Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks underlying principles, thoughts and beliefs.[1]

They play an important role in all aspects of cognition.[2][3] As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.[4]

In contemporary philosophy, there are at least three prevailing ways to understand what a concept is:[5]

- Concepts as mental representations, where concepts are entities that exist in the mind (mental objects)

- Concepts as abilities, where concepts are abilities peculiar to cognitive agents (mental states)

- Concepts as Fregean senses, where concepts are abstract objects, as opposed to mental objects and mental states

Concepts can be organized into a hierarchy, higher levels of which are termed «superordinate» and lower levels termed «subordinate». Additionally, there is the «basic» or «middle» level at which people will most readily categorize a concept.[6] For example, a basic-level concept would be «chair», with its superordinate, «furniture», and its subordinate, «easy chair».

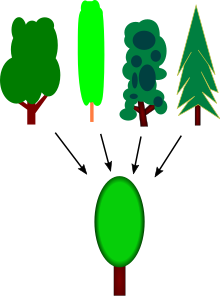

A representation of the concept of a tree. The four upper images of trees can be roughly quantified into an overall generalization of the idea of a tree, pictured in the lower image.

Concepts may be exact, or inexact.[7]

When the mind makes a generalization such as the concept of tree, it extracts similarities from numerous examples; the simplification enables higher-level thinking.

A concept is instantiated (reified) by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are things in the real world or other ideas.

Concepts are studied as components of human cognition in the cognitive science disciplines of linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, where an ongoing debate asks whether all cognition must occur through concepts. Concepts are regularly formalized in mathematics, computer science, databases and artificial intelligence. Examples of specific high-level conceptual classes in these fields include classes, schema or categories. In informal use the word concept often just means any idea.

Ontology of concepts[edit]

A central question in the study of concepts is the question of what they are. Philosophers construe this question as one about the ontology of concepts—what kind of things they are. The ontology of concepts determines the answer to other questions, such as how to integrate concepts into a wider theory of the mind, what functions are allowed or disallowed by a concept’s ontology, etc. There are two main views of the ontology of concepts: (1) Concepts are abstract objects, and (2) concepts are mental representations.[8]

Concepts as mental representations[edit]

The psychological view of concepts[edit]

Within the framework of the representational theory of mind, the structural position of concepts can be understood as follows: Concepts serve as the building blocks of what are called mental representations (colloquially understood as ideas in the mind). Mental representations, in turn, are the building blocks of what are called propositional attitudes (colloquially understood as the stances or perspectives we take towards ideas, be it «believing», «doubting», «wondering», «accepting», etc.). And these propositional attitudes, in turn, are the building blocks of our understanding of thoughts that populate everyday life, as well as folk psychology. In this way, we have an analysis that ties our common everyday understanding of thoughts down to the scientific and philosophical understanding of concepts.[9]

The physicalist view of concepts[edit]

In a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is a mental representation, which the brain uses to denote a class of things in the world. This is to say that it is literally, a symbol or group of symbols together made from the physical material of the brain.[10][11] Concepts are mental representations that allow us to draw appropriate inferences about the type of entities we encounter in our everyday lives.[11] Concepts do not encompass all mental representations, but are merely a subset of them.[10] The use of concepts is necessary to cognitive processes such as categorization, memory, decision making, learning, and inference.[12]

Concepts are thought to be stored in long term cortical memory,[13] in contrast to episodic memory of the particular objects and events which they abstract, which are stored in hippocampus. Evidence for this separation comes from hippocampal damaged patients such as patient HM. The abstraction from the day’s hippocampal events and objects into cortical concepts is often considered to be the computation underlying (some stages of) sleep and dreaming. Many people (beginning with Aristotle) report memories of dreams which appear to mix the day’s events with analogous or related historical concepts and memories, and suggest that they were being sorted or organized into more abstract concepts. («Sort» is itself another word for concept, and «sorting» thus means to organize into concepts.)

Concepts as abstract objects[edit]

The semantic view of concepts suggests that concepts are abstract objects. In this view, concepts are abstract objects of a category out of a human’s mind rather than some mental representations.[8]

There is debate as to the relationship between concepts and natural language.[5] However, it is necessary at least to begin by understanding that the concept «dog» is philosophically distinct from the things in the world grouped by this concept—or the reference class or extension.[10] Concepts that can be equated to a single word are called «lexical concepts».[5]

The study of concepts and conceptual structure falls into the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science.[11]

In the simplest terms, a concept is a name or label that regards or treats an abstraction as if it had concrete or material existence, such as a person, a place, or a thing. It may represent a natural object that exists in the real world like a tree, an animal, a stone, etc. It may also name an artificial (man-made) object like a chair, computer, house, etc. Abstract ideas and knowledge domains such as freedom, equality, science, happiness, etc., are also symbolized by concepts. It is important to realize that a concept is merely a symbol, a representation of the abstraction. The word is not to be mistaken for the thing. For example, the word «moon» (a concept) is not the large, bright, shape-changing object up in the sky, but only represents that celestial object. Concepts are created (named) to describe, explain and capture reality as it is known and understood.

A priori concepts[edit]

Kant maintained the view that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are twelve categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema. He held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result from abstraction «a posteriori concepts» (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1)

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are:

- comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness;

- reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally

- abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ …

In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.

