Working memory and the cerebellum[edit]

Vandervert[125] described how the brain’s frontal lobes and the cognitive functions of the cerebellum collaborate to produce creativity and innovation. Vandervert’s explanation rests on considerable evidence that all processes of working memory (responsible for processing all thought[126]) are adaptively modeled for increased efficiency by the cerebellum.[127] The cerebellum (consisting of 100 billion neurons, which is more than the entirety of the rest of the brain[128]) is also widely known to adaptively model all bodily movement for efficiency. The cerebellum’s adaptive models of working memory processing are then fed back to especially frontal lobe working memory control processes[129] where creative and innovative thoughts arise.[130] (Apparently, creative insight or the «aha» experience is then triggered in the temporal lobe.[131])

According to Vandervert, the details of creative adaptation begin in «forward» cerebellar models which are anticipatory/exploratory controls for movement and thought. These cerebellar processing and control architectures have been termed Hierarchical Modular Selection and Identification for Control (HMOSAIC).[132] New, hierarchically arranged levels of the cerebellar control architecture (HMOSAIC) develop as mental mulling in working memory is extended over time. These new levels of the control architecture are fed forward to the frontal lobes. Since the cerebellum adaptively models all movement and all levels of thought and emotion,[133] Vandervert’s approach helps explain creativity and innovation in sports, art, music, the design of video games, technology, mathematics, the child prodigy, and thought in general.

Essentially, Vandervert has argued that when a person is confronted with a challenging new situation, visual-spatial working memory and speech-related working memory are decomposed and re-composed (fractionated) by the cerebellum and then blended in the cerebral cortex in an attempt to deal with the new situation. With repeated attempts to deal with challenging situations, the cerebro-cerebellar blending process continues to optimize the efficiency of how working memory deals with the situation or problem.[134] Most recently, he has argued that this is the same process (only involving visual-spatial working memory and pre-language vocalization) that led to the evolution of language in humans.[135] Vandervert and Vandervert-Weathers have pointed out that this blending process, because it continuously optimizes efficiencies, constantly improves prototyping attempts toward the invention or innovation of new ideas, music, art, or technology.[136] Prototyping, they argue, not only produces new products, it trains the cerebro-cerebellar pathways involved to become more efficient at prototyping itself. Further, Vandervert and Vandervert-Weathers believe that this repetitive «mental prototyping» or mental rehearsal involving the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex explains the success of the self-driven, individualized patterning of repetitions initiated by the teaching methods of the Khan Academy. The model proposed by Vandervert has, however, received incisive critique from several authors.[137][138]

REM sleep[edit]

Creativity involves the forming of associative elements into new combinations that are useful or meet some requirement. Sleep aids this process.[139] REM rather than NREM sleep appears to be responsible.[140][141] This has been suggested to be due to changes in cholinergic and noradrenergic neuromodulation that occurs during REM sleep.[140] During this period of sleep, high levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus suppress feedback from the hippocampus to the neocortex, and lower levels of acetylcholine and norepinephrine in the neocortex encourage the spread of associational activity within neocortical areas without control from the hippocampus.[142] This is in contrast to waking consciousness, where higher levels of norepinephrine and acetylcholine inhibit recurrent connections in the neocortex. It is proposed that REM sleep aids creativity by allowing «neocortical structures to reorganize associative hierarchies, in which information from the hippocampus would be reinterpreted in relation to previous semantic representations or nodes.»[140]

Affect[edit]

Some theories suggest that creativity may be particularly susceptible to affective influence. As noted in voting behavior, the term «affect» in this context can refer to liking or disliking key aspects of the subject in question. This work largely follows from findings in psychology regarding the ways in which affective states are involved in human judgment and decision-making.[143]

Positive affect relations[edit]

According to Alice Isen, positive affect has three primary effects on cognitive activity:

- Positive affect makes additional cognitive material available for processing, increasing the number of cognitive elements available for association;

- Positive affect leads to defocused attention and a more complex cognitive context, increasing the breadth of those elements that are treated as relevant to the problem;

- Positive affect increases cognitive flexibility, increasing the probability that diverse cognitive elements will in fact become associated. Together, these processes lead positive affect to have a positive influence on creativity.

