When you hear the word Buddha, what comes to mind? Do you think of Buddhism? Meditation? Monks in red robes?

Many of us have encountered the word before, but what does Buddha mean?

As it turns out, the word Buddha is a pretty versatile one. We’re going to explore what this word means, who the Buddha was, and how someone can become a Buddha.

What’s The Definition Of Buddha?

If you’re looking to learn more about how to practice Buddhism, understanding the basics is a great place to start.

But first, what does ‘Buddha‘ mean? The word ‘Buddha’ is Sanskrit and means, ‘enlightened one.’

A Buddha is a person who sees the world as it is without bias or clouded perception. They have reached a state of enlightened understanding. With this understanding, they become free from human suffering and break the cycle of death and rebirth.

Because the word ‘Buddha‘ means ‘enlightened one‘, anyone can become Buddha under the right circumstances. Yes, even you!

Now, don’t get us wrong. Becoming a Buddha is far from easy and it requires a lot of dedication. But anyone can become an enlightened one, no matter your age, gender, or spiritual beliefs.

Greater self-awareness is always a great first step. As Deborah King, Author of Mindvalley’s Be A Modern Master Program says, “all spiritual progress is born out of self-awareness.”

Who Was The Buddha?

When you think about ‘Buddha,’ you might think of The Buddha, also known as Siddhārtha Gautama.

Born in Lumbini, Nepal between 563 – 480 BCE, Siddhārtha, or Gautama Buddha, was the founder of Buddhism. He was born a prince and lived a life of luxury for many years. He was married to a woman named Yasodhara and together they had a son.

It wasn’t until Siddhārtha was 29 years old that he decided to leave the palace in search of something more. He traveled the surrounding land and for the first time in his life, he was confronted with human suffering, sickness, and death.

How Siddhārtha Became The Buddha

Siddhārtha was heartbroken by the human suffering he encountered. He knew there must be a better way.

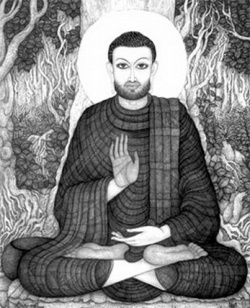

He left his royal responsibilities behind to study under the great aesthetics and sages of the age. For six years, he mastered meditation, yoga, and studied the mind. But Siddhārtha was not fully satisfied by the techniques of his gurus. He left them to meditate in isolation.

Underneath a Bodhi tree, he meditated for 49 days before he reached Enlightenment. It was at this time that Siddhārtha became the Buddha.

Siddhārtha established the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism and the Noble Eightfold Path that became the basics of Buddhism. He spent the rest of his life traveling in the Gangetic Plain, teaching all he met. He died at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, India.

What Does The Title “The Buddha” Mean?

Even though we often think of Siddhārtha when we hear this word, it’s important to know that he was not the only one who held this title.

Anyone who is able to see the world as it is, without obstacles of judgment and bias, can be a Buddha. That is the idea a Buddha stands for. Their belief is that morality, meditation, and wisdom will lead them to the path of enlightenment.

What Are The 3 Main Beliefs Of Buddhism?

The aim of The Buddha was to escape suffering and reach a level of enlightenment. Being a Buddha means breaking away from the cycle of rebirth and achieving nirvana — an eternal state of peace, happiness, and enlightenment — through meditation.

Here are three elements of The Noble Truths that you can incorporate every day into your life:

Dukkha: Life is painful and causes suffering. There are parts of life that inevitable, such as death, aging, sickness, suffering, and loss. But it doesn’t that it’s bad. Practice letting go of the belief that life is easy and pain-free, and the idea that you’re imperfect and broken — a misconception made common by industries like fashion, beauty, and big pharma’s. Instead, open your heart to whatever life has to offer.

Anitya: Life is in constant flux. The world is constantly evolving. No moment is the same. So, embrace the idea of change. Even though the idea of uncertainty may seem scary, it helps you appreciate everything and everyone around you.

Anatma: The self is always changing. You are also ever-evolving. So, focus on the person you want to be and the life you want to live, instead of ‘finding yourself.’

Is Having A Buddha Good Luck?

You’ve likely seen the Laughing Buddha before. According to Zen Buddhist traditions, having a statue of this little fellow is good luck.

The statue isn’t actually a depiction of Siddhārtha Gautama, but instead, a statue of a historical Buddhist monk called Budai, or Pu-Tai.

Budai belongs to the Japanese Buddhist pantheon and became famous for his happy-go-lucky personality and the cloth sack he carried as he wandered the land.

Over time, Budai became known as the Laughing Buddha. What does this Buddha mean? He became a symbol of abundance, prosperity, and good fortune.

5 Famous Buddha Quotes For Personal Awakening

While becoming a Buddha might not be at the top of your to-do list, you can choose to step a little closer to your personal bliss each and every day.

Here are five of the Buddha’s most famous quotes on ending suffering and achieving personal awakening:

“Irrigators channel waters; fletchers straighten arrows; carpenters bend wood; the wise master themselves.”

“Conquer anger with non-anger. Conquer meanness with generosity. And conquer dishonesty with truth.”

“There is no fear for one whose mind is not filled with desires.”

“Purity and impurity depend on oneself; no one can purify another.”

“When watching after yourself, you watch after others. When watching after others, you watch after yourself.”

Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Margret Eichmann

Score: 4.2/5

(35 votes)

The word Buddha means “enlightened.” The path to enlightenment is attained by utilizing morality, meditation and wisdom. Buddhists often meditate because they believe it helps awaken truth. There are many philosophies and interpretations within Buddhism, making it a tolerant and evolving religion.

What does the word Buddha mean literally?

A Buddha is one who has attained Bodhi; and by Bodhi is meant wisdom, an ideal state of intellectual and ethical perfection which can be achieved by man through purely human means. … The term Buddha literally means enlightened one, a knower.

What is the origin of the word Buddha?

The word buddha literally means «awakened» or «that which has become aware». It is the past participle of the Sanskrit root budh, meaning «to awaken», «to know», or «to become aware». Buddha as a title may be translated as «The Awakened One». The teachings of the Buddha are called the Dharma (Pali: Dhamma).

What is the English word for Buddha?

The word Buddha means «enlightened one» in Sanskrit or Fully Awakened One in Pāli. It is also a title for Siddhartha Gautama. He was the man who started Buddhism. Sometimes people call him «the Buddha» or the «Shakyamuni Buddha». Other times, people call any person a Buddha if they have found enlightenment.

What does Buddha mean spiritually?

The word Buddha means enlightened. … Buddhism has many interpretations and philosophies, making it a tolerant, flexible, and evolving religion. For many Buddhists, it’s a way of life or spiritual tradition rather than a religion. Morality, wisdom, and meditation pave the way to enlightenment.

19 related questions found

What is a Buddha a symbol of?

One of the most popular symbols is the Dharmachakra, or eight-spoked wheel, which represents the Buddha and Buddhism. Stupas, architectural mountain-shaped monuments, symbolize Buddha’s enlightened mind, while footprints or the swastika symbolize his presence.

Is it bad luck to buy a Buddha necklace?

Buying a discounted Buddha is great, maybe even a sign that he’s already bringing you prosperity via the savings. However do not bargain over the purchase price to get the salesperson down. It is considered disrespectful, bad form, and bad luck.

How do you know if you are a Buddha?

Superhuman physical characteristics such as very large size, a lump on the top of the head sometimes said to indicate extraordinary wisdom, fingers all the same length, or special markings on the palms and on the soles of the feet.

What are the 3 main beliefs of Buddhism?

The Basic Teachings of Buddha which are core to Buddhism are: The Three Universal Truths; The Four Noble Truths; and • The Noble Eightfold Path.

What are the 4 Noble Truths in Buddhism?

The Four Noble Truths

They are the truth of suffering, the truth of the cause of suffering, the truth of the end of suffering, and the truth of the path that leads to the end of suffering.

Can a woman reach nirvana in Buddhism?

The focus of practice is primarily on attaining Arhatship, and the Pali Canon has examples of both male and female Arhats who attained nirvana. … The Mahayana sutras maintain that a woman can become enlightened, only not in female form.