— Logic, §6

Embodied content[edit]

In cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995; see conceptual blending). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato’s term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism, the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.[citation needed]

Realist universal concepts[edit]

Platonist views of the mind construe concepts as abstract objects.[14] Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say, this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato’s ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.[15]

Sense and reference[edit]

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status.[8]

Concepts in calculus[edit]

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Notable theories on the structure of concepts[edit]

Classical theory[edit]

The classical theory of concepts, also referred to as the empiricist theory of concepts,[10] is the oldest theory about the structure of concepts (it can be traced back to Aristotle[11]), and was prominently held until the 1970s.[11] The classical theory of concepts says that concepts have a definitional structure.[5] Adequate definitions of the kind required by this theory usually take the form of a list of features. These features must have two important qualities to provide a comprehensive definition.[11] Features entailed by the definition of a concept must be both necessary and sufficient for membership in the class of things covered by a particular concept.[11] A feature is considered necessary if every member of the denoted class has that feature. A feature is considered sufficient if something has all the parts required by the definition.[11] For example, the classic example bachelor is said to be defined by unmarried and man.[5] An entity is a bachelor (by this definition) if and only if it is both unmarried and a man. To check whether something is a member of the class, you compare its qualities to the features in the definition.[10] Another key part of this theory is that it obeys the law of the excluded middle, which means that there are no partial members of a class, you are either in or out.[11]

The classical theory persisted for so long unquestioned because it seemed intuitively correct and has great explanatory power. It can explain how concepts would be acquired, how we use them to categorize and how we use the structure of a concept to determine its referent class.[5] In fact, for many years it was one of the major activities in philosophy—concept analysis.[5] Concept analysis is the act of trying to articulate the necessary and sufficient conditions for the membership in the referent class of a concept.[citation needed] For example, Shoemaker’s classic «Time Without Change» explored whether the concept of the flow of time can include flows where no changes take place, though change is usually taken as a definition of time.[citation needed]

Arguments against the classical theory[edit]

Given that most later theories of concepts were born out of the rejection of some or all of the classical theory,[14] it seems appropriate to give an account of what might be wrong with this theory. In the 20th century, philosophers such as Wittgenstein and Rosch argued against the classical theory. There are six primary arguments[14] summarized as follows:

- It seems that there simply are no definitions—especially those based in sensory primitive concepts.[14]

- It seems as though there can be cases where our ignorance or error about a class means that we either don’t know the definition of a concept, or have incorrect notions about what a definition of a particular concept might entail.[14]

- Quine’s argument against analyticity in Two Dogmas of Empiricism also holds as an argument against definitions.[14]

- Some concepts have fuzzy membership. There are items for which it is vague whether or not they fall into (or out of) a particular referent class. This is not possible in the classical theory as everything has equal and full membership.[14]

- Experiments and research showed that assumptions of well defined concepts and categories might not be correct. Researcher Hampton[16]asked participants to differentiate whether items were in different categories. Hampton did not conclude that items were either clear and absolute members or non-members. Instead, Hampton found that some items were barely considered category members and others that were barely non-members. For example, participants considered sinks as barely members of kitchen utensil category, while sponges were considered barely non-members, with much disagreement among participants of the study. If concepts and categories were very well defined, such cases should be rare. Since then, many researches have discovered borderline members that are not clearly in or out of a category of concept.

- Rosch found typicality effects which cannot be explained by the classical theory of concepts, these sparked the prototype theory.[14] See below.

- Psychological experiments show no evidence for our using concepts as strict definitions.[14]

Prototype theory[edit]

Prototype theory came out of problems with the classical view of conceptual structure.[5] Prototype theory says that concepts specify properties that members of a class tend to possess, rather than must possess.[14] Wittgenstein, Rosch, Mervis, Berlin, Anglin, and Posner are a few of the key proponents and creators of this theory.[14][17] Wittgenstein describes the relationship between members of a class as family resemblances. There are not necessarily any necessary conditions for membership; a dog can still be a dog with only three legs.[11] This view is particularly supported by psychological experimental evidence for prototypicality effects.[11] Participants willingly and consistently rate objects in categories like ‘vegetable’ or ‘furniture’ as more or less typical of that class.[11][17] It seems that our categories are fuzzy psychologically, and so this structure has explanatory power.[11] We can judge an item’s membership of the referent class of a concept by comparing it to the typical member—the most central member of the concept. If it is similar enough in the relevant ways, it will be cognitively admitted as a member of the relevant class of entities.[11] Rosch suggests that every category is represented by a central exemplar which embodies all or the maximum possible number of features of a given category.[11] Lech, Gunturkun, and Suchan explain that categorization involves many areas of the brain. Some of these are: visual association areas, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and temporal lobe.

The Prototype perspective is proposed as an alternative view to the Classical approach. While the Classical theory requires an all-or-nothing membership in a group, prototypes allow for more fuzzy boundaries and are characterized by attributes.[18] Lakoff stresses that experience and cognition are critical to the function of language, and Labov’s experiment found that the function that an artifact contributed to what people categorized it as.[18] For example, a container holding mashed potatoes versus tea swayed people toward classifying them as a bowl and a cup, respectively. This experiment also illuminated the optimal dimensions of what the prototype for «cup» is.[18]

Prototypes also deal with the essence of things and to what extent they belong to a category. There have been a number of experiments dealing with questionnaires asking participants to rate something according to the extent to which it belongs to a category.[18] This question is contradictory to the Classical Theory because something is either a member of a category or is not.[18] This type of problem is paralleled in other areas of linguistics such as phonology, with an illogical question such as «is /i/ or /o/ a better vowel?» The Classical approach and Aristotelian categories may be a better descriptor in some cases.[18]

Theory-theory[edit]