Barbara Fredrickson in her broaden-and-build model suggests that positive emotions such as joy and love broaden a person’s available repertoire of cognitions and actions, thus enhancing creativity.

According to these researchers, positive emotions increase the number of cognitive elements available for association (attention scope) and the number of elements that are relevant to the problem (cognitive scope). Day-by-day psychological experiences including emotions, perceptions, and motivation will significantly impact creative performance. Creativity is higher when emotions and perceptions are more positive and when intrinsic motivation is stronger.[144]

Various meta-analyses, such as Baas et al. (2008) of 66 studies about creativity and affect support the link between creativity and positive affect.[145][146]

Computational creativity[edit]

Jürgen Schmidhuber’s formal theory of creativity[147][148] postulates that creativity, curiosity, and interestingness are by-products of a simple computational principle for measuring and optimizing learning progress. Consider an agent able to manipulate its environment and thus its own sensory inputs. The agent can use a black box optimization method such as reinforcement learning to learn (through informed trial and error) sequences of actions that maximize the expected sum of its future reward signals. There are extrinsic reward signals for achieving externally given goals, such as finding food when hungry. But Schmidhuber’s objective function to be maximized also includes an additional, intrinsic term to model «wow-effects». This non-standard term motivates purely creative behavior of the agent even when there are no external goals. A wow-effect is formally defined as follows. As the agent is creating and predicting and encoding the continually growing history of actions and sensory inputs, it keeps improving the predictor or encoder, which can be implemented as an artificial neural network or some other machine learning device that can exploit regularities in the data to improve its performance over time. The improvements can be measured precisely, by computing the difference in computational costs (storage size, number of required synapses, errors, time) needed to encode new observations before and after learning. This difference depends on the encoder’s present subjective knowledge, which changes over time, but the theory formally takes this into account. The cost difference measures the strength of the present «wow-effect» due to sudden improvements in data compression or computational speed. It becomes an intrinsic reward signal for the action selector. The objective function thus motivates the action optimizer to create action sequences causing more wow-effects. Irregular, random data (or noise) do not permit any wow-effects or learning progress, and thus are «boring» by nature (providing no reward). Already known and predictable regularities also are boring. Temporarily interesting are only the initially unknown, novel, regular patterns in both actions and observations. This motivates the agent to perform continual, open-ended, active, creative exploration. Schmidhuber’s work is highly influential in intrinsic motivation which has emerged as a research topic in its own right as part of the study of artificial intelligence and robotics.

According to Schmidhuber, his objective function explains the activities of scientists, artists, and comedians.[149][150]

For example, physicists are motivated to create experiments leading to observations obeying previously unpublished physical laws permitting better data compression. Likewise, composers receive intrinsic reward for creating non-arbitrary melodies with unexpected but regular harmonies that permit wow-effects through data compression improvements.

Similarly, a comedian gets intrinsic reward for «inventing a novel joke with an unexpected punch line, related to the beginning of the story in an initially unexpected but quickly learnable way that also allows for better compression of the perceived data.»[151]

Schmidhuber argues that ongoing computer hardware advances will greatly scale up rudimentary artificial scientists and artists[clarification needed] based on simple implementations of the basic principle since 1990.[152]

He used the theory to create low-complexity art[153] and an attractive human face.[154]

Creativity and mental health[edit]

A study by psychologist J. Philippe Rushton found creativity to correlate with intelligence and psychoticism.[155] Another study found creativity to be greater in people with schizotypal personality disorder than in people with either schizophrenia or those without mental health conditions. While divergent thinking was associated with bilateral activation of the prefrontal cortex, schizotypal individuals were found to have much greater activation of their right prefrontal cortex.[156] This study hypothesizes that such individuals are better at accessing both hemispheres, allowing them to make novel associations at a faster rate. Consistent with this hypothesis, ambidexterity is also more common in people with schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. Three studies by Mark Batey and Adrian Furnham have demonstrated the relationships between schizotypal personalty disorder[157][158] and hypomanic personality[159] and several different measures of creativity.