What is Buddhism in simple terms?

: a religion of eastern and central Asia growing out of the teaching of Siddhārtha Gautama that suffering is inherent in life and that one can be liberated from it by cultivating wisdom, virtue, and concentration.

What do Buddhists believe?

Buddhism is one of the world’s largest religions and originated 2,500 years ago in India. Buddhists believe that the human life is one of suffering, and that meditation, spiritual and physical labor, and good behavior are the ways to achieve enlightenment, or nirvana.

Who is the female Buddha?

Tara, Tibetan Sgrol-ma, Buddhist saviour-goddess with numerous forms, widely popular in Nepal, Tibet, and Mongolia. She is the feminine counterpart of the bodhisattva (“buddha-to-be”) Avalokiteshvara.

What are the 7 Buddhas?

The Seven Buddhas of Antiquity

- Vipassī

- Sikhī

- Vessabhū

- Kakusandha.

- Koṇāgamana.

- Kasyapa.

- Gautama.

What is the main goal of life to a Buddhist?

The ultimate goal of the Buddhist path is release from the round of phenomenal existence with its inherent suffering. To achieve this goal is to attain nirvana, an enlightened state in which the fires of greed, hatred, and ignorance have been quenched.

What is forbidden in Buddhism?

Five ethical teachings govern how Buddhists live. One of the teachings prohibits taking the life of any person or animal. … Buddhists with this interpretation usually follow a lacto-vegetarian diet. This means they consume dairy products but exclude eggs, poultry, fish, and meat from their diet.

Does Buddhism believe in Jesus?

Some high level Buddhists have drawn analogies between Jesus and Buddhism, e.g. in 2001 the Dalai Lama stated that «Jesus Christ also lived previous lives», and added that «So, you see, he reached a high state, either as a Bodhisattva, or an enlightened person, through Buddhist practice or something like that.» Thich …

Can you not drink as a Buddhist?

Drinking this kind of beverage whether one knows it as alcohol or not can be considered as transgression of vows. Despite the great variety of Buddhist traditions in different countries, Buddhism has generally not allowed alcohol intake since earliest times.

What is the dot on Buddha’s forehead?

In Buddhist art and culture, the Urna (more correctly ūrṇā or ūrṇākośa (Pāli uṇṇa), and known as báiháo (白毫) in Chinese) is a spiral or circular dot placed on the forehead of Buddhist images as an auspicious mark.

What are the main characteristics of Buddhism?

The Four Noble Truths of Buddhism: 1) suffering as a characteristic of existence, 2) the cause of suffering is craving and attachment, 3) the ceasing of suffering, called Nirvana, and 4) the path to Nirvana, made up of eight steps, sometimes called the Eightfold Path.

What are the qualities of Buddha?

The merits are acts of sharing, ethical morality, patience, renunciation, wisdom, diligence, truthfulness, determination, loving-kindness and equanimity. He perfected these to the most difficult and advanced level. He shared not only material things in His past lives but also His limbs and life.

Is it bad luck to get rid of a Buddha statue?

If, however, you just want to throw your statue away just because you think it looks ugly or might bring you bad luck, it is not the best decision to send it to a temple with that thought in mind. … So, if you think the statue can help a place and the people there, donate it. Otherwise, keep it for yourself.

Does Buddha bring good luck?

Laughing Buddha, as we all know, brings good luck, contentment and abundance in one’s life. It depicts plenitude of whatever one wishes for – be it wealth, happiness or satisfaction. Usually depicted as a stout, laughing. Laughing Buddha, as we all know, brings good luck, contentment and abundance in one’s life.

Is having a Buddha tattoo bad luck?

Getting a Buddha tattoo may be bad if not done in a respectful or pure hearted manner. Some people who hold these beliefs as sacred see it as cultural appropriation or simply blasphemous.

From Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the definition of a Buddha. For the historical Buddha, see Gautama Buddha.

|

Buddhism

|

|---|

|

Basic terms |

|

|

People |

|

|

Schools |

|

|

Practices |

|

|

This box:

|

Big Lord Buddha Statue, Lantau Island, HK

A Buddha is the holiest type of being in Buddhism, a teacher of God’s and humans. The word Buddha means «enlightened one» in Sanskrit or Fully Awakened One in Pāli.

It is also a title for Siddhartha Gautama. He was the man who started Buddhism. Sometimes people call him «the Buddha» or the «Shakyamuni Buddha». Other times, people call any person a Buddha if they have found enlightenment. If a person has not found enlightenment yet, but is very close to reaching it, then he is called bodhisattva.

Summary[change | change source]

Buddhists believe that there are many Buddhas. The most recent one was Gautama Buddha. People who will become Buddhas someday are called «bodhisattvas.»

Buddhists believe that the Buddha was enlightened, which means that he knew all about how to live a peaceful life and how to avoid suffering. He is said to have never argued with other people, but only said what was true and useful, out of compassion for others.[1]

Some Buddhists pray to Buddhas, but Buddhas are not gods. Buddhas are teachers who help the people who will listen. A Buddha is a human being who has woken up and can see the true way the world works. This knowledge totally changes the person so that they can have a better life in the present and the future. A Buddha can also help a person achieve enlightenment.

There are ideas which are said to lead someone to enlightenment. They are called the Dharma (Sanskrit) or «Dhamma» (Pāli), meaning «the way» or «the truth.» Anyone can become a Buddha, but it is very difficult. He became Buddha under the peepal or «bodhi» tree at Bodhgaya in Bihar in what is now India.

Types of Buddhas[change | change source]

There is a special type of Buddha called a pratyekabuddha or «silent Buddhas». These Buddhas reached enlightenment on their own, but they did not teach others.

Another type of Buddha is a samyaksambuddha. This is the best kind of Buddha because he is able to teach all living beings.

Seven Buddhas of the past[change | change source]

Buddhists believe that there have been many Buddhas in the past. There will also be many Buddhas in the future. Traditionally, seven Buddhas are given names.

- Vipashyin Buddha

- Shikhin Buddha

- Vishvabhu Buddha

- Krakucchanda Buddha

- Kanakamuni Buddha

- Kashyapa Buddha

- Shakyamuni Buddha

Maitreya will be the next Buddha.

32 Signs of a Great Man[change | change source]

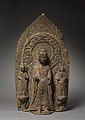

A Buddha is a person who has reached perfection. Some believe that there are 32 physical features of a Buddha; these are the 32 marks of a Great Man from Vedic Brahmin folklore, but are mentioned in the Pāli canon. Some of these features are represented in art and sculpture. These are listed below.

- Flat feet

- Thousand-spoked wheel symbol on feet

- Long, slender fingers

- Flexible hands and feet

- Webbed fingers and toes

- Full-sized heels

- Arched insteps

- Thighs like a royal stag

- Hands that reach below the knees

- Sheathed male organ

- Equal height and stretch of arms

- Dark-colored hair

- Graceful and curly body hair

- Golden-hued body

- Ten-foot halo around his body

- Soft, smooth skin

- Soles, palms, shoulders, and crown of head well-rounded

- Area below armpits filled out

- Lion-shaped body

- Erect and upright body

- Full, round shoulders

- Forty teeth

- White, even, and close teeth

- Four pure white canine teeth

- Jaw like a lion

- Saliva that improves the taste of all food

- Long and broad tongue

- Deep and resonant voice

- Deep blue eyes[2]

- Eyelashes like a royal bull

- White curl of hair (ūrṇā) that emits light between eyebrows

- Bump on the crown of the head

[change | change source]

- Siddhartha Gautama

- Bodhisattva

- Buddhism

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Ajahn Jagaro 1995, “What was the Buddha’s life really like?”[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Epstein, Ronald (2003), Buddhist Text Translation Society’s Buddhism A to Z (illustrated ed.), Burlingame, CA: Buddhist Text Translation Society, p. 200

