-

The object of semasiology.

Two approaches to the study of meaning. -

Types of meaning.

-

Meaning and motivation.

3.1.

The branch of lexicology which studies meaning is called

«semasiology«.

Sometimes the term «semantics»

is used as a synonym to semasiology, but it is ambiguous as it can

stand as well for (1)

the expressive aspect of language in general and (2)

the meaning of one particular word.

Meaning

is certainly the most important property of the word but what is

«meaning»?

Meaning

is one of the most controversial terms in lexicology. At present

there is no generally accepted definition of meaning. Prof.

Smirnitsky defines meaning as «a certain reflection in the mind

of objects, phenomena or relations that makes part of the linguistic

sign, its so-called inner facet, whereas the sound form functions as

its outer facet». Generally speaking, meaning can be described

as a component of the word through which a concept is communicated,

enabling the word to denote objects in the real world.

There are

two

approaches

to the study of meaning: the

referential approach

and the

functional approach.

The former tries to define meaning in terms of relations between the

word (sound form), concept (notion, thought) and referent (object

which the word denotes). They are closely connected and the

relationship between them is represented by «the semiotic

triangle» ( = the basic triangle) of Ogden and Richards (in the

book «The Meaning of Meaning» (1923) by O.K. Ogden and I.A.

Richards).

symbol

referent

(sound form)

This view denies a direct link

between words and things, arguing that the relationship can be made

only through the use of our minds. Meaning is related to a sound

form, concept and referent but not identical with them: meaning is a

linguistic phenomenon while neither concept nor referent is.

The

main criticism of this approach is the difficulty of identifying

«concepts»: they are mental phenomena and purely

subjective, existing

in the minds of individuals. The strongest point of this approach is

that it connects meaning and the process of nomination.

The functional approach to

meaning is less concerned with what meaning is than with how it

works. It is argued, to say that «words have meanings»

means only that they are used in a certain way in a sentence. There

is no meaning beyond that. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), in

particular, stressed the importance of this approach in his dictum:

«The meaning of the word is its use in the language». So

meaning is studied by making detailed analyses of the way words are

used in contexts, through their relations to other words in speech,

and not through their relations to concepts or referents.

Actually,

the functional approach is basically confined to the analysis of

sameness or difference of meaning. For example, we can say that in

«take

the bottle»

and «take

to the

bottle»

take

has different meaning as it is used differently, but it does not

explain what the meaning of the verb is. So the functional approach

should

be used not as the theoretical basis for the study of meaning, but

only as complementary to the referential approach.

3.2.

Word meaning is made up of different components, commonly known

as types

of meaning.

The two main types of meaning are grammatical

meaning and

lexical meaning.

Grammatical

meaning

belongs to sets of word-forms and is common to

all words of the given part of speech,

e.g.

girls,

boys, classes, children, mice

express the meaning of

«plurality».

Lexical

meaning

belongs to an individual word in all its forms. It

comprises several components. The two main ones are the

denotational

component and

the connotational component.

The

denotational (

=

denotative)

component,

also called «referential

meaning» or «cognitive meaning», expresses the

conceptual (notional)

content of a word; broadly, it is some information, or knowledge,

of the real-world object that the word denotes.

Basically, this is the component that makes communication possible.

e.g.

notorious

«widely-known»,

celebrated «known

widely».

The

connotational (connotative) component

expresses the attitude of

the speaker to what he is saying, to the object denoted by the word.

This component consists of emotive

connotation and

evaluative connotation.

1) Emotive

connotation

( = «affective meaning», or an emotive charge),

e.g.

In «a

single tree»

single states that there is only one tree,

but

«a

lonely tree»

besides giving the same information, also renders

(conveys) the feeling of sadness.

We

shouldn’t confuse emotive connotations and emotive denotative

meanings

in which some emotion is named, e.g. horror,

love, fear, etc.

2) Evaluative

connotation

labels

the referent as «good» or «bad»,

e.g.

notorious

has a negative evaluative connotation, while

celebrated

a positive one. Cf.: a

notorious criminal/liar/ coward,

etc.

and a

celebrated singer/ scholar/ artist, etc.

It

should be noted that emotive and evaluative connotations are not

individual, they are common to all speakers of the language. But

emotive implications are individual (or common to a group of

speakers),

subjective, depend on personal experience.

e.g.

The word «hospital»

may evoke all kinds of emotions in

different

people (an

architect, a doctor, an invalid, etc.)

Stylistic

connotation,

or stylistic reference, another component of word meaning, stands

somewhat apart from emotive and evaluative connotations. Indeed, it

does not characterize a referent, but rather states how a word should

be used by referring it to a certain functional style of the language

peculiar to a specific sphere of communication. It shows in what

social context, in what communicative situations the word can be

used.

Stylistically,

words can be roughly classified into literary,

or formal

(e.g.

commence, discharge, parent),

neutral

(e.g.

father, begin, dismiss)

and non-literary,

or informal

(e.g.

dad, sack, set off).

3.3.

The term «motivation»

is used to denote the relationship between the

form of the word, i.e. its sound form, morphemic composition and

structural pattern, and its meaning.

There

are three

main types of motivation:

phonetic,

morphological

and

semantic.