Particularly strong links have been identified between creativity and mood disorders, particularly manic-depressive disorder (a.k.a. bipolar disorder) and depressive disorder (a.k.a. unipolar disorder). In Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, Kay Redfield Jamison summarizes studies of mood-disorder rates in writers, poets, and artists. She also explores research that identifies mood disorders in such famous writers and artists as Ernest Hemingway (who shot himself after electroconvulsive treatment), Virginia Woolf (who drowned herself when she felt a depressive episode coming on), composer Robert Schumann (who died in a mental institution), and even the famed visual artist Michelangelo.

A study looking at 300,000 persons with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or unipolar depression, and their relatives, found overrepresentation in creative professions for those with bipolar disorder as well as for undiagnosed siblings of those with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. There was no overall overrepresentation, but overrepresentation for artistic occupations, among those diagnosed with schizophrenia. There was no association for those with unipolar depression or their relatives.[160]

Another study involving more than one million people, conducted by Swedish researchers at the Karolinska Institute, reported a number of correlations between creative occupations and mental illnesses. Writers had a higher risk of anxiety and bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, unipolar depression, and substance abuse, and were almost twice as likely as the general population to kill themselves. Dancers and photographers were also more likely to have bipolar disorder.[161]

As a group, those in the creative professions were no more likely to have psychiatric disorders than other people, although they were more likely to have a close relative with a disorder, including anorexia and, to some extent, autism, the Journal of Psychiatric Research reports.[161]

People who have worked in the arts industry throughout history have faced many environmental factors that are associated with and can sometimes influence mental illness. Including things such as poverty, persecution, social alienation, psychological trauma, substance abuse, and high stress.[162] In fact, according to psychologist Robert Epstein, PhD, creativity can be obstructed through stress.[163] So, while research has found that people are the most creative in positive moods,[164] it might be pursuing a career that causes some problems.

Conversely, research has shown that creative activities such as art therapy, poetry writing, journaling, and reminiscence can promote mental well-being.[165][166]

Bipolar Disorders and Creativity[edit]

Nancy Andreasen was one of the first known researchers to carry out a large scale study revolving around creativity and whether mental illnesses have an impact on someone’s ability to be creative. Originally she had expected to find a link between creativity and schizophrenia but her research sample had no real history of schizophrenia from the book authors she pooled. Her findings instead showed that 80% of the creative group had previously had some form of mental illness episode in their lifetime.[167] When she performed follow up studies over a 15-year period, she found that 43% of the authors had bipolar disorder compared to the 1% of the general public that has the disease. In 1989 there was another study done by Kay Redfield Jamison that reaffirmed those statistics by having 38% of her sample of authors having a history of mood disorders.[168] Anthony Storr who is a prominent psychiatrist remarked that, «The creative process can be a way of protecting the individual against being overwhelmed by depression, a means of regaining a sense of mastery in those who have lost it, and, to a varying extent, a way of repairing the self-damaged by bereavement or by the loss of confidence in human relationships which accompanies depression from whatever cause.»[167]

According to a study done by Shapiro and Weisberg, there appears to be a positive correlation between the manic upswings of the cycles of bipolar disorder and the ability for an individual to be more creative.[169] The data that they had collected and analyzed through multiple tests showed that it was in fact not the depressive swing that many believe to bring forth dark creative spurts, but the act of climbing out of the depressive episode that sparked creativity. The reason behind this spur of creative genius could come from the type of self-image that the person has during a time of hypomania. A hypomanic person may be feeling a bolstered sense of self-confidence, creative confidence, and sense of individualism.[169]