3. “Chapter 3 Buddhism. Origins and Fundamental Tenets. .” Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations, section written by Cathy Cantwell & Hiroko Kawanami., Routledge, 2016, pp. 75–78

|

The Buddha |

|

|---|---|

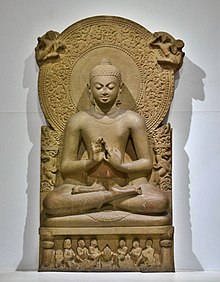

Statue of the Buddha, preaching his first sermon at Sarnath. Gupta period, ca. 475 CE. Archaeological Museum Sarnath (B(b) 181).[a] |

|

| Personal | |

| Born |

Siddhartha Gautama c. 563 BCE or 480 BCE Lumbini, Shakya Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[b] |

| Died | c. 483 BCE or 400 BCE (aged 80)[1][2][3][c]

Kushinagar, Malla Republic (according to Buddhist tradition)[d] |

| Resting place | Cremated; ashes divided among followers |

| Spouse | Yashodhara |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Known for | Founding Buddhism |

| Other names | Gautama Buddha Shakyamuni («Sage of the Shakyas») |

| Senior posting | |

| Predecessor | Kassapa Buddha |

| Successor | Maitreya |

| Sanskrit name | |

| Sanskrit | Siddhārtha Gautama |

| Pali name | |

| Pali | Siddhattha Gotama |

Siddhartha Gautama,[e] most commonly referred to as the Buddha,[f][g] was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE[4][5][6][c] and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lumbini, in what is now Nepal,[b] to royal parents of the Shakya clan, but renounced his home life to live as a wandering ascetic (Sanskrit: śramaṇa).[7][h] After leading a life of begging, asceticism, and meditation, he attained enlightenment at Bodh Gaya in what is now India. The Buddha thereafter wandered through the lower Indo-Gangetic Plain, teaching and building a monastic order. He taught a Middle Way between sensual indulgence and severe asceticism,[8] leading to Nirvana,[i] that is, freedom from ignorance, craving, rebirth, and suffering. His teachings are summarized in the Noble Eightfold Path, a training of the mind that includes ethical training and meditative practices such as sense restraint, kindness toward others, mindfulness, and jhana/dhyana (meditation proper). He died in Kushinagar, attaining parinirvana.[d] The Buddha has since been venerated by numerous religions and communities across Asia.

A couple of centuries after his death, he came to be known by the title Buddha, which means «Awakened One» or «Enlightened One.»[9] His teachings were compiled by the Buddhist community in the Vinaya, his codes for monastic practice, and the Sutta Piṭaka, a compilation of teachings based on his discourses. These were passed down in Middle Indo-Aryan dialects through an oral tradition.[10][11] Later generations composed additional texts, such as systematic treatises known as Abhidharma, biographies of the Buddha, collections of stories about his past lives known as Jataka tales, and additional discourses, i.e., the Mahayana sutras.[12][13]

Etymology, names and titles

Siddhārtha Gautama and Buddha Shakyamuni

According to Donald Lopez Jr., «… he tended to be known as either Buddha or Sakyamuni in China, Korea, Japan, and Tibet, and as either Gotama Buddha or Samana Gotama (“the ascetic Gotama”) in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.»[14]

Buddha, «Awakened One» or «Enlightened One,»[9][15][f] is the masculine form of budh (बुध् ), «to wake, be awake, observe, heed, attend, learn, become aware of, to know, be conscious again,»[16] «to awaken»[17][18] «»to open up» (as does a flower),»[18] «one who has awakened from the deep sleep of ignorance and opened his consciousness to encompass all objects of knowledge.»[18] It is not a personal name, but a title for those who have attained bodhi (awakening, enlightenment).[17] Buddhi, the power to «form and retain concepts, reason, discern, judge, comprehend, understand,»[16] is the faculty which discerns truth (satya) from falsehood.

His family name was Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali: Siddhattha Gotama). «Siddhārtha» (Sanskrit; P. Siddhattha; T. Don grub; C. Xidaduo; J. Shiddatta/Shittatta; K. Siltalta) means «He Who Achieves His Goal.»[19] The clan name of Gautama means «descendant of Gotama», «Gotama» meaning «one who has the most light,»[20] and comes from the fact that Kshatriya clans adopted the names of their house priests.[21][22]

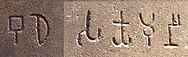

While the term «Buddha» is used in the Agamas and the Pali Canon, the oldest surviving written records of the term «Buddha» is from the middle of the 3rd century BCE, when several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 269–232 BCE) mention the Buddha and Buddhism.[23][24] Ashoka’s Lumbini pillar inscription commemorates the Emperor’s pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha’s birthplace, calling him the Buddha Shakyamuni[j] (Brahmi script: 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī, «Buddha, Sage of the Shakyas»).[25]

Shakyamuni (Sanskrit: [ɕaːkjɐmʊnɪ bʊddʱɐ]) means «Sage of the Shakyas.»[26]

Tathāgata

Tathāgata (Pali; Pali: [tɐˈtʰaːɡɐtɐ]) is a term the Buddha commonly used when referring to himself or other Buddhas in the Pāli Canon.[27] The exact meaning of the term is unknown, but it is often thought to mean either «one who has thus gone» (tathā-gata), «one who has thus come» (tathā-āgata), or sometimes «one who has thus not gone» (tathā-agata). This is interpreted as signifying that the Tathāgata is beyond all coming and going – beyond all transitory phenomena. [28] A tathāgata is «immeasurable», «inscrutable», «hard to fathom», and «not apprehended.»[29]

Other epithets

A list of other epithets is commonly seen together in canonical texts and depicts some of his perfected qualities:[30]

- Bhagavato (Bhagavan) – The Blessed one, one of the most used epithets, together with tathāgata[27]

- Sammasambuddho – Perfectly self-awakened

- Vijja-carana-sampano – Endowed with higher knowledge and ideal conduct.

- Sugata – Well-gone or Well-spoken.

- Lokavidu – Knower of the many worlds.

- Anuttaro Purisa-damma-sarathi – Unexcelled trainer of untrained people.

- Satthadeva-Manussanam – Teacher of gods and humans.

- Araham – Worthy of homage. An Arahant is «one with taints destroyed, who has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, laid down the burden, reached the true goal, destroyed the fetters of being, and is completely liberated through final knowledge.»

- Jina – Conqueror. Although the term is more commonly used to name an individual who has attained liberation in the religion Jainism, it is also an alternative title for the Buddha.[31]

The Pali Canon also contains numerous other titles and epithets for the Buddha, including: All-seeing, All-transcending sage, Bull among men, The Caravan leader, Dispeller of darkness, The Eye, Foremost of charioteers, Foremost of those who can cross, King of the Dharma (Dharmaraja), Kinsman of the Sun, Helper of the World (Lokanatha), Lion (Siha), Lord of the Dhamma, Of excellent wisdom (Varapañña), Radiant One, Torchbearer of mankind, Unsurpassed doctor and surgeon, Victor in battle, and Wielder of power.[32] Another epithet, used at inscriptions throughout South and Southeast Asia, is Maha sramana, «great sramana» (ascetic, renunciate).