1)

Phonetic

motivation

is a direct connection between the sound form

of a word and its meaning. There are two types of phonetic

motivation: sound

imitation and

sound symbolism.

a) Sound

imitation, or

onomatopoeia:

phonetically motivated words are

a direct imitation of the sounds they denote (or the sounds produced

by actions or objects they denote),

e.g.

buzz,

swish, bang, thud, cuckoo.

b) Sound

symbolism.

It’s argued by some linguists that the sounds that make up a word may

reflect or symbolise the properties of the object which the word

refers

to, i.e. they may suggest size, shape, speed, colour, etc.

e.g.

back

vowels

suggest big size, heavy weight, dark colour, front

vowels

suggest lightness, smallness, etc.

Many

words beginning with sl-

are slippery in some way: slide,

slip, slither, sludge,

etc.

or pejorative: slut,

slattern, sly, sloppy, slovenly;

words that end in -ump

almost

all refer to some kind of roundish mass: plump,

chump,

rump, hump, stump.

Certainly, not every word with

these phonetic characteristics will have the meaning suggested. This

is, perhaps, one of the reasons why sound symbolism is not

universally recognized in linguistics.

2) Morphological

motivation

is

a direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component

morphemes, the pattern of their arrangement and the meaning of the

word.

Morphologically motivated

words are those whose meaning is determined by the meaning of their

components,

e.g.

re-write

«write

again»,

ex-wife «former

wife».

The degree

of morphological motivation may be different. Words may be

fully

motivated

(then they are transparent), partially

motivated

and

non-motivated

(idiomatic, or opaque).

a)

If the meaning of the word is determined by the meaning of the

components

and the structural pattern, it is fully

motivated:

e.g. hatless.

b)

If the connection between the morphemic composition of a word and

its meaning is arbitrary, the word is non-motivated,

e.g. buttercup

«yellow-flowered plant».

c)

In hammer

-er

shows that it is an instrument, but what is «hamming«?

«Ham»

has no lexical meaning in this word, thus the word is partially

motivated.

Cf. also cranberry.

Motivation may be lost in the

course of time,

e.g.

in OE wīfman

was

motivated morphologically: wīf

+ man «wife

of a man»; now it is opaque;

its motivation is said to be faded (woman).

3) Semantic

motivation

is based on co-existence of direct and figurative

meanings of the same word,

e.g.

butterfly

–

1) insect; 2) showy and

frivolous person.( = metaphorical extension of the direct meaning).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

SEMASIOLOGY Types of Meaning What is meaning?

Word-meaning is the relationship between language and the real world, between the signaling system and the things that the signals refer to or stand for. There are two approaches to the problem of meaning: referential approach and functional approach.

Referential approach studies the connection of meaning with concept and things they denote. Functional approach studies the function of words in speech, how they work.

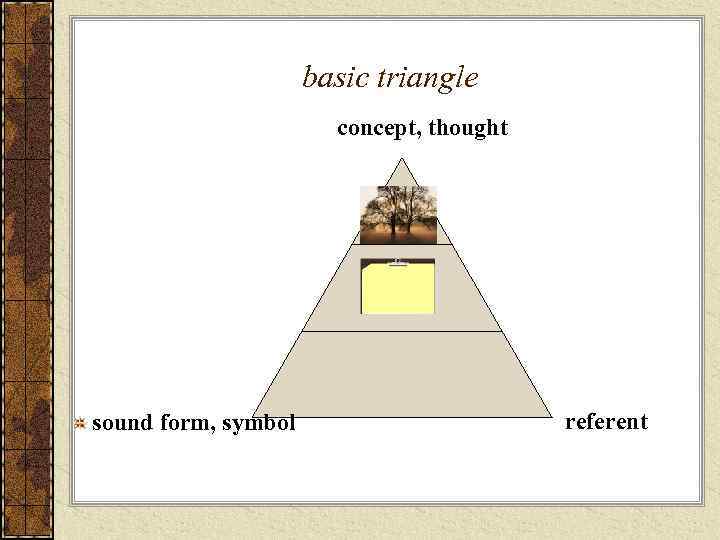

basic triangle concept, thought sound form, symbol referent

Types of meaning The word-meaning is made up of various components which are described as types of meaning. The two main types of meaning are grammatical and lexical. The grammatical meaning is the meaning proper to sets of word forms common to all the words of a certain class. (look, looks, looked; destroy, destroys, destroyed)

Lexical meaning The lexical meaning of the word is the component of the word through which a concept is communicated with real objects, things, qualities, actions, abstract notions. Lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions. (a student, students, student’s, students’)

Denotational component Lexical meaning includes denotational and connotational components. To denote means to serve as a name for an actually existing object referred to by a word. The term denotatum or referent means either a notion or an actually existing individual thing to which reference is made.