In reports from people who were diagnosed with bipolar disorder they noted themselves as having a larger range of emotional understanding, heightened states of perception, and an ability to connect better with those in the world around them.[170] Other reported traits include higher rates of productivity, higher senses of self-awareness, and a greater understanding of empathy. Those who have bipolar disorder also understand their own sense of heightened creativity and ability to get immense amounts of tasks done all at once. McCraw, Parker, Fletcher, & Friend (2013) report that out of 219 participants (aged 19 to 63) that have been diagnosed bipolar disorder 82% of them reported having elevated feelings of creativity during the hypomanic swings.[171]

Giannouli believes that the creativity a person diagnosed with bipolar disorder feels comes as a form of «stress management».[172] In the realm of music, one might be expressing their stress or pains through the pieces they write in order to better understand those same feelings. Famous authors and musicians along with some actors would often attribute their wild enthusiasm to something like a hypomanic state.[173] The artistic side of society has also been notorious for behaviors that are seen as maladapted to societal norms. Side effects that come with bipolar disorder match up with many of the behaviors that we see in high-profile creative personalities; these include, but are not limited to, alcohol addiction, drug abuse including stimulants, depressants, hallucinogens and dissociatives, opioids, inhalants, and cannabis, difficulties in holding regular occupations, interpersonal problems, legal issues, and a high risk of suicide.[173]

Weisberg believes that the state of mania sets «free the powers of a thinker». What he implies here is that not only has the person become more creative they have fundamentally changed the kind of thoughts they produce.[174] In a study done of poets, who seem to have especially high percentages of bipolar authors, it was found that over a period of three years those poets would have cycles of really creative and powerful works of poetry. The timelines over the three-year study looked at the poet’s personal journals and their clinical records and found that the timelines between their most powerful poems matched that of their upswings in bipolar disorder.[174]

Personality[edit]

Creativity can be expressed in a number of different forms, depending on unique people and environments. A number of different theorists have suggested models of the creative person. One model suggests that there are four «Creativity Profiles» that can help produce growth, innovation, speed, etc.[175]

- (i) Incubate (Long-term Development)

- (ii) Imagine (Breakthrough Ideas)

- (iii) Improve (Incremental Adjustments)

- (iv) Invest (Short-term Goals)

Research by Dr Mark Batey of the Psychometrics at Work Research Group at Manchester Business School has suggested that the creative profile can be explained by four primary creativity traits with narrow facets within each

- (i) «Idea Generation» (Fluency, Originality, Incubation and Illumination)

- (ii) «Personality» (Curiosity and Tolerance for Ambiguity)

- (iii) «Motivation» (Intrinsic, Extrinsic and Achievement)

- (iv) «Confidence» (Producing, Sharing and Implementing)

This model was developed in a sample of 1000 working adults using the statistical techniques of Exploratory Factor Analysis followed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis by Structural Equation Modelling.[176]

An important aspect of the creativity profiling approach is to account for the tension between predicting the creative profile of an individual, as characterised by the psychometric approach, and the evidence that team creativity is founded on diversity and difference.[177]

One characteristic of creative people, as measured by some psychologists, is what is called divergent production. Divergent production is the ability of a person to generate a diverse assortment, yet an appropriate amount of responses to a given situation.[178] One way of measuring divergent production is by administering the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking.[179] The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking assesses the diversity, quantity, and appropriateness of participants responses to a variety of open-ended questions.

Other researchers of creativity see the difference in creative people as a cognitive process of dedication to problem solving and developing expertise in the field of their creative expression. Hard working people study the work of people before them and within their current area, become experts in their fields, and then have the ability to add to and build upon previous information in innovative and creative ways. In a study of projects by design students, students who had more knowledge on their subject on average had greater creativity within their projects.[180] Other researchers emphasize how creative people are better at balancing between divergent and convergent production, which depends on an individual’s innate preference or ability to explore and exploit ideas.[64]

The aspect of motivation within a person’s personality may predict creativity levels in the person. Motivation stems from two different sources, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is an internal drive within a person to participate or invest as a result of personal interest, desires, hopes, goals, etc. Extrinsic motivation is a drive from outside of a person and might take the form of payment, rewards, fame, approval from others, etc. Although extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation can both increase creativity in certain cases, strictly extrinsic motivation often impedes creativity in people.[181]

From a personality-traits perspective, there are a number of traits that are associated with creativity in people.[182] Creative people tend to be more open to new experiences, are more self-confident, are more ambitious, self-accepting, impulsive, driven, dominant, and hostile, compared to people with less creativity.