Sources

Historical sources

Pali suttas

On the basis of philological evidence, Indologist and Pāli expert Oskar von Hinüber says that some of the Pāli suttas have retained very archaic place-names, syntax, and historical data from close to the Buddha’s lifetime, including the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta which contains a detailed account of the Buddha’s final days. Hinüber proposes a composition date of no later than 350–320 BCE for this text, which would allow for a «true historical memory» of the events approximately 60 years prior if the Short Chronology for the Buddha’s lifetime is accepted (but he also points out that such a text was originally intended more as hagiography than as an exact historical record of events).[33][34]

John S. Strong sees certain biographical fragments in the canonical texts preserved in Pāli, as well as Chinese, Tibetan and Sanskrit as the earliest material. These include texts such as the «Discourse on the Noble Quest» (Ariyapariyesanā-sutta) and its parallels in other languages.[35]

Pillar and rock inscriptions

No written records about Gautama were found from his lifetime or from the one or two centuries thereafter.[23][24][39] But from the middle of the 3rd century BCE, several Edicts of Ashoka (reigned c. 268 to 232 BCE) mention the Buddha and Buddhism.[23][24] Particularly, Ashoka’s Lumbini pillar inscription commemorates the Emperor’s pilgrimage to Lumbini as the Buddha’s birthplace, calling him the Buddha Shakyamuni (Brahmi script: 𑀩𑀼𑀥 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻 Bu-dha Sa-kya-mu-nī, «Buddha, Sage of the Shakyas»).[k][36][37] Another one of his edicts (Minor Rock Edict No. 3) mentions the titles of several Dhamma texts (in Buddhism, «dhamma» is another word for «dharma»),[40] establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Maurya era. These texts may be the precursor of the Pāli Canon.[41][42][l]

«Sakamuni» is also mentioned in a relief of Bharhut, dated to c. 100 BCE, in relation with his illumination and the Bodhi tree, with the inscription Bhagavato Sakamunino Bodho («The illumination of the Blessed Sakamuni»).[43][44]

Oldest surviving manuscripts

The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, found in Gandhara (corresponding to modern northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan) and written in Gāndhārī, they date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[45]

Biographical sources

Early canonical sources include the Ariyapariyesana Sutta (MN 26), the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta (DN 16), the Mahāsaccaka-sutta (MN 36), the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123), which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātaka tales retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[46] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama’s birth, such as the bodhisattva’s descent from the Tuṣita Heaven into his mother’s womb.

The sources which present a complete picture of the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are a variety of different, and sometimes conflicting, traditional biographies from a later date. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[47] Of these, the Buddhacarita[48][49][50] is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa in the first century CE.[51] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[52]

The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[52] The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[53] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE. The Nidānakathā is from the Theravada tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century by Buddhaghoṣa.[54]

Historical person

Understanding the historical person

Scholars are hesitant to make claims about the historical facts of the Buddha’s life. Most of them accept that the Buddha lived, taught, and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada, and during the reign of Bimbisara, the ruler of the Magadha empire; and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatashatru, who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain tirthankara.[55][56]

There is less consensus on the veracity of many details contained in traditional biographies,[57][58] as «Buddhist scholars […] have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person.»[59] The earliest versions of Buddhist biographical texts that we have already contain many supernatural, mythical or legendary elements. In the 19th century some scholars simply omitted these from their accounts of the life, so that «the image projected was of a Buddha who was a rational, socratic teacher—a great person perhaps, but a more or less ordinary human being». More recent scholars tend to see such demythologisers as remythologisers, «creating a Buddha that appealed to them, by eliding one that did not».[60]

Dating

The dates of Gautama’s birth and death are uncertain. Within the Eastern Buddhist tradition of China, Vietnam, Korea and Japan, the traditional date for the death of the Buddha was 949 BCE.[1] According to the Ka-tan system of time calculation in the Kalachakra tradition, Buddha is believed to have died about 833 BCE.[61]

Buddhist texts present two chronologies which have been used to date the lifetime of the Buddha.[62] The «long chronology,» from Sri Lankese chronicles, states that the Buddha was born 298 years before the coronation of Asoka, and died 218 years before his coronation. According to these chronicles Asoka was crowned in 326 BCE, which gives the dates of 624 and 544 BCE for the Buddha, which are the accepted dates in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia.[62] However, most scholars who accept the long chronology date Asoka’s coronation to 268 or 267 BCE, based on Greek evidence, thus dating the Buddha at 566 and ca. 486.[62]

Indian sources, and their Chinese and Tibetan translations, contain a «short chronology,» which place the Buddha’s birth at 180 years before Asoka’s coronation, and his death 100 years before Asoka’s coronation. Following the Greek sources of Asoka’s coronation, this dates the Buddha at 448 and 368 BCE.[62]

Most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as c. 563 BCE to 483 BCE.[1][63] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE. While at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[64][65][66] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha’s death.[1][67][c][72] These alternative chronologies, however, have not been accepted by all historians.[73][74][m]

The dating of Bimbisara and Ajatashatru also depends on the long or short chronology. In the long chrononology, Bimbisara reigned c. 558 – c. 492 BCE, and died 492 BCE,[79][80] while Ajatashatru reigned c. 492 – c. 460 BCE.[81] In the short chronology Bimbisara reigned c. 400 BCE,[82][n] while Ajatashatru died between c. 380 BCE and 330 BCE.[82])

Historical context

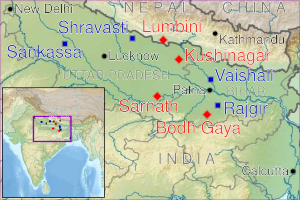

Ancient kingdoms and cities of India during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BCE)

Shakyas

According to the Buddhist tradition, Shakyamuni Buddha was a Sakya, a sub-Himalayan ethnicity and clan of north-eastern region of the Indian subcontinent.[b][o] The Shakya community was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the eastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[83] The community, though describable as a small republic, was probably an oligarchy, with his father as the elected chieftain or oligarch.[83] The Shakyas were widely considered to be non-Vedic (and, hence impure) in Brahminic texts; their origins remain speculative and debated.[84] Bronkhorst terms this culture, which grew alongside Aryavarta without being affected by the flourish of Brahminism, as Greater Magadha.[85]

The Buddha’s tribe of origin, the Shakyas, seems to have had non-Vedic religious practices which persist in Buddhism, such as the veneration of trees and sacred groves, and the worship of tree spirits (yakkhas) and serpent beings (nagas). They also seem to have built burial mounds called stupas.[84] Tree veneration remains important in Buddhism today, particularly in the practice of venerating Bodhi trees. Likewise, yakkas and nagas have remained important figures in Buddhist religious practices and mythology.[84]

Shramanas

The Buddha’s lifetime coincided with the flourishing of influential śramaṇa schools of thought like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jainism, and Ajñana.[86] The Brahmajala Sutta records sixty-two such schools of thought. In this context, a śramaṇa refers to one who labours, toils or exerts themselves (for some higher or religious purpose). It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira,[87] Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, with whose viewpoints the Buddha must have been acquainted.[88][89][p]

Śāriputra and Moggallāna, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the sceptic.[91] The Pāli canon frequently depicts Buddha engaging in debate with the adherents of rival schools of thought. There is philological evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Rāmaputta, were historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[92] Thus, Buddha was just one of the many śramaṇa philosophers of that time.[93] In an era where holiness of person was judged by their level of asceticism,[94] Buddha was a reformist within the śramaṇa movement, rather than a reactionary against Vedic Brahminism.[95]

Coningham and Young note that both Jains and Buddhists used stupas, while tree shines can be found in both Buddhism and Hinduism.[96]

Urban environment and egalitarianism

The rise of Buddhism coincided with the Second Urbanisation, in which the Ganges Basin was settled and cities grew, in which egalitarianism prevailed. According to Thapar, the Buddha’s teachings were «also a response to the historical changes of the time, among which were the emergence of the state and the growth of urban centres.»[97] While the Buddhist mendicants renounced society, they lived close to the villages and cities, depending for alms-givings on lay supporters.[97]

According to Dyson, the Ganges basin was settled from the north-west and the south-east, as well as from within, «[coming] together in what is now Bihar (the location of Pataliputra ).»[98] The Ganges basin was densely forested, and the population grew when new areas were deforestated and cultivated.[98] The society of the middle Ganges basin lay on «the outer fringe of Aryan cultural influence,»[99] and differed significantly from the Aryan society of the western Ganges basin.[100][101] According to Stein and Burton, «[t]he gods of the brahmanical sacrificial cult were not rejected so much as ignored by Buddhists and their contemporaries.»[100] Jainism and Buddhism opposed the social stratification of Brahmanism, and their egalitarism prevailed in the cities of the middle Ganges basin.[99] This «allowed Jains and Buddhists to engage in trade more easily than Brahmans, who were forced to follow strict caste prohibitions.»[102]