Theory-theory is a reaction to the previous two theories and develops them further.[11] This theory postulates that categorization by concepts is something like scientific theorizing.[5] Concepts are not learned in isolation, but rather are learned as a part of our experiences with the world around us.[11] In this sense, concepts’ structure relies on their relationships to other concepts as mandated by a particular mental theory about the state of the world.[14] How this is supposed to work is a little less clear than in the previous two theories, but is still a prominent and notable theory.[14] This is supposed to explain some of the issues of ignorance and error that come up in prototype and classical theories as concepts that are structured around each other seem to account for errors such as whale as a fish (this misconception came from an incorrect theory about what a whale is like, combining with our theory of what a fish is).[14] When we learn that a whale is not a fish, we are recognizing that whales don’t in fact fit the theory we had about what makes something a fish. Theory-theory also postulates that people’s theories about the world are what inform their conceptual knowledge of the world. Therefore, analysing people’s theories can offer insights into their concepts. In this sense, «theory» means an individual’s mental explanation rather than scientific fact. This theory criticizes classical and prototype theory as relying too much on similarities and using them as a sufficient constraint. It suggests that theories or mental understandings contribute more to what has membership to a group rather than weighted similarities, and a cohesive category is formed more by what makes sense to the perceiver. Weights assigned to features have shown to fluctuate and vary depending on context and experimental task demonstrated by Tversky. For this reason, similarities between members may be collateral rather than causal.[19]

Ideasthesia[edit]

According to the theory of ideasthesia (or «sensing concepts»), activation of a concept may be the main mechanism responsible for the creation of phenomenal experiences. Therefore, understanding how the brain processes concepts may be central to solving the mystery of how conscious experiences (or qualia) emerge within a physical system e.g., the sourness of the sour taste of lemon.[20] This question is also known as the hard problem of consciousness.[21][22] Research on ideasthesia emerged from research on synesthesia where it was noted that a synesthetic experience requires first an activation of a concept of the inducer.[23] Later research expanded these results into everyday perception.[24]

There is a lot of discussion on the most effective theory in concepts. Another theory is semantic pointers, which use perceptual and motor representations and these representations are like symbols.[25]

Etymology[edit]

The term «concept» is traced back to 1554–60 (Latin conceptum – «something conceived»).[26]

See also[edit]

- Abstraction

- Categorization

- Class (philosophy)

- Conceptualism

- Concept and object

- Concept map

- Conceptual blending

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual history

- Conceptual model

- Conversation theory

- Definitionism

- Formal concept analysis

- Fuzzy concept

- Hypostatic abstraction

- Idea

- Ideasthesia

- Noesis

- Notion (philosophy)

- Object (philosophy)

- Process of concept formation

- Schema (Kant)

- Intuitive statistics

References[edit]

- ^ Goguen, Joseph (2005). «What is a Concept?». Conceptual Structures: Common Semantics for Sharing Knowledge. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3596. pp. 52–77. doi:10.1007/11524564_4. ISBN 978-3-540-27783-5.

- ^ Chapter 1 of Laurence and Margolis’ book called Concepts: Core Readings. ISBN 9780262631938

- ^ Carey, S. (1991). Knowledge Acquisition: Enrichment or Conceptual Change? In S. Carey and R. Gelman (Eds.), The Epigenesis of Mind: Essays on Biology and Cognition (pp. 257–291). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- ^ «Cognitive Science | Brain and Cognitive Sciences».

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eric Margolis; Stephen Lawrence. «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab at Stanford University. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Joseph Goguen «»The logic of inexact concepts», Synthese 19 (3/4): 325–373 (1969).

- ^ a b c Margolis, Eric; Laurence, Stephen (2007). «The Ontology of Concepts—Abstract Objects or Mental Representations?». Noûs. 41 (4): 561–593. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.9995. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0068.2007.00663.x.

- ^ Jerry Fodor, Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong

- ^ a b c d e Carey, Susan (2009). The Origin of Concepts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536763-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Murphy, Gregory (2002). The Big Book of Concepts. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 978-0-262-13409-5.

- ^ McCarthy, Gabby (2018) «Introduction to Metaphysics». pg. 35

- ^ Eysenck. M. W., (2012) Fundamentals of Cognition (2nd) Psychology Taylor & Francis

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Stephen Lawrence; Eric Margolis (1999). Concepts and Cognitive Science. in Concepts: Core Readings: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 3–83. ISBN 978-0-262-13353-1.

- ^ ‘Godel’s Rationalism’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Hampton, J.A. (1979). «Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory». Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 18 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(79)90246-9.

- ^ a b Brown, Roger (1978). A New Paradigm of Reference. Academic Press Inc. pp. 159–166. ISBN 978-0-12-497750-1.

- ^ a b c d e f TAYLOR, John R. (1989). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes In Linguistic Theory.

- ^ Murphy, Gregory L.; Medin, Douglas L. (1985). «The role of theories in conceptual coherence». Psychological Review. 92 (3): 289–316. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.92.3.289. ISSN 0033-295X. PMID 4023146.

- ^ Mroczko-Wä…Sowicz, Aleksandra; Nikoliä‡, Danko (2014). «Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia». Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 509. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00509. PMC 4137691. PMID 25191239.

- ^ Stevan Harnad (1995). Why and How We Are Not Zombies. Journal of Consciousness Studies 1: 164–167.

- ^ David Chalmers (1995). Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2 (3): 200–219.

- ^ Nikolić, D. (2009) Is synaesthesia actually ideaesthesia? An inquiry into the nature of the phenomenon. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Synaesthesia, Science & Art, Granada, Spain, April 26–29, 2009.

- ^ Gómez Milán, E., Iborra, O., de Córdoba, M.J., Juárez-Ramos V., Rodríguez Artacho, M.A., Rubio, J.L. (2013) The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia. The Journal of Consciousness Studies. 20(1–2): pp. 84–102.