From an evolutionary perspective, creativity may be a result of the outcome of years of generating ideas. As ideas are continuously generated, the need to evolve produces a need for new ideas and developments. As a result, people have been creating and developing new, innovative, and creative ideas to build our progress as a society.[183]

In studying exceptionally creative people in history, some common traits in lifestyle and environment are often found. Creative people in history usually had supportive parents, but rigid and non-nurturing. Most had an interest in their field at an early age, and most had a highly supportive and skilled mentor in their field of interest. Often the field they chose was relatively uncharted, allowing for their creativity to be expressed more in a field with less previous information. Most exceptionally creative people devoted almost all of their time and energy into their craft, and after about a decade had a creative breakthrough of fame. Their lives were marked with extreme dedication and a cycle of hard-work and breakthroughs as a result of their determination.[184]

Another theory of creative people is the investment theory of creativity. This approach suggest that there are many individual and environmental factors that must exist in precise ways for extremely high levels of creativity opposed to average levels of creativity. In the investment sense, a person with their particular characteristics in their particular environment may see an opportunity to devote their time and energy into something that has been overlooked by others. The creative person develops an undervalued or under-recognised idea to the point that it is established as a new and creative idea. Just like in the financial world, some investments are worth the buy in, while others are less productive and do not build to the extent that the investor expected. This investment theory of creativity views creativity in a unique perspective compared to others, by asserting that creativity might rely to some extent on the right investment of effort being added to a field at the right time in the right way.[185]

Malevolent creativity[edit]

So called malevolent creativity is associated with the «dark side» of creativity.[186][187] This type of creativity is not typically accepted within society and is defined by the intention to cause harm to others through original and innovative means. Malevolent creativity should be distinguished from negative creativity in that negative creativity may unintentionally cause harm to others, whereas malevolent creativity is explicitly malevolently motivated. While it is often associated with criminal behaviour, it can also be observed in ordinary day-to-day life as lying, cheating and betrayal.[188]

Crime[edit]

Malevolent creativity is often a key contributor to crime and in its most destructive form can even manifest as terrorism. As creativity requires deviating from the conventional, there is a permanent tension between being creative and producing products that go too far and in some cases to the point of breaking the law. Aggression is a key predictor of malevolent creativity, and studies have also shown that increased levels of aggression also correlates to a higher likelihood of committing crime.[189]

Predictive factors[edit]

Although everyone shows some levels of malevolent creativity under certain conditions, those that have a higher propensity towards it have increased tendencies to deceive and manipulate others to their own gain. While malevolent creativity appears to dramatically increase when an individual is placed under unfair conditions, personality, particularly aggressiveness, is also a key predictor in anticipating levels of malevolent thinking. Researchers Harris and Reiter-Palmon investigated the role of aggression in levels of malevolent creativity, in particular levels of implicit aggression and the tendency to employ aggressive actions in response to problem solving. The personality traits of physical aggression, conscientiousness, emotional intelligence and implicit aggression all seem to be related with malevolent creativity.[187] Harris and Reiter-Palmon’s research showed that when subjects were presented with a problem that triggered malevolent creativity, participants high in implicit aggression and low in premeditation expressed the largest number of malevolently-themed solutions. When presented with the more benign problem that triggered prosocial motives of helping others and cooperating, those high in implicit aggression, even if they were high in impulsiveness, were far less destructive in their imagined solutions. They concluded premeditation, more than implicit aggression controlled an individual’s expression of malevolent creativity.[190]