Semi-legendary biography

Nature of traditional depictions

In the earliest Buddhist texts, the nikāyas and āgamas, the Buddha is not depicted as possessing omniscience (sabbaññu)[105] nor is he depicted as being an eternal transcendent (lokottara) being. According to Bhikkhu Analayo, ideas of the Buddha’s omniscience (along with an increasing tendency to deify him and his biography) are found only later, in the Mahayana sutras and later Pali commentaries or texts such as the Mahāvastu.[105] In the Sandaka Sutta, the Buddha’s disciple Ananda outlines an argument against the claims of teachers who say they are all knowing [106] while in the Tevijjavacchagotta Sutta the Buddha himself states that he has never made a claim to being omniscient, instead he claimed to have the «higher knowledges» (abhijñā).[107] The earliest biographical material from the Pali Nikayas focuses on the Buddha’s life as a śramaṇa, his search for enlightenment under various teachers such as Alara Kalama and his forty-five-year career as a teacher.[108]

Traditional biographies of Gautama often include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such «in conformity with the world»; omniscience, and the ability to «suppress karma».[109] As noted by Andrew Skilton, the Buddha was often described as being superhuman, including descriptions of him having the 32 major and 80 minor marks of a «great man», and the idea that the Buddha could live for as long as an aeon if he wished (see DN 16).[110]

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha’s time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[111] British author Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[112] Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general outline of «birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death» must be true.[113]

Previous lives

The legendary Jataka collections depict the Buddha-to-be in a previous life prostrating before the past Buddha Dipankara, making a resolve to be a Buddha, and receiving a prediction of future Buddhahood.

Legendary biographies like the Pali Buddhavaṃsa and the Sanskrit Jātakamālā depict the Buddha’s (referred to as «bodhisattva» before his awakening) career as spanning hundreds of lifetimes before his last birth as Gautama. Many stories of these previous lives are depicted in the Jatakas.[114] The format of a Jataka typically begins by telling a story in the present which is then explained by a story of someone’s previous life.[115]

Besides imbuing the pre-Buddhist past with a deep karmic history, the Jatakas also serve to explain the bodhisattva’s (the Buddha-to-be) path to Buddhahood.[116] In biographies like the Buddhavaṃsa, this path is described as long and arduous, taking «four incalculable ages» (asamkheyyas).[117]

In these legendary biographies, the bodhisattva goes through many different births (animal and human), is inspired by his meeting of past Buddhas, and then makes a series of resolves or vows (pranidhana) to become a Buddha himself. Then he begins to receive predictions by past Buddhas.[118] One of the most popular of these stories is his meeting with Dipankara Buddha, who gives the bodhisattva a prediction of future Buddhahood.[119]

Another theme found in the Pali Jataka Commentary (Jātakaṭṭhakathā) and the Sanskrit Jātakamālā is how the Buddha-to-be had to practice several «perfections» (pāramitā) to reach Buddhahood.[120] The Jatakas also sometimes depict negative actions done in previous lives by the bodhisattva, which explain difficulties he experienced in his final life as Gautama.[121]

Birth and early life

A map showing Lumbini and other major Buddhist sites in India. Lumbini (present-day Nepal), is the birthplace of the Buddha,[122][b] and is a holy place also for many non-Buddhists.[123]

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini,[122][124] now in modern-day Nepal,[q] and raised in Kapilavastu.[125][r] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[127] It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, in present-day India,[128] or Tilaurakot, in present-day Nepal.[129] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 24 kilometres (15 mi) apart.[129][b]

In the mid-3rd century BCE the Emperor Ashoka determined that Lumbini was Gautama’s birthplace and thus installed a pillar there with the inscription: «…this is where the Buddha, sage of the Śākyas (Śākyamuni), was born.»[130]

According to later biographies such as the Mahavastu and the Lalitavistara, his mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana’s wife, was a princess from Devdaha, the ancient capital of the Koliya Kingdom (what is now the Rupandehi District of Nepal). Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[131][132] and ten months later[133] Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilavastu for her father’s kingdom to give birth.

Her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree. The earliest Buddhist sources state that the Buddha was born to an aristocratic Kshatriya (Pali: khattiya) family called Gotama (Sanskrit: Gautama), who were part of the Shakyas, a tribe of rice-farmers living near the modern border of India and Nepal.[134][126][135][s] His father Śuddhodana was «an elected chief of the Shakya clan»,[6] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha’s lifetime. Gautama was his family name.

The early Buddhist texts contain very little information about the birth and youth of Gotama Buddha.[137][138] Later biographies developed a dramatic narrative about the life of the young Gotama as a prince and his existential troubles.[139] They depict his father Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch of the Suryavansha (Solar dynasty) of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka). This is unlikely, as many scholars think that Śuddhodana was merely a Shakya aristocrat (khattiya), and that the Shakya republic was not a hereditary monarchy.[140][141][142] The more egalitarian gaṇasaṅgha form of government, as a political alternative to Indian monarchies, may have influenced the development of the śramanic Jain and Buddhist sanghas,[t] where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[143]

The day of the Buddha’s birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[144] Buddha’s Birthday is called Buddha Purnima in Nepal, Bangladesh, and India as he is believed to have been born on a full moon day.

According to later biographical legends, during the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode, analyzed the child for the «32 marks of a great man» and then announced that he would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great religious leader.[145][146] Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day and invited eight Brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave similar predictions.[145] Kondañña, the youngest, and later to be the first arhat other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[147]

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[148] According to the early Buddhist Texts of several schools, and numerous post-canonical accounts, Gotama had a wife, Yasodhara, and a son, named Rāhula.[149] Besides this, the Buddha in the early texts reports that «‘I lived a spoilt, a very spoilt life, monks (in my parents’ home).»[150]

The legendary biographies like the Lalitavistara also tell stories of young Gotama’s great martial skill, which was put to the test in various contests against other Shakyan youths.[151]

Renunciation

The «Great Departure» of Siddhartha Gautama, surrounded by a halo, he is accompanied by numerous guards and devata who have come to pay homage; Gandhara, Kushan period.

While the earliest sources merely depict Gotama seeking a higher spiritual goal and becoming an ascetic or śramaṇa after being disillusioned with lay life, the later legendary biographies tell a more elaborate dramatic story about how he became a mendicant.[139][152]

The earliest accounts of the Buddha’s spiritual quest is found in texts such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta («The discourse on the noble quest,» MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204.[153] These texts report that what led to Gautama’s renunciation was the thought that his life was subject to old age, disease and death and that there might be something better (i.e. liberation, nirvana).[154] The early texts also depict the Buddha’s explanation for becoming a sramana as follows: «The household life, this place of impurity, is narrow – the samana life is the free open air. It is not easy for a householder to lead the perfected, utterly pure and perfect holy life.»[155] MN 26, MĀ 204, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya and the Mahāvastu all agree that his mother and father opposed his decision and «wept with tearful faces» when he decided to leave.[156][157]

Legendary biographies also tell the story of how Gautama left his palace to see the outside world for the first time and how he was shocked by his encounter with human suffering.[158][159] These depict Gautama’s father as shielding him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering, so that he would become a great king instead of a great religious leader.[160] In the Nidanakatha (5th century CE), Gautama is said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Chandaka explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic that inspired him.[161][162][163] This story of the «four sights» seems to be adapted from an earlier account in the Digha Nikaya (DN 14.2) which instead depicts the young life of a previous Buddha, Vipassi.[163]

The legendary biographies depict Gautama’s departure from his palace as follows. Shortly after seeing the four sights, Gautama woke up at night and saw his female servants lying in unattractive, corpse-like poses, which shocked him.[164] Therefore, he discovered what he would later understand more deeply during his enlightenment: dukkha («standing unstable,» «dissatisfaction»[165][166][167][168]) and the end of dukkha.[169] Moved by all the things he had experienced, he decided to leave the palace in the middle of the night against the will of his father, to live the life of a wandering ascetic.[161]

Accompanied by Chandaka and riding his horse Kanthaka, Gautama leaves the palace, leaving behind his son Rahula and Yaśodhara.[170] He travelled to the river Anomiya, and cut off his hair. Leaving his servant and horse behind, he journeyed into the woods and changed into monk’s robes there,[171] though in some other versions of the story, he received the robes from a Brahma deity at Anomiya.[172]

According to the legendary biographies, when the ascetic Gautama first went to Rajagaha (present-day Rajgir) to beg for alms in the streets, King Bimbisara of Magadha learned of his quest, and offered him a share of his kingdom. Gautama rejected the offer but promised to visit his kingdom first, upon attaining enlightenment.[173][174]

Ascetic life and awakening

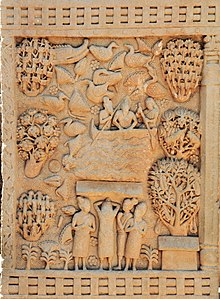

Miracle of the Buddha walking on the River Nairañjanā. The Buddha is not visible (aniconism), only represented by a path on the water, and his empty throne bottom right.[175] Sanchi.