Connotational meaning expresses the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word: emotion, (mummy, granny), evaluation (clique), intensity (adore, love), stylistic coloring (to pass away, in one’s birthday suit) Stylistically words are subdivided into literary, stylistic, neutral, colloquial. friend –chum, fellow – guy, magnificent; terms, scientific words; poetic words

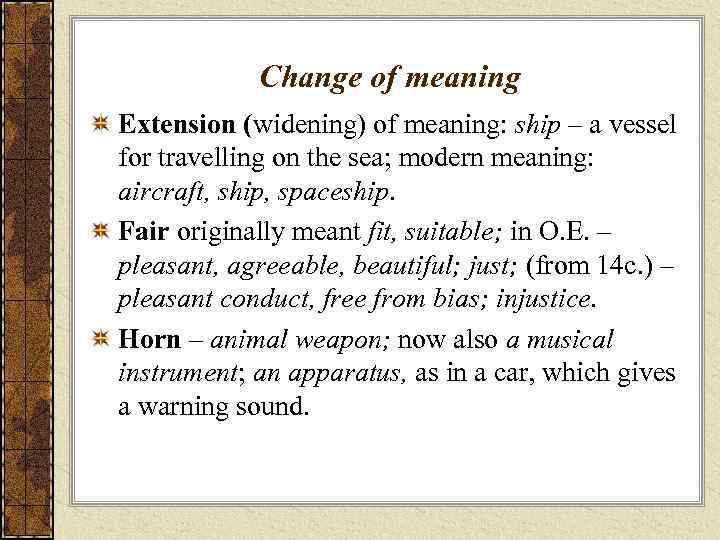

Change of meaning Extension (widening) of meaning: ship – a vessel for travelling on the sea; modern meaning: aircraft, ship, spaceship. Fair originally meant fit, suitable; in O. E. – pleasant, agreeable, beautiful; just; (from 14 c. ) – pleasant conduct, free from bias; injustice. Horn – animal weapon; now also a musical instrument; an apparatus, as in a car, which gives a warning sound.

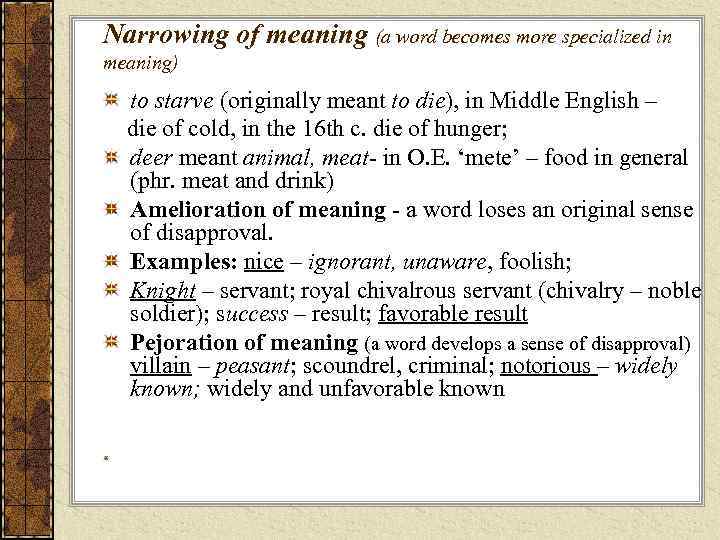

Narrowing of meaning (a word becomes more specialized in meaning) to starve (originally meant to die), in Middle English – die of cold, in the 16 th c. die of hunger; deer meant animal, meat- in O. E. ‘mete’ – food in general (phr. meat and drink) Amelioration of meaning — a word loses an original sense of disapproval. Examples: nice – ignorant, unaware, foolish; Knight – servant; royal chivalrous servant (chivalry – noble soldier); success – result; favorable result Pejoration of meaning (a word develops a sense of disapproval) villain – peasant; scoundrel, criminal; notorious – widely known; widely and unfavorable known

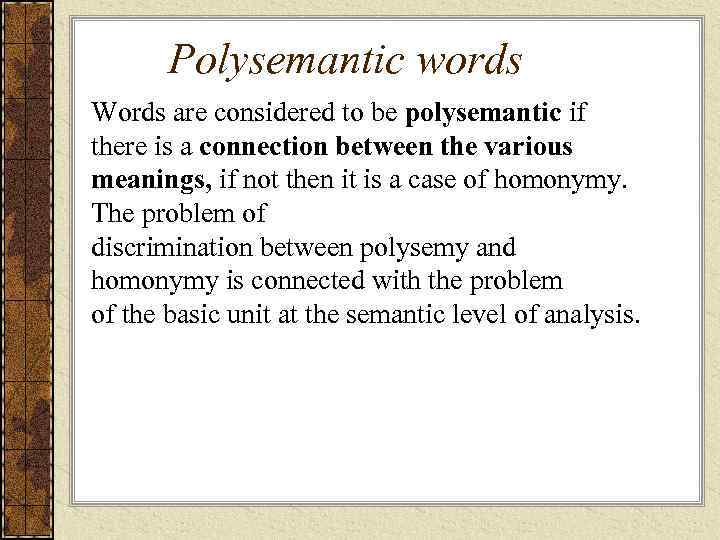

Polysemantic words Words are considered to be polysemantic if there is a connection between the various meanings, if not then it is a case of homonymy. The problem of discrimination between polysemy and homonymy is connected with the problem of the basic unit at the semantic level of analysis.