- ^ Blouw, Peter; Solodkin, Eugene; Thagard, Paul; Eliasmith, Chris (2016). «Concepts as Semantic Pointers: A Framework and Computational Model». Cognitive Science. 40 (5): 1128–1162. doi:10.1111/cogs.12265. PMID 26235459.

- ^ «Homework Help and Textbook Solutions | bartleby». Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2011-11-25.The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition.

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, S. L., Gleitman, L. R., & Gleitman, H. (1999). what some concepts might not be. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, Concepts (pp. 225–261). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Carey, S. (1999). knowledge acquisition: enrichment or conceptual change? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 459–489). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, J. A., Garrett, M. F., Walker, E. C., & Parkes, C. H. (1999). against definitions. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 491–513). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Fodor, Jerry; Lepore, Ernest (1996). «The red herring and the pet fish: Why concepts still can’t be prototypes». Cognition. 58 (2): 253–270. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(95)00694-X. PMID 8820389. S2CID 15356470.

- Hume, D. (1739). book one part one: of the understanding of ideas, their origin, composition, connexion, abstraction etc. In D. Hume, a treatise of human nature. England.

- Murphy, G. (2004). Chapter 2. In G. Murphy, a big book of concepts (pp. 11 – 41). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Murphy, G., & Medin, D. (1999). the role of theories in conceptual coherence. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 425–459). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Prinz, Jesse J. (2002). Furnishing the Mind. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3169.001.0001. ISBN 9780262281935.

- Putnam, H. (1999). is semantics possible? In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 177–189). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Quine, W. (1999). two dogmas of empiricism. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 153–171). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- Rey, G. (1999). Concepts and Stereotypes. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 279–301). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Rosch, E. (1977). Classification of real-world objects: Origins and representations in cognition. In P. Johnson-Laird, & P. Wason, Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science (pp. 212–223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosch, E. (1999). Principles of Categorization. In E. Margolis, & S. Laurence (Eds.), Concepts: Core Readings (pp. 189–206). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Schneider, Susan (2011). «Concepts: A Pragmatist Theory». The Language of Thought. pp. 159–182. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262015578.003.0071. ISBN 9780262015578.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1999). philosophical investigations: sections 65–78. In E. Margolis, & S. Lawrence, concepts: core readings (pp. 171–175). Massachusetts: MIT press.

- The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development, Carl Benjamin Boyer, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- The Writings of William James, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-39188-4

- Logic, Immanuel Kant, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- A System of Logic, John Stuart Mill, University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume I, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience, H. J. Paton, London: Allen & Unwin, 1936

- Conceptual Integration Networks. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, 1998. Cognitive Science. Volume 22, number 2 (April–June 1998), pp. 133–187.

- The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1982, ISBN 0-14-015062-5

- Stephen Laurence and Eric Margolis «Concepts and Cognitive Science». In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press pp. 3–81, 1999.

- Hjørland, Birger (2009). «Concept theory». Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 60 (8): 1519–1536. doi:10.1002/asi.21082.

- Georgij Yu. Somov (2010). Concepts and Senses in Visual Art: Through the example of analysis of some works by Bruegel the Elder. Semiotica 182 (1/4), 475–506.

- Daltrozzo J, Vion-Dury J, Schön D. (2010). Music and Concepts. Horizons in Neuroscience Research 4: 157–167.

External links[edit]

Look up concept in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Concept at PhilPapers

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Concepts». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Concept at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- «Concept». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Theory–Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- «Classical Theory of Concepts». Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blending and Conceptual Integration

- Concepts. A Critical Approach, by Andy Blunden

- Conceptual Science and Mathematical Permutations

- Concept Mobiles Latest concepts

- v:Conceptualize: A Wikiversity Learning Project

- Concept simultaneously translated in several languages and meanings

- TED-Ed Lesson on ideasthesia (sensing concepts)

A concept is a constituent of thought or generalized idea, that designates common properties and characteristics abstracted from a number of instances. While ideas, perceptions, and «representations» have psychological implications, concepts have logical implications.

Human beings understand the world by applying concepts and expressing them with language. Theories of concepts are thus closely tied to the philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, cognitive science, and psychology, as well as ontology and epistemology.

Overview

A vast array of accounts attempt to explain the nature of concepts. According to classical accounts, a concept denotes all of the entities, phenomena, and/or relations in a given category or class by using definitions. Concepts are abstract in that they omit the differences of the things in their extension, treating the members of the extension as if they were identical. Classical concepts are universal in that they apply equally to everything in their extension. Concepts are also the basic elements of propositions, much the same way a word is the basic semantic element of a sentence. Unlike perceptions, which are particular images of individual objects, concepts cannot be visualized. Because they are not themselves individual perceptions, concepts are discursive and result from reason.

Concepts are important in understanding reality. Generally speaking, concepts are taken to be:

- Acquired dispositions to recognize perceived objects as being of this kind or of that ontological kind

- To understand what this kind or that kind of object is like, and consequently

- To perceive a number of perceived particulars as being the same in kind and to discriminate between them and other sensible particulars that are different in kind

In addition, concepts are acquired dispositions to understand what certain kinds of objects are like both when the objects, though perceptible, are not actually perceived, and also when they are not perceptible at all, as is the case with all the conceptual constructs people employ in physics, mathematics, and metaphysics. The impetus to have a theory of concepts that is ontologically useful has been so strong that it has pushed forward accounts that understand a concept to have a deep connection with reality.