Majjhima Nikaya 4 mentions that Gautama lived in «remote jungle thickets» during his years of spiritual striving and had to overcome the fear that he felt while living in the forests.[176] The Nikaya-texts narrate that the ascetic Gautama practised under two teachers of yogic meditation.[177][178] According to the Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204, after having mastered the teaching of Ārāḍa Kālāma (Pali: Alara Kalama), who taught a meditation attainment called «the sphere of nothingness», he was asked by Ārāḍa to become an equal leader of their spiritual community.[179][180]

Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice because it «does not lead to revulsion, to dispassion, to cessation, to calm, to knowledge, to awakening, to Nibbana», and moved on to become a student of Udraka Rāmaputra (Pali: Udaka Ramaputta).[181][182] With him, he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness (called «The Sphere of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception») and was again asked to join his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied for the same reasons as before, and moved on.[183]

According to some sutras, after leaving his meditation teachers, Gotama then practiced ascetic techniques.[184][u] The ascetic techniques described in the early texts include very minimal food intake, different forms of breath control, and forceful mind control. The texts report that he became so emaciated that his bones became visible through his skin.[186] The Mahāsaccaka-sutta and most of its parallels agree that after taking asceticism to its extremes, Gautama realized that this had not helped him attain nirvana, and that he needed to regain strength to pursue his goal.[187] One popular story tells of how he accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[188]

His break with asceticism is said to have led his five companions to abandon him, since they believed that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined. At this point, Gautama remembered a previous experience of dhyana he had as a child sitting under a tree while his father worked.[187] This memory leads him to understand that dhyana («meditation») is the path to liberation, and the texts then depict the Buddha achieving all four dhyanas, followed by the «three higher knowledges» (tevijja),[v] culminating in complete insight into the Four Noble Truths, thereby attaining liberation from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth.[190][191][192][193] [w]

According to the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56),[194] the Tathagata, the term Gautama uses most often to refer to himself, realized «the Middle Way»—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification, or the Noble Eightfold Path.[194] In later centuries, Gautama became known as the Buddha or «Awakened One». The title indicates that unlike most people who are «asleep», a Buddha is understood as having «woken up» to the true nature of reality and sees the world ‘as it is’ (yatha-bhutam).[9] A Buddha has achieved liberation (vimutti), also called Nirvana, which is seen as the extinguishing of the «fires» of desire, hatred, and ignorance, that keep the cycle of suffering and rebirth going.[195]

Following his decision to leave his meditation teachers, MĀ 204 and other parallel early texts report that Gautama sat down with the determination not to get up until full awakening (sammā-sambodhi) had been reached; the Ariyapariyesanā-sutta does not mention «full awakening», but only that he attained nirvana.[196] This event was said to have occurred under a pipal tree—known as «the Bodhi tree»—in Bodh Gaya, Bihar.[197]

As reported by various texts from the Pali Canon, the Buddha sat for seven days under the bodhi tree «feeling the bliss of deliverance».[198] The Pali texts also report that he continued to meditate and contemplated various aspects of the Dharma while living by the River Nairañjanā, such as Dependent Origination, the Five Spiritual Faculties and suffering (dukkha).[199]

The legendary biographies like the Mahavastu, Nidanakatha and the Lalitavistara depict an attempt by Mara, the ruler of the desire realm, to prevent the Buddha’s nirvana. He does so by sending his daughters to seduce the Buddha, by asserting his superiority and by assaulting him with armies of monsters.[200] However the Buddha is unfazed and calls on the earth (or in some versions of the legend, the earth goddess) as witness to his superiority by touching the ground before entering meditation.[201] Other miracles and magical events are also depicted.

First sermon and formation of the saṅgha

According to MN 26, immediately after his awakening, the Buddha hesitated on whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were overpowered by ignorance, greed, and hatred that it would be difficult for them to recognise the path, which is «subtle, deep and hard to grasp». However, the god Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some «with little dust in their eyes» will understand it. The Buddha relented and agreed to teach. According to Anālayo, the Chinese parallel to MN 26, MĀ 204, does not contain this story, but this event does appear in other parallel texts, such as in an Ekottarika-āgama discourse, in the Catusparisat-sūtra, and in the Lalitavistara.[196]

According to MN 26 and MĀ 204, after deciding to teach, the Buddha initially intended to visit his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, to teach them his insights, but they had already died, so he decided to visit his five former companions.[202] MN 26 and MĀ 204 both report that on his way to Vārānasī (Benares), he met another wanderer, called Ājīvika Upaka in MN 26. The Buddha proclaimed that he had achieved full awakening, but Upaka was not convinced and «took a different path».[203]

MN 26 and MĀ 204 continue with the Buddha reaching the Deer Park (Sarnath) (Mrigadāva, also called Rishipatana, «site where the ashes of the ascetics fell»)[204] near Vārānasī, where he met the group of five ascetics and was able to convince them that he had indeed reached full awakening.[205] According to MĀ 204 (but not MN 26), as well as the Theravāda Vinaya, an Ekottarika-āgama text, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, the Mahīśāsaka Vinaya, and the Mahāvastu, the Buddha then taught them the «first sermon», also known as the «Benares sermon»,[204] i.e. the teaching of «the noble eightfold path as the middle path aloof from the two extremes of sensual indulgence and self-mortification.»[205] The Pali text reports that after the first sermon, the ascetic Koṇḍañña (Kaundinya) became the first arahant (liberated being) and the first Buddhist bhikkhu or monastic.[206] The Buddha then continued to teach the other ascetics and they formed the first saṅgha, the company of Buddhist monks.[t]

Various sources such as the Mahāvastu, the Mahākhandhaka of the Theravāda Vinaya and the Catusparisat-sūtra also mention that the Buddha taught them his second discourse, about the characteristic of «not-self» (Anātmalakṣaṇa Sūtra), at this time[207] or five days later.[204] After hearing this second sermon the four remaining ascetics also reached the status of arahant.[204]

The Theravāda Vinaya and the Catusparisat-sūtra also speak of the conversion of Yasa, a local guild master, and his friends and family, who were some of the first laypersons to be converted and to enter the Buddhist community.[208][204] The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, who brought with them five hundred converts who had previously been «matted hair ascetics», and whose spiritual practice was related to fire sacrifices.[209][210] According to the Theravāda Vinaya, the Buddha then stopped at the Gayasisa hill near Gaya and delivered his third discourse, the Ādittapariyāya Sutta (The Discourse on Fire),[211] in which he taught that everything in the world is inflamed by passions and only those who follow the Eightfold path can be liberated.[204]

At the end of the rainy season, when the Buddha’s community had grown to around sixty awakened monks, he instructed them to wander on their own, teach and ordain people into the community, for the «welfare and benefit» of the world.[212][204]

Travels and growth of the saṅgha

Kosala and Magadha in the post-Vedic period

The chief disciples of the Buddha, Mogallana (chief in psychic power) and Sariputta (chief in wisdom)

For the remaining 40 or 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have travelled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, ascetics and householders, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.[213][152][214] According to Schumann, the Buddha’s travels ranged from «Kosambi on the Yamuna (25 km south-west of Allahabad )», to Campa (40 km east of Bhagalpur)» and from «Kapilavatthu (95 km north-west of Gorakhpur) to Uruvela (south of Gaya).» This covers an area of 600 by 300 km.[215] His sangha[t] enjoyed the patronage of the kings of Kosala and Magadha and he thus spent a lot of time in their respective capitals, Savatthi and Rajagaha.[215]

Although the Buddha’s language remains unknown, it is likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardisation.