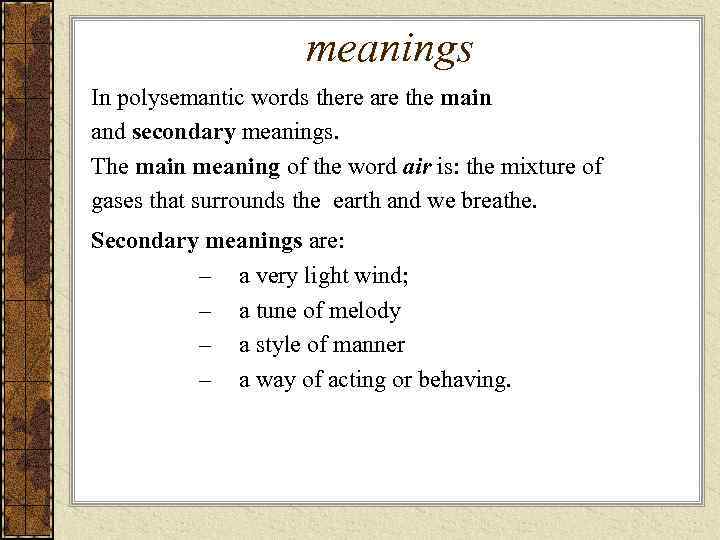

meanings In polysemantic words there are the main and secondary meanings. The main meaning of the word air is: the mixture of gases that surrounds the earth and we breathe. Secondary meanings are: – a very light wind; – a tune of melody – a style of manner – a way of acting or behaving.

The word is polysemantic in language but in speech it is monosemantic due to the context. When analyzing the semantic structure of a polysemantic word it is necessary to distinguish between two levels of analyses. The basic meaning of the word occurs in various contexts, while minor meanings are observed only in certain contexts.

Figurative language Metaphor foot of a hill or the mouth of a river The transfer of the name of one object to another, and different one, based on the associations of similarity or contiguity is called a metaphor.

Metaphors may be based on similarity of shape: head of a cabbage; function, position at the foot of the bed; behaviour and function: bookworm. The most frequent metaphors are based: on the words denoting parts of the body: arms and mouth of a river, eye of a needle; upon analogy between duration of time and space: long speech, a short time. another group of metaphors deals with transitions of proper names into common ones: a Don Juan, Hooligan

Metonymy When the transfer is based upon the association of contiguity it is called metonymy The chair may mean the chairman; cello, violin, saxophone are often used to denote the musicians who play them. We know many physical and technical units that are named after great scientists: volt, ampere, ohm watt. In political vocabulary the place of some establishment is used for its staff, for its policy: The White House, the Pentagon.

Geographical names: bikini, boston, china, tweed, cheviot. The factors accounting for semantic change are divided into linguistic and extra- linguistic factors. And we know two ways for providing new names for newly created notions: word-building and borrowing. New meanings can also be developed due to linguistic factors. The development of new meanings, a complete change of meaning, may be caused through the influence of other words, synonyms.

Euphemisms There are words in every language which people consciously avoid to use because they are considered indelicate, offensive, harsh, impolite or too direct. euphemisms. lavatory: washroom, restroom, ladies’ room gentlemen’s room, water closet drunk: intoxicated, merry, fresh, high, half-seasover stupid: not exactly brilliant; slow learner; white meat, dark meat (chicken’s breast, leg) the black death (mortal disease); Prince of Darkness (devil); to kick the bucket

In semantics and pragmatics, meaning is the message conveyed by words, sentences, and symbols in a context. Also called lexical meaning or semantic meaning.

In The Evolution of Language (2010), W. Tecumseh Fitch points out that semantics is «the branch of language study that consistently rubs shoulders with philosophy. This is because the study of meaning raises a host of deep problems that are the traditional stomping grounds for philosophers.»

Here are more examples of meaning from other writers on the subject:

Word Meanings

«Word meanings are like stretchy pullovers, whose outline contour is visible, but whose detailed shape varies with use: ‘The proper meaning of a word . . . is never something upon which the word sits like a gull on a stone; it is something over which the word hovers like a gull over a ship’s stern,’ noted one literary critic [Robin George Collingwood].»

(Jean Aitchison, The Language Web: The Power and Problem of Words. Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Meaning in Sentences

«It may justly be urged that, properly speaking, what alone has meaning is a sentence. Of course, we can speak quite properly of, for example, ‘looking up the meaning of a word’ in a dictionary. Nevertheless, it appears that the sense in which a word or phrase ‘has a meaning’ is derivative from the sense in which a sentence ‘has a meaning’: to say a word or phrase ‘has a meaning’ is to say that there are sentences in which it occurs which ‘have meanings’; and to know the meaning which the word or phrase has, is to know the meanings of sentences in which it occurs. All the dictionary can do when we ‘look up the meaning of a word’ is to suggest aids to the understanding of sentences in which it occurs. Hence it appears correct to say that what ‘has meaning’ in the primary sense is the sentence.» (John L. Austin, «The Meaning of a Word.» Philosophical Papers, 3rd ed., edited by J. O. Urmson and G. J. Warnock. Oxford University Press, 1990)

Different Kinds of Meaning for Different Kinds of Words

«There can’t be a single answer to the question ‘Are meanings in the world or in the head?’ because the division of labor between sense and reference is very different for different kinds of words. With a word like this or that, the sense by itself is useless in picking out the referent; it all depends on what is in the environs at the time and place that a person utters it. . . . Linguists call them deictic terms . . .. Other examples are here, there, you, me, now, and then. «At the other extreme are words that refer to whatever we say they mean when we stipulate their meanings in a system of rules. At least in theory, you don’t have to go out into the world with your eyes peeled to know what a touchdown is, or a member of parliament, or a dollar, or an American citizen, or GO in Monopoly, because their meaning is laid down exactly by the rules and regulations of a game or system. These are sometimes called nominal kinds—kinds of things that are picked out only by how we decide to name them.» (Steven Pinker, The Stuff of Thought. Viking, 2007)

Two Types of Meaning: Semantic and Pragmatic

«It has been generally assumed that we have to understand two types of meaning to understand what the speaker means by uttering a sentence. . . . A sentence expresses a more or less complete propositional content, which is semantic meaning, and extra pragmatic meaning comes from a particular context in which the sentence is uttered.» (Etsuko Oishi, «Semantic Meaning and Four Types of Speech Act.» Perspectives on Dialogue in the New Millennium, ed. P. Kühnlein et al. John Benjamins, 2003)

Pronunciation: ME-ning

Etymology

From the Old English, «to tell of»

Chapter 7 what is «meaning»?