On some accounts, there may be agents (perhaps some animals) which don’t think about, but rather use relatively basic concepts (such as demonstrative and perceptual concepts for things in their perceptual field), even though it is generally assumed that they do not think in symbols. On other accounts, mastery of symbolic thought (in particular, language) is a prerequisite for conceptual thought.[1]

Concepts are bearers of meaning, as opposed to agents of meaning. A single concept can be expressed by any number of languages. The concept of DOG can be expressed as dog in English, Hund in German, as chien in French, and perro in Spanish. The fact that concepts are in some sense independent of language makes translation possible—words in various languages have identical meaning, because they express one and the same concept.

A term labels or designates concepts. Several partly or fully distinct concepts may share the same term. These different concepts are easily confused by, mistakenly, being used interchangeably, constituting a fallacy. Also, the concepts of term and concept are often confused, although the two are not the same.

The acquisition of concepts is studied in machine learning as supervised classification and unsupervised classification, and in psychology and cognitive science as concept learning and category formation. In the philosophy of Kant, any purely empirical theory dealing with the acquisition of concepts is referred to as a noogony.

Origin and acquisition of concepts

A posteriori abstractions

John Locke’s description of a general idea corresponds to a description of a concept. According to Locke, a general idea is created by abstracting, drawing away, or removing the common characteristic or characteristics from several particular ideas. This common characteristic is that which is similar to all of the different individuals. For example, the abstract general idea or concept that is designated by the word «red» is that characteristic which is common to apples, cherries, and blood. The abstract general idea or concept that is signified by the word «dog» is the collection of those characteristics which are common to Airedales, Collies, and Chihuahuas.

In the same tradition as Locke, John Stuart Mill stated that general conceptions are formed through abstraction. A general conception is the common element among the many images of members of a class. «…[W]hen we form a set of phenomena into a class, that is, when we compare them with one another to ascertain in what they agree, some general conception is implied in this mental operation» (A System of Logic, Book IV, Ch. II). Mill did not believe that concepts exist in the mind before the act of abstraction. «It is not a law of our intellect, that, in comparing things with each other and taking note of their agreement, we merely recognize as realized in the outward world something that we already had in our minds. The conception originally found its way to us as the result of such a comparison. It was obtained (in metaphysical phrase) by abstraction from individual things» (Ibid.).

For Schopenhauer, empirical concepts «…are mere abstractions from what is known through intuitive perception, and they have arisen from our arbitrarily thinking away or dropping of some qualities and our retention of others» (Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. I, «Sketch of a History of the Ideal and the Real»). In his On the Will in Nature, «Physiology and Pathology,» Schopenhauer said that a concept is «drawn off from previous images … by putting off their differences. This concept is then no longer intuitively perceptible, but is denoted and fixed merely by words.» Nietzsche, who was heavily influenced by Schopenhauer, wrote, «Every concept originates through our equating what is unequal. No leaf ever wholly equals another, and the concept ‘leaf’ is formed through an arbitrary abstraction from these individual differences, through forgetting the distinctions… » («On Truth and Lie in an Extra—Moral Sense,» The Portable Nietzsche, p. 46).

By contrast to the above philosophers, Immanuel Kant held that the account of the concept as an abstraction of experience is only partly correct. He called those concepts that result of abstraction «a posteriori concepts» (meaning concepts that arise out of experience). An empirical or an a posteriori concept is a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects (Logic, I, 1., §1, Note 1).

A concept is a common feature or characteristic. Kant investigated the way that empirical a posteriori concepts are created.

The logical acts of the understanding by which concepts are generated as to their form are: (1.) comparison, i.e., the likening of mental images to one another in relation to the unity of consciousness; (2.) reflection, i.e., the going back over different mental images, how they can be comprehended in one consciousness; and finally (3.) abstraction or the segregation of everything else by which the mental images differ. … In order to make our mental images into concepts, one must thus be able to compare, reflect, and abstract, for these three logical operations of the understanding are essential and general conditions of generating any concept whatever. For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree (Logic, §6).

Kant’s description of the making of a concept has been paraphrased as «… to conceive is essentially to think in abstraction what is common to a plurality of possible instances… » (H.J. Paton, Kant’s Metaphysics of Experience, I, 250). In his discussion of Kant, Christopher Janaway wrote: «… generic concepts are formed by abstraction from more than one species.»[2]

A priori concepts

Kant declared that human minds possess pure or a priori concepts. Instead of being abstracted from individual perceptions, like empirical concepts, they originate in the mind itself. He called these concepts categories, in the sense of the word that means predicate, attribute, characteristic, or quality. But these pure categories are predicates of things in general, not of a particular thing. According to Kant, there are 12 categories that constitute the understanding of phenomenal objects. Each category is that one predicate which is common to multiple empirical concepts. In order to explain how an a priori concept can relate to individual phenomena, in a manner analogous to an a posteriori concept, Kant employed the technical concept of the schema.

Conceptual structure

It seems intuitively obvious that concepts must have some kind of structure. Up until recently, the dominant view of conceptual structure was a containment model, associated with the classical view of concepts. According to this model, a concept is endowed with certain necessary and sufficient conditions in their description which unequivocally determine an extension. The containment model allows for no degrees; a thing is either in, or out, of the concept’s extension. By contrast, the inferential model understands conceptual structure to be determined in a graded manner, according to the tendency of the concept to be used in certain kinds of inferences. As a result, concepts do not have a kind of structure that is in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions; all conditions are contingent (Margolis: 5).

However, some theorists claim that primitive concepts lack any structure at all. For instance, Jerry Fodor presents his Asymmetric Dependence Theory as a way of showing how a primitive concept’s content is determined by a reliable relationship between the information in mental contents and the world. These sorts of claims are referred to as «atomistic,» because the primitive concept is treated as if it were a genuine atom.