The sangha wandered throughout the year, except during the four months of the Vassa rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely travelled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to flora and animal life.[216] The health of the ascetics might have been a concern as well.[217] At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. According to the Pali texts, shortly after the formation of the sangha, the Buddha travelled to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, and met with King Bimbisara, who gifted a bamboo grove park to the sangha.[218]

The Buddha’s sangha continued to grow during his initial travels in north India. The early texts tell the story of how the Buddha’s chief disciples, Sāriputta and Mahāmoggallāna, who were both students of the skeptic sramana Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta, were converted by Assaji.[219][220] They also tell of how the Buddha’s son, Rahula, joined his father as a bhikkhu when the Buddha visited his old home, Kapilavastu.[221] Over time, other Shakyans joined the order as bhikkhus, such as Buddha’s cousin Ananda, Anuruddha, Upali the barber, the Buddha’s half-brother Nanda and Devadatta.[222][223] Meanwhile, the Buddha’s father Suddhodana heard his son’s teaching, converted to Buddhism and became a stream-enterer.

The early texts also mention an important lay disciple, the merchant Anāthapiṇḍika, who became a strong lay supporter of the Buddha early on. He is said to have gifted Jeta’s grove (Jetavana) to the sangha at great expense (the Theravada Vinaya speaks of thousands of gold coins).[224][225]

Formation of the bhikkhunī order

Mahāprajāpatī, the first bhikkuni and Buddha’s stepmother, ordains

The formation of a parallel order of female monastics (bhikkhunī) was another important part of the growth of the Buddha’s community. As noted by Anālayo’s comparative study of this topic, there are various versions of this event depicted in the different early Buddhist texts.[x]

According to all the major versions surveyed by Anālayo, Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī, Buddha’s step-mother, is initially turned down by the Buddha after requesting ordination for her and some other women. Mahāprajāpatī and her followers then shave their hair, don robes and begin following the Buddha on his travels. The Buddha is eventually convinced by Ānanda to grant ordination to Mahāprajāpatī on her acceptance of eight conditions called gurudharmas which focus on the relationship between the new order of nuns and the monks.[227]

According to Anālayo, the only argument common to all the versions that Ananda uses to convince the Buddha is that women have the same ability to reach all stages of awakening.[228] Anālayo also notes that some modern scholars have questioned the authenticity of the eight gurudharmas in their present form due to various inconsistencies. He holds that the historicity of the current lists of eight is doubtful, but that they may have been based on earlier injunctions by the Buddha.[229][230]

Anālayo notes that various passages indicate that the reason for the Buddha’s hesitation to ordain women was the danger that the life of a wandering sramana posed for women that were not under the protection of their male family members, such as dangers of sexual assault and abduction. Due to this, the gurudharma injunctions may have been a way to place «the newly founded order of nuns in a relationship to its male counterparts that resembles as much as possible the protection a laywoman could expect from her male relatives.»[231]

Later years

Ajatashatru worships the Buddha, relief from the Bharhut Stupa at the Indian Museum, Kolkata

According to J.S. Strong, after the first 20 years of his teaching career, the Buddha seems to have slowly settled in Sravasti, the capital of the Kingdom of Kosala, spending most of his later years in this city.[225]

As the sangha[t] grew in size, the need for a standardized set of monastic rules arose and the Buddha seems to have developed a set of regulations for the sangha. These are preserved in various texts called «Pratimoksa» which were recited by the community every fortnight. The Pratimoksa includes general ethical precepts, as well as rules regarding the essentials of monastic life, such as bowls and robes.[232]

In his later years, the Buddha’s fame grew and he was invited to important royal events, such as the inauguration of the new council hall of the Shakyans (as seen in MN 53) and the inauguration of a new palace by Prince Bodhi (as depicted in MN 85).[233] The early texts also speak of how during the Buddha’s old age, the kingdom of Magadha was usurped by a new king, Ajatashatru, who overthrew his father Bimbisara. According to the Samaññaphala Sutta, the new king spoke with different ascetic teachers and eventually took refuge in the Buddha.[234] However, Jain sources also claim his allegiance, and it is likely he supported various religious groups, not just the Buddha’s sangha exclusively.[235]

As the Buddha continued to travel and teach, he also came into contact with members of other śrāmana sects. There is evidence from the early texts that the Buddha encountered some of these figures and critiqued their doctrines. The Samaññaphala Sutta identifies six such sects.[236]

The early texts also depict the elderly Buddha as suffering from back pain. Several texts depict him delegating teachings to his chief disciples since his body now needed more rest.[237] However, the Buddha continued teaching well into his old age.

One of the most troubling events during the Buddha’s old age was Devadatta’s schism. Early sources speak of how the Buddha’s cousin, Devadatta, attempted to take over leadership of the order and then left the sangha with several Buddhist monks and formed a rival sect. This sect is said to have been supported by King Ajatashatru.[238][239] The Pali texts depict Devadatta as plotting to kill the Buddha, but these plans all fail.[240] They depict the Buddha as sending his two chief disciples (Sariputta and Moggallana) to this schismatic community in order to convince the monks who left with Devadatta to return.[241]

All the major early Buddhist Vinaya texts depict Devadatta as a divisive figure who attempted to split the Buddhist community, but they disagree on what issues he disagreed with the Buddha on. The Sthavira texts generally focus on «five points» which are seen as excessive ascetic practices, while the Mahāsaṅghika Vinaya speaks of a more comprehensive disagreement, which has Devadatta alter the discourses as well as monastic discipline.[242]

At around the same time of Devadatta’s schism, there was also war between Ajatashatru’s Kingdom of Magadha, and Kosala, led by an elderly king Pasenadi.[243] Ajatashatru seems to have been victorious, a turn of events the Buddha is reported to have regretted.[244]

Last days and parinirvana

This East Javanese relief depicts the Buddha in his final days, and Ānanda, his chief attendant.

The main narrative of the Buddha’s last days, death and the events following his death is contained in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta (DN 16) and its various parallels in Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan.[245] According to Anālayo, these include the Chinese Dirgha Agama 2, «Sanskrit fragments of the Mahaparinirvanasutra», and «three discourses preserved as individual translations in Chinese».[246]

The Mahaparinibbana sutta depicts the Buddha’s last year as a time of war. It begins with Ajatashatru’s decision to make war on the Vajjika League, leading him to send a minister to ask the Buddha for advice.[247] The Buddha responds by saying that the Vajjikas can be expected to prosper as long as they do seven things, and he then applies these seven principles to the Buddhist Sangha[t], showing that he is concerned about its future welfare.

The Buddha says that the Sangha will prosper as long as they «hold regular and frequent assemblies, meet in harmony, do not change the rules of training, honour their superiors who were ordained before them, do not fall prey to worldly desires, remain devoted to forest hermitages, and preserve their personal mindfulness.» He then gives further lists of important virtues to be upheld by the Sangha.[248]

The early texts depict how the Buddha’s two chief disciples, Sariputta and Moggallana, died just before the Buddha’s death.[249] The Mahaparinibbana depicts the Buddha as experiencing illness during the last months of his life but initially recovering. It depicts him as stating that he cannot promote anyone to be his successor. When Ānanda requested this, the Mahaparinibbana records his response as follows:[250]

Ananda, why does the Order of monks expect this of me? I have taught the Dhamma, making no distinction of «inner» and » outer»: the Tathagata has no «teacher’s fist» (in which certain truths are held back). If there is anyone who thinks: «I shall take charge of the Order», or «the Order is under my leadership», such a person would have to make arrangements about the Order. The Tathagata does not think in such terms. Why should the Tathagata make arrangements for the Order? I am now old, worn out … I have reached the term of life, I am turning eighty years of age. Just as an old cart is made to go by being held together with straps, so the Tathagata’s body is kept going by being bandaged up … Therefore, Ananda, you should live as islands unto yourselves, being your own refuge, seeking no other refuge; with the Dhamma as an island, with the Dhamma as your refuge, seeking no other refuge… Those monks who in my time or afterwards live thus, seeking an island and a refuge in themselves and in the Dhamma and nowhere else, these zealous ones are truly my monks and will overcome the darkness (of rebirth).