Language is the amber in which

a thousand precious and subtle

thoughts have been safely

embedded and preserved

(From Word and Phrase by J. Fitzgerald)

The question posed by the title of this chapter is one of those questions which are easier to ask than answer The linguistic science at present is not able to put forward a definition of meaning which is conclusive.

However, there are certain facts of which we can be reasonably sure, and one of them is that the very function of the word as a unit of communication is made possible by its possessing a meaning. Therefore, among the word’s various characteristics, meaning is certainly the most important.

Generally speaking, meaning can be more or less described as a component of the word through which a concept is communicated, in this way endowing the word with the ability of denoting real objects, qualities actions and abstract notions. The complex and somewhat mysterious relationships between referent (object, etc. denoted by the word), concept and word are traditionally represented by the following triangle [35]:

By the «symbol» here is meant the word; thought or reference is concept. The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between word and referent: it is established only through the concept.

On the other hand, there is a hypothesis that concepts can only find their realization through words. It seems that thought is dormant till the word wakens it up. It is only when we hear a spoken word or read a printed word that the corresponding concept springs into mind.

The mechanism by which concepts (i. e. mental phenomena) are converted into words (i. e. linguistic phenomena) and the reverse process by which a heard or a printed word is converted into a kind of mental picture are not yet understood or described. Probably that is the reason why the process of communication through words, if one gives it some thought, seems nothing short of a miracle. Isn’t it fantastic that the mere vibrations of a speaker’s vocal chords should be taken up by a listener’s brain and converted into vivid pictures? If magic does exist in the world, then it is truly the magic of human speech; only we are so used to this miracle that we do not realize its almost supernatural qualities.

The branch of linguistics which specializes in the study of meaning is called semantics. As with many terms, the term «semantics» is ambiguous for it can stand, as well, for the expressive aspect of language in general and for the meaning of one particular word in all its varied aspects and nuances (i. e. the semantics of a word = the meaning(s) of a word).

As Marip Pei puts it in The Study of Language, «Semantics is ‘language’ in its broadest, most inclusive aspect. Sounds, words, grammatical forms, syntactical constructions are the tools of language. Semantics is language’s avowed purpose.» [39]

The meanings of all the utterances of a speech community are said by another leading linguist to include the total experience of that community; arts, science, practical occupations, amusements, personal and family life.

The modern approach to semantics is based on the assumption that the inner form of the word (i. e. its meaning) presents a structure which is called the semantic structure of the word.

Yet, before going deeper into this problem, it is necessary to make a brief survey of another semantic phenomenon which is closely connected with it.

Polysemy. Semantic Structure of the Word

The semantic structure of the word does not present an indissoluble unity (that is, actually, why it is referred to as «structure»), nor does it necessarily stand for one concept. It is generally known that most words convey several concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A word having several meanings is called polysemantic, and the ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the term polysemy.

Two somewhat naive but frequently asked questions may arise in connection with polysemy:

1. Is polysemy an anomaly or a general rule in English vocabulary?

2. Is polysemy an advantage or a disadvantage so far as the process of communication is concerned? Let us deal with both these questions together. Polysemy is certainly not an anomaly. Most English words are polysemantic. It should be noted that the wealth of expressive resources of a language largely depends on the degree to which polysemy has developed in the language. Sometimes people who are not very well informed in linguistic matters claim that a language is lacking in words if the need arises for the same word to be applied to several different phenomena. In actual fact, it is exactly the opposite: if each word is found to be capable of conveying, let us say, at least two concepts instead of one, the expressive potential of the whole vocabulary increases twofold. Hence, a well-developed polysemy is not a drawback but a great advantage in a language.

On the other hand, it should be pointed out that the number of sound combinations that human speech organs can produce is limited. Therefore at a certain stage of language development the production of new words by morphological means becomes limited, and polysemy becomes increasingly important in providing the means for enriching the vocabulary. From this, it should be clear that the process of enriching the vocabulary does not consist merely in adding new words to it, but, also, in the constant development of polysemy.

The system of meanings of any polysemantic word develops gradually, mostly over the centuries, as more and more new meanings are either added to old ones, or oust some of them (see Ch. 8). So the complicated processes of polysemy development involve both the appearance of new meanings and the loss of old ones. Yet, the general tendency with English vocabulary at the modern stage of its history is to increase the total number of its meanings and in this way to provide for a quantitative and qualitative growth of the language’s expressive resources.

When analysing the semantic structure of a polysemantic word, it is necessary to distinguish between two levels of analysis.

On the first level, the semantic structure of a word is treated as a system of meanings. For example, the semantic structure of the noun fire could be roughly presented by this scheme (only the most frequent meanings are given):

The above scheme suggests that meaning I holds a kind of dominance over the other meanings conveying the concept in the most general way whereas meanings П—V are associated with special circumstances, aspects and instances of the same phenomenon.