Conceptual content

Content as pragmatic role

A concept may be abstracted from several perceptions, but that is only its origin. In regard to its meaning or its truth, William James proposed his Pragmatic Rule. This rule states that the meaning of a concept may always be found in some particular difference in the course of human experience which its being true will make (Some Problems of Philosophy, «Percept and Concept—The Import of Concepts»). In order to understand the meaning of the concept and to discuss its importance, a concept may be tested by asking, «What sensible difference to anybody will its truth make?» There is only one criterion of a concept’s meaning and only one test of its truth. That criterion or test is its consequences for human behavior.

In this way, James bypassed the controversy between rationalists and empiricists regarding the origin of concepts. Instead of solving their dispute, he ignored it. The rationalists had asserted that concepts are a revelation of Reason. Concepts are a glimpse of a different world, one which contains timeless truths in areas such as logic, mathematics, ethics, and aesthetics. By pure thought, humans can discover the relations that really exist among the parts of that divine world. On the other hand, the empiricists claimed that concepts were merely a distillation or abstraction from perceptions of the world of experience. Therefore, the significance of concepts depends solely on the perceptions that are its references. James’ Pragmatic Rule does not connect the meaning of a concept with its origin. Instead, it relates the meaning to a concept’s purpose, that is, its function, use, or result.

Embodied content

In Cognitive linguistics, abstract concepts are transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience. The mechanism of transformation is structural mapping, in which properties of two or more source domains are selectively mapped onto a blended space (Fauconnier & Turner, 1995). A common class of blends are metaphors. This theory contrasts with the rationalist view that concepts are perceptions (or recollections, in Plato’s term) of an independently existing world of ideas, in that it denies the existence of any such realm. It also contrasts with the empiricist view that concepts are abstract generalizations of individual experiences, because the contingent and bodily experience is preserved in a concept, and not abstracted away. While the perspective is compatible with Jamesian pragmatism (above), the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a distinct contribution to the problem of concept formation.

Philosophical implications

Concepts and metaphilosophy

A long and well-established tradition in philosophy posits that philosophy itself is nothing more than conceptual analysis. This view has its proponents in contemporary literature as well as historical. According to Deleuze and Guattari’s What Is Philosophy? (1991), philosophy is the activity of creating concepts. This creative activity differs from previous definitions of philosophy as simple reasoning, communication, or contemplation of Universals. Concepts are specific to philosophy: Science has got «percepts,» and art «affects.» A concept is always signed: Thus, Descartes’ Cogito or Kant’s «transcendental.» It is a singularity, not a universal, and connects itself with others concepts, on a «plane of immanence» traced by a particular philosophy. Concepts can jump from one plane of immanence to another, combining with other concepts and therefore engaging in a «becoming-Other.»

Concepts in epistemology

Concepts are vital to the development of scientific knowledge. For example, it would be difficult to imagine physics without concepts like: Energy, force, or acceleration. Concepts help to integrate apparently unrelated observations and phenomena into viable hypothesis and theories, the basic ingredients of science. The concept map is a tool that is used to help researchers visualize the inter-relationships between various concepts.

Ontology of concepts

Although the mainstream literature in cognitive science regards the concept as a kind of mental particular, it has been suggested by some theorists that concepts are real things (Margolis: 8). In the most radical form, the realist about concepts attempts to show that the supposedly mental processes are not mental at all; rather, they are abstract entities, which are just as real as any mundane object.

Plato was the starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts. By his view, concepts (and ideas in general) are innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that laid behind the veil of the physical world. In this way, universals were explained as transcendent objects. Needless to say, this form of realism was tied deeply with Plato’s ontological projects. This remark on Plato is not of merely historical interest. For example, the view that numbers are Platonic objects was revived by Kurt Godel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.

Gottlob Frege, founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, famously argued for the analysis of language in terms of sense and reference. For him, the sense of an expression in language describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented. Since many commentators view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept, and Frege regards senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it seems to follow that we may understand concepts as the manner in which we grasp the world. Accordingly, concepts (as senses) have an ontological status (Morgolis: 7)

According to Carl Benjamin Boyer, in the introduction to his The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development, concepts in calculus do not refer to perceptions. As long as the concepts are useful and mutually compatible, they are accepted on their own. For example, the concepts of the derivative and the integral are not considered to refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of the external world of experience. Neither are they related in any way to mysterious limits in which quantities are on the verge of nascence or evanescence, that is, coming into or going out of appearance or existence. The abstract concepts are now considered to be totally autonomous, even though they originated from the process of abstracting or taking away qualities from perceptions until only the common, essential attributes remained.

Notes

- ↑ Antonio R. Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (Avon, 1994), p. 106.

- ↑ Christopher Janaway, Self and World in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy (Oxford, 2003). ISBN 0-19-825003-7

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin. The History of Calculus and its Conceptual Development. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-60509-4

- Damasio, Antonio R. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Avon, 1994.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. What Is Philosophy? European Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. ISBN 0231079885

- Fauconnier, Gilles and Mark Turner. «Conceptual Integration Networks.» Cognitive Science. 22, 2 (April-June 1998): 133-187.