After travelling and teaching some more, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his death and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[251] Bhikkhu Mettanando and Oskar von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[252][253]

The precise contents of the Buddha’s final meal are not clear, due to variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of certain significant terms. The Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.[254] Modern scholars also disagree on this topic, arguing both for pig’s flesh or some kind of plant or mushroom that pigs like to eat.[y] Whatever the case, none of the sources which mention the last meal attribute the Buddha’s sickness to the meal itself.[255]

As per the Mahaparinibbana sutta, after the meal with Cunda, the Buddha and his companions continued travelling until he was too weak to continue and had to stop at Kushinagar, where Ānanda had a resting place prepared in a grove of Sala trees.[256][257] After announcing to the sangha at large that he would soon be passing away to final Nirvana, the Buddha ordained one last novice into the order personally. His name was Subhadda.[256] He then repeated his final instructions to the sangha, which was that the Dhamma and Vinaya was to be their teacher after his death. Then he asked if anyone had any doubts about the teaching, but nobody did.[258] The Buddha’s final words are reported to have been: «All saṅkhāras decay. Strive for the goal with diligence (appamāda)» (Pali: ‘vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādethā’).[259][260]

He then entered his final meditation and died, reaching what is known as parinirvana (final nirvana, the end of rebirth and suffering achieved after the death of the body). The Mahaparinibbana reports that in his final meditation he entered the four dhyanas consecutively, then the four immaterial attainments and finally the meditative dwelling known as nirodha-samāpatti, before returning to the fourth dhyana right at the moment of death.[261][257]

Piprahwa vase with relics of the Buddha. The inscription reads: …salilanidhane Budhasa Bhagavate… (Brahmi script: …𑀲𑀮𑀺𑀮𑀦𑀺𑀥𑀸𑀦𑁂 𑀩𑀼𑀥𑀲 𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀢𑁂…) «Relics of the Buddha Lord».

Posthumous events

According to the Mahaparinibbana sutta, the Mallians of Kushinagar spent the days following the Buddha’s death honouring his body with flowers, music and scents.[262] The sangha[t] waited until the eminent elder Mahākassapa arrived to pay his respects before cremating the body.[263]

The Buddha’s body was then cremated and the remains, including his bones, were kept as relics and they were distributed among various north Indian kingdoms like Magadha, Shakya and Koliya.[264] These relics were placed in monuments or mounds called stupas, a common funerary practice at the time. Centuries later they would be exhumed and enshrined by Ashoka into many new stupas around the Mauryan realm.[265][266] Many supernatural legends surround the history of alleged relics as they accompanied the spread of Buddhism and gave legitimacy to rulers.

According to various Buddhist sources, the First Buddhist Council was held shortly after the Buddha’s death to collect, recite and memorize the teachings. Mahākassapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the council. However, the historicity of the traditional accounts of the first council is disputed by modern scholars.[267]

Teachings and views

Core teachings

A number of teachings and practices are deemed essential to Buddhism, including: the samyojana (fetters, chains or bounds), that is, the sankharas («formations»), the kleshas (uwholesome mental states), including the three poisons, and the āsavas («influx, canker»), that perpetuate saṃsāra, the repeated cycle of becoming; the six sense bases and the five aggregates, which describe the process from sense contact to consciousness which lead to this bondage to saṃsāra; dependent origination, which describes this process, and it’s reversal, in detail; and the Middle Way, with the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path, which prescribes how this bondage can be reversed.

According to N. Ross Reat, the Theravada Pali texts and the Mahasamghika school’s Śālistamba Sūtra share

these basic teachings and practices.[268] Bhikkhu Analayo concludes that the Theravada Majjhima Nikaya and Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contain mostly the same major doctrines.[269] Likewise, Richard Salomon has written that the doctrines found in the Gandharan Manuscripts are «consistent with non-Mahayana Buddhism, which survives today in the Theravada school of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, but which in ancient times was represented by eighteen separate schools.»[270]

Samsara

All beings have deeply entrenched samyojana (fetters, chains or bounds), that is, the sankharas («formations»), kleshas (unwholesome mental states), including the three poisons, and āsavas («influx, canker»), that perpetuate saṃsāra, the repeated cycle of becoming and rebirth. According to the Pali suttas, the Buddha stated that «this saṃsāra is without discoverable beginning. A first point is not discerned of beings roaming and wandering on hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving.»[271] In the Dutiyalokadhammasutta sutta (AN 8:6) the Buddha explains how «eight worldly winds» «keep the world turning around […] Gain and loss, fame and disrepute, praise and blame, pleasure and pain.» He then explains how the difference between a noble (arya) person and an uninstructed worldling is that a noble person reflects on and understands the impermanence of these conditions.[272]

This cycle of becoming is characterized by dukkha,[273] commonly referred to as «suffering,» dukkha is more aptly rendered as «unsatisfactoriness» or «unease.» It is the unsatisfactoriness and unease that comes with a life dictated by automatic responses and habituated selfishness,[274][275] and the unsatifacories of expecting enduring happiness from things which are impermanent, unstable and thus unreliable.[276] The ultimate noble goal should be liberation from this cycle.[277]

Samsara is dictated by karma, which is an impersonal natural law, similar to how certain seeds produce certain plants and fruits.[278].Karma is not the only cause for one’s conditions, as the Buddha listed various physical and environmental causes alongside karma.[279] The Buddha’s teaching of karma differed to that of the Jains and Brahmins, in that on his view, karma is primarily mental intention (as opposed to mainly physical action or ritual acts).[274] The Buddha is reported to have said «By karma I mean intention.»[280] Richard Gombrich summarizes the Buddha’s view of karma as follows: «all thoughts, words, and deeds derive their moral value, positive or negative, from the intention behind them.»[281]

The six sense bases and the five aggregates

The āyatana (six sense bases) and the five skandhas (aggregates) describe how sensory contact leads to attachment and dukkha. The six sense bases are eye and sight, ear and sound, nose and odour, tongue and taste, body and touch, and mind and thoughts. Together they create the input from which we create our world or reality, «the all.» This process takes place through the five skandhas, «aggregates,» «groups,» «heaps,» five groups of physical and mental processes,[282][283] anmely form (or material image, impression) (rupa), sensations (or feelings, received from form) (vedana), perceptions (samjna), mental activity or formations (sankhara), consciousness (vijnana).[284][285][286] They form part of other Buddhist teachings and lists, such as dependent origination, and explain how sensory input ultimately leads to bondage to samsara by the mental defilements.

Dependent Origination

Schist Buddha statue with the famed Ye Dharma Hetu dhāraṇī around the head, which was used as a common summary of Dependent Origination. It states: «Of those experiences that arise from a cause, The Tathāgata has said: ‘this is their cause, And this is their cessation’: This is what the Great Śramaṇa teaches.»

In the early texts, the process of the arising of dukkha is explicated through the teaching of dependent origination,[274] which says that everything that exists or occurs is dependent on conditioning factors.[287] The most basic formulation of dependent origination is given in the early texts as: ‘It being thus, this comes about’ (Pali: evam sati idam hoti).[288] This can be taken to mean that certain phenomena only arise when there are other phenomena present, thus their arising is «dependent» on other phenomena.[288]

The philosopher Mark Siderits has outlined the basic idea of the Buddha’s teaching of Dependent Origination of dukkha as follows:

given the existence of a fully functioning assemblage of psycho-physical elements (the parts that make up a sentient being), ignorance concerning the three characteristics of sentient existence—suffering, impermanence and non-self—will lead, in the course of normal interactions with the environment, to appropriation (the identification of certain elements as ‘I’ and ‘mine’). This leads in turn to the formation of attachments, in the form of desire and aversion, and the strengthening of ignorance concerning the true nature of sentient existence. These ensure future rebirth, and thus future instances of old age, disease and death, in a potentially unending cycle.[274]