Meaning I (generally referred to as the main meaning) presents the centre of the semantic structure of the word holding it together. It is mainly through meaning I that meanings II—V (they are called secondary meanings) can be associated with one another, some of them exclusively through meaning I, as, for instance, meanings IV and V.

It would hardly be possible to establish any logical associations between some of the meanings of the noun bar except through the main meaning:1

Bar, n

II III

I

|

Any kind of barrier to prevent people from passing.

|

Meanings II and III have no logical links with one another whereas each separately is easily associated with meaning I: meaning II through the traditional barrier dividing a court-room into two parts; meaning III through the counter serving as a kind of barrier between the customers of a pub and the barman.

Yet, it is not in every polysemantic word that such a centre can be found. Some semantic structures are arranged on a different principle. In the following list of meanings of the adjective dull one can hardly hope to find a generalized meaning covering and holding together the rest of the semantic structure.

Dull, adj.

I. Uninteresting, monotonous, boring; e. g. a dull book, a dull film.

II. Slow in understanding, stupid; e. g. a dull student.

III. Not clear or bright; e. g. dull weather, a dull day, a dull colour.

IV. Not loud or distinct; e. g. a dull sound.

V. Not sharp; e. g. a dull knife.

VI. Not active; e. g. Trade is dull.

VII. Seeing badly; e. g. dull eyes (arch.). VIII. Hearing badly; e. g. dull ears (arch.).

Yet, one distinctly feels that there is something that all these seemingly miscellaneous meanings have in common, and that is the implication of deficiency, be it of colour (m. Ill), wits (m. II), interest (m. I), sharpness (m. V), etc. The implication of insufficient quality, of something lacking, can be clearly distinguished in each separate meaning.

In fact, each meaning definition in the given scheme can be subjected to a transformational operation to prove the point.

Dull, adj.

I. Uninteresting ——> deficient in interest or excitement.

II. … Stupid ——> deficient in intellect.

III. Not bright ——> deficient in light or colour.

IV. Not loud ——> deficient in sound.

V. Not sharp ——> deficient in sharpness.

VI. Not active ——> deficient in activity.

VII. Seeing badly ——> deficient in eyesight.

VIII. Hearing badly ——> deficient in hearing.

The transformed scheme of the semantic structure of dull clearly shows that the centre holding together the complex semantic structure of this word is not one of the meanings but a certain component that can be easily singled out within each separate meaning.

This brings us to the second level of analysis of the semantic structure of a word. The transformational operation with the meaning definitions of dull reveals something very significant: the semantic structure of the word is «divisible», as it were, not only at the level of different meanings but, also, at a deeper level.

Each separate meaning seems to be subject to structural analysis in which it may be represented as sets of semantic components. In terms of componential analysis, one of the modern methods of semantic research, the meaning of a word is defined as a set of elements of meaning which are not part of the vocabulary of the language itself, but rather theoretical elements, postulated in order to describe the semantic relations between the lexical elements of a given language.

The scheme of the semantic structure of dull shows that the semantic structure of a word is not a mere system of meanings, for each separate meaning is subject to further subdivision and possesses an inner structure of its own.

Therefore, the semantic structure of a word should be investigated at both these levels: a) of different meanings, b) of semantic components within each separate meaning. For a monosemantic word (i. e. a word with one meaning) the first level is naturally excluded.

Types of Semantic Components

The leading semantic component in the semantic structure of a word is usually termed denotative component (also, the term referential component may be used). The denotative component expresses the conceptual content of a word.

The following list presents denotative components of some English adjectives and verbs:

Denotative components

lonely, adj. ——> alone, without company ……………

notorious, adj. ——> widely known ……………

celebrated, adj. ——> widely known ……………

to glare, v. ——> to look ……………

to glance, v. ——> to look ……………

to shiver, v. ——> to tremble ……………

to shudder, v. ——> to tremble ……………

It is quite obvious that the definitions given in the right column only partially and incompletely describe the meanings of their corresponding words. To give a more or less full picture of the meaning of a word, it is necessary to include in the scheme of analysis additional semantic components which are termed connotations or connotative components.

Let us complete the semantic structures of the words given above introducing connotative components into the schemes of their semantic structures.

The above examples show how by singling out denotative and connotative components one can get a sufficiently clear picture of what the word really means. The schemes presenting the semantic structures of glare, shiver, shudder also show that a meaning can have two or more connotative components.

The given examples do not exhaust all the types of connotations but present only a few: emotive, evaluative connotations, and also connotations of duration and of cause. (For a more detailed classification of connotative components of a meaning, see Ch. 10.)

Meaning and Context

In the beginning of the paragraph entitled «Polysemy» we discussed the advantages and disadvantages of this linguistic phenomenon. One of the most important «drawbacks» of polysemantic words is that there is sometimes a chance of misunderstanding when a word is used in a certain meaning but accepted by a listener or reader in another. It is only natural that such cases provide stuff of which jokes are made, such as the ones that follow:

Customer. I would like a book, please.

Bookseller. Something light?

Customer. That doesn’t matter. I have my car with me.

In this conversation the customer is honestly misled by the polysemy of the adjective light taking it in the literal sense whereas the bookseller uses the word in its figurative meaning «not serious; entertaining».