- Janaway, Christopher. Self and World in Schopenhauer’s Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004. ISBN 0198249691

- Kant, Immanuel. Logic. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25650-2

- Laurence, Stephen and Eric Margolis. «Concepts and Cognitive Science» . In Concepts: Core Readings, MIT Press, pp. 3-81, 1999. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- Mill, John Stuart. A System of Logic, University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1-4102-0252-6

- Nietzsche, Friedrich and Walter Kaufmann. The Portable Nietzsche. New York: Penguin, 1976. ISBN 0140150625

- Paton, H.J. Kant’s Metaphysic of Experience. London: Allen & Unwin, 1936.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur. Parerga and Paralipomena. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824508-4

- The Writings of William James. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39188-4

External links

All links retrieved March 17, 2017.

- E. Margolis and S. Lawrence, Concepts, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Concepts, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Concept history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of «Concept»

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Noun

She is familiar with basic concepts of psychology.

a concept borrowed from computer programming

Recent Examples on the Web

Parallel Worlds The concept of a multiverse—universes like our own but also slightly different—comes to us from two places in theoretical physics.

—

Applying pen to paper, the mathematicians constructed the concept of cellular automata, dynamical entities made up of shaded or unshaded cells skipping across a two-dimensional grid.

—

The concept features two rare water healing experiences – Janzu and Aquatic Tibetan Sound Healing, which promotes a deeper sense of calm and connection to self.

—

What’s new at Kings Island this year?How about a new restaurant and executive chef While Wildweed will have pasta on its menu, Jackman said in a release that the concept is not meant to be an Italian restaurant.

—

After she was elected to her first term as president in 2016, Tsai declined to endorse the concept that Taiwan and the mainland are part of one China, prompting Beijing to cut diplomatic contact with her.

—

The concept of that suddenly seemed really fun.

—

The rest of the world, meanwhile, has embraced the concept, with the bidet evolving into myriad forms.

—

Live the jamu life: Central to the Indonesian concept of jamu is mindfulness.

—

Folk hopes the multi-concept space can operate as a hub for the Paddington community.

—

The project is planned to go before the planning commission on Oct. 18 for a pre-concept review.

—

The approach is no different for the team behind Oceanside’s just-opened The Lab Collaborative (TLC), a multi-concept food and drink destination that opened Jan. 5 in downtown Oceanside.

—

From March 25-27, Frame, a multi-concept restaurant in Hazel Park, will host Slavic Solidarity, an immersive dinner experience, featuring five courses of Ukrainian staples.

—

The Supper Club is the final piece of the 400-seat, three-story, multi-concept Twelve Thirty Club to open.

—

The vast, multi-concept Italian dining destination closed in 2018, one of many restaurants that had tried and failed in the neighborhood over the past decade.

—

This pre-concept-of-war GEM has somehow STILL never been lived in!

—

Concept art showed a mystical, face-having tree looming over a parking lot full of ordinary looking sedans.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘concept.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

an elaborated concept

a general inclusive concept

a general concept that marks divisions or coordinations in a conceptual scheme

a principle or condition that customarily governs behavior

a construct whereby objects or individuals can be distinguished

a concept or idea not associated with any specific instance

the concept that something has a magnitude and can be represented in mathematical expressions by a constant or a variable

one of the portions into which something is regarded as divided and which together constitute a whole

all of something including all its component elements or parts

a rule or body of rules of conduct inherent in human nature and essential to or binding upon human society

a generalization that describes recurring facts or events in nature

a concept that is expressed by a word (in some particular language)

a tentative insight into the natural world; a concept that is not yet verified but that if true would explain certain facts or phenomena

a concept whose truth can be proved

(linguistics) a rule describing (or prescribing) a linguistic practice

one of the ten divisions into which bowling is divided

an abstract idea of that which is due to a person or governmental body by law or tradition or nature

a way of conceiving something

a traditional notion that is obstinately held although it is unreasonable

a category of things distinguished by some common characteristic or quality

a specific (often simplistic) category

category name

a general category of things; used in the expression `in the way of’

a principle that limits the extent of something

a rule or principle that provides guidance to appropriate behavior

a rule that when literal compliance is impossible the intention of a donor or testator should be carried out as nearly as possible

a rule that is adequate to permit work to be done

a characteristic property that defines the apparent individual nature of something

a prominent attribute or aspect of something

(linguistics) a distinctive characteristic of a linguistic unit that serves to distinguish it from other units of the same kind

something that is conceived or that exists independently and not in relation to other things; something that does not depend on anything else and is beyond human control; something that is not relative

a personified abstraction that teaches

a special abstraction

a discrete amount of something that is analogous to the quantities in quantum theory

any distinct quantity contained in a polynomial

a quantity expressed as a number

a quantity upon which a mathematical operation is performed

a quantity that can assume any of a set of values

a quantity that does not vary

a quantity (such as the mean or variance) that characterizes a statistical population and that can be estimated by calculations from sample data

a quantity obtained by multiplication

a quantity obtained by the addition of a group of numbers

one of the quantities in a mathematical proportion

the first part or section of something

an intermediate part or section

a final part or section

the most enjoyable part of a given experience

an abstract part of something

a single undivided whole

a whole formed by a union of two or more elements or parts

a conceptual whole made up of complicated and related parts

a law that is believed to come directly from God

a basic truth or law or assumption

(neurophysiology) a nerve impulse resulting from a weak stimulus is just as strong as a nerve impulse resulting from a strong stimulus

a rule or law concerning a natural phenomenon or the function of a complex system

(hydrostatics) the apparent loss in weight of a body immersed in a fluid is equal to the weight of the displaced fluid

the principle that equal volumes of all gases (given the same temperature and pressure) contain equal numbers of molecules

(statistics) law stating that a large number of items taken at random from a population will (on the average) have the population statistics

a law used by auditors to identify fictitious populations of numbers; applies to any population of numbers derived from other numbers