The current measure for malevolent creativity is the 13-item test Malevolent Creativity Behaviour Scale (MCBS).[188]

Cultural differences in creativity[edit]

Creativity is viewed differently in different countries.[191] For example, cross-cultural research centered on Hong Kong found that Westerners view creativity more in terms of the individual attributes of a creative person, such as their aesthetic taste, while Chinese people view creativity more in terms of the social influence of creative people (i.e., what they can contribute to society).[192] Mpofu et al. surveyed 28 African languages and found that 27 had no word which directly translated to ‘creativity’ (the exception being Arabic).[193] The principle of linguistic relativity (i.e., that language can affect thought) suggests that the lack of an equivalent word for ‘creativity’ may affect the views of creativity among speakers of such languages. However, more research would be needed to establish this, and there is certainly no suggestion that this linguistic difference makes people any less (or more) creative; Africa has a rich heritage of creative pursuits such as music, art, and storytelling. Nevertheless, it is true that there has been very little research on creativity in Africa,[194] and there has also been very little research on creativity in Latin America.[195] Creativity has been more thoroughly researched in the northern hemisphere, but here again there are cultural differences, even between countries or groups of countries in close proximity. For example, in Scandinavian countries, creativity is seen as an individual attitude which helps in coping with life’s challenges,[196] while in Germany, creativity is seen more as a process that can be applied to help solve problems.[197]

Organizational creativity[edit]

Training meeting in an eco-design stainless steel company in Brazil. The leaders among other things wish to cheer and encourage the workers in order to achieve a higher level of creativity.

It has been the topic of various research studies to establish that organizational effectiveness depends on the creativity of the workforce to a large extent. For any given organization, measures of effectiveness vary, depending upon its mission, environmental context, nature of work, the product or service it produces, and customer demands. Thus, the first step in evaluating organizational effectiveness is to understand the organization itself – how it functions, how it is structured, and what it emphasizes.

Amabile[198] and Sullivan and Harper[199] argued that to enhance creativity in business, three components were needed:

- Expertise (technical, procedural and intellectual knowledge),

- Creative thinking skills (how flexibly and imaginatively people approach problems),

- and Motivation (especially intrinsic motivation).

There are two types of motivation:

- extrinsic motivation – external factors, for example threats of being fired or money as a reward,

- intrinsic motivation – comes from inside an individual, satisfaction, enjoyment of work, etc.

Six managerial practices to encourage motivation are:

- Challenge – matching people with the right assignments;

- Freedom – giving people autonomy choosing means to achieve goals;

- Resources – such as time, money, space, etc. There must be balance fit among resources and people;

- Work group features – diverse, supportive teams, where members share the excitement, willingness to help, and recognize each other’s talents;

- Supervisory encouragement – recognitions, cheering, praising;

- Organizational support – value emphasis, information sharing, collaboration.

Nonaka, who examined several successful Japanese companies, similarly saw creativity and knowledge creation as being important to the success of organizations.[200] In particular, he emphasized the role that tacit knowledge has to play in the creative process.

In business, originality is not enough. The idea must also be appropriate – useful and actionable.[198][201] Creative competitive intelligence is a new solution to solve this problem. According to Reijo Siltala it links creativity to innovation process and competitive intelligence to creative workers.

Creativity can be encouraged in people and professionals and in the workplace. It is essential for innovation, and is a factor affecting economic growth and businesses. In 2013, the sociologist Silvia Leal Martín, using the Innova 3DX method, suggested measuring the various parameters that encourage creativity and innovation: corporate culture, work environment, leadership and management, creativity, self-esteem and optimism, locus of control and learning orientation, motivation, and fear.[202]

Similarly, social psychologists, organizational scientists, and management scientists (who conduct extensive research on the factors that influence creativity and innovation in teams and organizations) have developed integrative theoretical models that emphasize the roles of team composition, team processes, and organizational culture. These theoretical models also emphasize the mutually reinforcing relationships between them in promoting innovation.[203][204][205][206]