In the following joke one of the speakers pretends to misunderstand his interlocutor basing his angry retort on the polysemy of the noun kick:

The critic started to leave in the middle of the second act of the play.

«Don’t go,» said the manager. «I promise there’s a terrific kick in the next act.»

«Fine,» was the retort, «give it to the author.»1

Generally speaking, it is common knowledge that context is a powerful preventative against any misunderstanding of meanings. For instance, the adjective dull, if used out of context, would mean different things to different people or nothing at all. It is only in combination with other words that it reveals its actual meaning: a dull pupil, a dull play, a dull razor-blade, dull weather, etc. Sometimes, however, such a minimum context fails to reveal the meaning of the word, and it may be correctly interpreted only through what Professor N. Amosova termed a second-degree context [1], as in the following example: The man was large, but his wife was even fatter. The word fatter here serves as a kind of indicator pointing that large describes a stout man and not a big one.

Current research in semantics is largely based on the assumption that one of the more promising methods of investigating the semantic structure of a word is by studying the word’s linear relationships with other words in typical contexts, i. e. its combinability or collocability.

Scholars have established that the semantics of words characterized by common occurrences (i. e. words which regularly appear in common contexts) are correlated and, therefore, one of the words within such a pair can be studied through the other.

Thus, if one intends to investigate the semantic structure of an adjective, one would best consider the adjective in its most typical syntactical patterns A + N (adjective + noun) and N + l + A (noun + link verb + adjective) and make a thorough study of the meanings of nouns with which the adjective is frequently used.

For instance, a study of typical contexts of the adjective bright in the first pattern will give us the following sets: a) bright colour (flower, dress, silk, etc.), b) bright metal (gold, jewels, armour, etc.), c) bright student (pupil, boy, fellow, etc.), d) bright face (smile, eyes, etc.) and some others. These sets will lead us to singling out the meanings of the adjective related to each set of combinations: a) intensive in colour, b) shining, c) capable, d) gay, etc.

For a transitive verb, on the other hand, the recommended pattern would be V + N (verb + direct object expressed by a noun). If, for instance, our object of investigation are the verbs to produce, to create, to compose, the correct procedure would be to consider the semantics of the nouns that are used in the pattern with each of these verbs: what is it that is produced? created? composed?

There is an interesting hypothesis that the semantics of words regularly used in common contexts (e. g. bright colours, to build a house, to create a work of art, etc.) are so intimately correlated that each of them casts, as it were, a kind of permanent reflection on the meaning of its neighbour. If the verb to compose is frequently used with the object music, isn’t it natural to expect that certain musical associations linger in the meaning of the verb to compose?

Note, also, how closely the negative evaluative connotation of the adjective notorious is linked with the negative connotation of the nouns with which it is regularly associated: a notorious criminal, thief, gangster, gambler, gossip, liar, miser, etc.

All this leads us to the conclusion that context is a good and reliable key to the meaning of the word. Yet, even the jokes given above show how misleading this key can prove in some cases. And here we are faced with two dangers. The first is that of sheer misunderstanding, when the speaker means one thing and the listener takes the word in its other meaning.

The second danger has nothing to do with the process of communication but with research work in the field of semantics. A common error with the inexperienced research worker is to see a different meaning in every new set of combinations. Here is a puzzling question to illustrate what we mean. Cf.: an angry man, an angry letter. Is the adjective angry used in the same meaning in both these contexts or in two different meanings? Some people will say «two» and argue that, on the one hand, the combinability is different (man — name of person; letter — name of object) and, on the other hand, a letter cannot experience anger. True, it cannot; but it can very well convey the anger of the person who wrote it. As to the combinability, the main point is that a word can realize the same meaning in different sets of combinability. For instance, in the pairs merry children, merry laughter, merry faces, merry songs the adjective merry conveys the same concept of high spirits whether they are directly experienced by the children (in the first phrase) or indirectly expressed through the merry faces, the laughter and the songs of the other word groups.

The task of distinguishing between the different meanings of a word and the different variations of combinability (or, in a traditional terminology, different usages of the word) is actually a question of singling out the different denotations within the semantic structure of the word.

Cf.: 1) a sad woman,

2) a sad voice,

3) a sac? story,

4) a sad scoundrel (= an incorrigible scoundrel)

5) a sad night (= a dark, black night, arch. poet.)

How many meanings of sad can you identify in these contexts? Obviously the first three contexts have the common denotation of sorrow whereas in the fourth and fifth contexts the denotations are different. So, in these five contexts we can identify three meanings of sad.

All this leads us to the conclusion that context is not the ultimate criterion for meaning and it should be used in combination with other criteria. Nowadays, different methods of componential analysis are widely used in semantic research: definitional analysis, transformational analysis, distributional analysis. Yet, contextual analysis remains one of the main investigative methods for determining the semantic structure of a word.

Exercises

I. Consider your answers to the following.

1. What is understood by «semantics»? Explain the term «polysemy».

2. Define polysemy as a linguistic phenomenon. Illustrate your answer with your own examples.

3. What are the two levels of analysis in investigating the semantic structure of a word?

4. What types of semantic components can be distinguished within the meaning of a word?

5. What is one of the most promising methods for investigating the semantic structure of a word? What is understood by collocability (combinability)?