(physics) statistical law obeyed by a system of particles whose wave function is not changed when two particles are interchanged (the Pauli exclusion principle does not apply)

the pressure of an ideal gas at constant temperature varies inversely with the volume

a fundamental principle of electrostatics; the force of attraction or repulsion between two charged particles is directly proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the distance between them; principle also holds for magnetic poles

(chemistry and physics) law stating that the pressure exerted by a mixture of gases equals the sum of the partial pressures of the gases in the mixture; the pressure of a gas in a mixture equals the pressure it would exert if it occupied the same volume alone at the same temperature

(chemistry) the total energy in an assembly of molecules is not distributed equally but is distributed around an average value according to a statistical distribution

(chemistry) the principle that (at chemical equilibrium) in a reversible reaction the ratio of the rate of the forward reaction to the rate of the reverse reaction is a constant for that reaction

(psychophysics) the concept that the magnitude of a subjective sensation increases proportional to the logarithm of the stimulus intensity; based on early work by E. H. Weber

(physics) law obeyed by a systems of particles whose wave function changes when two particles are interchanged (the Pauli exclusion principle applies)

(physics) the density of an ideal gas at constant pressure varies inversely with the temperature

(chemistry) law formulated by the English chemist William Henry; the amount of a gas that will be absorbed by water increases as the gas pressure increases

(physics) the principle that (within the elastic limit) the stress applied to a solid is proportional to the strain produced

(astronomy) the generalization that the speed of recession of distant galaxies (the red shift) is proportional to their distance from the observer

(astronomy) one of three empirical laws of planetary motion stated by Johannes Kepler

(physics) two laws governing electric networks in which steady currents flow: the sum of all the currents at a point is zero and the sum of the voltage gains and drops around any closed circuit is zero

a law affirming that in the long run probabilities will determine performance

(chemistry) law stating that every pure substance always contains the same elements combined in the same proportions by weight

a law affirming that to continue after a certain level of performance has been reached will result in a decline in effectiveness

(psychology) the principle that behaviors are selected by their consequences; behavior having good consequences tends to be repeated whereas behavior that leads to bad consequences is not repeated

(chemistry) law stating that the proportions in which two elements separately combine with a third element are also the proportions in which they combine together

(physics) the law that states any two bodies attract each other with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them

(chemistry) law stating that when two elements can combine to form more than one compound the amounts of one of them that combines with a fixed amount of the other will exhibit a simple multiple relation

(chemistry) the law that states the following principle: the rate of a chemical reaction is directly proportional to the molecular concentrations of the reacting substances

(physics) a law governing the relations between states of energy in a closed system

(genetics) one of two principles of heredity formulated by Gregor Mendel on the basis of his experiments with plants; the principles were limited and modified by subsequent genetic research

one of three basic laws of classical mechanics

electric current is directly proportional to voltage and inversely proportional to resistance; I = E/R

pressure applied anywhere to a body of fluid causes a force to be transmitted equally in all directions; the force acts at right angles to any surface in contact with the fluid

no two electrons or protons or neutrons in a given system can be in states characterized by the same set of quantum numbers

(chemistry) the principle that chemical properties of the elements are periodic functions of their atomic numbers

(physics) the basis of quantum theory; the energy of electromagnetic waves is contained in indivisible quanta that have to be radiated or absorbed as a whole; the magnitude is proportional to frequency where the constant of proportionality is given by Planck’s constant

(physics) an equation that expresses the distribution of energy in the radiated spectrum of an ideal black body

a hypothetical possibility, circumstance, statement, proposal, situation, etc.

the physically discrete element that Darwin proposed as responsible for heredity

a hypothetical description of a complex entity or process

a hypothesis that has been formed by speculating or conjecturing (usually with little hard evidence)

a hypothesis that is taken for granted

(physics) a universal law that states that the laws of mechanics are not affected by a uniform rectilinear motion of the system of coordinates to which they are referred

(psychophysics) the concept that the magnitude of a subjective sensation increases proportional to a power of the stimulus intensity

(psychophysics) the concept that a just-noticeable difference in a stimulus is proportional to the magnitude of the original stimulus

(mathematics) a quantity expressed as a sum or difference of two terms; a polynomial with two terms

a theory that social and cultural events are determined by history

a law describing sound changes in the history of a language

(linguistics) a grammatical rule (or other linguistic feature) that is found in all languages

a linguistic rule for the syntax of grammatical utterances

a linguistic rule for the formation of words

(polo) one of six divisions into which a polo match is divided

(baseball) one of nine divisions of play during which each team has a turn at bat

(tennis) a division of play during which one player serves

(sports) a division during which one team is on the offensive

the first division into which the play of a game is divided

the second division into which the play of a game is divided

the final division into which the play of a game is divided

one of two divisions into which some games or performances are divided: the two divisions are separated by an interval

(ice hockey) one of three divisions into which play is divided in hockey games

(football, professional basketball) one of four divisions into which some games are divided

(cricket) the division of play during which six balls are bowled at the batsman by one player from the other team from the same end of the pitch

(mathematics) a quantity or variable that, when fed into a function, results in a single output

(mathematics) the result or solution of a function that is associated with a single input

Britannica Dictionary definition of CONCEPT

[count]

:

an idea of what something is or how it works

-

She is familiar with basic concepts of psychology.

-

not a new concept

-

a concept borrowed from computer programming

-

She seems to be a little unclear on the concept of good manners. [=she seems not to understand what good manners are]

Britannica Dictionary definition of CONCEPT

always used before a noun

1

:

organized around a main idea or theme

-

a concept album [=a collection of songs about a specific theme or story]

2

:

created to show an idea

-

a concept car [=a car built to test or show a new design]