6. How can one distinguish between the different meanings of a word and the different variations of combinability?

II. Define the meanings of the words in the following sentences. Say how the meanings of the same word are associated one with another.

1.I walked into Hyde Park, fell flat upon the grass and almost immediately fell asleep. 2. a) ‘Hello’, I said, and thrust my hand through the bars, whereon the dog became silent and licked me prodigiously, b) At the end of the long bar, leaning against the counter was a slim pale individual wearing a red bow-tie. 3. a) I began to search the flat, looking in drawers and boxes to see if I could find a key. b) I tumbled with a sort of splash upon the keys of a ghostly piano, c) Now the orchestra is playing yellow cocktail music and the opera of voices pitches a key higher, d) Someone with a positive manner, perhaps a detective, used the expression ‘madman’ as he bent over Welson’s body that afternoon, and the authority of his voice set the key for the newspaper report next morning. 4. a) Her mouth opened crookedly half an inch, and she shot a few words at one like pebbles. b) Would you like me to come to the mouth of the river with you? 5. a) I sat down for a few minutes with my head in ray hands, until I heard the phone taken up inside and the butler’s voice calling a taxi. b) The minute hand of the electric clock jumped on to figure twelve, and, simultaneously, the steeple of St. Mary’s whose vicar always kept his clock by the wireless began its feeble imitation of Big Ben. 6. a) My head felt as if it were on a string and someone were trying to pull it off. b) G. Quartermain, board chairman and chief executive of Supernational Corporation was a bull of a man who possessed more power than many heads of the state and exercised it like a king.

III. Copy out the following pairs of words grouping together the ones which represent the same meaning of each word. Explain the different meanings and the different usages, giving reasons for your answer. Use dictionaries if necessary.

smart, adj.

smart clothes, a smart answer, a smart house, a smart garden, a smart repartee, a smart officer, a smart blow, a smart punishment

stubborn, adj.

a stubborn child, a stubborn look, a stubborn horse, stubborn resistance, a stubborn fighting, a stubborn cough, stubborn depression

sound, adj.

sound lungs, a sound scholar, a sound tennis-player, sound views, sound advice, sound criticism, a sound ship, a sound whipping

roof, n.

edible roots, the root of the tooth, the root of the matter, the root of all evil, square root, cube root

perform, v.

to perform one’s duty, to perform an operation, to perform a dance, to perform a play

kick, v.

to kick the ball, to kick the dog, to kick off one’s slippers, to kick smb. downstairs

IV. The verb «to take» is highly polysemantic in Modern English. On which meanings of the verb are the following jokes based? Give your own examples to illustrate the other meanings of the word.

1. «Where have you been for the last four years?» «At college taking medicine.» «And did you finally get well?»

2. «Doctor, what should a woman take when she is run down?»

«The license number, madame, the license number.»

3.Proctor (exceedingly angry): So you confess that this unfortunate Freshman was carried to this frog pond and drenched. Now what part did you take in this disgraceful affair?

Sophomore (meekly): The right leg, sir.

V. Explain the basis for the following jokes. Use the dictionary when in doubt.

1. Caller: I wonder if I can see your mother, little boy. Is she engaged9

Willie: Engaged! She’s married.

2. Booking Clerk (at a small village station):

You’ll have to change twice before you get to York.

Villager (unused to travelling): Goodness me! And I’ve only brought the clothes I’m wearing.

3. The weather forecaster hadn’t been right in three months, and his resignation caused little surprise. His alibi, however, pleased the city council.

«I can’t stand this town any longer,» read his note. «The climate doesn’t agree with me.»

4.Professor: You missed my class yesterday, didn’t you?

Unsubdued student: Not in the least, sir, not in the least.

5. «Papa, what kind of a robber is a page?» «A what?»

«It says here that two pages held up the bride’s train.»

VI. Choose any polysemantic word that is well-known to you and illustrate its meanings with examples of your own. Prove that the meanings are related one to another.

VII. Read the following jokes. Analyse the collocability of the italicized words and state its relationship with the meaning.

1. Ladу (at party): Where is that pretty maid who was passing our cocktails a while ago?

Hostess: Oh, you are looking for a drink?

Lady: No, I’m looking for my husband.

2. Peggy: I want to help you, Dad. I shall get the dress-maker to teach me to cut out gowns.

Dad: I don’t want you to go that far. Peg, but you might cut out cigarettes, and taxi bills.

3. There are cynics who claim that movies would be better if they shot less films and more actors.

4. Killy: Is your wound sore, Mr. Pup?

Mr. Pup: Wound? What wound?

Kitty: Why, sister said she cut you at the dinner last night.

VIII. Try your hand at being a lexicographer. Write simple definitions to illustrate as many meanings as possible for the following polysemantic words. After you have done it, check your results using a dictionary.

Face, heart, nose, smart, to lose.

IX. Try your hand at the following research work.

a. Illustrate the semantic structure of one of the following words with a diagram; use the dictionary if necessary.

Foot, п.; hand, п.; ring, п.; stream, n.; warm, adj.; green, adj.; sail, n.; key, n.; glass, п.; eye, n.

b. Identify the denotative and connotative elements of the meanings in the following pairs of words.

To conceal — to disguise, to choose — to select, to draw — to paint, money — cash, photograph — picture, odd — queer.

c. Read the entries for the English word «court» and the Russian «суд» in an English-Russian and Russian-English dictionary. Explain the differences in the semantic structure of both words.